Abstract

We compared the community structures of cyanobacteria in four biological desert crusts from Utah's Colorado Plateau developing on different substrata. We analyzed natural samples, cultures, and cyanobacterial filaments or colonies retrieved by micromanipulation from field samples using microscopy, denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. While microscopic analyses apparently underestimated the biodiversity of thin filamentous cyanobacteria, molecular analyses failed to retrieve signals for otherwise conspicuous heterocystous cyanobacteria with thick sheaths. The diversity found in desert crusts was underrepresented in currently available nucleotide sequence databases, and several novel phylogenetic clusters could be identified. Morphotypes fitting the description of Microcoleus vaginatus Gomont, dominant in most samples, corresponded to a tight phylogenetic cluster of probable cosmopolitan distribution, which was well differentiated from other cyanobacteria traditionally classified within the same genus. A new, diverse phylogenetic cluster, named “Xeronema,” grouped a series of thin filamentous Phormidium-like cyanobacteria. These were also ubiquitous in our samples and probably correspond to various botanical Phormidium and Schizothrix spp., but they are phylogenetically distant from thin filamentous cyanobacteria from other environments. Significant differences in community structure were found among soil types, indicating that soil characteristics may select for specific cyanobacteria. Gypsum crusts were most deviant from the rest, while sandy, silt, and shale crusts were relatively more similar among themselves.

Biological desert crusts (also known as cyanobacterial, algal, cryptobiotic, microbiotic, or cryptogamic crusts) are ecologically important soil microhabitats of cold and hot arid lands (3). These topsoil formations are initiated by the growth of cyanobacteria during episodic events of available moisture with the subsequent entrapment of mineral particles by the network of cyanobacterial filaments or by the matrix of extracellular slime (2, 9, 21). Eventual undisturbed development may lead to the establishment of important bacterial, fungal, algal, lichen, and moss populations. Biological desert crusts are thought to play important roles in the biogeochemistry and geomorphology of arid regions (reviewed in references 13 and 14). Cyanobacteria, which are known to inhabit a variety of soil and rock desert microhabitats (16, 33), are typically the first colonizers of bare arid soils and are ubiquitous in all desert crusts except those of low pH.

Mechanistic explanations of desert crust function require a solid basis of knowledge about the organismal community that builds them. While floristic studies of desert crust cyanobacteria exist (7, 8, 12, 15), several factors may restrict the value of such studies. Preliminary cultivation is often needed for enumeration and taxonomic determinations of soil algae at large, but it is well known that this procedure may result in the spurious preferential enrichment of fast-growing strains. On the other hand, the coexistence of several botanical (for examples, see references 1 and 19) and one bacteriological taxonomic treatment for the cyanobacteria make identification extremely difficult unless a single system is adopted, and cross-referencing becomes a painstaking task. Additionally, modern molecular methods of community analysis have shown that specific morphotypes may (32) or may not (18) conceal hidden diversity, depending on each specific case. The analysis of microbial diversity in natural communities thus needs a polyphasic approach that combines the use of traditional and molecular techniques of community diversity characterization. This has been successfully carried out in marine cyanobacterial assemblages (25, 26), but no such studies exist for terrestrial cyanobacteria. At all taxonomic levels above species, sequence analysis of genes encoding small-subunit rRNA (16S rRNA) is currently the most promising approach for the phylogenetic classification of cyanobacteria, and the comparative analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences provides a new means to investigate the discrepancy between strain collections and natural communities (17, 18).

Here we present results of a polyphasic study of the cyanobacterial communities growing on four different soil desert crusts form Arches National Park, Utah. We have combined the use of environmental 16S rRNA gene analyses, microscopy, and cultivation to characterize their cyanobacterial components and to probe the importance of the soil substrate in determination of community structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used four cyanobacterial desert crusts, which, on inspection under a dissecting microscope, contained virtually no lichen or moss populations. They were all obtained from Arches National Park in the Colorado Plateau and differed markedly with regard to the type of soil substratum. They included crusts from sandy soil, from alluvial silts (referred to herein as “silt”), from Manco shales (“shale”) and from gypsiferous outcrops (“gypsum”). After collection, samples were transported and kept dry until analyses. In addition to these samples, standard cultivated strains isolated from desert crusts were also analyzed for comparison and guidance. These included three unicyanobacterial strains (MPI 98MV.JHS, MPI 98SCH.JHS, and MPI 98NO.JHS) obtained from desert crusts in Joshua Tree National Monument, Calif. (a gift from J. Johansen, John Carroll University), one unicyanobacterial strain from the culture collection of algae at the University of Göttingen isolated from desert crusts in Israel (SAG 2692), two strains isolated by one of us (F.G.P.) from a carbonaceous silt crust in Spain (MPI 99OBR03 and MPI 99MVBR04), and one strain (MPI 96MS.KID) obtained from desert crusts in Israel (a gift from B. Büdel, University of Kaiserslautern). Finally, a macroscopic thallus of Nostoc commune var. flagelliforme collected from Chihuahuan Desert soils in Arizona was also analyzed.

Microscopy, micromanipulation, and culturing.

Dry crusts were reactivated by addition of distilled water immediately before analyses and incubated in the light. A preliminary determination of the major cyanobacterial morphotypes present and of their relative abundance was carried out by direct microscopy of wet samples. The uneven distribution of morphotypes and the presence of mineral particles prevented a quantitative assessment of relative biomass. Special attention was given to documenting and quantifying morphologic traits diacritical in the botanical species description (cell shape, width, and length of the cells, trichome width, shape of both intercalary and end cells, presence of sheaths, pigmentation, heterocyst development, etc.)

Micromanipulation of the samples under the dissecting microscope with watchmaker's forceps and pulled capillary pipettes was used to physically isolate colonies, filaments, or bundles of filaments belonging to conspicuous cyanobacterial morphotypes. Isolated colonies or bundles were further separated and cleaned by dragging them over agarose-solidified medium as previously described (18). These cleaned microsamples were observed under the compound microscope to confirm the presence of only one morphotype. Monomorphotypic microsamples were either incubated in liquid culture media (see below), used for PCR amplification, or both; DNA sequences obtained in this manner are referred to as “picked” (Table 1). The culture medium was either BG11 (30) or Z8 (11). Unicyanobacterial strains MPI98XC09 and MPI98X10 were obtained in this manner. A strain corresponding morphologically to the botanical description of Microcoleus vaginatus was obtained in axenic culture and deposited in the Pasteur Culture Collection of Cyanobacteria (PCC) under the designation PCC 9802.

TABLE 1.

Environmental and cultural rRNA gene sequences determined during this study

| GenBank accession no. | Environmental sequence or strain no.a | Crust and location | Method | Length (bp) | Corresponding bandb or taxonomic assignmentc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF284790 | AL09 | Silt, Utah | Pickedd | 323 | 5a |

| AF284791 | AL10 | Gypsum, Utah | Pickedd | 326 | 6a |

| AF284792 | AL13 | Shale, Utah | Picked | 335 | 2a |

| AF284793 | AL14 | Silt, Utah | Picked | 327 | 3a |

| AF284794 | AL15 | Sandy soil, Arizona | Picked | 326 | |

| AF284795 | AL18 | Silt, Utah | DGGE | 328 | 16b |

| AF284796 | AL21 | Silt, Utah | DGGE | 326 | 16c |

| AF284797 | AL22 | Shale, Utah | DGGE | 326 | 7a |

| AF284798 | AL23 | Sandy soil, Utah | DGGE | 325 | 11a |

| AF284799 | AL24 | Sandy soil, Utah | DGGE | 324 | 11c |

| AF284800 | AL25 | Sandy soil, Utah | DGGE | 326 | 11b |

| AF284801 | AL26 | Gypsum, Utah | DGGE | 326 | 13a |

| AF284802 | AL28 | Gypsum, Utah | Picked | 327 | |

| AF284803 | PCC 9802 | Sandy soil, Utah | 1,430 | M. vaginatus | |

| AF284804 | MPI98MVBR04 | Unknown, Carbonate/silt, Spain | 623 | M. vaginatus | |

| AF284805 | MPI98MV.JHS | Unknown, California | 620 | M. vaginatus | |

| AF284806 | MPI98SCh.JHS | Unknown, California | 610 | Phormidium/Schizothrix | |

| AF284807 | MPI98NO.JHS | Unknown, California | 530 | Nostoc sp. | |

| AF284808 | SAG 2692 | Unknown, Israel | 628 | M. sociatus | |

| AF284809 | MPI96MS.Kid | Unknown, Israel | 652 | M. sociatus | |

| AF284810 | MPI99OBR03 | Carbonate/silt, Spain | 606 | Oscillatoria sp. |

MPI, Max-Planck-Institut culture collection, Bremen, Germany; SAG, Sammlung von Algenkulturen, Göttingen, Germany.

DGGE band in Fig. 2.

Taxonomic assignments are cum forma and do not necessarily imply that a phylogenetically coherent taxon can be defined for the morphology described by the taxon.

Single-filament picking was followed by incubation in culture medium to obtain a small pellet before PCR amplification.

Extraction of bulk DNA from desert crust samples.

Cell lysis and bulk DNA extraction were performed essentially as described previously (26), with the following modifications. Approximately 3 g of dry desert crust (2 to 3 mm thick) was ground in a mortar under liquid N2. The macerated samples were placed in a 50-ml plastic tube to which 10 ml of TESC buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 100 mM EDTA, 1.5 M NaCl, 1% [wt/vol] hexadecylmethylammonium bromide), 550 μl of 10% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 30 μl of proteinase K at 20 mg/ml were added. Incubation for 20 min at 50°C followed. Chromosomal DNAs were extracted for 5 min at 65°C in 1 volume (10 ml) of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitated by the addition of isopropyl alcohol for 30 min at room temperature.

PCR amplifications.

PCR amplifications were performed with a Cyclogene temperature cycler (Techne, Cambridge, United Kingdom) using previously described cyanobacterium- and plastid-specific primers (28). The oligonucleotide primers CYA 359F and CYA 781R were applied to selectively amplify cyanobacterial 16S rRNA gene segments from bulk DNA. These primers yield amplification products up to 450 bp in length. Primers CYA 106F and CYA 781R were used to specifically generate amplification products from cyanobacteria in unialgal cultures, yielding fragments ca. 600 bp in length. For axenic strain PCC 9802, its nearly complete gene was amplified using primers 8F (6) and 1528R (17). Regardless of the primers used, 50 pmol of each primer, 25 nmol of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 μg of bovine serum albumin, 10 μl of 10× PCR buffer (100 mM Tris HCl [pH 9.0], 15 mM MgCl, 500 mM KCl, 1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 0.1% [wt/vol] gelatin), and 10 ng of template DNA (extracted either from desert crust samples, from cultures, or from denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis [DGGE] bands excised from gels—see below) were combined with H2O to a volume of 100 μl in a 0.5-ml test tube and overlaid with 2 drops of mineral oil (Sigma Chemical Co., Ltd.). To minimize nonspecific annealing of the primers to nontarget DNA, 0.5 U of SuperTaq DNA polymerase (HT Biotechnology, Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) was added to the reaction mixture after the initial denaturation step (5 min at 94°C), at 80°C for 1 min. Thirty-five incubation cycles followed, each consisting of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 1 min at 72°C, and a last cycle of 9 min at 72°C. A 40-nucleotide GC-rich sequence, referred to as a GC clamp, was attached to the 5′ end of primer CYA 359F to improve the detection of sequence variation in amplified DNA fragments by subsequent DGGE (see below).

DGGE analyses.

DGGE involves the separation of a population of DNA segments of equal length in a polyacrylamide gel containing a gradient of denaturants. The separation is based on differences in melting characteristics of the double-stranded segments, which are in turn dependent upon sequence differences. The result is the simultaneous detection of 16S rRNA molecules as a pattern of bands. For DGGE analysis of bulk DNA, mixed amplification products generated by duplicate PCRs with the same template DNAs were pooled and subsequently purified and concentrated by using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Diagen, Düsseldorf, Germany). The DNA concentration in the resulting solution was determined by comparison to a low-DNA-mass standard (Gibco, Eggenstein, Germany) after agarose gel electrophoresis; 500 ng of DNA was applied to denaturing gradient gels. DGGE was performed as described previously (28). Briefly, polyacrylamide gels with a denaturing gradient from 20 to 60% were used, and electrophoreses were run for 3.5 h at 200 V. Subsequently, the gels were incubated for 30 min in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA) containing 20 mg of ethidium bromide/ml. Fluorescence of dye bound to DNA was excited by UV irradiation in a transilluminator and was photographed with a Polaroid MP4+ instant camera system. Well-separated bands were carefully excised from the gels using a sterile surgical scalpel and used for reamplification and sequencing. For this, each excised band was placed in 20 μl of TAE buffer and allowed to diffuse out of the gel for several days. The solution was then used as a template for PCR amplification as described above.

Sequencing.

PCR products were purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Diagen) and were subsequently used as templates for sequencing reactions with the Applied Biosystems PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing Ready Reaction kit supplied with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. Both DNA strands were sequenced using primers 8F, 1099 F, 1175R (6), 341R, and 1528 (17) in the case of almost complete sequences. For partial sequences, the primers used for initial amplification were used. Products of sequencing reactions were sequenced commercially.

Phylogenetic reconstruction.

Cyanobacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences available from GenBank and those determined in this study were aligned to the sequences in the database of the software package ARB (23), available at http://www.mikro.biologie.tu.muenchen.de. Alignment positions at which one or more sequences had gaps or ambiguities were omitted from the analysis. A phylogenetic tree was constructed on the basis of almost complete sequences only (from nucleotide positions 49 to 1389 in the Escherichia coli numbering of reference 5). The maximum-likelihood, maximum-parsimony, and neighbor-joining methods as integrated in the ARB software were applied for tree construction. Partial sequences were integrated in the tree without allowing it to change its topology according to the maximum-parsimony criterion, using the appropriate ARB subroutine.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study were deposited in GenBank, and their accession numbers are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS

Diversity of morphotypes

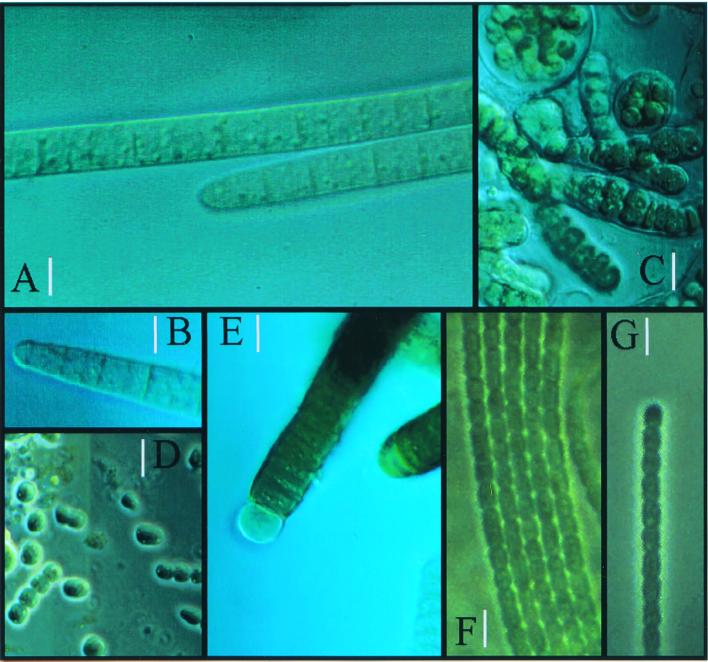

On microscopic observation of wetted samples we distinguished six different cyanobacterial morphotypes. Although a few small lichen thalli (Collema spp.) and one moss frond were also observed, these are not discussed here. The morphotypes are listed in Table 2 together with their corresponding (botanical) taxonomic assignment and a qualitative indication of their relative abundance. The crust from alluvial silt showed the most diverse cyanobacterial assemblages, followed by those of gypsum, sandy soil, and shale, in that order. Colonies and filaments of morphotypes corresponding to Nostoc sp. and Scytonema sp. were observed at the very surface of the crust. M. vaginatus-like morphotypes dominated all crusts except gypsum. Together with Schizothrix-like morphotypes, they were originally immediately below the surface, although both easily migrated towards the surface after several hours of wetting (4, 10). Phormidium-like morphotypes were found mostly within or around the sheaths of M. vaginatus-like bundles and other cyanobacteria. In long-term enrichment cultures, Phormidium-like and Chlorogloeopsis-like cyanobacteria could be detected. Photomicrographs of some of these morphotypes are shown in Fig. 1. We could not directly observe any diatoms or green algae in our samples, although colonies of unicellular green algae and bryophytan protonemae did grow on old enrichments, indicating that inocula must have been present at low density.

TABLE 2.

Cyanobacterial morphotypes distinguished in the four crusts

| Morphotype (main characteristics) | Assignment per Geitler (19) | Abundancea in

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandy soil | Shale | Gypsum | Silt | ||

| Ensheathed, bundle-forming filaments, nonheterocystous; trichomes 4–6 μm wide; no constrictions at cross-walls; cells quadratic, 5–7 μm long; necridia present; apical cells with calyptra | M. vaginatus (Gomont) | ++++ | ++ | − | ++++ |

| Ensheathed, bundle-forming filaments, nonheterocystous; trichomes 2.5–5 μm wide; cells 2.5–4 μm wide; slightly constricted at cross-walls; apical cells conical; sheath colorless or with scytonemin | Schizothrix spp. | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Single filaments, nonheterocystous; trichomes 1.2–2.5 μm wide; barrel-shaped, isodiametric cells; round apical cells | Phormidium spp. | + | − | ++ | + |

| Heterocystous filamentous; lamellated, brown sheath; filaments 10–15 μm wide; trichomes 8–11 μm wide; cells disc-shaped, 3–5 μm wide; terminal and intercalary heterocysts | Scytonema sp. | + | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Heterocystous filamentous; short chains of spherical cells, 3.5–5 μm in diam; confluent gel holds trichome masses in spherical dark-brown colonies 90–500 μm in diam | Nostoc sp. | − | − | +++ | +++ |

| Heterocystous, disorderly masses of cells forming spherical colonies with tight, clored sheaths; upon cultivation, filaments with true branching formed; cells 3.5–7 μm wide | Chlorogloeopsis sp. | − | − | − | + |

++++, dominant; +++, very common; ++, common; +, present; −, not detected.

FIG. 1.

Diversity of cyanobacterial morphotypes from desert crusts. (A and B) Details of trichome morphology of M. vaginatus; (C) Chlorogloeopsis sp., enrichment culture from Nostoc-like field colonies; (D) Nostoc cells and short filaments after incubation and disruption of natural sample; (E) Scytonema sp. after incubation of natural sample; (F and G) cyanobacterial trichomes belonging to the “Xeronema” cluster (Phormidium and Schizothrix). Bars, 4 μm (A, B, F, and G) and 8 μm (C, D, and E).

Molecular diversity of 16S rRNA genes

A DGGE separation of bulk cyanobacterial 16S rRNA genes from the four desert crust types is presented in Fig. 2 (lanes 7 to 18). The band patterns obtained were similar among replicates from each crust type but clearly different among crust types. New bands appeared only in some cases after repeated sampling (e.g., band c of alluvial silts appeared only in lane 16 but not in lanes 17 and 18). In general, replicability in the relative intensity of bands was also high. Under the PCR conditions used here, which avoided reaching critical concentrations of PCR products, band intensity should be indicative of the original abundance of the template DNAs in the original extractable population, although other factors, such as widely varying G+C content in the target DNA, primer degeneration, or the presence of novel target sequences noncomplementary to the primers, may still cause bias (26). Crusts from gypsum yielded small amounts of DNA and low band richness (five bands). In contrast, crusts from shale, sandy soil, and silt yielded similar amounts of DNA and seven to nine bands. A major, intense band (band 7a) was conspicuous in all but the gypsum crusts. It comigrated in all cases with those obtained from amplification of picked M. vaginatus-like morphotypes (Fig. 2, lanes 2 to 4), a first strong indication that M. vaginatus-like morphotypes correspond to a single 16S rRNA sequence and that they are dominant in most crusts. In gypsum crusts, this band was only faint. Other bands comigrating in several crust types could be detected, such as band 16c of silt, which was also present in sandy soil crusts. Bands comigrating with 16S rRNA fragments from cultures of Phormidium-like morphotypes were detected in field DNA. Band 6a, obtained from a gypsum enrichment, comigrated with bands in extracts from silt and from sandy soil crusts but not with bands in extracts from shale crusts. Band 5a, obtained from a sandy soil enrichment, comigrated with bands from sandy soil (band 11a) and from silt (band 16a). Finally, some intense bands were crust specific, such as band 11c, which was detected only in sandy crusts, and band 13b, which was present only in gypsum.

FIG. 2.

DGGE separation of PCR-amplified cyanobacterial 16S rRNA genes obtained from various desert crusts (lanes 7 to 18) and from unicyanobacterial samples physically isolated therefrom (lanes 2 to 6). A mixture of PCR products derived from five cyanobacterial strains was applied as a standard (STD) (from top to bottom: Scytonema B-77-Scy. jav., Synechococcus leopoliensis SAG 1402-1, M. chthonoplastes MPI-NDN-1, Geitlerinema PCC 9452, and Cyanothece PCC 7418). Lanes 2 to 4 contain DNA amplified from single bundles of filaments retrieved directly from the corresponding crusts by micromanipulation and morphologically corresponding to the description of M. vaginatus. Lanes 5 and 6 contain DNA amplified from enrichment cultures obtained after incubation of single filaments. Separations of triplicate extraction and amplification of whole-community DNA in shale crusts, sandy crusts, gypsum crusts, and alluvial silt crusts were done. For each group of three replicate lanes, arrowheads to the left of the group indicate positions in the gradient at which defined bands could be distinguished in at least one of the triplicates. Letters to the right of each lane correspond to bands that could be excised, PCR amplified, and sequenced successfully (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Phylogeny reconstructions based on environmental sequences and cultured strains.

An analysis of the phylogenetic relationships of sequences obtained from reamplified DGGE bands, from picked field material and from cultured isolates is presented in Fig. 3. Sequences obtained in this way fall within six distinct cyanobacterial clusters, five of which are novel groupings. Cultivated representative strains of all clusters but cluster B are available. Cluster B is based entirely on environmental sequences.

FIG. 3.

Distance tree of the cyanobacteria constructed on the basis of almost complete 16S rRNA gene sequences (more than 1,400 nucleotides, in black). Evolutionary distances were determined by the Jukes-Cantor equation, and the tree was calculated with the neighbor-joining algorithm. The 16S rRNA gene sequence from Escherichia was used as an outgroup sequence. Partial sequences (ca. 325 nucleotides [red] and ca. 610 nucleotides [blue]) were integrated into the tree by applying a parsimony criterion without disrupting the overall tree topology established beforehand. Sequence designations for environmental sequences (in orange) correspond to those in Table 1. The tree has been simplified by collapsing coherent clusters of strains into boxes of fixed height. In each box, the shortest and longest sides depict the minimal and maximal distance to the common node of all sequences contained within the cluster. Each of the six clusters of interest in this study is shown in detail on the left. Clusters in red are composed exclusive of desert crust cyanobacterial sequences. All entries are named after database labels, without taxonomic considerations.

The first and perhaps most clearly defined cluster is the M. vaginatus cluster (Fig. 3). It contains one full 16S rRNA sequence, two ca.-600-bp long sequences from isolated strains, and three ca.-300-bp environmental sequences from field picked samples, all of them conforming to the morphologic description of M. vaginatus Gomont. The latter two sequences correspond to bands 2a and 3a in Fig. 2. All of these sequences were virtually identical and only distantly related to those of other nonheterocystous filamentous cyanobacteria with large trichomes, such as marine Trichodesmium spp., Lyngbya PCC 7419, and the Arthrospira cluster (24). However, an almost complete match (99.4% in overlapping regions) was also found between our sequences and a 490-bp 16S rRNA gene fragment from strain NIVA CYA-203 of the Norwegian Institute for Water Research Algal Collection (31). This strain is a blue-green, oscillatorian, terrestrial isolate from Coraholmen, Spitsbergen, Svalbard (Norway), tentatively identified as Phormidium, with a trichome width of 5 μm, which develops necridic cells (O. Skulberg, personal communication). While it was not made available to us for inspection, the information on NIVA CYA-203 ecology and morphology certainly is congruent with that of our strains and picked samples. An interesting feature in this cluster was the presence of a consensus insert in all sequences, between E. coli positions 463 and 468. This 17-bp insert (AAGUUGUGAAAGCAACC) replaced here the variable region of 5 to 6 bp present in other cyanobacteria (ANNNNN, consensus for Trichodesmium spp; ACACAA, consensus for the Arthrospira spp.; ANNCC, consensus for members of the Halothece cluster). The sequences showed no significant relationship to other phylogenetically well-defined clusters assigned to the botanical genus Microcoleus (Desmazières), like the one formed by marine benthic Microcoleus chthonoplastes.

A second cluster was obtained that contained exclusively cyanobacterial sequences from desert crusts. This was based on four ca.-300-bp long environmental sequences (two from reamplified DGGE bands and two from picked or enriched Phormidium-like filamentous cyanobacteria) and one ca.-600-bp long sequence from strain MPI 98SCH.JHS, also displaying a Phormidium-like morphology. This cluster fell quite distant from other Phormidium/Pseudanabaena/Leptolyngbya-like strains in the database and was closest to marine and freshwater unicellular forms. Because of this, the cluster needs a differentiating epithet. We chose the name “Xeronema” (from the Greek “xeros,” dry, and “nema,” filament) for this cluster. In contrast to the M. vaginatus cluster, the “Xeronema” cluster showed considerable sequence divergence.

Cluster A was a relatively tight association of sequences, well separated from its nearest neighbors, the cluster of heterocystous cyanobacteria and cluster C. It contained two 600-bp-long sequences from two culture collection strains assigned to the botanical species Microcoleus sociatus and a ca.-300 bp-long sequence obtained from bundle-forming filamentous cyanobacteria picked from short-term enrichments of gypsum crusts. Because we cannot associate any sequences within cluster A with bands in our DGGE analysis, its importance in Utah crust remains unexplored. However, morphotypes of M. sociatus have been described to be the most common inhabitants of some desert crusts in Israel (22); cyanobacteria within this cluster may play an ecologically significant role in arid soils. Cluster B is formed exclusively by environmental sequences obtained from reamplifications of DGGE bands. Consequently, it should be regarded as still tentative, although maximum-parsimony methods placed it deeply separated from other known strains. It is not possible to assign any putative characteristic morphotypes, although it is clear that its members are important components of our desert crust communities (e.g., strong band 11c in sandy soil). Cluster C, also well separated from its nearest neighbors, gathers three somewhat divergent sequences. One of them, ca. 300 bp long, was obtained from DGGE band 16c of silt crusts. The second one corresponds to strain MPI99BR03, an Oscillatoria-like filamentous morphotype, isolated from desert crust in Northern Spain, where it can form almost monospecific patches (F. Garcia-Pichel, unpublished observation). The third sequence, virtually complete, corresponds to strain SAG B8.92, a marine Oscillatoria fitting the description of Oscillatoria corallinae (Kützing) Gomont. It is noteworthy that newly obtained sequences from hypersaline marine microbial mats also fall within this cluster (R. Abed and F. Garcia-Pichel, submitted for publication). Thus, this cluster contains cyanobacteria of widely different ecological origins. Finally two sequences fell within the heterocystous cluster, in a tight group containing various Nostoc isolates. These corresponded to a Nostoc isolate and to a macroscopic colony of Nostoc commune. Surprisingly, no sequences belonging to the cluster of heterocystous cyanobacteria were obtained from any of the four Utah crusts, neither by direct picking (PCR amplifications failed or yielded sequences of very poor quality) nor from reamplification of DGGE bands.

DISCUSSION

Cyanobacterial dominance and diversity in desert crusts.

This work demonstrated that desert crusts are inhabited by a diverse, polyphyletic array of cyanobacteria which are underrepresented in currently available nucleotide databases. In contrast, we found no microscopic evidence for the presence of significant populations of eukaryotic algae. Molecular evidence for eukaryotic algae, in the form of DGGE bands containing sequences phylogenetically associated with algal plastids, was also lacking, even though the methodology employed has shown the importance of eukaryotic microalgae in other environments (25). This is in contrast with results of algal enumeration based on enrichment cultures, which typically yield a large variety of diatoms, green algae, and other algae from such environments (15, 21). While this apparent contradiction may stem from differences in the community composition of various samples, it is also likely that the enrichment methodology significantly distorts the importance of various algal groups by promoting the growth of wind-blown resting stages or lichen photobionts.

Much of the cyanobacterial diversity found within these crusts tends to group in discrete clusters and apart from cyanobacteria originating in other ecological settings (i.e., the M. vaginatus, the “Xeronema,” and the A and B clusters in Fig. 3). This is consistent with the view that terrestrial settings in general and desert crusts in particular represent a habitat imposing environmental constraints that have allowed the diversification of specialized cyanobacterial groups within them. These constraints may have to do with the ability to attain simultaneous physiological resistance to desiccation, intense illumination, and temperature extremes, as exemplified in studies of N. commune (29), but most of the putative specific adaptations remain to be explored. At the same time, the fact that those soil-specific phylogenetic clusters are deeply rooted and scattered in the cyanobacterial tree implies that terrestrial cyanobacteria are evolutionarily old. This is consistent with the view that desert crust-like communities may have been important terrestrial ecosystems of early Earth before the advent of higher plants (10) and with the presence of filamentous cyanobacterium-like microfossils in terrestrial settings in the mid- to-late Precambrian (20).

M. vaginatus as the dominant crust cyanobacterium.

We could clearly identify a common and usually dominant cyanobacterium in our soil desert crusts which presents a defined, conserved morphology corresponding to the botanical description of M. vaginatus Gomont. Its molecular signature was dominant in DGGE analyses, and its presence was conspicuous (Table 1) in all samples except those from gypsiferous soils. This important cyanobacterial desert crust inhabitant (2) represents an easily recognizable, phylogenetically coherent taxon. The fact that cultured isolates and field samples from geographically distant sources and from soils with different textures and chemistries resulted in highly conserved 16S rRNA sequences indicates that the cluster is likely cosmopolitan in distribution. This is a welcome result, since many of the floristic studies on its abundance and distribution based on morphologic descriptions are hereby validated, and physiological studies on axenic isolates (e.g., PCC 9802) that are representative of the field populations can now be initiated. Interestingly, according to our trees, this congruent group of terrestrial, filamentous, bundle-forming cyanobacteria are not particularly closely related to the benthic, marine cyanobacteria or hypersaline, bundle-forming cyanobacteria of the same genus (M. chthonoplastes). The genus is obviously in need of revision. Some of the common morphologic traits that may confer a competitive advantage on both the marine and the terrestrial bundle-forming cyanobacteria must have thus evolved convergently.

Community structure and soil type.

The fact that repeated sampling of a given crust only slightly increased the cumulative richness of DGGE bands for that crust (Fig. 2) indicates that the sampling size was appropriate and representative for the spatial scales (square centimeters) used in this study (27). This lends credibility to the notion that some of the major differences observed among soil types are indeed related to the physicochemical conditions in the soils, since the common geographical origin of all samples excludes major climatic or biogeographical reasons for such differences. In fact, gypsum crusts were most divergent from the rest in the microscopic, DGGE, and phylogenetic analyses. The absence or low incidence of M. vaginatus (Fig. 2; Table 1), the presence of molecular signatures close to M. sociatus strains and the apparent dominance of the community by cyanobacteria allied with the “Xeronema” cluster (Fig. 2) speak for such major differences. It is interesting to speculate that perhaps the soluble nature of the gypsum in the mineral phase, increasing the salinity of the soil solution when wet, may prevent forms like M. vaginatus to grow optimally and select for more halotolerant cyanobacteria. Indeed, cultured strains of M. vaginatus from desert crusts are reported as not being particularly resistant to salt stress (4).

The inconspicuous thin filamentous cyanobacteria.

The DGGE analysis showed that members of the “Xeronema” cluster, while not dominant, are ubiquitous and perhaps important in the cyanobacterial communities in our desert crusts. The correlation between morphology and phylogenetic signature obtained in picked and cultivated enrichments belonging to the “Xeronema” cluster, leads us to conclude that these accompanying flora encompasses a variety of taxa of thin filamentous cyanobacteria usually reported in floristic accounts as Phormidium spp. (particularly P. minnesotense) and Schizothrix spp. Further characterization of the isolates will be needed to validate the “Xeronema” cluster as a taxonomically valid unit, to probe its diversity and to describe its physiological commonalities.

The need for a polyphasic characterization.

Our analysis demonstrates that significant components of cyanobacterial biodiversity can be underestimated when a single method for community description is used. Microscopy clearly underestimated the diversity of morphologically simple, filamentous, Phormidium-like cyanobacterial forms. Molecular methods of DNA analysis, by contrast, completely failed to detect the presence of heterocystous cyanobacteria, which were conspicuous on microscopic observation. This was probably not due to a failure in the PCR amplification, or in the DGGE steps, since this methodology has been successfully employed for heterocystous cyanobacteria in culture (Nostoc spp., Scytonema sp., and Chlorogloeopsis sp.), in macroscopic thalli of N. commune, and in Nostoc cyanobionts from lichens (Table 2) (28). Heterocystous cyanobacteria develop very thick, tough extracellular sheaths in their natural environment. These extracellular investments, which provide protection from desiccation, excessive UV radiation, and erosional abrasion, probably prevented efficient extraction of their nucleic acids, even though the mechanical disruption under liquid nitrogen employed in the extraction procedure can be regarded as very efficient. The use of tougher disruption treatments, however, may also result in shear damage to the DNA and consequently reduce the overall sensitivity of the procedures. Specific treatments to remove or weaken extracellular sheaths will need to be designed in the future to study the genetic diversity of terrestrial heterocystous cyanobacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by grants from the European Commission (grant BIO-CT96-0256) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (NRICGP-00-539) to F.G.P. and by the Max-Planck Society. During the time of this study, A.L.C. participated in the Scientist's Exchange Program between Consejo Nacional de Tecnologia (CONACYT) Mexico (E130-2340) and the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) Germany (A/98/28946), 1998. A.L.C. also acknowledges travel grant ABM4/CIBNOR, 1999, from SEP-CONACYT.

We thank J. Johansen, J. Belnap, and B. Büdel for the gift of strains and O. Skulberg for information on strain NIVA CYA-230.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostidis K, Komarek J. Modern approach to the classification system of cyanophytes. 1. Introduction. Arch Hydrobiol Suppl. 1985;71:291–302. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belnap J, Gardner J S. Soil microstructure in soils of the Colorado Plateau: the role of the cyanobacterium Microcoleus vaginatus. Great Basin Nat. 1993;53:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belnap, J., and O. Lange (ed.). Biological soil crusts: structure, function and management, in press. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 4.Brock T D. Effect of water potential on a Microcoleus (Cyanophyceae) from a desert crust. J Phycol. 1975;11:316–320. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius J, Dull D, Sleeter D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz-Cleven B E E, Rattunde B, Straub K L. Screening for genetic diversity of isolates of anaerobic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria using DGGE and whole-cell hybridization. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1997;20:301–309. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron R E. Species of Nostoc Vaucher occurring in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. Trans Am Microsc Soc. 1962;81:379–384. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron R E. Terrestrial algae of Southern Arizona. Trans Am Microsc Soc. 1964;83:212–218. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cameron R E, Blank G B. Desert algae: soil crusts and diaphanous substrata as algal habitats. JPL Tech Rep. 1966;32:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell S E. Soil stabilization by a prokaryotic desert crust: implications for Precambrian land biota. Origins Life. 1979;9:335–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00926826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmichael W W. Isolation, culture and toxicity testing of freshwater cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) In: Shilov V, editor. Fundamental research in homogeneous catalysis. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Gordon and Breach; 1986. pp. 1249–1262. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dor I, Danin A. Cyanobacterial desert crusts in the Dead Sea Valley, Israel. Arch Hydrobiol Suppl. 1996;83:197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eldridge D, Greene R S. Microbiotic soil crusts—a review of their roles in soil and ecological processes in the rangelands of Australia. Austr J Soil Res. 1994;32:389–415. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans R D, Johansen J R. Microbiotic crusts and ecosystem processes. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1999;18:183–225. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flechtner V R, Johansen J R, Clark W H. Algal composition of microbiotic crusts from the central desert of Baja California, Mexico. Great Basin Nat. 1998;58:259–311. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedmann I, Lipkin Y, Ocampo-Paus R. Desert algae of the Negev (Israel) Phycologia. 1967;6:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Pichel F, Nübel U, Muyzer G. The phylogeny of unicellular, extremely halotolerant cyanobacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:469–482. doi: 10.1007/s002030050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Pichel F, Prufert-Bebout L, Muyzer G. Phenotypic and phylogenetic analyses show Microcoleus chthonoplastes to be a cosmopolitan cyanobacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3284–3291. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3284-3291.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geitler L. Cyanophyceae. Rabenhorsts Kryptogamenflora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. Leipzig, Germany: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horodyski R J, Knauth L P. Life on land in the Precambrian. Science. 1994;263:494–498. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5146.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansen J R. Cryptogamic crusts of semiarid and arid lands of North America. J Phycol. 1993;29:140–147. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lange O L, Kidron G J, Büdel B, Meyer A, Kilian E, Abeliovich A. Taxonomic composition and photosynthetic characteristics of the ‘biological soil crusts’ covering sand dunes in the western Negev Desert. Funct Ecol. 1992;6:519–527. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig W, Strunk O, Klugbauer N, Weizenegger M, Neumeier J, Blachleitner M, Schleifer K H. Bacterial phylogeny based on comparative sequence analysis. Electrophoresis. 1988;19:554–568. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelissen B, Willmotte A, Neefs J M, Wachter R D. Phylogenetic relationships among filamentous helical cyanobacteria investigated on the basis of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence analysis. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1994;17:206–210. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Clavero E, Muyzer G. Matching molecular diversity and ecophysiology of benthic cyanobacteria and diatoms in communities along a salinity gradient. Environ Microbiol. 2000;2:217–226. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2000.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Kühl M, Muyzer G. Quantifying microbial diversity: morphotypes, 16S rRNA genes and carotenoids of oxygenic phototrophs in microbial mats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:422–423. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.422-430.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Kühl M, Muyzer G. Spatial scale and the diversity of benthic cyanobacteria and diatoms in a salina. Hydrobiologia. 1999;401:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Muyzer G. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3327–3332. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3327-3332.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potts M. Desiccation tolerance of procaryotes. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:755–805. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.755-805.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rippka R, Deruelles J, Waterbury J, Herdman M, Stanier R Y. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1979;111:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudi K, Skulberg O M, Larsen F, Jacobsen K S. Strain characterization and classification of oxyphotobacteria in clone cultures on the basis of 16S rRNA sequences from the variable regions V6, V7, and V8. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2593–2599. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2593-2599.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward D M, Weller R, Bateson M M. 16S rRNA sequences reveal numerous uncultured microorganisms in a natural community. Nature. 1990;345:63–65. doi: 10.1038/345063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynn-Williams D D. Cyanobacteria in deserts—life at the limit? In: Whitton B A, Potts M, editors. The ecology of cyanobacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press; 2000. pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar]