Abstract

Purpose

Isolation policies are long-term and strictly enforced in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social media might be widely used for communication, work, understanding the development of the epidemic, etc. However, these behaviors might lead to problematic social media use. The present study investigated the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use, as well as the internal mechanisms involved.

Methods

One thousand three hundred seventy-three Chinese college students (Mage = 19.53, SDage = 1.09) were recruited randomly from four grades who completed Coronavirus Stress Scale, Fear of Missing Out Scale, Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire, and Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale.

Results

Stressors of COVID-19 were positively related to problematic social media use. The link between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out. Additionally, the association between fear of missing out and problematic social media use, as well as the association between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use were moderated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Conclusion

The current findings reveal the mechanism that may be used to reduce the likelihood of problematic social media use in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. To prevent and intervene in problematic social media use during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study stressed the importance of decreasing the fear of missing out and enhancing regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Keywords: stressors of COVID-19, Chinese college students, problematic social media use, fear of missing out, regulatory emotional self-efficacy

Highlights

- Stressors of COVID-19 were positively related to smartphone problematic social media use.

- The effect of stressors of COVID-19 on smartphone problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out.

- The effect of fear of missing out on smartphone problematic social media use was moderated by regulation emotional self-efficacy. The effect of stressors of COVID-19 and smartphone problematic social media use was moderated by regulation emotional self-efficacy.

Introduction

COVID-19 has caused significant negative consequences for the global economy, culture, life and public health (1, 2). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, authorities implemented rigorous measures such as isolation to diminish infection rates (3, 4). Isolation policies that are long-term and strictly enforced may lead to significant changes in how adolescents engage socially (5, 6). Due to social distancing, smartphone social media use has increased for gathering epidemic information, studying, working, alleviating boredom, and social networking online (7, 8). Social media is an essential tool in daily life during the COVID-19 epidemic (9, 10).

However, excessive social media use can be harmful. There is a sense of withdrawal when the user temporarily leaves the online world (11, 12). Then, improper social media usage may increase the likelihood of addiction during the epidemic (13, 14). Since the classification of problematic Internet use is conceptually unclear, there is a lack of consensus among academics on the definition of problematic social media use (15, 16). In comparison, addiction-like symptoms and everyday life disruptions have been attributed to the use of social media which is characterized by “addiction-like” behavior and exacerbates disputes with family and friends (17, 18). Most scholars recognize that problematic social media use refers to individuals spending a significant amount of time on social media, resulting in impairment of the individual's social, physical and mental health (11, 19, 20). Increasing numbers of studies from various countries describe its potential negative consequences that cannot be ignored. For instance, researchers revealed that problematic use of social media was positively correlated with depression and insomnia (21). Furthermore, Al-Menayes (22) found that social media addiction harmed academic performance. Moreover, the research revealed that Facebook addiction predicted suicide ideation and behavior (23). Kaye (24) found that physical health was linked to excessive social media usage. As a result, although prior researchers have discovered the detrimental consequences of problematic social media use, little research was undertaken among Chinese college students during the epidemic, which is one of the study's focal focuses.

Stressors of COVID-19 and Problematic Social Media Use

Stress is caused by an inability to meet the multiple demands of one's environment, which may overwhelm an individual's capacity to adapt (25). Although keep social distancing played a very important role during the epidemic, it also negatively affected the individual's social activities. Due to the lack of effective medication for COVID-19, anxiety, and depression symptoms accompany a loss of control over an individual's daily activities (4, 26). Individuals suffered severe stress during COVID-19 (27, 28). Lazarus and Folkman distinguished two kinds of strategies in people's coping with stress: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping (29). One included an attempt to resolve the stress(itself)-causing the problem, while the other described people's attempts to manage the emotions that are prompted by stress. During the epidemic, people might obtain COVID-19 related information via social media with problem-focused coping strategies which could keep abreast of COVID-19 (8, 9). In addition, people might join online communities for social support to cope with their negative feelings caused by the pandemic (7, 30). Nevertheless, it's important to take into account the potentially harmful effects of problematic social media use through some online activities (17, 31). Previous researches showed the problematic use of SNS was favored by unmet need to belong and anxious attachment style (32, 33). Recent studies were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic which had found daily stress had a significant effect on addictive social media (12, 34, 35). Therefore, we proposed that Chinese college students who experienced higher stressors of COVID-19 might be at higher risk of problematic social media use.

The Mediation Effect of Fear of Missing Out

According to stress-coping strategies (29), college students are subjected to stressors of COVID-19, which may lead to an increase in problematic social media use. Simultaneously, other psychological variables may also have a significant influence on the relationship between stress and problematic social media use. Then, while examining the impacts of stressors of COVID-19, it is critical to examine the mediators that influence the emergence of problematic social media use. Fear of missing out is characterized as a constant fear that others may be enjoying gratifying experiences that one is not a part of, and the urge to keep up with what others are doing (36). The fear of missing out has grown ubiquitous in popular society (37, 38). Eighty-one percent of participants in recent research of 936 people from various socio-demographic backgrounds reported experiencing fear of missing out at least periodically (39). Previous studies have found that the association between negative factors and social media engagement was mediated by fear of missing out (36). Meanwhile, fear of missing out was an important risk factor for social media engagement (37, 40). Earlier researches addressed fear of missing out as a trait variable, but more academic work has examined the degree to which environmental signals, such as checking social media postings, might cause state- fear of missing out (41). When individuals utilize digital tools to keep track of tantalizing things on social media about desirable online activities, they may get state-fear of missing out (42, 43). In this study, the variable we investigate is the state- fear of missing out. In contrast to previous studies, our study focuses on determining how fear of missing out has evolved during the COVID-19 epidemic when individuals reduced their outside activities in favor of online activities. People keep social distance to prevent the spread of COVID-19, which is an effective measure. However, the unique features of COVID-19 make it an exceptional situation, with concomitant anxiety and depressive symptoms accompanied by a loss of social support (i.e., control over daily life and offline social interaction) (28, 44). With chronic psychological deficits, people are continually looking for updates through social media (9, 45). According to the social compensation theory (46), individuals seeking online support are motivated by a lack of offline social support. Previous researchers found that online social media could remind individuals that they might have missed otherwise (16, 43). During the epidemic, people mainly use smartphone social media to obtain information about the epidemic and conduct social activities to reduce negative emotions (27). With constant access to online social media, individuals increasingly expect and await feedback. Then, individuals are afraid of missing out on this instant information related to COVID-19 from authority and feedback from their friends (16, 42), which may lead to a higher level of fear of missing out during COVID-19. Fear of missing out includes unmet social needs and has symptoms of depression and anxiety (41, 42, 45). In conformity with the compensatory Internet use theory (47), when individuals experience negative events or emotions, they turn to the Internet to relieve these confusions, leading to Internet overuse. During the pandemic of COVID-19, pandemic-related social distancing and limiting public gatherings led to fewer socialization options. When people were under stressors, they often unconsciously unlocked their phones and used online social media (40, 48), which might increase problematic social media use (18, 35). As a result, stressors of COVID-19 are associated with an increased risk of problematic social media use in those who use social media to alleviate their fear of missing out on meeting their social support requirements. We hypothesized in this research that the association between stressors of COVID-19 and Chinese college students' problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out.

The Moderating Role of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy

A stressor will not have a detrimental effect on those with adequate coping resources, according to stress-coping strategies (16, 29, 49). To put it another way, a person's behavior is not just determined by the amount of stress they experience but also by how effectively they are able to manage that stress (50). Researchers found that the ability of stress-coping moderated the relationship between stressful life events and a wide range of developmental outcomes, including substance use, externalizing problems, and internalizing problems (51–53). During the epidemic, not all individuals who experience stressors of COVID-19 increase their fear of missing out and suffer from problematic social media use. The heterogeneity of outcomes may reflect individual characteristics (54) that moderate (i.e., protect) the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use. One such protective factor may be regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Regulatory emotional self-efficacy refers to a person's perceived degree of confidence in their capacity to manage emotions (55, 56). In accord with the self-efficacy theory (57), individuals only have the motivation to carry out the activity if they believe that the prospective result can be achieved. Previous studies have confirmed that regulatory emotional self-efficacy played a vital role in individuals' actual engagement in adaptive behavior (58, 59). Several previous findings have demonstrated that regulatory emotional self-efficacy was negatively related to addictive behavior, which plays a protective role (56–61).

The association between environmental risk factors and problem behaviors would be reduced by individual attributes such as regulatory emotional self-efficacy, in line with the “risk buffering hypothesis” (62–64). The hypothesis proposed that protective factors may mitigate the negative consequences of risk factors. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy may serve as a buffer in this study. As individuals feel more stress, psychological needs in their lives are not met, but individuals with higher levels of emotion management abilities leave individuals with lower needs for desired compensation which lead to less problematic social media use behaviors (65). Furthermore, as the fear of missing out rises, individuals in their lives are at a lower risk of tending to use mobile social media due to higher emotional management abilities (66). Then, potentially harmful results (problematic social media use) might be reduced by the combination of protective (regulatory emotional self-efficacy) and risk (stressors of COVID-19, fear of missing out) variables that interact. The “risk buffering hypothesis” is confirmed by empirical researches. For instance, Guo et al. (67) found that regulatory emotional self-efficacy played a moderated role in the association between parental psychological control and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury. Besides, the previous research also revealed that the link between emotional reactivity and suicide ideation was buffered by regulatory emotional self-efficacy (59). Meanwhile, Pan et al. (68) found that individuals with high levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy have a lower risk of Internet addiction. Taken together, we predicted that regulatory emotional self-efficacy moderated the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use, as well as the effect of fear of missing out on problematic social media use.

The Present Study

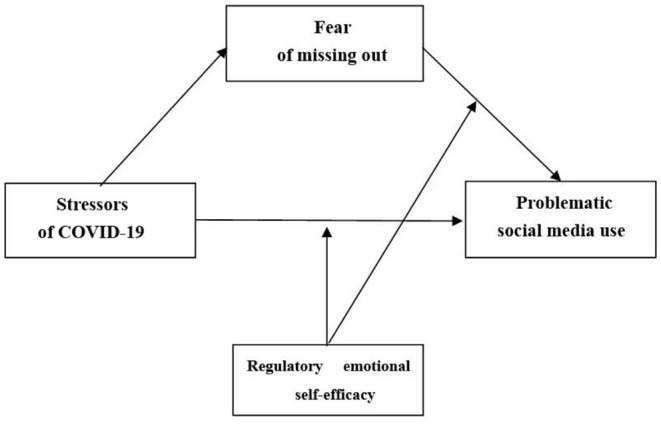

To summarize, we developed a moderated mediation model to address three questions: (a) whether stressors of COVID-19 would be linked with problematic social media use, (b)whether the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use would be mediated by fear of missing out, (c)whether regulatory emotional self-efficacy would moderate the effect of fear of missing out on problematic social media use as well as the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use. The moderated mediation model was outlined in Figure 1. We put forward three hypotheses:

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Hypothesis 1: Stressors of COVID-19 are positively correlated with problematic social media use.

Hypothesis 2: The effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use would be mediated by fear of missing out.

Hypothesis 3: The effect of fear of missing out on problematic social media use would be buffered by regulatory emotional self-efficacy. The effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use would be buffered by regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Method

Participants

One thousand four hundred two Chinese college students were recruited in China. The criteria for unqualified participants were <100 s to complete questionnaires with a total of 47 questions and regularity of answers, such as the same score in each item or a regular pattern of scores (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, etc.). After excluding unqualified samples (e.g., completed questionnaire <100 s and answered regularly), we finally collected 1,373 (Mage = 19.53, SDage = 1.09) valid questionnaires with an effective response rate of 97.93% from 1,402 primary questionnaires. The mean age ranges from 18 to 23 years. 56.67% of participants were females. Regarding their grades, 26.91% were freshmen, 21.15% were sophomores, 29.31% were junior students, and 22.63% were senior students.

Instruments

The Coronavirus Stress Scale

We used the 5-item Coronavirus Stress Scale (69) to measure individuals' perceived COVID-19 related stress. All items (e.g., How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life due to the COVID-19 pandemic?) were rated on a five-point scale (from 1 = never to 5 = very often). Applied to Chinese samples, the cultural adaption and reliability of the revised scale are well (70, 71), and the validity of the revised scale is well (71–73). The goodness of fit [CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.08, 90% CI = (0.07, 0.09)] of confirmatory factor analysis of the Coronavirus Stress Scale in this study indicated that fit indicators in accordance with the cutoffs recommended in the literature actually showed a satisfactory adequacy, indicating that the scale had good construct validity. In this study, Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.90.

Fear of Missing Out Scale

We used the 10-item Fear of Missing Out Scale (36) to assess the missing out on social events and spending time with friends. Each item (e.g., I fear that my friends have more rewarding experiences than me.) was rated on a five-point scale (from 1 = Not at all true of me” to “5 = Extremely true of me). Applied to Chinese samples, the cultural adaption and reliability of the revised scale are well (40, 74, 75), and the validity of the revised scale is well (74, 76). The goodness of fit [CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.08, 90% CI = (0.07, 0.09)] of confirmatory factor analysis of the Fear of Missing Out Scale in this study indicated that that fit indicators in accordance with the cutoffs recommended in the literature actually showed a satisfactory adequacy, indicating that the scale had good construct validity. In this study, Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.89.

Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire

We used the 20-item Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire (77) to evaluate problematic smartphone social media usage. All the items (e.g., If you are delayed in doing business due to using social networks, you often regret that you have lost your time by playing on your mobile phone.) were rated on a five-point scale (1 = never to 5 = very often). Applied to Chinese samples, the cultural adaption and reliability of the revised scale are well (20, 78, 79), and the validity of the revised scale is well (20, 80). The goodness of fit [CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.07, 90% CI = (0.06, 0.08)] of confirmatory factor analysis of the Problematic Mobile Social Media Usage Assessment Questionnaire in this study indicated that fit indicators in accordance with the cutoffs recommended in the literature actually showed a satisfactory adequacy, indicating that the scale had good construct validity. In our study, Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.89.

Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale

We used the 12-item Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale (55) to measure the individual's confidence in the ability to regulate their own emotions. Responses to each item (e.g., Keep from getting discouraged in the face of difficulties?) were rated on a five-point scale (1 = not well at all to 5 = very well). Applied to Chinese samples, the cultural adaption and reliability of the revised scale are well (59, 61, 67), and the validity of the revised scale is well (81, 82). The goodness of fit [CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.07, 90% CI = (0.06, 0.08)] of confirmatory factor analysis of the Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy Scale in this study indicated that fit indicators in accordance with the cutoffs recommended in the literature actually showed a satisfactory adequacy, indicating that the scale had good construct validity. In our study, Cronbach's α for the scale was 0.92.

Procedure

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the first author's University. Before data collection, participants' consent was acquired. Questionnaires were delivered online Internet to comply with the epidemic prevention policy. All replies were anonymous, and all questionnaires had detailed instructions. Participants were not compensated in any way for their involvement in the research.

Analytic Approach

The data obtained from the normality tests revealed that none of the research variables deviated significantly from normalcy (83) (i.e., Skewness < |3.0| and Kurtosis < |10.0|). This study used the methods for estimating multivariate normality which was explored in terms of calculating Mahalanobis distances and plotting them on a scattergram against derived chi-square values using Fortran and SPSS programs developed by Thompson (84). If the variables form a multivariate normal distribution, the points will form a straight line (85). The result indicated that that multivariate normality can be assumed. Descriptive statistics were the first to be computed. The PROCESS Models 4 and 15 macros for SPSS were used to analyze the mediation and moderated mediation models using 5,000 random sample bootstrapping confidence intervals (CIs). A thorough standardization procedure was followed before the data analysis.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation of the relevant variables are shown in Table 1. Stressors of COVID-19 were positively associated with fear of missing out and positively associated with problematic social media use. Fear of missing out was positively associated with problematic social media use. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy was negatively associated with problematic social media use. As expected, the findings were in line with Hypothesis 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for the main variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 19.53 | 1.09 | 1 | ||||

| 2. SOC | 2.49 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 1 | |||

| 3. FOMO | 2.41 | 0.88 | −0.04 | 0.53** | |||

| 4. PSMU | 2.39 | 0.87 | 0.02 | 0.57** | 0.75** | ||

| 5. RESE | 3.31 | 0.69 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.25 | −0.08** | 1 |

N = 1,373,

p < 0.01; SOC, Stressors of COVID-19; FOMO, Fear of missing out; PSMU, Problematic social media use; RESE, regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Testing the Mediating Role of Fearing of Missing Out

In the hypothesis, we anticipated that the association between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out. Model 4 of Hayes' SPSS macro PROCESS was used to test this hypothesis (86). Table 2 shows the results of the regression analysis conducted to test mediation. Specifically, stressors of COVID-19 were shown to be positively correlated with fear of missing out, β = 0.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.47, 0.57] and problematic social media use, β = 0.56, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.53, 0.61]. Stressors of COVID-19 had a positive residual direct effect on problematic social media use. The results demonstrated that the association between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out, indirect effect = 0.32, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.28, 0.37]. The mediated impact accounted for 57.13% of the overall effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use. Our hypothesis 2 was confirmed by the results.

Table 2.

Linear regression models.

| Predictors | Dependent variable (FOMO) | Dependent variable (PSMU) | Dependent variable (PSMU) | Dependent variable (PSMU) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | |

| Age | −0.11 | −4.74 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 2.30 | 0.03 | 2.23* |

| SOC | 0.52 | 23.02*** | 0.56 | 25.77*** | 0.24 | 12.11*** | 0.22 | 10.63*** |

| FOMO | 0.62 | 31.37*** | 0.66 | 30.38*** | ||||

| RESE | −0.05 | −2.53* | ||||||

| SOC × RESE | 0.04 | 2.55* | ||||||

| FOMO × RESE | −0.05 | −3.47*** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.61 | 0.62 | ||||

| F(df) | 186.97*** | 227.33*** | 538.88*** | 314.97*** | ||||

| (3, 1,369) | (3, 1,369) | (4, 1,368) | (7, 1,365) | |||||

N = 1,373;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.001; SOC, Stressors of COVID-19; FOMO, Fear of missing out; PSMU, Problematic social media use; RESE, regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Testing for Moderated Mediation

Model 15 in SPSS macro PROCESS was used to examine if regulatory emotional self-efficacy might moderate the direct link between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use, and the mediation effect of fear of missing out, as expected in this study (in particular, the association between problematic social media use and the fear of missing out). Table 2 shows the findings.

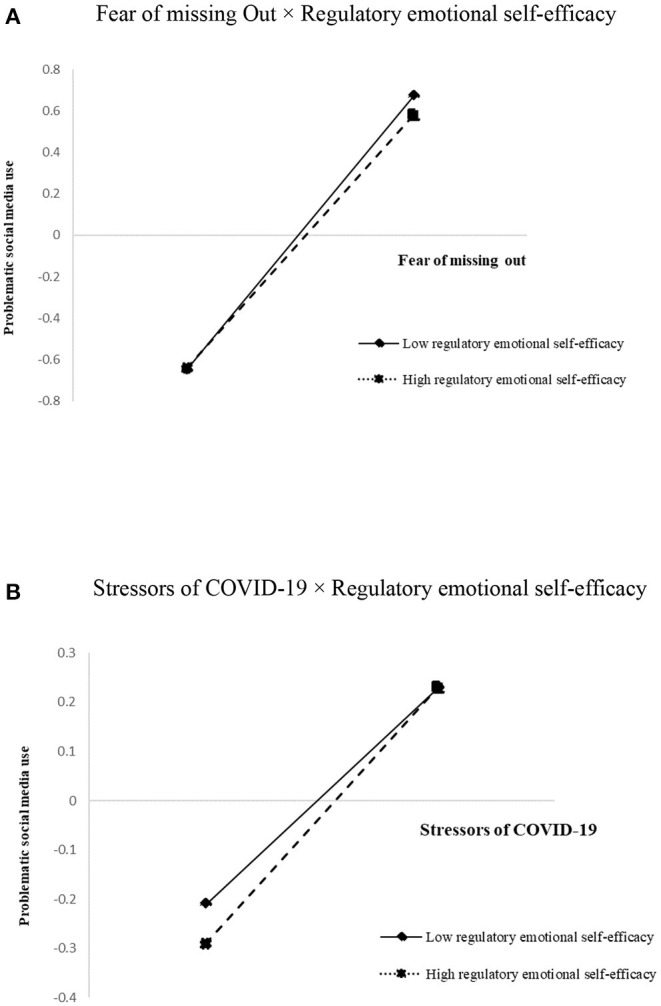

The analysis revealed that stressors of COVID-19 were linked to problematic social media use [β = 0.22, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.17, 0.26)], whereas the fear of missing out was linked to the problematic social media use [β = 0.66, p < 0.001, 95% CI (0.63, 0.71)]. Aside from that, the interaction of stressors of COVID-19 and regulatory emotional self-efficacy [β= 0.04, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.07]) for problematic social media use was found to be significant, as was the interaction of fear of missing out and regulatory emotional self-efficacy (β = −0.05, p < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.08, −0.02)] for problematic social media use. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy was shown to reduce the links between stresses of COVID-19 and fear of missing out on problematic social media use (i.e., the relationship with stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use, as well as the relationship between fear of missing out and problematic social media use, might be significantly moderated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy). Consequently, the postulated moderated mediating model was shown to be well.

Figure 2 depicts a graphic representation of the interaction effect. In college students with low regulatory emotional self-efficacy, fear of missing out was shown to be a strong effect on problematic social media use, as demonstrated by simple slope tests, bsimple = 0.71, t = 23.34, p < 0.001. Fear of missing out, on the other hand, was shown to be a significant effect on problematic social media use among college students who had high regulatory emotional self-efficacy, but the relationship was considerably weaker, bsimple = 0.61, t = 27.56, p < 0.001, showing a buffering impact of regulatory emotional self-efficacy (Figure 2A). Finally, in Figure 2B, the visual representation of the interaction effect is shown. The results of simple slope tests revealed that stressors of COVID-19 significantly affected problematic social media use in both college students with high and low levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy; however, for college students with high levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy, the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use was stronger (bsimple = 0.26, t = 11.76, p < 0.001) than college students with low levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy (bsimple = 0.18, t = 6.01, p < 0.001), demonstrating that regulatory emotional self-efficacy acted as a buffer in the opposite direction.

Figure 2.

The plot of the relationship between fear of missing out and problematic social media use at two levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy (A). The plot of the relationship between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use at two levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy (B). (A) Fear of missing Out × Regulatory emotional self-efficacy. (B) Stressors of COVID-19 × Regulatory emotional self-efficacy.

Further comparing the indirect effects, the difference between a high degree of regulatory emotional self-efficacy and a low degree of regulatory emotional self-efficacy also reached a significant level [Index of moderated mediation, Index = – 0.028, 95% CI = (−0.06, −0.02)], indicating the degree of regulatory emotional self-efficacy weakens the indirect effects of fear of missing out between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use. The indirect effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use via fear of missing out was further moderated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy, according to the bias-corrected percentile bootstrap analysis. The indirect impact of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media usage through fear of missing out was particularly significant for college students with low levels of regulatory emotional self-efficacy, β = 0.37, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.33, 0.43]. The indirect effect was likewise significant for college students who had strong refusal self-efficacy, but was lower for those who had weak refusal self-efficacy, β = 0.32, SE = 0.02, 95%CI = [0.27, 0.37]. As a result of the findings, hypothesis 3 was supported by all two moderating routes shown in Figure 1.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the effects of stressors of COVID-19 on Chinese college students' problematic social media use. The results suggested that stressors of COVID-19 were positively related to problematic social media use. Furthermore, the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use was mediated by fear of missing out. The effect of fear of missing out on problematic social media use was moderated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy, as well as the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use. Then, we had a clear grasp of how and when stressors related to COVID-19 were associated with problematic social media use.

The findings revealed that stressors of COVID-19 were closely correlated with problematic social media use. It meant that college students who experienced a higher level of stressors of COVID-19 were more likely to engage in problematic social media behavior. The result was consistent with the general strain theory (87), which proposes that different types of stress cause individuals' negative experiences that ultimately lead to problematic behaviors. During the epidemic, effects of the absence of specific drugs for COVID-19 and the reduction in social interaction due to keeping a social distance (4) predispose individuals to develop negative emotions (26). As epidemic prevention measures were strictly enforced, access to social interactions decreased and mobile phone use increased (64), with the consequently increased availability of mobile social media use (16, 44). Through the use of social media, individuals were able to obtain positive social feedback and momentarily forget about negative emotions (21, 88). Therefore, such a process increased the risk of problematic social media use.

The Mediation Role of Fear of Missing Out

Our study showed that fear of missing out mediated the association between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use. Then, in light of stressors of COVID-19, fear of missing out might be one of the explaining mechanisms for why some individuals are more prone to raise problematic social media use.

In the mediation process of the relationship between stressors of COVID-19 and the fear of missing out, stressors of COVID-19 have raised the fear of missing out among college students, which is consistent with social compensation theory (46). Individuals with high levels of stressors of COVID-19 are more likely to use social media to access positive psychological experiences that are not available in the context of isolation (16, 89). Individuals pay more attention to the information in the network with higher stressors of COVID-19 (14, 34, 90), and are more worried about missing important information about themselves or others in social media (42). In the mediation process of the relationship between fear of missing out and problematic social media use, college students with higher fear of missing out are more likely to exhibit problematic social media use. This finding of the study conforms with the compensatory Internet use theory (47). A previous study found that individuals with a higher level of fear of missing out required the psychological need to stay informed and avoid missing out on the experiences, thoughts, and experiences of others (91). This psychological need is greatly satisfied through the use of smartphone social media (1), and this psychological comfort also creates a sense of physical excitement in the individual (92), which can easily lead to social media overuse (45, 93).

The Moderation of Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy

The association between fear of missing out and problematic social media use was moderated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy as well as the association between stressors of COVID-19 and problematic social media use. There are two different types of protection: risk-buffering and reverse risk-buffering (94). Regulatory emotional self-efficacy functioned as a buffer to the effect of college students' fear of missing out on problematic social media use. Fear of missing out on problematic social media use is mitigated by regulatory emotional self-efficacy. During the pandemic, individuals with high regulatory emotional self-efficacy are less likely to resort to problematic social media use for psychological satisfaction. The reason is that they can successfully manage their emotions (66) even when they are experiencing high fear of missing out. Individuals with high regulatory emotional self-efficacy, even if they suffer anxiety, fear, and other emotions, are more confident to deal with these negative emotions (95, 96). Therefore, our study results suggest that examining the “risk buffering hypothesis” (62) is crucial to understanding how college students' problematic social media use is impacted by the stressors of COVID-19.

In contrast, the effect of stressors of COVID-19 on smartphone problematic social media use is stronger for college students with high regulatory emotional self-efficacy than for those with a low level of regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Accordingly, the benefits of regulatory emotional self-efficacy are negated in the presence of high stressors of COVID-19 based on our findings. Stressors of COVID-19 can induce negative emotions (1), and the anonymity, convenience, and escapist nature of smartphone social media can provide individuals with relief and escape from these negative emotions (13, 97), prompting individuals to use mobile social media to cope with stress. People who have high regulatory emotional self-efficacy are more confident in their abilities, so they may appear to overrate themselves and tend to fall into blind optimism, and overestimate their abilities (55, 98, 99) that is typical of overconfidence (100, 101). Overconfidence among college students may lead to cognitive biases such as “superiority,” the illusion of control, and over-optimism in smartphone use. Thus, if college students with high regulatory emotional self-efficacy who are under a high level of stressors of COVID-19 overestimate their sense of control when using their smartphones or underestimate the negative consequences of excessive smartphone social media use, regulatory emotional self-efficacy may aggravate their smartphone problematic social media use. The risk mitigation capacity of the protective factor may deteriorate when risk variables rise to an excessive degree. The result is in line with the protective-limiting hypothesis (杯水车薪) (102). The hypothesis proposed that in the presence of a high-risk factor, the preventive effects of the protective factor are diminished. Researchers have sufficiently supported the protective-limiting hypothesis in explaining the moderating effect (64, 103–105).

Implication and Limitations

The results of this study have implications for both theory and practice. Theoretically, as a follow-up to prior research, this study emphasized the mediating function served by fear of missing out, as well as the moderating role played by regulatory emotional self-efficacy amid the epidemic, respectively. The effect of stressors of COVID-19 on college students' smartphone problematic social media use was little explored before the outbreak of COVID-19. Social compensation theory, compensatory Internet use theory, and self-efficacy theory are all supported by this study's findings, which give empirical proof to the prior research. Practically, in the context of the epidemic, our findings have crucial implications for preventing and intervening with smartphone problematic social media use among college students. College students are at an important period in their academic, cognitive and physical, and mental development. They are more emotionally sensitive and vulnerable to stressful life events (106). colleges and families should provide measures to increase the satisfaction of their needs. For example, the college could carry out various activities, cultivate good interests and hobbies, increases social channels, etc., so that college students could meet their own needs. College students could face up to and accept their emotions and reinterpret the significance of events in some epidemic situations. With the reduction of negative emotions caused by stressors of COVID-19, it is possible to reduce the risk of problematic social media use.

There are certain limits to the current research that should be mentioned. Firstly, a cross-sectional design was used, which makes it impossible to infer causality in this study. Future studies may use experimental and longitudinal methods to further clarify causality. Secondly, response bias may have influenced the findings in this investigation, as in any study that relied only on self-reported data for data collection. Future research may attempt to gather data from a broad number of informants to further explore the existing results. Thirdly, the sample is not very heterogenous regarding age. To draw even more generalizable conclusions, the findings need be reproduced with additional, more inclusive or even representative samples. Fourthly, we introduce the idea of online social support as a way to compensate social isolation when fear of missing out is presented. This would be a more conceptual robust option, and researchers may look into more protective factors such as emotional regulation self-efficacy, rather than only risk factors such as fear of missing out in the future study.

Conclusion

In sum, fear of missing out is an important mediating component in the assessment of the effect mechanism of stressors of COVID-19 on problematic social media use, as shown by this study. It is recommended that future research take this variable into account more thoroughly. Moreover, regulation emotional self-efficacy is not always a defender of protective variables and a buffer against the risk factors. A lot of things need to be done for college students to get help which includes mental health courses, individual and group psychological counseling, as well as improving their emotion management skills so that college students couldn't use social media problematically.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary files, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JZ: writing—original draft. BY: supervision and project administration. LY and JZ: investigation and writing—review and editing. LY and BY: resources. FX: revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Jiangxi University Party Construction Research Project (20DJQN020), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72164018), National Social Science Fund Project (BFA200065), Jiangxi Social Science Foundation Project (21JY13), Jiangxi' Key Research Base Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (JD20068), and Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi' Department of Education (GJJ200306).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank all of the participants and volunteers.

References

- 1.Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (Covid-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput Hum Behav. (2021) 119:106720. 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karakose T. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on higher education: Opportunities and implications for policy and practice. Educ Proc Int J. (2021) 10:7–12. 10.22521/edupij.2021.101.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellewell J, Abbott S, Gimma A, Bosse NI, Jarvis CI, Russell TW, et al. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob Health. (2020) 8:e488–96. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World health organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. (2020) 76:71–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brem A, Viardot E, Nylund PA. Implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for innovation: which technologies will improve our lives? Technol Forecast Soc Change. (2021) 163:120451. 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant RM, Lurie N. Social media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus. J Am Med Assoc. (2020) 323:2011–12. 10.1001/jama.2020.4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaya T. The changes in the effects of social media use of cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol Soc. (2020) 63:101380. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong A, Ho S, Olusanya O, Antonini MV, Lyness D. The use of social media and online communications in times of pandemic COVID-19. J Intensive Care Soc. (2020) 22:255–60. 10.1177/1751143720966280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahni H, Sharma H. Role of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic: beneficial, destructive, or reconstructive? Int J Acad Med. (2020) 6:70–5. 10.4103/IJAM.IJAM_50_20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiederhold BK. Using social media to our advantage: alleviating anxiety during a pandemic. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:197–8. 10.1089/cyber.2020.29180.bkw [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banyai F, Zsila A, Kiraly O, Maraz A, Elekes Z, Griffiths MD, et al. Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0169839. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao X, Masood A, Luqman A, Ali A. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 85:163–74. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brailovskaia J, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene I, Kazlauskas E, Margraf J. The patterns of problematic social media use (SMU) and their relationship with online flow, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in lithuania and in Germany. Curr Psychol. (2021) 40:1–12. 10.1007/s12144-021-01711-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gómez-Galán J, Martínez-López JÁ, Lázaro-Pérez C, Sarasola Sánchez-Serrano JL. Social networks consumption and addiction in college students during the COVID-19 ppandemic: educational approach to responsible use. Sustainability. (2020) 12:7737. 10.3390/su12187737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreassen CS, Torsheim T, Brunborg GS, Pallesen S. Development of a facebook addiction scale. Psychol Rep. (2012) 110:501–17. 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao N, Zhou G. COVID-19 stress and addictive social media use (SMU): mediating role of active use and social media flow. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:635546. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andreassen CS, Pallesen S, Griffiths MD. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: findings from a large national survey. Addict Behav. (2017) 64:287–93. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leung L. Predicting internet risks: a longitudinal panel study of gratifications-sought, internet addiction symptoms, and social media use among children and adolescents. Health Psychol Behav Med. (2014) 2:424–39. 10.1080/21642850.2014.902316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffiths M. A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. J Subst Use. (2005) 10:191–7. 10.1080/14659890500114359 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang Y. Problematic social media usage and anxiety among University students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of psychological capital and the moderating role of academic burnout. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:76. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.612007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff HW, Margraf J, Köllner V. Relationships between addictive facebook use, depressiveness, insomnia, and positive mental health in an inpatient sample: a german longitudinal study. J Behav Addict. (2019) 8:703–13. 10.1556/2006.8.2019.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Menayes JJ. Social media use, engagement and addiction as predictors of academic performance. Int J Psychol Stud. (2015) 7:86–94. 10.5539/ijps.v7n4p86 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brailovskaia J, Teismann T, Margraf J. Positive mental health mediates the relationship between facebook addiction disorder and suicide-related outcomes: a longitudinal approach. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. (2020) 23:346–50. 10.1089/cyber.2019.0563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye A. Facebook use and negative behavioral and mental health outcomes: a literature review. J Addict Res Ther. (2019) 10:1–10. 10.4172/2155-6105.1000375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus RS. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1988) 54:486–95. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID stress syndrome: concept, structure, and correlates. Depress Anxiety. (2020) 37:706–714. 10.1002/da.23071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brailovskaia J, Ozimek P, Bierhoff HW. How to prevent side effects of social media use (SMU)? Relationship between daily stress, online social support, physical activity and addictive tendencies – a longitudinal approach before and during the first Covid-19 lockdown in Germany. J Affect Disord Rep. (2021) 5:100144. 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gritsenko V, Skugarevsky O, Konstantinov V, Khamenka N, Marinova T, Reznik A, et al. COVID 19 fear, stress, anxiety, and substance use among russian and belarusian University students. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 19:2362–8. 10.1007/s11469-020-00330-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer publishing company; (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Indian M, Grieve R. When facebook is easier than face-to-face: social support derived from facebook in socially anxious individuals. Pers Individ Dif. (2014) 59:102–6. 10.1016/j.paid.2013.11.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Twenge JM, Joiner TE, Rogers ML, Martin GN. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin Psychol Sci. (2017) 6:3–17. 10.1177/2167702617723376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D'Arienzo MC, Boursier V, Griffiths MD. Addiction to social media and attachment styles: a systematic literature review. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2019) 17:1094–118. 10.1007/s11469-019-00082-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stănculescu E, Griffiths MD. Anxious attachment and facebook addiction: the mediating role of need to belong, self-esteem, and facebook use to meet romantic partners. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2021) 19:1–17. 10.1007/s11469-021-00598-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brailovskaia J, Rohmann E, Bierhoff HW, Schillack H, Margraf J. The relationship between daily stress, social support and facebook addiction disorder. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 276:167–74. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Longstreet P, Brooks S. Life satisfaction: a key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technol Soc. (2017) 50:73–7. 10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Przybylski AK, Murayama K, DeHaan CR, Gladwell V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput Hum Behav. (2013) 29:1841–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.02.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elhai JD, Yang H, Montag C. Fear of missing out (FOMO): overview, theoretical underpinnings, and literature review on relations with severity of negative affectivity and problematic technology use. Braz J Psychiatry. (2021) 43:203–9. 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayran C, Anik L. Well-being and fear of missing out on digital content in the time of COVID-19: a correlational analysis among University students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:1974. 10.3390/ijerph18041974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayran C, Anik L, Gürhan-Canli Z. A threat to loyalty: fear of missing out (FOMO) leads to reluctance to repeat current experiences. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0232318. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang H, Liu B, Fang J. Stress and problematic smartphone use severity: smartphone use frequency and fear of missing out as mediators. Front Psychiatry. (2021) 12:594. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.659288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wegmann E, Oberst U, Stodt B, Brand M. Online-specific fear of missing out and internet-use expectancies contribute to symptoms of internet-communication disorder. Addict Behav Rep. (2017) 5:33–42. 10.1016/j.abrep.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dempsey AE, O'Brien KD, Tiamiyu MF, Elhai JD. Fear of missing out (FoMO) and rumination mediate relations between social anxiety and problematic facebook use. Addict Behav Rep. (2019) 9:100150. 10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milyavskaya M, Saffran M, Hope N, Koestner R. Fear of missing out: prevalence, dynamics, and consequences of experiencing FOMO. Motiv Emot. (2018) 42:725–37. 10.1007/s11031-018-9683-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brailovskaia J, Margraf J. Predicting adaptive and maladaptive responses to the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a prospective longitudinal study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. (2020) 20:183–91. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oberst U, Wegmann E, Stodt B, Brand M, Chamarro A. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: the mediating role of fear of missing out. J Adolesc. (2017) 55:51–60. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zell AL, Moeller L. Are you happy for me … on facebook? The potential importance of “likes” and comments. Comput Hum Behav. (2018) 78:26–33. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kardefelt-Winther D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput Hum Behav. (2014) 31:351–4. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De-Sola Gutiérrez J, Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Rubio G. Cell-phone addiction: a review. Front Psychiatry. (2016) 7:175. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carver CS, Vargas S. Stress, Coping, and Health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; (2011). 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lazarus RS. Emotions and interpersonal relationships: toward a person-centered conceptualization of emotions and coping. J Pers. (2006) 74:9–46. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00368.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzales NA, Tein JY, Sandler IN, Friedman RJ. On the limits of coping: interaction between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. J Adolesc Res. (2001) 16:372–95. 10.1177/0743558401164005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraaij V, Garnefski N, de Wilde EJ, Dijkstra A, Gebhardt W, Maes S, et al. Negative life events and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: bonding and cognitive coping as vulnerability factors? J Youth Adolesc. (2003) 32:185–93. 10.1023/A:1022543419747 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vera EM, Vacek K, Coyle LD, Stinson J, Mull M, Doud K, et al. An examination of culturally relevant stressors, coping, ethnic identity, and subjective well-being in urban, ethnic minority adolescents. Prof Sch Counsel. (2011) 15:2156759X1101500203. 10.1177/2156759X1101500203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li D, Zhang W, Li X, Zhou Y, Zhao L, Wang Y. Stressful life events and adolescent internet addiction: the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction and the moderating role of coping style. Comput Hum Behav. (2016) 63:408–15. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caprara GV, Di Giunta L, Eisenberg N, Gerbino M, Pastorelli C, Tramontano C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol Assess. (2008) 20:227–37. 10.1037/1040-3590.20.3.227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pauletto M, Grassi M, Passolunghi MC, Penolazzi B. Psychological well-being in childhood: the role of trait emotional intelligence, regulatory emotional self-efficacy, coping and general intelligence. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2021) 26:1284–97. 10.1177/13591045211040681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bandura A, Freeman WH, Lightsey R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; (1999). 10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bigman YE, Mauss IB, Gross JJ, Tamir M. Yes I can: expected success promotes actual success in emotion regulation. Cogn Emot. (2016) 30:1380–7. 10.1080/02699931.2015.1067188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu S, You J, Ying J, Li X, Shi Q. Emotion reactivity, nonsuicidal self-injury, and regulatory emotional self-efficacy: a moderated mediation model of suicide ideation. J Affect Disord. (2020) 266:82–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang C, Zhou Y, Cao Q, Xia M, An J. The relationship between self-control and self-efficacy among patients with substance use disorders: resilience and self-esteem as mediators. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 10:388. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan M, Guo X, Li X, Chen X, Wang C, Li Y. The moderating role of regulatory emotional self-efficacy on smoking craving: an ecological momentary assessment study. Psychol J. (2018) 7:5–12. 10.1002/pchj.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luthar SS, Grossman EJ, Small PJ. Resilience and Adversity. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; (2015). 10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao J, Ye B, Luo L, Yu L. The effect of parent phubbing on Chinese adolescents' smartphone addiction during COVID-19 pandemic: testing a moderated mediation model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2022) 15:569–79. 10.2147/PRBM.S349105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao J, Ye B, Yu L. Peer phubbing and Chinese college students' smartphone addiction during COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of boredom proneness and the moderating role of refusal self-efficacy. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2021) 14:1725–36. 10.2147/PRBM.S335407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rouis S, Limayem M, Salehi-Sangari E. Impact of facebook usage on students academic achievement: role of self-regulation and trust. Electro J Res Educ Psychol. (2011) 9:961–94. 10.25115/ejrep.v9i25.1465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Calandri E, Graziano F, Rollé L. Social media, depressive symptoms and well-being in early adolescence: the moderating role of emotional self-efficacy and gender. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:660740. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.660740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Guo J, Gao Q, Wu R, Ying J, You J. Parental psychological control, parent-related loneliness, depressive symptoms, and regulatory emotional self-efficacy: a moderated serial mediation model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Arch Suicide Res. (2021) 29:1–16. 10.1080/13811118.2021.1922109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan CC, Wang LF, Chen D, Chen C, Ge LL. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy and internet addiction among college students. Mod Prevent Med. (2014) 2013:18.35421953 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arslan G, Yildirim M, Tanhan A, Bulus M, Allen KA. Coronavirus stress, optimism-pessimism, psychological inflexibility, and psychological health: psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure. Int J Ment Health Addict. (2020) 19:1–17. 10.1007/s11469-020-00337-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu Y, Ye B, Tan J. Stress of COVID-19, anxiety, economic insecurity, and mental health literacy: a structural equation modeling approach. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:4856. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.707079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ye B, Wang R, Liu M, Wang X, Yang Q. Life history strategy and overeating during COVID-19 pandemic: a moderated mediation model of sense of control and coronavirus stress. J Eat Disord. (2021) 9:158. 10.1186/s40337-021-00514-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York, NY: Guilford publications; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mulaik SA. Linear Causal Modeling With Structural Equations. Chapman and Hall/CRC; (2009). 10.1201/9781439800393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Elhai JD, Yang H, Fang J, Bai X, Hall BJ. Depression and anxiety symptoms are related to problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese young adults: fear of missing out as a mediator. Addict Behav. (2020) 101:105962. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xie X, Wang Y, Wang P, Zhao F, Lei L. Basic psychological needs satisfaction and fear of missing out: friend support moderated the mediating effect of individual relative deprivation. Psychiatry Res. (2018) 268:223–8. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geng J, Lei L, Ouyang M, Nie J, Wang P. The influence of perceived parental phubbing on adolescents' problematic smartphone use: a two-wave multiple mediation model. Addict Behav. (2021) 121:106995. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jiang Y. Development of problematic mobile social media usage assessment questionnaire for adolescents. Psychol Tech Applic. (2018) 6:613–21. 10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2018.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bai J, Mo K, Peng Y, Hao W, Qu Y, Lei X, et al. The relationship between the use of mobile social media and subjective well-being: the mediating effect of boredom proneness. Front Psychol. (2021) 11:3824. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.568492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang X, Zhao S, Zhang MX, Chen F, Chang L. Life history strategies and problematic use of short-form video applications. Evol Psychol Sci. (2021) 7:39–44. 10.1007/s40806-020-00255-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu J, Ahmed MZ, Ahmed O, Griffiths MD, Chen L. Development and psychometric assessment of the problematic QQ use scale among adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:6744. 10.3390/ijerph18136744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X, Zhang Y, Hui Z, Bai W, Terry PD, Ma M, et al. The mediating effect of regulatory emotional self-efficacy on the association between self-esteem and school bullying in middle school students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:991. 10.3390/ijerph15050991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yuan G, Xu W, Liu Z, Liu C, Li W, An Y. Dispositional mindfulness, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and academic burnout in Chinese adolescents following a tornado: the role of mediation through regulatory emotional self-efficacy. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. (2018) 27:487–504. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1433258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thompson B. Multinor: a fortran program that assists in evaluating multivariate normality. Educ Psychol Meas. (1990) 50:845–8. 10.1177/0013164490504014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nor AW. The graphical assessment of multivariate normality using SPSS. Educ Med J. (2015) 7:71–5. 10.5959/eimj.v7i2.361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford publications; (2017) [Google Scholar]

- 87.Agnew R, White HR. An empirical test of general strain theory. Criminology. (1992) 30:475–500. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01113.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Seo J, Lee CS, Lee YJ, Bhang SY, Lee D. The type of daily life stressors associated with social media use in adolescents with problematic internet/smartphone use. Psychiatry Investig. (2021) 18:241–8. 10.30773/pi.2020.0060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Grieve R, Kemp N, Norris K, Padgett CR. Push or pull? Unpacking the social compensation hypothesis of Internet use in an educational context. Comput Educ. (2017) 109:1–10. 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.02.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang C, Zhou Z. Passive social network site use, social anxiety, rumination and depression in adolescents. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2018) 26:490–3. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Butt AK, Arshad T. The relationship between basic psychological needs and phubbing: fear of missing out as the mediator. Psychol J. (2021) 10:916–25. 10.1002/pchj.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Parker BJ, Plank RE. A uses and gratifications perspective on the internet as a new information source. Am Bus Rev. (2000) 18:43 [Google Scholar]

- 93.Franchina V, Vanden Abeele M, van Rooij AJ, Lo Coco G, De Marez L. Fear of missing out as a predictor of problematic social media use and phubbing behavior among flemish adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:2319. 10.3390/ijerph15102319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fang J, Wang W, Gao L., Yang J, Wang X, Wang P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: a moderated mediation model of callous—unemotional traits and perceived social support. J Interpers Viol. (2020) 37:NP5026–49. 10.1177/0886260520960106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang F, Guo F, Ding Q, Hong J. Social anxiety and mobile phone addition in college students: the influence of cognitive failure and regulatory emotional self-efficacy. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2021) 29:56–9. 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wartberg L, Thomasius R, Paschke K. The relevance of emotion regulation, procrastination, and perceived stress for problematic social media use in a representative sample of children and adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. (2021) 121:106788. 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106788 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hawk ST, van den Eijnden RJJM, van Lissa CJ, ter Bogt TFM. Narcissistic adolescents' attention-seeking following social rejection: links with social media disclosure, problematic social media use, smartphone stress. Comput Hum Behav. (2019) 92:65–75. 10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gao B, Zhu S, Wu J. The relationship between mobile phone addiction and learningengagement in college students: the mediating effect of self-control and moderating effect of core self-evaluation. Psychol Dev Educ. (2021) 37:400–6. 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2021.03.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Judge TA. Core self-evaluations and work success. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. (2009) 18:58–62. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01606.x18642988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Moore DA, Healy PJ. The trouble with overconfidence. Psychol Rev. (2008) 115:502–17. 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shen Z, Dong Y, Yu G. The theoretical model of differential information in overconfidentce. J Psychol Sci. (2009) 32:1405–7. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2009.06.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li D, Zhang W, Li X, Li N, Ye B. Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among chinese adolescents: direct, mediated, moderated effects. J Adolesc. (2012) 35:55–66. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang Q, Xiao T, Liu HY, Hu W. The relationship between parental rejection and internet addiction in left-behind children: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Dev Educ. (2019) 35:749–58. 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2019.06.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Y, Li D, Sun W, Zhao L, Lai X, Zhou Y. Parent-child attachment and prosocial behavior among junior high school students: moderated mediation effect. Acta Psychol Sin. (2017) 49:663–79. 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ye B, Yang Q, Hu Z. Effect of gratitude on adolescents' academic achievement: moderated mediating effect. Psychol Dev Educ. (2013) 29:192–9. 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2013.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiol Rev. (2008) 30:133–54. 10.1093/epirev/mxn002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary files, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.