ABSTRACT

Introduction

During Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, an outbreak of combat-related invasive fungal wound infections (IFIs) emerged among casualties with dismounted blast trauma and became a priority issue for the Military Health System.

Methods

In 2011, the Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study (TIDOS) team led the Department of Defense IFI outbreak investigation to describe characteristics of IFIs among combat casualties and provide recommendations related to management of the disease. To support the outbreak investigation, existing IFI definitions and classifications utilized for immunocompromised patients were modified for use in epidemiologic research in a trauma population. Following the conclusion of the outbreak investigation, multiple retrospective analyses using a population of 77 IFI patients (injured during June 2009 to August 2011) were conducted to evaluate IFI epidemiology, wound microbiology, and diagnostics to support refinement of Joint Trauma System (JTS) clinical practice guidelines. Following cessation of combat operations in Afghanistan, the TIDOS database was comprehensively reviewed to identify patients with laboratory evidence of a fungal infection and refine the IFI classification scheme to incorporate timing of laboratory fungal evidence and include categories that denote a high or low level of suspicion for IFI. The refined IFI classification scheme was utilized in a large-scale epidemiologic assessment of casualties injured over a 5.5-year period.

Results

Among 720 combat casualties admitted to participating hospitals (2009-2014) who had histopathology and/or wound cultures collected, 94 (13%) met criteria for an IFI and 61 (8%) were classified as high suspicion of IFI. Risk factors for development of combat-related IFIs include sustaining a dismounted blast injury, experiencing a traumatic transfemoral amputation, and requiring resuscitation with large-volume (>20 units) blood transfusions. Moreover, TIDOS analyses demonstrated the adverse impact of IFIs on wound healing, particularly with order Mucorales. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay to identify filamentous fungi and support earlier IFI diagnosis was also assessed using archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens. Although the PCR-based assay had high specificity (99%), there was low sensitivity (63%); however, sensitivity improved to 83% in tissues collected from sites with angioinvasion. Data obtained from the initial IFI outbreak investigation (37 IFI patients) and subsequent TIDOS analyses (77 IFI patients) supported development and refinement of a JTS clinical practice guideline for the management of IFIs in war wounds. Furthermore, a local clinical practice guideline to screen for early tissue-based evidence of IFIs among blast casualties at the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center was critically evaluated through a TIDOS investigation, providing additional clinical practice support. Through a collaboration with the Uniformed Services University Surgical Critical Care Initiative, findings from TIDOS analyses were used to support development of a clinical decision support tool to facilitate early risk stratification.

Conclusions

Combat-related IFIs are a highly morbid complication following severe blast trauma and remain a threat for future modern warfare. Our findings have supported JTS clinical recommendations, refined IFI classification, and confirmed the utility of PCR-based assays as a complement to histopathology and/or culture to promote early diagnosis. Analyses underway or planned will add to the knowledge base of IFI epidemiology, diagnostics, prevention, and management.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive fungal wound infections (IFIs) may occur following a traumatic, penetrating injury and frequently result in substantial morbidity. Multiple surgical procedures and/or amputations are required to resolve the infection, particularly when the affected area is an extremity.1–4 An extended length of hospitalization, along with high resource utilization and cost further adds to the IFI burden. Critically ill, often immunocompromised patients (including those with trauma, septicemia, bacteremia, necrotizing fasciitis, intracranial hemorrhage, and mechanical ventilation) who develop mucormycosis had a longer length of hospitalization and cost (median of 25 days and $85,106, respectively) compared to patients without mucormycosis (median of 6 days and $45,347, respectively).5 Furthermore, IFIs are associated with high mortality with rates varying based on underlying conditions and dissemination of disease.1,4,6–9 Among 13 trauma patients with an IFI diagnosis following an EF-5 tornado in Joplin, Missouri, five (38%) died with IFI listed as either the primary or contributing factor leading to the death of three patients.10

The high burden of IFIs has been evident among combat casualties injured during recent wars. Although a small number of cases of IFIs were reported among service members injured in Iraq,11–13 the majority of cases were diagnosed among U.S. and U.K. military personnel wounded in Afghanistan during Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). A high proportion of severe polytrauma occurred in association with dismounted improvised explosive devices (IEDs) during OEF.14–20 These dismounted complex blast injuries were characterized by a traumatic amputation of at least one lower extremity, severe injury to the opposite lower extremity, and injury of the pelvic, abdominal, and/or urogenital regions.21–23 It was also not uncommon for personnel to sustain trauma (or amputation) to at least one upper extremity.23 In particular, the rate of traumatic amputations at combat support hospitals increased from 3.5 per 100 trauma admission in 2010 to 14 in 2011.24

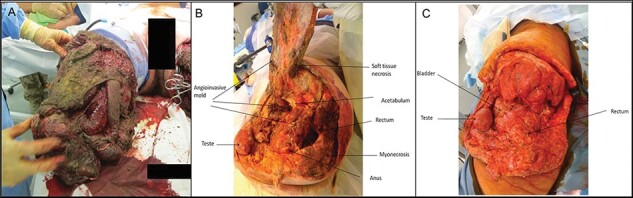

Wounds sustained from blasts were highly contaminated with debris (e.g., soil, plant matter, and shrapnel) and often required multiple surgical debridements to remove all foreign material.17 Although uncomplicated wounds generally display the initial stages of healing (e.g., wound volume contractions and tissue granulation) during hospital admission in the USA approximately 3-5 days post-injury, a typical IFI wound would develop with recurrent tissue necrosis despite serial debridements (Fig. 1).15,16 These wounded warriors frequently required multiple surgical procedures, at times including total hip disarticulation and hemipelvectomies.15,16,25,26

FIGURE 1.

Progression of an invasive fungal wound infection following blast injury. (A) Wound immediately following blast injury, demonstrating severity of contamination. (B) Following surgical debridement and high-level lower extremity amputation with necrotic fibrinous material documented on histopathology with aseptate mold angioinvasion (initial presentation). (C) Wound appearance after serial debridements, hemipelvectomy, and antifungal therapy (8 days after photo was taken of wound in 1B). Wounds in 1B and 1C are from the same patients. Reprinted from Tribble and Rodriguez (2014)17 with permission from Springer Nature.

Combat-related IFIs were identified as a priority issue within the Department of Defense (DoD) Joint Trauma System (JTS), and the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP) Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study (TIDOS) team was tasked with conducting an IFI outbreak investigation to support the development of recommendations related to the disease. Following the initial outbreak investigation, TIDOS investigators have published a series of investigations related to combat-related IFI epidemiology, risk factors, outcomes, wound microbiology, and diagnostics. Herein, we review the results of the TIDOS IFI studies and discuss ongoing/upcoming research.

INVASIVE FUNGAL WOUND INFECTION EPIDEMIOLOGY

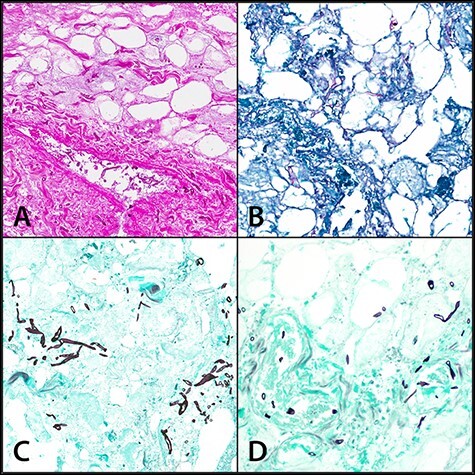

For the TIDOS IFI outbreak investigation, the 2008 Mycoses Study Group–revised definitions for fungal infections in immunocompromised individuals were modified for the trauma setting.27 Specifically, for a wound to be designated as an IFI, we required persistent tissue necrosis (i.e., after at least two surgical debridements) and laboratory evidence of fungal infection (i.e., either positive culture and/or histopathological evidence).16 Cases identified as an IFI were further classified based on the strength of evidence as proven, probable, or possible IFI. To be classified as a proven IFI, we required the presence of angioinvasion on histopathology (Fig. 2), while a probable IFI was defined by the presence of fungal elements on histopathology without angioinvasion. Lastly, a possible IFI had growth of filamentous fungi from wound cultures without corresponding histopathological evidence (i.e., histopathology was either negative or not sent for examination).16

FIGURE 2.

Necrotic fibroadipose tissue with fungal organisms consistent with Zygomycetes species (broad, ribbon-like hyphae). Angioinvasion can be seen in parts A and D. (A) hematoxylin and eosin stain, 20X; (B) Periodic Acid-Schiff stain, 20X; (C and D) Gomori Methenamine Silver stain, 20X. Reprinted from Heaton et al.43 (BMC original publisher)

The initial TIDOS IFI outbreak investigation assessed 37 wounded military personnel who sustained trauma between June 2009 and December 2010 and developed an IFI.15,28 Epidemiologic analysis of these patients identified frequently observed characteristics related to injury mechanism (i.e., blast), pattern of injury (i.e., traumatic amputations), and early casualty care (i.e., large-volume blood transfusions; >20 units). These findings through a widely disseminated DoD Technical Report28 (in real time) were utilized to support the development of a JTS clinical practice guideline (CPG) for the management of IFIs in war wounds, which was published on November 1, 2012 (superseded by guideline published on August 4, 201629,30)

Expanding on the findings of the outbreak investigation, data collected from 1,133 combat casualties who were admitted to the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) before being transferred to a participating hospital in the USA between June 2009 and August 2011 were examined. A total of 77 (6.8%) patients with an IFI were identified, resulting in the largest published cohort of trauma-related IFIs at that time.16

For IFI patients in the TIDOS population, blast trauma was the predominant mechanism of injury (96%) with the majority occurring while dismounted (89%). In addition, injuries were largely sustained in the Helmand and Kandahar provinces of southern Afghanistan (99%).16 Analysis of environmental characteristics of Afghanistan found that the southern region (compared to eastern Afghanistan) was associated with fungal contamination of wounds. This region is characterized by lower elevation, warmer temperatures, and greater isothermality.18

Consistent with the substantial proportion of dismounted blast trauma, IFI patients had high injury severity (median injury severity score [ISS] of 21) and required large-volume blood transfusions (median of 29 units of packed red blood cells within 24 h of injury).31 In addition, 65% of the patients had an amputation of the lower extremities, 1% had an upper extremity amputation, and 13% had both a lower and upper extremity amputation.16 Among the patients with lower extremity amputations, transfemoral amputations were prevalent (80% of amputations). Approximately 74% of the IFI patients also had trauma to the genitalia/groin and 26% had pelvic or hip injuries.31 High-level amputations (i.e., total hip disarticulation or hemipelvectomy) were reported in 19% of cases and 8% of the patients died.16

Based on the TIDOS combat-related IFI classification scheme,16 27 IFI cases were classified as proven, 27 as probable, and 23 as possible. There were no significant differences in injury circumstances or clinical characteristics between the proven/probable and possible cases; however, proven/probable IFI cases had a significantly higher number of operating room visits (median of 16 versus 13; P = .03).16 Nonetheless, clinical outcomes were comparable between the groups, indicating that the classification system is a useful tool for surveillance and research.

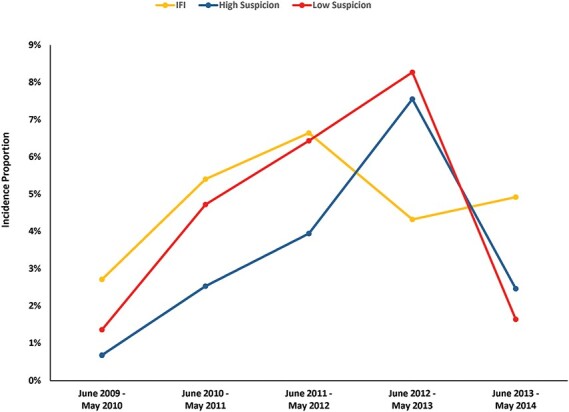

As part of a recent comprehensive review of the TIDOS 5.5-year dataset for patients with laboratory evidence of a fungal infection, the IFI definition was revised to reflect the timing of laboratory evidence in relation to observed wound necrosis. In addition, the refined classification scheme included the development of new categories of High Suspicion of IFI and Low Suspicion of IFI for patients that had laboratory evidence of a fungus but did not have persistent necrosis or laboratory abnormalities to be classified as an IFI.32 Figure 3 depicts the proportion of patients meeting criteria for IFI, High Suspicion, and Low Suspicion over a 5-year period. The introduction of this classification is to provide the clinician with a risk stratification schema to prioritize care and treatment.

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of wounded military personnel meeting criteria for invasive fungal wound infection (IFI), High Suspicion of IFI, and Low Suspicion of IFI.32 The patient population is restricted to military personnel with combat-related open extremity injuries sustained in Afghanistan and admitted to a participating hospital in the United States (N=1932). The total number of patients meeting criteria for the different study years were: 442 in 2009/2010; 593 in 2010/2011; 482 in 2011/2012; 278 in 2012/2013; and 122 in 2013/2014.

IFI Risk Factors

Following identification of characteristics common to patients with an IFI, the next step involved confirmation of risk factors for developing the infection. Seventy-six IFI cases were matched to 150 controls using date of injury (±3 months) and ISS (±10) and assessed in a multivariable logistic regression model. Independent predictors of an IFI were sustaining a blast injury (odds ratio [OR]: 4.1; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1-29.6) while dismounted (OR: 8.5; 95% CI: 1.2-59.8), having a traumatic transfemoral amputation (OR: 4.1; 95% CI: 1.3-12.7), and requiring ≥20 units of packed red blood cells within 24 h of injury (OR: 7.0; 95% CI: 2.5-19.7).31

These risk factors are consistent with independent predictors identified for infectious complications (any type) following deployment-related trauma. In particular, IED blast mechanism of injury, ISS ≥16, receipt of blood within 24 h of injury, and intensive care unit admission have been associated with infection risk.33 The association with blood volume is unsurprising as the common consequence of blood transfusions is a temporary immunosuppressive state in the recipient.34–36 Furthermore, massive blood transfusions may result in a state of iron overload (e.g., hemochromatosis), and there is also evidence suggesting a link between serum iron availability and growth of fungi from the order Mucorales.37–39

In order to improve patient outcomes, early stratification of trauma patients with regard to IFI risk was needed. As a result, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Surgical Critical Care Initiative (http://www.sc2i.org/tools/) collaborated with TIDOS investigators to develop a web-based clinical decision support tool to assist providers with treatment decisions in theater and at LRMC. Using TIDOS data from 227 combat casualties, and validated using a separate TIDOS data from an additional 350 trauma patients, a Bayesian Belief Network was designed to predict the likelihood of developing an IFI using established risk factors. Although preliminary evaluation found that the clinical tools produced clinically robust models that may facilitate early diagnosis of IFI patients and improve the timing of antifungal treatment, further validation of the models are needed.40

Clinical Mycology and Microbiology

Fungi from the order Mucorales are typically found in soil with decaying vegetation and have been associated with opportunistic infections following trauma.3 Similarly, mucormycetes are frequently identified as the etiologic agent in combat-related IFIs resulting from dismounted blast trauma,13,16,41 where wounds are impregnated with soil and debris.12,17 It is important to note that wounds may also be colonized with fungi, which is indicated by growth of fungi on cultures without corresponding recurrent wound necrosis following serial debridement.42

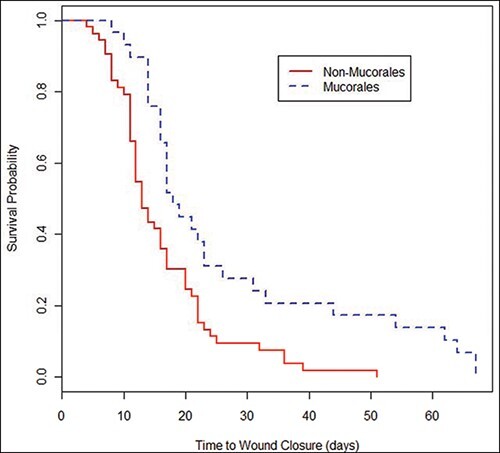

An evaluation of 82 IFI wounds found that the majority were polymicrobial with 27% growing more than one fungus and 63% isolating fungi plus bacteria. Fungi from the order Mucorales (35%) were the most common followed by Aspergillus spp. (29%) and Fusarium spp. (21%). Regarding bacteria, approximately 45% of the IFI wounds grew Enterococcus spp., while 23% grew Escherichia coli, 20% Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and 20% Acinetobacter spp. In addition, multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli were isolated from 35% of the IFI wounds. When compared to 63 wounds with bacterial skin and soft-tissue infections and 73 wounds with no infections, the IFI wounds had a longer time from injury to wound closure compared to both groups (median of 16 days versus 12 days and 9 days, respectively; P < .01). Furthermore, when compared to IFI wounds with non-Mucorales growth, IFI wounds with Mucorales growth had a significantly longer duration to wound closure (median of 17 days versus 13 days; P < .001; Fig. 4).41

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival plot of time to wound closure based on the presence of Mucorales among wounds with invasive fungal infections. Analysis included 29 wounds with and 53 wounds without Mucorales growth. Log-rank Chi-square: 10.4 (p=0.001); Wilcoxon Chi-square: 9.7 (p=0.002). Figure and legend reprinted from Warkentien et al. 201541 with permission of the American Society for Microbiology.

Diagnostics

Early diagnosis and subsequent timely initiation of treatment are cornerstones of effective management of IFIs. As previously stated, both histopathological examination (i.e., angioinvasion or fungal elements visualized without tissue invasion) and fungal growth from wound cultures are used to diagnose IFIs16; however, histopathology is preferred as fungal cultures are often insensitive.43 In our population of 77 IFI patients, 54 (70%) were diagnosed based on histopathological findings. Among the 23 patients diagnosed using culture data, 10 had negative histopathology and 13 did not have specimens sent for histopathogical examination.16

Routine histopathological examination generally involves staining permanent sections of biopsy specimens with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E); although it is capable of staining the fungal cell wall, H&E does have inherent limitations. As a result, specialized stains (i.e., Gomori methenamine silver [GMS] and periodic acid–Schiff [PAS]) are frequently used when an IFI is suspected.44,45 One analysis examined the utility of specialized histochemical stains for fungal identification using 74 tissue specimens stained with both GMS and PAS. The results found that the stains were 84% concordant (95% CI: 70-97%; P = .38), so neither was superior for identifying fungal elements. Nonetheless, GMS had a lower rate of false negatives (15% versus 44% with PAS), suggesting that it may be more suitable for use in the identification of mucormycetes.43 The findings from 147 frozen section specimens were also compared against permanent sections. Although frozen sections had a specificity of 98%, the sensitivity was 60%, indicating that while frozen sections may be useful in aiding the diagnosis of an IFI, it should not be used as a stand-alone method.43 These analyses provided evidence to support DoD surgical pathology practice.

Due to the limitations of culture and histopathology related to fungal identification, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based methods are being retrospectively evaluated to support future diagnostic approaches. Recently, a TIDOS-based analysis evaluated a PCR-based assay using archived formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens with positive histopathology.46 When compared to traditional culture, the PCR-based assay was more sensitive in identifying fungi from the order Mucorales, particularly Saksenaea spp. Overall, the PCR-based assay had a specificity of 99% and sensitivity of 63%; however, sensitivity improved to 83% in tissues collected from wounds from angioinvasion. Owing to improved detection of fungi from the order Mucorales, the PCR-based assay would be a useful complement to histopathology and/or culture. Further examination of the assay using specimens collected from patients with IFIs diagnosed based on cultures and not histopathology is underway. In addition, semi-nested assays targeted to clinically relevant fungi and a commercial, real-time assay for the detection of mucormycetes are also being assessed.

Management

Following the recognition of the IFI outbreak among combat casualties with blast-related trauma, a process improvement initiative (referred to as the “Blast” CPG) was implemented at LRMC in February 2011 with the goal of promoting earlier IFI diagnosis and improving the timing of antifungal therapy initiation in high-risk patients. Surgical debridement is the cornerstone of IFI management, and a detailed description of combat trauma wound care is provided by Tribble and Rodriguez.17 Patients were classified through the Blast CPG as high risk for IFI if they sustained severe injuries from a dismounted blast, resulting in the collection of wound tissue specimen biopsies for histopathological examination. In addition, fungal/bacterial cultures were obtained during the first debridement procedure at LRMC (often the patient’s second or third overall debridement).

After implementation of the Blast CPG, the TIDOS team investigated adherence and outcomes following the practice change. A significant reduction in the time from injury to IFI diagnosis (median of 3 days versus 9 days pre-Blast CPG) and initiation of antifungal therapy (median of 7 days versus 15 days pre-Blast CPG) was observed.47 Although there was no significant difference in clinical outcomes when comparing the patients before and after the Blast CPG implementation, the endpoints were not necessarily specific to IFI (e.g., length of hospitalization, stay in the intensive care unit, and number of operating room visits) and may not have been the best indicator of the impact of the Blast CPG. Importantly, the overall case fatality rate declined from approximately 11% to 7%. In addition, a decrease in the proportion of proven IFI (i.e., angioinvasion) following the implementation of the Blast CPG was also observed, possibly related to earlier therapeutic intervention.47

In 2012, the JTS published its first CPG on the management of IFI in war wounds with recommendations developed using the findings of the TIDOS IFI outbreak investigation. The CPG was subsequently superseded by a revised version published in 2016, which was heavily supported by TIDOS IFI analyses.29,30 In the JTS CPG, dual antifungal therapy (liposomal amphotericin B and a triazole) is recommended as previously emphasized and disseminated through the TIDOS DoD IFI Outbreak Technical Report when recurrent wound necrosis is observed. Liposomal amphotericin B is the preferred agent due to its effectiveness against mucormycetes and low risk of nephrotoxicity. Nevertheless, voriconazole or posaconazole is also recommended due to the polymicrobial nature of IFI wounds.29 In particular, IFI wounds have been shown to grown fungi resistant to liposomal amphotericin B, including Aspergillus terreus.41 As a result, antifungal susceptibilities of fungal isolates collected from patients admitted to the Brooke Army Medical Center (2009-2013) were examined.48 Due to the black box warning for intravenous voriconazole related to concerns regarding use in patients with renal insufficiency,49 a TIDOS analysis is underway to assess nephrotoxic effects among patients who received voriconazole.

Outcomes

Patients who develop an IFI frequently require surgical amputations, as well as revisions to a higher proximal amputation level in order to manage the disease.15,16,25,26 In a retrospective review at a military burn center, 11 patients with mucormycosis were identified (4.9 per 1,000 admissions). Ten required surgical amputations and mortality was attributed to mucormycosis in six patients.50 To effectively quantify the impact of an IFI on orthopedic outcomes, the TIDOS team conducted a case–control analysis utilizing 71 IFI patients with 112 fungal-infected wounds matched to 160 control patients with 315 non-IFI wounds. Wounds that had a fungal infection were found to require a significantly higher number of operating room visits and had a longer duration following injury to wound closure. Furthermore, the fungal-infected wounds had significantly more changes in amputation level compared to the control wounds. In particular, significantly more IFI wounds had a revision of a transfemoral amputation to either a hemipelvectomy or hip disarticulation. Furthermore, 38% of the IFI wounds required a return to the operating room after wound closure due to infectious complications or drainage. In a multivariate analysis, having a wound without a fungal infection was independently associated with a shorter time following injury to wound closure (hazard ratio: 1.5; 95% CI: 1.2-2.0).51 These findings provide specific evidence of the adverse impact an IFI has on wound healing and patient prognosis following severe trauma. Additional analyses to evaluate outcomes with regard to antifungal therapy are needed.

Future Research

Using the refined IFI classification scheme, evaluation of IFI patients over a 5.5-year period is planned, including a reassessment of risk factors and clinical outcomes related to specific surgical and medical treatments associated with mycology identified through use of molecular diagnostics. Furthermore, a collaboration with the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence Wound Infection Surveillance Programme is underway to compare epidemiology and outcomes among U.S. and U.K. IFI patients in order to determine best practices. These findings will be used to support further refinement of the JTS CPG for the prevention and management of IFIs in war wounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program TIDOS study team of clinical coordinators, microbiology technicians, data managers, clinical site managers, and administrative support personnel for their tireless hours to ensure the success of this project.

Contributor Information

CAPT (Ret.) Carlos J Rodriguez, John Peter Smith Hospital, Fort Worth, TX 76104, USA.

Anuradha Ganesan, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics Department, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA; Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817, USA; Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD 20852, USA.

Faraz Shaikh, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics Department, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA; Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817, USA.

M Leigh Carson, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics Department, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA; Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817, USA.

William Bradley, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics Department, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA; Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD 20817, USA.

CDR Tyler E Warkentien, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD 20852, USA.

David R Tribble, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics Department, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD 20814, USA.

FUNDING

This work (IDCRP-024) was conducted by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, a DoD program executed through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics through a cooperative agreement with the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc. (HJF). This project has been funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Health [Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072], the Defense Health Program, U.S. DoD, under award HU0001190002, the Department of the Navy under the Wounded, Ill, and Injured Program, and the Defense Medical Research and Development Program.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Skiada A, Petrikkos G: Cutaneous zygomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15(Suppl 5): 41–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vitrat-Hincky V, Lebeau B, Bozonnet E, et al. : Severe filamentous fungal infections after widespread tissue damage due to traumatic injury: six cases and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis 2009; 41(6-7): 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ribes JA, Vanover-Sams CL, Baker DJ: Zygomycetes in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13(2): 236–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ingram PR, Suthananthan AE, Rajan R, et al. : Cutaneous mucormycosis and motor vehicle accidents: findings from an Australian case series. Med Mycol 2014; 52(8): 819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Huang H, Chaudhari P, Paly VF, Menzin J: Hospital days, hospitalization costs, and inpatient mortality among patients with mucormycosis: a retrospective analysis of US hospital discharge data. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14: 310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Drogari-Apiranthitou M: Epidemiology of mucormycosis in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20(Suppl 6): 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. : Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 41(5): 634–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kennedy KJ, Daveson K, Slavin MA, et al. : Mucormycosis in Australia: contemporary epidemiology and outcomes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22(8): 775–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zahoor B, Kent S, Wall D: Cutaneous mucormycosis secondary to penetrative trauma. Injury 2016; 47(7): 1383–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. : Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med 2012; 367(23): 2214–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paolino KM, Henry JA, Hospenthal DR, Wortmann GW, Hartzell JD: Invasive fungal infections following combat-related injury. Mil Med 2012; 177(6): 681–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tully CC, Romanelli AM, Sutton DA, Wickes BL, Hospenthal DR: Fatal Actinomucor elegans var. kuwaitiensis infection following combat trauma. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47(10): 3394–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hospenthal DR, Chung KK, Lairet K, et al. : Saksenaea erythrospora infection following combat trauma. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49(10): 3707–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evriviades D, Jeffery S, Cubison T, Lawton G, Gill M, Mortiboy D: Shaping the military wound: issues surrounding the reconstruction of injured servicemen at the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2011; 366(1562): 219–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Warkentien T, Rodriguez C, Lloyd B, et al. : Invasive mold infections following combat-related injuries. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55(11): 1441–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Weintrob AC, Weisbrod AB, Dunne JR, et al. : Combat trauma-associated invasive fungal wound infections: epidemiology and clinical classification. Epidemiol Infect 2015; 143(1): 214–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tribble DR, Rodriguez CJ: Combat-related invasive fungal wound infections. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 2014; 8(4): 277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tribble DR, Rodriguez CJ, Weintrob AC, et al. : Environmental factors related to fungal wound contamination after combat trauma in Afghanistan, 2009-2011. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21(10): 1759–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Radowsky JS, Strawn AA, Sherwood J, Braden A, Liston W: Invasive mucormycosis and aspergillosis in a healthy 22-year-old battle casualty: case report. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2011; 12(5): 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Calvano TP, Blatz PJ, Vento TJ, et al. : Pythium aphanidermatum infection following combat trauma. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49(10): 3710–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Andersen RC, Fleming M, Forsberg JA, et al. : Dismounted complex blast injury. J Surg Orthop Adv 2012; 21(1): 2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleming M, Waterman S, Dunne J, D’Alleyrand JC, Andersen RC: Dismounted complex blast injuries: patterns of injuries and resource utilization associated with the multiple extremity amputee. J Surg Orthop Adv 2012; 21(1): 32–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ficke JR, Eastridge BJ, Butler F, et al. : Dismounted complex blast injury report of the army dismounted complex blast injury task force. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73(6 Suppl 5): S520–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krueger CA, Wenke JC, Ficke JR: Ten years at war: comprehensive analysis of amputation trends. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012; 73(6 Suppl 5): S438–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lundy JB, Driscoll IR: Experience with proctectomy to manage combat casualties sustaining catastrophic perineal blast injury complicated by invasive mucor soft-tissue infections. Mil Med 2014; 179(3): e347–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. D’Alleyrand JC, Lewandowski LR, Forsberg JA, et al. : Combat-related hemipelvectomy: 14 cases, a review of the literature and lessons learned. J Orthop Trauma 2015; 29(12): e493–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, et al. : Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46(12): 1813–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trauma Infectious Diseases Outcomes Study Group : Department of Defense technical report—invasive fungal infection case investigation. Bethesda, MD, Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. Available at https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/1072934.pdf, April 11, 2011; accessed February 16, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rodriguez CJ, Tribble DR, Murray CK, et al. : Invasive fungal infection in war wounds (CPG: 28). Joint Trauma System, 2016. Available at https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/JTS_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_(CPGs)/Invasive_Fungal_Infection_04_Aug_2016_ID28.pdf; accessed November 16, 2018.

- 30. Rodriguez CJ, Tribble DR, Malone DL, et al. : Treatment of suspected invasive fungal infection in war wounds. Mil Med 2018; 183(Suppl 2): 142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rodriguez C, Weintrob AC, Shah J, et al. : Risk factors associated with invasive fungal infections in combat trauma. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014; 15(5): 521–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ganesan A, Shaikh F, Bradley W, et al. : Classification of trauma-associated invasive fungal infections to support wound treatment decisions. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25(9): 1639–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tribble DR, Li P, Warkentien TE, et al. : Impact of operational theater on combat and noncombat trauma-related infections. Mil Med 2016; 181(10): 1258–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dunne JR, Hawksworth JS, Stojadinovic A, et al. : Perioperative blood transfusion in combat casualties: a pilot study. J Trauma 2009; 66(4 Suppl): S150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dunne JR, Riddle MS, Danko J, Hayden R, Petersen K: Blood transfusion is associated with infection and increased resource utilization in combat casualties. Am Surg 2006; 72(7): 619–25; discussion 625–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Blumberg N, Heal JM: Immunomodulation by blood transfusion: an evolving scientific and clinical challenge. Am J Med 1996; 101(3): 299–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr.: Iron acquisition: a novel perspective on mucormycosis pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2008; 21(6): 620–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP: Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54(Suppl 1): S16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Spellberg B, Edwards J Jr., Ibrahim A: Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2005; 18(3): 556–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Potter BK, Forsberg JA, Silvius E, et al. : Combat-related invasive fungal infections: development of a clinically applicable clinical decision support system for early risk stratification. Mil Med 2019; 184(1–2): e235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Warkentien TE, Shaikh F, Weintrob AC, et al. : Impact of Mucorales and other invasive molds on clinical outcomes of polymicrobial traumatic wound infections. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53(7): 2262–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rodriguez CJ, Weintrob AC, Dunne JR, et al. : Clinical relevance of mold culture positivity with and without recurrent wound necrosis following combat-related injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014; 77(5): 769–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Heaton SM, Weintrob AC, Downing K, et al. : Histopathological techniques for the diagnosis of combat-related invasive fungal wound infections. BMC Clin Pathol 2016; 16(1): 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guarner J, Brandt ME: Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the twenty-first century. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(2): 247–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaufman L: Immunohistologic diagnosis of systemic mycoses: an update. Eur J Epidemiol 1992; 8(3): 377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ganesan A, Wells J, Shaikh F, et al. : Molecular detection of filamentous fungi in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens in invasive fungal wound infections is feasible with high specificity. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58(1): e01259–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lloyd B, Weintrob A, Rodriguez C, et al. : Effect of early screening for invasive fungal infections in U.S. service members with explosive blast injuries. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2014; 15(5): 619–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Keaton N, Mende K, Beckius M, et al. : Antifungal resistance patterns in molds isolated from wounds of combat-related trauma patients. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4(Suppl 1): S78–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pfizer Inc : Vfend (voriconazole). 2010. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021266s032lbl.pdf; accessed December 27, 2018.

- 50. Mitchell TA, Hardin MO, Murray CK, et al. : Mucormycosis attributed mortality: a seven-year review of surgical and medical management. Burns 2014; 40(8): 1689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lewandowski LR, Weintrob AC, Tribble DR, et al. : Early complications and outcomes in combat injury related invasive fungal wound infections: a case-control analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2016; 30(3): e93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]