Abstract

Nanomedicine has been widely studied for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). How to synthesize a nanoplatform possessing a high synergistic therapeutic efficacy remains a challenge in this emerging research field. In this study, a convenient all-in-one therapeutic nanoplatform (FTY720@AM/T7-TL) is designed for HCC. This advanced nanoplatform consists of multiple functional elements, including gold-manganese dioxide nanoparticles (AM), tetraphenylethylene (T), fingolimod (FTY720), hybrid-liposome (L), and T7 peptides (T7). The nanoplatform is negatively charged at physiological pH and can transit to a positively charged state once moving to acidic pH environments. The specially designed pH-responsive charge-reversal nanocarrier prolongs the half-life of nanodrugs in blood and improves cellular uptake efficiency. The platform achieves a sustained and controllable drug release through dual stimulus-response, with pH as the endogenous stimulus and near-infrared as the exogenous stimulus. Furthermore, the nanoplatform realizes in situ O2 generation by catalyzing tumor over-expressed H2O2, which alleviates tumor microenvironment hypoxia and improves photodynamic therapy. Both in vitro and in vivo studies show the prepared nanoplatform has good photothermal conversion, cellular uptake efficiency, fluorescence/magnetic resonance imaging capabilities, and synergistic anti-tumor effects. These results suggest that the prepared all-in-one nanoplatform has great potential for dual-modal imaging-guided synergistic therapy of HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Tumor microenvironments, Stimuli-responsive drug release, In situ oxygen supplement, Dual-modal imaging

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The global incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is continually increasing, and its mortality rate accounts for the top five cancer-related deaths in the world [1,2]. The poor prognosis of HCC could be attributed to delayed diagnosis, rapid disease progression, poor surgical resection, etc. Medical imaging examination is a key to attain an early HCC diagnosis, as well as a thorough treatment evaluation afterwards [[3], [4], [5]]. Generally single-modal imaging is hardly to meet the requirement of complex cancer detection due to current technical limitations [[6], [7], [8]]. Multi-modal imaging has received increasing attention in precision medical diagnosis, as the combination of different imaging techniques provides comprehensive information for diagnosis [[9], [10], [11]]. Nanomaterials, with high specific surface area and easily modified sites, have been used as nanocarriers to link different types of imaging contrast agents through adsorption, covalent or non-covalent interactions for multi-modal imaging. These multi-modal imaging nanoplatforms have been designed to observe the in vivo distribution and metabolism of therapeutic agents with higher temporal and spatial resolution, faster therapeutic response monitoring, and more precise therapeutic outcome predictions, when compared to single-modal contrast imaging agents [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16]].

In recent years, nanocarriers have been widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer [[17], [18], [19]]. How to synthesize a nanoplatform possessing a high synergistic therapeutic efficacy remains a challenge in this emerging research field. Studies have showed that the stimuli-responsive drug release function in a nanocarrier can increase the effective drug release in lesion and improve the therapeutic effects [[20], [21], [22]]. One of the most used internal stimuli, pH, has been applied to trigger drug release in tumor region to enhance antitumor effects. When these designed nanocarriers reached the acidic microenvironment (pH 5.0–6.5) of tumor cells, they could accelerate drug release from the nanocarriers [[23], [24], [25]]. The designed nanocarriers can also respond to external stimuli (e.g., temperature, light, and magnetic fields) to control the effective drug release at tumor sites, thereby avoiding in vivo toxicity caused by random drug release [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. In addition, through ligand/biomarker/peptide modification, nanocarriers can actively target lesions to improve antitumor therapeutic effects [[30], [31], [32]]. For example, HAIYPRH (T7) peptide of transferrin receptor has been found to enhance the anticancer effects of liposome-based drug delivery system in HCC therapy [[33], [34], [35]].

A common problem with using positively charged nanocarriers is that these nanoparticles (NPs) can be detected by the reticuloendothelial system and rapidly removed from the blood circulation [36]. To prolong the half-life of nanocarriers in blood and enhance their uptake, nanocarriers can be designed with pH-responsive charge-reversal properties. Such specially designed nanocarriers can be neutral or negatively charged during blood circulation, followed by a conversion to positively charged status once reaching the tumor site to release therapeutic agents [[37], [38], [39], [40]].

Tumor microenvironment (TME) hypoxia is another factor reducing the efficacy of anticancer therapy [41,42]. For example, tumor cells could be blocked in the G1 and G2 phases due to lack of oxygen and nutrients, rendering cycle-specific chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., trimetrexatum) ineffective [43]. TME hypoxic may also lead to the failure of photodynamic therapy (PDT) failure, due to the reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [[44], [45], [46], [47]]. Numerous studies on nanomaterial therapy have shown that TME hypoxia can be alleviated by increasing the oxygen content at the tumor site to enhance antitumor effects [[48], [49], [50], [51], [52]].

In the present study, a dual-modal imaging guided nanocarrier has been innovatively designed as an all-in-one nanoplatform, namely FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. The prepared nanoplatform could modulate TME through in situ oxygen production, release the therapeutic agents in the response to endogenous (pH) and exogenous (near-infrared, NIR) trigger, and achieve enhanced synergistic effects of chemotherapy/PDT/Photothermal therapy (PTT) through the guidance of fluorescence/magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in real time. As illustrated in Scheme 1, we designed a hybrid-liposome system (L) with charge-reversal, thermosensitive, pH-sensitive, and tumor-targeting properties, to improve tumor specificity and cellular uptake. The prepared gold-manganese dioxide (Au–MnO2) NPs were served as photosensitizer, photothermal agent, peroxidase-like catalyst, and T1 MRI agent. Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) with aggregation-induced emission imaging (AIE) properties were served as fluorescence imaging agent. Fingolimod (FTY720) was used as a chemotherapeutic agent [[53], [54], [55]]. These functional elements were encapsulated in the inner core of hybrid-liposome via a hydration film method. Then, T7 peptides (T7) were connected to the maleimide group on DSPE PEG maleimide (DSPE-PEG-Mal) via a coupling reaction, providing tumor targeting effects for the prepared all-in-one nanoplatform system.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of therapeutic mechanism of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs nanoplatform: dual stimuli-responsive drug release, fluorescence/MRI-modal imaging, in situ oxygen supplement, and enhanced synergistic PDT/PTT/chemotherapy.

Through the peroxidase-like activity of Au–MnO2 NPs, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could in situ catalyze H2O2 in tumor cells to generate oxygen, enhancing the effect of PDT therapy. The photothermal conversion of Au–MnO2 NPs induced by NIR could be directly used for PTT. The high temperature produced by PTT further promoted the generation of ROS and accelerated the release of FTY720. This series of chain reactions could effectively enhance the synergistic effects of PTT, PDT and chemotherapy, forming multi-hit on tumors. Furthermore, MnO2 nanosheets coating of Au–MnO2 NPs produced more Mn2+ ions in the TME. A dual fluorescence/MR imaging-model could be obtained using the released TPE and Mn2+. Prospectively, the prepared all-in-one nanoplatform (FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs) would provide a new strategy for diagnostic and therapeutic applications in HCC therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

All chemicals and reagents were of chemical grade and used without further purification. Chloroauric acid hydrated (HAuCl4), sodium citrate, poly (allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH, Mw 15,000, 98%), 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 98.5%) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%) were purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China). Fingolimod hydrochloride (FTY720, 98%), tetraphenylethylene (TPE, 98%), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC, 99%), cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS, 97%), DSPE PEG Maleimide (DSPE-PEG-Mal, MW 2000 Da), DSPE PEG Acid (DSPE-PEG-COOH, MW 2000 Da), ethylene imine polymer (PEI, MW 1800, 99%), 2,3-dimethylmaleic anhydride (DMA, 98%) were obtained from Aladdin Reagent Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco's modified eagle's medium (DMEM), trypsin-EDTA, and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco-BRL (Burlington, Canada). Cell counting Kit 8 (CCK8), calcein-acetylmethoxylate (calcein-AM), propidium iodide (PI), 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% Triton-X-100, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation and characterization of HCC targeting NPs

2.2.1. Preparation of Au NPs and Au–MnO2 NPs

Briefly, 1 mL of sodium citrate solution (1 wt%) was added to 49 mL distilled water. The mixture was heated to boiling under magnetic stirring, and 80 μL of HAuCl4 (200 mM) was slowly dropped into the solution. The reaction was carried out for 30 min and then cooled down to room temperature. Through the cycle of continuous centrifugation and removal of the supernatant, the obtained Au NP was washed 3 times with ethanol, 3 times with deionized water, and finally resuspended in water for later use. To prepare Au–MnO2 NPs, 10 mL of Au NPs (2 mg/mL) solution and 5 mL PAH (10 mg/mL) were mixed and stirred for 2 h. Then, 5 mL of KMnO4 (3 mg/mL) was added to the solution and stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The mixture was reacted for a few minutes until its color turned dark brown. The obtained Au–MnO2 NPs were washed three times with deionized water by centrifugation method, and the resultant was resuspended in water for later use.

2.2.2. Preparation of liposome-based NPs

DSPE-PEG-PEI-DMA (synthesis and characterizations were described in SI, section, 10 mg), DPPC (10 mg), CHEMS (10 mg), and DSPE-PEG-Mal (10 mg) were mixed. These lipids (40 mg) were then mixed with TPE (6 mg), FTY720 (4 mg), chloroform (8 mL), and methanol (2 mL). After the powder was completely dissolved, the residual solvents were removed under reduced pressure at 60 °C. The formed lipid film was hydrated with Au–MnO2 NPs dispersion (2 mg/mL) to prepare FTTY720@AM/TL NPs via sonication and extrusion at room temperature. The resulting product was dialyzed against distilled water (molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) 3500 Da) for 24 h to remove free drugs. The obtained NPs (FTTY720@AM/TL NPs) was freeze-dried and refrigerated for later use. To prepare tumor targeting NPs, FTY720@AM/TL NPs and T7 peptide were dispersed in PBS buffer and stirred at 4 °C for 4 h. The resulting product was transferred to a dialysis bag (MWCO = 3500Da) and treated with deionized water for 24 h. After freeze-drying, the resulting product (FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs) was collected and stored at 4 °C.

2.2.3. Characterization of HCC targeting NPs

The morphologies of the prepared NPs were observed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM2100F, JEOL, Japan). Element composition of the Au–MnO2 NPs was characterized by elemental mappings (JEM2100F, JEOL, Japan) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi, Thermo, US). The averaged particle size and zeta potential of the prepared NPs were measured using Zetasizer Nano Instrument (nano ZS, Malvern, UK). The absorption spectra of Au and Au–MnO2 NPs were carried out using a UV–Vis–NIR spectrophotometer (UV-3600, Shimadzu, Japan). The stabilities of FTTY720@AM/TL and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs in PBS (pH 7.4) and serum at room temperature were evaluated by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using Zetasizer Nano Instrument (nano ZS, Malvern, UK). The aggregation induced emission (AIE) properties of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were studied using a fluorescence spectroscopy (RF-6000, Shimadzu, Japan), and the photos of NPs with different concentration were taken under 365 nm ultraviolet light with a digital camera. The photoluminescence intensity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at 450 nm was measured in the presence of acetonitrile and water by using a photoluminescence spectrum imaging system (PMEye-3000, Zolix, China). A 3.0 T MR imaging scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, SIEMENS, Germany) was used to evaluate the in vitro T1-weighted MR imaging capabilities of different concentration of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 5.0, pH 6.5 and pH 7.4. The r1 value was determined by fitting Mn concentration in the sample and the relaxation time (1/T1, s−1). The drug encapsulation efficiency (DEE) and drug-loading content (DLC) were calculated according to Eq. (1) and Eq. (2), respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.3. In vitro photothermal properties

An infrared thermal imaging camera (UTi165 K, Uni-Trend Technology, China) was used to evaluate the photothermal properties of the prepared NPs, and the temperature changes were recorded during the irradiation process. The samples were subjected to a NIR treatment (1 W/cm2, 808 nm, FU8083000–3 CE4 F, Shenzhen Fuzhe Technology, China) for 10 min. PBS was used as a control group, while the Au–MnO2 NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs groups both contained 50 μg mL−1 of Au–MnO2 NPs. In addition, the photothermal stability of these samples was evaluated by observing the temperature changes at 10-min interval (10-min laser on and 10-min laser off) for 4 irradiation cycles (1 W/cm2, 10 min, 808 nm).

Different concentration of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (100, 250, 500, and 1000 μg/mL) were irradiated using a NIR laser with intensity of 1 W/cm2 at 808 nm for 10 min. An infrared thermal imaging camera (UTi165 K, Uni-Trend Technology, China) was used to record the temperature changes during the irradiation process. Photothermal performance of the FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (100 μg/mL) was investigated under different laser power densities (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 W/cm2).

2.4. Drug release behaviors of FTY720 from FTY20@AM/T-TL NPs

The in vitro release behaviors of FTY720 from FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs was investigated using a dialysis method at 37 °C. Briefly, 1 mL of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (1 mg/mL) were put into a dialysis bag (MWCO = 3500 Da) and placed in a centrifuge tube containing 10 mL PBS at 37 °C under different pH conditions (pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0). The tube was shaken at 120 rpm for 48 h. At specific time points, 1 mL of release media was taken out and same volume of fresh release media was replenished into the beaker. The amount of FTY720 released at each time point was analyzed by a UV spectrophotometer at 220 nm. More detailed NIR triggered drug release profiles were investigated in a similar manner over a 10-min interval (10-min laser on and 10-min laser off) for 60 min at different pH conditions.

2.5. Oxygen production

A portable dissolved oxygen meter (AR8406, SMART SENSOR, China) was used to monitor the in vitro oxygen production of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs under different pH conditions (pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0). FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (1 mg/mL) were dispersed in PBS buffer in the presence of H2O2 (100 μM). The oxygen produced was measured by the oxygen meter at designed time points.

2.6. Cell lines

Human hepatoma cells (HepG2) and human hepatic cells (L02) were purchased from Cell Resource Center, Shanghai Institute for Biological Sciences (SIBS, Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% of FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% of CO2.

2.7. In vitro cytotoxicity (CCK-8 assay)

The in vitro cytotoxicity of the prepared NPs at different concentrations (i.e., containing FTY720 at 0.5, 1, 5, 10 or 15 μM/mL) against either cancer cells or normal liver cells was evaluated by CCK-8 assay. Briefly, the cells were cultured in a 96-well plate (104 cells per well) at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then co-cultured with prepared NPs of different concentration. After co-incubation for 6 h, the NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). After 24 h co-incubation, CCK-8 assay solutions were applied to each well and incubated for another 2 h. The cell viability was calculated as follows:

| (3) |

where A blank is the absorbance at 570 nm without cells, A control is the absorbance value of cells treated with PBS, A treatment is the absorbance value of cells treated with prepared NPs.

2.8. Apoptosis assay

HepG2 cells were seeded in a 12-well plate (105 cells per well) and incubated at 37°Cfor 24 h. The cells were then co-cultured with PBS, FTY720, FTY720@AM/TL NPs or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. Each group (except PBS) contained 10 μM mL−1 FTY720. After co-incubation for 6 h, the NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). After incubation for 18 h, the cells were washed three time with PBS, stained with annexin V–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and propidium iodide (PI). The percentage of apoptotic cells was quantified by a flow cytometry (Attune NxT, ThermoFisher, USA).

2.9. Live/dead staining assay

HepG2 cells were seeded in 12-well plates (8000 cells per well) at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then co-cultured with PBS, FTY720, FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. Each group (except PBS) contained 10 μM mL−1 FTY720. After co-incubation for 6 h, the NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). After incubation for 18 h, the cells were washed with PBS and stained with Calcein-AM/PI dyes for 30 min. Then the cells were washed with PBS twice and observed via fluorescence microscope (BX43, OLYMPUS, Japan).

2.10. Colony assay

The colony formation assay was used to investigate the in vitro synergistic therapies efficiency of prepared NPs on HCC cells. HepG2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (200 cells per well) at 37 °C for 12 h. The cells were then co-cultured with PBS, FTY720, FTY720@AM/TL NPs or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. Each group (except PBS) contained 10 μM mL−1 FTY720. The cell groups were washed with PBS every two days and supplemented with medium containing PBS or the prepared NPs. The NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm) every two days. After 7 days of incubation, the cells were resuspended and washed with PBS, fixed with methanol, and stained with 0.2% crystal violet for 30 min. The cells were washed with PBS to remove excess staining agent and photographed.

2.11. In vitro cellular uptake assay

HepG2 cells were cultured in a confocal microscopic plate (1 × 105 cells per well) at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then co-cultured with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, respectively. Each group contained 10 μM/mL FTY720. After co-incubation for 6 h, the NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). After another 2 h of co-incubation, the cells were washed three time with PBS and stained with DAPI. The fluorescence signal in cells were measured by a confocal laser scanning imaging (CLSM) system (LSM880, ZEISS, Germany). The emission wavelength of TPE was 690 nm and the emission wavelength of DAPI was 450 nm.

2.12. Intracellular ROS generation assay

The ROS generation induced by the prepared NPs on HepG2 cells was measured by CLSM. HepG2 cells were seeded on confocal microscopic plates (1 × 105 cells per well) overnight. The cells were then co-cultured with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, respectively. Each group contained 10 μM/mL FTY720. After co-incubation for 6 h, the NIR-treatment groups (FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). The cells were washed three times with PBS, subsequently stained with 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, 10 μM), followed by incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min. The cell images were obtained using a CLSM system (LSM880, ZEISS, Germany).

2.13. Western blot analysis

HepG2 cells were treated in the same way as described in apoptosis assay. After 24 h, the treated cells were extracted by cell lysis buffer from Cell Signaling Technology (Shanghai, China) and collected by centrifugation (12,000 rpm for 10 min) at 4 °C. The protein concentrations were determined by BCA protein assay. The effects of prepared NPs (with or without NIR treatment) on the expression levels of related proteins were determined using Western blot as described previously [56].

2.14. Animal experiments

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of the Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital (No. KY-D-2021-418-01). Female BALB/c nude mice (6–8 weeks old, average weight 17–20 g) were bought from Guangdong Laboratory Animals Monitoring Institute (Guangdong, China). HepG2 cells (4 × 106 cells in 100 μL of PBS) were injected subcutaneously into the right thigh to obtain a HepG2 tumor bearing mouse model. When the tumor grew to approximately 120–150 mm3, the tumor bearing mice were prepared for in vivo biodistribution and synergistic antitumor therapeutic experiments.

2.14.1. In vivo dual-modal imaging, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetic studies

Tumor-bearing nude mice were intravenously injected with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at a dose of 2 mg/kg FTY720-equivalent, respectively. At the designed time points (i.e., 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h), the in vivo AIE FL image was obtained by IVIS spectrum imaging system (Perkin Elmer, USA). The mice were sacrificed 24 h after injection, and their primary organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) and tumors were collected for ex vivo fluorescence imaging and quantitative biodistribution analysis. Similarly, at the designated time points (i.e., 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h), the in vivo MR imaging test was carried out on a MR imaging scanner (3.0 T, MAGNETOM Skyra, SIEMENS, Germany). The mice were sacrificed 24 h after injection, and their primary organs (heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney) and tumors were collected for Mn content detection by ICP-AES (240FS, Agilent-Varian Co. Ltd, USA). The content of Mn was presented as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

For pharmacokinetic analysis, blood samples (about 20 μL) were extracted from HepG-2 tumor bearing mice after tail vein injection of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (2 mg/kg FTY720-equivalent) at different time points (15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h), respectively. The concentration of Au in blood was determined by ICP-AES and presented as the percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). The decay curve of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs in blood was fitted to a two-compartmental model to extract the half-time of the drug in blood.

2.14.2. In vivo synergistic anti-tumor efficacy and long-term biosafety

To evaluate the in vivo synergistic anti-tumor efficacy, HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into 6 groups (n = 5): PBS (a), FTY720 (b), FTY720@AM/TL NPs (c), FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (d), FTY720@AM/TL NPs + laser (e); and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + laser (f). Except for the control group (100 μL, PBS, every other day), mice in the other groups were injected intravenously at a dose of 2 mg kg−1 FTY720-equivalent every other day. At 6 h post-injection, the NIR-treatment groups, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). During the NIR irradiation process, the temperature change of tumor site was monitored and recorded by an infrared detector (UTi165 K, Uni-Trend Technology, China). The tumor volume and the body were measured in everyday; the tumor size was determined using the formula as follows:

| (4) |

where, W and L represented the tumor width and the tumor length, respectively.

After 14 days of treatment, the mice were sacrificed, and the major organs and tumors were collected for hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining. The obtained tumors were weighted and photographed. For the survival rate analysis, HepG-2 tumor bearing mice were treated under the same conditions up to a period of 45 days, and the number of surviving mice in each group was recorded.

For investigate the long-term in vivo toxicity of the prepared NPs, healthy Balb/c mice were intravenously injected with: PBS (a), FTY720 (b), FTY720@AM/TL NPs (c), FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (d), FTY720@AM/TL NPs + laser (e); and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + laser (f). Except for the control group (100 μL, PBS, every other day), mice in the other groups were injected intravenously at a dose of 2 mg/kg FTY720-equivalent every other day. At 6 h post-injection, the NIR-treatment groups, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). After 14-day treatment, whole blood of the mice was collected to assess liver function and renal function.

2.15. Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was carried out via one-way ANOVA with a Tukey post-hoc test by SPSS. Statistical significance was noted as follows: ∗p<0.05 and ∗∗p<0.01.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs

The prepared all-in-one nanoplatform (FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs) was successfully synthesized as illustrated in Scheme 1. DSPE-PEG-PEI-DMA as a pH-sensitive charge-reversal polymer, provided a protective layer that was negatively charged at pH 7.4 and positively charged at pH 6.5.1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) as a thermo-response liposome (with phase transition temperature of 41 °C) would undergo a phase transition under near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation [57], while cholesytryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS) was used as pH-response layer [58]. The synthesis route of DSPE-PEG-PEI-DMA was presented in Scheme S1 (supplementary information, SI), and the chemical structure of DSPE-PEG-PEI-DMA was confirmed by 1HNMR and FT-IR (Fig. S1, SI).

TEM image revealed that the prepared Au–MnO2 NPs exhibited a spherical structure with a narrow size dispersion (Fig. 1A). The average diameter of Au–MnO2 NPs was about 10–25 nm, which was consistent with the DLS results (Fig. 1C). The elemental mapping confirmed that the presence of manganese (Mn) and oxygen (O) elements around Au–MnO2 NPs (Fig. S3, SI). XPS analyses (Fig. 3, SI) showed that the sample had four characteristic peaks, which were Au 4f at 85 eV, C 1s at 285 eV, O 1s at 531 eV, and Mn 2p at 653.5 and 641.7 eV, respectively. These results indicated that the MnO2 nanosheet had been successfully coated onto the surface of Au NPs. The XRD pattern of Au–MnO2 NPs (Fig. S4, SI) showed that the peaks at 29.8, 37.9, and 56.4 were consistent with the (110), (101), and (211) crystalline planes of cubic MnO2 (JCPDS: 1–799), while the peaks at 38.2, 44.4, 64.7 and 77.7 were consistent with the (111), (200), (220) and (311) crystalline planes of cubic Au (JCPDS: 4–784). TEM image showed that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were irregularly spherical with yolk shell-like structure (Fig. 1B), and the particle size was distributed within the range of 50–100 nm (Fig. 1C). Numerous studies have shown that NPs with a size in the range of 10–200 nm are able to penetrate the tumor area and be taken up by tumor cells through enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects [[59], [60], [61]]. The stability tests showed that the prepared FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were well dispersed in PBS and serum without aggregation, and the changes in PDI were negligible (Fig. S12 and Table S2, SI).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of Au–MnO2 and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. (A) TEM images of Au–MnO2 NPs. (B) TEM images of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. (C) DLS of Au–MnO2 and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. (D) Zeta potential of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0. (E) Fluorescence images of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at various concentrations. (F) PL intensity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at various concentrations. (G) In vitro MR imaging of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs with different concentrations of Mn2+ at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0. (H) Linear fitting of Mn2+ concentration and 1/T1 of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0.

Fig. 3.

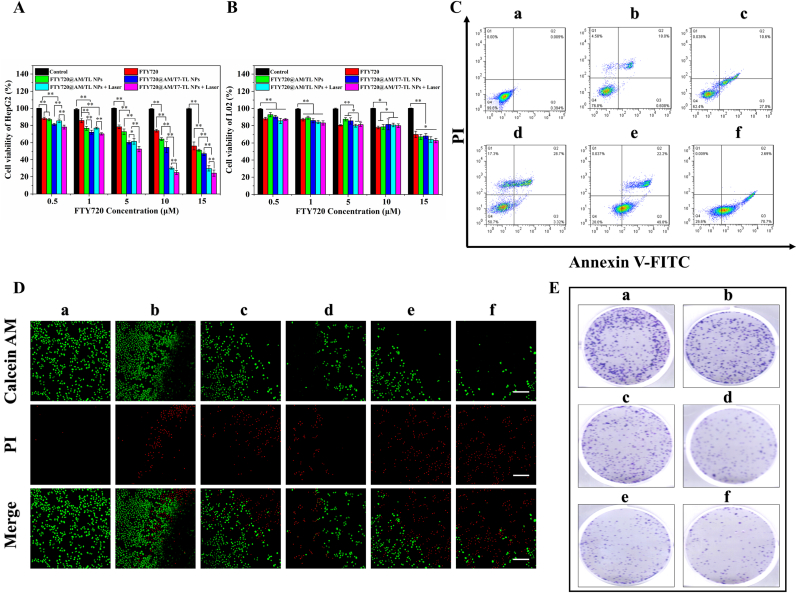

In vitro antitumor effect of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. (A) Cell viability of HepG2 cells incubated with different concentration of treatment groups (except for PBS, the other groups containing FTY720 at 0.5, 1, 5, 10 or 15 μM/mL). (B) Cell viability of L02 cells incubated with different concentration of treatment groups (except for PBS, the other groups containing FTY720 at 0.5, 1, 5, 10 or 15 μM/mL). (C) Flow cytometry analysis of FITC-Annexin V/PI double-stained HepG2 cells incubated with the treatment groups (except for PBS, the other groups containing 10 μM/mL FTY720). (D) Live/dead cell assay of HepG2 incubated with treatment groups (except for PBS, the other groups containing 10 μM/mL FTY720), scale bar 100 μm. (E) Colony formation assay of HepG2 incubated with treatment groups (except for PBS, the other groups containing 10 μM/mL FTY720). The treatment groups were (a) PBS, (b) FTY720, (c) FTY720@AM/TL NPs, (d) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser, and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser. The NIR-treatment groups, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm).

The zeta potentials of the prepared FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0 were −16.5 ± 1.1 mV, 8.1 ± 0.5 mV and 12.7 ± 1.2 mV, respectively (Fig. 1D). This result suggested that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs possessed pH-responsive charge-reversal properties, which were negatively charged in the blood circulation (pH 7.4) and positively charged in TME (pH 6.5 and 5.0). When the prepared NPs arrived at TME, DSPE-PEG-PEI-DMA on the surface of NPs could transit to positively charged state due to the cleavable amide bond between DSPE-PEG-PEI and DMA. The charge-reversal effect of nanocarrier in response to changes in pH environment, could effectively enhance the uptake by tumor cells and prolong its half-life in the blood circulation [[37], [38], [39], [40]].

3.1.1. In vitro dual-modal imaging

Aggregation induced fluorescence (AIE) dyes have the advantages such as low cost, high sensitivity, good operability, etc. In this manuscript, TPE was encapsulated in FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs as fluorescence imaging unit for in vitro and in vivo imaging. As shown in Fig. S13, the fluorescence (FL) intensity of NPs increased remarkably with the increase of water content in the solvent, indicating FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs possessed AIE properties. As shown in Fig. 1E, the fluorescence image of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed a concentration-dependent brightening effect. The results of photoluminescence (PL) intensity confirmed that the PL intensity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs increased with the increase of NPs concentration (Fig. 1F).

The T1-weighted MR imaging effects of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were evaluated at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0 by using an MRI scanner (Fig. 1G). As the concentration of Mn increased, the MRI signal gradually enhanced under the same pH conditions. As the pH changed from pH 7.0 to pH 5.0, the MRI signal of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs became stronger at the same sample concentration. In Fig. 1F, the linear relationship of transverse relaxation time T1 to the Mn concentration (mM) in the sample was fitted to calculate the transverse relaxation rate of the sample (r1). The result showed that in an environment of pH 5.0, the value of r1 (6.293 mM−1S−1) was the highest, which was approximately 2.3 times and 6.2 times that of pH 6.5 (2.721 mM−1S−1) and pH 7.4 (1.006 mM−1S−1), respectively. This might be due to the fact that the enclosed Mn in MnO2 was isolated from the surrounding aqueous environment, which could not provide efficient proton transverse relaxation. When MnO2 was decomposed in an acidic environment, a large amount of Mn2+ would be released and directly contact with the water proton environment, enhancing the MRI T1 signal.

3.2. In vitro photothermal effects

After 10 min of NIR irradiation, the temperature of Au–MnO2 and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs rapidly increased from room temperature to 51.1 °C and 48.6 °C, respectively, while that of PBS only increased to 29.4 °C (Fig. 2A and B). During four NIR-irradiation circles, both Au–MnO2 and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed repeatable heating and cooling pattern, indicating that the prepared NPs possessed good photothermal stabilities. The prepared nanocarriers also showed concentration-dependent and laser-power-dependent temperature-raising effects (Fig. S14). The photothermal conversion efficiency (η) of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at 808 nm was calculated as 45.3% (Fig. S15), which was higher than most of the previously reported PTT agents, e.g., Au nanorods (21%) [62], Cu2-x Se nanocrystals (22%) [63], Bi2S3 nanorods [64] (28.1%), etc.

Fig. 2.

Photothermal effect, in vitro dual-response drug release, and oxygen production capacity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. (A) Laser-triggered temperature elevation profiles for PBS, Au–MnO2 NPs, and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (1 W/cm2, 808 nm, 10 min). (B) The photothermal images of prepared samples under continuous laser irradiation, corresponding to Fig. 2A. (C) The photothermal-conversion performance of Au–MnO2 NPs and FTY720@T7-TL NPs over four repeated laser on/off circles (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). (D) In vitro cumulative release profiles of FTY720 from FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0. (E) In vitro NIR-triggered release profiles of FTY720 from FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0. (F) In vitro oxygen production of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 5.0 in the presence of H2O2 solutions (100 μM).

3.3. In vitro drug release behavior

The encapsulation efficiency and loading content of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were 85.6 ± 2.3% and 8.7 ± 0.5%, respectively. The in vitro release of FTY720 was performed at pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0, mimicking the pH states of blood circulation, tumor microenvironment, and acidic lysosomes, respectively (Fig. 2D). The cumulative drug release of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs was highest at pH 5.0, followed by pH 6.5 and pH 7.4. At 48 h, the release amount of FTY720 at pH 5.0 and pH 6.5 were 1.9-fold and 1.5-fold higher than that at pH7.4, respectively. We further investigated the release behavior of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs in NIR laser-switched mode, confirming the accelerated drug release in response to NIR at different pH conditions (Fig. 2F). Under on-mode of NIR irradiation, the release rate of FTY720 was much higher than that of off-mode at the same pH condition. After 1 h, the NIR-triggered drug release of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs was 33.9 ± 1.8%, almost 3.9-fold higher than that without NIR-triggered at pH 5.0. For pH 6.0 and pH 7.4, NIR-triggered drug release was 4.5-fold and 4.0-fold higher than that of the sample groups without NIR-triggered under the same pH condition, respectively. These results demonstrated that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could achieve a sustained drug release through pH-response (endogenous stimulation), as well as a controllable drug release through NIR-response (exogenous stimulation).

The pH-responsive drug release could be attributed to the presence of CHEMS in the hybrid-liposome, which would be protonated and change the structure in an acidic environment [65]. This would result the prepared NPs unstable at acidic environments, accelerating the release of FTY720. The NIR-triggered drug release could be attributed to the presence of DPPC in the hybrid-liposome, which has a phase transition temperature of 41 °C. Under NIR irradiation, the temperature of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs increased above 45 °C (Fig. 2A, B, and 2C), which would result in partial melting of DPPC-containing liposome layer, accelerating the release of FTY720 from the prepared NPs. By controlling the efficient enrichment and effective release of drugs at the tumor site, the anticancer effect could be improved and the damage to surrounding normal tissues would be reduced [[26], [27], [28], [29]].

3.4. In vitro O2 production

The ability of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs to generate oxygen under different pH conditions was evaluated by a dissolved oxygen meter at pH 5.0, 6.5 and 7.4 in the presence of H2O2 (100 μM). As shown in Fig. 2F, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could effectively catalyze the decomposition of H2O2 to produce O2 at pH 5.0 and 6.5, which were 4.6-fold and 3.9-fold higher than those at pH 7.4, respectively. The higher O2 generation rate of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at acidic environments could be attributed to the presence of Au–MnO2 NPs. As shown in Scheme 1, after protonation of CHEMS (partial outer layer of the prepared NPs) in an acidic environment, the prepared NPs were unstable. It would result more Au–MnO2 NPs and FTY720 released when compared to pH 7.4. Our result confirmed acidic environments accelerated the release of FTY720 from the prepared NPs (Fig. 2D and F). Similarly, the acidic environments could also promote the release of Au–MnO2 NPs from the prepare NPs, thereby enhancing the production of O2 in TME.

3.5. In vitro synergistic anticancer effects

In vitro cytotoxicity of the prepared NPs on cells were performed using a CCK8 assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, all treatment groups showed a FTY720 concentration-dependent cytotoxicity towards HepG2 cells. Compared with the other groups, the cells cultured with FTY720@T7-TL NPs + Laser showed the lowest survival rate. At a concentration of 10 μM, the cell viability of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser was 24.86 ± 2.30%, followed by FTY720@AM/TL + Laser NPs of 30.14 ± 1.36%, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs of 54.51 ± 6.48%, FTY720@AM/TL NPs of 64.10 ± 1.67%, and FTY720 of 73.87 ± 1.59%. Under the same conditions, the targeting groups (i.e., FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP + Laser) showed a higher toxicity compared to that of the non-targeting groups (FTY720@AM/TL NP or FTY720@AM/TL NP + Laser). This could be attributed to modification of T7 peptide on NPs, which could increase the cellular uptake and the bioavailability of the prepared NPs. Furthermore, under the same conditions, the NIR-triggered groups (i.e., FTY720@AM/TL + Laser NP or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP + Laser) showed a higher toxicity compared to that of the non-NIR-triggered groups (FTY720@AM/TL NP or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP). This could be attributed to the synergistic effects of combined PTT, PDT and chemotherapy (Scheme 1 and Fig. 2).

The cytotoxicity of the prepared nanocarrier on normal cells (L02) were also investigated using a CCK8 assay (Fig. 3B). When the concentration of F720 less than or equal to 10 μM, the cell viability of L02 cells incubated with all treatment group was above 80%. This result indicated that the prepared NPs (≤10 μM) and the parameter of NIR treatment (1 W/cm2, 808 nm, 10 min) had low cytotoxicity to normal cells. The apoptosis of HepG2 cells incubated with different treatment groups were analyzed by flow cytometry using an Annexin V/PI kit (Fig. 3C). Except for PBS and Control groups, all the treatment groups could induce apoptosis of HepG2 cells. The cell survival rate of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser group was the 26.6%; followed by FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser group with 28.0%; FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs group with 50.7%; and FTY720@AM/TL NPs group with 62.4%. The NIR-triggered groups (i.e., FTY720@AM/TL + Laser NP or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP + Laser) showed the lowest cell viability compared to that of the non-NIR-triggered groups (FTY720@AM/TL NP or FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP). The NIR laser irradiation could control the rapid drug release of the prepared nanoparticles in the lesion area. In this way, more Au–MnO2 NPs would be released from the prepared NPs (Fig. 2E), and then reacted with overexpressed endogenous hydrogen peroxide to generate oxygen. Subsequently, oxygen enrichment could improve the performance of Au–MnO2 NPs to generation more ROS under NIR laser irradiation. The accumulation of FTY720 and the increase of ROS would lead to irreversible cell apoptosis. Therefore, the NIR-triggered group successfully enhanced the synergistic therapeutic effect when compared to the non-NIR-triggered group. Furthermore, with the aid of T7 peptide, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser group could actively target to tumor cells, showing the strongest antitumor effect compared with other treatment groups. A Live/Dead staining assay was also used to evaluate the anticancer effect of the prepared NPs on HepG2 cells (Fig. 3D). After 24 h of co-culture, only a few amount of red signals was observed in the groups of (a) PBS and (b) FTY720, indicating only a small amount of cell death. The group (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser showed the strongest red signal intensities and the least green signal intensities compared to the other groups. This result was consistent with apoptosis and cell vitality assay of HepG2 (Fig. 2A and C), indicating that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser had the highest anti-tumor activity compared with the other groups. Anti-proliferative ability is another important anti-cancer evaluation index. Colony formation assay, a survival test based on the ability of an initial single cell to proliferate into colonies [66], was used to evaluate the proliferative capacity of HepG2 cell after different treatment. As shown in Fig. 3E, both FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs and FTY720@AM/TL NPs had strong anti-proliferation effects on HepG2 cells. Under the NIR laser irradiation, HepG2 cells treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs formed the least number of colonies compared to the other treatment groups. These in vitro synergistic anticancer results demonstrated that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs combined with NIR-treatment could effectively kill tumor cells. This could be attributed to synergistic effects of PTT, PDT and chemotherapy. The high cellular ROS level and local hyperthermia induced by the NIR laser could cause irreversible damage and promote the cancer cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, the drug release triggered by NIR would accelerate the release of FTY720 from FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs.

3.6. Intercellular uptake and ROS generation studies

After co-cultured with HepG2 cells for 6 h, the intercellular localization of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs with or without NIR laser treatment was assessed by CLSM (Fig. 4A). Compared with the non-targeted group, the cells treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (targeted group) showed stronger red fluorescence intensity, indicated that more TPE molecules were distributed in the cytoplasm. This might be due to the fact that through the modification of T7, the prepared NPs would target tumor lesion more precisely, increasing the efficiency of cellular uptake. Compared to the non-NIR-treatment (i.e., FTY720@AM/TL and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs), the same set of NPs groups under the NIR-treatment (i.e., FTY720@AM/TL + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser) showed stronger red fluorescence intensity. The mean fluorescence intensity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser was approximately 26% higher than that of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, while the mean fluorescence intensity of FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser was approximately 14% higher than that of FTY720@AM/TL NPs. Under the same conditions, NIR would trigger the release of more drugs to the designated area (Fig. 2E). Therefore, for the NIR-triggered groups (i.e., FTY720@AM/TL + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser), there would be more TPE released compared to that of non-trigger groups, resulting a higher fluorescence intensity.

Fig. 4.

Intercellular uptake and ROS generation. (A) CLSM images of HepG2 cells incubated with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs with or without irradiation treatment (Laser: 1 W/cm2, 808 nm, 10 min), scale bar 50 μm. (B) Intracellular ROS generation of HepG2 cells incubated with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs with or without NIR treatment (1 W/cm2, 808 nm, 10 min), scale bar 25 μm.

The intercellular ROS generation capacity of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs was measured by a ROS indicator (DCFH-DA), which could be oxidized by ROS to green fluorescent DCF. As shown in Fig. 4B, both FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs groups exhibited weak green fluorescence intensity, indicating the generation of a small amount of ROS. The NIR-triggered groups, i.e., FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, showed much stronger green fluorescence intensity compared to the non-NIR-triggered groups. In addition, the green fluorescence signal of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser group was stronger than that of FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser group. The ROS enhancement could be attributed to the active targeting and charge-reversal properties of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, which enriched the prepared NPs in tumor cells and then endocytosed by tumor cells.

The hypoxic tumor microenvironment limits the performance of Au NPs to generate ROS under NIR laser irradiation, resulting the failure of PDT [[44], [45], [46], [47]]. After being endocytosed by tumor cells, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could be rapidly decomposed under laser irradiation and in the acidic TME (Fig. 2E), followed by the release of Au–MnO2 NPs. The Au–MnO2 NPs could induce the catalytic decomposition of endogenous H2O2 to generate oxygen, alleviating hypoxia. This in situ oxygen production could inhibit tumor cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis in ROS-stressed cancer cells. The generated intracellular ROS could also induce DNA damage, activating the signaling pathways of p53, AKT and MAPKs.

3.7. Western blot study

Western blot results showed that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser group could remarkably up-regulate the DNA damage relative protein p-H2A.X, as well as the phosphorylation of P53, activating the AKT and MAPKs family phosphorylation kinases (Fig. 5A). Meanwhile, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser remarkably up-regulated cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP proteins in HepG2 cells when compared to the other groups. This result indicated that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser could simultaneously activate exogenous and endogenous signaling pathways in HepG2 cells to induce tumor cell apoptosis (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Activation of intracellular apoptotic signaling pathways by FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs and NIR laser irradiation. (A) Western blot assays of proteins for apoptosis and DNA damage in HepG2 cells incubated with different treatment groups. The NIR-treatment groups, i.e., FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). (B) Illustration of potential mechanisms (enhanced ROS and induced apoptosis) of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NP combined with NIR in HCC treatment.

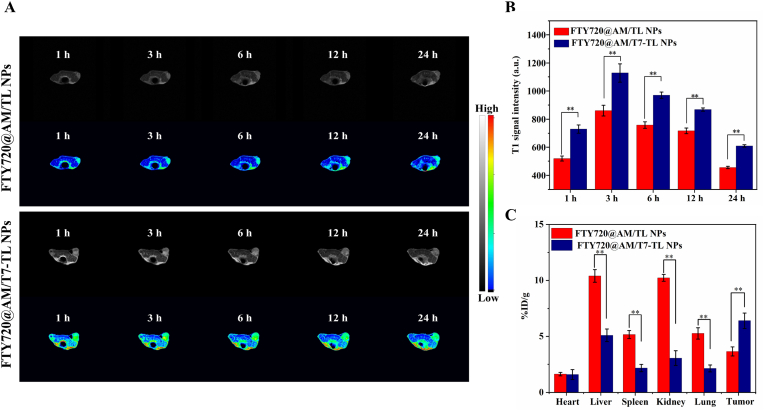

3.8. In vivo dual-modal imaging, biodistribution and pharmacokinetic studies

The in vivo AIE fluorescence images of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were evaluated at different post-injection time points. Both FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs had good fluorescence imaging ability (Fig. 6A). Compared with the other post-injection time points, the mean fluorescence of these two prepared NP in the tumor area was the strongest at 3 h post-injection (Fig. 6B). At the same post-injection time points (within 24 h), the group of mice treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed a stronger fluorescence signal at tumor sites than that of the group of FTY720@AM/TL NPs. This result indicated that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could accumulate more efficiently in the tumor than FTY720@AM/TL NPs.

Fig. 6.

Fluorescence imaging properties of the prepared NPs in vivo. (A) In vivo AIE fluorescence images of HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice injected with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. (B) In vivo mean fluorescence signal intensity of the tumor area at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. (C) Ex vivo images of major organs and tumors collected at 24 h. (D) Mean fluorescence signal intensity of ex vivo major organs and tumors collected at 24 h (corresponding to Fig. 6C).

The ex vivo fluorescence images of major organs and tumor was obtained 24 h after injection. The results showed that the tumors of the mice treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs had the strongest fluorescence signal than the other metabolic organs (Fig. 6C). In addition, the mean fluorescence intensity of FTY720@AM/TL NPs in the tumor areas was 2.4-times higher than that of FTY720@AM/TL NPs (Fig. 6D). These results indicating the in vivo tumor-targeting ability of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could promote the enrichment of nanocarriers at tumor sites.

The in vivo T1-weighted MR images of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs were evaluated at different post-injection time points. Both FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs had good MRI ability (Fig. 7A). Compared with FTY720@AM/TL NPs, the tumor area of mice treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed a brightening effect. Compared with the other post-injection time points, the T1 signal intensity of these two prepared NP in the tumor area was the strongest at 3 h post-injection (Fig. 7B). At the same post-injection time points (within 24 h), the group of mice treated with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed a stronger T1 signal at tumor sites than that of the group of FTY720@AM/TL NPs. These results were consisted with the fluorescent imaging study (Fig. 6), indicating that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs with T7 modification could effectively enhance tumor targeting effects.

Fig. 7.

In vivo T1-weighted MR imaging properties. (A) In vivo T1-weight MR images of HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice after injection with FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. (B) In vivo T1 signal intensity of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 h. (C) Biodistribution of Mn content 24 h after injection of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs.

The major organs and tumor were collected at 24 h post-injection, and Mn element was determined by ICP to quantitative analysis the biodistribution of FTY720@AM/TL NPs and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs. The result showed that Mn ions mainly accumulated in liver (10.4 ± 0.6% ID/g) and kidney (10.2 ± 0.3% ID/g) in the group of mice treated with FTY720@AM/TL NPs. This might be attributed to macrophage uptake in the reticuloendothelial system. FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs showed higher Mn content in tumors (6.4 ± 0.7% ID/g), which was approximately 1.8-fold higher than that of FTY720@AM/TL NPs group (3.6 ± 0.6% ID/g). This might be attributed to the fact that T7 peptide-modified nanocarriers could improve tumor targeting efficiency and facilitate the enrichment of nanocomposites at tumor sites.

To accurately characterize the blood circulation behavior of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, the blood retention of Au in peripheral blood of mice was monitored over 24 h (Fig. S22). The blood levels of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs gradually decreased over time. The kinetic changes of Au were fitted by a two-compartment model, and the half-lives of the first and second stages were 0.16 and 4.37 h, respectively. The relatively long circulation time of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs in blood facilitated their efficient accumulation in tumors.

3.9. In vivo photothermal ability of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs

To investigate the in vivo photothermal effects of the prepared nanoplatforms, thermal images and temperature changes during NIR irradiation were recorded in tumor-bearing mice treated with PBS, FTY720@AM/TL NPs, and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs (Fig. 8A). After 10-min NIR-treatment, the tumor surface temperature of FTY720@AM/TL NPs group increased from 35.7 °C to 41.2 °C, while that of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs group increased from 35.1 °C to 50.8 °C. Compared with FTY720@AM/TL NPs, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs had a better tumor targeting ability and could be more efficiently enriched around tumor sites. Therefore, compared with FTY720@AM/TL NPs, the tumor surface temperature of mice injected with FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs increased faster under the same irradiation time. The elevated temperature induced by NIR-treatment was more favorable to PTT and PDT, which also promoted the disintegration of FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs in the tumor. This would enable rapid release of the drug and enhance the synergistic therapeutic effect.

Fig. 8.

In vivo synergistic treatment of HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice model. (A) In vivo infrared thermal images of tumor-bearing mice at 6th h after injected with PBS, FTY720@AM/TL and FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm). (B) The temperature change profiles of tumor site, corresponding to treatment-groups in Fig. 8A. (C) The Change in relative tumor volume of mice with different treatment groups. (D) The change in body weight of mice with different treatment groups. (E) Plot of tumor weight of mice with different treatment groups at day 14. (F) Photographs of tumors collected from mice with different treatment groups at day 14. (G) H&E staining of tumor sections collected from different treatment groups, scale bar 50 μm. For panels C, D, E, F, and G, the treatment groups were (a) PBS, (b) FTY720, (c) FTY720@AM/TL NPs, (d) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser, and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser. The NIR-treatment groups, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm).

3.10. In vivo synergistic anticancer effect

The in vivo synergistic anticancer effects of prepared nanoplatform were evaluated by the HepG2 tumor-bearing nude mice. As shown in Fig. 8C, group (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser showed the best tumor suppression, followed by groups (f) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser, (d) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, (c) FTY720@AM/TL NPs, (b) FTY720, and (a) PBS. Mice body weights were also monitored during the 14-day treatment period to evaluate treatment-associated toxicity (Fig. 8D). There were no abnormal changes in weight were found in each treatment group, suggesting that the prepared NPs exhibited good biocompatibility in vivo. The average weight (Fig. 8E) and images of tumors collected after the treatment period (Fig. 8F) also showed that the group (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser irradiation group exhibited the best therapeutic effects compared to the other groups. At 14th day, tumor tissues were extracted and sectioned for H&E staining to verify the in vivo therapeutic effect (Fig. 8G). Group (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser showed a large amounts of tumor tissue necrosis, groups (c) FTY720@AM/TL NPs, (d) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser showed partial tumor tissue necrosis, while groups (a) PBS and (b) FTY720 showed little tissue necrosis. Furthermore, the survival rate study (Fig. S23) suggested that of Group (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser had the best survival rate compared with the other groups, with 90% of the treated mice still alive at 45 days.

These results indicated that the prepared nanoplatform (e) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser had the strongest anti-tumor effect, when compared to the other groups. As T7 peptide modification could improve the tumor targeting efficiency of the prepared NPs, FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs could be more efficiently enriched in tumor sites with a better photothermal conversion effect compared to the non-targeting NPs. Furthermore, Au–MnO2 NPs encapsulated in the nanocarriers could be rapidly released in the tumor area, reacted with endogenous hydrogen peroxide to generate oxygen, alleviated tumor hypoxia, and enhanced the PDT effects. The heat generated by FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs induced by NIR-treatment could promote the Fenton-like reaction rate of Mn2+, thereby increasing the release of hydroxyl radicals and enhancing the synergistic therapeutic effects.

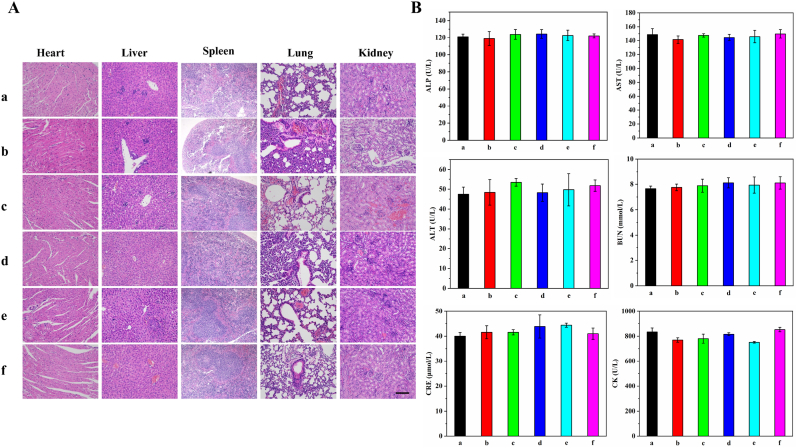

3.11. Biosafety

The potential in vivo toxicity and side effect of the prepared NPs were evaluated by H&E staining and blood biochemical analysis (Fig. 9). Mice were sacrificed after 14 days of treatment, and their major organs were collected for H&E staining. There was little difference in cell morphology and nuclear structure of these organs among different treatment groups (Fig. 9A). Serum biochemical analyses were performed to investigate the in vivo long-term biosafety of the prepared NPs (Fig. 9B). The liver function indexes (ALP, AST, ALT), renal function indexes (BUN, CRE), and myocardial function index (CK) in each treatment group were all within the normal range. These results suggested that the prepared NPs had good biocompatibility for in vivo application.

Fig. 9.

Long-term toxicity of the prepared NPs. (A) H&E staining of major organs after 14 days' treatment, scale bar 50 μm. (B) Blood biochemical analysis of the mice with different treatment groups on the 14th day. The treatment groups were (a) PBS, (b) FTY720, (c) FTY720@AM/TL NPs, (d) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser, and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser. The NIR-treatment groups, (e) FTY720@AM/TL NPs + Laser and (f) FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs + Laser, were subjected to a laser treatment for 10 min (1 W/cm2, 808 nm).

4. Conclusion

An all-in-one HCC therapeutic nanoplatform (FTY720@AM/T7-TL) has been successfully designed and well characterized in the present study. The dual pH/NIR laser-responsive and tumor targeting properties enhance the accumulation of the multi-purpose NPs (FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs) at tumor sites and reduced unnecessary drug leakage through “on-demand” drug release. In acidic and H2O2-rich tumor microenvironment, Au–MnO2 NPs within the platform could catalyze tumor-overexpressed H2O2 to generate O2. This led to a series of chain reactions, which alleviated tumor hypoxia, enhanced PDT efficacy, and released Mn2+ for T1-weighted MRI. The incorporation of a tumor targeting peptide, T7, further provided the nanoplatform an effective way to accurately diagnose tumors through dual-modal imaging. Both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that FTY720@AM/T7-TL NPs had good synergistic anti-tumor effects. The biosafety analysis of the nanoplatform showed negligible in vivo toxicity to most major organs. Overall, through the design of this all-in-one platform in the present study, we hope to bring novel insights to HCC therapy as well as cancer therapy in general.

Credit author statement

Taiying Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing-original draft. Ngalei Tam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. Yu Mao: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing. Chengjun Sun: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation. Zekang Wang: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation. Yuchen Hou: Formal analysis, Resources, Validation. Wuzheng Xia: Investigation, Validation. Jia Yu: Investigation, Validation. Linwei Wu: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by NSFC Incubation Program of Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital of Guangdong province, China (No. KY012021148); Summit Plan of high-quality hospital of Guangdong province, China (No. KJ012020637). This work was also finnancially supported by National Key Clinical Specialty Construction Project, China (2021-2024, No. 2022 YW03009).

We thank Dr. Xu Li, from the Department of Chemical Engineering and the Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, The University of Melbourne, for help edit the English text of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100338.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Saner F., Herschtal A., Nelson B., deFazio A., Goode E., Ramus S., Pandey A., Beach J., Fereday S., Berchuck A., Lheureux S., Pearce C., Pharoah P., Pike M., Garsed D., Bowtell D. Going to extremes: determinants of extraordinary response and survival in patients with cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2019;19(6):339–348. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0145-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R., Torre L., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serper M., Parikh N., Thiele G., Ovchinsky N., Mehta S., Kuo A., Ho C., Kanwal F., Volk M., Asrani S., Ghabril M., Lake J., Merriman R., Morgan T., Tapper E. Patient-reported outcomes in HCC: a scoping review by the practice metrics committee of the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2022;76(1):251–274. doi: 10.1002/hep.32313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Toni E., Schlesinger-Raab A., Fuchs M., Schepp W., Ehmer U., Geisler F., Ricke J., Paprottka P., Friess H., Werner J., Gerbes A., Mayerle J., Engel J. Age independent survival benefit for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) without metastases at diagnosis: a population-based study. Gut. 2020;69(1):168–176. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-318193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu J., Wang J., Ling D. Surface engineering of nanoparticles for targeted delivery to hepatocellular carcinoma. Small. 2018;14(5):25. doi: 10.1002/smll.201702037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You Q., Sun Q., Yu M., Wang J., Wang S., Liu L., Cheng Y., Wang Y., Song Y., Tan F., Li N. BSA-bioinspired gadolinium hybrid-functionalized hollow gold. Nanoshells for NIRF/PA/CT/MR quadmodal diagnostic imaging guided photothermal/photodynamic cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(46):40017–40030. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b11926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyu M., Zhu D., Duo Y., Li Y., Quan H. Bimetallic nanodots for tri-modal CT/MRI/PA imaging and hypoxia-resistant thermoradiotherapy in the NIR-II biological windows. Biomaterials. 2020;233 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang W., Xiang C., Xu Y., Chen S., Zeng W., Liu K., Jin X., Zhou X., Zhang B. Albumin-constrained large-scale synthesis of renal clearable ferrous sulfide quantum dots for T-Weighted MR imaging and phototheranostics of tumors. Biomaterials. 2020;255 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J., Ni D., Bu W., Zhou Q., Fan W., Wu Y., Liu Y., Yin L., Cui Z., Zhang X., Zhang H., Yao Z. BaHoF5 nanoprobes as high-performance contrast agents for multi-modal CT imaging of ischemic stroke. Biomaterials. 2015;71:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai Y., Su J., Wu K., Ma W., Wang B., Li M., Sun P., Shen Q., Wang Q., Fan Q. Multifunctional thermosensitive liposomes based on natural phase-change material: near-infrared light-triggered drug release and multimodal imaging-guided cancer combination therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(11):10540–10553. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b22748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S., Jiang W., Yuan Y., Sui M., Yang Y., Huang L., Jiang L., Liu M., Chen S., Zhou X. Delicately designed cancer cell membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles for targeted F MR/PA/FL imaging-guided photothermal therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(51):57290–57301. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c13865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., Song S., Lu T., Cheng Y., Song Y., Wang S., Tan F., Li J., Li N. Oxygen-supplementing mesoporous polydopamine nanosponges with WS QDs-embedded for CT/MSOT/MR imaging and thermoradiotherapy of hypoxic cancer. Biomaterials. 2019;220 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siddique S., Chow J.C.L. Application of nanomaterials in biomedical imaging and cancer therapy. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(9):40. doi: 10.3390/nano10091700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J., Zou H., Lei J., He B., He X., Sung H., Kwok R., Lam J., Zheng L., Tang B. Multifunctional Au-I-based AIEgens: manipulating molecular structures and boosting specific cancer cell imaging and theranostics. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020;59(18):7097–7105. doi: 10.1002/anie.202000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y., Zhao J., Chen Z., Zhang F., Wang Q., Guo W., Wang K., Lin H., Qu F. Construct of MoSe2/Bi2Se3 nanoheterostructure: multimodal CT/PT imaging-guided PTT/PDT/chemotherapy for cancer treating. Biomaterials. 2019;217:13. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu X., Kwok R., Lam J., Tang B. AIEgens for biological process monitoring and disease theranostics. Biomaterials. 2017;146:115–135. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mu W., Chu Q., Liu Y., Zhang N. A review on nano-based drug delivery system for cancer chemoimmunotherapy. Nano-Micro Lett. 2020;12(1):142. doi: 10.1007/s40820-020-00482-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Li S., Wang X., Chen Q., He Z., Luo C., Sun J. Smart transformable nanomedicines for cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2021;271 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang M., Chan S., Goh Y., Luo Z., Lau J., Liu X. Emerging strategies in developing multifunctional nanomaterials for cancer nanotheranostics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021;178 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2021.113907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mi P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, tumor imaging, therapy and theranostics. Theranostics. 2020;10(10):4557–4588. doi: 10.7150/thno.38069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J., Shi J., Nie W., Wang S., Liu G., Cai K. Recent progress in the development of multifunctional nanoplatform for precise tumor phototherapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021;10(1) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmadi S., Rabiee N., Bagherzadeh M., Elmi F., Fatahi Y., Farjadian F., Baheiraei N., Nasseri B., Rabiee M., Dastjerd N., Valibeik A., Karimi M., Hamblin M. Stimulus-responsive sequential release systems for drug and gene delivery. Nano Today. 2020;34 doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen M., Song F., Liu Y., Tian J., Liu C., Li R., Zhang Q. A dual pH-sensitive liposomal system with charge-reversal and NO generation for overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer. Nanoscale. 2019;11(9):3814–3826. doi: 10.1039/c8nr06218h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang T., Zhang Z., Zhang Y., Lv H., Zhou J., Li C., Hou L., Zhang Q. Dual-functional liposomes based on pH-responsive cell-penetrating peptide and hyaluronic acid for tumor-targeted anticancer drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2012;33(36):9246–9258. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q., Tian Y., Liu L., Chen C., Zhang W., Wang L., Guo Q., Ding L., Fu H., Song H., Shi J., Duan Y. Precise targeting therapy of orthotopic gastric carcinoma by siRNA and chemotherapeutic drug codelivered in pH-sensitive nano platform. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202100966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H., Du J., Liu J., Du X., Shen S., Zhu Y., Wang X., Ye X., Nie S., Wang J. Smart superstructures with ultrahigh pH-sensitivity for targeting acidic tumor microenvironment: instantaneous size switching and improved tumor penetration. ACS Nano. 2016;10(7):6753–6761. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b02326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J., Chen, Feng L., Liu Z. Nanomedicine for tumor microenvironment modulation and cancer treatment enhancement. Nano Today. 2018;21:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai M., Lo Y., Soorni Y., Su C., Sivasoorian S., Yang J., Wang L. Near-infrared light-triggered drug release from ultraviolet- and redox-responsive polymersome encapsulated with core-shell upconversion nanoparticles for cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021;4(4):3264–3275. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.0c01621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohamed M., Veeranarayanan S., Maekawa T., Kumar D. External stimulus responsive inorganic nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019;138:18–40. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Böttger R., Pauli G., Chao P., Al Fayez N., Hohenwarter L., Li S. Lipid-based nanoparticle technologies for liver targeting. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020:79–101. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou L., Wu Y., Meng X., Li S., Zhang J., Gong P., Zhang P., Jiang T., Deng G., Li W., Sun Z., Cai L. Dye-anchored MnO nanoparticles targeting tumor and inducing enhanced phototherapy effect via mitochondria-mediated pathway. Small. 2018;14(36) doi: 10.1002/smll.201801008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh R., Norret M., House M., Galabura Y., Bradshaw M., Ho D., Woodward R., St Pierre T., Luzinov I., Smith N., Lim L., Iyer K. Dose-dependent therapeutic distinction between active and passive targeting revealed using transferrin-coated PGMA nanoparticles. Small. 2016;12(3):351–359. doi: 10.1002/smll.201502730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang J., Wang Q., Yu Q., Qiu Y., Mei L., Wan D., Wang X., Li M., He Q. A stabilized retro-inverso peptide ligand of transferrin receptor for enhanced liposome-based hepatocellular carcinoma-targeted drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2019;83:379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu F., Wang F., Dong X., Xiu P., Sun P., Li Z., Shi X., Zhong J. T7 peptide cytotoxicity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells is mediated by suppression of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019;44(2):523–534. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han L., Huang R., Liu S., Huang S., Jiang C. Peptide-conjugated PAMAM for targeted doxorubicin delivery to transferrin receptor overexpressed tumors. Mol. Pharm. 2010;7(6):2156–2165. doi: 10.1021/mp100185f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dicheva B., ten Hagen T., Li L., Schipper D., Seynhaeve A., van Rhoon G., Eggermont A., Lindner L., Koning G. Cationic thermosensitive liposomes: a novel dual targeted heat-triggered drug delivery approach for endothelial and tumor cells. Nano Lett. 2013;13(6):2324–2331. doi: 10.1021/nl3014154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du J., Sun T., Song W., Wu J., Wang J. A tumor-acidity-activated charge-conversional nanogel as an intelligent vehicle for promoted tumoral-cell uptake and drug delivery. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49(21):3621–3626. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan Y., Mao C., Du X., Du J., Wang F., Wang J. Surface charge switchable nanoparticles based on zwitterionic polymer for enhanced drug delivery to tumor. Adv. Mater. 2012;24(40):5476–5480. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuang J., Gordon M., Ventura J., Li L., Thayumanavan S. Multi-stimuli responsive macromolecules and their assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42(17):7421–7435. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60094g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen S., Rong L., Lei Q., Cao P., Qin S., Zheng D., Jia H., Zhu J., Cheng S., Zhuo R., Zhang X. A surface charge-switchable and folate modified system for co-delivery of proapoptosis peptide and p53 plasmid in cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2016;77:149–163. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thienpont B., Steinbacher J., Zhao H., D'Anna F., Kuchnio A., Ploumakis A., Ghesquière B., Van Dyck L., Boeckx B., Schoonjans L., Hermans E., Amant F., Kristensen V., Peng Koh K., Mazzone M., Coleman M., Carell T., Carmeliet P., Lambrechts D. Tumour hypoxia causes DNA hypermethylation by reducing TET activity. Nature. 2016;537(7618):63–68. doi: 10.1038/nature19081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakazawa M., Keith B., Simon M. Oxygen availability and metabolic adaptations. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2016;16(10):663–673. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raz S., Sheban D., Gonen N., Stark M., Berman B., Assaraf Y.G. Severe hypoxia induces complete antifolate resistance in carcinoma cells due to cell cycle arrest. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:9. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui X., Lu G., Dong S., Li S., Xiao Y., Zhang J., Liu Y., Meng X., Li F., Lee C. Stable π-radical nanoparticles as versatile photosensitizers for effective hypoxia-overcoming photodynamic therapy. Mater. Horiz. 2021;8(2):571–576. doi: 10.1039/d0mh01312a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo H., Huang C., Chen J., Yu H., Cai Z., Xu H., Li C., Deng L., Chen G., Cui W. Biological homeostasis-inspired light-excited multistage nanocarriers induce dual apoptosis in tumors. Biomaterials. 2021;279 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao Y., Zhang L., Chen Z., Zheng B., Ke M., Li X., Huang J. Nanostructured phthalocyanine assemblies with efficient synergistic effect of type I photoreaction and photothermal action to overcome tumor hypoxia in photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143(34):13980–13989. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c07479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song Y., Shi Q., Zhu C., Luo Y., Lu Q., Li H., Ye R., Du D., Lin Y. Mitochondrial-targeted multifunctional mesoporous Au@Pt nanoparticles for dual-mode photodynamic and photothermal therapy of cancers. Nanoscale. 2017;9(41):15813–15824. doi: 10.1039/c7nr04881e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng Y., Cheng H., Jiang C., Qiu X., Wang K., Huan W., Yuan A., Wu J., Hu Y. Perfluorocarbon nanoparticles enhance reactive oxygen levels and tumour growth inhibition in photodynamic therapy. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian H., Luo Z., Liu L., Zheng M., Chen Z., Ma A., Liang R., Han Z., Lu C., Cai L. Cancer cell membrane-biomimetic oxygen nanocarrier for breaking hypoxia-induced chemoresistance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017;27(38):7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu D., Zhong L., Wang M., Li H., Qu Y., Liu Q., Han R., Yuan L., Shi K., Peng J., Qian Z. Perfluorocarbon-loaded and redox-activatable photosensitizing agent with oxygen supply for enhancement of fluorescence/photoacoustic imaging guided tumor photodynamic therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29(9):14. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Z., Niu M., Chen G., Wu Q., Tan L., Fu C., Ren X., Zhong H., Xu K., Meng X. Oxygen production of modified core-shell CuO@ZrO2 nanocomposites by microwave radiation to alleviate cancer hypoxia for enhanced chemo-microwave thermal therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12(12):12721–12732. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jia Q.Y., Ge J.C., Liu W.M., Zheng X.L., Chen S.Q., Wen Y.M., Zhang H.Y., Wang P.F. A magnetofluorescent carbon dot assembly as an acidic H2O2-driven oxygenerator to regulate tumor hypoxia for simultaneous bimodal imaging and enhanced photodynamic therapy. Adv. Mater. 2018;30(13):10. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu J., Wang Z., Zhang G., Lu X., Qiang G., Hu W., Ji A., Wu J., Jiang C. Targeted co-delivery of Beclin 1 siRNA and FTY720 to hepatocellular carcinoma by calcium phosphate nanoparticles for enhanced anticancer efficacy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:1265–1280. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S156328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li C., Shao Y., Ng K., Liu X., Ling C., Ma Y., Geng W., Fan S., Lo C., Man K. FTY720 suppresses liver tumor metastasis by reducing the population of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hung J., Lu Y., Wang Y., Ma Y., Wang D., Kulp S., Muthusamy N., Byrd J., Cheng A., Chen C. FTY720 induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through activation of protein kinase C delta signaling. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):1204–1212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin J., Hou Y., Huang S., Wang Z., Sun C., Wang Z., He X., Tam N., Wu C., Wu L. Exportin-T promotes tumor proliferation and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2019;58(2):293–304. doi: 10.1002/mc.22928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paasonen L., Sipilä T., Subrizi A., Laurinmäki P., Butcher S., Rappolt M., Yaghmur A., Urtti A., Yliperttula M. Gold-embedded photosensitive liposomes for drug delivery: triggering mechanism and intracellular release. J. Contr. Release. 2010;147(1):136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fan Y., Chen C., Huang Y., Zhang F., Lin G. Study of the pH-sensitive mechanism of tumor-targeting liposomes. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2017;151:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H., Du J., Du X., Xu C., Sun C., Wang H., Cao Z., Yang X., Zhu Y., Nie S., Wang J. Stimuli-responsive clustered nanoparticles for improved tumor penetration and therapeutic efficacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016;113(15):4164–4169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522080113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hua S., He J., Zhang F., Yu J., Zhang W., Gao L., Li Y., Zhou M. Multistage-responsive clustered nanosystem to improve tumor accumulation and penetration for photothermal/enhanced radiation synergistic therapy. Biomaterials. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fang J., Islam W., Maeda H. Exploiting the dynamics of the EPR effect and strategies to improve the therapeutic effects of nanomedicines by using EPR effect enhancers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;157:142–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]