Abstract

Despite a massive investment in subsidized housing, informal settlement remains a significant aspect of urban development in Chilean cities. This paper first surveys the urban morphology of contemporary settlements in four Chilean cities to maps the extent and location of neighbourhoods that have developed informally or semi-formally. The broad pattern is that the more informal of settlements have been practically eliminated from the capital of Santiago, yet mixed informality flourishes and is expanding on the peripheries of regional cities. Four cases are then mapped and analysed to show the morphogenesis—the ways buildings and street networks are incrementally designed and produced. A range of morphogenic patterns are identified including highly irregular morphologies on escarpment conditions, semi-regular street grids, and informal encrustations within formal housing projects. It is argued that informal production will remain significant and that a better understanding of informal settlement morphology is crucial to the design and planning for the future of Chilean cities.

Keywords: Urban informality, Informal settlements, Morphogenesis, Urban morphology, Chile

Introduction

Informal settlement has long been the primary mode of production of public space and affordable housing in cities of the global south. While there is widespread research around the social, economic, and planning policies that underpin this mode of production (Alfaro d’Alençon et al. 2018; Mac Donald 2011; Roy and Alsayyad 2004; UN Habitat 2016) little has been investigated about the morphological processes that shape it. Through multi-scalar mapping, this paper investigates the morphologies and morphogenic processes of informal settlement in four Chilean cities. At a metropolitan level, the objective is to map the extent of different types of informal morphology that are evident in each city. What spatial patterns are evident in informal settlements location and growth? How can we better understand the spatial relations between the formal and the informal city? At a neighbourhood scale, the goal is to understand the emergence of informal architecture and urban design and the factors that shape these outcomes. What building types and increments of construction define the architecture? What patterns of informal street network emerge, how do they relate to the formal grid and what forms of public space are produced? Finally, what are the commonalities and differences of informal urban morphology across diverse geographies and locations within major Chilean cities? The overall aim is to understand the underlying spatial logics of informal settlement as a basis for better managing, upgrading, and anticipating future expansion.

Informal urbanism

While definitions of urban informality and the usefulness of the concept remain contested, it broadly refers to the set of self-organized practices that produce architecture, urban design, and planning beyond the control of the state. Often regarded as marginal and inferior, urban informality is the primary manner in which rural-to-urban migrants gain access to jobs, livelihoods and affordable housing that the market or the state cannot supply. Many Global South cities absorb much of their growing population through informal settlements, which house at least a billion people globally (UN Habitat 2016).

Any understanding of urban informality must go beyond any binary distinction of the formal and informal, as they are always imbricated or intertwined in a twofold condition (Dovey, 2016, p. 218). It should be understood as a mode of urbanization that operates through a series of transactions and relationships with the state (Roy 2005). Fully informalized settlements are much less common than mixed or ‘between’ conditions of informal settlements becoming formalised and formal settlements becoming informalized (Dovey and Kamalipour, 2018). Rather than a singular process, the development of informal settlements depends on a series of relations between topographies, infrastructure, climate, culture, economics, and politics (Dovey and King, 2011).

Informal housing is a complex phenomenon that is based on incremental decisions and adaptations. From the 1970s, Turner (1972) argued for an understanding of housing as a verb, a means of empowerment and autonomy for the urban poor. Incremental urbanism describes the process of emergence of an informal architecture and urban design through a multiplicity of decisions and micro-adaptations that are not controlled hierarchically. While escalating intensification can lead to slum conditions, informal practices can produce innovative, highly adaptable, and culturally sensitive housing solutions (Lizarralde 2015). Informal settlements are complex adaptive systems that are interconnected at multiple scales from the laneway to the metropolis (Dovey, 2012). While informal settlement is widely seen as a product of global neoliberal capitalism enabling new modes of exploitation of cheap labour (Davis 2006), it is also a means of livelihood for the urban poor and can be a transition out of poverty as settlements are incrementally upgraded. Settlements occur on both public and private land, often involving pirate developers and land mafias with a broad range of tenure conditions (Payne 2001). There is no scope to pursue these differences and contentious issues here, only to note that informal settlement practices cannot be reduced to singular causes or conditions, and that most settlements become permanent over time.

Urban morphology

The discipline of urban morphology seeks to understand the shaping of urban form, mostly stemming from the work of Conzen (1960), Muratori (1960) and others (Moudon 1997). Urban morphologists generally identify buildings, plots, streets and blocks as the basic elements or types that define urban form together with the interrelations between them (Marshall 2005; Moudon 2019)—buildings are generally contained within plots, and plots within blocks, which are defined by streets. Examination of those basic elements enables comparisons between different morphologies and the tracing of morphogenic change within a settlement over time (Scheer 2015). Alexander was among the first to propose a morphogenic theory of urban design (Alexander et al. 1987) an approach that has been developed by Salingaros (2000) and Mehaffy (2008). Kostof (1999) included the 'organic' development of cities as a key mode of urban design, with informal settlement as one example. Marshall (2009) has pursued an evolutionary approach to urban morphology and makes a distinction between ‘systematic’ urban order that flows top-down and a ‘characteristic’ order that is emergent. While the formal city usually develops from an urban design plan with streets, blocks and plots established before buildings are added, informal settlement is often a spontaneous accretion of rooms and buildings which co-evolve with plots, streets and blocks and the settlement morphology emerges incrementally. A better understanding of this form of urban design is central to this study.

While the expansion of informal settlement has been studied at metropolitan scale (Angel et al. 2011) urban design studies are rarer. There is a growing literature on the mapping of informal settlements through technologies of remote sensing and GIS (Baud et al. 2010; Taubenböck and Kraff 2014; Kuffer et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2020); most of this work is a means of identifying 'slum' conditions rather than informal morphogenesis. Hillier and others have used spatial syntax analysis to explore urban connectivity, occasionally applied to informal settlements (Hillier et al. 2000; Serra et al. 2016). Hakim’s (2014) work on traditional vernacular urbanism demonstrates how informal codes emerge to both create and to protect the commons including rights of way, open space, daylight, views, privacy and so on. However, studies of contemporary informal morphogenesis are rare.

Informal settlement in Chile

Informal settlements in Chile are generally called campamentos (encampments) a term that dates from the land invasions of the 1970s and denotes a fragile and paramilitary character. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning defines a campamento as a settlement of eight or more families living with irregular land tenure, lacking basic services (MINVU 2018). A good deal has been written about their impact on the expansion of the city and influence on housing policies during the second half of the twentieth century (Arellano 2005; De Ramón 1990; Hidalgo 2004; Kusnetzoff 1987). There is little scope to cover this history here, however, it is important to note that since the return to democracy in the 1990s Chile has been the site of massive public investment in housing that has led to a reduction of informal settlements, particularly in the capital of Santiago. Much of this investment has focused on subsidies that enable the urban poor to move from campamentos to the ownership of new low-quality housing, often located in low-income ghettos on the urban fringe (Salcedo 2010; Gilbert 2002).

There are many critiques of such policies and their effects, but it is clear that they have not eradicated either housing inequalities or the expansion of informal settlements (Contreras et al. 2019; López-Morales et al. 2018). This work has also challenged the assumption of informal settlements as enclaves of poverty and exclusion. The campamentos are often seen as an alternative to social housing programs with better access to jobs, less crime (Brain Valenzuela et al. 2010; Celhay and Gil 2020) and a stronger sense of community (Salcedo 2010).

There is much less research on the urban morphology that informality produces. Studies in Valparaiso document the progressive consolidation of informal settlements and strategies to access basic services (Ojeda et al. 2020; Pino and Ojeda 2013). Others have focused on the informalisation of social housing neighbourhoods as residents extend the minimal housing provided formally. While such additions and encroachments can be seen as a failure of housing programs (Jirón 2010), incremental informal accretions on formal housing are a widely prevalent form of housing production (O’Brien and Carrasco 2021) that has also been adopted as a strategy for reducing costs in new housing (Aravena et al. 2004). There is considerable experience in incremental housing policies in Chile, particularly around the Vivienda Progresiva approach conceived after the return of the democracy during the 90’s (Greene and González 2014; Ducci et al. 1944).

The massive investment in housing in Chile since 1990 has been an internationally recognized success story that is propagated globally as 'best practice' (Gilbert 2002). This approach has led to a consistent reduction of informal settlements since the 1980’s through the provision of segregated housing complex and neighbourhoods, mainly located in the urban periphery. However, data from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning also shows that while the number of campamentos have declined in Santiago, they have increased in most other Chilean cities since 2011 (MINVU 2018).

Methods

The focus of this paper is on mapping informal settlement patterns in four Chilean cities at both metropolitan and neighbourhood scales based on data available through Google Earth, complemented with Street View (when available) and web searches for each case study. While all data are digital and our methods are complemented with GIS, we have chosen to map by hand because the human eye remains more accurate at urban design scales than remote sensing algorithms (e.g., Taubenböck et al. 2018), and because mapping by hand is a learning process that reveals morphological patterns. The metropolitan mapping is based on a non-binary model to understand different degrees and kinds of formal/informal-mix of both street/block layouts and building footprints (Dovey and Kamalipour, 2018). The key criteria for analysis of aerial photographs are the irregularity and incrementality (grain size) of the urban morphology. There are no socio-economic criteria—this is not a mapping of 'slums' but of the forms of informality. Metropolitan areas (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4) are mapped in four categories: the 'formal' city (light peach), a 'formal mix' (dark peach), informal-mix (orange) and informal (red). This is not a simple continuum. The 'formal mix' is mostly comprised of informally encrusted formal housing while the 'informal mix' is largely semi-organized or semi-formalized campamentos. The four cities have been mapped in order to capture the different patterns of location, extension and typology of informality at a metropolitan scale.

Fig. 1.

Informal Settlements in Santiago [Aerial Photos: Google Earth]

Fig. 2.

Informal Settlements in Greater Valparaiso [Aerial Photos: Google Earth]

Fig. 3.

Informal Settlements in Antofagasta [Aerial Photos: Google Earth]

Fig. 4.

Informal Settlements in Greater Iquique [Aerial Photos: Google Earth]

Micro- and meso-scale studies of informal settlements are also necessary to comprehend the dynamics of small adaptations and incremental change. Here the method is based on a recent global comparative study of informal morphogenesis in five settlements (Dovey et al, 2020); the aim is to understand the morphogenic processes of representative cases in each Chilean city. Buildings footprints, plots and access networks are mapped from high resolution aerial photographs of 4 different dates. While planning processes and documents are relevant components of the research, they are beyond the scope of this paper. Cases are first mapped within a 25 ha (500 × 500 m) frame in order to understand how street networks evolve, how land is appropriated and what patterns of incremental construction can be found. For a micro-scale analysis, a framework of 4 ha (200 × 200 m) or 1 ha (100 × 100 m) is employed. This data are then analysed at multiple scales, to shed light on the different processes and forces that shape the morphology.

Metropolitan scale

This study focuses on four major urban areas of Chile: Santiago, Greater Valparaiso, Antofagasta, and Greater Iquique. These metropolitan areas drive important economic activities for the country and concentrate most of the population of their regions.

Santiago

Santiago is the political and economic centre of the country, holding near 7 million people. It was founded as a Spanish colony in 1541 in the fertile Mapocho River valley. The city developed through industrialization during the nineteenth century and rural-to-urban migration fuelled an explosive expansion through the twentieth century. By the 1970s, campamento dwellers represented 17% of the population, occupying 10% of the urban area (De Ramón 1990). During the dictatorship (1973–1990) massive evictions were conducted with residents relocated to the urban periphery, forced to live in isolated areas with little infrastructure or public investment (Kusnetzoff 1987). Figure 1 maps the current spatial distribution of informal settlement in Santiago together with examples of typical morphologies. It reveals how informality is clearly constrained to the west and south of the city with some pockets to the north (Fig. 1). The areas of informality are overwhelmingly what we have termed 'formal mix'—primarily informal additions to new housing. These patches largely match the areas where social housing was delivered during the 1980’s and 1990’s (Morales and Rojas 1986; Hidalgo 1999). The state has since been successful in controlling land invasions—the informal production of housing has not abated but has re-emerged as encrustation on social housing.

This form of housing with public subsidies was designed to leverage poorer households into home ownership rather than public rental. The houses are small and low-quality but at densities low enough to enable room-by-room accretions. Common typologies are row or slab housing of 2–4 storeys with incremental accretions on the back and front, often including shops and workshops in what is otherwise a monofunctional neighbourhood. The map shows very few highly informal settlements (red); the large red patch to the east is a recent land invasion (July 2020) produced by the economic crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic. The few patches of informal-mix (orange) are also recent and show an emerging pattern of pirate subdivision of farmland on the periphery.

Greater Valparaiso

Famous for its street art and cultural heritage, Valparaiso was a major harbour for international trade during the nineteenth century, now expanded into an urban agglomeration with about a million people incorporating Viña del Mar to the northeast. The narrow coastal plain with a fringe of steep hills creates an amphitheatre-like setting where informal settlement has long invaded the vacant land of ravines and escarpments (Pino and Ojeda 2013). Viña del Mar is a flatter topography but has also expanded into the hills since the 80s, driven by both formal and informal urbanization (Arellano 2005). Figure 2 shows informal settlement along the fringes of both cities and comprising a considerable portion of the urban expansion. The 'formal mix' (dark peach) corresponds mostly to informal expansion that has been incrementally formalised while preserving the morphology of irregular street alignments. Some of these areas in the southwest represent informal additions to formal housing (as in Santiago). The escarpments and ravines of Valparaiso generate a pattern of increasing informality as one moves to higher land further from the coast. Most informal settlements in Valparaiso are located in a forest zone, at risk of landslides and bushfires, without access to water and highly segregated from the city (Ojeda et al. 2020). Viña del Mar to the northeast presents a more distributed pattern of informality, with larger patches of both formal-mix and informal-mix, again becoming more informal on the escarpments. The largest patch of formal-mix just southeast of the city centre has grown along with the expansion of a main road since 2011. On the northeast fringe is a large area of informal-mix that has expanded rapidly since 2019.

Antofagasta

About 1100 km north of Santiago is the port city of Antofagasta with a population of about 400,000. Once part of Bolivia, the city grew as a centre for saltpetre mining and export in the nineteenth century and was incorporated into Chile after the War of the Pacific in 1884. In recent decades a growing economy has attracted international migration, mostly from Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru. With the city contained by a narrow coastal plain, land scarcity has led to a dramatic increase in rent and expansion of informal settlements (Vergara-Perucich and Arias-Loyola 2019). Figure 3 shows a coastal strip that is highly formal—mostly gated communities and high-rise housing compounds—with clear increases of informal expansion as it mounts the coastal range. Large patches of formal-mix are located northeast of the city, where social housing has been informalized through incremental accretion. The informal-mix close to the city centre is an irregular street morphology that has become formalised over time. The more informal settlements are located on escarpments, often with a serious risk of landslide.

Greater Iquique

Greater Iquique in the far north of Chile is a conurbation of about 300,000 population incorporating Iquique and the city of Alto Hospicio. Like Antofagasta, the port of Iquique developed based on saltpetre exports in the nineteenth century and is also part of the territory gained from Peru in 1883; its architectural heritage now attracts a growing tourist industry. Alto Hospicio has developed since the 1980s on a plateau 10 km away and 800 m higher; based on copper mining and related industries it is the fastest growing city of Chile. Most of the growth has been absorbed by subsidized housing, but informal settlement has become an alternate form of affordable housing (Imilán et al. 2020). Figure 4 show that a formal-mix (informalized social housing) is widespread in both cities, yet the locations are quite different. In Iquique this informal morphology is well inland from the central city while in Alto Hospicio it surrounds the city centre; this is due to the key role of subsidised housing in founding the city and absorbing the explosive population growth. The more informalized settlements in Iquique are linear escarpments, repeating the pattern found in Antofagasta. Substantial areas of informal-mix (orange) are also found in more marginal locations in Alto Hospicio; these are recent encroachments with a quasi-formal layout of streets and lots.

Metropolitan patterns

This form of mapping based on visual analysis of aerial photographs has some obvious limits; most pertinent is that the distinctions we have made between these four morphologies are blurred—the most 'formal' of developments will often have informal accretions and the most informal of settlements are generally becoming formalized. This typology is nothing more than a lens that has been applied in order to better understand the informal/formal patterns and differences in these Chilean cities. A first point is that the overwhelming bulk of informal settlement is mixed—highly informalized settlement (red) is rare in comparison to the mixed areas (orange or darker peach). Second, these areas of mixed and informal settlement are largely located on the urban periphery and become increasingly informal with distance. The category of 'formal-mix' occupies a substantial area across each city and has largely been produced by state social housing policies. Settlements we have termed 'informal-mix' and 'informal' often emerge close to neighbourhoods of 'formal-mix'. This may be due to the location of social housing on underutilized land, and where the gaze of state control is weaker than near middle and upper-middle class neighbourhoods. The most obvious difference between these cities is that informal settlement in Santiago is overwhelmingly a formal-mix in social housing areas. State power is highly concentrated in the capital and more resources have been deployed to eradicate informality. The largest informal settlements in Chile are recent and rapidly growing in regional cities—an emerging trend that requires further exploration and research.

Neighbourhood scale

We now zoom in to examine one informalized neighbourhood within each city. Here we analyse the morphogenetic processes that have shaped the urban design and architecture over time. Sites are selected to cover some of the more typical morphological patterns that have emerged in the metropolitan studies. The goal here is to provide greater insight into the emergence of mixed morphologies: the 'formal-mix' and 'informal-mix'—broadly understood as a distinction between a formal urban design framework that is becoming incrementally informalized through architectural production on the one hand, and an informal or semi-formal urban design that is becoming incrementally formalized.

San Gabriel

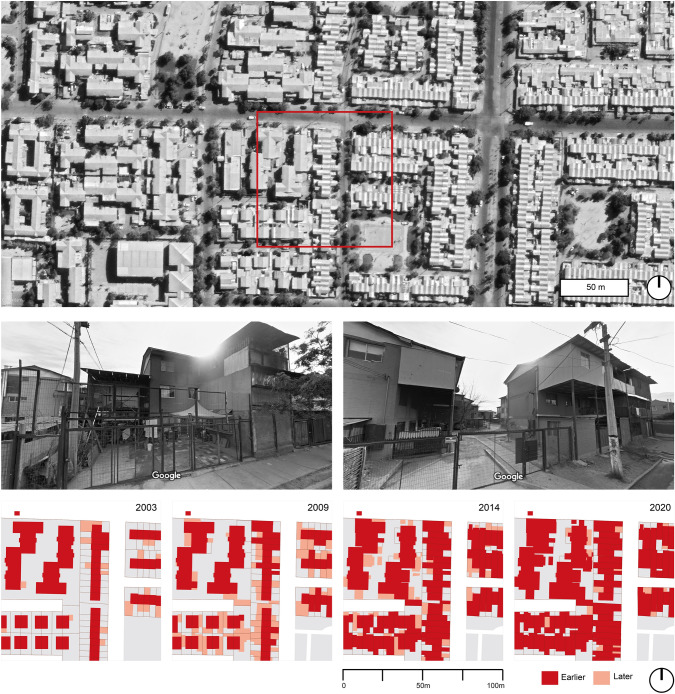

Villa San Gabriel (Google Maps ref: 33° 33′ 47.75″ S 70° 37′ 26.38″ W) is a neighbourhood in the south of Santiago (Fig. 1), developed in the 1980s after the majority of the initial residents were evicted from informal settlements (Morales and Rojas 1986). The district has a high concentration of poverty, lack of employment, and social housing comprises more than 90% of the dwellings. This is a typical case of social housing that has been informalized through an incremental process of additions and encroachments. The formal street network frames blocks of 90 × 120 m with substantial open space in the form of squares, green corridors, and soccer fields.

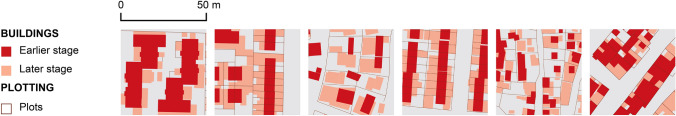

Figure 5 shows an aerial photo of a 15 ha area showing the formal street layout, building types and substantial informal additions. There are three different housing types: three storey slab apartments with shared common space; two storey semi-detached houses with substantial front and back yards; and row-houses with similar private open space. The 1 hectare detail maps show part of this district at 4 stages of informalization from 2003 to 2020. The earliest data reveals the extent of original buildings with some initial changes and the later maps show further additions. In general, the semi-detached and row-houses have accrued the most substantial additions to front, rear and side yards. Front yards are variously adapted as garage and storage in addition to domestic functions, and on main streets they sometimes incorporate shops. The semi-detached plots of 6 × 13 m have become encroached faster than the smaller 4.5 × 18 m plots of the row-houses, however, by the final stage of the study period plot coverage is nearly 90% for both types. There has been negligible encroachment beyond the plot boundary. The 3 storey slab apartment buildings have also been extended through the addition of rooms or semi-enclosed balconies at multiple levels with lightweight construction supported on columns. At ground floor level these additions can also extend into common space while maintaining car access. Here the plots are at a larger scale so the boundary between private and public space is unclear. Although this area was planned as a monofunctional neighbourhood, the informal additions to some houses on the main roads incorporate shops and workshops.

Fig. 5.

Morphogenesis of Villa San Gabriel. [Photos: Google Earth (top); Street View (middle)]

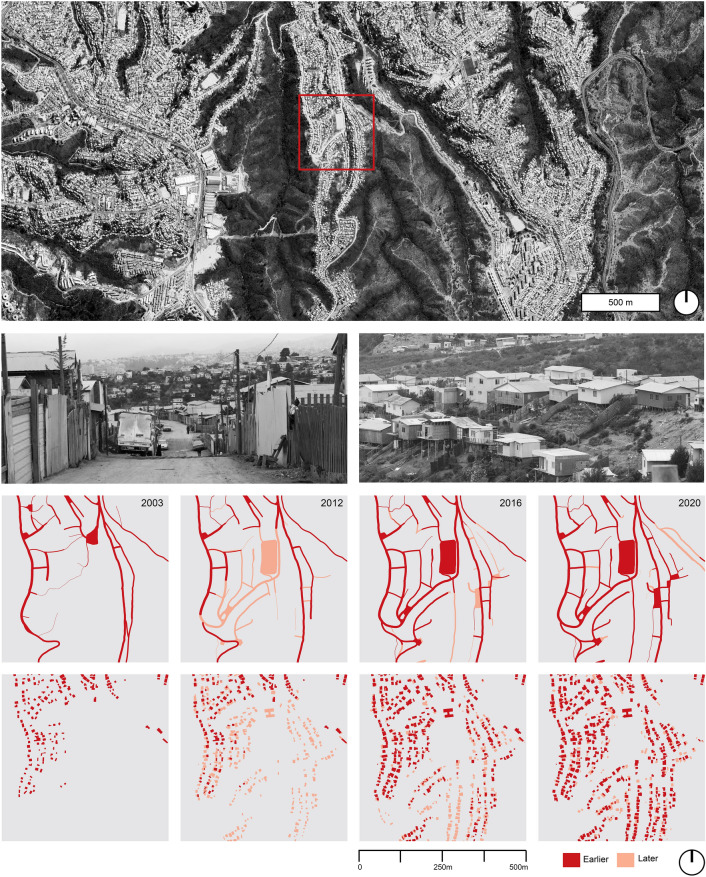

Felipe Camiroaga

Felipe Camiroaga is a campamento about 4 km from Viña del Mar city centre, housing about 900 households on mostly privately owned land on the ridges of an escarpment (33° 03′ 01.25″ S 71° 32′ 52.19″ W). An older informal settlement to the north of the site was established since 1990 (Techo Chile 2018). The morphogenic maps (Fig. 6) show the new settlement extending southwards from 2012 through two main paths along ridge lines. Settlement begins in a linear pattern along existing tracks with plots marked later. During the early stages we also see the establishment of a broad public space and day care centre between the two ridges. As the settlement expands new roads are constructed that open up new territory. While vehicular roads either follow contour lines or climb diagonally across the slopes, smaller pedestrian lanes are also designed to connect up and down steeper slopes for permeability. Plots of about 20 m deep and 10 m wide are marked after the initial construction is established. The building typology is mainly 1–2 storey detached dwellings at low density and in lightweight construction. Steeper sites generally require some excavation and many buildings project over the slope, supported on columns. Houses are constructed one or two rooms at a time and often reach footprints of about 100 sqm—far in excess of what is possible in subsidized housing. The linear pattern of settlement is strongly influenced by the topography and existing roads; the street network reveals a lack of east–west permeability due to steepness. Flatter parts of the settlement show evidence of more organized urban design with plots and open spaces marked prior to construction. The neighbourhood is serviced by local buses and is a 15-min drive from the central city. New road connections to Valparaiso are under way and this is clearly a permanent addition to the region; the community is in negotiations with the owners of the private land over long-term tenure. The community appears well-organized with well-maintained public spaces and community buildings; a few houses have been adapted to shopfronts over time.

Fig. 6.

Morphogenesis of Felipe Camiroaga [Photos: Google Earth (top); Agencia uno (middle left); www.revistaviernes.cl (middle right)]

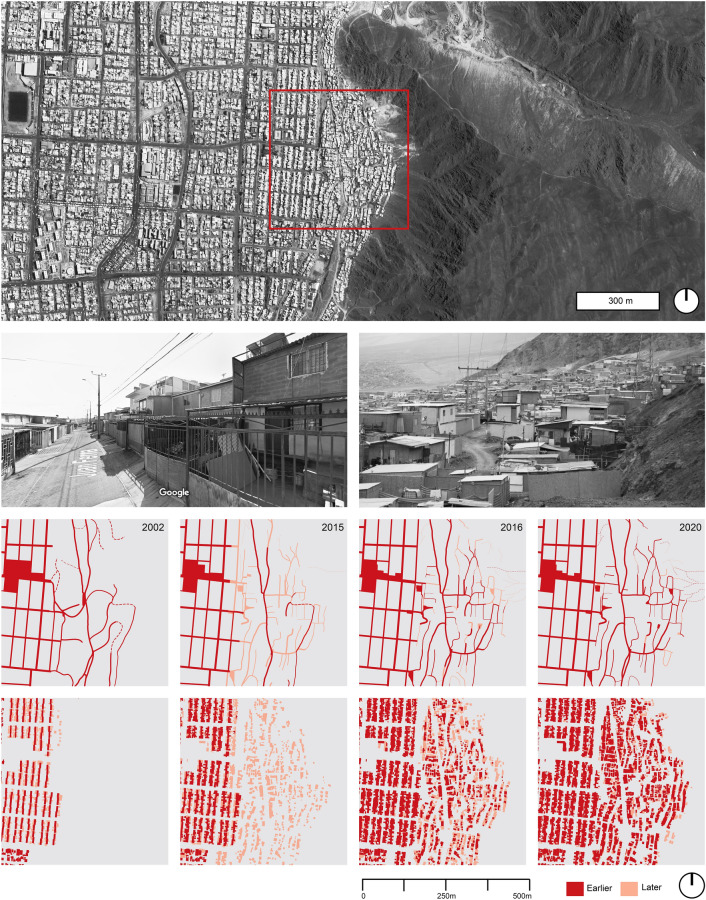

Balmaceda

Villa Balmaceda (23° 35′ 59.03″ S 70° 22′ 16.00″ W) is a social housing neighbourhood about 6 km from the centre of Antofagasta at the base of an escarpment (Fig. 7). The original housing types are two storey row-houses of 60 sqm on 15 × 5 m plots. As in Villa San Gabriel there have been substantial informal additions to both back and front yards. Average plot coverage was about 66% in the earlier period but rose incrementally and 10 years later most lots have reached 100% coverage. Street view data shows mixed construction of reinforced brick and light materials. A few cases in each block have added a third floor. Google Maps indicates that at least 8 houses in this area have been adapted as shops or workshops, increasing the functional mix of the neighbourhood. Beginning in 2015 the adjacent escarpment was invaded and settled by about 1000 households. The urban design was based on an existing network of tracks that were adapted and upgraded to roads of 6–8 m wide with lateral roads of about 3–4 m wide. The main road climbs diagonally up the escarpment before switching back to reach the highest point. These roads are intersected by laterals to form large blocks of about 150–300 m long, with a few narrower and steeper pedestrian paths providing greater permeability. Detached houses are located along the tracks and aligned with contours, often beginning with one or two rooms with later additions. Construction is generally timber and light steel frame with a maximum of two storeys. Plots of about 5 m wide and 15–20 m deep—almost identical to those used in the adjacent social housing—become evident after construction. Plot coverage ranges from 70 to 100%. This settlement is exposed to landslides, sits under electricity transmission lines, and is under threat of eviction.

Fig. 7.

Morphogenesis of Balmaceda [Photos: Google Earth (top); Street View (middle left); www.plataformaurbana.cl (middle right)]

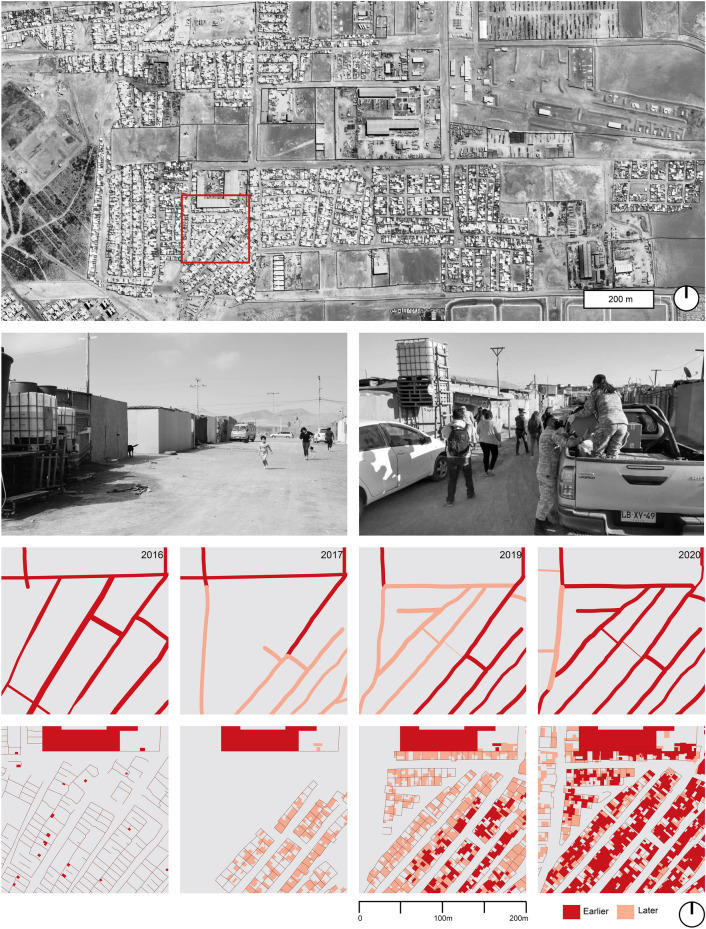

El Boro

El Boro is a 60 ha agglomeration of semi-formal settlements that have progressively claimed an extensive area of flat land located between social housing neighbourhoods and industrial zones in Alto Hospicio in Greater Iquique (20° 15′ 24.04″ S 70° 05′ 41.93″ W). Aerial photos show remnant evidence of a highly informal settlement on this land prior to 2004 when this was unoccupied ground beyond the bounds of the new city. The land was progressively invaded by semi-organized groups from early 2016 (Fig. 8). In contrast to the escarpments, here plots of 8 × 16 m are clearly marked out prior to construction. The urban design was aligned with pre-existing pathways and comprised roads of 5–10 m wide framing blocks of 100–300 m long and about 30 m (2 plots) wide. The 4 ha detail shows that this area was initially plotted but largely unoccupied before it was demolished in April 2016, leaving the adjacent settled areas intact. Within a month one part of this area had been re-plotted, settled and then grew incrementally through 2016–2017. The new subdivision followed the alignment of the earlier plan, but all streets and plots were re-designed. The new urban design was incremental and less regular than the initial design—some blocks are only one plot wide and one of the wider streets has been incrementally converted to a cul-de-sac, diverting traffic into smaller streets. Roads remain about 5–10 m wide with multiple connections to the formal street network. In 2020 the invasion of vacant land continues, and plot coverage is very high, reaching 90 to 100% in many cases. Buildings are mostly made of light materials and single storey. This settlement remains relatively separated from the formal city and there is no evidence functional mix.

Fig. 8.

Morphogenesis of El Boro [Photos: Google Earth (top); www.indh.cl (middle left); www.diariolongino.cl (middle right)]

Morphogenesis

This is a comparative study of informal settlement across four Chilean cities at multiple scales from streetscape to metropolis. It is not our goal to reduce these settlement practices to their causes, but to draw out the urban design patterns and differences that are evident in the outcomes. The aim is to explore the set of relations that are established between the topography, the occupation process, and the existing infrastructure; we also seek to unpack the implied rules and logics that generate particular arrangements of streets, lots and buildings in each case. This is neither an evaluation of the urban design quality of these settlements nor a prescription for policy or design. Any approach to urban transformation will need to be done in the knowledge of how such settlements are produced and will continue to be produced. What is primarily at stake here is the livelihoods and living conditions of the residents.

The four sites we have mapped in detail show a range of six morphologies which are compared in Table 1. The distinctions between them can be understood in terms of topography, pre-existing infrastructure, plotting, street networks, coverage, height, and speed. The most obvious division is between what we have mapped at metropolitan scale as formal-mix and informal-mix—between the informalized social housing of the villas and the more informal campamentos. The language of campamentos (encampments) suggests the fragile and temporary in contrast to villas (villages) that suggest the stable and permanent. Yet this analysis enables us to also see distinctions within these categories.

Table 1.

| San Gabriel apartments | San Gabriel rows | Felipe Camiroaga | Balmaceda lower | Balmaceda upper | EL BORO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topography | Flatland | Flatland | Escarpment | Sloping | Escarpment | Flatland |

| Land tenure | Collective ownership | Private ownership | Squatting on private and public land | Private ownership | Squatting on public land | Squatting on public land |

| Pre-existing buildings | 3 Storey apartments | 2 Storey row and semi-detached | None | 2 Storey row-housing | None | None |

| Pre-existing streets | Formal grid | Formal grid | Tracks | Formal grid | Tracks | Tracks |

| Plotting | No plots | Formal | Incremental | Formal | Incremental | Semi-formal |

| Street network | Formal grid | Formal grid | Informal | Formal grid | Informal | Semi-formal grid |

| Net coverage | High | High | Medium | High | High | High |

| Height | 3 Storey | 2 Storey | 1–2 Storey | 2–3 Storey | 1–2 Storey | 1–2 Storey |

| Speed | Slow | Slow | Fast | Slow | Fast | Fast |

Within the campamentos topography is clearly a key factor that produces a contrast between escarpments (such as Felipe Camiroaga and Balmaceda) where difficulty of access requires that street networks are designed and produced incrementally, and flatlands (such as El Boro) where more orderly street grids are possible. On escarpments the establishment of plot boundaries is irregular and generally follows rather than precedes the construction of buildings; here streets, plots and buildings tend to co-evolve through a series of incremental adaptations. Existing tracks give access to the steep terrain and determine the initial settlement which progressively spreads through the extension of main roads and the sprouting of lateral roads or paths. Escarpments also differ from flatlands in the emergence of a street/lane hierarchy on escarpments because pedestrian paths can traverse the steeper slopes where roads are not possible. We also find minor differences between escarpment settlements as diagrammed in Fig. 9. The steeper slopes and denser development of Balmaceda produce a sharper zig-zag pattern of main roads with connecting streets and then smaller cul-de-sac lanes. The ridges of Felipe Camiroaga produce more linear a pattern of side loop-roads that reconnect with the main road.

Fig. 9.

Morphogenic patterns on escarpments

Some form of plotting is evident in all of the studied settlements, whether emerging before or after the construction of buildings. In the case of social housing the plotting is formal and precedes construction. It is notable that while informal accretions to the row-housing have not encroached onto public space, territorial ambiguity arises in the collective apartment blocks (San Gabriel) where ground floor additions often encroach onto the common spaces. Informal plotting embodies an informal urban design code. While plot boundaries may be established before or after construction, they establish an agreed set of territories beyond which further construction is proscribed. When land is invaded the first imperative is to rapidly occupy the site, however precariously, and then upgrade. In the first phase of El Boro, the plotting was well-organized but unsettled and soon demolished; the less organized but settled plan that followed has survived. The evidence in these cases is that once plots are both established and settled, these codes are generally observed and enforced.

The density of informal settlement differs across these cases in terms of both plot coverage and building height. The detached house typology of Felipe Camiroaga has low plot coverage (30–50%) with substantial private open space, while other settlements often reach 100% plot coverage. Light materials such as timber and steel predominate in most informal construction. This is a clear difference from most of Latin America and is most likely due to the high earthquake risk. Light materials also enable rapid construction to consolidate land claims and are easy to recycle for adaptation or upgrading. Masonry construction can be found in the informal additions to social housing where legal tenure is more secure.

The process of settlement also varies a good deal in the speed and manner of encroachment. In the campamentos an early spurt to establish the land claim is common followed by intensification over time, while the informalization of social housing occurs at a slower pace. The slowest intensification process is found in collective housing blocks (such as San Gabriel), where there are no plots and apartments are extended by the addition of rooms, balconies, and fenced yards, often requiring negotiation between neighbours. While ground floor additions predominate, additions can also start from upper levels, reducing sunlight to the floors beneath while also producing a framework for later infil—somewhat akin to both a ‘supports’ approach (Habraken 1972) and the half-house approach (Aravena et al. 2004) where an infrastructural shell is filled informally. The row-housing and apartment blocks have effectively become what is generally known as ‘core housing’ where a small serviced core is designed to be expanded by residents over time (Garcia-Huidobro et al. 2011; Doshi 1988).

The outcomes of programs such as Vivienda Progresiva, have long been analysed in Chile (Mora et al. 2009), yet there remains a lack of knowledge regarding the adaptive capacities of social housing (Chatrau et al. 2020). The more informal campamento receive less attention, as their urban design is considered inferior and unplanned.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates how multi-scalar mapping can be used to understand morphogenic patterns of informal settlement in Chilean cities. It is not hard to see the causes of informal settlement in the myriad of factors that generate urban poverty and socio-economic inequality, particularly the confluence of rural-to-urban migration under neoliberal economic regimes (Roy 2005; Davis 2006). However, what is most at stake here is the livelihoods of these population; these settlements are enduring neighbourhoods of these cities, and the overwhelming majority are permanent. Whether or not issues of inequality are addressed, these urban conditions will also need to be addressed.

These findings are not conclusive; this sample of neighbourhoods is not random, and many dimensions remain unexplored. While limited in scope, this work begins to reveal both the morphologies of informal development and the emergent logics of informal urban design. It demonstrates key factors that impact the morphology of informal settlements and provides scope for both deeper analysis and a wider survey of Chilean cities. Key questions include the social, political and economic organization of these communities, together with processes of occupation, tenure and the enforcement of informal codes. If we accept that informal settlement is mostly permanent then we need a better understanding of how it is designed and produced, leading to questions of how it might be more effectively designed, anticipated, and upgraded. This mode of production cannot be easily replaced nor instantly formalized without damaging the livelihoods of the urban poor. The challenge is to work with urban informality, and this requires a broad and deep knowledge base about how self-organized infrastructure is designed and planned. Morphogenic studies can help in understanding that informal settlement is already a form of upgrading of unutilized capacity for development, and in understanding how such settlements become slums. Any effective slum-upgrading process relies on a better understanding of informal morphogenesis as a mode of production. This study also demonstrates some of the multiple morphologies through which informal settlement produces housing and urban infrastructure. Informal urban design and planning is not one thing; our attempts to better understand and engage with it will benefit from multiple approaches and at multiple scales.

Biographies

Víctor Alegría

is a researcher in the Department of Urbanism at the University of Chile. He is an architect and holds a Master of Urban Design from the University of Melbourne. His research interest are urban morphology, informal settlements and green infrastructure in cities of the Global South.

Kim Dovey

is Professor of Architecture and Urban Design and Director of the Informal Urbanism Research Hub (InfUr). His research on social issues in architecture and urban design has included investigations of urban place identity, creative clusters, transit-oriented urban design and the morphology of informal settlements.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Víctor Alegría, Email: victor.alegria@uchilefau.cl.

Kim Dovey, Email: dovey@unimelb.edu.au.

References

- Alexander C, Neis H, Anninou A, King I. A new theory of urban design. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro d’Alençon P, Smith H, Álvarez de Andrés E, Cabrera C, Fokdal J, Lombard M, Mazzolini A, Michelutti E, Moretto L, Spire A. Interrogating informality. Habitat Interanitonal. 2018;75:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2018.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angel S, Parent J, Civco DL, Blei A, Potere D. The dimensions of global urban expansion. Progress in Planning. 2011;75(2):53–107. doi: 10.1016/j.progress.2011.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aravena A, Montero A, Cortese T, De la Cerda E, Iacobelli A. Quinta Monroy. ARQ (santiago) 2004;57:30–33. doi: 10.4067/S0717-69962004005700007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano N. Historia local del Acceso popular al suelo. El caso de la ciudadde Viña del Mar. Revista INVI. 2005;20(54):56–84. [Google Scholar]

- Baud I, Kuffer M, Pfeffer K, Sliuzas R, Karuppannan S. Understanding heterogeneity in metropolitan India. International Journal of Applied Earth Observations and Geoinformation. 2010;12(5):359–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2010.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brain Valenzuela I, Prieto Suárez J, Sabatini Downey F. Vivir enCampamentos: ¿Camino hacia la vivienda formal o estrategia de localización paraenfrentar la vulnerabilidad? EURE (santiago) 2010;36(109):111–141. doi: 10.4067/S0250-71612010000300005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Celhay P, Gil D. The function and credibility of urban slums. Cities. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatrau F, Schmitt C, Rasse A, Martínez P. Consideraciones para programar la regeneración de condominios sociales en altura. Estudio comparado de tres casos en Chile. Revista INVI. 2020;35(100):143–173. doi: 10.4067/S0718-83582020000300143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras Y, Neville L, González R. In-formality in access to housing for Latin American migrants. International Journal of Housing Policy. 2019;19(3):411–435. doi: 10.1080/19491247.2019.1627841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conzen MRG. Alnwick, Northumberland: A study in town-planning analysis. London: G. Philip; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Planet of slums. London: Verso; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Ramón A. La población informal. Poblamiento de la periferia de Santiago de Chile. 1920 1970. Revista EURE – Revista De Estudios Urbano Regionales. 1990;16(50):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Doshi B. ‘Aranya township, Indore. Mimar: Architecture in Development. 1988;28:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K. Informal urbanism and complex adaptive assemblage. International Development Planning Review. 2012;34(4):349–368. doi: 10.3828/idpr.2012.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K. Urban Design Thinking: A conceptual toolkit. London: Bloomsbury; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K, Kamalipour H. Informal/formal morphologies. In: Dovey K, Pafka E, Ristic M, editors. Mapping urbanities. New York: Routledge; 2018. pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey K, King R. Forms of Informality. Built Environment. 2011;37(1):11–29. doi: 10.2148/benv.37.1.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dovey, K., van Oostrum, M., Chatterjee, I., and Shafique, T. 2020. Towards morphogenesis of informal settlements. Habitat International. 10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102240.

- Garcia-Huidobro F. Torres, Torrito D, Tugas N. The Experimental Housing Project (PREVI), Lima. Architectural Design. 2011;81(3):26–31. doi: 10.1002/ad.1234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. and E. González. 2014. El programa de Vivienda progresiva en Chile 1990–2002. Inter-American Development Bank Publication. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/El-programa-de-vivienda-progresiva-en-Chile-1990-2002.pdf, accessed 18 January 2022

- Gilbert A. Power, ideology and the Washington consensus: The development and spread of Chilean housing policy. Housing Studies. 2002;17(2):305–324. doi: 10.1080/02673030220123243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habraken N. Supports: An alternative to mass housing. London: Architectural Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim B. Mediterranean urbanism. Berlin: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo R. La vivienda social en Chile: la acción del estado en un siglo deplanes y programas. Scripta Nova, Revista Electrónica De Geografía y Ciencias Sociales Universitat De Barcelona. 1999;3(45):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo R. La vivienda social en Santiago de Chile en la segunda mitad delsiglo XX: Actores relevantes y tendencias espaciales. In: de Mattos C, Ducci ME, Rodríguez A, Yáñez Warner G, editors. Santiago en la globalización ¿Una nueva ciudad? Ediciones Sur: Santiago; 2004. pp. 219–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier B, Greene M, Desyllas J. Self-generated neighbourhoods. Urban Design International. 2000;5(2):61–96. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imilán W, Osterling E, Mansilla P, Jirón P. El campamento en relación conla ciudad: Informalidad y movilidades residenciales de habitantes de Alto Hospicio. Revista INVI. 2020;35(99):57–80. doi: 10.4067/S0718-83582020000200057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jirón P. The evolution of informal settlements in Chile. In: Hernández F, Kellett P, Allen LK, editors. Rethinking the informal City. New York: Berghahan Books; 2010. pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kostof S, Tobias R. The city shaped. London: Thames & Hudson; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kuffer M, Barros J, Sliuzas R. The development of a morphological unplanned settlement index using very-high-resolution (VHR) imagery. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems. 2014;48:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2014.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnetzoff F. Urban and housing policies under Chile’s Military Dictatorship 1973–1985. Latin American Perspectives. 1987;14(2):157–186. doi: 10.1177/0094582X8701400203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lizarralde G. The invisible houses. New York: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- López E, Flores P, Orozco H. Inmigrantes en campamentos en Chile: ¿mecanismo de integración o efecto de exclusión? Revista INVI. 2018;33(94):161–187. doi: 10.4067/S0718-83582018000300161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mac-Donald J. Ciudad, Pobreza, Tugurio. Aportes de los pobres a la construcción del hábitat popular. Hábitat y Sociedad. 2011;3:13–26. doi: 10.12795/HabitatySociedad.2011.i3.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. Streets and patterns. New York: Spon; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall S. Cities, design and evolution. Abingdon: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mehaffy MW. Generative methods in urban design. Journal of Urbanism. 2008;1(1):57–75. doi: 10.1080/17549170801903678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MINVU, Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. 2018. Catastro Nacional de Campamentos 2018. Catastro de campamentos, www.minvu.cl/catastro-de-campamentos/, accessed 8 August 2020.

- Mora R, Greene M, Gaspar R, Moran P. Exploring the mutual adaptive process of home-making and incremental upgrades in the context of Chile’s Progressive Housing Programme (1994–2016) Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. 2009;35(1):243–264. doi: 10.1007/s10901-019-09677-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, E. and S. Rojas. 1986. Relocalización socio-espacial de la pobreza, políticaestatal y presión popular 1979–1985. Santiago: Flacso. Working Paper no. 280.

- Moudon AV. Urban morphology as an emerging interdisciplinary field. Urban Morphology. 1997;1(1):3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moudon AV. Introducing supergrids, superblocks, areas, networks, and levels to urban morphological analyses. Iconarp International Journal of Architecture and Planning. 2019;7:01–14. doi: 10.15320/ICONARP.2019.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori S. Studi per una operante storia urbana di Venezia. Roma: Instituto poligrafico dello Stato, Libreria dello Stato; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien D, Carrasco S. Contested incrementalism: Elemental’s Quinta Monroy settlement fifteen years on. Frontiers of Architectural Research. 2021;10(57):263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.foar.2020.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda L, Rodriguez Torrent JC, Mansilla Quiñones P, Pino Vásquez A. El acceso al agua en asentamientos informales. Bitácora Urbano Territorial. 2020;30(1):151–165. doi: 10.1177/0956247818790731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Payne G. Urban land tenure policy options: Titles or rights? Habitat International. 2001;25(3):415–429. doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(01)00014-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pino A, Ojeda L. Ciudad y hábitat informal: Las tomas de terreno y la autoconstrucción en las quebradas de Valparaíso. Revista INVI. 2013;28(78):109–140. doi: 10.4067/S0718-83582013000200004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association. 2005;71(2):147–158. doi: 10.1080/01944360508976689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A, Alsayyad N. Urban informality: Transnational perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia. Lexington; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo R. the last slum: Moving from illegal settlements to subsidized home ownership in Chile. Urban Affairs Review. 2010;46(1):90–118. doi: 10.1177/1078087410368487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salingaros NA. Complexity and urban coherence. Journal of Urban Design. 2000;5(3):291–316. doi: 10.1080/713683969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer BC. The epistemology of urban morphology. Urban Morphology. 2015;20(1):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Techo Chile. 2018. Centro de Investigación Social, Chile. Monitor de campamentos, Catastro 2018, www.techo.org/chile/centro-de-investigacion-social/, accessed 5 October 2020

- Taubenböck H, Kraff N, Wurm M. The morphology of the Arrival City. Applied Geography. 2018;92:150–167. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2018.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JFC. Housing as a Verb. In: Turner JFC, Fichter R, editors. Freedom to build; dweller control of the housing process. New York: Macmillan; 1972. pp. 148–175. [Google Scholar]

- UN Habitat. 2016. Slum Almanac 2015–2016, Tracking Improvement in the Lives of Slum Dwellers. UN Habitat

- Vergara-Perucich J-F, Arias-Loyola M. Bread for advancing the right to the city. Environment and Urbanization. 2019;31(2):533–551. doi: 10.1177/0956247819866156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shuang Chen S, Gao Q, Shen Q, Kimirei IA, Mapunda DW. Morphological characteristics of informal settlements and strategic suggestions for urban sustainable development in Tanzania. Sustainability. 2020 doi: 10.3390/su12093807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]