Abstract

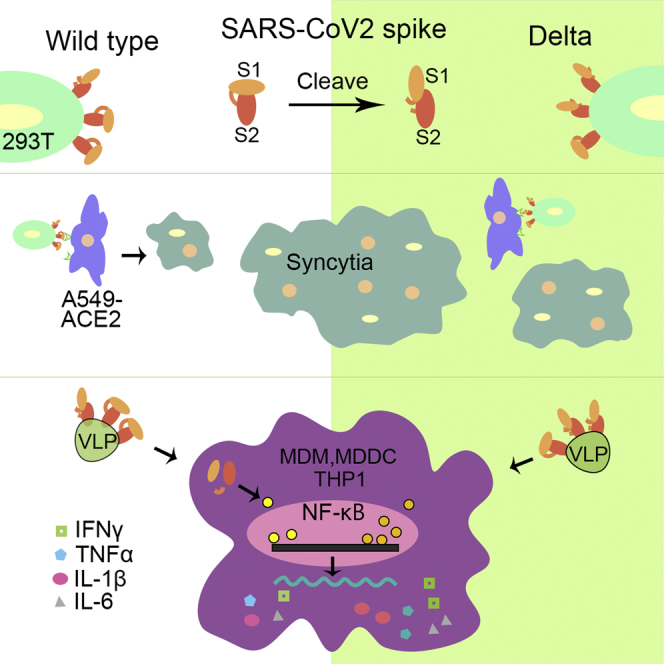

The Delta variant had spread globally in 2021 and caused more serious disease than the original virus and Omicron variant. In this study, we investigated several virological features of Delta spike protein (SPDelta), including protein maturation, its impact on viral entry of pseudovirus and cell-cell fusion, and its induction of inflammatory cytokine production in human macrophages and dendritic cells. The results showed that SPΔCDelta exhibited enhanced S1/S2 cleavage in cells and pseudotyped virus-like particles (PVLPs). Further, SPΔCDelta elevated pseudovirus entry in human lung cell lines and significantly enhanced syncytia formation. Furthermore, we revealed that SPΔCDelta-PVLPs had stronger effects on stimulating NF-κB and AP-1 signaling in human monocytic THP1 cells and induced significantly higher levels of proinflammatory cytokine, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, released from human macrophages and dendritic cells. Overall, these studies provide evidence to support the important role of SPΔCDelta during virus infection, transmission, and pathogenesis.

Subject areas: Virology, Molecular biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

SARS-CoV-2 Delta-SP exhibits enhanced cleavage and more efficient pseudovirus entry

-

•

Delta-SP enhances syncytia formation in A549 cells expressing ACE2

-

•

Delta-SP stimulates higher NF-κB and AP1 signaling pathway activities

-

•

Delta-SP stimulates higher proinflammatory cytokine production in MDMs and MDDCs

Virology; Molecular biology

Introduction

The emergence of the highly pathogenic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been a major concern and threat to public health for two years. As of early April 2022, approximately 495 million COVID-19 cases and more than six million deaths were reported globally (WHO, 2022). COVID-19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is a member of betacoronaviridae with a single-stranded 30 kb positive-sense RNA genome encoding 29 proteins (Srivastava et al., 2021). Within 2 years, multiple variants of SARS-CoV-2 have emerged (Galloway et al., 2021; Greaney et al., 2021; Karim and Karim, 2021; Nonaka et al., 2021; Paiva et al., 2021; Resende et al., 2021; Santos and Passos, 2021; Tegally et al., 2020; Volz et al., 2021). Delta variant, which was first detected in India and derived from the Pango lineage B.1.617.2, was the most dominant variant of concern (VOC) and had accounted for approximately 99% of new cases of coronavirus worldwide in 2021 (Banu et al., 2020; Ranjan et al., 2021; Sahoo et al., 2021; Worldometer, 2021). Studies suggested that Delta variant infection has a shorter incubation period but a greater viral load (>1,000 times) than earlier variants (Reardon, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). Further, the patients contracted with Delta variant have higher hospitalization rate and more severe outcomes than those infected with Omicron, the current dominant variant (Nyberg et al., 2022; Twohig et al., 2021). Even though vaccines were efficacious against the Delta variant, especially reducing the severity of the disease, studies also demonstrated that Delta variant can partially escape neutralizing monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies elicited by vaccination and the protection moderately declined with increasing time (Bruxvoort et al., 2021; Lopez Bernal et al., 2021; Planas et al., 2021). Therefore, it is important to understand the molecular mechanisms of the increased transmissibility and variated pathogenesis of these SARS-CoV-2 variants to facilitate the development of vaccines and therapeutic drugs against COVID-19.

Different VOCs harbor various mutations on their spike protein (SP). The SP of coronavirus is responsible for viral attachment and entry to the host cells (Huang et al., 2020b). The matured SP is cleaved to generate S1 and S2 subunits at specific cleavage sites (Murgolo et al., 2021). The S1 subunit (aa 14–685) is responsible for receptor binding through its receptor-binding domain (RBD). The S2 subunit (aa 686–1273) mediates membrane fusion to facilitate cell entry (Bertram et al., 2013; Hoffmann et al., 2020b; Peacock et al., 2021b). Mutations in SP have resulted in the high rates of transmission and replication of various variants (Escalera et al., 2022; Ye et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021a; Zhou et al., 2021) and the immune evasion from antibody neutralization (McCallum et al., 2021, 2022; Mlcochova et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a). The SP of the Delta variant has eight mutations compared with the original virus, including T19R, Δ156– Δ157, and R158G in the N-terminus domain (NTD), D614G, L452R, and T478K at the RBD, P681R close to the furin cleavage site, and D950N at the S2 region (Cherian et al., 2021; Planas et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a). It has been demonstrated that the mutations at the NTD of Delta SP alter the antigenic surface, thus leading to the less binding affinity with the neutralizing antibodies (Zhang et al., 2021a).

Furthermore, the multibasic furin cleavage S1/S2 site (681-PRRAR↓SV-687) of SARS-CoV-2 is reported to be critical for the pathogenesis in mouse models, and also be responsible for the cell-cell fusion, which is absent in other group-2B coronaviruses (Coutard et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2020). The P681 H/R polymorphism at this cleavage site has been identified in several variants, including P681H in Alpha and Omicron, while P681R in Kappa and Delta (Escalera et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021). It was shown that P681R mutation endows Delta variant with special features that facilitate the SP cleavage, the TMPRSS2-mediated fusogenicity, and the pathogenicity in hamster (Cherian et al., 2021; Peacock et al., 2021b; Saito et al., 2021). Study found that a chimeric Delta SARS-CoV-2 bearing the Alpha-SP (P681H) replicated less efficiently than the wild-type Delta variant, and the reversion of Delta P681R mutation to wild-type P681 attenuated Delta variant replication as well (Liu et al., 2021). These observations suggested that the P618R mutation that occurs in Delta variants contributes immensely to the high transmissibility rate, the high viral loads, and the competitive advantage over other prevailing VOCs (i.e. Alpha, Gamma, and Beta). We are therefore interested in further investigating how the P618R mutation impacts the high replication rate of Delta variants.

Like other high pathogenic viruses (influenza H5N1, SARS-CoV-1, and MERS-CoV), SARS-CoV-2 infection also induced excessive inflammatory response with the release of a large amount of proinflammatory cytokines (cytokine storm) that may result in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiorgan damage (Zhu et al., 2020). Clinical studies showed that the high mortality of COVID-19 is related to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in a subgroup of severe patients (Huang et al., 2020a), characterized by elevated levels of certain cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-1β, IL-10, MCP-1, and IP-10 (Hadjadj et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020a; Mehta et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020). The observed cytokine production induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or SP expression has been linked with nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and activator protein-1(AP-1) signaling pathways that can induce the expression of a variety of proinflammatory cytokine genes (Neufeldt et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2021). Like other RNA virus, SARS-CoV-2 was found to activate NF-κB and AP-1 transcription factors following the sensing of viral RNAs or proteins by different pathogen pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and associated signaling cascades, including RLRs and TLRs (Pantazi et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021). In addition, angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1)-MAPK signaling (Patra et al., 2020) and the cGAS-STING signaling (Neufeldt et al., 2022) have been identified responsible for the activation of NF-κB and the elevated expression of IL-6 in the SARS-CoV-2-infected or SP-expressing cells. However, whether Delta variant or its SP may initiate stronger cytokine storm in patients leading to more severe illness than other strains still requires more investigations.

The current study aims to characterize the cleavage/maturation of various SPs of SARS-CoV-2, especially the Delta variant SP, and their effects on viral entry, cell-cell fusion, cytokine production, and related signaling pathways. By using a SARS-CoV-2 SP-pseudotyped lentiviral vector or viral-like particles (PVLPs), we demonstrated that SPDelta enhanced S1/S2 cleavage, accelerated pseudovirus entry, and promoted cell-cell fusion. We also showed that SPDelta strongly activates NF-κB and AP-1 signaling in THP1 cells. Furthermore, we observed that SPΔCDelta-PVLP stimulation promoted the production of several proinflammatory cytokines by human macrophages and dendritic cells.

Results

SARS-CoV-2 Delta SP exhibited enhanced cleavage and maturation in cells and in the pseudotyped virus

To investigate the functional role of SARS-CoV-2 Delta SP, we first synthesized cDNA-encoding SARS-CoV-2 Delta SP, as described in CDC’s SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions (CDC, 2021) (Figure 1A) and inserted cDNA into a pCAGG-expressing plasmid, as described in the STAR Methods. Previously described pCAGG-SPΔCWT- and pCAGG-SPΔCG614-expressing plasmids (Ao et al., 2021a) were also used in this study. Meanwhile, we constructed a pCAGG-SPΔCDelta-PD in which arginine (R) at the amino acid position of 681 and asparagine (N) at 950 in SPΔCDelta were reverted to the original proline (P) and aspartic acid (D) to test the effect of these amino acids on the function of SPΔCDelta (Figure 1A). To enhance the transportation of SP to the cell surface and increase the virus incorporation of SP, the cDNA encoding the C-terminal 17 aa in SARS-CoV-2 SP was deleted in all pCAGG-SPΔC plasmids (Ao et al., 2021a).

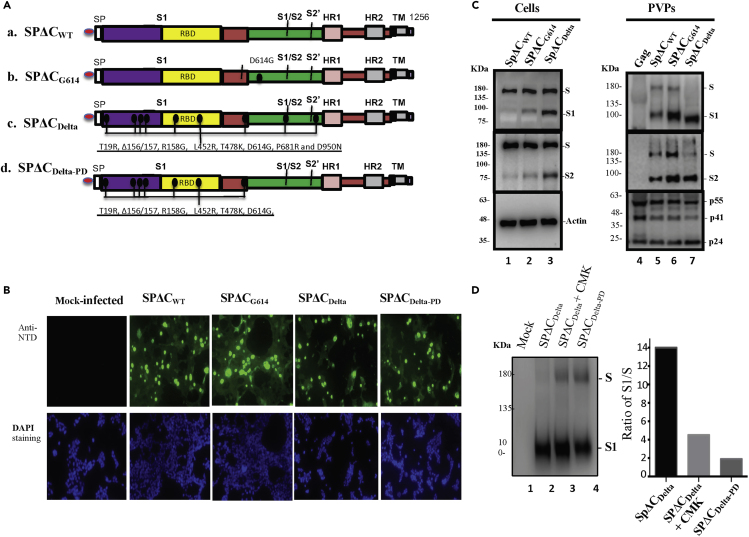

Figure 1.

The expression and cleavage of SARS-CoV-2 Delta spike protein (SP) in the cells and in the pseudotyped virus particles (PVPs)

(A) Schematic representation of the structure domains and mutations of SARS-CoV-2 SP and its variants. A C-terminal 17 aa of each of SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC was deleted in order to increase the incorporation of SP into the virus particles.

(B) 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-SPΔCwt, -SPΔCG614, -SPΔCDelta, or -SPΔCDeltaPD. The intracellular expression of each SPΔC in the transfected 293T cells was detected by immunofluorescence assay with SARS-CoV-2 S-NTD antibody. Scale bars = 100 μm.

(C) 293T cells were transfected with each SPΔC-expressing plasmid, HIV ΔRI/Env−/Gluc, and a packaging plasmid (pCMVΔ8.2) in HEK293T cells. As Gag-control, 293T cells were only transfected with pCMVΔ8.2 plasmid. WB was used to detect the expression and cleavage of various SPΔC and HIV Gag protein in cells and in PVPs. Full-length spike (S), cleaved S1 and S2 were annotated.

(D) SPΔCDelta-PVPs were produced in the absence or in the presence of a furin inhibitor (CMK) (25 μM) and SPΔCDeltaPD-PVPs were analyzed by WB using polyclonal anti-SP/RBD antibody (Left panel). The ratio of S1 relative to the full-length SP was also quantified by laser densitometry as indication of SP processing efficiencies (Right panel).

Panels (C and D) show the representative WB image from three independent experiments.

To examine the expression of various SPs in the cells and their incorporation in the SPΔC-pseudotyped viral particles (PVPs), each SPΔC-expressing plasmid was cotransfected with a multiple-gene-deleted HIV-based vector encoding a Gaussia luciferase gene (ΔRI/ΔEnv/Gluc) and a packaging plasmid (pCMVΔR8.2) in HEK293T cells, as described previously (Ao et al., 2021a). After 48 h of transfection, the expression of each SPΔC in the transfected cells was analyzed by an indirect immunofluorescence (IF) assay using human SARS-CoV-2 S-NTD antibodies. The results revealed that all SPΔCs were well expressed in the transfected cells or cell surface (Figure 1B). Meanwhile, the transfected cells and PVPs were lysed and processed with Western blot (WB) with anti-SP/RBD or anti-S2 antibodies, respectively (Figure 1C, top and middle panels). Interestingly, the data clearly showed that in the cells, SPΔCDelta was more efficiently processed from the S precursor into S1 and S2 than SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614 (Figure 1C, compare Lane 3 to Lanes 1 and 2). In PVPs, the majority of SPΔCDelta presented as a mature form (S1 and S2) compared to SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614 (Figure 1C, compare Lane 7 to Lanes 5 and 6), indicating that SPΔCDelta undergoes a more efficient maturation process. Surprisingly, S1 of SPΔCDelta but not S2 appeared to migrate faster than S1 of SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614 (Figure 1C, top panel). The molecular weight (MW) of S1WT and S1Delta was estimated through the Semi-Log plot (logMW-Relative migration) method, to be 103 kDa and 88 kDa, respectively, indicating that S1Delta shifted about 15 kDa faster than S1WT in the WB. The possible mechanism for this behavior is currently unknown.

The cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 SP into S1 and S2 most likely occurs by furin, and the P681R mutation of the SP Delta was suggested to enhance S1/S2 cleavability (Liu et al., 2021; Peacock et al., 2021a). We therefore further tested whether a furin protease inhibitor, a peptidyl chloromethylketone (CMK), or the reverse change in R681 of SPΔCDelta to P would alter the maturation rate of the S protein. The SPΔCDelta-PD-PVPs or SPΔCDelta-PVPs packaged in the presence or absence of CMK were analyzed by WB with anti-RBD antibody and quantified by densitometry using ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The results showed that either CMK treatment or SPΔCDelta-PD clearly negatively impacted the maturation of SPΔCDelta (Figure 1D).

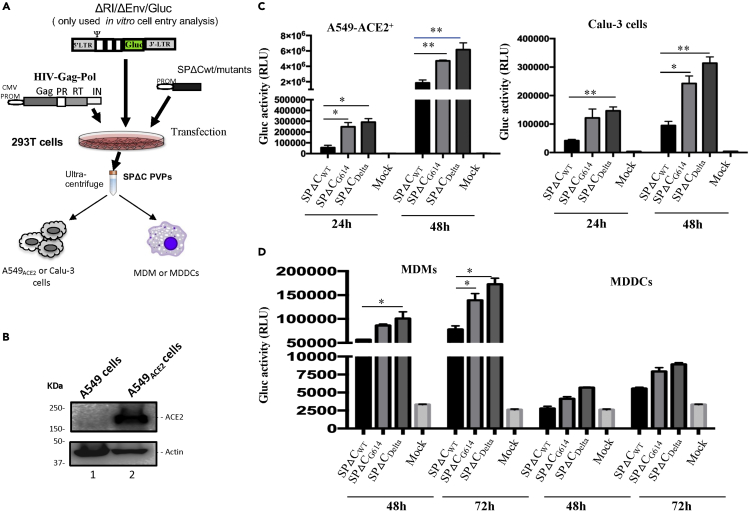

Delta-SP mediates more efficient pseudovirus entry in a lung epithelial cell line and primary macrophages

To investigate the impact of SPΔCDelta on viral entry, we produced Gluc-expressing Delta-SP-PVPs (Figure 2A) and tested the infectivity of different pseudoviruses in two human lung epithelial cell lines, Calu-3 and A549 cells. To increase susceptibility to SP-PVP infection, the A549ACE2 cell line was generated by transducing a lentivirus-expressing hACE2 and subsequent puromycin selection, as described in the STAR Methods. hACE2 expression in A549ACE2 cells was verified by WB (Figure 2B). Then, both cell lines were infected with equivalent amounts (adjusted with p24 values) of the SPΔCWT-, SPΔCG614-, and SPΔCDelta-PVPs for 3 h and washed. At 24 and 48 h post infection (p.i.), the supernatants were collected, and the viral entry levels of pseudoviruses were monitored by measuring Gluc activity. The results showed that in both cell lines, the SPΔCDelta-PVPs exhibited the highest entry efficiency, the SPΔCG614-PVPs had a slightly lower entry efficiency than SPΔCDelta, while the SPΔCwt-PVPs showed a significantly lower entry efficiency (Figure 2C). All of these results indicated that SPΔCDelta-PVPs had a significantly more efficient virus entry step than SPΔCwt.-PVPs in a single-cycle replication system.

Figure 2.

SP-pseudotyped virus entry assays on human lung cell lines, human macrophages (MDMs), and dendritic cells (MDDCs)

(A) Schematic representation of the procedures and the plasmids used for production of SARS-COV2-SPΔC-pseudotyped lentivirus particles (SPΔC-PVPs).

(B) An A549ACE2 cell line was generated by transducing A549 cells with a lentiviral vector (pLenti-C-ACE2).The ACE2 expression in the transduced cells was detected by WB using anti-ACE2 antibody.

(C and D) A549ACE2, Calu-3 cell lines, human MDMs, or MDDCs were infected with equal amounts of SPΔCwt, -SPΔCG614, or -SPΔCDelta-PVPs carrying Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) gene (adjusted by P24). At different time points, the Gluc activity in the supernatant of infected cultures was measured. The results are the mean values ± standard deviations (SD) of two independent experiments. Statistically significant differences (∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗, p ≤ 0.01) versus the SPΔCwt were determined by unpaired t test. No significant (ns) was not shown

Next, we checked the ability of SPΔC-PVPs to infect human differentiated macrophages and dendritic cells. Briefly, human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) or dendritic cells (MDDCs) were infected with equal amounts (adjusted with HIV p24 levels) of SPΔCwt--, SPΔCG614-, and SPΔCDelta-PVPs. At 48 and 72 h p.i., the Gluc activity in the supernatant from the infected cell cultures was monitored. The results showed that both human primary cells, especially MDMs, could be infected by SPΔC-PVPs, while SPΔCDelta- and SPΔCG614-PVPs displayed more efficient entry than SPΔCwt-PVPs (Figure 2D). All of these experimental observations indicate that SPΔCDelta-PVPs have a stronger ability to target MDMs than SPΔCwt-PVPs. The results also suggested that MDDCs can be targeted by SPΔC-PVPs but with less efficiency.

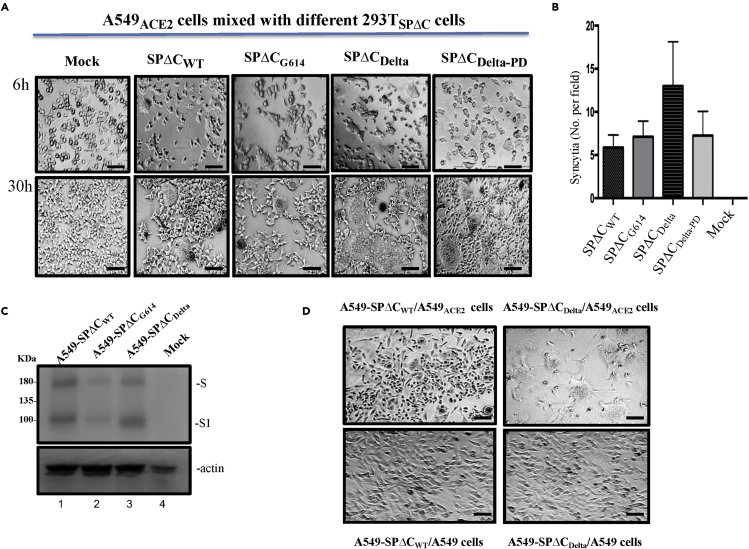

Delta-SP variant enhanced syncytia formation in lung epithelial A549 cells expressing ACE2

Previous studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 SP is able to possess fusogenic activity and form large multinucleated cells (syncytia formation) (Bussania et al., 2020; Cattin-Ortola et al., 2020). We then asked whether Delta-SP could possess higher fusogenic activity than other variants. Briefly, 293T cells were transfected with SPΔCWT, SPΔCG614, SPΔCDelta, or SPΔCDelta-PD plasmids by Lipofectamine 2000. At 24 h of transfection, we mixed SPΔC-expressing 293T cells with A549ACE2 cells at a ratio of 1:3. At 6 and 30 h post transfection, syncytial formation was observed under a microscope, and the results revealed that SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614 induced similar levels and sizes of syncytia. Intriguingly, an increasing number of syncytia formations were observed in the coculture of SPΔCDelta-expressing 293T and A549ACE2 cells (Figures 3A and B), indicating that SP from the Delta variant has a stronger fusogenic ability. However, SPΔCDelta-PD-expressing 293T/A549ACE2 cell coculture displayed less syncytia formation than SPΔCDelta (Figure 3B). A and B), suggesting the importance of P681R for the strong fusogenic activity of SP from the Delta variant.

Figure 3.

Delta-SP variant enhanced syncytia formation in lung epithelia cell line

(A) A549ACE2 cells were cocultured with 293T cells transfected with SPΔC or variants. The syncytia formation was monitored by microscopy at 6 and 30 h after coculture. Scale bars = 100 μm.

(B) Quantification of the numbers of syncytia formation in the cocultures at 6 h under bright-field microscopy. Results are the mean values ± standard deviations (SD) from two independent experiments.

(C) Expression of SPΔCwt, SPΔCG614, or SPΔCDelta in corresponding A549 stably cell lines was detected by WB using anti-SP/RBD antibody.

(D) A549ACE2 cells or A549 cells were cocultured with A549-SPΔCwt or A549-SPΔCDelta stable cells. The syncytia formation was visualized by microscopy at 30 h after co-culture. Scale bars = 100 μm.

To further confirm the strong fusogenic ability of SPΔCDelta, we also generated A549 cells stably expressing SPΔCwt, SPΔCG614, or SPΔCDelta (named A549-SPΔCDelta, A549-SPΔCG614, or A549-SPΔCwt cells) (Figure 3C). Since A549-SPΔCwt and A549-SPΔCDelta cells displayed similar levels of SPΔC expression based on a WB analysis, we then tested their fusogenic ability by mixing A549-SPΔCDelta or A549-SPΔCwt cells with the A549ACE2 cell line using a similar experimental process as described above. Meanwhile, A549-SPΔCDelta or A549-SPΔCwt cells were cocultured with A549 cells as a control. The results confirmed that the coculture of A549-SPΔCDelta cells and A549ACE2 cells formed large syncytia formation more efficiently than that of A549-SPΔCwt cells (Figure 3D), confirming the stronger fusogenic activity of the SP of the Delta variant.

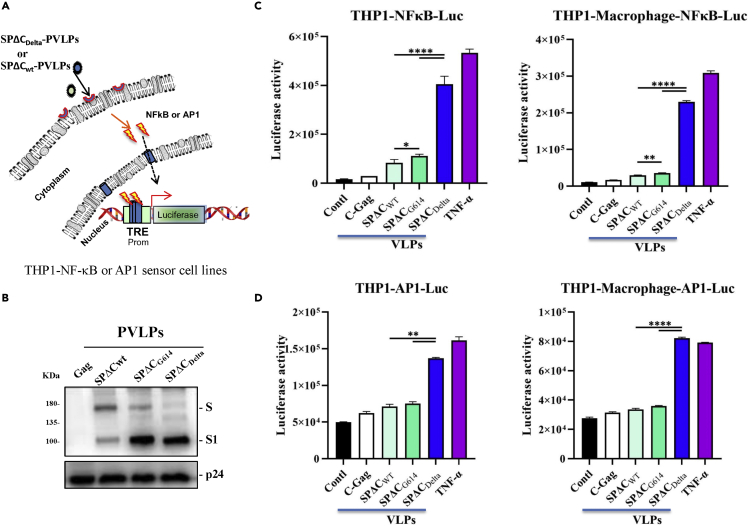

Delta variant SP stimulates higher NF-κB and AP1 signaling pathway activities

The severity of COVID-19 is highly correlated with dysregulated and excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines (Huang et al., 2020a). Given that the NF-κB and AP1 signaling pathways are among the critical pathways responsible for the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (Hojyo et al., 2020; Kawasaki and Kawai, 2014), we therefore examined the activities of these two signaling pathways triggered by SPΔC in the monocyte cell line THP1 and THP1-derived macrophages. First, we generated THP1-NF-κB-Luc and THP1-AP-1-Luc sensor cell lines by transducing THP1 cells with a lentiviral vector encoding the luciferase reporter gene driven by NFκB- or AP1-activated transcription response elements (Figure 4A), as described in the STAR Methods. To obtain THP1-derived macrophages, THP-1-NF-κB-Luc and THP1-AP-1-Luc sensor cell lines were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (100 nM) for 3 days. Additionally, we produced genome-free SPΔC-PVLPs by co-transfecting each SPΔC-expressing plasmid with a packaging plasmid (pCMVΔR8.2) in 293T cells, and the expression of SPΔC in the purified PVLPs was verified by WB with an anti-RBD antibody (Figure 4B). Then, different THP1 sensor cell lines and THP1-derived macrophages were treated with the equal amounts of SPΔC-PVLPs (adjusted by p24) for 6 h, and the luciferase activity in treated cells was measured by a luciferase assay system (Promega). Interestingly, we found that the NF-κB activity induced by SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614-PVLPs was slightly higher than that induced by the VLP control (Gag). However, the SPΔCDelta-treated THP1 cells/macrophages produced significantly higher (3- to 7-fold) NF-κB activity compared with SPΔCWT or SPΔCG614 (Figure 4C). Consistent with this finding, SPΔCDelta also triggered higher (∼2-fold) AP1 signaling pathway activities in THP1/macrophages than SPΔCWT or SPΔCG614 (Figure 4D). These results indicated that SPΔCDelta triggered significantly stronger signals to activate the NF-κB and AP1 pathways in the monocyte cell line THP1 and THP1-derived macrophages.

Figure 4.

SPΔCDelta-PVLPs stimulated NF-κB and Ap1-signal pathway in THP1 cells and THP1-derived macrophages

(A) The schematic diagram of NF-κB activity luciferase reporter assay. The THP1-NF-κB -Luc or THP1-AP1-Luc sensor cell line was incubated with SPΔCwt, -SPΔCG614, or -SPΔCDelta-PVLPs for 6 h, and the activation of NF-κB or AP1 signaling was detected by measurement of the luciferase activity.

(B) WB detected the incorporation of SPΔCwt, -SPΔCG614, or -SPΔCDelta in PVLPs using SARS-CoV-2 S-NTD antibody. The GagP24 was detected using mouse anti-P24 antibody.

(C and D) The THP1-NFκB-Luc or THP1-NFκB-Luc-derived macrophages, and THP1-AP-1-Luc cells or THP1-AP-1-Luc-derived macrophages were treated with equal amounts of SPΔCwt, SPΔCG614, or SPΔCDelta-PVLPs (adjusted by P24) for 6 h, and the activation of NF-κB or AP-1 signaling was detected by measurement of the Luc activity. Meanwhile, Gag-VLPs or TNF-α treatment were used as negative or positive control.

The results are the mean values ± standard deviations (SD) of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using unpaired t test, and significant p values are represented with asterisks (∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001). No significant (ns) was not shown.

Delta variant SP stimulates higher proinflammatory cytokine production in human macrophages (MDMs) and dendritic cells (MDDCs)

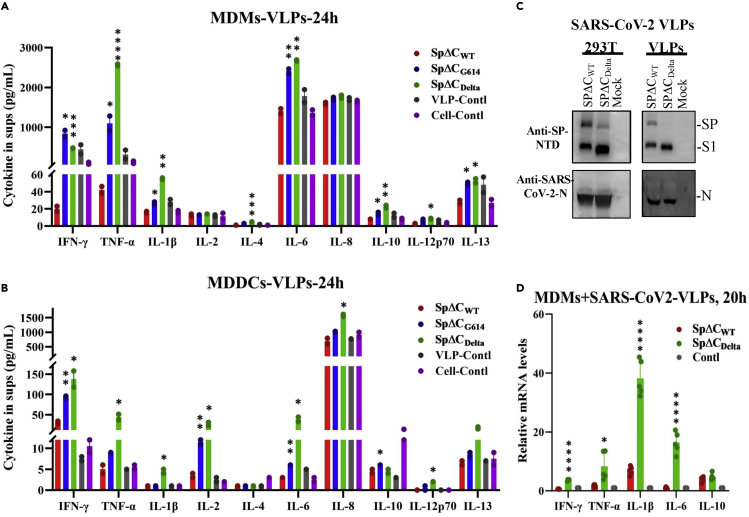

Previous studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection can stimulate the production of immunoregulatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-10) in human monocytes and macrophages (Boumaza et al., 2021). We further investigated whether SP of the Delta variant can induce higher levels of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine in MDMs and MDDCs. Briefly, human MDMs and MDDCs were treated with the same amount (adjusted by p24) of SPΔC-PVLPs, including SPΔCWT-, SPΔCG614-, SPΔCDelta-PVLPs, or control VLPs (Gag-VLPs). After 24 h of incubation, the cytokines released in the supernatants were determined by an MSD (Meso Scale Discovery) immunoassay. The results revealed that SPΔCWT-PVLP stimulation did not result in a significant change in cytokine release from MDMs compared to the control VLPs (Figure 5A). However, in MDMs, SPΔCDelta-PVLPs induced significantly higher levels of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, while SPΔCG614-PVLPs also induced increase of these cytokines but overall to a less extent, when compared with SPΔCWT-PVLPs (Figure 5A). For example, the SPΔCDelta-PVLPs elevated TNF-α level 61-fold in comparison with SPΔCWT-PVLPs, contrastingly, SPΔCG614-PVLPs only increased to approximately 33-fold. Nevertheless, all of SPΔC-PVLPs showed no stimulating effects on IL-2 and IL-8 production. Interestingly, SPΔCDelta-PVLPs and SPΔCG614-PVLPs also slightly increased anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, indicating the negative feedback of inflammation may exist during these stimulations.

Figure 5.

SpΔCDelta-PVLPs and sVLPs stimulated proinflammatory cytokines release in human MDM and MDDCs

(A and B) Human MDMs (A) or MDDCs (B) were treated with equal amount of SPΔCwt, SPΔCG614, or SPΔCDelta –PVLPs (adjusted by p24). HIV Gag-VLPs-treated and non-treated MDMs or MDDCs were used as negative controls. After 24 h, the cell culture supernatants were collected and different cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, and TNF-α, were measured by MSD immunoassay (Meso Scale Discovery).

(C) The produced SARS-CoV-2 VLPs (sVLPs) containing SPΔCWT or SPΔCDelta were examined by Western blot with anti-SP-NTD and anti-SARS-CoV-2-N antibodies.

(D) Human MDMs were treated with equal amounts of SPΔCWT- or SPΔCDelta-sVLPs (adjusted by amounts of SP) or not treated for 20 h. The relative cytokine mRNA levels in MDMs were determined by RT-qPCR and calculated through 2−ΔΔCt method.

The results were the mean ± standard deviations (SD) of biologic replicates. Statistical significance (against SPΔCWT) was determined using unpaired t test, and significant p values are represented with asterisks (∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001). No significant (ns) was not shown.

Surprisingly, in MDDCs, SPΔCDelta-PVLP stimulation resulted in a significant increase in most proinflammation cytokines we tested, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12p70 (Figure 5B). Among them, IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-2 were the most increased cytokines (8- to 13-fold), followed by IFN-γ and IL-1β (5- to 6-fold). The levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-6 in the supernatants of SPΔCG614-PVLPs-treated MDDCs were higher than that of SPΔCWT-PVLPs or control VLPs. In contrast, IL-10 production appears to be negatively regulated by all SPΔC-PVLPs, including the control VLPs.

To further verify the differential cytokine expressions in MDMs can be induced by SARS-CoV-2 VLPs (sVLPs), we produced SPΔCWT or SPΔCDelta-incorporated sVLPs by co-transfecting with SARS-CoV-2 N, M, and E protein expression plasmids with SPΔCWT or SPΔCDelta plasmid into 293T cells. After 48 h, the sVLPs in the supernatants were purified, as described in STAR Methods. Then, equal amounts (10 ng, SP) of SPΔCWT-sVLPs or SPΔCDelta-sVLPs were used to treat MDMs for 20 h. The relative mRNA levels of different proinflammatory cytokines in sVLPs-treated MDMs were determined by RT-qPCR. Interestingly, the results showed that sVLPs are able to stimulate cytokine mRNA expression in MDMs compared with untreated MDMs, and SPΔCDelta-sVLPs induced significantly higher mRNA levels of IFNγ, TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-6 (Th1 cytokine) than SPΔCWT-sVLPs (Figure 5D), while similar mRNA levels of IL-10 (Th2 cytokine) were observed in SPΔCDelta-sVLP and SPΔCWT-sVLP. These findings are consistent with the results shown in Figure 5A that increased cytokine protein levels in MDMs were induced by SPΔCDelta-HIV-VLPs in comparison with SPΔCWT-HIV-VLPs. Altogether, the above results indicated that sVLP-associated SPΔCDelta could induce higher levels of various proinflammatory cytokines tested than sVLP-associated SPΔCWT in human MDMs and MDDCs.

Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 high-transmissible Delta variant became the predominant strain worldwide in 2021 (Zhou et al., 2021). Although currently Delta has been replaced by new dominant variant Omicron in 2022, it is still important to understand the mechanisms of the increased transmissibility and high cytokine release triggered by Delta variant. In this study, we demonstrated the enhanced cleavage and maturation efficiency of SPΔCDelta in the produced pseudovirus particles, the more efficient SPΔCDelta-mediated pseudovirus entry, and a significantly increased cell-cell fusion. Furthermore, our analyses revealed that SPDelta in PVLPs/sVLPs had stronger activation effects on NF-κB and AP-1 signaling in THP1 cells and elevated the production of several essential proinflammatory cytokines by human MDMs and MDDCs, compared with SPWT in PVLPs/sVLPs.

SARS-CoV-2 infection requires the cleavage of SP at the polybasic S1/S2 site by furin, TMPRSS2, or cathepsin proteases (Johnson et al., 2021; Papa et al., 2021; Peacock et al., 2021a). This cleavage site is critical for the maturation of SARS-CoV-2 (Boson et al., 2021; Hoffmann et al., 2018, 2020a). The more efficient cleavage of SPΔCDelta into S1 and S2 than SPΔCWT and SPΔCG614 in both the cells and PVPs (Figure 1C, right panel) supports the notion that Delta variant has a higher infectivity than other variants because it has a higher maturation rate. The inhibition of SPΔCDelta cleavage by the furin protease inhibitor CMK emphasized the importance of furin for the enhanced cleavage of the Delta variant.

Among the mutations in the Delta variant SP, P681R mutation is of great importance because it is a part of the proteolytic cleavage site for furin and furin-like proteases (Saito et al., 2021). It is found to play a critical role to abrogate host O-glycosylation (Zhang et al., 2021b). The reverse mutation of 681R and 950N back to the original 681P and 950D on SPDelta (SPΔCDelta-PD) reduced the cleavage of the SPΔCDelta-PD to a level comparable to that of SPΔCWT, SPΔCG614, or SPΔCDelta in PVPs produced in the presence of furin inhibitor CMK (Figure 1D). Consistent with other reports (Peacock et al., 2021b; Saito et al., 2021), our results further demonstrated that the P618R mutation in SPΔCDelta is essential for the enhanced furin cleavage of SPDelta. Meanwhile, we also observed that S1Delta appeared to migrate faster than S1WT and S1G614. Although the mechanism is currently unknown, it could be related to the possible altered glycosylation content of SPΔCDelta. We have excluded the effect of mutations 681R and 950N on the shifting of S1Delta, based on our finding that the SPΔCDelta-PD (681P and 950D) displayed the same molecular weight of S1 as SPΔCDelta (Figure 1D). It will be worth further analysis whether other mutations in SPDelta contribute to the shift of S1Delta.

In this study, we also observed that SPΔCDelta enhanced cell-free pseudovirus entry in A549ACE2+ and Calu-3 cell lines and macrophages (Figures 1C and 1D), indicating that SPΔCDelta is an important factor contributing to the increased infectiousness of the Delta variant. Additionally, it was observed that the infection mediated by SPΔCDelta-pseudovirus was only slightly higher than that mediated by SPΔCG614-pseudovirus, suggesting that the G614 mutation present in SPDelta may be one of the main driving forces for the increased infectivity of the Delta virus (Daniloski et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). This finding is in agreement with previous studies showing that the D614G mutation in SARS-CoV-2 SP contributes immensely to virus infectivity and replication (Daniloski et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). It should be noted that our results were based on single-cycle SPΔC-pseudovirus replication; thus, the infection advantage of the native SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant needs further investigation.

It is well known that SP expressed at the surface of infected cells is sufficient to generate fusion with neighboring ACE2+ and TMPRSS2+ cells (Papa et al., 2021). Here, we further showed that significantly enhanced syncytia formation was observed when SPΔCDelta-expressing 293T or A549 cells were cocultured with A549ACE2 cells. The pneumocytes or bronchia epithelia syncytia were reported in the patients with severe COVID-19 (Bussani et al., 2020). These syncytia containing large and compact amounts of virus can be released into the apical lumen as the source of viral shedding (Beucher et al., 2021; Jackson et al., 2021). Studies suggested that the infected syncytia might facilitate SARS-CoV-2 infection and spread within the individual leading to severe disease (Beucher et al., 2021; Michael Rajah et al., 2021). Our observation raised potential importance of cell-to-cell fusion for SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in terms of the stronger virulence, as described previously (Michael Rajah et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2022). This finding is in agreement with recent reports that Delta (B.1.617.2) SP mediates highly efficient syncytia formation compared with wild-type SP (Michael Rajah et al., 2021; Mlcochova et al., 2021; Planas et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021a). Moreover, this efficient cell-to-cell transmission ability of SPΔCDelta was also suggested to enhance its resistance to antibody neutralization (Mlcochova et al., 2021; Planas et al., 2021). However, the short lifetime of syncytia may limit their influence and for other variants with a lower fusogenicity, it is reasonable to assume that syncytia may contribute little to the viral spread. It is worth noting that we did not investigate the impact of TMPRSS2 on the cell-cell fusion process. For SARS-CoV-2, cleavage of S by furin or other proteases at the S1/S2 site is required for subsequent cleavage by TMPRSS2/cathepsins at the S2′ site. Previous studies have demonstrated that TMPRSS2 could enhance the infectivity and fusogenic activity of different coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 (Buchrieser et al., 2020; Glowacka et al., 2011; Kleine-Weber et al., 2018; Matsuyama et al., 2010; Papa et al., 2021). Future investigations into the role of TMPRSS2 in SP Delta-induced syncytia formation and infection will provide a better understanding of the persistence, dissemination, and immune or inflammatory responses of Delta variants.

The severity of COVID-19 is highly correlated with dysregulated and excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines (Huang et al., 2020a). Hence, we also tested whether macrophages or dendritic cells act as major modulators of the immune response by producing a large amount of cytokines and chemokines to recruit immune cells and presenting antigens to them. The engagement of the SP of SARS-CoV-2 with the receptor ACE2 on THP1-derived macrophages is reported to initiate signaling pathways and activate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and MIP1a (Pantazi et al., 2021). Here, we showed that NF-κB and AP1 signaling pathway activities were also enhanced by SPΔCDelta compared with SPΔCWT in THP1 cells and THP1-derived macrophages, suggesting that SPΔCDelta might promote the inflammatory status of these cells. Similarly, the SP of SARS-CoV-1 has been discovered to activate NF-κB and stimulate the release of IL-6 and TNF-α (Wang et al., 2007).

Previous studies reported that high plasma levels of TNFα, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and other inflammatory mediators were found in patients with severe COVID-19, and the serum levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were strong and independent predictors of disease progression, severity, and death (Del Valle et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020a; Santa Cruz et al., 2021). Interestingly, we found that SPΔCDelta significantly enhanced the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) in both MDMs and MDDCs (Figure 5). Especially for MDDCs, increased levels of other proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-8, and IL-12p70, were also detected (Figure 5). However, SPΔCWT only exhibited induction of IFN-γ in MDDCs, but did not show any effect on other cytokine production of MDMs or MDDCs. This is in agreement with previous finding that upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, neither macrophage nor dendritic cells produce the proinflammatory cytokines (Niles et al., 2021). Mutations in Delta SP seem to be the key points that cause the differential expression of cytokines. However, due to the experimental limitation, we cannot distinguish whether this effect was mediated by SPΔCDelta through the interaction with ACE2 or the results of VLP particles entry into cells. It could be possible that the SPDelta enhanced viral entry and its binding to ACE2 contributes to the increased cytokine production. Given the fact that IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 are T-helper-1 (Th1) cytokines, it also suggests that the Th1/Th2 balance has further shifted to Th1 dominance after stimulation with SPΔCDelta-PVLP. Along with proinflammatory cytokines, three anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) were also increased in SPΔCDelta-PVLP/sVLP-treated macrophages compared with SPΔCWT-PVLP/sVLP-treated macrophages. Consistently, higher secretion of T-helper-2 (Th2) cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 has been reported in ICU patients than in non-ICU patients (Huang et al., 2020a). Their functions are to suppress both inflammation and the Th1 cellular response, indicating that the balances between pro- and anti-inflammation, as well as the balances between Th1 and Th2 cellular responses existing in patients, are important for the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 therapy. However, the lower IL-10 level in all PVLPs-treated MDDCs is surprising and the reason of this is unclear. In conclusion, SPΔCDelta-treated macrophages and DCs are in a higher inflammatory state and in a Th1-dominant Th1/Th2 balance.

Overall, we demonstrated that the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant SP exhibited enhanced cleavage and maturation, which may play an important role in viral entry and cell-cell transmission. Furthermore, we revealed that SPDelta had stronger effects on stimulating NF-κB and AP-1 signaling in monocytes and the release of proinflammatory cytokines from human macrophages and dendritic cells. All of these studies provide strong evidence to support the important role of Delta SP during virus infection, transmission, and pathogenesis.

Limitations of the study

Due to the high biosafety restriction for the SARS-CoV-2 infection experiments, we were unable to elucidate the functional associations between SPΔXDelta-mediated syncytia formation and SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission efficiency. This limitation impacts our better understanding of the mechanisms why SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant is more virulent than other variants, and also the effects of the increased cytokines production induced by SPΔXDelta on SARS-CoV-2 replication and pathogenesis.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD | Sino Biological | Cat# 40592-T62 |

| Recombinant human against SARS-CoV-2 S-NTD antibody | Elabscience | Cat# E-AB-V1030 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody (1A9) against SARS-CoV-2 SP-S2 | Abcam | Cat# ab273433; RRID: AB_2891068 |

| Anti-HIVp24 monoclonal antibody | Ao et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2011 | N/A |

| Anti-human ACE2 antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc | Cat# sc-390851; RRID: AB_2861379 |

| Donkey anti-rabbit-HRP secondary antibody | GE Healthcare | Cat# NA934; RRID: AB_772206 |

| Sheep anti-mouse-HRP secondary antibody | GE Healthcare | Cat# NA931; RRID: AB_772210 |

| FITC-conjugated anti-human secondary antibodies | Invitrogen | A18806 |

| Mouse monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD (clone#1034515) | R&D systems | MAB105401 |

| Rabbit monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 Nucleoprotein (NP) | Sino Biological | Cat# 40143-R019; RRID: AB_2827973 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E.coli DH5α competent cells | Biolab | 18265017 |

| GLuc-expressing SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC pseudotyped HIV-1-pseudoviruses (WT, Delta, G614) | This study | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC pseudotyped virus-like particles (VLPs) | This study | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Health human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) | This study | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Lymphoprep (Ficoll) | Axis Shield Poc As | Cat# 1114547 |

| macrophage colony stimulator (M-CSF) | R&D system | 416-ML-010 |

| granulocyte-macrophage-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) | R&D system | 7954-GM-010 |

| IL-4 | R&D system | 204-IL-010 |

| phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) | StemCell Technologies | 74042 |

| Furin inhibitor I, a peptidyl chloromethylketone (CMK) | Millipore Sigma | Cat# 344930 |

| puromycin | Invivogen | ant-pr-1 |

| Polyethylenimine | Sigma-Aldrich | 408727 |

| Polybrene | Sigma-Aldrich | TR-1003-G |

| paraformaldehyde | Millipore Sigma | 1040051000 |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | T8787 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent | Invitrogen | 11668019 |

| Trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) | Gibco | 25300062 |

| DMEM | Gibco | 11995065 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) Glow assay (coelenterazine substrate) | Nanolight Technology | #320-10 |

| Luciferase assay system | Promega | E1501 |

| V-PLEX proinflammatory Panel 1 (human) Kit | Mesoscale Discovery | Cat# K15049D-1) |

| PureLink RNA mini kit | Invitrogen | 12183020 |

| SuperScript VILO MasterMix | Invitrogen | 11755050 |

| PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | A25742 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| 293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| A549 | ATCC | CCL-185 |

| A594-hACE2 | This study | N/A |

| Calu-3 | ATCC | HTB-55 |

| THP1-NFκB-Luciferase | Ao et al., 2021b | N/A |

| THP1-AP-1-Luciferase | Ao et al., 2021b | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| hIFNγ-F/R (CAGGTCATTCAGATGTAGCGGAT, ACT CTCCTCTTTCCAATTCTTCAAAA) |

Invitrogen | N/A |

| hTNFα-F/R (CAGGTCCTCTTCAAGGGCCAA, GGGG CTCTTGATGGCAGAGA) |

Invitrogen | N/A |

| hIL-1β-F/R (ACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCA, GTCG GAGATTCGTAGCTGGAT) |

Invitorgen | N/A |

| hIL-6-F/ R (ACTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG, CCA TCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG) |

Invitorgen | N/A |

| hIL-10-F/ R (AAGGCGCATGTGAACTCCCT, CCAC GGCCTTGCTCTTGTTTT) |

Invitorgen | N/A |

| hGAPDH-F/R (ACAAC TTTGGTATCGTGGAAGG, GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC |

Invitorgen | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| HIV RT/IN/Env trideleted proviral plasmid containing the Gaussia luciferase gene (ΔRI/E/Gluc) and the helper packaging plasmid pCMVΔ8.2 encoding the HIV Gag-Pol plasmids | Ao et al., 2021a | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 spike expression plasmids (pCAGGS-nCoVSPΔC, pCAGGS-nCoVSPΔCG614) | Ao et al., 2021a | N/A |

| gene encoding SPΔCDelta or SPΔCDelta-PD | Genscript | N/A |

| pCAGGS-SPΔCDelta, pCAGGS-SPΔCDelta-PD,pEF1-SPΔCwt, pEF1-SPΔCG614 or pEF1-SPΔCDelta | This study | N/A |

| ACE2-expressing lentiviral vector (pLenti-C-mGFP-ACE2) | Origene | Cat# PS100093 |

| SARS-CoV-2-M expression plasmid (pUNO1-SARS2-M) | Sino Biological Inc. | puno1-cov2-m |

| SARS-CoV-2-E expression plasmid (pUNO1-SARS2-E) | Sino Biological Inc. | puno1-cov2-e |

| SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) Nucleoprotein expression plasmid, C-Myc tag (Codon Optimized), pCMV3-N | Sino Biological Inc. | VG40588-CM |

| Human ACE2 expression plasmid, mGFP-tagged (pLenti-C-mGFP-P2A-Puro-hACE2) | Origene | RC208442L4 |

| SARS-CoV-2 (2019-nCoV) Nucleoprotein expression plasmid, C-HA tag (Codon Optimized) | Sino Biological Inc. | VG40589-CY |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 2012 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Prism | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xiao-Jian Yao (xiaojian.yao@umanitoba.ca).

Materials availability

All unique reagents generated in this study are available upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Experimental models and subject details

Plasmid constructs

The SARS-CoV-2 SP protein-expressing plasmids (pCAGGS-nCoVSPΔC and pCAGGS-nCoVSPΔCG614) were described previously (Ao et al., 2021a). The gene encoding SPΔCDelta or SPΔCDelta-PD was synthesized (Genscript) and cloned into the pCAGGS plasmid, and each mutation was confirmed by sequencing. SARS-CoV-2-N, M, and E expressing plasmids were purchased from Sino Biological Inc. pEF1-SPΔCwt, pEF1-SPΔCG614 or pEF1-SPΔCDelta was constructed by inserting the cDNA encoding SPΔCWT, SPΔCG614 or SPΔCDelta through the BamHI and NheI sites into the pEF1-pcs-puro vector (Ao et al., 2008). The HIV RT/IN/Env trideleted proviral plasmid containing the Gaussia luciferase gene (ΔRI/E/Gluc) and the helper packaging plasmid pCMVΔ8.2 encoding the HIV Gag-Pol plasmids have been described previously (Ao et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016).

Cell culture, antibodies and chemicals

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T), human lung (carcinoma) cells (A549), A549ACE2, Calu-3 cells and THP1- sensor cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium or RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (F.B.S.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. To obtain human MDMs or MDDCs, human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs) from healthy donors were collected by sedimentation on a Ficoll (Lymphoprep; Axis-Shield) gradient, adherent to 24-well plates for 2 h, and then treated with macrophage colony stimulator (M-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and IL-4 (R&D system) for 7 days.

The THP1-NF-κB-Luc and THP1-AP-1-Luc sensor cell lines were described previously (Ao et al., 2021b). To obtain THP1-derived macrophages, THP-1-NF-κB-Luc and THP1-AP-1-Luc sensor cell lines were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (200 ng/mL) for 3 days followed by 2 days of rest, as previously described (Starr et al., 2018). A549-expressing human ACE2 (A549ACE2) cells were generated by transducing A549 cells with the ACE2-expressing lentiviral vector (pLenti-C-mGFP-ACE2) (Origene, Cat# RC208442L4) and then selected with puromycin according to the manufacturer’s procedure.

The rabbit polyclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 SP/RBD (Cat# 40,592-T62) and rabbit monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 N were obtained from Sino Biological, and human SARS-CoV-2 S-NTD antibody (E-AB-V1030) from Elabscience. Mouse monoclonal antibody (1A9) against SARS-CoV-2 SP-S2 (Cat# ab273433) was obtained from Abcam. Anti-HIVp24 monoclonal antibody was described previously (Ao et al., 2007; Qiu et al., 2011). Anti-human ACE2 antibody (sc-390851) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Furin inhibitor I, a peptidyl chloromethylketone (CMK) (Cat# 344,930), was obtained from Millipore Sigma.

Method details

Pseudovirus production and viral entry experiments

SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC pseudotyped viruses (CoV-2-SPΔCWT-PVs, CoV-2-SPΔCG614-PVs and CoV-2-SPΔCDelta-PVs) or pseudotyped virus-like particles (VLPs) were produced by transfecting HEK293T cells with pCAGGS-SPΔCWT, pCAGGS-SPΔCG614 or pCAGGS-SPΔCDelta and pCMVΔ8.2 with or without a Gluc-expressing HIV vector ΔRI/E/Gluc (Ao et al., 2021a). After 48 h of transfection, cell culture supernatants were collected, and VPs or VLPs were purified from the supernatant by ultra-centrifugation (32,000 rpm) for 2 h. The pelleted VPs or VLPs were resuspended in RPMI medium, and virus titers were quantified by HIV-1 p24 amounts using an HIV-1 p24 ELISA.

To measure the infection ability of SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC pseudotyped VPs, equal amounts of each SPΔC-PVs stock (as adjusted by p24 levels) were used to infect A549ACE2, Calu-3 cells, human MDMs or MDDCs. After different time intervals (24, 48 and 72 h), the supernatants were collected, and the viral entry levels were monitored by measuring Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) activity. Briefly, 50 μL of coelenterazine substrate (Nanolight Technology) was added to 10 μL of supernatant, mixed well and read in a luminometer (Promega, U.S.A.).

To evaluate the effects of various SCoV-2 SPΔC-VLPs on the NF-κB and AP-1 signaling pathways, the same amount of each SPΔC-pseudotyped VLP stock (10 ng, as adjusted by the p24 levels) was directly added to THP1-NF-κB-Luc or THP1-AP1-Luc sensor cells. After 6 h, the cells were collected and subjected to luciferase assay as described previously (Ao et al., 2021b). To test the effect of different SPΔC-VPs on cytokine production in MDMs and MDDCs, the same amount of each SPΔC-VP stock (20 ng, as adjusted by the p24 levels) was added to MDMs and MDDCs, and the supernatants were collected after 24 h. The cytokine (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, TNF-α) levels in the supernatants were measured using the MSD V-PLEX proinflammatory Panel 1 (human) Kit (Mesoscale Discovery, USA, Cat# K15049D-1) following the manufacturer’s procedure.

SARS-CoV-2 Virus Like Particles (sVLP) production

The SARS-CoV-2 Virus Like Particles (sVLP) were produced in 293T cells using co-transfection methods, as previously described (Syed et al., 2021). Briefly, 293T cells plated in a 10 cm dish were cotransfected with plasmids expressing SARS-CoV-2 N (6.7 μg), M (3.3 μg), E (3.3 μg), and SPΔC (2.5 μg) by PEI. SARS-CoV-2 VLP (sVLPs) containing supernatants were collected at 48–72 h post transfection, and sVLPs were purified by ultra-centrifugation in a Beckman 70Ti rotor (30,000 rpm, 3 h, 4 °C). Western Blot was performed to determine the sVLP formation and SP expression using anti-SP-NTD and anti-SARS-CoV-2 N antibodies. ELISA was performed to quantify the SP amount in the sVLPs with mouse-anti-SP-RBD coated plates. SP was detected by rabbit-anti-RBD followed by anti-rabbit-HRP secondary antibody.

Macrophage treatment and cytokines expression analysis by RT-qPCR

Human MDMs (5 × 105) were plated in a 24 well plate and incubated with sVLPs (10 ng) for 20 h. The cytokine expressions in VLP-treated MDMs were quantified by RT-qPCR. Briefly, the total RNAs of macrophages were extracted using the PureLink RNA mini kit (Invitrogen). The total RNA (2 μg) of each well was subjected to reverse transcription with Super-Script VILO MasterMix (Invitrogen). The qPCR was performed with cDNA (10 ng) using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Relative RNA levels were determined by 2-ΔΔCt method after normalization against the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. The primers used for qPCR were: hIFNγ-F/R (CAGGTCATTCAGATGTAGCGGAT, ACTCTCCTCTTTCC AATTCTTCAAAA), hTNFα-F/R (CAGGTCCTCTTCAAGGGCCAA, GGGGCTCTTGATGGCAGAG A), hIL-1β-F/R (ACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCA, GTCGGAGATTCGTAGCTGGAT), hIL-6-F/R (A CTCACCTCTTCAGAACGAATTG, CCATCTTTGGAAGGTTCAGGTTG), hIL-10-F/R (AAGGCGC ATGTGAACTCCCT, CCACGGCCTTGCTCTTGTTTT), hGAPDH-F/R (ACAACTTTGGTATCGTG GAAGG, GCCATCACGCCACAGTTTC).

Generation of different SPΔC-expressing A549 stable cell lines

Production of lentiviral vectors expressing different SPΔC: 293T cells were cotransfected with pEF1-SPΔCWT, pEF1-SPΔCG614 or pEF1-SPΔCDelta with packaging plasmid Δ8.2 and VSV-G expressing plasmid. Forty-eight hours post transfection, each lentiviral vector particle in the supernatant was collected. Then, each produced lentiviral particle was used to transduce A549 cells, and the transduced cells were selected with puromycin for one week. SPΔCWT/mutant expression in the different transduced A549 cells was evaluated by WB using an anti-RBD antibody.

Immunofluorescence assay

293T cells transfected with various SARS-CoV-2 SPΔC-expressing plasmids were grown on glass cover slips (12 mm2) in a 24-well plate. After 48 h, cells on the coverslip were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were then incubated with primary antibodies against the N-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2 SP followed by the corresponding FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies. The cells were viewed under a computerized Axiovert 200 fluorescence microscope (ZEISS).

Syncytium formation assay

293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-SPΔCWT, SPΔCG614, SPΔCDelta or SPΔCDelta-PD plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000. After 24 h, the cells were washed, resuspended and mixed with A549ACE2 cells at a ratio 1:3 and plated into 48-well plates. For syncytium formation of the stable cell line, A549-SPΔCWT or A549-SPΔCDelta cells were detached with 0.05% trypsin and mixed with A549 or A549ACE2 cells. At different time points, syncytium formation was observed, counted and imaged by bright-field microscopy (Axiovert 200, ZEISS).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical analysis of cytokine levels, including the results of Gluc assay, Luciferase assay, and various cytokine/chemokines assay, were performed using the unpaired t-test (considered significant at p ≥ 0.05) by GraphPad Prism 9 software.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Darwyn Kobasa for providing the Calu-3 cell lines and technique supports. Titus Olukitibi is a recipient of the University Manitoba Graduate scholarship. This work was supported by Canadian 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Rapid Research Funding (OV5-170710) by Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and Research Manitoba, and CIHR COVID-19 Variant Supplement grant (VS1-175520) to X.-J.Y. This work was also supported by the Manitoba Research Chair Award from the Research Manitoba (RM) to X.-J.Y.

Author contributions

Experimental design, X.Y., Z.A., and M.J.O.; Investigation, Z.A., M.J.O., and O.T.A.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, Z.A., M.J.O., and O.T.A.; Review, Z.A., M.J.O., and X.Y; Supervision, X.Y.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: August 19, 2022

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Ao Z., Chan M., Ouyang M.J., Olukitibi T.A., Mahmoudi M., Kobasa D., Yao X. Identification and evaluation of the inhibitory effect of Prunella vulgaris extract on SARS-coronavirus 2 virus entry. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Z., Wang L., Azizi H., Olukitibi T.A., Kobinger G., Yao X., Yao X.-j. Development and evaluation of an Ebola virus glycoprotein Mucin-like domain replacement system as a new dendritic cell-targeting vaccine approach against HIV-1. J. Virol. 2021;95:e0236820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02368-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Z., Huang G., Yao H., Xu Z., Labine M., Cochrane A.W., Yao X. Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase with cellular nuclear import receptor importin 7 and its impact on viral replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:13456–13467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610546200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Z., Huang J., Tan X., Wang X., Tian T., Zhang X., Ouyang Q., Yao X. Characterization of the single cycle replication of HIV-1 expressing Gaussia luciferase in human PBMCs, macrophages, and in CD4(+) T cell-grafted nude mouse. J. Virol. Methods. 2016;228:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Z., Yu Z., Wang L., Zheng Y., Yao X. Vpr14-88-Apobec3G fusion protein is efficiently incorporated into Vif-positive HIV-1 particles and inhibits viral infection. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banu S., Jolly B., Mukherjee P., Singh P., Khan S., Zaveri L., Shambhavi S., Gaur N., Reddy S., Kaveri K., et al. A distinct phylogenetic cluster of Indian severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 isolates. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020;7:ofaa434. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram S., Dijkman R., Habjan M., Heurich A., Gierer S., Glowacka I., Welsch K., Winkler M., Schneider H., Hofmann-Winkler H., et al. TMPRSS2 activates the human coronavirus 229E for cathepsin-independent host cell entry and is expressed in viral target cells in the respiratory epithelium. J. Virol. 2013;87:6150–6160. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03372-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beucher G., Blondot M.-L., Celle A., Pied N., Recordon-Pinson P., Esteves P., Faure M., Métifiot M., Lacomme S., Dacheaux D., et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission via apical syncytia release from primary bronchial epithelia and infectivity restriction in children epithelia. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.1105.1128.446159. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boson B., Legros V., Zhou B., Siret E., Mathieu C., Cosset F.-L., Lavillette D., Denolly S. The SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins modulate maturation and retention of the spike protein, allowing assembly of virus-like particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296:100111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.016175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boumaza A., Gay L., Mezouar S., Bestion E., Diallo A.B., Michel M., Desnues B., Raoult D., La Scola B., Halfon P., et al. Monocytes and macrophages, targets of SARS-CoV-2: the clue for Covid-19 immunoparalysis. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:395–406. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruxvoort K.J., Sy L.S., Qian L., Ackerson B.K., Luo Y., Lee G.S., Tian Y., Florea A., Aragones M., Tubert J.E., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA-1273 against delta, mu, and other emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;375:e068848. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchrieser J., Dufloo J., Hubert M., Monel B., Planas D., Rajah M.M., Planchais C., Porrot F., Guivel-Benhassine F., Van der Werf S., et al. Syncytia formation by SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. EMBO J. 2020;39:e106267. doi: 10.15252/embj.2020106267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussani R., Schneider E., Zentilin L., Collesi C., Ali H., Braga L., Volpe M.C., Colliva A., Zanconati F., Berlot G., et al. Persistence of viral RNA, pneumocyte syncytia and thrombosis are hallmarks of advanced COVID-19 pathology. EBioMedicine. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.103104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattin-Ortola J., Welch L., Maslen S.L., Skehel J.M., Papa G., James L.C., Munro S. Sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of SARS-CoV-2 Spike facilitate expression at the cell surface and syncytia formation. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.12.335562. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. SARS-CoV-2 Variant Classifications and Definitions.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fcases-updates%2Fvariant-surveillance%2Fvariant-info.html [Google Scholar]

- Cherian S., Potdar V., Jadhav S., Yadav P., Gupta N., Das M., Rakshit P., Singh S., Abraham P., Panda S., Team N. SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations, L452R, T478K, E484Q and P681R, in the Second Wave of COVID-19 in Maharashtra, India. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1542. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9071542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutard B., Valle C., de Lamballerie X., Canard B., Seidah N.G., Decroly E. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res. 2020;176:104742. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniloski Z., Jordan T.X., Ilmain J.K., Guo X., Bhabha G., tenOever B.R., Sanjana N.E. The Spike D614G mutation increases SARS-CoV-2 infection of multiple human cell types. Elife. 2021;10:e65365. doi: 10.7554/eLife.65365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle D.M., Kim-Schulze S., Huang H.-H., Beckmann N.D., Nirenberg S., Wang B., Lavin Y., Swartz T.H., Madduri D., Stock A., et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat. Med. 2020;26:1636–1643. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalera A., Gonzalez-Reiche A.S., Aslam S., Mena I., Laporte M., Pearl R.L., Fossati A., Rathnasinghe R., Alshammary H., van de Guchte A., et al. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern link to increased spike cleavage and virus transmission. Cell Host Microbe. 2022;30:373–387.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway S.E., Paul P., MacCannell D.R., Johansson M.A., Brooks J.T., MacNeil A., Slayton R.B., Tong S., Silk B.J., Armstrong G.L., et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 b. 1.1. 7 lineage”United States, december 29, 2020“ January 12. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:95–99. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowacka I., Bertram S., Müller M.A., Allen P., Soilleux E., Pfefferle S., Steffen I., Tsegaye T.S., He Y., Gnirss K., et al. Evidence that TMPRSS2 activates the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein for membrane fusion and reduces viral control by the humoral immune response. J. Virol. 2011;85:4122–4134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02232-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaney A.J., Starr T.N., Gilchuk P., Zost S.J., Binshtein E., Loes A.N., Hilton S.K., Huddleston J., Eguia R., Crawford K.H.D., et al. Complete mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain that escape antibody recognition. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:44–57.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjadj J., Yatim N., Barnabei L., Corneau A., Boussier J., Smith N., Péré H., Charbit B., Bondet V., Chenevier-Gobeaux C., et al. Impaired type I interferon activity and inflammatory responses in severe COVID-19 patients. Science. 2020;369:718–724. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Hofmann-Winkler H., Pahlmann S. Activation of Viruses by Host Proteases. Springer; 2018. Priming time: how cellular proteases arm coronavirus spike proteins; pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Pöhlmann S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol. Cell. 2020;78:779–784.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.-H., Nitsche A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojyo S., Uchida M., Tanaka K., Hasebe R., Tanaka Y., Murakami M., Hirano T. How COVID-19 induces cytokine storm with high mortality. Inflamm. Regen. 2020;40:37. doi: 10.1186/s41232-020-00146-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (N. Am. Ed.) 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Yang C., Xu X.-f., Xu W., Liu S.-w. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020;41:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41401-020-0485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L., Rodel H., Hwa S.-H., Cele S., Ganga Y., Tegally H., Bernstein M., Giandhari J., Team C.-K., Gosnell B.I., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell-to-cell spread occurs rapidly and is insensitive to antibody neutralization. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.1106.1101.446516. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.A., Xie X., Kalveram B., Lokugamage K.G., Muruato A., Zou J., Zhang X., Juelich T., Smith J.K., Zhang L., et al. Furin cleavage site is key to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.1108.1126.268854. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.A., Xie X., Bailey A.L., Kalveram B., Lokugamage K.G., Muruato A., Zou J., Zhang X., Juelich T., Smith J.K., et al. Loss of furin cleavage site attenuates SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nature. 2021;591:293–299. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03237-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim S.S.A., Karim Q.A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:2126–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki T., Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine-Weber H., Elzayat M.T., Hoffmann M., Pöhlmann S. Functional analysis of potential cleavage sites in the MERS-coronavirus spike protein. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:16597. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34859-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Liu J., Johnson B.A., Xia H., Ku Z., Schindewolf C., Widen S.G., An Z., Weaver S.C., Menachery V.D., et al. Delta spike P681R mutation enhances SARS-CoV-2 fitness over Alpha variant. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.12.456173. Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Bernal J., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., Stowe J., Tessier E., Groves N., Dabrera G., et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;385:585–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S., Nagata N., Shirato K., Kawase M., Takeda M., Taguchi F. Efficient activation of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein by the transmembrane protease TMPRSS2. J. Virol. 2010;84:12658–12664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum M., Czudnochowski N., Rosen L.E., Zepeda S.K., Bowen J.E., Walls A.C., Hauser K., Joshi A., Stewart C., Dillen J.R., et al. Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron immune evasion and receptor engagement. Science. 2022;375:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abn8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum M., Walls A.C., Sprouse K.R., Bowen J.E., Rosen L.E., Dang H.V., De Marco A., Franko N., Tilles S.W., Logue J., et al. Molecular basis of immune evasion by the Delta and Kappa SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;374:1621–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.abl8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J., HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajah M.M., Hubert M., Bishop E., Saunders N., Robinot R., Grzelak L., Planas D., Dufloo J., Gellenoncourt S., Bongers A., et al. SARS-CoV2 alpha, Beta and delta variants display enhanced spike-mediated syncytia formation. EMBO J. 2021;40:e108944. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021108944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlcochova P., Kemp S.A., Dhar M.S., Papa G., Meng B., Ferreira I.A.T.M., Datir R., Collier D.A., Albecka A., Singh S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 Delta variant replication and immune evasion. Nature. 2021;599:114–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03944-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murgolo N., Therien A.G., Howell B., Klein D., Koeplinger K., Lieberman L.A., Adam G.C., Flynn J., McKenna P., Swaminathan G., et al. SARS-CoV-2 tropism, entry, replication, and propagation: considerations for drug discovery and development. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009225. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeldt C.J., Cerikan B., Cortese M., Frankish J., Lee J.-Y., Plociennikowska A., Heigwer F., Prasad V., Joecks S., Burkart S.S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces a pro-inflammatory cytokine response through cGAS-STING and NF-κB. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:45. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02983-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles M.A., Gogesch P., Kronhart S., Ortega Iannazzo S., Kochs G., Waibler Z., Anzaghe M. Macrophages and dendritic cells are not the major source of pro-inflammatory cytokines upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:647824. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.647824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka C.K.V., Franco M.M., Gräf T., de Lorenzo Barcia C.A., de Ávila Mendonça R.N., de Sousa K.A.F., Neiva L.M.C., Fosenca V., Mendes A.V.A., de Aguiar R.S., et al. Genomic evidence of a Sars-Cov-2 reinfection case with E484K spike mutation in Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27:1522–1524. doi: 10.3201/eid2705.210191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg T., Ferguson N.M., Nash S.G., Webster H.H., Flaxman S., Andrews N., Hinsley W., Bernal J.L., Kall M., Bhatt S., et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399:1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva M.H.S., Guedes D.R.D., Docena C., Bezerra M.F., Dezordi F.Z., Machado L.C., Krokovsky L., Helvecio E., da Silva A.F., Vasconcelos L.R.S., et al. Multiple introductions followed by ongoing community spread of SARS-CoV-2 at one of the largest metropolitan areas of Northeast Brazil. Viruses. 2020;12:1414. doi: 10.3390/v12121414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazi I., Al-Qahtani A.A., Alhamlan F.S., Alothaid H., Matou-Nasri S., Sourvinos G., Vergadi E., Tsatsanis C. SARS-CoV-2/ACE2 interaction Suppresses IRAK-M expression and promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:683800. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.683800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa G., Mallery D.L., Albecka A., Welch L.G., Cattin-Ortolá J., Luptak J., Paul D., McMahon H.T., Goodfellow I.G., Carter A., et al. Furin cleavage of SARS-CoV-2 Spike promotes but is not essential for infection and cell-cell fusion. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009246. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra T., Meyer K., Geerling L., Isbell T.S., Hoft D.F., Brien J., Pinto A.K., Ray R.B., Ray R., Ray R.B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein promotes IL-6 trans-signaling by activation of angiotensin II receptor signaling in epithelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1009128. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock T.P., Goldhill D.H., Zhou J., Baillon L., Frise R., Swann O.C., Kugathasan R., Penn R., Brown J.C., Sanchez-David R.Y., et al. The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 2021;6:899–909. doi: 10.1038/s41564-021-00908-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock T.P., Sheppard C.M., Brown J.C., Goonawardane N., Zhou J., Whiteley M., Consortium P.V., de Silva T.I., Barclay W.S. The SARS-CoV-2 variants associated with infections in India, B. 1.617, show enhanced spike cleavage by furin. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.1105.1128.446163. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Planas D., Veyer D., Baidaliuk A., Staropoli I., Guivel-Benhassine F., Rajah M.M., Planchais C., Porrot F., Robillard N., Puech J., et al. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Alimonti J.B., Melito P.L., Fernando L., Ströher U., Jones S.M. Characterization of Zaire ebolavirus glycoprotein-specific monoclonal antibodies. Clin. Immunol. 2011;141:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan R., Sharma A., Verma M.K. Characterization of the second wave of COVID-19 in India. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.17.21255665. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S. How the Delta variant achieves its ultrafast spread. Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1038/d41586-41021-01986-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resende P.C., Bezerra J.o.F., Vasconcelos R., Arantes I., Appolinario L., Mendonça A.C., Paixao A.C., Rodrigues A.C.D., Silva T., Rocha A.S. Spike E484K mutation in the first SARS-CoV-2 reinfection case confirmed in Brazil, 2020. Virological. 2021;10 https://virological.org/t/spike-e484k-mutation-in-the-first-sars-cov-482-reinfection-case-confirmed-in-brazil-2020/2584 [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo J.P., Mishra A.P., Samal K.C. Triple mutant Bengal strain (B. 1.618) of coronavirus and the worst COVID outbreak in India. Biotica Research Today. 2021;3:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Saito A., Irie T., Suzuki R., Maemura T., Nasser H., Uriu K., Kosugi Y., Shirakawa K., Sadamasu K., Kimura I. SARS-CoV-2 spike P681R mutation, a hallmark of the Delta variant, enhances viral fusogenicity and pathogenicity. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.1106.1117.448820. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Cruz A., Mendes-Frias A., Oliveira A.I., Dias L., Matos A.R., Carvalho A., Capela C., Pedrosa J., Castro A.G., Silvestre R. Interleukin-6 is a Biomarker for the development of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 pneumonia. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:613422. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.613422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos J.C., Passos G.A. The high infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.1. 7 is associated with increased interaction force between Spike-ACE2 caused by the viral N501Y mutation. bioRxiv. 2021:424708. Preprint at. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Method. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S., Banu S., Singh P., Sowpati D.T., Mishra R.K. SARS-CoV-2 genomics: an Indian perspective on sequencing viral variants. J. Biosci. 2021;46:22. doi: 10.1007/s12038-021-00145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T., Bauler T.J., Malik-Kale P., Steele-Mortimer O. The phorbol 12-myristate-13-acetate differentiation protocol is critical to the interaction of THP-1 macrophages with Salmonella Typhimurium. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed A.M., Taha T.Y., Tabata T., Chen I.P., Ciling A., Khalid M.M., Sreekumar B., Chen P.Y., Hayashi J.M., Soczek K.M., et al. Rapid assessment of SARS-CoV-2-evolved variants using virus-like particles. Science. 2021;374:1626–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.abl6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegally H., Wilkinson E., Giovanetti M., Iranzadeh A., Fonseca V., Giandhari J., Doolabh D., Pillay S., San E.J., Msomi N., et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. medRxiv. 2020:20248640. Preprint at. [Google Scholar]

- Twohig K.A., Nyberg T., Zaidi A., Thelwall S., Sinnathamby M.A., Aliabadi S., Seaman S.R., Harris R.J., Hope R., Lopez-Bernal J., et al. Hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk for SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) compared with alpha (B.1.1.7) variants of concern: a cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E., Mishra S., Chand M., Barrett J.C., Johnson R., Geidelberg L., Hinsley W.R., Laydon D.J., Dabrera G., O’Toole Ã.i. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Lineage B. 1.1. 7 in England: Insights from linking epidemiological and genetic data. medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2020.12.30.20249034. Preprint at. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Ye L., Ye L., Li B., Gao B., Zeng Y., Kong L., Fang X., Zheng H., Wu Z., She Y. Up-regulation of IL-6 and TNF-alpha induced by SARS-coronavirus spike protein in murine macrophages via NF-kappaB pathway. Virus Res. 2007;128:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2022. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- Worldometer . 2021. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic Worldometer.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- Xia S., Lan Q., Su S., Wang X., Xu W., Liu Z., Zhu Y., Wang Q., Lu L., Jiang S. The role of furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein-mediated membrane fusion in the presence or absence of trypsin. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:92. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0184-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.-S., Shu T., Kang L., Wu D., Zhou X., Liao B.-W., Sun X.-L., Zhou X., Wang Y.-Y. Temporal profiling of plasma cytokines, chemokines and growth factors from mild, severe and fatal COVID-19 patients. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:100–103. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Liu S., Liu J., Zhang Z., Wan X., Huang B., Chen Y., Zhang Y. COVID-19: immunopathogenesis and Immunotherapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:128. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye G., Liu B., Li F. Cryo-EM structure of a SARS-CoV-2 omicron spike protein ectodomain. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28882-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng C., Evans J.P., King T., Zheng Y.-M., Oltz E.M., Whelan S.P.J., Saif L.J., Peeples M.E., Liu S.-L. SARS-CoV-2 spreads through cell-to-cell transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2111400119. e2111400119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]