Abstract

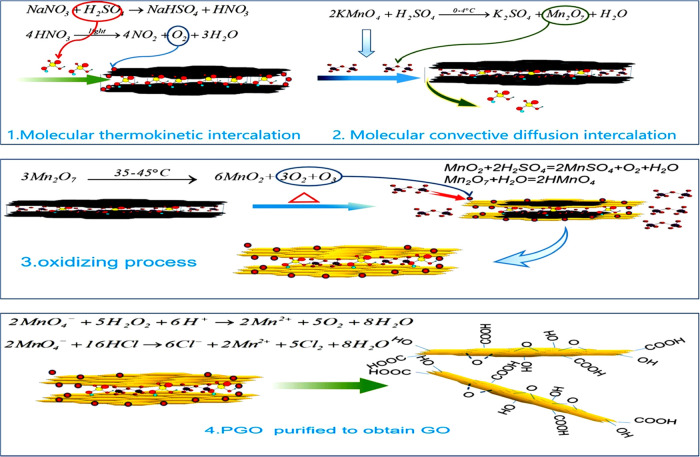

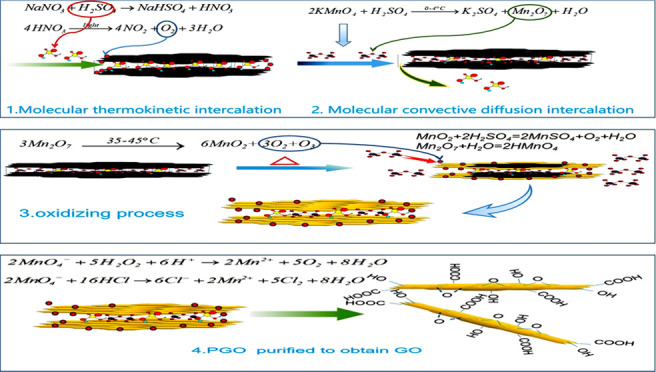

The mechanism of oxidizing reaction in the preparation of graphene oxide (GO) by a chemical oxidation method remains unclear. The main oxidant of graphite oxide has not been determined. Here, we show a new mechanism in which Mn2O7, the main oxidant, is heated to decompose oxygen atoms and react with graphite. The whole preparation process constitutes of four distinct independent steps, different from the three steps of literature registration, and each step has its own chemical oxidation reaction. In the first step, concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid are intercalated between graphite layers in the form of a molecular thermal motion to produce HNO3–H2SO4–GIC. In the second step, Mn2O7 is intercalated between graphite layers in the molecular convection–diffusion to Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC. In the third step, Mn2O7 is decomposed by heat. Oxygen atoms are generated to oxidize the defects in the graphite layer to PGO. This discovery is the latest and most important. In the fourth step, PGO is purified with deionized water, hydrogen peroxide, and hydrochloric acid to GO. Optical microscopy, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction spectrometry, and scanning electron microscopy analytical evidence was used for confirming Mn2O7 as the main oxidant and the structure of GO. This work provides a more plausible explanation for the mechanism of oxidizing reaction in the preparation of GO by a chemical oxidation method.

1. Introduction

Graphene oxide (GO), as a derivative of graphene, not only has excellent shielding performance, high aspect ratio, ultrahigh strength, ultrahigh thermal conductivity, high surface activity, and other advantages, all of which are possessed by graphene, but also has carboxyl group, hydroxyl group, epoxy group, and other functional groups that can be prepared derivatives. Studying its application in many fields such as electronics, energy storage, catalysis, plastics, textiles, and coatings has become a hotspot.1−6 The classic chemical oxidation methods for the preparation of GO include those by Brodie,7 Staudenmaier,8 and Hummers.9 All of these methods take graphite (GT) as the raw material for oxidation reaction with different strong oxidants and then peel off to give GO. Compared with the previous two preparation methods, the Hummers method has a short reaction time, high efficiency, and high safety, which bring promise for the industrial preparation of GO. Therefore, researchers are actively seeking some improved methods based on the Hummers method. These methods mainly include preoxidation treatment,10 changing oxidation intercalation agent, electrochemically assisted method, ultrasonic-assisted method, microwave-assisted method, etc.11−14 However, a clear understanding of the mechanism of the reaction would provide a powerful boost to these efforts.

Unfortunately, most of the researchers’ works are focused on the functionalization of GO, preparation of complexes, and application research,15−24 and there are few studies on the oxidation reaction mechanism.25,26 Especially, how does the chemical reaction of the KMnO4–H2SO4 oxidation system occurs in the Hummers method and which oxidizing substance is oxidized with graphite are unknown. Fortunately, several researchers have studied the mechanism of preparation of GO by oxidizing intercalated graphite with oxidants, laying a certain theoretical foundation. Yang et al.27 believed that MnO4– was the main oxidant during the oxidation of the C=C bond on graphite, and two oxidation groups, −OH and −O–, were generated on the graphene surface. Dreyer et al.28 suspected in the review that Mn2O7 was used as an oxidant and the main oxidation reaction occurred with graphite in the Hummers method. However, this conjecture was put forward mainly based on Trömel’s work,29 who proved that Mn2O7 has stronger oxidability than other manganese compounds in the oxidation reaction with organic compounds. Dimiev et al.30 guessed that the main oxide in the pristine graphite oxide (PGO) formation was MnO3+ because MnO3HSO4 or (MnO3)2SO4 existed in nonionic form in almost 100% concentrated sulfuric acid at this time.31 However, these oxidation reaction mechanisms of GO generation are all conjectures based on the research results of other researchers in other fields and have not been systematically studied.

In this work, we revealed the reaction mechanism of oxidizing graphite oxide in the preparation of GO and determined that Mn2O7 was the main oxidizing agent combined with the reaction conditions and the process of the Hummers method. Different from what was reported in the literature, we determined that the process of GO preparation by the Hummers method was divided into four steps. Among them, the mass ratio of Mn2O7 produced by potassium permanganate in the second step was 4 times that of graphite, which reacted with concentrated sulfuric acid at low temperature (0–4 °C). Mn2O7 intercalated between graphite layers in molecular convection–diffusion, replacing some of the sulfuric acid molecules, to form Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC. Mn2O7 was decomposed by heat in the third step. Oxygen atoms were generated to oxidize the defects in the graphite layer to PGO. This work provided a more plausible explanation for the mechanism of oxidizing reaction in the preparation of GO by the Mn2O7–H2SO4 oxidation method.

2. Results and Discussion

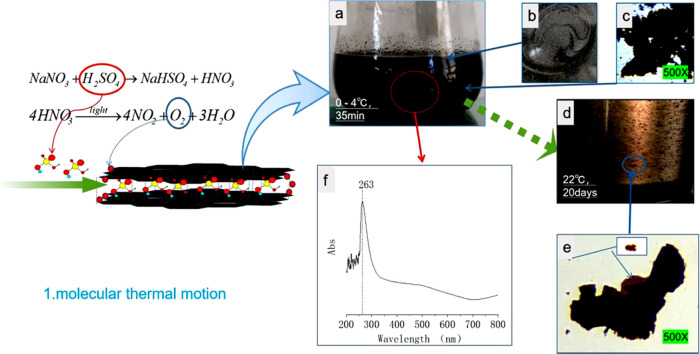

2.1. HNO3–H2SO4–GIC was Formed by Molecular Thermal Intercalation

The first step in the preparation of GO by Hummers method is to add a certain amount of NaNO3 (about 1/120 mass ratio to 98% sulfuric acid) into 98% sulfuric acid, completely dissolve it at room temperature (20–30 °C), then cool the solution to 0–4 °C, add flake graphite (about 1/60 mass ratio to concentrated sulfuric acid), and stir and disperse for 30–40 min. As graphite is suspended in concentrated sulfuric acid, the liquid mixture appears black (Figure 1a); however, the graphite does not lose its metallic luster as observed from the liquid surface (Figure 1b). A small amount of mixed liquid (NML) is placed on a slide and observed under an optical microscope at 500×. The entire graphite sheet is black, indicating that the chemical electromotive force of concentrated sulfuric acid is weak and it is difficult to oxidize graphite at low temperature. However, an interesting phenomenon is that the originally dispersed graphite sheets gradually gather into clusters (Figure 1c), which indicates that the molecules of concentrated sulfuric acid are not ionized and cannot prevent the positively charged graphite sheets from gathering.32 After storing the mixture at 22 °C for 20 days (Figure 1d), the liquid in the bottle was slightly light brown. Small pieces of graphite, observed with a light microscope with 500× magnification, are oxidized to golden color and the edges of large pieces of graphite are oxidized to golden color, while the center is still black (Figure 1e). The UV–vis spectrum of the mixed liquid has a characteristic peak at 263 nm, which may be the absorption spectrum of HNO3 (Figure 1f). This new discovery indicates that the NaNO3–H2SO4 oxidation system can oxidize graphite, but the reaction rate is slow. Because concentrated sulfuric acid can only show hydroscopicity and dehydration at low temperature, it can only show strong oxidization when heated and can be oxidized with carbon,33 while HNO3 only needs light to decompose oxygen atoms. Therefore, in the first stage at a low temperature, the oxidant that NaNO3–H2SO4 oxidation system can oxidize with graphite should be the oxygen atom decomposed by HNO3. The reaction equations are as follows

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

In this step, it is difficult to intercalate the H2SO4 molecule into the graphite lamellar because the spacing between the graphite lamellar layers is only 0.34 nm, while the H2SO4 molecule is about 0.39 nm in diameter and exists in the form of a nonion. Therefore, NaNO3 needs to be added to react with concentrated sulfuric acid to generate HNO3, then small molecules of oxygen atoms are generated, carbon atoms at the edge of graphite are oxidized, and the graphite lamellar channel is opened and then diffused into graphite sheets by molecular thermal motion to realize the intercalation of HNO3–H2SO4–GIC. The intercalation interval is increased to 0.798 nm.34 This theory is consistent with the experimental results of the preoxidation treatment.

Figure 1.

Photographs and UV–vis spectra of NaNO3–H2SO4–GIC. (a) Photographs of the liquid composed of concentrated H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT and stirred at 0 °C for 30 min. (b) GT on the surface of concentrated sulfuric acid with a metallic luster. (c) Optical microphotographs (500×) of a graphite flake in concentrated sulfuric acid. (d) Photographs of a liquid composed of concentrated H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT and stored at 22 °C for 20 days. (e) Optical microphotographs (500×) of HNO3–H2SO4–GIC diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and placed at 8 °C for 20 days. (f) UV–vis spectra of HNO3–H2SO4–GIC diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and stirred at 0 °C for 30 min.

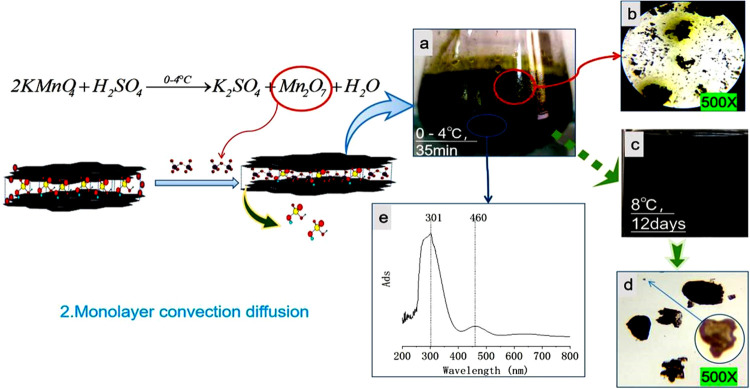

2.2. Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC Was Formed by Molecular Convection–Diffusion

Potassium permanganate (4 times the graphite mass ratios) was added to the reaction liquid in the first step at 0–4 °C. After stirring for about 3–5 min, the liquid turned dark green (Figure 2a). Thirty minutes later, the mixed liquid (FLML) was formed and observed under an optical microscope. It was found that the graphite sheet was black-green. However, there was a special phenomenon that the blended liquid sample was placed between two slides. Different from NML, the graphite slices were dispersed from each other without aggregation, and the concentration of the dark green solution between the graphite slices was uneven. A more noteworthy phenomenon was the continuous diffusion of dark green liquid from the graphite layer to the surrounding area of low concentration, resulting in the dark green material around the graphite sheet (Figure 2b). This phenomenon suggests that the dark green material in the mixed solution was intercalated into the graphite sheet layer, and this intercalation was reversible. When the concentration of dark green material in the solution body is higher than the graphite sheet, it will diffuse into the graphite sheet layer; on the contrary, it will diffuse out from the graphite sheet layer. In the first step, when HNO3–H2SO4–GIC was formed without potassium permanganate, concentrated sulfuric acid was colorless and this phenomenon could be easily observed. When the solution sample was refrigerated at 8 °C for 12 days (Figure 2c), the mixed liquid was still dark green and most of the graphite sheets were still dark green. However, the center of the small graphite sheet was yellow and transparent and the edge was dark purple (Figure 2d). This phenomenon further indicated that the oxidation reaction of HNO3–H2SO4–GIC occurred at 8 °C, but the reaction speed was slow, and the rapid oxidation of large graphite sheets could not be achieved. When potassium permanganate was added, a dark green substance was produced that did not oxidize with graphite at low temperatures. The mixed liquid was characterized by UV–vis spectra (Figure 2e). There was a strong absorption peak at 301 nm, a weak absorption peak at 460 nm, and the absorption peak at 263 nm disappeared, as shown in Figure 1e.

Figure 2.

Photographs and the UV–vis spectra of Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC. (a) Photographs of a liquid composed of concentrated KMnO4 + H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT and stirred at 0–4 °C for 30 min. (b) Optical microphotographs (500×) of a graphite flake in concentrated sulfuric acid. (c) Photographs of liquid composed of concentrated KMnO4 + H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT and stored at 8 °C for 12 days. (d) Optical microphotographs (500×) of Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and stored at 8 °C for 12 days. (e) UV–vis spectra of KMnO4 + H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and stirred at 0–4 °C for 30 min.

Potassium permanganate in excess concentrated sulfuric acid at a low temperature produced dark green Mn2O7 liquid, which was also its preparation method.35 The reaction equation is as follows

| 4 |

| 5 |

Accordingly, we can think that 301 nm is the absorption peak of Mn2O7. Because the interlayer distance of HNO3–H2SO4–GIC is 0.798 nm and the molecular diameter of Mn2O7 is less than 0.671 nm, Mn2O7 molecules can intercalate from the external high-concentration liquid to the low-concentration liquid between the graphite layers in the form of a molecular convection–diffusion and replace part of the HNO3–H2SO4 mixture. A new Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC compound is formed.

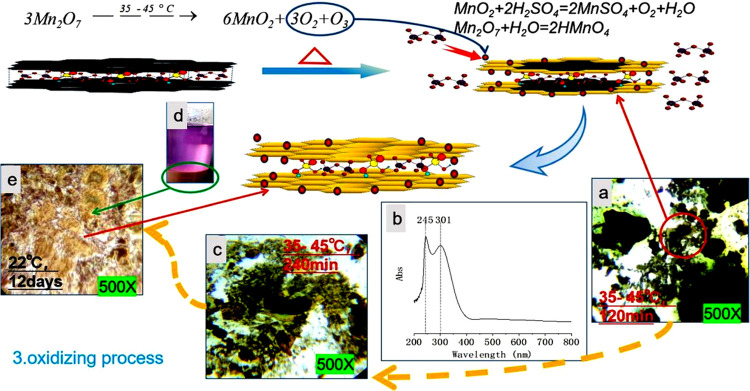

2.3. Oxygen Atoms Oxidize the Defects of the Graphite Layer to Form PGO

After the intercalation of Mn2O7 was completed to generate the Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC compound, the mixed solution was heated to 35–45 °C and heat preservation, agitation, and the reaction continued. Figure 3 shows the color changes of the graphite layer tracked and characterized by an optical microscope at different time periods of the reaction process, and UV–vis spectra of mixed liquid (OHML). When the reaction continued for 120 min, small pieces of graphite were completely oxidized to a yellow transparent sheet. The center of the medium-sized graphite sheet was dark green with a yellow and transparent surrounding. Large sheets of graphite were almost dark green, with very few edges oxidized to yellow (Figure 3a). After 240 min, the mixed solution turned brown, and almost all of the medium-sized graphite sheets were oxidized to yellow transparent sheets, and the larger graphite pieces showed a color from yellow to green to black-green from the edge to the center (Figure 3c). At this time, in the UV–vis (Figure 3b) spectrum of the mixed liquid, there was still a strong absorption peak at 301 nm and a stronger absorption peak at 245 nm, while the weak absorption peak at 460 nm disappeared in Figure 2d. Part of the mixed solution was diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and stored at 22 °C for 12 days. Virtually all of the graphite sheets became yellow transparent sheets (Figure 3e) and the supernatant turned purple red (Figure 3d), which is the color shown by Mn7+ ions.

Figure 3.

Optical microphotographs (500×) and UV–vis spectra of oxide reaction of Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC at 35–45 °C. (a) Liquid composed of KMnO4 + H2SO4+ NaNO3 + GT and stirred at 35–45 °C for 120 min. (b) UV–vis spectra of KMnO4 + H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and stirred at 35–45 °C for 240 min. (c) Liquid composed of KMnO4 + H2SO4 + NaNO3 + GT and stirred at 35–45 °C for 240 min. (d) Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and placed at 22 °C for 12 days. (e) Optical microphotographs (500×) of Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC diluted with concentrated sulfuric acid and placed at 22 °C for 12 days.

Therefore, it can be inferred that Mn2O7 decomposes and generates oxygen atoms at 35–45 °C and then produces oxygen and ozone to oxidize the graphite defects. Moreover, Mn2O7 has strong oxidation C=C bond of graphene bond, which will break and oxidize the graphene bond in the middle of the graphene sheet. A high oxidation level is obtained by oxidizing GO with ozone,36,37 which also indicates that ozone can oxidize carbon on graphite sheets. The color gradient of the graphite sheet from the edge to the center also indicates that Mn2O7 is intercalated between the graphite layers. At the same time, MnO2 is produced in this reaction, which continues to react with excess concentrated sulfuric acid to produce MnSO4, water, and oxygen. The water reacts with Mn2O7 to produce permanganic acid, which is dissolved in sulfuric acid and showed purplish-red color. The oxidation reaction equation is as follows

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

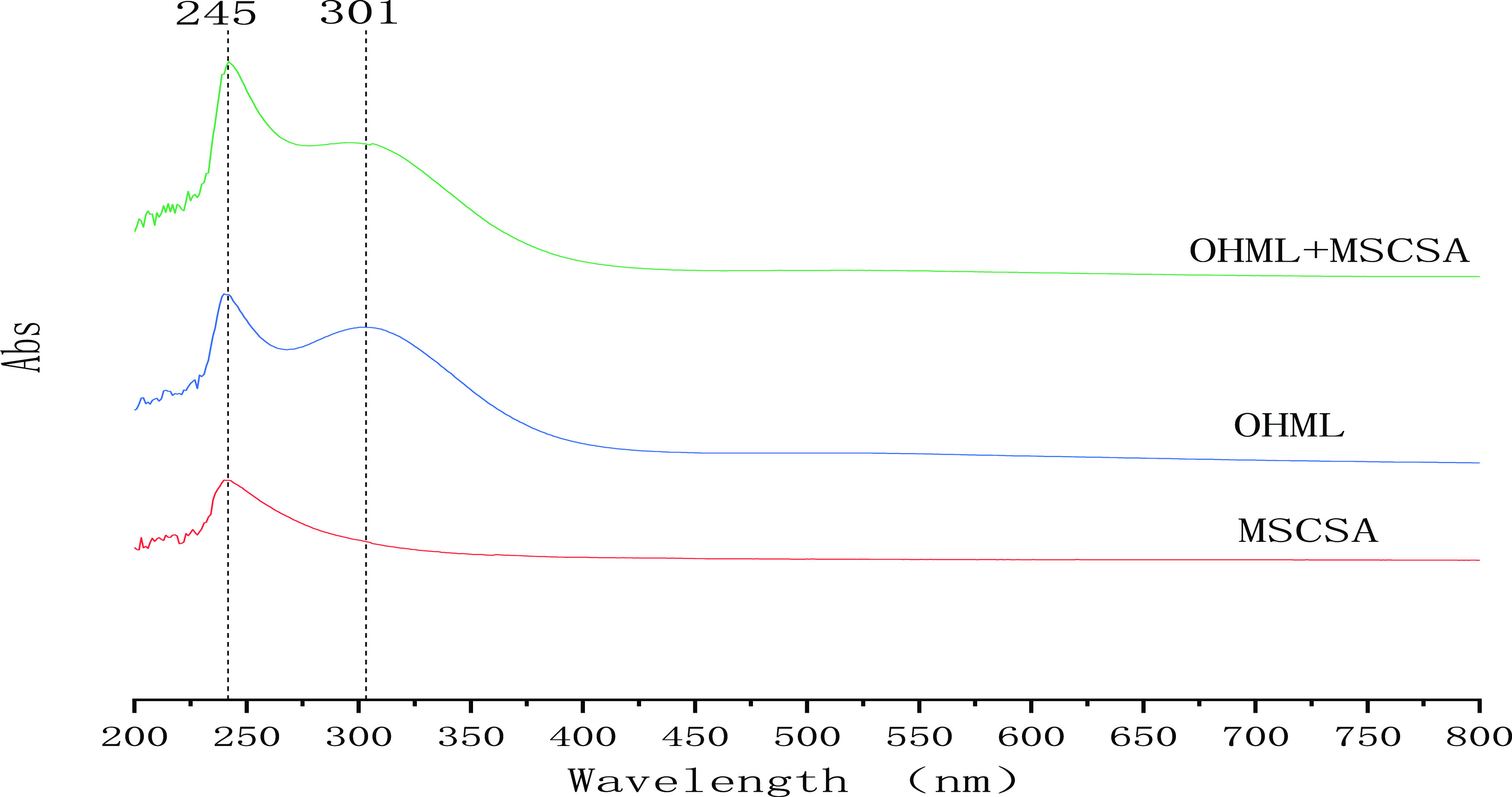

To further confirm the reaction mechanism, it is necessary to verify the formation of MnSO4 in the mixed solution by UV–vis spectroscopy. Figure 4 shows the UV–vis spectra of 2% MnSO4 in concentrated sulfuric acid(MSCSA), the UV–vis spectra of the mixed solution(OHML) after reaction at 35–45 °C and 240 min in third step process, the UV–vis spectra of the mixed solution(OHML + MSCSA) by MSCSA was added to OHML. The spectrogram of OHML+MSCSA is obtained by adding MnSO4 content in OHML. Compared with OHML, the absorption peak at 245 nm is stronger, and the absorption peak at 301 nm is weaker, indicating that the absorption peak at 243 nm in OHML is characteristic of MnSO4 and that at 301 nm is characteristic of Mn2O7. Therefore, this mechanism of the chemical oxidation reaction is reasonable.

Figure 4.

Ultraviolet–vis spectrum of manganese sulfate in OHML confirmed with the internal standard method.

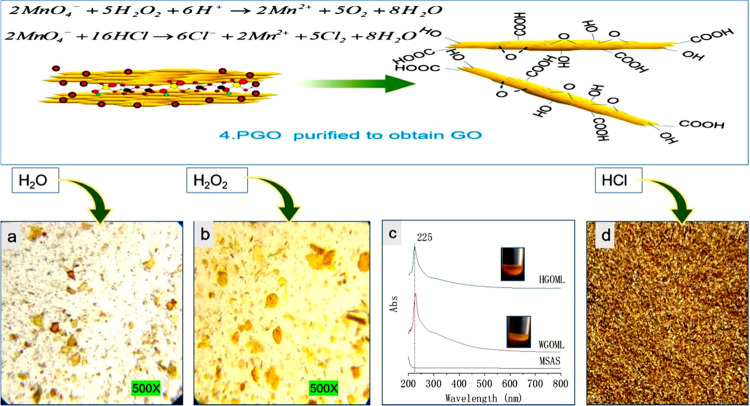

2.4. Purification of PGO to Obtain GO

After the Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC compound was completely oxidized to yellow PGO, as observed using a light microscope, deionized water was added to the mixed solution. At this time, the solution (WGOML) turned from brown to brown-yellow and the graphite oxide sheet turned brown or golden (Figure 5a). The temperature of the reaction solution increased rapidly. This phenomenon shows that water reacts with the remaining Mn2O7 to generate permanganic acid, and concentrated sulfuric acid is a dilution process. A lot of heat is released during the dilution process, so water is added fewer times to prevent the temperature of the reaction system from rising too fast. At the same time, water also participates in the reaction with the C=O bond on the graphite oxide layer to produce oxygen-containing functional groups.38 Then, hydrogen peroxide is added at about 90–95 °C to oxidize MnO4– in the solution (HGOML) to Mn2+ for subsequent washing. Mn2+ is colorless, so the graphite oxide sheet is almost golden yellow at this time (Figure 5b). After the temperature of the solution is dropped to 60 °C, the solution is washed several times with 5% hydrochloric acid with vacuum filtration (at this time, there was a pungent smell of chlorine), and the filter cake was golden yellow (Figure 5d). We believe that the principle of washing the mixed solution with HCl in the fourth process is to use Cl–, oxygen-free, and small molecular diameter, to facilitate intercalation into oxidized graphite layers to replace sulfate ions and manganese ions between graphite oxide layers, which is conducive to vacuum extraction and filtration separation. In the vacuum filtration process, the filtrate of the mixture with hydrochloric acid passes through the cake much faster than the mixture without hydrochloric acid. Then, GO was diluted with deionized water, centrifuged, washed to a pH of 5–6, and then dried into solid GO in a vacuum drying oven at 65 °C. The reaction equation is as follows

| 9 |

| 10 |

Figure 5c shows the UV–vis spectra of the MnSO4 aqueous solution (MSAS), the mixed solution with added deionized water (WGOML) after the complete oxidation of the Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC compound to PGO, and the mixed solution with added hydrogen peroxide (HGOML). MSAS has no characteristic absorption peak between 200 and 800 nm, while WGOML and HGOML have an identical absorption peak at 225 nm, which should be the contribution of GO. At this stage, all Mn7+ is reduced to Mn2+, and there is no absorption peak in the aqueous solution. This phenomenon can confirm the rationality of the reaction theory.

Figure 5.

Optical microphotographs (500×) and UV–vis spectra of the process of GO from PGO. (a) Optical microphotographs (500×) of PGO in WGOML. (b) Optical microphotographs (500×) of PGO in HGOML. (c) UV–vis spectra of MSAS, WGOML, and HGOML. (d) Filter cake after washing with hydrochloric acid and vacuum extraction.

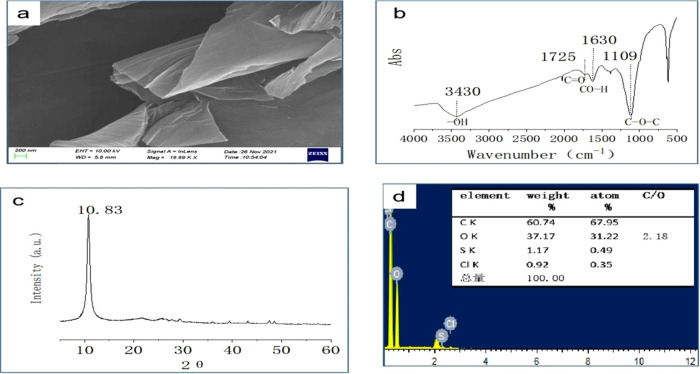

Figure 6 shows the SEM morphology, FTIR, XRD, and EDS characterization data of GO prepared according to the chemical oxidation reaction theory. The results show that the SEM morphology shows that GO is a thin gauze film (Figure 6a). The FTIR spectrum (Figure 6b) shows a wider and stronger absorption peak of GO near 3430 cm–1, which is attributed to the stretching vibration peak of −OH. The peak at 1725 cm–1 is the stretching vibration peak of C=O on the carboxyl group of graphite oxide. The peak at 1630 cm–1 is the bending vibration absorption peak of C–OH. The peak at 1110 cm–1 is the vibration absorption peak of C–O–C. In the XRD spectra, 2θ = 10.83° is the characteristic peak of GO (Figure 6c). EDS data shows that the C/O ratio of GO is 2.18, indicating a high oxidation degree (Figure 6d). These characterizations indicate that the reaction yields ideal GO. Figure 7 summarizes and schematically represents the four steps constituting the process of conversion of bulk graphite into GO and the chemical reactions in every step.

Figure 6.

(a) SEM images, (b) FTIR spectra, (c) XRD data, and (d) EDS data for GO.

Figure 7.

Reaction mechanism of the conversion of flake graphite into GO by a chemical oxidation process.

3. Conclusions

In general, different from previous research results, this paper reveals that the preparation of GO by the Hummers method involves four steps, and each step has an independent chemical reaction. Mn2O7, the main oxidant, is heated to decompose oxygen atoms and react with graphite. In the first step, concentrated sulfuric acid and nitric acid are intercalated between graphite layers in the form of a molecular thermal motion to produce HNO3–H2SO4–GIC. In the second step, Mn2O7 is produced by the reaction of potassium permanganate with concentrated sulfuric acid at low temperature (0–4 °C). Mn2O7 is intercalated between graphite layers in molecular convection–diffusion, replacing some of the sulfuric acid molecules, to Mn2O7–H2SO4–GIC. In the third step, Mn2O7 is decomposed by heat, and oxygen atoms are generated to oxidize the defects in the graphite layer to PGO. This work provides a more plausible explanation for the mechanism of oxidizing reaction in the preparation of GO by the Mn2O7–H2SO4 oxidation method.

4. Methods

4.1. Materials

The graphite flakes were obtained from Qingdao Tianheda Graphite Co., Ltd. The concentrated sulfuric acid, potassium permanganate, and concentrated hydrochloric acid were from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. The sodium nitrate was from Taicang Hushi Reagent Co., Ltd. The hydrogen peroxide (30%) was from Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

4.2. Hummers Method of GO Preparation

One gram of sodium nitrate was slowly added to 70 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid until complete dissolution. Then, 2.0 g of flake graphite was added and stirred for 30 min at 0–4 °C in an ice bath. Potassium permanganate (8.0 g) was added and stirred for 30 min. Then, the temperature was increased to 35–45 °C and stirred for 300 min. Two hundred forty milliliters of deionized water was added several times and stirred at 65–75 °C for 120 min. After the mixture was heated to 95 °C for 5 min, 25 mL of (30%) hydrogen peroxide solution was added and the solution was stirred for 30 min. Then, 40 mL of hydrochloric acid solution was added in the mass ratio of 5% and the mixture was stirred for 30 min. Afterward, vacuum extraction and filtration were performed while hot. The filter cake was then washed with deionized water and centrifuged until the pH value of the GO solution became 5–6. Finally, the solution was vacuum dried at 65 °C to obtain solid GO.

4.3. Monitoring the Oxidation Reaction by Photographs and UV–vis Spectra

To directly observe the morphology of the reaction solution during the preparation of GO, an optical camera was used to take photographs of the reaction solution at each reaction stage and record the reaction phenomena. A small amount of reaction mixture solution was taken out and put on a glass slide. Then, this glass slide was covered with another glass slide to ensure that the middle liquid film was without bubbles. The film was immediately observed under an optical microscope (500×) and recorded with a camera. UV–vis was performed to characterize the change in manganese ion in the solution. Two milliliters of the mixture was taken at each reaction sampling point and diluted to 100 mL with sodium nitrate/concentrated sulfuric acid solution, 1 g of sodium nitrate/70 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid, or deionized water, respectively. Then, scanning spectra were performed within the wavelength range of 200–800 nm. If the absorption peak intensity exceeded the instrument measurement range, the solution was diluted to an appropriate concentration using an appropriate diluent.

4.4. Instrumentation

Light micrographs shown in Figures 1–6 were acquired using a Nikon ECLIPSE CiPOL microscope equipped with Nikon DIGITAL SIGHTDS-Fi1c. The transmit mode was used with a white incandescent light source. The lenses used were 50× objective lens and 10×/0.45 eyepiece. UV–vis spectra were acquired using a SHIMADZU UV-2450 UV–vis spectrophotometer. XRD pattern was acquired using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kr radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). SEM and EDS were acquired using ZEISS Sigma 300. FITR spectroscopy was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 in situ infrared spectrometer and a potassium bromide tablet.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 21968036), the Science and Technology Resources Open Sharing Platform Project of Shaanxi Provincial (Grant 2019PT-18), the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund of Yulin University (Grant 18GK27), the Shaanxi Key Laboratory Project (Grant 19JS070), and the Science and Technology Project of Yulin City (Grant CXY-2021-106-01).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Zhu Y.; Murali S.; Cai W.; Li X.; Suk J. W.; Potts J. R.; Ruoff R. S. Graphene and Graphene Oxide: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3906–3924. 10.1002/adma.201001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano D. C.; Kosynkin D. V.; Berlin J. M.; Sinitskii A.; Sun Z.; Slesarev A.; Alemany L. B.; Lu W.; Tour J. M. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. 10.1021/nn1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dave S. H.; Gong C.; Robertson A. W.; Warner J. H.; Grossman J. C. Chemistry and Structure of Graphene Oxide via Direct Imaging. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7515. 10.1021/acsnano.6b02391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Ren G. Review on Preparation Methods and Application of Graphene Oxide in Anticorrosive Thermal Conductivity Coatings. Corros. Prot. 2021, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gu L.; Ding J.; Yu H. Research in Graphene-Based Anticorrosion Coatings. Prog. Chem. 2016, 28, 737–743. [Google Scholar]

- Geim A. K.; Novoselov K. S. The Rise of Graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. 10.1038/nmat1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie B. C. Surlepoids Aatomique du Graphit. Ann. Chim. Phys. 1860, 59, 466–472. [Google Scholar]

- Staudenmaier L. Verfahren Zur Darstellung Der Graphits. Ber. Deut. Chem. Ges. 1898, 31, 1481–1487. 10.1002/cber.18980310237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hummers W. S.; Offeman R. E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. 10.1021/ja01539a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovtyukhova N. I.; Ollivier P. J.; Martin B. R.; Mallouk T. E.; Gorchinskiy A. D.; et al. Layer-by-layer Assembly of Ultrathin Composite Films from Micron-sized Graphite Oxide Sheets andPolycations. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 771–778. 10.1021/cm981085u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. H.; Yu Y.; Li Y. Z.; Xu T.; Zhi J. F. A Hybrid Reduction Procedure for Preparing Flexible Transparent Graphene Films with Improve Delectrical Properties. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 18306. 10.1039/c2jm31048a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimiev A. M.; Eigler S.. Graphene Oxide: Fundamentals and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2016 10.1002/9781119069447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G.; Chhowalla M. Chemically Derived Graphene Oxide: Towards Large-Area Thin-Film Electronics and Optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2392–2415. 10.1002/adma.200903689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. Y.; Zhang D. Aqueous Colloids of Graphene Oxide Nanosheets by Exfoliation of Graphite Oxide without Ultrasonication. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2011, 34, 25–28. 10.1007/s12034-011-0048-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Huang J.; Hou W.; Chen J. Preparation of Large-area Graphene Materials by Stitching. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2018, 49, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. H.; Wang Z. M.; Yang X. J.; Ooi K. Intercalation of Organic Ammonium Ions into Layered Graphite Oxide. Langmuir 2002, 18, 4926–4932. 10.1021/la011677i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó T.; Etelka T.; Erzsébet I.; Imre D. Enhanced Acidity and pH-dependent Surface Charge Characterization of Successively Oxidized Graphite Oxides. Carbon 2006, 44, 537–545. 10.1016/j.carbon.2005.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo Y.; Miyabe T.; Fukutsuka T.; Sugie Y. Preparation and Characterization of Alkylamine-intercalated Graphite Oxides. Carbon 2007, 45, 1005–1012. 10.1016/j.carbon.2006.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L.; Xu Z.; Liu Z.; Wei Y.; Sun H.; Li Z.; Zhao X.; Gao C. An Iron-based Green Approach to 1-h Production of Single-layer Graphene Oxide. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5716 10.1038/ncomms6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy K.; Kim G. S.; Kim S. J. Graphene Nanosheets: Ultrasound Assisted Synthesis and Characterization. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013, 20, 644–649. 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V. K.; Shukla A.; Patra M. K.; Saini L.; Jani R. K.; Vadera S. R.; Kumarl N. Microwave Absorbing Properties of a Thermally Reduced Graphene Oxide/Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Composite. Carbon 2012, 50, 2202–2208. 10.1016/j.carbon.2012.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voiry D.; Yang J.; Kupferberg J.; Fullon R.; Lee C.; Jeong H. Y.; Shin H. S.; Chhowalla M. High-quality Graphene via Microwave Reduction of Solution-exfoliatedGraphene Oxide. Science 2016, 353, 1413–1416. 10.1126/science.aah3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales G. M.; Schifani P.; Ellis G.; Ballesteros C.; Martínez G.; Barbero C.; Salavagione H. J. High-quality few layer graphene produced by electrochemical intercalation and microwave-assisted expansion of graphite. Carbon 2011, 49, 2809–2816. 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Chen W.; Song D.; Lai B.; Sheng Y. Y.; Yan L. F. Solvent-free Mechanochemical Synthesis of Mild Oxidized Graphene Oxide and Its Application as Novel Conductive Surfactant. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 7057–7064. 10.1039/C9NJ00529C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shao G.; Lu Y.; Wu F.; Yang C.; Zeng F.; Wu Q. Graphene Oxide: The Mechanisms of Oxidation and Exfoliation. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 4400–4409. 10.1007/s10853-012-6294-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan R.; Yuan J.; Wu Y.; Chen L.; Zhou H.; Chen J. Efficient Synthesis of Graphene Oxide and The Mechanisms of Oxidation and Exfoliation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 416, 868–877. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.04.181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. R.; Shi G. S.; Tu Y. S.; Fang H. P. High Correlation between Oxidation Loci on Graphene Oxide. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10190–10194. 10.1002/anie.201404144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer D. R.; Park S.; Bielawski C. W.; Rouff R. S. The Chemistry of Graphene Oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 228–240. 10.1039/B917103G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trömel M.; Russ M. Dimanganheptoxid zur selektiven Oxidation organischer Substrate. Angew. Chem. 1987, 99, 1037–1038. 10.1002/ange.19870991009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimiev A. M.; Tour J. M. Mechanism of Graphene Oxide Formation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 3060–3068. 10.1021/nn500606a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer D. J. Evidence for the Existence of the PermanganylIon in Sulfuric Acid Solutions of Potassium Permanganate. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1961, 17, 159–167. 10.1016/0022-1902(61)80202-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson S.; Frishberg C.; Frankl G. Thermodynamic Properties of The Graphite-bisulfate Lamellar Compounds. Carbon 1971, 9, 715–723. 10.1016/0008-6223(71)90004-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu G. B.; Li P.. Inorganic Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, 2019; pp 242–243. [Google Scholar]

- Dimiev A. M.; Bachilo S. M.; Saito R.; Tour J. M. Reversible formation of ammonium persulfate/sulfuric acid graphite intercalation compounds and their peculiar raman spectra. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7842–7849. 10.1021/nn3020147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K. R. Oxidation by Mn207: An Impressive Demonstration of The Powerful Oxidizing Property of Dimanganeseheptoxide. J. Chem. Educ. 1982, 59, 973–974. 10.1021/ed059p973.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhabiev T. S.; Denisov N. N.; Moiseev D. N.; Shilov A. E. Formation of Ozone During The Reduction of Potassium Permanganate in Sulfuric Acid Solutions. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2005, 79, 1755–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Gao W.; Wu G.; Michael T. J.; David A. C.; Rangachary M. J. K. B.; Eric L. B. C. G.; Pulickel M. A.; Karren L. M.; Andrew M. D.; Piotr Z.; et al. Ozonated Graphene Oxide Film as A Proton-exchange Membrane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3588–3593. 10.1002/anie.201310908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimiev A. M.; Kosynkin D. V.; Alemany L. B.; Chaguine P.; Tour J. M. Pristine Graphite Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2815–2822. 10.1021/ja211531y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]