Abstract

Introduction The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has made otolaryngologists more susceptible than their counterparts to its effect.

Objective This study aimed to find if COVID-19 had a different impact on ear, nose, and throat (ENT) physicians' of various categories (residents, registrars, and consultants ) regarding many aspects of the quality of life (protection, training, financial, and psychological aspects).

Methods We included 375 ENT physicians, of different categories (residents, registrars, and consultants), from 33 general hospitals and 26 university hospitals in Egypt. The study was conducted using a 20-item questionnaire with a response scale consisting of three categories: yes, no, and not sure. It covered infection control and personal protective equipment (PPE) usage; medical practice and safety; online consultation and telemedicine,; webinars and online lectures; COVID-19 psychological, financial, and quarantine period effects; and future expectations.

Results The results of the questionnaire showed that COVID-19 had a statistically significant impact on the daily life of the responders. There were statistically significant differences among the three involved categories, based on their answers.

Conclusion This study showed a statistically significant difference regarding the impact of COVID-19 on many aspects of the quality of life (protection, training, financial, and psychological aspects) of ENT physicians of various categories (residents, registrars, and consultants), and these effects may persist for a long time.

Keywords: COVID-19, quality of life, impact, otolaryngology

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) pandemic started in December 2019 in Wuhan, Hubei province, in China. 1 After a while, it spread to most countries worldwide, affecting people of all classes and with different jobs. Direct human-to-human transmission results from droplets' projection, hand contact, or via an inert surface. 2

Most countries have tight restrictions on lockdown and social spacing to prevent serious consequences. 3 Moreover, healthcare workers are the group most vulnerable to this lethal virus. 4 Anosmia and ageusia are prevalent symptoms of COVID-19 infection. 5 All of the previously mentioned facts, in turn, have made otolaryngologists even more susceptible than their counterparts. 6

The present study aimed to find if COVID-19 had a different impact on ear, nose, and throat (ENT) physicians of various categories (residents, registrars, and consultants ) regarding many aspects of the quality of life (protection, training, financial, and psychological aspects) .

Methods

Ethics

In this study, all procedures involving human participants followed the institutional research editorial boards' ethical standards, the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards.

Study Design

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study, focusing on ENT physicians

Time of the Study

We asked our participants to fill out the questionnaire within the first 5 days of March 2021.

Calculation of Sample Size

We have calculated the sample size with a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%. It revealed that we should include at least 370 doctors in our study.

Study Subjects

We included 375 ENT physicians, divided into 3 main groups. The 1st group had 125 residents, the 2nd group had 125 ENT registrars, and the 3rd group included 125 ENT consultants. They worked in insitutions such as general and university hospitals from 22 governorates of Egypt, which treated thousands of COVID-19 cases. We excluded 39 physicians who did not complete the questionnaire.

Collection of Data

We collected the data in different ways due to COVID-19 restrictions and social spacing. We used online interviews, telephone conversations, and emails. In some cases, we managed to talk to the participants in person. We have also collected the demographic data besides the required questionnaire data.

The Questionnaire

The first and second authors created this questionnaire after consultation with ENT and psychology experts. The questionnaire consisted of 20 items or questions with an answer scale consisting of three answers (yes, no, and not sure). We tried to be clear, using simple language to be understood without any help and questions that could be answered quickly. After completing the questionnaire's complete processing and production, we have created a trial test on 10 ENT physicians to detect any encounters during the questionnaire filling process. Then, we documented the final version and confirmed it for our survey. We aimed to cover different aspects regading the effect of COVID-19 on ENT practice and daily life, such as infection control and personal protective equipment (PPE) usage (questions 1, 2, and 3), dealing with patients and safety (questions 4, 6, and 20), telemedicine (items 7 and 15), online education (questions 9 and 16), medical practice effects (items 5 and 8), psychological impact (question 10), the financial impact (item 13), quarantine time effects (items 11 and 12), return to the daily activity and vaccination effect (questions 14 and 18), and future expectations (questions 17 and 19). ( Table 1 )

Table 1. The 20-item questionnaire.

| Please read and answer the following questions carefully | YES | NO | Not sure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1—During the COVID-19 crisis, have you gotten enough infection control education and training? | |||

| 2—During the COVID-19 crisis, have you gotten enough PPE supply and protection from your institution? | |||

| 3- During the COVID-19 crisis, has the usage of PPE 2 made ENT 3 examination difficult and exhausting? | |||

| 4- During the COVID-19 crisis, have you been afraid of dealing with patients? | |||

| 5- During COVID-19 1 , have you been worry about the absence of evidence-based medicine protocols, especially those related to taste and smell sensations lost? | |||

| 6-Due to COVID-19 1 , has your medical performance affected by your fear about your family members' health? | |||

| 7-During COVID-19 1 , have the telemedicine and online medical consultation been good and enough tools to deal with your patients? | |||

| 8- Owing to COVID-19 1 , have your training curve and upgrading been affected? | |||

| 9-During COVID-19 1 , have online lectures and webinars been good and enough tools for medical education? | |||

| 10- Has COVID-19 1 affected your mood and made you anxious? | |||

| 11-During the COVID-19 1 crisis, has quarantine been an excellent opportunity to rest and spend more time with your family? | |||

| 12-During the COVID-19 crisis, has quarantine been an excellent opportunity to study or finish some research work? | |||

| 13-Owing to the COVID-19 crisis, have you had an obvious financial problem? | |||

| 14-After the removal of restrictions, are you afraid of or do you have reservations about returning to your regular clinic duty? | |||

| 15-Will you continue online medical consultation and telemedicine with your patients? | |||

| 16-Will you continue online lectures and ENT webinars? | |||

| 17-Will you continue following COVID-19 1 progress news and reports? | |||

| 18-Do you think the approval of an effective vaccine will make you safe during your ENT medical practice? | |||

| 19- Do you think COVID-19 1 will have a long-term effect on your ENT career and medical practice? | |||

| 20-Owing to COVID-19 1 , do you think ENT 3 is a safe specialty? |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was perfomed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data was checked with the Shapiro-Wilks test. The numerical variables with normal distribution were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage (%). We have used the chi-squared test to compare the three answers (yes, no, and not sure) within each question's total results. We have also used the same test to compare each question's products between the three active groups. Statistically, a significant difference was present if p -value < 0.05. We have evaluated the reliability of the questionnaire by using the Goodman-Kruskal gamma coefficient. We have assessed the internal consistency of the questionnaire by using the Cronbach alpha correlation coefficient. Both coefficients were acceptable if < 1 and > zero.

Results

Clinical and Demographic Results

Regarding sex distribution, there were 327 (87.2%) male and 48 (12.8%) female subjects. They came from 33 general hospitals (55.93% of all included doctors) and 26 university hospitals (44.07% of all included doctors). In group A, the age range was 26 to 33 years, with a mean ± SD of 29 ± 1.858 years; group B's age range was 32 to 56 years, with a mean ± SD of 42.46 ± 5.279 years; and group C's age range was 38 to 65 years, with a mean ± SD of 52.6 ± 6.807 years.

Psychometric Properties Results

The Goodman-Kruskal gamma was 0.865, indicating good reliability of the questionnaire, with a strong internal consistency as the Cronbach alpha correlation coefficient was 0.967 ( Table 2 ). The effect size outcome was measured by the Cramer V test, and it was 0.648. It was valid with good responsiveness as there was a statistically significant difference among the answers to some questions (Q1, Q5, Q7, Q8, Q11, Q12, Q14, Q15) from the 3 active groups.

Table 2. Evaluation of item-by-item internal consistency.

| Item | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 | Q20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 0.455 | 0.797 | 0.578 | 0.795 | 0.626 | 0.634 | 0.440 | 0.440 | 0.465 | 0.537 | 0.829 | 0.735 | 0.818 | 0.633 | 0.271 | 0.806 | 0.889 | 0.714 | 0.524 |

| Q2 | 0.514 | 0.519 | 0.460 | 0.529 | 0.514 | 0.434 | 0.496 | 0.523 | 0.498 | 0.508 | 0.536 | 0.431 | 0.519 | 0.349 | 0.433 | 0.414 | 0.483 | 0.692 | |

| Q3 | 0.699 | 0.867 | 0.793 | 0.744 | 0.665 | 0.574 | 0.607 | 0.791 | 0.782 | 0.835 | 0.867 | 0.735 | 0.386 | 0.873 | 0.873 | 0.817 | 0.654 | ||

| Q4 | 0.567 | 0.819 | 0.471 | 0.544 | 0.754 | 0.832 | 0.666 | 0.606 | 0.783 | 0.502 | 0.511 | 0.420 | 0.515 | 0.502 | 0.742 | 0.651 | |||

| Q5 | 0.690 | 0.776 | 0.609 | 0.431 | 0.456 | 0.753 | 0.721 | 0.753 | 0.926 | 0.791 | 0.293 | 0.906 | 0.843 | 0.765 | 0.561 | ||||

| Q6 | 0.579 | 0.661 | 0.722 | 0.676 | 0.823 | 0.662 | 0.815 | 0.618 | 0.643 | 0.507 | 0.633 | 0.618 | 0.830 | 0.758 | |||||

| Q7 | 0.475 | 0.358 | 0.379 | 0.670 | 0.597 | 0.584 | 0.790 | 0.929 | 0.216 | 0.814 | 0.749 | 0.576 | 0.522 | ||||||

| Q8 | 0.413 | 0.437 | 0.555 | 0.727 | 0.633 | 0.631 | 0.510 | 0.350 | 0.626 | 0.674 | 0.643 | 0.580 | |||||||

| Q9 | 0.767 | 0.614 | 0.495 | 0.663 | 0.382 | 0.398 | 0.561 | 0.392 | 0.382 | 0.596 | 0.569 | ||||||||

| Q10 | 0.614 | 0.506 | 0.716 | 0.404 | 0.407 | 0.517 | 0.414 | 0.404 | 0.630 | 0.575 | |||||||||

| Q11 | 0.633 | 0.736 | 0.687 | 0.702 | 0.467 | 0.755 | 0.648 | 0.714 | 0.650 | ||||||||||

| Q12 | 0.644 | 0.754 | 0.586 | 0.293 | 0.781 | 0.786 | 0.639 | 0.561 | |||||||||||

| Q13 | 0.679 | 0.596 | 0.459 | 0.690 | 0.679 | 0.924 | 0.689 | ||||||||||||

| Q14 | 0.785 | 0.255 | 0.939 | 0.870 | 0.678 | 0.507 | |||||||||||||

| Q15 | 0.251 | 0.788 | 0.720 | 0.594 | 0.557 | ||||||||||||||

| Q16 | 0.263 | 0.258 | 0.437 | 0.432 | |||||||||||||||

| Q17 | 0.907 | 0.695 | 0.516 | ||||||||||||||||

| Q18 | 0.678 | 0.499 | |||||||||||||||||

| Q19 | 0.710 |

Questionnaire Results

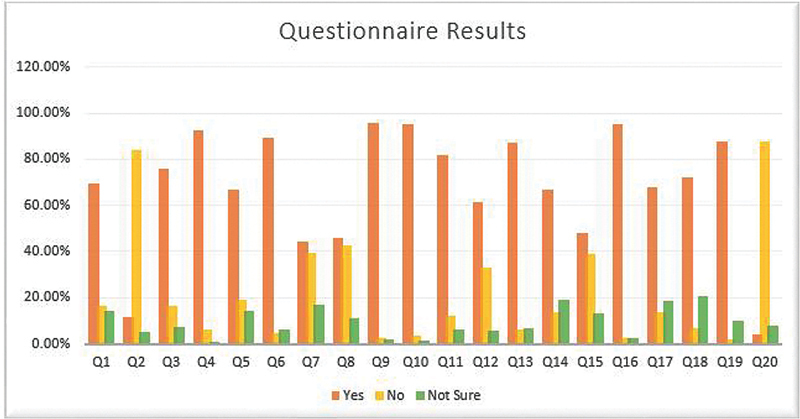

We got the results of the 20 items of the questionnaire from all included doctors of the 3 active groups; then, we compared the results of each question between all groups using the Chi-squared test. In the answers to items 1, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, and 15, there was a significant difference between the three groups ( p -value < 0.05) ( Table 3 ). We also detected a significant difference between each question (yes, no, and not sure answers). That was present in all of the 20 items of the questionnaire as the p -value was < 0.05 according to the Chi-squared test ( Table 4 ) ( Figure 1 ).

Table 3. The results of the questionnaire with a comparison of the three groups involved.

| Groups Results | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q N | Residents | Registrars | Consultants | Total | Chi-squared | P- value | |||||||||

| Yes | No | Not Sure | Yes | No | Not sure | Yes | No | Not Sure | Yes | No | Not Sure | ||||

| Q1 | N | 102 | 14 | 9 | 83 | 29 | 13 | 76 | 18 | 31 | 261 | 61 | 53 | 25.6425 | 0.00037 * |

| Per % | 81.6 | 11.2 | 7.2 | 66.4 | 23.2 | 10.4 | 60.8 | 14.4 | 24.8 | 69.6 | 16.27 | 14.13 | |||

| Q2 | N | 9 | 108 | 8 | 16 | 104 | 5 | 19 | 99 | 7 | 44 | 311 | 20 | 4.6832 | 0.32137 |

| Per% | 7.2 | 86.4 | 6.4 | 12.8 | 83.2 | 4 | 15.2 | 79.2 | 5.6 | 11.73 | 83.93 | 5.33 | |||

| Q3 | N | 92 | 23 | 10 | 95 | 22 | 8 | 98 | 17 | 10 | 285 | 62 | 28 | 1.4752 | 0.8310 |

| Per% | 73.6 | 18.4 | 8 | 76 | 17.6 | 6.4 | 78.4 | 13.6 | 8 | 76 | 16.53 | 7.47 | |||

| Q4 | N | 118 | 6 | 1 | 113 | 10 | 2 | 116 | 8 | 1 | 347 | 24 | 4 | 1.6095 | 0.8070 |

| Per% | 94.4 | 4.8 | 0.8 | 90.4 | 8 | 1.6 | 92.8 | 6.4 | 0.8 | 92.53 | 6.4 | 1.07 | |||

| Q5 | N | 68 | 39 | 18 | 87 | 24 | 14 | 96 | 8 | 21 | 251 | 71 | 53 | 26.5905 | 0.000024 * |

| Per% | 54.4 | 31.2 | 14.4 | 69.6 | 19.2 | 11.2 | 76.8 | 6.4 | 16.8 | 66.94 | 18.93 | 14.13 | |||

| Q6 | N | 106 | 9 | 10 | 111 | 5 | 9 | 117 | 3 | 5 | 334 | 17 | 24 | 5.589 | 0.232014 |

| Per% | 84.8 | 7.2 | 8 | 88.8 | 4 | 7.2 | 93.6 | 2.4 | 4 | 89.07 | 4.53 | 6.4 | |||

| Q7 | N | 24 | 74 | 27 | 53 | 48 | 24 | 88 | 25 | 12 | 165 | 147 | 63 | 67.8761 | < 0.00001 * |

| Per% | 19.2 | 59.2 | 21.6 | 42.6 | 38.4 | 9.2 | 70.4 | 20 | 9.6 | 44 | 39.2 | 16.8 | |||

| Q8 | N | 102 | 5 | 18 | 63 | 48 | 14 | 8 | 107 | 10 | 173 | 160 | 42 | 177.9758 | < 0.00001* |

| Per% | 81.6 | 4 | 14.4 | 50.4 | 38.4 | 11.2 | 6.4 | 85.6 | 8 | 46.13 | 42.67 | 11.2 | |||

| Q9 | N | 116 | 6 | 3 | 119 | 2 | 4 | 123 | 1 | 1 | 358 | 9 | 8 | 6.6234 | 0.157181 |

| Per% | 92.8 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 95.2 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 98.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 95.47 | 2.4 | 2.13 | |||

| Q10 | N | 119 | 4 | 2 | 121 | 3 | 1 | 116 | 7 | 2 | 356 | 14 | 5 | 2.3639 | 0.669164 |

| Per% | 95.2 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 96.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 92.8 | 5.6 | 1.6 | 94.93 | 3.73 | 1.33 | |||

| Q11 | N | 83 | 27 | 15 | 109 | 12 | 4 | 114 | 7 | 4 | 306 | 46 | 23 | 30.0835 | < 0.00001* |

| Per% | 66.4 | 21.6 | 12 | 87.2 | 9.6 | 3.2 | 91.2 | 5.6 | 3.2 | 81.6 | 12.27 | 6.13 | |||

| Q12 | N | 91 | 28 | 6 | 83 | 32 | 10 | 57 | 63 | 5 | 231 | 123 | 21 | 28.1102 | 0.000012* |

| Per% | 72.8 | 22.4 | 4.8 | 66.4 | 25.6 | 8 | 45.6 | 50.4 | 4 | 61.6 | 32.8 | 5.6 | |||

| Q13 | N | 112 | 4 | 9 | 109 | 11 | 5 | 105 | 8 | 12 | 326 | 23 | 26 | 6.2905 | 0.178476 |

| Per% | 89.6 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 87.2 | 8.8 | 4 | 84 | 6.4 | 9.6 | 86.93 | 6.13 | 6.93 | |||

| Q14 | N | 76 | 29 | 20 | 81 | 14 | 30 | 94 | 9 | 22 | 251 | 52 | 72 | 16.8971 | 0.002024* |

| Per% | 60.8 | 23.2 | 16 | 64.8 | 11.2 | 24 | 75.2 | 7.2 | 17.6 | 66.93 | 13.87 | 19.2 | |||

| Q15 | N | 30 | 72 | 23 | 58 | 49 | 18 | 93 | 24 | 8 | 181 | 145 | 49 | 64.0188 | < 0.00001 * |

| Per% | 24 | 57.6 | 18.4 | 46.4 | 39.2 | 14.4 | 74.4 | 19.2 | 6.4 | 48.27 | 38.67 | 13.06 | |||

| Q16 | N | 113 | 6 | 6 | 120 | 2 | 3 | 123 | 1 | 1 | 356 | 9 | 10 | 8.9105 | 0.063376 |

| Per% | 90.4 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 96 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 98.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 94.93 | 2.4 | 2.67 | |||

| Q17 | N | 81 | 16 | 28 | 83 | 20 | 22 | 91 | 15 | 19 | 255 | 51 | 69 | 3.3084 | 0.507596 |

| Per% | 64.8 | 12.8 | 22.4 | 66.4 | 16 | 17.6 | 72.8 | 12 | 15.2 | 68 | 13.6 | 18.4 | |||

| Q18 | N | 94 | 7 | 24 | 91 | 13 | 21 | 86 | 6 | 33 | 271 | 26 | 78 | 6.6693 | 0.15443 |

| Per% | 75.2 | 5.6 | 19.2 | 72.8 | 10.4 | 16.8 | 68.8 | 4.8 | 26.4 | 72.27 | 6.93 | 20.8 | |||

| Q19 | N | 109 | 3 | 13 | 113 | 3 | 9 | 107 | 2 | 16 | 329 | 8 | 38 | 2.3676 | 0.668494 |

| Per% | 87.2 | 2.4 | 10.4 | 90.4 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 85.6 | 1.6 | 12.8 | 87.74 | 2.13 | 10.13 | |||

| Q20 | N | 4 | 108 | 13 | 7 | 109 | 9 | 5 | 112 | 8 | 16 | 329 | 30 | 2.354 | 0.670951 |

| Per% | 3.2 | 86.4 | 10.4 | 5.6 | 87.2 | 7.2 | 4 | 89.6 | 6.4 | 4.26 | 87.74 | 8 | |||

Abbreviations: N, number; Per, percentage.

P -value is significant if < 0.05

Table 4. Comparison of the three answers' obtained in March 2021.

| Q | N | Answers | Chi-squared | P- value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not Sure | ||||

| Q1 | N | 261 | 61 | 53 | 222.208 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per % | 69.6 | 16.27 | 14.13 | |||

| Q2 | N | 44 | 311 | 20 | 417.456 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 11.73 | 83.93 | 5.33 | |||

| Q3 | N | 285 | 62 | 28 | 311.824 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 76 | 16.53 | 7.47 | |||

| Q4 | N | 347 | 24 | 4 | 593.008 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 92.53 | 6.4 | 1.07 | |||

| Q5 | N | 251 | 71 | 53 | 191.808 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 66.94 | 18.93 | 14.13 | |||

| Q6 | N | 334 | 17 | 24 | 524.386 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 89.07 | 4.53 | 6.4 | |||

| Q7 | N | 165 | 147 | 63 | 47.424 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 44 | 39.2 | 16.8 | |||

| Q8 | N | 173 | 160 | 42 | 83.344 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 46.13 | 42.67 | 11.2 | |||

| Q9 | N | 358 | 9 | 8 | 651.656 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 95.47 | 2.4 | 2.13 | |||

| Q10 | N | 356 | 14 | 5 | 640.656 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 94.93 | 3.73 | 1.33 | |||

| Q11 | N | 306 | 46 | 23 | 395.632 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 81.6 | 12.27 | 6.13 | |||

| Q12 | N | 231 | 123 | 21 | 176.448 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 61.6 | 32.8 | 5.6 | |||

| Q13 | N | 326 | 23 | 26 | 484.848 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 86.93 | 6.13 | 6.93 | |||

| Q14 | N | 251 | 52 | 72 | 192.112 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 66.93 | 13.87 | 19.2 | |||

| Q15 | N | 181 | 145 | 49 | 74.496 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 48.27 | 38.67 | 13.06 | |||

| Q16 | N | 356 | 9 | 10 | 640.336 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 94.93 | 2.4 | 2.67 | |||

| Q17 | N | 255 | 51 | 69 | 204.096 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 68 | 13.6 | 18.4 | |||

| Q18 | N | 271 | 26 | 78 | 266.608 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 72.27 | 6.93 | 20.8 | |||

| Q19 | N | 329 | 8 | 38 | 502.992 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 87.74 | 2.13 | 10.13 | |||

| Q20 | N | 16 | 329 | 30 | 500.176 | < 0.0001 * |

| Per% | 4.27 | 87.73 | 8 | |||

Abbreviations: N, number; Per, percentage.

P -value is significant if < 0.05

Fig. 1.

The results of the questions showing a different impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life of ear, nose, and throat physicians.

Discussion

As a trial to investigate the impact of COVID-19, we have used this research tool to reach many ENT physicians of different categories. This 20-item questionnaire covered most of life aspects and was characterized by intense internal consistency and reliability. In the following section, we have tried to analyze its results and detect variance between the three active groups.

Most of the participants have been satisfied with the efforts of the infection control and prevention departments of their institutes. These departments have made great efforts to control the spread of COVID-19, characterized by rapid and easy transmission with a high mortality rate, by offering condensed educational lectures and sessions to apply World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 policies, understand the proper usage of PPE, and deal safely with patients. 7 The satisfaction was higher among the residents who received more attention as they were on the front line during the COVID-19 crisis.

But, most of the three active groups participants were not satisfied with PPE supply and the protection given by their institutes, which has been a global problem. The shortage of PPE has made most of the health caregivers purchase their own PPE. Some of them had to use suboptimal alternatives, like trash bags, as a trial to protect themselves from COVID-19 infection. 8

Otolaryngologists are continuously vulnerable to COVID-19 infection as they are dealing with the upper respiratory tract, resulting in complete and continuous PPE usage, which has resulted in a problematic and exhausting examination of the patients, a common problem among the three active groups. Especially considering that ENT examination requires the usage of unusual instruments and endoscopes in a narrow field. 9

Most of the participants were afraid and felt unsafe when dealing with patients, and most of them had been worried about contracting COVID-19 and sprading it to their families. The unknown nature of COVID-19 could explain this, besides its high infectivity and mortality, absence of specific curative medical treatment or vaccine, insufficient PPE supply, and the increasing number of infected colleagues and relatives. The consultants have been more worried about their families due to their higher social responsibility and higher medical risk factors within this relatively old age group, making them more vulnerable to infection. All these circumstances have made ENT physicians of the three active groups think that their ENT career has been unsafe.

A fair percentage (44%) of the participants were satisfied with the online consultation and telemedicine, while 39.2% were dissatisfied with ENT practice usage. The satisfaction has been higher in the consultant group and lower in the resident group. This may be due to the difference in experience level between both categories. The importance of online consultation and telemedicine has dramatically increased during the COVID-19 crisis due to social spacing and traveling restrictions. 10 Almost half (48.27%) of the participants will continue using telemedicine consultation in their ENT medical practice, confirming this promising medical technology. 11 12

To continue otolaryngology education during the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the three active groups' participants had resorted to online courses and webinars. 13 14 The latter proved to be useful in exchanging experiences and opinions, especially those related to the recent in ENT. Online education has been prevalent during the COVID-19 era, saving money and time with little effort, and has become a good chance to utilize the quarantine time in a useful way. These advantages have encouraged most of the participants to continue their attendance.

The training curves and surgical upgrading of most residents and young registrars (66.94% of the participants) have been badly affected because they have missed the exposure to the daily clinic duties and the sharing in primary operations, or performing minor operations. 15 16 On the other hand, consultants have been more worried about the absence of evidence-based protocols regarding managing the COVID-19 related anosmia and ageusia. They have hoped to get an accurate explanation and management of those symptoms as soon as possible. 17 18

The majority of the participants have had a bad mood with anxiety. This has been a common problem for most health caregivers who have developed many psychological issues, such as depression, irritability, insomnia, low concentration, deterioration of work performance, avoidance behavior, and posttraumatic stress-related symptoms. 19 We can explain the psychological effects by a rapid increase in the death rate and the number of infected cases even with the generalized lockdown.

Most of the participants of the three active groups have had apparent financial problems. This can be explained by a significant reduction in the revenue due to all private clinics suspending and canceling all elective operations. On the other hand, expenses have increased due to the need to purchase necessary items and PPE with a marked increase in all prices. 20

Most participants have considered the quarantine time as an excellent chance to spend more time with their family members and rest physically. This was more obvious among the consultants. Their busy, tough routine daily life, without enough opportunity to spend time with the family, can explain this. On the other hand, some ENT physicians (61.6% of the participants) have taken this time to study or finish some research work.

Most participants have held many reservations and fears regarding returning to the regular ENT clinic and operative duty. These fears may be overcome by a marked decrease in the numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths, sufficient PPE supply, and the availability of specific medical treatments. Moreover, most of the participants believe the approval of an effective vaccine for COVID-19 would impressively increase the confidence level and safety when dealing with patients and overcome most of the fears, which have been higher among consultants.

Most of the participants will continue following the daily reports on the progress of COVID-19, which include the number of new COVID-19 cases and deaths, the spread rate in different countries, and the trials to develop recent specific medications and vaccinations. 21 On the other hand, most participants think that COVID-19 will have a prolonged effect on their ENT career. This effect has been thought to extend for several years and to involve many aspects of the ENT career.

Conclusions

The present study was conducted by meants of a 20-item questionnaire, which had strong consistency and good reliability. It showed a statistically significant difference regarding the impact of COVID-19 on the quality of life (protection, training, financial, and psychological aspects) of ENT physicians' in various categories (residents, registrars, and consultants), and these effects may persist for a long time.

Funding Statement

Funding The authors have no funding or financial relationships to disclose.

Conflict of Interests The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Consent to participate

Explanation and informed written consent for this research has been taken from all patients.

Consent for publication

Formal consent was signed by the patients to share and to publish their data in this research.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' Contributions

S. Z.: methodology; H. H.: idea formulation and data collection; M. M.: review writing and revision; A. M: reference collection and final revision; M. E.: formal analysis; M. B.: idea formulation and editing final draft; and H. E.: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research editorial boards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X.Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Jan 30;] Lancet 2020395(10223):497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong S WX, Tan Y K, Chia P Y. Air, Surface Environmental, and Personal Protective Equipment Contamination by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) From a Symptomatic Patient. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1610–1612. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X.Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study Lancet 2020395(10223):507–513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chun-hui L, Xun H, Meng C. Expert consensus on personal protection in different regional posts of medical institutions during novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) epidemic period. Can J Infect Control. 2020;19(03):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elsherief H, Amer M, Abdel-Hamid A S, El-Deeb M E, Negm A, Elzayat S. The Pattern of Anosmia in Non-hospitalized Patients in the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25(03):e334–e338. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1730303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ralli M, Di Stadio A, Greco A, de Vincentiis M, Polimeni A. Defining the burden of olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(07):3440–3441. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202004_20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng V CC, Wong S C, Chen J HK. Escalating infection control response to the rapidly evolving epidemiology of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to SARS-CoV-2 in Hong Kong. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(05):493–498. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou P, Huang Z, Xiao Y, Huang X, Fan X G. Protecting Chinese healthcare workers while combating the 2019 novel coronavirus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(06):745–746. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givi B, Schiff B A, Chinn S B. Safety Recommendations for Evaluation and Surgery of the Head and Neck During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146(06):579–584. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson R. Telemedicine and Telehealth: The Potential to Improve Rural Access to Care. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(06):17–18. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000520244.60138.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lurie N, Carr B G. The Role of Telehealth in the Medical Response to Disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(06):745–746. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollock K, Setzen M, Svider P F. Embracing telemedicine into your otolaryngology practice amid the COVID-19 crisis: An invited commentary. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(03):102490. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oghalai J.Collaborative Multi-Institutional Otolaryngology Residency Education Program2021, April 4. Retrieved fromhttps://sites.usc.edu/ohnscovid/

- 14.Comer B T.Consortium of Resident Otolaryngologic knowledge Attainment (CORONA) Initiative in Otolaryngology2021, April 4. Retrieved fromhttps://Entcovid.med.uky.edu

- 15.Kowalski L P, Sanabria A, Ridge J A. COVID-19 pandemic: Effects and evidence-based recommendations for otolaryngology and head and neck surgery practice. Head Neck. 2020;42(06):1259–1267. doi: 10.1002/hed.26164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ralli M, Greco A, de Vincentiis M. The Effects of the COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic Outbreak on Otolaryngology Activity in Italy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020;99(09):565–566. doi: 10.1177/0145561320923893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell C D, Millar J E, Baillie J K.Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-nCoV lung injury Lancet 2020395(10223):473–475. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30317-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lechien J R, Chiesa-Estomba C M, De Siati D R. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277(08):2251–2261. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks S K, Webster R K, Smith L E.The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence Lancet 2020395(10227):912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.COVID-19 Implications for businessAccessed March 29, 2021 at:https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/covid-19-implications-for-business

- 21.Chan A KM, Nickson C P, Rudolph J W, Lee A, Joynt G M. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(12):1579–1582. doi: 10.1111/anae.15057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.