Abstract

Background

Men who have sex with men (MSM) account for most new HIV diagnoses in the US. Annual HIV testing is recommended for sexually active MSM if HIV status is negative or unknown. Our primary study aim was to determine annual HIV screening rates in primary care across multiple years for HIV-negative MSM to estimate compliance with guidelines. A secondary exploratory endpoint was to document rates for non-MSM in primary care.

Methods

We conducted a three-year retrospective cohort study, analyzing data from electronic medical records of HIV-negative men aged 18 to 45 years in primary care at a large academic health system using inferential and logistic regression modeling.

Results

Of 17,841 men, 730 (4.1%) indicated that they had a male partner during the study period. MSM were screened at higher rates annually than non-MSM (about 38% vs. 9%, p<0.001). Younger patients (p-value<0.001) and patients with an internal medicine primary care provider (p-value<0.001) were more likely to have an HIV test ordered in both groups. For all categories of race and self-reported illegal drug use, MSM patients had higher odds of HIV test orders than non-MSM patients. Race and drug use did not have a significant effect on HIV orders in the MSM group. Among non-MSM, Black patients had higher odds of being tested than both White and Asian patients regardless of drug use.

Conclusions

While MSM are screened for HIV at higher rates than non-MSM, overall screening rates remain lower than desired, particularly for older patients and patients with a family medicine or pediatric PCP. Targeted interventions to improve HIV screening rates for MSM in primary care are discussed.

Introduction

The incidence of HIV infection in the United States has decreased over the past decade, but the number of new infections among men who have sex with men (MSM) has plateaued around 26,000 per year [1]. In 2018, MSM accounted for 69% of all new HIV diagnoses [2]. The lifetime risk of HIV diagnosis among MSM is 88 times the risk of non-MSM.[3].

Due to the higher risk of HIV infection among MSM, frequent screening is paramount to prevention and timely treatment. Since 2006, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has recommended that sexually active MSM be screened for HIV at least once annually if HIV status is negative or unknown. More frequent screening is recommended for MSM with higher risk sexual behaviors [4]. As often as every 3 to 6 months, screening may be more effective in averting lifetime costs associated with HIV infection than annual screening [5].

Despite these recommendations, HIV screening remains suboptimal. The percentage of undiagnosed infections among all MSM is estimated at 15% and is much higher among young MSM [6]. Those with undiagnosed infection and those diagnosed but not receiving care are responsible for most new HIV transmissions [7]. Although 77% of MSM surveyed for National HIV Behavioral Surveillance self-reported being screened in the past year [8], a recent systematic review found that self-reported 12-month screening rates for MSM vary widely, from 40% to 71% [9]. MSM are tested in clinical settings, but these also vary widely and include primary care and specialty clinics, emergency departments, urgent care, hospitals, sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, and drug treatment programs, among others. The proportion of tests done by primary care providers (PCPs) is therefore unclear. In addition, among non-MSM there is always a portion who are bi-sexual, have not realized their sexual orientation, or describe their sexual orientation in other terms and would benefit from the annual HIV screening guidelines.

Previous studies have found that HIV-negative MSM with a PCP are more likely to be tested for HIV than other men [10, 11] and a majority of MSM report that their PCP is aware of their sexual orientation [12]. This suggests that PCPs are ideally positioned to improve HIV screening for MSM.

Our primary study objective was to determine medical-record verified annual HIV screening rates in primary care across multiple years for HIV-negative MSM to estimate compliance with guidelines. A secondary exploratory endpoint was to document rates for non-MSM in primary care.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective chart review of HIV-negative men with PCPs at Michigan Medicine. Primary care specialties were defined as family medicine, internal medicine, medicine-pediatrics, or pediatrics. Michigan Medicine primary care includes 16 clinic locations, serving three counties in Southeast Michigan. Patients included in this study were all males with no prior HIV diagnosis between 18 and 45 years who had at least one primary care encounter between March 2016 and March 2019. We chose 2016 as the index year because the question of the sexual partners’ gender became coded data elements with the clinic contact. Eligible patients were grouped based on reported sexual partners at the most recent disclosure. Individuals who reported having a male sexual partner or both a male and female partner were included in the MSM group. The non-MSM group included individuals who reported only a female partner or no partner. Patients who did not answer the question were excluded from the study. The study proposal was submitted to the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan Medical School and was exempted from ongoing IRB review (HUM00155091). Individual consent was waived for this study.

Data were obtained from a computerized search of the Michigan Medicine electronic medical records (EMR) and included patient age, race, sexual partner gender, HIV test order dates, self-reported alcohol consumption, and self-reported illegal drug use, in addition to provider specialty. All HIV test orders were included for analysis, regardless of whether a result was available. For patients who did not have an HIV test ordered, we additionally searched encounter notes for the terms "HIV" and "STI" in conjunction with "counsel," "screen," and "test." The presence of these terms could indicate a pertinent discussion about testing for HIV. Annual rates of HIV screening were calculated in three 12-month time periods by counting at least one HIV test order for a unique person in that 12 -month time period divided by the identified MSM population in that same time frame. Additionally, rates of HIV discussion among MSM were similarly counted through medical note documentation for those without an HIV test order. The same procedure was completed separately for non-MSM. Chi-square tests, stratified by time period, compared HIV testing and discussion rates between MSM and non-MSM patients. A Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test was used to compare the difference in HIV testing and discussion rates between groups across the three time periods.

Associations with having an HIV test ordered were evaluated using a clustered logistic regression model under a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) framework to account for repeated measures on the same patient across time periods. Models were adjusted for age, race, substance use (alcohol and illegal drugs), provider specialty, and time period. The main covariate of interest was group (MSM vs non-MSM). Interactions between group and other variables were investigated using F-tests to evaluate their inclusion by jointly testing the significance of all parameters involved in the interaction term. To aid in the interpretation of significant interactions, marginal effects and probabilities at set levels of covariates were estimated. All statistics were performed using Stata 15.1 software.

Results

In total, 17,841 men met the criteria for inclusion over all three years. About 40% had data in all three time periods, 30% had data in two time periods, and the remaining 30% had data in only a single time period. Records identified 730 (4.1%) patients as having a male partner at some point during the study period. Compared with the non-MSM group, MSM patients were younger, were more often Hispanic, and more likely to use alcohol and illegal drugs (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of MSM and non-MSM.

| MSM | Non-MSM | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 730) | (n = 17,111) | ||

| Age, mean(SD) | 30.9 (6.8) | 34.7 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Age Group, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| 18–25 | 180 (24.7) | 2,095 (12.2) | |

| 26–30 | 203 (27.8) | 2,847 (16.6) | |

| 31–35 | 153 (21.0) | 3,719 (21.7) | |

| 36–40 | 117 (16.0) | 4,109 (24.0) | |

| 41–45 | 77 (10.6) | 4,341 (25.4) | |

| Race, n(%) | 0.67 | ||

| White | 563 (78.2) | 12,857 (76.3) | |

| Black | 64 (8.9) | 1,591 (9.4) | |

| Asian | 65 (9.0) | 1,624 (9.6) | |

| Other | 28 (3.9) | 773 (4.6) | |

| Hispanic, n(%) | 37 (5.1) | 760 (4.6) | 0.49 |

| Female Partner ever n(%) | 172 (23.6) | 16,618 (97.1) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use, n(%) | 527 (80.2) | 12,101 (76.2) | 0.018 |

| Illegal Drugs, n(%) | 112 (17.8) | 1,726 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| IV Drugs, n(%) | 1 (0.2) | 12 (0.07) | 0.49 |

| Department, n(%) | 0.07 | ||

| Family Medicine | 347 (47.5) | 8,501 (49.7) | |

| Internal Medicine | 341 (46.7) | 7,354 (43.0) | |

| Internal Medicine-Pediatrics | 34 (4.7) | 1,111 (6.5) | |

| Pediatrics | 8 (1.1) | 145 (0.9) |

Primary outcome: HIV test ordering. The HIV test ordering rates for MSM ranged between 35–43% per year, significantly higher than the 9% for non-MSM in each year (Table 2). The CMH test for homogeneity of odds ratios across the three years was not significant (p-value = 0.19), suggesting this difference in HIV test ordering rates between groups was consistent across the three time periods. For encounters that did not have an HIV test ordered, MSM encounter notes were significantly more likely to contain HIV terms than non-MSM notes, suggesting a screening discussion occurred (MSM 20% vs non-MSM 10% in each year, p-values<0.001), but, likewise, this was also not significantly different across the three years. In addition, the combined discussion of any HIV and/or STI terms in the encounter notes was not different between MSM and non-MSM over all three years CMH homogeneity test (p-value = 0.12).

Table 2. Yearly HIV test order rates and noted HIV discussion by MSM vs. non-MSM.

| HIV TESTS ORDERED % (95% CI) | HIV TERMS IN NOTE WITHOUT HIV TEST ORDER, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM | Non-MSM | p-value | MSM | Non-MSM | p-value | |

| YEAR 1 | N = 478 | N = 11,235 | N = 309 | N = 10,275 | ||

| 3/1/16-2/28/17 | 35.3 (31.2, 39.8) | 8.5 (8.0, 9.1) | <0.001 | 21.4 (17.1, 26.3) | 10.9 (10.3, 11.5) | <0.001 |

| YEAR 2 | N = 533 | N = 11,887 | N = 335 | N = 10,870 | ||

| 3/1/17-2/28/18 | 37.1 (33.1, 41.3) | 8.6 (8.1, 9.1) | <0.001 | 19.7 (15.8, 24.3) | 10.4 (9.9, 11.0) | <0.001 |

| YEAR 3 | N = 550 | N = 12,394 | N = 316 | N = 11,277 | ||

| 3/1/18-2/28/19 | 42.5 (38.5, 46.7) | 9.0 (8.5, 9.5) | <0.001 | 20.6 (16.5, 25.4) | 10.9 (10.4, 11.5) | <0.001 |

CMH across years for MSM was not significant for HIV tests ordered or for HIV terms in encounter notes indicating there was no difference in rates among years.

The logistic regression model did not find a significant effect of time-period on the likelihood of ordering an HIV test (Table 3). However, when adjusting for group, age, PCP department, race, alcohol and illegal drug use, all were associated with HIV test ordering. Older individuals were significantly less likely to have an HIV test ordered (aOR (95% CI) = 0.937 (0.93, 0.94)), and individuals with a history of alcohol use were more likely to have a test ordered (aOR (95% CI) = 1.18 (1.06, 1.30)). Patients of pediatricians were less likely to have an HIV test ordered compared with patients of family medicine physicians (aOR(95% CI) = 0.22 (0.12, 0.40)) and internal medicine patients were more likely than family medicine patients (aOR (95% CI) = 1.19 (1.10, 1.30)).

Table 3. GEE model results on HIV test order.

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.94 | [0.93, 0.94] | 0.000 |

| Department (Ref = Family Medicine) | |||

| Internal Medicine | 1.19 | [1.10, 1.30] | 0.000 |

| Internal Medicine, Pediatrics | 1.06 | [0.89, 1.25] | 0.504 |

| Pedicatrics | 0.22 | [0.12, 0.40] | 0.000 |

| Alcohol Use (Ref = none) | 1.18 | [1.06, 1.30] | 0.001 |

| Drug Use (Ref = none) | 1.85 | [1.63, 2.10] | 0.000 |

| Race (Ref = White) | |||

| Black | 3.10 | [2.72, 3.54] | 0.000 |

| Asian | 0.97 | [0.81, 1.16] | 0.715 |

| Other Race | 1.34 | [1.08, 1.66] | 0.007 |

| Group (Ref = Non-MSM) | |||

| MSM | 6.72 | [5.74, 7.88] | 0.000 |

| Time (Ref = Year 1) | 1.00 | ||

| Year 2 | 1.00 | [0.92, 1.09] | 0.971 |

| Year 3 | 1.01 | [0.93, 1.10] | 0.791 |

| Group*Drug Use Interaction Term | |||

| MSM*Drug Use | 0.62 | [0.45, 0.85] | 0.003 |

| Group*Race Interaction Terms | |||

| MSM*Black | 0.45 | [0.29, 0.69] | 0.000 |

| MSM*Asian | 1.29 | [0.81, 2.07] | 0.282 |

| MSM*Other Race | 0.85 | [0.45, 1.63] | 0.629 |

| Drug Use*Race Interaction Terms | |||

| Drug Use*Black | 0.70 | [0.55, 0.90] | 0.006 |

| Drug Use*Asian | 0.74 | [0.39, 1.42] | 0.368 |

| Drug Use*Other Race | 1.40 | [0.86, 2.29] | 0.177 |

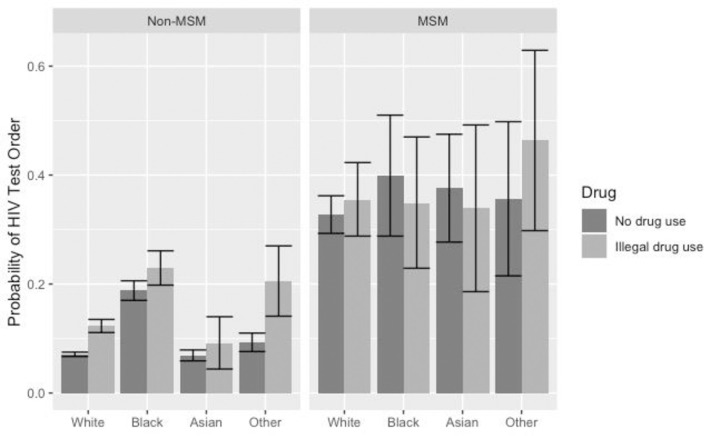

Significant group interactions were found with race (interaction F-test p-value = 0.01) and illegal drug use (interaction F-test p-value = 0.006). Within MSM patients, there were no significant differences in the likelihood of test orders based on levels of drug use or race. However, in the non-MSM group, there were both significant race and drug use effects. Fig 1 illustrates interaction results through the predicted probability of HIV tests being ordered under different levels of group, race, and self-reported illegal drug use.

Fig 1. Predicted probability of HIV test ordering by MSM v non-MSM, race, and Illegal drug use status.

The probabilities of HIV test ordering estimated from regression GEE modeling were adjusted for patient age, group (MSM vs non-MSM), race, PCP department, time, alcohol use and illegal drug use. Interactions of group*race, group*illegal drug use and race*illegal drug use were included, the group*race*drug use interaction was not significant.

The MSM group had a higher probability of HIV testing being ordered, compared with non- MSM, regardless of race or illegal drug use. Within the non-MSM group, race differences were found between Black patients and both White and Asian, with Black patients having a higher probability of test ordered regardless of drug use. In all non-MSM racial groups, except Asians, there were significantly higher rates of HIV test ordering among drug users than those who self-reported no illegal drug use.

Discussion

We are the first to document medically verified HIV test ordering from a large electronic health record of patients receiving primary care that was not a short-term quality improvement project [13]. Our results of an HIV test order rate are between 35–43% for MSM, considerably lower than the CDC or USPSTF goal [1, 2, 8, 14, 15]. Others have shown that men who self-disclose MSM status are more likely to have HIV testing ordered than not [16–18]. On the other hand, among the non-MSM, we document a much higher frequency of HIV testing in our study at 9% compared with 2% in other populations of non-MSM [13].

In addition, by analyzing data over three years, we find that the HIV testing rate for MSM is consistently low, thus establishing a reliable baseline annual testing rate. These results hold even after adjusting for self-report alcohol or illegal drug use, prominent risk factors for HIV outside of sexual orientation. We are also the first to show that among those MSM without an HIV test order entered into the health system, only 20% receive HIV counseling as documented in the text of the note, severely lower than is necessary to raise awareness and identify those who could benefit [4]. These baseline testing and counseling rates are essential for future quality improvement interventions to meet CDC or USPSTF screening goals.

Our results suggest that current systems are inadequate. We hypothesize that multi-level interventions with the health system, primary care physicians, and men themselves could be necessary to increase the HIV test ordering rate. The CDC estimates that 15% of men are unaware that they have HIV, in part, because they have never been tested [19]. The portion of MSM who do not have a PCP is unknown, as many seek care through STI clinics or Emergency Departments [20]. Even with a PCP, many MSM may not disclose their sexual orientation, often due to negative experiences or perceived quality of communication [21], despite recommendations to do so [22]. Studies about physician-related barriers to care reveal that some take a complete sexual history only when relevant to the chief complaint [23]. Even if the PCP is aware of the patients’ sexual orientation, MSM-specific screening guidelines may not be known [24].

We showed that among non-MSM, HIV testing was greater among persons of color independent of self-reported alcohol and illegal drug use. These findings correlate to the successful increased public health campaigns to target Black and Hispanic men who are infected with HIV at disproportionately higher rates than White men. Despite this effort which has resulted in higher rates of HIV screening among Black and Hispanic men [11, 13, 25], no improved health outcomes have been documented from this increased testing [16]. Nevertheless, our work supports the need for universal screening to all races, potentially prompted by a best policy advisory from the EMR or national quality metrics [13, 26].

Limitations

While the medically verifiable HIV test order is a strength of this work, the self-report characteristics of sexual practice, sexual orientation, alcohol use, and illegal drug use cannot be verified and may cause misclassification of risk factors and outcome populations [27]. As we stated in the methods section, patients with missing data for a sexual partner were not included in our analysis.

Moreover, we cannot verify the veracity of what was said in the clinic visit and what the PCP documented. While all patients who identified as MSM in our study had a male sexual partner by self-disclosure at some point during the study period, it is unclear whether the PCPS were aware of this designation before the office visit. Furthermore, while a proportion of encounter notes suggest discussion of HIV for MSM who did not have a test order, we cannot verify how accurately EHR documentation reflects actual patient-provider discussions.

Methodologically, our results are not weighted by population proportions across other demographic characteristics. Therefore, we cannot generalize results to a wider population than our clinic panels.

In addition, we are not able to evaluate the barriers physicians may have encountered in offering this testing. Barriers to HIV testing, such as lack of provider comfort with discussing sexual behavior and knowledge about HIV screening and treatment, are well documented and highlight problems with screening patients based on individual risk assessment [28] reinforcing the need for universal testing.

Conclusion

While MSM are screened for HIV at higher rates than non-MSM, overall screening rates remain lower than desired, particularly for older patients and patients with a family medicine or pediatric PCP. Targeted interventions are needed to improve HIV screening rates for MSM in primary care.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Data Office for Clinical & Translational Research at the University of Michigan Medical School and especially Chiu-Mei, Jeff Cowall, and Rino Srivastava for the coding required to extract EMR data from this project.

Abbreviations

- MSM

men who have sex with men (MSM)

- PCP

primary care provider (PCP)

- EMR

electronic medical records (EMR)

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

- STI

sexually transmitted infection (STI)

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control (CDC)

- CMH

Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel (CMH) test

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) framework

Data Availability

Data files are available from Michigan's Deep Blue database (https://doi.org/10.7302/00fw-qr09).

Funding Statement

NCATS funding through UL1TR002240 The University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center P30CA046592.

References

- 1.CDC2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2019;24(No. 1). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html Published February 2019. Accessed July 12, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018. (Updated); vol. 31. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published May 2020. Accessed August 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017. Apr;27(4):238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.02.003 Epub 2017 Feb 21. ; PMCID: PMC5524204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015. Jun 5;64(RR-03):1–137. Erratum in: MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Aug 28;64(33):924. ; PMCID: PMC5885289. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Delaney KP, Bowles K, Martin T, Tailor A, et al. Evaluating the evidence for more frequent than annual hiv screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States: Results from a systematic review and CDC expert consultation. Public Health Rep. 2018. Jan/Feb;133(1):3–21. doi: 10.1177/0033354917738769 Epub 2017 Nov 28. ; PMCID: PMC5805092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Song R, Johnson AS, McCray E, Hall HI. HIV Incidence, Prevalence, and undiagnosed infections in US men who have sex with men. Ann Intern Med. 2018. May 15;168(10):685–694. doi: 10.7326/M17-2082 Epub 2018 Mar 20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Purcell DW, Sansom SL, Hayes D, Hall HI. Vital Signs: HIV Transmission along the continuum of care—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019. Mar 22;68(11):267–272. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6811e1 ; PMCID: PMC6478059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men—National HIV behavioral surveillance, 23 US Cities, 2017. HIV Surveillance Special Report 22. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published February 2019. Accessed September 2020.

- 9.Noble M, Jones AM, Bowles K, DiNenno EA, Tregear SJ. HIV Testing among internet-using MSM in the United States: Systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2017. Feb;21(2):561–575. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1506-7 ; PMCID: PMC5321102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petroll AE, DiFranceisco W, McAuliffe TL, Seal DW, Kelly JA, Pinkerton SD. HIV testing rates, testing locations, and healthcare utilization among urban African-American men. J Urban Health. 2009. Jan;86(1):119–31. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9339-y Epub 2008 Dec 9. ; PMCID: PMC2629519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter G, Owens C, Lin HC. HIV screening and the Affordable Care Act. Am J Mens Health. 2017. Mar;11(2):233–239. doi: 10.1177/1557988316675251 Epub 2016 Oct 22. ; PMCID: PMC5675292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petroll AE, Mosack KE. Physician awareness of sexual orientation and preventive health recommendations to men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2011. Jan;38(1):63–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ebd50f ; PMCID: PMC4141481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcelin JR, Tan EM, Marcelin A, Scheitel M, Ramu P, Hankey R, et al. Assessment and improvement of HIV screening rates in a Midwest primary care practice using an electronic clinical decision support system: a quality improvement study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016. Jul 4;16:76. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0320-5 ; PMCID: PMC4932674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force*. Screening for HIV: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013. Jul 2;159(1):51–60. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Screening for HIV Infection: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019. Jun 18;321(23):2326–2336. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.6587 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh V, Crosby RA, Gratzer B, Gorbach PM, Markowitz LE, Meites E. Disclosure of sexual behavior is significantly associated with receiving a panel of health care services recommended for men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2018. Dec;45(12):803–807. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000886 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, Samet JH. Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2004. Apr;19(4):349–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x ; PMCID: PMC1492189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lazar NR, Salas-Humara C, Wood SM, Mollen CJ, Dowshen N. Missed opportunities for HIV screening among a cohort of adolescents with recently diagnosed hiv infection in a large pediatric hospital care network. J Adolesc Health. 2018 Dec;63(6):799–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.010 Epub 2018 Oct 2. ; PMCID: PMC6246808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.HIV.gov. Too Many People Living with HIV in the US Don’t Know It. Available from https://www.hiv.gov/blog/too-many-people-living-hiv-us-don-t-know-it Accessed July 11, 2021.

- 20.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Colleran CM, Holcomb R, Operario D, et al. Access to healthcare, HIV/STI testing, and preferred pre-exposure prophylaxis providers among men who have sex with men and men who engage in street-based sex work in the US PLOS ONE. 2014;9(11): e112425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman TA, Bauer GR, Pugh D, Aykroyd G, Powell L, Newman R. Sexual orientation disclosure in primary care settings by gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in a Canadian city. LGBT Health. 2017. Feb;4(1):42–54. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0004 Epub 2016 Dec 20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cahill S, Singal R, Grasso C, King D, Mayer K, Baker K, et al. Do ask, do tell: high levels of acceptability by patients of routine collection of sexual orientation and gender identity data in four diverse American community health centers. PLoS One. 2014. Sep 8;9(9):e107104. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107104 ; PMCID: PMC4157837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, Moore SE, Fry-Johnson Y. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006. Dec;98(12):1924–9. ; PMCID: PMC2569695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbee LA, Dhanireddy S, Tat SA, Marrazzo JM. Barriers to bacterial sexually transmitted infection testing of HIV-infected men who have sex with men engaged in HIV primary care. Sex Transm Dis. 2015. Oct;42(10):590–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000320 ; PMCID: PMC4576720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall KM, Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS. Offering of HIV screening to men who have sex with men by their health care providers and associated factors. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2010. Sep-Oct;9(5):284–8. doi: 10.1177/1545109710379051 Epub 2010 Sep 14. ; PMCID: PMC3637046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tillison AS, Avery AK. Evaluation of the impact of routine HIV screening in primary care. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2017. Jan/Feb;16(1):18–22. doi: 10.1177/2325957416666677 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch KE, Viernes B, Schliep KC, Gatsby E, Alba PR, DuVall SL, et al. Variation in sexual orientation documentation in a national electronic health record system. LGBT Health. 2021. Apr;8(3):201–208. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0333 Epub 2021 Feb 24. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagchi AD, Davis T. Clinician barriers and facilitators to routine HIV testing: A systematic review of the literature. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2020. Jan-Dec;19:2325958220936014. doi: 10.1177/2325958220936014 ; PMCID: PMC7322815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]