Abstract

This paper uses Vietnam – where overexploitation of wildlife resources is a major threat to biodiversity conservation – as a case study to examine how government officials perceive the impacts of COVID-19 on wildlife farming, as well as the opportunities and challenges presented for sustainable wildlife management. Findings show Vietnamese government officials perceive COVID-19 to have had mixed impacts on wildlife conservation policies and practice. While the pandemic strengthened the legal framework on wildlife conservation, implementation and outcomes have been poor, as existing policies are unclear, contradictory, and poorly enforced. Our paper also shows policymakers in Vietnam are not in favor of banning wildlife trade. As our paper documents the immediate impacts of the pandemic on wildlife farming, more research is necessary to analyse longer-term impacts.

Keywords: Wildlife, COVID-19, Vietnam

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has prompted global debate within science and conservation communities around wildlife conservation and appropriate scientific responses to the pandemic, resulting in diverse human behavior and policy responses, with mixed impacts on global wildlife conservation (Bates et al., 2021). On the one hand, positive impacts for wildlife have been documented: animals have been seen roaming freely in nature by public more frequently (Koju et al., 2019, Rahman et al., 2021); there have been increases in species richness in temporarily less-disturbed habitats, higher breeding success among birds, increased sightings of urban wildlife (Zellmer et al., 2020), and a fall in road kill incidents involving animals (Manenti et al., 2020). Yet, the pandemic has also seen adverse effects on forestry economics and local livelihoods, increased deforestation rates and animal deaths due to reduced law enforcement (Bates et al., 2021, Manenti et al., 2020), more hunting of wildlife for food (Mendiratta et al., 2021), increased wildlife rescue burdens due to ecotourism bans, and reduced funding for conservation (Rahman et al., 2021, Newsome, 2020, van der Merwe et al., 2021). An increased number of armed conflicts in developing countries has resulted in significant impacts on wildlife and local people (Gaynor et al., 2020, Rondeau et al., 2020), while COVID-19 has also led to a declining numbers of national park visitors, charitable donations to support conservation, and funding for protection areas (Smith et al., 2021, Tarakini et al., 2021, Yung and Abdullah, 2021). There is evidence that many countries have weakened environmental regulations under the guise of economic recovery (Vale et al., 2021, Davenport and Friedman, 2020). Meanwhile, lockdowns have been shown to increase the prevalence of invasive alien species due to lack of funding and human resources to manage them, therefore hampering conservation activities (Manenti et al., 2020). In short, the pandemic has presented a number of cross-sectoral issues (Rondeau et al., 2020), to which both developed and developing countries have had differing responses.

Common narratives on the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic vary. Some believe the virus to have originated from a laboratory, meanwhile others believe an animal to be the source of infection, with possible pathways for this virus emerging in the human population including animals as the source of the pathogen itself, a spillover event of the virus from an animal reservoir, and zoonosis. Early human cases being associated with a live animal market in China gave momentum to the belief that COVID-19 originated from a wildlife source, though this is by no means proven, since these types of coronaviruses are common in nature and present across many species, both wild and domestic. Despite uncertainty around the source of virus, these emerging narratives have affected political and behavioral responses (Shreedhar and Mourato, 2020). The narrative that animal pathogens were transmitted to humans, for example, led to global advocacy campaigns around the banning of commercial wildlife trade (Shreedhar and Mourato, 2020, Turcios-Casco and Gatti, 2020), conservation, human health, and animal welfare standards (Aguirre et al., 2020, Roe et al., 2020). In response to speculative narratives around the virus’s origins being linked to wildlife, increasing efforts have been made to explore and understand wildlife-related food safety (Alongi, 2020, Wei, 2020, Yuan et al., 2020), with significant changes in consumer attitudes towards consuming wildlife, particularly in China (Liu et al., 2020). Meanwhile in 2020, Chinese legislature banned all terrestrial wildlife for food consumption (Huang et al., 2021), increasing hopes for China stopping wildlife trade and becoming a model for many countries to follow. Responding to the assumption that COVID-19 arose through some human-environment interaction, causing spillover of the virus from carrier animal(s) to humans (Soga et al., 2021), governments and citizens have been driven to consider how humans might interact with nature in more responsible and sustainable ways.

Concerns have been raised regarding the effectiveness of such responses, given that banning wildlife trade has the potential to undermine human rights, affect income and food security for millions of people in developing countries (Gaynor et al., 2020, Montgomery and Macdonald, 2020), as well as driving trade into unregulated black markets, and weakening incentives for local people to actively protect species and the habitats they depend on (Roe et al., 2020). Several authors found significant increases in wildlife trade seizures during COVID-19 lockdowns (Roe et al., 2020) and concluded that wildlife trade bans were insufficient (Morcatty et al., 2021). A singular focus on the wildlife trade, more importantly, overlooks one of the key drivers behind the emergence of certain infectious diseases – nature and habitat destruction, including through large-scale agriculture and livestock expansion (Roe et al., 2020).

In this wider context, this paper looks specifically at Vietnam, a country which is home to many of the world’s rare and endemic wildlife species. Overexploitation of wildlife resources is considered one of the main threats to the conservation of the nation’s biodiversity. The country is home to an illegal market for the Southeast Asian wildlife trade, involving various native species (TRAFFIC, 2008). More than 70 % of Vietnam’s wildlife farms are located in the south of the country. Export markets for Vietnamese wildlife in Italy, United Kingdom, Spain, Russia, Japan, China and the United States, provide annual revenue averaging around USD 60 million and employment for around 35,000 people (TRAFFIC, 2008). Several studies have found coronavirus present in wildlife in Vietnam (Huong et al., 2020).

For Vietnamese wildlife to be managed sustainably, policy makers need to have a clear vision and political commitment to conserving wildlife. Yet there is limited understanding around how policymakers perceive the pandemic’s impacts on wildlife, nor the various management options that have been portrayed (Hogan, 2006, McNamara et al., 2020, Morcatty et al., 2021). As the pandemic continues to unfold, understanding policymakers’ perspectives of COVID-19’s impacts, the context in which these officials are forming such perspectives, and their rationale for choosing specific impact mitigation policies, is essential if effective policy responses to the current crisis are to be designed, developed and implemented (Gaynor et al., 2020).

This paper thus takes the case study of Vietnam, in the wider context of the COVID-19 pandemic, to evaluate COVID-19’s impacts on sustainable wildlife management. By comparing government officials’ beliefs and perspectives with official statistics on wildlife farming and trade, we examine how government officials perceive the pandemic’s impacts in this arena, as well as the opportunities and challenges it presents, and seek solutions to ensure sustainable wildlife management in this context. In doing so, the paper offers insights into how developing countries’ policies and practices on supporting sustainable wildlife management can be strengthened.

2. Methods

2.1. A wide range of methods was employed in this study

Literature review – The research team firstly reviewed central and provincial government policies on wildlife preservation and wildlife farm management, gray and scientific reports on COVID-19 impacts, and opportunities and challenges for sustainable wildlife management in Vietnam. We adopted a narrative review approach, designed for topics that have been conceptualized differently and studied by different scientists from diverse disciplines (Snyder, 2019). Our review aimed for an overview of research areas on COVID-19 and how wildlife has progressed over time, as well as how this has been studied across sectors and disciplines. We used Google Scholar as a search engine, with key English words including “COVID-19”, “wildlife”, and “Vietnam”. We also used Google to search for publications and reports written in Vietnamese with Vietnamese keywords “COVID-19”, “động vật hoang dã”, “Việt Nam”. To analyze and synthesize findings, we adopted a thematic or content analysis to identify, analyze and report common themes, theoretical perspectives and common issues reported in current literature.

Key informant interviews – Semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions were then conducted with 28 key informants, including CSOs and central and provincial government officials, between April and May 2021 ( Table 1). These key informants were selected for their assigned roles as central and provincial government focal points on wildlife management, as well as their extensive work experience in the field. These key informant interviews aimed to explore government agencies’ perceptions of the effectiveness of current policies in place to address wildlife trade issues, as well as opportunities and challenges for policy implementation on the ground. Of the 25 (89.3 %) government officials participating in the key informant interviews, 16 (57.1 %) were senior managers, and 9 (32.1 %) were government focal points and specialists directly involved in formulating and implementing wildlife policies in Vietnam.

Table 1.

Participants in key informant interviews.

| Institution | Numbers of people interviewed | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Central government | 2 | 7.1 % |

| Provincial government | 23 | 82.2 % |

| Local CSO | 3 | 10.7 % |

| Total | 28 | 100 % |

An online survey was also conducted of government officials in provincial forestry offices across Vietnam to seek their perceptions on COVID-19 impacts and the effectiveness of wildlife trade policies in the country. A Google Forms link to an online survey was sent to forestry offices in all 63 provinces in Vietnam. In total, 62 (100%) officials from these forestry offices participated in the online survey.

3. Findings

3.1. Status of wildlife farms in Vietnam

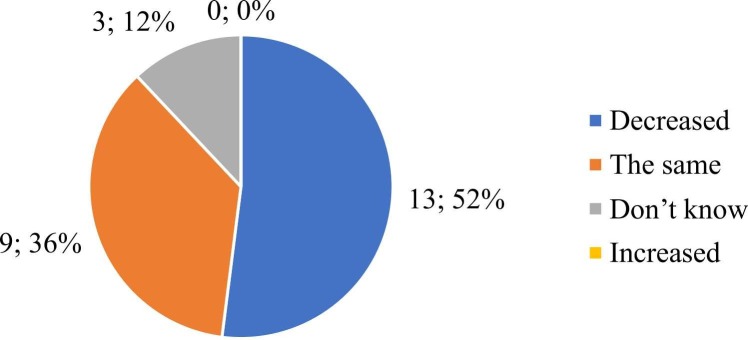

Fig. 1 highlights that 13 (52 %) government officials participating in key informant interviews believed the number of active wildlife farms to have fallen significantly in the last five years.

Fig. 1.

Key informant interviewees’ perceptions on numbers of wildlife farms.

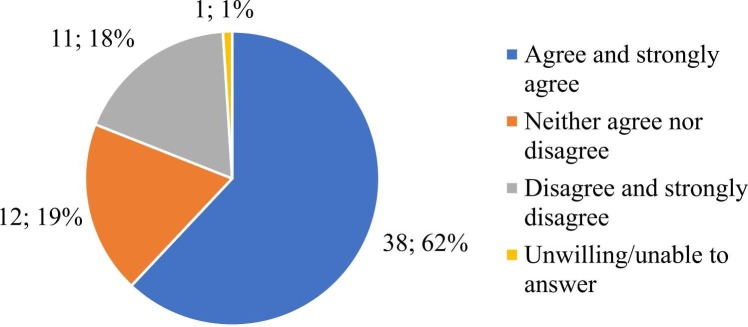

The online survey results presented similar findings, with 38 (62 %) participating forestry officials saying the number of wildlife farms in Vietnam had fallen ( Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forestry office responses to the statement: ‘The number of wildlife farms has decreased gradually over the past 5 years’.

The Vietnam Forestry Administration (2020) also reported that the number of wildlife farm licenses issued had dropped from 565 in 2019–110 in 2020. Most licenses issued were for farms that raised IIB species (forest fauna species that, although currently not threatened with extinction but may become so without strict control of exploitation and use for commercial purposes and species specified in CITES Appendix II naturally inhabiting Vietnam) ( Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of licenses issued for wildlife farm establishment in Vietnam in 2019–2020.

| 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Forest floral species threatened with extinction and banned from exploitation or use for commercial purpose and species in CITES Appendix I naturally inhabiting Vietnam (IA) | 0 | 1 |

| Forest fauna species threatened with extinction and banned from exploitation or use for commercial purpose and species in CITES Appendix I naturally inhabiting Vietnam (IB) | 40 | 1 |

| Forest flora species that, although currently not threatened with extinction but may become so without strict control of exploitation and use for commercial purposes and species specified in CITES Appendix II naturally inhabiting Vietnam (IIA) | 8 | 1 |

| Forest fauna species that, although currently not threatened with extinction but may become so without strict control of exploitation and use for commercial purposes and species specified in CITES Appendix II naturally inhabiting Vietnam (IIB) | 517 | 105 |

Source: VNFOREST (2020).

An interviewed government official from one southern province said the number of crocodile farms had declined sharply over the previous three years, with numbers falling from 200 to 300 three years ago to 130–150 in 2021. These farms, most of which had obtained licenses and ID numbers since 2007, breed crocodiles for export markets. Another government official from one of the Central Highlands provinces said the number of wildlife farms in the province had fallen from 631 in 2016, to 476 in 2021. According to many key informants, households generally breed between 5 and 10 species, the most common being the Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis), Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), hoary bamboo rat (Rhizomys pruinosus) and Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura), in response to domestic market demands. According to interviewed government officials, the declining number of wildlife farms can be explained by urbanization reducing the availability of agriculture land, industrialization, and changing policies on wildlife farming in urban areas; to establish wildlife farms, households need to secure large areas of land and ensure hygienic conditions, two factors that many households fail to meet.

While official statistics (published by MARD) and some interviewed government officials claim the number and scale of wildlife farms have recently decreased, there is scattered and limited data on the actual scale of wildlife trading, particularly since the onset of the pandemic. Data around both wildlife farming and wildlife trade is contradictory and differs across provinces. Lao Cai Department of Forestry, 2022, Yen Bai Department of Forestry, 2022 reported an increase in the numbers of farms and households involved in wildlife farming in the province, as well as the number of wildlife individuals raised in this province ( Table 3). Meanwhile, a recent report produced by the Science, Technology And Environment Committee (2020) highlights that illegal transportation of wildlife products that are listed in the CITES Appendix increased, compared with previous years. It is challenging therefore to confirm whether any reduction in wildlife farming corresponds to a reduction in the scale of wildlife trade.

Table 3.

Wildlife farms and households in Lao Cai and Yen Bai Province.

| Year | Number of individual animals raised | Number of wildlife farms | Number of households/individuals engaged in wildlife farms | Number of illegal cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lao Cai | ||||

| 2017 | 6054 | 53 | 52 | 6 |

| 2018 | 10,603 | 53 | 52 | 8 |

| 2019 | 1192 | 48 | 47 | 2 |

| 2020 | 15,146 | 56 | 55 | 1 |

| 2021 | 12,531 | 67 | 66 | 0 |

| Yen Bai | ||||

| 2017 | 325 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| 2018 | 325 | 8 | 8 | 2 |

| 2019 | 856 | 41 | 41 | 2 |

| 2020 | 3527 | 54 | 54 | 3 |

| 2021 | 3658 | 37 | 37 | 0 |

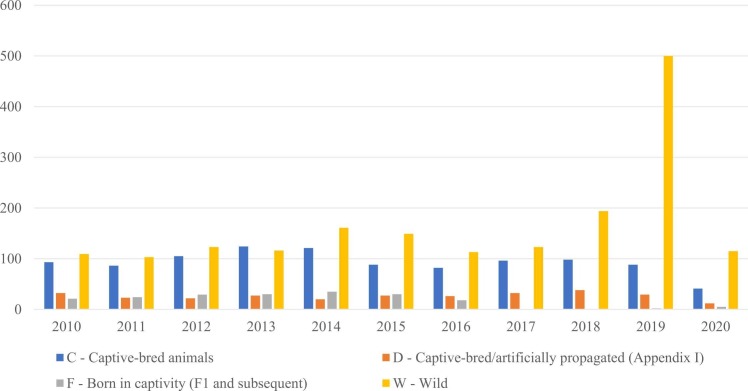

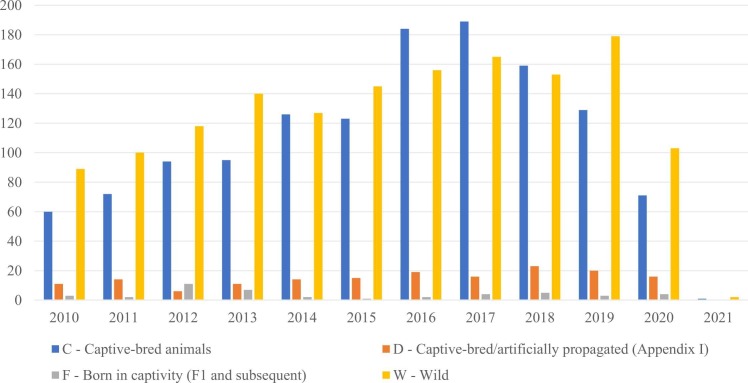

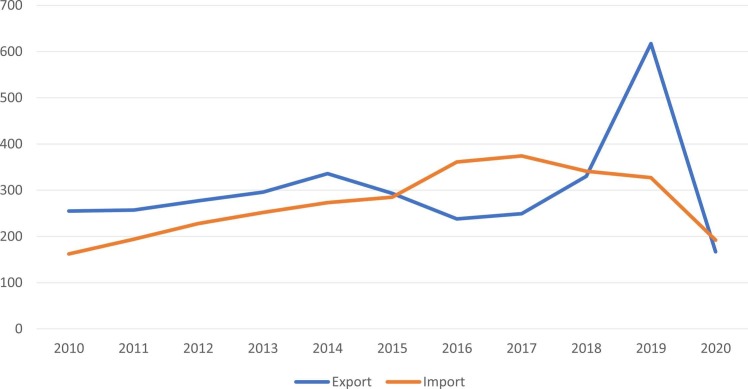

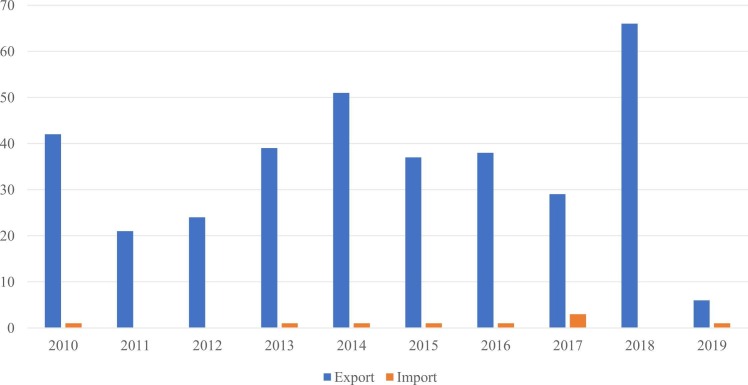

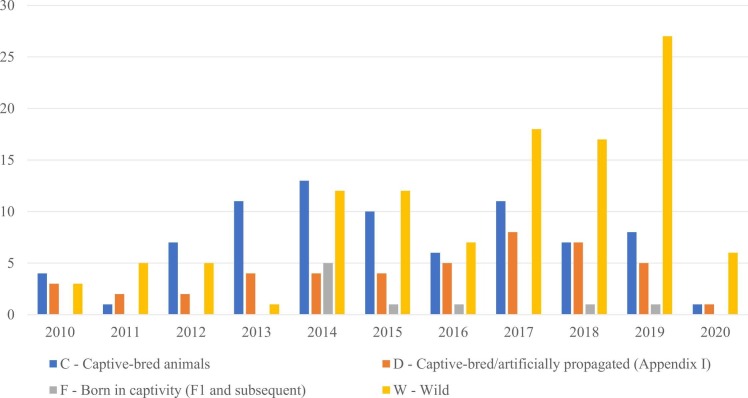

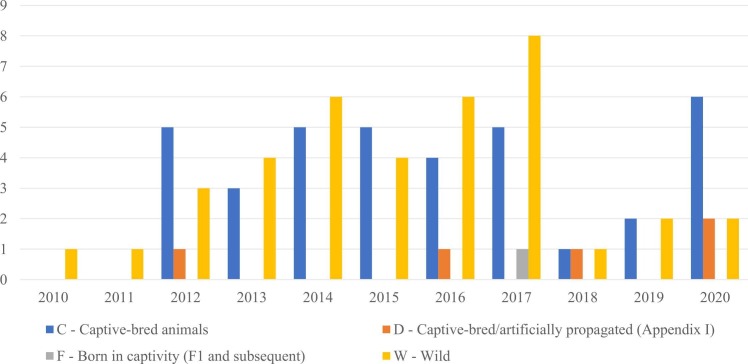

Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 show there has been an increasing number of transactions relating to wildlife originating in the wild, but there is no clear pattern showing a corresponding reduction in the number of transactions relating to wildlife kept and raised on farms. Fig. 5, Fig. 6.

Fig. 3.

Number of transactions relating to wildlife exported from Vietnam, by source.

Source: CITES (2022).

Fig. 4.

Number of transactions relating to wildlife imported to Vietnam, by source.

Source: CITES (2022).

Fig. 5.

Number of commercial transactions relating to wildlife exported from and imported to Vietnam, over time.

Source: CITES (2022).

Fig. 6.

Confiscations/seizures exported from and imported to Vietnam.

Source: CITES (2022).

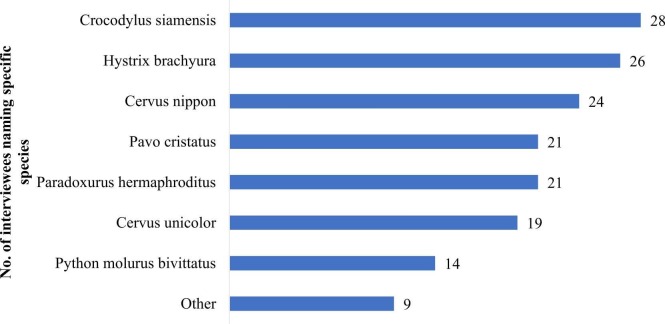

According to the Science, Technology And Environment Committee (2020), over 150 species of wildlife are being raised in tens of thousands of Vietnamese breeding facilities, including many precious and rare species, such as pythons, golden pythons, freshwater crocodiles, long-tailed monkeys, and some snake species. Annual export and import turnover is estimated at over USD 100 million. The main export items are crocodile, ostrich and python skin. For crocodiles alone, domestic enterprises export about 50,000 skins a year, to serve markets in Italy, Japan, China, Switzerland and Singapore. The Mekong Delta provinces, in particular, have a large number of farming establishments. Results of key informant interviews show the most common species being reared in Vietnam to be: Siamese crocodile (Crocodylus siamensis) with all 28 interviewees naming this species; Malayan porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) (26 interviewees naming this species); Vietnamese sika deer (Cervus nippon) (24); Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus) (21); Indian peafowl (Pavo cristatus) (21); sambar deer (Cervus unicolor) (19); and Burmese python (Python molurus bivittatus) (14) ( Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Most commonly-farmed wildlife species.

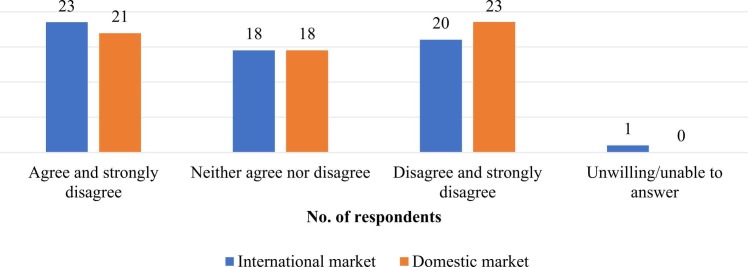

A government official from one Central Highlands province attested that wildlife products vary from province to province, depending on customer demands. For example, domestic markets prefer common species such as Hystrix brachyura, Cervus unicolor, Asiatic softshell turtle (Amyda cartilaginea) and Paradoxurus hermaphroditus, while international markets require Group IIB species (species for limited exploitation under Decree No. 6 of 2019 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a)), such as: oriental rat snake (Ptyas mucosus) or Indian cobra (Naja naja), which are mostly exported to China. Results of the online survey show polarized opinions among provincial forestry officials, when it comes to changes in domestic and international market demand for wildlife species ( Fig. 8); roughly a third of officials believed international and national demand had fallen over time, while another third said it had increased.

Fig. 8.

Forestry office perceptions of whether international and national market demand for wildlife had decreased over time.

Despite differing perceptions around decreasing international and national market demand among forestry officials, data from CITES (2022) shows a decline in the number of traded wildlife exported from Vietnam to China beginning in 2019 following the pandemic ( Fig. 9). A key informant from one southern province highlighted that lower market demand from China had reduced the price of wildlife animals by 50 %, and numerous policymakers felt that many Vietnamese wildlife farms had been forced to shut down or sell their businesses to other owners as a consequence of this.

Fig. 9.

Number of wildlife trade cases, exported from Vietnam to China, by source.

However, the picture is much more nuanced as the data is conflicting. Responses to the survey are undecided; the CITES data is also conflicting. There is no clear pattern here around increases or decreases, just changes between the source country and origin (wild/farmed). While these government officials believed overall decline in market demand was what had driven the reduction in wildlife farms and trading activities, CITES data (2022) reveals that transactions relating to wildlife originating in the wild increased dramatically (Fig. 9). Fig. 10 meanwhile shows that the number of transactions for farm-originating wildlife exported from China to Vietnam, also increased. Twenty-eight government officials participating in the survey agreed or strongly agreed that domestic demand for wildlife was indeed increasing, mostly for wildlife imported from China.

Fig. 10.

Number of wildlife trade cases, imported from China to Vietnam, by source.

3.2. COVID-19 impacts

Of the forestry officials that responded to the survey, 33 (53 %) agreed or strongly agreed that COVID-19 had a negative impact on wildlife farms, while 27 (43 %) felt it had no effect. A government officer interviewed from one southern province said it was not the pandemic that had caused economic losses for wildlife farm owners. Another government official from one province in the Mekong Delta region said the decline in wildlife trade occurred before COVID-19, with falling market prices for crocodiles and porcupines causing the number of farms to fall from 1200 in 2016–800, and that more recently, the number of farms had remained relatively stable.

3.2.1. Policy impacts

Recognizing the importance of wildlife biodiversity, the Vietnamese government has recently issued a series of regulations on wildlife conservation ( Table 4).

Table 4.

Policies relevant to wildlife conservation.

| Year | Policy |

|---|---|

| 2019 | Circular No. 29/2019/TT-BNNPTNT dated 31December (2019) from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, which regulates the nurturing and preservation of wildlife species |

| 2019 | Decree No. 35/2019/ND-CP dated 25 April 2019, on sanctions for administrative violations in the forestry sector |

| 2019 | Decree No. 06/2019/ND-CP dated 22 January 2019, on the management of endangered, precious and rare forest flora and fauna |

| 2017 | Forestry Law 2017 on biodiversity conservation |

| 2013 | Decree No. 157/2013/ND-CP, which stipulates levels of administrative sanctions for forest management, development and protection violations, and management of forest products (including wildlife) |

| 2012 | Circular No. 47/2012/TT-BNNPTNT, which oversees the management, exploitation, and nurturing of 160 species of common forest animals that can be exploited and bred for commercial purposes |

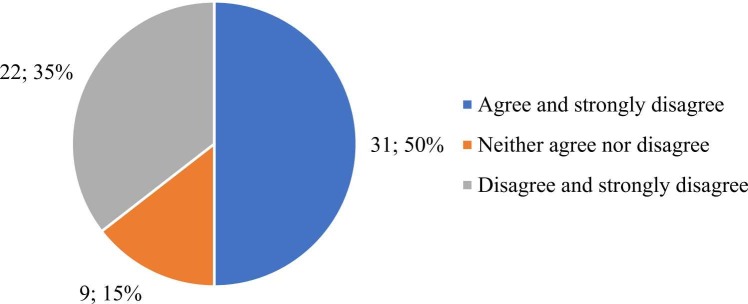

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted further changes, with the majority of forestry official survey respondents saying the government had expanded the legal framework on wildlife management since the pandemic ( Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Forestry office responses to the statement ‘There are more policies on wildlife management operations after COVID-19 than there were before it’.

As part of its response to COVID-19, the government issued Directive No. 29/CT-TTg (Prime Minister of Vietnam, 2020) to suspend imports of live wild animals, eggs and larvae, as well as wild animal parts and derivative products (with some exceptions for aquatic species in food production, breeding and medicine production), and shut down markets/outlets selling illegal wildlife products. It also mandated that no citizens, including those working in government, can illegally hunt, trade, traffic, kill, possess, consume, or advertise protected wildlife or illegal wildlife products. The directive requires cross-sectoral policies and collaboration in addressing the wildlife trade, including law enforcement, awareness raising and strengthened monitoring and evaluation.

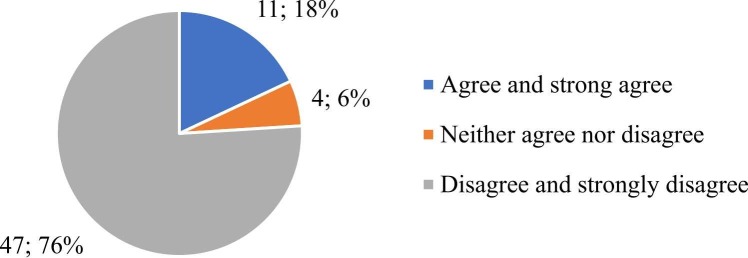

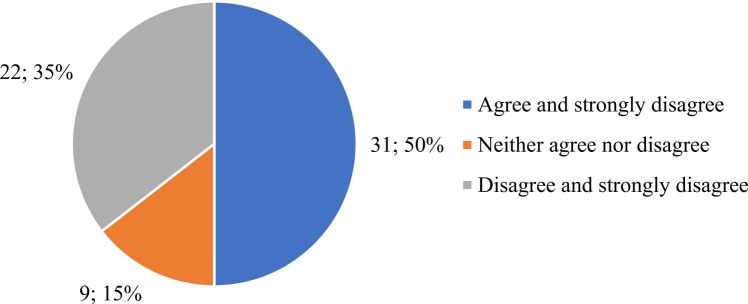

Although international organizations urged the closure of wildlife farms, Directive No. 29/CT-TTg (Prime Minister of Vietnam, 2020) clearly does not share the same objective; instead, it aims to limit illegal wildlife trading while ensuring sustainable wildlife management. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development is instructed to work with relevant agencies to monitor captive-bred wildlife, for example, ensuring wildlife is legally sourced and that a minimum standard of hygiene is met. A database of captive-bred farms/facilities is to be established. The Ministry of Health will work to ensure that wild-sourced medicinal ingredients are legally acquired, while the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment will review wildlife regulations, and suggest amendments to strengthen policies. People’s committees at the city and provincial levels will instruct local agencies to implement solutions to counter wildlife trafficking and strictly monitor captive-breeding facilities, which must pledge not to trade, consume, display, or advertise illegally-sourced wildlife. The majority (76 %) of the provincial forestry office representatives responding to the online survey disagreed or strongly disagreed with closing wildlife farms being a solution to COVID-19 and sustainable wildlife management ( Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Forestry office responses to the question ‘Do you agree that the solution to COVID-19 and sustainable wildlife management is to close wildlife farms?’.

3.2.2. Increased burden from wildlife rescue

Of the 62 forestry office representatives participating in the online survey, 46 (74 %) had expertize specific to forestry science, while only one had a background specific to wildlife management. In terms of experience with wildlife management, 54 (87 %) respondents had between 2 and 15 years’ experience, eight had more than 15 years, and four had less than two years. Most of the interviewed government officials said they had to carry out multiple tasks, and that wildlife farming and wildlife conservation were only part of their job. Only four (16 %) interviewees said they were provincial government focal points for monitoring and supervising wildlife farms, while 14 (56 %) worked in wildlife rescue teams and seven (28 %) in wildlife inspection units. Most interviewed government officials said that since COVID-19, many farm owners have faced bankruptcy and had to hand over their animals to rangers, but rangers lack adequate facilities and capacity to receive animals. When asked whether Vietnam has insufficient numbers of rescue centers and resources necessary for them to function effectively, an overwhelming 22 (88 %) interviewees agreed or strongly agreed.

A government official from one southern province elaborated further, saying: ‘Rescue centers only accept rare species, so we don’t know what to do. In the past, if we had to rescue any wild animals, we could send them to other provinces, but now all rescue centers are full and other provinces don’t accept our animals anymore. The costs required for maintaining rescue centers are high and there is no funding for this.’ Another government official from one Central Highlands province said: ‘Releasing wild animals kept by local people or reintroducing them to forests is a challenge. As they are treated as state and public property, there is a lot of paperwork and high transaction costs involved.’ One forestry official said: ‘We can die rescuing animals, and animals can die because the paperwork is complex, unclear and time consuming. In many cases, it has taken us three years to deal with the necessary paperwork, and when decisions are finally made, the animals have died already. If local people return animals to us, where should we transfer them? We ask provincial heads, but they can’t answer us. They just tell us to wait until the next public committee meeting, but in the meantime, where should we put them? We’re scared.’.

3.2.3. Economic impacts – decreasing number of wildlife farms since COVID-19

Regarding economic impacts, 31 (50 %) of the forestry officials surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that economic contributions to provincial GDP from wildlife farming and trade had decreased since COVID-19, while nine disagreed or strongly disagreed. Twenty-nine (47 %) participants in the online survey agreed or strongly agreed that since COVID-19, domestic and overseas market demand for domestically-produced wildlife and derivative products had decreased dramatically ( Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Forestry officers’ responses to the statement ‘Since COVID-19, domestic and overseas market demand for domestically-produced wildlife and derivative products have decreased dramatically, thus reducing wildlife farming and trade’.

Thirty-seven (60 %) forestry office respondents in the online survey and ten (36 %) key informant interviewees (mostly from Central Highlands and southern provinces) agreed or strongly agreed that wildlife farms had fallen in number since COVID-19. Twenty-six (42 %) online survey respondents believed that many wildlife farms had gone bankrupt since COVID-19. One forest ranger from a southern province said that, since the pandemic, more than 28 wildlife farms had closed down in his province, due to a combination of falling domestic market demand and overseas bans on imported wildlife products. Another interviewed government official from one southern province indicated that, since the onset of COVID-19, many farms in his area had been unable to export and import wildlife products to and from Cambodia. Online survey respondents felt COVID-19 had impacted large and small wildlife farms differently, however; 49 (79 %) respondents felt the pandemic had a major impact on export revenues for large wildlife farms, while just 30 respondents felt COVID-19 had adverse impacts on small wildlife farms.

With the vast majority (58 out of 62; 94 %) of online survey respondents attesting that wildlife farms and trade were major income sources for local people in their respective provinces, COVID-19 has had knock-on implications for local livelihoods. A government official from one Central Highlands province said that, since COVID-19, delays in exports to China and low market prices had affected wildlife farmers in the area he manages, however, he noted that this impact differed depending on the wildlife product; while farms breeding snakes and porcupines had been forced to sell up and switch to other livelihood sources, the market for deer – bred by traditional villages since 1975 – remained stable and had not been impacted by COVID-19.

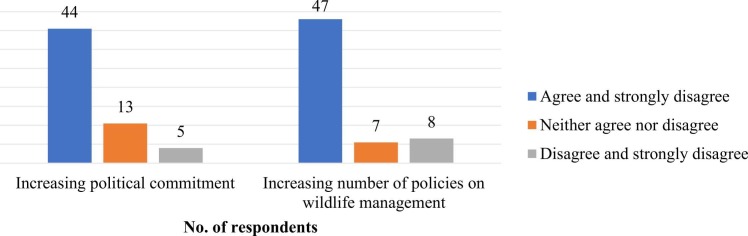

3.3. Opportunities for wildlife management in Vietnam

Survey respondents and key informant interviewees alike demonstrated high hopes for sustainable wildlife management, with 44 (71 %) forestry office respondents to the online survey attesting that the government had significantly increased its attention to wildlife management and relating policies ( Fig. 14).

Fig. 14.

Forestry officers’ responses to the statements ‘Wildlife management and conservation has received increasing attention from government agencies’, and ‘There are increasing numbers of policies supporting wildlife management and conservation’.

As implementation of wildlife management policies like Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) requires expertize in environmental conservation and veterinary science, forestry offices must collaborate with veterinary departments. In some areas, including Ho Chi Minh City, forestry offices have recruited veterinarians as full-time staff members so they can manage and inspect wildlife farms more effectively.

In addition to policy improvements, government agencies are now applying digital technology in an attempt to improve the management of wildlife farms. One example of this is Dong Nai Provincial Forest Protection Department (FPD), which has developed a digital database combined with remote sensing to monitor wildlife farms and provide early warnings in detecting disease transmissions. Forest protection officers were using a mobile application during farm inspections to complete and upload any necessary information to the server for real-time monitoring, and increasingly using Flycam stabilizers and drones to monitor forest resources and detect signs of illegal logging and trading. An official confirmed the Department’s plans to develop an online disease and treatment database, based on scientific and Indigenous knowledge, so that wildlife farm owners can search for information and learn for themselves. According to this official, local people have traditional knowledge on treatments which they feel is important to preserve. The official also said many endangered species cannot be reared or bred in government facilities, but are sometimes bred and reared successfully on wildlife farms.

However, not all agencies and provincial governments have the resources or technical capacity necessary to develop and apply digital technology for the mapping and monitoring of household or village wildlife farms. Just 20 (32 %) online survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the application of digital monitoring technologies presented an opportunity to sustainably manage wildlife in Vietnam; another 28 (45 %) disagreed, and 12 (19 %) neither agreed nor disagreed. Offices using digital technology often had higher technical capacity, as well as funding from central or provincial governments or from international projects.

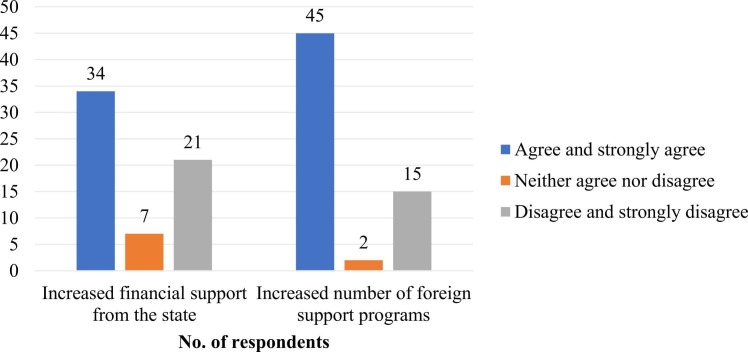

Most online survey respondents felt that foreign support programs and state funding for wildlife management had increased over time ( Fig. 15). Most forestry office respondents (45; 73 %) acknowledged that this had resulted in increased local awareness of wildlife conservation. Most key informants interviewed said the number of households returning wildlife they had kept illegally on farms to forest rangers had increased over time, as local people were more aware of government policies thanks to intensive awareness-raising campaigns run by international organizations. Wildlife farm owners in some provinces, including Dong Nai, are trained on zoonotic diseases and proper veterinary requirements, so as to run farms more sustainably. International organizations have also helped local governments to detect disease risks for wildlife farms, including reptile farms in Dong Nai, so government agencies can take swift action. Of the 62 online survey respondents, 34 (55 %) said that not only were more policies being implemented, wildlife monitoring, supervision and law enforcement were also becoming more effective.

Fig. 15.

Forestry officers’ perceptions on whether state funding and foreign support programs for wildlife management had increased.

3.4. Challenges for wildlife management in Vietnam

3.4.1. Unclear legal frameworks

One government official commented that despite the numerous wildlife conservation policies now in place, they were yet to be effective and had often been developed based on international standards without consideration for local context.

Having been implemented for nearly two years, Decree No. 06/2019/ND-CP (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) has contributed significantly to improving efficient management, conservation, and development of rare, endangered and precious species. Meanwhile Decree No. 06/2019/ND-CP (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) has cut 16 administrative procedures, creating favorable conditions for organizations and individuals to rear, grow, process, trade, import and export specimens of wild flora and fauna in accordance with the law. However, the many new points specified in the Decree have imposed certain implementation constraints. Various questions have been raised on areas for clarification, and the Decree needs to be further amended and supplemented to be practical. For example, scientific names of many species in the list of endangered, precious and rare forest plants and animals are inconsistent with the list of species prioritized for protection; various terms lack clear definition, leading to omissions in the list of wild flora and fauna species requiring management; and regulations on handling specimens of foreign origin are inconsistent with CITES, regulations on assigning codes, storage regulations, etc. These shortcomings and limitations have caused difficulties, not only for enterprises and individuals, but also for state management agencies involved in this field.

Although Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) is the backbone of wildlife trade management policy, more than 56 respondents to the online survey agreed or strongly agreed that Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) faces many implementation challenges. A particular challenge, according to 47 (76 %) forestry office respondents in the online survey, was implementing Article 11 of Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a), which stipulates that enterprises and individuals must ensure legal origin of farmed animals in accordance with the law. Most (53) agreed or strongly agreed that although Article 11 stipulates that enterprises and individuals breeding common forest animals must ensure human safety, there are no specific instructions on how to do so; while 54 (87 %) respondents said there were no specific instructions on how to ensure the ‘favorable environmental conditions’ required by Article 11. An equal number agreed or strongly agreed that despite Article 11 stipulating that enterprises and individuals breeding common forest animals must satisfy veterinary requirements, those requirements were neither known nor understood by local people, forestry officials or veterinarians.

Meanwhile, 31 (50 %) online survey respondents agreed or strongly agreed that it was unclear how to implement provisions under Article 14 of Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a), which requires farms to rear and plant in accordance with the growth characteristics of the specific species, ensure safety for humans, animals and plants, and environmental sanitation to prevent epidemics, but which lacks any definitions for such standards or conditions. Central government officials interviewed in Ho Chi Minh City said that while Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) stipulates that only licensed farms may breed wildlife species, the city’s Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens is currently breeding and rearing large numbers of endangered species, including sun bear (Ursus malayanus) and Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) without a license. Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) decentralizes power to sub-national governments so they can issue licenses for Group II1 species, while Group I2 species require approval from CITES. According to interviewed officials from Ho Chi Minh City, many wildlife farms had yet to be licensed due to the complex paperwork involved.

Both interviewed government officers from Ho Chi Minh City highlighted an urgent need to provide clear regulations and guidance on environmental and veterinary standards and ensuring human safety. For example, Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) requires wildlife farm owners to comply with regulations on cage conditions and standards, but these are neither specified nor defined for species other than crocodiles, bears and cobras, in any current policies.

According to the forest ranger informants from southern provinces, it is very difficult to enforce environmental and veterinary requirements because policies provide no details of what requirements they have to follow. They had asked veterinarians for guidance and expertize, but they too were uncertain. One forest ranger said current policies can be unrealistic, citing Decree 40 (Government of Vietnam, 2019c) which stipulates that if a farm rears more than 50 individuals it is required to submit an environmental impact assessment. However, the environmental impact of 50 large animals like tigers or elephants is very different from that of 50 small animals like rats or snakes, so this provision can result in unnecessary paperwork for both government officers and local people. According to several interviewed government officials, local people are unhappy with this administrative burden and have tense relations with rangers. Unclear definitions or distinctions between forest animals and wildlife cause further challenges for law enforcement.

One interviewed government official said: ‘It difficult enough for us to manage live animals; what to do with dead wild animals is another issue. When a tiger, which is classed as an endangered species dies, a household might report it to us and ask what they should do. But because of policy inconsistencies we don’t actually know. Circular No. 29/2019/TT-BNNPTNT (MARD, 2019) says we can’t burn animals and have to transfer them to museums or research institutes. But we don’t have the facilities or resources to do so. We’ve tried contacting museums and research institutes, but they don’t accept our requests. Meanwhile, farm owners insist that as the animals belong to them, they should be able to burn them without asking the government for permission. We have sent four requests for help and guidance to the central and provincial government, but haven’t heard back from anyone.’.

Another provincial official said: ‘The paperwork for implementing Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) does not differentiate between species. Whether we want to rescue a tiger or a rat, the paperwork required is still the same. The forms are also difficult to fill in. Even rangers struggle, so how can you expect less educated farm owners to fill them out? We’re waiting for central or provincial government guidance on who will pay for and take care of rescued animals. There are no funds from the state budget, so there’s no rescue center, and we can’t return animals to the wild because they might be carrying diseases.’.

The lack of consistency and coordination across policies frustrates local people. One government official said: ‘When Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) was issued to replace Decree 32 (Government of Vietnam, 2006), we didn’t know how to solve problems on the ground. Many farm owners were already registered in the system under Decree 32, but Decree 06 required them to register again based on different categorizations. Local people felt frustrated with the paperwork, complaining “the government already legalized us, so how come we’ve now become illegal and unregistered?”’ Although interviewed government officials said support for sustainable wildlife pathways in Vietnam had increased from both state and foreign programs, 49 (79 %) forestry office respondents to the online survey felt that differing perspectives on wildlife conservation, between government agencies and conservation organizations, had created confusion and challenges in implementing wildlife conservation. Likewise, 36 (58 %) online survey respondents felt policy implementation coordination between the CITES office and FPDs was ineffective. And while Decree 06 (Government of Vietnam, 2019a) requires FPDs and veterinarian departments to collaborate closely on wildlife management, just nine (15 %) of the 62 survey respondents felt this actually happened.

3.4.2. Weak monitoring and evaluation and law enforcement

Despite many policies being – at least to an extent – implemented effectively, a key challenge for sustainable wildlife management is weak monitoring and evaluation. Despite improvements in law enforcement, Table 5 shows that the majority (56; 90 %) of forestry office respondents felt that wildlife hunting persisted in their regions; while 54 said wildlife trading also persisted. The majority (46; 74 %) also felt sanctions and mechanisms to enforce laws and deal with violations were infrequent and ineffective, and 54 (87 %) said tracking and detecting illegal wildlife trading was difficult in their regions.

Table 5.

Forestry office views on challenges for sustainable wildlife management in Vietnam.

| Stances | Agree or strongly agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree or strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wildlife hunting continues in my area | 56 | 2 | 4 |

| Wildlife trading continues in my area | 54 | 6 | 2 |

| Sanctions and mechanisms to enforce laws and deal with violations are infrequent and not effective enough | 46 | 10 | 6 |

According to interviewees from the Ho Chi Minh City FPD, illegal trading still occurred but it was difficult to identify or detect perpetrators. One government official said: ‘Many families breed wildlife species illegally but we don’t know about it. It’s only when CSOs spot them that we can make arrests.’ Another government official highlighted that current policies were problematic because they only required certificates for province-to-province trade; as there were no requirements for trading within these provinces, people could easily conduct illicit trading activities.

3.4.3. Weak capacity

According to most interviewed government officials, both government agencies and local people lack capacity and knowledge when it comes to environmental and zoonotic conditions. Forest ranger studies focus on trees, but not animals. And although wildlife farm management legislation in Vietnam relies on a registration system, whereby the government requires farm owners to register and report on their status, 42 (73 %) forestry office respondents said many small wildlife farming enterprises and farm owners had numerous difficulties registering and completing the necessary paperwork and documentation. According to interviewed officials, both large commercial companies and household enterprises engage in wildlife farming; however, while large companies have sufficient funding and dedicated trained staff, households lack financial capital, technical capacity and understanding. These interviewees highlighted that the most challenging task for households was ensuring they had proper record-keeping systems. Another issue was the limited numbers of rangers responsible for managing large administrative areas, making control very difficult. Most rangers felt they lacked the knowledge necessary for wildlife management and conservation, since their backgrounds were in forestry.

4. Discussion

A shock like the COVID-19 pandemic can catalyze processes of institutional or policy change (Capoccia and Kelemen, 2007, Hogan and Doyle, 2007). Our paper set out to discuss how government agencies in Vietnam perceive the impacts of COVID-19, as well as the opportunities and challenges the pandemic may have presented for sustainable wildlife management. In doing so, the paper reveals a number of disconnects between perceptions and realities, policy and practice, and different governance levels. Our paper supports other studies, which find that links between COVID-19, rural livelihoods, and wildlife are likely to be more complex, nuanced, and far-reaching than is represented both in the literature to date (McNamara et al., 2020) and in the current perceptions of policymakers taking part in this study.

4.1. Disconnects between stakeholder perceptions and on-the-ground realities

Our paper shows that while some policymakers claim the decline in wildlife farms is partly due to COVID-19, others disagree that is the case. These differing views hint that, in reality, the impact of COVID-19 has differed from place to place, and thus a uniform policy response to COVID-19 is likely to be ineffective as it does not consider the diverse social and political contexts. The current wildlife monitoring and evaluation system in Vietnam, which primarily reports on the number of wildlife farms, does not give reliable and accurate data regarding the scope or scale of the wildlife trade as a whole, nor the full scale of animal populations being kept and raised in these wildlife farms. More useful data would be absolute numbers of wildlife bred, caught and traded, rather than farms as an indicator; or a better evidential set showing that the numbers of animals in farms has not substantially changed, so that the presumption of less farms equals less traded wildlife can be confirmed. That some policymakers saw a decline in farm numbers in their provinces before the pandemic also highlights a need for research to comprehend the underlying factors driving this change; as well as whether this decline has actually led to a decline in the wildlife trade as a whole. More rigorous assessment of the actual impacts of COVID-19 on wildlife farms and local livelihoods in Vietnam is essential, if we are to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the full impacts of the pandemic.

The wildlife trade in Vietnam is driven by both domestic and international market demand, particularly China (Huang et al., 2021). The previous section shows a decline in the number of traded cases exported from Vietnam to China after COVID-19, but an increase in the number of cases from China to Vietnam; further study is required to understand what is behind this pattern. As legal and policy coordination between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors remain limited in scope and effectiveness (Jiao et al., 2021), and large numbers of people still want to consume wild animals after COVID-19 (Si et al., 2021), demand still drives the production of wildlife products in many countries, including Vietnam. A political committee and policy shift that employs a holistic view to ensuring wildlife management, is now needed.

While the risk of zoonotic diseases has been linked to COVID-19 by numerous scientific papers and narratives portrayed by media and environmental organizations, our paper shows that Vietnamese policymakers have not treated this risk as a reason to protect wildlife; indeed, they have requested further evidence to consolidate their policy responses. Zoonotic diseases could indeed be circumstantial; there is a lack of direct evidence to confirm its emergence pathways, as well as a need to better understand the role of domesticated animals and wildlife under direct domestic management as a reservoir and source of zoonosis and novel pathogens (Richard and Hernan, 2022). The initial reaction to COVID-19 of many actors in the global conservation community – to call for a ban on all wildlife trade – is understandable; however it remains unknown if this measure would have a substantial impact on preventing future epidemics, or would have averted any of the current risks (Richard and Hernan, 2022).

4.2. Disconnects between policies and practices

Following the COVID-19 outbreak, global public opinion has grown against unsustainable and illegal utilization of wildlife, which in turn has driven demand and pressure for policy change (D’Cruze et al., 2020, Xu et al., 2021). In response, the Government of Vietnam has developed and implemented several policies, however, as most policymakers highlight in our study, implementation has been hindered by limited human resources, inconsistent policy guidelines, insufficient administrative sanctions, weak coordination, and insufficient support systems to enforce laws effectively, weakening the impact and effectiveness of these policies. Without addressing underlying factors behind such institutional challenges and ensuring the enabling conditions are in place, it is unlikely that any policy responses relating to wildlife conservation or COVID-19 will be effective. It also suggests further examination is needed around the feasibility and effectiveness of a wildlife trade ban in Vietnam, as articulated by international communities; given the lack of institutional readiness and the ineffectiveness of similar bans in other countries (Roe et al., 2020, Cheung et al., 2021). Even China, which implemented a wildlife trade ban after the COVID-19 pandemic, still faces problems operating wildlife trade regulations due to outdated lists on protected species, insufficient cross-sector collaboration, weak law enforcement on the farming and trading of species, and a lack of quarantine standards for wildlife not covered by the ban (Xiao et al., 2021). Likewise, attempting to address COVID-19 and unsustainable wildlife farming simply by closing wildlife farms down could lead to a shift from legal to illegal trade. The root causes of some emergent infectious diseases could be associated with habitat destruction, agriculturalization, and animal-based industry; some epidemiological pathways are well understood and documented. However, this process is complex, and not generalizable for all infections and diseases new or old. More research needs to be carried out to increase our understanding of the linkages between wildlife farms and human diseases. Conservation-inspired responses to COVID-19 need to be evidence-based, address habitat destruction, respect rights, ensure local participation in decision making (Roe et al., 2020), and strengthen legal frameworks and institutional support in most developing countries, including Vietnam (Gaynor et al., 2020).

While whether – and to what extent – COVID-19 has impacted wildlife farms and the wildlife trade stills needs further on-the-ground evidence, the pandemic has shone a national and international spotlight on serious deficiencies in the current legal framework that protects wild animal health, and consequently human health. There is limited guidance on the farming of wild species, and a lack of appropriate safeguards to ensure animal health and welfare while protecting public health (Orenstein, 2021; Whitfort, 2021); this is well demonstrated in the case of Vietnam. While the pandemic brought special attention to the health links associated with animal-human interactions, challenges in understanding, implementing, and monitoring environmental and veterinary standards, highlighted by government officials in our survey, pose a threat to both human and animal safety. Strengthening public health and veterinary monitoring of infection is essential, and additional funding and research are needed to complete the knowledge gap on COVID-19’s impacts around human and environmental health (Rutz et al., 2020). Identifying high-risk practices for both legal and illegal wildlife trade, and improving sanitary and animal welfare conditions along supply chains, is likely to reduce the likelihood of spillover events. However, the wildlife trade must be considered alongside all other potential pathways and drivers of disease emergence proportionally, in a balanced intersectoral and transdisciplinary manner, informed by evidence-based disease risk analysis (Richard and Hernan, 2022). Forestry officials in Vietnam also highlight a need for further research on safety, environmental, and veterinary requirements, to ensure both human and animal safety in Vietnam. In addition to policy revision, updating protected species lists, and changing consumer behaviors, sufficient funding to support conservation is required to address the illegal wildlife trade (Xiao et al., 2021, Rahman et al., 2021).

4.3. Disconnects between actors at different governance levels

When COVID-19 emerged, one of the immediate responses globally was to call for a ban on wildlife trade for the sake of human health and conservation, and for animal welfare standards (Roe et al., 2020). In Vietnam, discussions around a countrywide ban of the wildlife trade were articulated in the media by a wide range of stakeholders (TRAFFIC, 2020, VnExpress International, 2020, WCS, 2020) reflecting this global debate (D’Cruze et al., 2020). However, interviewed government officials disagreed and were keen to seek alternatives to eliminating wildlife trading, while concentrating instead on ensuring sustainable wildlife farm management. The mixed views of policymakers in Vietnam on COVID-19’s impacts on wildlife and their disagreement around the ban, reveal a disconnect between external agents (e.g., international conservationists) and people on the ground (e.g., provincial government officials) when it comes to natural resources and their management. Narratives and proposals generated at a global level are often based upon perceptions alone; as provincial stakeholders’ experiences do not marry with international concerns around zoonosis or disease spread, our survey results are somewhat contradictory to the narratives expressed by government and conservation organizations. This mirrors the globally differing perspectives around wildlife conservation between conservationists and politicians, and even among conservationists themselves (Bennett et al., 2021), highlighting a need for a more evidence-based narrative at all levels.

5. Conclusions

Our paper shows that Vietnamese government agency officials perceive COVID-19 to have had mixed impacts on wildlife conservation policies and economies. Our findings show an increasing number of policies have been put in place to strengthen sustainable wildlife management, while local awareness of wildlife conservation has also increased through government and foreign programs. Government officers also perceive law enforcement, coupled with the monitoring and supervision of wildlife farms, to be more effective. While COVID-19 has expanded the legal framework for Vietnam’s existing wildlife conservation policies, its implementation and outcomes have been poor. The legal framework remains weak and contradictory, and despite the overall perception among government officials that law enforcement and wildlife monitoring have improved, in practice there is still much room for improvement. An ongoing challenge is that of limited knowledge and capacity among government agencies and local people, when it comes to environmental and zoonotic conditions. Lack of available data on the impacts of COVID-19 on local livelihoods in Vietnam also makes it a challenge to gain a comprehensive understanding of the full impacts of the pandemic. Our paper highlights gaps between policy and practice, as well as perceptions and reality when it comes to COVID-19 impacts, flagging the need for more research on the interactions between wildlife-human health, and holistic wildlife management approaches that matches country and local contexts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dang Hai Phuong: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Nguyen Thi Kieu Nuong: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Hoang Tuan Long: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Tran Ngoc My Hoa: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Nguyen Thi Thuy Anh: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Nguyen Thi Van Anh: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Isabela Valencia: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CGIAR-COVID-19 Hub, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA) and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) for supporting this study. We would like to express our special thanks to the reviewer who gave us extremely useful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Species of forest plants and animals that are not yet threatened with extinction but are at risk of being threatened if they are not properly managed and restricted from exploitation and use for commercial purposes, and species listed in CITES Appendix II, that are naturally distributed in Vietnam.

Species of forest plants and animals that are threatened with extinction are strictly prohibited from exploitation and use for commercial purposes, and the species listed in CITES Appendix I, that are naturally distributed in Vietnam.

References

- Aguirre A.A., Catherina R., Frye H., Shelley L. Illicit wildlife trade, wet markets, and COVID‐19: preventing future pandemics. World Med. Health Policy. 2020;12:256–265. doi: 10.1002/wmh3.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi D.M. Global significance of mangrove blue carbon in climate change mitigation. Science. 2020;2(3):67. doi: 10.3390/sci2030067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates A.E., Primack R.B., PAN-Environment Working Group, Duarte C.M. Global COVID-19 lockdown highlights humans as both threats and custodians of the environment. Biol. Conserv. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E.L., Underwood F.M., Milner-Gulland E.J. To trade or not to trade? Using Bayesian belief networks to assess how to manage commercial wildlife trade in a complex world. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021;9:123. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.587896. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capoccia G., Kelemen R.D. The study of critical junctures: theory, narrative, and counterfactuals in historical institutionalism. World Polit. 2007;59:341–369. doi: 10.1017/S0043887100020852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung H., Mazerolle L., Possingham H.P., Biggs D. China’s legalization of domestic rhino horn trade: traditional Chinese medicine practitioner perspectives and the likelihood of prescription. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021;9:27. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.607660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CITES. 2022. CITES Trade database. Available at: https://trade.cites.org/.

- D’Cruze N., Green J., Elwin A., Schmidt-Burbach J. Trading tactics: time to rethink the global trade in wildlife. Animals. 2020;10:2456. doi: 10.3390/ani10122456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, C. , Friedman, L. , 2020. Trump, Citing Pandemic, Moves to Weaken Two Key Environmental Protections.

- Gaynor K.M., Brashares J.S., Gregory G.H., Kurz D.J., Seto K.L., Withey L.S., Fiorella K.J. Anticipating the impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on wildlife. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2020;18:542–543. doi: 10.1002/fee.2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi, Vietnam: 2006. Decree No. 32/2006/ND-CP Dated 30 March 2006 of the Government on Management of Endangered, Precious and rAre Forest Plants and Animals. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi, Vietnam: 2013. ree No. 157/2013/ND-CP Dated 11 November 2013 of the Government Stipulating the Sanction of Administrative Violations in fOrest Management, Forest Development, Forest Protection and Forest Product Management. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi, Vietnam: 2019. Decree No. 06/2019/ND-CP Dated 22 January 2019 of the Government on the Management of Endangered, Precious and Rare Forest Lora and Fauna and Implementation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi, Vietnam: 2019. Decree No. 35/2019/ND-CP Dated 25 April 2019 of the Government Stipulating the Sanction of Administrative Violations in the Forestry Sector. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam , 2019c. Decree No. 40/2019/ND-CP Dated 13 May 2019 of the Government Amending and Supplementing a Number of Articles of The Decree Detailing and Guiding the Implementation of Environmental Protection Law, Government of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Hogan J. Remoulding the critical junctures approach. Can. J. Political Sci. 2006;39:657–679. doi: 10.1017/S0008423906060203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan J., Doyle D. The importance of ideas: an a priori critical juncture framework. Can. J. Political Sci. 2007;40:883–910. doi: 10.1017/S0008423907071144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Wang F., Yang H., Valitutto M., Songer M. Will the COVID-19 outbreak be a turning point for China’s wildlife protection: new developments and challenges of wildlife conservation in China. Biol. Conserv. 2021;254 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huong N.Q., Nga N.T.T., Long N.V., Luu B.D., Latinne A., Pruvot M., Phuong N.T., et al. Coronavirus testing indicates transmission risk increases along wildlife supply chains for human consumption in Viet Nam, 2013-2014. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y., Yeophantong P., Lee T.M. Strengthening international legal cooperation to combat the illegal wildlife trade between Southeast Asia and China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021;9:105. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.645427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koju N.P., Kandel R.C., Acharya H.B., Dhakal B.K., Bhuju D.R. COVID‐19 Lockdown frees wildlife to roam but increases poaching threats in Nepal. Ecol. Evol. 2019;11:9198–9205. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Ma Z.F., Zhang Y., Zhang Y. Attitudes towards wildlife consumption inside and outside Hubei province, China, in relation to the SARS and COVID-19 outbreaks. Hum. Ecol. 2020;48:749–756. doi: 10.1007/s10745-020-00199-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao Cai Department of Forestry. 2022. Status of Widlife Trade in Lao Cai. Lao Cai Department of Forestry, Lao Cai province, Vietnam.

- Manenti R., Mori E., Di Canio V., Mercurio S., Picone M., Caffi M., Brambilla M., Ficetola G.F., Rubolini D. The good, the bad and the ugly of COVID-19 lockdown effects on wildlife conservation: Insights from the First European Locked down Country. Biol. Conserv. 2020;249 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara J., Robinson E.J., Abernethy K., Iponga D.M., Sackey H.N., Wright J.H., Milner-Gulland E.J. COVID-19, systemic crisis, and possible implications for the wild meat trade in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:1045–1066. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00474-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiratta, U. , Khanyari, M. , Velho, N. , Suryawanshi, K. , Kulkarni, N.U. , 2021. Key Informant Perceptions on Wildlife Hunting in India During the COVID-19 Lockdown. 〈www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.05.16.444344v1〉. (Accessed 1 September 2021).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), 2019. Circular No. 29/2019/TT-BNNPTNT Dated 31 December 2019 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Handling of Forest Animals Being Exhibits; and Forest Animals Voluntarily Submitted for Publication to the State by Organizations and Individuals, MARD, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Montgomery R.A., Macdonald D.W. COVID-19, health, conservation, and shared wellbeing: details matter. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020;35:748–750. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morcatty T.Q., Feddema K., Nekaris K.A.I., Nijman V. Online trade in wildlife and the lack of response to COVID-19. Environ. Res. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Assembly of Vietnam , 2017. Law on Forestry Dated 15 November 2017, National Assembly of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Newsome D. The collapse of tourism and its impact on wildlife tourism destinations. J. Tour. Futures. 2020 doi: 10.1108/JTF-04-2020-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein R.I. . Wildlife markets, COVID-19 and totalitarianism: a comment on Cawthorn. Ambio. 2021;50:1760–1761. doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01430-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister of Vietnam , 2020. Directive No. 29/CT-TTg dated 23 July 2020 of the Prime Minister on a Number of Urgent Solutions for Wildlife Management, 2020, Prime Minister of Vietnam, Hanoi, Vietnam.

- Rahman M.S., Alam M.A., Salekin S., Belal M.A.H., Rahman M.S. The COVID-19 pandemic: a threat to forest and wildlife conservation in Bangladesh? Trees For. People. 2021;5 doi: 10.1016/j.tfp.2021.100119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richard K. , Hernan C.E. , 2022. Situation Analysis on the Roles and Risks of Wildlife in the Emergence of Human Infectious Diseases, IUCN. 〈https://portals.iucn.org/library/efiles/documents/2022-004-En.pdf〉.

- Roe D., Dickman A., Kock R., Milner-Gulland E.J., Rihoy E., ‘t Sas-Rolfes M. Beyond banning wildlife trade: COVID-19, conservation and development. World Dev. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau D., Perry B., Grimard F. The consequences of COVID-19 and other disasters for wildlife and biodiversity. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:945–961. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00480-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz C., Loretto M.C., Bates A.E., Davidson S.C., Duarte C.M., Jetz W., Johnson M., et al. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1156–1159. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shreedhar G., Mourato S. Linking human destruction of nature to COVID-19 increases support for wildlife conservation policies. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020;76:963–999. doi: 10.1007/s10640-020-00444-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Science, Technology And Environment Committee. 2020. Report of Monitoring Results: the Implementation of Policies and Laws on the Implementation of the International Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Report number 1617 /BC - UBKHCNMT14, Ha Noi, Vietnam.

- Si R., Lu Q., Aziz N. Impact of COVID-19 on peoples’ willingness to consume wild animals: Empirical insights from China. One Health. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2021.100240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M.K.S., Smit I.P., Swemmer L.K., Mokhatla M.M., Freitag S., Roux D.J., Dziba L. Sustainability of protected areas: vulnerabilities and opportunities as revealed by COVID-19 in a national park management agency. Biol. Conserv. 2021;255 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder H. Literature review as a research methodology: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019;104:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Soga M., Evans M.J., Cox D.T., Gaston K.J. Impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on human–nature interactions: pathways, evidence and implications. People Nat. 2021;3:518–527. doi: 10.1002/pan3.10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakini G., Mwedzi T., Manyuchi T., Tarakini T. The role of media during COVID-19 global outbreak: a conservation perspective. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2021;14 doi: 10.1177/19400829211008088. (194008292110080). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turcios-Casco M.A., Gatti R.C. Do not blame bats and pangolins! Global consequences for wildlife conservation after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Biodivers. Conserv. 2020;29:3829–3833. doi: 10.1007/s10531-020-02053-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRAFFIC , 2020. Viet Nam Issues Ban on Wildlife Imports and Announces Closure of Illegal Wildlife Markets. 〈www.traffic.org/news/viet-nam-issues-ban-on-wildlife-imports-announces-closure-of-illegal-wildlife-markets/〉. (Accessed 1 September 2021).

- TRAFFIC . East Asia and Pacific Region Sustainable Development Discussion Papers. World Bank; Washington, DC, USA: 2008. What’s driving the wildlife trade? A review of expert opinion on economic and social drivers of the wildlife trade and trade control efforts in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- Vale M.M., Berenguer E., de Menezes M.A., de Castro E.B.V., de Siqueira L.P., Rita de Cássia Q.P. The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to weaken environmental protection in Brazil. Biol. Conserv. 2021;255 doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe P., Saayman A., Jacobs C. Assessing the economic impact of COVID-19 on the private wildlife industry of South Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021;28 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam Administration of Forestry, 2020. Vietnam Forestry Administration. 2020. Licensed Hatchery Code List, The Government of Vietnam. 〈https://tongcuclamnghiep.gov.vn/LamNghiep/Index/danh-muc-ma-co-so-nuoi-trong-da-duoc-cap-phep-4196?fbclid=IwAR1bstMlzKxiNT6SlF6Ao1HvJqMhvjjxopQWJBbpdl2z39xAwHVhNGUG0iA〉.

- VnExpress International, 2020. Vietnam to Ban Wildlife Trade Following Conservationists’ Demand. 〈https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-to-ban-wildlife-trade-following-conservationists-demand-4066078.html〉. (Accessed 1 September 2021).

- WCS, 2020. Has Vietnam Banned the Wildlife Trade to Curb the Risk of Future Pandemics? 〈https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/14625/Has-Vietnam-banned-the-wildlife-trade-to-curb-the-risk-of-future-pandemics.aspx〉. (Accessed 1 September 2021).

- Wei G. Food safety issues related to wildlife have not been taken seriously from SARS to COVID-19. Environ. Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfort A. COVID-19 and wildlife farming in China: legislating to protect wild animal health and welfare in the wake of a global pandemic. J. Environ. Law. 2021;33:57–84. doi: 10.1093/jel/eqaa030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Lu Z., Li X., Zhao X., Li B.V. Why do we need a wildlife consumption ban in China? Curr. Biol. 2021;31:R168–R172. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Mei F., Lu C. COVID-19, a critical juncture in China’s wildlife protection? Hist. Philos. Life Sci. 2021;43:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s40656-021-00406-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen Bai Department of Forestry. 2022. Wildlife status in Yen Bai. Yen Bai Department of Forestry, Yen Bai province, Vietnam.

- Yuan J., Lu Y., Cao X., Cui H. Regulating wildlife conservation and food safety to prevent human exposure to novel virus. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020;6:1741325. doi: 10.1080/20964129.2020.1741325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yung D.T.C., Abdullah M.T. Commentary on COVID-19: a threat to wildlife management. J. Sustain. Sci. Manag. 2021;16:1–9. doi: 10.46754/JSSM.2021.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zellmer A.J., Wood E.M., Surasinghe T., Putman B.J., Pauly G.B., Magle S.B., Lewis J.S., Kay C.A.M., Fidino M. What can we learn from wildlife sightings during the COVID‐19 global shutdown. Ecosphere. 2020;11 doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]