ABSTRACT

The family of human papillomaviruses (HPV) includes over 400 genotypes. Genus α genotypes generally infect the anogenital mucosa, and a subset of these HPV are a necessary, but not sufficient, cause of cervical cancer. Of the 13 high-risk (HR) and 11 intermediate-risk (IR) HPV associated with cervical cancer, genotypes 16 and 18 cause 50% and 20% of cases, respectively, whereas HPV16 dominates in other anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers. A plethora of βHPVs are associated with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC), especially in sun-exposed skin sites of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV), AIDS, and immunosuppressed patients. Licensed L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccines, such as Gardasil 9, target a subset of αHPV but no βHPV. To comprehensively target both α- and βHPVs, we developed a two-component VLP vaccine, RG2-VLP, in which L2 protective epitopes derived from a conserved αHPV epitope (amino acids 17 to 36 of HPV16 L2) and a consensus βHPV sequence in the same region are displayed within the DE loop of HPV16 and HPV18 L1 VLP, respectively. Unlike vaccination with Gardasil 9, vaccination of wild-type and EV model mice (Tmc6Δ/Δ or Tmc8Δ/Δ) with RG2-VLP induced robust L2-specific antibody titers and protected against β-type HPV5. RG2-VLP protected rabbits against 17 αHPV, including those not covered by Gardasil 9. HPV16- and HPV18-specific neutralizing antibody responses were similar between RG2-VLP- and Gardasil 9-vaccinated animals. However, only transfer of RG2-VLP antiserum effectively protected naive mice from challenge with all βHPVs tested. Taken together, these observations suggest RG2-VLP’s potential as a broad-spectrum vaccine to prevent αHPV-driven anogenital, oropharyngeal, and βHPV-associated cutaneous cancers.

IMPORTANCE Licensed preventive HPV vaccines are composed of VLPs derived by expression of major capsid protein L1. They confer protection generally restricted to infection by the αHPVs targeted by the up-to-9-valent vaccine, and their associated anogenital cancers and genital warts, but do not target βHPV that are associated with CSCC in EV and immunocompromised patients. We describe the development of a two-antigen vaccine protective in animal models against known oncogenic αHPVs as well as diverse βHPVs by incorporation into HPV16 and HPV18 L1 VLP of 20-amino-acid conserved protective epitopes derived from minor capsid protein L2.

KEYWORDS: HPV, VLP, L1, L2, cervical cancer, skin cancer, epidermodysplasia verruciformis

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomaviruses (HPV) are small, double-stranded DNA viruses causing papilloma in cutaneous or mucosal epithelia which are divided into five genera (α, β, γ, μ, or ν, based on the sequence of the late 1 [L1] gene [1]). Most HPV infections are asymptomatic or produce benign warts that are eventually controlled by the patient’s immune system. Genus α types primarily infect genital mucosa via sexual contact. Low-risk (LR) HPV, dominated by HPV6/11/40/42/43/44, cause benign genital warts or, less commonly, laryngeal papillomas that only rarely can invade and progress to cancer (2). In contrast, the 13 high-risk (HR) HPVα types (HPV16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/68) are a necessary, but not sufficient, cause of cervical cancer worldwide (3). In addition, there are 11 α types designated intermediate risk (HPV26/30/34/53/66/67/69/70/73/82/85) because they occur as single infections in invasive cervical cancer cases (4, 5). While the goal is elimination of all αHPV with carcinogenic potential, the initial vaccines targeted HPV16 and HPV18 (e.g., Cervarix [6]), as these two types are responsible, respectively, for 50% and 20% of cervical cancers globally. The quadrivalent Gardasil vaccine also included HPV6/11, which cause 90% of benign genital warts (7–9). These vaccines provided robust and durable but predominantly type-restricted protection. Thus, in seeking to prevent a greater fraction of cervical cancers, an expanded-spectrum vaccine, Gardasil 9, was developed to target five additional high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) types (HPV31/33/45/52/58) (10).

The development of the licensed prophylactic HPV vaccines was launched by observation that recombinantly expressed major capsid protein L1 self-assembles into virus-like particles (VLP) lacking the oncogenic viral genome, yet resembling native virions in the ability to induce high-titer and type-restricted neutralizing antibody (11–15). Remarkably, passive transfer of these neutralizing antibodies was sufficient to confer immunity (16–18) apparently via blockade of virion binding to basement membrane and/or transfer to the keratinocyte cell surface (19). The licensed vaccines based on L1 VLP are remarkably effective in protection against infections, induced lesions, and even cancer associated with corresponding vaccine types (20–22). In contrast, there has been little impact on nonvaccine type infections (23).

Immunization with the minor capsid protein L2, which cannot form a VLP without L1, is also protective in animal papillomavirus models against experimental viral challenge (24–26). In contrast to L1 VLP antibody responses, L2 immunization induces low titers of neutralizing antibodies against diverse genotypes that recognize linear epitopes (27). This feature suggests that a simple broadly acting vaccine targeting the conserved protective epitopes of L2 may be possible, especially if specific antibody titers can be enhanced and maintained.

Mapping using cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies identified conserved protective epitopes, such as HPV16 L2 residues 17 to 36 recognized by the monoclonal antibody RG1 (28). Passive transfer of RG1 protected naive mice from experimental cutaneous challenge with HPV pseudovirions (PsV) delivering a luciferase reporter (29). In vitro studies showed that the L2 17 to 36 epitope was exposed on the virion surface only upon binding to the extracellular matrix. This triggers a change in capsid conformation to permit cleavage by the cellular protease furin at a specific highly conserved site in L2 adjacent to its cross-neutralizing epitopes. Unexpectedly, binding of L2 17 to 36 antibody, RG1, led to the release of the capsid-antibody complexes from the cell surface and promoted their accumulation on the extracellular matrix (30, 31). Their clearance via phagocytes is an important component of protection by L2-specific antibodies (29) in addition to direct neutralization (19) with antibodies of sufficient avidity (32).

A variety of approaches have been taken to promote a potent and lasting antibody response against this protective epitope of L2 (33). These include its repetitive, close-packed display by insertion within immunodominant surface epitopes of viral particles, an approach known to promote antibody class switching and long-lived plasma cells (34, 35). Since HPV16 L1 VLP vaccination elicits type-restricted immunity against the most important genotype, and its immunodominant epitopes have been mapped, L1 was a logical candidate for insertion of L2 epitopes. In the native HPV16 capsid, the L2 is mostly buried (30) and at insufficient density to elicit a response in most infected individuals or upon vaccination with L1/L2 VLP (36). Therefore, Schellenbacher et al. inserted the HPV16 L2 amino acids (aa) 17 to 36 epitope into an immunodominant surface (DE) loop of the HPV16 L1 to produce HPV16 RG1-VLP, each displaying 360 copies of this conserved protective epitope on well-formed particles (37). Vaccination with HPV16 RG1-VLP elicited HPV16-neutralizing antibody titers similar to that with native L1 VLP (38); importantly, passive transfer of HPV16 RG1-VLP antiserum, but not HPV16 L1 VLP antiserum or pre-immune serum, protected naive mice against experimental vaginal challenge with 13 HR-HPV and LR HPV6/43/44 that cause benign genital warts, suggesting that it could provide broad protection against αHPV (39).

Both HIV/AIDS and posttransplant immunosuppression profoundly increase risk of αHPV-related precancer and cancers and are associated with more aggressive disease that is harder to treat (40, 41). The burden of cutaneous HPV disease is also substantial among these cohorts. While non-life-threatening typically, these conditions can severely affect patients’ quality of life. Furthermore, there is growing evidence of a causal association between βHPV infection and keratotic lesions leading to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in synergy with UV radiation (sun) damage in immunocompromised populations (42, 43). Such a link first emerged from studies in patients who suffer from epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV) who develop persistent flat warts and macular lesions (44) associated with βHPV HPV5/8/9/12/14/15/17/19-25/36/38, which are not targeted by licensed HPV vaccines and progress at high rates to CSCC in sun-exposed areas. The role of βHPV was demonstrated by inoculation studies, and HPV5/8 are present in 90% of CSCC in EV patients (45). Patients with familial EV have mutations in the TMC6, TMC8, or CIB1 genes (46, 47), while patients with chronic immunosuppression, such as HIV/AIDS or organ transplant recipients (OTR), exhibit acquired EV (44).

The sequence conservation of the HPV16 RG1 epitope is high among the αHPV but is lower for the more diverse βHPV (28, 33). Thus, while the HPV16 RG1-VLP vaccine elicits antibodies that broadly protect against αHPV, a second VLP is likely necessary to optimize protective immunity against the plethora of βHPV. We hypothesized that the protection afforded by HPV16-derived RG1-VLP vaccination toward cutaneous HPV-related disease and cancers could be enhanced by a second construct in which an RG1-like epitope bio-informatically derived as a consensus sequence from L2 of key CSCC-linked βHPVs is inserted within the DE loop of HPV18 L1 VLP. Herein, we describe the development of a two-antigen vaccine, termed RG2-VLP, and test the strength and breadth of its antibody response and protective efficacy against diverse α- and βHPV in rabbits as well as wild-type and EV model mice.

RESULTS

HPV18 L1-derived chimeric VLP construct design and selection.

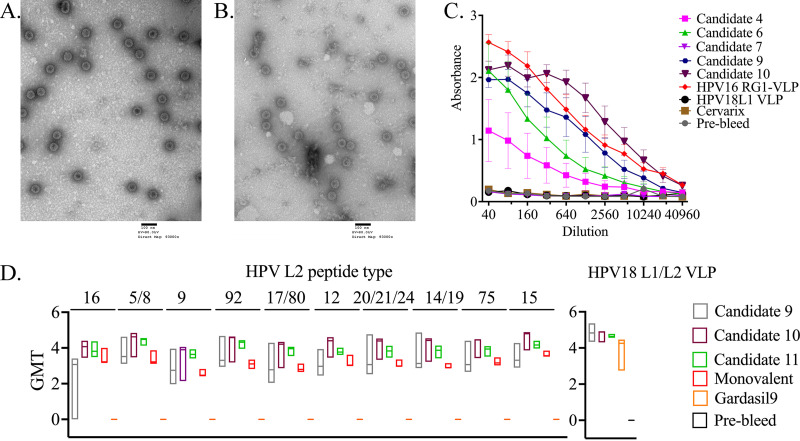

In seeking to better target cutaneous βHPVs, especially those most relevant to EV and CSCC, we initially generated expression constructs encoding codon-optimized HPV18 L1 with different L2 epitope insertions (Table 1). These epitopes were inserted into the immunodominant DE loop of HPV18 L1 VLP between L1 amino acids 134/135 as previously used to create HPV16 RG1-VLP. For candidates 1 to 3, 5, and 7, the inserted epitope targeted the L2 aa 64 to 73 and 56 to 75 region that was originally defined by cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies Mab13B and Mab24B against HPV16 (48). Candidates 4, 6, and 9 to 11 included L2 epitopes homologous to the aa 17 to 36 and 20 to 38 regions identified in HPV16 with cross-neutralizing monoclonal antibodies RG1 and K18L2 (28, 49) but derived from a variety of other HPV types as detailed in Table 1. Since the intent was to better target a wide range of EV-associated βHPV types, L2-based epitopes of candidates 4 to 11 were designed by bioinformatics-based method to generate consensus sequences derived from multiple cutaneous and mucosal HPV types (Table 1). Following mammalian expression of these candidates in 293 cells, purification by density gradient centrifugation, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we observed VLPs of 50 to 60 nm in diameter only with candidates 4, 6, 7, and 9 to 11 (shown for candidates 9 and 10 in Fig. 1A and B), suggesting that this site is more receptive to the RG1 epitope sequences.

TABLE 1.

Design of L2 peptides inserted into HPV18 L1 for candidate chimeric VLPa

| No. | Amino acid sequence inserted between HPV18 L1 aa 134 and 135 | Epitope design and targeted region of L2 (numbering based on HPV16 sequence) | VLP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GGLGIGTGSGTGGRTGYIPL | HPV16 L2 aa 56–75 | N |

| 2 | GGLGIGTARGSGGRIGYTPL | HPV1 L2 aa 56–75 | N |

| 3 | GGLGIGTGRGSGGSTGYNPI | HPV4 L2 aa 56–75 | N |

| 4 | DIYASCKISNTCPPDVQNKV | Consensus of HPV1/4/38 L2 aa 17–36 | Y |

| 5 | GGLGIGTGRGSGGATGYVPI | Consensus of HPV 1/4/38 L2 aa 55–75 | N |

| 6 | QLYQTCKAAGTCPPDVIPKV | Consensus of 34 HPVsb L2 aa 17–36 | Y |

| 7 | GGLGIGTGSGTGGRTGYVPL | Consensus of 34 HPVsb L2 aa 55–75 | Y |

| 8 | GTGGRTGYVPLGTRPPTVVD | Consensus of 34 HPVsb L2 aa 65–85 | N |

| 9 | QSCKASGTCPPDVINKVEQT | Consensus of 7 cutaneous HPVc L2 aa 17–36 | Y |

| 10 | HIYQSCKASGTCPPDVINKVE | Consensus of 7 cutaneous HPVc L2 aa 14–34 | Y |

| 11 | HIYQSCKASGTCPPDVINKVEQTTI | Consensus of 7 cutaneous HPVc L2 aa 14–38 | Y |

The table summarizes 11 different chimeric VLPs candidates in which an L2-derived peptide sequence is inserted between residues 134/135 of HPV18 major capsid protein L1 within its DE surface loop. For reference, the HPV16 RG1-VLP contains HPV16 L2 17 to 36 (QLYKTCKQAGTCPPDIIPKV) inserted into HPV16 L1. The ability of these candidates no. 1 to 11 to form 50- to 60-nm-diameter VLPs in 293TT cells evident upon density gradient centrifugation and TEM is indicated (Y, yes; N, no) in the last column.

HPV types 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 16, 18, 23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 57, 58, 59, 66, 68, 70, 73, and 76.

HPV types 1, 4, 5, 8, 23, 38, and 76.

FIG 1.

Morphology and immunogenicity of HPV18 L1-L2 chimeric VLP candidates. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of HPV18 candidates 9 (A) and 10 (B) following expression and purification. The VLPs were collected post ultracentrifugation from the interface of the 39% and 33% Optiprep gradient and imaged by TEM. Scale bar, 100 nm. (C) Vaccination of mice with HPV18 L1 chimeric VLP candidates induces L2-specific antibodies. A direct ELISA was performed using a concatenated protein comprising the 17 to 36 epitope equivalent of 22 medically significant HPV types (17 to 36 × 22) to evaluate the L2-specific antibody reactivity generated by the HPV18 chimeric VLP candidates 4, 6, 7, 9, and 10 following vaccination. As the positive control, HPV16 RG1-VLP antiserum was included, and negative controls were wild-type HPV18 L1 VLP and Cervarix antisera. (D) The L1- and L2-specific antibody responses to the three HPV18 L1-derived chimeric VLP candidates shown in panel A were evaluated after immunization of rabbits. For candidate evaluation, NZW rabbits were vaccinated with vaccine candidates 9, 10, and 11, HPV16 RG1-VLP, or Gardasil 9 (3 rabbits per vaccine antigen). Each rabbit was administered three intramuscular vaccinations of 27 μg of VLPs formulated on 50 μg Alhydrogel or 1/10 of Gardasil 9 dose (27 μg), three times each at 2-week intervals. Two weeks thereafter, serum was collected and a direct ELISA was performed using a range of HPV L2 peptides orthologous to the HPV16 L2 17 to 36 aa (RG1) epitope to evaluate the cross-type antibody reactivity generated by the HPV18 chimeric VLP candidates 9, 10, and 11 following vaccination. Gardasil 9 serum was used as a negative control. Titer of sera below the minimum dilution tested is indicated as 0. ELISA was also performed using plates coated with HPV18 L1/L2 VLP.

Vaccination studies were performed after formulation of 2 μg of VLP candidates 4, 6, 7, and 9 to 10 with 50 μg aluminum hydroxide per dose. Groups of five 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice were vaccinated three times with either one dose of candidate VLP or a 1/10 human dose of Gardasil or Cervarix on days 1, 14, and 28. On day 42 post-first vaccination, serum samples were collected for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). All of these candidates, VLP, Gardasil, and Cervarix, elicited HPV18 neutralization titers greater than the maximum tested dilution (6,400), confirming successful vaccination. Hence, we proceeded to assess the antibody responses to the different L2 epitopes by ELISA. Bacterially expressed fusion protein comprising the RG1 epitope ortholog from 22 different HPV types (termed 17 to 36 × 22) (50) was used as the antigen in ELISA. VLP candidates 9 and 10 showed the highest titer among the candidates tested (Fig. 1C). As expected, antisera to candidate 7 and the licensed vaccines were nonreactive because they do not target the RG1 epitope region (Fig. 1C). Candidate 7 was not further pursued, as the 56 to 75 region proved less promising than 17 to 36 in our related chimeric VLP studies (51).

The L2 17 to 36 × 22 ELISA results (Fig. 1C) do not provide information about reactivity to individual HPV types or candidate 11 and are restricted to a single animal model. To better understand the spectrum of cross-reactivity in a second animal model (New Zealand White rabbits), we vaccinated groups of rabbits (n = 3 per group) intramuscularly three times every 2 weeks with 27 μg of VLPs from candidate 9, 10, or 11 or RG1-VLP, each formulated on 50 μg of alhydrogel, or with Gardasil 9 (1/10 human dose containing 27 μg of VLPs and 50 μg element aluminum [Al]). Sera collected 2 weeks after the third dose were tested in ELISA for reactivity to peptides for the orthologous region within the L2 of individual βHPV types. Reactivity of the sample sera to HPV18 L1/L2 VLP was also tested. The results confirmed that broad reactivity across diverse cutaneous and mucosal HPV types was induced by vaccination with constructs 9, 10, or 11 and that the antibody response to HPV18 L1/L2 VLP was as robust as that of Gardasil 9 antisera (Fig. 1D). Since the median titer of serum antibody against the L2 peptides of each HPV type tested was higher for construct 10, and it was also the most immunogenic in mice (Fig. 1C), we elected to pursue it further. Interestingly, however, HPV16 RG1-VLP vaccination also elicited significant responses against the L2 epitopes of all the βHPV peptides tested, although they were consistently lower than those to candidate 10. This suggests that the HPV16 RG1-VLP vaccine itself may provide some degree of cross-protection against βHPVs, consistent with in vitro neutralization activity of rabbit antisera previously seen against HPV5/38/76 when it was formulated with alum and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and administered weeks 0, 4, 6, and 8 (39).

Protective efficacy of Gardasil 9, RG1-VLP, or RG2-VLP vaccines in rabbit challenge model.

Schellenbacher et al. also demonstrated that passive transfer of immune sera from rabbits that were vaccinated with 50 μg of HPV16 RG1-VLP (formulated on aluminum hydroxide and MPL) protected naive mice against vaginal challenge with PsV derived from all HR-HPV (39). However, the protection elicited by RG1-VLP vaccination has not been tested in a disease model or with cutaneous challenge. In addition, it is not clear whether inclusion of MPL with alum adjuvant is necessary to confer broad immunity. To address these questions, we utilized the cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) quasivirus (QV) model, in which papillomas are produced via cutaneous scarification of New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits followed by administration of the CRPV viral genome packaged within L1/L2 capsids of 17 clinically relevant HPVs (52). The number of papillomas that develop from a series of infection sites (usually 10 to 14 sites per rabbit) and their growth rate and size were assessed postchallenge.

To compare the efficacy of the original HPV16-derived RG1-VLP and the new RG2-VLP vaccine with that of Gardasil 9, NZW rabbits (10 per cohort) were administered three intramuscular vaccinations with (i) HPV16 RG1-VLP (80 μg) on 500 μg aluminum hydroxide, (ii) HPV16 RG1-VLP and candidate 10 (40 μg each VLP) on 500 μg aluminum hydroxide, termed “RG2-VLP,” (iii) a human dose of Gardasil 9 (270 μg of VLPs per dose), or (iv) adjuvant only (i.e., 500 μg aluminum hydroxide). Rabbits were vaccinated at months 0, 1, and 2.

Two weeks after the third immunization, and following serum collection, the 10 rabbits in each vaccination cohort were divided into two groups of five. These two groups of five rabbits were infected with two different sets of QV types. Each QV type was inoculated at two separate skin sites on the same rabbit. The first group was challenged with QVs derived from HPV types 6, 16, 31, 35, 39, 45, 52, 58, and 59, whereas the second group received QVs derived from HPV types 6, 11, 18, 26, 51, 56, 66, 68, and 73 (Fig. 2). QV6 was tested twice using two different doses due to past experience with this particular QV causing technical failures. All rabbits were also challenged with wild-type CRPV (Fig. 3), a presumptive negative control for the licensed and test vaccines as the L1 responses are mostly specific to the PV types and the target L2 sequence (QDIYPTCKIAGNCPADIQNKFENKT) (bolded to show region orthologous to RG1 epitope) is divergent from those of HPV.

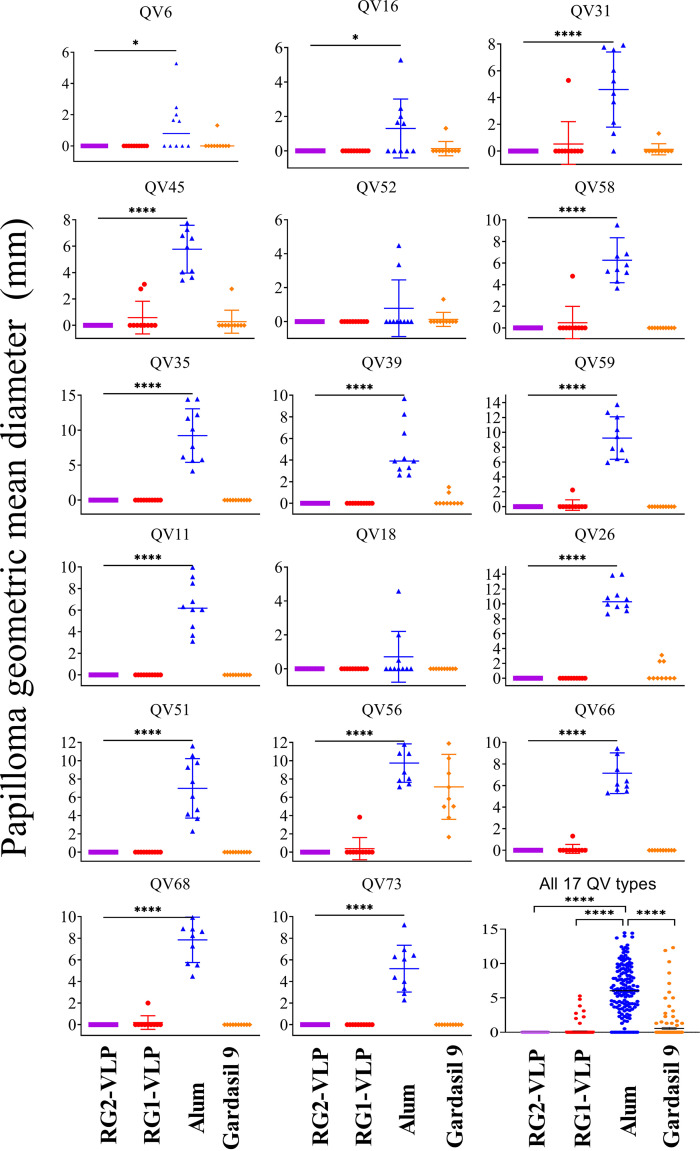

FIG 2.

Papilloma growth in RG1-VLP-, RG2-VLP-, or Gardasil 9-vaccinated rabbits after cutaneous challenge with 17 different HPV QV types and CRPV. Ten rabbits were vaccinated per group at months 0, 1, and 2 with RG1-VLP, RG2-VLP, or Gardasil 9. As a negative control, 10 rabbits were vaccinated with just aluminum hydroxide (Alhydrogel alone; Alum control). Two weeks after the third vaccination, 5 rabbits (batch A) were randomly selected from each treatment/control group (n = 10) for skin challenge with HPV 6, 16, 31, 45, 52, 58, 35, 39, and 59 QV, whereas the remaining 5 rabbits (batch B) were challenged with HPV 11, 18, 26, 51, 56, 66, 68, and 73 QV. In all rabbits, native CRPV (cotton rabbit papillomavirus) was also tested as a negative control for QVs, and this is presented in Fig. 3. Scatterplot shows the size (geometric mean diameter; GMD) for individual papillomas in millimeters at 6 weeks postchallenge, line represents a mean size, and error bars show standard deviation for each HPV QV challenge type, and in summary for all 17 HPV, type QV is presented in the bottom right-most panel. ****, P < 0.0001; *, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

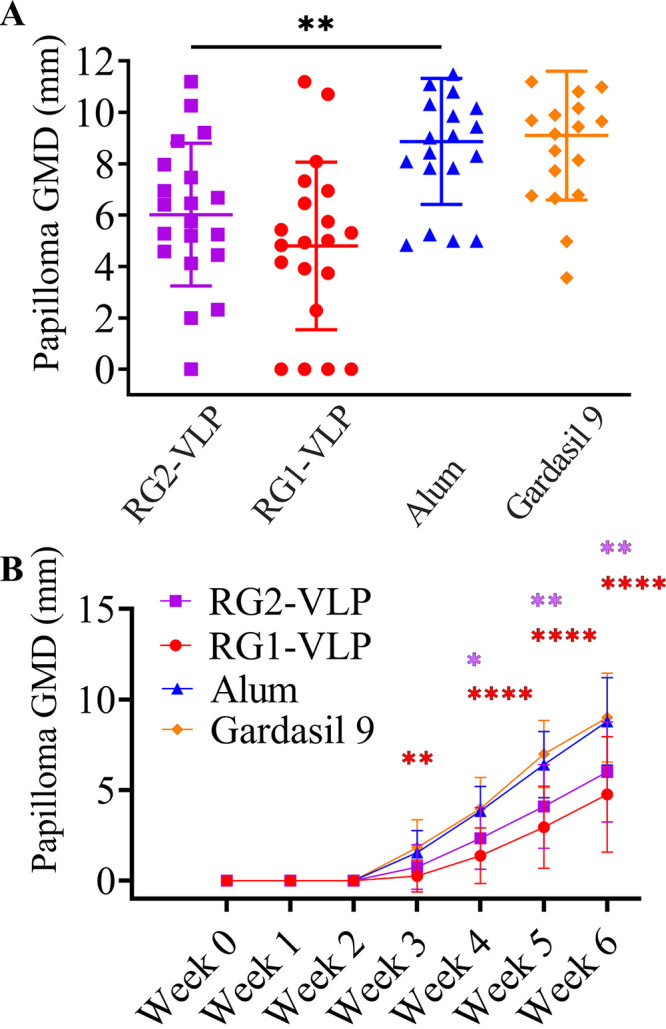

FIG 3.

Growth of papillomas upon cutaneous challenge with native CRPV of rabbits immunized with RG1-VLP, RG2-VLP, or Gardasil 9. (A) In all rabbits in the experiment shown in Fig. 2, native CRPV (cotton rabbit papillomavirus) was also tested as a negative control for QVs. Scatterplot shows the size in three dimensions (using length, width, and height in millimeters to calculate a geometric mean diameter [GMD]) for individual papillomas at 6 weeks postchallenge, the horizontal line represents a mean size, and error bars show standard deviation. (B) Size of papilloma elicited by CRPV challenge was monitored weekly for 6 weeks for the experiment shown in Fig. 2. Line plot shows the average size and standard deviation of GMD of papillomas, and the data are presented longitudinally. P values were calculated by ordinary one-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test. ****, P < 0.0001; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01; *, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

The onset of papillomas was first observed at 3 weeks post-QV challenge, and they were measured for another 3 weeks. The group of rabbits that received only adjuvant (Alum control) showed that every single HPV type infected into the rabbits caused a papilloma minimally at one of the two sites, except HPV18, which failed at many sites. RG2-VLP vaccination fully protected against papilloma caused by all 17 αHPV QVs (Fig. 2) and, remarkably, even provided partial protection against native CRPV virion challenge (Fig. 3). Full protection against most HPV types was also seen in rabbits vaccinated with HPV16 RG1-VLP alone, although only partial protection was observed against HPV31/45/56/58/59/66/68 (Fig. 2). Previously, robust protection was observed against these HPV types under a single type challenge setting in naive mice upon passive transfer with rabbit antiserum generated with the monovalent vaccine formulated in alum + MPL (39). Thus, in a 10-type QV coinfection setting, it is possible that the broad cross-neutralizing antibody response by HPV16 RG1-VLP is overwhelmed or that the addition of MPL adjuvant may be required for full protection against these types.

Unexpectedly, Gardasil 9 vaccination did not confer full protection against HPV6, HPV16, HPV31, HPV45, and HPV52, which are types directly targeted by the vaccine. The partial protection observed may suggest that even the currently approved vaccines can be overwhelmed in a high challenge dose and/or coinfection setting or some breakthrough of nonencapsidated CRPV DNA inoculation (Fig. 2) (53). However, protection against HPV35, HPV51, HPV66, HPV68, and HPV73 was also seen, and limited activity against HPV26, HPV39, and HPV56 was evident. This is unexpected given the type-restricted nature of L1-mediated protection in patient populations with this vaccine and may reflect the high dose (a full human dose in a rabbit) used or species differences in the humoral immune system. The unexpected cross-protection is not likely due to cellular immunity against CRPV L1 because Gardasil 9 vaccination had no impact on CRPV infection or papilloma growth rate (Fig. 3).

Analysis of potential immune correlates of protection.

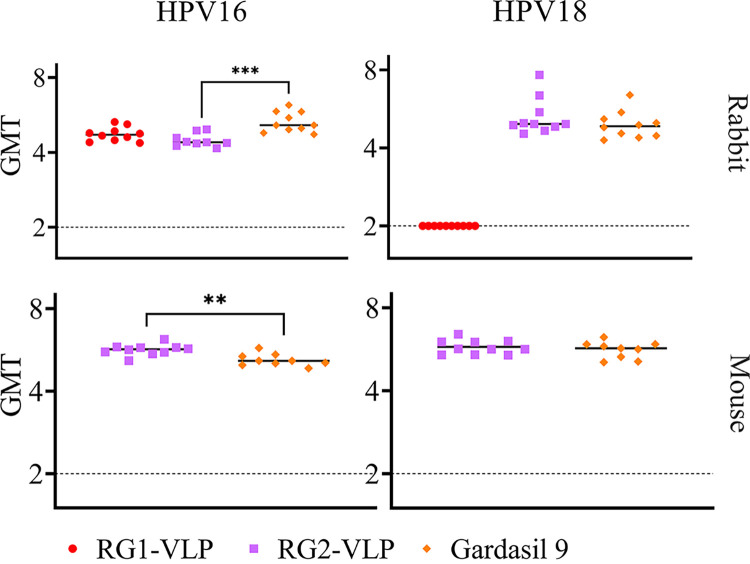

Prior studies utilizing passive transfer of immune sera suggested that protection is conferred by antibodies to conformationally dependent epitopes on L1 or key linear epitopes within L2, including the aa 17 to 36 region. The RG2-VLP vaccine is designed to trigger L1-specific antibodies against HPV16 and HPV18 as well as antibodies to two L2-derived protective epitopes, whereas only the former are induced by Gardasil 9. The mouse and rabbit sera were tested for in vitro neutralization activity against HPV16 and HPV18. Compared to those of the Gardasil 9 antisera, HPV16-neutralizing antibody titers of the RG2-VLP antisera were significantly lower in rabbits; however, they were significantly higher in mice (Fig. 4). The RG2-VLP rabbit and mouse antisera exhibited HPV18-neutralizing titers similar to the neutralizing activity of Gardasil 9 antisera (Fig. 4). For the RG1-VLP immune sera, the HPV16-neutralizing antibody titers were similar to those of Gardasil 9, while the HPV18 titer was below the level of detection (Fig. 4) despite the complete protection against disease caused by this type of QV (Fig. 2). This difference reflects that the cross-protection is mediated via L2-specific antibody cross-reactivity that is measured with poor sensitivity by standard in vitro neutralization assays and opsonization, an important component not detected by the in vitro neutralization assay (29). Rather, the virus-specific protective antibody response is appropriately assessed by ELISA for antibody specific to L1/L2 VLP (Fig. 5). By L1/L2 VLP ELISA, the antibody response to HPV16 and HPV18 elicited by the RG2-VLP vaccine is similar to, or greater than, that elicited by Gardasil 9. For RG1-VLP vaccination, the HPV16 L1/L2 VLP-specific antibody response is consistent with that of Gardasil 9, while the response to HPV18 L1/L2 VLP is evident, although as expected it is significantly lower than that elicited by Gardasil 9 (Fig. 5).

FIG 4.

HPV16 and HPV18 pseudovirus (PsV)-based neutralization assay comparing sera from animals vaccinated three times with Gardasil 9, RG1-VLP, or RG2-VLP formulations. Individual sera from 10 rabbits or 10 mice per group were tested in triplicates. The sera were titrated by 4-fold serial dilutions and incubated with PsV for 2 h at 4°C. The mixture was added to the 293TT cells and incubated at 37°C, at a humidified atmosphere with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 for 72 h. The medium was aspirated, the cells were lysed, and luciferin was added. The luciferase activity was measured by the GloMax multidetection system. The geometric mean neutralization titers (log10 of the dilution that causes 50% of luciferase signal activity) were recorded for each individual serum. A t test was performed to assess for significant differences between the test groups. ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01.

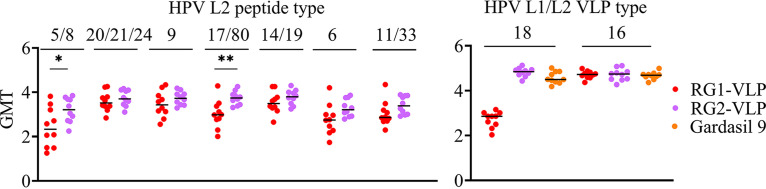

FIG 5.

Analysis of vaccine responses by ELISA using L1/L2 VLP ELISA and RG1 peptides from various HPV types. Sera from 10 rabbits/group vaccinated with HPV16 RG1-VLP, RG2-VLP, or Gardasil 9 were analyzed by direct ELISA using either HPVL1/L2 VLPs (16 and 18) as antigen or 17 to 36 L2 peptide corresponding to various HPV types (5/8, 20/21/24, 9, 17/18, 14/19, 6, 11/33). Scatterplots indicate individual log10 serum titers, while the bars indicate the median values. **, P = 0.001 to 0.01; *, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

Breadth of serologic cross-reactivity of vaccine antisera against L2 of medically significant HPV.

The L2-specific antibody response cross-reactivity was assessed by ELISA to peptides matching the L2 epitope region of each HPV type. Cross-reactivity with the L2 peptide derived from a number of βHPV was evident (Fig. 5) with titers similar to or greater than that for HPV6; notably, both the RG1-VLP and RG2-VLP vaccines protected against this type (Fig. 2). For all 10 of the βHPV types tested, the titer against the unique HPV L2 peptide sequences (n = 7) was higher in the RG2-VLP vaccine antisera than in the RG1-VLP antisera, although the differences reached significance only for HPV5/8 and HPV17/80 (Fig. 5). As expected, there were no significant responses in any of the alum (not shown) or Gardasil 9 antisera.

To further explore the L2-based cross-reactivity of the sera against the numerous medically significant HPV genotypes, we elected to compare responses at a single dilution of rabbit serum nearing the endpoint titer (Table 2). These L2 peptide ELISA revealed that the RG1-VLP and RG2-VLP vaccines consistently elicit serum antibodies reactive with a very broad range of HPV genotypes, including mucosal and cutaneous types and oncogenic and benign types. Importantly, however, the mean reactivity with the L2 peptides of the antisera from the rabbits that received the RG2-VLP vaccine was uniformly higher regardless of HPV type (Table 2). This difference was most significant for cutaneous HPV types, especially βHPV as intended by the design (i.e., a consensus of seven different βHPV L2 aa 14 to 34 sequence was inserted) (Table 1), and also for the genital wart types HPV6 and HPV11. Although better in the RG2-VLP vaccine antisera, reactivity to HPV1, a benign cutaneous type with the most divergent sequence from those used in the two chimeric VLPs, was the weakest.

TABLE 2.

Reactivity to L2 peptides of sera of rabbits vaccinated with either RG1-VLP or RG2-VLPa

| Peptides | Mean ± SD RG1-VLP sera (n = 10) | Mean ± SD RG2-VLP sera (n = 10) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-risk alpha HPV types | |||

| HPV18 | 1.993 ± 0.472 | 2.106 ± 0.411 | 0.576 |

| HPV31 | 0.870 ± 0.837 | 0.929 ± 0.562 | 0.856 |

| HPV35 | 1.098 ± 0.756 | 1.493 ± 0.588 | 0.209 |

| HPV39 | 1.529 ± 0.656 | 1.787 ± 0.543 | 0.352 |

| HPV45 | 1.547 ± 0.606 | 2.010 ± 0.466 | 0.071 |

| HPV51 | 0.868 ± 0.580 | 1.516 ± 0.491 | 0.015 |

| HPV52/58 | 0.948 ± 0.648 | 1.299 ± 0.594 | 0.223 |

| HPV59 | 1.429 ± 0.616 | 1.540 ± 0.572 | 0.680 |

| HPV68 | 2.333 ± 0.356 | 2.512 ± 0.201 | 0.182 |

| HPV56 | 0.557 ± 0.276 | 0.732 ± 0.364 | 0.243 |

| Intermediate-risk alpha HPV types | |||

| HPV26/69 | 2.196 ± 0.484 | 2.448 ± 0.235 | 0.156 |

| HPV34 | 2.044 ± 0.477 | 2.186 ± 0.389 | 0.477 |

| HPV53 | 1.045 ± 0.768 | 1.215 ± 0.630 | 0.595 |

| HPV66 | 0.921 ± 0.534 | 1.032 ± 0.499 | 0.636 |

| HPV67 | 0.986 ± 0.651 | 1.430 ± 0.597 | 0.129 |

| HPV73 | 2.077 ± 0.444 | 2.098 ± 0.572 | 0.929 |

| HPV82 | 1.081 ± 0.727 | 1.597 ± 0.650 | 0.112 |

| Beta HPV types | |||

| HPV5/8* | 1.134 ± 0.936 | 1.806 ± 0.826 | 0.106 |

| HPV20/21/24* | 2.421 ± 0.507 | 2.600 ± 0.299 | 0.348 |

| HPV9* | 2.143 ± 0.768 | 2.638 ± 0.184 | 0.063 |

| HPV17/80* | 1.501 ± 0.916 | 2.653 ± 0.158 | 0.001 |

| HPV14/19* | 2.347 ± 0.556 | 2.614 ± 0.218 | 0.175 |

| HPV92 | 0.753 ± 0.578 | 1.406 ± 0.561 | 0.019 |

| HPV12 | 1.026 ± 0.733 | 1.612 ± 0.679 | 0.081 |

| HPV15 | 1.302 ± 0.776 | 1.946 ± 0.592 | 0.051 |

| HPV75 | 0.856 ± 0.724 | 1.666 ± 0.620 | 0.015 |

| HPV76 | 0.826 ± 0.697 | 1.680 ± 0.570 | 0.008 |

| HPV38 | 0.094 ± 0.073 | 0.787 ± 0.640 | 0.003 |

| HPV23 | 1.746 ± 0.616 | 2.307 ± 0.375 | 0.024 |

| HPV37 | 1.352 ± 0.754 | 2.157 ± 0.461 | 0.01 |

| HPV22 | 1.739 ± 0.663 | 2.354 ± 0.413 | 0.023 |

| HPV36 | 1.331 ± 0.715 | 1.970 ± 0.578 | 0.041 |

| Benign alpha types | |||

| HPV44 | 0.893 ± 0.901 | 0.950 ± 0.602 | 0.871 |

| HPV32 | 1.160 ± 0.784 | 1.811 ± 0.685 | 0.064 |

| HPV13 | 1.067 ± 0.747 | 1.616 ± 0.724 | 0.113 |

| HPV6 | 1.094 ± 0.943 | 1.936 ± 0.651 | 0.039 |

| HPV11 | 1.339 ± 0.885 | 2.176 ± 0.571 | 0.022 |

| Benign skin wart types | |||

| HPV1 | 0.110 ± 0.099 | 0.508 ± 0.671 | 0.08 |

| HPV2 | 2.133 ± 0.478 | 2.280 ± 0.367 | 0.452 |

| HPV3 | 1.093 ± 0.747 | 1.527 ± 0.663 | 0.186 |

| HPV7 | 0.775 ± 0.512 | 1.780 ± 0.549 | 0.0005 |

| HPV10 | 1.313 ± 0.660 | 1.711 ± 0.558 | 0.163 |

| HPV57 | 2.383 ± 0.314 | 2.474 ± 0.224 | 0.464 |

ELISA reactivity of rabbit antiserum with HPV16 L2 aa 17 to 36 (RG1) epitope-corresponding region of L2 of diverse medically significant HPV after background subtraction. Sera were derived from the animals described in Fig. 2 at month 2.5, prechallenge, and tested at 1:1,000 dilution, except where indicated by * with optical density (OD) values obtained at 1:900 dilution. SD, standard deviation.

Bold P values indicate significance.

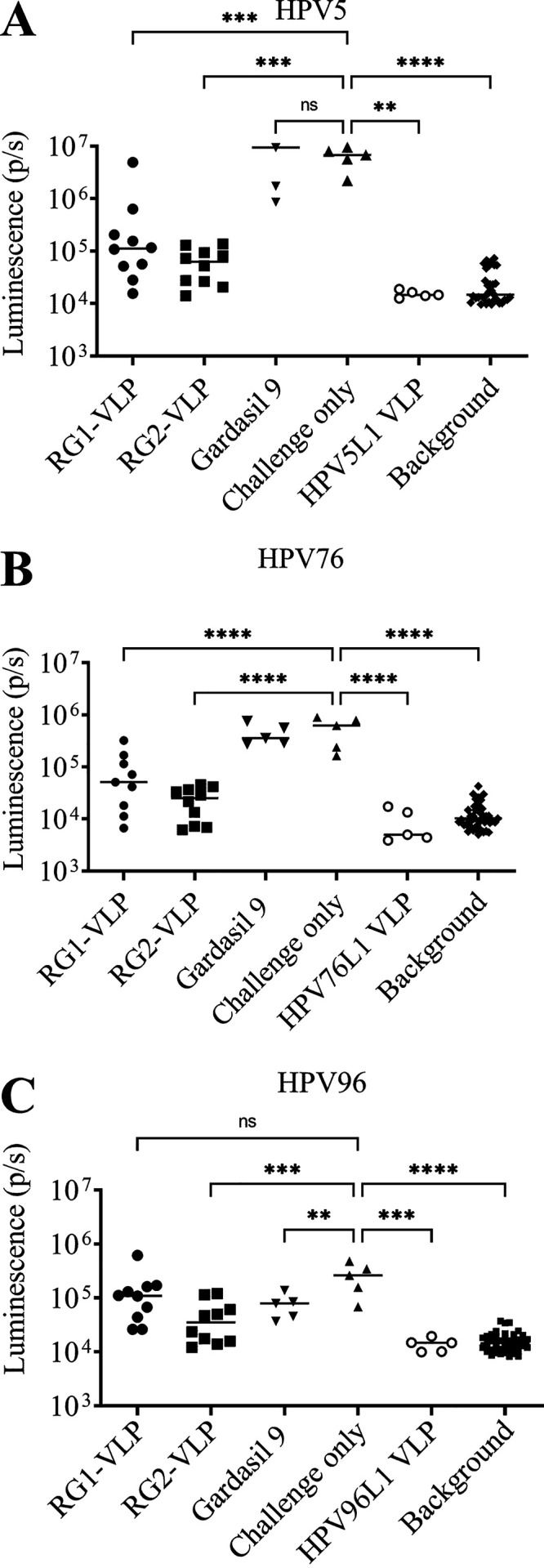

Efficacy of passive transfer of vaccine antisera for protection against challenge with select βHPV.

To address whether the serum antibodies detected with the βHPV L2 peptide ELISA could confer protection, we performed passive transfer of 50 μL for each individual rabbit antiserum into a naive mouse 1 day prior to challenge intravaginally with a single βHPV pseudovirus delivering a luciferase reporter. This corresponds to an ~1:25 dilution assuming a 1.34 mL plasma volume per 20 g mouse (54). IVIS imaging of luciferase-based bioluminescence on day 3 postchallenge was used to visualize and quantify infectivity. Our initial challenge study tested protection against the prototypic β-type HPV5.

The passive transfer studies suggested that the RG1-VLP antisera even diluted 1:25 could provide significant protection against HPV5 PsV challenge, although again the mean level of protection was greater with the RG2-VLP antiserum. The HPV5 L1 VLP antiserum (generated with four immunizations and using Freund’s adjuvant) was the most protective, whereas Gardasil 9 antisera (3 doses) failed to provide significant protection. Similar results were obtained with β-types HPV76 and HPV96, further supporting (i) the type-restricted nature of Gardasil 9, (ii) the agreement between the L2 peptide ELISA reactivity and protective efficacy, and (iii) the superior activity of the RG2-VLP vaccine over that of RG1-VLP against βHPV (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Assessment of protective immunity in sera of vaccinated rabbits via passive immune transfer. Protection via passive transfer of sera from rabbits vaccinated with Gardasil 9, RG1-VLP, or RG2-VLP was assessed in CD-1 ISG mice (10 per group) followed by vaginal challenge with βHPV PsVs derived from types (A) 5, (B) 76, and (C) 96. Fifty microliters of sera from individual rabbits was passively transferred into each mouse by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection followed by challenge with PsV on the following day. The bioluminescence images were acquired 72 h postchallenge for 5 min with a Xenogen IVIS 100 and quantified in the region of interest (photons per second) or an irrelevant region of the same size to determine background. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01; *, P = 0.01 to 0.05; not significant (ns), P ≥ 0.05.

Cross-protection against skin cancer-relevant HPV5 PsV in an EV mouse model.

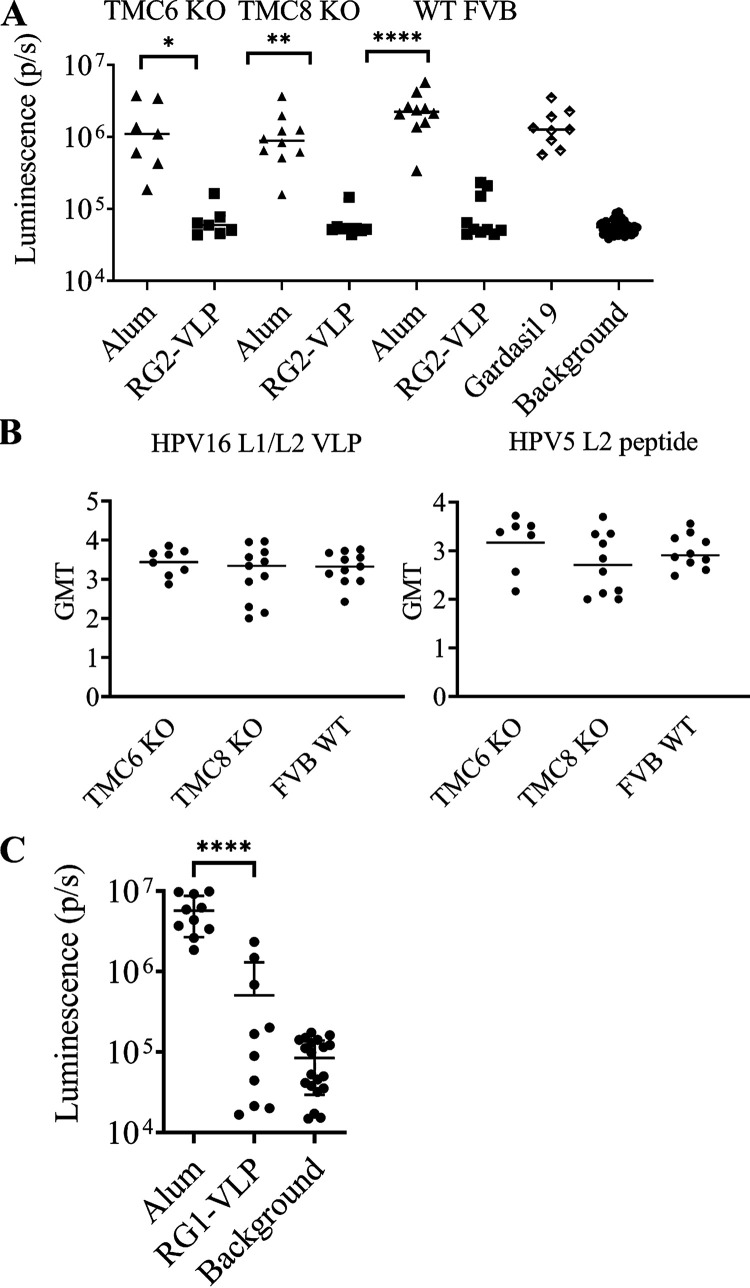

HPV5 is the prototypic EV- and skin cancer-relevant HPV type. We assessed in another animal model, FVB mice, whether active immunization with RG2-VLP (4 μg of each chimeric VLP type formulated on 50 μg of aluminum hydroxide), adjuvant alone, or Gardasil 9 (1/20 of a human dose) three times protects against challenge with HPV5 pseudovirus (PsV) delivering a luciferase reporter. In addition, Tmc6Δ/Δ or Tmc8Δ/Δ FVB mice, as models of inherited EV disease in humans, were concurrently immunized with RG2-VLP (Fig. 7A). There was no significant difference in the serum antibody titers against HPV5 L2 peptide or HPV16 L1/L2 VLP between wild-type, Tmc6Δ/Δ, or Tmc8Δ/Δ FVB mice at 2 weeks postvaccination (Fig. 7B). Two weeks after completing vaccination, the mice were challenged intravaginally with HPV5 PsV. RG2-VLP vaccination robustly protected against HPV5 infection in wild-type FVB mice, as well as both models of inherited EV. Gardasil 9 vaccination had no impact on HPV5 infection in wild-type FVB mice (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

RG1-VLP- and RG2-VLP-induced protection against HPV5 PsV challenge in wild-type and EV model mice. (A) Female FVB mice (wild type, Tmc6Δ/Δ, or Tmc8Δ/Δ) were immunized with the RG2-VLP vaccine (4 μg of each chimeric VLP type formulated on 50 μg of aluminum hydroxide), adjuvant alone, or Gardasil 9 (1/20 of a human dose, wild-type FVB mice only) three times at 1-month intervals. Two weeks after the final immunization, serum was harvested. A direct ELISA was performed using plates coated with HPV16 L1/L2 VLP or HPV5 epitope comprising L2 fragment orthologous to HPV16 RG1 to evaluate reactivity, and the geometric mean titer (GMT) of each serum is shown. (B) Two weeks after the final immunization, the mice in panel A were challenged intravaginally with HPV5 PsV. (C) Monovalent RG1-VLP vaccination was performed in wild-type female FVB mice on the schedule in panel A, and the animals were challenged as described for panel B with HPV5 PsV. ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P = 0.0001 to 0.001; **, P = 0.001 to 0.01; *, P = 0.01 to 0.05.

The strong HPV5 L2-specific antibody response observed in rabbits that received RG1-VLP suggests that it alone may be sufficient for protection. To test this, we vaccinated wild-type FVB mice (10 male and 10 female) with 25 μg RG1-VLP on 50 μg aluminum hydroxide or adjuvant alone three times at 2-week intervals. There was no significant difference in the antibody titers in male and female mice when comparing HPV16 L1/L2 VLP ELISA (P = 0.76), ELISA against L2 17 to 36 of HPV16 (not shown), or the corresponding epitope in HPV5 (P = 0.08). Upon vaginal challenge of the 10 female mice with HPV5 pseudovirus, robust protection was evident in mice vaccinated with HPV16 RG1-VLP (Fig. 7C), similar to that with the RG2-VLP vaccine (Fig. 7A).

DISCUSSION

We sought to generate a prophylactic vaccine effective against both oncogenic αHPV and βHPV potentially associated with CSCC in EV and immunocompromised patients. We found that prophylactic vaccination with a combination of HPV16-derived RG1-VLP and candidate 10 formulated on alum (i.e., RG2-VLP) can confer robust protection in rabbits against papilloma formation elicited by experimental challenge with all αHPV QV tested. The protection overall was more robust than that for RG1-VLP vaccination (Fig. 2). However, RG1-VLP vaccination was protective against diverse αHPV (as well as HPV5), and this differential in protection compared to that of the RG2-VLP might be narrowed by using an adjuvant more potent than alum (55–57). A limitation of the study is the presence of DNA inside the HPV18 chimeric VLP, although this did not appear to profoundly enhance the neutralizing responses over those seen for Gardasil 9 or RG1-VLP produced in insect cells for cGMP from which DNA was removed by a disassembly/Benzonase treatment/reassembly approach (55–57).

RG2-VLP extended protection beyond the 9 αHPV types targeted by Gardasil 9. Gardasil 9 does not target the βHPV and indeed did not protect against HPV5 PsV challenge in the mouse model. In contrast, both the RG1-VLP and RG2-VLP immunizations strongly protected FVB mice against HPV5 challenge. This correlated with induction of a robust serum antibody response against the L2 epitope of HPV5, and there was no evidence of immunologic interference when combining the two VLP. These L2-specific antibodies recognized this region in diverse βHPV, suggesting potential for broad protection at either mucosal or cutaneous sites against diverse βHPV as seen in the αHPV challenge studies in mice and rabbits, respectively. Importantly, RG2-VLP immunization also protected Tmc6Δ/Δ and Tmc8Δ/Δ FVB mice from HPV5 PsV challenge and induced an immune response similar to that of wild-type mice (Fig. 7A and B). This finding suggests that patients with inherited EV, whose response to other pathogens and vaccines appears intact, could benefit in particular from this vaccine to prevent βHPV-related disease and CSCC. In the case of acquired EV, it is not clear whether these immunosuppressed patients could respond to vaccination with RG2-VLPs. However, both HIV+ patients and OTR do respond to the licensed HPV vaccines, suggesting that this is possible, although seroconversion has been reported to not be 100% compared to that of healthy adults and the titers are lower. Hence, vaccination is probably better performed prior to immune suppression (58).

The HPV16 RG1 epitope is well conserved across HPVs, although there are subtle differences between αHPV and βHPV that suggest a second chimeric VLP is valuable to breadth of immunity. The two cysteine residues within the RG1 epitope are completely conserved. Mutagenesis of either cysteine or both to serine (C22S/C28S) renders HPV16 PsV noninfectious but produces no apparent defects in cell binding, endocytosis, or trafficking to lysosomes by 8 h postinfection, although mutant L2/genome complexes failed to exit the endo/lysosomal compartment (59). Likewise, C22A, C28A, or K20A mutation eliminated binding by monoclonal antibody RG1, and P29A weakened binding, suggesting that its epitope is centered on these residues. Similar findings were shown with monoclonal antibodies WW1 (29), 14H6 (60), K4L220–38, and K18L220–38 (49). A C22-C28 disulfide bridge is likely present in native virions (59, 61), although RG1 binds similarly to the reduced or bonded peptide (62). These observations suggest a critical role for the RG1 epitope region and its two cysteines in viral infectivity, accounting for its high degree of sequence conservation and implying that the evolution of RG2-VLP escape mutants and type replacement are unlikely.

Interestingly, the RG1 region is poorly accessible to the immune system such that infection typically fails to induce antibodies against this broadly protective region (36). Indeed, this region is buried below the capsid surface until virus binding to the basement membrane (19, 30), whereupon the exposed N terminus is cleaved extracellularly by furin to enable a productive engagement with basal keratinocytes to initiate infection (63). While this several-hours-long process provides ample time for engagement with L2-specific antibody (and thereby phagocytes) to block infection, it is poorly replicated by conventional in vitro HPV PsV neutralization assays based on 293 cells (64). Passive transfer is the more physiologic measurement of protective antibody levels, but it is low-throughput and complex to execute. Assay of epitope-specific antibody by ELISA is a more robust, high-throughput, and practical immune correlate of L2-mediated protection. Indeed, for the L1 VLP-antibody-based immunity, the use of L1/L2 VLP ELISA has proven to be a relevant immune correlate similar to in vitro neutralization titers (65). Consequently, binding-based assays, such as Merck’s multiplex competitive Luminex inhibition assay (cLIA), have been used in bridging studies between age groups and dose cohorts and to support approvals for the now-licensed L1-only VLP vaccines. Future efforts to develop a robust binding assay for L2 that correlates with protection should be considered.

Remarkably, a single dose of the licensed L1 VLP vaccines appears to provide long-term type-specific immunity associated with very low titer antibody responses such that a minimal titer for protection has yet to be defined (66, 67). Passive transfer studies also support that even very low antibody levels provide robust protection (68). RG2-VLP elicits titers of HPV16- and HPV18-specific antibodies similar to those of Gardasil 9 driven by responses to L1, but the antibody titers to the L2 RG1 epitopes are 2 orders of magnitude lower, in part reflecting the much smaller size of the antigen. Our study shows robust protection over 6 weeks. This raises questions about the durability of L2 responses, but previous studies utilizing RG1-VLP have demonstrated detectable HPV16 L2 17 to 36 epitope-specific serum antibody titers and long-term protection (>13 months) utilizing the same model (39, 69). Nonetheless, whether a sufficient response can be triggered by a single dose of RG2-VLP remains to be determined. To this end, titers might be boosted and dosing requirements might be reduced by better adjuvants and formulations, along with improvements in product stability at ambient temperatures to facilitate vaccine program implementation (55–57).

Since the licensed vaccines do not protect against all 24 αHPV that have carcinogenic potential, the need and cost of cervical screening remain in vaccinated women, albeit with greatly diminished cost-benefit and effectiveness because of the substantially lower disease prevalence. This dilemma could be mitigated by improving the accuracy of cytologic screening by addition of (self-) HPV testing and/or reduced screening schedules (70), or even more highly multivalent vaccines. However, these solutions are challenging for developing nations whose health care systems lack the infrastructure or resources to efficiently carry out these new forms of screening interventions or to introduce a more complex and thus costly vaccine. Hence, the development of a simple vaccine formulation targeting all carcinogenic HPV by using a conserved protective antigen is an attractive alternative, although near complete protection against HPV16 and -18 remains paramount.

Evolution of escape mutants is unlikely, as HPV genomes are very stable, but HPV type replacement is a controversial possibility (71–73) that would theoretically be mitigated with a broadly effective vaccine targeting an evolutionarily conserved protective epitope.

Demonstration of viral causation of a human cancer is challenging, requiring laboratory-based, clinical, and epidemiologic evidence and ultimately its prevention through vaccination (22, 42). While there is a body of compelling laboratory studies supporting the foundational clinical observations in inherited EV patients (44), epidemiologic studies of βHPV’s role in the development of CSCC have been less informative and greatly complicated by a potential hit-and-run mechanism, transmission throughout the lifetime, and their ubiquity. The ability to vaccinate against βHPV provides an opportunity to definitively establish or refute its etiologic role in CSCC (42).

In the case of αHPV, whose transmission is generally mediated via sexual contact, it is evident that vaccination just prior to sexual debut is optimal. However, RG2-VLP has potential to protect against cutaneous infections, including benign types typically acquired earlier in childhood and βHPV infections across the life span. Thus, it may be most beneficial to introduce RG2-VLP vaccination at a young age. Immune suppression in organ transplant recipients releases cutaneous viruses from immune control, and their profoundly enhanced replication appears to contribute to their high rates of CSCC in UV-exposed areas. HPV L1-specific antibodies persist even after this immunosuppression (74), suggesting that RG2-VLP administration prior to transplant could control this burst of replication. Transplant patients do respond to vaccination with licensed HPV vaccines, albeit with reduced titers (58), but this has not been tested with RG2-VLP.

We did not find evidence that Gardasil 9 vaccination generates a significant protective antibody response against βHPV or affects the growth of CRPV-induced papilloma. Given the conservation of internal L1 sequences, it is possible that Gardasil 9 triggers cross-reactive cellular immune responses that could control βHPV that might not be evident in our studies. However, its inability to affect disease development or growth in the cutaneous CRPV challenge model suggests that this is unlikely. As expected, RG2-VLP vaccination also failed to fully prevent CRPV-induced papilloma, although some modest protection was observed (Fig. 3A), given its divergent sequence even in L2.

The incidence of CSCC has increased in the last 3 decades, and it is more common in areas of high sun exposure and in fair-skinned individuals (75). In the United States, the total number of CSCC cases far exceeds the number of all other cancers combined (76), and the number of people who die each year from CSCC (77, 78) is similar to that from cervical cancer. In geographic areas with high exposure to UV radiation, deaths from CSCC may approach those from melanoma (76). The age-adjusted incidence among White people is estimated at 100 to 150 per 100,000 persons per year (77), and organ transplant recipients are 100-fold as likely to develop keratinocytic skin cancer as age-matched control subjects, with lesions appearing an average of 2 to 4 years after the transplantation and increasing in frequency over time (78, 79). Patients with HIV also have an increased risk, and antiretroviral therapy had little effect on rates (80, 81). While ~95% of CSCC cases are detected early enough to be curable with standard excision, Mohs micrographic surgery, curettage, etc., 5% advance or are metastatic and require radiation and chemotherapy (82). Monoclonal antibody Cemiplimab, targeting PD-1, is the only treatment specifically approved for metastatic CSCC (83). For metastatic CSCC patients, only 7% achieve a complete response. Cemiplimab treatment is costly, has significant side effects, and cannot be used in some transplant patients (84). Prevention of CSCC is a preferable alternative. Importantly, there is intriguing evidence for cutaneous βHPV infection as a cocarcinogen for CSCC in aging immunocompetent individuals and high-risk cohorts (42), and, if true, vaccination to prevent these infections, in addition to sunscreen/avoidance, has potential to greatly diminish the associated morbidity and mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal studies and ethics statement.

Mouse studies were performed following the guidelines and institutional policies with the approval of Johns Hopkins Animal Care and Use Committee. Rabbit studies were performed following the guidelines and institutional policies with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Pennsylvania State University’s College of Medicine (COM), and all procedures were performed in accordance with the required guidelines and regulations.

Murine models.

Inbred BALB/c and CD-1 ISG outbred 6- to 8-week-old mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. The wild-type control, 6- to 8-week-old FVB/NTac female mice, were obtained from Taconic Biosciences, and Tmc6Δ/Δ and Tmc8Δ/Δ knockout mice were obtained from Andrew J. Griffith (85) and cross-bred onto the FVB/NTac background.

Mouse vaccination.

For selection of a suitable HPV18 L1 chimeric VLP candidate, 2 μg of each candidate was formulated with 50 μg aluminum hydroxide (Alhydrogel; Invivogen). Next, groups of female BALB/c mice (5 per group) were each vaccinated either with one of candidates 4, 6, 7, 9, or 10 or with a 1/10 human dose of Gardasil or Cervarix on days 1, 14, and 28 or days 1 and 28. For RG2-VLP evaluation, 4 μg of each of the 2 VLP types, HPV16 RG1-VLP (Paragon Bioservices) and candidate 10 VLP, was coformulated with 50 μg alum or 1/20 (i.e., 25 μL) of a human dose of Gardasil. Groups of female FVB WT or Tmc6Δ/Δ and Tmc8Δ/Δ mice were immunized by intramuscular injection (i.m.) with 3 vaccination doses in 1-month intervals. All mice were bled 2 weeks after the final vaccination (i.e., day 42) to obtain sera for immunogenicity testing.

Rabbit vaccination and challenge study.

New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits were purchased from Robinson Inc. For evaluation of RG2-VLP compared to HPV16 RG1-VLP and Gardasil 9, NZW rabbits (both males and females of 2 to 3 months old, n = 10 per vaccine group) were administered three intramuscular vaccinations of (i) HPV16 RG1-VLP (80 μg, a human equivalent dose), (ii) RG2-VLP (HPV16 RG1-VLP and candidate 10 at 40 μg each to make 80 μg), (iii) a full human dose of Gardasil 9 (270 μg of VLPs per dose), coformulated with 500 μg aluminum hydroxide (Alhdyrogel; Invivogen), or (iv) aluminum hydroxide only as control. Rabbits were immunized at months 0, 1, and 2. Two weeks following final vaccination, each group of 10 rabbits was divided into two groups (5 per group). In the first group, in vivo protection was assessed concurrently against infection of QVs of HPV types 6 (low dose), 16, 31, 45, 52, 58, 35, 39, and 59, each at two distinct and marked skin sites. In the second group, in vivo protection was assessed against coinfection of QVs of HPV types 6 (high dose), 11, 18, 26, 51, 56, 66, 68, and 73, each at two distinct skin sites. In all rabbits and groups, two distinct skin sites were coinfected with wild-type CRPV as a negative control for HPV types. Rabbits were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). After the animals’ backs were shaved, 0.5-cm-diameter skin sites were scarified with a scalpel. Three days after scarification, the rabbits were again anesthetized, and a 5 to 10 μL suspension of HPV capsid/CRPV genome QV or 50 μL of CRPV virion stock (control) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; standardized by genome content for all capsid types) was applied to the prescarified site using the edge of a syringe needle. Each HPV type was challenged at two different sites in each rabbit. Subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) were administered as analgesics postscarification and postinfection, as needed. The sizes and frequencies of lesions were evaluated at up to 6 weeks postchallenge. Tumor size was recorded as a three-dimensional measurement (length by width by height) for each lesion and calculated using geometric mean diameter (GMD) in millimeters as described previously (86). In the absence of a lesion, a diameter of zero was assigned. In a given treatment group, full protection was defined as the absence of papillomas in all animals, and partial protection was defined as the presence of any breakout papillomas measured on the rabbits.

Passive transfer and mouse vaginal PsV challenge.

In all challenge groups, mice were injected with 3 mg of medroxyprogesterone (Depo-Provera, Pfizer, New York, NY) to synchronize their estrous cycles, 4 days before vaginal challenge. Passive transfer of animal sera was performed a day prior to a vaginal challenge. For initial candidate evaluation, 8- to 10-week-old female BALB/c (Charles Rivers Laboratories) were passively transferred with 100 μL of pooled rabbit sera by the intraperitoneal route. For the comparison of RG1-VLP- to RG2-VLP-induced humoral immunity, 16 to 18 g female CD-1 IGS mice (Charles River Laboratories) were passively transferred with 50 μL of individual rabbit sera. On the following day, approximately 24 h post passive transfer, and 4 days post medroxyprogesterone treatment, the mice were challenged intravaginally with HPV pseudovirions (PsV) containing luciferase reporter. The amount of PsV used varied by the HPV types used and has been titrated to the signal to noise ratio of >10. The challenge dose ranged from 5 to 20 μL of PsV, mixed with 20 μL of 3% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC). To execute the virus challenge, HPV PsVs were directly instilled into the mouse’s vaginal vault, before and after cytobrush treatment (15 to 20 rotations, alternating directions), while the mice were under ketamine hydrochloride (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) anesthesia. The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane 72 h after challenge, and 20 μL of luciferin substrate (7.8 mg/mL, Promega, Madison, WI) was then delivered into the vaginal vault before imaging. Bioluminescence was acquired for 5 min with a Xenogen IVIS 100 (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) imager, and analysis was accomplished with Living Image 2.0 software. Luminescence data were expressed as a ratio of the radiance signal (in photons [p] per second per square centimeter) in the vaginal region to the radiance signal in the thoracic region. The analysis was performed using Living Image 2.5 software (Perkin Elmer), and luminescence was quantified in photons in regions of interest.

Vaccine design and preparation.

The HPV16 RG1-VLP vaccine sequence was designed and produced by Paragon (lot PB16076) using baculovirus and disassembly/Benzonase/reassembly to remove encapsidated DNA as previously described in reference 69. The 11 HPV18 chimeric VLP candidates were each directly synthesized and separately cloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1(+). Next, a small-scale expression analysis was then performed for each candidate construct utilizing the Expi293 expression system per the manufacturer’s protocols. Following expression, cell lysates were harvested and the respective lysates were placed in 37°C for 16 h in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline with calcium and magnesium supplemented with 9.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25% Brij58, and 0.1% Benzonase. Thereafter, the NaCl concentration of the lysates was adjusted to 0.8 M, loaded onto a 27%/33%/39% OptiPrep step gradient, and separated by ultracentrifugation for 16 h at 40,000 × g in an SW40 rotor. Fractions were collected from the interface between the 39% and 33% Optiprep, as this is the region where properly assembled VLP collect. The fractions were then assessed for purity via Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gel and for VLP assembly via transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and DNA content was analyzed by extraction using quick-DNA miniprep plus kit (Zymo research) and concentration measurement using a Qubit high sensitivity dsDNA quantification kit (ThermoFisher). The candidate 10 preparation contained 140 ng DNA/40 μg antigen (suggesting only ~2% full particles), implying that HPV18 L1 is less prone to encapsidate DNA in the absence of L2 and HPV16 L1.

Pseudovirus preparation.

Pseudovirions were prepared in 293TT cells cotransfected with HPV L1/L2 expression plasmids and a firefly luciferase expressing plasmid as a reporter for monitoring PsV infection. On the day of transfection, plasmid DNA was incubated with Mirus transfection reagent (TransIT-2020, catalog no. MIR5406) in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium (Gibco, catalog no. 31985-070). The transfection cocktail was added to the cells and incubated at 37°C, humidified atmosphere 5%, CO2 for 44 to 48 h. The cells were then harvested by trypsinization (0.25% Trypsin, Gibco, catalog no. 14190-136) and pelleted. The cell pellets were lysed in an equal volume of lysis buffer (PBS-Mg supplemented with 0.5% of Brij 58 and 0.2% Benzonase nuclease) for 24 h and incubated at 37°C in siliconized tubes. The PsV was then salt extracted by adding 5 M NaCl to a final concentration of 850 mM NaCl and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatants containing PsVs were then transferred into new siliconized tubes and stored at −80°C. When needed, the PsVs were purified using gradient density purification with Optiprep density gradient medium, as for the VLPs.

Quasivirus production.

QV were produced as described previously (52). Briefly, 293TT producer cells were cotransfected with recircularized CRPV genomic DNA and HPV L1/L2 double expression plasmids. Two days posttransfection, the cells were lysed with Brij-58, incubated to allow particle maturation, and treated with Benzonase (Sigma, MO) and Plasmid Safe (Epicenter, WI) to digest unprotected DNA. Cell lysates were separated on OptiPrep step-density gradient (27/33/39%) upon centrifugation overnight at 40,000 rpm in SW40 rotor (Backman, CA). Fractions with appropriate densities and positive for capsid proteins were assayed for their infectivity and in vitro neutralization with specific antibodies in RK13 cells by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) measuring viral E1^E4 transcripts.

Plasmids.

The plasmid vectors expressing codon-optimized L1 and L2 capsid genes of various HPV types were generated previously by our groups (available via Addgene) or kindly provided by John Schiller, NCI, Bethesda, USA or Joakim Dillner, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden. For plasmid vectors containing the 11 candidate HPV18 L1, sequences were synthesized by Genscript and cloned into a mammalian expression vector pcDNA 3.1(+) (Thermofisher Scientific).

Pseudovirus-based neutralization assays.

The HPV PsV in vitro neutralization assays were performed as described before (87). In short, sera from vaccinated mice were titrated on the 96-well plates by serial dilution. The HPV PsV were then added to the sera and incubated for 2 h. Thereafter, the mixture of sera and the virus was added to the 293TT cells and incubated at 37°C, at a humidified atmosphere with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 for 72 h. Upon 72 h of incubation, the medium was aspirated and the cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (Promega E1531). Luciferin was added and the luciferase activity was measured by the GloMax multidetection system (Promega, E8032). The neutralization titers (IC50) were recorded for each individual serum. The t test was performed to assess for statistical difference between the tested groups.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

For the 17 to 36 ×22 ELISA, 500 ng in 100 μL PBS/well concatenated protein was coated on Nunc MaxiSorp microtiter 96-well plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham MA) and incubated overnight at 4°C. This protein contains the amino acid residue positions 17 to 36 region of L2 from 22 different HPV types (56). Peptides of 21 amino acid sequences of RG1 epitopes of each HPV type were synthesized with an N-terminal biotin by Genscript. For individual biotinylated L2 peptide ELISA, the 96-well plates (Thermo Scientific, 15126) were coated with neutravidin (Thermo Scientific, catalog no. 31000) overnight. Neutravidin-coated plates were then incubated with biotinylated peptides (25 ng/well) at 4°C overnight. The next day after coating, plates were blocked with PBS/1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at 37°C. For the 17 to 36 ×22 ELISA, each of the serum samples was then diluted 1:50 in PBS/1% BSA and was then added to the 96-well plates for 1 h at 37°C. For biotinylated peptides, the sera were either serially diluted 3-fold, 8 times beginning at 1:50 to 1:200 or screened at 1:1,000 dilution. Following this, plates underwent 3 washes with washing buffer (0.01% [vol/vol] Tween 20 in PBS) before HRP-labeled sheep anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG diluted 1:5,000 in 1% BSA was added to each well, and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. After 3 further washes, 100 μL of 50 mg/mL 2,2′-Azinobis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) was added to each well for development, and absorbance at 405 nm was measured using a benchmark plus microplate reader (Bio Rad, Hercules CA) after 30 min at room temperature (RT).

Cell culture and cell lines.

293TT cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco minimum essential medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, no. 11965-084) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini, catalog no. 900-108, 50 mL), 1× penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, catalog no. 10378-016), 1× nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen, catalog no. 11140-050), 1× l-glutamine (Invitrogen, catalog no. 25030-081), and 1× sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen, catalog no. 11360-070). EXPI293F suspension cells were grown in Expi293 expression medium (Gibco, catalog no. A1435101) using ExpiFectamine and transfected using the EXPI293F transfection kit (Gibco, catalog no. A14635).

Transmission electron microscopy.

To assess particle assembly and size, the samples collected in Optiprep (8 μL) were adsorbed to glow-discharged (EMS GloQube) ultrathin (UL) carbon-coated 400-mesh copper grids (EMS CF400-Cu-UL) by flotation for 2 min. Grids were rinsed in 3 drops (1 min each) of Tris-buffered saline (TBS), negatively stained in 2 consecutive drops of 0.75% uranyl formate (UF, aq.), and quickly aspirated. Grids were imaged on a Hitachi 7600 TEM operating at 80 kV with an AMT XR80 CCD (8 megapixels).

Statistics.

To calculate the EC50 value (the reciprocal of the dilution that causes 50% reduction in luciferase activity), the nonlinear model y = bottom + (top − bottom)/{1 + 10^[(LogEC50 − x) × HillSlope]} was fitted to the log10-transformed neutralization titer triplicate data using GraphPad Prism 8. Statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism 8 software using ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison test unless stated otherwise. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The asterisks in figures indicate statistical difference between the indicated groups: ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P = 0.0001 ≤ 0.001; **, P = 0.001 ≤ 0.01; *, P = 0.01 ≤ 0.05; not significant (ns), P ≥ 0.05.

Data availability.

The data supporting the finding of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under awards P30CA06973, P50CA098252, R01CA233486, and R01CA237067. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The work related to finally selecting candidate 10 for the RG2-VLP formulation was sponsored by PathoVax LLC as part of a service agreement with the Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD. Evaluation of the RG2-VLP vaccine formulation in rabbit challenge studies was sponsored by PathoVax LLC via the National Institute of Health SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) program R44AI136236 as part of a service agreement with the Department of Pathology, Penn State Hershey Medical Center, College of Medicine, Hershey, PA.

Under license agreements between PathoVax LLC and Johns Hopkins University, Roden and Kirnbauer are entitled to distributions of payments associated with an invention described in this publication. Roden and Kirnbauer also own equity in PathoVax LLC and are members of its scientific advisory board. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

P.O., R.R., and J.W.W. wrote the manuscript, P.O., K.M., M.W., J.A., P.L., N.C., and B.H. performed experiments and analyzed data, and J.H., R.K., J.W.W., and R.R. oversaw the experiments.

Contributor Information

Richard B. S. Roden, Email: roden@jhmi.edu.

Lawrence Banks, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, Zur Hausen H. 2004. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 324:17–27. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karatayli-Ozgursoy S, Bishop JA, Hillel A, Akst L, Best SR. 2016. Risk factors for dysplasia in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in an adult and pediatric population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 125:235–241. 10.1177/0003489415608196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walboomers JMM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJF, Peto J, Meijer CJLM, Muñoz N. 1999. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol 189:12–19. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geraets D, Alemany L, Guimera N, de Sanjose S, de Koning M, Molijn A, Jenkins D, Bosch X, Quint W, RIS HPV TT Study Group . 2012. Detection of rare and possibly carcinogenic human papillomavirus genotypes as single infections in invasive cervical cancer. J Pathol 228:534–543. 10.1002/path.4065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halec G, Alemany L, Lloveras B, Schmitt M, Alejo M, Bosch FX, Tous S, Klaustermeier JE, Guimera N, Grabe N, Lahrmann B, Gissmann L, Quint W, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Pawlita M, Retrospective International Survey and HPV Time Trends Study Group . 2014. Pathogenic role of the eight probably/possibly carcinogenic HPV types 26, 53, 66, 67, 68, 70, 73 and 82 in cervical cancer. J Pathol 234:441–451. 10.1002/path.4405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS, Roteli-Martins CM, Teixeira J, Blatter MM, Korn AP, Quint W, Dubin G, GlaxoSmithKline HPV Vaccine Study Group . 2004. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364:1757–1765. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, Iversen OE, Olsson SE, Hoye J, Steinwall M, Riis-Johannessen G, Andersson-Ellstrom A, Elfgren K, Krogh G, Lehtinen M, Malm C, Tamms GM, Giacoletti K, Lupinacci L, Railkar R, Taddeo FJ, Bryan J, Esser MT, Sings HL, Saah AJ, Barr E. 2006. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer 95:1459–1466. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Group FIIS, Dillner J, Kjaer SK, Wheeler CM, Sigurdsson K, Iversen OE, Hernandez-Avila M, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, Garcia P, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Lehtinen M, Steben M, Bosch FX, Joura EA, Majewski S, Munoz N, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, Bryan JT, Maansson R, Lu S, Vuocolo S, Hesley TM, Barr E, Haupt R, FUTURE I/II Study Group . 2010. Four year efficacy of prophylactic human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine against low grade cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and anogenital warts: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 341:c3493. 10.1136/bmj.c3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz N, Bosch FX, Castellsague X, Diaz M, de Sanjose S, Hammouda D, Shah KV, Meijer CJ. 2004. Against which human papillomavirus types shall we vaccinate and screen? The international perspective. Int J Cancer 111:278–285. 10.1002/ijc.20244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, Bouchard C, Mao C, Mehlsen J, Moreira ED, Jr, Ngan Y, Petersen LK, Lazcano-Ponce E, Pitisuttithum P, Restrepo JA, Stuart G, Woelber L, Yang YC, Cuzick J, Garland SM, Huh W, Kjaer SK, Bautista OM, Chan IS, Chen J, Gesser R, Moeller E, Ritter M, Vuocolo S, Luxembourg A, Broad Spectrum HPVVS . 2015. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med 372:711–723. 10.1056/NEJMoa1405044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirnbauer R, Booy F, Cheng N, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 1992. Papillomavirus L1 major capsid protein self-assembles into virus-like particles that are highly immunogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89:12180–12184. 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirnbauer R, Taub J, Greenstone H, Roden R, Durst M, Gissmann L, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 1993. Efficient self-assembly of human papillomavirus type 16 L1 and L1-L2 into virus-like particles. J Virol 67:6929–6936. 10.1128/JVI.67.12.6929-6936.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose RC, Bonnez W, Reichman RC, Garcea RL. 1993. Expression of human papillomavirus type 11 L1 protein in insect cells: in vivo and in vitro assembly of viruslike particles. J Virol 67:1936–1944. 10.1128/JVI.67.4.1936-1944.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghim SJ, Jenson AB, Schlegel R. 1992. HPV-1 L1 protein expressed in cos cells displays conformational epitopes found on intact virions. Virology 190:548–552. 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91251-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou J, Sun XY, Stenzel DJ, Frazer IH. 1991. Expression of vaccinia recombinant HPV 16 L1 and L2 ORF proteins in epithelial cells is sufficient for assembly of HPV virion-like particles. Virology 185:251–257. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90772-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzich JA, Ghim SJ, Palmer-Hill FJ, White WI, Tamura JK, Bell JA, Newsome JA, Jenson AB, Schlegel R. 1995. Systemic immunization with papillomavirus L1 protein completely prevents the development of viral mucosal papillomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:11553–11557. 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitburd F, Kirnbauer R, Hubbert NL, Nonnenmacher B, Trin-Dinh-Desmarquet C, Orth G, Schiller JT, Lowy DR. 1995. Immunization with viruslike particles from cottontail rabbit papillomavirus (CRPV) can protect against experimental CRPV infection. J Virol 69:3959–3963. 10.1128/JVI.69.6.3959-3963.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirnbauer R, Chandrachud LM, O'Neil BW, Wagner ER, Grindlay GJ, Armstrong A, McGarvie GM, Schiller JT, Lowy DR, Campo MS. 1996. Virus-like particles of bovine papillomavirus type 4 in prophylactic and therapeutic immunization. Virology 219:37–44. 10.1006/viro.1996.0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day PM, Kines RC, Thompson CD, Jagu S, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2010. In vivo mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against HPV infection. Cell Host Microbe 8:260–270. 10.1016/j.chom.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei J, Ploner A, Elfstrom KM, Wang J, Roth A, Fang F, Sundstrom K, Dillner J, Sparen P. 2020. HPV vaccination and the risk of invasive cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 383:1340–1348. 10.1056/NEJMoa1917338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kjaer SK, Nygard M, Sundstrom K, Munk C, Berger S, Dzabic M, Fridrich KE, Waldstrom M, Sorbye SW, Bautista O, Group T, Luxembourg A. 2021. Long-term effectiveness of the nine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine in Scandinavian women: interim analysis after 8 years of follow-up. Hum Vaccin Immunother 17:943–949. 10.1080/21645515.2020.1839292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falcaro M, Castanon A, Ndlela B, Checchi M, Soldan K, Lopez-Bernal J, Elliss-Brookes L, Sasieni P. 2021. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet 398:2084–2092. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenblum HG, Lewis RM, Gargano JW, Querec TD, Unger ER, Markowitz LE. 2021. Declines in prevalence of human papillomavirus vaccine-type infection among females after introduction of vaccine–United States, 2003-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 70:415–420. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7012a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christensen ND, Kreider JW, Kan NC, DiAngelo SL. 1991. The open reading frame L2 of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus contains antibody-inducing neutralizing epitopes. Virology 181:572–579. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90890-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin YL, Borenstein LA, Selvakumar R, Ahmed R, Wettstein FO. 1992. Effective vaccination against papilloma development by immunization with L1 or L2 structural protein of cottontail rabbit papillomavirus. Virology 187:612–619. 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90463-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandrachud LM, Grindlay GJ, McGarvie GM, O’Neil BW, Wagner ER, Jarrett WF, Campo MS. 1995. Vaccination of cattle with the N-terminus of L2 is necessary and sufficient for preventing infection by bovine papillomavirus-4. Virology 211:204–208. 10.1006/viro.1995.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roden RB, Yutzy WHt, Fallon R, Inglis S, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2000. Minor capsid protein of human genital papillomaviruses contains subdominant, cross-neutralizing epitopes. Virology 270:254–257. 10.1006/viro.2000.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gambhira R, Karanam B, Jagu S, Roberts JN, Buck CB, Bossis I, Alphs H, Culp T, Christensen ND, Roden RB. 2007. A protective and broadly cross-neutralizing epitope of Human Papillomavirus L2. J Virol 81:13927–13931. 10.1128/JVI.00936-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang JW, Wu WH, Huang TC, Wong M, Kwak K, Ozato K, Hung CF, Roden RBS. 2018. Roles of Fc domain and exudation in L2 antibody-mediated protection against human papillomavirus. J Virol 92:e00572-18. 10.1128/JVI.00572-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Day PM, Gambhira R, Roden RB, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2008. Mechanisms of human papillomavirus type 16 neutralization by L2 cross-neutralizing and L1 type-specific antibodies. J Virol 82:4638–4646. 10.1128/JVI.00143-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Day PM, Lowy DR, Schiller JT. 2008. Heparan sulfate-independent cell binding and infection with furin-precleaved papillomavirus capsids. J Virol 82:12565–12568. 10.1128/JVI.01631-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann MF, Kalinke U, Althage A, Freer G, Burkhart C, Roost H, Aguet M, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. 1997. The role of antibody concentration and avidity in antiviral protection. Science 276:2024–2027. 10.1126/science.276.5321.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olczak P, Roden RBS. 2020. Progress in L2-based prophylactic vaccine development for protection against diverse human papillomavirus genotypes and associated diseases. Vaccines 8:568. 10.3390/vaccines8040568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fehr T, Bachmann MF, Bucher E, Kalinke U, Di Padova FE, Lang AB, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. 1997. Role of repetitive antigen patterns for induction of antibodies against antibodies. J Exp Med 185:1785–1792. 10.1084/jem.185.10.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chackerian B, Peabody DS. 2020. Factors that govern the induction of long-lived antibody responses. Viruses 12:74. 10.3390/v12010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang JW, Jagu S, Wu WH, Viscidi RP, Macgregor-Das A, Fogel JM, Kwak K, Daayana S, Kitchener H, Stern PL, Gravitt PE, Trimble CL, Roden RB. 2015. Seroepidemiology of human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) L2 and generation of L2-specific human chimeric monoclonal antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol 22:806–816. 10.1128/CVI.00799-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]