Abstract

A full-scale study evaluating an inoculum addition to stimulate in situ bioremediation of oily-sludge-contaminated soil was conducted at an oil refinery where the indigenous population of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in the soil was very low (103 to 104 CFU/g of soil). A feasibility study was conducted prior to the full-scale bioremediation study. In this feasibility study, out of six treatments, the application of a bacterial consortium and nutrients resulted in maximum biodegradation of total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH) in 120 days. Therefore, this treatment was selected for the full-scale study. In the full-scale study, plots A and B were treated with a bacterial consortium and nutrients, which resulted in 92.0 and 89.7% removal of TPH, respectively, in 1 year, compared to 14.0% removal of TPH in the control plot C. In plot A, the alkane fraction of TPH was reduced by 94.2%, the aromatic fraction of TPH was reduced by 91.9%, and NSO (nitrogen-, sulfur-, and oxygen-containing compound) and asphaltene fractions of TPH were reduced by 85.2% in 1 year. Similarly, in plot B the degradation of alkane, aromatic, and NSO plus asphaltene fractions of TPH was 95.1, 94.8, and 63.5%, respectively, in 345 days. However, in plot C, removal of alkane (17.3%), aromatic (12.9%), and NSO plus asphaltene (5.8%) fractions was much less. The population of introduced Acinetobacter baumannii strains in plots A and B was stable even after 1 year. Physical and chemical properties of the soil at the bioremediation site improved significantly in 1 year.

One of the major problems faced by oil refineries is the safe disposal of oily sludge generated during the processing of crude oil. Improper disposal of oily sludge leads to environmental pollution, particularly soil contamination, and poses a serious threat to groundwater. Many of the constituents of oily sludge are carcinogenic and potent immunotoxicants (24). Among the many techniques employed to decontaminate the affected sites, in situ bioremediation using indigenous microorganisms is by far the most widely used (3, 9, 11, 12, 21, 30). This approach to reclaiming contaminated land reduces the threat to groundwater and enhances the rate of biodegradation.

Many microbial strains, each capable of degrading a specific compound, are available commercially for bioremediation (6, 17, 27). However, oily sludge is a complex mixture of alkane, aromatic, NSO (nitrogen-, sulfur-, and oxygen-containing compounds), and asphaltene fractions, and a single bacterial species has only limited capacity to degrade all the fractions of hydrocarbons present (4, 5, 9, 20). Indigenous bacteria in the soil can degrade a wide range of target constituents of the oily sludge, but their population and efficiency are affected when any toxic contaminant is present at high concentrations (3, 11, 22). The reintroduction after enrichment of indigenous microorganisms isolated from a contaminated site helps to overcome this problem, as the microorganisms can degrade the constituents and have a higher tolerance to toxicity (14, 17, 21). The selected indigenous bacterial consortium has been shown to assist in bioremediation and has the advantage of being resistant to variations in natural environment (12, 21). To effectively transfer the microorganisms to the contaminated site, a number of carrier materials, mostly agricultural by-products, are being used (8, 23, 34). The carrier materials transfer the microorganisms without affecting their population or capacity to degrade oily sludge. For bioremediation, survival of the constituent isolates of the bacterial consortium is as important as any other factor (25, 28). However, a major problem in microbial ecology is ascertaining the identity of the target bacterial strains. Such recent developments in molecular techniques as DNA:DNA hybridization and PCR have made it easier to identify the introduced strains and assess their survival (10, 13, 15, 28, 31, 32).

The site used for the study was a part of the Mathura refinery, which is situated 150 km south of Delhi. The indigenous population of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria in the soil at the bioremediation site in this study was not adequate to stimulate bioremediation. Therefore, the first aim of the present study was to assess and evaluate the efficacy of inoculum addition for in situ bioremediation of oily-sludge-contaminated soil. The second aim was to assess the survival of the introduced bacterial strains during the course of the study. The indigenously selected bacterial consortium consisted of five bacterial strains, which were found to degrade alkane, aromatic, NSO, and asphaltene fractions of oily sludge. A feasibility study on reclamation of land contaminated with oily sludge was carried out with different combinations of treatments prior to the full-scale bioremediation study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of bacterial consortium.

A bacterial consortium that could degrade oily sludge was developed in minimal salt medium (18), with oily sludge as the sole source of carbon and energy, from a sample of soil contaminated with crude oil. The sample was collected from an oil well located in Mehasna, in Gujarat in western India, as described elsewhere (2, 18, 19). This indigenous bacterial consortium consisting of five bacterial isolates was selected for the present study. The oily-sludge-degrading efficiency (qualitative and quantitative) of individual bacterial isolates was screened on minimal salt medium as described elsewhere (19), using oily sludge as the sole carbon and energy source. These five bacterial isolates could degrade aliphatic, aromatic, NSO, and asphaltene fractions of the oily sludge. These selected isolates were characterized and identified using biochemical tests and 16S rRNA sequencing from MIDI Labs, Newark, Del. Four of these isolates were identified: two isolates (S19 and S30) were identified as Acinetobacter baumannii (previously identified as Acinetobacter calcoaceticus by fatty acid methyl ester analysis), the third (S20) was identified as Burkholderia cepacia, and the fourth (S24) was a species of Pseudomonas. The fifth isolate (S26) could not be identified. A. baumannii S19 was resistant to spectinomycin and ampicillin (50 μg/ml each), whereas A. baumannii S30 was resistant to vancomycin (20 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml). Strains S19 and S30 could degrade the alkane fractions efficiently (18), and S20 could degrade the aromatic and NSO fractions of the oily sludge. S24 and S26 could degrade the asphaltene and alkane fractions of the oily sludge. All the constituent strains of the selected consortium were stored in 25% glycerol at −70°C.

To prepare the inoculum, bacterial isolates were grown separately in 2-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 500 ml of the minimal medium and molasses (2%) as the sole carbon and energy source (1). All the isolates were grown to mid-log phase (108 CFU/ml) and then mixed in equal proportions. The mixed culture was used as the inoculum (5%) for large-scale culture in a bioreactor (Bioflow 3000; New Brunswick) with a working volume of 10 liters. The same minimal salt medium with molasses (2%, wt/vol) as the sole carbon source was used in the bioreactor for large-scale culture. The growth conditions in the bioreactor were as follows: temperature, 32°C; aeration, 0.75 volume of air/volume of medium/min; agitation, 250 rpm; pH 7.0 (adjusted with 1 N HCl-NaOH); and duration of growth, 15 h. Silicone oil was added to control excessive foaming in the bioreactor. After growth, the culture was immobilized onto the selected carrier material, corncob powder, a biodegradable agricultural residue, by simple mixing in a 1:3 ratio of carrier material and culture. A total bacterial count (on Luria-Bertani agar [LA] plates) of 1010 CFU/g of carrier material with a moisture level of 70% was maintained while the bacterial consortium was immobilized. The carrier-based culture was dispensed into sterile reusable polyethylene bags (4 kg of culture immobilized onto carrier material in each 10-kg polyethylene bag) and stored at 4°C after the bag was aseptically sealed. In a previous study, various carrier materials were screened to determine the survival of carrier-based culture by monitoring the CFU counts (on LA plates) at 15-day intervals. Out of various carrier materials screened, corncob powder yielded stable CFU counts (1010 CFU/g of carrier material) during storage at 4°C for a period of 3 months; therefore, corncob powder was selected as carrier material for the present study.

Feasibility study on bioremediation of soil contaminated with oily sludge.

Prior to the full-scale study, a feasibility study on bioremediation of soil contaminated with oily sludge was carried out at a full-scale bioremediation site. The site was an old sludge-dumping site containing various types of oily sludge (crude tank sludge, effluent treatment plant sludge, and distillation column sludge). The sludge lying on contaminated land was characterized by estimation of total petroleum hydrocarbon (TPH), analysis of alkane, aromatic, NSO, and asphaltene fractions in TPH, and heavy metal analysis before bioremediation was initiated. The total area (576 m2) of the feasibility study was divided into 24 plots (four replicate plots for each treatment), 1 by 1 m each and separated by a gap of 2 m. The experimental design chosen was a completely randomized block design. The treatments were as follows: (i) nutrients alone; (ii) bacterial consortium (containing five isolates); (iii) bacterial consortium and nutrients together; (iv) A. baumannii S30 and B. cepacia; (v) A. baumannii S30, B. cepacia, and nutrients; and (vi) a control where no treatment was done.

Site selection, experimental design, and treatments.

A full-scale bioremediation study on oily-sludge-contaminated soil was conducted (January 1998 to December 1998) at the Mathura refinery after completion of the feasibility study at the same site. A 1-ha plot of land contaminated with oily sludge was selected for in situ bioremediation. The site was marked into three plots, designated A, B, and C, and each plot was separated by a 10-m gap. The areas of plots A, B, and C were 4,000, 5,900, and 100 m2, respectively. One kilogram of the carrier-based bacterial consortium and 50 liters of the nutrient mixture (67.5 g of KNO3, 8.65 g of K2HPO4, 2.5 g of MnSO4 · 0.2H2O, 0.005 g of FeSO4, 0.05 g of CaCl2 · 0.2H2O, 0.005 g of ZnSO4 · 0.7H2O, 0.005 g of CuSO4 · 0.5H2O, 0.05 g of CoCl2, 0.005 g of AlK (SO4)2, 0.005 g of H3BO4, and 0.005 g of Na2MoO4) for every 10-m2 area were added to plots A and B, while plot C was maintained as a control. The soil in all the plots was thoroughly tilled using a tractor fitted with a harrow and watered at 20-day intervals to maintain proper aeration and moisture levels during the bioremediation. To assess the rate at which the TPH was being degraded in treatment plots, samples were collected before application of the bacterial consortium (time zero) and every 45 days thereafter for a year. In situ bioremediation studies in plot B were initiated 15 days after those in plot A. To make the sampling of both the plots concurrent, the first sampling in plot B was done at 30 days instead of at 45 days. Soil was sampled from 36 points from plots A and B and 12 points from plot C using a hollow pipe with a diameter of 4 cm. Sampling was done from the 25-cm horizon (0∼25 cm) and from different depths of 25 to ∼50, 50 to ∼75, and 75 to ∼100 cm to determine the extent of seepage of oily sludge.

Analysis of soil at the bioremediation site.

Physical and chemical properties of the soil samples withdrawn from the 0-to-∼25-cm horizon at the onset and at the end of the treatment were characterized. Air-dried and pulverized soil samples were analyzed for organic carbon, nitrogen, available phosphorus, potassium, moisture level, and pH using standard methods (16). Various heavy metals were analyzed from the mixed soil samples collected from plots A, B, and C at time zero (before initiation of the experiment) and at the end of the study. Heavy metals in oily sludge were also analyzed using atomic absorption spectroscopy (26).

Extraction of TPH from oily-sludge-contaminated soil.

TPH from 10 g of soil was consecutively extracted with hexane, methylene chloride, and chloroform (100 ml each). All the three extracts were pooled and dried at room temperature by evaporation of solvents under a gentle nitrogen stream in a fume hood. After evaporation, the amount of residual TPH recovered was determined gravimetrically.

Fractionation of TPH and analysis of fractions.

After gravimetric quantification, the residual TPH was fractionated into alkane, aromatic, asphaltene, and NSO fractions on a silica gel column (33). The TPH (500 mg) was dissolved in n-pentane and separated into soluble and insoluble fractions (asphaltene). The soluble fraction was loaded on a silica gel column and eluted with different solvents. The alkane fraction was eluted with 100 ml of hexane, and then the aromatic fraction was eluted with 100 ml of benzene. Finally, the NSO fraction was eluted with methanol and chloroform (100 ml each). The alkane fraction was analyzed by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID; 5890 series II; Hewlett Packard) using a 30-m-long wide-bore DB5 column (0.53 mm by 1 μm [film thickness]), while the aromatic fraction was analyzed by GC-FID using a 30-m-long DB5.625 column (0.25-mm inside diameter, 0.25-μm film thickness). During analysis, the injector and the detector temperature for GC were maintained at 300°C and the oven temperature was programmed to rise from 80 to 240°C in 5°C/min increments and to hold at 240°C for 30 min. Individual compounds present in the alkane and aromatic fractions were determined by matching the retention times with authentic standards (Sigma Chemicals) and identified by GC as described earlier (19).

Survival of the introduced A. baumannii strains.

A. baumannii strains S19 and S30 were selected to monitor the survival of the introduced bacterial strains at the bioremediation site. Both strains were resistant to different antibiotics and could be easily distinguished from other constituent bacterial strains in the consortium by colony morphology. To monitor the survival of introduced bacterial strains at the bioremediation site, soil samples were collected before and immediately after the application of bacterial consortium in plots A and B. Soil samples were also collected at the end of study from these plots. Similarly, soil samples were also collected from plot C at time zero and after completion of the study. Soil samples (1 g) from all three plots were suspended in saline water (0.85% NaCl). The suspensions, after appropriate dilution, were plated onto LA containing spectinomycin and ampicillin (50 μg/ml each) in one set of petri plates to estimate the population of A. baumannii S19. Similarly, the suspension was plated onto LA plates containing 20 μg of vancomycin/ml and 50 μg of ampicillin/ml to estimate the population of A. baumannii S30. One hundred bacterial colonies from soil samples of plots A and B were picked randomly from selective LA plates at a 105 dilution. However, bacterial colonies did not grow from the soil samples of plot C when samples were plated onto selective LA plates (one set of LA plates containing 20 μg of vancomycin and 50 μg of ampicillin/ml and another set of LA plates containing spectinomycin and ampicillin at 50 μg/ml each). Therefore, 100 colonies from plot C were picked randomly from nonselective (without antibiotic) LA plates for analysis of DNA fingerprints. These colonies were subjected to enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus PCR (ERIC-PCR) to obtain DNA fingerprints. At time zero, the number of colonies picked for ERIC-PCR represented more than 58% of the total number of colonies, and after 1 year it represented more than 82% of the total number of colonies. The primers ERIC-1R (5′-ATG TAA GCT CCT GGG GAT TCA C-3′) and ERIC-2 (5′-AAG TAA GTG ACT GGG GTG AGC G-3′) were obtained from Life Technologies. Single isolated colonies were picked at random from the selective LA plates, suspended in 50 μl of water, and lysed by heating for 10 min at 95°C. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and 4°C for 5 min, and 2 μl of the supernatant was used in the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture (15 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin (wt/vol), 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μM concentrations each of primers ERIC-1R and ERIC-2, and 0.45 U of Taq polymerase (Life Technologies). The mixture was overlaid with 20 μl of mineral oil, and amplification was done on DNA engine PTC-200 (MJ Research). The amplification protocol included initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles at 92°C for 30 s, 50°C for 1 min 20 s, and 68°C for 3 min 20 s. The final extension was done at 68°C for 8 min. The reaction was terminated using loading dye (1 μl) containing 15% Ficoll, 0.25% bromophenol blue, and 0.25% xylene cyanol. Each PCR product was resolved by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. The fingerprints of unknown bacterial isolates thus obtained were compared with the fingerprints of A. baumannii strains S19 and S30 obtained under similar reaction conditions to confirm the survival of the strains at the contaminated site.

RESULTS

Feasibility study.

Of the six treatments employed for the feasibility study, the addition of the bacterial consortium and nutrients resulted in the maximum bioremediation response. The concentration of TPH was reduced from 91.8 ± 9.2 g/kg of soil to 47.2 ± 5.4 g/kg of soil in 120 days, which was equivalent to a 48.5% loss of TPH, compared to only a 17% reduction of TPH in the plots treated with nutrients alone. However, the reduction of TPH in plots treated with A. baumannii S30 and B. cepacia was 35.7%, while the reduction of TPH in plots treated with A. baumannii S30, B. cepacia, and nutrients was 38.1% in 120 days. Based on the above result, the treatment consisting of the selected bacterial consortium and nutrients was chosen for the full-scale bioremediation study.

Characterization of soil at the bioremediation site.

The soil at the full-scale bioremediation site was black due to heavy contamination and bereft of any vegetation. Physical and chemical properties of soil of bioremediation site are shown in Table 1. Bulk density of the soil at the bioremediation site remained unchanged. The water-holding capacity of the soil increased significantly during the bioremediation, whereas there was a decrease in the organic carbon in soil. The pH of the soil did not vary much during the study. The chemical composition of oily sludge collected at time zero from bioremediation site is shown in Table 2. The chemical composition of oily sludge showed the highest content of organic matter, which was followed by sediments and ash. The solvent-extractable TPH content in oily sludge was 18% (Table 2). Among the four fractions of TPH, (alkane, aromatic, NSO, and asphaltene), the one present in the highest proportion was the alkane fraction and the lowest was the NSO fraction (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Physical and chemical properties of soil of bioremediation site

| Property | Meana ± SD at:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Time zero | 360 days | |

| Bulk density (g/cm3) | 1.3 ± 0.12 | 1.35 ± 0.10 |

| Water-holding capacity (%) | 59 ± 4 | 71 ± 3 |

| pH | 7.4 ± 0.20 | 7.6 ± 0.10 |

| Organic carbon (%) | 3.2 ± 0.15 | 2.6 ± 0.16 |

| Total nitrogen (%) | 0.046 ± 0.02 | 1.15 ± 0.03 |

| Potassium (mg/kg) | 130 ± 8 | 115 ± 5 |

| Available phosphorus (mg/kg) | 12 ± 0.50 | 27 ± 0.40 |

Mean of 20 mixed soil samples of plots A and B. All soils were loams at both time points.

TABLE 2.

Composition of oily sludge collected from the bioremediation site

| Constituent | Composition (% [wt/wt])a |

|---|---|

| Oily sludge | |

| Solvent-extractable TPH | 18 ± 2 |

| Water | 6 ± 0.50 |

| Organic matter | 41 ± 0.80 |

| Sediments and ash | 35 ± 0.62 |

| TPH | |

| Alkane fraction | 52 ± 4 |

| Aromatic fraction | 31 ± 1 |

| NSO fraction | 7 ± 0.50 |

| Asphaltene fraction | 10 ± 0.80 |

Mean ± standard deviation for 20 samples.

A total of 13 heavy metals were analyzed in oily sludge and mixed soil samples (composite soil samples of plots A, B, and C) collected from the bioremediation site (Table 3). In the oily sludge, nine heavy metals were detected. Among these metals, Al (aluminum), Mn (manganese), and Fe (iron) had high concentrations. Similarly, in the soil with a 25-cm horizon, seven heavy metals were detected at time zero and after 1 year of bioremediation (Table 3). In soil with a 50-cm horizon, seven heavy metals were detected at time zero and eight heavy metals were detected at the end of the study. However, the concentrations of these heavy metals in the oily sludge and in the soil were much lower according to standards, and these concentrations were not toxic to most soil bacteria. The seepage of heavy metals in the soil of the bioremediation site was also monitored (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Concentrations of selected heavy metals in oily sludge and soil of bioremediation site

| Heavy metal | Concn (mg/kg)a in:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oily sludge | Soil at time zero

|

Soil at 360 days

|

|||

| 25 cm | 50 cm | 25 cm | 50 cm | ||

| Al | 78.6 ± 6.10 | 6.71 ± 0.09 | 53.1 ± 2.50 | 13.3 ± 1.20 | 1.35 ± 0.02 |

| Si | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.72 ± 0.01 |

| Zn | 0.60 ± 0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Mn | 2.51 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 1.35 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| Cu | 0.03 ± 0.00 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Co | 0.0005 ± 0.00 | 0.002 ± 0.00 | 0.006 ± 0.00 | 0.003 ± 0.00 | 0.002 ± 0.00 |

| Fe | 39.6 ± 1.20 | 10.6 ± 0.92 | 34.9 ± 0.85 | 18.3 ± 1.10 | 1.14 ± 0.01 |

| Cd | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.01 |

| Pb | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Cr | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 0.002 ± 0.00 | 0.009 ± 0.00 | 0.004 ± 0.00 | 0.002 ± 0.00 |

| Ni | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| As | 0.003 ± 0.00 | 0.001 ± 0.00 | 0.007 ± 0.00 | 0.003 ± 0.00 | ND |

| Se | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

Values are means ± standard deviations for 20 samples. ND, not detected.

In situ degradation of TPH.

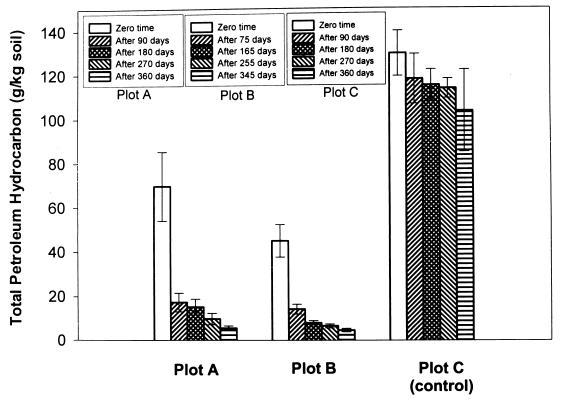

The levels of TPH contamination in soil of plot A at different time periods during the course of the study are shown in Fig. 1. At time zero (just before initiation of bioremediation), the concentration of oily sludge (TPH) in the soil (25-cm horizon) of plot A was 69.7 g/kg of soil. After 360 days, it was reduced to 5.53 g/kg of soil, indicating a removal of 92.0% of TPH (Fig. 1). The removal of various fractions of TPH is shown in Table 4. In plot A, a total of 94.2% of alkane, 91.9% of aromatic, and 85.2% of NSO and asphaltene fractions were removed in 1 year. At time zero in plot B, the concentration of TPH in soil with a 25-cm horizon was 45.1 g/kg of soil, which was reduced to 4.62 g/kg in 345 days, showing a total removal of 89.7% (Fig. 1). The reduction of the individual fractions is summarized in Table 4. In plot B, a total of 95.1% of the alkane fraction, 94.8% of the aromatic fraction, and 63.5% of the NSO and asphaltene fractions was removed in 1 year.

FIG. 1.

TPH in soil of plots A, B, and C. Soil samples from a 25-cm horizon (0- to 25-cm depth) were collected from treatment plots A, B, and C at time zero and at regular intervals. TPH from 10 g of soil samples were extracted using solvents. Values are means for 36 samples in plots A and B and means for 12 samples in plot C. Bars represent standard deviations.

TABLE 4.

TPH contamination in the soil and removal of various fractions of TPH from different horizons of soil during bioremediation

| Plot | Mean valuea ± SD at soil depth

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 cm

|

50 cm

|

|||||||||||

| TPH in soil

|

Removal from soil in 360 days

|

TPH in soil

|

Removal from soil in 360 days

|

|||||||||

| Time zero | 360 days | TPH | Alkane fraction | Aromatic fraction | NSO and asphaltene fractions | Time zero | 360 days | TPH | Alkane fraction | Aromatic fraction | NSO and asphaltene fractions | |

| A | 69.7 ± 15.7 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | 64.2 ± 7.4 | 34.2 ± 2.6 | 19.9 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 0.9 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| B | 45.0 ± 7.3 | 4.6 ± 0.7b | 40.4 ± 3.4b | 22.3 ± 1.6b | 13.2 ± 0.8b | 4.9 ± 0.9b | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0b | 0.0 ± 0.0b | 0.0 ± 0.0b | 0.0 ± 0.0b | 0.0 ± 0.0b |

| C | 132.0 ± 10.1 | 113.5 ± 18.4 | 18.5 ± 6.1 | 11.9 ± 4.3 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

Means for 36 samples in plots A and B and for 12 samples in plot C. Values are in grams per kilogram of soil. TPH could not be detected at 75 or 100 cm.

Value obtained after 345 days.

Similarly, in the control plot (plot C), the TPH concentration in soil with a 25-cm horizon was reduced from 132 to 113.5 g/kg of soil in 1 year, indicating a loss of only 14.0% (Fig. 1). The disappearance of individual fractions of TPH is summarized in Table 4. A total of 17.3% of the alkane fraction, 12.9% of the aromatic fraction, and 5.8% of the NSO and asphaltene fractions were removed in 1 year. However, the removal of TPH in soil from a 50-cm horizon of all three plots could not be detected even after 1 year, although the level of TPH contamination in this horizon of soil was much lower than that of the 25-cm-horizon soil (Table 4). The TPH could not be detected at time zero or after 360 days in soil collected from 50-to-∼75-cm and 75-to-∼100-cm depths in all the treatment plots, indicating no seepage of TPH in soil

Survival of introduced A. baumannii at the bioremediation site.

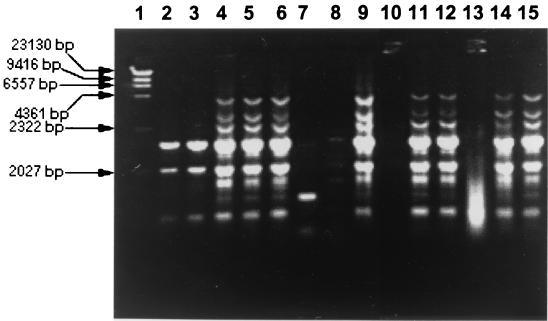

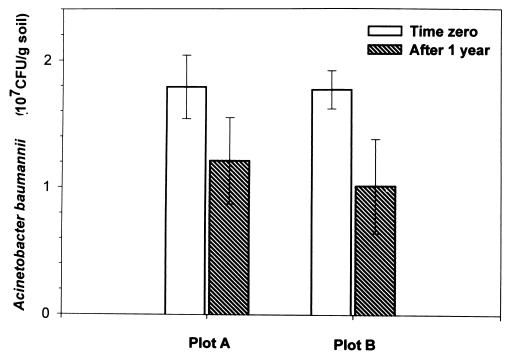

Selection on antibiotic plates followed by ERIC-PCR-based DNA fingerprinting was used to study the survival of A. baumannii S19 and S30. The selection of A. baumannii S19 was done on LA plates containing spectinomycin and ampicillin (50 μg/ml each), and selection of A. baumannii S30 was done on LA plates containing vancomycin (20 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml). Further selection of A baumannii was done by DNA fingerprinting, although A. baumannii could not be distinguished further into strains S19 and S30 based on DNA fingerprinting. DNA fingerprints of unknown bacterial isolates from plot A and plot B obtained on LA plates containing spectinomycin and ampicillin (50 μg/ml each) exactly matched that of A. baumannii S19 (Fig. 2). Similarly, DNA fingerprints of unknown isolates obtained on LA plates containing 20 μg of vancomycin and 50 μg of ampicillin/ml from plot A and plot B exactly matched that of A. baumannii S30 (Fig. 2). In contrast, DNA fingerprints of unknown isolates obtained on nonselective LA plates from plot C did not match A. baumannii S19 and S30 (Fig. 2). The populations of A. baumannii strains S19 and S30 in soil of plot A (obtained on selective LA plates) at time zero and after 1 year were 1.79 × 107 and 1.21 × 107 CFU/g of soil, respectively. Similarly, populations of A. baumannii S19 and S30 were 1.77 × 107 CFU/g of soil at time zero and 1.01 × 107 CFU/g of soil after 345 days of application of the bacterial consortium in plot B, indicating a very high survival of the introduced strains (Fig. 3). A. baumannii S19 and S30 could not be detected on selective plates from plots A, B, and C at time zero. The indigenous populations of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria (estimated on minimal salt medium plates with crude oil as the sole carbon source) in plot C were 3 × 104 and 2 × 104 CFU/g of soil at time zero and after 1 year, respectively. However, among these indigenous populations A. baumannii strains S19 and S30 were not detected.

FIG. 2.

Genomic DNA fingerprints of unknown representative bacterial isolates. Lanes: 1, λ HindIII digest; 2, 3, 7, 8, 10, and 13, fingerprints of unknown isolates obtained on nonselective LA plates from plot C; 4, 5, and 6, fingerprints of unknown isolates obtained on selective LA plates from plot A; 9, 11, and 12, fingerprints of unknown isolates obtained on selective LA plates from plot B; 14, fingerprint of A. baumannii S30; 15, fingerprint of A. baumannii S19.

FIG. 3.

Population of A. baumannii in soil of plots A and B. The soil samples obtained from plots A and B were suspended in saline water (0.85% NaCl) and dilution plated onto selective LA plates to obtain the bacterial count. Colonies from these plates were randomly picked and subjected to ERIC-PCR for confirmation of A. baumannii strains. Values are means ± standard deviations for six replicates.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present investigation was to evaluate inoculum addition to stimulate in situ bioremediation of oily-sludge-contaminated soil where the indigenous population of hydrocarbon-degrading bacteria was low. In the present study, microbial inoculation for removal of TPH achieved better results than those in previously published studies by Venosa et al. (29, 30), who showed that microbial inoculation did not enhance the removal of TPH from soil contaminated with crude oil. A feasibility study at the site prior to the full-scale study showed that the introduced bacterial consortium effectively adapted to the local environment of the soil at the bioremediation site. This finding suggests that environmental factors play a vital role in the bioremediation of soil contaminated with oily sludge. Dibble and Bartha (9) also reported that environmental parameters play an important role in biodegradation of oily sludge by soil bacteria. In the present study, the initial indigenous population of oily-sludge-degrading bacteria was found to be 103 to 104 CFU/g of soil (plots A, B, and C) before addition of the bacterial consortium to the contaminated soil. This level of indigenous population is inadequate for bioremediation; therefore, additional inoculum was added. In a previous study, it was reported that when the population of indigenous microorganisms capable of degrading the target contaminant is less than 105 CFU/g of soil, bioremediation will not occur at a significant rate (12). Addition of nutrients, mineral fertilizers, different agricultural by-products, and molasses along with bacterial inoculation has been reported to enhance the degradation process (1, 7, 22). In the present study, the bacterial consortium was applied in the form of carrier-based inocula. The carrier material used for the purpose is an agricultural residue, corncob powder, which is a very good soil conditioner. The carrier material may also have augmented the degradation rate by providing air pockets in the soil, thereby making it porous and facilitating aeration for growth and survival of the introduced bacterial consortium.

Biodegradation of oily sludge.

Contamination of soil with oily sludge poses a threat to habitat and renders the soil unfit for use. Treatment of such land has been a common practice in oil refineries and yields good results. The treatment is carried out by enriching specific populations from the soil and by applying them back to the contaminated soil, where the population of oil-degrading microorganisms is low (12). In the present study, the disappearance of TPH from treated plots was much higher than that in the untreated plot. This observation is in agreement with those of Barbeau et al. (3), who reported that bioaugmentation of pentachlorophenol (PCP) contaminated soil by PCP-degrading microorganisms resulted in a 99% reduction of PCP concentration. It was also observed that disappearance of TPH from treated plots was faster during the first 3 months of inoculation and slowed down later. This might be because the alkane fraction, which constitutes 50 to 60% of TPH, was removed in the first 3 months after inoculation. The aromatic and the asphaltene fractions were removed at a later phase and at a lower rate. In the control plot, the degradation was much slower than in the treated plots. This shows that the indigenous population in the control plot was not adequate to stimulate degradation of the oily sludge. Bioaugmentation thus enhanced the process of bioremediation. In addition, no significant seepage of the oily sludge occurred. No TPH was detected at time zero or after 360 days beyond a depth of 50 cm when samples collected from 50 to 75 cm and 75 to 100 cm were analyzed.

Survival of A. baumannii.

Survival of A. baumannii, which was a constituent of the introduced bacterial consortium, was tracked by selection on selective LA plates followed by ERIC-PCR-based DNA fingerprinting. Both the introduced strains (S19 and S30) of Acinetobacter were found to be stable even after 1 year at the bioremediation site. This might be due to the maintenance of suitable soil conditions, including moisture level, nutrients, and aeration. Thus, the high rate of bioremediation observed during the study was in fact due to the survival of the selected bacterial consortium under field conditions (3, 11).

Soil parameters.

Such parameters as the soil type, carbon content, nitrogen and phosphorus content, moisture level, and water-holding capacity also play a major role during bioremediation. Organic carbon in soil was reduced from 3.2 to 2.6% at the end of the study, which indicates that the TPH content of the oily sludge had been lowered (7). A marked increase in the water-holding capacity of the soil at the end of the study can be attributed to the substantial reduction of oil content in the soil due to degradation. Before application of the selected bacterial consortium, the site was bereft of vegetation. This could be due to a lower water-holding capacity of the soil because of the presence of the oily sludge in the surface soil (25-cm horizon), perhaps preventing seedlings of grasses, etc., from surviving. However, 3 months after the inoculation, some plant growth with visible vegetation was observed, which coincided with an increase in the water-holding capacity of the soil. A change in the C:N ratio at the end of the study also suggests increased bacterial activity. Our results show that the concentration of heavy metals in oily sludge was much higher than in soil at time zero. At the end of the study the concentrations of heavy metals in surface soil (25-cm horizon) increased due to addition of heavy metals in the surface soil from the oily sludge after biodegradation of TPH. However, the concentration of heavy metals in 50-cm-horizon soil decreased at the end of the study. It could be that heavy metals which were present at time zero in 50-cm-horizon soil leached down over the year and and that further addition of heavy metals in 50-cm-horizon soil from oily sludge could not occur after degradation of TPH, as oily-sludge contamination in this zone was much lower than in the surface soil (25-cm horizon).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to R. K. Pachauri, Director, TERI, for providing the infrastructure to carry out the present study. Thanks are in order to the management at the Mathura refinery, where the study was carried out. Fine technical assistance by Vinod Kumar is appreciated. We thank Yateen Joshi for editing and G. Gopalakrishnan for typing the manuscript.

We thank the Government of India Department of Biotechnology for partial funding of this research and Council of Scientific and Industrial Research for providing fellowship to one of us during the work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Hadhrami H, Lappin-Scott M, Fisher P J. Studies on the biodegradation of three groups of pure n-alkanes in the presence of molasses and mineral fertilizer by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mar Pollut Bull. 1997;11:969–974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bajpai U, Kuhad R C, Khanna S. Mineralization of [14C]octadecane by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus S19. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbeau C, Deschenes L, Karamanev D, Comeau Y, Samson R. Bioremediation of pentachlorophenol-contaminated soil by bioaugmentation using activated soil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:745–752. doi: 10.1007/s002530051127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartha R. Biotechnology of petroleum pollutant biodegradation. Microb Ecol. 1986;12:155–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02153231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bossert I, Bartha R. The fate of petroleum in the soil ecosystems. In: Atlas R M, editor. Petroleum microbiology. New York, N.Y: Macmillan; 1984. pp. 435–473. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bragg J R, Prince R C, Wilkinson J B, Atlas R M. Effectiveness of bioremediation for the Exxon Valdez oil spill. Nature. 1994;368:413–418. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvo-Ortega J J, Lahlou M, Siaz-Jimenez C. Effect of the organic matter and clays on the biodegradation of phenanthrene in soils. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1997;40:101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho B-H, Chino H, Tsuji H, Kunito T, Nagaoka K, Otsuka S, Yamashita K, Matsumoto S, Oyaizu H. Laboratory-scale bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil of Kuwait with soil amendment materials. Chemosphere. 1997;35:1599–1611. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(97)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dibble J T, Bartha R. The effect of environmental parameters on the biodegradation of oily sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:729–739. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.4.729-739.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.di Giovanni G D, Watrud L S, Seidler R J, Widmer F. Comparison of parental and transgenic alfalfa rhizosphere bacterial communities using Biolog GN metabolic fingerprinting and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence-PCR (ERIC-PCR) Microbiol Ecol. 1999;37:129–139. doi: 10.1007/s002489900137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eriksson M, Dalhammar G, Borg-Karlson A-K. Aerobic degradation of a hydrocarbon mixture in natural uncontaminated potting soil by indigenous microorganisms at 20°C and 6°C. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;51:532–535. doi: 10.1007/s002530051429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsyth J V, Tsao Y M, Bleam R D. Bioremediation: when is bioaugmentation needed? In: Hinchee R E, Fredrickson J, Alleman B C, editors. Bioaugmentation for site remediation. Columbus, Ohio: Battelle Press; 1995. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo C, Sun W, Harsh J B, Ogram A. Hybridization analysis of microbial DNA from fuel oil-contaminated and noncontaminated soil. Microbiol Ecol. 1997;34:178–187. doi: 10.1007/s002489900047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson K G, Nigam A, Kapadia M, Desai A J. Bioremediation of crude oil contamination with Acinetobacter sp. A3. Curr Microbiol. 1997;35:191–193. doi: 10.1007/s002849900237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huertas M-J, Duque E, Marques S, Ramos J L. Survival in soil of different toluene-degrading Pseudomonas strains after solvent shock. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:38–42. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.38-42.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson M H. Soil chemical analysis. New Delhi, India: Prentice-Hall of India (Pvt. Ltd.); 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korda A, Santas P, Tenete A, Santas R. Petroleum hydrocarbon bioremediation: sampling and analytical techniques, in situ treatments and commercial microorganisms currently used. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:677–686. doi: 10.1007/s002530051115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lal B, Khanna S. Mineralization of [14C]octacosane by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus S30. Can J Microbiol. 1996;42:1225–1231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lal B, Khanna S. Degradation of crude oil by Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Alcaligenes odorans. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996b;81:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loser C, Seidel H, Zehnsdarf A, Stoltmeister U. Microbial degradation of hydrocarbons in soil during aerobic/anaerobic changes and under purely aerobic conditions. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:631–636. [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacNaughton S J, Stephen J R, Venosa A D, Davis G A, Chang Y J, White D C. Microbial population changes during bioremediation of an experimental oil spill. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3566-3574.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olivera N L, Esteves J L, Commendatore M G. Alkane biodegradation by a microbial community from contaminated sediments in Patagonia, Argentina. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1997;40:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pometto A L, Oulman C S, Dispirito A A, Johnson K E, Baranow S. Potential of agricultural by-products in the bioremediation of fuel spills. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;20:369–372. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Propst T L, Lochmiller R L, Qualls C W, Jr, McBee K. In situ (mesocosm) assessment of immunotoxicity risks to small mammals inhabiting petrochemical waste sites. Chemosphere. 1999;38:1049–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos J L, Duque E, Ramos-Gonzalez M I. Survival in soils of an herbicide-resistant Pseudomonas putida strain bearing a recombinant TOL plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:260–266. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.260-266.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sengar C B S, Johnson R, Kumar A, Aggarwal A L. Atomic absorption spectrophotometric determination of trace metals in suspended particulate matter. Indian J Environ Protect. 1990;10:614–618. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song H-G, Wang X, Bartha R. Bioremediation potential of terrestrial fuel spills. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:652–656. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.652-656.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiem S M, Krumme M L, Smith R L, Tiedje J M. Use of molecular tools to evaluate the survival of a microorganism injected into an aquifer. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1059–1067. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1059-1067.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Venosa A D, Haines J R, Allen D M. Efficacy of commercial inocula in enhancing biodegradation of weathered crude oil contaminating a Prince William Sound beach. J Ind Microbiol. 1992;10:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venosa A D, Suidan M T, Haines J R, Wrenn B A, Strohmeir K L, Eberhart Looye B L, Kadkhodayan M, Holder E, King D, Anderson B. Bioremediation of an experimental oil spill on the shoreline of Delaware Bay. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:1764–1775. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski J R. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;24:6823–6831. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.24.6823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weidmann-Al-Ahmad M, Tichy H V, Schon G. Characterization of Acinetobacter type strains and isolates obtained from wastewater treatment plants by PCR fingerprinting. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4066–4071. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4066-4071.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker J D, Colwell R R, Petrakis L. Microbial petroleum degradation: application of computerised mass spectrometry. Can J Microbiol. 1975;21:1760–1767. doi: 10.1139/m75-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolter M, Xadrazil F, Martens R, Bahadir M. Degradation of eight highly condensed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by Pleurotus sp. Florida in solid wheat straw substrate. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:398–404. [Google Scholar]