Abstract

While entrepreneurial orientation’s role in determining performance of businesses has been empirically established, studies from Africa or an industry-ecosystem perspective have been scarce. Furthermore, the significance of an entrepreneur’s vision is often acknowledged but little studied in relation to entrepreneurial outcomes. This study explored vision for growth as an individual entrepreneurial disposition and its relationship with innovation and performance outcomes among industry actors. The study collected self-reported quantitative data from a mixed sampling of value-system actors as representatives of the Kenyan leather industry. SPSS v.21 was used for descriptive statistics and SMART-PLS3 for exploratory and inferential analysis. Vision for growth was shown to determine both innovation and performance while innovation did not mediate the vision for growth and performance link as hypothesized. This study contributes to a further understanding of psychological perspectives of entrepreneurship, especially the vision for growth construct, and its significance to firms in an industry ecosystem. Recommendations are made for further research, training, policy, and practice interventions aimed at enhancing entrepreneurial vision and innovation from an industry-ecosystem perspective for realization of economic benefits in the wake of globalized competition.

Keywords: Vision for growth, Innovation, Performance, Entrepreneurial orientation, Value-system actors, Leather industry, Entrepreneurial ecosystem

Introduction

Background of the study

In Africa, the performance of manufacturing industries has been dismal despite the abundance of raw materials and availability of markets for finished products. In the leather industry, in particular, this performance potential is unrealized partly due to globalized competitive pressures (Dinh & Clarke, 2012; UNIDO, 2010; ITC, 2011; MOIT&C, 2016). Within the leather industry, vertical and horizontal linkages are weak with trading exchange lacking synergies; yet, theory suggests industry-actor networks are crucial for knowledge and perception of entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane, 2000; Hansen et al., 2015).

Entrepreneurship has been suggested as a solution to the successful competitive performance of manufacturing firms in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the region and Kenya, and this is especially the case the leather industry (Glaeser et al., 2009; Banga et al., 2015; Hansen et al., 2015; Mwinyihija, 2016). Entrepreneurial capabilities that lead to innovation can create or renew products, enterprises, and industries and can endow economies, especially of developing countries, with the competitiveness needed in the new world order (Audretsch, 2007; Audretsch et al., 2012). Furthermore, despite Kantabutra’s (2008) proposal of a theory to explain the impact of vision attributes on organizational performance, there has been little scholarly contribution to understanding the role of vision in entrepreneurship. Blanchard (2020) asserted that innovation as an entrepreneurial strategy of business owner/managers positively influenced the growth and sustainability of MSMEs (micro, small and medium enterprises). Blanchard (2020) highlighted the role of symbiotic interactions in a region’s businesses in fostering a supportive micro-environment for their growth and sustainability through innovation.

Despite recognition of the role of entrepreneurship in improving the competitiveness and performance of the manufacturing sector, this has not been adequately addressed, especially in Kenya’s leather industry. Mekonnen et al. (2014) called for holistic interventions that promote small and micro enterprises (SME) development in the leather sector in COMESA countries, among them Kenya, in order to address such observed challenges as lack of machinery, raw material availability, quality and cost, working capital, and market problems. The studies by Hansen et al. (2015) and Mwinyihija (2015) delineate Kenya’s leather industry’s value-system players while emphasizing the importance of collaborative interactions between multiple stakeholders for successful competition. Thus, it is important to have an ecosystem view of entrepreneurship in an industry in relation to its competitive performance. This study set out to close a research gap by exploring vision for growth as an individual entrepreneurial orientation or cognitive disposition among leaders of enterprises in Kenya’s leather industry from an ecosystem perspective.

This study therefore examined the relationship between vision for growth as an entrepreneurial orientation, and the outcomes of innovation and performance of value-system actors in Kenya’s leather industry. A heterogeneous group of actors in diverse roles of an industry ecosystem. However, due to the small sample size, analysis and conclusions could only be applied to the firm level rather than to value-system role or entire ecosystem levels.

Literature review

Vision for growth as an entrepreneurial orientation

There are few studies theoretical and empirical studies on role of vision in entrepreneurship, and even fewer in the African context or from an ecosystem perspective. Leadership and strategy scholars have articulated the determinant and positive impact of a leader’s vision in business (Kantabutra, 2008). This is seen in transformational leadership theory (Chai et al., 2017), and the enduring strategy perspectives on the role of goal formulation (Leiblein & Reuer, 2020a; George et al., 2019) and vision (Kantabutra, 2008). In addition, theories in psychology such as goal-setting (Locke & Latham, 2006; Baum et al., 2017) and self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985) emphasize the link between an leader or entrepreneur’s intentions (cognitions) and actions (behavior) that lead to venture success (performance) (Gagne, 2018). Early research by Locke showed significant direct and indirect effect of vision through communication, on enterprise performance (Locke & Latham, 2006).

Vision is an important aspect of Kuratko’s (2014) definition of entrepreneurship as a dynamic process of change and creation. A firm’s entrepreneurial capabilities are an extension of the individual entrepreneur’s inherent characteristics that include values and intentions (Altinay & Wang, 2011). In studying communication of strategic vision, Mayfield et al. (2014) refer to abundant scholarly work on significance of a well-articulated strategic vision or organizational purpose, as held and disseminated by the leader, in determining organizational performance outcomes. Entrepreneurial intentions predict strategic decisions and planned behavior to start or grow a business (Kruegeur, Reilly & Carsrud, 2000). Falbe and Larwood (1995) discuss the significance of vision for entrepreneurs. Ruvio et al. (2010) affirm the nature of a leader’s vision from literature, and its importance in achieving a desirable future in entrepreneurship. A study by Heikkilä et al. (2018) found that strategic goals (including profitability and growth) were relevant to SMEs and lead to business model innovation (BMI) paths. In one of few related African SME studies, Donkor et al. (2018) observed that despite importance of strategic goals in SME performance and competitiveness, there is little guidance on their role from practice or scholarship.

A well-constructed vision statement is seen as having a concise target (prime goal), and a future perspective of the organization and its environment. This provides, among other qualities, clarity and inspiring motivation that is associated with higher performance outcomes (Kantabutra & Avery, 2010). Kantabutra and Avery (2010) report the work of Robert Baum and colleagues (in Baum, Locke and Kirkpatrick, 1998) showing a direct relationship between vision characteristics and content with growth of entrepreneurial firms (as measured by sales, profits, employment, and net worth). Lans et al. (2011) discuss the significance of vision as a strategic competence needed of entrepreneurs. The Carlarnd Entrepreneurial Index (CEI), (Carland et al., 2002) which was applied by Amstrong and Hird (2009) and Asheghi-Oskooee (2015), had question items on importance of having written objectives and plans, thinking and planning, and interest in business growth as personality traits indicators. Balazs (2002) observed that leadership architectural role (including generating a vision setting goals, developing strategy) plays an important role in success of outstanding French restaurants that were built by entrepreneurial chefs.

In an emprical study of strategic planning and growth in Slovenian small firms, Skrt and Antoncic (2004) empirically demonstrated that entrepreneurs who developed and operationalized a growth vision as part of strategic management and the relationship with growth for their ventures was statistically significant compared to non-growth firms (Chi-squared=5.56, sig.=0.006 for “orientation to grow and increase profit,” and Chi-squared=6.20, sig.=0.044 for “all employees oriented towards the common goal”). Growth firms consistently had higher percentage for written vision statements and strategy drivers than non-growth firms (84.6% vs. 64.9% on written vision, 70.2% vs. 66.7% on entrepreneurial vision, and 74.5% vs. 58.3% on wish for planned growth and profits) in addition to having growth elements in their vision statements. They recommend studies on strategic planning across various dimensions and their relationship with growth of firms, in addition to application of strategic planning by entrepreneurs for growth benefits in small firms.

Kanyangale (2017) decried the lack of studies on strategic leadership of entrepreneurial firms/SMEs in Africa despite importance of the subject in survival and growth of businesses. One of few direct empirical studies on the role of vision in entrepreneurship was by Chi-hsiang (2015). The study investigated integration of shared vision on entrepreneurial management of new Chinese ventures using a sample of entrepreneurial managers and teams from 246 firms. Chi-hsiang (2015) asserts that entrepreneurial vision originates from the entrepreneur and links present and future states and it has a linear and causal relationship with performance. Chi-hsiang (2015) found that entrepreneurial vision correlates positively with factors mediating entrepreneurial performance, namely vision shared with an entrepreneurial team (β=0.88, t-value=10.14, p<0.001). Shared vision correlated positively with internal integration of vision (β=0.94, t-value=9.74, p<0.001) and external vision integration of vision (β=0.66, t-value=7.27, p<0.001) during establishment of new ventures. Internal vision integration had a significant mediating effect on the indirect effect of shared vision on performance of new enterprises (Sobel t-test of 4.33 met the statistically significant value of 1.96). Recommendations from the study were that entrepreneurs should have a shared vision with their team members as well as further research in diverse industries and appropriate performance measures. Donkor et al. (2018) used vision, mission statement, strategies and actions for objectives, and a prioritized implementation schedule as four measures of strategic goals. Their empirical study found that strategic goals significantly increased financial performance of select SMEs in Ghana. Furthermore, innovation capabilities of the SMEs enhanced the effect of strategic goals on financial performance.

Despite dearth of recent direct studies on vision in terms of an individual’s business growth orientation, there has been some research that shows the importance of vision as a cognitive trait of entrepreneurs and its relationship with venture performance. Recognition of an entrepreneur’s disposition to focus on goals in transforming them to action can be gleaned in scholarly literature. Reasoned intention to perform future behavior, or having a vision of goals, is seen as an antecedent of volition towards entrepreneurial action (setting and pursuing entrepreneurship intentions) Ilouga et al., 2016). A scholarly review by Zainol et al. (2018) concluded that a clear vision of the future as an element of entrepreneurial leadership was a significant determinant of performance measures in SMEs. The vision for growth construct used in this study was developed by the researcher from theoretical discussions of vision in entrepreneurship literature discussed above. This study adopted the definition of vision for growth as “future-oriented improvement goals.”

Innovation

According to Kuratko (2014), innovation is the process by which entrepreneurs convert ideas or opportunities into marketable solutions. Acs et al. (2015) contend that innovation is the path to business growth performance. Quoting Joseph Schumpeter, Acs et al. (2015), Audretsch et al. (2012), and other scholars assert that entrepreneurship as a way to economic development, and is expressed through innovation which in turn is the commercialization of creative ideas and inventions. Innovation is therefore seen as an intervening or mediating variable between entrepreneurial characteristics and entrepreneurial performance. Donkor et al. (2018) studied innovation capability as the ability to use of new ideas in responding to market with changes such as in introduction of new products, processes, and business models. They found that innovation capability Ghanaian SMEs studied was not only significant in improving financial performance, but also moderated the increasing effect of strategic goals on financial performance. Adam and Alarifi (2021) asserted that innovation practices of SMEs were implementation of new ideas in products, processes, marketing mechanisms, or administrative practices.

Keeley et al. (2013) presented ten types of innovation that ranged in focus from internal to external in terms of distance from customer experiences. Recent work on business model innovation (BMI) provides a balanced and systemic measurement model applicable to innovation theory and practice of the three main dimensions, namely value creation, value proposition, and value capture. Through rigorous methodological and empirical validation, Clauss (2016) developed BMI measurement scale comprising first- and second-order constructs measured using reflective and formative indicators respectively. Clauss (2016) recommended use of various levels of the measurement scale for diverse innovation process and outcome evaluation research. The BMI sub-construct as innovation indicator variables were similar to those adapted for this study as part of the measure of practical innovation outcomes and in congruence with induction from theory. BMI sub-construct indicators were adapted as measures for this study. Rajapathirana and Hui (2018) identified four types of innovation as product/service, process, organizational, and marketing innovation. Typologies of innovation posited by Keeley et al. (2013) and those developed by Clauss (2016) have been adapted into nine dimensions in this study for their relevance to industry ecosystems.

Scholarly work firmly asserts that innovation is not only antecedent to, but also a determinant of, firm performance (Bjerke, 2007; Hisrich et al., 2009; Keeley et al., 2013; Dinh & Clarke, 2012; McMullan & Kenworthy, 2015). While the role of innovation in positively influencing firm performance (especially profitability) has been questioned (Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese (2009), the same and other studies have asserted that innovation positively influences performance of both firms, industries and economies in the long term (Dinh & Clarke, 2012; Al-Ansari, 2014; Acs et al., 2015). Innovativeness of SMEs has been found to significantly and positively affect business performance during market turbulence (β=0.34, p<0.01) (Kraus et al., 2012; Kreiser et al., 2012). Using structural equation modeling, Rajapathirana and Hui (2018) empirical study established that innovation performance (product, process and market innovations) was antecedent to, and had a significant positive impact on market performance of insurance industry firms in Sri Lanka (path estimate at 0.230, p<0.01). Market performance consequently had a significant positive effect on firm financial performance (path estimate at 0.382, p<0.000).

Al-Ansari (2014) studied external and internal antecedents of innovation practices, and the relationship between innovation practices and business growth performance in 198 manufacturing and service-oriented Dubai market SMEs using a researcher-designed quantitative survey instrument. The study found that SMEs innovation practices had a significant positive influence on business growth performance (squared multiple correlations, R2 of innovation practices to innovation business growth performance and general business performance were 0.471 and 0.247 respectively (Al-Ansari, 2014). The study recommended adoption of innovation strategies by academics, venture management practice, and SME development policies.

Dinh and Clarke (2012) asserted that innovation is associated with improved performance in manufacturing firms. Dinh and Clarke (2012) found a positive correlation between firm innovation activities, especially introduction of new products and new customer delivery systems, and manufacturing firm growth performance. A study of Ghanaian, Kenyan and Tanzanian SMEs in manufacturing decried lack, while asserting the importance, of interactions between diverse institutions as actors in an innovation system, such manufacturing SMEs, technology institutions, and universities, in promoting innovation through knowledge links (Voeten, 2017). A study of the influence of innovativeness on growth of SMEs in Nairobi County showed that innovativeness, as a resource-based competence, had a significant linear relationship with firm growth as a performance measure. The study recommended that SME owners/managers apply process innovations to promote competitiveness and venture performance (profitability and growth) (Ngugi et al., 2013). Following prior theoretical and empirical studies, this research adopted innovation as an entrepreneurial outcome, a mediating determinant of firm performance, and consequently of industry performance.

Performance of value-system actors

A study by Dinh and Clarke (2012) concluded that entrepreneurship may influence performance of manufacturing firms in Africa. Cohen (2005) postulated industrial ecosystems and clusters as the foundational units of entrepreneurship and economic development. This ecosystem perspective of economic performance especially in new or entrepreneurial ventures is gaining increasing attention (Cohen, 2005; Acs et al., 2015), but the role of individual entrepreneur’s inclinations and abilities is not well accounted for.

Performance measures in literature are analyzed at firm level most studies advocate use of diverse measures that include both financial and non-financial indicators (even innovation), which may be archival, self-reported or secondary even with possible distinction between growth and profitability measures (Rauch et al., 2009). These include economic, social, and environmental outcomes (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001; Rauch et al., 2009; Santos & Brito, 2012; Stephan et al., 2015). Some like profitability, growth, and stakeholder satisfaction may be influenced negatively by risk-taking and innovation in the short-term (Puhakka, 2002; Rauch et al., 2009). A review of 1991–2018 papers in peer-reviewed journals by Mahmudova and Koviacs (2018) showed that performance of SMEs was a broad and flexible concept having diverse economic (such as sales margin, profit, return on equity, cash flow, liquidity, stock performance) and non-economic (customer and employee satisfaction, and quality of products) measures in research. According to the study, performance measurement in SME’s was seen as achievement of goals, it included growth indicators (such as profit and sales growth) and was used for improvement.

Kraus et al. (2012) used qualitative data on three financial measures of performance: gross margin, profitability, and cash flow and found they were influenced by entrepreneurial orientation traits individual CEO’s. Kraus et al. (2012) justified the use of perceived performance data reported by Dutch SME CEO’s as respondents in place of archival performance. As a recent study covering entrepreneurial vision in relation to performance, Chi-hsiang (2015) did not establish the direct correlation between his construct of entrepreneurial vision and entrepreneurial performance, instead emphasizing on correlations with mediating variables.

This study considers various economic and social measures of performance applied in various studies but as growth or improvement changes (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Santos & Brito, 2012; Dinh & Clarke, 2012; Al-Ansari, 2014). Broad performance measures were adopted from previous studies and applied in consideration of industry players and ecosystem goals. Profitability performance measure was applied in this study with caution: it may be negatively influenced by risk-taking and innovation activities especially at early stages of new venture development.

Research hypotheses

From the objectives of the study and a review of relevant literature, the following research hypotheses were formulated:

Ha1: Vision for growth as an entrepreneurial orientation of value-system actors determines performance of the leather industry in Kenya.

Ha2: Innovation by value-system actors mediates the relationship between vision for growth and performance of the leather industry in Kenya.

Methods

Research methodology

A cross-sectional survey was carried out that involved mixed design. Exploratory tests on vision for growth, innovation, and performance constructs as entrepreneurship variables was carried out followed by diagnostic tests to reveal the relationship between them (Kothari & Gaurav, 2014; Bless, Higson-Smith & Kagee, 2009). The study used reflective questions to collect data, from leaders of value-system actors as key informants and decision-makers, out of whom 73% identified themselves as owner-managers. Mixed sampling was carried out involving a census of 58 members of Leather Articles Entrepreneurs Association (LAEA) operating from Nairobi and its environs, and snowballing from 10 associated industry actors. Hansen et al. (2015) description of Kenya’s leather industry actors was used to identify the representative sample of study respondents and a membership list of LAEA members used as a sampling frame. Fifty-two valid responses were obtained from 68 respondents approached, giving a 76% response rate. Value-system actors in different roles such as processors, delivery agents, secondary delivery agents, industry network associations, regulators, and research agents were included (Hansen et al., 2015). Measurement items for vision for growth were adapted from scholarly literature on the significance and content of vision in entrepreneurship. Measures for the innovation variable were adapted from typologies by Clauss (2016) and Keeley et al. (2013). Financial and non-financial measures used by various scholars were adopted (Santos & Brito, 2012; Ming & Yang, 2009; Al-Ansari, 2014; Stephan et al., 2015).

Likert-type scale responses were coded from 1 for “Strongly Disagree” to 5 for “Strongly Agree.” An average of scores on indicator items was obtained from the Likert-scale responses as an index to show the degree of the measured variable (Neuman, 2009; Kothari et al., 2014). Thus, ordinal Likert responses to the indicator items were averaged to obtain a scale/rating measure for latent constructs. The performance variable was coded as 1–5 representing “large decrease” to “large increase” in the performance area considered before transformation into a composite index. Total positive responses were added, less the negative or neutral responses to give a five-point score on each item. Totaled scores were coded on a scale of 1–5 where 1 represented a large decrease (−5 to −3 responses), small decrease (−2 to −1 responses), no change (for zero score), small increase (for +1 to +2 responses), and large increase (+3 to +5 responses). Items worded negatively as proxies of desired positive performance (such as operating expenses representing business cost efficiencies, product defects measuring product quality, and customer complaints for stakeholder/customer satisfaction respectively) were coded in the reverse order. Empirical work by Ensley et al. (2000), Carland et al. (2002), and Amstrong and Hird (2009) involved development instruments, validation of constructs, and their application in measuring cognitive traits. The CEI study (Carland et al., 2002) had measurement items for collecting quantitative data and validated the construct using principal component factor analysis. Amstrong and Hird (2009) used self-reported measures on a polarized continuum for their cognitive style index (CSI) and applied the CEI. In their research, Lans et al. (2011) and Al-Ansari (2014) applied Likert-scale measures to collect self-reported data on entrepreneurship characteristics and performance of key informants and their businesses. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.21 was used for initial instrument reliability tests during a pilot study correlation and descriptive analysis of data from the main study. Further statistical analysis was performed using SMART PLS3 software. This involved factor analysis using partial least squares–structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and inferential analysis using Bootstrapping method. The algorithms and re-sampling were set for 5000 iterations. PLS path modeling is acknowledged for applicability in exploratory, confirmatory, and predictive research (Henseler, Hubona & Ray, 2016). PLS-SEM method is increasingly popular for applicability on small samples and without restrictive distribution of data (Hair et al., 2019).

Seventeen members of the Kariokor Market leather cluster (Hansen et al., 2015) participated in a pilot test but were approached to pilot the questionnaire and excluded from the main study. Reliability results showed that measurement items for study variables met the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient threshold of 0.7 (Garson and Statistical Associates Publishing (SAP), 2012). All indicator items in the measurement instrument were retained for the main study. Similar studies by Lans et al. (2011), Kraus et al. (2012) tested the relationship between entrepreneurial characteristics and business performance. Tacer et al. (2018) used a three-step research process of developing and validating a measurement construct for user-driven innovation (UDI). The research process involved the expert opinions for development and face validity (exploratory interviews with nine researchers and entrepreneurs), exploratory factor analysis (0.70 Cronbach’s alpha cut-off value) for reliability, and eventually a comprehensive construct validation study that applied the measurement tool on entrepreneurs to reveal dimensionality.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics for the study variables

Demographic distribution of respondents revealed 73% percent were male, 65% were aged 36 years and over, while 73% reported their role as owner-managers. This showed that the sample of Kenyan leather industry studied was dominated by an aging population of men as opposed to youth below 36 years and women. Thirty-nine percent of the ventures had been in existence between 5 and 10 years, and 42% for more than 10 years. Up to 55% had less than 10 workers, and 36% had 10–49 workers making the majority to be classified as SMEs. These statistics were consistent with reports showing that the informal sector provide the highest employment opportunity in Kenya at 84% (KNBS, 2019). Table 1 shows that the majority of businesses (65%) were in the processor role of the value chain. These were manufacturers of leather goods such as shoes.

Table 1.

Distribution of respondents across value-system roles

| Role | Frequency | Percent | Valid percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer | 5 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Processor | 33 | 63.5 | 63.5 | 73.1 |

| Delivery | 10 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 92.3 |

| Regulator | 1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 94.2 |

| Regulator | 2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 98.1 |

| Researcher | 1 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 100.0 |

| Total | 52 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Ratings for the four-indicator items used to measure this variable were average to obtain an overall vision for growth score. Sub-indicators for clarity of vision (VClarity) and vision for improvement (Vimprovement) were similarly measured and averaged before contributing to the overall score. The scale ratings ranged from 4.13 to 4.29 with an average of 4.22 (SD =0.747). This implied that the respondents believed that they exhibited high levels of vision for growth in their firms. Kantabutra and Avery (2010) emphasized that a vision statement having component of future orientation, clarity and challenge—in this case growth—was important in determining performance. Studying Nigerian women micro-entrepreneurs, Mohammed et al. (2017) found that strategic competency (including identifying, setting and acting on long-term goals) had a direct positive and significance effect on firm performance (β = 0.227, t = 3.411, p<0.01).

The innovation scale had nine indicator items measured that were averaged to obtain a score for innovation. Innovation scale ratings ranged from 3.81 to 4.42 with a mean of 4.10 (SD =0.505, n=52). This indicated that the respondents believed that they exhibited high levels of innovation, especially on the item “New Customers or Markets Introduced.” This was consistent with previous theoretical and empirical studies suggesting that innovation is important to SMEs and their performance.

Performance variable ratings ranged from 2.19 to 4.00 with an average of 3.47 (SD=0.647, n=52). This showed that respondents believed their firms exhibited above average levels of performance. This was especially the case with increasing productivity (75% reporting a small to large increase in productivity) and least with reducing product defects (68% reported small to large decrease in defects). Various studies have underscored the importance of innovation and performance and their relationship in business ventures in Africa and around the world (Kollmann & Stockmann, 2012; Dinh & Clarke, 2012; Sanchez, 2012)

Factor analysis on the study variables

Indicators for the study variables were subjected to exploratory factor analysis using PLS-SEM. Individual indicators with low reliabilities were deleted iteratively, with those having reliabilities of 0.6 and above retained (Hair et al., 2019). Table 2 shows reliability statistics for indicators used to measure the variables in the study. Three indicators were retained for the vision for growth construct from the initial four. Five and six indicators were retained for innovation and performance respectively from an initial nine each.

Table 2.

Reliability results for indicators of the study variables

| Factor analysis: outer loadings matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Performance | Vision for growth | |

| BusPerformComplaints | 0.594 | ||

| BusPerformDefects | 0.552 | ||

| BusPerformProductivity | 0.711 | ||

| BusPerformProfit | 0.784 | ||

| BusPerformQuantity | 0.831 | ||

| BusPerformShare | 0.820 | ||

| InnovCustEngagement | 0.598 | ||

| InnovMarkets | 0.720 | ||

| InnovOrgForm | 0.607 | ||

| InnovProcesses | 0.842 | ||

| InnovProducts | 0.834 | ||

| VActions | 0.872 | ||

| VGoals | 0.826 | ||

| VImprovement | 0.957 | ||

Further results of factor analysis showed composite reliabilities of the variables to have average variance extracted (AVE) values above the 0.5 threshold as shown in Table 3. Reliabilities of 0.6 and above are adequate for exploratory research. AVE shows the convergent validity of each construct’s measure. Collinearity statistics showed a variance inflation factor (VIF) of between 1 and 5, which was below the cut-off value of 5 (Hair et al., 2019). These statistics showed that the indicators were reliable measures of the different variables.

Table 3.

Results of composite reliability test for the study variables

| Construct reliability and validity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | rho_A | Composite reliability | Average variance extracted (AVE) | |

| Innovation | 0.801 | 0.909 | 0.846 | 0.530 |

| Performance | 0.812 | 0.822 | 0.865 | 0.523 |

| Vision for growth | 0.862 | 0.878 | 0.917 | 0.786 |

Correlation analysis on the study variables

As shown in Table 4, analysis revealed that the study variables showed a positive and significant correlation between vision for growth and performance (0.327, p<0.05). The correlation between vision for growth and innovation was low, positive, and statistically insignificant (0.065, p>0.05), while that between innovation and performance was negative and insignificant (−0.245, p>0.05). While correlation coefficients establish an association between any two variables, prediction of the dependent variable depends on the incremental role of multiple independent variables and this is established through regression analysis. Furthermore, unreliable correlation coefficients may be obtained if the sample size is small (Hair et al., 2019), especially in this case where the sample studied only 52. Continuation with analysis on the hypothesized causal relationships was opted for since finding a bivariate correlation should not be used to determine causation (Bewick et al., 2003). Available theoretical fundamentals also call for investigation on the possible relationship between the identified variables.

Table 4.

Correlations matrix for the study variables

| Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation | Performance | Vision for growth | |

| Innovation | - | ||

| Performance | −.245 | - | |

| Vision for growth | .065 | .327* | - |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed); N=52

Test for hypotheses

Inferential analysis involved complete bootstrapping for two-tailed tests at 0.05 significance levels to obtain decision statistics. The resampled mean R2 values and corresponding t-statistics showed the models for relationships between vision for growth and outcomes of innovation and performance were reliable for further analysis.

Coefficient of determination (R2) was used to measure the model’s explanatory power in the sample studied (Hair et al., 2019). Vision for growth determined 25% and above of both innovation (R2=0.258) and performance (R2=0.336) variables in the sample respectively. The t-statistics for the determination model were above 1.96 threshold and significant for both innovation (t=2.410, p=0.033) and performance (t=2.938, p=0.003) at p<0.05. This implied that the model could be used to infer significance of the relationship between vision for growth and the two outcome variables of innovation and performance.

The path coefficients for the relationships showed that vision for growth increased innovation by a factor of 0.469 and performance by a factor of 0.411. The resultant regression equations were as follows:

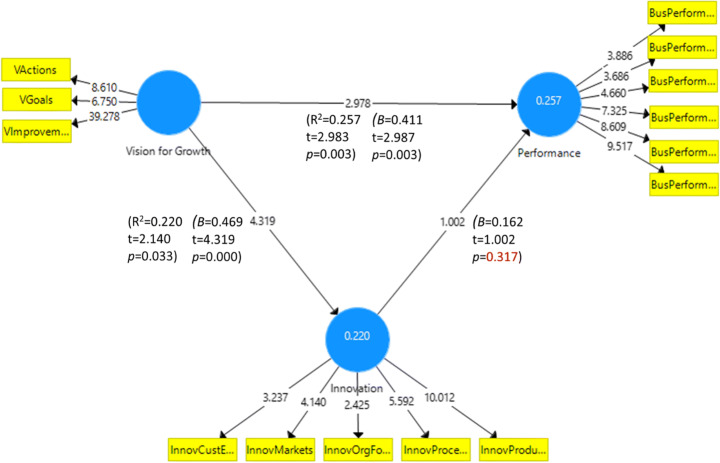

The coefficient for effect of innovation on performance was however not significant at p<0.05. This implied that innovation did not have a significant effect on performance of value-system actors in Kenya’s leather industry. The structural model for the relationship between the study variables is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structural model for the relationship between study variables

As shown in Table 5, the direct effects showed that the relationship of vision for growth as a determinant of both innovation and performance was significant at p<0.05. However, innovation was not a significant determinant of performance. The statistics confirm acceptance of H1 that vision for growth determines performance of value-system actors in Kenya’s leather industry. Confirmation of H1 is consistent with scholarly literature that an entrepreneurial vision is important in determining performance outcomes, in this case those of actors in an industry ecosystem.

Table 5.

Results of the direct relationships between vision for growth, innovation, and performance

| Total effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P values | |

| Innovation -> performance | 0.162 | 0.216 | 0.162 | 1.002 | 0.317 |

| Vision for growth -> innovation | 0.469 | 0.497 | 0.108 | 4.319 | 0.000 |

| Vision for growth -> performance | 0.487 | 0.520 | 0.098 | 4.956 | 0.000 |

The relationship between vision for growth and performance through innovation was not significant at p<0.05, and this is confirmed by the statistics for indirect effect as shown in Table 6. H2 was therefore rejected and the null hypothesis accepted that innovation does not mediate the relationship between vision for growth and performance of value-system actors in Kenya’s leather industry. The rejection of H2 is inconsistent with theoretical postulations on the role of innovation outcomes in mediating the causal relationship between vision for growth and performance in entrepreneurship. The importance of innovation in business has been empirically shown despite having either negative or positive effect on performance. Using PLS-SEM bootstrapping, Adam and Alarifi (2021) found that innovation practices had a significant positive influence on business performance (STD beta=0.45, t=8.432, p=0.00) and strongly linked to business survival (STD beta=0.054, t=3.782, p=0.00) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 6.

Results of the indirect relationships between vision for growth, innovation, and performance

| Total indirect effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original sample (O) | Sample mean (M) | Standard deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P values | |

| Innovation -> performance | |||||

| Vision for growth -> innovation | |||||

| Vision for growth -> performance | 0.076 | 0.105 | 0.078 | 0.977 | 0.329 |

The validity of vision for growth as factor in entrepreneurship is supported by theoretical and available empirical literature suggesting the significance of visionary intent or thinking of entrepreneurs (Altinay & Wang, 2011., 2011; Kruegeur et al., 2000; Kantabutra & Avery, 2010; Aragon-Correa et al., 2008). Though there are few studies using vision for growth as a variable in entrepreneurship, theoretical literature in fields of entrepreneurship and strategy indicate that having a clear, well-articulated vision is essential for venture performance. Chi-hsiang (2015) emphasized the importance of an entrepreneurial vision in guiding the starting of a venture into a desired strategic future and profoundly influencing its performance. A similar positive and significant relationship between vision and SMEs performance has been realized from literature review in Nigeria (Bakar & Zainol, 2015).

Previous studies suggest that innovation has different multi-dimensional measures similar to those used here. Studying established yet entrepreneurial firms, Amit and Zott (2012) identified factors such as creating novel activities to be performed (activity system content), new ways of activities’ linkage an sequence (activities structure), changing parties that perform activities (activities governance) with which parallels to capability innovation (with resultant costs revenues changes), change in organizational form and change in an organization’s interaction with the industry system respectively. Findings by Roach et al. (2016) indicated that innovativeness discriminated into two sub-constructs, namely innovation orientation and product/service innovation. These were consistent with previous studies on entrepreneurship that identify business performance as a dependent variable. Diverse performance measures were applied in this study as determined from previous theoretical and empirical studies (Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003, 2005; Rauch et al., 2009; Jain, 2011; Sanchez, 2012; Al-Ansari, 2014; Kraus et al., 2012; Ndubisi & Iftikhar, 2012; McMullan & Kenworthy, 2015).

Conclusions

This study established the validity of vision for growth as an entrepreneurial orientation, and both innovation and performance as entrepreneurial outcomes and factors of entrepreneurship. Vision for growth had three cognitive indicators namely having business goals, knowing actions to achieve business goals and having business improvement goals. The innovation variable five indicators while performance had six. As a factor, vision for growth determined both innovation and venture performance in Kenya’s leather industry. However, innovation did not mediate the relationship between vision for growth and performance. These results were supported by previous studies on the role of vision in guiding enterprise performance and growth but were not consistent with the hypothesized mediation of innovation in the relationship.

Given the critical interactions in an industry ecosystem such as the leather industry in Kenya, understanding and developing an entrepreneurial vision for growth capacity of entrepreneurs can lead to an improvement in both innovation activities and venture performance. Vision for growth is therefore important and should be cultivated among key individual players, such as enterprise owners and leaders, in order to develop a globally competitive entrepreneurial ecosystem. Therefore, results of this study contribute to development of entrepreneurship theory, the transfer of knowledge in academia, its application in business practice and the formulation of guiding policies for industry ecosystems. As a factor-based industry study from Africa, this research illuminates entrepreneurship from an ecosystem perspective and in a less-studied region.

Since the variables are yet to be studied as presented here, there is need for empirical evidence from similar inquiries in different industries for knowledge development. This study therefore recommends further explorative and diagnostic studies to validate the constructs identified as vision for growth, innovation, and performance, testing their relationships and relevance in diverse contexts. Both innovation and performance should be seen as outcomes, with the latter using change or growth indicators. While clarity of vision was not significant as an indicator of the vision for growth factor in the sample studied, strategy, and entrepreneurship literature as well as continued practice suggests that it is important in determining venture success. This study therefore recommends that clarity of vision, as an indicator of vision for growth, should be investigated further in terms of the qualities such as general outcomes, timeframe, products, context, and measurement. Despite literature on the significance of innovation in venture performance, results from this study did not support the hypothesized mediating role of innovation on the relationship between vision for growth and performance. This relationship therefore requires further investigation, including the dimensionality of innovation as an entrepreneurship outcome variable.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement is hereby given for information on Kenya’s leather industry from the following source:

Hansen, E. R.; Moon, Y. & Mogollon, M. P. (2015). Kenya - Leather Industry: Diagnosis, Strategy, and Action Plan. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/397331468001167011/Kenya-Leather-industry-diagnosis-strategy-and-action-plan

Abbreviations

- LAEA

Leather Articles Entrepreneurs Association

- MOIT&C

Ministry of Industrialization Trade and Cooperatives

- PLS

partial least squares

- SEM

structural equation modeling

- MSME

micro, small and medium enterprise

- SME

small and medium enterprise

- SPSS

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- SSA

Sub-Saharan Africa

- UNIDO

United Nations Industrial Development Organization

Author contribution

Simon Kamuri is the sole contributor and author of this paper.

Data availability

The data used for this study are available from the author upon reasonable request. The author retains copyright for the data and materials used in the study except where sources are acknowledged.

Code availability

Coding as used in context of data entry meant manually transforming response data to 5-point Likert scale values.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Acs, Z. J., Szerb, L. & Autio, E. (2015). Global Entrepreneurship Index 2015. Washington: The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute (GEDI). https://thegedi.org/global-entrepreneurship-and-development-index/

- Adam NA, Alarifi G. Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the COVID-19 times: The role of external support. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 2021;10(15):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13731-021-00156-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansari, Y. D. Y. (2014). Innovation practices as a path to business growth performance: A study of small and medium-sized firms in the emerging UAE market. (Doctoral Thesis) Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW. https://epubs.scu.edu.au/theses/355/

- Amit, R. & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring 2012, 53(3) 41-49. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/creating-value-through-business-model-innovation/

- Amstrong SJ, Hird A. Cognitive style and entrepreneurial drive of new and mature business owner-managers. Journal of Business and Psychology (2009) 2009;24(4):419–430. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9114-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aragon-Correa JA, Hurtado-Torres N, Sharma S, García-Morales VJ. Environmental strategy and performance in small firms: A resource-based perspective. Journal of Environmental Management, January 2008. 2008;86(1):88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asheghi-Oskooee H. Development of individual’s entrepreneurship abilities with special educations in short-term. In: Dameri RP, Garelli R, Resta M, editors. Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship: ECIE 2015. Academic Conferences and Publishing; 2015. pp. 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D. (2007). The entrepreneurial society. Oxford University Press.

- Audretsch, D. B., Falck, O., Heblich, S., & Lederer, A. (2012). Handbook of research on Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Altinay, L., & Wang, C. L. (2011). The influence of an entrepreneur's socio-cultural characteristics on the entrepreneurial orientation of small firms. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 18(4), 673–694. 10.1108/14626001111179749

- Bakar, L. A., & Zainol, F. A. (2015). Vision, innovation, pro-activeness, risk-taking and SMEs performance: A proposed hypothetical relationship in Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Economics and Management Sciences 2015, 4(1). 10.6007/IJAREMS/v4-i1/1665

- Balazs K. Take one entrepreneur: The recipe for success of France’s great chefs. European Management Journal, June 2002. 2002;20(3):247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Banga, R., Kumar, D., & Cobbina, P. (2015). Trade-led regional value chains in sub-Saharan Africa: case study on the leather sector. In Commonwealth trade policy discussion papers 2015/02. Commonwealth Secretariat. 10.14217/5js6b1l2tf7f-en

- Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2017). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2). 10.5465/3069456

- Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Kirkpatrick, S. (1998). A longitudinal study of the relation of vision and vision communication to venture growth in entrepreneurial firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 43–54. 10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.43

- Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics Review 7: Correlation and regression. Critical Care. 2003;7:451. doi: 10.1186/cc2041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerke, B. (2007). Understanding entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Blanchard K. Innovation and strategy: Does it make a difference! A linear study of micro & SMEs. International Journal of Innovation Studies. 2020;4(4):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijis.2020.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bless, C., Higson-Smith, C., & Kagee, A. (2009). Fundamentals of social research methods: An African perspective. Juta & Co. Ltd..

- Carland, J. W., Carland, J. A., & Ensley, M. (2002). Hunting the Heffalump: the theoretical basis and dimensionality of the Carland Entrepreneurial Index. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(2), 51–84. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/aejvol7no22001.pdf

- Chai DS, Hwang SJ, Joo B. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment in teams: The mediating roles of shared vision and team-goal commitment. Performance Improvement Quarterly. 2017;30(2):137–158. doi: 10.1002/piq.21244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chi-hsiang C. Effects of Shared vision and integrations on entrepreneurial performance. Chinese Management Studies. 2015;9(2):150–175. doi: 10.1108/CMS-04-2013-0057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T. Measuring business model innovation: Conceptualization, scale development, and proof of performance. R&D Management 2017. 2016;47(3):385–403. doi: 10.1111/radm.12186/pdf. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. Sustainable valley entrepreneurial ecosystems. Business Strategy and the Environment. 2005;15(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/bse.428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

- Dinh, H. T., & Clarke, R. G. G. (Eds.). (2012). Performance of manufacturing firms in Africa: An empirical analysis. World Bank https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11959

- Donkor J, Donkor GNA, Kankam-Kwarteng C, Aidoo E. Innovative capability, strategic goals and financial performance of SMEs in Ghana. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 2018;12(2):238–254. doi: 10.1108/APJIE-10-2017-0033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ensley MD, Carland JW, Carland JC. Investigating the existence of the lead entrepreneur. Journal of Small Business Management. 2000;38(4):59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Falbe, C. M., & Larwood, L. (1995). The context of entrepreneurial vision. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, 1995 Edition.https://fusionmx.babson.edu/entrep/fer/papers95/falbe.htm

- Gagne M. From strategy to action: Transforming organizational goals into organizational behaviour. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2018;20:93–104. doi: 10.1111/ijmr.12159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garson, D. G., & Statistical Associates Publishing (SAP). (2012). Testing Statistical Assumptions. Statistical Associates Publishing http://www.statisticalassociates.com/assumptions.pdf

- George B, Walker RM, Monster J. Does strategic planning improve organizational performance? A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review. 2019;79(6):810–819. doi: 10.1111/puar.1304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E. L., Kerr, W. R., & Ponzetto, G. A. M. (2009). Clusters of entrepreneurship. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1), 150–168. 10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.008

- Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM. When to use and how to report the results of partial least squares – structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) European Business Review. 2019;33(1):224. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E. R., Moon, Y., & Mogollon, M. P. (2015). Kenya - Leather industry: Diagnosis, strategy, and action plan. World Bank Group http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/397331468001167011/Kenya-Leather-industry-diagnosis-strategy-and-action-plan

- Heikkilä M, Bouwman H, Heikkilä J. From Strategic goals to business model innovation paths: An exploratory study. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. 2018;25(1):107–128. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-03-2017-0097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henseler J, Hubona G, Ray PA. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data systems. 2016;116(1):2–20. doi: 10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R. D., Peters, M. P., & Shepherd, D. A. (2009). Entrepreneurship (African ed.). McGraw-Hill Custom Publishing.

- Ilouga SN, Hikkerova L, Sahut JM. Behavior of entrepreneurs and volition. In: Zbuchea A, Nikoladis D, Ferreira DM, editors. Responsible entrepreneurship - vision, development and ethics, Proceedings of the 9thInternational Conference for Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Regional Development (ICEIRD): June 23-24 2016. Communicare; 2016. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- International Trade Centre [ITC] (2011). COMESA Regional Strategy for the Leather Value Chain – Medium Term 2012 – 2016 (Draft). www.intracen.org/Workarea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=68765

- Jain RK. Entrepreneurial competencies: A meta-analysis and comprehensive conceptualization for future research. SAGE Publications. 2011;15(2):127–152. doi: 10.1177/097226291101500205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantabutra S. Toward a behavioural theory of vision in organizational settings. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal. 2008;30(4):319–337. doi: 10.1108/01437730910961667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kantabutra S, Avery GC. The power of vision: Statements that resonate. Journal of Business Strategy. 2010;31(1):37–45. doi: 10.1108/02756661011012769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanyangale M. Exploring the Strategic leadership of small and medium size entrepreneurs in Malawi. Journal of Contemporary Management. 2017;14(1):482–508. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, L., Walters, H., Pikkel, R., & Quinn, B. (2013). Ten types of innovation: The discipline of building breakthroughs. John Wiley & Sons, Inc..

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics [KNBS]. (2019). Economic survey 2019. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics http://www.knbs.or.ke

- Kollmann T, Stockmann C. Filling the entrepreneurial orientation-performance gap: The mediating effects of exploratory and exploitative innovations. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2012;38(5):1001–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00530.x/full. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, C. R., & Gaurav, G. (2014). Research methodology: methods and techniques (3rd ed.). NewAge International Limited Publishers.

- Kraus, S., Rigtering, J. P. C., Hughes, M & Hosman, V. (2012). Entrepreneurial orientation and the business performance of SMEs: A quantitative study from the Netherlands. Review of Managerial Science, 6(2), 161-182. 10.1007/s11846-011-0062-9

- Kreiser PM, Marino LD, Kuratko DF, Weaver KM. Disaggregating entrepreneurial orientation: The non-linear impact of innovativeness, pro-activeness and risk-taking on SME performance. Small Business Economics. 2012;40:273–291. doi: 10.1007/s11187-012-9460-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuratko, D. F. (2014). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process and practice (9th ed.). South-Western, Thomson Learning.

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions (Abstract). Journal of Business Venturing, September–November 2000, 15(5–6), 411–432. 10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Lans T, Verstegen J, Mulder M. Analyzing, pursuing and networking: Towards a validated three-factor framework for entrepreneurial competence from a small firm perspective. International Small Business Journal. 2011;29(6):695–713. doi: 10.1177/0266242610369737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leiblein, M. J., & Reuer, J. J. (2020a). Foundations and futures of strategic management. Strategic. Management Review, 1(1). .

- Leiblein, M. J., & Reuer, J. J. (2020b). Foundations and futures of strategic management. Strategic. Management Review, 1(1).

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2006). New directions in goal-setting theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 265–268. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x [DOI]

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172. 10.2307/258632

- Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (2001). Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. (Abstract). Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 429–451. 10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

- Lumpkin GT, Frese M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2009;33(3):761–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmudova, L. & Koviacs, J. K. (2018). Defining the Performance of small and medium enterprises. Network Intelligence Studies, VI(12), 111- 120. https://seaopenresearch.eu/Journals/articles/NIS_12_5.pdf

- Mayfield, J., Mayfield, M., & Shrabrough III, W. C. (2014). Strategic vision and values in top leaders’ communications: motivating language at a higher level. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(1), 97–121. 10.1177/2329488414560282

- McMullan WE, Kenworthy TP. Creativity and entrepreneurial performance- A general scientific theory. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2015;24:419. doi: 10.1007/s10869-009-9114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, H., Mudungwe, N., & Mwinyihinja, M. (2014). A quantitative analysis determining the performance of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in leather footwear production in selected Common Market for Eastern and Southern African (COMESA) Countries. (Abstract). Journal of Africa Leather and Leather Products Advances, 1(1), 1–23. 10.15677/jallpa.2014.v1i1.6

- Ming C, Yang Y. Typology and performance of new ventures in Taiwan: A model based on opportunity recognition and entrepreneurial creativity. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. 2009;15(5):398–414. doi: 10.1108/13552550910982997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Industrialization Trade and Cooperatives [MOIT&C] (2016). Kenya’s Industrial Transformation Programme. Webpage. Ministry of Industrialization Trade and Cooperatives. http://www.industrialization.go.ke/index.php/downloads/282-kenya-s-industrial-transformationprogramme

- Mohammed K, Ibrahim HI, Shah KAM. Empirical evidence of entrepreneurial competencies and firm performance: A study of women entrepreneurs of Nigeria. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Knowledge. 2017;5(1):49–61. doi: 10.1515/ijek-2017-0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwinyihija M. Evaluation of competitiveness responses from the leather value chain strata in Kenya. Research in Business and Management. 2015;2(1):1–24. doi: 10.5296/rbm.v2i1.xxxx. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mwinyihija, M. (2016). The transformational initiative of Africa’s leather sector dependence from commodity to value created agro-based products. Journal of Africa Leather and Leather Products Advances, 3(2), 1–15. 10.15677/jallpa.2016.v3i2.13

- Ndubisi, O. N., & Iftikhar, K. (2012). Relationship between entrepreneurship, innovation and performance: comparing small and medium-size enterprises. (Abstract). Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 14(2), 214–236. 10.1108/14715201211271429

- Neuman, W. L. (2009). Understanding research. Pearson Education, Inc..

- Ngugi JK, Mcorege MO, Muiru JM. Influence of innovativeness on growth of SMEs in Kenya. International Journal of Business and Social Research (IJBSR) 2013;3(1):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Puhakka, V. (2002). Entrepreneurial business opportunity recognition. relationships between intellectual and social capital, environmental dynamism, opportunity recognition behavior, and performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Finland: University of Vaasa.

- Rajapathirana RPJ, Hui Y. Relationship between innovation capability, innovation type, and firm performance. journal of. Innovation & Knowledge. 2018;3(1):44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch A, Wiklund J, Lumpkin GT, Frese M. Entrepreneurial orientation and business performance: An assessment of past research and suggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. 2009;33(3):761–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00308.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roach DC, Ryman J, Makani J. Effectuation, innovation and performance in SMEs: An empirical study. European Journal of Innovation Management. 2016;19(2):214–238. doi: 10.1108/EJIM-12-2014-0119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvio A, Lazarowits RH, Rozenblatt Z. Entrepreneurial leadership vision in non-profit vs. for-profit organizations. The Leadership Quarterly. 2010;21:144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez J. The influence of entrepreneurial competencies on small firm performance. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología. 2012;44(2):165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Santos JB, Brito LAL. Toward a subjective measurement model for firm performance. Brazilian Administration Review. 2012;9(Special Issue):95–117. doi: 10.1590/S1807-76922012000500007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shane S. Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organisation Science. 2000;11(4):448–469. doi: 10.1287/orsc.11.4.448.14602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skrt B, Antoncic B. Strategic planning and small firm growth: An empirical examination. Managing Global Transitions. 2004;2(2):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, U., Hart, M., & Drews, C.-C. (2015). Understanding motivations for entrepreneurship: A review of recent research evidence. Enterprise Research Centre

- Tacer B, Ruzzier M, Nagy T. User-driven innovation: Scale development and validation. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 2018;31(1):1472–1487. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2018.1484784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voeten, J. (2017). Innovation in manufacturing SMEs in Kenya, Ghana and Tanzania: A grounded view on the research and policy Issues (Book Chapter). Entrepreneurship in Africa, 123–145.10.1163/9789004351615_007

- Wiklund J, Shepherd D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized business. Strategic Management Journal. 2003;24:1307–1314. doi: 10.1002/smj.360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund J, Shepherd D. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configuration approach. Journal of Business Venturing. 2005;20(1):71–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zainol FA, Daud WNW, Abubakar LS, Shaari H, Halim HA. A Linkage between entrepreneurial leadership and SMEs performance: An integrated review. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 2018;8(4):104–118. doi: 10.6997/IJARBSS/v8-i4/4000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for this study are available from the author upon reasonable request. The author retains copyright for the data and materials used in the study except where sources are acknowledged.

Coding as used in context of data entry meant manually transforming response data to 5-point Likert scale values.