Abstract

At the beginning of 2020, feelings of fear and uncertainty spread throughout the world after the novel coronavirus rapid propagation. The world was not ready to face such a situation. Countries implemented emergency measures to contain it, which included social distancing and shutting down the economy. Social and economic impacts were unpredictable. This manuscript aims to present the application of a remote scenario planning method that identifies threats, opportunities, and subsidies to a strategic evaluation in a short term. The main results identified 15 key trends, four critical uncertainties, four scenarios, ten opportunities, and 13 threats. They were debated and presented to some Brazilian organizations' decision-makers to help develop strategies to curb the aftermath of COVID-19. Our findings show that it is possible to use this agile method to build consistent and coherent scenarios that support the decision-making process. Part of the experts said that participating in the process was essential to comprehend it better. The process also contributed to their learning process and their organization on anticipatory strategy thinking concerning possible future. They agree that the scenarios were relevant, defiant, and plausible and incorporated meaningful events and real challenges to their organizations' strategy formulation or decision-making.

Keywords: Mini-scenarios method. COVID-19. Crisis. Strategies. Brazil

1. Introduction

At the beginning of 2020, uncertainties spread throughout the world after the rapid spread of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), followed by the World Health Organization (WHO) statement that there was a global pandemic. The mortality rates were high in some countries, such as Italy (Grasselli, 2020). Several countries were caught off-guard, including Brazil. Governments took emergency measures; however, they were implemented without readiness or preparedness to deal with the disease, e.g., shutting down economic activities, suspending face-to-face classes, imposing restrictions on leisure activities, and other social distancing measures.

If the pandemic persists for a long time, the world will be left with catastrophic and disproportionate social and economic impacts. It is not easy to make decisions when there is a high level of uncertainty. Nevertheless, humanity is facing unprecedented challenges. The information available when the contamination started was vague, inaccurate, and hard to understand. In this situation, scenario-building can bring significant contributions. Even though it is a method that takes time to be applied, it is helpful in the decision-making process. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct this method differently, adapting it to the social distancing reality and making it applicable for short-term contexts.

This research aims to meet the needs of appropriate scenario planning method to be used in crises. One of the key aspects was adapting the usual scenario planning method to help its construction and analysis at critical moments. With this method, valid short-term results can help in risk analysis, decision-making, and short-time horizon strategy formulation. However, due to significant constraints, it must be a method that can be used entirely remotely with experts’ participation. In the short term, this manuscript aims to present the application of a remote scenario planning method that identifies threats and opportunities and subsidies to strategic evaluation in a short term. Therefore, the research question is: Is it possible to build scenarios remotely using a network of experts and provide subsidies to the decision-making process in the short term?

Our paper includes the findings of the “Post-COVID-19 Scenarios” project. It was carried out entirely remotely by the Mackenzie Brasilia Presbyterian College Foresight Research and Study Group. The group members are specialists in scenarios that work in the public or private sector. Therefore, their participation in this project was essential to develop results that could be embedded into their activities and the institutions.

Since the project was a contribution from civil society, it was not targeted at any specific decision-making organizations. The research was carried out entirely voluntarily, without funding or sponsorships. Thus, it does not present suggestions for specific decision-makers but describe the positive and negative impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic, opportunities, and threats that might result from possible decisions and partnerships signed between actors in each scenario. In the face of opportunity, the research group developed scenarios to test a quick method in a turbulent and crisis context. Unfortunately, the country had few institutions with the competence and the agility to develop national scenarios quickly.

Some outcomes point to the success of this project, such as the expert’s participation and the invitations received for the final report presentation. Also, the statements of key stakeholders in the e-book7 launched show the value of this method. Furthermore, the results achieved in the planning processes reached some of the most relevant national institutions, i.e., the Government Secretariat (SEGOV), the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa), and the Brazilian National Confederation of Industry (CNI), which show the importance of this project. Thus, the agile scenario development conducted entirely remotely can embrace different decision-making bodies in local and national institutions.

The project started only six days after the WHO had declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The project took two months to be completed. The results of each step were reported to experts to support their considerations for the following step. In total, 390 experts from different fields, such as health, economics, humanities, social sciences, geopolitics, security and defense, engineering, and information and communication technologies, participated in this project. The guiding question was: Will Brazil have been successful in dealing with social and economic challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic by 2022?

A more comprehensive literature review on this topic is presented. We highlighted key points used in this method, premises, the mini-scenarios method, the importance of experts, and position and dispersion statistics measures. The method used in this research, the results obtained, and the surveys carried out are detailed in this paper. Experts’ profiles have also been included. Finally, we conclude with our findings and considerations at the end.

2. Literature review

The literature review highlights the theoretical contributions made to use a method to build scenarios in a unique environment, for social distancing was one of the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although several studies, for instance, Øverland (2000), Karlsen and Øverland (2012), Parandian and Rip (2013), and Karlsen (2014), have defined mini-scenarios, its meaning differs from what it was previously presented.

2.1. Critical aspects in method

Three central questions were used to guide the literature review: (1) What is a scenario? (2) What is the mini-scenarios method, and why should we build it? (3) Which main concepts support the method?

The answer to the first inquiry is that a scenario is a possible future with a logical hypothetical sequence of events necessary to lead mankind to present conditions. However, for these logical sequences of hypotheses to be considered a scenario, they need to meet five driving forces: "pertinence, coherence, verisimilitude, importance and transparency" (Godet, 2000, p. 26; Durance & Godet, 2010). Therefore, it is paramount to identify how various forces and events are intertwined and use these findings to build scenarios. Scenarios can also be perceived as stories about the future, not a future reality. They are a figurative interpretation that provides input for better decision-making processes (Wack, 1985, Schwartz, 1991, Bishop et al., 2007, Elsawah et al., 2000). For Kahn and Wiener (1967), scenarios are future narratives that focus on causal processes and emphasize decision nodes.

As a method that aims to create conditions for positive changes, scenarios can use images of the future as any cultural, artistic expression of possible futures. People usually can picture iconic images of the future in their minds. These can be used to construct scenarios while building optimistic and pessimistic imageries of the future to create positive changes. Scenarios usually include images of the future and an account of the causal flow of events leading from the present to such future conditions (Gallopín, 2012).

This process is time-consuming. In general, it takes from eight months to two years to be completed (Godet, 2006, p. 110; Chermack & Coons, 2015). For example, the Brazil 2035 scenarios (Marcial, 2017) took 18 months to be developed; the Global Trends, developed by the National Intelligence Council (2017), took two years to be completed. However, notwithstanding the time it usually takes to carry out a scenario study, the transitions to the new world are increasingly faster, requiring faster and less costly methods.

The mini-scenarios method is a short-term project with simplified steps and a retrospective analysis withdrawal. As Marcial (2011b) described, using the mini-scenarios method is a way to adapt to this new era. In addition, we only worked with expert perceptions of a particular subject and did not invest time in collecting other data. In the short term, this method aims to guide building plausible, consistent, and coherent scenario processes for specific strategic issues, which present a high level of uncertainty, meeting the opportunity principle in the competitive intelligence field.

Therefore, a control team can build scenarios with expert participation in different brainstorming sections. The professionals responsible for the scenario-building process are part of the Control Team, which must meet the following requirements: experience, technical competence, permanently update responses to the guiding question, and macroenvironment movements (Marcial and Grumbach, 2010, Smart, 2019). Experts are individuals that are selected for specific reasons, e.g., they must be able to perform subjective assessments beyond disciplinary boundaries, deal with complex problems, and understand multiple ever-changing factors, in addition to identifying alternative paths, according to a survey carried out by Mauksch, von der Gracht, and Gordon (2020).

Scenario-building begins when the central question has been defined. The central question shows the issue that motivates and guides the scenario-building process. Its objective is to define the focus of the project. The guiding question motivates how scenarios are built, and it seeks to lead them towards a single focus. This guiding question needs to be broken down into its fundamental aspects, representing the main topics that make up the working framework or situation framework (Schwartz, 1991, Godet, 1993; Vaitman, 2001).

It is also necessary to specify: (1) the time horizon: a period that the scenario study will cover; (2) its geographic range – geographic location of its scope, i.e., state, regional, country, or global levels; (3) its purpose – what the study is for, or what the receiver needs the study for in the future; (4) to whom it is meant for – to whom the work is intended; and (5) the goal – what product will be delivered at the end.

Another important aspect lies in the use of future seeds. They represent facts or signals in the past and present that inform concerned parties about the possibility of future events and indicate a set of variables with different characteristics, e.g., trends, critical uncertainties, and ruptures (Marcial, 2011bb, Marcial, 2011aa). Future seeds can also be a high-frequency signal, for example, a trend or a weak frequency signal (Ansof, Igor, and McDonnell, 1993). For these reasons, it is imperative to identify future seeds in this process.

Trends are a prevailing tendency or inclination, a general movement, or a development line (Merriam-Webster, 2020). Godet (1993) defined trends as variables that will control their behavior and cannot be overlooked in scenarios given the force they exert on the environment. In turn, a break is a change in trend direction, which can sometimes be sudden and irreversible. The rupture is a different way of doing things (Aulicino & Fishman, 2020, p. 477). Uncertainties are future events with highly unpredictable behaviors. Critical uncertainties are the questionable occurrence of events, but with great importance for the guiding question and bring significant ambiguity to the environment. The main critical uncertainties will modulate the scenario (Schwartz, 1991).

The Global Business Network uses the orthogonal axes construction to define the scenario-building logic. These axes, which are 90º apart, represent the main critical uncertainties, forming a matrix force (Schwartz, 1991, Rhydderch, 2017). These forces are identified in the analysis of critical uncertainties, and they are those that better describe the dynamics of the current situation and communicate the main point more effectively. Thus, its construction facilitates scenario identification (Schwartz, 1991, Ramirez and Wilkinson, 2014).

Once the orthogonal axes are built and each scenario logic is identified, the next step is to write the ideé -force. The ideé -force of a scenario is the main idea in the story. The challenge is to facilitate the plot identification that best describes the dynamics of the situation and communicates the main point effectively by telling good stories about the future (Kenney and Pelley A., B, 2014, Raven and Elahi, 2015, Schwartz, 1991, van’t Klooster and van Asselt, 2006).

Morphological analysis is a method used to explore possible futures based on combining the evolution of subsystems resulting from a given system within the work scope. After elaborating each subsystem’s hypotheses, scenarios are constructed by logical and coherent combinations among those hypotheses. These combinations represent the possibility of the morphological space (Godet, 2000; Durance & Dias, 2008; Johansen, 2018).

2.2. The mini-scenarios method

Marcial (2011b) described the mini-scenarios method as a tool to respond to specific strategic questions of considerable uncertainties raised by the competitive intelligence field. This method reduces the scenario-building process time; it is suitable for situations that do not involve long-term prospects and for subjects that you already have a network of experts. Brainstorming is the most used instrument, for it eliminates the retrospective analysis.

This method is called the mini-scenarios method because it was designed for short-term projects. Therefore, its steps have been simplified, and the retrospective analysis was withdrawn. Moreover, we only worked with the experts' perceptions of a particular subject and did not invest time in collecting other data. Thus, it is a method that has reduced the amount of work and time used in predicting future events.

This method has seven steps: (1) work plan definition; (2) future seeds definition; (3) driving forces definition; (4) scenario-building; (5) consistency tests, adjustments, and dissemination; (6) scenario analysis and strategy definition; and (7) strategic monitoring (Marcial, 2011b). Experts, especially those external to the organization, must replace the retrospective analysis stage to ensure process quality. Instead, they add other perspectives based on their critical issues knowledge and give detailed estimates about the future.

2.3. The use of position and dispersion statistic measures

Position statistic measures, or central tendency, indicate values that typify or represent a set of numbers. Measures often used are average, median, and mode. Dispersion statistic measure indicates whether values are relatively close to each other or more separated. The most common dispersion statistic measures are standard deviation and variance. It is not usual to use statistical measures of position and dispersion during the scenario-building process.

3. Materials and methods

The method used was adapted based on the mini-scenarios method. Our project lasted 65 days. It started on March 17th and ended on May 21st, 2020, when the last report was issued. Experts involved in the process received reports with results of each step to support their considerations on the following step.

Four hundred and seventeen experts formed the population, a list defined by the Control Team. The list contains (1) members of Rede Futuro – a Brazilian direct chat application group with 168 participants that debate concerns about the future (group created on June 9th, 2017); (2) professionals and researchers of public and private institutions from various fields, such as health, economics, humanities, social sciences, geopolitics, national security and defense, engineering, and information and communication technologies. The first three surveys were sent to the entire population, while the consistency test and adjustments were sent only to 30 experts chosen from among the population elements. The last survey was sent only to those who had participated at least once. In total, 390 experts participated from more than 110 different organizations have participated.

The methods to experts' selection are based on the sociological, behavioral, and cognitive views. Therefore, the choice was based on methods associated with the sociological and cognitive views. The methods were: social acclamation (experts selected by peer nomination); personal involvement (selection based on personal interest in the subject); external cues (assessment based on externally available criteria, e.g., years on the job, job position, certification, publications) (Mauksch et al., 2020).

Due to the pandemic, the project was carried out entirely remotely. Several instruments were used to make this research feasible. Therefore, we divided them into two classes: Control Team and experts. The Control Team members consisted of six Ph.D. researchers working in three different cities in Brazil: Brasília, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. They worked all the time remotely. With them, we used: (1) a group in a free direct online chat application, which was explicitly created for the project, as a mean to exchange messages and coordinate activities; (2) a free internet file storage and synchronized folder for sharing ideas, a means of joint construction, and debates on a free web-based spreadsheet platform that can be created, edited, and stored online in real-time, and a free web-based documents tools to edit and store content online and in real-time; (3) free video conference platform to hold virtual meetings to build each step, carry data analysis and obtain each step results.

We used a free web-based tool to collect information from experts to create a form for data collection and sent e-mails regarding consistency testing and adjustments. In addition, we used a direct online chat application and e-mails to inform participants about our research, e.g., send messages to the Rede Futuro group.

The data analysis process consisted of two steps: handling and prioritization. First, we started with handling, analyzing, and removing repeated future seeds and integrating similar ideas. Next, these variables were grouped into major themes, and a new synthetic process was conducted until there was a final list of variables.

The method used to prioritize the variables followed the rules described below:

-

•

Scale of importance for the success of the focal issue described in the guiding question: The variable can assume values from 1 to 5, in which “1” was for low relevance and “5” for great importance.

-

•

Percentage regarding the chance of an event occurrence: The variable can assume values from 0% to 100%, representing chances of an event happening in the future. In this situation, the value "0" represents no risk of future occurrences, for it indicates 100% certainty that the event will undoubtedly happen in the future. It is noteworthy that the extremes are classified as low uncertainty and values between 40% and 60% high uncertainty.

-

•

Scale of urgency involved taking advantage of the opportunity to exit the crisis: The variable can assume values from 1 to 5, “1” for low urgency, and “5” for high urgency.

-

•

Scale of severity of the existing limitations involving the crisis: The variable can assume values from 1 to 5, “1” for low severity, and “5” for high severity.

This evaluation was carried out individually and remotely by all Control Team members and two other guest experts. The results were subjected to statistical calculations of the mean, median, and standard deviation to reduce cognitive bias. The Control Team used the median as a measure of convergence, and then successive evaluations were made. In all cases where the standard deviation was low, convergent assessments were considered, and their median rating was approved as an answer. Those that obtained a high standard deviation were submitted to new rounds through a debate via a free video conference platform with the Control Team members to obtain convergence around the median through consensus.

The method used followed the six steps described below. First, we combined the experts' perception of the future and the results of the analysis carried out by the Control Team. Also, we combined their choices regarding the results of handling and prioritization processes focused on convergence opinion.

3.1. Scenario system delimitation

In this step, the Control Team defined the scenario system, set the guiding question, its fundamental aspects, aim, purpose, time horizon, geographical range, and to whom the designed scenario is.

To create the list of fundamental aspects, the Control Team asked the experts: “In your opinion, what are the main issues and stakeholders to be analyzed so that the following question can be adequately answered?” Then the experts were asked to use prioritization by making a list of up to five key aspects. Finally, to obtain the results, the Control Team handled the answers.

3.2. The identification of future seeds

The second step entails expert consultation to identify future seeds. Thus, trends, uncertainties, and ruptures regarding the guiding question and its fundamental aspects were raised based on expert perceptions about the future. Then, the Control Team handled and prioritized these future seeds.

We sent a questionnaire with three questions to the experts: (1) “In your opinion, what are the main trends regarding the guiding question and its fundamental aspects until 2022?”; (2) “In your opinion, what are the main uncertainties or ruptures regarding the guiding question and its fundamental aspects until 2022?”; (3) “In your opinion, what are the main disruptions that could occur regarding the guiding question and its fundamental aspects until 2022?”. In the uncertainties and disruptions case, exploratory events were sought.

The questionnaire contained a description of the fundamental aspects and guiding question generated in the previous step. In all questions, each future seed's meaning was included to guide answers. Finally, the prioritization exercise was requested, listing five variables for each future seed type.

The results underwent a handling process. First, the Control Team considered all the disruptions as uncertainties events. Then, all future seeds underwent a prioritization process. Finally, an uncertainties list was created with only those that obtained great importance concerning the guiding question and high uncertainty concerning the environment, based on the chance of occurrence. The selected trends obtained high importance regarding the guiding question and a high chance of occurrence. The rest were eliminated.

3.3. The driving forces: critical uncertainties and key trends

The third step was to identify the driving forces, which focused on critical uncertainties and key trends. For the construction of key trends, the ones that achieved convergence in the previous step were submitted to the Control Team's handling. They initially grouped trends to identify forces about the behavior of these variables. Then, a new integration and wording adjustment process was conducted to summarize and explain the critical movement (great force in action), resulting in the key trends.

The Control Team conducted a survey submitting the list of uncertainties for expert evaluation. In the questionnaire, they explained what critical uncertainty is. For each future event listed, experts needed to decide the importance of classification concerning the guiding question (from 1 to 5) and the chance of future events occurrence (from 0% to 100%). The Control Team used the scheme in Fig. 1 to convert the occurrence percentage to the degree of uncertainty. With this kind of scale, the information we received was more accurate, which led to better interpretation. These results were submitted to a new prioritization process by the Control Team, which evaluated variables that did not achieve convergence (high standard deviation). Through consensus, they got an opinion convergence.

Fig. 1.

– Assessment of the uncertainty degree (Marcial, 2019, slide 136). Note: Chance means the percentage of the event occurrence probability.

Variables with high importance (median equal to 5) and high uncertainty (median range from 40% to 60%) were evaluated independently. In the following step, we used only those that were independent.

3.4. Scenario logic definition

In this step, the Control Team generated four scenarios using critical uncertainties according to the experts' answers consulted in the former step. First, each Control Team member reflected on the critical uncertainties and suggested fundamental axes of critical uncertainties and potential scenarios resulting from the combination of these axes. Then, each member presented their proposal in a virtual meeting. Finally, the group analyzed and debated all of them in a qualitative debate that the leader moderated. Again, they did not use any foresight tools to help this debate.

Next, they eliminated similar hypotheses and assessed the remaining scenarios in terms of possible occurrence and whether hypotheses were consistent and coherent. It is necessary to have only independent uncertainties in the axes and their combination. The next step evaluated the strategic message each scenario showcased, narrowing it down to four written hypotheses that carried out the main message. In the end, they held a remote brainstorming to name each scenario.

3.5. Writing and evaluating scenarios

Guided by the scenario logic defined in the former step, the Control Team wrote four scenarios. To define each plot, the Control Team had four online meetings. First, they discussed how we would tell each future story, what each message should be, and which ones were essential. Then, to build together a matrix similar to the morphological analysis. Lines were the variables (critical uncertainties and key trends), and column headers contained the names of scenarios. Finally, we inserted each variable behavior concerning the ideé -force of each scenario in the matrix.

In another online meeting, the Control Team defined how to write each scenario and which formats to use, e.g., e-mail, newspaper, and blog. To synthesize ideas and highlight strategic foci in every scenario, we limited the length of stories to no more than four pages. Afterward, each Control Team member wrote the scenario script, highlighting each story's main characteristics and impacts. The scenario building started from the future situation unfolding the critical uncertainties and analyzing the connection between the variables (trends, uncertainties, and actors' strategy) and events, allowing one to move forward from the actual situation to the future situation.

The trajectory of each scenario building was illustrated in the narratives using fictitious events. They presented the behavior of each variable and its influence on each other in the future direction. With each storytelling, all the Control Team members read it, and they conducted online debates until each story was ready to be assessed by the experts.

We sent four stories about the future by e-mail to 30 experts representing all categories and knowledge of the main themes covered in the scenarios. The objective was to assess the consistency and coherence of those scenarios. Some questions were designed to guide this assessment and should be asked in all scenarios: (1) “Is the plot possible/likely to occur? If not, please justify your answer”; (2) “Are cause and effect relationships possible, and correct? If not, please justify your answer”; (3) “Are the actors mentioned responsible for the results described? Is the role of these actors and the relationships between them clear? If not, please justify your answer”; (4) “Are the disruptions described possible within the described scenario? If not, please justify your answer”; (5) “What questions need to be adjusted/changed? Please, send suggestions''.

The Control Team evaluated all suggestions and made the necessary adjustments to the scenarios. Doubts about discussions, proposals, and adjustments were dealt with by experts directly via e-mail or a free online direct chat application.

3.6. Strategic evaluation

This step refers to the strategic analysis of scenarios by identifying opportunities and threats in each scenario presented. To this end, we carried out a new survey via e-mail with the 390 experts who had participated in at least one of the former steps.

We requested the following: (1) an understanding of those scenarios; and (2) an evaluation to identify the main opportunities and threats that could impact strategies to be adopted by Brazil in the face of the COVID-19 crisis. In order to guide this assessment, we designed the following situation to be considered for each scenario: “You have to identify up to three opportunities and three threats that each scenario presents up to 2022 for Brazil to be successful in dealing with social and economic challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic”. The Control Team handled and prioritized results concerning its importance and the guiding question, and its urgency (for an opportunity) or severity (for threat). Those that obtained the highest score (highest urgency and severity) in both items formed the list of prioritized opportunities and threats.

In September 2021, the Control Team evaluated the scenarios built, accessing participants’ opinions concerning their value and usefulness. An online survey with eight questions was submitted to 86 participants who answered this last step. In fact, respondents read the scenarios’ contents. We developed this questionnaire based on Chermack (2007). The objective was to verify if respondents used the four scenarios in their organization’s decision-making and if the scenarios built were essential to the organization. Respondents were asked to respond on a discrete five points scale from totally disagree to totally agree.

4. Results

In Table 1, we can see the products generated at each step. Most of them result from the structure, execution, and analysis of five remote consultations with experts, handling, and prioritizations performed by the Control Team. As a strategic planning method, scenario-building is not an end in itself. To better support the strategic planning process, it is necessary to indicate the threats and opportunities in each scenario. Thus, decision-makers can establish strategies for each scenario according to the main threats and opportunities.

Table 1.

Project steps, results, and experts’ contributions.

| Steps | Products | Experts’ contributions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Scenario system delimitation | Fundamental aspects | They sent their opinion concerning fundamental aspects |

| 2. Identification of future seeds | Trends, uncertainties, and disruptions | They sent their opinion concerning the trends, uncertainties, and disruptions |

| 3. Driving forces | Key trends and critical uncertainties | They defined the key trends and critical uncertainties |

| 4. Orthogonal axes and scenario logic establishment | Scenario logic and ideé -force | |

| 5. Scenario: writing and validation | Scenario: written and validated | They validated the scenarios’ logic and the texts on scenarios |

| 6. Strategic evaluation | Opportunities and threats | They sent their opinion concerning the most critical opportunities and threats from the scenarios analysis |

Table 2 summarizes the number of experts who participated in each step, the total of valid responses, and the number of topics summarized by the Control Team.

Table 2 –

Responses received summary and summary prepared by the Control Team.

| Query |

Number of Experts |

Total valid responses |

Total synthesized topics * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Fundamental aspects of the survey | 195 | 1050 | 5 |

| 2) Future seeds survey | 167 | 1618 | 39 |

| Trends | 738 | 15 | |

| Uncertainties or ruptures | 880 | 24 | |

| 3) Identification of critical uncertainties | 212 | 24 | 4 |

| 4) Consistent test | 30 | NA. | NA. |

| 5) Strategic analysis | 86 | 1865 | 23 |

| Opportunities | 943 | 10 | |

| Threats | 922 | 13 |

Note: * Topics summarized by the Control Team.

The main results of each stage are described below. First, we summarized the profiles of experts who participated in the project presentation. Most experts hold a master’s degree, Ph.D.'s degree or have conducted post Ph.D. research (69.2%). Experts come from several different knowledge fields (Geopolitics, security, and defense (22.6%); Human sciences (17.8%); Engineering, Computing, and ICTs, Physics, Mathematics (17.8%); Economy (15.9%); Other applied social sciences (11.0%); Health, (5.8%); Agronomy (3.9%) and 5.2% from other fields); therefore, they covered the fundamental aspects of our study. They represent the diversity in each of their fields, i.e., 32.1% of experts come from educational and research institutions (public or private), 31.8% from public administration, and 23.1% from public, private, or mixed economy companies. They are from more than 110 different organizations.

It is essential to clarify that, in this project, the experts' contributions were important to help the Control Team, i.e., to define the scenario-building process focus, to indicate the trends, uncertainties, and possible ruptures, to select the critical uncertainties, to assess the consistency and coherence of those scenarios' storytelling, and to realize the strategic scenario analysis by identifying opportunities and threats in each scenario presented. First, the Control Team analyzed all the contributions, prioritized them, and integrated them. Then, they used the information to create the scenarios using the critical uncertainties and use storytelling to write each scenario.

4.1. Scenario system delimitation

The following scenario system was defined taking into consideration six aspects: (1) the guiding question: “By 2022, will Brazil be successful in dealing with social and economic challenges caused by the new coronavirus pandemic?”; (2) objective: to generate scenarios of possible economic and social impacts for the post-pandemic coronavirus period in Brazil; (3) purpose: to conduct an exploratory analysis to provide public and private stakeholder support in policy-making strategies; (4) defining public and private stakeholders; (5) time horizon: 2020–2022; and (6) geographic space: Brazil, considering its dimensions.

Based on these specifications, the first experts’ survey helped define the critical aspects of the guiding question. We received 1050 responses from 195 experts, resulting in five fundamental aspects: economy, society and demography, health and environment, geopolitics and international relations, and institutional politics.

4.2. Identification of “future seeds”

To help identify “future seeds,” 167 experts answered the questionnaire. In total, we collected 738 trends, 464 uncertainties and 416 possible disruptions. We consider all the ruptures as uncertainties events and handled in an integrated manner. As a result of this analysis, the Control Team nailed down 24 uncertainties and 64 trends.

4.3. Driving forces

The third step of the project resulted in identifying key trends and critical uncertainties. Two hundred twelve experts answered the survey regarding the degree of importance and uncertainty of the 24 uncertainties identified in the previous step. After the analysis carried out by the Control Team, we found a total number of 13 critical uncertainties, which proved to have a high degree of importance and uncertainty. Then, there was independence among them, and we selected four independent critical uncertainties: (1) World economic and geopolitical activity; (2) Therapeutic and health infrastructure responses to the pandemic; (3) Cooperative or conflictive government action; (4) Strategies to mitigate the social and economic impacts of COVID-19.

Fifteen key trends were summarized, including an increase of barriers to international trade; an increase of investments in science, technology, and innovation (ST&I) in the health and bioscience fields; an increase of the Brazilian industrial base in health; faster access to information and communication technologies and automation, a strengthening of the digital economy; a rise of new types of work that require new skills; a strengthening in the role of the state with enlarged public spending and debt; an economic slowdown and instability with a rise in unemployment, informality, and impoverishment.

4.4. Establishment of orthogonal axes and scenario logic

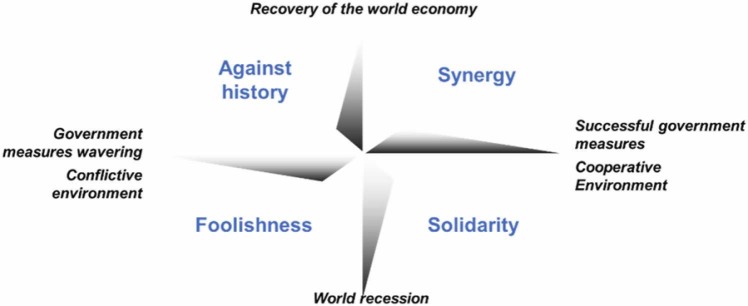

Two axes were obtained from the independent critical uncertainties identified that synthesized the four hypotheses that originated the four scenarios ( Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The post-COVID-19 scenarios logic in Brazil.

Based on these hypotheses, the Control Team wrote the scenario logic (or ideé-force) of each scenario and defined their names, as seen below.

Synergy Scenario – In 2022, the world economy had already resumed its growth. Brazil shows signs of leaving the crisis caused by COVID-19. After major national demonstrations, the three government branches built a pact. Public-private cooperation became strong. The Brazilian state had corresponding institutional stability, organized the activities resumption in a "new normal" setting, and promoted the digital economy expansion. The first returns are reaped, particularly in technology and incremental innovation, initiated with investments made in science, technology, innovation, and the healthcare industry. Despite differences, the priority was the nation's welfare by enabling economic and social improvement through synergistic partnerships.

Against history Scenario – Global economic recovery is on its way, but disputes among countries are likely to limit international trade. Brazil suffered a social crisis and dealt with divergences between relevant public and private actors. Brazilians face an economic crisis, for the economy is stagnant due to governmental policies' low effectiveness. There is a conflictive environment among the three State powers and federal and subnational governments. Brazil goes against history.

Nonsense Scenario – Countries are unable to make a quick economic recovery. The world enters a prolonged recession, which increases tension among major world powers and worsens the deteriorating geopolitical environment. In Brazil, little was done during and after the crisis. Due to the complete lack of federal governance, coordination between federated entities, and the hard struggle between the three government branches, Brazil cannot carry out the necessary reforms to recover domestic and foreign market dynamics. It is a preposterous situation in the face of a pandemic.

Solidarity Scenario – Brazil overcomes the pandemic better than other countries affected by the COVID-19 outbreak and world recession. The unprecedented intensity of global and domestic crises led to a new pact that created a collaborative atmosphere among Republic powers, Federal administration, States, and society. It also enabled effective government measures to mitigate health, economic, and social crises and give the economy stimuli through a development plan. Thus, solidarity led the country to swim against the tide of a world crisis.

4.5. Writing scenarios

The Control Team wrote the scenarios in a playful and easy-to-understand format. Synergy was written as a news article published on a fictional news blog on September 7th, 2022, the 200th year celebration of Brazil Independence Day. The Against history scenario is a retrospective analysis published in a fictional newspaper on the eve of the Brazilian presidential election in 2022. Nonsense is told via e-mail. A Brazilian industry businessman sent an e-mail to a friend, a businessman, in Spain. He writes about the pandemic and post-pandemic period in Brazil. Solidarity is told as a made-up investment bank report published on November 3rd, 2022, presenting a retrospective analysis of the situation.

4.6. Strategic evaluation

The written scenarios were evaluated by 86 experts, who identified 943 opportunities and 922 threats concerning the four scenarios built, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of opportunities and threats generated by experts by scenario.

| Scenarios | Threats | Opportunities | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - Synergy | 220 | 238 | 458 |

| 2 - Against history | 236 | 229 | 465 |

| 3 - Nonsense | 243 | 235 | 478 |

| 4 - Solidarity | 223 | 241 | 464 |

| Total | 922 | 943 | 1865 |

After analysis and prioritization conducted by the Control Team, ten opportunities were identified. If taken urgently, they would expedite a successful exit from the post-COVID-19 crisis. They also identified 13 threats that, due to their severity, would not favor a successful crisis exit, indicating they should immediately be eliminated and neutralized or have risks managed.

Here are some of the opportunities: favorable environment for carrying out institutional reforms (political, fiscal, tax, better balance between federal powers and entities); adaptation of labor laws to new work models and businesses, as well as long-term planning and investment in the country; increase of public and private investments in economic and social infrastructure; promotion of practices to overcome economic bottlenecks; improvement of productivity and competitiveness of Brazilian economy; employment generation; integration between quality, technical and higher education, with advances in distance learning and focus on current and future labor market needs; gradual increase in ST&I investment through public, private and university partnerships; expansion of incremental innovations, industrial reconversion and incentives for startup creation and talent retention in Brazil; progress of the social protection network with improvement in the Human Development Index, contributing to reducing inequalities, stimulating cooperation and investment in social well-being.

Some of the threats are: difficulties across global supply chains; intensification of an economic and geopolitical dispute between world powers (mainly China and the United States); prolonged economic recession, low use of installed capacity in the industry, risk of a supply shortage crisis, and the fraying of the productive fabric and labor market, hindering resumption of productive activities; an environment that is not favorable to entrepreneurship and financing/credit accentuates business failures and increases the challenge for creating new ones; ineffective phasing out of social distancing and non-universalization of the vaccine against COVID-19, with pandemic resurgences, contribute to the collapse of the healthcare system and increase in deaths; concentration of resources for COVID-19 can limit actions of other health focuses, i.e., primary care, disease prevention, and health promotion.

It is essential to highlight that the Control Team made final adjustments in the scenarios in this step because some experts sent some new contributions.

4.7. Communication of project results

Although this was a contribution from civil society, we focused on state-level communication. As a result, we involved many government institutions during this process, including the Secretariat of Strategic Affairs (SAE-PR) and the Government Secretariat (SEGOV).

We developed an intensive and direct communication process with the 390 experts from different institutions who participated in this project. They received all five partial reports, as described. A unique digital edition of Mackenzie magazine (BSBMAC, 2020) and an open-access e-book were launched (Marcial, 2020), which made it possible to expand the reach of our results.

Furthermore, from 04/06/2020–12/05/2020, the scenarios were presented to more than fifteen relevant national institutions, such as the Government Secretariat (SEGOV/PR), Secretariat of Federal Revenue of Brazil, higher education institutions (the University of Brasilia, IESB, Mackenzie Presbyterian College, in Brasilia, and FRASCE College, in Rio de Janeiro). Subsequently, the open-access e-book was virtually launched in a live event, with an audience of hundreds of participants. In addition, the launch video had more than 500 views. The final document offers readers the opportunities and threats arising from the scenarios built and the statements of key stakeholders who participated in the scenario consistency analysis.

The presentations continued during the second semester of 2020. In addition, we gave online presentations in lots of organizations, such as in the Federal District’s Planning Secretariat; the Brazilian Energy Research Company; the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa); BNDES; and the Ministry of Economy. We also participated in international foresight events and presented our work at the OECD Government Foresight Community Annual Meeting and the network of researchers participating in the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC/United Nations).

The survey aimed to evaluate the scenario process, accessing participants’ opinions concerning the value and usefulness of the scenarios built. These are shown in the following paragraphs. In this sample, 27 participants answered the evaluation questionnaire from 09/06/2021–09/18/2021.

Participants were asked to respond on a discrete five points scale ranging from totally disagree to totally agree. Among respondents, 88.9% agree or totally agree that their participation and the information received along the scenario building process were essential to understanding better the process of scenario creation. On the other hand, 77.7% agree or totally agree that their participation and the information received along the scenario building process contributed to their learning process and their organization on anticipatory strategic thinking concerning possible futures. Other 74.0% agree or totally agree that the scenarios were relevant, challenging, and plausible, and incorporated meaningful events and real challenges into the strategy formulation or decision making of their organization; 62.9% agree or totally agree that scenarios offered a background for decision-makers or the staff in charge of their organization’s strategic planning to experience new or diversified ideas.

When asked if their organization used to use the scenarios, 48.1% answered yes, and 51.9% answered no. Ten positive answers explained how scenarios were used, and some informed that the content was used for insights, planning, monitoring, and sharing within the organization. Some experts replied that they used it but could not detail the use due to confidentiality issues. Thirteen negative answers explained that non-use of the scenarios was due to political decision, the content did not reach decision-makers, other scenario studies were considered, low institutional maturity in scenario planning, unawareness about the criticality of the crises.”

5. Conclusion

Scenario building and analysis proved to be an adequate approach by providing decision-making subsidies in a turbulent environment with considerable uncertainty, even in short-term horizons. The method used to build these scenarios in a short period was thoroughly remote. We used a network of experts to produce subsidies to the decision-making process and formulate short-term strategies.

The use of mobile devices and applications demonstrated to be efficient in our research and debates. It is essential to highlight that virtual collaborative applications in real-time were essential to collect data during our study. Also, the position and statistical dispersion measures showed to be helpful and shortened the convergence of the opinion process, providing valuable information for the Control Team's decision-making process.

Notably, the remote participation of an expert group from different fields of knowledge, backgrounds, experiences, and institutions was a significant contribution. Each expert contributed to the content of scenarios built, providing all the raw information needed to write the story, while some contributed to the consistency analysis. It was a collective construction of visions of the future based on their point of view.

This research presents several contributions both for science and organizations. For science, it presents a method that can be used remotely and with quick results. It also shows how to use statistical measures of position and dispersion to facilitate and reduce the time for converging opinions. For organizations, in addition to providing a method that can be used to answer strategic questions of considerable uncertainty, it significantly reduces costs and time of building scenarios, given the possibility of doing it remotely, especially in times of crisis. It can also provide organizations with alternative, plausible, and coherent paths and views on uncontrollable variables in an environment of substantial uncertainty.

Identifying opportunities and threats resulting from the written scenarios offered a basis for strategy formulation, prioritizing necessary actions and resources, and establishing performance goals and measures for the scenario time horizon for different organizations around Brazil, especially for the government.

Another significant contribution of this method of collective construction of scenarios was the learning involved, whether from experts or Control Team members. The shared vision built is linked to personal learning. Like other disciplines, a shared vision is crucial when forming organizations and learning teams.

Identifying trends and uncertainties by a considerably heterogeneous group and their consolidation in plausible and coherent scenarios challenged much of the knowledge, values, and beliefs previously established by those involved. The crisis led to the predominance of a pessimistic view demanded a complex process to foresight the future. This method allowed a broader view of the pandemic and its future social, economic, and geopolitical impacts.

Even though the research was carried out entirely voluntarily, the project goals were achieved without funding or sponsorship. Nevertheless, the scenarios were presented to relevant national government institutions, such as the SEGOV/PR and Ministry of Economy. In addition, there is evidence that the documents were used in planning procedures for significant institutions of different sectors, such as BNDES, Embrapa, and CNI. The final document offers readers the opportunities and threats arising from the scenarios and statements of key stakeholders who participated in their consistency analysis.

Declarations of interest

None.

Footnotes

Cenários Pós-Covid 19: possíveis impactos sociais e econômicos no Brasil. Available in: https://bit.ly/2XSsj8w.

References

- Ansof, H. Igor; McDonnell, E.J. (1993). Implantando a administração estratégica. 2 ed. São Paulo: Atlas.

- Aulicino, A.; Fishman, A. (Ed.) (2020). Desenvolvimento Brasil 2035: o país que queremos. Curitiba: CRV.

- Bishop P., Hines A., Collins T. The current state of scenario development: an overview of techniques. Foresight. 2007;9(1):5–25. [Google Scholar]

- BSBMAC (2020). O Futuro pós pandemia - Grupo de Pesquisa e Estudos Prospectivos NEP-Mackenzie. Brasília: Revista BSBMAC, n. 9, ano 2, jun. Edição especial. Retrieve from: 〈chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mackenzie.br%2Ffileadmin%2FARQUIVOS%2FPublic%2F1-mackenzie%2Ffaculdades%2Fbrasilia%2F2020%2FRevistas%2FRevista_BSBMack_9_-_Especial_NEP_Mackenzie_Bras%25C3%25ADlia_-_O_Futuro_P%25C3%25B3s-Pandemia.pdf&chunk=true〉.

- Chermack T.J. Vol. 22. 2007. Assessing the quality of scenarios in scenario planning; pp. 23–35. (Futures Research Quarterly). (Winter) [Google Scholar]

- Chermack T.J., Coons L.M. Scenario planning: Pierre Wack’s hidden messages. Futures. 2015;Volume 73(Oct.):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2015.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durance P., Godet M. Scenario building: Uses and abuses. Technological Forecasting & Social Change. 2010;77(9):1488–1492. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2010.06.007. (Nov) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elsawah S., et al. Vol. 729. 2000. Scenario processes for socio-environmental systems analysis of futures: A review of recent efforts and a salient research agenda for supporting decision making. (Science of The Total Environment). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallopín G.C. (2012). Global Water Futures 2050: Five Stylized Scenarios. France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Godet, M. (1993). Manual de prospectiva estratégica: da antecipação a acção. Lisboa: Publicações Dom Quichiote.

- Godet, M. (2000). A caixa de ferramentas da prospectiva estratégica: problemas e métodos. Caderno n.º 5 do LIPS. Lisboa: CEPES. Retrived from: 〈https://bit.ly/3n2bRvW〉.

- Godet, M. (2006). Creating futures: scenario planning as a strategic management tool. 2. Ed. London: Economica.

- Grasselli G., et al. Risk Factors Associated With Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 in Intensive Care Units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(10) doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. (Oct) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen I. Scenario modelling with morphological analysis. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2018;126:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, H.; Wiener, J. (1967). The year 2000: a framework for speculation on the next thirty-three years. London: Macmillan.

- Karlsen J.E. Design and application for a replicable foresight methodology bridging quantitative and qualitative expert data. European Journal of Futures Research. 2014;2(40) doi: 10.1007/s40309-014-0040-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen J.E., Øverland E.F. Vol. 16. 2012. Promoting diversity in long term policy development: the SMARTT case of Norway; pp. 63–78. (Journal of Futures Studies). (Mach) [Google Scholar]

- Kenney H., Pelley A., B S. Stories that drive the future: how narratives can improve scenario planning. Strategy & Leadership. 2014;42(5):28–33. doi: 10.1108/SL-07-2014-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcial, E.C. (2011a). Análise estratégica: Estudos de futuro no contexto da Inteligência Competitiva. Brasília: Thesaurus.

- Marcial, E.C. (2011b). Capacitação em construção de cenários prospectivos. Brasília: Escola Nacional de Administração Pública ENAP, 2019. (229 slides). Retrieved from: 〈https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/4186?locale=en〉.

- Marcial, E.C. et al. (2017). Brasil 2035: cenários para o desenvolvimento. Brasília: Ipea/Assecor.

- Marcial, E.C., et al. (2020). Cenários Pós-Covid-19: Possíveis impactos sociais e econômicos no Brasil – Uma pesquisa do Grupo de Pesquisa e Estudos Prospectivos NEP-Mackenzie. Brasília: Mackenzie.

- Marcial, E.C.; Grumbach, R. (2010). Cenários prospectivos: como construir um futuro melhor. 5.ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV.

- Mauksch S., von der Gracht H.A., Gordon T.J. Who is an expert for foresight? A review of identification methods. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2020;154 doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119982. (May.) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcial, E.C. (2019). Curso: Construção de Cenários Prospectivos - Turma Ministério da Saúde - 1/2019. Brasília: ENAP. 22 transparências, color. Available in: https://repositorio.enap.gov.br/handle/1/4186.

- Merriam-Webster. (2020). On-line Dictionary, 2020. Retrieved from: 〈https://bit.ly/2D5B73a〉.

- National Intelligence Council. (2017). Global change: paradox of progress. NIC: Washington.

- Øverland, E.F. (2000). Norway2030. Five Scenarios about the Future of Public Sector. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen Publishing. 10.1136/bmj.331.7508.101. [DOI]

- Parandian A., Rip A. Scenarios to explore the futures of the emerging technology of organic and large area electronics. European Journal of Futures Research. 2013;1(9) doi: 10.1007/s40309-013-0009-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez R., Wilkinson A. Rethinking de 2×2 scenario method: grid or frames? Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2014;86(Jul) doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2013.10.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raven P.G., Elahi S. The new narrative: Applying narratology to the shaping of futures outputs. Futures. 2015;v. 74:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2015.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhydderch, A. (2017). Scenario Building: The 2×2 Matrix Technique. Futurible.

- Schwartz, P. (1991). The art of long view: planning for the future in an uncertain world. New York: Doubleday.

- Smart J.M., et al. The foresight guide: predicting, creating, and leading in the 21st century. Cap. 2019:2. 〈https://www.foresightguide.com〉 (Retrieved from) [Google Scholar]

- Vaitsman, H. S. (2001). Inteligência empresarial: atacando e defendendo. Rio de Janeiro: Interciência.

- van’t Klooster S.A., van Asselt M.B.A. Practicing the scenario-axes technique. Future. 2006;38:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2005.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wack P. Scenarios: uncharted waters ahead. Harvard Business Review, Setor /Oct. 1985:72–89. [Google Scholar]