Abstract

A cellular automaton (CA) depicting the dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic, is set up. Unlike the classic CA models, the present CA is an enhanced version, embodied with contact tracing, quarantine and red zones to model the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic. The incubation and illness periods are assimilated in the CA system. An algorithm is provided to showcase the rules governing the CA, with and without the enactment of red zones. By means of mean field approximation, a nonlinear system of delay differential equations (DDE) illustrating the dynamics of the CA is emanated. The concept of red zones is incorporated in the resulting DDE system, forming a DDE model with red zone. The stability analysis of both systems are performed and their respective reproduction numbers are derived. The effect of contact tracing and vaccination on both reproduction numbers is also investigated. Numerical simulations of both systems are conducted and real time Covid-19 data in Mauritius for the period ranged from 5 March 2021 to 2 September 2021, is employed to validate the model. Our findings reveal that a combination of both contact tracing and vaccination is indispensable to attenuate the reproductive ratio to less than 1. Effective contact tracing, quarantine and red zones have been the key strategies to contain the Covid-19 virus in Mauritius. The present study furnishes valuable perspectives to assist the health authorities in addressing the unprecedented rise of Covid-19 cases.

Keywords: Covid-19, Cellular automaton, Red zones, Contact tracing, Delay differential equation, Validation

1. Introduction

Since first identified, the epidemic scale of the recently emerged novel coronavirus, Covid-19 in Wuhan, China, has increased rapidly, with cases arising across China and other countries around the globe. To date, 221 countries and territories around the world are affected by the Covid-19 [1]. Containment measures to prevent the spread of the disease include the closure of schools and universities, cancellation of mass gatherings, namely sport events and introducing work-from home arrangements with the aim of reducing individual contacts [2]. Red zones, strict quarantine, isolation, curfews and lockdown have been deployed in most countries. The WHO guidelines for the control of Covid-19 stress on three crucial components of an effective strategy: test, trace and isolate [3]. This approach has become one of the key public health tools to circumvent Covid-19 globally. It is perceived that contact tracing is of high importance in the early stages to contain spread [4]. However, it is not so sufficient when the transmission rate is high and the network of contacts is large [5]. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the world has witnessed one of if not the most rapid vaccine development [6]. In addition to preventive measures such as quarantine, social distancing and masks, vaccination is the most vital preventive measure to contain the spread of the Covid-19 virus [7], [8], [9]. Nevertheless, the emergence of new variants triggered waves of the infection. Accordingly, the administration of booster doses has become sine qua non in order to sustain immunity against the virus [10], [11]. Yet, it is noteworthy to point out that the findings of [12] revealed that the likelihood of a reinfection, up to 1 year post a previous infection of Covid-19 and the rate of vaccine breakthrough infections are low. Hence, in this work, it is assumed that vaccination is 100% effective. Thus, the number of vaccinated individuals reintegrating the susceptible category in a given population, is considered as comparatively negligible [12]. Quarantine of individuals restricts the activities and separates individuals who have been exposed to an infected person [3]. Thus, symptomatic individuals can be identified and secondary infections are prevented within the population. Isolation uncouples the infected individuals from others. Another potent containment measure expeditiously adopted during the second wave of infections is the enforcement of red zones [13].

Mathematical modelling has figured prominently in decision making in the control and suppression of the Covid-19 spread [14]. Several mathematical models of Covid-19 have been developed with the goal of estimating and analysing the outbreak [13], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Mauritius was hit by the Covid-19 virus on 18 March 2020, trailed by three imported cases. The outbreak quickly evolved from sporadic cases to clusters to local transmission. The proliferation of the virus was controlled within 39 days on 26 April 2020 [19]. However, the second wave of Covid-19 cases sent the country into a second lockdown in March 2021 which lasted for 3 weeks. In anticipation of the second wave of Covid-19, the Mauritian government introduced the red zone strategy. Mauritius has bolstered tracing efforts but has still struggled as case numbers rose during the second wave of infections. Couple with other containment measures, the enactment of red zones has enhanced the efficacy to control the propagation of the virus within the population. The present study aims at modelling the Covid-19 pandemic, using the cellular automata (CA) approach. The highlight of this article is the formulation of a novel CA model, embodied with contact tracing, quarantine, red zones and vaccination. To the best of our knowledge, the CA model proposed in the current work is a first of its kind since including the aforementioned features increase the complexity of the model. Additionally, in order to gain better insights into the dynamics of the spread of the Covid-19, a mean field approximation of the CA is carried out. A nonlinear system of delay differential equations (DDE) is yielded, which proves to be the most coherent in the sense that delays are incorporated, accounting for the changes in the evolution of the virus, the social behaviours of individuals and the effect of measures enacted. The paper is next channelled as follows: a brief overview of cellular automata is provided in Section 2. The CA model is set up and the rules governing the system with and without red zones are elucidated in Section 3. Section 4 presents the numerical simulations of the CA model. A mean field approximation of the CA model is performed in Section 5, yielding a DDE system. The analysis of the resulting system is conducted in Section 6. Red zone is incorporated in the model and its analysis is presented in Section 7. The numerical investigations of the DDE model are depicted and discussed in Section 8. In Section 8.5, Covid-19 data for Mauritius is adopted to validate the model and scenarios under different control strategies are simulated. The concluding remarks and the future scope of the model are eventually provided in Section 9.

2. Overview of cellular automata

A cellular automaton (CA) is a collection of cells arranged in a grid that evolve through a finite number of discrete time steps, , according to a set of predefined rules. These rules can either be deterministic or stochastic. Each cell of the grid can be in one state at a time. The next state of each cell depends on the state of the current cell and states of its neighbourhood. The most commonly types of neighbourhood used are the Von Neumann and Moore neighbourhood [20]. These neighbourhoods can also be extended using a radius around the reference cell. In the relation-based graph-CA (r-GCA) neighbourhood, the connections of each cell, who are far away but close in the relationship of common friends and cliques amongst others, are considered [21]. Contact network is an essential feature to be assimilated into the mathematical modelling of diseases where social interactions take place over large-scale areas, which enhances the measure of infection risk within the community [22]. Moreover, as stipulated in [23], the inhomogeneity in the contact network of each individual influences the dynamics of the proliferation of the disease. Thus, in the present context, the concept of the relation-based graph-CA (r-GCA) neighbourhood is used. [24] reveals that the inclusion of time delay in the study of epidemiology is an important aspect as it has a substantial impact on the number of infected individuals. In order to describe the dynamics of the pandemic, in the current work, delays are incorporated to take into account the incubation period of quarantined individuals and the illness time of the infected, respectively. Moreover, the implementation of red zone in a given population points out the dynamic suppression of connections lying outside the red zone. Therefore, in contrast to systems [20] and [21] whereby the connectivity of a given individual is kept fixed, the r-GCA established in the present work has the additional ability to adjust the connectivity of a given cell when red zones are imposed. Accordingly, the r-GCA system set up in [21] is modified in order to embody these features. To date, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind whereby the aforementioned features have been considered in a CA system to model the spread of an infectious disease such as the Covid-19 virus in a given environment. In the following section, the model is set up.

3. The CA model

The CA model consists of a lattice with side and a total size of cells. Each individual is mapped into a cell in the grid that can be in one of the following six states: Susceptible (), Quarantine (), Infected (), Recovered (), Dead () and Vaccinated () individuals. Due to the prevalence of the number of Covid-19 cases in certain areas of a population, the latter regions are declared as red zones. These areas are then categorised as the Susceptible Red Zone () population. Fig. (1 ) pictures the flow diagram of the model. The different arrows represent the possible transitions of individuals within the compartments. Fig. (2 ) illustrates the evolution of an individual tested positive and its contacts who have been identified as Covid-19 positive. It should be emphasized that the dashed lines present in the flow diagram denote that the Susceptible Red Zone category does not exist permanently. Depending on the severity of the proliferation of the disease in these areas, the latter regions are then no longer declared as red zone. As a result, the dashed lines are used to showcase the dynamical evolution of the existence of red zones in the population. The states that are used in the CA model are described in Table 1 and the description of the parameters involved in the model are given in Table 2 .

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the model.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the model. The definition of and are provided in Table 3.

Table 1.

Definition of states and colour code of cells.

| Status of cell | State | Colour |

|---|---|---|

| - Susceptible | 0 | green |

| - Susceptible Red Zone | 0 | green (enclosed in a red circleto represent the red zone area) |

| - Quarantine | 1 | cyan |

| - Infected | 2 | red |

| - Recovered | 3 | purple |

| - Dead | 4 | black |

| - Vaccinated | 5 | blue |

Table 2.

Interpretation of the parameters in the model.

| Symbol | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Growth rate of the susceptible category | 0.003 | |

| Growth rate of the susceptible red zone category | 0.15 | |

| Transmission rate | 0.2 | |

| Contact tracing rate | 0.15 | |

| Rate at which quarantine individuals become infected | 0.1 | |

| Rate at which quarantine individuals returnto the susceptible class | 0.06 | |

| Rate at which quarantine individuals from the susceptiblered zone population become infected | 0.12 | |

| Rate at which quarantine individuals from the susceptiblered zone population return to their class | 0.05 | |

| Recovery rate of infected individuals | 0.07 | |

| Vaccination rate of the susceptible individuals | 0.1 | |

| Vaccination rate of the recovered individuals | 0.012 | |

| Disease-induced death rate | 0.01 | |

| Rate of death of recovered individuals | 0.004 | |

| Rate at which the susceptible red zone populationbecomes susceptible | 0.1 | |

| Natural death rate | 0.01 | |

| The maximum peak of incubation time | 14 days | |

| The maximum peak of illness time | 42 days |

Incubation period is the time elapsed between exposure to the virus and the onset of symptoms and signs of infection. The incubation period is one of the key epidemiological parameters that can determine the appropriate duration of quarantine [25]. An inaccurate estimation of this period may lead to a wrong timing in the implementation of the preventive measures to counter the proliferation of the infection in the population and thereby fuel the spread of the disease, in particular when the number of asymptomatic carriers is significant. Various investigations have confirmed that the incubation period for the Covid-19 virus is about 14 days. In this sense, the quarantine and isolation duration of exposed or suspected cases is set at 14 days [26], [27], [28]. The median time to recovery from Covid-19 varies among patients and research has revealed that the recovery time is estimated to be 2 weeks for patients with mild infection and 3 to 6 weeks for those with serious illnesses [29], [30], [31]. Therefore, in the current study, the maximum illness time is taken as 42 days. In the present r-GCA model, a time delay of 14 time steps, denoted by accounts for the incubation period of quarantined individuals whilst 42 time steps, represented by are taken for the illness time of the infected. The time difference is used to characterise the cycle of viral infection and treatment time.

In this model, the relation-based graph CA neighbourhood [21] is employed to simulate the spread of the disease over the given lattice. Fixed boundary conditions are considered, which are randomly chosen using the rand function in the Matlab software, from the states . The model is run for a certain number of time steps, with the lattice being updated synchronously at each time step, . Each cell ‘interacts’ with cells in its neighbourhood and is updated according to a set of predefined transition rules. Within this model, the stochastic rules for the transitions in the r-GCA are set up according to the following assumption:

-

•

The allowed transitions between the different states are only the ones that obey the flow diagram of the model.

-

•

Owing to the heterogeneity among individuals, each individual shows different resistance, infectivity and infectious range to the disease. However, in the present system, the maximum peak of incubation and illness time is considered to be constant for all individuals.

The ground where the Covid-19 pandemic is proliferating is modelled as a weighted graph whereby each node of the graph stands for an individual and the edge between two nodes represents the connection between the corresponding individuals. More details on the basic theory about CA on graphs can be obtained in [21]. In [32], it is stressed that the network of contacts of an individual is comprised of both close and far connections whereby an individual has a relationship with roommates, family members, neighbours, colleagues at work and casual friends. As such, the network contact of an individual is not fixed within a certain region. Thus, it is of high practical significance to embody the distance factor in the model in order to study the spread mechanism of the infectious disease more accurately. Following the same methodology as introduced in [21], for a population of individuals, the neighbourhood of each cell is represented by an adjacency matrix, as follows:

| (1) |

where

and denotes the set of vertices (or nodes) and is a set of edges (or links) between the vertices, where each edge is an unordered pair of vertices . The distance factor between the nodes and is the weight associated to the edge and is denoted by Generally speaking, the greater the distance, the smaller the influential factor [32]. Hence, the probability of being influenced is inversely proportional to the distance between and Let

| (2) |

Then,

| (3) |

The weight factor, of the cells and is defined as

| (4) |

The weight factors for each cell of the CA form the weight matrix, and is expressed in matrix form as

| (5) |

where is computed using Eq. (4) for and . The weighted neighbourhood matrix, for the given graph includes weight coefficients of individual edges of the directed graph only and is obtained by performing an Hadamard product as follows:

| (6) |

An Hadamard product is used so that other contacts which are not found in the neighbourhood of a given individual is not taken into consideration. The infection probability of individual is then evaluated as follows:

| (7) |

where , representing the infected domain column vector and

represents the total potential infectious risk that infected individuals which are present in the social network of cell , on individual . In addition, each cell of the lattice is tagged with an indicator which is shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Indicator of a cell.

| Cell id | value | value | value | value | value |

Each indicator of a cell has six parameters namely, (1) Cell id which is the current cell denoted by cell , (2) value which takes Boolean value ; 0 means that the cell has not been traced yet and 1 means that the cell has already been traced, (3) value which will also take either 0 or 1 depending upon whether the connectivity of the cell needs to be traced or not, (4) value is the number of days in quarantine, (5) value is the number of days hospitalised and (6) value which takes values from 0 to 14, keeping track of the number of days an infected individual remains untraced in the lattice. The spread of the Covid-19 virus becomes possible only after infected individuals come in contact with healthy/susceptible individuals. The neighbourhood of each cell is randomly selected within the lattice and it is assumed that the number of people which one cell contacts during each time step is the same. It is also assumed that each time a cell is vaccinated, it is not involved in the spread of the disease. In order to incorporate red zones in the CA model, the population is partitioned into zones. The zonal classification determines the areas that will be declared as red zones, following a resurgence of Covid-19 cases in the latter regions. Red zones are executed by blocking the latter regions with a boundary. Cells that are within the boundary do not have access to other cells that are outside the boundary, aiming at containing the spread of the coronavirus within the zone. It is important to note that the red zones imposed are dynamic and are revised fortnightly, contingent on the intensity of the spread in these areas. Consequently, to include the above approach in the CA system, the population is stratified into zones. At each time step, the number of infected cases detected in each zone is computed. If the number of infected cases of a particular zone exceeds a certain value, the latter region is declared as red zone. The contact network of all cells of the latter zone are revised and connections that are outside the area are suppressed instantly, modifying the neighbourhood matrix, given by Eq. (1). The initial configuration of the lattice is set to . Some infected individuals are scattered randomly in the lattice and their states are set to . This system is simulated according to the following algorithm.

3.1. Algorithm of the model

Step 1. Get the input from the user for the value of (the total number of days to simulate the CA model), (the total number of contact tracing conducted daily) and (the maximum number of Covid-19 cases detected in a zone to declare it as red zone).

Step 2. Initialise the time counter and tracing counter to 0.

Step 3. Initialise the value, value, value, value and value of all cells to 0.

Step 4. Vaccinate a proportion of susceptible cells, that is cells and whose value is 0. The value is then set to 1 and .

Step 5. Update all cells tagged with value . If the value of or , the cell is tested: If the cell is tested positive to the virus, the status of the individual changes from to . The value of is set to 1 and the value of is set to 0. Otherwise, if the value of and the individual is tested negative, the status of the individual remains and the value is updated.

Step 6. Update all cells tagged with value . A test is conducted on cells with value being a multiple of 7. If 2 consecutive tests are negative to the virus, the individual recovers. The status of the cell changes from to and the value of is set to 0. Otherwise, the individual remains in the treatment centre and the value of is updated. However, if the value of , the cell is assumed to become inactive. That is, in the present context, we assumed that after being hospitalised for 42 days, the individual dies. The cell changes state from to and the value of is set to 0.

Step 7. Update the tag for the untraced infected cells. If the value of , the value is updated. Otherwise, if the value of , the cell goes to the hospital on his own since the incubation time is 14 days. The value of , and the value of are set to 1 so that its connectivity can be traced. The value of is then set to 0.

Step 8. If the value of a cell is 1, go to Step 11. Else, go to Step 9.

Step 9. A dice is thrown to select an infected cell in the grid, with value 0.

Step 10. The indicator of the selected infected cell is updated. The value, value and value of the cell are set to 1.

Step 11. Identify the connectivity to be traced of the selected cell.

Step 12. A dice is thrown to select only part of the connectivity. The value of the cells from the selected connectivity is set to 1.

Step 13. The selected connectivity is then tested. If the cell is in the susceptible state, that is , the cell is quarantined and with value is set to 1. If the cell is in the infected state, that is , the individual is sent to treatment centres. The value and the value of the infected cell are updated to 1.

Step 14. Check if the number of infected cases in the zones exceeded the . If yes, declare the latter zones as red zones and then go to Step 15. Else, go to Step 16.

Step 15. Suppress all connections of cells that are found outside the zone in order to curb the spread of the disease.

Step 16. If the tracing counter is less than , then go to Step 8.

Step 17. If the time counter is less than , then go to Step 4.

Stop. The algorithm can be summarised in Fig. (2). The algorithm when red zones are not imposed in the population is quite similar to the latter one except that Step 14 and Step 15 are excluded. In the section that tails, some numerical investigations are conducted to showcase the dynamical evolution of the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic in a given population. The effect of implementing red zones are illustrated and discussed.

4. Numerical simulations of the PCA model

The numerical experiments are generated in MATLAB, using a grid of 120 120, depicting the ground whereby the virus is proliferating. The simulation starts with an initial configuration of susceptible and infected sites placed randomly in the lattice, as pictured in Fig. (3 ). The snapshots in Fig. (4 ) clearly show the spread behaviour of the Covid-19 virus in the population, with the effect of red zones and without red zones. The spread patterns in both scenarios unravel the value of classifying certain regions as red zones. The virus is seen to be less dispersed in the lattice when red zones are imposed. The rightmost column of Fig. (4) demonstrates the dynamic of red zones when implemented in the population. When the number of infected cases of a zone exceeds the value, that particular geographical region is delimited as red zone and is illustrated with a red circle. As the pandemic progresses, the measures enforced in these regions are revised. Depending on the prevalence of the virus, the latter areas are no longer declared as red zones and are then encircled by a yellow circle to picture the relaxation of the measures imposed in that region.Fig. (5 ) shows the progression of the number of infected cases with and without the effect of red zones. A remarkable drop of infected cases is perceived as from 200 time steps. Moreover, at the final time step, the number of infected cases eventually declines to 0 when red zones are implemented. It can be seen that without red zones, the disease is still prevailing in the population at the final time step. This numerical experiment firmly evidences that red zones are efficacious in preventing an extensive propagation of the virus in the population. Furthermore, the time taken to slow down the spread of the disease in the population can be predicted. From Fig. (5), it can be seen that after 420 time steps, a Covid free population is noted. Hence, with the present CA model, a swarm of scenarios can be effectuated and through the outcomes, the government can deploy effective strategies to control the pandemic in the most effective way. It needs to underscore that the CA model established in the present study mimics the spread of the disease and captures the multitude of factors that enhances and mitigates the proliferation of the virus in the community. The simulations presented point out the importance of modelling this pandemic with a cellular automaton. Such approach can be very handy and efficient in dealing with real time simulations. With real data for a short period of time, the CA simulations can furnish insights into the pandemic situation across a geographical region for a longer period in the future. To gain some insight into the dynamics of the CA, we now proceed to the construction of approximate equations describing the probabilistic cellular automaton dynamics.

Fig. 3.

Initial status of the CA model with 5 clusters of infected cases and some are randomly scattered in the grid. A total of 288 infected cases are considered in the initial configuration of the model.

Fig. 4.

These figures show the snapshots of the CA dynamics over 500 time steps, illustrating the spread behaviour of the Covid-19 virus at and at on a 120 120 grid. The leftmost column represents the evolution of the virus without the enactment of red zones. The rightmost column depicts the spread of the virus when red zones are imposed in the population. Red zones are shown by red circles and with the relaxation of measures, the latter areas are represented by yellow circles. The parameters used to conduct the simulations are given in Table 2 with the value of and a value of 20.

Fig. 5.

Superimposition of the evolution of infected cases when red zones are implemented in the population (dashed lines) and without red zones (solid lines).

5. Mean field approximation of the CA model

Following [20], density evolution equations corresponding to each category of individuals in the system are derived. The spread of the Covid-19 without the implementation of red zones is culminated to the following system of delay differential equations:

| (8) |

where the time delay denotes the incubation period, that is the period between a susceptible individual being in contact with an infected individual and being infected. The time delay represents the maximum period for an infected individual to either recover from the disease and move to the recovered category or the person die due to the disease. It needs to highlight that the mean field approximation conducted on the r-GCA emanates a nonlinear system of delay differential equations with two delays to depict the dynamics of the spread of the Covid-19.

Remark 1

A susceptible individual, after being in contact with an infected person at instant , becomes infected at instant . The infected class is then fed at the instant by the susceptible infected at the instant . Similarly, the same operation occurs between the classes of the system.

Remark 2

Biologically, in the present model, days and days, representing the incubation period and the maximum peak of illness time respectively.

The initial conditions of system (8) are

| (9) |

where , such that for . denotes the Banach space of continuous functions mapping the interval into , where

It is well known by the fundamental theory of functional differential equations [33], that system 8 has a unique solution ( satisfying the initial conditions given in (15). In the section that tails, the equilibrium points and the reproduction number, of the model are sought. The stability analysis of the system is conducted to appraise the dynamics of the Covid-19.

6. Analysis of the model (8)

6.1. The existence of equilibria and the basic reproduction number,

The equilibrium points are obtained by setting the right hand side of system (8) to zero. It is notable that delay systems and ordinary differential equation systems share the same equilibria. Model (8) is found to have the following equilibria:

-

1.

The Disease Free Equilibrium, (DFE), which represents a population consisting of susceptible and vaccinated individuals, that is a disease free population.

-

2.

The Disease Endemic Equilibrium, (DEE), .

The reproduction number evaluates the speed at which the epidemic disease is capable of propagating in a certain population. Such analysis can provide potential information to policy and decision makers in choosing and enacting different strategies within the progression of the outbreak. can be defined as the average number of individuals from the susceptible category, who are being contaminated by an infected individual. permits to deduce when the Covid-19 is more probable to die out or to persist in a population [34]. In order to scrutinise the equilibria of the system, a basic threshold term for the model is derived, to gauge the transmissibility of the Covid-19. The next-generation matrix approach as outlined in [35] and [34] is employed to compute which is given by

| (10) |

where is the spectral radius of the next-generation matrix with

| (11) |

Remark 3

From Eq. (10), it can be deduced that the reproduction number is highly sensitive to variations in the contact tracing rate, and the vaccination rate, . Hence, efforts must be focused on the increase in the contact tracing rate and the vaccination rate so that This statement is confirmed numerically in Section 8.

In the section that follows, the stability analysis of model (8) is established.

6.2. Stability analysis of the model

In this section, the local stability of the DFE is investigated. In order to examine the behaviour of the DFE, , it is required to compute the Jacobian matrix, , of the system. The Jacobian, , of model (8) about the DFE, is given as

| (12) |

Thus, the characteristic equation of system (8) at is

| (13) |

where is the eigenvalue and the coefficients and for are provided in Appendix B.

In order to analyse the distribution of the characteristic roots of Eq. (13), Lemma 1 found in Appendix B is used. We consider the following three cases:

Case 1:, Case 2: and and Case 3: and and the results obtained for each case are summarised in the following Theorems:

Theorem 1

If, the disease free equilibrium,is locally asymptotically stable when; ie in the absence of the delay.

Theorem 2

Ifandhold, then the DFE,is locally asymptotically stable for alland.

and

Theorem 3

Ifand, then the DFE,is locally asymptotically stable for alland.

The detailed proofs of Theorem 1, Theorem 2 and 3 are provided in Appendix B, Appendix C and E respectively.

Remark 4

For the convenience of analysis, the stability analysis for the disease free equilibrium, when the delays and is not conducted. Additionally, since the disease endemic equilibrium, is quite complex, its stability analysis is not investigated. However, with available data, the existence of is shown numerically and the numerical solutions are explored with the presence of the two delays, which are illustrated later in Section 8.

With the surge of Covid-19 cases, a series of strategies have been quickly deployed by the government to halt its proliferation. The dominant containment measure was the classification of certain areas of a population as red zones. To date, to the best of our knowledge, there exists no study in literature whereby the effect of quarantine, contact tracing and red zone are modelled with a system of delay differential equations. In this view, in the next section, model (8) is modified to embody the compartment of the red zone population.

7. Incorporating Red Zone in model (8)

With the inclusion of red zone areas in the population which are categorised as the compartment, there is a proportion of susceptibles and a proportion of infected individuals. Accordingly, outside the population, there are susceptibles and infected individuals. Thus, the novel system (8) is equivalent to

| (14) |

where and the matrices and are given as

and

The novel system (8) is subjected to the following initial conditions

| (15) |

where , such that for . denotes the Banach space of continuous functions mapping the interval into , where

In the subsequent part, the equilibrium points of system (14) are determined and the basic reproduction number, is derived.

7.1. Analysis of model (14)

Following the same procedures as elucidated in Section 6.1, the Covid-19 model delineating by the system of equations given by (14) is shown to exhibit the following equilibrium points:

-

1.The Disease Free Equilibrium, (DFE) is given as

which represents a disease free population. -

2.

The Disease Endemic Equilibrium, (DEE), .

The reproduction number for system (14), is given by

| (16) |

where is the spectral radius of the next-generation matrix with

| (17) |

can also be written as

| (18) |

Eq. (18) points out that the threshold number with the system embodied with the red zone compartment is lower than that of the system without red zone. This clearly justifies the efficiency of classifying zones to contain the prevalence of the Covid-19 in the latter regions. It is also imperative to highlight that provided that the proportion of population declared as red zone is less than , that is . Eq. (18) further indicates that it is more practical to impose a national lockdown with stringent measures if more than half of the population must be declared as red zones. In a situation whereby Covid-19 cases are spanned in almost all regions of a given population, Eq. (18) evidences the enactment of a national lockdown to better monitor the situation and curb the proliferation of the disease. The stability analysis of model (14) is quite intricate and is thus not conducted. The complexity of analysing the stability prompts the use of data to demonstrate the existence of the equilibrium points of both systems, numerically. In the section that tails, numerical experiments are effectuated to support the analytical results obtained in the previous sections. Data gathered for Mauritius from [1] is used to validate the systems developed in the current study. Numerous scenarios are also explored, showing the effect of different contact tracing rates, the implementation of red zones, amongst others on the dynamical evolution of the Covid-19 pandemic.

8. Numerical experiments

The results presented in this section are generated in MATLAB.

8.1. Simulations of model (8)

In order to support the theoretical results acquired in the previous sections, the list of values given in Table 2 and the following initial values are considered:

According to Theorem 1, in the absence of delay, the disease free equilibrium, of system (8) is locally asymptotically stable when . However, when exceeds , loses its stability, giving rise to the emergence of the unique disease endemic equilibrium, . Figs. 6 and 7 depict the stability of the two equilibrium points, and of model (8), in the absence of delay. As stated in the previous section, the disease endemic equilibrium, is quite complex and carrying out its stability analysis is challenging. Data is then opted to prove the stability of the equilibrium points numerically, in the presence of delay. Using the parameter values given in Table 2 and the initial values in Table 4 , the steady states of the model are attained and this property is shown in Figs. 8 and 9 . Since the system is induced by time delays, oscillatory behaviour is observed. Figs. 8 and 9 illustrate that the system exhibits damped oscillations, which eventually smear out and converge to the equilibrium states. From Figs. 8 and 9, it can be perceived that the delayed model emanates a non-physical behaviour, whereby the quarantine and infected compartments become negative owing to the oscillations possessed by the system. Yet, it needs to emphasise that although this behaviour is non-physical, it does not affect the stability of the model as the solutions of the model eventually converge to their steady state. This behaviour resulted due to the high delay values used. It is imperative to accentuate that with low delay values, the system evinces positive solutions at all time. However, to guarantee positivity, conditions on the parameters of the system are required, which is potentially an area for future investigation.

Fig. 6.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (8). The model attains the disease free equilibrium, , when and when . The transmission rate, is reduced to 0.025 and the contact tracing rate, is increased to 0.3. All the other parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

Fig. 7.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (8). The model settles on the disease endemic equilibrium, , when and when . All the parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

Table 4.

Initial proportion of individuals in each category.

| Variable | ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

Fig. 8.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (8). The model converges to the disease free equilibrium, , when with and . The transmission rate, is reduced to 0.025 and the contact tracing rate, is increased to 0.3. All the other parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

Fig. 9.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (8). The model attains the disease endemic equilibrium, , when with and . All the parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

The progression of the infected category of the delayed model (8) differs largely with the simulation of the model in the absence of delay. A lower peak is observed in Fig. 9 as compared to the proportion of infected individuals obtained in Fig. 7. Another important remark from Fig. (7) is that an escalating rise of infected cases is seen during the first 30 days. However, with the inclusion of delays in the system, a flattened curve can be pictured in Fig. (9), whereby the proportion of infected cases is viewed to grow gradually over the first 200 time steps, until it starts to decrease and settles on the locally asymptotically endemic equilibrium. Such fact reveals that incorporating delay in epidemic models is a key aspect since the asymptomatic carriers play a preponderant role in the spread of the disease. The dynamical behaviour of system (14) is next explored numerically and the results are presented in the following section.

8.2. Simulations of model (14)

In this section, we scrutinise the dynamics of model (14). The list of values given in Table 2 and the following initial values are employed:

Table 5.

Initial proportion of individuals in each category.

| Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

Figs. (10) and (11) show the trajectories of the different subpopulations of system (14). When , the system converges to the disease free equilibrium, and when the threshold term exceeds , the model settles on the disease endemic equilibrium, . It should be underlined that the same set of parameter values is utilised to demonstrate the behaviour of the system around the two equilibrium states.Figs. (12 ) and (13 ) show the superimposition of the progression of the subcategories of both models over time. As stipulated in the previous section, Eq. (18) points out that . It is now certified numerically that model (14) attains with a value of and with a value of , as delineated in Figs. (10) and (11) respectively. It is noted that in both cases, .

Fig. 10.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (14). The model attains the disease free equilibrium, , when with and . The transmission rate, is reduced to 0.025 and the contact tracing rate, is increased to 0.3. All the other parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

Fig. 11.

Evolution of the subcategories of model (14). The model settles on the disease endemic equilibrium, , when with and . All the parameter values are the same as those in Table 2.

Fig. 12.

Superimposition of the evolution of the population with Red Zones (solid lines) and without Red Zones (dashed lines) when .

Fig. 13.

Superimposition of the evolution of the population with Red Zones (solid lines) and without Red Zones (dashed lines) when .

Although a slight reduction between the reproduction numbers is noted, the effect of classifying red zone areas has a considerable impact on the number of infected cases. This fact is supported by Fig. (13). The proportion of individuals in the infected category is lessened with model (14), that is when certain areas are categorised as red zones. The present work provides a more feasible insight into the impact of partitioning zones of a certain population and furnishes valuable perspectives to assist the health authorities in addressing the complex issue related to the pervasiveness of Covid-19 cases.

8.3. Impact of contact tracing and vaccination processes on the dynamics of the Covid-19

Since the reproduction number of both models are governed by the contact tracing rate, and the vaccination rate, , it is crucial to examine their effect on contagion.Fig. (14 ) points out the relationship of the contact tracing rate, and the vaccination rate, with the reproduction numbers, and . As depicted in Fig. (14), with a very low rate of contact tracing, the threshold number is high. It is noteworthy that a high contact tracing rate of and no vaccination cause the threshold value to remain above 1. A previous study also reported a similar result [14], arguing that a contact tracing rate of reduces the reproduction number but is indeed not sufficient to delcine it to below unity.Fig. (14) underscores the fact that relying only on the contact tracing or on vaccination to fight against the proliferation of the pandemic is not adequate. Necessarily, a combination of both contact tracing process and the progression of the vaccination campaigns is indispensable to attenuate the reproductive ratio to below 1 in value, which can be vindicated from Fig. (14).

Fig. 14.

Effect of the contact tracing rate, and the vaccination rate, on the reproduction number of both systems.

8.4. Effect of different contact tracing rates on the infected category

Contact tracing is a crucial strategy for interrupting chains of human-to-human transmission. This process entails the identification of people who have been in close contact or exposed to individuals with confirmed diagnoses. Identifying the source of infection through case investigations is of paramount importance as unrecognised chains of transmission and common points of exposure are detected [3]. It is well known that contact tracing is a key containment approach to curb the widespread of the Covid-19 virus. The impact of contact tracing rate on the dynamics of model (14) is next examined. Fig. (15 ) illustrates the proportion of infected individuals with three different contact tracing rates. The plot justifies the efficiency of contact tracing in a population whereby the Covid-19 is prevalent. The proportion of the infected compartment is shrinked by around with a contact tracing rate of . Fig. (15) gives insight on the effectiveness of contact tracing during the course of a disease outbreak.

Fig. 15.

Effect of the contact tracing rate, on the proportion of infected individuals.

8.5. Validation of the model using data for Mauritius

In order to validate the model proposed in the current study, data available for the Covid-19 pandemic in Mauritius is opted [1]. The data acquisition period ranged from 5 March 2021 to 2 September 2021. The initial values used to conduct the simulations for Mauritius is presented in Table 6 .

Table 6.

Initial proportion of individuals in each category as of 5 March 2021 [36].

| Variable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial value | 100000 | 1981 | 704 | 617 | 588 | 51511 |

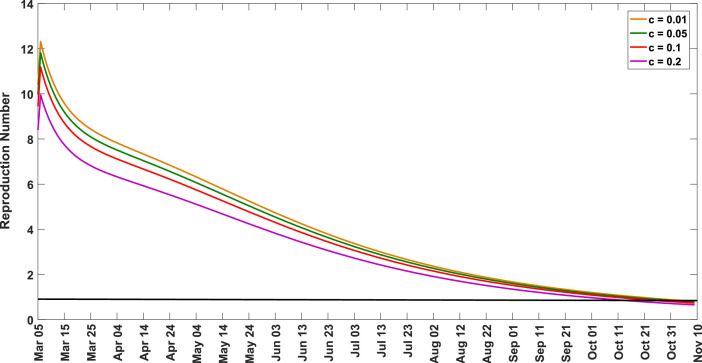

Fig. (16) depicts the evolution of the dynamics of Covid-19 in Mauritius for the period of 5 March 2021 to 2 September 2021. The comparison between the simulation and the actual data is shown. It is clear that the model forecasts the evolution of the outbreak quite accurately with the observed data, emanating the possible trend of the pandemic. The underestimation observed in Fig (16) can be explained by the assumptions made in the model. It is also worth stressing that in Mauritius, as from August 2021, selective screening were implemented, targeting patients with symptoms only. Consequently, due to testing being restricted to acute cases only, the actual toll could be higher, justifying the overestimation of the number of Covid-19 cases, as depicted in Fig. (16). This highlights the point that under testing is putting the lives of people at risk of further contagion as testing is performed only on people showing symptoms.Fig. (17 ) pictures the corresponding temporal evolution of in Mauritius for the period of 5 March 2021 to 2 September 2021. As of 2 September 2021, a value of 1.5 is observed, indicating that the Covid-19 is still prevailing in Mauritius. From our study of the reproduction number for the Covid-19 prevailing in Mauritius, it is estimated that on average, an infected individual, before he/she recovers, has the potential to infect on average more than one people. The latter will each infect at least one more people and so on. As a result, the disease can spread to a large fraction of the population.Fig. (18 ) pictures the estimated epidemic curves for Mauritius, with different contact tracing rates. The epidemic trajectories demonstrate that a peak is expected in mid-October 2021. As illustrated in the plot, with a high contact tracing rate, the peak is reduced considerably.Fig. (19 ) shows the corresponding temporal evolution of the reproduction number for the same scenarios. The horizontal black line in Fig (19) gives an indication that the threshold value falls to below unity after mid-October 2021. It can be inferred that if the declining trend of the reproduction number continues with the assumption of no resurges of the epidemic disease in Mauritius, the outbreak will gradually die out. Evidently, the present system can be used as a forecasting tool to simulate numerous scenarios, stemming out realistic nowcasting and forecasting results of the evolution of the Covid-19. Such study furnishes policy and decision makers to design timely and effective attempts to mitigate the propagation of such outbreak.

Fig. 16.

Superimposition of the progression of the simulated number of infected individuals (red) with the actual data (blue).

Fig. 17.

Temporal evolution the reproduction number in Mauritius for the period 5 March 2021 to 2 September 2021.

Fig. 18.

Forecast of the Covid-19 pandemic in Mauritius.

Fig. 19.

Evolution of the reproduction number in Mauritius.

9. Conclusion

In this work, a novel cellular automaton (CA) model that described the dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic was established. Since contact tracing, quarantine and red zones are the key measures to curtail the spread of the Covid-19, the latter were incorporated in the CA system to better understand the efficiency of implementing such measures. Additionally, the incubation and illness times of the Covid-19 virus were taken into account in the CA model. In order to illustrate the rules governing the CA model with and without the effect of red zones, an algorithm was presented. A mean field approximation of the CA was conducted to further explore the dynamics of the disease and a nonlinear system of delay differential equations (DDE) was yielded. The concept of red zones was integrated in the resulting DDE system which resulted in a DDE model with red zone. Stability analysis of both systems were effectuated and their respective reproduction numbers were derived. An investigation was carried out to demonstrate the effect of vaccination and contact tracing on the reproduction numbers. Numerical experiments were performed and Covid-19 data in Mauritius was opted to validate the model. The results revealed that relying only on contact tracing or vaccination is insufficient to contain the virus. Effective contact tracing and vaccination are adequate to lower the spread of the disease in the community. Moreover, our findings justified the efficacy of contact tracing, quarantine and the enaction of red zones in the population.

The future scope of this work is to embody the effectiveness of vaccines in the spread of the Covid-19 virus. Including such feature in the model can furnish us more enhanced results to adopt and deploy better mitigation strategies to combat the widespread of the disease in the population. Furthermore, owing to the simplicity of the CA model developed in the current study, the system is applicable across a spectrum of diseases. With appropriate parametrisation, the CA model can be applied to any given population and can provide a more feasible insight into the impact of strategies adopted to contain an infectious disease.

Acknowledgments

This work has been conducted under the HEC (Higher Education Commission Mauritius) MPhil/PhD scholarship. The authors thank the reviewers for their insightful comments which improved the readability of the paper.

Appendix A. Coefficients of the characteristic equation (13)

The coefficients of the characteristic equation given by Eq. (13) are as follows:

| (19) |

The following Lemma due to [37] is used to examine the distribution of the characteristic roots of Eq. (13):

Lemma 1

Consider the following exponential polynomial

whereforandare constants forand. Asvary, the sum of the order of the zeros ofon the open right half plane can change only if a zero appears on or crosses the imaginary axis.

Appendix B. Proof of Theorem 1

Case 1:.

The characteristic equation given by Eq. (13) reduces to

| (20) |

Clearly, the characteristic equation given by Eq. (20), has the following 3 negative roots namely,

| (21) |

The other 2 roots are determined by the following quadratic equation

| (22) |

The 2 roots are negative provided that

| (23) |

In terms of , can be written as

| (24) |

From Eq. (24), it is observed that when . Similarly, can be written as

| (25) |

After some algebraic manipulations, it can be deduced that under the condition .

Appendix C. Proof of Theorem 2

Case 2: and .

The characteristic equation given by Eq. (13) reduces to

| (26) |

It is easy to see that Eq. (26) has the following 3 negative roots namely,

| (27) |

The other roots are then determined by the following trascendental polynomial equation in

| (28) |

Multiplying on both sides of Eq. (28), we get

| (29) |

Suppose that is a root of Eq. (29). Then, we have

| (30) |

Separating the real and imaginary parts, the following system, satisfied by is obtained:

| (31) |

Then, we can get

| (32) |

and

| (33) |

To eliminate the trigonometric functions, we square both sides of Eqs. (32) and (33). The resulting squared equations are added and the following eighth order equation in is obtained:

| (34) |

where

| (35) |

To reduce this eighth order equation in to a quartic equation, letting yields to

| (36) |

Eq. (36) can be further factorised as

| (37) |

Note that the solution is not considered since it is assumed that . Let

| (38) |

We need to determine conditions under which the roots of Eq. (38) are negative. is coercive as . The polynomial has then at least a global minimum. We next seek the two roots of .

| (39) |

It is easy to get that the two roots of are

| (40) |

Let If , then the function is monotonic increasing in . Thus, when the constant term and Eq. (38) has no positive roots. That is, there exists no positive value of , which satisfies the transcendental Eq. (29). So all the s have negative real parts for all values of the delay . Under the above conditions, the stability of the DFE does not change when the delay parameter , changes.

Appendix D. Proof of Theorem 3

Case 3: and .

The characteristic equation given by Eq. (13) reduces to

| (41) |

The characteristic equation given by Eq. (41), has the following 3 negative roots namely,

| (42) |

The other 2 roots are determined by the following equation

| (43) |

Suppose that is a root of Eq. (43). Replacing in Eq. (43), we get

| (44) |

Separating the real and imaginary parts, the following system, satisfied by is obtained:

| (45) |

Eliminating by squaring and adding the above system of equations, we obtain a polynomial in as:

| (46) |

Eq. (46) will have negative roots provided that

| (47) |

After some algebraic calculations, it can be verified that if , the condition holds when . It is easy to assert that the second condition given in Eq. (47) holds true.

Data Availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Worldometer, Covid-19 Coronavirus Pandemic, 2021, https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 2.Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-ncov outbreak originating in wuhan, china: a modelling study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization W.H., et al. Technical Report. 2020. Contact tracing in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 10 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson R.M., Heesterbeek H., Klinkenberg D., Hollingsworth T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the covid-19 epidemic? The lancet. 2020;395(10228):931–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kucharski A.J., Klepac P., Conlan A.J., Kissler S.M., Tang M.L., Fry H., Gog J.R., Edmunds W.J., Emery J.C., Medley G., et al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of sars-cov-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(10):1151–1160. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30457-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham B.S. Rapid covid-19 vaccine development. Science. 2020;368(6494):945–946. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saleh A., Qamar S., Tekin A., Singh R., Kashyap R. Vaccine development throughout history. Cureus. 2021;13(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.16635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernal J.L., Andrews N., Gower C., Robertson C., Stowe J., Tessier E., Simmons R., Cottrell S., Roberts R., O’Doherty M., et al. Effectiveness of the pfizer-biontech and oxford-astrazeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in england: test negative case-control study. bmj. 2021;373 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candelli M. Covid-19 vaccine: what are we doing and what should we do? The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022;22(5):569–570. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00003-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.C. Wang, J. Han, Will the covid-19 pandemic end with the delta and omicron variants?, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Corrao G., Franchi M., Cereda D., Bortolan F., Zoli A., Leoni O., Borriello C.R., Della Valle G.P., Tirani M., Pavesi G., et al. Persistence of protection against sars-cov-2 clinical outcomes up to 9 months since vaccine completion: a retrospective observational analysis in lombardy, italy. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022;22(5):649–656. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00813-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhumal S., Patil A., More A., Kamtalwar S., Joshi A., Gokarn A., Mirgh S., Thatikonda P., Bhat P., Murthy V., et al. Sars-cov-2 reinfection after previous infection and vaccine breakthrough infection through the second wave of pandemic in india: An observational study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2022;118:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeolekar B.M., Shah N.H. Mathematical Analysis for Transmission of COVID-19. Springer; 2021. Transmission dynamics of covid-19 from environment with red zone, orange zone, green zone using mathematical modelling; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturniolo S., Waites W., Colbourn T., Manheim D., Panovska-Griffiths J. Testing, tracing and isolation in compartmental models. PLoS computational biology. 2021;17(3):e1008633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schimit P.H. A model based on cellular automata to estimate the social isolation impact on covid-19 spreading in brazil. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine. 2021;200:105832. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai J., Zhai C., Ai J., Ma J., Wang J., Sun W. Modeling the spread of epidemics based on cellular automata. Processes. 2021;9(1):55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilinski A., Mostashari F., Salomon J.A. Modeling contact tracing strategies for covid-19 in the context of relaxed physical distancing measures. JAMA network open. 2020;3(8) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e2019217–e2019217

- 18.Guglielmi N., Iacomini E., Viguerie A. Delay differential equations for the spatially-resolved simulation of epidemics with specific application to covid-19. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.01102. 2021 doi: 10.1002/mma.8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauritius W.H.O.C.O. Technical Report. 2020. Best practices and experience of Mauritius’ preparedness and response to COVID-19 pandemic Inter-Action Review 1 - January to August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruhomally Y.B., Dauhoo M.Z. The NERA model incorporating cellular automata approach and the analysis of the resulting induced stochastic mean field. Computational and Applied Mathematics. 2020;39(4):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruhomally Y.B., Dauhoo M.Z., Dumas L. A graph cellular automaton with relation-based neighbourhood describing the impact of peer influence on the consumption of marijuana among college-aged youths. Journal of Dynamics & Games. 2021;8(3):277. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eames K.T., Keeling M.J. Contact tracing and disease control. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003;270(1533):2565–2571. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schimit P., Monteiro L. On the basic reproduction number and the topological properties of the contact network: An epidemiological study in mainly locally connected cellular automata. Ecological Modelling. 2009;220(7):1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goel K., Kumar A., et al. Nonlinear dynamics of a time-delayed epidemic model with two explicit aware classes, saturated incidences, and treatment. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2020;101(3):1693–1715. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05762-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quesada J., López-Pineda A., Gil-Guillén V., Arriero-Marín J., Gutiérrez F., Carratala-Munuera C. Incubation period of covid-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Revista Clínica Española (English Edition) 2021;221(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.rceng.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., Azman A.S., Reich N.G., Lessler J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Annals of internal medicine. 2020;172(9):577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaki N., Mohamed E.A. The estimations of the covid-19 incubation period: A scoping reviews of the literature. Journal of infection and public health. 2021;14(5):638–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhouib W., Maatoug J., Ayouni I., Zammit N., Ghammem R., Fredj S.B., Ghannem H. The incubation period during the pandemic of covid-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews. 2021;10(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piticchio T., Le Moli R., Tumino D., Frasca F. Relationship between betacoronaviruses and the endocrine system: a new key to understand the covid-19 pandemic-a comprehensive review. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2021;44(8):1553–1570. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01486-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chipimo P.J., Barradas D.T., Kayeyi N., Zulu P.M., Muzala K., Mazaba M.L., Hamoonga R., Musonda K., Monze M., Kapata N., et al. First 100 persons with covid-19-zambia, march 18–april 28, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(42):1547. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolossa T., Wakuma B., Seyoum Gebre D., Merdassa Atomssa E., Getachew M., Fetensa G., Ayala D., Turi E. Time to recovery from covid-19 and its predictors among patients admitted to treatment center of wollega university referral hospital (wurh), western ethiopia: Survival analysis of retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guan C., Yuan W., Peng Y. 2011 Fourth International Joint Conference on Computational Sciences and Optimization. IEEE; 2011. A cellular automaton model with extended neighborhood for epidemic propagation; pp. 623–627. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hale J.K. Theory of Functional Differential Equations. Springer; 1977. Retarded functional differential equations: basic theory; pp. 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruhomally Y.B., Jahmeerbaccus N.B., Dauhoo M.Z. The deterministic evolution of illicit drug consumption within a given population. ESAIM: Proceedings and Surveys. 2018;62:139–157. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van den Driessche P., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical biosciences. 2002;180(1-2):29–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M. of Health, Wellness, besafemoris, 2021, https://besafemoris.mu/.

- 37.Ruan S., Wei J. On the zeros of transcendental functions with applications to stability of delay differential equations with two delays. Dynamics of Continuous Discrete and Impulsive Systems Series A. 2003;10:863–874. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.