Abstract

Introduction:

Adequate postpartum care, including the comprehensive postpartum visit, is critical for long-term maternal health and the reduction of maternal mortality, particularly for people who may lose insurance coverage postpartum. However, variation in previous estimates of postpartum visit attendance in the United States makes it difficult to assess rates of attendance and associated characteristics.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of estimates of postpartum visit attendance. We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science for articles published in English from 1995–2020 using search terms to capture postpartum visit attendance and utilization in the United States.

Results:

Eighty-eight studies were included in the analysis. Postpartum visit attendance rates varied substantially, from 24.9% to 96.5% with a mean of 72.1%. Postpartum visit attendance rates were higher in studies using patient self-report than those using administrative data. The number of articles including an estimate of postpartum visit attendance increased considerably over the study period; the majority were published in 2015 or later.

Conclusions:

Our findings suggest that increased systematic data collection efforts aligned with postpartum care guidelines and attention to postpartum visit attendance rates may help target policies to improve maternal wellbeing. Most estimates indicate that a substantial proportion of women do not attend at least one postpartum visit, potentially contributing to maternal morbidity as well as preventing a smooth transition to future well-woman care. Estimates of current postpartum visit attendance are important for informing efforts that seek to increase postpartum visit attendance rates and to improve the quality of care.

Keywords: postpartum period, postnatal care, maternal health, delivery of health care, quality of health care, United States

Introduction

Half of maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period (Petersen et al., 2019), and the postpartum period is vital in managing overall maternal health, including addressing chronic and pregnancy-related complications (Stuebe, Kendig, Oria, & Suplee, 2021; Tully, Stuebe, & Verbiest, 2017). Postpartum visit attendance has been the focus of a number of recent studies, and increasing postpartum visit utilization has been a public health goal (US Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). The postpartum visit allows providers to deliver care for any acute issues arising from pregnancy or childbirth or during the postpartum period; discuss management of chronic conditions and infant care and feeding; and engage patients in preventive care. Recent guidance from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) states that women should have contact with an obstetric care provider within 3 weeks postpartum, followed by a comprehensive postpartum visit within 12 weeks postpartum; this visit should include “a full assessment of physical, social, and psychological well-being” (Presidential Task Force of Redefining the Postpartum Visit & Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018). These guidelines also specify a number of preventive care items that should be covered, including contraception, weight loss counseling, screening for postpartum depression, and screening for tobacco use; it is also recommended that all women should be counseled to transition to a primary care provider for future well-woman care. Research on preventive care suggests that Black and Latinx individuals (vs. White) and those insured by Medicaid (vs. privately insured) are less likely to receive adequate and timely preventive care (Manuel, 2018; McMorrow, Long, & Fogel, 2015; Sambamoorthi & McAlpine, 2003; Taylor, Liu, & Howell, 2020).

Despite the importance of the comprehensive postpartum visit, research indicates that many women do not attend this visit, and that rates of attendance vary based on insurance, sociodemographic, and clinical characteristics (Bryant, Blake-Lamb, Hatoum, & Kotelchuck, 2016; Danilack, Brousseau, Paulo, Matteson, & Clark, 2019; Masho et al., 2018; Presidential Task Force of Redefining the Postpartum Visit & Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018; Thiel de Bocanegra et al., 2017). However, postpartum visit attendance estimates from prior research vary widely. For example, the recent ACOG statement notes that about 60% of women attend postpartum visits (Presidential Task Force of Redefining the Postpartum Visit & Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018), while estimates from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) place postpartum visit attendance at closer to 90% (Danilack et al., 2019). A recent systematic review narrowly focused on predictors of postpartum visit attendance found that postpartum visit attendance was higher among women with higher socioeconomic status and women who gave birth at public facilities (Wouk et al., 2020). This review – which included only a subset of the articles we include in the present study – focused exclusively on the strength of associations between women’s characteristics and postpartum visit attendance rates rather than variation in the rates themselves across studies and populations as we do here. Better understanding variation in estimates of postpartum visit attendance is important for designing interventions and policies to increase postpartum visit attendance, and for generally improving the quality of healthcare delivered during the critical postpartum period.

The goal of this study was to review and compare estimates of postpartum visit attendance in the scholarly literature. We characterized the range of estimates, the measures of postpartum visit attendance used, and the study designs and data collection methods, as well as the associations between sociodemographic characteristics, medical conditions, and postpartum visit attendance.

Material and methods

We conducted a systematic review of the literature regarding postpartum visit attendance following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). We searched PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science for articles published in English between 1995 and 2020, the most recent 25-year period, using search terms to capture postpartum visit attendance and utilization in the United States (Text A.1). Additional articles were added by searching article references and identifying newer articles citing identified articles. Duplicate articles were removed. No review protocol was registered for this study.

Identified titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were: 1) quantitative observational empirical studies that reported data on populations within the United States and described an estimate of obstetric care utilization in one year postpartum; 2) published in English; and 3) peer-reviewed publications. If the article did not clearly define a postpartum visit, it was included unless it was specified that the visit was not with an obstetric provider. The following study types were excluded: intervention studies, commentaries, review articles, study protocols, case reports, and qualitative studies.

Titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion in the review by two members of the study team, with any conflicts resolved by the first author. Full text was obtained for studies that met the screening criteria, and reviewed by two of the authors to further assess eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus.

We developed a structured form to extract data from included studies. Three members of the study team participated in data extraction, with two researchers independently extracting data from each included study. Data extracted included basic details (year published, year of data, data sources and types), study characteristics (type of study, number of participants, geographic areas, population, postpartum visit definition), and study outcomes (overall and subgroup postpartum visit attendance estimates). If multiple measures of healthcare utilization in the postpartum year were recorded at different points in time, the measure that aligns with the typical definition of a postpartum visit (i.e., 2–16 weeks postpartum) was used as the overall rate of postpartum visit attendance. If a study reported postpartum visit attendance by subgroups only (n=16), we calculated an overall rate for the study population if the article provided sufficient information to do so (e.g., numbers of participants in each subgroup). We analyzed the data by calculating frequencies and percentages of the characteristics of included studies, and we present summary statistics for postpartum visit attendance estimates of included studies by select characteristics, including the mean, interquartile range (IQR), and overall range. Summary statistics are not weighted by population size of the study in the main analysis. As a sensitivity analysis, we use all studies for which the population size is clearly reported and weight our results by the study population size to produce weighted estimates.

Quality and risk of bias assessment

For each included article, two of the authors assessed the quality of the study and risk of bias based on whether the sampling method was representative of the population being studied and the degree to which the postpartum visit measure aligns with the concept and timing of a comprehensive postpartum visit. We examined whether the postpartum visit measure 1) pertained to obstetric care specifically; 2) had a time frame consistent with what is recommended for a postpartum visit (2–16 weeks or 4 months postpartum); and 3) included an indication that the visit was a comprehensive or preventive postpartum visit rather than an acute care visit (e.g., included the words “check-up,” “routine,” “preventive” “comprehensive,” or “follow-up”).

Results

Study characteristics

After excluding duplicates, 4655 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility; full-text articles were assessed for 278 studies. Eighty-eight studies were included for data extraction (see Figure 1 for a PRISMA flow diagram, and Table A.1 for a list of all included studies). Characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1. The number of published studies including an estimate of postpartum visit attendance increased substantially over the study period; more than half of the included studies were published between 2015 and 2020. The number of participants in each study varied considerably (range 35 – 1,697,170 people), with 8.1% of studies including under 100 participants and 32.6% of studies including more than 6200 participants. 20.5% of included studies used health insurance claims data, 21.6% used electronic health record data, 21.6% derived data from medical chart review or abstraction, 34.1% used patient survey data, and 2.3% of studies used some other data source. For about half of included studies, the population was drawn from a single hospital or healthcare system. About 18% of studies had a population-based sample representative of either a state, multi-state region, or national population.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n=88).

| Study characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants† | ||

| Under 100 | 7 | 8.1 |

| 100–299 | 8 | 9.3 |

| 300–799 | 20 | 23.3 |

| 800–6200 | 23 | 26.7 |

| 6200+ | 28 | 32.6 |

| Data source | ||

| Health insurance claims | 18 | 20.5 |

| Electronic health record | 19 | 21.6 |

| Medical chart review/abstraction | 19 | 21.6 |

| Patient survey | 30 | 34.1 |

| Other | 2 | 2.3 |

| Year of publication | ||

| 1995–2000 | 2 | 2.3 |

| 2001–2005 | 7 | 8.0 |

| 2006–2010 | 10 | 11.4 |

| 2011–2015 | 22 | 25.0 |

| 2016–2020 | 47 | 53.4 |

| Study population type | ||

| Single hospital or healthcare system | 37 | 42.1 |

| Defined set of clinics | 5 | 5.7 |

| Single health plan | 16 | 18.2 |

| Population-based, single state | 7 | 8.0 |

| Population-based, multiple states | 9 | 10.2 |

| Nationally drawn | 5 | 5.7 |

| Other | 9 | 10.2 |

2 included studies did not provide a number of participants.

Study populations

Table 2 reports the populations of included studies. About 18% of studies examined Medicaid-insured populations, while 4.6% examined commercially-insured populations. Nearly a fifth of studies had populations that were predominantly from but not limited to underserved sociodemographic groups (e.g., a clinic whose patient population is largely Medicaid-insured). Some studies examined postpartum visit attendance for postpartum people with specific chronic conditions, the most common of which was diabetes (15% of studies). Seven percent of studies limited their populations to women with a specific postpartum contraceptive plan, such as long-acting reversible contraception or tubal ligation.

Table 2.

Study populations of included studies.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Medicaid insured | 16 | 18.2 |

| Commercially insured | 4 | 4.6 |

| Healthy Start† | 2 | 2.3 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 | 3.4 |

| Adolescent | 5 | 5.7 |

| Predominantly but not specifically limited to low-income, uninsured, Medicaid insured, or other underserved sociodemographic group | 15 | 17.1 |

| Diabetes | 13 | 14.8 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 2 | 2.3 |

| Obesity | 0 | 0.0 |

| Medically high risk but not single condition-specific | 4 | 4.6 |

| Preterm birth or low birthweight | 2 | 2.3 |

| Substance use disorder | 5 | 5.7 |

| People living with HIV/AIDS | 4 | 4.6 |

| Specific contraceptive plan | 6 | 6.8 |

Abbreviations: human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, AIDS

Note: Studies could be classified as having multiple population types; not all studies had one of these population types.

Healthy Start is a federally funded program created in 1991 to reduce disparities in maternal and infant health

Postpartum visit attendance estimates

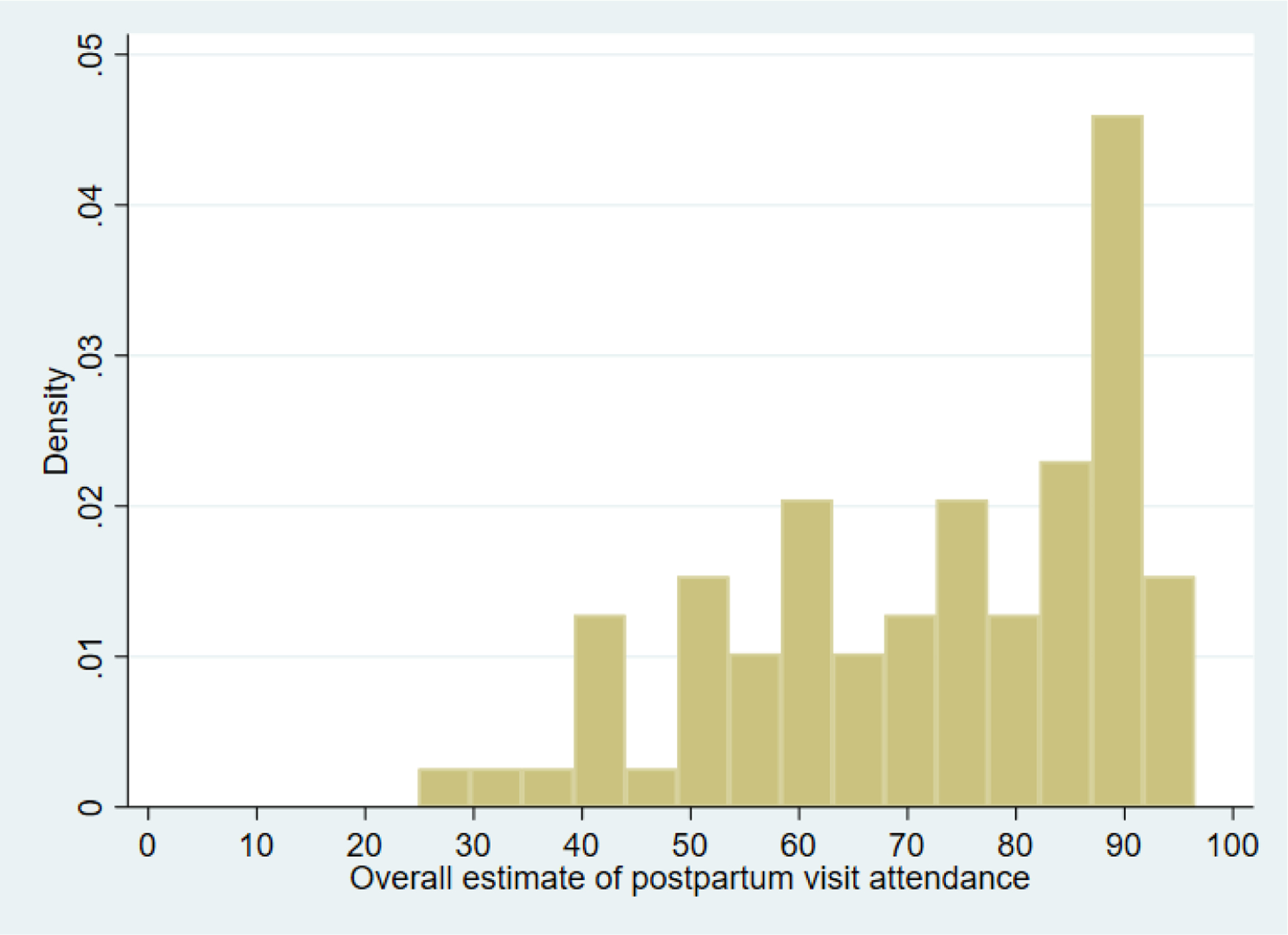

Eighty-two studies included an estimate of postpartum visit attendance for the full study population (Table 3). The remaining six studies only reported postpartum visit attendance by subpopulation, and did not provide enough information in the manuscript for our study team to calculate it manually for the overall study population. Postpartum visit attendance ranged from 24.9% to 95% (IQR: 62% - 88.9%). Mean postpartum visit attendance was 72.1% (Table 3), and the median was 74.2%. Postpartum visit attendance means, IQRs, and ranges by study characteristics and participant populations are included in Table 3. In the sensitivity analysis in which summary statistics were weighted by study population size, mean postpartum visit attendance was 62.2% (full results presented in Table A.4). A histogram of postpartum visit attendance estimates from the 82 studies is presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Postpartum visit attendance estimates by study characteristics and populations.

| Overall PPV attendance estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean percentage across studies | IQR | Range | |

| Study characteristic | ||||

| Total | ||||

| Number of participants | 82† | 72.1 | 60.3–88.2 | 24.9–96.5 |

| Under 100 | 7 | 61.7 | 52.5–71.4 | 48.0–73.4 |

| 100–299 | 6 | 70.6 | 52.3–84.5 | 40.1–95.4 |

| 300–799 | 19 | 69.4 | 61.0–82.0 | 30.0–92.9 |

| 800–6200 | 22 | 76.9 | 63.9–90.0 | 24.9–94.2 |

| 6200+ | 26 | 72.0 | 49.5–89.4 | 39.6–96.5 |

| Data source | ||||

| Health insurance claims | 18 | 56.5 | 40.3–67.1 | 24.9–85.7 |

| Electronic health record | 18 | 70.5 | 61.5–82 | 40.1–92.9 |

| Medical chart review/abstraction | 17 | 65.8 | 57.3–73.4 | 30.0–96.5 |

| Patient survey | 27 | 88 | 86.7–90.7 | 67.6–95.4 |

| Other | 2 | 66.5 | n/a | 60.1–72.8 |

| Year of publication | ||||

| 1995–2000 | 1 | 83 | n/a | n/a |

| 2001–2005 | 6 | 68.9 | 71.0–73.4 | 37.9–85.0 |

| 2006–2010 | 8 | 86.0 | 81.8–90.2 | 72.3–96.5 |

| 2011–2015 | 20 | 79.0 | 65.9–90.0 | 48.0–95.4 |

| 2016–2020 | 47 | 67.0 | 52.3–85.7 | 24.9–92.9 |

| Study population type | ||||

| Single hospital or healthcare system | 33 | 69.5 | 61.5–80.2 | 30.0–95.4 |

| Defined set of clinics | 5 | 78.9 | 73.0–87.0 | 71.4–88.1 |

| Single health plan | 16 | 62.7 | 49.4–82.0 | 40.0–96.5 |

| Population-based, single state | 5 | 90.7 | 89.6–92.9 | 86.7–94.2 |

| Population-based, multiple states | 9 | 89.4 | 88.7–90.1 | 85.9–92.3 |

| Nationally drawn | 5 | 81.1 | 72.8–90.0 | 67.6–90.1 |

| Other | 9 | 62.3 | 39.6–88.9 | 24.9–91.7 |

| Study population | ||||

| Medicaid insured | 15 | 64.7 | 49.4–82.9 | 37.9 – 85.7 |

| Commercially insured | 4 | 58.5 | 40.2–76.9 | 40.0–96.5 |

| Healthy Start | 2 | 88.8 | n/a | 86.5 – 91.0 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 | 72.5 | n/a | 71.0–73.4 |

| Adolescent | 4 | 72.7 | 66.3–79.1 | 61.5–85.9 |

| Predominantly but not specificallylimited to low-income, uninsured, Medicaid insured, or other underserved sociodemographic group | 14 | 77.1 | 71.4–86.5 | 61.5–88.9 |

| Diabetes | 12 | 70.8 | 57.8–82.5 | 39.6–96.5 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 2 | 46.3 | n/a | n/a |

| Medically high risk but not single condition-specific | 3 | 81.3 | n/a | 73.4–95.4 |

| Preterm birth or low birthweight | 2 | 68.5 | n/a | 52.5–84.5 |

| Substance use disorder | 5 | 41.6 | 37.9–42.8 | 30.0–57.3 |

| People living with HIV/AIDS | 4 | 66.3 | 54.7–78.0 | 37.9–79.9 |

| Specific contraceptive plan | 5 | 65.5 | 61.5–63.9 | 48.0–92.3 |

Abbreviations: postpartum visit, PPV; interquartile range, IQR; human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, AIDS

6 studies did not provide an estimate of postpartum visit attendance for the full study population.

Figure 2. Histogram of postpartum visit attendance estimates from included studies.

Notes: Density indicates the proportion of studies for which the estimate of postpartum visit attendance fell within the five percentage point interval defined by the width of the bar.

Associations between maternal characteristics and postpartum visit attendance rates are shown in Table A.2. Twenty studies examined unadjusted associations between race/ethnicity and postpartum visit attendance; 35% of these studies found no significant association, while 35% found that women in other racial/ethnic groups were less likely to attend a postpartum visit compared to White women. Sixteen studies reported results from multivariate analyses of the association between race/ethnicity and postpartum visit attendance; among these, 13% found that women in other racial/ethnic groups were less likely to attend a postpartum visit compared to White women, while 43% showed no significant association. Eleven studies examined unadjusted associations between insurance status and postpartum visit attendance, with 82% of these studies finding that Medicaid-insured women were less likely to attend a postpartum visit. Ten reported multivariate analyses, with 60% finding that Medicaid-insured women were less likely to attend. Six studies reported unadjusted analyses for postpartum visit attendance by chronic condition status, and 50% of these found no significant association. Ten studies reported results from multivariate analyses of the relationship between chronic condition status and postpartum visit attendance; among these, 40% found that women with a chronic condition were less likely to attend a postpartum visit.

Quality assessment

Full details of the quality assessment measures by study are available in Table A.3. The first domain of our quality assessment was study sampling method. Among the included studies, 12 studies (13.6%) used non-probability sampling methods, while 25 studies (28.4%) used population representative sampling, and 51 studies (58.0%) used all eligible cases in a defined population universe, such as all deliveries in a hospital that met certain eligibility criteria. The second domain of the quality assessment examined alignment of the study’s measure of a postpartum visit with the concept of a comprehensive postpartum visit. Twenty-nine studies (33.0%) explicitly stated that their measure of the postpartum visit was with an obstetric care provider. The majority of studies (63.6%) were likely with an obstetric care provider, but this was not explicitly stated. Three studies (3.4%) included visits to a non-obstetric care provider as well as visits to obstetric providers in their postpartum visit attendance measure. Seventy-two studies (81.8%) designated a timeframe of 2–12 weeks postpartum for their postpartum visit measure. Just under half of included studies (n=42; 47.7%) indicated that the postpartum visit measure was specific to a comprehensive or preventive postpartum visit rather than a problem visit.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we documented estimates of postpartum visit attendance in the scholarly literature over the past 25 years. There was substantial variation in postpartum visit attendance rates across studies, from 25.9% to 96.5% (mean 72.1%). The number of studies examining postpartum visit attendance increased over time; half of included studies were published in the final 5 years of the 25-year-period, possibly reflecting growing attention to the importance of postpartum care for ongoing maternal health.

Many studies lacked clarity in their definition of the postpartum visit. We found that only half of studies specified that the visit was routine, preventive, or a check-up, which means that some studies may be capturing postpartum acute care visits and including these in their postpartum visit attendance estimates. The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure for postpartum care is commonly used in administrative data sets, but this measure includes any visit for postpartum care, rather than specifically measuring comprehensive postpartum visits (“Prenatal and Postpartum Care (PPC),” n.d.). Additionally, it is challenging with current data collection strategies to determine whether a postpartum visit includes all of the care that should be delivered in a comprehensive postpartum visit. Recent studies found that many recommended services are not provided at a large proportion of postpartum visits (Attanasio, Ranchoff, & Geissler, 2021; Geissler, Ranchoff, Cooper, & Attanasio, 2020), highlighting the necessity of improving care provision during this critical period.

Understanding how much variation there is and what factors influence postpartum visit attendance rates across studies is important for developing policy interventions to improve these rates. We find substantial variation, which is driven in large part by differences in the type of data collection and partially due to differences in the included population of postpartum women. Few studies were population-based, and there is substantial overlap between data collection modality and population-based studies – specifically, the PRAMS survey is the most consistently collected source of population-based data. Additionally, self-reported postpartum visit attendance is higher than postpartum visit attendance based on administrative data sources such as medical chart abstraction or claims. The fact that mean postpartum visit attendance was 10 percentage points lower when we weighted studies by study population size partly reflects this – most of the largest studies included in this review (with populations in the hundreds of thousands) used claims data, and estimates of postpartum visit attendance from claims data tend to be lower.

Differences in attendance rate by data type may be explained by several factors. First, self-reported attendance may be higher due to social desirability bias. Alternatively, women may report visits on surveys that would not be counted as a comprehensive postpartum visit through other data collection methods. A recent study comparing postpartum utilization in PRAMS and Medicaid claims for the same women in Wisconsin found substantial differences in postpartum visit attendance on these two measures, with only 40% of women with a postpartum visit according to the HEDIS definition, versus 90.5% reporting a postpartum visit on PRAMS. These differences were largely driven by healthcare received in the first two weeks postpartum, which are not counted in the standard HEDIS measure. However, nearly 10% of women who reported a postpartum visit in PRAMS had no Medicaid claims in the 12 weeks postpartum, suggesting that over-reporting in self-report accounts for at least some of this difference (DeSisto et al., 2021).

It is also possible that studies using medical records could be missing women who attended a postpartum visit at a healthcare system different from where they received their prenatal care or had their birth. However, this seems unlikely to account for the extent of the variation we observed, particularly since studies using health insurance claims data – which include visits across all healthcare organizations – also found lower rates of postpartum visit attendance.

Consistent with a previous review by Wouk and colleagues (Wouk et al., 2020), we found that in many studies, women from marginalized social groups were less likely to attend postpartum visits. However, a number of studies did not find expected associations between women’s characteristics and postpartum visit attendance, particularly with regard to race/ethnicity. Medicaid insurance, however, predicted lower postpartum visit attendance compared to private insurance in most studies that assessed this comparison. Understanding which factors make women less likely to attend postpartum visits is important for developing policy interventions that address barriers to attendance.

Prior research on lower preventive care receipt for women with Medicaid relative to women with private insurance suggests that these disparities largely reflect reduced access to health care for women with Medicaid, with mixed findings on visit-level differences by insurance type (Geissler et al., 2020; McMorrow, Kenney, & Goin, 2014; McMorrow et al., 2015). Nationally, pregnancy-related Medicaid eligibility ends after 60 days postpartum, so individuals with a Medicaid-covered birth may have a briefer window to receive a comprehensive postpartum visit before their coverage ends, making this visit even more urgent for this population. Postpartum visit attendance may have been impacted by the Affordable Care Act, which reduced postpartum uninsurance due to Medicaid expansion (for women living in expansion states) and increased access to subsidized coverage through Marketplace plans (Daw, Winkelman, Dalton, Kozhimannil, & Admon, 2020). However, rates of insurance disruption postpartum have continued to be high even after ACA implementation (Daw, Kozhimannil, & Admon, 2019). More recently, the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act gave states the option to continue Medicaid coverage through one year postpartum (Ranji, Gomez, & Salganicoff, 2021). While 19 states have taken some action to date to extend coverage (Kaiser Family Foundation, n.d.), it is not anticipated that all states will implement this option.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. First, we included studies published over a 25-year time period, so there could have been variation over time in postpartum visit attendance that we did not directly assess. Second, a substantial proportion of studies used non-representative sampling; while we identified these studies in the quality assessment, the range of postpartum visit estimates that we present in the results includes studies that are not necessarily representative of all postpartum women. Finally, we chose to limit our review to observational studies because our goal was to compare estimates of postpartum visit attendance in typical conditions, and many intervention studies that reported postpartum visit attendance either had the explicit goal of increasing postpartum visit attendance or could plausibly have affected it.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Overall, our results highlight a need for systematic data collection efforts that align with new guidelines for postpartum care, including not only whether a comprehensive postpartum visit has occurred but also whether recommended services and counseling were delivered. Most estimates suggest that a substantial proportion of birthing people do not attend at least one postpartum visit, potentially contributing to maternal morbidity as well as preventing a smooth transition to future well-woman care. However, whether it is 10% of birthing people versus nearly half who are not receiving postpartum care has important policy implications in terms of the extent and targeting of the outreach efforts that are needed. Additionally, this review only assessed estimates of postpartum visit attendance, not whether the visit included the items recommended in current guidelines. Accurate and consistent estimates of current postpartum visit attendance are critical for informing efforts that seek to increase postpartum visit rates and to improve the quality of care in the postpartum period (Geissler et al., 2020; Interrante, Admon, Stuebe, & Kozhimannil, 2022).

Conclusions

Across studies included in this systematic review, there was wide variation in estimates of postpartum visit attendance, which may be attributable to variation in study populations, differing definitions of the postpartum visit, and differing data collection modalities (e.g., medical chart review, survey, claims). These findings support recent calls for more systematic data collection efforts that are attentive to postpartum visit content and responsive to new guidelines for postpartum care.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (Grant Number R56HL151636). The funder had no role in study design, analysis, interpretation of data, or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Biography

Laura B. Attanasio, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Health Policy and Management, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research examines issues of quality, equity and decision making in perinatal healthcare.

Brittany L. Ranchoff, MPH, is a doctoral student in Health Policy and Management, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research interests include access to care, perinatal experiences, and health outcomes and utilization in the perinatal period.

Michael I. Cooper, BBA, is a medical student at Tufts University School of Medicine and a Departmental Assistant in the Department of Health Promotion and Policy, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst. His research interests include healthcare quality, delivery, and policy.

Kimberley H. Geissler, PhD, is an Associate Professor in Health Policy and Management, Department of Health Promotion and Policy, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her research examines factors affecting access to and coordination of health care.

Table A.1.

Characteristics of each included study.

| Citation | Number of participants | Data source | Study population type | Sampling | Overall PPV attendance estimate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum care visits--11 states and New York City, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(50):1312–1316. | 18,558 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 88.7 |

| Adhikari EH, Yule CS, Roberts SW, et al. Factors Associated with Postpartum Loss to Follow-Up and Detectable Viremia After Delivery Among Pregnant Women Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(1):14–20.§ | 613 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 79.9 |

| Adia AC, Matos QP, Monteiro K, Kim HH. The Association Between Postpartum Healthcare Encounters and Contraceptive Use among Rhode Island Mothers, 2012–2015. R I Med J (2013). 2018;101(3):29–32. | 4,542 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | 92.9 |

| Arora KS, Ascha M, Wilkinson B, et al. Association between neighborhood disadvantage and fulfillment of desired postpartum sterilization. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1440.§ | 1,332 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 63.9 |

| Attanasio L, Kozhimannil KB. Health Care Engagement and Follow-up After Perceived Discrimination in Maternity Care. Med Care. 2017;55(9):830–833. | 2,400 | Patient survey | Nationally drawn | Population representative sample | 90.1 |

| Battarbee AN, Yee LM. Barriers to Postpartum Follow-Up and Glucose Tolerance Testing in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Am J Perinatol. 2018;35(4):354–360. | 683 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 82.0 |

| Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression - United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):575–581. | 32,659 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 90.1 |

| Bennett WL, Chang HY, Levine DM, et al. Utilization of primary and obstetric care after medically complicated pregnancies: an analysis of medical claims data. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(4):636–645.§ | 37,751 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 60.3 |

| Bensussen-Walls W, Saewyc EM. Teen-focused care versus adult-focused care for the high-risk pregnant adolescent: an outcomes evaluation. Public Health Nurs. 2001;18(6):424–435.‡ | 106 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | -- |

| Bernstein JA, Quinn E, Ameli O, et al. Follow-up after gestational diabetes: a fixable gap in women’s preventive healthcare. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000445. | 12,622 | Health insurance claims | Other | All eligible cases in universe | 39.6 |

| Bromley E, Nunes A, Phipps MG. Disparities in pregnancy healthcare utilization between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women in Rhode Island. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(8):1576–1582.‡ | 14,059 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | -- |

| Bryant AS, Haas JS, McElrath TF, McCormick MC. Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in healthy start project areas. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(6):511–516. | 1,637 | Patient survey | Other | Population representative sample | 86.5 |

| Bryant A, Blake-Lamb T, Hatoum I, Kotelchuck M. Women’s Use of Health Care in the First 2 Years Postpartum: Occurrence and Correlates. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(Suppl 1):81–91. | 6,216 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 87.4 |

| Buchberg MK, Fletcher FE, Vidrine DJ, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding barriers to postpartum retention in care among low-income, HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(3):126–132. | 35 | Electronic Health Record | Defined set of clinics but more than 1 | Non-probability sampling | 71.4 |

| Chung EK, Mathew L, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Culhane JF. Continuous source of care among young underserved children: associated characteristics and use of recommended parenting practices. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(1):36–42. | 1,670 | Patient survey | Defined set of clinics but more than 1 | Non-probability sampling | 87.0 |

| Clements KM, Mitra M, Zhang J, Parish SL. Postpartum Health Care Among Women With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):437–444.§ | 3,848 | Health insurance claims | Other | All eligible cases in universe | 24.9 |

| Coleman-Minahan K, Aiken ARA, Potter JE. Prevalence and Predictors of Prenatal and Postpartum Contraceptive Counseling in Two Texas Cities. Womens Health Issues. 2017;27(6):707–714. | 613 | Patient survey | Defined set of clinics but more than 1 | Non-probability sampling | 88.1 |

| Cope AG, Mara KC, Weaver AL, Casey PM. Postpartum Contraception Usage Among Somali Women in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(4):762–769.§ | 634 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 92.9 |

| D’Angelo D, Williams L, Morrow B, et al. Preconception and interconception health status of women who recently gave birth to a live-born infant--Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 26 reporting areas, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56(10):1–35.† | Not stated | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 89.3 |

| Danilack VA, Brousseau EC, Paulo BA, Matteson KA, Clark MA. Characteristics of women without a postpartum checkup among PRAMS participants, 2009–2011. Matern Child Health J. 2019;23(7):903–909. | 64,952 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 89.4 |

| Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, Herrlich A. Major Survey Findings of Listening to Mothers(SM) III: Pregnancy and Birth: Report of the Third National U.S. Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences. J Perinat Educ. 2014;23(1):9–16. | 1,072 | Patient survey | Nationally drawn | Population representative sample | 90.0 |

| DeSisto CL, Rohan A, Handler A, Awadalla SS, Johnson T, Rankin K. The Effect of Continuous Versus Pregnancy-Only Medicaid Eligibility on Routine Postpartum Care in Wisconsin, 2011–2015. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24(9):1138–1150.§ | 105,718 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 85.7 |

| DiBari JN, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Use of postpartum care: predictors and barriers. J Pregnancy. 2014;2014:530769. | 4,075 | Patient survey | Other | Population representative sample | 91.7 |

| Dietz PM, Vesco KK, Callaghan WM, et al. Postpartum screening for diabetes after a gestational diabetes mellitus-affected pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):868–874.§ | 36,251 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 96.5 |

| Dude A, Matulich M, Estevez S, Liu LY, Yee LM. Disparities in Postpartum Contraceptive Counseling and Provision Among Mothers of Preterm Infants. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(5):676–683. | 207 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 84.5 |

| Eggleston EM, LeCates RF, Zhang F, Wharam JF, Ross-Degnan D, Oken E. Variation in Postpartum Glycemic Screening in Women With a History of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):159–167. | 32,253 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 40.0 |

| Ehrenthal DB, Maiden K, Rogers S, Ball A. Postpartum healthcare after gestational diabetes and hypertension. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(9):760–764. | 249 | Patient survey | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 95.4 |

| Ehrenthal DB, Gelinas K, Paul DA, et al. Postpartum Emergency Department Visits and Inpatient Readmissions in a Medicaid Population of Mothers. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2017;26(9):984–991. | 4,077 | Health insurance claims | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 67.1 |

| Fabiyi CA, Reid LD, Mistry KB. Postpartum Health Care Use After Gestational Diabetes and Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(8):1116–1123. | 304 | Patient survey | Nationally drawn | Population representative sample | 67.6 |

| Farr SL, Denk CE, Dahms EW, Dietz PM. Evaluating universal education and screening for postpartum depression using population-based data. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(8):657–663. | 2,012 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | 86.7 |

| Galvin SL, Ramage M, Leiner C, Sullivan MH, Fagan EB. A Cohort Comparison of Differences Between Regional and Buncombe County Patients of a Comprehensive Perinatal Substance Use Disorders Program in Western North Carolina. N C Med J. 2020a;81(3):157–165.§ | 608 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Other | All eligible cases in universe | 57.3 |

| Galvin SL, Ramage M, Mazure E, Coulson CC. The association of cannabis use late in pregnancy with engagement and retention in perinatal substance use disorder care for opioid use disorder: A cohort comparison. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020b;117:108098.§ | 472 | Electronic Health Record | Other | All eligible cases in universe | 42.8 |

| Glass TL, Tucker K, Stewart R, Baker TE, Kauffman RP. Infant feeding and contraceptive practices among adolescents with a high teen pregnancy rate: a 3-year retrospective study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(9):1659–1663. | 543 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 72.3 |

| Haight SC, Ko JY, Yogman MW, Farr SL. Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Screening Opportunities at Health Care Encounters. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(5):731–738. | 23,990 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 90.7 |

| Hale NL, Probst JC, Liu J, Martin AB, Bennett KJ, Glover S. Postpartum screening for diabetes among Medicaid-eligible South Carolina women with gestational diabetes. Womens Health Issues. 2012;22(2):e163–169. | 6,239 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 82.9 |

| Harney C, Dude A, Haider S. Factors associated with short interpregnancy interval in women who plan postpartum LARC: a retrospective study. Contraception. 2017;95(3):245–250. | 3,553 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 62.0 |

| Harris A, Chang HY, Wang L, et al. Emergency Room Utilization After Medically Complicated Pregnancies: A Medicaid Claims Analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(9):745–754. | 26,074 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 55.8 |

| Harrison MS, Zucker R, Scarbro S, Sevick C, Sheeder J, Davidson AJ. Postpartum Contraceptive Use Among Denver-Based Adolescents and Young Adults: Association with Subsequent Repeat Delivery. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2020;33(4):393–397.e391. | 4,068 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 61.5 |

| Herrick CJ, Keller MR, Trolard AM, Cooper BP, Olsen MA, Colditz GA. Postpartum diabetes screening among low income women with gestational diabetes in Missouri 2010–2015. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):148. | 1,078 | Electronic Health Record | Defined set of clinics but more than 1 | All eligible cases in universe | 73.0 |

| Ho J, Bachman-Carter K, Thorkelson S, et al. Glycemic control and healthcare utilization following pregnancy among women with pre-existing diabetes in Navajo Nation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):629 | 82 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 61.0 |

| Hulsey TM, Laken M, Miller V, Ager J. The influence of attitudes about unintended pregnancy on use of prenatal and postpartum care. J Perinatol. 2000;20(8 Pt 1):513–519. | 319 | Patient survey | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 83.0 |

| Jones ME, Kubelka S, Bond ML. Acculturation status, birth outcomes, and family planning compliance among Hispanic teens. J Sch Nurs. 2001;17(2):83–89. | 63 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 71.0 |

| Jones ME, Bond ML, Gardner SH, Hernandez MC. A call to action. Acculturation level and family-planning patterns of Hispanic immigrant women. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2002a;27(1):26–32; quiz 33. | 376 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 73.0 |

| Jones ME, Bercier O, Hayes AL, Wentrcek P, Bond ML. Family planning patterns and acculturation level of high-risk, pregnant Hispanic women. J Nurs Care Qual. 2002b;16(4):46–55. | 98 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | 73.4 |

| Kentoffio K, Berkowitz SA, Atlas SJ, Oo SA, Percac-Lima S. Use of maternal health services: comparing refugee, immigrant and US-born populations. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(12):2494–2501.§ | 763 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 68.9 |

| Kim C, Tabaei BP, Burke R, et al. Missed opportunities for type 2 diabetes mellitus screening among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1643–1648.‡ | 533 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | -- |

| Kotha A, Chen BA, Lewis L, Dunn S, Himes KP, Krans EE. Prenatal intent and postpartum receipt of long-acting reversible contraception among women receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder. Contraception. 2019;99(1):36–41.§ | 791 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 30.0 |

| Kozhimannil KB, Huskamp HA, Graves AJ, Soumerai SB, Ross-Degnan D, Wharam JF. High-deductible health plans and costs and utilization of maternity care. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):e17–25.§ | 2,409 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 57.2 |

| Krans EE, Bobby S, England M, et al. The Pregnancy Recovery Center: A women-centered treatment program for pregnant and postpartum women with opioid use disorder. Addict Behav. 2018;86:124–129.§ | 248 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 40.1 |

| Leonard SA, Gee D, Zhu Y, Crespi CM, Whaley SE. Associations between preterm birth, low birth weight, and postpartum health in a predominantly Hispanic WIC population. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(6):499–505. | 1,420 | Patient survey | Other | Population representative sample | 88.9 |

| Levi E, Cantillo E, Ades V, Banks E, Murthy A. Immediate postplacental IUD insertion at cesarean delivery: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2012;86(2):102–105. | 90 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 48.0 |

| Levine LD, Nkonde-Price C, Limaye M, Srinivas SK. Factors associated with postpartum follow-up and persistent hypertension among women with severe preeclampsia. J Perinatol. 2016;36(12):1079–1082. | 193 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 52.3 |

| Lewey J, Levine LD, Yang L, Triebwasser JE, Groeneveld PW. Patterns of Postpartum Ambulatory Care Follow-up Care Among Women With Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020;9(17):e016357.§ | 566,059 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 40.3 |

| Lu MC, Prentice J. The postpartum visit: risk factors for nonuse and association with breast-feeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1329–1336. | 9,953 | Patient survey | Nationally drawn | Population representative sample | 85.0 |

| Masho SW, Cha S, Charles R, et al. Postpartum Visit Attendance Increases the Use of Modern Contraceptives. J Pregnancy. 2016;2016:2058127. | 24,619 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 49.3 |

| Masho SW, Cha S, Karjane N, et al. Correlates of Postpartum Visits Among Medicaid Recipients: An Analysis Using Claims Data from a Managed Care Organization. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(6):836–843. | 25,692 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 49.5 |

| McCloskey L, Bernstein J, Winter M, Iverson R, Lee-Parritz A. Follow-up of gestational diabetes mellitus in an urban safety net hospital: missed opportunities to launch preventive care for women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(4):327–334. | 415 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 80.2 |

| Meade CM, Badell M, Hackett S, et al. HIV Care Continuum among Postpartum Women Living with HIV in Atlanta. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2019;2019:8161495. | 245 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 76.0 |

| Mercier RJ, Burcher TA, Horowitz R, Wolf A. Differences in Breastfeeding Among Medicaid and Commercially Insured Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13(4):286–291. | 656 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 61.0 |

| Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, Iezzoni LI, Smeltzer SC, Long-Bellil LM. Maternal Characteristics, Pregnancy Complications, and Adverse Birth Outcomes Among Women With Disabilities. Med Care. 2015;53(12):1027–1032.‡ | 13,361 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | -- |

| Morgan I, Hughes ME, Belcher H, Holmes L, Jr. Maternal Sociodemographic Characteristics, Experiences and Health Behaviors Associated with Postpartum Care Utilization: Evidence from Maryland PRAMS Dataset, 2012–2013. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(4):589–598. | 2,204 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | 89.6 |

| Morris J, Ascha M, Wilkinson B, et al. Desired Sterilization Procedure at the Time of Cesarean Delivery According to Insurance Status. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(6):1171–1177.§ | 481 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 61.5 |

| Norton PJ, Mosley M, McBride DG, Garikapaty V. Factors in Accessing Routine Health Care: Mental Health and Postpartum Mothers. Mo Med. 2019;116(4):325–330. | 10,513 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | 90.0 |

| Ortiz FM, Jimenez EY, Boursaw B, Huttlinger K. Postpartum Care for Women with Gestational Diabetes. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2016;41(2):116–122. |

97 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 54.6 |

| Oza-Frank R. Postpartum diabetes testing among women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus: PRAMS 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):729–736. | 575 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 90.0 |

| Parekh N, Jarlenski M, Kelley D. Prenatal and Postpartum Care Disparities in a Large Medicaid Program. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(3):429–437. | 12,228 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | Population representative sample | 61.0 |

| Rankin KM, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, Handler A. Healthcare Utilization in the Postpartum Period Among Illinois Women with Medicaid Paid Claims for Delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(Suppl 1):144–153. | 55,577 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 81.1 |

| Robbins CL, Zapata LB, Farr SL, et al. Core state preconception health indicators - pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system and behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(3):1–62.† | Not stated | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 88.2 |

| Rosenbach M, O’Neil S, Cook B, Trebino L, Walker DK. Characteristics, access, utilization, satisfaction, and outcomes of healthy start participants in eight sites. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):666–679. | 1,056 | Patient survey | Other | Population representative sample | 91.0 |

| Rosenthal EW, Easter SR, Morton-Eggleston E, Dutton C, Zera C. Contraception and postpartum follow-up in patients with gestational diabetes. Contraception. 2017;95(4):431–433. | 404 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 73.0 |

| Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson CL, Welch HG, Carpenter MW. Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(6):1456–1462. | 344 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 77.0 |

| Schwarz EB, Braughton MY, Riedel JC, et al. Postpartum care and contraception provided to women with gestational and preconception diabetes in California’s Medicaid program. Contraception. 2017;96(6):432–438.§ | 199,860 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 49.4 |

| Shi L, Stevens GD, Wulu JT, Jr., Politzer RM, Xu J. America’s Health Centers: reducing racial and ethnic disparities in perinatal care and birth outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1881–1901. | 555,557 | Other | Nationally drawn | All eligible cases in universe | 72.8 |

| Shim JY, Stark EL, Ross CM, Miller ES. Multivariable Analysis of the Association between Antenatal Depressive Symptomatology and Postpartum Visit Attendance. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(10):1009–1013. | 2,870 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 80.3 |

| Sidebottom A, Vacquier M, LaRusso E, Erickson D, Hardeman R. Perinatal depression screening practices in a large health system: identifying current state and assessing opportunities to provide more equitable care. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2021;24(1):133–144. |

7,548 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 91.4 |

| Stone SL, Diop H, Declercq E, Cabral HJ, Fox MP, Wise LA. Stressful events during pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(5):384–393. | 5,395 | Patient survey | Population-based, single state | Population representative sample | 94.2 |

| Taylor YJ, Liu TL, Howell EA. Insurance Differences in Preventive Care Use and Adverse Birth Outcomes Among Pregnant Women in a Medicaid Nonexpansion State: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(1):29–37. | 9,613 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 67.9 |

| Thiel de Bocanegra H, Chang R, Menz M, Howell M, Darney P. Postpartum contraception in publicly-funded programs and interpregnancy intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):296–303. | 117,644 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 85.0 |

| Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, Schwarz EB. Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California’s Medicaid program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(1):47.e41–47.e47. |

199,860 | Health insurance claims | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 49.4 |

| Thurman AR, Janecek T. One-year follow-up of women with unfulfilled postpartum sterilization requests. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1071–1077.‡ | 1,460 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | -- |

| Upadhya KK, Burke AE, Marcell AV, Mistry K, Cheng TL. Contraceptive service needs of women with young children presenting for pediatric care. Contraception. 2015;92(5):508–512. | 291 | Patient survey | Defined set of clinics but more than 1 | Non-probability sampling | 75.0 |

| Vani K, Facco FL, Himes KP. Pregnancy after periviable birth: making the case for innovative delivery of interpregnancy care. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(21):3577–3580. | 60 | Medical chart review/abstraction | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 52.5 |

| Warner LA, Wei W, McSpiritt E, Sambamoorthi U, Crystal S. Ante- and postpartum substance abuse treatment and antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected women on Medicaid. J Am Med Womens Assoc (1972). 2003;58(3):143–153. | 346 | Health insurance claims | Other | All eligible cases in universe | 37.9 |

| Weir S, Posner HE, Zhang J, Willis G, Baxter JD, Clark RE. Predictors of prenatal and postpartum care adequacy in a medicaid managed care population. Womens Health Issues. 2011;21(4):277–285. | 1,858 | Other | Single health plan | All eligible cases in universe | 60.1 |

| Wilcox A, Levi EE, Garrett JM. Predictors of Non-Attendance to the Postpartum Follow-up Visit. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(Suppl 1):22–27. | 3,441 | Electronic Health Record | Single hospital/healthcare system | All eligible cases in universe | 67.0 |

| Wilson EK, Fowler CI, Koo HP. Postpartum contraceptive use among adolescent mothers in seven states. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):278–283. | 3,207 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 85.9 |

| York R, Tulman L, Brown K. Postnatal care in low-income urban African American women: relationship to level of prenatal care sought. J Perinatol. 2000;20(1):34–40.‡ | 297 | Patient survey | Single hospital/healthcare system | Non-probability sampling | -- |

| Zapata LB, Murtaza S, Whiteman MK, et al. Contraceptive counseling and postpartum contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(2):171.e171–178. | 9,536 | Patient survey | Population-based, multiple states | Population representative sample | 92.3 |

Abbreviations: postpartum visit, PPV

Sample size not provided for postpartum visit attendance population

Overall postpartum visit attendance rate not provided and could not be calculated based on the information presented in the manuscript

Authors calculated the overall postpartum visit attendance rate based on information in manuscript

Table A.2.

Association of women’s characteristics with postpartum visit attendance

| Results from bivariate analyses | Results from multivariate analyses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies comparing postpartum visit attendance by… | N | % | N | % |

| Race/ethnicity | 20 | -- | 16 | -- |

| No significant association | 7 | 35.0 | 7 | 43.8 |

| Visit attendance lower in another racial/ethnic group (vs. White) | 1 | 5.0 | 3 | 18.8 |

| Visit attendance higher in another racial/ethnic group (vs. White) | 7 | 35.0 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Different associations by specific racial/ethnic group† | 5 | 25.0 | 4 | 25.0 |

| Insurance status | 11 | -- | 10 | -- |

| No significant association | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Medicaid-insured more likely to attend visit than privately insured | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Medicaid-insured less likely to attend visit than privately insured | 9 | 81.8 | 6 | 60.0 |

| Not comparable (different reference group)‡ | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Chronic condition status | 6 | -- | 10 | -- |

| No significant association | 3 | 50.0 | 2 | 20.0 |

| Women with chronic condition more likely to attend visit | 1 | 16.7 | 3 | 30.0 |

| Women with chronic condition less likely to attend visit | 2 | 33.3 | 4 | 40.0 |

| Different associations by specific chronic condition group | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 10.0 |

Note: Percentages for each category may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

For example, Black women are more likely to attend a postpartum visit than White women, and Latinx women are less likely to attend.

For example, uninsured or unknown insurance status is the reference group.

Table A.3.

Quality assessment measures for included studies.

| Postpartum visit measure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Authors (year) | Time aligns with comprehensive postpartum visit | Specific to obstetric care† | Specifies comprehensive/preventive postpartum visit‡ |

| No Author (2007) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Adhikari et al. (2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Adia et al. (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Arora et al. (2020) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Attanasio and Kozhimannil (2017) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Battarbee and Yee (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Bauman et al. (2020) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Bennett et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Bensussen-Walls and Saewyc (2001) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Bernstein et al. (2017) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Bromley et al. (2012) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Bryant et al. (2006) | No | Yes | No |

| Bryant et al. (2016) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Buchberg et al. (2015) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Chung et al. (2008) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Clements et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Coleman-Minahan et al. (2017) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Cope et al. (2019) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| D’Angelo et al. (2007) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Danilack et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Declercq et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | No |

| DeSisto et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No |

| DiBari et al. (2014) | No | Ambiguous | No |

| Dietz et al. (2008) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Dude et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Eggleston et al. (2016) | Yes | No | No |

| Ehrenthal et al. (2014) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Ehrenthal et al. (2017) | Yes | No | No |

| Fabiyi et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Farr et al. (2014) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Galvin et al. (2020a) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Galvin et al. (2020b) | No | Yes | No |

| Glass et al. (2010) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Haight et al. (2020) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Hale et al. (2012) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Harney et al. (2017) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Harris et al. (2015) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Harrison et al. (2020) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Herrick et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Ho et al. (2018) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hulsey et al. (2000) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Jones et al. (2001) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Jones et al. (2002a) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Jones et al. (2002b) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Kentoffio et al. (2016) | No | Yes | No |

| Kim et al. (2006) | No | Yes | No |

| Kotha et al. (2019) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Kozhimannil et al. (2011) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Krans et al. (2018) | No | Ambiguous | No |

| Leonard et al. (2014) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Levi et al. (2012) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Levine et al. (2016) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Lewey et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Lu and Prentice (2002) | No | No | No |

| Masho et al. (2016) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Masho et al. (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| McCloskey et al. (2014) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Meade et al. (2019) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mercier et al. (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Mitra et al. (2015) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Morgan et al. (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Morris et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Norton et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Ortiz et al. (2016) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Oza-Frank (2014) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Parekh et al. (2018) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Rankin et al. (2016) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Robbins et al. (2014) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Rosenbach et al. (2010) | No | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Rosenthal et al. (2017) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Russell et al. (2006) | No | Yes | No |

| Schwarz et al. (2017) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Shi et al. (2004) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Shim et al. (2019) | No | Ambiguous | No |

| Sidebottom et al. (2020) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Stone et al. (2015) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Taylor et al. (2020) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Thiel de Bocanegra et al. (2013) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Thiel de Bocanegra et al. (2017) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Thurman and Janecek (2010) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Upadhya et al. (2015) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Vani et al. (2019) | Yes | Ambiguous | No |

| Warner et al. (2003) | No | Yes | No |

| Weir et al. (2011) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Wilcox et al. (2016) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Wilson et al. (2013) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| York et al. (2000) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

| Zapata et al. (2015) | Yes | Ambiguous | Yes |

Specific to obstetric care needed to mention the provider including the following language to be considered “yes”: “maternity care provider,” “obstetric provider,” “prenatal care provider,” or naming specific maternity care provider types (i.e., OB/GYN, midwife, etc.). Additionally, we considered it specific to obstetric care if it was specified that the visit occurred at the obstetric clinic. Measures were considered “no” if they included any type of office visit as a postpartum visit. Measures were considered “ambiguous” if obstetrics was not mentioned, but it was also not explicitly mentioned that visits to other provider types were included.

To be considered “yes,” definition included the following language: “check-up,” “routine,” “preventive,” “comprehensive,” or “follow-up,” or if the authors only used the ICD-9 code of V24 and/or ICD-10 code of Z39 and CPT code of “59430.”

Table A.4.

Postpartum visit attendance estimates by study characteristics and populations, weighted by study population size.

| Overall PPV attendance estimate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | Weighted mean percentage across studies | Weighted IQR | |

| Study characteristic | |||

| Total | 80† | 62.2 | 40.3–72.8 |

| Number of participants | |||

| Under 100 | 7 | 60.8 | 52.5–71.4 |

| 100–299 | 6 | 71.0 | 52.3–84.5 |

| 300–799 | 19 | 69.1 | 61.0–82.0 |

| 800–6200 | 22 | 75.8 | 62.0–91.0 |

| 6200+ | 26 | 61.8 | 40.3–72.8 |

| Data source | |||

| Claims | 18 | 53.0 | 40.3–55.8 |

| Electronic Health Record | 18 | 75.5 | 67.0–87.4 |

| Medical chart review/abstraction | 17 | 89.3 | 96.5–96.5 |

| Survey | 25 | 89.6 | 89.4–90.1 |

| Other | 2 | 72.8 | -- |

| Year of publication | |||

| 1995–2000 | 1 | 83.0 | -- |

| 2001–2005 | 6 | 73.0 | 72.8–72.8 |

| 2006–2010 | 7 | 93.1 | 88.7–96.5 |

| 2011–2015 | 19 | 77.5 | 60.3–85.0 |

| 2016–2020 | 47 | 54.3 | 40.3–61.0 |

| Study population type | |||

| Single hospital or healthcare system | 33 | 73.5 | 67.0–87.4 |

| Defined set of clinics | 5 | 82.0 | 73.0–87.0 |

| Single health plan | 16 | 54.2 | 40.3–60.3 |

| Population-based, single state | 5 | 91.1 | 90.0–92.9 |

| Population-based, multiple states | 7 | 89.8 | 89.4–90.1 |

| Nationally drawn | 5 | 73.1 | 72.8–72.8 |

| Other | 9 | 53.7 | 39.6–88.9 |

| Study population | |||

| Medicaid-insured | 15 | 62.8 | 49.4–85.0 |

| Commercially insured | 4 | 43.5 | 40.3–40.3 |

| Healthy Start | 2 | 88.3 | -- |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 3 | 72.8 | -- |

| Adolescent | 4 | 72.2 | -- |

| Predominantly but not specifically limited to low-income, uninsured, Medicaid or other underserved sociodemographic group | 14 | 75.7 | 61.5–87.0 |

| Diabetes | 12 | 66.9 | 40.0–96.5 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 2 | 40.3 | -- |

| Medically high risk but not single condition-specific | 3 | 82.7 | -- |

| Preterm birth or low birthweight | 2 | 77.3 | -- |

| Substance use disorder | 5 | 41.3 | 30.0–42.8 |

| People living with HIV/AIDS | 4 | 67.2 | -- |

| Specific contraceptive plan | 5 | 81.3 | 62.0–92.3 |

Abbreviations: postpartum visit, PPV; interquartile range, IQR; human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, AIDS

2 studies (Robbins et al., 2014 and D’Angelo et al., 2007) were excluded because they did not report the number of participants in the study population.

Text A.1: Search Strategy

Search terms: (postpartum OR postnatal) AND ((visit) OR (check*) OR (attendance) OR (utilization) OR (non-attendance)) AND ((United States) OR (USA) OR (US)) AND (healthcare OR health care)

Databases searched: PubMed, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science

Date range: Jan. 1, 1995 – Sept. 20, 2020

Date of search: October 5, 2020

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Attanasio L, Ranchoff B, & Geissler K (2021). Perceived discrimination during the childbirth hospitalization and postpartum visit attendance and content: Evidence from the Listening to Mothers in California survey. PLOS One. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0253055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant A, Blake-Lamb T, Hatoum I, & Kotelchuck M (2016). Women’s Use of Health Care in the First 2 Years Postpartum: Occurrence and Correlates. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20(Suppl 1), 81–91. 10.1007/s10995-016-2168-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilack V, Brousseau E, Paulo B, Matteson K, & Clark M (2019). Characteristics of women without a postpartum checkup among PRAMS participants, 2009–2011. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 23(7), 903–909. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw JR, Kozhimannil KB, & Admon LK (2019). High Rates of Perinatal Insurance Churn Persist After the ACA. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190913.387157/full/

- Daw JR, Winkelman TNA, Dalton VK, Kozhimannil KB, & Admon LK (2020). Medicaid expansion improved perinatal insurance continuity for low-income women. Health Affairs, 39(9), 1531–1539. 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSisto CL, Rohan A, Handler A, Awadalla SS, Johnson T, & Rankin K (2021). Comparing Postpartum Care Utilization from Medicaid Claims and the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System in Wisconsin, 2011–2015. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 25(3), 428–438. 10.1007/s10995-021-03118-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler K, Ranchoff B, Cooper M, & Attanasio L (2020). Association of insurance status with provision of recommended services during comprehensive postpartum visits. JAMA Network Open, 3(11), e(2025095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interrante JD, Admon LK, Stuebe AM, & Kozhimannil KB (2022). After Childbirth: Better Data Can Help Align Postpartum Needs with a New Standard of Care. Women’s Health Issues, 1–5. 10.1016/j.whi.2021.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. (n.d.). Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker. Retrieved July 1, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, & John PA (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions : explanation and elaboration. BMJ (Online), 339. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel JI (2018). Racial/Ethnic and Gender Disparities in Health Care Use and Access. Health Services Research, 53(3), 1407–1429. 10.1111/1475-6773.12705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masho SW, Cha S, Karjane N, McGee E, Charles R, Hines L, & Kornstein SG (2018). Correlates of Postpartum Visits Among Medicaid Recipients: An Analysis Using Claims Data from a Managed Care Organization. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 27(6), 836–843. 10.1089/jwh.2016.6137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow S, Kenney GM, & Goin D (2014). Determinants of receipt of recommended preventive services: implications for the affordable care act. American Journal of Public Health, 104(12), 2392–2399. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow S, Long SK, & Fogel A (2015). Primary care providers ordered fewer preventive services for women with medicaid than for women with private coverage. Health Affairs, 34(6), 1001–1009. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Mayes N, Johnston E, … Barfield W (2019). Pregnancy-related deaths in the United States and strategies for prevention. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(18), 423–429. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/pdfs/mm6818e1-H.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenatal and Postpartum Care (PPC). (n.d.). Retrieved June 1, 2021, from https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/prenatal-and-postpartum-care-ppc/

- Presidential Task Force of Redefining the Postpartum Visit, & Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2018). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 736: Optimizing Postpartum Care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131(5), e140–e150. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranji U, Gomez Y, & Salganicoff A (2021). Expanding Postpartum Medicaid Coverage. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/expanding-postpartum-medicaid-coverage/

- Sambamoorthi U, & McAlpine DD (2003). Racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and access disparities in the use of preventive services among women. Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 475–484. 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00172-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuebe AM, Kendig S, Oria RD, & Suplee PD (2021). Consensus Bundle on Postpartum Care Basics From Birth to the Comprehensive Postpartum Visit. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 137(1), 33–40. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor YJ, Liu T-L, & Howell EA (2020). Insurance Differences in Preventive Care Use and Adverse Birth Outcomes Among Pregnant Women in a Medicaid Nonexpansion State: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Women’s Health (2002), 29(1), 29–37. 10.1089/jwh.2019.7658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, & Schwarz EB (2017). Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California’s Medicaid program. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(1), 47.e1–47.e7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully KP, Stuebe AM, & Verbiest SB (2017). The fourth trimester: a critical transition period with unmet maternal health needs. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 217(1), 37–41. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Healthy People 2020. MICH-19. Increase the proportion of women giving birth who attend a postpartum care visit with a health care worker. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.healthypeople.gov/node/4855/data_details

- Wouk K, Morgan I, Johnson J, Tucker C, Carlson R, Berry DC, & Stuebe AM (2020). A Systematic Review of Patient-, Provider-, and Health System-Level Predictors of Postpartum Health Care Use by People of Color and Low-Income and/or Uninsured Populations in the United States. Journal of Women’s Health, 00(00). 10.1089/jwh.2020.8738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]