Abstract

The highly infectious novel coronavirus (COVID-19), officially SARS-CoV-2, was discovered in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread to the rest of the world in 2020. Frontline workers had frequent interactions with COVID-19-infected and -uninfected patients. Therefore, the study’s overarching goal is to investigate the experiences of frontline healthcare professionals in dealing with the COVID-19 health emergency. The study used a qualitative research approach with a phenomenological research design. Using a purposeful sampling approach, the researcher collected data from 24 participants. The MAXQDA program was used to analyze the data, and followed Collaizzi’s 7-step technique. All ethical standards were met to perform the study. Four main themes and ten subthemes were derived from the 24 in-depth interviews. The key themes were emotional suffering, intense physical pressure, social connection deterioration, and the inability to manage family obligations. Extensive social, emotional, and organizational aid is necessary to assist individuals in dealing with this unprecedented health crisis. Furthermore, the government and non-governmental organizations must work together to come up with the right policies to limit the COVID-19 burden on frontline health professionals.

Keywords: phenomenological study, COVID-19 pandemic, frontline healthcare workers, health crisis, policy implications

What do we already know about this topic?

The COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide health catastrophe that has burdened everyone physically, financially, emotionally, socially and in other ways, even if they did not contract the disease.

How does your research contribute to the field?

During a pandemic, healthcare professionals perform key responsibilities to save the lives of people under their care. Little scholarly research has focused on the experiences of the frontline health professionals in developing countries trying to care for COVID-19 patients with limited resources and capacities. This phenomenological investigation will serve as a reference for scholars and policymakers in designing support for frontline healthcare professionals in future pandemics.

What are your research’s implications for theory, practice, or policy?

The findings suggest that providing counseling, arranging entertainment facilities, supplying adequate safety gear, and minimizing discrimination in hospitals are crucial for the betterment of the condition and performance of frontline healthcare professionals in a pandemic emergency. The findings of this study can be a benchmark for policymakers and government and non-government bodies to make policies which look after frontline healthcare workers.

Introduction

The highly infectious novel coronavirus (COVID-19), officially SARS-CoV-2, was discovered in Wuhan, China, and quickly spread to the rest of the world in 2020.1,2 In March 2020, the World Health Organization declared a pandemic. The virus’s high initial death rate was only the most visible of a whole complex of impacts on human society. Victims—and those who worked with them—faced severe stigma, financial difficulty, and mental health issues, in addition to physical damage.

Healthcare professionals endured some of the most severe consequences of COVID-19 for those who were infected. They were on the frontline, in direct contact with patients in hospitals. 3 Due to the overwhelming demand for their services, frontline health workers were under great pressure from the start of the pandemic. COVID-19 patients were added to their workload of other persons needing care for other infections and conditions, in large numbers, often with little increase in the number of colleagues who could help them, who themselves were falling ill in large numbers. In addition to tremendous overwork came the added mental pressure of fear arising from the high probability of contracting COVID-19: a fatal disease about which we knew little, least of all how to cure or contain it. 4 It was known that close physical contact, even breathing the same air as an infected person, could pass the virus. Yet, while everyone was being told “socially distance,” frontline workers were breathing the same air of hundreds of infected people, touching them and picking them up, every day. Often, they were working without sufficient protective equipment like “PPE” and enduring social stigma after work due to the fear of neighbors, friends, relatives, and housemates that they might bring the virus with them to their communities. 5 Moreover, frontline workers’ health and quality of life deteriorated, as their shifts became longer and longer and less predictable according to the dictates of the emergency and the collapsing health service. 6 Anxiety, fear, and trauma are common at the time of a health emergency, and a global health catastrophe has a pervasive nature that seems to disrupt everything else. Furthermore, the severe workload, social stigma, lack of adequate PPE, death of colleagues, and absence of close relatives make frontline workers even more susceptible to mental and emotional stress. During this worldwide health catastrophe, they are experiencing loneliness, exhaustion, panic, as well as anxiety. In addition, the psychological responses of individuals during an infectious disease outbreak also contribute to the spread of sickness and the development of emotional misery. Even a normal reaction to the COVID-19 crisis impedes mental health and well-being. 7

Globally, health and social systems were straining to keep up because of this uncommon virus that attacked everywhere at once. The effect of the COVID-19 health menace was particularly challenging in fragile low-income countries, where health and social systems were already barely sufficient before the crushing demands of the pandemic were added. In Bangladesh, wave after wave of different variants of the COVID-19 virus has created a feeling in the health sector of being under unremitting attack. According to several national media reports, 73 physicians, including some well-known physicians, died of COVID-19 in Bangladesh between August 2019 and August 2020. The Bangladesh Medical Association (BMA) stated that health practitioners accounted for around 10% of all infections in the disease’s early stages. 8 Due to their exceptional and valiant service, they are in the most exposed position and in the greatest danger. It is vital to understand the experiences of medical professionals in the midst of the COVID-19 health crisis in Bangladesh. To successfully assist healthcare workers, the most valuable assets in healthcare systems’, we must first understand their concerns and needs. Therefore, the pressing questions were the followings:

What are the forms of stress and trauma commonly experienced by frontline health workers?

What effects do such stress and trauma have on the day-to-day activities, both at work and at home, of frontline health workers?

How do they cope with psychosocial stress and trauma?

This research attempted to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected frontline health workers in their professional and personal lives. This study sought data about the lived experiences of Bangladeshi healthcare workers during the COVID-19 crisis directly from the workers themselves. Expectantly, by vicariously “listening to” these heroes, policymakers who read this report can make policies that will provide support to the frontline health workers to alleviate their miseries instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objectives

The general objective of this study is to examine the experiences of frontline healthcare providers during the COVID-19 health crisis in Bangladesh. The specific objectives are:

(a) to explore the sources and impression of stress and trauma of the frontline health workers instigated by the COVID-19 crisis; and

(b) to identify the challenges of meeting family responsibilities while providing their professional services to patients in a situation of recurrent public health emergency.

Methods

Study Design

This study used a qualitative technique based on non-numerical data. The qualitative method helps the researcher acquire deeper insights into the experiences of subjects. Hence, to better understand the experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 catastrophe, the research employed a qualitative approach. Qualitative techniques of data collection and analysis that can assist a researcher to explore social issues include grounded theory, case studies, ethnographic, historical, phenomenology, etc.

Phenomenological research particularly focuses on the lived experiences of the study subjects. New meanings for such experiences may be generated as a result of phenomenological research. 9 The phenomenological approach tries to capture the essence of a phenomenon by looking at it through the eyes of people who have experienced it. 10 Living with the COVID-19 pandemic and working with its victims is a new phenomenon. Thus, the challenges frontline health workers faced were unprecedented. So, the researchers used a phenomenological design to study the experiences of physicians and nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. This way, the researchers could capture the essence of what the COVID-19 pandemic was like for them through the eyes of people who had experienced it.

The study was conducted in the Sylhet City Corporation area. Sylhet is home to a number of hospitals. This city was one of the hotspots for the COVID-19 virus. In addition, the first death of a doctor in Bangladesh because of the COVID-19 infection was in Sylhet. Thus, Sylhet was purposively selected as the site for this study.

Data Collection

Phenomenological research implies collecting data on the lived experiences of the participants. Therefore, the researcher had to listen to people who had relevant experiences. To do this, the researcher selected physicians and nurses as participants, purposively to obtain information-rich samples. The demographic information of the research participants is presented below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Information of the Participants.

| Variables | Groups | Percentage (≈%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 33.00 |

| Female | 67.00 | |

| Age | 26-30 | 37.50 |

| 31-35 | 12.50 | |

| 36-40 | 17.00 | |

| 41-45 | 25.00 | |

| 46+ | 08.00 | |

| Marital status | Married | 25.00 |

| Unmarried | 75.00 | |

| Type of job | Physician | 42.00 |

| Nurse | 58.00 | |

| COVID-19 infection history | Ever infected | 83.00 |

| Never infected | 17.00 |

Saturation occurred with 24 in-depth interviews. Saturation occurs when no new data is discovered from the last participant in the sample, implying that the researcher “has the story” and that more participants will only repeat it. Given saturation, the researcher has enough data from which category attributes can be constructed. 11 Data was gathered at the participants’ preferred times and places. The interviews were mostly conducted in the offices (chambers/duty stations) of the physicians and nurses. The participants were selected based on the inclusion criteria listed below.

Participants were purposively selected according to the following criteria:

i. willingness to share experience and participate in the study;

ii. having a stable physical condition; and

iii. providing direct healthcare to patients.

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals are working hard to make sure patients get the care they need. Therefore, open-ended questions were used to allow participants to supply a large amount of data in a short time, in their own concept of order of importance. This proved to be a most satisfactory strategy. The checklist questions have been presented below (Table 2).

Table 2.

Checklist Questions for the Participants.

| Sl. no. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | What are the things that make you afraid of working in the hospital? |

| 2. | What safety precautions has your institution implemented? |

| 3. | Do you feel stressed during the COVID-19 pandemic? Explain. |

| 4. | What traumatic events did you go through when the pandemic was going on? |

| 5. | How do you feel when you learn that one of your coworkers, supervisor, or subordinates has been infected with the virus or has died as a result of it? |

| 6. | What are the main challenges in your professional and personal life in this situation? |

| 7. | What steps do you take to protect your family members against the coronavirus? |

| 8. | What measures do you take to maintain isolation from your family members during the COVID-19 pandemic? |

| 9. | How do you maintain your family responsibilities during isolation? |

| 10. | How does COVID-19 affect your social relationships, such as with your friends, neighbors, etc.? |

However, getting access to participants during the COVID-19 outbreak was challenging. The researcher visited the wards and offices as well as made appointments over the phone. In this respect, the researcher communicated frequently in order to schedule appointments for participants at their convenience. The data was collected between June 2021 and August 2021. The interviews were conducted entirely in Bengali. The data was then translated into English by the researcher and recorded from notes and audio soundtracks in a Microsoft Word document. To ensure that the main concepts were preserved in the participants’ original language, the thesis supervisor, who is a PhD holder, extensively cross-checked the field data (in Bengali) and the transcribed data (in English).

Data Analysis

The researcher meticulously transcribed and reexamined the interviews to verify that the data was free of errors. The qualitative data was analyzed and processed using the MAXQDA program and the Colaizzi 7-step techniques (direct quotations from the participants). The 7 steps include: “1. studying all of the components of the interviews, such as verbatim; 2. identifying major utterances; 3. devising connotations; 4. arranging the selection of interpretations into clusters of categories; 5. incorporating the clusters of categories into an exertion characterization; 6. constructing the basic framework of the phenomenon; and 7. meeting the people who took part in the study.” 11

The researchers of this study carefully reviewed all of the verbatim transcriptions, and, after meticulously extracting themes from the data, they returned to the participants to get their verification. This strategy also increased participants’ confidence in participating, knowing that their information would not be misunderstood or mischaracterized. The 7-step techniques given by Colaizzi (1978) 12 assisted the investigators in avoiding inserting their own perceptions of an incident and giving proper weight to the participants’ understanding and experiences. Colaizzi’s distinctive 7-step method provides a thorough analysis, with each phase remaining close to the data.11,13 The interviewees’ words and phrases were entered into the MAXQDA program. Data was interpreted and coded. After analyzing the data, themes and subthemes were extracted.

Measures to Enhance the Validity and Reliability

Initially, the interview checklist was developed based on the literature review and the study objectives. The supervisor then reviewed the interview checklist to determine its clarity and appropriateness, and relevant comments on the checklist format and structure were made. The required modifications were made and integrated into the interview checklist in response to the comments. In addition, the Guba and Lincoln criteria, which are used to evaluate the results’ overall quality, were fulfilled. 14 Therefore, the researcher used recording equipment and transcribed digital files to improve the dependability of comprehensive field data. In order to accomplish the conformability, the data was submitted to the supervisor as soon as it was collected from the field. This was done in order to ensure that it was accurate. In addition, the data collection and analysis process was presented to the faculty members (in the courses titled “Data collection and analysis (for the thesis students)” and “Draft thesis submission and presentation”) of the Department of Social Work, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, who are experts in qualitative research. For transferability of the research, at the completion of the data collection for each in-depth interview, the researcher briefly conveyed the general comprehension of the statements, which was validated by the interviewees. Moreover, an overview of the research outcomes, together with quotations, was sent to 5 participants to assess if the investigators had accurately recorded their experiences. Also, the researcher validated their results by showing the data to 3 individuals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria but did not take part in the current study. Additionally, to ensure credibility, the researchers did their utmost to collect the data with adequate time.

Results

Based on the 24 in-depth interviews, a total of 4 themes and 10 subthemes regarding healthcare workers’ experiences amid the COVID-19 health hazard were extracted (Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes and Subthemes Extracted From the Data Analysis.

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| Emotional suffering | Fear of being infected with the COVID-19 virus and infecting family members |

| Trauma due to the deaths of colleagues and family members | |

| Limited movements outside of the hospital and home | |

| Intense physical pressure | Altered work schedule |

| Little rest or free time | |

| Stress from working in the new COVID-19 situation | |

| Social connection deterioration | Social stigma from the neighbors, friends and relatives |

| Isolation from family members | |

| The inability to manage family obligations | Unable to care for children and elderly members |

| Inability to spend adequate time with family members |

Emotional Suffering

The COVID-19 pandemic has extensively impacted the mental health and wellbeing of physicians and nurses. The dread of becoming infected with the virus and infecting family members preoccupied them. Furthermore, the deaths of colleagues and family members, as well as restricted travel outside of the hospital and home, had a profound effect on mental health.

Fear of being infected with the COVID-19 virus and infecting family members

At the beginning of the pandemic, most physicians and nurses were afraid of becoming infected with the virus because its effects were unknown, but the risk of death seemed high. They feared the consequences for their families if they became ill or died. Most of them believed that they had no choice but to fulfill their responsibilities at hospitals but that the easy transmittablity of the virus created a far higher risk to the health of their family members than normal hospital work did. Yet they could not avoid this risk because refusing to serve, and thereby losing their jobs, carried equally severe economic and physical consequences for their families.

I’ve been working in a hospital for five years. I’ve never seen such a high patient load as I’ve seen recently. The COVID-19 virus has infected even physicians. My family will have to suffer if I become sick and die as a result of the illness (Participant no. 04).

A research participant, who has an elderly mother, shared her views on the issue.

My 80-year-old mother is with us. She had pneumonia before, and I was very worried if she got the COVID-19 virus from me. I’m feeling a lot of guilt for my mother since I can’t quit my job to rescue her (Participant no. 22).

Trauma due to the deaths of colleagues and family members

At almost unprecedented speed, the virus traveled from China to other countries. Victims got lung infections from the virus. There was no medicine to destroy the infection, as every country seemed to focus solely on preventing infection by social isolation or, later, by vaccines, although medicines were found that limited symptoms and saved lives. This was discovered by trial and error as the pandemic ravaged nations, over time. During the pandemic, the physicians and nursing staff worked in hospitals that were hotspots for COVID-19 infection. Infection among coworkers was widespread during the pandemic, and their eventual deaths devastated their colleagues. However, several participants’ family members became sick as a result of it and suffered enormous difficulties, particularly the older members of the family.

I started worrying when I heard that my colleague had died as a result of COVID-19 and that his family had also been affected. I was terrified that my sickness might cause my family to become sick. If any of my family’s elderly became ill, we’d be in grave danger (Participant no. 07).

Field data also revealed that the bereavement of family members caused trauma in the study participants.

During the pandemic, one of my uncles became infected with the COVID-19 virus and was critically ill. His family and I worked extremely hard to get him an ICU bed, but, because of a lack of ICU beds in the city, he needed to go to Dhaka. However, it was too late, and he died on the way (Participant no. 12).

Limited movements outside of the hospital and home

Because of the workload, lockdown, and quarantine, health care professionals were unable to move independently. They were required to restrict themselves to hospital wards and home. Their lives became monotonous and joyless.

My life has been stuck between the hospital and the home. I barely remember any time when I could just go outside with my friends and family to have fun during the pandemic. I am really tired of my job and of the pandemic (Participants no. 01).

Intense Physical Pressure

The pandemic caused significant challenges in the workplaces of healthcare workers. During the public health catastrophe, they were swamped with work. Previously, they had worked on a specific work schedule, but the pandemic caused the authorities to modify the timetable regularly due to the heavy burden of infected patients. Moreover, they had little time to relax in this circumstance, and the burden generated stress because this high pressure work for longer periods was something unpleasant which they had never had to work out ways to deal with.

Altered work schedule

Previously, healthcare personnel, particularly nurses, had kept a precise roster at the hospital, which limited their work time and interspersed it with time off to recuperate. They had worked overtime when there was an emergency, but this was exceptional. Now the emergencies were constant, one after the other, so shifts got longer and longer and rest time almost disappeared, which decimated their family life and duties.

Earlier, I had duty in the wards during the day. But, in recent times, my duty time has been rapidly changing. Now, I am assigned to the wards at night. It causes some physical problems, such as headaches, for me (Participant no. 18).

Little rest or free time

Health workers had enough time to relax before the pandemic. They used to eat at regular intervals. However, the unexpected occurrences left little time for relaxation, and their lives were overburdened. Working in a hospital is often high-pressure: it is not easy saving lives and sick people often get into crises requiring rapid action. Yet the pandemic totally exhausted frontline workers.

Crises were constant. Pressure was constant. Not only were the hours long and rest time gone but every hour took all of the workers’ energy and capacity. They had been helpers and carers but now they lived more like soldiers in the trenches, in constant danger against which they must constantly struggle to their personal limits to survive, with no life of their own.

Because of the extreme burden, we were unable to rest, eat, sleep properly, or make phone calls to relatives. Working on our feet all day exhausts and weakens us, both physically and emotionally (Participant no. 15).

The collected data demonstrated that the participants functioned like a well-oiled machine throughout the pandemic.

I’m constantly working at the hospital. It’s as if I’m a machine. So, when I get home from my duties, I fall asleep immediately and am unable to communicate with my family members (Participant no. 22).

Stress from working in the new COVID-19 situation

In recent years, such pandemics have been unusual in Bangladesh. The high infection and mortality rates distressed the physicians and nurses. It is difficult to adapt to a pandemic situation with no established treatment. They were, however, always under threat of death by the infection.

The excessive workload while wearing PPE is really problematic. Having meals now takes time as well. Since it takes time to remove PPE and thoroughly sanitize, I have to spend a plethora of time (Participant no. 24).

The pandemic has resulted in several stressful and time-consuming situations for healthcare personnel.

Before the pandemic, when I left the hospital for home, my children would rush up to me and hug me. But the situation has changed; now, when I get home, I must remove my PPE and cleanse myself completely before seeing anyone. (Participant no. 03).

Social Connection Deterioration

The pandemic has also had a consequence on people’s social relationships, with healthcare providers being the worst sufferers. They were stigmatized and shunned as possible COVID-19 transmitters. Furthermore, when they had COVID-19 symptoms or dealt with patients who had the symptoms, they had to keep themselves separated in the form of quarantine.

Social stigma from the neighbors, friends, and relatives

During the outbreak, the physicians and nurses were in a terrible situation. They were labeled COVID-19 spreaders. The nature of their job caused this: they were innocent. They and their family members were also shunned by neighbors and relatives for these reasons. The attitude and behavior of community people made them feel isolated and harmed them emotionally. A participant mentioned his feelings in the following way:

During the pandemic, all my family members were almost kept locked inside our house. Even the other families in the building avoided making social contact with them even while I stayed in isolation and could not pass them any virus. No one even asked them how they were doing while I was away. Even my landlord gave me an ultimatum to vacate the property, although it was really difficult for me to find another place to live. (Participant no. 13).

Because of the stigma, the participants’ acquaintances even barred them from participating in social get-togethers.

My friends used to call me on weekends, but they now avoid me. During the Eid holiday, they planned a barbecue- but did not invite me. It was difficult for me to believe that they had the celebration without me (Participant no. 08).

Isolation from family members

Most of the time, health professionals had to stay separated from their family members, during the outbreak. They remained isolated when they experienced COVID-19 symptoms or when they had to work with patients who had COVID-19 symptoms. They were unable to meet with their family members or participate in family activities, which left them emotionally unsettled. During data collection, one participant stated:

During this outbreak, I had to stay away from my family. I had no direct communication with my family during this period. When I tested positive, I I went through the days with trepidation, thinking that each would be the last day of my life. (Participant no. 12).

The field data showed evidence of discrimination in the workplace.

It seemed to me that there were organizational inequities among hospital staff during the pandemic. There was a disparity in the assistance supplied by the Government during the early phases of the pandemic. However, being separated from my family members and subjected to such treatment made me helpless (Participant no. 19).

The Inability to Manage Family Obligations

Frontline staff were unable to care for family members, particularly youngsters and the elderly. They were unable to spend enough time with other family members who did not need special care either. Frontliners’ family bonds emerged from the pandemic, after 2 years of neglect, in tatters.

Unable to care for children and elderly members

It was difficult for the physicians and nurses who had children and elderly family members, such as their parents. On a daily basis, they were emotionally detached. During the pandemic, female employees experienced a great sense of estrangement from their children.

As physicians, we are aware of a number of risk factors for COVID-19 transmission. As a result, we were unable to interact with our children and older relatives. Being separated from them was really difficult for them and for us. Children get impatient and frustrated, while the elderly become concerned (Participant no. 05).

Healthcare professionals did not get time to even call such family members as they were always dealing with a crisis. Therefore, they were always worried about their children at home.

I have a 5-year-old daughter. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, I used to take care of my child by revising her school lessons and feeding her on time. However, the pandemic has limited my ability to do so. Is it feasible for a 5-year-old child to survive without her mother? (Participant no. 21).

Inability to spend adequate time with family members

As a family member, it is a responsibility to spend enough time with the spouse and other family members. The COVID-19 outbreak has curtailed this responsibility, making physicians and nurses, as well as their families, vulnerable. Furthermore, they received the impression that they would no longer be able to devote time to their loved ones. These relationships were all damaged to some extent.

In normal times, we would often go outside, enjoy supper at a nice restaurant, or watch movies together. COVID-19 stopped all that. Everyone was on his/her own. A medical practitioner did not even get a ration of quality time with his/her family (Participant no. 5).

Ethical Considerations

Throughout this research, strict research ethics have been followed. The researchers scrupulously adhered to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent revisions. Except for academic criteria, data has not been exchanged for any other purpose. Due to high propaganda about COVID management, the government restricted giving formal opinion except for concerned people. Then again, the exchange of consent forms increases the risk of transmission of COVID-19 infection. Hence, verbal informed consent has been obtained from the participants, voluntary involvement was assured, anonymity and secrecy of the participants and data were maintained very carefully. In the study, a nonjudgmental mindset was preserved. The participant’s privacy was protected. In addition, the identities of the participants remained anonymous.

Discussion

The present study intended to explore the lived experiences of frontline healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The infection and death rate due to the virus had a multifaceted impact on people’s lives. The SARS-CoV-2 virus disrupted people’s physical and mental health all around the world, regardless of gender, ethnicity, profession, or other factors, and it is still rapidly spreading 15 albeit in a more benign form. Bangladesh is also hit by its frequent waves and has a serious threat from the different variants of the virus from different countries. The pandemic had a direct impact on medical professionals as they delivered superior healthcare to the public while they endured the worst conditions they had ever experienced.

The outbreak has had a direct impact on the health and wellbeing of frontline medical professionals in Bangladesh, like everywhere else. Stress, anxiety, and fear of infection and death were prevalent during the pandemic among both health professionals even more so than their patients. Previous research findings also showed that pandemics generated traumatic experiences in humans, leading to PTSD and other serious mental problems, far beyond the experience of the disease itself.16-18

Health professionals, also known as frontliners, have been working dedicatedly throughout this global health crisis. Eftekhar Ardebili et al 19 also found that stress and anxiety were prevalent among healthcare professionals as a result of this pandemic. They had a feeling of helplessness, hopelessness, and powerlessness in the pandemic, as well as a lack of control over this new situation. They were also worried about their own health as well as the health of their family and friends, particularly the elderly and sick. In line with the findings of the study by Swazo et al, 20 our study also found that physicians and nurses often had to do their duties while wearing minimal PPE at hospitals. In addition, they had to keep their responsibilities to their families despite the risk of infection.

The new global health hazard also puts an extra workload on health workers. Our study discovered that, due to the alteration in shifts in the work schedule, the front-liners felt stressed, which is consistent with the study of Coto et al. 21 Besides, they were frightened that they might spread the virus to their family and friends. They required the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE), training, etc.; however, they lacked safety precautions, which made them susceptible when the crisis erupted. Nyashanu et al 22 argued that the shortage of PPEs, insufficiencies in COVID-19 preparedness, and lack of scope for maintaining social distancing were among the reasons for the stress and fear affecting healthcare personnel, in addition to the health catastrophe itself. According to Hossain et al 6 healthcare providers were stressed and traumatized due to a lack of required safety equipment, fear of infection, and lack of COVID-19 management coordination. Such stress, mental trauma, lack of needed resources, and management failures led to a decline in work competence among these professionals. Furthermore, the relationships among the health professionals broke down, which had a negative influence on work productivity. Bennett et al 23 found that the existing interpersonal relationships between senior management and staff, the common risk of getting infected with whatever they were treating, which health workers always face, and relative equality in the workplace triggered productivity. Mehta et al 24 found that the pandemic had generated inequality in the workplace. Thus, the pre-pandemic recipe for success was undermined, and conflict began to replace cooperation. Lotta et al 25 discovered that health service providers were forced to adapt to this altered work environment during the pandemic, which is comparable to the findings of our study. They had to perform highly interactive duties with patients without required social distancing, because there was no other option but to treat the patient.

The present findings were also consistent with those of Vindrola-Padros et al 26 which showed that their tireless duties during the pandemic and frequent changes in the guidelines caused excessive pressure on the frontline workers in the hospitals. The pandemic has revealed that the incorrect size of the PPEs and heating issues with them have caused discomfort at work among the workers. This and similar “surprises” spurred burnout, anxiety, and stress. Healthcare providers, according to Liu et al 27 were overwhelmed by the pandemic, which placed them under a lot of stress. Morgantini et al 28 also identified the relationship between job-related stress and workload, along with inadequate organizational support, and burnout among healthcare workers.

The researchers found that health professionals felt severely shocked by the high death rate, which they had never encountered in normal hospital work. The physicians and nurses had to support their COVID-19 patients emotionally. Sterling et al 29 investigated how, in addition to their typical caring activities, healthcare staff watched patients for COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, shortness of breath, and so on, and generally tended to their patients’ mental wellbeing. Our study discovered that such unprecedented events and challenges have a significant influence on healthcare workers’ professional and personal lives. Therefore, it is clear that they are more susceptible to COVID-19 illness than the general public. Some studies also stated that the fear of infection had traumatized them, but those studies did not investigate the extent and forms of stress and trauma. 30

However, there are other issues that healthcare professionals confront on a daily basis, such as balancing between family and job responsibilities, that have not been addressed in previous studies. Another significant finding of this study is that workers got no trade-offs in family responsibilities for their drastic boost in work responsibilities. They were still obligated to perform child care, home management, and elder care at home plus spend almost all day at work, giving maximum energy every hour with rare respite, to cope with back-to-back COVID-generated crises. The burden was beyond their capacity.

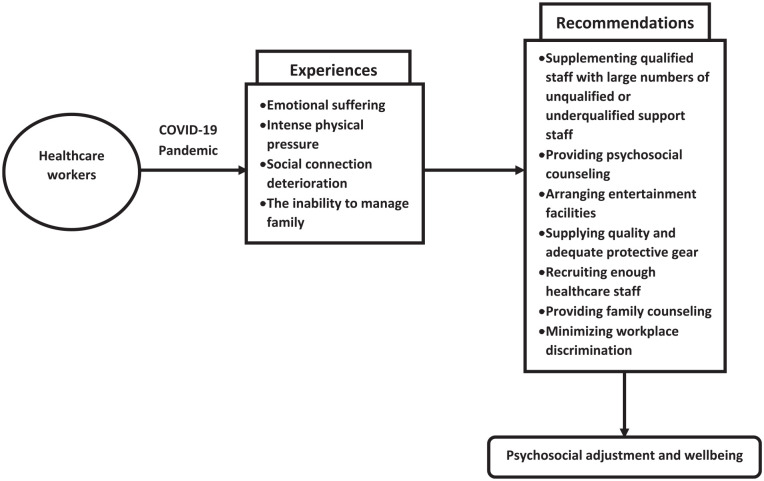

In future pandemics, hospitals will have to provide extra care for their staff to ensure the best care to their patients. They need to maintain large paramedical, student and volunteer cadres in normal times so that they will have them in times of crisis. This will allow extra support to the qualified staff while on duty and replacement of qualified staff for frequent rest periods. Patients will, in the long-term, be more grateful for sincere care from rested but unqualified staff than substandard care from burnt-out, frazzled, half-dead experts. It is crucial to provide counseling to both healthcare employees and their family members. The arrangement of entertainment facilities when they are isolated can help to mitigate the negative mental consequences of the protective measure. Furthermore, it is absolutely essential to provide enough safety equipment and to recruit a sufficient number of healthcare workers. It is also urged that efforts be made to reduce discrimination in hospitals and clinics in order to promote a conducive working environment. Hence, the government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should work together to deal with the global health crisis. Their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic have been shown in the diagram below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experiences and Psychosocial Adjustment and Wellbeing of the Health Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Limitations of the Study

The pandemic itself and control measures like lockdowns, quarantines, isolation of people and places, etc. have been the major limitations on data collection for this study. Much data could not be collected when it was most needed and had to be collected from people’s memories and from records. In-depth interviews are essential when conducting phenomenology research to investigate the lived experiences of frontline healthcare personnel. However, because the physicians and nurses provide direct services at the hospital, the researcher experienced some obstacles in arranging such interviews.

i. Making an appointment before conducting the interviews was a key barrier in the data collection process. Healthcare professionals have a very hectic schedule and very little spare time at the hospital.

ii. Taking adequate time to interview the participants was a challenge in this study. They were in a hurry to visit several units and wards.

iii. Face masks were required to be worn during the interviews. Because the researcher and the subjects were wearing face masks, there were some communication issues. Furthermore, several participants used face shields as well as face masks, which exacerbated the situation.

Overcoming the Challenges

Although collecting data from frontline healthcare personnel amid the COVID-19 outbreak was difficult, the researcher has overcome obstacles in a variety of ways. The participants were initially told about the study and its significance for future implications. In regards to how much data was collected, the researcher regularly contacted participants for appointments so that they could share their experiences with the researcher in ample time. The researcher visited the hospital wards and offices as well as scheduled appointments over the phone. Thus, they overcame the abovementioned (i and ii) challenges.

Furthermore, the researcher explained to the participants that, because of the face mask and face shield, there would be less commotion, so the participants could ask questions if they could not receive answers from the researcher. Similarly, the participants were requested to respond loudly and repeat them if required. Hence, the abovementioned (iii) issue was addressed.

The Strengths of the Study and Future Research Directions

This is the first qualitative study that explores the lived experiences of the healthcare professions in the Sylhet region during the coronavirus outbreak. This investigation will serve as a benchmark for policymakers. Furthermore, the challenges encountered while conducting the study and the strategies used to overcome them can assist future researchers in conducting qualitative research in the midst of a health crisis.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 health hazard has had a devastating effect on Bangladesh, causing harm to people’s health and well-being. 6 People of all classes and professions are being seriously afflicted by the disaster’s waves. People who work in the medical health service have to deal with a lot of problems both at work and at home. As a result of the worldwide health catastrophe, they are experiencing feelings of loneliness, exhaustion, concern, and anxiety. Frontline healthcare workers, on the other hand, are valuable assets for any government aiming to reduce the disease burden. Their health and safety are essential not just for providing sufficient and safe care delivery, but also for disease prevention. 31 Moreover, there is a chance to learn from the experiences of pandemics and provide greater support for healthcare workers. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, they demonstrated a remarkable sense of responsibility and coordinated attempts to ease patients’ miseries. Furthermore, they played critical roles in the treatment of COVID-19 patients, and they attempted to offer the finest service to patients in a tough circumstance. 27

In Bangladesh, for example, physicians and nurses have encountered significant problems such as anxiety, workload, mental tautness, and inability to manage family responsibilities. It is suggested that policymakers take immediate action to ease the suffering of these service professionals. Substantial psychosocial and organizational assistance is required to help them cope with this unanticipated health crisis. Little attention has been paid to these problems in the context of Bangladesh, which urgently need to be investigated and suitable policies must be developed to alleviate their suffering through collaboration with the government and non-government bodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to all participants for their unconditional support in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: This is a thesis study of NM. NM conceived the design, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the article. MIH supervised the study, contributed to data collection and analysis, and assisted in its overall improvement. The final version of the paper for publication was reviewed and approved by all the authors.

Data Availability: A request can be made to the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: The paper is based on the data collected for the master’s thesis prepared by the first author. Accordingly, the study was approved by the University Research Centre of Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), Sylhet, Bangladesh. It adhered to all the ethical guidelines of the aforementioned institution. Furthermore, thesis students are required to provide presentations on every stage of the research, including proposal preparation, data collection tool development, data collection and data analysis, and the draft thesis. Expert members of the relevant examination committees, the thesis supervisor, and senior academics with qualitative research expertise provided thoughtful comments. After addressing all comments and following the ethical guidelines of the university, a thesis can be submitted for awarding the degree. Moreover, the researchers also scrupulously adhered to the Helsinki Declaration (1964) and its subsequent amendments.

ORCID iD: Nafiul Mehedi  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7475-257X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7475-257X

References

- 1. Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng S, Shi J, Lu L. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e37-e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang Y, Shang W, Rao X. Facing the COVID-19 outbreak: what should we know and what could we do? J Med Virol. 2020;92:536-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gholami M, Fawad I, Shadan S, et al. COVID-19 and healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:335-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. A cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):1388-1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xiong Y, Peng L. Focusing on health-care providers’ experiences in the COVID-19 crisis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e740-e741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hossain MI, Mehedi N, Ahmad I, Ali I, Azman A. Psychosocial stress and trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Soc Work Policy Rev. 2021;15(2):145-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mehedi N, Hossain MI. Patients with stigmatized illnesses during the COVID-19 health hazard: an underappreciated issue. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;67:102951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hossain MJ. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic among health care providers in Bangladesh: a systematic review. Banglad J Infect Dis. 2020;7:S8-S15. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(2):90-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, Wadhwa A, Varpio L. Choosing a qualitative research approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):669-670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colaizzi R. Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it: In: Valle RS, King M. (eds.) Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1978: 48–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morrow R, Rodriguez A, King N. Colaizzi’s descriptive phenomenological method. The psychologist. 2015;28(8):643-644. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lincoln YS, Lynham SA, Guba EG. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. (eds) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE; 2018;163-188. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33(2):e100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Ho SC, Chan VL. Risk factors for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in SARS survivors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(6):590-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hong X, Currier GW, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Zhou W, Wei J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in convalescent severe acute respiratory syndrome patients: a 4-year follow-up study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):546-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun L, Sun Z, Wu L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for acute posttraumatic stress disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:123-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eftekhar Ardebili M, Naserbakht M, Bernstein C, Alazmani-Noodeh F, Hakimi H, Ranjbar H. Healthcare providers experience of working during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(5):547-554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Swazo NK, Talukder MMH, Ahsan MK. A duty to treat? A right to refrain? Bangladeshi physicians in moral dilemma during COVID-19. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coto J, Restrepo A, Cejas I, Prentiss S. The impact of COVID-19 on allied health professions. PLoS One. 2020;15(10):e0241328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nyashanu M, Pfende F, Ekpenyong M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):655-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bennett P, Noble S, Johnston S, Jones D, Hunter R. COVID-19 confessions: a qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e043949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehta S, Machado F, Kwizera A, et al. COVID-19: a heavy toll on health-care workers. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(3):226-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lotta G, Coelho VSP, Brage E. How Covid-19 has affected frontline workers in Brazil: a comparative analysis of nurses and community health workers. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract. 2021;23(1):63-73. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vindrola-Padros C, Andrews L, Dowrick A, et al. Perceptions and experiences of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e040503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(6):e790-e798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morgantini LA, Naha U, Wang H, et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a rapid turnaround global survey. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0238217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A, et al. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1453-1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Razu SR, Yasmin T, Arif TB, et al. Challenges faced by healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative inquiry from Bangladesh. Public Health Front. 2021;9:647315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chang D, Xu H, Rebaza A, Sharma L, Dela Cruz CS. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(3):e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]