Abstract

Trichophyton rubrum is one of the major disease causing pathogens in human; mainly it causes tinea pedis, tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cytochrome P450 which considered to be an important protein that can impact ergosterol biosynthesis pathway. B. aegyptiaca is rich source of secondary metabolites with tremendous medicinal values and it has sweet pulp, leaves with spine, strong seed and oily kernel. The epicarp of the fruit was taken for this study to inhibit T. rubrum using in vitro and in silico techniques. The epicarp portion was extracted using various solvents and water. The anti-dermatophytic activity on T. rubrum of these extracts was assessed utilizing poison plate technique with 5 individual concentrations. The fractioned chloroform extract of epicarp had fully inhibited the growth of T. rubrum at 3 mg/ml. Further, the chloroform extract was subjected to LC-MS analysis, in total, 40 compounds were elucidated. Then, the derived compounds were included for predicting ADMETox properties using Qikprop module. From the analysis 40 compounds were identified to be eligible for docking process. Then the desirable compounds, drug Ketoconazole were subjected to docking analysis using Glide module of Schrödinger. It shows that Platyphylloside has better docking result than other compounds and drug Ketoconazole. Further, MD simulation was carried out for Ketoconazole-Cyp450 and Platyphylloside-CYP450 complexes using Desmond, Schrödinger. MD simulation study also confirmed that the Platyphylloside-CYP450 complex more stable. This study suggests that Platyphylloside may act as potential inhibitor and it could be further subjected to experimental analysis to inhibit the T. rubrum growth.

Keywords: Balanites aegyptiaca, Trichophyton rubrum, CYP450, Platyphylloside, MD simulation

Abbreviations: B.aegyptiaca, Balanites aegyptiaca; T.rubrum, Tricgophyton rubrum; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; ADME-Tox, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity

1. Introduction

Dermatophytoses or Tinea are a type of skin infections in human and other living organisms caused by group of filamentous pathogenic fungi called Dermatophytes (Behzadi et al., 2014, Kaul et al., 2017). Microsporum, Trichophyton, Epidermophyton cause dermatophytoses by digesting the keratin of the host by producing keratinases and it grows in keratinized tissues like skin, hair, nail, feathers, hooves and horns (Burmester et al., 2011, Navone and Speight, 2018).

Trichophyton rubrum is anthropophilic in nature. It is the predominant disease causing agent accounting for 69.5% followed by other species of Trichophyton (Bristow and Spruce, 2009). Most commonly T. rubrum causes the infections in the area of feet, groin, hands and scalp throughout the world (Blutfield et al., 2015). Protein Lanosterol 14α-demethylase encrypted by the gene CYP51, is the most conserved protein in the CYP (CYP450) superfamily and it has more specificity. CYP450s have concerned in various biological processes, together with production of basic and secondary products in the pathogen (Lamb et al., 2007).

All azole drugs have the same function of inhibiting the protein Cytochrome P450 14α-demethylase. The azoles like Ketoconazole, Itraconazole, Fluconazole have the great capacity to inhibit the growth of dermatophytes especially T. rubrum (Ghannoum, 2016). Major steroid of fungal cell membrane exists in ergosterol that regulates fungal natural functions such as fluidness and integrity (Martinez-Rossi et al., 2008). Blocking of ergosterol biosynthesis and accumulation of other sterols on cell membrane lead to increased membrane rigidity and permeability, interrupt membrane-bound enzymes, pathogen growth inhibition and finally cell death (Zhang et al., 2007, Parker et al., 2014).

According to WHO, 75% of complete population happen treating their ailment accompanying herbs and other ancient beneficial methods (Balakumar et al., 2011). Medicinal plants exist a fashionable supply of secondary metabolites and are terribly helpful in treating varied diseases that ends up in new drug researches (Shakya, 2016). B. aegyptiaca bears potential medicative values and is employed as herbaceous medicine. The fruit has 4 layers, (i) Epicarp or outer layer, ripened fruit has crispy outer layer, (ii) Mesocarp or fleshy, sticky fruit pulp which is also known as desert date, (iii) Endocarp or woody shell, it is stone like very strong, (iv) inner seed or kernel (Al-Thobaiti and Zeid, 2018). It is used as purgative and to treat jaundice, diabetes (El-Nagerbi et al., 2013), whooping cough, dysentery, leukoderma, constipation, skin and liver diseases (Pandit et al., 1996, Kamal, 1998), it has potent antihelmintic, fish poison and antifungal activities (Archibald, 1933; Abdallah et al., 2012).

This study focuses on the antidermatophytic activity of epicarp of B. aegyptiaca by inhibiting the progress of Trichophyton rubrum using experimental studies, distinguishing compounds from the extract with terrible vital activity through LC-MS, docking and MD simulation analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant collection

The plant was subjected to diagnosis and edible part of vegetative growth developed after flowering was collected from the Nilambur area which is located 15 km distance from the Coimbatore city, Tamil Nadu, India. Then, the plant was authenticated with the aid of Botanical survey of India, Coimbatore (BSI/SRC/5/23/2018/Tech.1582). Further, the plant was washed well and the epicarp portion was separated from fruit pulp region, then shade drying, grinding and sequential extraction were done using the various solvents like Petroleum ether (PE), Hexane (HEX), Chloroform (CHL), Ethyl acetate (EA), Methanol fraction (MET), Aqueous fraction (WAT), Methanol (DMET) and Water (DWAT).

2.2. Fungal culture

The fungal culture MTCC.8477, Trichophyton rubrum was received from the MTCC (Microbial Type Culture Collection and GENE Bank), Chandigarh for this work.

2.3. Antifungal assay

Poison food assay (Grover and Moore, 1962) was used to assess the antidermatophytic action of various extracts of epicarp on T. rubrum. Various concentrations (1–5 mg/ml) of epicarp extracts were prepared and mixed with SDA medium, control plate without extract and positive control with Ketoconazole were prepared. The development of mycelia of T. rubrum was analysed every day. After 21 days of incubation the pathogen inhibitory percentage (I) was measured using the below formula stated below,.

Experiments were carried out in triplicates. The results were expressed as the mean ± standard error (SE). Data were analyzed statistically using SPSS software version 20.

2.4. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

Two fold broth dilution methods were followed in line with tips of NCCLS for filamentous fungi (M38-A2) for examining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC). 21 days old culture of T. rubrum was used for preparing the inoculum and spore suspension with 0.1 to 1.5 × 106 CFU/mL was designed for MIC (Nascente et al., 2009).

The concentrations of 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78, 0.39, 0.19 and 0.1 mg/ml were prepared, the MIC90 was noticed to reach 90% of inhibition during seven days of incubation at 30 °C.

2.5. Phytochemical analysis

Phytochemical screening process was carried out using fractioned chloroform extract of fruit epicarp using different experiments aimed at analyzing the existence of phytochemicals such as carbohydrates, proteins, amino acids, tannins, saponins, phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, coumarins, glycosides and emodins (Harborne, 1998, Edoga et al., 2005, Kokate et al., 2006).

2.6. Compound analysis

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to detect the macromolecules and secondary metabolites which were extent in the fractionated chloroform extract of fruit epicarp. LC-MS analysis was carried out using UPLC-QToF-MS system (Taamalli et al., 2015). Elucidated mass of compounds from LC-MS were equated with GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) database (Wang et al., 2016).

2.7. Protein – Homology modeling, refinement and confirmation

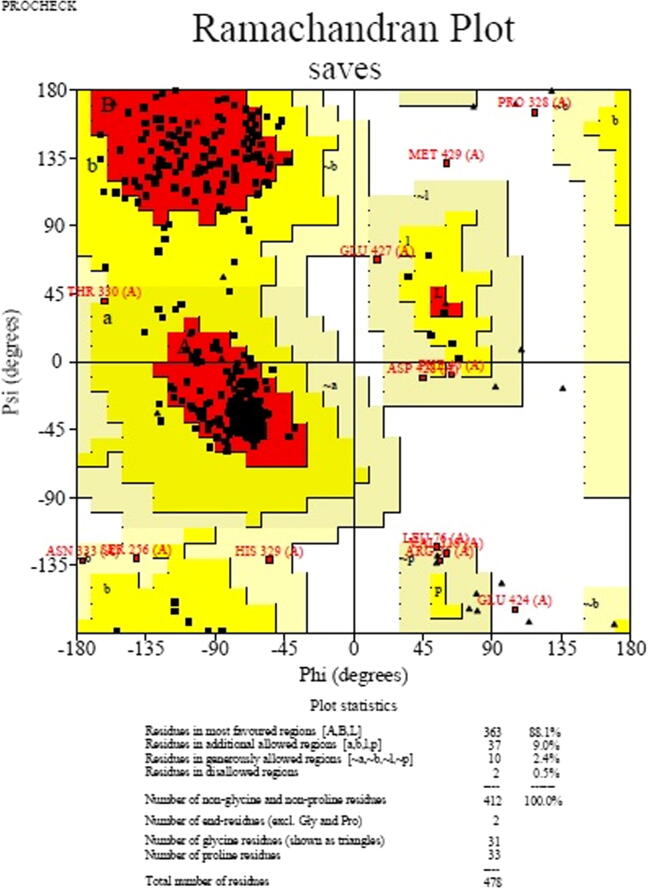

The crystal structure of CYP450 of T. rubrum was not obtainable in PDB. Hence, BLAST search carried out for finding suitable templates for modeling using NCBI-BLAST. Templates identified for CYP450 of T. rubrum with more than 40% similarities (5FRB), hence protein was modeled by homology modeling using Schrödinger. The loops of designed protein were refined and energy was reduced by ModRefiner for which algorithm is employed for atomic level, high resolution protein structure refinement (Xu and Zhang, 2011). Finally, modeled protein quality was confirmed utilizing the Ramachandran plot study by PROCHECK server (Laskowski et al., 1993).

2.8. Protein active site prediction

Active site identified by compared with existing crystal structures of identical protein from Candida species utilizing diversified sequence lining up method by Clustal Omega server (Sievers and Higgins, 2017).

2.9. Ligand preparation

The crystal structure of drug Ketoconazole and compounds which are elucidated from the fruit epicarp were downloaded in Pubchem. Further, these compounds were alloted for ADME-Tox examination utilzing QikProp component (Zhang et al., 2021). The various attributes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity were analysed for each compound (Sabitha and Vijayalakshmi, 2012).

2.10. Molecular docking

GLIDE module of Schrödinger was used to perform protein–ligand docking (Castro-Alvarez et al, 2017). The molecular docking was executed through the procedures of protein generation, receptor grid formation, ligand generation and ligand docking.

Protein preparation phase was initiated with protein preprocessing by increasing hydrogen atoms, improvement of amino acid orientation of hydroxyl groups, amide groups, creating disulfide bonds. Energy minimization process was performed with OPLS3e force field, non-hydrogen atoms were decreased till the common Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) reached standard value of 0.3 Å.

Grid was surrounded for the residues of Cytochrome P450 active site region. The drug and ligand molecules were prepared by optimization process using the OPLS3e force field.

Finally, the ligand docking was implemented using XP (extra precision) process (Chen et al., 2016) by adding the derived output files of ligand preparation and grid generation.

2.11. Molecular dynamics simulation

The Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation process was performed for an extent of time of 10 ns with Desmond module of Schrödinger for checking the stability of the docked complex structures of Ketoconazole-CYP450 and Platyphylloside -CYP450.

The simulation process was started with Protein preparation wizard for optimizing and minimizing the complex structure using OPLS3e force field. Further, the minimized structure was built by system builder using TIP3P solvent model, orthorhombic box shape with minimized volume and permitting 10 Å of buffer region. Then ions were added and the system was neutralized by adding necessary positive (Na+) and negative (Cl−) ions and 0.15 M salt was added. The system was minimized for 2000 iterations on a convergence threshold of 1 kcal/mol/Å and pre-equilibrated by using the inbuilt relaxation protocol (Aier et al., 2016).

Further modeled system was loaded and the Molecular Dynamics simulation run was administered up to 10 ns with recording interval of every 100 ps for total energy. For system equilibration the NPT ensembles were utilized and temperature maintained at 300 K (Gaonkar et al., 2020).

Further result was analyzed by using the parameters like Protein-Ligand RMSD, protein RMSF, ligand RMSF, Protein-ligand contacts which includes various types of interactions like hydrogen bond interactions were the important to analyze for obtaining the stability of the complex.

3. Results

3.1. Antifungal assay

The various extracts of epicarp of Balanites aegyptiaca was composed and their antidermatophytic activity (Fig. 1) was assessed (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Antidermatophytic activity of various extracts of fruit epicarp on T. rubrum.

Table 1.

Effect of fruit epicarp of B. aegyptiaca on radial growth of Trichophyton rubrum.

| Conc. mg/ml | PE | HEX | CHL | EA | MET | WAT | DMET | DWAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28.33 ± 0.88 | 25.33 ± 0.66 | 18 ± 0.00 | 24 ± 0.00 | 30 ± 0.00 | 10.66 ± 0.66 | 10.66 ± 0.66 | 20.00 ± 0.00 |

| 2 | 22.00 ± 1.15 | 17.00 ± 0.57 | 12.33 ± 0.33 | 21 ± 0.57 | 21 ± 0.57 | 8.33 ± 0.33 | 8.33 ± 0.33 | 17.33 ± 0.66 |

| 3 | 16.00 ± 0.00 | 10.33 ± 0.33 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 13.33 ± 0.66 | 18 ± 0.00 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | 11.66 ± 0.33 |

| 4 | 13.33 ± 0.66 | 6.00 ± 0.00 | – | 10.33 ± 0.88 | 11.66 ± 0.33 | 4.00 ± 0.00 | – | 10.00 ± 0.00 |

| 5 | 10.66 ± 0.33 | 2.00 ± 0.00 | – | 6.66 ± 0.66 | 7.33 ± 0.66 | – | – | 8.00 ± 0.00 |

Radial growth expressed as Mean ± S.E.

Values are calculated using Bonferroni test and they are significant (P < 0.05).

Upon reviewing the top of results, it had been detected that the mycelial growth of T. rubrum was completely suppressed by fractionated CHL extract from 4 mg/ml (Fig. 2), aqueous fraction extract completely inhibited by 5 mg/ml and methanol (DMET) extract was 4 mg/ml. As, CHL fraction of fruit epicarp was found to possess higher activity, additional study was primarily centered on the CHL fraction of fruit epicarp.

Fig. 2.

Anti-dermatophytic activity of fractioned chloroform extract of B. aegyptiaca epicarp on T. rubrum C – control, D – DMSO, K – Ketoconazole, 1 – 1 mg/ml, 2 – 2 mg/ml, 3 – 3 mg/ml, 4 – 4 mg/ml, 5 – 5 mg/ml.

3.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

After incubation period, the MIC90 was ascertained because 90% of inhibition was firm wherever no visible growth was detected. The MIC90 for CHL extract of fruit epicarp on T. rubrum was 3.12 mg/ml (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

MIC of fractioned Chloroform extract on T. rubrum.

3.3. Phytochemical screening

From the result of phytochemical analysis, the chloroform extract of fruit epicarp contains carbohydrates, proteins, flavonoids, phenols, alkaloids, terpenoids, steroids and saponins (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phytochemical analysis of fractioned chloroform extract of B. aegypptiaca fruit epicarp.

| S. no | Groups | Name of the test | Presence/absence* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Proteins and Amino acids | 1.Biuret Test 2.Ninhydrin Test |

+ + |

| 2. | Carbohydrates | 1.Benedict’s Test 2.Fehling’s Test |

+ + |

| 3. | Flavonoids | Alkaline reagent test | + |

| 4. | Phenols | Ferric chloride Test | + |

| 5. | Tannins | Ferric chloride test | – |

| 6. | Alkaloids | Mayer’s Test | + |

| 7. | Terpenoids | Salkowiski’s test | + |

| 8. | Steroids | Liebermann Burchard test | + |

| 9. | Saponins | Froth Test | + |

| 10. | Anthraquinones Glycosides | Borntrager’s test | – |

| 11. | Coumarins | Coumarin Test | – |

| 12. | Emodins | Emodin test | – |

(+) – Presence (−) – Absence.

3.4. LC-MS study

LC-MS evaluation of both positive and negative mode with distinct retention time (Fig. 4) showed that totally 41 compounds have been elucidated from fractioned chloroform extract of fruit epicarp (Table 3). For identifying the compound, the mass value of LC-MS derived compounds were compared with GNPS (Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking) database.

Fig. 4.

Chromatogram of LC-MS evaluation of fractioned chloroform extract of fruit epicarp with both positive (above) and negative (below) mode.

Table 3.

LC-MS derived compounds from fractioned chloroform extract of epicarp of Balanites aegyptiaca.

| S. no | Compound name | Mass from LC-MS | Original mass (GNPS) | Chemical formula | Ion mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Theobromine | 180.08 | 180.0647 | C7H8N4O2 | + |

| 2. | N-Acetyl Phenylalanine | 207.08 | 207.0895 | C11H13NO3 | + |

| 3. | Aerugine | 209.11 | 209.0510 | C9H15N5O | + |

| 4. | N-Acetyl-D-Galactosamine | 221.11 | 221.0899 | C8H15NO6 | + |

| 5. | Forchlorfenurone | 247.07 | 247.0512 | C12H10ClN3O | + |

| 6. | 3-[(E)-2-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)vinyl]-5-methoxyphenol | 242.16 | 242.0943 | C15H14O3 | + |

| 7. | p-Coumaric acid | 164.19 | 164.0473 | C9H8O3 | + |

| 8. | 7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,5-diol | 242.10 | 242.0943 | C15H14O3 | + |

| 9. | N ∼ 5 ∼ -Carbamoyl-N ∼ 2∼-(phenylacetyl)ornithine | 293.08 | 293.1376 | C14H19N3O4 | + |

| 10. | Glucosaminate | 195.10 | 195.0743 | C6H13NO6 | + |

| 11. | Caffeate | 180.05 | 180.0423 | C9H8O4 | + |

| 12. | Phenylalanine | 164.09 | 165.0790 | C9H11NO2 | + |

| 13. | Lycorine | 287.09 | 287.1158 | C16H17NO4 | + |

| 14. | Paraxanthine | 180.09 | 180.0647 | C7H8N4O2 | + |

| 15. | Adenosine | 267.10 | 267.0968 | C10H13N5O4 | + |

| 16. | N-methylaurotetanine | 341.13 | 341.1627 | C20H23NO4 | + |

| 17. | 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one | 437.11 | 436.1006 | C20H20O11 | + |

| 18. | N-[2-(4-sec-Butyl-phenoxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3-yl]-acetamide | 353.20 | 353.1838 | C18H27NO6 | + |

| 19. | Allocryptopine | 369.45 | 369.1576 | C21H23NO5 | + |

| 20. | Pentaleno[1,6a-c]pyran-9-carboxylic acid, 1,3,4,5,6,7,7a,9a-octahydro-4,6,6-trimethyl-3-oxo-, (4S,4aR,7aS,9aR)- | 264.14 | 264.1362 | C15H20O4 | + |

| 21. | 2-[5-[2-[2-[5-(2-oxopropyl)oxolan-2-yl]propanoyloxy]butyl]oxolan-2-yl]propanoic acid | 398.26 | 398.2305 | C21H34O7 | + |

| 22. | Deoxycytidine | 227.11 | 227.0906 | C9H13N3O4 | – |

| 23. | Pulvinic acid | 308.12 | 308.0410 | C18H12O5 | – |

| 24. | 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-6-(2-phenylethyl)benzoic acid | 341.13 | 340.1675 | C21H24O4 | – |

| 25. | Divaricatinic acid | 211.08 | 210.0892 | C11H14O4 | – |

| 26. | Cortisol | 362.20 | 362.2093 | C21H30O5 | – |

| 27. | Norepanorin | 421.15 | 421.1525 | C24H23NO6 | – |

| 28. | 5-Chlorodivaricatinic acid | 245.12 | 244.0502 | C11H13ClO4 | – |

| 29. | Citreorosein | 285.11 | 286.0477 | C15H10O6 | – |

| 30. | 5-hydroxy-7-[4-hydroxy-2-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)phenyl]-2,2-dimethyl-7,8-dihydropyrano[3,2-g]chromen-6-one | 437.11 | 436.1886 | C26H28O6 | – |

| 31. | 2-{[6-O-(beta-D-Glucopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy}-2-phenylacetamide | 475.29 | 475.1690 | C20H29NO12 | – |

| 32. | Tetradecanoic acid | 228.11 | 228.2089 | C14H28O2 | – |

| 33. | Hexadecanoic acid | 256.17 | 256.2402 | C16H32O2 | – |

| 34. | Platyphylloside | 476.19 | 476.2050 | C25H32O9 | – |

| 35. | (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl 6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside | 481.22 | 480.2571 | C22H40O11 | – |

| 36. | N-Acetyl Neuraminate | 309.12 | 309.1060 | C11H19NO9 | – |

| 37. | 11-eicosenoic acid | 311.16 | 310.2872 | C20H38O2 | – |

| 38. | 4-[(2-{[(2-Ethyl-2,3-dihydroxybutanoyl)oxy]methyl}phenyl)amino]-4-oxobutanoic acid | 353.20 | 353.1475 | C17H23NO7 | – |

| 39. | Thelephoric acid | 351.19 | 352.0219 | C18H8O8 | – |

| 40. | (3S,5S,8R,9S,10S,13R,14S,17R)-3-[(2R,3R,4S,5R,6S)-3,4-dihydroxy-6-methyl-5-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxyoxan-2-yl]oxy-5,14-dihydroxy-13-methyl-17-(6-oxopyran-3-yl)-2,3,4,6,7,8,9,11,12,15,16,17-dodecahydro-1H-cyclopenta[a]phenanthrene-10-carbaldehyde | 724.46 | 724.3305 | C36H52O15 | – |

3.5. ADME-Tox analysis

3D structures of 40 compounds were downloaded from the Pubchem database. The ADME-Tox (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity) result showed that all the compounds expected inside the range of all the limits, thus these compounds were incorporated for molecular docking studies (Supp. Table 1).

3.6. Modeling and validation

Protein 3D-structure of Cytochrome P450 of T. rubrum was modeled using the templates 5FRB with 62% similarity by homology modeling method. The modeled protein (Fig. 5) was further validated and the result showed that 88.1% residues were present in most favored region (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

3D structure of Modeled Cytochrome P450 protein.

Fig. 6.

Ramachandran plot analysis of modeled Cytochrome P450 protein.

3.7. Active site prediction

The sequence of Cytochrome P450 protein of T.rubrum was aligned with the experimentally solved fungal target of Candida species and predicted active site residues were highlighted in Fig. 7. From this analysis, Tyr 106, Tyr 120, Lys 131, His 365 and Arg 369 were perceived as the active site residues of CYP450 protein in T. rubrum.

Fig. 7.

Predicting active site residues of CYP450 protein using multiple sequence alignment.

3.8. Molecular docking

The 40 compounds and the drug Ketoconazole were docked with the Cytochrome P450 protein of T. rubrum using XP (Extra Precision) docking. Analysis of docked complex structures revealed the compounds Platyphylloside, (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl-6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside and 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one had top ranked compounds with interactions to the active site residues and 20 compounds had good dock score than Ketoconazole (Table 4).

Table 4.

Docking result of drug Ketoconazole and LC-MS compounds from epicarp of B. aegyptiaca with Cytochrome P450 protein.

| S. no | Compound name | Dock score (kcal/mol) | Interacting residues | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoconazole | −7.6 | Tyr 52, Tyr 120, His 369 | 1.96, 1.80, 2.16 | |

| 1. | Platyphylloside | −13.2 | Tyr 106, Lys 131, Pro 447, Phe 448, His 453(2), Phe 496 | 5.39, 1.82, 1.78, 2.24, 1.84, 2.17, 5.48 |

| 2. | (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl 6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside | −12.6 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120, His 365, Ser 366, Tyr 492 | 2.03, 2.36, 1.95, 1.63, 1.714 |

| 3. | 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one | −11.7 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120, Lys 131, His 453 | 4.28, 1.79, 2.16, 1.88 |

| 4. | 2-{[6-O-(beta-D-Glucopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy}-2-phenylacetamide | −11.2 | Pro 447(2), Phe 448, His 453, Ile 464 | 2.05,2.31, 1.94, 2.07, 2.03 |

| 5. | 5-hydroxy-7-[4-hydroxy-2-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)phenyl]-2,2-dimethyl-7,8-dihydropyrano[3,2-g]chromen-6-one | −10.5 | – | – |

| 6. | 4-[(2-{[(2-Ethyl-2,3-dihydroxybutanoyl)oxy]methyl}phenyl)amino]-4-oxobutanoic acid | −10.1 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120, Ser 366(2), Arg 389, Phe 496 | 2.10, 2.15, 1.63, 2.44, 2.34, 5.37 |

| 7. | N-[2-(4-sec-Butyl-phenoxy)-4,5-dihydroxy-6-hydroxymethyl-tetrahydro-pyran-3-yl]-acetamide | −10.0 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120, His 453(2) | 5.02, 2.29, 1.71, 1.75 |

| 8. | Cortisol | −9.9 | Tyr 106, Ser 366 | 2.49, 2.13 |

| 9. | 2-[5-[2-[2-[5-(2-oxopropyl)oxolan-2-yl]propanoyloxy]butyl]oxolan-2-yl]propanoic acid | −9.2 | Tyr 106, Arg 369 | 2.17, 2.78 |

| 10. | Thelephoric acid | −9.0 | Leu 495 | 1.94 |

| 11. | Citreorosein | −8.8 | Tyr 106, Ser 366 | 2.09, 1.72 |

| 12. | 7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,5-diol | −8.4 | Tyr 106, Ser 366 | 4.09, 1.84 |

| 13. | 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-6-(2-phenylethyl)benzoic acid | −8.2 | Tyr 120, His 453(2) | 1.98, 1.75, 2.72 |

| 14. | Lycorine | −8.2 | Tyr 106, Ser 366, Leu 495 | 4.28, 2.00, 2.42 |

| 15. | 3-[(E)-2-(3-Hydroxyphenyl)vinyl]-5-methoxyphenol | −8.2 | Tyr 120, Leu 495 | 1.94, 1.74 |

| 16. | 11-eicosenoic acid | −8.1 | Tyr 120, His 453 | 1.81, 1.94 |

| 17. | Norepanorin | −8.1 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120 | 4.03, 2.09 |

| 18. | Deoxycytidine | −7.9 | Tyr 106(2), Ser 366 | 2.10, 5.37, 1.69 |

| 19. | Pentaleno[1,6a-c]pyran-9-carboxylic acid, 1,3,4,5,6,7,7a,9a-octahydro-4,6,6-trimethyl-3-oxo-, (4S,4aR,7aS,9aR) | −7.7 | Arg 369 | 4.57 |

| 20. | N-Acetylneuraminate | −7.7 | Ser 366, Leu 495 | 1.75, 1.89 |

| 21. | N-methylaurotetanine | −7.5 | His 453, Phe 496 | 2.03, 5.36 |

| 22. | Forchlorfenuron | −7.2 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120(2) | 5.33, 2.16, 2.20 |

| 23. | N-Acetyl Phenylalanine | −7.1 | Tyr 106 | 1.83 |

| 24. | Allocryptopine | −7.0 | – | – |

| 25. | Caffeate | −6.9 | Ser 366(2) | 1.99, 2.03 |

| 26. | Pulvinic acid | −6.8 | – | – |

| 27. | Adenosine | −6.8 | Tyr 106, Tyr 120, Ser 366 | 2.34, 2.61, 1.85 |

| 28. | N-Acetyl-D-Galactosamine | −6.7 | Tyr 106, Ser 366 | 2.10, 1.68 |

| 29. | N ∼ 5 ∼ -Carbamoyl-N ∼ 2∼-(phenylacetyl)ornithine | −6.7 | Tyr 106, His 453 | 4.06, 1.77 |

| 30. | Divaricatinic acid | −6.6 | Leu 495 | 2.16 |

| 31. | Glucosaminate | −6.2 | Tyr 120, Lys 131, His 453(2) | 1.69, 1.94, 2.04, 2.16 |

| 32. | 5-Chlorodivaricatinic acid | −6.1 | – | – |

| 33. | Aerugine | −5.9 | Tyr 120 | 2.07 |

| 34. | p-Coumaric acid | −5.9 | Ser 366 | 1.92 |

| 35. | Paraxanthine | −5.9 | Tyr 106, Leu 495 | 2.48, 1.81 |

| 36. | Phenylalanine | −5.4 | Tyr 106, Phe 496 | 2.19, 6.19 |

| 37. | Theobromine | −5.1 | Tyr 106(2), Phe 496 | 2.17, 4.80, 5.08 |

| 38. | Hexadecanoic acid | −5.0 | Tyr 120, His 453 | 2.08, 1.81 |

| 39. | Tetradecanoic acid | −4.3 | Tyr 120, His 453 | 2.03, 1.81 |

The drug Ketoconazole had dock score −7.6 Kcal/mol and interactions with the active site residues Tyr 120, His 369 and structurally conserved residue Tyr 52 (Fig. 8a). LC-MS derived plant compound Platyphylloside had dock score −13.2 kcal/mol and interactions with active site residues Tyr 106, Lys 131, His 453, with structurally conserved residues Pro 447, Phe 448 and Phe 496 (Fig. 8b). The compound (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl-6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside had interactions with active site residues Tyr 106, Tyr 120, His 365 and structurally conserved residue Ser 366 and Tyr 492 with dock score −12.6 kcal/mol. The compound 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one had −11.7 Kcal/mol dock score and interactions with active site residue Tyr 106, Tyr 120, Lys 131 and His 453. The above compounds which were elucidated from the epicarp of B. aegyptiaca had better anti-dermatophytic activity against the protein Cytochrome P450.

Fig. 8.

Docking result of CYP450 with (a) drug Ketoconazole, (b) Platyphylloside.

3.9. Molecular dynamics simulation

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is an important study to understand the stability of binding affinity of the ligand accompanying the protein during the simulation period. It was carried out using Desmond, Schrödinger for observing the stability of complex structures of Cyp450 with Platyphylloside and Cyp450 with Ketoconazole.

3.10. CYP450 with Platyphylloside

From the analysis of RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) plot, the complex structure of protein CYP450 and ligand Platyphylloside had showed that the fluctuations of both Cα atoms and ligand heavy atoms were within the acceptable range of 1–3.0 Å up to end of the simulation period (Fig. 9a) hence this complex was more stable.

Fig. 9.

MD simulation result of complex structure of CYP450 with Platyphylloside (a) Protein-Ligand RMSD, (b) Protein RMSF, (c) Protein-Ligand interactions, (d) Protein-Ligand contacts, (e) 2D diagram of interactions at 10th ns.

RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) plot shows that the fluctuation of individual residue of CYP450 protein. From the analysis, the residues from 280 to 320 and 380 to 410 had fluctuated more than other residues but they were not out of the range (Fig. 9b). The active site residues and other important residues were situated within the range. Hence protein was stable.

From the analysis of protein–ligand contacts, compound had hydrogen bond interactions with active site residues Tyr 120, Lys 131, His 365, Arg 369, His 453 with structurally and functionally conserved residues Leu 127, Ser 363, Phe 448, Ala 450, Arg 454, Cys 455, Leu 495 and Hydrophobic interactions with Tyr 106, Val 119, Ile 364, Phe 496 (Fig. 9c). Among these interactions the compound Platyphylloside had maintained its interaction with active site residues Tyr 106, Tyr 120, His 365, Arg 369, and His 453 from start to end of the simulation period (Fig. 9d). The Fig. 9e shows that the compound platyphylloside had hydrogen bond interactions with Tyr 120, His 365, Arg 369, Ala 450, His 453, Leu 495 at the 10th ns of simulation period.

3.11. Cyp450 with Ketoconazole

RMSD plot derived that the protein Cα atoms and heavy atoms of Ketoconazole were continuously fluctuated up to the end of the simulation period but the fluctuation is within the acceptable range of 3.0 Å (Fig. 10a). From the RMSF plot analysis, the residues from 280 to 320 were fluctuated more and other residues were within acceptable range (Fig. 10b).

Fig. 10.

MD simulation result of complex structure of CYP450 with Ketoconazole (a) Protein-Ligand RMSD, (b) Protein RMSF, (c) Protein-Ligand interactions, (d) Protein-Ligand contacts, (e) 2D diagram of interactions at 10th ns.

The protein–ligand contact plot shows that the hydrogen bond interactions were observed with the structurally conserved residues Tyr 52, Ser 363, Pro 447 and hydrophobic interactions with active site residue Tyr 106 and other structurally conserved residues Leu 109, Phe 114, Ile 364, Met 368, Cys 455, Leu 495 and Phe 496 by drug Ketoconazole (Fig. 10c). Among these, Tyr 52 and Tyr 106 Ile 364 and Pro 447 had maintained their interactions with maximum time period of simulation (Fig. 10d). The 2D image shows that the drug Ketoconazole had hydrogen bond interactions with Tyr 52, Ser 363, Pro 447 and Pi-Pi interaction with active site residue Tyr 106 (Fig. 10e).

From the study of various factors of MD simulation, the docked complex structure of CYP450-Platyphylloside was more stable than CYP450-Ketoconazole complex, also Platyphylloside had more number of interactions with active site residues. This study finds that the compound Platyphylloside has good antidermatophytic activity against the CYP450 protein in T. rubrum.

4. Discussion

Among the human diseases, dermatophytoses are the fourth most prevalent affecting nearly quarter of the world’s population (Hay et al., 2014). T. rubrum is the predominant disease causing agent accounting for 69.5% followed by other species of Trichophyton (Bristow and Spruce, 2009). Providing safer and cost-effective treatment is a need of the hour.

The water and methanol extract of B.aegyptiaca fruit had apparent antifungal activity on Candida and Aspergillus species (Abdallah et al., 2012). The bark of this plant is also used for wounds and skin diseases (Anani et al., 2015). According to Hussain et al. (2019), the fractioned methanol extract of sweet mesocarp had potential against M. gypseum and T. rubrum.

Saponins are very rich bioactive properties; especially they had antifungal activity especially anticandidal activity (Saha.S, S. Walia, J. Kumar and B. Parmar. , 2010, Nwachukwu, 2017). The rhizomes of C. cuspidatus had saponins which showed anticandidal and antidermatophytic activity especially against T. rubrum (Cota et al., 2020). Further, flavonoids, steroids and phenolic compounds had potent antifungal activity (Hassan et al., 2006). In the present study, the chloroform extract of epicarp displays saponins, steroids, flavonoids and phenols can be showed the inhibitory activity against T. rubrum.

According to Wu et al. (2018), the CYP51 is an important for mycelial growth and elongation. The drug VT1161 showed more than 20 interactions including H-bonds and other types of interactions in the region of helix, strand and loops in Lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase (CYP450) of C. albicans in the crystal structure 5TZ1 (Hargrove et al., 2017). In the present docking study, the residues Tyr 106, Lys 131, Ser 366, His 453 interacted in the docked complex structure of Platyphylloside, (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl-6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside and 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl) oxan-2-yl] xanthen-9-one with CYP450 in T. rubrum which were the equivalent residues in the C. albicans. The compounds Platyphylloside, (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl-6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside and 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one are organic compounds under the class of diarylheptanoids, fatty acyl glycosides and benzopyrans compounds, respectively. Diarylheptanoids have good antifungal activity against F. equiseti, F. tricinctum, C. albicans, S. cerevisiae and A. flavus, A. parasiticus (Ganapathy et al., 2019). According to Akpinar et al. (2018), the benzopyrans have good antimicrobial activity against gram positive (S. aureus) and gram negative (E. coli) bacteria.

Platyphylloside found to interact with influential residues of CYP450 protein and the stability of the complex is good because RMSD and RMSF values were within the acceptable area. Also, Platyphylloside never lost the interaction from start to end with Tyr 106, Tyr 120, His 365, Arg 369, His 453, Ile 456 which were an important residue in Helix B region of CYP450 protein for ergosterol biosynthesis in dermatophytes (Zhang et al., 2019). Platyphylloside is an important compound in class diarylheptenoids from black alder and this compound has good antimicrobial activity especially against C. albicans and S. cerevisiae (Novakovic’ et al., 2015). Hence, this study strongly recommends Platyphylloside had better antidermatophytic activity than the drug ketoconazole hence further this compound will be evaluated for finding its efficiency against T. rubrum.

5. Conclusion

The plant B. aegyptiaca has potent medicinal properties; this study determined that through the fractioned chloroform extract of epicarp against tinea causing pathogen T. rubrum. Further, in silico study confirmed that the compounds Platyphylloside, (3E)-7-Hydroxy-3,7-dimethyl-3-octen-1-yl-6-O-(6-deoxy-alpha-L-mannopyranosyl)-beta-D-glucopyranoside and 1,3,6-trihydroxy-5-methoxy-2-[(2S,3R,4R,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]xanthen-9-one that were elucidated from the epicarp interacted with the influential residues of CYP450 protein of T. rubrum. This study exhibited that the compound Platyphylloside is highly potential against dermatophytes. Platyphylloside will be subjected to further studies in order to determine their efficacy through in vitro and in vivo experiments against T. rubrum.

Authors Contribution

MJ – Planned and monitored, SAMH - Execute and written all the works, MAA – Supporting lab facilities and funding, AAH – Contributed in manuscript preparation and funding, HAA – Contributed in data analysis and financial support, P – Data analysis and writing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors extend their appreciation to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP-2021/316), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Ethical statement

This study has not used the human and animal samples.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.03.017.

Contributor Information

Mohamed Hussain Syed Abuthakir, Email: biothakir@gmail.com.

Munirah Abdullah Al-Dosary, Email: almonerah@ksu.edu.sa.

Ashraf Atef Hatamleh, Email: ahatamleh@ksu.edu.sa.

Hissah Abdulrahman Alodaini, Email: halodaini@ksu.edu.sa.

P. Perumal, Email: perumal@igs.cnrs-mrs.fr.

Muthusamy Jeyam, Email: jeyam@buc.edu.in.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- Abdallah E.M., Hsouna A.B., Khalifa K.S.A. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and phytochemical investigation of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. edible fruit from Sudan. African J. Biotechnol. 2012;11(52):11535–11542. [Google Scholar]

- Aier I., Varadwaj P.K., Raj U. Structural insights into conformational stability of both wild-type and mutant EZH2 receptor. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(34984):1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep34984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akpınar, D.E., M. Ozgur, H.Aslam, O.Alagoz, A.Oktemer, H.Dal, T.Holelek, E.Logoglu. 2018. Synthesis, characterization, and investigations of antimicrobial activity of benzopyrans, benzofurans and spiro [4.5]decanes. An International Journal for Rapid Communication of Synthetic Organic Chemistry. 48(19): 2510-2521.

- Al-Thobaiti S.A., Zeid I.A. Medicinal properties of desert plants (Balanites aegyptiaca) – an overview. Global J. Pharmacol. 2018;12(1):01–12. [Google Scholar]

- Anani K., Adjrah Y., Ameyapoh Y., Karou S.D., Agbonon A., de Souza C., Gbeassor M. Effects of hydroethanolic extracts of Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile (Balanitaceae) on some resistant pathogens bacteria isolated from wounds. J. Ethnophamacol. 2015;164:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald R.G. The use of the fruit of tree Balanites aegyptiaca in the control of Schistosomiasis in the Sudan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Hygiene. 1933;27:207. [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar S., Rajan S., Thirunalasundari T., Jeeva S. Antifungal activity of Ocimum sanctum Linn. (Lamiaceae) on clinically isolated dermatophytic fungi. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Med. 2011;4(8):654–657. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi P., Behzadi E., Ranjibar R. Dermatophytic funfi: infections, diagnosis and treatment. SMU Med. J. 2014;1(2):50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Blutfield M.S., Lohre J.M., Pawich D.A., Vlahovic T.C. The immunologic response to Trichophyton rubrum in lower extremity fungal infections. J. Fungi. 2015;1(2):130–137. doi: 10.3390/jof1020130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow I.R., Spruce M.C. Fungal foot infection, cellulitis and diabetes: a review. Diab. Med. 2009;26:548–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmester A., Shelest E., Glöckner G., Heddergott C., Schindler S., Staib P., A., et al. Comparative and functional genomics provide insights into the pathogenicity of dermatophytic fungi. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alvarez A., Costa A.M., Vilarrasa J. The performance of several docking programs at reproducing protein–macrolide-like crystal structures. Molecules. 2017;22(136):1–14. doi: 10.3390/molecules22010136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D., Oezguen N., Urvil P., Ferguson C., Dann S.M., Savidge T.C. Regulation of protein-ligand binding affinity by hydrogen bond pairing. J. Comput. Chem. 2016;2(3):1–16. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota B.B., Oliveira D.B., Borges T.C., Catto A.C., Serafim C.V., Rodrigues A.R.A., et al. Antifungal activity of extracts and purified saponins from the rhizomes of C.cuspidatus against Candida and Trichophyton species. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020;130:61–75. doi: 10.1111/jam.14783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edoga H.O., Okwu D.E., Mbaebie B.O. Phytochemicals constituents of some Nigerian medicinal plants. African J. Biotechnol. 2005;4(7):685–688. [Google Scholar]

- El-Nagerbi A.F.S., Abdulkadir E., Elamin M.R. In vitro activity of balanites aegyptiaca and tamarindus indica fruit extracts on growth and Aflatoxigenicity of Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. J. Food Res. 2013;2(4):68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ganapathy G., Preethi R., Moses J.A., Anandharamakrishnan C. Diarylheptanoids as nutraceutical: a review. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019;19(101109):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaonkar S.L., Hakkimane S.S., Bharath B.R., Shenoy V.P., Vignesh U.N., Guru B.R. Stable isoniazid derivatives: in silico studies, synthesis and biological assessment against mycobacterium tuberculosis in liquid culture. RASAYAN J. Chem. 2020;13(3):1853–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum M. Azole resistance in dermatophytes: Prevalance of mechanism of action. J. Am. Pediat. Med. Assoc. 2016;106:79–86. doi: 10.7547/14-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover R.K., Moore J.D. Toxicometric studies of fungicides against brown rot organisms Sclerotinia fructicola and S. laxa. Phytopathology. 1962;52:876–880. [Google Scholar]

- Harborne J.B. Chapman and Hall; London: 1998. Phytochemical Methods: A Guide to Modern Technique of Plant Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Hargrove T.Y., Friggeri L., Wawrzak Z., Qi A., Hoekstra W.J., Schotzinger R.J., York J.D., Guengerich F.P., Lepesheva G.I. Structural analyses of Candida albicans sterol 14_-demethylase complexed with azole drugs address the molecular basis of azole-mediated inhibition of fungal sterol biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292(16):6728–6743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.778308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S.W., Bilbis F.L., Ladan M.J., Umar R.A., Dangoggo S.M., Saidu Y., Abubakar S.M., Faruk U.Z. Evaluation of antifungal activity and phytochemical analysis of leaves, roots and stem barks extracts of Calotropis procera (Asclepiadaceae) Pakistan J. Biol. Sci. 2006;9(14):2624–2629. [Google Scholar]

- Hay R., Johns N., Williams H., Bolliger I., Dellavalle R., Margolis D., Marks R., Naldi L., Weinstock M., Wulf S., et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010. An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014;134:1527–1534. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M.S.A., Velusamy S., Muthusamy J. Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. for dermatophytose: ascertaining the efficacy and mode of action through experimental and computational approaches. Inform. Med. Unlocked. 2019;15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal M.S. A furosyanol saponin from fruits of Balanites aegyptiaca. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:755–757. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(97)01015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S., Yadav S., Dorga S. Treatment of dermatophytosis in elderly, children and pregnant women. Ind. Dermatol. Online. 2017;8(5):310–318. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_169_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokate, C.K., Purohit, A.P., Gokhale, S.B., 2006. Pharmacogognosy, Edn 35, Nirali Prakashan, Pune, pp. 98–114.

- Lamb D.C., Waterman M.R., Kelly S.L., Guengerich F.P. Cytochrome P450 and drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007;18:504–512. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., MacArthur M.W., Moss D.S., Thornton J.M. PROCHECK - a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1993;26(2):283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rossi N.M., Peres N.T.A., Rossi A. Antifungal resistance mechanisms in dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:369383. doi: 10.1007/s11046-008-9110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascente P.d.S., Meinerz A.R.M., Faria R.O.d., Schuch L.F.D., Meireles M.C.A., Mello J.R.B.d. CLSI broth microdilution method for testing susceptibility of Malassezia pachydermatis to thiabendazole. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2009;40(2):222–226. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822009000200002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navone L., Speight R. Understanding the dynamics of keratin weakening and hydrolysis by proteases. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novakovic’ M., Novaković I., Cvetković M., Sladić D., Tesˇević V. Antimicrobial activity of the diarylheptanoids from the black and green alder. Braz. J. Bot. 2015;38(3):441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu I.N. Antifungal activities and phytochemical constituents of nicotiana tabacum leaf extracts on selected dermatophytes. Nijerial J. Microbiol. 2017;31(2):3871–3875. [Google Scholar]

- Pandit B.R., Kotiwar O.S., Oza R.A., Kumar R.M. Ethno-medicinal plant lore from Gir forest, Gujarat. Adv. Plant Sci. 1996;9:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Parker J.E., Warrilow A.G.S., Price C.L., Mullins J.G.L., Kelly D.E., Kelly S.L. Resistance to antifungals that target CYP51. J. Chem. Biol. 2014;7(4):143–161. doi: 10.1007/s12154-014-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabitha K., Vijayalakshmi R. Finding new inhibitors for EML4-ALK fusion protein: a computational approach. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012;3(3):171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Saha.S, S. Walia, J. Kumar and B. Parmar. Structure-biological activity relationships in triterpenic saponins: the relative activity of protobassic and its derivatives against plant pathogenic fungi. Pest Manage. Sci. 2010;66:825–831. doi: 10.1002/ps.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya A.K. Medicinal plants: future source of new drugs. Int. J. Herbal Med. 2016;4(4):59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sievers F., Higgins D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Prot. Sci. 2017;27(1):135–145. doi: 10.1002/pro.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taamalli A., Arraez-Roman D., Abaza L., Iswaldi I., Fernadez-Gutierrez A., Zarrouk M., Segura-Carretero A. LC-MS_based metabolite profiling of methanolic extracts from the medicinal and aromatic species Mentha pulegium and Origanum majorana. Phytochem Anal. 2015;26(5):320–330. doi: 10.1002/pca.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Carver J.J., Phelan V.V., Sanchez L.M., N.Garg Y.Peng, et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nature biotechnology. 2016;34(8):828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Wu M., Wang Y., Chen Y., Gao J., Ying C. ERG11 couples oxidative stress adaptation, hyphal elongation, and virulence in Candida albicans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018;18(foy057) doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foy057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D., Zhang Y. Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization. Biophys. J. 2011;101:2525–2534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A.Y., Camp W.L., Elewski B.E. Advances in topical and systemic antifungals. Dermatol. Clin. 2007;25:165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Khetan A., Er S. A quantitative evaluation of computational methods to accelerate the study of alloxazine-derived electroactive compounds for energy storage. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4089. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83605-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Li L., Quanzhen L.V., Yan L., Wang Y., Jiang Y. The fungal CYP51s: their functions, structures, related drug resistance and inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10(691):1–17. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.