Abstract

Repeated noise exposure and occupational hearing loss are common health problems across industries and especially within the mining industry. Large mechanized processes, blasting, grinding, drilling, and work that is often in close quarters put many miners at an increased risk of noise overexposure. In stone, sand, and gravel mining, noise is generated from a variety of sources, depending on the type of ore being mined as well as the final consumer product provided by that mine. Depending on the source of noise generation, different strategies to reduce and avoid that noise should be implemented. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has evaluated the noise profile at three operational surface stone, sand, and gravel mines. A-weighted sound level meter data as well as phase array beamforming data were collected throughout the mines in areas with high noise exposure or high personnel foot or vehicle traffic. Sound level meter data collected on a grid pattern was used to develop sound profiles of the working areas. These sound contour maps as well as phase array beamforming plots were provided to the mines as well as guidance to modify work areas or personnel traffic to reduce noise exposure.

Keywords: Hearing conservation, Microphone array, Area noise measurement, Sound contour maps

1. Introduction

Occupational hearing loss is a ubiquitous health problem across the mining industry as well as other industrial sectors. Despite implementation of federal regulations addressing noise levels and time spent working in those levels, occupational noise-induced hearing loss (ONIHL) is one of the most common work-related illnesses in the USA [1]. Hearing loss is a permanent and potentially debilitating physical condition affecting over 11% of the US adult working population [2]. There are approximately 22 million workers in the USA exposed to hazardous levels of noise [3]. Of those, 18% of them have developed hearing impairment [4].

A recent National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) evaluation of over 1 million audiograms indicates that mining has the highest prevalence, 27%, of hearing loss among industries sampled, with the average industry prevalence at 18% [5]. Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) exposure data indicate average noise exposures exceeding MSHA’s permissible exposure level (PEL) across surface and underground coal and non-coal mining sectors. Exceedance values range from approximately 7 to 18% [6], which is greater than that of the general, non-noise-exposed population.

Past NIOSH research has focused on noise exposure and solutions in underground coal and underground and surface metal/non-metal sectors. However, MSHA data show that more reportable cases of occupational hearing loss are found at stone, sand, and gravel (SSG) mines than at non-metal and metal mines. Surface and underground SSG mines show approximately the same incident rate of 2.5 per 10,000; however, surface SSG mines employ nearly 30 times more workers than underground mines [7], thus representing a larger burden for evaluation and solution development. In addition, 84% of SSG companies have 25 or fewer employees, and consequently there is a lack of in-house expertise in conducting or evaluating the effectiveness of hearing conservation programs [7].

Despite sharing of a commodity name, there are some differences among standard SSG operations that affect noise exposure. Depending on the type of ore, method of ore extraction, type of processing, and shipping methods, various noise sources will present and contribute to the overall noise exposure of workers. To investigate this problem, this paper examines the similarities and differences in the noise profile at three SSG facilities that vary based on product type, transportation path from the ore to the product, and the processes and end products specific to that facility.

2. Methodology

The present study focused on various areas of interest at three different collaborating mines. For the purpose of this study, areas of interest are those that host a higher number of operators, or through which there is high operator traffic. Area noise mapping was used as the primary approach during this investigation. Data were collected using a Larson Davis LxT Sound Level Meter on 1 m and 2 m spacing grids, at a height of 1.5 m from the floor in most of the areas of interest. Area noise maps show the sound distribution and levels throughout a given space. This information can be used to modify working arrangements, or, when necessary, modify equipment or other practices to meet regulations.

In addition to area noise mapping, microphone phase array data were acquired in certain areas. The purpose of these measurements was to identify and locate specific noise sources responsible for the high noise levels in those areas. Microphone phased array measurements are widely used in the aeronautics and auto industries to identify dominant noise sources; however, their use in the mining industry has been very limited. This technique takes advantage of the phase difference between the microphones to track back to the location of a noise source over a scanning plane by means of an algorithm known as beamforming.

In its most basic form, beamforming starts with the assumption of a source propagation model, the simplest one being the monopole source given by:

| (1) |

where, as shown in Fig. 1, pn is the acoustic pressure received at time t by the microphone located at xn, s is the signal emitted by the monopole source located at xs, rn is the distance between the source position and the observer position, and c is the speed of sound.

Fig. 1.

Beamforming to a point source

The frequency-domain version of Eq. (1) is given by:

| (2) |

where f is the frequency expressed in Hz, S(f) is the Fourier transform of the signal s(t), and g(x,f) is the free-field Green’s function:

| (3) |

where Δt is the time required for the sound to travel from the source at xb to an observer located at x, and thus also known as the propagation time:

| (4) |

For an array of N-microphones, at each potential source point of interest xb, the following beamforming expression is evaluated [6]:

| (5) |

where P(f) is a vector containing the Fourier transforms of the time series of the acoustic pressure recorded by each of the microphones of the array. The normalized vectors g(x)/∥g(x)∥, also known as the steering vectors, are usually denoted as w(x). The beamform expression b(xb) represents an estimate of the acoustic pressure squared at the array location caused by the source at xb.

To evaluate the performance of a microphone phased array at any particular frequency of interest, a unitary point source is simulated at some desired distance from the array center. Then, using a beamforming algorithm, an acoustic map of this simulated source is computed. This particular acoustic map is also known as the array beam pattern or the array point spread function (psf) [8] and is given by:

| (6) |

When distributed sources are present, a technique can be used to obtain the integrated spectrum over some region of interest [9]. This technique uses the psf of a unitary source at the center of the region of interest as a normalization factor and is given by:

| (7) |

To conduct phased array measurements in the field, two small microphone arrays were used. Figure 2 shows pictures of these two microphone arrays. The array shown in Fig. 2a is commercially available with a diameter of 1 m and is provided with 42 microphones. The array shown in Fig. 2b was designed and built by NIOSH. This array has an outside diameter of 0.5 m, and it is equipped with 31 microphones distributed in a logarithmic spiral pattern.

Fig. 2.

Microphone phased arrays used for this study

3. Results

This section presents the results from the noise studies at the various areas of interest in the three collaborating mines. Most of the results are presented in terms of noise maps, and in some cases, the beamforming maps obtained from the phased array measurements.

3.1. Mine 1

Mine 1 consists of an open pit and a processing plant in which rock is crushed and screened to various sizes. Finally, the various products are bagged and palletized for commercialization. The processing plant uses two bagging methods: an automatic bagging machine for sand and “fine stone” and a manual bagging machine for the larger products such as 1/4″ by 1/8″ stone.

Due to the nature of the processes involved in this mine, there were three areas of interest: (1) the automatic bagging area, (2) the manual bagging area, and (3) the rotary drying area.

3.2. Automatic Bagging Area

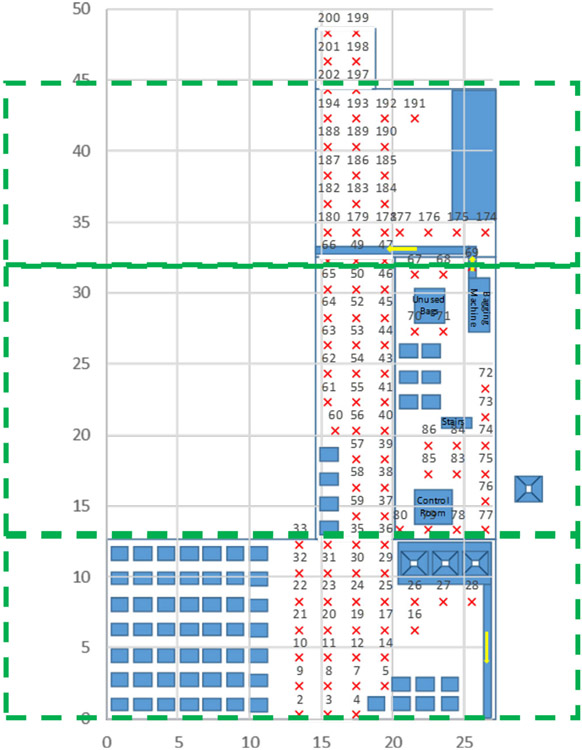

Figure 3 shows the automatic bagging machine in the background with the microphone array in the foreground. Figure 4 shows a schematic top view layout of the building where the automatic bagging machine is installed. This building can be divided into three adjacent areas. Area 1 is located towards the screening building; in this area, bulk bags are temporarily stored in pallets, and there are three inside storage bins (hoppers) for bulk bagging. Area 2 is where the actual automatic bagging machine is located. There is an enclosed control room and a test station in this area. The operator in the enclosed room monitors the rotary dryer as well as the test station. Area 3 has offices, a restroom, and a compressor room. Also in area 3, an overhead conveyor transports the bags from the automatic bagging machine to the palletizing area. These three adjacent areas are of interest because of the high operator traffic.

Fig. 3.

Automatic bagging machine and operator in the background, with the microphone array in the foreground

Fig. 4.

Top view layout of the building where the automatic bagging machine is installed

Figure 5 shows a contour map of overall sound levels in the automatic bagging area. From this figure, it can be seen that the highest levels of sound are located near the automatic bagging machine. Figure 6 shows the acoustic beamforming maps for the automatic bagging machine in operation. From these maps, it can be seen that the automatic bagging machine radiates noise at high frequencies, i.e., above 1250 Hz. However, at low frequencies, i.e., below 1250 Hz, the noise comes from a source adjacent to the automatic bagging machine. In this adjacent area, there is a belt conveyor that transports the bags from the automatic bagging machine to the palletizer. Figure 7 shows the acoustic beamforming maps of an inclined segment of this conveyor. Figure 7c shows a noise source located behind a column on the right-hand side of the picture. In this location, there is a room that houses an air compressor that supplies air to the automatic bagging machine. It is suspected that this compressor is responsible for the low-frequency noise in this area, i.e., less than 1000 Hz.

Fig. 5.

Overall sound pressure level distribution in the automatic bagging building

Fig. 6.

Acoustic beamforming maps showing noise sources in the automatic bagging area

Fig. 7.

Acoustic beamforming maps showing noise sources in the belt conveyor rise going from the automatic bagging machine to the palletizer area

3.3. Manual Bagging Area

Figure 8 shows a picture of the manual bagging area. This area consists of rectangular room 14.5 m long by 9 m wide, adjacent to the storage building. Also shown in Fig. 8 are a ventilation fan mounted on the wall and a belt conveyor that transports material to an upper hopper located above the bagging machine. Figure 9 shows a schematic top view layout of the room where the manual bagging activities occur. Figure 10 shows a contour map of overall sound pressure levels (SPL) in the manual bagging area. From this figure, it can be seen that the highest levels of sound are located near the operator of the manual bagging machine.

Fig. 8.

Manual bagging machine and wall ventilation fan on the top right corner

Fig. 9.

Top view layout of the manual bagging machine room

Fig. 10.

Overall spl distribution on the manual bagging machine room

Figure 11 shows the acoustic beamforming maps for the manual bagging machine in operation. These maps correspond to the one-third octave bands with the highest noise levels. From the acoustic maps, three noise sources can be distinguished: (1) the hopper located above the bagging machine, radiating noise at 630 Hz and at 800 Hz; (2) the ventilation fan radiating noise at 1000 Hz; and (3) the bag filling mechanism radiating noise at frequencies above 1250 Hz.

Fig. 11.

Acoustic maps showing noise sources in the manual bagging area

3.4. Rotary Dryer

The rotary dryer is used to dry large aggregate before it is sent to the manual bagging machine or to the inside storage bins for bulk bagging. Figure 12 shows a picture of the drum inside this room. The room has a 4.5-m-wide door opening as shown in Fig. 13. Noise data collected on this room yielded the map shown in Fig. 14. In addition, some measurements were conducted outside the room next to the opening. From Fig. 14, it can be seen that the highest noise levels are present near the center of the drum at 93 dB(A). However, outside the opening, levels dropped to around 84 dB(A).

Fig. 12.

Rotary dryer

Fig. 13.

Top view layout of the rotary dryer room

Fig. 14.

Overall spl distribution on the rotary dryer room

3.5. Mine 2

Mine 2 is a surface sand mine with a remote surface quarry. The ore is extracted from an open pit, and then conveyed to two processing buildings for crushing and washing procedures. The final product is dried then loaded to trucks and train for final haulage. There is no bagging process at this mine. Sand, primarily used for other industrial processes, is the only consumer product from this mine.

3.6. Processing Building

Figure 15 shows a picture of the rod mill with the microphone array on the left side. As seen in this figure, the mill has a cylindrical geometry with an opening in the front. The sand that is crushed inside the rotating drum exits through the front opening and continues towards the rotary dryer. Figure 16 shows a schematic top view layout of the processing building. Since this is a large area, it has been divided into three sub areas: (1) area A which contains the rod mill, (2) area B which contains the flotation pools and the operator’s control room, and (3) area C which contains a storage room and part of the flotation system. These three adjacent areas are of interest because of the high traffic of operators, not only going to the processing building but to the rotary dryer and the storage and crusher buildings. It should be noted that the measurements collected in these three sub areas were obtained on the second level, which is where most worker traffic occurs. The floor of this second level is made of steel grating, which in terms of sound transmission can be considered acoustically transparent—in other words having no effect on noise generation or radiation through the space.

Fig. 15.

Rod mill used in the processing building, with the microphone array on the left side

Fig. 16.

Top view layout of the processing building

Figure 17 shows contour maps of the sound distribution at each of these three sub areas. From these figures, it can be seen that the highest levels of sound are located near the rod mill and towards the middle of the building in area B.

Fig. 17.

Overall sound pressure level distribution in the sub areas of the processing building

Figure 18 shows the acoustic maps at six different frequencies for the rod mill in operation. From these maps, it can be seen that most of the sound generated inside the rotating drum radiates through the front opening. These maps also show that in terms of frequency content, the sound radiated by the rod mill has a broadband signature between 630 and 2000 Hz, which was the range of the microphone array. Figure 4f also shows a noise source at the 11 o’clock position on the rotating drum. This noise is likely generated by the driving mechanism of the mill’s drum. However, because the levels at this frequency band are much lower that the levels at the low frequency bands, this noise source is not considered dominant and does not provide additional noise hazard to workers in the vicinity.

Fig. 18.

Acoustic maps showing noise sources in the rod mill

Figure 19 shows the acoustic maps of the flotation pools at higher frequencies, i.e., 1600 through 2500 Hz. From this figure, it can be seen that the electric motors of the agitators radiate noise at 2500 Hz. However, the levels are much lower than those radiated by the rod mill, and therefore, these are not considered dominant noise sources and do not provide additional noise hazard to workers in the vicinity.

Fig. 19.

Acoustic maps showing noise sources in the area around the motors and agitators above the flotation pools

3.7. Outside Area

Figure 20 shows a panoramic view of the outside area between the processing building, the rotary dryer, and the storage building. This picture clearly shows the various outside stairs that provide access to each of these buildings.

Fig. 20.

Outside area between the processing building, the rotary dryer, and the storage building

Figure 21 shows a schematic layout of the outside area between the processing building, the rotary dryer, and the storage building. Two frequently used vehicle roads also cross this area. Figure 22 shows the sound distribution in this area. From this figure, it can be seen that the highest levels of noise are present near the stairs that lead to the rotary dryer. The noise source in this location is the burner of the dryer fueled by propane gas. This figure also shows that when the operators go from the processing building to the storage building as they typically travel the area, they cross through high levels of noise.

Fig. 21.

Top view layout of the outside area

Fig. 22.

Overall sound pressure level distribution on the outside area

3.8. Loading Building

The loading building is located away from the conglomerate of buildings that were assessed in this study—i.e., the processing building, the rotary dryer, and the storage/crusher building. The loading operator is located in a control room near the top of the building, as shown in Fig. 23. This facility loads the final product on train cars on one side and on trucks on the other side.

Fig. 23.

Pictures of the loading building and the operator’s control room

There is minimal traffic through this building; typically, only the loading operator is present, who rarely exits from the control room. Therefore, noise measurements were collected in the hallway area outside the control room and inside the control room itself while a truck was being loaded with sand. These measurements revealed that the average sound pressure levels were 61.4 dB(A) and 71.2 dB(A), inside and outside the control room, respectively. These sound levels are considered to be safe for extended exposure; therefore, no further noise measurements were conducted for this structure.

3.9. Mine 3

Mine 3 is an underground limestone quarry with surface processing operations. The ore is dumped by heavy truck into a primary crusher then, via several conveyors and screenings operations, sorted into appropriate sizes before stockpiling. Final consumer products, primarily crushed aggregate for road and other construction, are hauled via truck.

The initial noise study at this mine focused on the primary crushing area, primary conveyor system, and the secondary crusher/processing area around the operator enclosure. These areas show high foot and vehicle traffic and exhibit variable noise based on location and activity. It is recognized that high sound levels are likely found near the stockpiles; however, primarily vehicle traffic traverses this area, and windows or cabs can be used to reduce the noise exposure of drivers.

3.10. Main Conveyor

Figure 24 shows pictures of the main conveyor. This conveyor, approximately 150 m (490 ft) long, transports material from the primary crusher to a screening tower. On the left side of this conveyor, a road has operator traffic. For this reason, this road alongside of the conveyor is of interest to this study.

Fig. 24.

Pictures of the main conveyor viewed from a the ground level and b from the primary crusher

Figure 25 shows the sound distribution along the main conveyor. From this figure, high levels of noise can be seen near both ends of the conveyor, especially near the primary crusher end. Figure 26 shows the acoustic maps for each octave frequency band. It can be observed that higher levels of noise are radiated at the low frequencies, especially 8 Hz and 63 Hz. These maps also show that most of the sound is radiated below 500 Hz.

Fig. 25.

Acoustic map showing the sound distribution along the main conveyor

Fig. 26.

Octave-band acoustic map showing the sound distribution along the main conveyor

3.11. Outside Area near the Primary Crusher

The second place of interest is the outside area near the dumping chute of the primary crusher. There is a walkway between a small storage building and the control room of the crusher as shown in Fig. 27. Sound level measurements in this walkway were collected and the acoustic maps were obtained.

Fig. 27.

Outside area near the control room of the primary crusher

Figure 28 shows the results in terms of the overall sound distribution in this area. As expected, higher levels of noise are present near the primary crusher’s dumping chute shown on the right side of the figure. Especially on a narrow walkway with stairs, this leads to the operator’s control booth. Acoustic measurements were also conducted inside this booth, and they showed a 74.3-dB level.

Fig. 28.

Acoustic map showing the sound distribution in the outside area near the primary crusher

3.12. Lower Crusher/Processing Area

The third place of interest is an outside area in the lower processing plant. There is an area with operator traffic located between a crusher/screening structure shown in Fig. 29 and an office building with the operator’s control booth located on the second floor.

Fig. 29.

Outside area in the lower processing plant near crusher/screening structure

Figure 30 shows the results in terms of the overall sound distribution in this outside area. It can be seen that sound levels in excess of 94 dB are present between the crusher/screen structure and the operator’s control room. While collecting data, it was noticed that skid steers pass frequently through this area. Further acoustic measurements were collected inside the operator’s control room. An overall 70.4-dB level was measured inside the control room.

Fig. 30.

Acoustic map showing the sound distribution in the outside area between the crusher/screen structure and the operator’s control room

4. Discussion and Comparisons

Unlike underground coal mines, which have very similar layouts and processes, surface stone, sand and gravel mines vary significantly in size, configuration, and layout based on the end products and the processes required to produce these end products. For example, bagging is one of the most important processes in Mine 1. However, Mine 2 and Mine 3 do not have this process at all. Another example is the rotary dryer, which is an important part of the process in Mine 1 and Mine 2 but is completely absent in Mine 3. These differences show that different mines have different areas of high noise exposure based on their processes and end products.

Another difference is that some mines have most of their processes inside buildings—i.e., indoors, like Mine 1 and Mine 2; however, other mines like Mine 3 have most of their processes outdoors. This difference has important implications in terms of acoustics. Outdoor environments closely resemble free field acoustic environments, and the only acoustic reflections are those coming from the ground. In these environments, source directivity and the distance to the noise source play an important role. However, indoor processing buildings resemble reverberant acoustic environments where there is a direct and a diffuse field. In these environments, depending on the geometry, dimensions, and the acoustic properties of the enclosing walls, the diffuse field could be as important as the direct field.

Of the various areas of interest surveyed in Mine 1, the automatic and manual bagging areas have the highest worker traffic. During a normal shift, there are two operators for the automatic bagging machine and the palletizer. These operators switch positions approximately every 4 h. There is also one operator at the control room shown in Area 2. This operator monitors the rotary dryer drum and obtains three to four samples per day in the shaker test station. Finally, three forklift operators move the pallets in and out of this area. There are usually six workers who acquire their noise dose from the automatic bagging area.

At the manual bagging area, there are usually two, and on occasion, up to three operators—one operator at the bagging machine, one at the end of the conveyor belt stocking and palletizing the bags, and a third moving the pallet to the wrapping machine and then to the storage building. These operators usually switch positions every 2 h. Therefore, there are up to three workers that accumulate their daily noise dose in the manual bagging area.

In contrast to the two bagging areas where up to nine operators accumulate their daily noise dose, the screening building has the least traffic of workers. There is only one operator that monitors the screen building operation and conducts periodic checks. During a normal day, this operator usually conducts three visits to the screening building; two out of the three visits, the operator performs cleaning of the screens for 30 to 45 min on each visit.

One of the main observations in Mine 2 was related to the traffic of operators through the area with the highest noise levels. It was noted that workers often take the stairs near the office end of the processing building to the second floor, walk past the rod mill, across the second floor, and then exit near the rotary dryer to descend another flight of stairs. This path is shown schematically in Fig. 31. This path is taken to access the buildings and activities on the far side of the processing building, away from the mine office. It is presumed that this path is chosen for convenience to avoid going through the outside area where water is continuously being discharged. By taking this path, workers walk very near the noise produced by the operating rod mill and again by the rotary dryer.

Fig. 31.

Worker traffic path through the processing building

The outside area between the processing plant, the warehouse, and the rotary dryer was also of interest for Mine 2. Many workers passed through this area to enter the buildings, and vehicle traffic regularly passed through to access the crushing building located behind the warehouse. Given the high noise emitted by the rotary dryer, as well as noise exiting through the openings in the processing building, extended time near this crossroads can easily lead to noise exposure in exceedance of the MSHA PEL.

In Mine 3, during the data collection alongside the main conveyor, two different noise sources were noticed: (1) Tail roller noise, especially near the primary crusher, and (2) impacts between the rollers and the conveyor clips. Tail roller noise is likely due to a malfunctioning or unlubricated roller. Further microphone phased array measurements would help pinpoint exactly which rollers are radiating most of the noise. High noise areas were located near both crushers/processing areas. Operator control booths with safe sound levels were also present at these areas. It was noted that the operators were inside these booths during all crushing/screening activities. These areas can be considered safe in terms of noise exposure for extended working hours.

Finally, even though the focus of this study was noise exposure, the presence of low-frequency noise and vibration were noticed in Mine 3. As shown in Fig. 26a, the highest levels of noise were measured at 8 Hz. Vibrations at such low frequencies could have a direct effect on the operator’s whole-body vibration. The solution in this particular case would be to mount the operator’s booth directly on the ground, as opposed to the crusher structure from where all the vibration is being transmitted.

4.1. Recommendations

Overall, good practices were found in place regarding signage and use of personal protective equipment (PPE) at all three collaborating mines. In Mine 1 and Mine 2, which have various indoor processes, it was noted that several doors had proper signage indicating the need for hearing protection. Also in Mine 1, a PPE vending machine was observed near the changing room. This vending machine requires the worker’s employee identification number to dispense appropriate protection. These are all very positive attributes that can improve the hearing health outcomes of the workers.

Based on the results of the noise studies presented in this paper, several steps can be taken by the mine workers and operators to reduce the noise exposure of workers in the high noise areas. Some of these steps include:

Avoid standing or traversing through the areas indicated in darker colors on the acoustic maps. These areas indicate the highest levels of noise. When job tasks require it, use appropriate hearing protection.

Avoid working or traversing through areas with dominant noise sources such as the rotary dryer, the bagging machine, or the rod mill, except when necessary. Consider installation of outside walkways so that workers can walk around the outside of the processing buildings despite the presence of external obstacles such as flowing water. This will also reduce the instances of ascending and descending potentially slippery stairways. Remediation would improve the noise exposure and potential falling hazards for employees who currently use this route.

Do not stand or conduct work near fans or conveyor belts, if that work can feasibly be moved to a quieter location.

Do not convene or take breaks in high noise outside areas, such as that found in Mine 2 near the rotary dryer. Instead, use areas with lower noise levels for breaks or to convene for conversation.

Consider the implementation of acoustic enclosures for dominant noise sources where feasible. One example of this noise control approach is for the near side of the rotary dryer operation (near the processing building). As can be seen from Fig. 22, overall lower sound levels were found on the backside of the dryer, which was partially enclosed. Another partial enclosure near the stairwell or on the front side that is made of correct acoustic material will further reduce the sound level reaching workers in the area.

Operators of small machinery such as skid steers and forklifts should use all noise controls available on the machines. Windows and cabs should be closed.

Mount control booths for operators directly on the ground, and if necessary using vibration isolators. This will avoid transmission of low-frequency vibrations into the booths, which could also have implications on the operator’s whole-body vibration.

Overall recommendations are to follow the hierarchy of controls to reduce exposure to hazardous noise and subsequent occupational hearing loss. The hierarchy of controls involves first removing or replacing the noise hazards with quieter alternatives. Next, engineering controls should be used to either isolate workers from the noise hazard or reduce the level of noise emitted. Then, administrative controls to modify the way people work in noise or the time spent in noise should be implemented. The last step which should be taken when the previous steps do not fully protect the worker from noise is to rely on hearing protection, to reduce the worker’s personal noise exposure.

4.2. Study Limitations

One potential limitation of this study is that the data was from only three participating mines. A variety of noise sources and mine/plant layouts were represented. However, there may be other examples that do not conform to those discussed within the paper. The authors believe that despite the limited sample size, the examples and recommendations can be applied to a large majority of working areas at mine surface facilities and other industrial work sites. Another overall limitation of the study is the ability for workers to fully implement some of the recommendations. For example, there are likely instances where an alternate path does not exist, and workers are forced to traverse through noise hazardous areas multiple times during a shift. Similarly, budgetary constraints or existing infrastructure may prevent the modification or addition of technology (enclosures, quieter machinery, moving work stations, etc.) to reduce worker noise exposure.

5. Conclusion

An initial noise assessment was conducted in three different surface stone, sand, and gravel facilities. These assessments involved area noise sampling and in some cases noise source identification using microphone array measurements. As a result, noise maps were obtained for all the areas of interest. These maps show the distribution of noise throughout each particular area of interest. Several differences but also some similarities were found during the course of this study among the collaborating mines. Based on the results from the noise assessments, some recommendations were suggested that would help reduce the exposure of miners to noise at these mines. This study is part of a broader project that aims to identify and improve the effectiveness of certain hearing conservation program elements for overall improvement of hearing loss prevention efforts in the SSG sector.

Footnotes

This is a U.S. government work and its text is not subject to copyright protection in the United States; however, its text may be subject to foreign copyright protection 2020

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mention of company names or products does not constitute endorsement by NIOSH.

References

- 1.NIOSH (2016) Noise and Hearing Loss Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/noise/. Accessed 12 Dec 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tak S, Calvert G (2008) Hearing difficulty attributable to employment by industry and occupation: an analysis of the National Health Interview Survey–United States, 1997 to 2003. J Occup Environ Med 50:46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tak S, Davis R, Calvert G (2009) Exposure to hazardous workplace noise and use of hearing protection devices among us workers-NHANES, 1999-2004. Am J Ind Med 52(5):358–371. 10.1002/ajim.20690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masterson E et al. (2013) Prevalence of hearing loss in the United States by industry. Am J Ind Med 56(6):670–681. 10.1002/ajim.22082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masterson E, Deddens JA, Themann CL, Bertke S, Calvert GM (2015) Trends in worker hearing loss by industry sector, 1981-2010. Am J Ind Med 58(4):392–401. 10.1002/ajim.22429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts B, Sun K, Neitzel R (2017) What can 35 years and over 700, 000measurements tell us about noise exposure in the mining industry? Int J Audiol 56(suppl 1):4–12. 10.1080/14992027.2016.1255358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun K, Azman AS (2018) Evaluating hearing loss risks in the mining industry through MSHA citations. J Occup Environ Hyg 15(3):246–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller TJ (ed) (2002) Beamforming in acoustic testing. In: Aeroacoustic Measurements Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravetta PA, (2005) LORE approach for phased Array measurements and noise control of landing gears. Dissertation, Virginia Tech, etd-12072005-113549 [Google Scholar]