Abstract

Strain IMB-1, an aerobic methylotrophic member of the alpha subgroup of the Proteobacteria, can grow with methyl bromide as a sole carbon and energy source. A single cmu gene cluster was identified in IMB-1 that contained six open reading frames: cmuC, cmuA, orf146, paaE, hutI, and partial metF. CmuA from IMB-1 has high sequence homology to the methyltransferase CmuA from Methylobacterium chloromethanicum and Hyphomicrobium chloromethanicum and contains a C-terminal corrinoid-binding motif and an N-terminal methyltransferase motif. However, cmuB, identified in M. chloromethanicum and H. chloromethanicum, was not detected in IMB-1.

Methyl bromide (MeBr) is a fumigant used in the cultivation of soft fruits, vegetables, and flowers. Use of MeBr as a pesticide increases the yield and quality of crops without leaving behind toxic residues characteristic of more complex organopesticides. The majority of anthropogenic MeBr is produced in the United States, where 80% of it is used in fumigation treatments (23). The annual global flux of MeBr into the atmosphere from agricultural fumigation is approximately 16 to 48 Gg year−1 (13). Generally, bacterial soil sinks have been overlooked when global uptake rates have been estimated, simply because there is insufficient data available. The emissions of methyl chloride (MeCl) and MeBr into the atmosphere from natural and anthropogenic sources cause ozone depletion. MeBr is the main source in the atmosphere of bromide ions, which are 50 to 60 times more effective than chloride ions in converting ozone to oxygen. The reactions of chloride and bromide ions with stratospheric ozone have contributed to 20 to 25% of the Antarctic ozone hole (21).

Natural sources of MeBr are biomass burning, salt marshes, higher plants, phytoplankton, seaweed, fungi, and wetlands (9, 16, 26, 28, 41). In addition to its oxidation by tropospheric OH radicals (19), other biogeochemical sinks for MeBr include its dissolution from the atmosphere into the oceans, where it is destroyed by chemical and/or biological processes (10, 15, 44), and its consumption by bacteria in soils (12, 33, 34). Methyl halide-oxidizing bacteria have been isolated from soils (4, 7, 20), seawater (10), and forest leaf litter (6).

The facultative methylotroph strain IMB-1 was isolated from fumigated soil and is a member of the alpha subgroup of the Proteobacteria, within the genus Aminobacter. Phylogenetic analysis shows IMB-1 to cluster with the MeCl and MeBr utilizer, strain CC495, isolated from forest leaf litter (6). IMB-1 grows on methyl halides, methylated amines, and non-C1 compounds such as glucose and pyruvate (4), but no growth or oxidation was observed with methyl fluoride (MeF), methane, propyl iodide, dibromomethane, dichloromethane, or difluoromethane (4, 20, 32).

Bacteria that utilize MeCl as the sole source of carbon have also been isolated (7): Hyphomicrobium chloromethanicum CM2T and Methylobacterium chloromethanicum CM4T (18). Studies exploring the mechanism of MeCl metabolism in M. chloromethanicum CM4 have recently suggested a pathway for MeCl utilization (39, 40). It was shown that two polypeptides, of 67 and 35 kDa, were induced during growth on MeCl (40). MeCl-grown cells were also capable of dehalogenating MeBr and methyl iodide but not dichloromethane or chloroethane. This suggested that the enzyme(s) responsible for MeCl degradation was specific for monohalomethanes. No growth was observed with MeBr, presumably due to the greater toxicity of this compound. Transposon mutagenesis was used to create mutants that could not grow on MeCl. Genes containing the transposon insertion were then cloned and sequenced, and this information was used to develop biochemical assays. A pathway for MeCl degradation was then suggested that represents a novel catabolic pathway for aerobic methylotrophs (39).

The first step of this pathway involves CmuA, a 67-kDa polypeptide, which has a methyltransferase domain and a corrinoid-binding domain. The methyltransferase domain transfers the methyl group of MeCl to the Co atom of the enzyme-bound corrinoid group (methyltransferase I activity). A second polypeptide, CmuB, then transfers the methyl group onto tetrahydrofolate (H4F), forming methyl-H4F (methyltransferase II activity). This folate-linked methyl group is then progressively oxidized to formate and then CO2 to provide reducing equivalents for biosynthesis. Carbon assimilation presumably occurs at the level of methylene H4F, which can feed directly into the serine cycle. Four genes, cmuA, cmuB, cmuC, and purU, were shown to be essential for growth on MeCl but not on other C1 substrates. More recently, molecular studies of H. chloromethanicum CM2 have also identified the cmu genes essential for growth on MeCl (17).

The aim of this study was to identify and sequence the IMB-1 genes involved in MeBr utilization. An insight into substrate binding and structure of the proteins from IMB-1 was achieved by aligning the IMB-1 sequence with sequences of previously characterized polypeptides from MeCl utilizers.

Growth media.

IMB-1 was routinely cultured on 50 ml of ammonium nitrate mineral salts medium (42) at 30°C. Growth on MeBr (0.2%, vol/vol) was achieved in crimp-sealed 126-ml serum vials by pulsed additions of filter-sterilized gas in order to avoid toxicity associated with high initial concentrations of MeBr.

Construction of DNA libraries from H. chloromethanicum CM2.

DNA was extracted from strain IMB-1 as previously described (22). Genomic libraries were constructed by cloning DNA from IMB-1 into pBluescript II K/S digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme. Fragments suitable for cloning were identified by probing Southern blots of IMB-1 DNA with radioactively labeled probes for cmuA and cmuB from H. chloromethanicum CM2 and M. chloromethanicum CM4 by methods described by Sambrook et al. (29). Southern blots were hybridized at 65°C and washed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) at 60°C (high stringency) or at room temperature (low stringency) for 1 h.

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNA sequencing was performed by cycle sequencing with the Dye Terminator Kit (PE Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom), and the DNA was analyzed with a model 373A automated DNA sequencing system (PE Applied Biosystems). DNA sequences and derived amino acid sequences were analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) Wisconsin Package, version 8.0.1-Unix. Similarity searches were performed with the gapped BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) program (1) against public protein and gene databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Identification of methyltransferase genes in strain IMB-1.

Hybridization of cmuA from M. chloromethanicum CM4 and H. chloromethanicum CM2 to IMB-1 genomic DNA indicated that IMB-1 contained genes with homology to cmuA (data not shown). The Southern blot was also probed with cmuB from M. chloromethanicum CM4 and H. chloromethanicum CM2. However, even at low stringency, no hybridization was seen. This suggested that a gene(s) with homology to cmuB from M. chloromethanicum CM4 or H. chloromethanicum CM2 was not present in IMB-1.

Cloning the methyltransferase gene cmuA from strain IMB-1.

In order to clone cmuA from IMB-1, a partial library was made with restriction enzyme (BamHI)-digested fragments of between 5.5 and 6.5 kb, identified in probing experiments with cmuA probes. These were ligated into pBluescript II K/S to create a library of 500 recombinant clones. Hybridization with a 750-bp cmuA fragment from IMB-1, generated by PCR using primers designed from H. chloromethanicum and M. chloromethanicum cmuA sequences, identified eight identical clones containing a 6.4-kb BamHI fragment of IMB-1 chromosomal DNA (pIMB6) (Fig. 1).

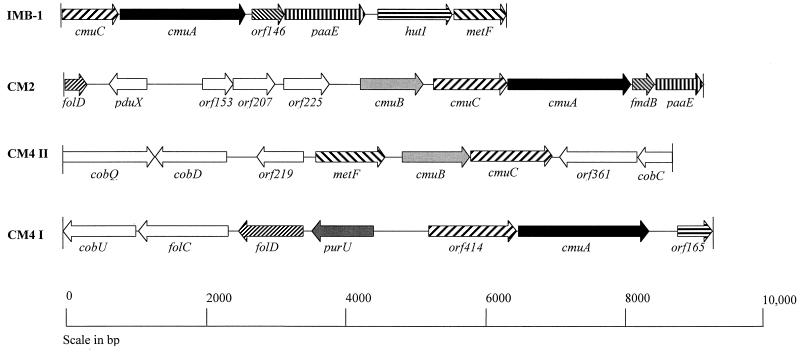

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the methyltransferase gene clusters from IMB-1, H. chloromethanicum CM2, and M. chloromethanicum CM4. The orientation and position of genes are shown. Genes with homology to each other have the same shading pattern. Other ORFs are shown as open arrows. The IMB-1 cluster is the 6.4-kb BamHI fragment cloned and sequenced in this study.

Sequence analysis of the IMB-1 methyltransferase gene cluster.

The sequence of the 6.4-kb BamHI fragment of IMB-1 revealed a cluster of putative methyl halide utilization genes (Fig. 1). The open reading frames (ORFs) from IMB-1 were matched to proteins in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. The guanine-plus-cytosine content of the cloned DNA from strain IMB-1 is 61.5 mol%, which is similar to that of the genus Aminobacter (62 to 64 mol%) (38), within which IMB-1 groups by 16S rRNA sequence analysis. It appears that IMB-1 has one methyltransferase gene cluster similar to the methyltransferase gene cluster of H. chloromethanicum CM2 (Fig. 1), whereas methyltransferase genes involved in MeCl metabolism are located on two clusters in M. chloromethanicum CM4 (39) (Fig. 1). In IMB-1, the arrangement of genes in the methyltransferase cluster is cmuC, cmuA, orf146, and paaE. This is similar to the arrangement of the corresponding genes in H. chloromethanicum CM2 (Fig. 1).

When IMB-1 is grown on MeBr, three specific polypeptides of 28 kDa, 32 kDa (of equal intensity), and 67 kDa (less intense) are induced (results not shown). The 67-kDa polypeptide is similar in size to the methyltransferase/corrinoid CmuA found in M. chloromethanicum CM4, H. chloromethanicum CM2, and strain CC495. Two of these polypeptides correspond to the predicted molecular mass of the derived polypeptides from cmuA (62 kDa) and cmuC (28 kDa).

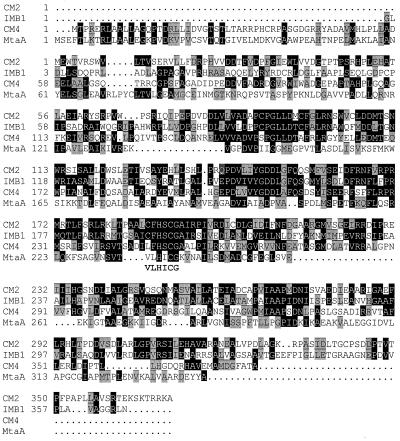

Alignments of proteins from IMB-1 with structurally characterized proteins allow for speculation on the structure, function, and potential binding site residues within the proteins. CmuC from IMB-1 has high homology to CmuC from H. chloromethanicum CM2 (40%) and M. chloromethanicum CM4 (36%) and also to MtaA, a methyltransferase protein from Methanosarcina barkeri (25%) (Fig. 2) (14, 39). MtaA is an isoenzyme that can transfer a methyl group from methyl cob(III)alamin, yielding methyl coenzyme M (11). MtaA binds zinc or cobalt to activate coenzyme M for methyl group attack from methyl cob(III)alamin (30, 31). Conserved histidine and cysteine residues for zinc or cobalt binding are also present in CmuC (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is possible that the putative methyltransferase CmuC also has methyltransferase II activity, like MtaA, and transfers the methyl group from CmuA methyl cob(III)alamin to H4F, forming methyl-H4F. A CmuB homolog was not detected in IMB-1, which suggests that CmuC operates as the CmuB methylcobalamin:H4F methyltransferase does in M. chloromethanicum CM4 or alternatively that the cmuB gene in IMB-1 has low homology to cmuB from H. chloromethanicum CM2 and M. chloromethanicum CM4 (35), and was therefore not detected by Southern blot hybridization.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of CmuC from IMB-1, CmuC from H. chloromethanicum CM2, CmuC from M. chloromethanicum CM4, and MtaA from M. barkeri. CmuC from IMB-1 has been aligned with CmuC from H. chloromethanicum CM2 (AF281259), CmuC from M. chloromethanicum CM4 (AJ011316), and MtaA from M. barkeri. Similar residues are shaded in gray; identical residues are in black boxes. The putative zinc-binding motif identified in MtbA from M. barkeri is shown in boldface type below the alignment (14).

CmuA from IMB-1 has a high degree of homology to CmuA from M. chloromethanicum (78%) and H. chloromethanicum (79%) and has two domains with the potential for methyl transfer and corrinoid binding. CmuA from IMB-1 is smaller (62 kDa) than CmuA from H. chloromethanicum CM2 (67 kDa) and M. chloromethanicum CM4 (67 kDa) and shows less homology in the corrinoid binding region. In the C-terminal (corrinoid binding) region of CmuA from IMB-1, the histidine residue in MetH corresponds to a glutamine (Q504), as is the case in H. chloromethanicum and M. chloromethanicum, and the only other conserved residues are three glycines (G507-G529-G530). This suggests that the binding of the corrin ring is weaker (18, 39).

Orf146 from IMB-1 shows 29% homology over 70 amino acids to the UvrA-ABC transporter from Streptomyces coelicolor (25) (Oliver et al., unpublished European Molecular Biology Laboratory accession number T35244). Orf146 has significant homology (50%) to the small ORF also between CmuA and a putative reductase from H. chloromethanicum CM2.

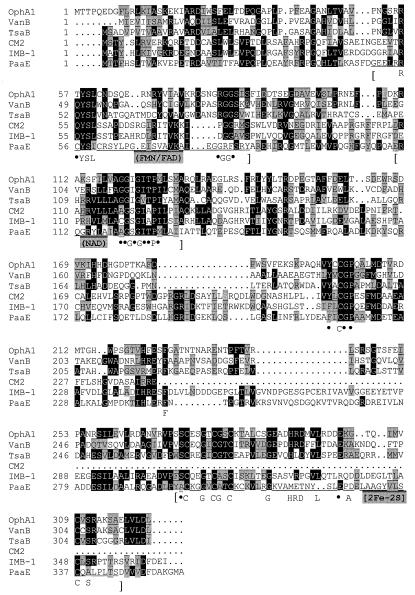

A large ORF (1,094 bp) encodes a homolog of PaaE, which has significant homology to a family of oxidoreductase proteins. The highest matches were PaaE from Escherichia coli (30% homology), which is involved in phenylacetic acid degradation (8), and VanB from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 (28%), which is a vanillate O-demethylase oxidoreductase (24). The putative reductases, PaaE homologs, from strain IMB-1 and H. chloromethanicum CM2 have significant homology to each other (50%). However, the C-terminal region of paaE from H. chloromethanicum CM2 has not been cloned. These putative reductases have significant homology to the class 1A dioxygenase family, in which the N terminus reveals a flavin mononucleotide/flavin adenine dinucleotide (FMN/FAD) binding site and there is an NAD binding domain in the center and a plant-type ferredoxin [2Fe-2S] domain in the C terminus (2, 3) (Fig. 3). The best-studied dioxygenase reductase is OphA1 from Burkholderia cepacia (previously known as Pseudomonas cepacia), which is involved in phthalate degradation. The structure of this reductase is known, and FMN/FAD, NAD, and [2Fe-2S] binding sites and other important conserved residues have been determined (5). In this reductase family, the conserved consensus for binding of the riboflavin-isoalloxazine ring is R-x-YSL and x-R-G-G-S (where x is either G or S). The arginine in x-R-G-G-S is required for the binding of the FMN phosphate group, specifically binding FMN rather than FAD. In IMB-1 and H. chloromethanicum CM2, the residues within the conserved sequence (R-x-YSL) are present. However, the arginine residue in the x-R-G-G-S motif, specifically required for FMN binding, is not present, suggesting that the cofactor FAD is required. An NADH or NADPH binding motif (G-x-G-x-x-P) is present in IMB-1 and H. chloromethanicum CM2. Finally, plant-type ferredoxin [2Fe-2S] residues (C-x4-C-x2-C-xn-C) are found in the C terminus of the putative reductase from IMB-1, and other residues conserved within the dioxygenase reductase family are also found in the reductase sequence of IMB-1 (Fig. 3) (3, 27, 37). It is also possible that the putative reductase (PaaE) from H. chloromethanicum CM2 contains the [2Fe-2S] clusters.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the putative reductase (PaaE) proteins from IMB-1 and H. chloromethanicum CM2 with related reductase sequences. The putative reductase (Orf364) from IMB-1 and the partial putative reductase (Orf 240) from H. chloromethanicum CM2 have been aligned with OphA1 (phthalate dioxygenase reductase) from B. cepacia (AF095748), VanB from Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 (Y11521), TsaB (toluenesulfonate methyl-monooxygenase reductase) from Comamonas testosteroni (U32622), and PaaE from E. coli (X97452). Similar residues are shaded in gray; identical residues are in black boxes. The FMN/FAD, NAD, and [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin conserved binding sites are indicated underneath the sequence, and other conserved residues are indicated by bullets (●) (3, 5).

The HutI homolog has homology to an imidazolonepropionase from Sinorhizobium meliloti that belongs to the HutI family of proteins involved in histidine degradation (43). The N-terminal domain of the HutI homolog from IMB-1 has 35% homology and 55% similarity to Orf165 (encoded by a partially cloned gene) from M. chloromethanicum CM4. However, a link between this protein and the dehalogenation of methyl halides is not known, and it may be that the imidazole ring found in the nucleotide loop of the cobalamin structure needs to be degraded during the dehalogenation reaction.

Previously it has been proposed that methyl-H4F, produced from MeCl by methyltransferase activity, is then reduced by the methylene-H4F reductase (MetF), identified in M. chloromethanicum CM4 (39). A putative MetF has also been identified in strain IMB-1, which has homology with MetF from M. chloromethanicum CM4 (33%) and MetF from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (23%) (36). Methylene-H4F would be a key intermediate in the degradation of halomethanes by M. chloromethanicum CM4 and IMB-1, as this substrate can be either oxidized to formate or converted by serine transhydroxymethylase and assimilated into cell biomass via the serine cycle.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of the cmu gene cluster from strain IMB-1 has been deposited in GenBank (accession number AF281260).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support provided by the Natural Environment Research Council (GR9/2192) and for studentships to C. Woodall and K. Warner and INTAS grant 94–3122.

We thank Don Kelly (University of Warwick) for useful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J H, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batie C J, Kamin H. The relation of pH and oxidation-reduction potential to the association state of the ferredoxin:ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase complex. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:7756–7763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang H K, Zylstra G J. Novel organization of the genes for phthalate degradation from Burkholderia cepacia DB01. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6529–6537. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6529-6537.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connell Hancock T L, Costello A M, Lidstrom M E, Oremland R S. Strain IMB-1, a novel bacterium for the removal of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2899–2905. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2899-2905.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Correll C C, Batie C J, Ballou D P, Ludwig M L. Phthalate dioxygenase reductase—a modular structure for electron-transfer from pyridine-nucleotides to [2Fe-2S] Science. 1992;258:1604–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.1280857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter C, Hamilton J T G, McRoberts W C, Kulakov L, Larkin M J, Harper D B. Halomethane:bisulfide/halide ion methyltransferase, an unusual corrinoid enzyme of environmental significance isolated from an aerobic methylotroph using chloromethane as the sole carbon source. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4301–4312. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4301-4312.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doronina N V, Sokolov A P, Trotsenko Y A. Isolation and initial characterization of aerobic chloromethane-utilizing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;142:179–183. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrandez A, Garcia J L, Diaz E. Genetic characterization and expression in heterologous hosts of the 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)propionate catabolic pathway of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2573–2581. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2573-2581.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin K D, North W J, Lidstrom M E. Production of bromoform and dibromomethane by giant kelp: factors affecting release and comparison to anthropogenic bromine sources. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1725–1734. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin K D, Schaefer J K, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of dibromomethane and methyl bromide in natural waters and enrichment cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4629–4636. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4629-4636.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harms U, Thauer R K. Methylcobalamin:coenzyme M methyltransferase isoenzymes MtaA and MtbA from Methanosarcina barkeri. Cloning, sequencing and differential transcription of the encoding genes, and functional overexpression of the mtaA gene in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235:653–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hines M E, Crill P M, Varner R K, Talbot R W, Shorter J H, Kolb C E, Harriss R C. Rapid consumption of low concentrations of methyl bromide by soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1864–1870. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1864-1870.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurylo M J, Rodriguez J M, Andreae M O, Atlas E L, Blake D R, Butler J H, Lal S, Lary D J, Midgley P M, Montzka S A, Novelli P C, Reeves C E, Simmonds P G, Steele L P, Sturges W T, Weiss R F, Yokouchi Y. Short-lived ozone-related compounds. In: Ennis C A, editor. Scientific assessment of ozone depletion: 1998. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization; 1999. pp. 2.1–2.56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeClerc G M, Grahame D A. Methylcobamide:coenzyme M methyltransferase isoenzymes from Methanosarcina barkeri. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18725–18731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lobert J M, Butler J H, Montzka S A, Geller L S, Myers R C, Elkins J W. A net sink for atmospheric CH3Br in the east Pacific Ocean. Science. 1995;267:1002–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5200.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mano S, Andreae M O. Emission of methyl bromide from biomass burning. Science. 1994;263:1255–1257. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5151.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAnulla C, Woodall C A, McDonald I R, Studer A, Vuilleumier S, Leisinger T, Murrell J C. Chloromethane utilization gene cluster from Hyphomicrobium chloromethanicum strain CM2T and development of functional gene probes to detect halomethane-degrading bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:307–316. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.307-316.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonald I R, Doronina N V, Trotsenko Y A, McAnulla C, Murrell J C. Hyphomicrobium chloromethanicum sp. nov. and Methylobacterium chloromethanicum sp. nov., chloromethane-utilising bacteria isolated from a polluted environment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001;51:119–122. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-1-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellouki A, Taludar R K, Schmoltner A, Gierczak T, Mills M J, Solomon S, Ravishankara A R. Atmospheric lifetimes and ozone depletion potentials of methyl bromide (CH3Br) and dibromomethane (CH2Br2) Geophys Res Lett. 1992;19:2059–2062. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller L G, Connell T L, Guidetti J R, Oremland R S. Bacterial oxidation of methyl bromide in fumigated agricultural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4346–4354. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4346-4354.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller M. Methyl bromide and the environment. In: Bell C H, Price N, Chakrabarti B, editors. The methyl bromide issue. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. pp. 91–148. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oakley C J, Murrell J C. nifH genes in obligate methane oxidising bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;49:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price N. Methyl bromide in perspective. In: Bell C H, Price N, Chakrabarti B, editors. The methyl bromide issue. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons; 1996. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priefert H, Rabenhorst J, Steinbüchel A. Molecular characterization of genes of Pseudomonas sp. strain HR199 involved in bioconversion of vanillin to protocatechuate. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2595–2607. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2595-2607.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redenbach M, Kieser H M, Denapaite D, Eichner A, Cullum J, Kinashi H, Hopwood D A. A set of ordered cosmids and a detailed genetic and physical map for the 8 Mb Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:77–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6191336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhew R C, Miller B R, Weiss R F. Natural methyl bromide and methyl chloride emissions from coastal salt marshes. Nature. 2000;403:292–295. doi: 10.1038/35002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rypniewski W R, Breiter D R, Benning M M, Wesenberg G, Oh B H, Markley J L, Rayment I, Holden H M. Crystallization and structure determination to 2.5 Å resolution of the oxidized [Fe2-S2] ferredoxin isolated from Anabaena 7120. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4126–4131. doi: 10.1021/bi00231a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saemundsdottir S, Matrai P A. Biological production of methyl bromide by cultures of marine phytoplankton. Limnol Oceanogr. 1998;43:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauer K, Harms U, Thauer R K. Methanol:coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcina barkeri. Purification, properties and encoding genes of the corrinoid protein MT1. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:670–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauer K, Thauer R K. Methyl-coenzyme M formation in methanogenic archaea—involvement of zinc in coenzyme M activation. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2498–2504. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaefer J K, Oremland R S. Oxidation of methyl halides by the facultative methylotroph strain IMB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5035–5041. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5035-5041.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serca D, Guenther A, Klinger L, Helmig D, Hereid D, Zimmerman P. Methyl bromide deposition to soils. Atmos Environ. 1998;32:1581–1586. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shorter J H, Klob C E, Crill P M, Kerwin R A, Talbot R W, Hines M E, Harriss R C. Rapid degradation of atmospheric methyl bromide in soils. Nature. 1995;377:717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Studer A, Vuilleumier S, Leisinger T. Properties of the methylcobalamin:H4 folate methyltransferase involved in chloromethane utilization by Methylobacterium sp. strain CM4. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:242–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tizon B, Rodriguez Torres A M, Rodriguez Belmonte E, Cadahia J L, Cerdan E. Identification of a putative methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase by sequence analysis of a 6.8 kb DNA fragment of yeast chromosome VII. Yeast. 1996;12:1047–1051. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199609)12:10B%3C1047::AID-YEA991%3E3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukihara T, Fukuyama K, Mizushima M, Harioka T, Kusunoki M, Katsube Y, Hase T, Matsubara H. Structure of the [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin I from the blue-green-alga Aphanothece sacrum at 2.2 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1990;216:399–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urakami T, Araki H, Oyanagi H, Suzuki K I, Komagata K. Transfer of Pseudomonas aminovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926) to Aminobacter gen. nov. as Aminobacter aminovorans comb. nov. and description of Aminobacter aganoensis sp. nov. and Aminobacter niigataensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vannelli T, Messmer M, Studer A, Vuilleumier S, Leisinger T. A corrinoid-dependent catabolic pathway for growth of a Methylobacterium strain with chloromethane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4615–4620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vannelli T, Studer A, Kertesz M, Leisinger T. Chloromethane metabolism by Methylobacterium sp. strain CM4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1933–1936. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.5.1933-1936.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varner R K, Crill P M, Talbot R W. Wetlands: a potentially significant source of atmospheric methyl bromide and methyl chloride. Geophys Res Lett. 1999;26:2433–2436. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whittenbury R, Phillips K C, Wilkinson J F. Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J Gen Microbiol. 1970;61:205–218. doi: 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshida K, Sano H, Seki S, Oda M, Fujimura M, Fujita Y. Cloning and sequencing of a 29 kb region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the Hut and WapA loci. Microbiology. 1995;141:337–343. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-2-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yvon-Lewis S A, Butler J H. The potential effect of oceanic biological degradation on the lifetime of atmospheric CH3Br. Geophys Res Lett. 1997;24:1227–1230. [Google Scholar]