Abstract

Influenza is an acute respiratory infectious disease caused by the influenza virus, affecting people globally and causing significant social and economic losses. Due to the inevitable limitations of vaccines and approved drugs, there is an urgent need to discover new anti-influenza drugs with different mechanisms. The viral ribonucleoprotein complex (vRNP) plays an essential role in the life cycle of influenza viruses, representing an attractive target for drug design. In recent years, the functional area of constituent proteins in vRNP are widely used as targets for drug discovery, especially the PA endonuclease active site, the RNA-binding site of PB1, the cap-binding site of PB2 and the nuclear export signal of NP protein. Encouragingly, the PA inhibitor baloxavir has been marketed in Japan and the United States, and several drug candidates have also entered clinical trials, such as favipiravir. This article reviews the compositions and functions of the influenza virus vRNP and the research progress on vRNP inhibitors, and discusses the representative drug discovery and optimization strategies pursued.

KEY WORDS: Influenza virus, Drug design, Influenza polymerase, Ribonucleoprotein complex, Medicinal-chemistry strategies

Graphical abstract

This review summarizes compositions and functions of the influenza virus vRNP and the research progress targeting them, and discusses the representative inhibitors discovery strategies and optimization approaches pursued.

1. Introduction

1.1. Influenza

Influenza viruses are zoonotic human pathogens that present one of the major threats to public health. Over the last few years, frequent influenza outbreaks have brought substantial economic losses and social burden1. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) statistics, annually 1 billion estimated human influenza cases, of which 3–5 million are considered severe, result in about 290,000–650,000 deaths2. Although vaccines are available now, they need regular updating annually and are not always protective because of the antigenically labile of influenza viruses. Therefore, anti-influenza drugs are an essential measure for both prophylaxis and treatment.

Currently, three types of agents have been approved for treating influenza: M2 ion-channel inhibitors, neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors, and inhibitors targeting influenza virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) complex. Although these drugs play a crucial role in the warfighting against influenza virus, each of them has some drawbacks3. For example, M2 ion channel inhibitors have significant limitations, as they only inhibit influenza A virus and are ineffective to influenza B virus4,5. Most importantly, due to the mutation of viruses and long-term drug selection, influenza A viruses have become increasingly resistant to them6, 7, 8, 9. Therefore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) no longer recommends the use of M2 inhibitors to treat influenza A virus infections10. On the other hand, NA inhibitors are considered as first-line drugs for influenza therapy, even though emerging drug resistance issues have plagued their clinical application since 200911,12. All this highlights the urgent need to develop new chemical entities with novel mechanisms of action and reduced drug resistance potential13.

1.2. Influenza virus and its life cycle

Influenza viruses are enveloped viruses that belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family. According to the antigenic difference in matrix protein 1 (M1) and nucleoprotein (NP), influenza viruses can be divided into four types: A, B, C, and D. Influenza A virus is a primary virus that can cause seasonal or pandemic influenza and is highly infectious14. Consequently, as prioritized by the pandemic potential and severity of disease outcomes, influenza A is the central focus of drug discovery and mechanistic studies (including viral replication, transmission, viral-host interactions and drug resistance).

The life cycle of influenza A virus consists of following steps: binding, entry, replication, translation, assembly, budding and release15. The specific infection process is shown in Fig. 1: firstly, the viral surface protein hemagglutinin (HA) binds to the cellular sialic acid receptor, thus allowing influenza virus adheres to the cell surface and enter the host cell; and then the virus dissolves its membrane to release vRNPs and transports them into the nucleus, wherein the viral RNA polymerase initiates the synthesis of virus mRNA; after mRNA synthesis, it was exported from the nucleus and translated into viral proteins in the cytoplasm; viral proteins are processed in the endoplasmic reticulum, glycosylated in the Golgi body, and transported to the cell membrane; the newly formed vRNP is transported to the cytoplasm mediated by M1‒NS2 complex and integrated with viral proteins to form new viral particles; ultimately, NA cleaves terminal sialic acid (SA) residues between HA and the cellular receptors, releasing virions from the cell11,16.

Figure 1.

The life cycle of influenza A virus.

As mentioned above, influenza virus RNA polymerase plays a central role in viral replication: it is responsible for the synthesis of viral mRNAs and viral genomic RNA (vRNA) through intermediate complementary RNA (cRNA). In addition, NP is primarily considered to play an important role in mediating the nuclear export of progeny vRNPs17. Consequently, this article briefly introduces the contemporary medicinal chemistry strategies for the discovery and optimization of inhibitors that target influenza vRNP constituent proteins.

2. Structure and function of vRNP

Influenza viruses generally contain segmented single-stranded negative RNA genomes, and each genome is composed of eight segments of vRNA18. The vRNA binds to multiple copies of NP and a heterotrimeric RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) complex to form a whole assembly called viral RNA ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) which perform the functions necessary for the completion of the viral life cycle (Fig. 2A)19.

Figure 2.

(A) Structure diagram of vRNP; (B) X-ray crystal structure of the PAN domain (purple spheres represent metal ions, PDB code: 2W69)23; (C) The crystal structure of the cap-binding domain (PB2cap) bound to the m7GpppN-cap (PDB code: 4NCE)25; (D) The RNA-binding site of PB1 (PDB code: 4WSB)28. The graphics are displayed by PyMOL software.

2.1. Structure and function of RdRp

2.1.1. PA, PB1 and PB2

The influenza virus RdRp complex consists of three subunits: polymerase basic protein 1 (PB1), polymerase basic protein 2 (PB2) and polymerase acidic protein (PA)20. Different from other viruses, influenza viruses do not have the ability to synthesize the 5′-cap structure, which is required for translation, therefore they execute a unique “cap-snatching” process during replication as follow: firstly, PB2 protein captures a pre-mRNA by tightly binding to the 5′-cap structure from the host cell; next, PA endonuclease domain cleaves 8–14 nucleotides from the cap structure to yield a 5′-capped RNA fragment; finally, this sequestered RNA fragment serves as a primer for initializing viral RNA synthesis by the PB1 protein21.

PA subunit possesses endonuclease and protease activity, participating in the process of virus replication and transcription. The PA subunit comprises two domains, the C-terminal domain (PAC) and the N-terminal domain (PAN), linked by a long flexible peptide chain. The PAN domain has an α architecture that consists of five α-strands surrounded by seven α-helices22. PAN endonuclease is a dinuclear metalloenzyme that can bind to either Mg2+ or Mn2+ cations. And the metal-chelating catalytic site of PAN is a negatively charged pocket, consisting of His41, Lys134, Glu80, Asp108, and Glu119 (Fig. 2B)23,24.

The PB2 subunit contains a cap-binding domain that binds the 7-methylated guanosine moiety (m7GTP) at the 5′-end of the host pre-mRNA. Crystallographic studies showed that the m7GTP is sandwiched by the aromatic side chains of Phe404 and His357, and forms hydrogen bonds to the side chains of Glu361 and Lys376 (Fig. 2C)25. Transcription is initiated by PB2 subunit capturing the 5′-cap structure of the host pre-mRNA, which is performed via the so-called “cap-snatching” mechanism and is dominated by PB2 cap-binding domain. In this course, PB2 subunit binds the 5′-capped end of host pre-mRNA, which is cleaved by PA endonuclease. And the “snatched” 5′-capped primer is utilized as a viral template by PB1 subunit for transcription of viral mRNAs26,27.

The PB1 protein of the influenza virus contains a conserved polymerase domain, which has the functions of nucleotide polymerization and chain extension, being the core subunit of the influenza virus polymerase heterotrimer. The intact RNA promoter is bound to the residue 670–679 of PB1 subunit in an arc-shaped conformation (Fig. 2D)28, and this means that in the process of RNA synthesis, the RNA binding site of PB1 must undergo additional conformational changes to ensure the progress of RNA from the initial stage to the extension stage29.

2.1.2. The protein–protein interactions

The protein–protein interactions (PPIs) between polymerase PA, PB1 and PB2 subunits are essential for the transcription and replication of the influenza virus. Protein crystallography and co-precipitation experiments showed that N-terminal residues 1–86 of PB2 could interact with residues 678–775 of the C-terminal of PB1. This interaction is a typical PPI and termed as PB1‒PB2 interaction30. Both PB1C and PB2N are composed of three α-helixes. The α1 helix of PB2N is opposite to the α2 and α3 helix of PB1C, while α1 helix of PB1C is fixed between three helixes of PB2N, forming a closely combined polar interaction network30, 31, 32. Most of the interaction energy in the PB1‒PB2 binding interface is contributed by the α1 helix of PB2N. The interaction includes four salt bridges and eight hydrogen bonds between peptides involved in the main chain atoms (Fig. 3)33,34.

Figure 3.

(A) A ribbon diagram showing the helices of PB1C and PB2N (PDB code: 2ZTT) in purple and green, respectively; (B) Extensive interactions occurring between PAC and PB1N (PDB code: 3CM8). The graphics are displayed by PyMOL software.

On the other hand, the crystallographic studies show that PB1N could interact with four α-helices (α8, α10, α11 and α13) of PAC and form a hydrophobic core31. Thus, PAC‒PB1N interaction is driven through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions35. Since PPI inhibitors work on both two proteins, resistance will only develop when at least one amino acid residue on both proteins is mutated at the same time, suggesting that PPI inhibitors are not prone to induce drug resistance and could overcome some limits of current anti-influenza drugs36.

2.2. Structure and function of influenza virus NP

NP is a phosphorylated protein encoded by the fifth segment of the RNA genome. It is one of the most abundant viral proteins produced during virus replication. NP is a key component of the vRNP complex, whose functions include RNA packing, nuclear trafficking, vRNA transcription and replication. It has nuclear localization signal (NLS), nuclear accumulation signal (NAS) and nuclear export signal (NES), which can mediate the enrichment, replication and export of vRNP in the host cell nucleus. The NP can also bind to PB1 and PB2 subunits and act as a scaffold in the influenza virus ribonucleoprotein bodies37,38.

NP monomer can be divided into head, body and tail, which can be inserted into adjacent NP monomer through flexible tail loop to assemble NP oligomers (Fig. 4). NP can interact with cellular peptides, including actin, nuclear import and export devices and nuclear RNA helicase of host cells. The NP structure among the different subtypes of Orthomyxoviridae is relatively conservative, making NP an attractive target for anti-influenza drug design39.

Figure 4.

NP monomer (PDB code: 2IQH). The graphic is displayed by PyMOL software.

3. Inhibitors targeting vRNP constituent proteins

3.1. The PA inhibitors

Currently, baloxavir is the only endonuclease inhibitor approved for clinical use. Besides, several kinds of small molecular PA inhibitors with different chemical structures have been reported, including diketonic acid derivatives, flutimide derivatives, hydroxylated heterocycles, catechol derivatives, 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid derivatives, and its biological isomers.

3.1.1. Diketonic acid derivatives

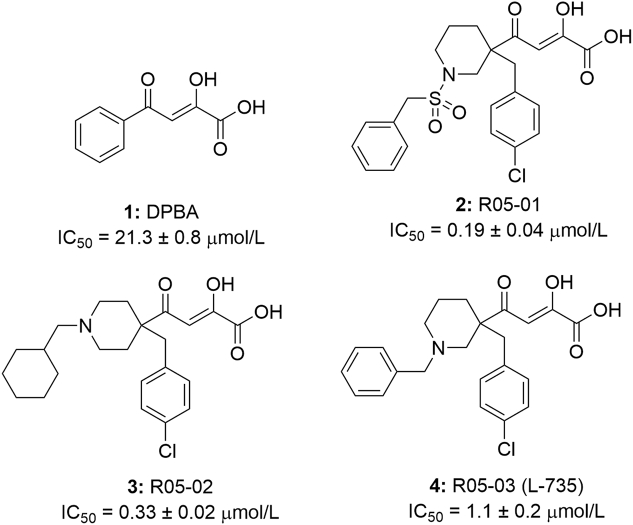

Diketonic acid derivatives are the first class of highly selective influenza virus cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitors found so far40,41. The diketobutyric acid moiety is not only the key to chelating with PA metal ions but also the guarantee of anti-influenza activity. The discovery of this kind of structure provides a forerunner for the design and development of PA metalloenzyme inhibitors. Tomassini et al.42 had identified a series of 4-substituted 2-dioxobutyric acid compounds, including DPBA (1), R05-01 (2), R05-02 (3) and L-735 (R05-03, 4), etc. (Fig. 5), that were highly selective to the polymerase of influenza A and B viruses. And they could specifically inhibit influenza polymerase endonuclease activity with IC50 values ranging from 0.19 to 21.3 μmol/L. Among them, piperidine-substituted dioxobutanoic acids (2) were the most effective analogue (IC50 = 0.19 μmol/L)38,43,44.

Figure 5.

Examples of 4-substituted 2,4-dioxobutanoic acid derivatives as PA inhibitors.

3.1.2. Flutimide derivatives

In 1994, Tomassini et al.42,45 reported a series of 4-substituted 2-dioxobutyric acids as specific PA inhibitors. Subsequently, they reported a fully substituted 1-hydroxy-3H-pyrazine-2,6-dione (5, flutimide), which was identified in fermentation extracts of a new fimicolous Loculoascomycetes fungus, Delitschia cofertaspora. After evaluating the PA inhibitory activities of several chemically synthesized flutimide derivatives, the researchers carried out the structural modifications at various positions. It was noticed that compounds bearing benzyl substituted isobutyl group exhibited good antiviral activities. They also observed that when the double bond of the piperazine ring in compound 6 disappeared, the activity (compound 7) decreased nearly 100 times. Therefore, it was inferred that the olefin group was required for the activity, and it could be improved more by the aromatic substitution of isopropyl side chain. Besides, compound with p-methoxybenzylidene group at C-5 of 3H-pyrazine-2,6-dione moiety was found to be the most effective analogue (compound 8) with IC50 value of 0.8 μmol/L (Fig. 6)46,47.

Figure 6.

Examples of flutimide and related analogues as PA inhibitors.

3.1.3. Hydroxylated heterocycles

Bauman et al.48 carried out a fragment-based screening using the high-resolution crystal structure of 2009 H1N1 influenza A endonuclease domain (PAN), leading to the identification of 3-hydroxypyridin-2(1H)-ones as a new bimetallic chelating ligand for tightly binding the active site of PA endonuclease. Subsequently, based on structural optimization, the researchers developed two novel series of compounds (3-hydroxypyridin-2(1H)-ones and 3-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones) as PA endonuclease inhibitors49,50.

Several 5,6-phenyl substituted 3-hydroxypyridine-2(1H)-ones are good influenza A virus endonuclease inhibitors, and research had proved that the presence of phenyl at both 5- and 6-positions further enhanced their potency. Among them, analogues 9 and 10 exhibited great potency (IC50 = 0.011 and 0.023 μmol/L, respectively)48,51. As for another kind of chemical entity, 3-hydroxyquinoline-2(1H)-one series, 6- or 7-(p-fluorophenyl)-3-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-one (11 and 12) were found to be the most effective influenza A H1N1 endonuclease inhibitors with IC50 values both of 0.5 μmol/L (Fig. 7)49,52.

Figure 7.

Hydroxylated heterocyclic derivatives as influenza virus endonuclease inhibitors.

3.1.4. Catechol derivatives

Polyphenol compounds such as tea catechin53, marchantin B54, perrottetin F55, phenethylphenylphthalimide analogue56, salicylic acid derivative and gallic acid derivative have been found to inhibit the function of PA endonuclease because of their catechol structure.

Considering tea polyphenols as example, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (13, EGCG) and epicatechin gallate (14, ECG) are natural products extract containing catechol structure, which has the function of regulating PA endonuclease. However, due to its low membrane permeability, their antiviral activity in cellular level is not ideal. Although mono-esterification increased their antiviral activity, their cytotoxicity was also increased. Compared to other PA inhibitors, these compounds still needed further optimization53. In 2018, Ferro et al. reported that dopamine (3,4-dihydroxyphenylethylamine) could chelate the two metal ions in PA active site and was a potential PA endonuclease inhibitor57. Based on this, the incorporation of a methylene group between the amide and the aromatic ring led to compound 15, and the more rigid 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-6,7-diol fragment was used to replace the flexible part of dopamine to afford compound 16. These two dopamine derivatives showed excellent PA endonuclease inhibitory activity (15, EC50 = 2.46 μmol/L; 16, EC50 = 2.58 μmol/L) (Fig. 8)58. Of note, the catechol derivatives were known to have polypharmacology and are promiscuous compounds, so their antiviral activity might not be solely resulted from PA inhibition.

Figure 8.

Catechol derivatives as influenza virus endonuclease inhibitors.

3.1.5. Baloxavir and its derivatives

In October 2018, the cap-dependent endonuclease (CEN) inhibitor baloxavir marboxil (BXM), was firstly licensed for the treatment of influenza type A and B virus infection, which was an important milestone in developing new anti-influenza virus drugs. BXM, trade name Xofluza, is a prodrug that is metabolized into baloxavir acid, which directly inhibit the cap-snatching process during viral mRNA biosynthesis and finally effectively prevents virus replication59, 60, 61. This compound was optimized from RO-7 which was broad-spectrum CEN inhibitor and the discovery process is briefly described in Section 4.162. And the X-ray crystal complexes show that baloxavir adopts a butterfly-shaped conformation in the PA active site (PDB code: 6FS6); one side of the nitrogen heterocyclic ring coordinates with the Mn2+ of the PA endonuclease to inhibit the activity of the endonuclease, while the dihydrodibenzothiophene ring binds to the adjacent pocket of the active site of the PA endonuclease through hydrophobic interaction. Those characteristics enable baloxavir to combine with the target to the maximum extent (Fig. 9) and make it highly effective, requiring only one tablet to achieve influenza virus suppression63,64. As in a phase III study, patients (aged 12–64 years) with uncomplicated influenza, a single dose of BXM displayed shorter time to alleviate symptoms of influenza than placebo, and exhibited decrease in viral titers compared with placebo and oseltamivir. However, in vitro studies have revealed that the mutation PA I38X were detected in 2.2%–9.7% of baloxavir-treated patients, and exhibited reduced susceptibility to BXM by 20–40 fold65. Therefore, in the future, the rapid emergence of drug resistance could become a significant obstacle to antiviral therapy with BXM66,67. At present, substantial efforts were devoted to developing polyheterocyclic CEN inhibitors as candidates for treating influenza infection. In addition, numerous analogues of BXM have been patented (WO2012039414A1, WO2019052565A1, WO2016175224A1) since 2016, but there are still no more compounds with clinical prospects beyond BXM.

Figure 9.

The structures of RO-7, baloxavir and the complex structure of baloxavir binding with H1N1 endonuclease (PDB code: 6FS6).

3.2. Inhibitors targeting the PB2 cap-binding domain

Transcription is a primer-dependent process. Because the influenza virus cannot produce 5′-terminal 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap primers, and the 5′ cap primers are obtained through the “cap-snatching process”68,69. In this process, the viral RdRp needs to use the PB2 cap-binding domain (CBP) to capture the 5′ cap of the newborn host capped RNA. PB2 inhibitors can bind to the active site of PB2 cap-binding domain, thus blocking the natural ligand (m7GTP) and preventing viral RNA synthesis. Interestingly, due to the difference between the major sequence of PB2 domains of influenza A and influenza B viruses, PB2 inhibitors are effective only against influenza A virus70,71.

Among them, the most intensely studied PB2-cap inhibitor is pimodivir (19) (also known as JNJ-63623872 and VX-787), discovered by Clark et al.25 in 2014. VX-787 was a PB2 inhibitor developed through extensive and iterative optimization. The X-ray crystal structure of the influenza A virus PB2 domain with VX-787 showed that the compound optimally occupies the m7GTP binding pocket72,73. The azacyclic scaffold of VX-787 formed hydrogen bonds with Lys376 and Glu361 residues in the PB2 domain, and the three aromatic rings of VX-787 formed a π-stack with the side chains of His57, Phe23, and Phe10474. In addition, the carboxylic group of VX-787 formed two water-mediated interactions with residues Arg55, Gln106, and His57 (Fig. 10). In particular, optimal interaction with hydrophobic residues and alkaline residues was achieved by introducing the dicyclooctane-carboxylate part. The affinity of VX-787 to the PB2 cap-binding domain of isolated influenza A virus was about 24 nmol/L, which was 60 times higher than that of m7GTP. And the EC50 values of VX-787 for various influenza A virus strains ranged from 0.13 nmol/L to 3.2 μmol/L70,72. Notably, compared to the NA inhibitor oseltamivir, VX-787 was significantly effective in preventing and treating influenza A virus infection in mouse models, even in delayed start-up trials75. However, due to the unsatisfactory results of clinical phase III study, the development of VX787 has been recently halted76. One possible reason was that the pyrimidine-7-azacyclohexane motif of VX-787 could be metabolized by human aldehyde oxidase, resulting in poor pharmacokinetics77. Another reason was that in relevant resistance studies, six drug resistance mutations (Q6H, S24I, S24N, S24R, F104Y, and N210T) were found in PB2, that reduced the sensitivity of VX-787 by at least 60-fold73.

Figure 10.

The X-ray structure of VX-787 (PDB code: 4P1U) bound to the PB2 cap-binding domain and structures of representative PB2 cap-binding inhibitors.

Using feasible drug development strategies to find PB2 inhibitors with new chemical structure is also ongoing. In 2015, Roch et al.78 reported two compounds 20 and 21 (Cap-3 and Cap-7) that could inhibit viral transcription and replication by targeting PB2, but they were less potent than VX-787 (1 μmol/L < EC50 < 10 μmol/L). Additionally, in 2016 Boyd et al.79 have synthesized several VX-787 analogues and evaluated their potency in enzymatic assays and cell culture. Among them, compounds 22 (IC50 = 0.001 μmol/L) and 23 (IC50 = 0.006 μmol/L) with different carboxylic acid bioisosteres showed similar potency and binding mode to VX-787 (Fig. 10).

3.3. Inhibitors targeting influenza virus polymerase subunit protein–protein interactions (PPIs)

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) play a crucial role in forming the influenza virus RNA polymerase complex80. Due to the essential functions and highly conserved protein sequences, polymerase activity and virus replication can be blocked by interfering PPIs between subunits (namely PA‒PB1 interaction and PB1‒PB2 interaction)75,81. In these PPIs, the interaction interface between PA and PB1 is extensive, as the total buried surface area is 17,330 Å2; and the interaction between PB1 subunit and PB2 subunit also generate a broad interface with a total buried surface area of 14,100 Å2. In contrast, the PA subunit interacts marginally with the PB2 subunit, leading to a small interface (2880 Å2)35,75,82. Therefore, the large binding interface between PA‒PB1 and PB1‒PB2 makes them attractive targets for developing new antivirals.

3.3.1. Polymerase PA‒PB1 inhibitors

3.3.1.1. Benzofurazan derivatives

In order to discover the compounds that can effectively block the interaction of PA‒PB1, Kessler et al.83 screened a group of chemical libraries using a new ELISA screening method. They identified benzofuran compound 24 that could block the binding between PA‒PB1 and inhibit virus replication at the micromolar level (EC50 = 5 μmol/L). Prompted by this, Pagano et al.84 synthesized various benzofuran derivatives to explore the chemical space around heterocyclic nucleus. With the aim to improve the solubility and activity of novel compounds in cell assays, they introduced an aromatic heterocycle bound to the phenyl ring at C-4 position and finally obtained compound 25 endowed with high anti-H1N1 activity (IC50 = 1 μmol/L) (see Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Structures and activities of benzofurazan derivatives as PA–PB1 heterodimerization inhibitors.

3.3.1.2. Thiophene-3-carboxamide derivatives

Muratore et al.85 screened about 3 million compounds from the ZINC database used the structure-based drug discovery (SBDD) strategy. From this screening, 32 compounds emerged as potential candidates and were then evaluated for their ability to interfere the PA‒PB1 interaction in vitro. It was found that thiophene-3-carboxamide derivative 26 could block the interaction of PA‒PB1 in vitro with an IC50 of 90.7 μmol/L. Although EC50 values are higher than 100 μmol/L in infected cells, this compound could be used as an effective starting point due to its unique mechanism and no cytotoxicity (CC50 > 250 μmol/L) in two cell lines (Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T)85, 86, 87. Consequently, Massari et al.86 synthesized a more effective PA‒PB1 inhibitor 27 (IC50 = 25.4 μmol/L, EC50 = 18 μmol/L, CC50 > 250 μmol/L) by modifying the substituent at C-2 position of 26.

Based on this skeleton, Desantis et al.88 substituted 2-pyridyl, p-chlorophenyl and p-fluorophenyl for C-2 hydroxyphenyl to obtain compounds 28, 29 and 30 (EC50 = 1.2–2.6 μmol/L) that displayed robust antiviral activity. In addition, the activity of 31 (C-3 thiazole derivative) and 32 (C-2 p-aminophenyl derivative) also reached the micromolar level (Fig. 12). This research team continued focusing on above compounds and found that there were few resistant strains emerged toward them under drug selection. Therefore, these inhibitors provide a new possibility to overcome drug resistance89.

Figure 12.

Structures of the thiophene-3-carboxamide derivatives as PA‒PB1 inhibitors.

3.3.1.3. 4,6-Diphenyl-pyridine derivatives

Previous studies had identified new 4,6-diphenyl-pyridine (or pyrimidine) derivatives that could inhibit viral polymerase by disrupting the PA‒PB1 interaction88. Consequently, starting from the structure of 3-cyano-4,6-diphenyl-pyridines, Botta' group and Massari et al.90,91,92 chemically modified the bicyclic core to obtain hybrid molecule 33 which was the most effective with IC50 value of 1.1 μmol/L. Next, with compound 33 as lead, Massari et al.93 designed and synthesized cyclopentathiophene derivative 34, phenyl derivative 35, and cycloheptathiooxazinones 36 and 37 (Fig. 13). Very recently, the same group reported other 1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines as influenza polymerase PA–PB1 interaction disruptors94. These derivatives displayed robust potency in enzymatic level, and the researchers concluded that reducing unnecessary hydrophobic groups and introducing proper polar groups was more conducive to the formation of hydrogen bond interaction with PA subunits which was beneficial to antiviral activity.

Figure 13.

Structures of the 4,6-diphenyl-pyridine derivatives as PA‒PB1 inhibitors.

3.3.1.4. ANA-1

In 2010, Kao et al.95 screened a chemical library of 950 compounds using ELISA assay. From the results, an effective compound ANA-1 (38) was identified (Fig. 14). Its mechanism may be to destroy the PA‒PB1 interaction by inducing conformational changes of PAC. ANA-1 has a strong antiviral effect with EC50 values of 0.55 μmol/L. Intranasal injection of ANA-1 could protect mice from lethal attack and reduce the viral load in mice lung with infecting H1N1 virus34.

Figure 14.

Structures of the ANA-1, thiazole compounds, AL18 and 4-(2-keto-1-benzimidazolinyl)piperidine derivatives as PA‒PB1 inhibitors.

3.3.1.5. Thiazole compounds

Zhang et al.80 established an in vitro split luciferase complementation-based assay, and used it to found PA‒PB1 inhibitors R160792 (39) and R151785 (40) (Fig. 14). These two compounds exhibited broad-spectrum antiviral activity against a panel of influenza A and B viruses. Mechanism study showed that 40 could inhibit the nuclear localization function of PA and reduce viral RNA replication, thereby exerting antiviral effects.

3.3.1.6. AL18

Muratore et al.85 used a small-molecule inhibitor of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) DNA polymerase, AL18 (41) (Fig. 14), as a negative control when identifying PA‒PB1 inhibitors. Surprisingly, AL18 was proved to have the ability to block the PA‒PB1 interaction. In addition, the compound could inhibit influenza A and B virus replication in infected cell cultures, with an IC50 value of about 20 μmol/L. Molecular docking study showed that the aromatic part of AL18 participated in π-stacking with W706 and formed hydrogen bonds with Asn412, Gln408 and Lys643 of PA subunit96.

3.3.1.7. 4-(2-Keto-1-benzimidazolinyl)piperidine derivatives

In 2018, Zhang et al.97 utilized the multi-component reaction to explore antiviral drug candidates, and encouragingly, compound 42 was found to significantly inhibit the PA‒PB1 interaction. This compound shows broad-spectrum anti-influenza virus activity against several influenza A and B viruses, with an EC50 ranging from 0.6 to 2.7 μmol/L. Furthermore, it was worth noting that compound 42 did not appear drug resistance under the pressure of drug selection, which was worthy of further study (Fig. 14).

3.3.2. Polymerase PB1‒PB2 subunit interaction inhibitors

In 2017, Yuan et al.98 developed a modified ELISA assay to screen a library of 950 compounds for discovering PB1‒PB2 inhibitors. Among them, small molecule PP4 (43) exhibited a strong inhibitory effect on PB1‒PB2 interaction (IC50 = 12.9 μmol/L) and strong antiviral activity (EC50 = 4.2 μmol/L). Based on this chemical structure, they further synthesized 12 analogues and eventually found pyrazolidine-3,5-dione derivative PP7 (44). It was turned out to have great activity in both cellular level and enzymatic level (IC50 = 8.6 μmol/L, EC50 = 1.4 μmol/L, CC50 > 500 μmol/L)33,75, and was the most active PB1‒PB2 inhibitor found so far (Fig. 15).

Figure 15.

Examples of the PB1–PB2 inhibitors.

3.4. PB1 inhibitors

Favipiravir (T-705, 45) (Fig. 16) is a nucleobase analogue of viral RdRp, its triphosphate active form can be misidentified by RdRp as a purine and integrated into nascent RNA, ultimately leading to lethal synthesis of the viral RNA strand. Favipiravir shows great inhibitory activity against many subtypes of influenza virus with EC50 values of 0.19–22.5 μmol/L99. Also, it shows a good synergistic effect with oseltamivir, and has received conditional approval for use in Japan. Of note, favipiravir has inhibitory activity against a variety of RNA viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. However, the specific mechanism of its interaction with RdRp is not very clear now and needs to be further studied100.

Figure 16.

Chemical structure of PB1 inhibitors.

Ribavirin (46) (Fig. 16), a typical nucleoside antiviral inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug that is widely recognized as a competitive inhibitor of host monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) and was approved for use in viral infections as early as 1986. IMPDH catalyzes the conversion of guanosine monophosphate (GMP) to guanine triphosphate (GTP). Inhibition of this enzyme could reduce intracellular GTP, which leads to an imbalance in nucleotide concentration, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of viral proteins and exerting an antiviral effect. In addition, ribavirin can mimic the nucleotide substrate to make the PB1 subunit misrecognized during replication, leading to lethal synthesis and thus inhibiting the replication process of RdRp101.

Compounds 367 (47) and ASN2 (48) were both non-nucleoside inhibitors targeting RdRp obtained by cell-based high-throughput screening (Fig. 16). The resistance mutations of these two compounds were H456P and Y449H of PB1, respectively. These two residues locate around PB1, so they may be effective PB1 inhibitors. Among them, compound 48 has better potency against influenza A virus with EC50 value of 3–14 μmol/L, and CC50 value of 300.5 μmol/L, which has better potential for development102, 103, 104.

3.5. NP inhibitors

NP is highly conserved between different influenza subtypes and does not have corresponding counterpart in the host, making it an excellent antiviral target. With the reveal of the X-ray crystal structure of NP, the mechanism of action of NP has been gradually understood and NP inhibitors are mainly divided into the following three categories based on the mechanism: blocking the interaction between NP and RNA, inhibiting the formation of NP oligomers, and inhibiting the nuclear export of NP39,105.

3.5.1. NP inhibitors that affect the binding of NP to RNA

Lejal et al.106 screened cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors against influenza A virus activity and found naproxen (49), a marketed anti-inflammation drug, that could interact with the RNA binding groove of NP, thereby competitively inhibited the binding of NP protein to viral RNA.

Hagiwara et al.107 found that mycalamide A (50) has a high affinity with NP protein. SPR experiments showed that this compound could bind to the 110 residues of the N-terminal of NP protein, and affecting the nuclear transport function and RNA binding function.

KR424 (51), selected from a chemical library containing 50,000 compounds, also acts on NP protein. This compound binds to a pocket composed of the RNA binding groove of NP protein, the NP dimer interface, and NES. This would cause NP to accumulate in the host cell nucleus and could not be exported so that inhibited the synthesis of vRNP (Fig. 17A)16.

Figure 17.

The representative NP inhibitors. (A) NP Inhibitors affect the binding of NP to RNA; (B) NP inhibitors block oligomerization of NP monomer; (C) NP inhibitors block nuclear output.

3.5.2. NP inhibitor that inhibits oligomerization of NP monomer

Nucleozin (52) is the most widely studied class of NP inhibitors at present, with EC50 value of 0.069–0.16 μmol/L against a panel of influenza viruses. It can induce the dimerization of NP to form high-level NP oligomers, thereby inhibiting virus nuclear accumulation and working in the early and late stages of the influenza virus life cycle95. Specifically, each of the two nucleozin plays the role of a molecular glue that joins two NP monomers together. And each molecule interacts with Y52 pocket from one monomer and the Y289/N309 pocket from another monomer95.

Moreover, the anti-influenza effect of nucleozin analogue 53 is also closely related to NP protein. The researchers speculated that this compound could insert into the Arg99 and Tyr52 residues or between Tyr52 and Tyr313 residues of NP to destroy the stability of the tail ring of NP, leading to the inhibition of oligomerization in NP monomers102.

S119 (54) is a specific inhibitor of influenza A virus and its structure is similar to nucleozin. This structure shows a high affinity for NP and can disrupt the oligomerization of NP and inhibit influenza virus replication with IC50 value of 0.06 μmol/L in MDCK. In generally, the NP inhibitors only inhibit influenza A virus but not influenza B virus, but a study reported in 2018 showed that S119 could also inhibit influenza B virus. Moreover, the asymmetrical analogue of 54 (compound 55) showed more broad-spectrum antiviral activity (H1N1, EC50 = 1.43 μmol/L; B/Yamagata/16/1988, EC50 = 2.08 μmol/L; B/Brisbane/60/2008, EC50 = 15.15 μmol/L) than 54. And 55 showed a synergistic relationship with oseltamivir (Fig. 17B)108.

3.5.3. NP inhibitors that inhibit nuclear export

Research by Jang et al.109 found that the spiro compound KR-23502 (56) had an inhibitory effect on both influenza A and B. Mechanism studies revealed that the compound mainly interferes in the middle and late stages of virus replication by inhibiting the nuclear export process of influenza virus vRNP and M1. Further study showed although a single mutation at position 54 of M1 (D54G) was found in the 18th generation virus under the drug-induced pressure, the effective concentration of 56 was only tripled, indicating that the compound had a relatively high genetic barrier.

Huang et al. screened a compound library used cell-based infection experiments to discover compound ZBMD-1 (57), which showed inhibitory activity against H3N2 and H1N1 in vitro. Further mechanism studies showed that this compound could bind the NES region of NP protein, thereby inhibited the nuclear export process of NP110.

In addition, a class of itaconic acid derivatives had also been identified to have anti-influenza A virus effects by mainly reducing the nuclear output of NP. Among them, compound 58 was the most potent antiviral agent with an EC50 value of 0.14 μmol/L and selectivity index value of over 785111 (Fig. 17C).

4. Medicinal chemistry strategies in seeking lead compounds targeting vRNP constituent proteins

4.1. The “privileged structure” repositioning approach

The “privileged structure” repositioning is a strategy that discover candidate drugs with new pharmacological functions from the existing privileged scaffolds based on targets and structural information112,113. The prerequisite of the “privileged structure” repositioning is polypharmacology or drug promiscuity, which means that one drug can combine with multiple targets. This strategy has attracted medicinal chemists to explore new targets for existing drugs64. A lot of drugs or active structures have not been wholly utilized due to their low efficacy and safety issues that occurred in clinical trials. Fortunately, “privileged structure” repositioning is an excellent strategy to work on those existing molecules and obtain effective drugs. These existing structures can be quickly studied and marketed for new disease targets, and the research time and cost can be significantly reduced in pharmacokinetic experiments114,115.

At present, similar strategies have been successfully applied to the discovery of PA endonuclease drugs. The metal coordination on HIV integrase domain is similar to that of influenza virus PA endonuclease, which maintains the enzyme activity through the mechanism of two divalent metal ions66. Thus, seeking inhibitors that coordinate with the metal ions (namely the metal chelating strategy) could effectively block the endonuclease activity and prevent the processing of biological substrates35. This is of great significance for the discovery of PA endonuclease inhibitors and is well exemplified. Takahashi and his colleagues published a patent (WO2016175224A1), and speculated that the metal-chelating pharmacophore in the structure of HIV integrase inhibitor dolutegravir (59) could also target the influenza virus PA endonucleases. And a classic example of discovering PA inhibitors was as process: (i) aiming at the hot spot of metal-chelating pharmacophore binding of HIV integrase domain, a small drug library was constructed16; (ii) HTS screened the privileged drug scaffolds to determine the optimal fragment combination. (iii) Linking of the fragment hits to generate possible hit compounds as templates. (iv) Similarity search of template compounds in drug databases to identify existing drugs as potential influenza endonuclease inhibitors (Fig. 18). Eventually, compound RO-7 was screened out in this way112,116. And the best endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir was obtained by further optimization of RO-7.

Figure 18.

Discovery of highly potent and selective PA inhibitors based on “privileged structure” repositioning.

Naproxen has been on the market for a long time as an anti-inflammatory drug. Lejal et al.106,117 through simulated screening found that it can target the NP‒NP binding site and the NP RNA binding groove to prevent the corresponding functions of NP. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations showed that the structure of naproxen fitted into the RNA binding groove of NP, therefore naproxen could compete with RNA for binding to NP. The in vivo and in vitro experiments showed it had good antiviral effects on both H1N1 and H3N2 strains. Dilly et al.118 synthesized a series of NP protein RNA binding groove inhibitors based on naproxen. Among these synthesized compounds, 60 and 61 were more potent, targeting highly conserved residues in the RNA binding groove of NP protein, stabilizing the NP monomer and having no COX2 inhibitory activity. Compared with naproxen, 60 and 61 showed a better antiviral effect in cell viability experiments, and could protected mice from lethal virus attacks. This team also made further structural modifications on 61 to obtain compound 62. In vitro cell experiments showed that the activity of 62 had been dramatically improved compared to 61, and it was also great for oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 strain. Mechanism studies speculated that compound 62 hindered the binding of NP to RNA and to PAN (Fig. 19).

Figure 19.

Discovery of highly potent and selective NP inhibitors based on “privileged structure” repositioning.

4.2. Crystallographic fragment screening

Crystallographic fragment screening is a new technique for initiating drug discovery. This method is to immerse high-resolution X-ray diffraction crystals in an organic solvent, and the superimposed crystal structure obtained by immersing in different organic solvents can explore the interaction between small molecules and target binding sites. This structural information can be used to develop pharmacophore models or improve the affinity and specificity of lead compounds51.

Bauman et al.48 had taken previously assembled diverse compound libraries to soak the fragments into preformed crystals and screened them by X-ray crystallography. Although the fragment library did not contain metal chelating agents, 159 compounds out of 775 were found to have potential chelating moieties. Among the 159 potential metal chelating agents, 8 fragments could inhibit PAN. Finally, it was determined that the structure of 5-bromo-3-hydroxypyridine-2(1H)-one (63) could combine with the bimetallic chelating active site in PA endonuclease. Further modification showed that compounds with monosubstitution either at 5- and 6-position of 63 had similar IC50 values (64, 65 and 66). On the other hand, incorporating substituents at both 5- and 6-positions afforded compounds 67, 68 and 69, which resulted in 1000-fold more potent than the initial hit 63. Especially, compounds 68 and 69 displayed notable activities with IC50 values of 11 and 23 nmol/L, respectively (Fig. 20). This study concluded that the strategy based on crystallographic fragment screening was also a useful method for discovering and optimizing PA inhibitors119.

Figure 20.

Discovery of highly potent and selective PA inhibitors through crystallographic fragment screening.

4.3. Fragment-based drug discovery

At present, fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) has become an attractive method to identify and explore the diversity of medicinal chemistry120. Compared with traditional high-throughput screening29, FBDD has the following advantages: (i) it can be performed with a small compound library; (ii) it has a higher probability of discovering bioactive small molecules; (iii) FBDD designed drugs have higher activity and selectivity, which can provide the more effective chemical platform to combine with other regions. At the same time, it gives molecules higher ligand efficiency (LE) and good drug-like properties121.

To discover novel and potent PA endonuclease inhibitors, in 2016, Credille et al.119 used a FBDD method to screen a metal-binding fragment library containing approximately 300 molecules and found that pyromeconic acid skeleton (70) was an effective ligand for PA. Subsequently, based on the initial structure–activity relationship study, the fragment growth and fragment hybrid strategy were used to modify the pyromeconic acid backbone, and compounds 71 and 72 with good activity were obtained. Finally compound 73 with good inhibitory endonuclease activity (IC50 = 14 nmol/L, EC50 = 2.1 μmol/L, CC50 = 280 μmol/L) was obtained by combining the privileged substituents of 71 and 72 (Fig. 21).

Figure 21.

Schematic illustration of fragment-based discovery of PA endonuclease inhibitor.

4.4. Virtual screening

It is well known that virtual screening can be divided into two broad methods: structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) and ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS)62,122.

4.4.1. SBVS

Owing to the unique mode of action of PPI, it is challenging to identify inhibitors for several reasons123: the contact surface of PPI is generally large and flat so that it is difficult for small molecules to bind closely16; the chemical structures of PPI inhibitors and traditional drugs are very different, so it is difficult for traditional databases such as HTS to provide useful data for effective screening. Despite these challenges, many PPI inhibitors have been developed today. Importantly, most of the reported inhibitors of PA‒PB1 heterodimer were identified by SBVS35. Based on the SBVS, Muratore et al.85 screened almost 3 million molecules from the ZINC database using the C-terminal region of PA as a template. And to confirmed whether these small molecules could indeed inhibit the binding of PA and PB1, they developed an ELISA-based method to detect the specific inhibition of the interaction between PA and a PB1-derived peptide. In both enzymatic test and PRA test, compounds 74 and 75 showed promising antiviral activity. In particular, 74 showed antiviral activity against both influenza A and influenza B virus strains but was inactive against other RNA and DNA viruses, reflecting high selectivity. By modifying the difluoromethyl group or synthesizing polyamide analogues with similar chemical characteristics to obtain better compounds, 76 and 77 were identified, which showed approximately three times better activity compared to the lead compound 75. More encouragingly, the membrane permeability of 77 is significantly improved (Fig. 22)124.

Figure 22.

Schematic illustration of potent influenza inhibitors found by SBVS and LBVS.

4.4.2. LBVS

The PB2 subunit can combine with the m7G, which carries out the process of viral transcription. The crystal structure showed that the m7G part could interact with Lys376 of PB2 and form hydrogen bond interaction with Glu361. Therefore, the 7-methylguanine group and its analogues similar in structure to m7G can compete with natural ligands for the cap-binding domain of the PB2 subunit. Based on LBVS, Pautus et al.26 first identified 7-alkylguanine derivatives as effective inhibitors of the PB2 cap-binding domain. Structural analysis showed that the m7G structure of inhibitor was sandwiched between the two aromatic residues Phe404 and His357 with the binding mode similar to that of the PB2 subunit with the m7G. According to the favorable PB2 inhibitory activity of these derivatives, the researchers continually simulated the negative charge of triphosphate group and the carboxylic acid group of the m7G group to identified compounds 78–80, with IC50 values of 0.6–7.5 μmol/L (Fig. 22).

4.5. High-throughput screening

High-throughput screening could screen many sample libraries and find valuable information quickly, sensitively and accurately125. In 2015, Kakisaka et al.16 used HTS to screen a compound library of 9600 molecules against the H1N1 (A/WSN/33) virus. Compound 81 was selected and showed good antiviral activity against various influenza A viruses with IC50 value of 0.4–0.63 μmol/L. The researchers constructed a cell positioning system to study its mechanism and proved that it acted on a functional area composed of RNA binding groove, NP dimer interface, and nuclear export signal 3 (NES3) in the NP pocket, thereby inhibiting NP nuclear output process. In vivo experiments showed that the protection rate of 81 was 25% for mice infected with a lethal dose of H1N1 (A/WSN/33) at a dose of 10 mg/kg. In 2018, Huang et al.110 used the same screening method to find compound 82, which had an excellent antiviral effect on both H1N1 and H3N2 virus strains, with IC50 values of 0.41–1.41 μmol/L. Mechanism studies showed that this compound had a similar binding site to 81 and combined with the nuclear export signal domain and NP dimerization region to inhibit the interaction between NP‒RNA and NP‒NP, showed a strong inhibition on nuclear export function. In vivo test results indicated that 82 could effectively protect mice from influenza virus infection in vivo.

Recently, Sethy et al.111 carried out screening for 22,000 compounds and obtained a potent itaconic acid derivative 83 (EC50 = 2.84 μmol/L) against influenza A virus H1N1. Furthermore, 83 was modified to obtain compound 84 with an EC50 value of 0.14 μmol/L. It was shown that the antiviral mechanism of itaconic acid derivatives reduces virus replication by destroying influenza virus nucleoprotein and reducing the output of viral nucleoprotein from the nucleus117. White et al.108 used an ultra-high throughput screening method to find a specific inhibitor 85 of which EC50 is 27.43 μmol/L for H1N1 (A/California/04/2009). Mechanism studies had shown that 85 could induce NP to accumulate in the cytoplasm and block the nuclear export of vRNP. Compared with the oligomeric NP in the structure of vRNP, 85 had a higher affinity for monomeric NP. 86 was obtain by further optimization from 85, and it had an excellent inhibitory effect on influenza A and B viruses with EC50 of 1.43–15.15 μmol/L. In addition, the CC50 value of 86 was exceed 40 μmol/L, and it could show a synergistic antiviral effect with oseltamivir (Fig. 23).

Figure 23.

Discovery of highly potent and selective NP inhibitors via HTS approach.

5. Medicinal chemistry strategies in structure optimization of lead compounds targeting vRNP constituent proteins

5.1. Bioisosterism

Based on bioisosterism, a strategy for the rational design of new drugs in medicinal chemistry126, DuBois et al.19 analyzed several compounds, including marchatins, green tea catechins, and dihydroxy phenylphthalimides, that inhibit PAN endonuclease activity and influenza virus growth to obtain 2,3-dihydroxybenzoic acid (87) and its bioisosteres 88, 89 with PA endonuclease inhibitory activity (Fig. 24). The acetamido of 89 could combine with a highly conserved new pocket in PAN through hydrogen bonding.

Figure 24.

Discovery of potent PA inhibitor through bioisosterism strategy.

Clark et al.25 used phenotypic screen to identify a series of 3-pyrimidine nitrogen heterocyclic compounds as PB2 inhibitors. The EC50 values of these compounds were around 10 nmol/L. Among them, compound 90 exhibited the higher activity with an EC50 value of 0.51 μmol/L. The co-crystal structure indicated that the pyrimidine ring of 90 could form π-stacking with the Phe323 of PB2 cap-binding domain. Then researchers modified the structure of 90 through the bioisosterism strategy and introduced the isostere of the triphosphate negative electron group at the 4-position of the pyrimidine ring of 90 to obtain VX-787127. Moreover, the bioisosterism strategy had also been applied for the discovery of VX-787 analogues. For instance, Boyd et al.79 obtained compounds 91 and 92 that contained different carboxylic acid bioisosteres of VX-787, and they showed good antiviral activity in vitro enzymatic assays and in cell culture (Fig. 25).

Figure 25.

Discovery of highly potent PB2 cap-binding inhibitors by bioisosterism strategy.

Compound 52 (nucleozin) was a promising lead compound targeting NP. In 2012, Cheng et al.126 successfully designed a series of nucleozin analogues through bioisosterism and scaffold hopping strategies. Compared to hydroxyl, methyl, ethoxy or acetyl substituted groups, methoxy substituted compound 93 had the most potent activity, which could inhibit the replication of various H1N1 and H3N2 influenza A viruses with IC50 value equivalent to nucleozin. Simultaneously, its IC50 toward amantadine- and oseltamivir-resistant strains were both in the micromolar range (Fig. 26)128.

Figure 26.

Discovery of highly potent NP inhibitor through bioisosterism strategy.

5.2. Prodrug strategy

The above-mentioned EGCG showed good PA endonuclease inhibitory activity, but its cell membrane permeability was low and had poor chemical and metabolic stability. To further improve its drug-like properties, Mori et al.129 designed a series of fatty acid monoester derivatives through esterification. Although compounds 94a‒d displayed worse membrane permeability and higher cytotoxicity than EGCG, their antiviral activity and selectivity index were greatly improved (Fig. 27a).

Figure 27.

aOptimization of EGCG by prodrug strategy; bOptimization of baloxavir by prodrug strategy.

Baloxavir is another classic example benefiting from prodrug approach (Fig. 27b); as we known, compounds with metal-chelating groups usually suffered from low oral availability due to their low membrane permeability. In oral trials in mature rats and monkeys, the bioavailability of baloxavir acid was only 7.1%. Surprisingly, the prodrug strategy of esterification (BXM, 95) dramatically improved its bioavailability (F = 18.4%)130, as BXM could immediately metabolized to the active form of baloxavir acid in the intestinal lumen, epithelium, liver and blood, thereby exerted promising biological effects in the body of influenza virus-infected patients.

6. Conclusions and prospects

Nowadays, influenza viruses still constitute a significant public health threat globally, and the choice for treating them is limited due to the emergence of drug-resistant strains. It is extremely a huge challenge to eradicate the influenza virus as it has a strong ability to mutate and spread across species. Therefore, the development of anti-influenza drugs with novel mechanism of action is an emergency and needful task. The vRNP of the influenza virus is a potential antiviral target as it is essential for viral transcription and replication. Herein, we introduced the structure and functions of influenza virus vRNP and presents examples of various inhibitors targeting the functional proteins of vRNP in recent years. More important, these molecules could also be used in combination with conventional antiviral agents in order to reinforce the limited therapeutic arsenal against influenza virus infections.

The current antiviral research is mainly divided into two aspects: finding new targets for developing novel chemical entities and optimizing or designing antiviral drugs for existing targets. Traditional drug discovery is an expensive and time-consuming task. Fortunately, with the continuous development of pharmacophore models, structural biology and high-throughput screening, the process of inhibitor discovery of targeting resolved protein has been accelerated. Particularly, structure-based virtual screening can quickly and cost-effectively evaluate the interactions between compound libraries and drug targets. Many of the above examples have proved that the use of computational technologies to identify potential drug candidates could significantly reduce the time and cost. On the other hand, this review introduces some drug optimization strategies, such as structure-based optimization, bioisosterism, and prodrug approach. Of which structure-based optimization focuses on modifying a lead compound to increase affinity for a mutable target protein, improve the potency against resistant mutations, and probe biological chemical space, complementing existing therapies in the most likely case.

Of note, since the active catalytic sites of RdRp are highly conserved in various RNA viruses, those structures had become prime targets for the development of broad-spectrum antivirals. For example, favipiravir which was originally designed for the prevention and treatment of influenza through combining with the PB2 subunit of influenza virus RdRp, also showed favorable inhibition against SARS-CoV-2 in a randomized clinical trial131. Therefore, the research and development of broad-spectrum antivirals is particularly important especially in the face of unpredictable outbreaks. The various types of inhibitors described herein (especially for polymerase inhibitors) also have broad-spectrum antiviral potential and represent a potential arsenal in the fight against COVID-19. Therefore, governments, international organizations and foundations should finance and support broad-spectrum antivirals research and development targeting polymerase as part of pandemic preparedness plans132. Moreover, summarizing the discovery and optimization strategies of inhibitors drugs is very enlightening for us to deal with new virus outbreaks in the future. During the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, the strategy of “old dog, new trick” showed obvious timely advantages, which has also become a major tool in the current development of SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. After the species of the emerging virus has been identified, drugs that are effective against the known virus of that species can be tested for their inhibitory activity against the emerging virus. For example, many SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors have been found through the “privileged structure” repositioning approach such as remdesivir (hepatitis C virus polymerase inhibitor), which is the only one approved by FDA for treatment of COVID-19133; and suramin (could effectively inhibit the replication of many viruses including enteroviruses, Zika virus and Ebola viruses), which has the same anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity as remdesivir132. In a word, owing to the commonness of RNA viruses, the methods and strategies discussed in this paper are not only effective for influenza viruses, but also a good reference for other RNA viruses.

In summary, the vRNP of influenza virus is a powerful target for the design and development of anti-influenza drugs. And at present, some compounds with new structures, new targets and new mechanisms have entered the clinical trial stage and even have been on the market. It is expected to provide a strong guarantee for the prevention and treatment of influenza virus infection in the near future, and we hope more vRNP inhibitors with broad-spectrum antiviral potency could reach regulatory market approval to face multiple emergence/re-emergence of zoonotic viruses.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81773574, China), Science Foundation for Outstanding Young Scholars of Shandong Province (ZR2020JQ31, China), Foreign cultural and educational experts Project (GXL20200015001, China), Qilu Young Scholars Program of Shandong University and the Taishan Scholar Program at Shandong Province, Shandong Province Key Research and Development Project (No. 2019JZZY021011, China), Shandong Modern Agricultural Technology & Industry System (SDAIT-21-06 and SDAIT-11-01), Agricultural scientific and technological innovation project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CXGC2021A12, China), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, AIRC, grant No. IG18855 (to Arianna Loregian, Italy); British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, UK, BSAC-2018-0064 (to Arianna Loregian, Italy), Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca, PRIN 2017-cod. 2017KM79NN (to Arianna Loregian, Italy), Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo-Bando Ricerca COVID-2019 Nr. 55777 2020.0162 (to Arianna Loregian, Italy) are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Contributor Information

Bing Huang, Email: hbind@163.com.

Arianna Loregian, Email: arianna.loregian@unipd.it.

Xinyong Liu, Email: xinyongl@sdu.edu.cn.

Peng Zhan, Email: zhanpeng1982@sdu.edu.cn.

Author contributions

Lingxin Hou, Ying Zhang and Han Ju contributed equally as joint first authors. The writing-original draft preparation was initiated by Lingxin Hou and Ying Zhang. Peng Zhan and Han Ju provided constructive suggestions. Srinivasulu Cherukupalli, Ruifang Jia, Jian Zhang and Arianna Loregian edited and revised the manuscript. Bing Huang, Arianna Loregian and Peng Zhan and Xinyong Liu read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lee V.J., Ho Z.J.M., Goh E.H., Campbell H., Cohen C., Cozza V., et al. Advances in measuring influenza burden of disease. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018;12:3–9. doi: 10.1111/irv.12533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Principi N., Camilloni B., Alunno A., Polinori I., Argentiero A., Esposito S. Drugs for influenza treatment: is there significant news? Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:109. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J., Huang Y., Liu S. Investigational antiviral therapies for the treatment of influenza. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2019;28:481–488. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1606210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bright R.A., Medina M.J., Xu X., Perez-Oronoz G., Wallis T.R., Davis X.M., et al. Incidence of adamantane resistance among influenza A (H3N2) viruses isolated worldwide from 1994 to 2005: a cause for concern. Lancet. 2005;366:1175–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalily P.H., Duncan M.C., Fedida D., Wang J., Tietjen I. Put a cork in it: plugging the M2 viral ion channel to sink influenza. Antiviral Res. 2020;178:104780. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bright R.A., Shay D.K., Shu B., Cox N.J., Klimov A.I. Adamantane resistance among influenza A viruses isolated early during the 2005‒2006 influenza season in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295:891–894. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.8.joc60020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furuse Y., Suzuki A., Oshitani H. Large-scale sequence analysis of M gene of influenza A viruses from different species: mechanisms for emergence and spread of amantadine resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4457–4463. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00650-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang J., Li F., Ma C. Recent progress in designing inhibitors that target the drug-resistant M2 proton channels from the influenza A viruses. Biopolymers. 2015;104:291–309. doi: 10.1002/bip.22623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong G., Peng C., Luo J., Wang C., Han L., Wu B., et al. Adamantane-resistant influenza a viruses in the world (1902‒2013): frequency and distribution of M2 gene mutations. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naesens L., Stevaert A., Vanderlinden E. Antiviral therapies on the horizon for influenza. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;30:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lackenby A., Besselaar T.G., Daniels R.S., Fry A., Gregory V., Gubareva L.V., et al. Global update on the susceptibility of human influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors and status of novel antivirals, 2016‒2017. Antiviral Res. 2018;157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee N., Hurt A.C. Neuraminidase inhibitor resistance in influenza: a clinical perspective. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:520–526. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loregian A., Mercorelli B., Nannetti G., Compagnin C., Palù G. Antiviral strategies against influenza virus: towards new therapeutic approaches. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3659–3683. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1615-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin W.J., Seong B.L. Novel antiviral drug discovery strategies to tackle drug-resistant mutants of influenza virus strains. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2019;14:153–168. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2019.1560261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouvier N.M., Palese P. The biology of influenza viruses. Vaccine. 2008;26:D49–D53. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakisaka M., Sasaki Y., Yamada K., Kondoh Y., Hikono H., Osada H., et al. A novel antiviral target structure involved in the RNA binding, dimerization, and nuclear export functions of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Te-Velthuis A.J., Fodor E. Influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14:479–493. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song M.S., Kumar G., Shadrick W.R., Zhou W., Jeevan T., Li Z., et al. Identification and characterization of influenza variants resistant to a viral endonuclease inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3669–3674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519772113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuBois R.M., Slavish P.J., Baughman B.M., Yun M.K., Bao J., Webby R.J., et al. Structural and biochemical basis for development of influenza virus inhibitors targeting the PA endonuclease. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schully K.L., Berjohn C.M., Prouty A.M., Fitkariwala A., Som T., Sieng D., et al. Melioidosis in lower provincial Cambodia: a case series from a prospective study of sepsis in Takeo Province. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fodor E., Te Velthuis A.J.W. Structure and function of the influenza virus transcription and replication machinery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;10:a038398. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a038398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan P., Bartlam M., Lou Z., Chen S., Zhou J., He X., et al. Crystal structure of an avian influenza polymerase PA(N) reveals an endonuclease active site. Nature. 2009;458:909–913. doi: 10.1038/nature07720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dias A., Bouvier D., Crépin T., McCarthy A.A., Hart D.J., Baudin F., et al. The cap-snatching endonuclease of influenza virus polymerase resides in the PA subunit. Nature. 2009;458:914–918. doi: 10.1038/nature07745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crépin T., Dias A., Palencia A., Swale C., Cusack S., Ruigrok R.W. Mutational and metal binding analysis of the endonuclease domain of the influenza virus polymerase PA subunit. J Virol. 2010;84:9096–9104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00995-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark M.P., Ledeboer M.W., Davies I., Byrn R.A., Jones S.M., Perola E., et al. Discovery of a novel, first-in-class, orally bioavailable azaindole inhibitor (VX-787) of influenza PB2. J Med Chem. 2014;57:6668–6678. doi: 10.1021/jm5007275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pautus S., Sehr P., Lewis J., Fortuné A., Wolkerstorfer A., Szolar O., et al. New 7-methylguanine derivatives targeting the influenza polymerase PB2 cap-binding domain. J Med Chem. 2013;56:8915–8930. doi: 10.1021/jm401369y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reich S., Guilligay D., Cusack S. An in vitro fluorescence based study of initiation of RNA synthesis by influenza B polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3353–3368. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reich S., Guilligay D., Pflug A., Malet H., Berger I., Crépin T., et al. Structural insight into cap-snatching and RNA synthesis by influenza polymerase. Nature. 2014;516:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature14009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohtsu Y., Honda Y., Sakata Y., Kato H., Toyoda T. Fine mapping of the subunit binding sites of influenza virus RNA polymerase. Microbiol Immunol. 2002;46:167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sugiyama K., Obayashi E., Kawaguchi A., Suzuki Y., Tame J.R., Nagata K., et al. Structural insight into the essential PB1-PB2 subunit contact of the influenza virus RNA polymerase. Embo J. 2009;28:1803–1811. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He X., Zhou J., Bartlam M., Zhang R., Ma J., Lou Z., et al. Crystal structure of the polymerase PA(C)‒PB1(N) complex from an avian influenza H5N1 virus. Nature. 2008;454:1123–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature07120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obayashi E., Yoshida H., Kawai F., Shibayama N., Kawaguchi A., Nagata K., et al. The structural basis for an essential subunit interaction in influenza virus RNA polymerase. Nature. 2008;454:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature07225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massari S., Desantis J., Nizi M.G., Cecchetti V., Tabarrini O. Inhibition of influenza virus polymerase by interfering with its protein‒protein interactions. ACS Infect Dis. 2021;7:1332–1350. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yuan S., Chu H., Zhao H., Zhang K., Singh K., Chow B.K., et al. Identification of a small-molecule inhibitor of influenza virus via disrupting the subunits interaction of the viral polymerase. Antiviral Res. 2016;125:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massari S., Goracci L., Desantis J., Tabarrini O. Polymerase acidic protein-basic protein 1 (PA‒PB1) protein‒protein interaction as a target for next-generation anti-influenza therapeutics. J Med Chem. 2016;59:7699–7718. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H., Yao X. Molecular basis of the interaction for an essential subunit PA‒PB1 in influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights from molecular dynamics simulation and free energy calculation. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:75–85. doi: 10.1021/mp900131p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das K., Aramini J.M., Ma L.C., Krug R.M., Arnold E. Structures of influenza A proteins and insights into antiviral drug targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:530–538. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sasaki Y., Hagiwara K., Kakisaka M., Yamada K., Murakami T., Aida Y. Importin α3/Qip1 is involved in multiplication of mutant influenza virus with alanine mutation at amino acid 9 independently of nuclear transport function. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu Y., Sneyd H., Dekant R., Wang J. Influenza A virus nucleoprotein: a highly conserved multi-functional viral protein as a hot antiviral drug target. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17:2271–2285. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170224122508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kowalinski E., Zubieta C., Wolkerstorfer A., Szolar O.H., Ruigrok R.W., Cusack S. Structural analysis of specific metal chelating inhibitor binding to the endonuclease domain of influenza pH1N1 (2009) polymerase. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baughman B.M., Jake-Slavish P., DuBois R.M., Boyd V.A., White S.W., Webb T.R. Identification of influenza endonuclease inhibitors using a novel fluorescence polarization assay. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:526–534. doi: 10.1021/cb200439z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomassini J., Selnick H., Davies M.E., Armstrong M.E., Baldwin J., Bourgeois M., Hastings J., et al. Inhibition of cap (m7GpppXm)-dependent endonuclease of influenza virus by 4-substituted 2,4-dioxobutanoic acid compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2827–2837. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hastings J.C., Selnick H., Wolanski B., Tomassini J.E. Anti-influenza virus activities of 4-substituted 2,4-dioxobutanoic acid inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1304–1307. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakazawa M., Kadowaki S.E., Watanabe I., Kadowaki Y., Takei M., Fukuda H. PA subunit of RNA polymerase as a promising target for anti-influenza virus agents. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh S.B., Tomassini J.E. Synthesis of natural flutimide and analogous fully substituted pyrazine-2,6-diones, endonuclease inhibitors of influenza virus. J Org Chem. 2001;66:5504–5516. doi: 10.1021/jo015665d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parkes K.E., Ermert P., Fässler J., Ives J., Martin J.A., Merrett J.H., et al. Use of a pharmacophore model to discover a new class of influenza endonuclease inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1153–1164. doi: 10.1021/jm020334u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomassini J.E., Davies M.E., Hastings J.C., Lingham R., Mojena M., Raghoobar S.L., Singh S.B., et al. A novel antiviral agent which inhibits the endonuclease of influenza viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1189–1193. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauman J.D., Patel D., Baker S.F., Vijayan R.S., Xiang A., Parhi A.K., et al. Crystallographic fragment screening and structure-based optimization yields a new class of influenza endonuclease inhibitors. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:2501–2508. doi: 10.1021/cb400400j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sagong H.Y., Bauman J.D., Patel D., Das K., Arnold E., LaVoie E.J. Phenyl substituted 4-hydroxypyridazin-3(2H)-ones and 5-hydroxypyrimidin-4(3H)-ones: inhibitors of influenza A endonuclease. J Med Chem. 2014;57:8086–8098. doi: 10.1021/jm500958x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sagong H.Y., Bauman J.D., Nogales A., Martínez-Sobrido L., Arnold E., LaVoie E.J. Aryl and arylalkyl substituted 3-hydroxypyridin-2(1H)-ones: synthesis and evaluation as inhibitors of influenza A endonuclease. ChemMedChem. 2019;14:1204–1223. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201900084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parhi A.K., Xiang A., Bauman J.D., Patel D., Vijayan R.S., Das K., Arnold E., Lavoie E.J. Phenyl substituted 3-hydroxypyridin-2(1H)-ones: inhibitors of influenza A endonuclease. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21:6435–6446. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sagong H.Y., Parhi A., Bauman J.D., Patel D., Vijayan R.S., Das K., Arnold E., LaVoie E.J. 3-hydroxyquinolin-2(1H)-ones as inhibitors of influenza A endonuclease. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:547–550. doi: 10.1021/ml4001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuzuhara T., Iwai Y., Takahashi H., Hatakeyama D., Echigo N. Green tea catechins inhibit the endonuclease activity of influenza A virus RNA polymerase. PLoS Curr. 2009;1:Rrn1052. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iwai Y., Murakami K., Gomi Y., Hashimoto T., Asakawa Y., Okuno Y., et al. Anti-influenza activity of marchantins, macrocyclic bisbibenzyls contained in liverworts. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fudo S., Yamamoto N., Nukaga M., Odagiri T., Tashiro M., Neya S., et al. Structural and computational study on inhibitory compounds for endonuclease activity of influenza virus polymerase. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:5466–5475. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwai Y., Takahashi H., Hatakeyama D., Motoshima K., Ishikawa M., Sugita K., et al. Anti-influenza activity of phenethylphenylphthalimide analogs derived from thalidomide. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:5379–5390. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferro S., Gitto R., Buemi M.R., Karamanou S., Stevaert A., Naesens L., et al. Identification of influenza PA-Nter endonuclease inhibitors using pharmacophore- and docking-based virtual screening. Bioorg Med Chem. 2018;26:4544–4550. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liao Y., Ye Y., Li S., Zhuang Y., Chen L., Chen J., et al. Synthesis and SARs of dopamine derivatives as potential inhibitors of influenza virus PA(N) endonuclease. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;189:112048. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mifsud E.J., Hayden F.G., Hurt A.C. Antivirals targeting the polymerase complex of influenza viruses. Antiviral Res. 2019;169:104545. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heo Y.A. Baloxavir: first global approval. Drugs. 2018;78:693–697. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Noshi T., Kitano M., Taniguchi K., Yamamoto A., Omoto S., Baba K., et al. In vitro characterization of baloxavir acid, a first-in-class cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor of the influenza virus polymerase PA subunit. Antiviral Res. 2018;160:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones J.C., Marathe B.M., Vogel P., Gasser R., Najera I., Govorkova E.A. The PA endonuclease inhibitor RO-7 protects mice from lethal challenge with influenza A or B viruses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02460-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones J.C., Marathe B.M., Lerner C., Kreis L., Gasser R., Pascua P.N., et al. A novel endonuclease inhibitor exhibits broad-spectrum anti-influenza virus activity in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:5504–5514. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00888-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Omoto S., Speranzini V., Hashimoto T., Noshi T., Yamaguchi H., Kawai M., et al. Characterization of influenza virus variants induced by treatment with the endonuclease inhibitor baloxavir marboxil. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9633. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27890-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]