Abstract

The present study harnesses fluorescence quenching between a nonfluorescent aniline and fluorophore 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one [2AHBC] in binary solvent mixtures of acetonitrile and 1,4-dioxane at room temperature and explores the fluorophore as an antimicrobial material. Our findings throw light on the key performance of organic molecules in the medicinal and pharmaceutical fields, which are considered as the most leading drives in therapeutic applications. In view of that, fluorescence quenching data have been interpreted by various quenching models. This demonstrates that the sphere of action holds very well in the present work and also confirms the presence of static quenching reactions. Additionally, the fluorophore was first investigated for druglike activity with the help of in silico tools, and then it was investigated for antimicrobial activity through bioinformatics tools, which has shown promising insights.

1. Introduction

The fluorescence quenching mechanism has become an imperative spectroscopic tool to investigate biophysical and biochemical systems in different liquid media. It reveals important information about proteins, membranes, and macromolecular assemblies. For fluorescence quenching studies, we generally select quenchers such as carbon tetrachloride, aniline, bromobenzene, various metal ions, and quantum dots. The selection of quencher for the respective fluorophore mainly depends on the suitability of the molecular electronic structure of the quencher with the fluorophore.1,2 Recently, there has been an increased interest in photochemistry and photobiology among scientists and researchers because of the potential applications of fluorescence quenching in the field of molecular dynamics and molecular imaging. The fluorescence quenching study helps in understanding the dynamic changes of proteins in complex macromolecular systems to navigate microbial cell growth, etc.3−7 The main reason for fluorescence quenching is various molecular interactions such as energy relocation, molecular reorganization, collisional quenching, and ground-state complex formation.8 However, quenching mechanisms are also affected by the type of the quencher and the nature of the fluorophores.9 Fluorescence quenching can be employed to study protein folding at the single-molecule level,10 and further is constructive to acquire information about the conformational and/or dynamic changes of proteins in complex macromolecular systems.11

Coumarins have been the most important compounds for photophysical studies during the last few decades, as they are exceedingly fluorescent in nature. Coumarin is a plant-derived product that is naturally available in different plants such as cassia cinnamon, tonka beans, strawberries, apricots, black currents, etc.12 They are the most widely used organic substances in therapeutic applications as photochemotherapy, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and anti-HIV therapy agents, central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, and anticoagulants and dyes. A recent study on coumarin shows that coumarin-containing drugs can decrease estrogenic activity, which arises during menopause.13,14 Over the past few decades, technological improvements in both optics and electronics have greatly expanded fluorometric applications, predominantly in analytical fields, as a consequence of the high sensitivity and specificity afforded by the techniques. Using fluorometry in the study and conservation of cultural heritage is a recent development.15 The recent outburst in new fluorescence applications is accelerating the rapidity of research and development in basic and applied life sciences, including genomics, proteomics, bioengineering, medical diagnosis, and industrial microbiology. Fluorescence-based techniques are extensively used to address fundamental and applied questions in the biological and biomedical sciences. The current use of fluorescence-based technology includes assays for biomolecules, metabolic enzymes, DNA sequencing, research into biomolecule cell signaling dynamics and adaptation, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to identify specific DNA and/or RNA sequences in tissues. Recently, molecular methods have been applied to fuse the gene for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to other genes, leading to its expression in living cells. This allows a sophisticated breakdown of gene expression and cellular location of important structural proteins and enzymes. Extreme selectivity of fluorescent labels that can target specific organisms opens new avenues to resolve industrially and medically relevant problems in areas such as public health, the safety of foods, and environmental monitoring. Innovative fluorophores, new techniques including spectrally and temporally resolved fluorescence, and purpose-engineered instrumentation create niche commercial opportunities and lead toward tangible industrial outcomes. Fluorescence spectroscopy is one of the most sensitive and versatile instruments in medical, biological, and biochemical research. Table S1 lists some of its numerous applications.16

The fluorescence quenching of coumarins provides beneficial information about structural and dynamic properties. Studies have shown that effectively adding a substituent group to the parent molecule influences and enhances the biochemical and pharmacological properties.17−19 Coumarins have shown significant growth in the use of fluorescence in biological sciences, especially in biochemistry and biophysics, along with environmental monitoring, clinical chemistry, DNA sequencing, and genetic analysis by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Especially in molecular biology, fluorescence is used for cell identification and sorting in flow cytometry and in cellular imaging to reveal the localization and movement of intracellular substances by means of fluorescence microscopy. Because of the high sensitivity of fluorescence detection, there is continuing development of medical tests based on the phenomenon of fluorescence. These tests include widely used enzyme-linked immunoassays and fluorescence polarization immunoassays.

In the literature, only few articles are focused on fluorescence quenching of coumarin compounds in binary solvent mixtures, ADMET, molecular docking, in silico and antimicrobial studies. Hence, the above insights have enlightened us to undertake a detailed analysis on the title fluorophore. This present study would help us to find the possible applications of 2AHBC for molecular imaging and biomedical applications.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

The fluorescent probe 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one [2AHBC] was freshly synthesized as reported in the literature.20 Aniline is used as a quencher. Acetonitrile (ACN) and 1,4-dioxane (DXN) solvents are selected to prepare binary solvent mixtures. The solubility of the solute was checked prior to conducting the experiment. The solvents ACN, DXN, and quencher aniline were procured from S-D Fine Chemicals Ltd., India; they were of HPLC grade and used as received. To minimize self-quenching and reabsorption, the concentration of solute was kept minimum (1 × 10–6 M) in all of the solvent mixtures. Preparing a fresh solution prior to conducting the experiment would help in getting good results. The aniline concentration varied from low 0.00 M to high 0.01 M in all of the binary mixtures.

2.2. Absorption, Emission, and Lifetime Measurements

The study of spectroscopic properties was carried out in various concentrations of ACN + DXN mixture by measuring absorption spectra using a UV/vis spectrophotometer (model: U-3300) with a wavelength accuracy of 0.5 nm and emission spectra using a Hitachi spectrophotometer F-7000 at room temperature. For every measurement, the spectrometer was calibrated for the baseline. All of the glassware were cleaned well prior to preparing the solutions. Fluorescence lifetime measurements were carried out for the 2AHBC molecule with and without a quencher using a spectrometer (model: ChronosBH, TCSPC). All of the results obtained from the experiments can be reproducible within 5% of the experimental error.

2.3. Selection of Target

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a facultative pathogen, which has very high medical importance because of its resistant nature. P. aeruginosa is a multi-drug-resistant pathogen because of its ubiquitous nature. Intrinsic mechanisms that are responsible for the resistance have a great impact on the illness caused.21 A number of therapeutic targets to target P. aeruginosa have already been studied, but it is very important to select a target that is part of the antibiotic resistance mechanism. Targeting proteins involved in antibiotic resistance not only helps in reducing resistance but also helps in controlling the growth of pathogens.21 To find a suitable target, the complete genome of P. aeruginosa was downloaded with assembly idGCF_000006765.1 from NCBI Genome. The downloaded genome was submitted to the ARTS tool for the prediction of essential (core) genes and resistant gene models.22

2.4. ADMET, Drug-Likeness, and Molecular Docking

Adsorption, distribution, metabolism excretion, and toxicity analysis (ADMET) is one of the valuable processes present in the discovery pipeline of drugs. The main aim of ADMET studies is to find the physiochemical properties of the compound, which are a very important part of compound design and optimization. Oral absorption, receptor toxicity, clearance, and brain dispersion are significant features to be observed in ADMET studies.

Molecular docking is performed to calculate the binding affinity and the best possible mode of the ligand in a complex with protein.23,24 The structure of 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one was obtained from the PubChem database (Pubchem id: 748172),25 and the structure was optimized using Open Babel26 with minimization steps of 5000; the weighted rotor search method was employed to generate 50 conformations for the compound, and minimization was carried out using the steepest descent method.27 In the current study, Erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase was chosen as the target based on the ARTS prediction. The crystal structure of the protein was downloaded from the PDB database28 and a reference-based docking study was carried out using Autodock vinatool.29 The grid box was generated with the specification of 3.5 Ao areas around the bound cocrystallized ligand.30

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity of 2-Acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one

The In vitro antibacterial capability of the synthesized compound, 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one, was evaluated by the agar well diffusion technique according to the method published previously by Yaraguppi et al.30 The pathogens were obtained from the Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank (MTCC), Chandigarh, and the National Collection of Industrial Microorganisms (NCIM), Pune. The antibacterial effect was assessed against Gram-positive bacteria like Micrococcus luteus (NCIM 2871), Bacillus cereus (NCIM 2217), Bacillus subtilis (NCIM 2718), and Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 737). Also, it has been tested against Gram-negative pathogens such as Escherichia coli (MTCC 443), Salmonella typhimurium (MTCC 98), P. aeruginosa (MTCC 2297), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (MTCC 109). The pathogenic cultures (24 h broth) were spread-plated on the nutrient agar plates. Wells were created on the inoculated plates with a sterile cork borer for loading the compound. 2-Acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one (100 μl, 5 mg mL–1) prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was filled in the agar wells and allowed for diffusion. The compound-loaded plates were incubated for 24 h at 35 ± 2 °C. DMSO and gentamicin were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The zone of inhibition (mm) was recorded. The in vitro antifungal property was examined by employing the agar disk diffusion method following the method reported by Bagewadi et al.31 The compound was tested against a selected pathogen, Candida albicans, which is our lab isolate. The fungal pathogen was grown in potato dextrose broth (24 h) and inoculated on potato dextrose agar plates. The compound was loaded on Whatman filter paper no. 1 disks (6 mm) and kept on the agar plates. The inoculated cultures were incubated for 48 h at 30 ± 2 °C. The inhibition zone (mm) was measured. Positive control was clotrimazole.

2.6. Determination of the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

MIC is known as the maximum dilution of the compound that exhibits the inhibition of microbial growth. The MIC was executed as per the method illustrated by Bagewadi et al.32 using microdilution technique. The synthesized compound stock (5 mg mL–1) was diluted (using DMSO as diluent) to achieve a concentration between 5 and 0.625 mg mL–1. The bacterial pathogen P. aeruginosa was inoculated in nutrient broth and agitated with the respective concentrations of the compound for 24 h incubation (35 ± 2 °C). The turbidity was assessed by recording OD at 660 nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fluorescence Quenching of 2AHBC in Binary Solvent Mixtures

The molecular structure of 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one [2AHBC] is presented in Figure 1. Valuable information regarding quencher interactions with the fluorophore can be obtained by combining stationary and time-resolved measurements.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of the 2AHBC molecule.

Typical absorption and emission spectra of 2AHBC were recorded with and without aniline at room temperature and are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. A slight bathochromic shift was observed in the absorption spectra (Figure 2) due to the reactive nature of the solute toward the polarity of the solvent mixtures. Table 1 represents the excitation wavelength, emission wavelength, and peak intensity of the fluorophore at different quencher concentrations. A considerable bathochromic shift was observed in the fluorescence wavelength compared to the absorption wavelength as we go from a high polar solvent, i.e., 100% ACN, to a low polar solvent, i.e., 100% DXN. This is attributed to the dipole–dipole interaction between the solute and the solvent molecules in the excited state than in the ground state.

Figure 2.

Typical normalized absorption spectrum of 2AHBC + different concentrations of aniline in 60% ACN + 40% DXN solvent mixture.

Figure 3.

Typical fluorescence spectrum of 2AHBC + different concentrations of aniline in 60% ACN + 40% DXN solvent mixture.

Table 1. Fluorescence Intensity (I) of [2AHBC] as a Function of Quencher (Aniline) Concentration [Q] at a Fixed Solute Concentration (1 × 10–6 M) in Different ACN + DXN Solvent Mixtures at Room Temperature.

| 100% ACN + 0% DXN λexi = 379 nm, λemi = 456 nm |

80% CAN + 20% DXN λexi = 375 nm, λemi = 450 nm |

60% CAN + 40% DXN λexi = 375 nm, λemi = 447 nm |

40% CAN + 60% DXN λexi = 375 nm, λemi = 443 nm |

20% ACN + 80% DXN λexi = 375 nm, λemi = 440 nm |

0% CAN + 100% DXN λexi = 380 nm, λemi = 420.5 nm |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Q] | I | I0/I | I | I0/I | I | I0/I | I | I0/I | I | I0/I | I | I0/I |

| 0.00 | 4665.500 | 3747.270 | 3600.000 | 3560.000 | 3500.000 | 3028.000 | ||||||

| 0.02 | 3301.952 | 1.412 | 2867.341 | 1.306 | 2873.643 | 1.252 | 2768.762 | 1.285 | 2892.044 | 1.210 | 2564.158 | 1.180 |

| 0.04 | 2421.604 | 1.926 | 2184.928 | 1.715 | 2329.616 | 1.545 | 2160.823 | 1.647 | 2389.436 | 1.464 | 2144.113 | 1.412 |

| 0.06 | 1818.371 | 2.565 | 1669.565 | 2.244 | 1891.168 | 1.903 | 1674.593 | 2.125 | 1959.627 | 1.786 | 1760.470 | 1.719 |

| 0.08 | 1394.835 | 3.344 | 1229.971 | 3.046 | 1558.597 | 2.312 | 1278.738 | 2.783 | 1587.816 | 2.204 | 1410.314 | 2.147 |

| 0.10 | 1069.995 | 4.360 | 963.880 | 3.887 | 1232.003 | 2.922 | 929.138 | 3.831 | 1253.798 | 2.791 | 1084.714 | 2.791 |

However, as seen in Figure 3, a significant decrease was observed in the intensity of the peak maxima with an increase in the aniline concentration from 0.0 to 0.10 M. This signifies that aniline successfully quenches the fluorescence intensity of the solute molecule 2AHBC. However, the lifetime of 2AHBC was recorded by varying the quencher concentration in 100% DXN solvent. An increase in the quencher concentration was observed with a decrease in the lifetime of the solute under study.33,34Figure 4 shows the transient state lifetime decay profile of 2AHBC in 0% ACN + 100% DXN with and without a quencher at room temperature. The lifetime of 2AHBC was biexponential without the quencher and was found to be τ0 = 1.10 ns.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence decay curves of 2AHBC + with and without aniline in 0% ACN + 100% DXN.

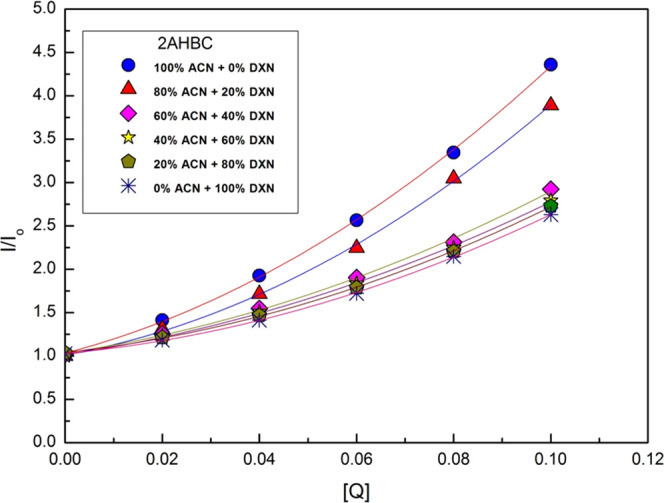

3.2. Stern–Volmer (S-V) Plots

The behavior of the solute molecule under the influence of binary solvent mixtures on the fluorescence quenching mechanism has been studied with the help of S-V relations. With the help of eqs 1 and 2, S-V plots were constructed in the steady state and in the transient state,35 respectively, and are shown in Figures 5 and 6.

| 1 |

| 2 |

where KSV = kqτ0 called the Stern–Volmer constant, kq is the bimolecular quenching rate constant, and τ0 represents the lifetime of the excited solute molecule in the absence of quencher [Q].

Figure 5.

Steady-state S-V plots for 2AHBC + different concentrations of aniline in various solvent mixtures.

Figure 6.

Transient state S-V plots for 2AHBC + different concentration of aniline in 0% ACN + 100% DXN.

In the present case, the S-V plot in the steady state shows the concave upward curve in all ACN + DXN solvent mixtures.36 The presence of static quenching may be the reason for the presence of static quenching. By comparing Figures 5 and 6, we can say that both types of quenching, static and dynamic quenching, are present. The pronounced difference in transient-state and steady-state measurements also shows that the static processes are strongly dominating in the quenching of 2AHBC fluorescence by the aniline used in this work. However, the S-V plot in the transient method shows linearity37 in ACN + DXN solvent mixtures. It signifies that the presence of static quenching is either due to the sphere of action model or the formation of the ground-state complex.38−40

According to the modified Stern–Volmer equation, S-V plots were constructed in the steady state and are shown in Figure 7

|

3 |

where W represents the partially

quenched particles, 1 – W represents the unquenched

particles, I0 is the intensity of the

solute without a quencher molecule, and I is the

intensity of the solute with a quencher molecule. The S-V quenching

constant (KSV) and a portion of the quenched

particles (W) can be easily determined from eq 3.41 However, the kinetic distance (r) and volume of

the static quenching constant (V) are evaluated by

the relation  .

.

Figure 7.

Modified S-V plot for 2AHBC in binary solvent mixtures.

3.3. Ground-State Complex Model

The nonlinear behavior of the S-V plot can be analyzed by incorporating eq 4

| 4 |

where kg represents the association constant.

This model can also be applied when there is any considerable change in the absorption or emission spectrum of the solute.42 As we have observed a slight bathochromic shift in absorption spectra and considerable bathochromic shift in emission spectra, we applied the ground-state complex model using spectral data. But, unfortunately, we have obtained all kg values as imaginary. Hence, we can suggest that the ground-state complex model does not hold well for the present molecule in all ACN + DXN solvent mixtures.18

3.4. Sphere of Action Model

The bimolecular parameters and quenching rate constants were determined by a modified S-V plot for 2AHBC. Table 2 presents the dielectric constant of solvent mixtures and quenching rate constants. The bottom of the table contains the radii of the solute (RS) and quencher (RQ). The obtained results were correlated with the literature.40−43 It is observed that the calculated values of encounter distance (R) are almost double the kinetic distance (r) in all of the binary solvent mixtures. This demonstrates that the present work obeys the sphere of action model44 and hence confirms the presence of static quenching reactions. However, static effects can also be evident from diffusion-limited reactions.45 Further, the concave upward curve from the linearity in the S-V plot signifies the simultaneous occurrence of static and dynamic quenching.46

Table 2. Various Fluorescence Quenching Parameters of [2AHBC] in ACN + DXN Solvent Mixtures.

| solvent mixture (% v/v) | εa | KSVb (M–1) | (kq × 10–9)c (M–1 s–1) | [(1 – w)/Q]dI | (W)e | (V)f (M–1) | (r)g (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% ACN + 0% DXN | 36.000 | 14.516 | 13.196 | 4.420 | 0.558–0.912 | 6.119 | 13.430 |

| 80% ACN + 20% DXN | 28.600 | 8.274 | 7.522 | 5.509 | 0.449–0.889 | 8.499 | 14.990 |

| 60% ACN + 40% DXN | 22.000 | 7.820 | 7.109 | 3.804 | 0.619–0.924 | 4.985 | 12.550 |

| 40% ACN + 60% DXN | 15.300 | 7.248 | 6.589 | 5.445 | 0.455–0.891 | 8.340 | 14.890 |

| 20% ACN + 80% DXN | 8.100 | 4.852 | 4.411 | 4.644 | 0.535–0.907 | 6.563 | 13.750 |

| 0% ACN + 100% DXN | 2.100 | 2.545 | 2.314 | 5.498 | 0.450–0.890 | 8.472 | 14.970 |

Dielectric constant of ACN + DXN solvent mixture.

S-V quenching constant.

Bimolecular quenching rate constant.

ntercept.

Unquenched complex.

Static quenching constant.

Kinetic distance.

3.5. Finite Sink Approximation Model

In the case of static quenching, diffusion-limited quenching reactions are confirmed by applying eq 5.47−49

| 5 |

where KSV0 = 4πN′ RDτ0ka/(4πN′ RD + ka). Using slopes and intercept of the linear plot of KSV against [Q]1/3, the value of KSV0 at [Q] = 0 and diffusion coefficient D were determined. KSV can also be written as

| 6 |

The distance parameter (R′) is evaluated using eq 7 as given below

| 7 |

Quenching reactions were diffusion-limited,49 provided ka > kd, i.e., for R′ < R, and kq > 4πN′R′ D for R′ > R.(32)

The linear plots of KSV–1as a function of [Q]1/3 for 2AHBC is shown in Figure 8. Table 3 presents the values of KSV, D, and distance parameter (R′) evaluated from eq 7. The obtained results were compared and found to be consistent with the literature.50,51 However, according to Zeng and Joshi45,46 et al., quenching reactions are said to be diffusion-limited only when R′ is larger than R(52,53) and kq> 4πN′R′D.54,55 From Table 3, it is confirmed that R′ > R and kq> 4πN′R′D56,57 in all of the ACN + DXN solvent mixtures. Hence, reactions are said to be diffusion-limited.

Figure 8.

Plots of KSV–1 as a function of [Q]1/3 for 2AHBC.

Table 3. Steady-State S-V Constant at [Q] = 0 and Other Quenching Constants for [2AHBC]a,b.

| binary solvent mixture (% v/v) | KSV0 (M–1) | Db = D × 105 (cm2 s–1) | R′ (Å) | 4πN′DR′ × 10–9 or kd (M–1 s–1) | ka × 10–9 (M–1 s–1) | kq × 10–9 (M–1 s–1) | 1/η (10–2 × P–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% ACN + 0% DXN | 13.119 | 1.918 | 8.220 | 11.926 | 23.345 | 2.904 | |

| 80% ACN + 20% DXN | 9.009 | 1.155 | 9.370 | 8.190 | 18.552 | 2.871 | |

| 60% ACN + 40% DXN | 8.436 | 1.376 | 7.330 | 7.639 | 13.297 | 2.439 | |

| 40% ACN + 60% DXN | 8.268 | 1.058 | 9.390 | 7.516 | 16.443 | 1.881 | |

| 20% ACN + 80% DXN | 6.536 | 0.931 | 8.430 | 5.942 | 11.570 | 1.295 | |

| 0% ACN + 100% DXN | 5.228 | 0.666 | 9.430 | 4.752 | 10.515 | 0.848 |

(2AHBC) R = RS (3.68 Å) + RQ (2.84 Å) = 6.52 Å. (RS, radii of the solute, RQ radii of the quencher).

τ0 = 1.10 ns, Db: diffusion coefficients determined from the finite sink model.

Using eqs 6 and 7, the distance parameter (R) and the mutual diffusion coefficient (D) were determined and are presented in Table 4. It was observed that there was no similarity between Da and Db and R′ and R in all of the ACN + DXN solvent mixtures. This is due to the deviations in the values of the adjustable parameter “a” in the Stokes–Einstein relation and the approximated values of the atomic volume in the Edward′s empirical relation.53 A similar discrepancy was observed in other studies.58−60 Hence, we can conclude that the finite sink approximation model helped us only to extract D and R′ values.

Table 4. Mutual Diffusion Coefficients and Distance Parameter R′ for [2AHBC]a,b.

| solvent mixture (% v/v) | Da = D × 105 (cm2 s–1) | Db = D × 105 (cm2 s–1) | R′ (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% ACN + 0% DXN | 6.304 | 1.918 | 8.220 |

| 80% ACN + 20% DXN | 6.155 | 1.155 | 9.370 |

| 60% ACN + 40% DXN | 5.229 | 1.376 | 7.330 |

| 40% ACN + 60% DXN | 4.032 | 1.058 | 9.390 |

| 20% ACN + 80% DXN | 2.776 | 0.931 | 8.430 |

| 0% ACN + 100% DXN | 1.564 | 0.666 | 9.430 |

Da: diffusion coefficients by the Stokes–Einstein relation. Db: diffusion coefficients by the finite sink model.

(2AHBC) R = 6.52 Å.

Furthermore, the effect of the dielectric constant of the solvent mixtures on the quenching constant of 2AHBC was studied. Figure 9 shows the nonlinear plot of KSV against the dielectric constant (ε) for 2AHBC. It was observed that with an increase in the dielectric constant of the solvent mixture, there was an increase in KSV, which shows the improved reaction rate and charge transfer nature. As we continue to increase the polar nature of the solvent, the dielectric constant increases, which in turn stabilizes the reacting species. The fluorescence quenching will be more pronounced for polar solvents with increasing dielectric constants, which might be due to the effect of the hydrogen bond on a radiationless deactivation process. This indicates an elevated charge transfer nature of the exciplex in the ACN + DXN solvent mixtures. Similar results were reported in other literature studies.58,59

Figure 9.

Plot of KSV against the dielectric constant (ε) for 2AHBC.

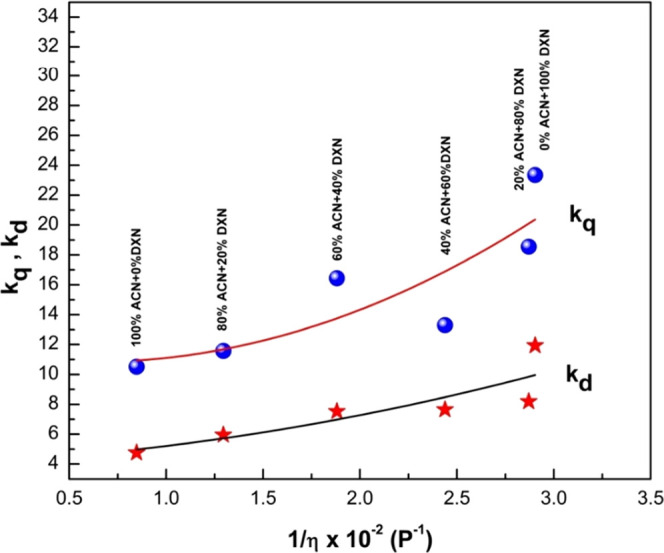

Figure 10 shows the graph of the frequency of encounter (kd) against the inverse viscosity of different binary mixtures. As seen in Figure 11, both the frequency of encounter, kd, and quenching rate parameter, kq, increase with a decrease in viscosity. Hence, we can conclude that quenching is controlled by material diffusion. As shown in Figure 11, the dependency of the bimolecular quenching rate parameter (KSV) was correlated with the viscosity of the binary solvent mixture. For the present molecule, an inverse dependency of viscosity of solvent mixture on KSV was observed.51 The fluorescence quenching has no major impact or a less pronounced impact on the viscosity of solvents. This is attributed to the mechanisms such as single–triplet conversion, charge transfer complex, and chemical reactions that might play a role.

Figure 10.

Plot of kq, kd against 1/η × 10–2 of the binary solvent mixture (ACN + DXN) for 2AHBC.

Figure 11.

Plot of KSV against viscosity of the binary solvent mixture (ACN + DXN) (η) for 2AHBC.

3.6. Antibiotic-Resistant Target in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

The analysis of the P. aeruginosa genome for the possible antibiotic-resistant targets was carried out using ARTS (Antibiotic-Resistant Target Seeker V2). The analyzed genome showed that the genome of P. aeruginosa consists of a total of 5681 genes, out of which 584 genes are core genes or the essential genes, 13 genes are part of biosynthetic pathway gene clusters, and 63 genes are antibiotic-resistant models. Erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase is one of the enzymes that are an essential protein in the lifecycle of P. aeruginosa and is also part of the antibiotic-resistant model. The three-dimensional (3D) crystallized structure of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase was obtained from the PDB (Protein Data Bank (PDB) id: 2O4C).61Figure 12 shows the 3D structure of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase with a resolution of 2.30 Å.

Figure 12.

3D structure of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase structure from P. aeruginosa (PDB id: 2O4C) colored based on the secondary structure (helix: red, sheet: yellow, loop: green).

3.6.1. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking was carried out on erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase with compound 2AHBC (Pubchem id: 748172) to find the best possible mode of binding. Details of ADMET properties of the compound 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one are presented in Table S2. ADMET analysis of the compound 2AHBC was carried out, and it was seen that the compound passed Lipinski’s rule of drug-likeness. It was also predicted that the compound has high GI absorption and is also BBB permeate. The best fit was selected based on the binding affinity score and based on the interactions with the important residues of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase. The target protein structure was further cleaned by removing the waters using Autodock tools, and the cocrystallized ligand of NAD+ was further removed for the molecular docking. The binding space of the cocrystallized was analyzed, and the key residues were identified. A total of 103 water molecules were removed from the structure.62

The grid box for the docking was considered based on the coordinates of the cocrystallized ligand. The coordinates were x = 27.37, y = 85.45, and z = 2.32, and the size of the grid box for the docking was 25 points for x, y, and z coordinates. The docking of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase with the optimized structure of 2AHBC was carried out with exhaustiveness of 100 (high accuracy), and the binding affinity was determined to be −7.9 kcal mol–1. A comprehensive analysis of the complex was done, and the involvement of key amino acid residues in the active site is tabulated in Table 5 and Figure 13.

Table 5. Docking Result of Erythronate-4-phosphate Dehydrogenase with 2-Acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one with Interaction Sites.

| compound name | docking score (Kcal mol–1) | interaction residues (hydrogen bond) | interaction residues (hydrophobic interactions) | pi-cation interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one | –7.9 | ASN91 | ARG44, ILE67, ASN91, TYR258 | ARG346 |

Figure 13.

3D image of the protein–ligand complex of erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase with 2AHBC with interacting sites.

3.7. Antimicrobial Evaluation of 2-Acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one

In vitro antimicrobial attributes of 2AHBC are presented in Table 6. Based on the antibacterial evaluation by the agar well diffusion method, the 2AHBC compound showed a diverse inhibitory effect on different pathogens. The compound was revealed to exhibit antibacterial attributes against all of the evaluated microbial strains. A zone of inhibition greater than 10 mm was termed a prominent effect. A pronounced effect was observed against P. Aeruginosa (23.3 ± 0.9 mm) (Gram-negative bacteria) and B. subtilis (19.5 ± 0.8 mm) (Gram-positive bacteria). In vitro antifungal activity of 2AHBC against C. albicans was also promising, with a 16.7 ± 1.3 mm zone of inhibition based on the analysis of the agar disk diffusion method. No effect with DMSO (negative control) and inhibitory effect with standard gentamicin (positive control) were observed. Evaluation of the MIC of the compound against P. aeruginosa was carried out considering the highest inhibitory effect shown on the pathogen. P. aeruginosa was found to be susceptible, exhibiting significant inhibition with a MIC of 2.5 mg mL–1 (Figure 14). Bacterial infections have led to significant health disasters globally possibly due to drug resistance. As a result, this has led to the development of new prospective drug molecules with both a specific and broad range of antimicrobial effects. The Gram-negative microbial strains are usually resistant to drugs due to the effective outer membrane that is constructed of lipopolysaccharide, which restricts the penetration of the drug molecules. It also recognizes and pumps out the chemical molecules out of the cell without allowing them to interact with the drug target. Hence, designing and synthesizing a drug molecule specific for Gram-negative microbial strain is crucial. Coumarins are desirable molecules for the development of novel antibacterial agents.63 Several synthesized coumarins are reported in the literature for various biological activities. El-Wahab et al.64 reported the synthesis of 2-(heteroaryl)-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-ones with antibacterial potential against E. coli and S. aureus. An application of antimicrobial polyurethane coating using 2-(2-amino-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one (a coumarin thiazole derivative) possessing antimicrobial potential has been reported by El-Wahab et al.64 Raj et al.65 synthesized several compounds and studied the antimicrobial effect and MIC against several bacterial and fungal pathogens, but none of the compounds could inhibit the growth of P. aeruginosa, and interestingly, we report the inhibition of P. aeruginosa by our synthesized compound. Studies showed that the electron-withdrawing groups usually exhibit the antifungal activity of the compounds against C. albicans and Candida tropicalis. The electron-releasing group may possibly promote the antibacterial effect against Gram-positive pathogens, and electron-withdrawing groups may trigger antibacterial effects against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative microbial strains65 as reported for newly synthesized 2H-benzo[h] chromene derivatives as a group of antibacterial adjuvants that exhibit effective biological properties. However, not much literature is available on the antimicrobial properties of the compound 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one. Each data value represents the mean±SD value of triplicate experiments and is significant at p < 0.05.

Table 6. Antimicrobial Properties of 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one.

| pathogens | zone of inhibition (mm ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| gram negative bacterial cultures | Klebsiellapneumoniae (MTCC 109) | 07.2 ± 0.5 |

| Salmonella typhimurium (MTCC 98) | 11.4 ± 0.6 | |

| aepPseudomonas aeruginosa (MTCC 2297) | 23.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Escherichia coli (MTCC 443) | 16.8 ± 0.8 | |

| gram positive bacterial cultures | Micrococcus luteus (NCIM 2871) | 15.2 ± 1.1 |

| Bacillus cereus (NCIM 2217) | 17.4 ± 0.7 | |

| Bacillus subtilis (NCIM 2718) | 19.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (MTCC 737) | 12.2 ± 1.2 | |

| fungal culture | Candida albicans | 16.7 ± 1.3 |

Figure 14.

Minimum inhibitory concentration of 2AHBC against P. aeruginosa.

4. Conclusions

Fluorescence quenching of 2AHBC in solvent mixtures of ACN + DXN was analyzed. The Stern–Volmer plot showed a concave upward curvature in the presence of quenchers. The studied system obeys the sphere of action static quenching model and confirms the presence of static quenching. For 2AHBC, kq was found to be greater than 4πN′R′D. Hence, quenching reactions were found to be diffusion-limited. There was a nonlinear dependency on the dielectric constant of the binary solvent mixture, and KSV suggests high charge transfer of the exciplex in the binary solvent mixture and an inverse dependency of viscosity of solvent mixture on KSV. The fluorescence quenching is more efficient in polar solvents, and in them, quenching decreases as the viscosity of the medium increases. This is attributed to the mechanisms such as single–triplet conversion, charge transfer complex, and chemical reactions that might play a role. We also expect fluorescence quenching to find its application in studying other biological processes, such as RNA folding or conformational changes of enzymes during functioning. In view of this, the fluorophore was first applied for druglike activity, and then it was checked for antimicrobial activity through bioinformatics tools, which showed positive results. Docking studies were performed for its antimicrobial activity against a facultative pathogen P. aeruginosa, as it is multi-drug-resistant. We have selected erythronate-4-phosphate dehydrogenase, which is part of the antibiotic resistance mechanism. After positive in silico studies, in vitro studies were carried out with selected pathogens to prove their antimicrobial activity, and the results were encouraging, with a higher zone of clearance for P. aeruginosa compared to other pathogens in the study. These considerations can strongly indicate that fluorescence quenching mechanisms are useful and extensively appropriate to obtain enriched information about the structure and dynamics of biologically important macromolecular systems.

Acknowledgments

This research work is supported by KLE Technological University under “Capacity Building Projects” grants. The author V.V.K. thanks the Management, KLE Society Belgaum, for financial support. The author R.M. acknowledges the Principal, MSRIT and the Management, Gokul Education Society, for encouragement.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02424.

Details of numerous applications of fluorescence spectroscopy (Table S1) and details of ADMET properties of the compound 2-acetyl-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one (Table S2) (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors equally contributed to the experimental work, evaluation of results, and manuscript preparation. V.V.K.: conceptualization, analysis of the fluorescence results, and drafting of the paper. R.M.: data analysis and supervision of the fluorescence experiment. R.K.: design and execution of the synthetic work. Z.K.B.: performed antimicrobial evaluation. D.A.Y.: performed ADMET Drug-Likeness and Molecular docking studies. S.H.D.: studied the P. aeruginosa genome for the possible antibiotic-resistant targets using ARTS. N.R.P.: supervision, validation, and finalizing the manuscript (review and editing).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lakowicz J. R.Principle of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Deepa H. R.; Thipperudrappa J.; Suresh Kumar H. M. A study on fluorescence quenching of LD-425 by aromatic amines in 1,4-dioxane–acetonitrile mixtures. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 1382–1388. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2012.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petdum A.; Waraeksiri N.; Hanmeng O.; Jarutikorn S.; et al. A new water-soluble Fe3+ fluorescence sensor with a large Stokes shift based on [5] helicene derivative: Its application in flow injection analysis and biological systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2020, 401, 112769 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K.; Han D.; Li X.; Peng M.; et al. A new Cu2+-selective fluorescent probe with six-membered spirocyclic hydrazide and its application in cell imaging. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 171, 107701 10.1016/j.dyepig.2019.107701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X.; Qu S.; Xioa L.; Li W.; He P. Thioacetalized coumarin-based fluorescent probe for mercury (II): ratiometric response, high selectivity and successful bioimaging application. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2018, 364, 503–509. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S.; Hazra S.; Chowdhury S.; Sarkar S.; Chattopadhyay K.; Pramanik A. A novel pyrrole fused coumarin based highly sensitive and selective fluorescence chemosensor for detection of Cu2+ ions and applications towards live cell imaging. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2018, 364, 635–644. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja D.; Melavanki R. M.; Patil N. R.; Kusanur R. A.; Thipperudrappa J.; Sanningannavar F. M. Quenching of the excitation energy of coumarin dyes by aniline. Can. J. Phys. 2013, 91, 976–980. 10.1139/cjp-2013-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal V. V.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Patil N. R. Analysis of fluorescence quenching of coumarin derivative under steady state and transient state methods. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 393–400. 10.1007/s10895-020-02663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker S. D.; Nahar L. Progress in the Chemistry of Naturally Occurring Coumarins. Prog. Chem. Org. Nat. Prod. 2017, 106, 241–304. 10.1007/978-3-319-59542-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang X.; Ha T.; Kim H. D.; Centner T.; Labeit S.; Chu S. Fluorescence quenching: A tool for single-molecule protein-folding study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 14241–14244. 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mátyus László.; Szöllozsi János.; Jenei Attila. Steady-state fluorescence quenching applications for studying protein structure and dynamics. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 2006, 83, 223–236. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy A.; O’Kennedy R. Studies on coumarins and coumarin-related compounds to determine their therapeutic role in the treatment of cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004, 10, 3797–3811. 10.2174/1381612043382693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melavanki R. M.; Patil N. R.; Sanningannavar F. M.; Geetanjali H. S.; et al. Solvent Effect on the Fluorescence Properties of Two Biologically Active Thiophene Carboxamido Molecules. Mapana J. Sci. 2013, 12, 49–68. 10.12723/mjs.24.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal V. V.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Bhavya P.; Patil N. R. A role of solvent polarity on bimolecular quenching reactions of 3-acetyl-7-(diethylamino)-2H-chromen-2-one in binary solvent mixtures. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 260, 221–228. 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.02.094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romani A.; Clementi C.; Miliani C.; Favaro G. Fluorescence Spectroscopy: A Powerful Technique for the Noninvasive Characterization, of Artwork. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 6837–6846. 10.1021/ar900291y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yguerabide J.; Yguerabide E. E. FLUORESCENCE SPECTROSCOPY IN BIOLOGICAL AND MEDICAL RESEARCH. Int. J. Rad. Appl. Instrum. Part C. Rad. Phys. Chem. 1988, 32, 457–464. 10.1016/1359-0197(88)90049-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H. M. S.; Kunabenchi R. S.; Biradar J. S.; Math N. N.; Kadadevarmath J. S.; Inamdar S. R. Analysis of fluorescence quenching of new indole derivative by aniline using Stern–Volmer plots. J. Lumin. 2006, 116, 35–42. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2005.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal V. V.; Patil P. G.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Afi U. O.; Patil N. R. Exploring the influence of silver nanoparticles on the mechanism of fluorescence quenching of coumarin dye using FRET. J. Fluoresc. 2021, 31, 393–400. 10.1007/s10895-020-02663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadadevarmath J. S.; Malimath G. H.; Melavanki R. M.; Patil N. R. Static and dynamic model fluorescence quenching of laser dye by carbon tetrachloride in binary mixtures. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2014, 117, 630–634. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusanur R. A.; Kulkarni M. V. A Novel Route for the Synthesis of Recemic 4-(Coumaryl) Alanines and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 1077–1080. 10.14233/ajchem.2014.15865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashina H.; Newman L.; Ashina S. Calcitonin gene-related peptide antagonism and cluster headache: An emerging new treatment. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 38, 2089–2093. 10.1007/s10072-017-3101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mungan M. D.; Alanjary M.; Blin K.; Weber T.; Medema M. H.; Ziemert N. ARTS 2.0: feature updates and expansion of the Antibiotic Resistant Target Seeker for comparative genome mining. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W546–W552. 10.1093/nar/gkaa374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaraguppi D. A.; Deshpande S. H.; Bagewadi Z. K.; Kumar S.; Muddapur U. M. Genome Analysis of Bacillus aryabhattai to Identify Biosynthetic Gene Clusters and In Silico Methods to Elucidate its Antimicrobial Nature. Int. J Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 1331–1342. 10.1007/s10989-021-10171-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sodanlo A.; Azizkhani M. Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Water-Soluble Peptides Extracted from Iranian Traditional Kefi. Int. J Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 1441–1449. 10.1007/s10989-021-10181-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.; Thiessen P. A.; Bolton E. E.; Chen J.; Fu G.; Gindulyte A.; Han L.; He J.; He S.; Shoemaker B. A.; Wang J.; Yu B.; Zhang J.; Bryant S. H. Pub Chem Substance and Compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, D1202–D1213. 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle N. M.; Banck M.; James C. A.; Morley C.; Vandermeersch T.; Hutchison G. R. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 2011, 3, 33–46. 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrivel U.; Deshpande S.; Hegde H. V.; Singh I.; Chattopadhyay D. Phytochemical moieties from Indian traditional medicine for targeting dual hotspots on SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: an integrative in-silico approach. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 672629 10.3389/fmed.2021.672629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S. K.; Bhikadiya C.; Bi C.; Bittrich S.; Chen L.; Crichlow G. V.; Christie C. H.; Dalenberg K.; Costanzo D. L.; Duarte J. M.; Dutta S.; Feng Z.; Ganesan S.; Ghosh D. S.; Goodsell S.; Green R. K.; Guranović V.; Guzenko D.; Hudson B. P.; Zhuravleva M.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: powerful new tools for exploring 3D structures of biological macromolecules for basic and applied research and education in fundamental biology, biomedicine, biotechnology, bioengineering and energy sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D437–D451. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O.; Olson A. J. AutoDock Vina. Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 31, 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaraguppi D. A.; Deshpande S. H.; Bagewadi Z. K.; Muddapur U. M.; Anand S.; Patil S. B. Identification of potent natural compounds in targeting Leishmania major CYP51 and GP63 proteins using a high-throughput computationally enhanced screening. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 6, 18–27. 10.1186/s43094-020-00038-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagewadi Z. K.; Dsouza V.; Mulla S. I.; Deshpande S. H.; Muddapur U. M.; Yaraguppi D. A.; Reddy V. D.; Bhavikatti J. S.; More S. S. Structural and functional characterization of bacterial cellulose from Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. steigerwaltii strain ZKE7. Cellulose 2020, 27, 9181–9199. 10.1007/s10570-020-03412-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagewadi Z. K.; Muddapur U. M.; Madiwal S. S.; Mulla S. I.; Khan A. Biochemical and enzyme inhibitory attributes of methanolic leaf extract of Datura inoxia Mill. Environ. Sustainability 2019, 2, 75–87. 10.1007/s42398-019-00052-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N. R.; Melavanki R. M.; Kapatkar S. B.; Chandrasekhar K.; Patil H. D.; Umapathy S. Fluorescence quenching of biologically active carboxamide by aniline and carbon tetrachloride in different solvents using Stern–Volmer plots. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2011, 79, 1985–1991. 10.1016/j.saa.2011.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melavanki R. M.; Muddapur G. V.; Srinivasa H. T.; Honnanagoudar S. S.; Patil N. R. Solvation, rotational dynamics, photophysical properties study of aromatic asymmetric di-ketones: An experimental and theoretical approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116456 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muttannavar V. T.; Melavanki R. M.; Sharma K. S.; Vaijayanthimala S.; Shelar V. M.; Patil S. S.; Naik L. R. Effect of preferential solvation and bimolecular quenching reactions on 3OCE in acetonitrile and 1,4-dioxane binary mixtures by optical absorption and fluorescence studies. Luminescence 2019, 34, 924–932. 10.1002/bio.3692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thipperudrappa J.; Deepa H. R.; Raghavendra U. P.; Hanagodimath S. M.; Melavanki R. M. Effect of solvents, solvent mixture and silver nanoparticles on photophysical properties of a ketocyanine dye. Luminescence 2017, 32, 51–61. 10.1002/bio.3147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Kulakarni M. V.; Kadadevaramath J. S. Quenching mechanisms of 5BAMC by aniline in different solvents using Stern–Volmer plots. J. Lumin. 2009, 129, 1298–1303. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2009.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Kulakarni M. V.; Kadadevaramath J. S. Role of solvent polarity on the fluorescence quenching of newly synthesized 7, 8-benzo-4-azidomethyl coumarin by aniline in benzene–acetonitrile mixtures. J. Lumin. 2008, 128, 573–577. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2007.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal V. V.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Patil N. R. Bimolecular fluorescence quenching reactions of the biologically active coumarin composite 2-acetyl-3H-benzo [f] chromen-3-one in different solvents. Luminescence 2018, 33, 1019–1025. 10.1002/bio.3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppal V. V.; Hebsur R. K.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanure R. A.; Patil N. R. Solvent Polarity and Environment Sensitive Behavior of Coumarin Derivative. Macromol. Symp. 2020, 392, 1900200 10.1002/masy.201900200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer J. Nonequilibrium statistical thermodynamics and the effect of diffusion on chemical reaction rates. J. Phys. Chem. A 1982, 86, 5052–5067. 10.1021/j100223a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer J. Additions and Corrections - Nonlinear Fluorescence Quenching and the Origin of Positive Curvature in Stern-Volmer Plots. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 5319. 10.1021/ja00304a601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer J. Diffusion effects on rapid bimolecular chemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 1987, 87, 167–180. 10.1021/cr00077a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N. R.; Melavanki R. M. Effect of fluorescence quenching on 6BAAC in different solvents. Can. J. Phys. 2014, 92, 41–45. 10.1139/cjp-2013-0177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G. C.; Bhatnagar R.; Doraiswamy S.; Periasamy N. Diffusion-controlled reactions: transient effects in the fluorescence quenching of indole and N-acetyltryptophanamide in water. J. Phys. Chem. B 1990, 94, 2908–2914. 10.1021/j100370a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.; Durocher G. Analysis of fluorescence quenching in some antioxidants from non-linear Stern—Volmer plots. J. Lumin. 1995, 63, 75–84. 10.1016/0022-2313(94)00045-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behera P. K.; Mishra A. K. Static and dynamic model for 1-naphthol fluorescence quenching by carbon tetrachloride in dioxane-acetonitrile mixtures. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 1993, 71, 115–118. 10.1016/1010-6030(93)85061-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaswami S.; Seshadri T. R.; Venkateswarlu V. The remarkable fluorescence of certain coumarin derivatives. Proc. - Indian Acad. Sci., Sect. A 1941, 13, 316–321. 10.1007/BF03049009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moriya T. Excited-state Reactions of Coumarins in Aqueous Solutions. I. The Phototautomerization of 7-Hydroxycoumarin and Its Derivative. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1983, 56, 6–14. 10.1246/bcsj.56.6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N. R.; Melavanki R. M.; Kapatkar S. B.; Chandrasekhar K.; Ayachit N. H.; Umapathy S. Solvent effect on the fluorescence quenching of biologically active carboxamide by aniline and carbon tetrachloride in different solvents using S-V plots. J. Lumin. 2012, 132, 558–565. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon C. F.; Eads D. D. Diffusion-controlled electron transfer reactions: Subpicosecond fluorescence measurements of coumarin 1 quenched by aniline and N, N-dimethylaniline. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 5208–5223. 10.1063/1.470557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nirupama J. M.; Chougala L. S.; Khanapurmath N. I.; Ashish A.; Shastri L. A.; Kulkarni M. C.; Kadadevarmath J. S. Fluorescence Investigations on Interactions between 7, 8-benzo-4-azidomethyl Coumarin and Ortho- and Para-phenylenediamines in Binary Solvent Mixtures of THF and Water. J. Fluoresc. 2018, 28, 359–372. 10.1007/s10895-017-2198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward J. T. Molecular Volumes and Stokes Einstein equation. J. Chem. Educ. 1970, 47, 261–270. 10.1021/ed047p261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evale B. G.; Hanagodimath S. M. Static and dynamic quenching of biologically active coumarin derivative by aniline in benzene–acetonitrile mixtures. J. Lumin. 2010, 130, 1330–1337. 10.1016/j.jlumin.2010.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroea L.; Murariu M.; Melinte V. Fluorescence quenching study of new coumarin-derived fluorescent imidazole-based chemosensor. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 318, 114316 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha D.; Negi D. P. S. Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by colloidal Cu2S nanoparticles through static and dynamic modes under different solution pH. Chem. Phy. 2020, 530, 110644 10.1016/j.chemphys.2019.110644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus Y. Preferential solvation in mixed solvents. 14. Mixtures of 1,4-dioxane with organic solvents: Kirkwood–Buff integrals and volume-corrected preferential solvation parameters. J. Mol. Liq. 2006, 128, 115–126. 10.1016/j.molliq.2005.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K.; Melavanki R. M.; Muttannavar V.; Bhavya P.; et al. Fluorescence spectroscopic studies on preferential solvation and bimolecular quenching reactions of Quinolin-8-ol in binary solvent mixtures. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2020, 1473, 012045 10.1088/1742-6596/1473/1/012045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavya P.; Melavanki R. M.; Kusanur R. A.; Sharma K.; Muttannavar V. T.; Naik L. R. Effect of viscosity and dielectric constant variation on fractional fluorescence quenching analysis of coumarin dye in binary solvent mixtures. Luminescence 2018, 33, 933–940. 10.1002/bio.3492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antina L. A.; Kalyagin A. A.; Ksenofontov A. A.; Pavelyev R. S.; Lodochnikova O. A.; Islamov D. R.; Antina E. V.; Berezin M. B. Effect of polar protic solvents on the photophysical properties of bis(BODIPY) dyes. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116416–116427. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo C. R.; Sahoo J.; Mahapatra M.; Lenka D.; Sahu P. K.; Dehury B.; Padhy R. N.; Paidesetty S. K. Coumarin derivatives as promising antibacterial agent (s). Arabian J. Chem. 2021, 14, 102922 10.1016/j.arabjc.2020.102922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaraguppi D. A.; Bagewadi Z. K.; Deshpande S. H.; Chandramohan V. In Silico Study on the Inhibition of UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine 1-Carboxy Vinyl Transferase from Salmonella typhimurium by the Lipopeptide Produced from Bacillus aryabhattai. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2022, 28, 80 10.1007/s10989-022-10388-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomha S. M.; Abdel-Aziz H. M. An Efficient Synthesis of Functionalised 2-(heteroaryl)-3H-benzo[f] Chromen-3-ones and Antibacterial Evaluation. J. Chem. Res. 2013, 37, 298–303. 10.3184/174751913X13662197808100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Wahab H. A.; El-Fattah M. A.; El-Khalik N. A.; Nassar H. S.; Abdelall M. M. Synthesis and characterization of coumarin thiazole derivative 2-(2-amino-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)-3H-benzo[f]chromen-3-one with anti-microbial activity and its potential application in antimicrobial polyurethane coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2014, 77, 1506–1511. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2014.04.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raj T.; Bhatia R. K.; Sharma R. K.; Gupta V.; Sharma D. M.; Ishar P. S. Mechanism of unusual formation of 3-(5-phenyl-3H-[1,2,4]dithiazol-3-yl)chromen-4-ones and 4-oxo-4H-chromene-3-carbothioic acid N-phenylamides and their antimicrobial evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3209–3216. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.