Abstract

Researchers have emphasized the detrimental effects of COVID-19 on mental health, but less attention has been given to personal strengths promoting resilience during the pandemic. One strength might be gratitude, which supports wellbeing amidst adversity. A two-wave examination of 201 college students revealed anxiety symptom severity increased to a lesser extent from pre-COVID (January–March 2020) to onset-COVID (April 2020) among those who reported greater pre-COVID gratitude. A similar trend appeared for depression symptom severity. Gratitude was also correlated with less negative changes in outlook, greater positive changes in outlook, and endorsement of positive experiences resulting from COVID-19. Thematic analysis showed “strengthened interpersonal connections” and “more time” were the most commonly reported positive experiences. Overall findings suggest gratitude lessened mental health difficulties and fostered positivity at the onset of the pandemic, but more research is needed to determine whether gratitude and other strengths promote resilience as COVID-19 continues.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Gratitude, Outlook, Resilience, Strengths

Introduction

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) a global pandemic (WHO, 2020). COVID-19 has since disrupted aspects of everyday life for people worldwide, who have endured isolation and significant social, emotional, physical, and financial costs for over two years. At the time of this writing, the global number of positive cases recently surpassed 496 million (WHO, 2022), and there is no clear end in sight to the pandemic. This unprecedented uncertainty has left many in a state of hopelessness (Twenge & Joiner, 2020).

Researchers continue to raise concerns about the detrimental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, with many individuals experiencing increased symptoms of depression and anxiety in the midst of the pandemic (Salari et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021). College students are among those whose mental health has been impacted by COVID-19, as many struggle to balance pandemic-related concerns and academic commitments (Son et al., 2020). Compared to the global estimated prevalence rates of depression (4.4%) and anxiety (3.6%) in 2015 (WHO, 2017), results from a recent meta-analysis suggest rates of depression and anxiety during the pandemic are about 33.7% and 31.9%, respectively, impacting approximately one in three people (Salari et al., 2020). These levels of depression and anxiety are of significant concern, given their association with substantially reduced quality of life and wellbeing (Jenkins et al., 2020).

In light of these alarming trends, the identification of factors that mitigate against the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health is critical. One set of factors that may serve this function is personal strengths, which consist of positive qualities that promote flourishing and contribute to the greater good (Waters et al., 2021). A strengths-based focus allows for effective responding to life’s challenges, ameliorating negative states and symptoms associated with stressful events and promoting resilience and wellbeing (Rashid & McGrath, 2020). In the current study, we propose that one strength warranting examination in the context of the pandemic is gratitude, an essential component to human flourishing (Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

Gratitude as a Strength

Gratitude has been conceptualized as an emotion, a virtue, a moral sentiment, a motive, a coping response, a skill, and an attitude, among others (Emmons & Crumpler, 2000). Minimally, gratitude is an experience of thankfulness, which involves valuing and appreciating positive experiences in daily life (Rashid & Seligman, 2018). The present study is primarily concerned with gratitude as an affective trait, also known as a “grateful disposition” or a “disposition toward gratitude.” Defined by McCullough et al. (2002), a disposition toward gratitude is considered a “generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to others’ benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (p. 112). Notably, those with a grateful disposition are less prone to habituate to positive life circumstances, which might help sustain their happiness and subjective wellbeing even in difficult situations (McCullough et al., 2002). In other words, gratitude might serve to broaden one’s experience of positive emotions and thereby build personal resources for use during a time of crisis.

Consistent with this possibility, the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions proposes that positive emotions boost adaptive thoughts and behaviors, which in turn expand personal resources contributing to wellbeing and psychological resilience (Fredrickson, 2001). These personal resources gained during states of positive emotion are durable, functioning as protective reserves in both the short- and long-term (Fredrickson, 2004). Indeed, cultivating experiences of positive emotion to cope with negative emotion might bring about an upward spiral toward improved wellbeing, fostering resilience to harmful outcomes in the face of adversity (Fredrickson, 2000, 2001). In the context of the current study, one way people might continue to live well and protect themselves against the deleterious outcomes of COVID-19 is through consistent appreciation of everyday events, or gratitude.

Aligned with the broaden-and-build theory, positive emotions associated with gratitude likely generate an upward spiral toward optimal functioning and inspire resilience. Cultivating a grateful disposition allows for a broadened scope of cognition and creative thinking as one considers a range of actions to reflect their gratitude and, in turn, these methods of repaying kindness become lasting skills that can be drawn on in times of need (Fredrickson, 2004). Through building these enduring resources, individuals experience personal growth, becoming more reflective, socially integrated, and healthy (Fredrickson, 2004). Importantly, individuals can also become more resilient. Broadened thought-action repertoires resulting from a grateful disposition likely buffer the aftereffects of negative emotions from stressful life experiences (Emmons & Mishra, 2011; Fredrickson, 2004).

Studies of gratitude prior to COVID-19 consistently support its link to wellbeing and resilience. A grateful orientation is not only associated with less negative affect, anxiety, and depression, but also more positive affect, happiness, and life satisfaction (Emmons et al., 2019; Rash et al., 2011). Further, its association with eudaimonic wellbeing, including purpose in life and self-acceptance, encourages flourishing in everyday life and a brighter outlook (Emmons & Mishra, 2011; Ryan & Deci, 2001; Wood et al., 2010). Notably, gratitude is also known to promote adaptive coping in the midst of adversity, lessening trauma-related distress and supporting personal growth (e.g., Jans-Beken, 2020; Kumar et al., 2021; Vieselmeyer et al., 2017). Because a grateful mindset promotes optimal functioning at multiple levels of analysis—biological, experiential, relational, institutional, and cultural—practicing gratitude is considered key to living a good life (Emmons & Mishra, 2011; Waters et al., 2021).

As could be expected, emerging literature also spotlights gratitude as a protective factor through the pandemic. For example, gratitude has been significantly associated with less psychological distress and negative affect, in addition to greater subjective wellbeing, positive affect and emotion, positive self-changes, work satisfaction, and thriving during COVID-19 (e.g., Bono et al., 2020; Butler & Jaffe, 2020; Casali et al., 2021; Jiang, 2020; Jiang et al., 2022; Mead et al., 2021; Nelson-Coffey et al., 2021; Syropoulos & Markowitz, 2021; Watkins et al., 2021). Further, several studies demonstrate the benefits of engaging in gratitude-related interventions during the pandemic, including lower fear of COVID-19, negative affect, and stress, as well as higher self-esteem, positive emotions, mental wellbeing, and social connectedness (e.g., Datu et al., 2021; Dennis et al., 2020, 2022; Fekete & Deichert, 2022; Geier & Morris, 2022). Respondents to self-report surveys also indicate that they expect to feel grateful in the future even in the midst of this crisis (Watkins et al., 2021), signaling the long-term impact of the positive emotions associated with gratitude.

Why Gratitude?

It could easily be argued that various strengths might contribute to the experience of positive emotions and, in turn, adaptive outcomes in the context of the pandemic. However, we focus here on the strength of gratitude for several reasons. First, the defining trait of a grateful orientation is its habitual focus on the positive aspects of daily life. In essence, gratitude is antithetical to depression and anxiety, which are commonly characterized by persistent negative thought patterns and emotions (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), and are thus fundamentally incompatible with a grateful orientation (Fredrickson, 2004). In support of this view, and complementary to the broaden-and-build theory, is the “undoing hypothesis,” which posits that positive emotions related to gratitude might “undo” the effects of negative emotions (see Fredrickson, 2004 for a discussion). Consistent with the notion of an “undoing” effect are findings showing a negative link between gratitude and depression and anxiety (e.g., Iodice et al., 2021; McCullough et al., 2002). A second reason to focus on the strength of gratitude is its association with constructs related to wellbeing above the effects of other commonly examined strengths (e.g., altruism, creativity, judgment, appreciation of beauty and excellence; Niemiec, 2013; Wood et al., 2008). In other words, gratitude demonstrates a unique contribution to adaptive outcomes even in the presence of other strengths. Third, although gratitude is relatively stable across time, evidence suggests it is malleable (Park & Peterson, 2009). Indeed, gratitude can be developed in ways to enhance life satisfaction, positive affect, and a favorable outlook (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Emmons et al., 2019; Froh et al., 2008; Rash et al., 2011; Seligman et al., 2005). In light of these findings, it is possible that gratitude might serve as a buffer against symptoms of depression and anxiety and a predictor of positive changes resulting from the pandemic. If true, integrating gratitude-promoting activities into interventions for those struggling to cope with the negative effects of the COVID-19 outbreak might be warranted.

The Present Study

We aimed to extend recent work and contribute to the growing literature on the protective nature of gratitude in several ways. First, although gratitude has been examined as a correlate of general psychological distress during the pandemic, it appears that no work has examined its potential buffering effect on depression and anxiety over time at the onset of COVID-19. The closest examination of these constructs was in a cross-sectional study conducted by Casali et al. (2021), who found those with transcendence strengths (e.g., hope, zest, gratitude) reported lower symptoms of depression and anxiety during the pandemic, although these symptoms were represented in a total score despite being distinct dimensions of clinical psychopathology (APA, 2013). Here, we aimed to address this gap and test whether gratitude served as a pre-pandemic buffer for each of these symptom presentations over time. Next, although researchers have considered other resilience factors during the pandemic (see Waters et al., 2021 for a review), to our knowledge no studies have explored gratitude’s association with changes in outlook at the onset of COVID-19, and only one study has explored gratitude’s association with reported positive changes in self resulting from the pandemic (i.e., Watkins et al., 2021). However, this study did not utilize an open-ended response format such that participants could provide personalized insights into their lived experiences at the onset of COVID-19, which are critical to informing future research and clinical efforts.

To fill these gaps and better understand the experiences of individuals during this unique and challenging time, we examined gratitude’s association with both positive and negative changes in outlook at the onset of COVID-19 and also explored closed- and open-ended responses related to reported positive changes in any aspect of life that resulted from the pandemic. This approach is advantageous in that it will allow us to combine the generalizable, externally valid data gathered through the quantitative portion of our study with participants’ rich, contextualized insights on their lived experiences gathered from the qualitative portion of our study. Further, the strengths of one type of data tend to mitigate the weaknesses of the other, allowing for a more robust set of findings (see Regnault et al., 2018 for a discussion). Notably, we also explored these possibilities among college students, a group of individuals who have experienced unique struggles at the onset of COVID-19 (e.g., virtual learning, moving off campus; Aristovnik et al., 2020) and report high rates of depression and anxiety as a result of the pandemic (Wang et al., 2021). With these efforts, we aim to lend further empirical support to the claim that gratitude is an important contributor to resilience and wellbeing, even during a global pandemic.

Drawing on theory and prior research, we hypothesized that a greater disposition toward gratitude prior the pandemic would buffer against increases in depression (H1) and anxiety (H2) symptoms pre- to onset-COVID. We also predicted higher levels of pre-COVID gratitude would be associated with less negative changes in outlook (H3), greater positive changes in outlook (H4), and increased endorsement of positive experiences resulting from the pandemic (H5). No specific themes were hypothesized prior to identifying codable units in open-ended responses related to positive changes resulting from the COVID-19 crisis.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Undergraduate students were recruited through the departmental psychology subject pool for a larger online longitudinal study about “life experiences” (e.g., see Jaffe et al., 2021 and Kumar et al., 2021 for related studies using these data). To participate, individuals were required to be at least 19 years of age (the local age of majority). Given the focus of the present study on changes in mental health and outlook at the onset of the pandemic, data collected during the spring 2020 semester were examined. At the first assessment, participants provided informed consent and then completed a series of self-report questionnaires through Qualtrics. All participants were provided with information about counseling services on campus and received research credit for their participation. Students were also given the opportunity to participate in follow-up assessments of the larger study for additional research credit.

Following the declaration of the pandemic on March 11, 2020, the university system implemented restrictions on March 16, 2020, including cancellation of in-person classes and issuance of safety guidance for students. Although there were no official stay-at-home orders within the state of data collection, guidelines were implemented to restrict public gatherings. To capture experiences during this time, participants who completed the first assessment of the larger study during spring 2020 prior to the last week of the semester were invited to complete a follow-up survey between April 24 and 29, 2020. No additional research credit was awarded.

Given this study’s focus on time-related trends, responses from both the first assessment of the semester (i.e., the pre-COVID survey, completed between January 13 and March 15, 2020 prior to the implementation of local restrictions; n = 201) and the follow-up assessment (i.e., the onset-COVID survey, completed at the beginning of the pandemic from April 24 to 29, 2020; n = 73) were used in analyses. At baseline, these 201 participants ranged in age from 19 to 45 years (M = 20.27, SD = 2.68) and 132 (65.7%) identified as women, 65 (32.3%) as men, and four (2.0%) as gender minorities (e.g., gender queer, transgender women, transgender men). Participants identified as White (90.0%; n = 181), Asian (8.5%; n = 17), Black or African American (3.5%; n = 7), American Indian or Alaska Native (1.0%; n = 2), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (0.5%; n = 1), and “other” (1.5%; n = 3; percentages exceed 100% because more than one race could be selected). Approximately 6.5% (n = 13) of participants identified as Latino/a, Hispanic, or of Spanish origin. As an approximation of socioeconomic status, participants indicated their average yearly income if they supported themselves, or their parents’ average yearly income if their parents supported them. The modal average yearly income (including parental income if receiving parental support) was over $70,000 (45.5%; n = 91), but there was variability with almost half of the sample (43.0%; n = 86) earning at or below $50,000 per year.

Measures

Gratitude

During the first assessment, prior to when the pandemic was declared, participants completed the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6; McCullough et al., 2002) to assess their appreciation of positive experiences in daily life. The GQ-6 is a six-item self-report measure in which each item is rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include, “I have so much in life to be thankful for,” and “I am grateful to a wide variety of people.” A total sum score was created (possible range: 6 to 42), with higher scores representing greater levels of gratitude. Past work has supported the validity of this measure (e.g., McCullough et al., 2002). Cronbach’s alpha for the GQ-6 in the current sample suggested internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.80).

Depression and Anxiety

The Brief-Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2001) is an 18-item self-report measure that assesses current psychological distress on three dimensions: somatization, depression, and anxiety. Participants rate each item on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). For the purpose of the current study, we examined items from the depression (e.g., “feeling blue”) and anxiety (e.g., “feeling fearful”) subscales pre- and onset-COVID, with the exception of the suicidal ideation item, which was not administered during the onset-COVID study due to lack of risk mitigation procedures in place. We calculated a total sum score for the depression and anxiety subscales, with higher scores representing greater mental health difficulties. The possible range of scores for the depression subscale was 0 to 20 (5 items), while the anxiety subscale was 0 to 24 (6 items). Past work has supported the validity of this measure (e.g., Franke et al., 2017). Cronbach’s alphas for the depression (pre-COVID α = 0.88; onset-COVID α = 0.90) and anxiety (pre-COVID α = 0.88; onset-COVID α = 0.90) subscales of the BSI-18 in the current sample were acceptable.

Changes in Outlook at the Onset of COVID-19

To examine changes in outlook at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants completed the short form of the Changes in Outlook Questionnaire (CiOQ; Joseph et al., 2006). This 10-item self-report measure assesses positive and negative changes in one’s outlook in the context of a specific event. Participants were cued to think about their experiences with COVID-19 before rating five positively-valenced and five negatively-valenced items on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Sample items include, “I’m a more understanding and tolerant person now,” and “I don’t look forward to the future anymore.” Sum scores for positive and negative changes in outlook were calculated, with higher scores indicating greater amounts of valenced change in outlook. Past work has supported the validity of this measure (e.g., Joseph et al., 2006). Cronbach’s alphas for the positive (α = 0.83) and negative (α = 0.76) outlook subscales in the current sample suggested internal consistency was acceptable.

Positive Experiences Resulting from COVID-19

To evaluate positive experiences resulting from COVID-19, participants were asked, “Has the COVID-19 crisis led to any positive changes in your life?” (options: yes, no, maybe). Participants who responded with “yes” or “maybe” were asked to describe the positive changes in their lives that have resulted from the COVID-19 crisis in an open-ended text box.

Data Analytic Plan

Quantitative Analyses

We first examined relevant descriptives to characterize our sample. Then, to understand patterns of missingness, we assessed group differences among demographic characteristics and primary study variables with regard to those who completed the onset-COVID survey (n = 73) versus those who did not (n = 128). We found completion of the onset-COVID survey was not associated (all ps > 0.05) with pre-COVID gratitude, age, income, gender (first analysis dichotomized such that 0 = gender majority group [man, woman], 1 = gender minority group; second analysis dichotomized such that 0 = man, 1 = woman), or race/ethnicity (dichotomized such that 0 = majority group [White], 1 = minority group [American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Latino/a, Hispanic, or Spanish origin, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, other]). As such, none of these variables were included as covariates in the proposed analyses. These steps were conducted in SPSS v.24.

Next, we conducted two separate multilevel models in R version 3.6.3 (primary packages used were glmmTMB (Brooks et al., 2017) and interactions (Long, 2019)) to evaluate whether gratitude moderated depression (H1) and anxiety (H2) symptoms from pre- to onset-COVID. Specifically, the following multilevel model was tested for both depression and anxiety symptoms:

Repeated measures of depression and anxiety symptoms were nested within participants, and all cases were included in analyses regardless of missing onset-COVID data using maximum likelihood estimation. Time (Level 1) was modeled as a dummy variable (0 = pre-COVID survey, 1 = onset-COVID survey). Pre-COVID gratitude (Level 2) was grand-mean centered to create a meaningful zero value at which the main effect of time could be interpreted (uncentered observed scores ranged from 17 to 42). To test our primary hypotheses, a cross-level interaction between time and pre-COVID gratitude was modeled (i.e., β11). We then probed the interaction term at the lowest, average (± 1 SD), and highest levels of gratitude observed in our dataset to illustrate the full possible range of scores in our moderation analyses.

Next, to assess whether higher pre-COVID gratitude was associated with less negative changes in outlook (H3) and greater positive changes in outlook (H4) at the onset of COVID-19, we examined Pearson’s r correlations. Then, to determine if levels of pre-COVID gratitude were higher among participants who responded “yes” to the onset-COVID question, “Has the COVID-19 crisis led to any positive changes in your life?” relative to those who responded “no” and “maybe” (H5), we conducted a one-way between groups analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Power

Sample size was determined from the number of individuals who had completed an ongoing study at the time the COVID-19 pandemic was declared; thus, a priori power analyses could not be conducted. However, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses in G*Power (Erdfelder et al., 1996) to determine the smallest effects we were powered to detect in our quantitative analyses. Regarding our multilevel model analyses, sample size at the highest level of the hierarchy (in this case, Level 2) is the key consideration for a multilevel model design (Snijders, 2005), and a sample size of at least 50 is considered ideal for obtaining unbiased estimates (Maas & Hox, 2005). With a sample size of 201 in the current study, we had sufficient power to accurately detect an effect size r as small as 0.20 (power = 0.80; alpha = 0.05; two-tailed) for a regression path with three predictors (i.e., time, gratitude, and time X gratitude as predictors of mental health symptoms). Regarding our correlation analyses, we had sufficient power to accurately detect an effect size r as small as 0.20 (power = 0.80; alpha = 0.05; two-tailed). Finally, regarding our one-way ANOVA analysis, we had sufficient power to accurately detect an effect size r as small as 0.22 (power = 0.80; alpha = 0.05) with three groups.

Qualitative Analyses

Finally, to examine the nature of positive changes reported, the first three authors examined text entry responses (n = 57) in reply to the question, “Please describe the positive changes in your life that have resulted from the COVID-19 crisis” and conducted a thematic analysis on those data. Authors followed procedures recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006). Specifically, this process began through a review of the participant response dataset and initial ideas were recorded. After generating initial codable units of information across the dataset, the authors worked together to search for discrete themes that could be defined by a shared description or rule. The authors met on three separate occasions to review, define, and refine themes, solidify coding rules, assign codes to responses, and select examples that represented each theme. Discrepancies in coding were resolved through discussion until all three authors were in agreement. Where applicable, participant responses were coded into multiple categories, but each participant could only receive a specific code once.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

At the pre-COVID-19 assessment, participants reported moderately high levels of gratitude (M = 35.61, SD = 5.04; observed range: 17–42) and low symptoms of depression (M = 4.86, SD = 4.47; observed range: 0–20) and anxiety (M = 4.52, SD = 4.90; observed range: 0–23). At the onset of COVID-19, participants reported low but relatively higher symptoms of depression (M = 6.34, SD = 5.25; observed range: 0–20) and anxiety (M = 4.64, SD = 5.30; observed range: 0–20). Participants also endorsed fairly high positive changes in outlook (M = 23.10, SD = 3.92; observed range: 12–30) and moderate negative changes in outlook (M = 11.49, SD = 4.33; observed range: 5–23) as a result of the pandemic. Of the 71 participants who answered whether the COVID-19 crisis led to any positive changes in their lives, 43 (60.56%) reported “yes,” 14 (19.72%) reported “maybe,” and 14 (19.72%) reported “no.” Thus, a total of 57 participants indicated they may have experienced positive life changes resulting from the pandemic. All variables were within acceptable limits of skew ( <|3|) and kurtosis ( <|10|; Kline, 2015).

Gratitude, Depression, and Anxiety

First, we examined whether changes in symptoms of depression (H1) and anxiety (H2) from pre- to onset-COVID varied by pre-COVID levels of gratitude. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) indicated 44.9% of the variance in depression and 33.2% of the variance in anxiety was attributable to between-person differences, suggesting that some individuals experienced more or less depression or anxiety than others during the pandemic. These values support the use of multilevel modeling and are consistent with ICC estimates of depression and anxiety in the literature (e.g., George et al., 2018). Pseudo R-squared values reflected that the symptom models explained 48.4% of the variance in depression and 36.1% in anxiety.

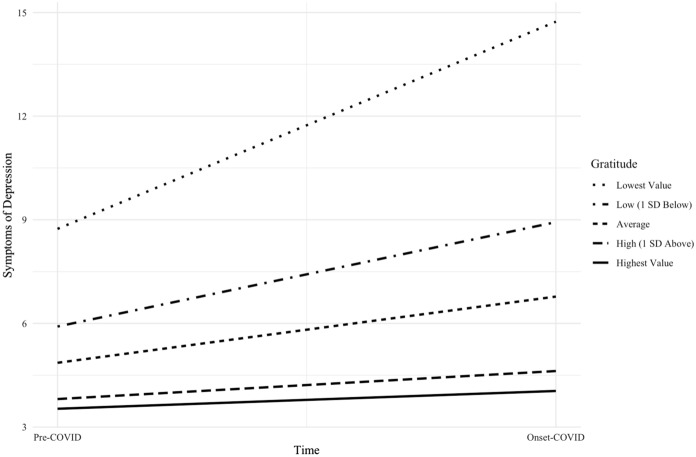

Regarding the depression model, depression symptom severity significantly increased from pre- to onset-COVID, B = 1.70, SE = 0.52, p = 0.001, although there was a trending pattern for the interaction term between time and gratitude on depression, B = − 0.20, SE = 0.12, p = 0.082. Simple slopes analyses indicated that, for individuals with the highest levels of gratitude (42.00, 1.27 SD above the mean), depression symptom severity did not significantly increase from pre- to onset-COVID (B = 0.51, SE = 1.00, p = 0.61). This pattern was also consistent for individuals with gratitude levels 1 SD above the mean (40.65; B = 0.81, SE = 0.86, p = 0.35). In contrast, depression symptom severity significantly increased for individuals with average levels of gratitude (35.61; B = 1.92, SE = 0.63, p < 0.01), gratitude levels 1 SD below the mean (30.57; B = 3.02, SE = 1.02, p < 0.01), and the lowest levels of gratitude (17.00, 3.69 SD below the mean; B = 6.00, SE = 2.77, p = 0.03). Taken together, to the extent that individuals were higher in gratitude, depression symptoms pre- to onset-COVID were attenuated (see Fig. 1 for an illustration of these effects).

Fig. 1.

Depression symptom severity pre- to onset-COVID at conditional levels of gratitude. Note. Conditional effects of gratitude are modeled at the lowest (17.00), 1 SD below the mean (30.57), average (35.61), 1 SD above the mean (40.65), and highest (42.00) observed scores in the dataset. The test statistic of each conditional estimate for gratitude is as follows: lowest (B = 6.00, SE = 2.77, p = 0.03), 1 SD below the mean (B = 3.02, SE = 1.02, p < 0.01), average (B = 1.92, SE = 0.63, p < 0.01), 1 SD above the mean (B = 0.81, SE = 0.86, p = 0.35), and highest (B = 0.51, SE = 1.00, p = 0.61)

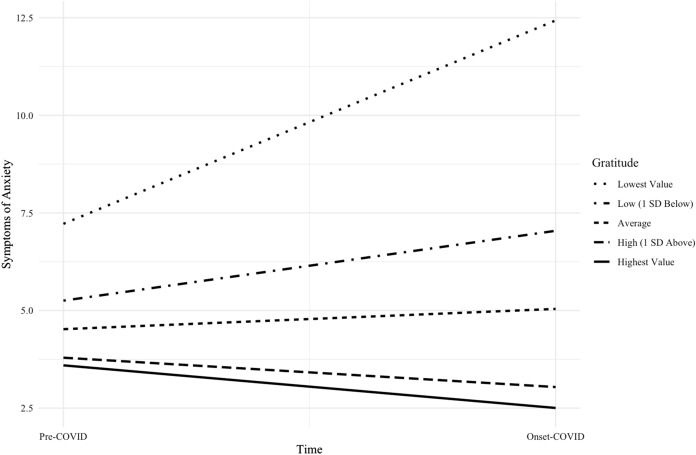

Regarding the anxiety model, reports of anxiety did not significantly increase from pre- to onset-COVID, B = 0.32, SE = 0.61, p = 0.599, but the interaction term between time and gratitude on anxiety was significant, B = − 0.27, SE = 0.13, p = 0.048. Simple slopes analyses indicated that, for individuals with the highest levels of gratitude (42.00, 1.27 SD above the mean), anxiety symptom severity did not significantly increase pre- to onset-COVID (B = − 1.09, SE = 1.08, p = 0.31). A similar pattern was found for individuals with gratitude levels 1 SD above the mean (40.65; B = − 0.75, SE = 0.93, p = 0.42), average levels of gratitude (35.61; B = 0.52, SE = 0.69, p = 0.45), and gratitude levels 1 SD below the mean (30.57; B = 1.79, SE = 1.11, p = 0.11). In contrast, there was a trending pattern for anxiety symptom severity among individuals with the lowest levels of gratitude (17.00, 3.69 SD below the mean; B = 5.21, SE = 3.01, p = 0.09). Taken together, to the extent that individuals were higher in gratitude, anxiety symptoms pre- to onset-COVID were attenuated (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Anxiety symptom severity pre- to onset-COVID at conditional levels of gratitude. Note. Conditional effects of gratitude are modeled at the lowest (17.00), 1 SD below the mean (30.57), average (35.61), 1 SD above the mean (40.65), and highest (42.00) observed scores in the dataset. The test statistic of each conditional estimate for gratitude is as follows: lowest (B = 5.21, SE = 3.01, p = 0.09), 1 SD below the mean (B = 1.79, SE = 1.11, p = 0.11), average (B = 0.52, SE = 0.69, p = 0.45), 1 SD above the mean (B = − 0.75, SE = 0.93, p = 0.42), and highest (B = − 1.09, SE = 1.08, p = 0.31)

Gratitude and Changes in Outlook

Next, we examined whether pre-COVID gratitude was associated with less negative changes in outlook (H3) and greater positive changes in outlook (H4) at the onset of COVID-19. Correlations revealed higher levels of pre-COVID gratitude were associated with less negative changes in outlook (r = − 0.47, p < 0.001) and greater positive changes in outlook (r = 0.42, p < 0.001) as a result of the pandemic.

Gratitude and Endorsement of Positive Experiences

Quantitative Analyses

To test our final hypothesis, we examined whether higher levels of pre-COVID gratitude were linked to greater reports of “yes” in response to the question, “Has the COVID-19 crisis led to any positive changes in your life?” (H5). A one-way between subjects ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the three response groups, F(268) = 5.63, p = 0.005. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test indicated mean gratitude scores for the “yes” response group (M = 37.86, SD = 3.45) were significantly higher than the “no” response group (M = 33.79, SD = 5.37), p = 0.005. The “maybe” response group (M = 35.79, SD = 4.51) did not significantly differ from the “yes” (p = 0.23) and “no” (p = 0.40) response groups.

Qualitative Analyses

Among the 57 participants who indicated they may have experienced positive life changes resulting from the pandemic, 56 responded to the open-ended question describing those changes. The thematic analysis of these responses yielded 11 discrete themes, as detailed in Table 1 and outlined below.

Table 1.

Student-Reported Positive Changes Resulting from the COVID-19 Pandemic

| Theme | Example | n (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Strengthened interpersonal connections | “I have spent a lot more time with my immediate family. We actually have gotten along better while being home for a month, rather than arguing more. I have a stronger and closer relationship with my brother and sister as well.” | 28 (50.00%) |

| 2. More time | “I am able to create my own daily schedule and have had more time to myself to be able to work productively towards my goals.” | 25 (44.64%) |

| 3. Academic ease or improvement | “All summer classes are being offered online (ones that were not offered before) and it gives me the chance to get caught up in college classes I’ve had set backs in.” | 18 (32.14%) |

| 4. Engagement in activities | “I've taken up several new projects, such as starting a blog and learning a language.” | 13 (23.21%) |

| 5. Mental health | “I’ve been able to focus on my mental health…” | 7 (12.50%) |

| 6. Relaxation or sleep | “I have had more time to relax.” | 7 (12.50%) |

| 7. Physical health | “I am working out more and being more careful about nutrition.” | 6 (10.71%) |

| 8. Self-reflection or appreciation | “I now have a deeper appreciation for life. I realized I took a lot of small things for granted and now I strive to be always grateful and appreciative of everything I have.” | 6 (10.71%) |

| 9. Stronger faith | “More dedicated to my faith…” | 3 (5.36%) |

| 10. Environmental positivity | “…cleaner air and community environment from less human interaction…” | 2 (3.57%) |

| 11. Monetary benefit | “Both of my parents are able to work more so our income has actually increased, making the financial situation much easier.” | 2 (3.57%) |

| N = 56b |

aWhere applicable, responses were coded into multiple categories, but each participant could only receive a code once

bAlthough 57 participants viewed the open-ended prompt, one participant was excluded due to missing data

Theme 1: Strengthened Interpersonal Connections

Half of the sample (n = 28) endorsed improved connections with others (e.g., friends, immediate family, significant others) as a result of the pandemic. Participants often mentioned they prioritized building strong relationships with those who were important to them upon returning home. This was noted through more frequent communication, increased time spent together, and closer bonds to the people in their life.

Theme 2: More Time

The second most common theme that arose from participants’ responses highlighted the importance of time (n = 25). Participants mentioned that having more time and/or a lack of commitments was a positive change in their life. Many explicitly stated that “more time” and increased availability in their schedule were key positive outcomes, and this additional time provided them with more control over their schedule and flexibility to complete tasks.

Theme 3: Academic Ease or Improvement

This third theme highlighted that, for some participants, completing their academic coursework became easier or school demands were more flexible (n = 18). Students expressed they were better able to focus on their schoolwork with less outside distractions. Many highlighted how changes in their courses were related to improvement in academic outcomes, such as positive changes in grades and accessibility (e.g., additional courses offered online). Some also noted situations in which class-related requirements appeared to become less time consuming and stressful.

Theme 4: Engagement in Activities

This theme included coded responses in which participants mentioned engaging in valued activities and/or hobbies (n = 13). Some highlighted completing more activities that they enjoyed, while others noted they were able to accomplish tasks around their house. Participants consistently noted they had begun new hobbies or were completing new or unfinished projects. Examples of activities participants listed included starting a blog, learning a language, working on crafts, and reading for enjoyment. Some participants also highlighted how these were activities they had not been able to make time for in the past but were able to do so now.

Theme 5: Mental Health

Within this theme, participants reported increases in emotional wellbeing and/or decreases in mental health difficulties (n = 7). One participant explicitly mentioned being able to focus on their mental health as a positive outcome. Others focused on decreases in difficulties, such as feeling less stress and anxiety. Two participants reported greater overall wellbeing. One participant mentioned an increase in motivation, while another focused on increased happiness from walking their dog more often.

Theme 6: Relaxation or Sleep

Another theme that emerged was relaxation or sleep (n = 7), in which participants mentioned increases in leisure and/or improvements in sleep. Participants commonly noted they were spending their time resting, relaxing, and “chilling.” Others focused on sleep quantity and quality.

Theme 7: Physical Health

This theme is represented by improvements specific to physical health needs (n = 6). The majority of responses in this category highlighted behaviors conducive to physical health, such as increased exercise. Participants also mentioned positive changes in nutrition habits, such as eating “healthier food” and “drinking less.” One participant mentioned a broader goal of “trying to live a healthier lifestyle.”

Theme 8: Self-Reflection or Appreciation

This theme was comprised of responses that included self-reflective behaviors or a greater appreciation in life as a result of COVID-19 (n = 6). These participants indicated they took “a step back” and used the pandemic as an opportunity to reflect on their lives. Some indicated planning for the future and/or focusing on improvements they could make in their lives. Others went beyond reflection to spotlight strengthened appreciation and gratitude for their life and those in it.

Theme 9: Stronger Faith

Several responses among participants mentioned a shared theme in which they reported a stronger relation with their faith and/or a religious figure (n = 3). These participants highlighted increased dedication and time spent in their faith. One participant noted focusing on their relationship with their religious leader.

Theme 10: Environmental Positivity

Additional responses related to positive environmental changes were included in this theme (n = 2). Participants highlighted how safety precautions that required individuals to stay home appeared to limit pollution and increase environmental cleanliness.

Theme 11: Monetary Benefit

This final theme reflected responses by participants who reported an increase in financial income due to the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 2). One participant mentioned receiving a raise at their job. The other noted their parents were able to work additional hours, which eased their family’s financial situation.

Discussion

The current study filled a void in the gratitude literature by investigating its potential benefits over time during a pandemic. Specifically, we found higher levels of gratitude prior to the pandemic were associated with less severe symptoms of anxiety pre- to onset-COVID, and a similar trend appeared for symptoms of depression. In addition, symptom increases in depression and anxiety pre- to onset-COVID were attenuated at observable and above average levels of gratitude. Finally, gratitude was associated with less negative changes in outlook, greater positive changes in outlook, and endorsement of positive experiences resulting from the COVID-19 crisis. When participants were asked about these positive experiences, strengthened interpersonal connections, more time, and academic ease or improvement were the three most commonly reported outcomes. Each of these findings is discussed below.

The benefits of gratitude have been well-documented by researchers. Practicing gratitude offers distinct advantages, including the ability to extract optimal benefits from positive experiences, bolster self-worth and self-esteem, cope well with stress, help others effectively, strengthen interpersonal relationships, make fewer negative comparisons to others, spend less time dwelling on negative emotions, and experience prolonged happiness from new situations (Carr et al., 2020; Emmons & Mishra, 2011; Rashid & Seligman, 2018). A recent study of personal strengths among college students also revealed gratitude was linked to greater overall satisfaction with life (Bachik et al., 2021). Through cultivating these experiences of positive emotion, gratitude broadens and builds psychological resources, which can then act as buffers in difficult circumstances (Fredrickson, 2001, 2004; Rashid & Seligman, 2018). Indeed, gratitude is known to promote wellbeing in the midst of adversity in both community and college samples (e.g., Jans-Beken, 2020; Kumar et al., 2021; Vieselmeyer et al., 2017), including in the context of COVID-19 (e.g., Bono et al., 2020; Butler & Jaffe, 2020; Casali et al., 2021; Jiang, 2020; Jiang et al., 2022; Mead et al., 2021; Nelson-Coffey et al., 2021; Syropoulos & Markowitz, 2021; Watkins et al., 2021). Results from the current study align with the broaden-and-build theory and are consistent with the above work. Further, findings add to the growing literature by highlighting that gratitude, even during the substantial stressor of a pandemic, can (1) buffer mental health difficulties over time, (2) promote positive changes in outlook, and (3) build resources such that individuals can continue experiencing positive changes in self.

We also extend prior research by employing a qualitative analysis of college student survey responses related to positive experiences at the onset of the pandemic. Most participants who completed the onset-COVID survey indicated that the COVID-19 crisis led to positive changes in their lives (60.56%) and also tended to report higher levels of gratitude prior to the pandemic than those who perceived no positive changes related to the pandemic. Among those who identified any positive changes, the nature of those changes aligned with the positive outcomes that gratitude has been shown to inspire; for example, strengthened interpersonal connections, academic ease or improvement, engagement in activities, mental health, relaxation or sleep, physical health, self-reflection, and stronger faith are all valuable outcomes associated with a more grateful mindset (Algoe, 2012; Boggiss, et al., 2020; Emmons & Mishra, 2011; Flinchbaugh et al., 2012; Jackowska et al., 2015; Rashid & Seligman, 2018). Notably, students also reported increased appreciation and gratitude for their life and those in it. This suggests that gratitude might breed gratitude, an interesting idea supported by Fredrickson and Joiner’s (2002) finding that positive emotions broadened thinking and in turn fostered future increases in positive emotions. In the current study, experiences of gratitude prior to the pandemic might have triggered positive emotions at the onset of the outbreak, and these positive emotions in turn might have increased the likelihood of experiencing more gratitude as the pandemic continued. There were also several themes that appeared specific to COVID-19, including more time, environmental positivity, and monetary benefit. These reports emphasize both broader and unique ways that college students were able to flourish despite uncontrollable circumstances, and thus might be relevant for consideration in future research and clinical work related to gratitude, resilience, and wellbeing among this group.

Bringing our quantitative and qualitative results together further underscores the benefits of a grateful mindset during a period of prolonged stress such as the COVID-19 crisis. In the current study, a stronger grateful orientation not only attenuated symptoms of depression and anxiety but also sparked greater endorsement of positive experiences resulting from the pandemic. Based on these findings, it is possible that, in our sample, a grateful mindset inspired a more complete model of mental health, which affirms that mental health is not only the absence of mental illness but also the presence of a positive state of functioning (Keyes, 2007). Indeed, those with a grateful mindset reported less mental health concerns in combination with views such as, “I now have a deeper appreciation for life. I realized I took a lot of small things for granted and now I strive to be always grateful and appreciative of everything I have.” These findings also lend further evidence to the belief that positive emotions related to gratitude are incompatible with negative emotions and “undo” their effects, thus encouraging an upward spiral toward wellbeing (Fredrickson, 2004).

Limitations and Future Directions

Although the current study contributes to a growing knowledge of gratitude as a resiliency factor during a pandemic, there are limitations worth noting. First, these results were gathered as part of a larger study examining life experiences among undergraduate students. Accordingly, all participants were enrolled in college, most of whom identified as White women and were of higher socioeconomic status. Although examination of this sample is important through its contribution to our knowledge about unique ways in which the pandemic affected college students, the generalizability of findings across settings to other universities, or to adults more broadly, including those who identify as racial, ethnic, and gender minorities, is unclear. To continue examining the unique impacts of the pandemic on college students and to allow for a broader generalization of findings, future researchers should consider recruiting from other universities and community settings, with a priority toward increasing diversity. Larger more diverse samples would also allow for more nuanced analyses examining the prevalence, nature, and implications of gratitude across different cultures during the pandemic.

Relatedly, to minimize participant burden at the onset of the pandemic, we limited the number of questions in the follow-up survey and chose not to conduct follow-up interviews. Although this might have increased completion rates, a drawback to this approach is that we did not obtain substantial detail regarding participants’ positive life changes resulting from the pandemic. Rather, we only collected brief text responses to a single prompt. In order to expand upon our findings and better understand how gratitude might relate to meaningful outcomes during the pandemic, future researchers should consider using more comprehensive methodology, such as interviews, to better explore this area.

Next, although the longitudinal design in a study that was ongoing at the onset of the pandemic is a strength, changes in depression and anxiety symptoms were examined across only two time points, and perceived changes in outlook were assessed at only one time point. Though these efforts provide initial support for the positive impacts of gratitude at the onset of COVID-19, and the accompanying qualitative analysis helps supplement these findings, future researchers should include additional time points in studies of gratitude, mental health, and outlook during the pandemic to assess possible longitudinal effects. Further, we encourage researchers who were collecting data on clinical symptoms and positive psychology constructs when the pandemic began to replicate and extend our pre- to post-onset pandemic findings in order to strengthen the validity of claims made here. Another avenue for future longitudinal research is to explore whether gratitude must be established prior to community-wide stressors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic, military deployment, natural disasters) to be most beneficial or if there might be equal value in promoting gratitude after the stressors have occurred. It is possible that gratitude might be best established prior to the presence of stressors, but it may also be the case that building gratitude concurrently, even in the face of adversity, promotes resilience and wellbeing. Collectively, this additional work will permit for strengthened examinations of gratitude as a valuable resource during times of crisis.

In addition to examining the influence of gratitude on mental health and outlook as the pandemic lingers, we encourage researchers to examine personal strengths not measured here, which may also promote resilience to the negative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic both in the short- and long-term. Based on recent research conducted during the pandemic (e.g., Jaffe et al., 2022; Mead et al., 2021; Waters et al., 2021), candidates might include optimism, meaning in life, and self-compassion. As related to our qualitative findings in the current study, for example, several participants indicated positive expectancies for the future, which correspond to notions of optimism (Scheier et al., 1994). Similarly, a handful of participants reported they had begun reflecting on their life and engaging in activities that encourage self-growth as a result of the pandemic. It is possible that this meaning-making process might foster a stronger sense of purpose and wellbeing in light of the COVID-19 crisis (Park, 2010). Finally, many participants expressed values that align well with aspects of self-compassion, such as being kind to oneself (Neff, 2003). Uncovering different ways individuals draw on their personal strengths to promote optimal functioning and flourishing during times of crisis will help us better understand factors that contribute to resilience and inform the development of strengths-based interventions for COVID-19 and related concerns.

Clinical Implications and Conclusion

The current study has important implications for the incorporation of positive psychology practices into clinical work and everyday living. Given that pre-existing gratitude was associated with reduced psychological distress and fostered positivity during the pandemic, there might be benefits not only to encouraging the practice of gratitude during this time of crisis but also beyond the pandemic. In particular, for college students seeking mental health services on campus, clinicians might consider providing psychoeducation on gratitude and related practices, such as gratitude journaling (Rashid & Seligman, 2018). Free evidence-based resources on gratitude also exist and could help promote healthy coping skills for students and others experiencing barriers to mental healthcare and build resiliency in anticipation of future hardship (e.g., the “Three Good Things” activity; Greater Good Science Center, 2021; Seligman et al., 2005). These are low-cost, high-reward practices that might ultimately lead to reduced mental distress, a more sanguine outlook, and positive experiences as seen here.

In sum, gratitude, which prompts healthy reframing of negative experiences as positive, helps individuals evaluate what is most important in everyday living and encourages adaptive coping in times of stress (Rashid & Seligman, 2018). Current findings suggest that a grateful mindset also serves as a point of resilience during a pandemic, potentially aiding in navigation of the unique challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis. Developing a grateful orientation is likely to encourage personal growth and remain a positive resource for individuals even beyond the pandemic through raising awareness of the goodness in one’s everyday life.

Funding

Manuscript preparation was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (F31HD101271; PI: Kumar, Sponsor: DiLillo) and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K08AA028546, PI: Jaffe). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures (IRB#: 20160115842EP), which adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Algoe SB. Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6:455–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12:8438. doi: 10.3390/su12208438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachik MAK, Carey G, Craighead WE. VIA character strengths among U.S. college students and their associations with happiness, well-being, resiliency, academic success and psychopathology. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021;16:512–525. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1752785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boggiss AL, Consedine NS, Brenton-Peters JM, Hofman PL, Serlachius AS. A systematic review of gratitude interventions: Effects on physical health and health behaviors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2020;135:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono G, Reil K, Hescox J. Stress and wellbeing in urban college students in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic: Can grit and gratitude help? International Journal of Wellbeing. 2020;10:39–57. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v10i3.1331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks ME, Kristensen K, van Benthem KJ, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, Skaug HJ, Mächler M, Bolker BM. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal. 2017;9:378–400. doi: 10.32614/RJ-2017-066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. & Jaffe, S. (2020). Challenges and gratitude: A diary study of software engineers working from home during COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/challenges-and-gratitude-a-diary-study-of-software-engineers-working-from-home-during-covid-19-pandemic/.

- Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, Canning C, Mooney O, Chinseallaigh E, O'Dowd A. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casali N, Feraco T, Ghisi M, Meneghetti C. “Andrà tutto bene”: Associations between character strengths, psychological distress and self-efficacy during COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2021;22:2255–2274. doi: 10.1007/s10902-020-00321-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greater Good Science Center. (2021). Three good things. https://ggia.berkeley.edu/practice/three-good-things.

- Datu JAD, Valdez JPM, McInerney DM, Cayubit RF. The effects of gratitude and kindness on life satisfaction, positive emotions, negative emotions, and COVID-19 anxiety: An online pilot experimental study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2021 doi: 10.1111/aphw.12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A, Ogden J. Nostalgia, gratitude, or optimism: The impact of a two-week intervention on well-being during COVID-19. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10902-022-00513-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis A, Ogden J, Hepper EG. Evaluating the impact of a time orientation intervention on well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: Past, present or future? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1858335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L. R. (2001). Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) 18: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. NCS Pearson.

- Emmons RA, Crumpler CA. Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:56–69. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A., Froh, J., & Rose, R. (2019). Gratitude. In M. W. Gallagher & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures (pp. 317–332). American Psychological Association.

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:377–389. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A., & Mishra, A. (2011). Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. In K. Sheldon, T. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing the future of positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 248–262). Oxford Press.

- Erdfelder E, Faul F, Buchner A. GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers. 1996;28:1–11. doi: 10.3758/BF03203630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Deichert NT. A brief gratitude writing intervention decreased stress and negative affect during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10902-022-00505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinchbaugh CL, Moore EWG, Chang YK, May DR. Student well-being interventions: The effects of stress management techniques and gratitude journaling in the management education classroom. Journal of Management Education. 2012;36:191–219. doi: 10.1177/1052562911430062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franke GH, Jaeger S, Glaesmer H, Barkmann C, Petrowski K, Braehler E. Psychometric analysis of the brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) in a representative German sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2017;17:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12874-016-0283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention and Treatment. 2000 doi: 10.1037/1522-3736.3.1.31a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden- and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). Oxford Press.

- Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science. 2002;13:172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Sefick WJ, Emmons RA. Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geier MT, Morris J. The impact of a gratitude intervention on mental well-being during COVID-19: A quasi-experimental study of university students. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2022 doi: 10.1111/aphw.12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, Russell MA, Piontak JR, Odgers CL. Concurrent and subsequent associations between daily digital technology use and high-risk adolescents’ mental health symptoms. Child Development. 2018;89:78–88. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iodice JA, Malouff JM, Schutte NS. The association between gratitude and depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Depression and Anxiety. 2021;4:1–12. doi: 10.23937/2643-4059/1710024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackowska M, Brown J, Ronaldson A, Steptoe A. The impact of a brief gratitude intervention on subjective well-being, biology and sleep. Journal of Health Psychology. 2015;21:2207–2217. doi: 10.1177/1359105315572455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A. E., Kumar, S. A., Ramirez, J. J., & DiLillo, D. (2021). Is the COVID-19 pandemic a high-risk period for college student alcohol use? A comparison of three spring semesters. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 45, 854–863. 10.1111/acer.14572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jaffe AE, Kumar SA, Hultgren BA, Smith-LeCavalier KN, Garcia TA, Canning JR, Larimer ME. Meaning in life and stress-related drinking: A multicohort study of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addictive Behaviors. 2022;129:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jans-Beken L, Jacobs N, Janssens M, Peeters S, Reijnders J, Lechner L, Lataster J. Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020;15:743–782. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1651888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins PE, Ducker I, Gooding R, James M, Rutter-Eley E. Anxiety and depression in a sample of UK college students: A study of prevalence, comorbidity, and quality of life. Journal of American College Health. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1709474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: A daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journals of Gerontology. 2020;77:36–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Chiu MM, Liu S. Daily positive support and perceived stress during COVID-19 outbreak: The role of daily gratitude within couples. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022;23:65–79. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00387-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Linley PA, Shevlin M, Goodfellow B, Butler LD. Assessing positive and negative changes in the aftermath of adversity: A short form of the changes in outlook questionnaire. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2006;11:85–99. doi: 10.1080/15325020500358241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist. 2007;62:95–108. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 4. Guilford: Guilford publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SA, Jaffe AE, Brock RL, DiLillo D. Resilience to suicidal ideation among college sexual assault survivors: The protective role of optimism and gratitude in the context of posttraumatic stress. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2021;14(S1):S91–S100. doi: 10.1037/tra0001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, J. A. (2019). Interactions: Comprehensive, user-friendly toolkit for probing interactions.https://cran.r-project.org/package=interactions.

- Maas CJ, Hox J. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. 2005;1:86–92. doi: 10.1027/1614-1881.1.3.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang J. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:112–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead JP, Fisher Z, Tree JJ, Wong P, Kemp AH. Protectors of wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Key roles for gratitude and tragic optimism in a UK-based cohort. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:647951. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff KD. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity. 2003;2:85–101. doi: 10.1080/15298860309032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson-Coffey SK, O'Brien MM, Braunstein BM, Mickelson KD, Ha T. Health behavior adherence and emotional adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic in a US nationally representative sample: The roles of prosocial motivation and gratitude. Social Science and Medicine. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: Research and practice the first 10 years. In: Knoop HH, Delle Fave A, editors. Cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology: Perspectives from positive psychology. Dordrecht: Springer; 2013. pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136:257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N, Peterson C. Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College and Character. 2009;10:1–10. doi: 10.2202/1940-1639.1042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Seligman M. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford: Oxford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rash JA, Matsuba MK, Prkachin KM. Gratitude and well-being: Who benefits the most from a gratitude intervention? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being. 2011;3:350–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2011.01058.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid T, McGrath RE. Strengths-based actions to enhance wellbeing in the time of COVID- 19. International Journal of Wellbeing. 2020;10:113–132. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v10i4.1441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid T, Seligman M. Positive psychotherapy: Clinician manual. Oxford: Oxford Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Regnault A, Willgoss T, Barbic S, International Society for Quality of Life Research Mixed Methods Special Interest Group Towards the use of mixed methods inquiry as best practice in health outcomes research. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2017;2:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s41687-018-0043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudemonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:141–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Rasoulpoor S, Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Globalization and Health. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60:410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders TAB. Power and sample size in multilevel modeling. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. 2005;3:1570–1573. doi: 10.1002/0470013192.bsa492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students' mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2020;22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syropoulos S, Markowitz EM. Prosocial responses to COVID-19: Examining the role of gratitude, fairness and legacy motives. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Joiner TE. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2020;76:2170–2182. doi: 10.1002/jclp.23064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieselmeyer J, Holguin J, Mezulis A. The role of resilience and gratitude in posttraumatic stress and growth following a campus shooting. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2017;9:62–69. doi: 10.1037/tra0000149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Wen W, Zhang H, Ni J, Jiang J, Cheng Y, Zhou M, Ye L, Feng Z, Ge Z, Luo H, Wang M, Zhang X, Liu W. Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of American College Health. 2021 doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters L, Algoe SB, Dutton J, Emmons R, Fredrickson BL, Heaphy E, Moskowitz JT, Neff K, Niemiec R, Pury C, Steger M. Positive psychology in a pandemic: Buffering, bolstering, and building mental health. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1871945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, P. C., Emmons, R. A., Amador, T., & Fredrick, M. (2021). Growth of gratitude in times of trouble: Gratitude in the pandemic [Conference session]. In: International positive psychology association 7th world congress.

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AWA. Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Maltby J. Gratitude uniquely predicts satisfaction with life: Incremental validity above the domains and facets of the five factor model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;45:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/254610.

- World Health Organization. (2020). Listings of WHO’s response to COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 12 April 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---12-april-2022.