Abstract

Introduction

Alcohol and tobacco are commonly used together. Social influences within online social networking platforms contribute to youth and young adult substance use behaviors. This study used a sample of alcohol- and tobacco-related tweets to evaluate: (1) sentiment toward co-use of alcohol and tobacco, (2) increased susceptibility to tobacco use when consuming alcohol, and (3) the role of alcohol in contributing to a failed attempt to quit tobacco use.

Methods

Data were collected from the Twitter API from January 1, 2019 through December 31, 2019 using tobacco-related keywords (e.g., vape, ecig, smoking, juul*) and alcohol-related filters (e.g., drunk, blackout*). A total of 78,235 tweets were collected, from which a random subsample (n = 1,564) was drawn for coding. Cohen’s Kappa values ranged from 0.66 to 0.99.

Results

Most tweets were pro co-use of alcohol and tobacco (75%). One of every ten tweets reported increased susceptibility to tobacco use when intoxicated. Non-regular tobacco users reported cravings for and tobacco use when consuming alcohol despite disliking tobacco use factors such as the taste, smell, and/or negative health effects. Regular tobacco users reported using markedly higher quantities of tobacco when intoxicated. Individuals discussed the role of alcohol undermining tobacco cessation attempts less often (2.0%), though some who had quit smoking for prolonged periods of time reported reinitiating tobacco use during acute intoxication episodes.

Conclusions

Tobacco cessation interventions may benefit from including alcohol-focused components designed to educate participants about the association between increased susceptibility to tobacco use when consuming alcohol and the role of alcohol in undermining tobacco cessation attempts.

Implications

Sentiment toward co-use of alcohol and tobacco on Twitter is largely positive. Individuals reported regret about using tobacco, or using more than intended, when intoxicated. Those who had quit smoking or vaping for prolonged periods of time reported reinitiating tobacco use when consuming alcohol. While social media-based tobacco cessation interventions like the Truth Initiative’s “Ditch the Juul” campaign demonstrate potential to change tobacco use behaviors, these campaigns may benefit from including alcohol-focused components designed to educate participants about the association between increased susceptibility to tobacco use when consuming alcohol and the role of alcohol in undermining tobacco cessation attempts.

Introduction

Alcohol is commonly used among youth and young adults in the United States (US), despite its deleterious effects (e.g., disruption of normal growth and brain development, school problems, unprotected sexual activity, use of other drugs).1,2 Approximately one in five underage youth aged 12–20 report drinking alcohol in the past month, and more than one in ten report binge drinking during the same time period (i.e., consuming five or more drinks on an occasion for males and consuming four or more drinks on an occasion for females).2 Furthermore, over three million US young adults meet diagnostic criteria for an alcohol use disorder.2 Harmful alcohol use constitutes a serious public health threat, representing the third leading cause of preventable death and accounting for $250 billion in societal costs per year.3

Similarly, youth and young adult tobacco use—in large part due to the influx in e-cigarette use among this population—persists as a significant public health concern.4,5 Over half of US high school students have tried a tobacco product, and one in five have used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.5 Alcohol and tobacco are commonly used together.6–8 Compared to non-smokers, smokers are significantly more likely to consume alcohol and engage in binge-drinking.9 Meta-analyses note adolescent e-cigarette users were over six times more likely to consume alcohol and to binge drink compared to non-e-cigarette users.8 One explanation for the co-use of alcohol and tobacco use is the multiplicative, synergistic effects experienced when using alcohol and nicotine concurrently10; young adults report experiencing increased pleasure from e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes when concurrently drinking alcohol.11 Co-use is particularly concerning as both alcohol and tobacco are singularly linked with increased risk for developing cancer and other diseases (e.g., heart, liver, and lung disease).12,13 Moreover, there is evidence of a multiplicative interaction for cancer risks when alcohol and tobacco are used in combination.14 Furthermore, prior research contends alcohol use can play a role in undermining tobacco cessation attempts15,16; tobacco and alcohol co-users who quit both alcohol and tobacco use are over eight times more likely to stop smoking than those who continue to use alcohol during their smoking cessation attempt.16

Importantly, social processes related to tobacco and alcohol co-use occur in physical gatherings as well as in virtual contexts, such as online social networking sites (SNSs), which influence youth and young adult substance use risk behaviors.17,18 For example, exposure to friends’ online SNS content depicting partying or drinking is significantly associated with adolescent and young adult risk for alcohol and tobacco use.17,18 Moreover, alcohol and tobacco industry marketers use SNS digital platforms to promote their products to young audiences, and exposure to these digital promotional activities is linked to higher levels of drinking and smoking behavior.19–23 This is particularly concerning given the growing preference for SNS use among young audiences and themes appealing to youth that alcohol brands employ on their social media platforms.24,25 Contexts and impacts of these social influences differ across popular online SNS platforms, so it is important to focus on individual platforms in a manner that accounts for their uniquely diverse characteristics. The present study focuses specifically on Twitter.

Alcohol and Tobacco Use Surveillance on Twitter

Twitter, a SNS platform allowing individuals to post brief text statements often accompanied by images and links (i.e., tweets), is used by nearly 40% of 18 to 29-year-olds in the US.24 Twitter is a particularly useful venue for observing health-related behaviors given the largely public nature and brevity of tweets. The character limit of a single tweet (i.e., 280 characters) constrains salient contexts of health behavior into concise units of analysis, which is ideal for targeted studies using descriptive, mixed methods.26 Twitter users can also share the original tweets posted by other users (i.e., retweets) with their broader Twitter social networks, allowing for enhanced promotion of ideas, attitudes, and beliefs.27 Given the proliferation of Twitter and society’s growing reliance on social media for information about health issues,28 researchers have explored portrayals of substance use (e.g., alcohol, tobacco) on Twitter.29,30 The majority of alcohol-related tweets (a) express overwhelmingly positive sentiment toward alcohol, (b) frequently depict heavy drinking, and (c) rarely portray any alcohol-related negative consequences.29 Twitter sentiment toward tobacco use expressed on Twitter is also largely positive and presents tobacco us in concerning ways, such as posting about using e-cigarettes in places where tobacco use is illegal or prohibited (e.g., in school bathrooms).30 Moreover, prior research has shown many of these tweets are being followed and shared by adolescents.31

Along these lines, social media posts can be used as a valuable source of data—leveraging insights into health topics such as tobacco use and public health policy—with real-world implications on public health promotion and policy development and evaluation. For example, Twitter has been used as a real-time surveillance system to evaluate individual’s reactions to e-cigarette education campaigns, providing information to enhance future programming.32 To complement traditional tobacco policy evaluations (e.g., retailer compliance checks, well-established epidemiological approaches), social-media-based methodologies can be used to surveil discussions relevant to policy issues (e.g., Tobacco 21; flavor restrictions).33

While prior research has documented mentions of co-use of alcohol and tobacco on Twitter,34,35 we are unaware of any published studies specifically examining discussions of tobacco use within intoxication-related contexts of alcohol use on Twitter. This study aimed to use a sample of alcohol- and tobacco-related tweets to characterize social media posts concerning tobacco use within intoxication-related contexts of alcohol use and to identify themes that will inform public health messaging in this milieu (e.g., increased susceptibility to tobacco use when under the influence of alcohol, alcohol intoxication-related contexts impacting tobacco cessation attempts).

Methods

Data Collection

Research procedures were deemed exempt by the first author’s Institutional Review Board. Data were collected in real-time from the Twitter Application Programming Interface using the open-source RITHM software.36 The scope of data for the current project spanned one calendar year from January 1, 2019 through December 31, 2019; however, there were three days in April and six days in December which were missing due to system downtime. All public tweets that contained text-matched provider filter keywords were included in the sample. Consistent with prior work,30,37,38 tobacco-related keywords in this domain included vape, vapes, vaper, vaping, vaped, ecig, ecigs, cigarette, cigarettes, cig, cigs, nicotine, tobacco, smoking, juul*, and puffbar. This resulted in capturing 19,378,934 unique tweets (excluding 36,323,456 “re-tweets” of original tweets). To narrow the scope of data for relevance to intoxication-related contexts of alcohol use, a second list of keyword filters was employed, including blackout*, blacked out, drunk, hammered, hangover, hungover, shitfaced, tipsy, wasted.29,39 Other alcohol-related terms, such as types and brands were excluded in order to focus the results on likely contexts of alcohol use and intoxication, rather than general discourse about alcohol. This narrowed the dataset to 78,235 original tweets that matched both tobacco and alcohol use or intoxication contexts. Activity was relatively stable over time, with a mean of 219 tweets per day (SD = 123, median = 198, IQR: 174–225). The three peak days of activity had 980 (11/25/2019), 1108 (12/17), and 1681 (10/15) tweets, which combined to less than 5% of the overall sample. While allowing tolerance for these common fluctuations in Twitter activity (e.g., a related topic is promoted or goes “viral”), the data did not appear to be heavily biased by such events. Given these characteristics, we proceeded with simple random sampling as the most parsimonious way to generate a naturalistic subsample for annotation. To reduce the scope of data for the feasibility of human annotation, a 2% subsample was drawn at random from the data and these 1,564 tweets were included for analysis.

Codebook Development and Coding Procedures

To facilitate human coding, tweets were exported to a spreadsheet that included the content of the original tweet, quoted content, image links, as well as a url link to view the publicly available original tweet on Twitter. Initial codebook development was based on adaptations from prior studies exploring alcohol and tobacco use on Twitter29,30 and included the following: (1) relevance—main focus of the tweet is related to both tobacco use and alcohol intoxication-related contexts, (2) user sentiment (positive or negative) toward alcohol use/tobacco use/co-use of alcohol and tobacco, (3) personal/proximal experience—a reference to something the tweeter saw him/herself or something that happened to someone the tweeter knows, (4) commercial—selling, marketing, or advertising alcohol and/or tobacco products, and (5) news—news headlines or stories related to alcohol and/or tobacco products. We also developed two additional content codes based on prior examinations of the role of alcohol use on increased susceptibility to tobacco use and failed tobacco cessation attempts.11,15,16Table 1 includes detailed descriptions of coding variables with exemplar Tweets. A sample of 100 tweets were pilot coded by the lead author and two independent annotators, disagreements were adjudicated, and thematic trends were discussed among the study team. Over three iterations of annotation and adjudication, codebook definitions were refined and consensus was reached on final coding definitions. In the final round of independent double-coding, annotators reviewed 1,564 tweets and inter-rater agreement was calculated using Cohen’s Kappa coefficient.40 Kappa values for all included variables ranged from 0.68 to 0.99 (average Cohen’s κ = 0.80), indicating a strong level of agreement between coders. Discrepancies between coders were discussed until an agreement was reached. The lead author adjudicated disagreements in cases where coders could not reach an agreement.

Table 1.

Definitions for Categorical Coding Variables and Example Tweets

| Code Sub-code | N (%) | Definition | Example content |

|---|---|---|---|

| User Sentiment | |||

| Pro-alcohol | 597 (80.6%) | Expresses pro-alcohol sentiment or indicates the user enjoys alcohol. | • “[I want to get drunk and smoke cigarettes and talk about life] and conspiracy theories…is that too much to ask for.” |

| Anti-alcohol | 144 (19.4%) | Expresses anti-alcohol sentiment or indicates the user is not supportive of alcohol use. | • “Some drunk [guy spit] at my cashier because we ran out of his CIGARETTES AND I ALMOST LOST MY FUCKING JOB” |

| Pro-tobacco | 565 (76.2%) | Expresses pro-tobacco sentiment or indicates the user enjoys tobacco use. | • “I'm putting a stop on drinking so much, even if I don't get drunk... Cigarettes will remain my friend, though.” |

| Anti-tobacco | 176 (23.8%) | The tweet expresses anti-tobacco sentiment or indicates the user is not supportive of tobacco use. | • “[Vaped] since I was 15 because I thought it was cool. In the end, [a nicotine addiction resulted in] bronchitis every month. I'm not about to rely on this [anymore] and not even when I'm drunk and just doing it "socially". |

| Pro-co-use | 554 (74.8%) | Expresses pro-favorable sentiment regarding co-use of alcohol and tobacco or indicates the user enjoys co-using alcohol and tobacco. | • “this [guy] was so drunk [that he] passed out, [but then] he got up just to hit his juul...i had to cheer for him it was so funny whew” |

| Anti-co-use | 187 (25.3%) | Expresses critical sentiment regarding co-use of alcohol and tobacco or indicates the user is not supportive of co-use of alcohol and tobacco. | • I smoked cigarettes ONE time when I was drunk when I was …really young…Swore I would never do it again because I couldn't get the taste out of my mouth no matter how much I brushed. I still haven't smoked a cigarette since and I'm thankful for that experience.” |

| Content Codes | |||

| Personal or proximal experience | 578 (78.0%) | Contains reference to something the tweeter experienced him/herself (uses first person pronouns such as I, me) or something that happened to someone the tweeter knows (my friend/brother/sister) | • “When I'm drunk I basically drink juul pods…[I need to] set up a juul fund” • “As a young [guy] (18) with a [younger brother who is 14], our generation's hedonist tendencies are irredeemable…my friends think it's strange that I don't [participate] in it. My brother has already [vaped, been blackout drunk, smoked weed many time, had sex, and more.]” |

| Increased susceptibility to tobacco use when using alcohol | 71 (9.6%) | Contains a reference to increasing tobacco use when under the influence of alcohol or exclusively using/purchasing tobacco products only when under the influence of alcohol. | • “Why…do i love cigarettes when i'm drunk?...cigarettes taste [horrible] and [the smell of them makes me sick when I’m sober], but [when I’m drunk I could smoke a pack]… plus i have asthma so my lungs are already dead”. • “I was drunk enough to smoke cigarettes last night but [I didn’t] throw up so I'm calling it a success” • “… if you see me this weekend [please] do not offer me [your] vape !!! may be drunk enough to say yes but sober me would say no…so support me by not offering me a hit…”; |

| Alcohol undermining tobacco cessation attempts | 15 (2.0%) | Contains a reference to alcohol use contributing to a failed attempt at quitting tobacco use. | • “[Michael] gave me his juul last night….then i bought more pods when i was drunk even [though] I ‘quit’ months ago.....”. • “[haha I gave] up cigs lets see how long this lasts [when] I’m drunk”. • “[I] ruined my streak for not smoking. took one.. hit off my [friend’s] cigarette when i was drunk. was it worth it? yes and no. yes because it reminded me ... how bad it tastes. no because of obvious reasons haha” |

Measures

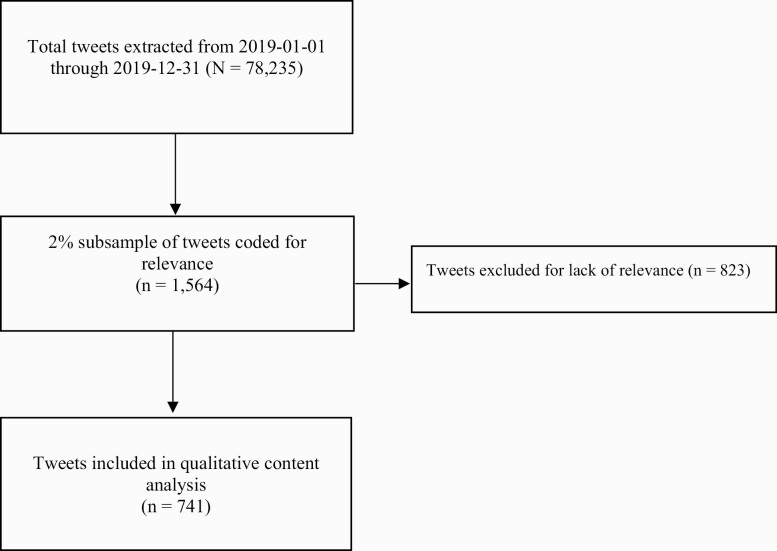

Tweets were first coded for relevance to our study aims; original tweets in which the main focus was relevant to both alcohol and tobacco were included for further analysis. Tweets were excluded if intoxication keywords were used in a context unrelated to alcohol use (e.g., wasted—“I’ve wasted two hours of smoking time..sleeping!”). Further, tweets were deemed irrelevant and excluded if they referred to co-use of alcohol and cannabis, as opposed to co-use of alcohol and tobacco. This noise was associated with the “smoking” tobacco-related keyword, as many tweets used this term to describe cannabis use. Thus, for cannabis-related tweets that were excluded, we coded for whether various contexts related to co-use of alcohol and cannabis were present (i.e., use of cannabis when drunk/intoxicated, use of cannabis to relieve alcohol-related hangovers, comparison of pros/cons of alcohol use and cannabis use). The inclusion and exclusion process for our sample of tweets is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Systematic process for selection of tweets included in final content analysis.

741 tweets were included in subsequent content coding. For each substance use context (i.e., alcohol use, tobacco use, co-use of alcohol and tobacco), sentiment could be classified as favorable (e.g., pro-alcohol) or unfavorable/critical (e.g., anti-alcohol). Also, tweets were coded for news (news headlines or stories related to alcohol and/or tobacco) and commercial content (selling, marketing, or advertising alcohol and/or tobacco products). Additional dichotomous content codes (yes/no) explored whether the tweet referenced increased susceptibility to tobacco use when under the influence of alcohol, as well as the presence of mentions of alcohol use undermining tobacco cessation attempts.

Analytical Plan

A content analysis approach was used, in which we captured both quantitative descriptions of the data and representative qualitative examples for coded variables. Frequencies and percentages of dichotomous variables were assessed to determine the overall proportion of constructs in the data. Emergent themes within constructs were noted by annotators and discussed at regular intervals among the study team. Themes were synthesized into descriptive narratives with relevant examples. In some cases, exemplar tweets needed to be paraphrased to prevent the identification of individual Twitter users. For transparency, any such re-phrasing has been indicated using brackets within quoted text.

Results

Of the 741 relevant tweets included in final analyses, very few included commercial (1.1%) or news-related content (1.1%), as the majority of tweets (78%) were representative of an individual’s personal or proximal experiences with alcohol and tobacco. The vast majority of posts expressed positive sentiment toward alcohol (80.6%), tobacco (76.2%), and co-use of alcohol and tobacco (74.8%). Table 1 includes frequencies of dichotomous constructs as well as their definitions and exemplar tweets. Several salient themes emerged from the data, both within and across categorical codes. Five of these emergent themes, in particular, were relevant to the aims of the study: (1) co-use of alcohol and tobacco is pleasurable, (2) comparing alcohol versus tobacco use, (3) concerns about underage use, (4) increased susceptibility to tobacco use when intoxicated, and (5) alcohol disrupting tobacco cessation attempts. Each of these themes are described separately below.

Co-use of Alcohol and Tobacco is Pleasurable

A common theme related to favorability toward co-use of alcohol and tobacco was equating having fun with getting drunk and smoking (e.g., “the summer was [incredible]… i was getting drunk and smoking and having fun with my friends...”). Also, individuals often mentioned experiences of increased pleasure associated with the intoxicating effects of combining alcohol and nicotine (e.g., “can someone tell me why nicotine is so fire when you’re drunk”).

Comparing Alcohol Versus Tobacco Use

Among tweets that expressed negative sentiment toward co-use of alcohol and tobacco, a common theme was comparison of the negative effects of alcohol and tobacco. Some individuals expressed favorability toward tobacco use, but were critical of alcohol use behaviors (e.g., “y’all [hate] on me for juuling but [I don’t go out] every weekend getting blackout”). In many of these cases, tobacco users expressed disdain for alcohol use, emphasizing alcohol-related consequences associated with harmful alcohol use, such as drunk driving and domestic violence (e.g., “… a few people die from vaping and it’s a ‘crisis’… how many die from drunk driving? Nothing preventative done there”; “…some people get aggressive and abusive when they’re too drunk and can cause lots of harm and trouble to people around”). On the other hand, many individuals supportive of risky drinking behaviors expressed disapproval of tobacco use, often times expressing regret for having smoked when under the influence of alcohol (e.g., “y did drunk me smoke cigs I feel gross now”). These individuals appear to downplay the seriousness of the use of their preferred substance by highlighting the negative aspects of other substances.

Underage Use

Another emerging theme was mentioning unhealthy substance use among underage individuals. Numerous tweets expressed personal testimonies, in which the person tweeting referred to consequences experienced in association with underage substance use (e.g., “[Vaped] since I was 15 because I thought it was cool. In the end, [a nicotine addiction resulted in] bronchitis every month. I’m not about to rely on this [anymore] and not even when I’m drunk and just doing it ‘socially’. # TrashTheVapes”). Others expressed concern for underage family member’s unhealthy behaviors (e.g., “my 11 years old cousin [posts statuses and videos] of him getting drunk and with girls [smoking and drinking and flirting with everyone] like boy you’re 11”; “As a young [guy] (18) with a [younger brother who is 14], our generation’s hedonist tendencies are irredeemable…my friends think it’s strange that I don’t [participate] in it. My brother has already [vaped, been blackout drunk, smoked weed many time, had sex, and more.]” Moreover, many tweets expressed concern about the perceived normalization of engaging in alcohol and tobacco use as an adolescent (e.g., “… influencers are a mess getting drunk at 13 years old and [vaping, going to clubs, and having sex] so early on holy shit there’s a dark side to this stuff”).

Increased Susceptibility to Tobacco Use When Intoxicated

Almost one out of every ten tweets (9.6%) contained a reference to increased susceptibility to use tobacco when under the influence of alcohol. For example, a major theme was the use of cigarettes and e-cigarettes only when drunk, often times in spite of disliking many aspects related to tobacco use, such as the taste, smell, and/or health effects (e.g., “Why…do i love cigarettes when i’m drunk?...cigarettes taste [horrible] and [the smell of them makes me sick when I’m sober], but [when I’m drunk I could smoke a pack]… plus i have asthma so my lungs are already dead”). In such instances, many individuals described craving nicotine when intoxicated as a contributing factor (e.g., “Idk why I always crave nicotine when I’m drunk”). Moreover, individuals who had previously switched from using combustible cigarettes to e-cigarettes were tempted to smoke cigarettes when intoxicated (e.g., When I started smoking my juul I never intended on quitting cigs but now the only time I ever crave cigs is when I’m drunk. They smell and taste so bad to me now”). Similarly, another theme related to increased vulnerability to tobacco use when intoxicated among presumably regular tobacco users was using significantly more tobacco products than usual when drunk (e.g., “I have this bad habit of chain smoking when drunk”; “When I’m drunk I basically drink juul pods…[I need to] set up a juul fund”). Lastly, many individuals described borrowing or obtaining tobacco products from peers during drinking events, expressing regret and often asking friends to help them refuse tobacco use when losing inhibitions during binge-drinking episodes (e.g., “… if you see me this weekend [please] do not offer me [your] vape!!! may be drunk enough to say yes but sober me would say no…so support me by not offering me a hit…”; “My dirty habit [is to ask for cigarettes when I’m drunk] If you ever drink with me and see me doing this, stop me LOL”).

Alcohol Disrupting Tobacco Cessation Attempts

While there were relatively few instances of individuals discussing the role of alcohol undermining tobacco cessation attempts (2.0%), these sentiments were present. Most of these tweets referenced having quit tobacco use in the past, but having a relapse while intoxicated, such as, “Sometimes you quit smoking 9 months ago but sometimes you need to get drunk and smoke a pack of cigarettes with the person you love and enjoy [music].” Some of these instances also contained references to buying surplus tobacco products while drunk, potentially leading to continued tobacco use after the acute drinking episode (e.g., “[Michael] gave me his juul last night….then i bought more pods when i was drunk even [though] I ‘quit’ months ago.....”). In other cases, some individuals referred to using future drinking bouts as an excuse to go back to smoking (e.g., “[haha I gave] up cigs lets see how long this lasts [when] I’m drunk”).

Discussion

In line with prior research exploring drinking- and tobacco-related chatter on Twitter,29,30 user sentiment was overwhelmingly positive towards both alcohol and tobacco use. Also, the majority of tweets included in this sample expressed favorable attitudes for the co-use of alcohol and tobacco, often equating enjoyment/fun with drinking and smoking and reporting increased pleasure when combining alcohol with nicotine. Almost 10% of tweets contained references to increased susceptibility to tobacco use when intoxicated, consistent with previous studies examining the impact of alcohol use and bar attendance on smoking and quit attempts.15,16 Similar to prior survey-based studies,16 alcohol appeared to undermine tobacco cessation attempts. For instance, individuals disclosed instances in which they had quit smoking for prolonged periods of time but lapsed back to smoking during an acute intoxication episode. It is unknown whether such instances led to the reinitiation of long-term tobacco use. Others suggested that they were going to quit smoking, but that they might use getting drunk as an excuse to smoke again.

One of the themes observed in the data was increased likelihood of tobacco use when intoxicated, even among tweets from individuals who appear to be non-regular smokers, and actively report dislike for tobacco products. Specifically, individuals who appear to be non-regular smokers and expressed negative sentiment towards tobacco use (e.g., hate the smell or taste), reported using tobacco products only when intoxicated and expressed regret for partaking in smoking occasions. Many of these individuals noted increased cravings for nicotine when under the influence of alcohol. Some even asked for peers to help refuse tobacco products when in drinking contexts. Similarly, individuals who appear to be regular tobacco users mentioned instances in which they smoked or vaped much more than usual when under the influence of alcohol (e.g., chain smoking). These findings warrant further investigation as to (a) why persons who appear to not regularly partake in tobacco use may experience increased desire to do so when intoxicated, and (b) why individuals who appear to be regular tobacco users increase smoking and vaping behaviors when intoxicated. While prior lab-based studies have noted that alcohol increases cravings to smoke and smoking self-administration due to common reward pathways in the brain, further investigation is warranted into alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in individuals with diverse drinking and smoking histories and across varying ranges of blood alcohol concentrations.39 Additionally, protective behavioral strategies have been shown to reduce alcohol-related harms experienced from drinking among young adults.41 Given the relationship between acute intoxication and increased susceptibility to use tobacco, further investigation is warranted to better understand if drinking-related protective behavioral strategies can also confer benefits related to abstaining from or reducing tobacco use when engaging in alcohol consumption. Moreover, understanding the contextual factors influencing the use of protective behavioral strategies,42 and how these impact tobacco use across varying environments, will also be illuminating.

Another concerning finding was that there were common references to underage participation in alcohol and tobacco-related behaviors. We were able to characterize example tweets mentioning such instances directly (i.e., including an age), often through a lens of personal or proximal experience. While we were not able to account for the ages of those who posted the tweets, it is likely that many of the tweets in our sample were posted by underage persons given underage individuals post and engage with alcohol and tobacco marketing content on social media,19,31 and exposure to such content is associated with increased use of these substances.21,43 Moreover, the glamorization of heavy drinking behaviors and tobacco use on social media, especially among peers, can contribute to normative perceptions of such behaviors.17,44,45 While we suggest stricter regulations be put forth on social media in order to offset underage exposure to such content (e.g., age verification), we realize this may not be a reality. Thus, alcohol- and tobacco-media literacy campaigns should be prioritized in order to moderate the effects of such exposures among youth on their current or future use of alcohol and tobacco.

Overall, the findings of this study point to a need for programming to educate individuals on the elevated health risks associated with dual use of alcohol and tobacco, as well as the increased vulnerability for tobacco use when under the influence of alcohol. Given the large presence of content on Twitter that is supportive of the co-use of alcohol and tobacco and the wide reach of the social media platform, Twitter offers a potentially valuable resource for alcohol and tobacco counter-advertising and media literacy interventions. Alcohol and tobacco media literacy interventions have demonstrated efficacy in reducing youth intentions to use alcohol and tobacco in the future,46 yet such efforts must constantly be adapted to the ever-evolving media landscape. Highly effective and innovative tobacco counter-advertising social media campaigns do exist.47 For example, the Truth Initiative’s “Ready to Ditch Juul” campaign designed to encourage and assist young people to quit vaping has achieved great success. The campaign is an excellent example of building off of the cultural preference for social media use among youth in an entertaining and engaging way in order to reach them with smoking cessation resources. For instance, Truth hosted a trick shot challenge on TikTok, in which users were asked to record and post a video of themselves “ditching” their Juul devices in creative ways (e.g., throwing the device into a cup of water from a second floor balcony). Along with this video content, users were presented with tobacco cessation resources, including encouragement to text “DITCHVAPE to 88709” to sign up for the “This is Quitting” mobile program created to help young people quit vaping.48 To date, over 250,000 youth and young adults have signed up for the program.48 Nevertheless, highly successful tobacco cessation efforts like those by the Truth Initiative may confer added benefit by incorporating alcohol counter-advertising elements and by educating those interested in tobacco cessation about the association between increased susceptibility to tobacco use when consuming alcohol and the role of alcohol in undermining tobacco cessation attempts. Such interventions may consider engaging around salient themes (e.g., co-use is pleasurable) and narratives brought forth through the present analysis.

Limitations

This study was not without limitations. First, our findings based on data from Twitter are not necessarily generalizable to populations of non-Twitter users or to other social media platforms. Second, as with any qualitative content analysis, coding for alcohol- and tobacco-related categorical variables was subjective in nature. In order to account for this limitation, our initial codebook development was based on adaptations from prior studies exploring alcohol and tobacco use on Twitter.29,30 Also, we independently double-coded all tweets and discussed differences until agreement was reached—consulting with the lead author when necessary. We also assessed Cohen’s Kappa values to ensure sufficient interrater reliability. Third, our alcohol-related filter keywords were specifically related to alcohol intoxication contexts. Therefore, findings based on these data may not be generalizable to broader co-use of alcohol and tobacco posts on Twitter (e.g., light drinking, experimental drinking). Despite these limitations, this study addresses a gap in the literature by providing context to patterns of co-use of alcohol and tobacco use, specifically with regard to the role of alcohol intoxication on tobacco use behaviors. More research is needed to better understand ways in which Twitter can be used as a health intervention tool in such contexts.

Conclusions

This study highlights that sentiment towards the co-use of alcohol and tobacco on Twitter is largely positive. Often times, having fun was equated with drinking and smoking, and experiences of increased pleasure associated with the combined effects of alcohol and nicotine were reported. Another common theme was the mentioning of increased susceptibility to tobacco use when intoxicated. In some cases, non-regular tobacco users reported having no desire to use tobacco when sober but reported strong cravings to smoke or vape when consuming alcohol. In other cases, regular tobacco users reported using markedly higher quantities of tobacco products when under the influence of alcohol. Moreover, there was evidence for the role of alcohol undermining smoking cessation attempts; individuals who had quit smoking or vaping for prolonged periods of time reported reinitiating tobacco use during acute intoxication episodes, often expressing regret for having done so. There is a need to educate individuals on the elevated health risks associated with dual use of alcohol and tobacco, as well as the increased vulnerability for tobacco use when under the influence of alcohol. Also, investigation is warranted to better understand how Twitter can be utilized to leverage alcohol and tobacco counter-advertising and media literacy interventions. While social media-based tobacco cessation interventions like the Truth Initiative’s “Ditch the Juul” campaign have become widely disseminated and demonstrate great potential to change tobacco use behaviors, such campaigns may achieve greater success by including alcohol-focused components designed to educate participants about the association between increased susceptibility to tobacco use when consuming alcohol and the role of alcohol in undermining tobacco cessation attempts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

None.

Contributor Information

Alex M Russell, Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Jason B Colditz, Center for Research on Media, Technology, and Health, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Adam E Barry, Department of Health and Kinesiology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA.

Robert E Davis, Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Shelby Shields, Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Juanybeth M Ortega, Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Brian Primack, Department of Health, Human Performance and Recreation, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA.

Funding

BP and JC were supported by an award from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA225773). This work used the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by National Science Foundation grant number ACI-1548562. Specifically, it used the Bridges system, which is supported by NSF award number ACI-1445606, at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Office of the Surgeon General (US). Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. SAMSHA. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. HHS Publ No PEP19-5068, NSDUH Ser H-54. 2020;170:51–58. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed March 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Excessive Drinking is Draining the U.S. Economy . 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/features/excessive-drinking.html Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 4. Cullen KA, Gentzke AS, Sawdey MD, et al. e-Cigarette use among Youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2095–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students-United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(12):1–22.30629574 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohn AM, Johnson AL, Rath JM, Villanti AC. Patterns of the co-use of alcohol, marijuana, and emerging tobacco products in a national sample of young adults. Am J Addict. 2016;25(8):634–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Littlefield AK, Gottlieb JC, Cohen LM, Trotter DR. Electronic Cigarette use among college students: Links to gender, race/ethnicity, smoking, and heavy drinking. J Am Coll Health. 2015;63(8):523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rothrock AN, Andris H, Swetland SB, et al. Association of E-cigarettes with adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking-drunkenness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2020;46(6):684–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harrison EL, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nondaily smoking and alcohol use, hazardous drinking, and alcohol diagnoses among young adults: findings from the NESARC. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(12):2081–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Verplaetse TL, McKee SA. An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43(2):186–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thrul J, Gubner NR, Tice CL, Lisha NE, Ling PM. Young adults report increased pleasure from using e-cigarettes and smoking tobacco cigarettes when drinking alcohol. Addict Behav. 2019;93:135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 ; 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639. Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 13. United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Health consequences of smoking—50 Years of progress a report of the surgeon general; 2014.

- 14. Viner B, Barberio AM, Haig TR, Friedenreich CM, Brenner DR. The individual and combined effects of alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking on site-specific cancer risk in a prospective cohort of 26,607 adults: results from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30(12):1313–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jiang N, Ling PM. Impact of alcohol use and bar attendance on smoking and quit attempts among young adult bar patrons. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):e53–e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang R, Li B, Jiang Y, Guan Y, Wang G, Zhao G. Smoking cessation mutually facilitates alcohol drinking cessation among tobacco and alcohol co-users: A crossectional study in a rural area of Shanghai, China. Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyle SC, LaBrie JW, Froidevaux NM, Witkovic YD. Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addict Behav. 2016;57:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huang GC, Soto D, Fujimoto K, Valente TW. The interplay of friendship networks and social networking sites: longitudinal analysis of selection and influence effects on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e51–e59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barry AE, Bates AM, Olusanya O, et al. Alcohol Marketing on Twitter and Instagram: Evidence of directly advertising to Youth/Adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(4):487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jernigan D, Noel J, Landon J, Thornton N, Lobstein T. Alcohol marketing and youth alcohol consumption: a systematic review of longitudinal studies published since 2008. Addiction. 2017;112 Suppl 1:7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lobstein T, Landon J, Thornton N, Jernigan D. The commercial use of digital media to market alcohol products: a narrative review. Addiction. 2017;112 Suppl 1:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soneji S, Yang J, Knutzen KE, et al. Online tobacco marketing and subsequent tobacco use. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20172927. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barry AE, Padon AA, Whiteman SD, et al. Alcohol advertising on social media: Examining the content of popular alcohol brands on Instagram. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(14):2413–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pew Research Center. Social Media Fact Sheet . 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ Accessed March 30, 2021.

- 25. Barry AE, Valdez D, Padon AA, Russell AM. Alcohol Advertising on Twitter—A Topic Model. Am J Heal Educ. 2018;49(4):256–263. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Colditz JB, Welling J, Smith NA, James AE, Primack BA. World Vaping Day: Contextualizing vaping culture in online social media using a mixed methods approach. J Mix Methods Res. 2019;13(2):196–215. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boyd D, Golder S, Lotan G. Tweet, tweet, retweet: Conversational aspects of retweeting on twitter. Proc Annu Hawaii Int Conf Syst Sci. 2010:1–10. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2010.412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pew Research Center. News Use Across Social Media Platforms in 2020 . 2021. https://www.journalism.org/2021/01/12/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-in-2020/ Accessed March 15, 2021.

- 29. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ, Bierut LJ. “Hey Everyone, I’m Drunk.” An evaluation of drinking-related Twitter Chatter. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76(4):635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sidani JE, Colditz JB, Barrett EL, Chu KH, James AE, Primack BA. JUUL on Twitter: Analyzing tweets about use of a new nicotine delivery system. J Sch Health. 2020;90(2):135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chu KH, Colditz JB, Primack BA, et al. JUUL: Spreading online and offline. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(5):582–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allem JP, Escobedo P, Chu KH, Soto DW, Cruz TB, Unger JB. Campaigns and counter campaigns: reactions on Twitter to e-cigarette education. Tob Control. 2017;26(2):226–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazard AJ, Wilcox GB, Tuttle HM, Glowacki EM, Pikowski J. Public reactions to e-cigarette regulations on Twitter: a text mining analysis. Tob Control. 2017;26(e2):e112–e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Allem JP, Dharmapuri L, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Cruz B. Hookah-related posts to twitter from 2017 to 2018: Thematic analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(11):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allem JP, Ferrara E, Uppu SP, Cruz TB, Unger JB. E-Cigarette surveillance with social media data: Social Bots, emerging topics, and trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(4):e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Colditz JB, Chu KH, Emery SL, et al. Toward Real-Time infoveillance of Twitter health messages. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(8):1009–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sidani JE, Colditz JB, Barrett EL, et al. I wake up and hit the JUUL: Analyzing Twitter for JUUL nicotine effects and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:6–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Myslín M, Zhu SH, Chapman W, Conway M. Using twitter to examine smoking behavior and perceptions of emerging tobacco products. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Riordan BC, Merrill JE, Ward RM. “Can’t Wait to Blackout Tonight”: An analysis of the motives to drink to blackout expressed on Twitter. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(8):1769–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pearson MR. Use of alcohol protective behavioral strategies among college students: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1025–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barry AE, Goodson P. Contextual factors influencing U.S. college students’ decisions to drink responsibly. Subst Use Misuse. 2012;47(10):1172–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cavazos-Rehg P, Li X, Kasson E, et al. Exploring how social media exposure and interactions are associated with ENDS and Tobacco use in adolescents from the PATH Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(3):487–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Moreno MA, Whitehill JM. Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Res. 2014;36(1):91–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Elmore KC, Scull TM, Kupersmidt JB. Media as a “Super Peer”: How Adolescents interpret media messages predicts their perception of alcohol and tobacco use norms. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(2):376–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kupersmidt JB, Scull TM, Benson JW. Improving media message interpretation processing skills to promote healthy decision making about substance use: the effects of the middle school media ready curriculum. J Health Commun. 2012;17(5):546–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Truth Initiative. New TikTok Challenge Kicks Off National Truth® Campaign . 2020. https://truthinitiative.org/press/press-release/new-tiktok-challenge-kicks-national-truthr-campaign-underscoring-young-peoples Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 48. Truth Initiative. This is Quitting . 2020. https://truthinitiative.org/thisisquitting Accessed April 21, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.