Abstract

We have isolated bacterial strains capable of aerobic growth on ortho-substituted dichlorobiphenyls as sole carbon and energy sources. During growth on 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl and 2,4′-dichlorobiphenyl strain SK-4 produced stoichiometric amounts of 2-chlorobenzoate and 4-chlorobenzoate, respectively. Chlorobenzoates were not produced when strain SK-3 was grown on 2,4′-dichlorobiphenyl.

Although bioremediation is an effective cleanup strategy for many contaminants, efforts to engineer bioremediation systems for polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-contaminated soils or sludges have been largely ineffective. One of the more promising PCB bioremediation strategies is sequential anaerobic-aerobic treatment (1). Under anoxic conditions, highly chlorinated congeners can often be reductively dechlorinated (8, 25), resulting in congeners that can potentially be degraded by aerobic bacteria. The lightly chlorinated congeners (one to five chlorines) remaining after reductive dechlorination can be either utilized as an aerobic growth substrate (12, 16) or cometabolically degraded in the presence of biphenyl (9, 14).

With few exceptions (5, 10), anaerobic PCB dechlorination rarely occurs at the ortho positions and generally results in accumulation of ortho- or ortho- and para-substituted congeners (19, 21, 27, 28). Interestingly, ortho substitution of a PCB also greatly reduces aerobic biodegradability (4, 13). As reported by Furukawa (11), PCB isomers with two ortho chlorines, such as 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl (2,2′-CB) or 2,6-CB, are rarely susceptible to aerobic cometabolic degradation. As a consequence, limited aerobic degradation of ortho-substituted congeners is a weak link in the development of effective anaerobic-aerobic PCB bioremediation strategies. Possible accumulation of ortho-substituted congeners such as 2,2′-CB may also have ecological and human health implications (7, 22).

Although numerous reports have shown that monochlorobiphenyls can serve as growth substrates (2, 3, 6, 17, 18, 23), reports of unambiguous growth by natural isolates on CBs has been demonstrated only for Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (20). To the best of our knowledge, growth on a di-ortho-substituted CB has not been demonstrated. Here we report the isolation and characterization of unique bacteria capable of using as growth substrates ortho-substituted CB congeners with chlorine substituents on both rings, including an isolate able to utilize 2,2′-CB.

The CB-degrading bacteria were isolated from PCB-contaminated, tertiary lagoon sludge as previously described (16). One isolate (SK-3) was selected based on its ability to grow on both 4-chlorobiphenyl and 4-chlorobenzoic acid (4-CBA) (16). Another isolate (SK-4) was ultimately enriched and selected based on an ability to grow on 2,2′-CB.

Cell growth and biotransformation of CBs were studied in Balch tubes sealed with Teflon-coated stoppers as reported previously (16). Experiments were done in a mineral salts medium (16) which was amended with 5 or 10 μl of a solution of a single PCB congener dissolved in heptamethylnonane (HMN), a nondegradable carrier, to provide an initial concentration of 50 to 100 ppm. For CBs and other compounds mentioned below which have limited aqueous solubility, the concentrations given represent the total mass in both the aqueous and HMN phases, divided by the aqueous volume. Congeners (minimum 99% purity) were purchased from Ultra Scientific (North Kinston, R.I.) and AccuStandard (New Haven, Conn.). Cells used as the inoculum were previously grown on 2 mM benzoate, and biphenyl dioxygenase was therefore not induced by previous growth on biphenyl. Cell growth was measured by a direct counting method after acridine orange staining (15). In time course experiments, two replicate tubes were sacrificed at each time point by adding 10 ml of hexane and mixing for 6 h on a tube rotator. CB disappearance and CBA production were measured as described previously (16). The concentration of chloride was determined using a Cole-Palmer 27502-12 chloride ion-specific electrode.

SK-4 was a nonmotile, aerobic, gram-negative rod that was cytochrome oxidase and catalase positive (24, 26). The results of phenotypic API E testing (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.) for the identification of gram-negative bacteria suggested a strain of Alcaligenes xylos or a Pseudomonas species. The results of fatty acid analysis using high-resolution gas chromatography conducted by Microbial ID Inc. (Newark, Del.) suggested Alcaligenes eutrophus with a very high similarity score of 0.663. Although a definitive identification awaits phylogenetic analysis, we have tentatively identified the bacterium as Alcaligenes sp. strain SK-4. This isolate was able to grow on biphenyl, benzoate, chloroacetate, phenol, all monochlorobiphenyls, and CBs (2,2′-CB and 2,4′-CB) as sole carbon and energy sources. However, SK-4 failed to grow on naphthalene, all of the CBAs tested (2-, 3-, 4-, 2,3-, and 3,4-CBA), and the other CBs and trichlorobiphenyls tested (2,3-, 3,4-, 2,5-, 3,3′-, 3,5-, 4,4′-, and 2,3′-CB and 2,2′,5-, 2,2′,3-, and 2′,3,4-trichlorobiphenyl). All of the compounds in these growth studies were presented at a concentration of 100 ppm, with the exception of CBAs; for which 2- to 3-mM concentrations were used.

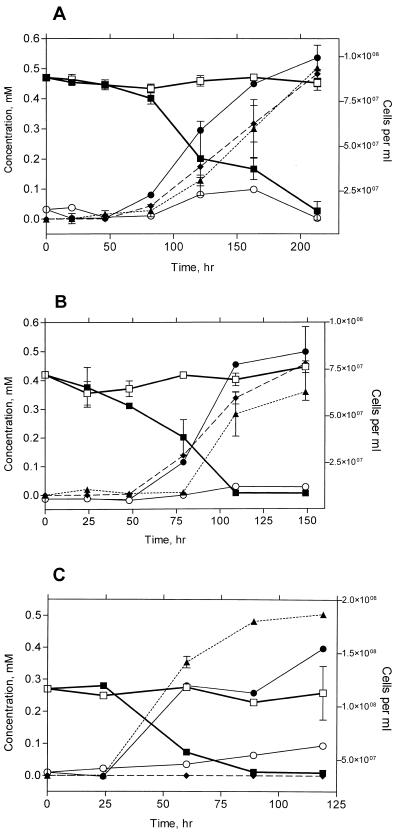

During SK-4's growth on 0.47 mM 2,2′-CB as a sole source of carbon and energy, cell numbers increased 10-fold during a 220-h incubation with an approximate doubling time of 37 h (estimated from t = 46 to 163 h) (Fig. 1A). 2,2′-CB was completely transformed into 2-CBA with release of one chloride per 2,2′-CB molecule transformed. No significant growth occurred in cultures lacking 2,2′-CB, and controls lacking cells did not show any transformation of 2,2′-CB. 2-CBA was not further degraded by strain SK-4.

FIG. 1.

Transformation of 2,2′-CB by strain SK-4 (A), 2,4′-CB by strain SK-4 (B), and 2,4′-CB by strain SK-3 (C) with accompanying data for cell growth, chloride release, and production of CBAs. CB concentrations are shown for bottles containing a cell inoculum (■) and control bottles lacking cells (□). CBA concentrations (⧫) represent 2-CBA in panel A and 4-CBA in panel B. Cell growth is illustrated for bottles containing CB (●) and for controls (○) containing the HMN carrier but lacking CB. Chloride = ▴. All data represent the mean of two replicate bottles, and error bars represent 1 standard deviation. Lack of error bars for analytical data indicates that the error bars were smaller than the symbol. Error bars for cell counts were eliminated to improve clarity. The typical standard deviations observed for cell counts were within 20 to 40% of the mean values shown.

SK-4 was able to grow more rapidly on 0.42 mM 2,4′-CB, with an approximate doubling time of 17 h (estimated from t = 48 to 109 h) (Fig. 1B). Similar to the degradation of 2,2′-CB, growth on 2,4′-CB resulted in the stoichiometric accumulation of a CBA and the production of chloride. The CBA produced from 2,4′-CB was identified as 4-CBA, suggesting that SK-4 utilized only the ortho-chlorinated rings of 2,2′-CB or 2,4′-CB. No growth occurred in controls lacking 2,4′-CB, and the CB was not degraded in incubations lacking cells. SK-4 growth is sustainable on these CBs, and we have maintained this isolate on 2,2′-CB as the sole carbon source for over 1 year using monthly 10% transfers to fresh medium.

Isolates able to grow on monochlorobiphenyls as a sole carbon and energy source usually metabolize the nonchlorinated ring and produce a CBA or other chlorinated compound as a product (3, 12, 17, 18). However, we recently described a new isolate, SK-3, which is able to grow on both 4-CBA and 4-CB (16). Growth on the latter compound as a sole carbon source resulted in stoichiometric chloride release and did not result in the production of any CBAs. Here we report that SK-3 is also able to grow on 2,4′-CB. However, SK-3 was unable to grow on any of the other congeners tested (2,3-, 3,4-, 2,2′-, 3,5-, 3,3′-, 4,4′-, 2,5-, and 2,3′-CB and 2,2′,3- and 2′,3,4-trichlorobiphenyl), with the exception of monochlorobiphenyls. Based on API E tests and fatty acid analysis, we have tentatively identified this bacterium as Burkholderia sp. strain SK-3.

SK-3 was also able to use 2,4′-CB as a growth substrate, as depicted in Fig. 1C. The doubling time of SK-3 on 0.27 mM 2,4′-CB was approximately 43 h (estimated from t = 24 to 119 h). Significantly, no production of CBAs (neither 2-CBA nor 4-CBA) was detected during the growth of SK-3 on 2,4′-CB. In contrast to degradation of 2,4′-CB by SK-4, the extent of chloride production (0.49 mM) implied that both rings of 2,4′-CB were dechlorinated and, possibly, mineralized by SK-3. Growth and degradation ability are sustainable, and we have maintained this isolate on 2,4′-CB as a sole carbon source for over 1 year.

Contrary to what has been previously observed for most chlorobiphenyl utilizers, nonchlorinated rings were not required for growth by SK-3 or SK-4. Although Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 has been shown by Potrawfke et al. to be capable of degrading 2,4′-CB (20), the ability to utilize a di-ortho-substituted CB such as 2,2′-CB is quite unique and previously unreported.

SK-3 and SK-4 show chlorobiphenyl degradation patterns substantially dissimilar from those reported by Potrawfke et al. for strain LB400 (20). LB400, for example, was able to grow poorly, if at all, on 2-CB, whereas both SK-3 and SK-4 grow well on this substrate (data not shown). LB400 produced equimolar accumulations of 4-CBA when grown on 4-CB, whereas SK-3 liberated stoichiometric amounts of chloride and did not produce 4-CBA when grown on the same substrate (16). More interestingly, growth by SK-3 on 2,4′-CB did not produce a CBA as a product whereas LB400 incompletely metabolized this substrate and produced a stoichiometric amount of 4-CBA.

The isolation of these novel microorganisms with the ability to grow on ortho-substituted CBs could be an important step in studying the specificity of aromatic oxygenases, constructing new hybrids with unique abilities, and developing effective PCB biodegradation strategies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramowicz D A. Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of PCBs: a review. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1990;10:241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed M, Focht D D. Degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by two species of Achromobacter. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:47–52. doi: 10.1139/m73-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barton M R, Crawford R L. Novel biotransformations of 4-chlorobiphenyl by a Pseudomonas sp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:594–595. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.2.594-595.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedard D L, Haberl M L, May R J, Brennan M J. Evidence for novel mechanisms of polychlorinated biphenyl metabolism in Alcalingenes eutrophus H850. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1103–1112. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.1103-1112.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkaw M, Sowers K R, May H D. Anaerobic ortho dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls by estuarine sediments from Baltimore Harbor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2534–2539. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2534-2539.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bevinakatti B G, Ninnekar H Z. Biodegradation of 4-chlorobiphenyl by Micrococcus species. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;9:607–608. doi: 10.1007/BF00386308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridgham S D. Chronic effects of 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl on reproduction, mortality, growth, and respiration of Daphnia pulicaria. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1988;17:731–740. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown J F, Jr, Wagner R E, Feng H, Bedard D L, Brennan M J, Carnahan J C, May R J. Environmental dechlorination of PCBs. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1987;6:579–593. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commandeur L C M, May R, Mokross H, Bedard D L, Reineke W, Govers H A J, Parsons J R. Aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Alcaligenes sp. JB1: metabolites and enzymes. Biodegradation. 1996;7:435–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00115290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cutter L, Sowers K R, May H D. Microbial dechlorination of 2,3,5,6-tetrachlorobiphenyl under anaerobic conditions in the absence of soil or sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2966–2969. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2966-2969.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furukawa K. Microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. In: Chakrabarty A M, editor. Biodegradation and detoxification of environmental pollutants. Boca Raton, Fa: CRC Press, Inc.; 1982. pp. 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furukawa K, Chakrabarty A M. Involvement of plasmids in total degradation of chlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:619–626. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.3.619-626.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa K, Tonomura K, Kamibayashi A. Effect of chlorine substitution on the biodegradability of polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:223–227. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.223-227.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez B S, Arensdorf J J, Focht D D. Catabolic characteristics of biphenyl-utilizing isolates which cometabolize PCBs. Biodegradation. 1995;6:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kepner J, Raymond L, Pratt J R. Use of flurorochromes for direct enumeration of total bacteria in environmental samples: past and present. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:603–615. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.4.603-615.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim S, Picardal F. A novel bacterium that utilizes monochlorobiphenyls and 4-chlorobenzoate as growth substrates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;185:225–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi K, Katayama-Hirayama K, Tobita S. Isolation and characterization of microorganisms that degrade 4-chlorobiphenyl to 4-chlorobenzoic acid. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1996;42:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massé R, Messier F, Péloquin L, Ayotte C, Sylvestre M. Microbial biodegradation of 4-chlorobiphenyl, a model compound of chlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:947–951. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.5.947-951.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris P J, Mohn W W, Quensen J F I, Tiedje J M, Boyd S A. Establishment of a polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading enrichment culture with predominantly meta dechlorination. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3088–3094. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.3088-3094.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Potrawfke T, Löhnert T-H, Timmis K N, Wittich R-M. Mineralization of low-chlorinated biphenyls by Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 and by a two-membered consortium upon directed interspecies transfer of chlorocatechol pathway genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;50:440–446. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quensen J F, III, Boyd S A, Tiedje J M. Dechlorination of four commercial polychlorinated biphenyl mixtures (Aroclors) by anaerobic microorganisms from sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2360–2369. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2360-2369.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shain W, Bush B, Seegal R. Neurotoxicology of polychlorinated biphenyls: structure-activity relationship of different congeners. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1991;111:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(91)90131-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shields M S, Hooper S W, Sayler G S. Plasmid-mediated mineralization of 4-chlorobiphenyl. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:882–889. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.882-889.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarrand J J, Gröschel D H M. Rapid, modified oxidase test for oxidase-variable bacterial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;16:772–774. doi: 10.1128/jcm.16.4.772-774.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tiedje J M, Quensen III J F, Chee-Sanford J, Schimel J, Boyd S A. Microbial reductive dechlorination of PCBs. Biodegradation. 1993;4:231–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00695971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whittenbury R. Hydrogen peroxide formation and catalase activity in the lactic acid bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1964;35:13–26. doi: 10.1099/00221287-35-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye D, Quensen J F, III, Tiedje J M, Boyd S A. Anaerobic dechlorination of polychlorobiphenyls (Arochlor 1242) by pasteurized and ethanol-treated microorganisms from sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1110–1114. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1110-1114.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye D, Quensen J F, III, Tiedje J M, Boyd S A. Evidence for para dechlorination of polychlorobiphenyls by methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2166–2171. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2166-2171.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]