Abstract

Introduction

One-third of adults in the United States who use tobacco regularly use two or more types of tobacco products. As the use of e-cigarettes and other noncombusted tobacco products increases—making multiple tobacco product (MTP) use increasingly common—it is essential to evaluate the complex factors that affect product use.

Aims and Methods

In this update to our 2019 conceptual framework, we review and evaluate recent literature and expand the model to include ways in which MTP use may be affected by market factors such as the introduction of new products and socioenvironmental factors like marketing and advertising.

Results and Conclusions

MTP use patterns are complex, dynamic, and multiply determined by factors at the level of individuals, products, situations or contexts, and marketplace. Substitution, or using one product with the intent of decreasing use of another, and complementarity, or using multiple products for different reasons or purposes, explain patterns in MTP use. Moreover, substitution and complementarity may inform our understanding of how market changes targeted at one product, for instance, new product standards, bans, product pricing, and taxation, affect consumption of other tobacco products. New data from natural experiments and novel laboratory-based techniques add additional data and expand the framework.

Implications

A substantial proportion of people who use tobacco use more than one product. This review synthesizes and evaluates recent evidence on the diverse factors that affect MTP use in addition to expanding our framework. Our review is accompanied by suggested research questions that can guide future study.

Introduction

Multiple tobacco product use (MTP; ie, the regular use of two or more tobacco products), is an increasingly common pattern of tobacco use among adults in the United States. An unpublished analysis of data from Wave 4 (2017–2018) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) survey—a US nationally representative survey—indicates that 33% of the tobacco-using adult population (approximately 18 million people) has used two or more tobacco products within the past 30 days. The most prevalent forms of MTP use are: (1) dual use of combusted cigarettes (CCs) and e-cigarettes (ECs) (40.8% of those who use MTPs) and (2) dual use of CCs and cigarillos (32.3% of those who use MTPs) (Table 1; methods in Supplemental Information). Given its prevalence, understanding patterns of, and influences on, MTP use are critical to designing public health and regulatory strategies for decreasing population-level harm associated with tobacco use.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Past 30-Day Multiple Tobacco Product (MTP) Use, PATHa Wave 4, 2017–2018 (Total n = 33 744; Tobacco User n = 14 710)

| Cigarettes (n = 9657) |

E-cigarettes (n = 4082) |

Traditional cigars (n = 1894) |

Cigarillos (n = 2963) |

Little cigars (n = 1178) |

Pipe tobacco (n = 477) |

Hookah (n = 1258) |

Smokeless tobacco (n = 1603) |

Snus (n = 586) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall prevalence of MTP use among tobacco users = 33.2% | wt%b | wt% | wt% | wt% | wt% | wt% | wt% | wt% | wt% |

| Any other tobacco product | 34.8 | 67.8 | 71.9 | 83.8 | 90.0 | 80.8 | 70.7 | 56.2 | 91.2 |

| Cigarettes | — | 49.0 | 38.9 | 53.4 | 63.9 | 48.1 | 35.0 | 31.1 | 38.5 |

| E-cigarette | 17.6 | — | 26.3 | 33.4 | 33.8 | 37.5 | 42.1 | 16.7 | 25.3 |

| Traditional cigars | 7.6 | 14.3 | — | 36.9 | 33.4 | 37.3 | 20.5 | 12.3 | 16.0 |

| Cigarillos | 13.2 | 23.1 | 46.9 | — | 56.1 | 39.3 | 33.0 | 14.1 | 22.7 |

| Little cigars | 6.8 | 10.0 | 18.2 | 24.1 | — | 22.4 | 15.2 | 6.2 | 11.4 |

| Pipe tobacco | 2.2 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 7.2 | 9.5 | — | 7.1 | 4.2 | 6.5 |

| Hookah | 3.6 | 12.1 | 10.9 | 13.8 | 14.8 | 16.2 | — | 4.3 | 9.2 |

| Smokeless tobacco | 5.4 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 16.3 | 7.2 | — | 72.1 |

| Snus | 2.3 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 6.4 | 8.7 | 5.4 | 24.8 | — |

aPopulation Assessment of Tobacco and Health.

bWeighted percentage.

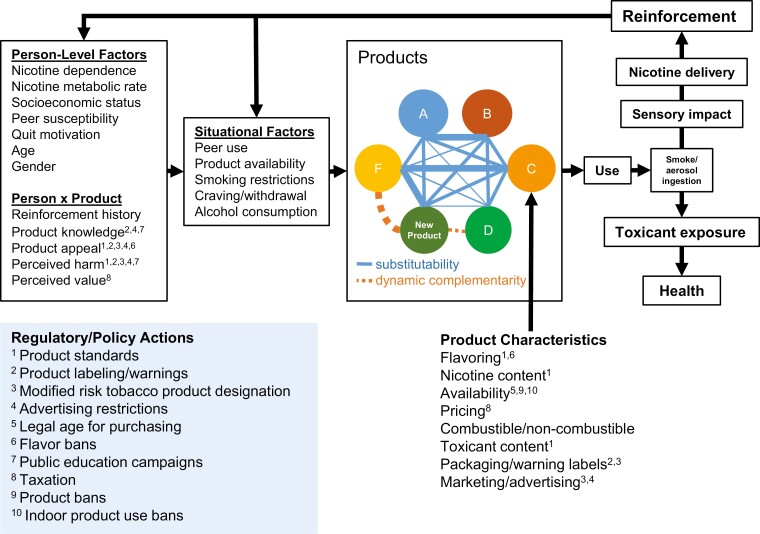

In 2019, we published a conceptual framework for describing and understanding MTP use1 (see Figure 1). The overarching premise of our framework is that the tobacco product marketplace is complex, diverse, and dynamic. Moreover, our framework suggested that single tobacco product (STP) and MTP use are multiply determined. A broad range of factors from person level such as age or quit motivation, product characteristics such as nicotine content, flavor, cost, and situations like smoking restrictions, and interactions between these factors determine who will find which products appealing and reinforcing and as such, determine who will buy and use various tobacco products. To the degree that tobacco products vary in their harmfulness,2 our framework suggests how tobacco use factors, policies, and regulations can impact on both individual- and population-level harm associated with tobacco use. This framework has been used in many varied contexts since its publication; one framework3 on public health law and legal interventions for physical activity was based conceptually on our original MTP use framework and other models of tobacco control policy, while a review4 on nicotine and nonnicotine-related factors in reducing the relative value of cigarettes also leaned on our framework to emphasize the importance of individual factors and context when an individual chooses which tobacco product to use.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of multiple tobacco product use (MTP) and points at which regulatory and policy actions have their impact (updated from ref. 1). In our conceptual model of MTP use, the degree of substitutive (blue lines) and complementary (orange dashed lines) use between products varies as a function of Person, Product, and Situational factors (and interactions between these factors). As new products enter the market, the above factors affect the degree to which substitutive and complementary relations emerge which in turn has downstream impacts on MTP use, toxicant exposure, and health. Policy and regulatory actions impact product characteristics which interact with person-level factors to influence use. Introducing or increasing a product tax, for instance, increases the price of a product, which in turn affects not only its perceived value and use, but also the perceived value and use of substitutive products.

In addition to influencing which tobacco products a person regularly purchases and uses, the factors outlined in our framework also influence how and under what circumstances products are used. We noted that tobacco users may find in the marketplace, and adopt the use of, substitutes for a currently used product. Under substitution, someone who smokes CCs may seek to replace some amount of their current nicotine intake with ECs, in an effort to reduce their overall level of harm associated with nicotine use.

We also make the case that products may serve as dynamic complements to one another.5 That is, a person may use two different tobacco products but each for different purposes and/or in different situations. A person who smokes cigarettes, for instance, may start using ECs in situations in which CCs are not permitted or when it puts others, such as children, at risk. Dynamic complementary use may serve to perpetuate nicotine dependence and result in no change or an increase in potential risk.

Finally, in our 2019 framework paper, we provided examples of how regulatory bodies—federal, state, and/or local—within the United States may influence STP and MTP use through policies and regulations. For instance, the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act gave the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate the manufacture, distribution, and marketing of tobacco products in order to improve the health of the public.6 We mapped how different strategies specifically target factors in the framework. For instance, a regulatory strategy limiting the availability of flavors of a given product will likely impact use of that product. In addition, we provided evidence from the literature suggesting how, in the context of a complex tobacco marketplace, regulating one tobacco product can have off-target effects. For instance, increasing taxes selectively on one product (eg, CCs) can increase purchases of other products (eg, cigars).7,8 Given the prevalence of MTP use, our overall recommendation was that increased research on MTP and dual use is urgently needed. Moreover, prior evidence suggests that MTP use can be associated with greater toxicant exposure9 and is associated with a shorter time to relapse and a decreased likelihood of cessation.10–13 More specifically, we recommended that more research is needed to evaluate potential off-target effects in order to prevent or mitigate unintended consequences in order to better inform tobacco product policy and regulation. We ended our paper with a call for additional research on MTP use including more mechanistic studies designed to increase our understanding of how changes in the appeal and reinforcing properties of one product, influence the appeal and reinforcing properties of other products in the marketplace. While some of our recommendations for future research from the original paper have been addressed and are discussed in this update, such as research on the effects of using one product on another and research on the effects of regulatory actions on the use of other tobacco products, others such as research on the health effects of MTP use and temporal patterns of use remain unaddressed and are still needed.

Since the publication of our 2019 framework paper, there has been new literature on MTP use including epidemiological, laboratory, and clinical research. This new research has reported on multiple natural experiments (eg, banning of e-liquid flavors in San Francisco; a 3-month ban on all EC sales in Massachusetts) and the results of these natural experiments have since been published. In addition, the marketplace has continued to evolve. For instance, while introduced globally prior to 2019, heated tobacco products (HTPs) such as IQOS have recently become available in more countries—including the United States—and the impact of these products on the consumption of other products in the market has been researched. Finally, since publication of our novel framework, approaches to the study of dual and MTP use have been newly employed including ecological momentary assessment (EMA) and experimental tobacco marketplaces (ETMs). These approaches allow for the study of complex dynamics associated with product choice and use.

In order to synthesize and analyze the new literature on MTP use while updating our previous conceptual model, we performed a critical review of the literature. Unlike systematic processes, critical reviews serve to aggregate literature by bringing together the most valuable pieces from previously published research.14 This review and its conceptual model, as well as other critical reviews, can serve as a launchpoint for further work rather than an endpoint.14 As with our prior paper on MTP use, we end this one with a summary of research and a call for the study of additional research questions.

Complementarity and Substitution

Central to our model, and as we noted in our 2019 paper,1 two tobacco products may serve as substitutes or dynamic complements to one another (see Introduction). Within our original framework paper, we acknowledged and discussed various examples of ways in which substitution and complementarity can be defined, including: behavioral economics, behavioral pharmacology, and self-reported motivations for tobacco product use.1 Consider hammers and screwdrivers as an analogy of complementary products. Both are required to build a house. Yet, each is used in different contexts or for different purposes, making them complementary tools. Likewise, tobacco products may substitute for, or complement one another, in different scenarios. One person who smokes CCs may use ECs as a substitute for CCs in an effort to cut down on the latter (substitution); another person may use both products, but only ECs in situations in which smoking CCs is not permitted (complementarity).

In addition to previous research investigating complementarity and substitution, a recent qualitative study by McQuoid et al. provides clear examples of these patterns of MTP use among young adults in California.15 Some participants in their study, for instance, reported clear evidence for substitution by reporting that they switch between products in order to reduce respiratory symptoms or because they perceive one product as being less harmful than another. Others reported complementary use as exemplified by the use of ECs in times or situations when nicotine consumption via CC would not be possible, for instance when indoors. Similarly, a nationally representative survey in England found that, among people who use both CCs and ECs, the prevalence of using ECs where smoking is not permitted increased from 45.1% in 2011 to 70.5% in 2020.16 This pattern of use was associated with a failed quit attempt in the last year and a lack of interest in cutting down on smoking. These emerging results indicate that (1) differing motives drive substitutive and complementary use, and (2) that complementary use may be associated with poorer cessation outcomes.

Emerging data suggests ways in which tobacco products may serve as complements of, or substitutes for, one another to varying degrees. Substitution can be relatively easy to evaluate in the context of a laboratory setting. For instance, Pacek et al.17 conducted a laboratory-based study that utilized a concurrent choice progressive ratio task to evaluate the substitutability of JUUL pods with various nicotine contents and flavors among regular users of JUUL. Using a two-choice progressive ratio task, findings indicated that 3% nicotine content pods served as a substitute for 5% nicotine content pods, whereas tobacco-flavored pods did not generally substitute for flavored pods regardless of the amount of work (button presses) required to obtain puffs of flavored pods. Similarly, another recent laboratory study compared plasma nicotine content levels and craving reduction following the use of IQOS, CCs, and JUUL18 among daily vapers. The authors, based on their findings, concluded that IQOS may be less likely to substitute for JUUL and CCs. While informative, because such studies are conducted in a single laboratory context, they do not inform on complementarity, which requires observing whether preferences for products vary as a function of situation or context.

Unlike laboratory studies, studies that utilize ecological momentary assessment (EMA) methodology, wherein the contexts in which tobacco products are used are assessed in the real world, provide a view into complementary use. In EMA studies, if individuals who use dual or MTPs are shown to use two or more tobacco products and the contexts or reasons for use do not differ between products, then the two products are more likely to be substitutes for one another. On the other hand, if the contexts and purposes for use vary systematically across products, it suggests that complementarity may be at play.

Three recent EMA studies have furthered our understanding of complementary use by examining dual and MTP use and identifying factors associated with the use of different tobacco products. In a 21-day EMA study of young adults who reported dual use of EC and CC, greater recent anxiety and alcohol use were associated with increased likelihood of CC, but not EC, use.19 Interestingly, boredom was associated with an increased likelihood of CC use among women, whereas the converse was observed for men.19 In a 14-day study20 of young adult African Americans who reported dual use of cigars and cigarettes showed that more cigarettes and cigars were smoked during periods of dual use than during periods of single product use. Moreover, differential product use was associated with affect and location; relaxation was associated with dual and cigar-only use and CC smoking was associated with being alone while cigar use was associated with being in a car. Finally, a 14-day EMA study was conducted among regular users of both CC and smokeless tobacco (SLT).21 Consistent with findings from the study by Mead et al.,20 more cigarettes were smoked—and cotinine levels were higher—on days during which both products were used, suggesting that SLT and CC were not functioning as substitutes. Moreover, participants used different products depending on location—SLT use for instance, was twice as likely in locations where smoking was discouraged or forbidden.

These data preliminarily suggest that, among individuals who use two tobacco products, the conditions (eg, affective states, smoking prohibition) under which cigarettes and ECs are used can and do vary, potentially pointing to complementary use of these two products. Importantly, two of these studies suggest that among dual users, the use of each product is greater in periods in which both products are used, further suggesting complementarity is at play. Finally, recent studies also highlight challenges in acquiring real-time assessments of MTP use including low compliance,22 poor agreement between EMA-based self-reports of use and both baseline19 and device-reported data23,24 and the need for new and more advanced methods for assessing MTP use in real-world contexts.

Effects of Introducing a New Product on Sales or Use of an Existing Product

The characteristics and use of new products can have important off-target effects on perceptions and use of other tobacco products. The introduction of ECs into the tobacco product marketplace is a prime example: data from adults in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) as well as the Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (TUS-CPS)—two US nationally representative surveys—suggest that past 12-month CC quit attempts and cessation have increased over a 10-year period and that use of EC is positively associated with both attempts and actual quitting.25 Data from adults in Waves 1–3 of the PATH Study also indicate that CC cessation was more likely among frequent EC users, those who had used EC during their last CC quit attempt, and among users of flavored EC.26 It is worth noting that accumulating data also indicates that youth and adolescents who use EC are more likely to experiment with or initiate use of CC at a later time point,27–30 though, as discussed in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, these studies are often limited methodologically.28

Another novel tobacco product that can help to illustrate this point is IQOS. IQOS is a HTP manufactured by Philip Morris International (PMI) that was introduced internationally in 2014 and to the US market in 2019. IQOS consists of a charger, battery-powered holder, and tobacco-filled sticks wrapped in paper (ie, heatsticks). When inserted into the holder, these heatsticks are heated with an electronically controlled element to produce an aerosol inhaled by the user. Though available in a larger variety of flavors internationally, IQOS heatsticks are available in the United States in only tobacco and menthol flavors.

New research has begun to examine the effects of introducing IQOS into the market. In a recent paper, Stoklosa et al.31 examined the effects of a staggered introduction of IQOS in multiple regions of Japan on sales of cigarettes between 2015 and 2016. In the regions examined, the introduction of IQOS was likely responsible for a decline in cigarette sales in the range of 0.63–0.66 cigarettes per person per month. Moreover, analyses indicated that these declines in cigarette consumption were not due to a nationwide “exogenous shock” (eg, change in tobacco policy or pricing) or to random factors. Cummings et al.32 also identified a similar trend in their analysis of whole country tobacco sales data, concluding that the accelerated decline in cigarette sales in Japan since 2016 corresponds to the introduction and growth in the sales of HTPs.

Sales data, however, do not speak to whether new users of IQOS switch exclusively from using CCs to IQOS or whether they only replace a portion of their cigarette use with IQOS. Recent work has emerged to describe risk perceptions, interest in quitting, and product use behavior that can begin to address this question. For instance, HTP users reported perceiving HTPs as being less harmful than CCs,33,34 with dual HTP and CC users in Japan being more likely than CCs only users to report that HTPs are less harmful than smoking.33 Additionally, research in Korea indicates that dual HTP and CC users are less34 or equally likely35 as CC-only users to report an interest in quitting tobacco use. Moreover, among Korean adults36 and adolescents37 who use CCs, dual use of HTPs increased the likelihood of CCs quit attempts, but reduced the likelihood of actual CCs cessation. Data from Wave 1 of the ITC Japan Survey also indicate that HTP may serve as complementary products rather than substitutes for CCs: no differences were observed in the frequency of smoking, number of cigarettes smoked per day, or smoking cessation behaviors between dual HTP and CC users and CC-only users.38

Effects of Pricing or Taxation of One Product on Another

Since publishing our framework in 2019, a number of studies have further demonstrated that altering the price of one tobacco product can affect not only sales of that product, but also others in the market. In particular, ECs and CCs have been shown to be economic substitutes: increasing taxation of CCs reduces traditional smoking while increasing EC use and vice versa.39,40

Recent studies demonstrate the effects of cigarette prices on EC use. In an analysis of Nielson retail indices in California, higher cigarette prices (largely due to taxation) were positively associated with per capita reusable EC sales, indicating substitution between CCs and ECs.41 Additionally, survey data indicate that 15–21 year-olds may use ECs to substitute for CC in the context of price differentials between the two products.42 CC prices were positively associated with EC use, with a 10% increase in cigarette prices leading to a 9.4% increase in past month EC use.

Similarly, EC taxation increases the use of CCs. Models based on currently available data predict that a national EC tax of $1.65/mL of EC fluid would lead to a projected 2.5 million additional adult daily CC smokers.40 This conclusion is consistent with data from Minnesota—the first US state to tax ECs—where EC taxation leading to a price increase of 40.7% was associated with a 5.4% increase in adult smoking rates.43 In addition, increased EC taxes increased the probability of prepregnancy smoking by 7.4% while reducing smoking cessation and prepregnancy and third trimester vaping.44

Product substitution due to pricing is also seen between models and flavors of ECs as well as other tobacco products. In California, price responses demonstrated that disposable ECs can serve as substitutes for reusable ECs when costs of the latter rise.41 Additionally, while neither EC nor CC taxes affected sales for cigars, loose tobacco, or chewing tobacco, increased taxes on ECs decreased the use of flavored ECs while increasing menthol CC smoking.39

ETM experiments simulate the complex tobacco marketplace, including variations in product strengths, flavors, prices, and availability under controlled conditions.45 In a typical ETM study, participants are presented with a website from which they can purchase products using credits. The ETM can be manipulated both by varying the products that are available and/or by varying product characteristics. Results from these studies further demonstrate the effects of tobacco product pricing on MTP choice. In one ETM study, an increased price of menthol CC led to substitution with nonmenthol CC, menthol little cigarillos, and menthol ECs.46 Nevertheless, in contrast to the many studies demonstrating substitutability between tobacco products, an ETM by Pope et al. showed that, in a sample of CC smokers with largely no prior EC use, taxing CC decreased CC demand but did not lead to substitution with EC.47 Similarly, e-liquid subsidization increased the initial intensity of e-liquid purchasing but did not significantly affect CC demand.47 Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of considering the potential effects on all tobacco products when imposing a tax or price change on any individual product.

Effects of Product Standard or Regulation on Use of Other Products

As with the entrance of a new product, regulation of existing products (eg, banning flavored cigarettes) affects not only the use of the target product but also the use of other tobacco products in the market. The effects of banning flavors in tobacco products have been investigated via analyses of real-world enacted bans as well as hypothetical experiments. For example, following a San Francisco ban on all flavored tobacco products, overall flavored tobacco use among 18–24 year-olds decreased by 12% and CC smoking increased by 9.7% but not significantly.48 Nevertheless, a different analysis found the San Francisco ban to be associated with more than doubled odds of smoking among high schoolers, potentially due to substitution of flavored ECs with unflavored cigarettes.49 A third investigation of the San Francisco ban used Nielson retail data to find that the flavor restriction decreased flavored tobacco sales in addition to total tobacco sales.50

The FDA recently announced that it is committed to advancing a product standard that would ban menthol in CCs and all flavors in cigars in the United States51 and bans in other jurisdictions may inform what will happen if such a ban occurs. Sales of all CCs decreased by 128 million CCs in Ontario following a menthol cigarette ban while no change was observed in British Columbia, which did not enact a ban.52 After the ban in Ontario, menthol smokers were more likely to quit smoking and also reported more quit attempts than nonmenthol smokers. Interestingly, menthol smokers who had not quit at 1-year follow-up were less likely (adjusted relative risk ratio = 0.26) to have quit CCs by the 2-year mark if they also used other flavored tobacco products (eg, ECs, cigars, SLT, etc.) at baseline, implying a potential substitutive effect.53 These results point to mixed effects from a menthol ban, in which CC sales may decrease but quitting menthol smoking could be complicated by substitution effects of other tobacco products.

Further evidence supporting the potential effects of a change in menthol policy comes from hypothetical experiments and surveys. Among young adults who use CCs and ECs, a hypothetical restriction on menthol CC was associated with intentions to increase EC use.54 These effects may be changing over time—between 2011 and 2016, young adult menthol smokers displayed a 7.4%–13.2% increase in interest in switching to another tobacco product given a menthol CC ban.55 Additionally, as previously described, an ETM study showed that as menthol CC increased in price, menthol smokers partially substituted them with nonmenthol CC and other menthol-flavored products such as ECs, little cigars, and cigarillos.46 Therefore, limiting access to menthol CC may decrease menthol smoking rates, in part via substitution with other products. This is consistent with the findings of increased substitution of available products following a US CC flavor ban in 2009, as described in our initial conceptual framework paper.1

As the FDA remains committed to a product standard that would substantially reduce the nicotine content in CC, new research is evaluating the impact of such regulation on the use of other tobacco and nicotine products. In an ongoing multisite clinical trial, being conducted as part of the Center for Evaluation of Nicotine in Cigarettes (CENIC), participants access an ETM where they are given vouchers for a specified number of points that can be exchanged for study CC (very low nicotine content [VLNC] or normal nicotine content) and a variety of noncombusted nicotine-containing products, including ECs and FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).

In addition to this ongoing work, hypothetical studies and ETMs have explored the relationship between nicotine content in CC and MTP use. One study found that among young adult dual users, a hypothetical VLNC standard in CCs was associated with increased intentions to quit or reduce CCs and increased use of ECs.54 Additionally, in an ETM, ECs were a strong substitute for CC across varied nicotine strengths, with the highest e-liquid strength available serving as the strongest substitute.56 This work collectively demonstrates the potential for decreased nicotine content in CCs to decrease CC demand while increasing EC demand, especially at higher e-liquid nicotine levels.

Effects of Messaging and Warning Labels on MTP Use

Within our MTP framework, product messaging and warning labels affect appeal and demand for not only the product being advertised, but also for other products, thereby impacting MTP use. An online experiment investigating messaging around the comparative risk of CCs and ECs revealed that, relative to control messages, comparative risk messages increased intentions to switch to ECs.57 Furthermore, exposing participants to a nicotine fact sheet before exposure to the messages increased self-efficacy in making a complete switch to ECs. A similar online experiment by the same investigators found that comparative risk messages did not increase dual use intentions relative to smoking cessation or an exclusive switch to ECs.58 Additionally, among an online sample of US adults who use ECs only, CCs only, and who report use of both products, messages conveying the harms of using EC products were found to be more discouraging of vaping use among exclusive users of CCs than among exclusive EC or users of both products.59 Other research has shown that EC text and pictorial warnings are associated with EC users’ interest in quitting EC use, in addition to being associated with smokers being less interested in smoking.60 An additional study focused on the effects of exposure to graphic warning messages about CC on intentions to use alternate tobacco products and quit cigarette use.61 Following exposure to such messages, 68% of participants reported intentions to use ECs, with intentions to use other alternative tobacco products (ie, snus, hookah, SLT) ranging from 31% to 40%. Collectively, these findings indicate that messages may decrease interest in CC smoking but have differential effects on EC interest among CC users, while graphic warning messaging targeted at CCs may increase interest in using alternative products.

Risk Perceptions Among People Who Use MTPs

Risk perceptions of tobacco products can be informed by a variety of factors, including characteristics of the product itself; the sensory impact of the product, and the user’s knowledge regarding product-related harms or safety.1 Risk perception, in turn, has the potential to influence the appeal and use of both STPs and MTPs.

Recent evidence suggests that risk perception varies as a function of MTP use status. In a cross-sectional analysis of young adults who ever tried a tobacco product, having tried a greater number of products was associated with lower perceptions of harm associated with all tobacco products.62 In a study previously discussed in this paper, among individuals who reported exclusively using CCs and individuals who reported dual use of CCs and HTPs in Japan, individuals reporting dual use were more likely than those reporting exclusive use of CC to believe that HTPs are less harmful products.33 Lin et al.,63 in an analysis of PATH Wave 1 data, found that harm perceptions of CC use were greatest among people reporting EC only use, followed by dual use, and were least among individuals who reported using only CCs. Additionally, believing that it is “easy to quit using” CCs—regardless of whether a youth reported using CC—was associated with MTP use among youth surveyed in the Florida Youth Tobacco Survey, suggesting that addiction-related risk perceptions have a nuanced association with MTP use.64

Moreover, longitudinal data continue to provide evidence that tobacco product risk perceptions can influence future use of STP and MTP, as well as associated tobacco use behaviors (eg, interest in quitting). Data from PATH Waves 1 and 2 indicate that among adults, perceiving a non-CC tobacco product as being less harmful than smoking CCs at Wave 1 was associated with a greater likelihood of using that product at Wave 2.65 Risk perceptions also influence MTP use. Data from dual EC and CC users in the PATH Waves 2 and 3 indicated that those who perceive ECs as being less harmful than CC—as compared with those who perceive ECs as being as or more harmful than CCs—are more likely to switch to exclusive use of ECs or are more likely to remain dual users over a 1-year period. Additionally, those who perceive ECs as being less harmful than cigarettes are significantly less likely to switch to exclusive CC use over the course of 1 year.66

Summary and Future Directions

One-third of people in the United States who use tobacco products use multiple products, and a growing body of research addresses the complex and dynamic factors impacting such MTP use. In our 2019 review, we encouraged future research on the prevalence, correlates, and temporal patterns of MTP use, the effects of using one product on another, the effects of STP regulatory actions on other products, and the health effects of MTP use. Further research and analyses are still needed, both in these areas and in new arenas of MTP use and regulation. As the FDA considers the wide-ranging effects of tobacco regulation, we recommend that continued research investigate the following questions:

Characterization of MTP use disparities and use patterns among different populations. To date, little research has investigated MTP use and use patterns as a function of demographic and other characteristics, for instance mental health status. Given that patterns of STP use and outcomes have been shown to significantly differ by sex,67 additional research is needed to explore whether the same holds true for MTP use. Likewise, whereas a small number of studies have addressed racial or ethnic disparities in MTP use,68,69 such data are sparse and additional data are needed. In addition, though US smoking rates have decreased in the general population, the prevalence of tobacco use is increasingly and disproportionately high in vulnerable populations, such as persons identifying as LGBTQ, persons with disabilities, those of low socioeconomic status, and people with behavioral health conditions.70 There is currently minimal research on MTP use in these groups.71,72 Future research in and with more diverse samples will better inform policies that affect the entire population and help address disparities and unique needs of marginalized groups.

Varied approaches to understand the processes of dynamic complementarity and substitution, particularly among new and emerging dual and MTP users. An increasing number of randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effects of substituting ECs for CCs as a potential harm reduction strategy. At trial’s end, many of these studies have observed dual use of CCs and ECs among individuals who were CC-only users at the outset of the intervention. For example, in a recent trial of EC substitution,73 57.9% of CC smokers randomized to use ECs were dual users at the final study time point. Despite the increasing importance of understanding dual and MTP use, EC randomized controlled trials often do not implement the necessary methodology to investigate the dynamics of use patterns and subsequent health effects.73–76 Specifically, where feasible, future randomized controlled trials should include longer term follow-up periods to evaluate whether dual use persists when EC are no longer provided for free. In addition, EMA can be incorporated into such trials in order to examine dynamic patterns of and reasons for use of both CCs and ECs. Such research can identify individual differences in the likelihood of becoming a dual user and factors that promote dual use, and potentially point to approaches for minimizing dual use or continued smoking as outcomes.

Multilevel analyses that look at the effect of broader social factors on individual use patterns. Per our framework, MTP use is determined by person, product, and context or situation factors, but also higher-level social and cultural factors. In a social pharmacoepidemiology framework, Leventhal emphasized the role of concurrent contextual factors such as neighborhood environment and tobacco industry marketing as well as disparity group membership on tobacco use.77 Spatial analysis of phenomena like the density of tobacco retail outlets and the association with tobacco product use can be applied to answer questions related to MTP use. Studies of other contextual factors like neighborhood tobacco retail outlet product availability78,79 or tobacco product use norms, can help explain population-level prevalence of MTP use. We recommend that tobacco researchers implement multilevel analyses that focus on how MTP use and use patterns at the person level (complementarity and substitution measured with EMA, for instance) relate to geographic and population-level socioenvironmental factors. Such multilevel analyses can provide a more nuanced understanding of MTP use and lead to more precise predictions of the effects of targeted policy interventions.

Collecting data on the effects of tobacco regulatory actions on MTP use. The studies described in this review begin to show potential effects of taxation and flavor and nicotine content regulation on MTP use. Nevertheless, more work is needed to better evaluate proposed policies such as a menthol ban or nicotine content limit in the current complex tobacco marketplace. Multiple ongoing studies are beginning to simulate the effects of potential policies on MTP use. For instance, a University of Wisconsin trial is evaluating tobacco use behavior in people who smoke CCs who are randomized to switch to VLNCs, ECs, or no alternative product (5R01CA239309-03). Additional research is needed to evaluate the way in which product availability,80 graphic warning labels, and health messages associated with one product, influence the appeal and use of other products. Such research can identify optimal policy and messaging to alter the use of one product, while avoiding unintended consequences, including the uptake and use of combusted products. Real-time data collection and analysis of the impact of tobacco control policies on MTP use as these policies are enacted, even at the state or local level, must continue in the changing regulatory environment. An example of this is a study by Kalkhoran et al.81 that found that, following a 3-month ban of ECs in Massachusetts in 2019, 83% of dual CC and EC users who increased CC smoking had quit or reduced using ECs due to the ban. Additionally, as new tobacco products are introduced, it is essential to quickly begin research on both the new product itself as well as its effects on the use of existing tobacco products.

Understanding the tobacco industry’s role in encouraging complementary use. Given the strong and wide-reaching effects of advertising and messaging on MTP use, additional investigation into the ways in which the tobacco industry promotes dual and MTP use is needed. Multiple EC manufacturers have advertised products in a way that specifically encourages the complementary use of ECs when CC smoking is not possible. For instance, Blu, an EC manufactured by Imperial Brands, advertises “take back your freedom to smoke anywhere with blu electronic cigarettes.” 82 JUUL similarly utilizes paid Instagram influencers to encourage dual, complementary use of cigarettes and ECs, with posts about using Juul when “smoking cigarettes is not an option.” 82 More research is needed to evaluate whether exposure to such messaging influences tobacco user’s attitudes about dual use and is associated with increased anticipated or actual dual use. Data resulting from this research can inform regulations around product advertising.

Consideration of NRT in the MTP marketplace. NRT is an important component of the tobacco marketplace. To date, little research on MTP use has assessed the effects of NRT use on the use of tobacco products other than CCs, and less research still on the effects of NRT on MTP use. One recent study focusing on NRT and MTP use, an analysis of retail sales data, indicates that while higher cigarette prices were associated with increased NRT gum purchasing, higher EC prices were associated with decreased nicotine gum sales.83 This same study investigated product messaging in the context of pricing, finding that EC TV advertisements were positively associated with the sale of nicotine gum, and nicotine patch advertisements were positively associated with patch and gum sales. While this study begins to show some of the effects of the dynamic tobacco marketplace on NRT demand and vice versa, more research is needed to further investigate this alongside both CC and new tobacco products that emerge.

Limitations

While this paper strives to comprehensively report on MTP research in the time since the previous review, it is not systematic in its approach and thus may not to include all relevant works. Additionally, even though research studies from various countries are described and analyzed, much of the paper analyzes work based in the United States and considerations for the unique FDA regulatory environment, limiting generalizability to regulatory environments that are substantially different.

Conclusions

This paper updates and adds to the conceptual framework for understanding MTP use, in which Person, Product, and Context or Situation factors affect MTP use across time and place for persons who use tobacco. Moreover, our review further demonstrates the framework’s value in interpreting the findings of studies of MTP use. The studies reviewed here further delineate the ways in which tobacco products may serve as dynamic complements or substitutes for each other in a variety of situations, in addition to evaluating the impacts of contextual factors and product characteristics on MTP use. Notably, the introduction and increased use of novel noncombusted products in the market, such as ECs and IQOS, shifts the balance of MTP use and may affect the use of previously existing tobacco products. Both the analysis throughout this review and the ensuing recommendations are closely aligned with the FDA Center for Tobacco Products’ strategic priorities of product standards and comprehensive FDA nicotine regulatory policy,84 so as new tobacco products are introduced and the FDA and other regulatory agencies and policy makers consider regulatory actions on any one tobacco product or characteristic (eg, flavor), off-target effects in the realm of MTP use must be considered. Future work should continue to characterize the complexities of MTP use in order to best provide information for these potential regulations while considering MTP use within the context of this updated framework.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Contributor Information

Dana Rubenstein, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

Lauren R Pacek, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

F Joseph McClernon, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health K01 DA043413 (LRP) and R01 DA048454 (FJM).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Pacek LR, Wiley JL, McClernon FJ. A conceptual framework for understanding multiple tobacco product use and the impact of regulatory action. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(3):268–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nau T, Smith BJ, Bauman A, Bellew B. Legal strategies to improve physical activity in populations. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(8):593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. White CM, Hatsukami DK, Donny EC. Reducing the relative value of cigarettes: considerations for nicotine and non-nicotine factors. Neuropharmacology. 2020;175:108200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abrams DB, Glasser AM, Pearson JL, et al. Harm minimization and tobacco control: reframing societal views of nicotine use to rapidly save lives. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:193–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shocker AD, Bayus BL, Kim N. Product complements and substitutes in the real world: the relevance of “other products.” J Mark. 2004;68(1):28–40. https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/1256. [Google Scholar]

- 6. U.S. Congress. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Federal Reform Act. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delnevo CD. Smokers’ choice: what explains the steady growth of cigar use in the U.S.? Public Health Rep. 2006;121(2):116–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Foulds J, Steinberg MB. Cigar use before and after a cigarette excise tax increase in New Jersey. Addict Behav. 2004;29(9):1799–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamari AK, Toljamo TI, Kinnula VL, Nieminen PA. Dual use of cigarettes and Swedish snuff (snus) among young adults in Northern Finland. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(5):768–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kasza KA, Bansal-Travers M, O’Connor RJ, et al. Cigarette smokers’ use of unconventional tobacco products and associations with quitting activity: findings from the ITC-4 U.S. cohort. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(6):672–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tomar SL, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among US males: findings from national surveys. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):104–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wetter DW, McClure JB, de Moor C, et al. Concomitant use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco: prevalence, correlates, and predictors of tobacco cessation. Prev Med. 2002;34(6):638–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grant MJ, Booth AA. typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McQuoid J, Keamy-Minor E, Ling PA. Practice theory approach to understanding poly-tobacco use in the United States. Crit Public Health. 2020;30(2):204–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jackson SE, Beard E, Brown J. Smokers’ use of e-cigarettes in situations where smoking is not permitted in England: quarterly trends 2011–2020 and associations with sociodemographic and smoking characteristics. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pacek LR, Kozink RV, Carson CE, McClernon FJ. Appeal, subjective effects, and relative reinforcing effects of JUUL that vary in flavor and nicotine content. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;29(3):279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Smith KM, Pesola F, Hajek P. Nicotine delivery and user reactions to Juul EU (20 mg/ml) compared with Juul US (59 mg/ml), cigarettes and other e-cigarette products. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(3):825–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg CJ, Haardörfer R, Payne JB, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of various tobacco product use among young adults. Addict Behav. 2019;92:38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mead EL, Chen JC, Kirchner TR, Butler J, Feldman RH. An ecological momentary assessment of cigarette and cigar dual use among African American young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(suppl 1):S12–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Felicione NJ, Ozga-Hess JE, Ferguson SG, et al. Cigarette smokers’ concurrent use of smokeless tobacco: dual use patterns and nicotine exposure. Tob Control. 2021;30(1):24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Griffiths NG, Fetterman JL, Vargees C, et al. Measuring poly-tobacco product use with ecological momentary assessment. Tob Regul Sci. 2020;6(6):423–435. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pearson JL, Elmasry H, Das B, et al. Comparison of ecological momentary assessment versus direct measurement of e-cigarette use with a Bluetooth-enabled e-cigarette: a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(5):e84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Z, Benowitz-Fredericks C, Ling PM, Cohen JE, Thrul J. Assessing young adults’ ENDS use via ecological momentary assessment and a smart Bluetooth enabled ENDS device. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(5):842–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson L, Ma Y, Fisher SL, et al. E-cigarette usage is associated with increased past-12-month quit attempts and successful smoking cessation in two US population-based surveys. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(10):1331–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glasser AM, Vojjala M, Cantrell J, et al. Patterns of e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking cessation over 2 years (2013/2014–2015/2016) in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(4):669–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with subsequent initiation of tobacco cigarettes in US youths. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lozano P, Barrientos-Gutierrez I, Arillo-Santillan E, et al. A longitudinal study of electronic cigarette use and onset of conventional cigarette smoking and marijuana use among Mexican adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;180:427–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miech R, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. E-cigarette use as a predictor of cigarette smoking: results from a 1-year follow-up of a national sample of 12th grade students. Tob Control. 2017;26(e2):e106–e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stoklosa M, Cahn Z, Liber A, Nargis N, Drope J. Effect of IQOS introduction on cigarette sales: evidence of decline and replacement. Tob Control. 2019:tobaccocontrol-2019-054998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cummings KM, Nahhas GJ, Sweanor DT. What is accounting for the rapid decline in cigarette sales in Japan? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10). doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gravely S, Fong GT, Sutanto E, et al. Perceptions of harmfulness of heated tobacco products compared to combustible cigarettes among adult smokers in Japan: findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7). doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Park J, Kim HJ, Shin SH, et al. Perceptions of heated tobacco products (HTPs) and intention to quit among adult tobacco users in Korea. J Epidemiol. 2021. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ryu D-H, Park S-W, Hwang JH. Association between intention to quit cigarette smoking and use of heated tobacco products: application of smoking intensity perspective on heated tobacco product users. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim J, Lee S, Kimm H, et al. Heated tobacco product use and its relationship to quitting combustible cigarettes in Korean adults. PLoS One. 2021;16(5):e0251243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kang SY, Lee S, Cho H-J. Prevalence and predictors of heated tobacco product use and its relationship with attempts to quit cigarette smoking among Korean adolescents. Tob Control. 2021;30(2):192–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sutanto E, Miller C, Smith DM, et al. Concurrent daily and non-daily use of heated tobacco products with combustible cigarettes: findings from the 2018 ITC Japan Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cotti CD, Courtemanche CJ, Maclean JC, et al. The effects of e-cigarette taxes on e-cigarette prices and tobacco product sales: evidence from retail panel data. NBER Work Pap Ser. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pesko MF, Courtemanche CJ, Catherine Maclean J. The effects of traditional cigarette and e-cigarette tax rates on adult tobacco product use. J Risk Uncertain. 2020;60(3):229–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yao T, Sung H-Y, Huang J, et al. The impact of e-cigarette and cigarette prices on e-cigarette and cigarette sales in California. Prev Med Rep. 2020;20:101244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cantrell J, Huang J, Greenberg MS, et al. Impact of e-cigarette and cigarette prices on youth and young adult e-cigarette and cigarette behaviour: evidence from a national longitudinal cohort. Tob Control. 2020;29(4):374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Saffer H, Dench D, Grossman M, Dave D. E-cigarettes and adult smoking: evidence from Minnesota. J Risk Uncertain. 2020;60(3):207–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Abouk R, Adams S, Feng B, Maclean JC, Pesko MF. The effect of e-cigarette taxes on pre-pregnancy and prenatal smoking. NBER Work Pap Ser. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bickel WK, Pope DA, Kaplan BA, et al. Electronic cigarette substitution in the experimental tobacco marketplace: a review. Prev Med. 2018;117:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Denlinger-Apte RL, Cassidy RN, Carey KB, et al. The impact of menthol flavoring in combusted tobacco on alternative product purchasing: a pilot study using the Experimental Tobacco Marketplace. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;218:108390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pope DA, Poe L, Stein JS, et al. The experimental tobacco marketplace: demand and substitutability as a function of cigarette taxes and e-liquid subsidies. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(5):782–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yang Y, Lindblom EN, Salloum RG, Ward KD. The impact of a comprehensive tobacco product flavor ban in San Francisco among young adults. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;11:100273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Friedman AS. A difference-in-differences analysis of youth smoking and a ban on sales of flavored tobacco products in San Francisco, California. JAMA Pediatr. 2021. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.0922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gammon DG, Rogers T, Gaber J, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive flavoured tobacco product sales restriction and retail tobacco sales. Tob Control. 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Commits to Evidence-Based Actions Aimed at Saving Lives and Preventing Future Generations of Smokers. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-commits-evidence-based-actions-aimed-saving-lives-and-preventing-future-generations-smokers. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chaiton M, Schwartz R, Shuldiner J, Tremblay G, Nugent R. Evaluating a real world ban on menthol cigarettes: an interrupted time-series analysis of sales. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(4):576–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chaiton M, Schwartz R, Cohen JE, Soule E, Zhang B, Eissenberg T. Prior daily menthol smokers more likely to quit two years after a menthol ban than non-menthol smokers: a population cohort study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021; 23(9):1584–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pacek LR, Oliver JA, Sweitzer MM, McClernon FJ. Young adult dual combusted cigarette and e-cigarette users’ anticipated responses to a nicotine reduction policy and menthol ban in combusted cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:40–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rose SW, Ganz O, Zhou Y, et al. Longitudinal response to restrictions on menthol cigarettes among young adult US menthol smokers, 2011–2016. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1400–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pope DA, Poe L, Stein JS, et al. Experimental tobacco marketplace: substitutability of e-cigarette liquid for cigarettes as a function of nicotine strength. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):206–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yang B, Popova L. Communicating risk differences between electronic and combusted cigarettes: the role of the FDA-mandated addiction warning and a nicotine fact sheet. Tob Control. 2020;29(6):663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang B, Owusu D, Popova L. Testing messages about comparative risk of electronic cigarettes and combusted cigarettes. Tob Control. 2019;28(4):440–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rohde JA, Noar SM, Mendel JR, et al. E-cigarette health harm awareness and discouragement: implications for health communication. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(7):1131–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brewer NT, Jeong M, Hall MG, et al. Impact of e-cigarette health warnings on motivation to vape and smoke. Tob Control. 2019;28(e1):e64–e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Morgan JC, Sutton JA, Yang S, Cappella JN. Impact of graphic warning messages on intentions to use alternate tobacco products. J Health Commun. 2020;25(8):613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Leavens ELS, Stevens EM, Brett EI, et al. JUUL electronic cigarette use patterns, other tobacco product use, and reasons for use among ever users: results from a convenience sample. Addict Behav. 2019;95:178–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lin W, Martinez SA, Ding K, Beebe LA. Knowledge and perceptions of tobacco-related harm associated with intention to quit among cigarette smokers, e-cigarette users, and dual users: findings from the US Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Wave 1. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(4):464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lee Y, Pepper J, MacMonegle A, et al. Examining youth dual and polytobacco use with e-cigarettes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(4):699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Elton-Marshall T, Driezen P, Fong GT, et al. Adult perceptions of the relative harm of tobacco products and subsequent tobacco product use: longitudinal findings from waves 1 and 2 of the population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study. Addict Behav. 2020;106:106337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Persoskie A, O’Brien EK, Poonai K. Perceived relative harm of using e-cigarettes predicts future product switching among US adult cigarette and e-cigarette dual users. Addiction. 2019. doi: 10.1111/add.14730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, et al. Gender, race, and education differences in abstinence rates among participants in two randomized smoking cessation trials. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(6):647–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brasky TM, Hinton A, Doogan NJ, et al. Characteristics of the tobacco user adult cohort in urban and rural Ohio. Tob Regul Sci. 2018;4(1):614–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Corral I, Landrine H, Simms DA, Bess JJ. Polytobacco use and multiple-product smoking among a random community sample of African-American adults. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Creamer M, Wang T, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Higgins ST, Tidey JW, Sigmon SC, et al. Changes in cigarette consumption with reduced nicotine content cigarettes among smokers with psychiatric conditions or socioeconomic disadvantage: 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ridner SL, Ma JZ, Walker KL, et al. Cigarette smoking, ENDS use and dual use among a national sample of lesbians, gays and bisexuals. Tob Prev Cessat. 2019;5:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, et al. Effect of pod e-cigarettes vs cigarettes on carcinogen exposure among African American and Latinx smokers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2026324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Eisenberg MJ, Hébert-Losier A, Windle SB, et al. Effect of e-cigarettes plus counseling vs counseling alone on smoking cessation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324(18):1844–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(7):629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ozga-Hess JE, Felicione NJ, Ferguson SG, et al. Piloting a clinical laboratory method to evaluate the influence of potential modified risk tobacco products on smokers’ quit-related motivation, choice, and behavior. Addict Behav. 2019;99:106105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Leventhal AM. The sociopharmacology of tobacco addiction: implications for understanding health disparities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18:110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Giovenco DP, Spillane TE, Merizier JM. Neighborhood differences in alternative tobacco product availability and advertising in New York City: implications for health disparities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(7):896–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. King JL, Wagoner KG, Suerken CK, et al. Are waterpipe café, vape shop, and traditional tobacco retailer locations associated with community composition and young adult tobacco use in North Carolina and Virginia? Subst Use Misuse. 2020;55(14):2395–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. White AM, Ossip DJ, Snell LM, et al. Tobacco product access scenarios influence hypothetical use behaviors. Tob Regul Sci. 2021;7(3):184–202. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kalkhoran S, Kalagher KM, Neil JM, Rigotti NA. Cigarette and e-cigarette use among smokers after a statewide e-cigarette sales ban. Tob Regul Sci. 2021;7(2):135–143. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Dewhirst T. Co-optation of harm reduction by Big Tobacco. Tob Control. 2020:tobaccocontrol-2020-056059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Huang J, Wang Y, Duan Z, et al. Do e-cigarette sales reduce the demand for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products in the US? Evidence from the retail sales data. Prev Med. 2020;145:106376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Food and Drug Administration. CTP’s Key Strategic Priorities. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/about-center-tobacco-products-ctp/ctps-key-strategic-priorities. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.