Abstract

Social functioning is impaired in severe mental disorders despite clinical remission, illustrating the need to identify other mechanisms that hinder psychosocial recovery. Affective lability is elevated and associated with an increased clinical burden in psychosis spectrum disorders. We aimed to investigate putative associations between affective lability and social functioning in 293 participants with severe mental disorders (schizophrenia- and bipolar spectrum), and if such an association was independent of well-established predictors of social impairments. The Affective Lability Scale (ALS-SF) was used to measure affective lability covering the dimensions of anxiety-depression, depression-elation and anger. The interpersonal domain of the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) was used to measure social functioning. Correlation analyses were conducted to investigate associations between affective lability and social functioning, followed by a hierarchical multiple regression and follow-up analyses in diagnostic subgroups. Features related to premorbid and clinical characteristics were entered as independent variables together with the ALS-SF scores. We found that higher scores on all ALS-SF subdimensions were significantly associated with lower social functioning (p < 0.005) in the total sample. For the anxiety-depression dimension of the ALS-SF, this association persisted after controlling for potential confounders such as premorbid social functioning, duration of untreated illness and current symptoms (p = 0.019). Our results indicate that elevated affective lability may have a negative impact on social functioning in severe mental disorders, which warrants further investigation. Clinically, it might be fruitful to target affective lability in severe mental disorders to improve psychosocial outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00406-022-01380-1.

Keywords: Affective lability, Social functioning, Psychotic disorders, Schizophrenia spectrum, Bipolar spectrum, Affective lability Scale Short Form (ALS-SF)

Introduction

Social functioning, defined as the capacity of a person to function in different societal roles such as homemaker, worker, student, partner, family member or friend [1, 2], is an important marker of recovery and a predictor of quality of life in severe mental disorders [3, 4]. Social impairments are present across schizophrenia- and bipolar spectrum disorders and appear to be driven by a range of factors. A better understanding of the different paths leading to social impairment is important to tailor and personalize interventions for the individual patient. Affective disturbances, defined broadly as disruptions in the subjective experience, expressive behavior and physiology of emotions and mood [5], are taxing and highly prioritized as treatment targets by the patients [6–8]. Several studies have found significant associations between various forms of dysregulated affect and reduced social functioning in patients with both non-affective and affective psychotic disorders [9–15]. This association appears to be independent of other risk factors such as neurocognitive- and social cognitive deficits, indicating that affective dysregulation may uniquely contribute to social impairments in psychosis. As human emotions are developed, expressed and regulated in interaction with others, it is perhaps not surprising that challenges with affect regulation make social contexts and situations particularly burdensome [16]. Still, there is a paucity of studies investigating the role of specific facets of affective dysregulation for social functioning in severe mental disorders [17, 18]. Affective lability refers to the propensity to experience rapid, excessive and unpredictable changes in affective states and is associated with poor clinical and functional outcome in many psychiatric disorders [19, 20]. In a sample partially overlapping with that of the current study, we have previously found that affective lability is elevated in schizophrenia- and bipolar spectrum disorders compared to healthy controls [21]; with the highest level in bipolar II disorder (BDII) and equally high levels in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BDI) [22]. Hence, affective lability appears to be a common illness feature across these disorders, with potential consequences for clinical outcome.

To clarify the relationship between affective lability and social functioning in severe mental disorders, other known risk factors for social impairment must be taken into consideration. Predictors of social impairment appear similar across the disorders, and range from individual characteristics through lifetime- and current illness-related features [23, 24]. As social impairment is higher in schizophrenia compared to schizoaffective- and bipolar disorders [23], the presence and/or prominence of psychotic symptoms may be of relevance. This is supported by findings of larger functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms compared to those without [25–27]. Nonetheless, the severity of affective symptoms, depressive in particular, also seems to predict social functioning across diagnoses [28–33]. Hence, core clinical symptoms, both current and over the lifetime, appear to be central to social functioning in these populations. In addition, there are several other shared risk factors for social impairments highlighted in the literature. These include male sex [34, 35], poor premorbid social functioning [36, 37], neurocognitive deficits [25, 38], total number of illness episodes [28, 39], duration of untreated illness [40, 41], negative symptoms including apathy [23, 33, 42] and comorbidity such as substance use and anxiety [28, 43–46].

Here, we aim to investigate the relationship between affective lability and social functioning in severe mental disorders, and to explore whether this putative relationship is specific to subdimensions of affective lability. To our knowledge, this relationship has not been investigated previously. We hypothesize that affective lability will be associated with social functioning independent of other pre-defined predictors of social impairment across severe mental disorders.

Methods

Participants

The study sample was comprised of two hundred and ninety-three participants with severe mental disorders (schizophrenia [n = 62]; schizophreniform [n = 13]; schizoaffective [n = 16]; BDI [n = 102]; BDII [n = 68]; psychosis Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) [n = 32]), recruited through the Thematically Organized Psychosis (TOP) research study at the Norwegian Center for Mental Disorders Research (NORMENT) in Oslo, Norway. Recruitment to the TOP study is consecutive and still ongoing via psychiatric inpatient and outpatient units in a catchment area that is comprised of all the major hospitals in Oslo. All participants in the study must meet diagnostic criteria for a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of schizophrenia- or bipolar spectrum disorders and be able to give informed consent. In addition, exclusion criteria are intelligence quotient (IQ) below 70, prior history of severe head trauma and insufficient understanding of a Scandinavian language. In the current study, only participants who had completed the Affective Lability Scale—Short Form (ALS-SF) and the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) were included.

The TOP study has been approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate and is conducted in line with the Helsinki declaration of 1975 (as revised in 2008 and 2013).

Diagnostic assessment

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV axis 1 disorders (SCID; modules A-E) [47] was used to establish diagnoses in the study as part of a thorough clinical assessment carried out by clinical psychologists, medical doctors in psychiatric residency or psychiatrists. All clinical personnel in the study undergo an extensive 3-month training and quality assurance program in the use of SCID and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) developed at the University of California, Los Angeles, USA [48] before being allowed to carry out clinical interviews with diagnostic assessments, irrespective of previous clinical training. Diagnostic reliability across different groups of assessment teams have demonstrated a Cohen’s kappa for diagnosis in the range between 0.92 and 0.99.

The Social Functioning Scale (SFS)

The Social Functioning Scale is a self-report scale that was originally developed to measure social adjustment in patients with schizophrenia, tapping areas of functioning that are crucial to community living [49]. It has later been validated for use with other severe mental disorders, including bipolar disorder, and has been found to have sound psychometric properties, as well as to correlate highly with clinician-rated measures of functioning [3, 24, 50–53]. The scale is comprised of 76 items that are rated on a Likert scale and yields a total score of overall functioning after illness debut, as well as scores on seven subscales: (1) social engagement/withdrawal (amount of time spent alone, likelihood of initiating conversations, social avoidance); (2) interpersonal behavior (number of friends, romantic relationships, quality of communication); (3) prosocial activities (engagement in common social activities, e.g. going to the cinema); (4) recreation (engagement in hobbies/activities); (5) independence-competence (ability to maintain independent living, e.g. shopping for groceries); (6) independence-performance (performance of skills required for independent living); (7) employment/occupation (or being a full-time student). Each subscale is standardized and normalized to a scaled score (SS) with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15, and the full-scale score is calculated as the mean of the SSs of the seven subscales [49]. The first two subscales combined are referred to as the SFS interpersonal domain. This domain has been found to have good ecological validity and to capture social isolation and social avoidance in particular [54], which are in themselves risk factors for depression, loneliness and other negative health outcomes [16]. The 3rd and 4th subscales comprise the activity domain, and although it includes single items that may reflect social functioning (i.e. whether you have visited friends), it has been found to have low ecological validity [54]. The remaining three subscales are not reflective of social functioning per se, but rather encompass skills for independent living (budgeting, preparing a meal, etc.) and ability to work/study which were not of primary interest in this respect. Consequently, only the interpersonal domain was used for the present study as this domain best represents our outcome measure of interest, namely social functioning. A higher score on the SFS interpersonal domain is indicative of a higher level of functioning.

The Affective Lability Scale Short Form (ALS-SF)

We used the Affective lability Scale Short Form (ALS-SF) [55] to measure affective lability. The scale, which is filled in by the participant, yields a total level of affective lability, in addition to subscores covering fluctuations between three subdimensions; anxiety-depression, depression-elation and anger-normal mood. The scale contains 18 items that are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“very uncharacteristic of me”) to 3 (“very characteristic of me”) and has been found to have good psychometric properties [21, 56, 57]. Of the items, five refer to shifts in anxiety-depression, eight refer to shifts in depression-elation and the final five items cover shifts between anger-normal mood. The ALS-SF yields subscores for the three subdimensions in addition to a total score of affective lability (the sum of all item responses divided by 18). In the current study, we chose to investigate the subdimensions in the total sample as opposed to the composite (total) ALS-SF score to more specifically address if there are certain types of affective lability that appear to be linked to social functioning.

Potential confounders of the relationship between social functioning and affective lability

The following variables are previously established predictors of social functioning considered potential confounders of the relationship between social functioning and affective lability in the current analyses. With respect to individual characteristics we investigated: sex, premorbid social functioning based on scores on the social domain in childhood from the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) [58, 59], as well as overall cognitive ability measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI, [60]). More specific investigations of the role of cognitive deficits on social functioning were beyond the scope of the current study. Features related to illness course included estimation of duration of illness which was based on the age of onset of the first SCID-verified episode of psychosis for schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective and psychosis NOS, and the first SCID-verified affective episode for BDI and BDII. We also calculated an estimate for the duration of untreated illness. For schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective and psychosis NOS, duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was calculated as the number of weeks from the first SCID-verified psychotic episode to adequate treatment (antipsychotic medication in adequate doses/admission to hospital for psychosis). For BDI and BDII, the duration of untreated bipolar disorder (DUB) was based on the number of weeks from the first SCID-verified episode of mania/hypomania to adequate treatment (mood-stabilizing medication or antipsychotics in adequate doses/hospital admission for treatment of mania). DUP and DUB were combined into one variable, duration of untreated illness, to use in the analyses of the whole sample. Further, the total number of illness episodes was calculated as the sum of all recorded illness episodes (depressive, hypomanic, manic, mixed, psychotic). Based on previous indications of a relationship between psychotic symptoms and lower social functioning and since the present sample also included individuals with bipolar disorder who have never had a psychotic episode, a categorical psychosis lifetime variable was made which denoted the lifetime history of a SCID-verified psychotic episode. With respect to current symptom states, they were assessed with the following: positive psychotic symptoms with the positive subscale of the PANSS [61], negative symptoms with the negative subscale of the PANSS, manic symptoms with the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS [62]), and depressive symptoms were assessed with the depression item (G6) in the general scale of the PANSS. To measure comorbid anxiety symptoms, the anxiety item (G2) from the general scale of the PANSS was used. These items from the general scale of the PANSS were chosen because they were the only measures of depression and anxiety collected at the same time point as the ALS-SF and the SFS for all participants. We further used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT, [63]) and the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT, [64]) to measure the degree of harmful substance use since associations between reduced social functioning and substance use has previously been found [65, 66].

Statistical analyses

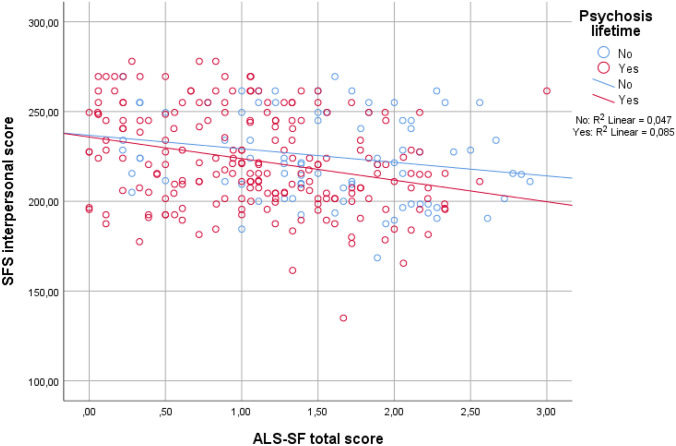

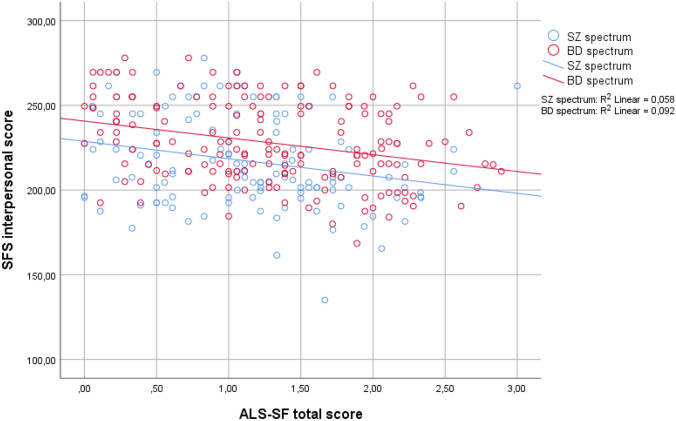

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample were investigated with descriptive statistics, including means with standard deviations or frequencies with percentages as fitted. Pearson and Spearman’s correlations were conducted to investigate the relationship between the SFS interpersonal domain and ALS-SF dimensions. Correlational analyses were also performed to investigate the relationship between the SFS interpersonal and demographic as well as clinical variables that have been established as predictors of social functioning in previous research. This was followed by a hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis for the SFS interpersonal score entering all the variables that were significantly associated with the SFS score. The analysis was conducted block-wise to investigate the proportion of variance explained by affective lability specifically. Here, premorbid social adjustment was entered first, the illness course variables (duration of untreated illness, total number of illness episodes) next, followed by the current symptom- and comorbidity variables (positive- and negative symptoms, manic symptoms, depression and anxiety) and finally all of the ALS-SF subdimensions in the last block. There were no indications of problematic multicollinearity between the ALS-SF subdimensions (tolerance ≥ 0.35 and VIF ≤ 2.9 for all dimensions). Based on our previous findings of higher levels of affective lability in BDII versus BDI and schizophrenia [67] and lower levels of social functioning in schizophrenia and psychotic versus non-psychotic bipolar disorder, we anticipated a possible interaction effect between lifetime psychosis and affective lability on social functioning. However, visual inspections of a scatterplot of the relationship between SFS and ALS-SF split by the dichotomous psychosis lifetime variable (Fig. 1) did not indicate an interaction between ALS-SF and psychosis lifetime on social functioning. Thus, we did not include such an interaction term in the regression analysis. As there could be differences between the diagnostic groups in terms of social functioning and to further disentangle putative relationships, follow-up analyses were also carried out in diagnostic subgroups according to current diagnostic nomenclature: schizophrenia spectrum (schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, psychosis NOS; n = 123) and bipolar spectrum (BDI and BDII; n = 170). Here, separate bivariate analyses for the two groups were performed to investigate the association between social functioning and affective lability, in addition to the other relevant demographic and clinical variables. The variables that were significantly associated with the SFS interpersonal score in bivariate analyses for each group were then entered into separate forced entry hierarchical multiple regression models. Due to lower n when the sample was split, the total score of the ALS-SF was used in the multivariate analyses for both groups to ensure enough statistical power when all predictor variables were entered. An interaction term between affective lability and diagnostic subgroup on social functioning was not included as a scatterplot did not indicate the presence of such an interaction (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The relationship between affective lability and social functioning split by the presence of lifetime psychosis

Fig. 2.

The relationship between affective lability and social functioning split by diagnostic group

All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, version 26) and a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 (two-tailed tests) was employed.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. There were 82 participants without lifetime psychosis; 25/102 (24.5%) in BDI and 57/68 (83.8%) in BDII.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| Total sample, n = 293 | Schizophrenia-spectrum, n = 123 | Bipolar-spectrum, n = 170 | Statistics | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 30.1 (9.9) | 29.7 (8.9) | 31 (10.5) | t = − 1.092, df = 284 | 0.276 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 157 (53.0) | 53 (43.1) | 101 (59.4) | X2 = 7.625, df = 2 |

0.006 BD > SZ |

| SFS interpersonal | 223.4 (25.9) | 217.1 (27.4) | 227.9 (24.1) | t = − 3.586, df = 291 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| Duration of illness, yearsa | 8.6 (9.0) | 4.9 (6.6) | 11.2 (9.5) |

t = − 6.675, df = 288 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| IQ (WASI)b | 108 (13.4) | 104 (14.8) | 110.9 (11.5) |

t = − 4.277, df = 204 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| Total number of illness episodes | 9.4 (16.2) | 3.9 (4.8) | 13.4 (19.9) |

t = − 5.981, df = 196 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| Onset of illness ≤ 18 years, n (%) | 123 (42.0) | 25 (20.3) | 98 (57.6) |

X2 = 40.813, df = 1 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| Duration of untreated illness, weeksc | 47 (145.3) | 75 (173.3) | 22 (109.5) |

t = 2.764, df = 226 |

0.008 SZ > BD |

| Premorbid social functioning (PAS)d | 1.9 (2.3) | 2.1 (2.4) | 1.8 (2.3) |

t = 1.196, df = 286 |

0.233 |

| Psychosis lifetime, n (%) | 214 (72.1) | 123 (100) | 88 (52) |

X2 = 82.386, df = 1 |

0.000 SZ > BD |

| PANSS—total | 47.8 (13.3) | 55.4 (15.1) | 42.3 (8.3) |

t = 8.702, df = 175 |

0.000 SZ > BD |

| PANSS—Positive | 10.4 (3.9) | 12.6 (4.4) | 8.9 (2.5) |

t = 8.488, df = 178 |

0.000 SZ > BD |

| PANSS—Negative | 11.2 (4.8) | 14.0 (5.7) | 9.2 (2.5) |

t = 8.797, df = 157 |

0.000 SZ > BD |

| Depression (PANSS item G6) | 2.4 (1.3) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.4) |

t = − 1.448, df = 291 |

0.149 |

| Anxiety (PANSS item G2) | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.4) |

t = − 1.688, df = 291 |

0.092 |

| YMRS—totale | 2.6 (3.6) | 2.7 (3.6) | 2.5 (4.1) |

t = .490, df = 288 |

0.624 |

| AUDITf | 6.8 (6.0) | 5.2 (4.9) | 8.1 (6.5) |

t = − 4.116, df = 282 |

0.000 BD > SZ |

| DUDITg | 3.2 (6.6) | 3.2 (7.1) | 3.2 (6.4) |

t = − .068, df = 281 |

0.946 |

| ALS-SF—total | 1.2 (0.71) | 1.1 (0.65) | 1.3 (0.73) |

t = − 1.890, df = 291 |

0.060 |

| ALS-SF anxiety-depression | 1.4 (0.87) | 1.3 (0.83) | 1.5 (0.90) |

t = − 1.168, df = 291 |

0.244 |

| ALS-SF depression-elation | 1.4 (0.74) | 1.3 (0.71) | 1.4 (0.76) |

t = − 1.453, df = 291 |

0.147 |

| ALS-SF anger | 0.80 (0.78) | 0.67 (0.75) | 0.90 (0.80) |

t = − 2.559, df = 291 |

0.011 |

SFS Social Functioning Scale, WASI Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, PAS Premorbid Adjustment Scale, PANSS Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, YMRS Young Mania Rating Scale, AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, DUDIT Drug Use Disorders Identification Test, ALS-SF Affective Lability Scale Short Form

Statistically significant p values are in bold

a99% (n = 290) participants had data on duration of illness

b93% (n = 273) participants had data on IQ

c78% (n = 228) had data on duration of untreated illness

d98.2% (n = 288) participants had data on PAS

e99% (n = 290) participants had data on YMRS

f96.9% (n = 284) participants had data on AUDIT

g96.6% (n = 283) participants had data on DUDIT

Bivariate analyses in the total sample

Overall, although correlation coefficients are low to moderate, the analyses revealed significant associations between all of the ALS-SF subdimension scores and the SFS interpersonal score (anxiety-depression p < 0.001, depression-elation p = 0.003, anger p < 0.001), as well as the total score (p < 0.001). The SFS interpersonal score was further significantly associated with current manic symptoms, current positive and negative psychotic symptoms, current anxiety and depressive symptoms, duration of untreated illness, total number of illness episodes, as well as premorbid social functioning in childhood (see Table 2 for correlation coefficients). The SFS interpersonal score was not associated with sex, age, illness onset at or before 18, duration of illness, IQ, alcohol- or drug misuse, or the psychosis lifetime variable.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlation analyses

| Total sample | Schizophrenia-spectrum | Bipolar-spectrum | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SFS interpersonal | SFS interpersonal | SFS interpersonal | |

| Sex | rs = 0.032 | rs = 0.152 | rs = − 0.126 |

| Age | rs = 0.020 | rs = − 0.031 | rs = − 0.016 |

| IQ | r = 0.117 | r = − 0.003 | r = 0.133 |

| PANSS P | rs = − 0.391** | rs = − 0.426** | rs = − 0.203** |

| PANSS N | rs = − 0.399** | rs = − 0.470** | rs = − 0.236** |

| PANSS G2 | rs = − 0.236** | rs = − 0.295** | rs = − 0.236** |

| PANSS G6 | rs = − 0.174** | rs = − 0.212* | rs = − 0.208** |

| YMRS | rs = − 0.142** | rs = − 0.161 | rs = − 0.111 |

| AUDIT | r = 0.092 | r = 0.103 | r = 0.011 |

| DUDIT | rs = − 0.041 | rs = − 0.013 | rs = 0.019 |

| Psychosis lifetime | rs = − 0.052 | n0.a | rs = 0.092 |

| Premorbid social functioning | rs = − 0.218** | rs = − 0.308** | rs = − 0.125 |

| Duration of untreated illness | rs = − 0.197** | rs = − 0.229* | rs = − 0.051 |

| Total number of illness episodes | rs = 0.175** | rs = 0.098 | rs = 0.046 |

| Duration of illness | rs = 0.034 | rs = − 0.076 | rs = − 0.035 |

| ALS-SF total | r = − 0.244** | r = − 0.240** | r = − 0.303** |

| ALS-SF anxiety-depression | r = − 0.283** | r = − 0.308** | r = − 0.304** |

| ALS-SF depression-elation | r = − 0.171** | r = − 0.103 | r = − 0.265** |

| ALS-SF anger | r = − 0.208** | r = − 0.246** | r = − 0.249** |

SFS Social Functional Scale, PANSS P Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Positive subscale, PANSS N Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Negative subscale, PANSS G2 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale anxiety item, PANSS G6 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale depression item, YMRS Young Mania Rating Scale, AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, DUDIT The Drug Use Disorders Identification Test, ALS-SF Affective Lability Scale Short Form, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

Results from multivariate analyses in the total sample

After controlling for potential confounders, higher scores on the anxiety-depression dimension of the ALS-SF were significantly and independently associated with lower social functioning (p = 0.019; model F = 8.249, df = 11, p < 0.001). In addition, higher levels of current positive- and negative symptoms and lower premorbid social adjustment were significantly associated with lower social functioning (R2 for the final model = 0.298; PANSS N p < 0.001; PANSS P p = 0.008; PAS-S p = 0.009, see Table 3). The depression-elation and anger dimensions of the ALS-SF were not significantly associated with social functioning after controlling for potential confounders (p = 0.306 and p = 0.627, respectively). The R2 change for the ALS-SF dimensions block was 3.1%, which is a statistically significant contribution (Sig. F change 0.027). The R2 change for the first block with individual characteristics (PAS-S) was 4.2%, the illness course variables block was 1.9%, and the current symptoms block was 20.6%.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression analysis on the relationship between social functioning and affective lability in the total sample

| Covariates | Beta | t test | p value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||

| Premorbid social functioning | − 0.156 | − 2.656 | 0.009 | − 3.034 | − 0.449 |

| Duration of untreated illness | 0.004 | 0.064 | 0.949 | − 1.057 | 1.128 |

| Total number of illness episodes | 0.034 | 0.553 | 0.581 | − 0.140 | 0.249 |

| Anxiety (PANSS G2) | − 0.068 | − 0.959 | 0.339 | − 4.101 | 1.417 |

| Depression (PANSS G6) | − 0.051 | − 0.746 | 0.456 | − 3.618 | 1.631 |

| PANSS P | − 0.211 | − 2.685 | 0.008 | − 2.431 | − 0.373 |

| PANSS N | − 0.249 | − 3.650 | 0.000 | − 2.072 | − 0.619 |

| YMRS | 0.001 | 0.016 | 0.987 | − 0.924 | 0.938 |

| ALS-SF anxiety-depression | − 0.229 | − 2.357 | 0.019 | − 12.487 | − 1.113 |

| ALS-SF depression-elation | 0.091 | 1.027 | 0.306 | − 2.922 | 9.274 |

| ALS-SF anger | − 0.039 | − 0.486 | 0.627 | − 6.610 | 3.995 |

PANSS G2 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale anxiety item, PANSS G6 Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale depression item, YMRS Young Mania Rating Scale, PANSS P Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Positive subscale, PANSS N Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Negative subscale ALS-SF Affective Lability Scale Short Form

Statistically significant p values are in bold

Follow-up bivariate analyses in diagnostic subgroups

Overall, elevated affective lability was significantly and negatively associated with social functioning in both the schizophrenia- and the bipolar spectrum groups (ALS-SF total score p < 0.01, see Table 2). With respect to the ALS-SF subdimensions, the anxiety-depression and the anger dimensions were significantly associated with the SFS in the schizophrenia spectrum group (p = 0.001 and p = 0.006, respectively). The SFS was further significantly associated with current positive and negative psychotic symptoms, current anxiety and depressive symptoms, premorbid social adjustment in childhood and duration of untreated illness in this group. In the bipolar spectrum group, the association between affective lability and social functioning was significant for all subdimensions (p ≤ 0.001). Here, current anxiety and depressive symptoms and positive and negative psychotic symptoms were also significantly associated with the SFS.

Results from follow-up multivariate analyses in diagnostic subgroups

In the schizophrenia spectrum group, lower social functioning was significantly associated with lower premorbid social functioning in childhood and higher levels of current negative symptoms (p < 0.001 and p = 0.001, respectively; model F = 9.281, df = 7, p < 0.001, R2 for the final model = 0.394), in addition to trend level associations for higher levels of current positive psychotic- (p = 0.055) and depressive symptoms (p = 0.053). Affective lability (ALS-SF total score) was no longer significantly associated with social functioning after correcting for the level of positive symptoms (p = 0.685). There was also a statistically significant association between the ALS total score and the level of positive psychotic symptoms. The analysis thus indicated that the effect of the ALS on the SFS score was mediated through positive psychotic symptoms. In the bipolar spectrum group, elevated affective lability was the strongest predictor of reduced social functioning (p = 0.004; model F = 6.432, df = 5, p < 0.001; R2 for the final model = 0.164). In addition, a higher level of current positive psychotic symptoms was also significantly associated with reduced social functioning in the bipolar spectrum group (p = 0.031). Please refer to supplementary information for regression tables for the subgroups.

Discussion

Affective lability and social functioning in the total sample

In the current study, we found that higher scores on the anxiety-depression dimension of the ALS-SF were significantly associated with lower social functioning in severe mental disorders. Albeit accounting for a modest part of the total variance, this association remained at a level of statistical significance even when we controlled for other well-established predictors of social functioning such as premorbid social functioning, duration of untreated illness, and level of current symptoms. We have previously found that affective lability in our sample was characterized by fluctuations between both anxiety-depression and depression-elation across diagnostic groups [22]. However, only fluctuations between anxiety- and depressive symptoms appear to be directly linked to social functioning. As a majority of the sample (58%) consisted of individuals with bipolar disorder, it was somewhat surprising that an association between the depression-elation dimension and social functioning was not found. This might be an indication that internalizing thoughts and behaviors related to negative affectivity are more disrupting to social functioning compared to externalizing problems that may arise as a result of fluctuations in elation.

In line with some previous studies [25, 26], higher levels of current psychotic symptoms (both positive and negative) contributed the most to reduced social functioning in the total sample, highlighting the importance of achieving symptom remission. From an illness course perspective, whether the participants had previous psychotic episodes or not in their lifetime did not appear to influence the level of social functioning. In an earlier study, we found that elevated affective lability was associated with higher levels of positive psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, although directionality could not be inferred [21]. Based on the past and current findings, one may, however, speculate that targeting affective lability in treatment might be beneficial for social functioning in psychotic disorders directly but also via reducing positive psychotic symptoms. Interestingly, while affective symptoms (depressive and manic) were associated with social functioning in the bivariate analyses, their statistical significance was not upheld when entered together with affective lability into the multivariate regression model. We tentatively interpret this as support for the claim that affective lability in the anxiety-depression dimension is indeed a “trait-like” illness feature associated with social functioning independent of elevation in symptom levels.

Affective lability and social functioning in diagnostic subgroups

The follow-up analyses in diagnostic subgroups showed that the significant association between affective lability and social functioning was lost in the schizophrenia spectrum group when other predictors of social functioning were entered into the regression model. Further analyses indicated that the effect of affective lability on social functioning was largely mediated through positive psychotic symptoms in the schizophrenia spectrum group. As noted above, we have also previously reported a significant association between elevated affective lability and increased positive psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders [21]. Since elevated affective lability is considered a more stable trait that may increase the risk for reality distortion, in line with the notion of an affective pathway to psychosis [68], we interpret our findings as mediation. However, the cross-sectional study design does not rule out the possibility that high levels of positive psychotic symptoms are followed by higher affective lability. More studies, preferably using longitudinal designs, are needed to clarify these relationships in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In the bipolar spectrum group, on the other hand, affective lability remained significantly and independently associated with social functioning even when the other predictors were taken into account. Nonetheless, as our previous study showed that the level of affective lability is significantly different in BDI versus BDII disorders [22], this finding warrants further investigation in larger samples to tease out if the association between affective lability and social functioning is the same irrespective of bipolar subtype.

Putative mechanisms underlying the relationship between affective lability and social functioning

Healthy social relationships are tied to longer, healthier lives and improved psychological well-being [69]. Thus, improving social functioning should be an important treatment goal in all psychiatric disorders. In fact, research indicates that social factors such as social support and social integration are at least as important for mortality as well-established behavioral risk factors such as smoking, obesity, physical inactivity and high blood-pressure [70]. In severe mental disorders, where life expectancy has been found to be substantially decreased compared to the general population, the health-promoting effects of social factors are perhaps particularly crucial [68–70]. The results of the current study indicate that elevated affective lability may be an obstacle to harvesting the benefits of social interactions, although the directionality and the exact mechanisms by which this may exert its effects are, thus far, unclear.

Negative affect has been found to predict social functioning across schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and high levels of negative affect have been linked to greater fluctuations in affective states [10, 71]. This has again been associated with delayed return to a more adaptive affective baseline which can result in adverse health effects [72–74]. One can speculate that a pattern with elevated affective lability, high levels of negative affect and slow return to a neutral physiological state could give rise to a vicious cycle, fostering coping behaviors that are counterproductive to social functioning, such as withdrawal, avoidance and disengagement. Over time, this may interfere with the drive to forge and maintain both peripheral and close social connections [75–78], which is deleterious to well-being and longevity [79, 80]. Feeding into this potential negative cycle, social settings are in themselves triggering to a host of different affective experiences due to their ever-changing, ambiguous and unpredictable nature. Successful social navigation is therefore contingent upon having a clear representation of one’s own internal affective state to guide appropriate behavior and responses [81]. Elevated affective lability might make it distinctively more difficult to differentiate, categorize and label affective states in a precise and specific way, i.e. result in low emotional granularity [82], which has further been associated with social dysfunction [83–86]. Collectively and tentatively, affective lability may contribute to steering individuals away from the social world while features in the social world, in turn, may increase affective lability, generating negative interactions that contribute to impairments in social functioning.

Limitations and strengths

The findings of the present study must be interpreted in light of some limitations. Causal attributions are precluded due to the cross-sectional nature of the study and data on comorbid disorders such as personality disorders, ADHD and anxiety disorders are lacking. In addition, since this is a naturalistic study, the participants have typically received a broad range, as well as different combinations, of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments that would be very difficult to control for in the statistical analyses. Furthermore, as the ALS-SF and the SFS are based on self-report, there is a risk for recall- and response bias that cannot be ruled out. Finally, the measures used for anxiety and depressive symptoms are based on a scale primarily developed for assessing psychotic symptoms. Hence, the possibility that current symptoms still could have influenced the association between affective lability and social functioning cannot be ruled out completely. However, we believe that the likelihood of this is limited due to the relatively low levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The study also has several strengths; it demonstrates that there are associations between affective lability and social functioning in a large, diagnostically well-characterized sample of participants with severe mental disorders while accounting for many other well-documented confounding variables. To our knowledge, this has not been shown previously.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that elevated affective lability may have a negative impact on social functioning in severe mental disorders. If replicated, this could have important clinical implications as affective lability can be targeted in treatment through various forms of emotion regulation skills training. Future research should address whether a therapeutic focus on affective lability could be one pathway towards improving social outcomes in severe mental disorders.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend a sincere thank you to all the participants in the TOP study for their time and effort. We would also like to thank everyone at NORMENT.

Author contributions

MCH and TVL designed the study. MCH conducted the data analyses and drafted the manuscript. TVL contributed with data analyses and -interpretation and with revising the paper. IM initiated the study and together with TU provided input concerning data analyses and interpretation of results. SRA, MCH, SHO and SHL collected data. All authors were involved in critically reviewing the manuscript before approving the final version.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). The study was funded by grants from the Research Council of Norway (#181831, 147787/320, 342#67153/V50 and #288542). The organization had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The TOP study is conducted in line with the Helsinki declaration of 1975 (as revised in 2008 and 2013) and has been approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Consent to participate

All participants must be able to provide informed consent before entering the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Priebe S. Social outcomes in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;50:s15–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.191.50.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brissos S, Balanza-Martinez V, Dias VV, Carita AI, Figueira ML. Is personal and social functioning associated with subjective quality of life in schizophrenia patients living in the community? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;261(7):509–517. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0200-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bjornestad J, Hegelstad WTV, Berg H, Davidson L, Joa I, Johannessen JO, et al. Social media and social functioning in psychosis: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(6):e13957. doi: 10.2196/13957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett F, Hodgetts S, Close A, Frye M, Grunze H, Keck P, et al. Predictors of psychosocial outcome of bipolar disorder: data from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s40345-019-0169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jazaieri H, Urry HL, Gross JJ. Affective disturbance and psychopathology: An emotion regulation perspective. J Exp Psychopathol. 2013;4(5):584–599. doi: 10.5127/jep.030312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moritz S, Berna F, Jaeger S, Westermann S, Nagel M. The customer is always right? Subjective target symptoms and treatment preferences in patients with psychosis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267(4):335–339. doi: 10.1007/s00406-016-0694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhnigk O, Slawik L, Meyer J, Naber D, Reimer J. Valuation and attainment of treatment goals in schizophrenia: perspectives of patients, relatives, physicians, and payers. J Psychiatr Pract. 2012;18(5):321–328. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000419816.75752.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law H, Shryane N, Bentall RP, Morrison AP. Longitudinal predictors of subjective recovery in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(1):48–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.158428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tso IF, Grove TB, Taylor SF. Emotional experience predicts social adjustment independent of neurocognition and social cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;122(1–3):156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grove TB, Tso IF, Chun J, Mueller SA, Taylor SF, Ellingrod VL, et al. Negative affect predicts social functioning across schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Findings from an integrated data analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews JR, Barch DM. Emotion responsivity, social cognition, and functional outcome in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119(1):50–59. doi: 10.1037/a0017861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gershon A, Eidelman P. Inter-episode affective intensity and instability: predictors of depression and functional impairment in bipolar disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2015;46:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonnin CM, Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Sole B, Reinares M, Rosa AR, et al. Subthreshold symptoms in bipolar disorder: impact on neurocognition, quality of life and disability. J Affect Disord. 2012;136(3):650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanislaus S, Faurholt-Jepsen M, Vinberg M, Coello K, Kjaerstad HL, Melbye S, et al. Mood instability in patients with newly diagnosed bipolar disorder, unaffected relatives, and healthy control individuals measured daily using smartphones. J Affect Disord. 2020;271:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vodusek VV, Parnas J, Tomori M, Skodlar B. The phenomenology of emotion experience in first-episode psychosis. Psychopathology. 2014;47(4):252–260. doi: 10.1159/000357759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann SG, Doan SN. The social foundations of emotion : developmental, cultural, and clinical dimensions. 1. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Rheenen TE, Rossell SL. Phenomenological predictors of psychosocial function in bipolar disorder: is there evidence that social cognitive and emotion regulation abnormalities contribute? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2014;48(1):26–35. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Rheenen TE, Rossell SL. Objective and subjective psychosocial functioning in bipolar disorder: an investigation of the relative importance of neurocognition, social cognition and emotion regulation. J Affect Disord. 2014;162:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marwaha S, He Z, Broome M, Singh SP, Scott J, Eyden J, et al. How is affective instability defined and measured? A systematic review. Psychol Med. 2014;44(9):1793–1808. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713002407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwicker A, Drobinin V, MacKenzie LE, Howes Vallis E, Patterson VC, Cumby J, et al. Affective lability in offspring of parents with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00787-019-01355-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Høegh MC, Melle I, Aminoff SR, Laskemoen JF, Büchmann CB, Ueland T, et al. Affective lability across psychosis spectrum disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2020;63(1):e53. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Høegh MC, Melle I, Aminoff SR, Haatveit B, Olsen SH, Huflåtten IB, et al. Characterization of affective lability across subgroups of psychosis spectrum disorders. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2021;9(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s40345-021-00238-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bottlender R, Strauss A, Moller HJ. Social disability in schizophrenic, schizoaffective and affective disorders 15 years after first admission. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonsen C, Sundet K, Vaskinn A, Ueland T, Romm KL, Hellvin T, et al. Psychosocial function in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Relationship to neurocognition and clinical symptoms. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):771–783. doi: 10.1017/S1355617710000573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonnin CM, Jimenez E, Sole B, Torrent C, Radua J, Reinares M, et al. Lifetime psychotic symptoms, subthreshold depression and cognitive impairment as barriers to functional recovery in patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Med. 2019 doi: 10.3390/jcm8071046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowie CR, Best MW, Depp C, Mausbach BT, Patterson TL, Pulver AE, et al. Cognitive and functional deficits in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia as a function of the presence and history of psychosis. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(7):604–613. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy B, Medina AM, Weiss RD. Cognitive and psychosocial functioning in bipolar disorder with and without psychosis during early remission from an acute mood episode: a comparative longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(6):618–626. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morriss R, Yang M, Chopra A, Bentall R, Paykel E, Scott J. Differential effects of depression and mania symptoms on social adjustment: prospective study in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):80–91. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg JF, Harrow M. A 15-year prospective follow-up of bipolar affective disorders: comparisons with unipolar nonpsychotic depression. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(2):155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conley RR. The burden of depressive symptoms in people with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009;32(4):853–861. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upthegrove R, Marwaha S, Birchwood M. Depression and schizophrenia: cause, consequence, or trans-diagnostic issue? Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(2):240–244. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Rooijen G, van Rooijen M, Maat A, Vermeulen JM, Meijer CJ, Ruhe HG, et al. Longitudinal evidence for a relation between depressive symptoms and quality of life in schizophrenia using structural equation modeling. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewandowski KE, Cohen TR, Ongur D. Cognitive and clinical predictors of community functioning across the psychoses. Psych J. 2020;9(2):163–173. doi: 10.1002/pchj.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morriss R, Scott J, Paykel E, Bentall R, Hayhurst H, Johnson T. Social adjustment based on reported behaviour in bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(1–2):53–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossman LS, Harrow M, Rosen C, Faull R. Sex differences in outcome and recovery for schizophrenia and other psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):844–850. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velthorst E, Fett AJ, Reichenberg A, Perlman G, van Os J, Bromet EJ, et al. The 20-Year Longitudinal Trajectories of Social Functioning in Individuals With Psychotic Disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(11):1075–1085. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratheesh A, Davey CG, Daglas R, Macneil C, Hasty M, Filia K, et al. Social and academic premorbid adjustment domains predict different functional outcomes among youth with first episode mania. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanchez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aran A, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Torrent C, Vieta E, Ayuso-Mateos JL. Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: an extensive review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(5):285–297. doi: 10.1159/000228249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rymaszewska J, Mazurek J. The social and occupational functioning of outpatients from mental health services. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2012;21(2):215–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Penttila M, Jaaskelainen E, Hirvonen N, Isohanni M, Miettunen J. Duration of untreated psychosis as predictor of long-term outcome in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(2):88–94. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.127753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joyce K, Thompson A, Marwaha S. Is treatment for bipolar disorder more effective earlier in illness course? A comprehensive literature review. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2016;4(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40345-016-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gade K, Malzahn D, Anderson-Schmidt H, Strohmaier J, Meier S, Frank J, et al. Functional outcome in major psychiatric disorders and associated clinical and psychosocial variables: A potential cross-diagnostic phenotype for further genetic investigations? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16(4):237–248. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2014.995221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hower H, Lee EJ, Jones RN, Birmaher B, Strober M, Goldstein BI, et al. Predictors of longitudinal psychosocial functioning in bipolar youth transitioning to adults. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spoorthy MS, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: an overview of trends in research. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):7–29. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v9.i1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Faurholt-Jepsen M, Frost M, Christensen EM, Bardram JE, Vinberg M, Kessing LV. The validity of daily patient-reported anxiety measured using smartphones and the association with stress, quality of life and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2019;257:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW (1995) Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders: patient edition (SCID-P), version 21995

- 48.Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, Mintz J. Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P) Psychiatry Res. 1998;79(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hellvin T, Sundet K, Vaskinn A, Simonsen C, Ueland T, Andreassen OA, et al. Validation of the Norwegian version of the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Scand J Psychol. 2010;51(6):525–533. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2010.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan EHC, Kong SDX, Park SH, Song YJC, Demetriou EA, Pepper KL, et al. Validation of the social functioning scale: Comparison and evaluation in early psychosis, autism spectrum disorder and social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vazquez Morejon AJ, Jimenez G-B. Social functioning scale: new contributions concerning its psychometric characteristics in a Spanish adaptation. Psychiatry Res. 2000;93(3):247–256. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iffland JR, Lockhofen D, Gruppe H, Gallhofer B, Sammer G, Hanewald B. Validation of the German Version of the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) for schizophrenia. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0121807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneider M, Reininghaus U, van Nierop M, Janssens M, Myin-Germeys I, Investigators G. Does the Social Functioning Scale reflect real-life social functioning? An experience sampling study in patients with a non-affective psychotic disorder and healthy control individuals. Psychol Med. 2017;47(16):2777–2786. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717001295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oliver MNI, Simons JS. The affective lability scales: development of a short-form measure. Pers Indiv Differ. 2004;37(6):1279–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2003.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aas M, Pedersen G, Henry C, Bjella T, Bellivier F, Leboyer M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Affective Lability Scale (54 and 18-item version) in patients with bipolar disorder, first-degree relatives, and healthy controls. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Look AE, Flory JD, Harvey PD, Siever LJ. Psychometric properties of a short form of the Affective Lability Scale (ALS-18) Pers Individ Dif. 2010;49(3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8(3):470–484. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Mastrigt S, Addington J. Assessment of premorbid function in first-episode schizophrenia: modifications to the Premorbid Adjustment Scale. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(2):92–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wechsler D (2007) Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. Norwegian Manual Supplement. Pearson Assessment, Stockholm

- 61.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Berman AH, Bergman H, Palmstierna T, Schlyter F. Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxification settings and in a Swedish population sample. Eur Addict Res. 2005;11(1):22–31. doi: 10.1159/000081413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jaworski F, Dubertret C, Ades J, Gorwood P. Presence of co-morbid substance use disorder in bipolar patients worsens their social functioning to the level observed in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185(1–2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bahorik AL, Newhill CE, Eack SM. Characterizing the longitudinal patterns of substance use among individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness after psychiatric hospitalization. Addiction. 2013;108(7):1259–1269. doi: 10.1111/add.12153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Høegh MCMI, Aminoff SR, Haatveit B, Olsen SH, Huflåtten IB, Ueland T, Lagerberg TV. Characterization of affective lability across subgroups of psychosis spectrum disorders. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s40345-021-00238-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Myin-Germeys I, van Os J. Stress-reactivity in psychosis: evidence for an affective pathway to psychosis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(4):409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haslam SA, McMahon C, Cruwys T, Haslam C, Jetten J, Steffens NK. Social cure, what social cure? The propensity to underestimate the importance of social factors for health. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson SL, Tharp JA, Peckham AD, McMaster KJ. Emotion in bipolar I disorder: Implications for functional and symptom outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(1):40–52. doi: 10.1037/abn0000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Koenigsberg HW. Affective instability: toward an integration of neuroscience and psychological perspectives. J Pers Disord. 2010;24(1):60–82. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dargel AA, Volant S, Brietzke E, Etain B, Olie E, Azorin JM, et al. Allostatic load, emotional hyper-reactivity, and functioning in individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22(7):711–721. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dargel AA, Volant S, Saha S, Etain B, Grant R, Azorin JM, et al. Activation Levels, cardiovascular risk, and functional impairment in remitted bipolar patients: clinical relevance of a dimensional approach. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(1):45–47. doi: 10.1159/000493690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brent LJ, Chang SW, Gariepy JF, Platt ML. The neuroethology of friendship. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1316:1–17. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull. 2005;131(6):803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bjornestad J, Joa I, Larsen TK, Langeveld J, Davidson L, Ten Velden HW, et al. “Everyone Needs a Friend Sometimes”—social predictors of long-term remission in first episode psychosis. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1491. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sandstrom GM, Dunn EW. Social interactions and well-being: the surprising power of weak ties. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014;40(7):910–922. doi: 10.1177/0146167214529799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(3):578–583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511085112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(3):774–815. doi: 10.1037/a0035302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(7):865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Erbas Y, Ceulemans E, Blanke ES, Sels L, Fischer A, Kuppens P. Emotion differentiation dissected: between-category, within-category, and integral emotion differentiation, and their relation to well-being. Cogn Emot. 2019;33(2):258–271. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2018.1465894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kashdan TB, Barrett LF, McKnight PE. Unpacking emotion differentiation: transforming unpleasant experience by perceiving distinctions in negativity. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2015;24(1):7. doi: 10.1177/0963721414550708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kimhy D, Vakhrusheva J, Khan S, Chang RW, Hansen MC, Ballon JS, et al. Emotional granularity and social functioning in individuals with schizophrenia: an experience sampling study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, Weiss NH, Rosenthal MZ. A preliminary examination of the role of emotion differentiation in the relationship between borderline personality and urges for maladaptive behaviors. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2014;36(4):616–625. doi: 10.1007/s10862-014-9423-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Suvak MK, Litz BT, Sloan DM, Zanarini MC, Barrett LF, Hofmann SG. Emotional granularity and borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120(2):414–426. doi: 10.1037/a0021808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available upon reasonable request.