Abstract

The current investigation sought to clarify mechanisms of treatment effects in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Self-compassion and mindful awareness were assessed first as dispositional influences and then as mediators of outcome in unique models. One hundred thirty individuals participating in the 8-week MBSR intervention were recruited (73.08% female, mean age = 46.97, SD = 14.07). Measures of psychosocial well-being (Brief Stress Inventory [BSI], Perceived Stress Scale-10 [PSS]), mindful awareness (Mindful Awareness and Attention Scale [MAAS]), and self-compassion (Self-Compassion Scale [SCS]) were collected at preintervention and postintervention. Regression was conducted to examine the influence of baseline MAAS and SCS on change in PSS and BSI scores. Serial multiple mediator models were conducted separately with pre/postintervention BSI and PSS values as criterion, and preintervention/postintervention MAAS and SCS values as mediators. Higher levels of baseline self-compassion were predictive of greater reductions in PSS scores (β = 0.16). Reductions in BSI scores were serially mediated by change in self-compassion both directly (MBSR → ΔSCS → ΔBSI β = 0.06) and indirectly through mindful awareness (MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔSCS → ΔBSI β = 0.09). Results provide support for the role of self-compassion as both a predictor of treatment effect and a process through which MBSR operates. Mechanisms underlying MBSR effects appear to be unique to the outcome of interest.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Since its development in 1979, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has been subject to numerous outcome investigations supporting its role in promoting well-being and symptom improvement for various difficulties such as stress, pain, depression, and anxiety (Anheyer et al., 2017; Bohlmeijer, Prenger, Taal, & Cuijpers, 2010; Chiesa & Serretti, 2009; Huang, He, Wang, & Zhou, 2016; Khoury, Sharma, Rush, & Fournier, 2015; Sharma & Rush, 2014). MBSR is a structured intervention that primarily aims to cultivate nonjudgmental attention to present moment experience (i.e., mindfulness; Kabat-Zinn, 1982) through training in a variety of meditative practices. In addition to symptom reduction, MBSR appears to confer benefit through development of protective factors such as psychological resilience, distress tolerance, acceptance, and self-compassion (Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010; Goldsmith et al., 2014; Hill, McKernan, Wang, & Coronado, 2017; Raes, 2011; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop, & Cordova, 2005). Despite growing evidence of MBSR’s efficacy, the processes underlying treatment response remain less clear. The purpose of this investigation was to clarify how self-compassion and mindful awareness influence treatment response to MBSR. We separately considered these constructs as dispositional influences and mediators of MBSR effect.

Systematic reviews emphasize the importance of identifying factors that influence and mediate MBSR outcomes (Khoury et al., 2015; Rosenkranz, Dunne, & Davidson, 2019). It is generally accepted that changes in mindfulness mediate treatment outcomes (Gu, Strauss, Bond, & Cavanagh, 2015). In this context, mindfulness is understood as the tendency to bring purposeful, present-oriented, and nonjudgmental attention to daily life (Baer, 2019). However, some studies have failed to identify this relationship (Keng, Smoski, Robins, Ekblad, & Brantley, 2012; Labelle, Campbell, & Carlson, 2010). This may be due to issues with design or statistical concerns such as multicollinearity. Some authors also suggest that although MBSR can beneficially influence many constructs, the mechanism through which this influence occurs may be unique to the construct in question (Allen et al., 2012; Baquedano et al., 2017).

An additional construct that may influence outcomes in MBSR is self-compassion, an orientation toward personal suffering in which difficulties are met with mindful awareness, the perspective of universal human experience, and an offering or intent to alleviate distress (Neff, 2003a, 2003b). Research exploring self-compassion associates greater levels of self-compassion with less anxiety and depression, fewer reports of feeling isolated by one’s problems, and greater emotional regulation (Costa & Pinto-Gouveia, 2013; Hill et al., 2017; Krieger, Altenstein, Baettig, Doerig, & Holtforth, 2013; Raes, 2011). Mindfulness and self-compassion may interact over the course of MBSR. For example, MBSR appears to facilitate the development of self-compassion, and initial evidence suggests that increases in mindfulness may mediate MBSR-related changes in self-compassion (Birnie et al., 2010). Subsequent investigations identified self-compassion as a mediator of MBSR outcomes such as worry and fear of emotion (Gu et al., 2015; Keng et al., 2012). Notably, many of the studies of MBSR mechanisms have not utilized statistical techniques best suited for assessing mediation in within-subjects designs (Judd, Kenny, & McClelland, 2001). Modern approaches (Montoya & Hayes, 2016) more accurately provide for the assumptions of within-subjects data and direct assessment of indirect effects, potentially increasing power to detect effects (Hayes, 2009). When this methodology was employed, serial mediation of MBSR effects on mood were documented, whereby treatment outcomes were mediated by initial increases in mindfulness and subsequent increases in self-compassion (Evans, Wyka, Blaha, & Allen, 2018). It is unclear whether these relationships influence other constructs related to well-being such as perceived stress or overall psychological distress.

A growing body of literature has also investigated dispositional factors that may influence individual response to MBSR; however, there remains a need for further research. Some treatment-level factors shown to enhance outcome include treatment duration and facilitator skill level (Khoury et al., 2015). Patient-level factors that influence outcomes include age, attachment style, trait mindfulness, and distress tolerance (Cordon, Brown, & Gibson, 2009; Gallegos, Lytle, Moynihan, & Talbot, 2015; Gawrysiak et al., 2016; Shapiro, Brown, Thoresen, & Plante, 2011). Some research suggests that MBSR outcomes are not influenced by age, sex, trait mindfulness, spirituality, or religiosity (Greeson et al., 2015). Many of these studies have faced significant limitations such as small sample size or inadequate control for potential regression to the mean in single group designs.

The present study sought to clarify the role of self-compassion and mindfulness as both dispositional influences on outcomes (i.e., predictors of treatment response at baseline) and as mediators of outcomes (i.e., processes through treatment response occurs). We aimed to determine whether the magnitude of symptom change following MBSR is related to baseline levels of self-compassion and mindful awareness and to further discern the function of these constructs in mediating outcomes. We hypothesized that baseline values of both self-compassion and mindful awareness would predict treatment effects such that participants with greater levels of baseline self-compassion and mindful awareness would experience greater reductions in perceived stress and psychological symptoms. We also predicted that reductions in distress would be significantly, serially mediated by increases in mindful awareness and self-compassion.

2 |. METHODS

The present study is a secondary analysis of a previously published investigation of the effects of MBSR on psychosocial well-being (Hill et al., 2017). The data presented here are from a prospective cohort design with preintervention and postintervention assessment of psychosocial characteristics. Individuals with a variety of medical conditions were recruited from a large academic medical center and the nearby community from 2013 to 2015. Participants were excluded from the study if they met any of the following criteria: (a) active substance dependence, (b) inability to sit, stand, or lie down for the 2.5-hour duration of each weekly intervention meeting, and (c) experiences of suicidal or homicidal ideation, psychosis, and or mania within the previous year.

During the initial session, written informed consent was obtained from participants. The following measures were completed and preintervention and postintervention: a demographic questionnaire, the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10), the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), and the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Data collection was supported by the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform (Harris et al., 2009). Qualified participants completed the 8-week MBSR intervention at a large academic medical center. Study procedures were conducted under Institutional Review Board approval at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

2.1 |. Measures

2.1.1 |. Brief Symptom Inventory

The BSI is a 53-item survey that assesses psychological symptoms and pains of living over the past week using a Likert scale ranking in which 0 = not at all and 5 = extremely (Derogatis, 1983). The BSI contains a Global Severity Index (GSI) and nine domains: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. An average score for each subscale and across all items (the GSI) is calculated. As such, the measure supports identification of specific symptoms of psychological distress. The measure has shown reliability and validity in diagnostic accuracy for a series of mental disorders. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each of the nine dimensions and varies from 0.75 (psychoticism) to 0.89 (depression). The GSI has a stability coefficient of 0.90. The BSI subscales demonstrated notable correlations with comparable subscales of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), for example, the MMPI Paranoia subscale (r = 0.51) correlated strongly with the BSI Paranoid dimension indicating convergent validity (Boulet & Boss, 1991). In this sample, BSI-GSI Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.97 and 0.96 for preintervention and postintervention, respectively.

2.1.2 |. Perceived Stress Scale

The PSS-10 is a 10-item survey that assesses global perceived stress within the past 30 days on a 5-point scale in which 0 = never and 4 = very often (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Four of the 10 items—those that are positively worded—are reverse scored. Example items include “how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them” and “how often have you been able to control irritations in your life.” A total score is obtained by adding the scores of each item. Total scores range from 0 to 40. The PSS emphasizes individual experience and reactivity to life circumstances. Cronbach’s alpha for the PSS is 0.85, and the measure has good validity; the PSS has statistically significant positive correlations with Life Events scores and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Cohen et al., 1983). PSS Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.92 for both preintervention and postintervention in the present sample.

2.1.3 |. Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

The MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003) is a 15-item self-report survey that captures the respondent’s attention and awareness practices in daily living. A 6-point Likert scale in which 1 = almost always to 6 = almost never is used. An average score across all items is computed, with higher scores denoting higher levels of mindfulness. Example statements from the MAAS include “It seems I am ‘running on automatic’ without much awareness of what I’m doing” and “I find myself preoccupied with the future or past.” Cronbach’s alpha was evaluated in initial samples to be 0.82 (n = 327) and 0.87 (n = 239). The MAAS is notably correlated with the Trait Meta Mood Scale, particularly on its subscale of Clarity (Brown & Ryan, 2003). The MAAS has also distinguished Zen meditators (experienced in mindfulness) from the general population (Brown & Ryan, 2003). MAAS Cronbach’s alpha values in this sample were 0.91 for both preintervention and postintervention.

2.1.4 |. Self-Compassion Scale

Neff’s (2003a, 2003b) SCS contains 26 items measuring six subscales of self-compassion, that is, self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and overidentification. A 5-point Likert scale in which 1 = almost never and 5 = almost always is used to rate responses. An average score across all items and within each subscale is calculated. Negative subscales (self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification) require reverse scoring. Higher scores on the items in the negative subscales suggest decreased self-compassion, feelings of isolation, and the tendency to overidentify with one’s feelings and emotions. Higher scores in the positive subscale items suggest greater levels of self-compassion, common humanity, and greater mindfulness skills. Higher total scores for the SCS indicate greater levels of self-compassion. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure is 0.92, and the scale has shown good validity; Neff (2003a, 2003b) calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the SCS and similar scales. The SCS Total Score is used in all subsequent analyses. Although authors have raised concerns regarding the factor structure of the SCS (Brenner, Heath, Vogel, & Credé, 2017; López et al., 2015), recent work suggests further support for the use of the total score in diverse healthy and clinical populations as explaining the vast majority of scale variance (Neff et al., 2019; Neff, Whittaker, & Karl, 2017). In the present sample, SCS Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.96 and 0.95 for preintervention and postintervention, respectively.

3 |. INTERVENTION PROCEDURES

MBSR is a structured, 8-week intervention that aims to nurture the individual’s natural capacities toward well-being and stress reduction through training in a variety of formal (e.g., sitting meditation, body scan, and walking meditation) and informal (e.g., mindful eating) meditative practices, and movement practices based in gentle yoga (Blacker, Meleo-Meyer, Kabat-Zinn, & Santorelli, 2009). Didactic and experiential elements that emphasize relevant concepts such as stress reactivity and patterns of communication are also included. Participants completed 8 weekly 2.5-hour group sessions. Home practice recommendations included roughly 45 min per day of mindfulness practice. Practice recommendations evolve through the course from an initial focus on audio-guided body scan meditation with subsequent introductions of mindful movement and seated practices. As the course progresses, participants are encouraged to practice without guidance and to set their own practice recommendations. Participants were also encouraged to attend an additional full-day retreat to deepen their mindfulness practice. All facilitators completed formal certification in delivering MBSR from the University of Massachusetts Center for Mindfulness. Facilitators included a licensed mental health social worker, certified yoga/mindfulness instructor, and registered nurse, all of whom had more than 5 years’ experience of personal mindfulness practice and teaching experience.

4 |. DATA ANALYSIS

Description statistics were calculated for relevant demographic factors, and criterion and predictor variables. As stated, our previous work (Hill et al., 2017) identified significant improvements in both psychological distress and perceived stress over the course of the MBSR intervention. Unique statistical models were used to address each of the two primary aims of the manuscript. To assess the dispositional influence of mindful awareness and self-compassion on outcome, hierarchical regression controlling for baseline criterion values was used. To assess the mediational influence of mindful awareness and self-compassion on outcome, within-subjects serial multiple mediation was used. All analyses were completed in IBM’s SPSS, Version 25.

4.1 |. Prediction of treatment effects by baseline assessment

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to determine the influence of preintervention self-compassion and mindful awareness on treatment outcomes as measured by change in PSS and BSI-GSI scores. Separate models were conducted with difference scores (pretreatment minus posttreatment) for each outcome as criterion. Regression analyses were performed in three steps and were the same for both criterion variables. First, relevant covariates were entered. To account for the potentially confounding influence of preintervention criterion values, respective preintervention values for each measure were entered (O’Connell et al., 2017). Likewise, age and gender have both been found to influence self-compassion (Homan, 2016; Yarnell et al., 2015), and both were additionally entered in the first step. Predictors of interest, baseline SCS and MAAS values, were entered in subsequent individual steps.

4.2 |. Mediation of treatment effects by serial changes in mediators

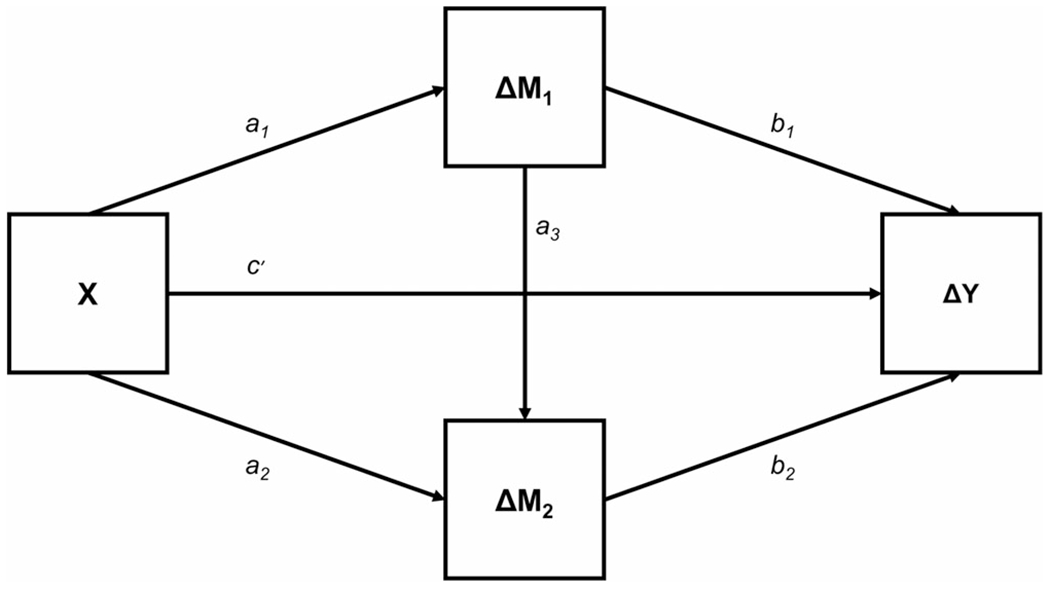

We then assessed serial multiple-mediator models (Montoya & Hayes, 2016, Figure 1) within the SPSS macro, Mediation and Moderation for Repeated Measures (MEMORE, Version 2.0). This model allows for the inclusion of pretreatment and posttreatment values of the mediator variables, so that we could also assess the indirect effects of MAAS and SCS change on criterion variables over time. Thus, we explored how concurrent changes in the mediating variables impacted outcomes. MEMORE extends the work by Judd et al. (2001) to allow for estimation of indirect effects and serial mediation in a path analytic framework. In serial mediation, each mediator is assumed to causally affect subsequent mediators (e.g., increases in mindful awareness are predicted to affect increases in self-compassion). Given that these are causal inferences, the estimated effects are unidirectional (MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔSCS → ΔBSI). For additional details regarding the assumptions of these models, please refer to Hayes, Preacher, and Myers (2011) and Judd et al. (2001). Statistical significance was determined at p ≤ 0.05, and confidence intervals for parameter estimates were determined from 5,000 bootstrapped samples. Unstandardized coefficients are reported. To clarify mediation effect sizes, partially standardized indirect effects (Preacher & Kelley, 2011) were calculated (, where ab is the mediation coefficient and σΔY is the standard deviation of the difference in the outcome variable from preintervention to postintervention).

FIGURE 1.

Shown is a conceptual diagram of a within-subjects, serial, multiple mediator model. This allows for assessment of the influence of multiple mediator variables (i.e., change in MAAS and SCS values, ΔM1 and ΔM2), potential serial influences, and the effect of a within-subjects factor (i.e., participation in MBSR, X) on an outcome of interest (e.g., change in PSS or BSI values, ΔY). Respective paths are labelled

5 |. RESULTS

5.1 |. Participant characteristics

Of 196 individuals who consented to participate in the study, 130 completed all intervention sessions and data collection preintervention and postintervention. On average, patients were about 47 years old, M (SD) = 46.97 (14.07), and 73.08% identified as female (n = 95).

5.2 |. Prediction of treatment effects by baseline assessment

We aimed to discern the influence of baseline SCS and MAAS values on change in psychological symptoms and perceived stress after controlling for confounding factors. For the BSI, hierarchical regression revealed that SCS and MAAS preintervention values were not significantly predictive of treatment effect, ps > .1 (Table 1). For change in PSS scores (Table 2), however, the addition of the SCS values (β = 0.16, SE = 0.34) predicted a significant portion of variance (ΔR2 = 0.02, ΔF(1, 123) = 4.47, p = 0.04). The addition of the MAAS to the model did not significantly predict PSS scores.

TABLE 1.

Multiple regression coefficients predicting change in BSI values

| Parameter | B (SE) | β | R2 (ΔR2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline BSI-GSI | 0.48 (0.05) | 0.70† | 0.52† (−) |

| Age | 0.00 (0.002) | −0.05 | |

| Gender | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.13* | |

|

| |||

| Baseline BSI-GSI | 0.50 (0.05) | 0.73† | 0.52† (0.02) |

| Age | 0.00 (0.002) | −0.06 | |

| Gender | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.12 | |

| Baseline SCS | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.06 | |

|

| |||

| Baseline BSI-GSI | 0.50 (0.06) | 0.73† | 0.52† (0.00) |

| Age | 0.00 (0.002) | −0.06 | |

| Gender | 0.11 (0.06) | 0.12 | |

| Baseline SCS | 0.03 (0.04) | 0.07 | |

| Baseline MAAS | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 | |

Abbreviations: BSI-GSI, Brief Symptom Inventory Global Severity Index; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; SE, Standard Error.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .001.

TABLE 2.

Multiple regression coefficients predicting change in PSS values

| Parameter | B (SE) | β | R2 (ΔR2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline PSS | 0.66 (0.07) | 0.66† | 0.43† (−) |

| Age | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.03 | |

| Gender | 0.16 (0.56) | 0.02 | |

|

| |||

| Baseline PSS | 0.70 (0.07) | 0.70† | 0.45† (0.02*) |

| Age | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.02 | |

| Gender | 0.00 (0.56) | 0.00 | |

| Baseline SCS | 0.71 (0.34) | 0.16* | |

|

| |||

| Baseline PSS | 0.70 (0.07) | 0.70† | 0.45† (0.00) |

| Age | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.02 | |

| Gender | 0.00 (0.57) | 0.00 | |

| Baseline SCS | 0.71 (0.37) | 0.16* | |

| Baseline MAAS | 0.00 (0.36) | 0.00 | |

Abbreviations: PSS, Perceived Stress Scale Total Score; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale; SE, standard error.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

5.3 |. Indirect effect of treatment by changes in mediators

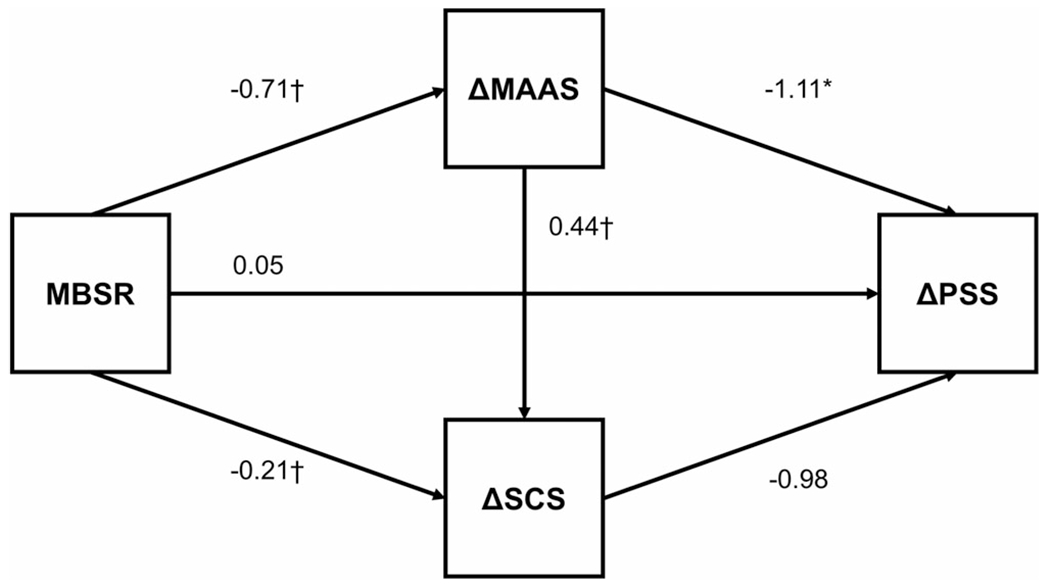

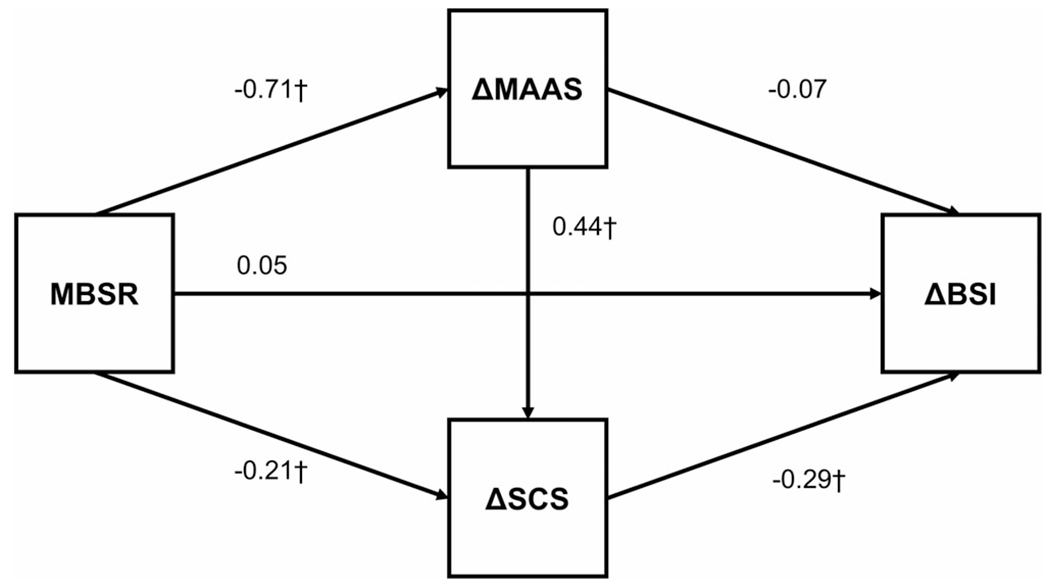

We sought to explore the indirect effects of change in MAAS and SCS on perceived stress and psychological symptoms. As reported previously (Hill et al., 2017), significant postintervention changes in all constructs were identified (Tables 3 and 4; refer to c and a paths). A serial multiple mediator model revealed changes in SCS and MAAS to have no significant indirect effects on pre-post PSS change (MAAS β = 0.78, bootstrap SE = 0.44, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.03, 1.69]; SCS β = 0.21, bootstrap SE = 0.18, bootstrap 95% CI [−0.10, 0.61]; MAAS → SCS β = 0.31, bootstrap SE = 0.26, bootstrap CI [−0.18, 0.85]), Table 3 and Figure 2. However, with BSI change as the target, change in SCS did have a significant indirect effect, ab β = 0.06 (bootstrap SE = 0.03) with 95% bootstrap CI [0.04, 0.15]. The path for the serial mediation effect of MAAS → SCS also displayed a significant indirect effect, β = 0.09 (bootstrap SE = 0.03) with 95% bootstrap CI [0.04, 0.15]. Change in MAAS scores did not produce a significant indirect effect (β = 0.05, bootstrap SE = 0.05, 95% bootstrap CI [−0.04, 0.14]). See Table 4 and Figure 3 for the full model.

TABLE 3.

Direct and indirect effects on Perceived Stress Scale Δ

| Direct effect (path) | β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBSR → ΔPSS (c) | 1.34 | 0.03 | 46.99 | 0.0001 | |

| MBSR → ΔPSS (c′) | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.92 | |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS(a1) | −0.71 | 0.06 | −10.27 | 0.0001 | |

| MBSR − ΔSCS(a2) | −0.21 | 0.06 | −3.78 | 0.0002 | |

| ΔMAAS → ΔSCS(a3) | 0.44 | 0.05 | 8.27 | 0.0001 | |

| ΔMAAS − ΔPSS(b1) | −1.11 | 0.52 | −2.13 | 0.03 | |

| ΔSCS → ΔPSS (b2) | −0.98 | 0.71 | −1.38 | 0.17 | |

| Indirect effect (path) | β | SE | abps | LLCI | ULCI |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔPSS (a1*b1) | 0.78 | 0.44 | 0.21 | −0.03 | 1.68 |

| MBSR → ΔSCS → ΔPSS (a2*b2) | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.61 |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔSCS → ΔPSS (a1*a3*b2) | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.08 | −0.18 | 0.85 |

Note: Full model: F(4, 125) = 4.65, p < 0.001, R2 = .13, MSE = 12.32.

Abbreviations: SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale.

TABLE 4.

Direct and indirect effects on Brief Symptom Inventory Δ

| Direct effect (path) | β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBSR → ΔBSI (c) | 0.25 | 0.00 | 80.25 | 0.0001 | |

| MBSR → ΔBSI (c′) | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.20 | 0.23 | |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS(a1) | −0.71 | 0.06 | −10.27 | 0.0001 | |

| MBSR → ΔSCS(a2) | −0.21 | 0.06 | −3.78 | 0.0002 | |

| ΔMAAS → ΔSCS(a3) | 0.44 | 0.05 | 8.27 | 0.0001 | |

| ΔMAAS → ΔBSI (b1) | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.34 | 0.18 | |

| ΔSCS → ΔBSI (b2) | −0.29 | 0.07 | −4.15 | 0.0001 | |

| Indirect effect | β | SE | abps | LLCI | ULCI |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔBSI (a1*b1) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.12 | −0.04 | 0.15 |

| MBSR → ΔSCS → ΔBSI (a2*b2) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔSCS → ΔBSI (a1*a3*b2) | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

Note: Full model: F(4, 125) = 13.55, p < 0.0001, R2 = .30, MSE = 0.12.

Abbreviations: SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale.

FIGURE 2.

Shown is a conceptual diagram with path coefficients of a serial multiple mediator model predicting change in PSS values following MBSR. Results did not support significant indirect effects for change in either proposed mediator variables (Table 3). Coefficients represent beta values for the displayed parameter. *p < 0.05; †p < 0.001. Abbreviations: PSS, Perceived Stress Scale Total Score; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

FIGURE 3.

Shown is a conceptual diagram with path coefficients of a serial multiple mediator model predicting change in BSI values following MBSR. Results identified significant indirect effects mediating outcome for self-compassion and the serial effect of change in MAAS values influencing subsequent changes in SCS values. Coefficients represent beta values for the displayed parameter. *p < 0.05; †p < 0.001. Abbreviations: BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale; MAAS, Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

6 |. DISCUSSION

The present study sought to assess the roles of mindful awareness and self-compassion in MBSR as both predictors of treatment response at baseline and as mediators of treatment effects on psychological distress and perceived stress. Results provide additional support for the role of self-compassion as a potentiator of treatment effect during MBSR. Specifically, higher levels of baseline self-compassion were associated with greater reductions in perceived stress over the course of treatment (β = 0.16). Mediation analyses suggested that reductions in psychological symptoms over the course of treatment occur through increases in self-compassion that are directly related to MBSR (MBSR → ΔSCS → ΔBSI β = 0.06) and those that occur indirectly through MBSR-related increases in mindful awareness (MBSR → ΔMAAS → ΔSCS → ΔBSI β = 0.09).

Although previous work assessed the role of baseline mindfulness in predicting MBSR outcomes, to our knowledge, no other investigations have studied self-compassion in this capacity. Our findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of self-compassion were more responsive to MBSR. Although self-compassion scores predicted a relatively small portion of variance in outcome (2.0%), each single point higher preintervention self-compassion was associated with a 0.70-point decrease in perceived stress at posttreatment. Degree of self-compassion may, among other constructs, aid in identifying individuals who benefit most from MBSR or those who may not be presently appropriate to complete the course. In contrast to previous findings (Gawrysiak et al., 2016; Shapiro et al., 2011), we did not find that preintervention mindfulness was predictive of change in either psychological distress or perceived stress. This finding is echoed in work that used a similar approach to control for regression to the mean (Greeson et al., 2015). Nonetheless, considering our single group design with limited follow-up, statistical controls accounting for regression to the mean (i.e., covarying for baseline assessment) may have led to conservative estimates of effect.

Our results also provide further support for the notion that mindfulness and self-compassion contribute to the beneficial effects of MBSR (Bergen-Cico & Cheon, 2014; Evans et al., 2018). Although multiple investigations have suggested self-compassion is directly involved in MBSR (Bergen-Cico & Cheon, 2014; Birnie et al., 2010; Keng et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2011), few have detailed the specific processes through which this may occur. Our results suggest that MBSR-related reductions in psychological symptoms are mediated by self-compassion and mindful awareness. Specifically, treatment-related increases in mindfulness appear to afford subsequent increases in self-compassion, which then affects symptom improvement. Notably, a post hoc analysis of the reverse serial mediation effect (MBSR → SCS → MAAS → ΔBSI) did not achieve statistical significance. This is consistent with the notion that mindful awareness of suffering is a necessary prerequisite to compassionate responding (Neff & Dahm, 2015). In order to respond compassionately, one must be able to “turn toward” suffering and observe it as it is, without judgement. Using the same analytic strategy, Evans et al. (2018) identified the same pattern of findings with mood state as outcome. Our findings seem to extend this work given that the BSI accounts for psychological symptoms in addition to mood states (e.g., somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, and obsession–compulsion).

Whereas some previous research has treated the PSS and BSI as representing a singular composite construct (Carmody, Baer, Lykins, & Olendzki, 2009), our results suggest that the factors both predicting and underlying changes in PSS and BSI scores following MBSR may be distinct. Although scores on these measures are often highly correlated, there may be important distinctions among them. Specifically, PSS appears to emphasize an individual’s experience of their life and affective reactivity to life circumstances, and the BSI appears to emphasize the identification and reporting of specific psychological symptoms. In fact, previous investigations of mediators of mindfulness-based interventions have identified distinct relationships among seemingly related constructs such as depression, anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction (Duarte & Pinto-Gouveia, 2017). Given the emphasis of discovering adaptive ways to work with stress and distress within the MBSR curriculum, our focus on these constructs allowed for both inquiry into core processes of the intervention itself and clarification of existing literature. Identification of these nuances among the BSI and PSS may guide future studies. Rosenkranz et al. (2019) recently noted that mindfulness training may operate uniquely for different constructs. Nonetheless, further research to clarify these relationships is needed.

Although the current investigation identified a number of meaningful relationships among constructs key to MBSR, the findings carry certain limitations. Although active control groups may impose certain challenges in identifying mindfulness-based intervention effects (e.g., similar outcomes can occur through different means), comparison with an appropriate control group could allow for the identification of mechanisms that are specific to MBSR with proper experimental designs (Rosenkranz et al., 2019). Likewise, mindfulness-related symptom improvements are often nonlinear and may continue for months following treatment (Rosenkranz et al., 2019). As such, the addition of follow-up assessments is recommended. There are also several constructs that were not assessed in the present study that may be relevant mediators or moderators of outcome (e.g., nonjudgment facets of mindfulness, attachment, and other personality characteristics). Future studies may benefit from the assessment of expanded models or those that account for potential moderated mediation in repeated measures designs (e.g., “Does baseline mindfulness moderate self-compassion’s mediating effect on symptom reduction?”). Certain demographic variables (e.g., racial and ethnic background and educational attainment) that could aid in characterizing our sample and support the generalizability of our results were not collected in the initial study. Inclusion of these features and examination of their influence on the relationships identified in this investigation is recommended. Finally, our sample was collected with a fee-for-service model, in which fees associated with MBSR participation were not billable to insurance. This may have limited participation to certain groups, potentially limiting generalizability of our results. Confirmation of these findings in diverse samples is necessary.

7 |. CONCLUSIONS

Self-compassion appears to be an influential factor in understanding MBSR’s effects on well-being, operating both as a predictor and mediator of outcome. Unique mechanisms may drive MBSR’s effects on distinct outcome constructs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The findings described were supported by CTSA award No. UL1 TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health. Study data and analysis scripts can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

Funding information

National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant/Award Number: UL1 TR002243

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Allen M, Dietz M, Blair KS, van Beek M, Rees G, Vestergaard-Poulsen P, … Roepstorff A. (2012). Cognitive-affective neural plasticity following active-controlled mindfulness intervention. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(44), 15601–15610. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2957-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anheyer D, Haller H, Barth J, Lauche R, Dobos G, & Cramer H (2017). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for treating low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 166(11), 799–807. 10.7326/M16-1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R (2019). ScienceDirect assessment of mindfulness by self-report. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 42–48. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquedano C, Vergara R, Lopez V, Fabar C, Cosmelli D, & Lutz A (2017). Compared to self-immersion, mindful attention reduces salivation and automatic food bias. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 13839. 10.1038/s41598-017-13662-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen-Cico D, & Cheon S (2014). The mediating effects of mindfulness and self-compassion on trait anxiety. Mindfulness, 5(5), 505–519. 10.1007/s12671-013-0205-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Birnie K, Speca M, & Carlson LE (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health, 26(5), 359–371. 10.1002/smi.1305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blacker M, Meleo-Meyer F, Kabat-Zinn J, & Santorelli S (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) curriculum guide© 2009. In Santorelli S & Kabat-Zinn J (Eds.), Mindfulness-based stress reduction professional education and training resource manual: Integrating mindfulness meditation into medicine and healthcare (pp. 1–22). Worcester, MA: Center for Mindfulness In Medicine, Health CAre, and Society. [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, & Cuijpers P (2010). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 68(6), 539–544. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet J, & Boss MW (1991). Reliability and validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 3(3), 433–437. 10.1037/1040-3590.3.3.433 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner RE, Heath PJ, Vogel DL, & Credé M (2017). Two is more valid than one: Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(6), 696–707. 10.1037/cou0000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, Baer RA, Lykins ELB, & Olendzki N (2009). An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(6), 613–626. 10.1002/jclp.20579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, & Serretti A (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(5), 593–600. 10.1089/acm.2008.0495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. Retrieved from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6668417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon SL, Brown KW, & Gibson PR (2009). The role of mindfulness-based stress reduction on perceived stress: Preliminary evidence for the moderating role of attachment style. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 258–269. 10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.258 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa J, & Pinto-Gouveia J (2013). Experiential avoidance and self-compassion in chronic pain. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(8), 1578–1591. 10.1111/jasp.12107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13(3), 595–605. 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte J, & Pinto-Gouveia J (2017). Mindfulness, self-compassion and psychological inflexibility mediate the effects of a mindfulness-based intervention in a sample of oncology nurses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(2), 125–133. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S, Wyka K, Blaha KT, & Allen ES (2018). Self-compassion mediates improvement in well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program in a community-based sample. Mindfulness, 9(4), 1280–1287. 10.1007/s12671-017-0872-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos AM, Lytle MC, Moynihan JA, & Talbot NL (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction to enhance psychological functioning and improve inflammatory biomarkers in trauma-exposed women: A pilot study. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(6), 525–532. 10.1037/tra0000053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawrysiak MJ, Leong SH, Grassetti SN, Wai M, Shorey RC, & Baime MJ (2016). Dimensions of distress tolerance and the moderating effects on mindfulness-based stress reduction. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 29(5), 552–560. 10.1080/10615806.2015.1085513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith RE, Gerhart JI, Chesney SA, Burns JW, Kleinman B, & Hood MM (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for post-traumatic stress symptoms: Building acceptance and decreasing shame. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19(4), 227–234. 10.1177/2156587214533703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeson JM, Smoski MJ, Suarez EC, Brantley JG, Ekblad AG, Lynch TR, & Wolever RQ (2015). Decreased symptoms of depression after mindfulness-based stress reduction: Potential moderating effects of religiosity, spirituality, trait mindfulness, sex, and age. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(3), 166–174. 10.1089/acm.2014.0285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, & Cavanagh K (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. 10.1080/03637750903310360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Preacher KJ, & Myers TA (2011). Mediation and the estimation of indirect effects in political communication research. Source-book for Political Communication Research: Methods, Measures, and Analytical Techniques, 23, 434–465. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RJ, McKernan LC, Wang L, & Coronado RA (2017). Changes in psychosocial well-being after mindfulness-based stress reduction: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Manual and Manipulative Therapy, 25(3), 128–136. 10.1080/10669817.2017.1323608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan KJ (2016). Self-compassion and psychological well-being in older adults. Journal of Adult Development, 23(2), 111–119. 10.1007/s10804-016-9227-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H. p., He M, Wang H. y., & Zhou M (2016). A meta-analysis of the benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) on psychological function among breast cancer (BC) survivors. Breast Cancer, 23 (4), 568–576. 10.1007/s12282-015-0604-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA, & McClelland GH (2001). Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-participant designs. Psychological Methods, 6, 115–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn J (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keng S-L, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ, Ekblad AG, & Brantley JG (2012). Mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based stress reduction: Self-compassion and mindfulness as mediators of intervention outcomes. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26(3), 270–280. 10.1891/0889-8391.26.3.270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury B, Sharma M, Rush SE, & Fournier C (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger T, Altenstein D, Baettig I, Doerig N, & Holtforth MG (2013). Self-compassion in depression: Associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and avoidance in depressed outpatients. Behavior Therapy, 44(3), 501–513. 10.1016/j.beth.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labelle LE, Campbell TS, & Carlson LE (2010). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in oncology: Evaluating mindfulness and rumination as mediators of change in depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 1(1), 28–40. 10.1007/s12671-010-0005-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López A, Sanderman R, Smink A, Zhang Y, Eric VS, Ranchor A, & Schroevers MJ (2015). A reconsideration of the Self-Compassion Scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PLoS One, 10 (7), e0132940. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya AK, & Hayes AF (2016). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 22, 6–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff K (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. 10.1080/15298860309032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. 10.1080/15298860309027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, & Dahm KA (2015). Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. In Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 121–140). New York, NY: Springer New York. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2263-5_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Tóth-Király I, Yarnell LM, Arimitsu K, Castilho P, Ghorbani N, … Mantzios M. (2019). Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in 20 diverse samples: Support for use of a total score and six subscale scores. Psychological Assessment, 31(1), 27–45. 10.1037/pas0000629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD, Whittaker TA, & Karl A (2017). Examining the factor structure of the Self-Compassion Scale in four distinct populations: Is the use of a total scale score justified? Journal of Personality Assessment, 99(6), 596–607. 10.1080/00223891.2016.1269334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell NS, Dai L, Jiang Y, Speiser JL, Ward R, Wei W, … Gebregziabher M. (2017). Methods for analysis of pre-post data in clinical research: A comparison of five common methods. Journal of Biometrics & Biostatistics, 8(01), 1–8. 10.4172/2155-6180.1000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Kelley K (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93–115. 10.1037/a0022658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes F (2011). The effect of self-compassion on the development of depression symptoms in a non-clinical sample. Mindfulness, 2(1), 33–36. 10.1007/s12671-011-0040-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz MA, Dunne JD, & Davidson RJ (2019). The next generation of mindfulness-based intervention research: What have we learned and where are we headed? Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 179–183. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, & Cordova M (2005). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(2), 164–176. 10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro SL, Brown KW, Thoresen C, & Plante TG (2011). The moderation of mindfulness-based stress reduction effects by trait mindfulness: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 267–277. 10.1002/jclp.20761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, & Rush SE (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction as a stress management intervention for healthy individuals: A systematic review. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 19(4), 271–286. 10.1177/2156587214543143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnell LM, Stafford RE, Neff KD, Reilly ED, Knox MC, & Mullarkey M (2015). Meta-analysis of gender differences in self-compassion. Self and Identity, 14(5), 499–520. 10.1080/15298868.2015.1029966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]