Abstract

The effects of concentrations of volatile fatty acids on an anaerobic, glucose-limited, and pH-controlled growing culture of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis were studied. Suddenly increasing volatile fatty acids to the concentrations representative of the ceca of 15-day-old broiler chickens caused washout of serovar Enteritidis. In contrast, a sudden increase to the volatile fatty acid concentrations representative of the ceca of younger broiler chickens caused a reduction in the biomass but not washout. Gradually increasing volatile fatty acids caused a gradual decrease in the biomass of serovar Enteritidis. We conclude that the concentrations of volatile fatty acids present in the ceca of broilers with a mature microflora can cause washout of serovar Enteritidis in an in vitro system mimicking cecal ecophysiology.

In recent years, Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis has become the predominant Salmonella causing human salmonellosis in western countries such as the United States and The Netherlands (1, 17). The main reservoirs for human serovar Enteritidis infections are poultry and poultry products (17). Infection of broiler chickens with serovar Enteritidis is age and dose dependent (7–9). Young broiler chickens are particularly susceptible to Salmonella infections (3, 6, 9). Nurmi and Rantale (14) were the first to suggest that this susceptible period is caused by the lack of a mature microflora in young broilers. They observed that treating 1-day-old broilers with a mature cecal microflora from Salmonella-free adult chickens protected these broilers from colonization with Salmonella in the ceca (14). The exact mechanism(s) behind reduction of Salmonella numbers by the mature cecal microflora is not known. Several mechanisms have been postulated: competition for nutrients, competition for receptor sites, immunomodulation, production of antimicrobial substances, or production of volatile fatty acids, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate (see reference 5 and references therein). Still more information is needed to evaluate the relative importance of these mechanisms in reducing Salmonella numbers in the ceca of chickens.

Young broiler chickens (1 to 14 days old) do not contain anaerobic bacteria as a dominant fraction of their cecal microflora (18). Therefore, the concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate are low in the ceca during the first week of life (2, 5, 18). In vivo, it was observed that the increase in concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the ceca is a cause for the decrease in viable counts of members of the family Enterobacteriaceae in the ceca of broiler chickens (18). The aim of this study is to determine the effects of mixtures of volatile fatty acids and lactate on serovar Enteritidis growing under conditions representative of those in the ceca of broilers.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

S. enterica serovar Enteritidis strain CVI-1 (phage type 4) was originally isolated from chickens (19). Serovar Enteritidis was grown in a mineral carbonate-buffered medium. This medium contained the following (per liter of milli-Q water): 0.3 g of NH4Cl, 0.5 g of NaCl, 0.2 g of Na2SO4, 0.4 g of KH2PO4, 0.67 g of Na2HPO4, 4 g of NaHCO3, 0.5 g of yeast extract, 0.5 g of tryptone, 1 ml of Tween 80, 1 mg of resazurine, 10 ml of trace element solution (15), 10 ml of vitamin solution (15), and 30 mM glucose. Cecal growth conditions were mimicked in an in vitro system, which operated as a sequencing fed-batch reactor. This means that a cycle of 12 h was repeated continuously in the reactor. During a cycle, the working volume of the culture vessel (1.5-liter chemostat) increased in 11 h 53 min from 100 to 500 ml. Subsequently, the volume decreased in 7 min to 100 ml. The flow rate of the medium was kept constant at 34.4 ml h−1. The headspace of the culture vessel was flushed with a nitrogen-carbon dioxide mixture (80 and 20%, respectively) at a flow rate of 4.2 liters h−1. The pH was kept constant at 5.8 ± 0.1 with 1 N NaOH and 1 N HCl, and the temperature was maintained at 41°C. The culture vessel was inoculated with 1 ml of an overnight-grown culture of serovar Enteritidis. Transient states were obtained 24 h after glucose became the substrate-limiting nutrient for serovar Enteritidis (approximately 7 days).

Addition of volatile fatty acids and lactate.

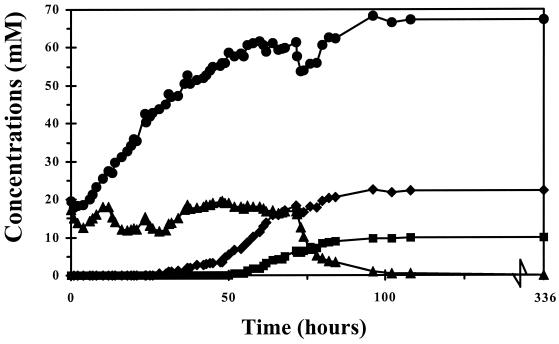

After serovar Enteritidis reached transient-state conditions, volatile fatty acids and lactate were administered in two ways. First, volatile fatty acids and lactate were administered to the medium and culture vessel simultaneously as sodium salts. This caused a sudden increase in the concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate (Table 1). These concentrations are representative of those in the ceca of 5-, 8-, and 15-day-old broiler chickens (18). Second, volatile fatty acids and lactate were added as sodium salts to the medium vessel every 6 h during a period of 72 h, resulting in a gradual increase (Fig. 1). The concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate were representative of the ceca of 5-day-old broilers after 24 h, of 8-day-old broilers after 48 h, of 15-day-old broilers after 72 h, and of 37-day-old broilers after 96 h (18). In both types of experiments, the culture vessel was sampled intensively for 72 h. Thereafter, samples were taken every 24 h just before the volume decreased from 500 to 100 ml.

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate in the culture vessela

| Age (days) of chickens mimicked | Avg concn (mM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate | Lactate | Butyrate | Propionate | |

| 5 | 46.7 | 12.2 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 60.3 | 20.1 | 4.05 | 0 |

| 15 | 66.2 | 18.4 | 22.2 | 6.47 |

Average concentrations of acetate, lactate, butyrate, and propionate as determined in the culture vessel after addition of these compounds. The concentrations of these compounds mimicked concentrations in the ceca of 5-, 8-, and 15-day-old broiler chickens (18).

FIG. 1.

Gradual increase in acetate, lactate, butyrate, and propionate concentrations as determined in the culture vessel after addition of these compounds to the medium vessel every 6 h. This increase mimicked the increase of volatile fatty acids and lactate in the ceca of 1- to 37-day-old broiler chickens (18). Symbols: ●, acetate; ▴, lactate; ⧫, butyrate; ■, propionate.

The biomass of serovar Enteritidis was estimated by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) and by determining the total amount of cell protein (11). Glucose limitation in the culture vessel was determined colorimetrically using a glucose oxidase test (Boehringer Mannheim). The concentrations of glucose, volatile fatty acids, and lactate were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. After the samples were thawed, 990 μl of sample was acidified with 10 μl of a 25% HCl solution and subsequently samples were prepared and measured by high-performance liquid chromatography as previously described by van der Wielen et al. (18).

Effect of suddenly increasing volatile fatty acids and lactate.

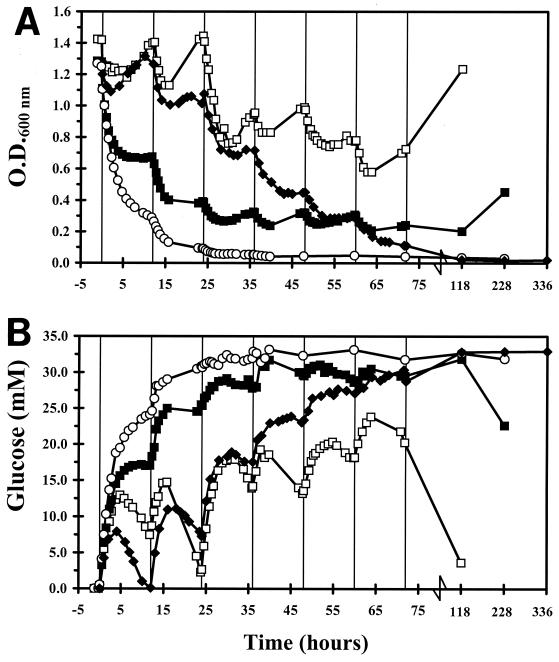

OD600 and total cell protein measurements showed similar results (data not shown). Therefore, only OD600 data are presented as a measure for biomass. If the concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate suddenly increased to the concentrations measured in the ceca of 5-day-old broiler chickens, the OD600 remained more or less stable for 24 h (Fig. 2A). Thereafter, OD600 decreased until 64 h after which it increased again. In contrast, a sudden increase to the concentrations in the ceca of 8-day-old broilers caused an immediate drop in OD600 and the OD600 decreased to values lower than those in 5-day-old broilers. After 118 h, the OD600 started to increase again. Suddenly increasing volatile fatty acid and lactate concentrations to the concentrations in the ceca of 15-day-old broilers caused an even more dramatic drop in OD600. After 36 h, the OD600 stabilized at 0.04 and remained at this value for at least 228 h. During the first 24 h after this sudden increase, the OD600 decreased according to the theoretically calculated dilution curve. This indicates that these concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate had a bacteriostatic effect on serovar Enteritidis.

FIG. 2.

Changes in OD600 (A) and glucose concentration (B) after addition of different concentrations of volatile fatty acids to the sequencing fed-batch reactor. Symbols indicate addition of volatile fatty acids mimicking ceca of 5-(□), 8-(■), and 15-day-old (○) broilers and the gradual increase of volatile fatty acids as depicted in Fig. 1 (⧫).

The increase in glucose concentrations after addition of volatile fatty acids and lactate as measured in the ceca of 5-day-old broiler chickens reached 72% of the glucose concentration in the medium vessel (Sr) (Fig. 2B). This indicates that these concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate reduced the capacity of serovar Enteritidis to metabolize glucose. After 72 h, glucose concentrations started to decrease again. Adding volatile fatty acids and lactate comparable to the concentrations in the ceca of 8-day-old broilers caused an increase of glucose to 91% of Sr, which was between the values for the two other treatments (days 5 and 15). After 120 h, the residual glucose concentration started to decrease again. The increase in glucose concentrations was biggest (100% of Sr) after a sudden increase to the concentrations in the ceca of 15-day-old broilers. The glucose concentration remained at this level for at least 228 h.

The results from these in vitro experiments were compared with observations made in in vivo studies (6, 9, 16, 18). In very young broiler chickens (less than 8 days old), the concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate are very low in the ceca (18). Infecting 1- and 7-day-old broilers with serovar Enteridis shows high numbers of 108 and 107 per g of cecal content, respectively. In contrast, broilers infected at 21 days of age show low numbers of 103 per g of cecal content (6). This suggests that there might be an association between the low concentrations of volatile fatty acids in the ceca of young broilers and the high susceptibility to Salmonella colonization in the ceca. The results from our study show for the first time that serovar Enteritidis grown under cecal growth conditions is very susceptible to a sudden increase in volatile fatty acid concentrations as measured in the ceca of broilers older than 14 days. Even though other mechanisms proposed can still play some role in reducing the number of salmonellae in the ceca of broilers (5), we conclude that the bacteriostatic effect of volatile fatty acids is a pivotal mechanism in reducing the susceptibility for colonization by Salmonella as broilers age.

Effect of gradually increasing volatile fatty acids.

From the previous experiments, it is clear that serovar Enteritidis could adapt to day 5 or day 8 concentrations. Therefore, it was studied whether Salmonella was able to adapt to volatile fatty acids and lactate when they increased gradually over time. The gradual increase in concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate in the culture vessel mimicking the cecal ecophysiology caused a gradual reduction of the OD600 of serovar Enteritidis without any significant adaptation (Fig. 2A). After 96 h (representing cecal conditions of 37-day-old chickens), OD600 had decreased to 0.028 and remained at this value for at least 336 h.

Glucose concentrations increased gradually after gradually increasing concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate in the culture vessel (Fig. 2B). Glucose concentrations increased to 24% of Sr after 24 h, to 77% of Sr after 48 h, and to 94% of Sr after 72 h. After 96 h, glucose reached a concentration of 100% of Sr and remained at this value for 336 h. Again, this indicates that glucose consumption by serovar Enteritidis could not be detected.

The gradual increase of volatile fatty acids is faster than was observed in ceca of broiler chickens during growth (18). In contrast, it was observed in studies with competitive exclusion cultures that 1-day-old broiler chickens receiving a mixture of cecal bacterial strains had a very rapid increase in concentrations of volatile fatty acids in the ceca (4, 10, 13). It has been proposed that this fast but gradual increase might be responsible for the decrease in the numbers of salmonellae (5). Administration of different defined bacterial mixtures to 1-day-old broilers showed that cecal propionate concentrations in 3-day-old broilers correlated negatively with the numbers of salmonellae in the ceca of 10-day-old broilers (12). However, these researchers do not conclude that propionate caused the reduction in Salmonella. Propionate may be an indication that the cecal bacterial strains applied have become established in the ceca at 3 days of age but that these bacteria inhibit Salmonella by other mechanisms (12). Here, we report in an in vitro model that a fast gradual increase in concentrations of volatile fatty acids and lactate causes very low biomass of serovar Enteritidis. In contrast, a sudden increase to concentrations mimicking those in the ceca of 5-day-old broilers resulted in adaptation of serovar Enteritidis. This could be an indication that the slow gradual increase in volatile fatty acids, as observed in the ceca of nontreated broilers, does not cause a significant reduction in the biomass of serovar Enteritidis. Therefore, the results of our experiments fully support the hypothesis that a rapid gradual increase in volatile fatty acids is the most important reason for lower numbers of salmonellae in the ceca of broilers treated with competitive exclusion cultures (4, 10, 12, 13). This result is important not only for understanding the mechanism(s) behind Salmonella reduction in the ceca of older broilers or broilers treated with competitive exclusion cultures but also for selection of cecal bacterial strains in competitive exclusion mixtures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amos Zhao for providing us with the strain of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis and David Keuzenkamp, Otto van de Beek, and Peter Scherpenisse for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angulo F J, Swerdlow D L. Epidemiology of human Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis infections in the United States. In: Saeed A M, editor. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in humans and animals. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1999. pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes E M, Impey C S, Stevens B J H. Factors affecting the incidence and anti-Salmonella activity of the anaerobic cecal flora of the young chick. J Hyg. 1979;82:263–283. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400025687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper G L, Venables L M, Woodward M J, Hormaeche C E. Invasiveness and persistence of Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella typhimurium, and a genetically defined S. enteritidis aroA strain in young chickens. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4739–4746. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4739-4746.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrier D E, Hinton A, Jr, Ziprin R L, Beier R C, DeLoach J R. Effect of dietary lactose and anaerobic cultures of cecal flora on Salmonella colonization of broiler chicks. In: Blankenship L C, editor. Colonization control of human bacterial enteropathogens in poultry. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrier D E, Hinton A, Jr, Ziprin R L, DeLoach J R. Effect of dietary lactose on Salmonella colonization of market-age broiler chickens. Avian Dis. 1990;34:668–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchet-Suchaux M, Lechopier P, Marly J, Bernardet P, Delaunay R, Pardon P. Quantification of experimental Salmonella enteritidis carrier state in B13 leghorn chicks. Avian Dis. 1995;39:796–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gast R K. Applying experimental infection models to understand the pathogenesis, detection, and control of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in poultry. In: Saeed A M, editor. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in humans and animals. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1999. pp. 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gast R K, Benson S T. Intestinal colonization and organ invasion in chicks experimentally infected with Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 and other phage types isolated from poultry in the United States. Avian Dis. 1996;40:853–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorham S L, Kadavil K, Lambert H, Vaughan E, Pert B, Abel J. Persistence of Salmonella enteritidis in young chickens. Avian Pathol. 1991;20:433–437. doi: 10.1080/03079459108418781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hume M E, Corrier D E, Nisbet D J, DeLoach J R. Reduction of Salmonella crop and cecal colonization by a characterized competitive exclusion culture in broilers during grow-out. J Food Prot. 1996;59:688–693. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.7.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N H, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nisbet D J, Corrier D E, Ricke S C, Hume M E, Byrd II J A, DeLoach J R. Cecal propionic acid as a biological indicator of the early establishment of a microbial ecosystem inhibitory to Salmonella in chicks. Anaerobe. 1996;2:345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nisbet D J, Ricke S C, Scanlan C M, Corrier D E, Hollister A G, DeLoach J R. Inoculation of broiler chicks with a continuous-flow derived bacterial culture facilitates early cecal bacterial colonization and increases resistance to Salmonella typhimurium. J Food Prot. 1994;57:12–15. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-57.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nurmi E, Rantale M. New aspects of Salmonella infection in broiler production. Nature. 1973;241:210–211. doi: 10.1038/241210a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otto R, Ten Brink B, Veldkamp H, Koning W N. The relation between growth rate and electrochemical proton gradient of Streptococcus cremoris. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;16:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadler W W, Brownell J R, Fanelli M J. Influence of age and inoculum level on shed pattern of Salmonella typhimurium in chickens. Avian Dis. 1969;13:793–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Giessen A W, van Leeuwen W J, van Pelt W. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in the Netherlands: epidemiology, prevention and control. In: Saeed A M, editor. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis in humans and animals. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1999. pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Wielen P W J J, Biesterveld S, Notermans S, Hofstra H, Urlings B A P, van Knapen F. Role of volatile fatty acids in development of the cecal microflora in broiler chickens during growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2536–2540. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.6.2536-2540.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Zijderveld F G, van Zijderveld-van Bemmel A M, Anakotta J. Comparison of four different enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for serological diagnosis of Salmonella enteritidis infections in experimentally infected chicken. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2560–2566. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.10.2560-2566.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]