Abstract

Background:

Hospice care was initially designed for seriously ill individuals with cancer. Thus, the model and clinicians were geared towards caring for this population. Despite the proportion of persons living with dementia receiving hospice care substantially increasing over the past 10 years, and their longer lengths of stay, established hospice interventions for this population are scarce. No systematic review has previously evaluated those interventions that do exist. We synthesized hospice intervention studies for persons living with dementia, their families, and hospice professionals by describing the types of interventions, participants, outcomes, and results; assessing study quality; and identifying promising intervention strategies.

Methods:

A systematic review was conducted using a comprehensive search of five databases through March 2021 and follow-up hand searches. Included studies were peer-reviewed, available in English, and focused on hospice interventions for persons with dementia, and/or care partners, and clinicians. Using pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria, data was extracted guided by the Cochrane Checklist, and quality assessed using a 26-item Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Checklist.

Results:

The search identified 3,235 unique studies in total, of which ten studies met inclusion criteria. The search revealed three types of interventions: clinical education and training, usual care plus care add-on services, and “other” delivered to 707 participants (mostly clinicians). Five studies included underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. Outcomes measured knowledge and skills, psychosocial and health outcomes, feasibility, and acceptability, with significant improvements in six studies. Study quality was reflective of early-stage research with clinical education and training strategies showing deliberate progression towards real-world efficacy testing.

Implications:

Hospice interventions for persons living with dementia are sparse and in early-phase research. More research is needed with rigorous designs, diverse samples, and outcomes considering the concordance of care.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, end-of-life, quality of care, caregivers, hospice

Introduction

Currently, 55 million persons live with dementia worldwide; which is expected to increase to 78 million by 2030.1 As dementia progresses to its final stages, high quality, goal concordant, end-of-life care is important to persons living with dementia (PLWD), their family care partners, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and researchers.2,3 Hospice provides an interdisciplinary care model for dying persons and their families and is associated with better quality of life and death.4 Hospice care can occur in home, long-term care, inpatient hospital, and stand-alone hospice residence settings.5 In 2019, hospice served 1.61 million Medicare beneficiaries; 20.9% had a primary diagnosis of dementa.5 Patients with a primary or secondary dementia diagnosis represent a large (45%6) and growing proportion of hospice patients. In 2017, 55% of PLWD died in nursing homes and 21% at home.7 Although Medicare costs for PLWD in the last 5 years of life are high (mean: $86,430),8 hospice provides high-quality end-of-life care incurring relatively lower cost for families and the healthcare system.4,9 However, hospice professionals seldom receive dementia-specific training,10 and evidence-based best practices are lacking.3,11 Consequently, hospice professionals may be ill-equipped to meet the needs of this population, resulting in unwanted outcomes including live discharge, disrupted care,12 and burdensome transitions, creating financial strain13 and increasing stress and anxiety.14 Risk of these poor outcomes are especially high among Black and Latinx PLWD.15

Understanding available hospice interventions, participants served, outcomes measured, and results can help ensure effective steps are taken to promote high-quality end-of-life care for PLWD. Research involving PLWD and their family members often focuses on behavioral and psychosocial symptoms of dementia (BPSD) (e.g. agitation), PLWD symptoms (e.g. pain) at the end of life,16 and care partner burden, which are common in these populations.17,18 Additionally, measuring positive outcomes of PLWD and their care partners including quality of life, resilience, and resource utilization is important19 to capture the diversity of lived experiences and promote positive outcomes despite decline. Finally, attending to outcomes important to hospice agencies, regulators, and payors may promote care concordance among stakeholders and less disruptive care, better addressing the needs of PLWD and their families.

Recent reviews and summits evaluated numerous interventions targeting PLWD and their care partners.2,11,20,21 While these mention the importance of end-of-life outcomes, none focus on interventions in a hospice setting. One review of care interventions for PLWD at earlier stages of disease found emerging evidence for multicomponent interventions to improve care partner depression and that collaborative care models may support PLWD’s quality of life and health outcomes.11 Another systematic review focused on the quality of end-of-life care for PLWD in hospitals found palliative care interventions were inconsistently provided, but did not specifically examine interventions in hospice.21 To our knowledge, no systematic reviews examine hospice interventions for PLWD, their care partners, and hospice professionals. Examining the current state of hospice interventions, outcomes, and promising strategies can inform future research and intervention development and better equip hospice professionals to address the needs of PLWD.

This review synthesizes hospice intervention studies for PLWD and their care partners, including family members, and hospice professionals (licensed physicians, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, social workers, home health aides, and staff). Specifically, we sought to answer the following research questions (RQs): 1) Who are the target participants (e.g. PLWD, family care partners, clinicians, underrepresented racial and ethnic groups)? 2) What types of hospice interventions have been developed? 3) What are the outcomes measured and key results? 4) What is the quality of these studies? and 5) What intervention strategies have the most evidence?

Methods

This systematic review was conducted from March 26, 2021, to July 13, 2021. These dates reflect when the final search terms were run through the databases listed below (March 26–30) through completion of hand searching through citation lists (July 13). The protocol is registered with PROSPERO (Registration number: CRD42021246047).

Data Sources

A medical library information specialist (KP) performed a search through March 30, 2021, of the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Cochrane Library (Wiley), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), and APA PsycInfo (EBSCOhost). KP used controlled vocabulary and keywords to retrieve studies on hospice dementia care, limited to English language publications (additional details in supplement). Following the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) best practices for conducting systematic reviews, we searched dementia and hospice care along with synonyms (e.g. Alzheimer’s, terminal care) as key words.22 To maximize comprehensiveness, we intentionally used broad keywords in the initial search. At abstract review stage we erred on the side of inclusion, especially if a study mentioned the term palliative care, as it includes hospice in some cultures. We identified additional studies by examining retrospective and prospective references of the final studies included in the review. Search results were exported to Covidence, an online screening tool, and duplicate publications were removed.

Inclusion Criteria and Screening Process

We established inclusion criteria to guide the screening process for studies included in this review (see Table 1). Studies needed to describe or test an intervention, take place in a hospice care setting, (home, in-patient, hospice residence, long-term care etc.,) and target PLWD, their care partners (e.g. family members or caregivers), and/or hospice professionals. We included a range of study designs. To maximize comprehensiveness in identifying studies for possible inclusion, we flagged conference abstracts and protocol papers and searched for subsequently published follow-up studies. Using pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria, three authors performed title and abstract screening separately (ML, KB, EL). Next, three authors independently conducted full-text reviews (RL, LM, EL). At the title/abstract and full-text review stages, two team members agreed a study was appropriate for inclusion before the article moved to the next review stage. We achieved 98% initial overall agreement on title/abstract screening and 83% on full-text screening. Disagreements were discussed and resolved with all authors through consensus. For included studies, one author (KP) hand checked references and identified additional related studies, which underwent the title/abstract and full-text screening processes. All studies included after the full-text review underwent data extraction.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| 1. Pragmatic trials, RCTs, quasi-experimental design, pre/post-test design; pilot, feasibility, and acceptability studies; Conference abstracts (initial screening only) | 1. Case studies, surveys, secondary data analysis, electronic health record review, retrospective cohort studies; intervention protocol manuscripts; scoping, systematic, and meta-analysis reviews |

| 2. Intervention occurred in hospice (after a person was enrolled) and included hospice settings in community-based palliative care, hospitals, and nursing homes | 2. Intervention was not focused on hospice-enrolled persons, including interventions designed to refer people into hospice or change people’s attitudes or knowledge about hospice outside of a hospice setting |

| 3. Interventions for persons living with dementia (PLWD), their family/informal caregivers, and/or hospice clinicians involved in their care. | 3. Focus on diseases other than dementia or solely on formal/paid caregivers, such as home health aides; or caregiver or clinician outcomes for topics unrelated to dementia; clinicians other than hospice clinicians (e.g., getting physicians in hospitals or outpatient settings to make referrals to hospice) |

| 4. Policy, clinical practice, behavioral, psychosocial, educational, non-pharmacological and multi-component complementary interventions | 4. Medical interventions not performed in hospice; emphasis on clinical practice focused on running diagnostic tests, medical procedures, prescribing practices (other than deprescribing) |

| 5. Anticipatory grief or bereavement (i.g., dealing with grief before the person living with dementia dies) interventions | 5. Post death bereavement or grief interventions |

| 6. English language | 6. Full-text unavailable in English |

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Three authors conducted data extraction (RL, LM, EL). Two authors independently reviewed and completed the data extraction tool for each study meeting inclusion criteria. The data extraction tool, based on the Cochrane checklist,23 included study methods/design, participants, intervention (description, duration, frequency), outcomes, and results. Missing data were noted. Decisions, data extraction, and data management were tracked in Excel. In discussion with team members, and to facilitate presenting and interpreting results, studies were grouped into three intervention types: clinical education and training, usual care plus an add-on service, and other (Tables 2–3). Three authors (RL, LM, EL) assessed study quality, strengths, and weaknesses using a 26-item Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Checklist extension for randomized pilot and feasibility trials.24 Two authors independently completed the CONSORT checklist for each included study and discussed findings, reaching consensus to resolve conflicts.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participants, Included Hospice Studies, and Interventions by Categories

| Authors, year, country | N, participants served, sex, race and ethnicity, age | Design, intervention type, comparison | Duration, frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL EDUCATION AND TRANING INTERVENTIONS | |||

|

Jansen et al. (2018)

Ireland |

98: nurses, physicians, health care assistants, occupational therapists, pharmacists | Single-group pre/post with a mixed methods evaluation. (TEAM Pain AD teleECHO) | 1–5, 75-minute sessions, over 2-months |

|

Jones et al. (2021)

United States (CA, CT, NY, MN, MO, PA, TX) |

26 hospice social workers. Participants were primarily female, Caucasian, mean age=46. | Prospective pilot pre/post, single group design. Training modules for social workers. (Aliviado Hospice Edition) | 5-hour training modules over 3 months |

|

Lin et al. (2021)

United States (NY, CA) |

72 hospice interdisciplinary team members. Participants were primarily female, Black, with a mix of white, Asian/Pacific Islander, mean age=51. | Two sequential quasi-experimental pilot trial, pre/post, single group design. (Aliviado Hospice Edition) | 2-day champion training; online, self-paced training over 3 months for others |

|

Schneider et al. (2020)

United States (NY, CA) |

53 hospice nurses and social worker. Participants were female, primarily Black (remainder white), mean age=49. |

Sequential pre/post design. (Aliviado Hospice Edition). | 2 day in-person champion training; 5, 1-hour online training for others. |

| USUAL CARE PLUS SERVICE ADD-ON INTERVENTIONS | |||

|

Harrison et al. (2020)

United Kingdom (England) |

50: 39 PLWD, 11 family care partners. PLWD were 24 females, 12 males, 80–89 years old; care partners: 8 female, 3 male, 50–59 years old. | Service evaluation. (Admiral Nurse program) | Frequency unclear, over 1 year |

|

Harrop et al. (2018)

United Kingdom (Wales) |

35 current and bereaved family members of PLWD; nursing and care home staff, community hospice clinicians. | Mixed methods evaluation of community palliative care nurse specialists.. | Frequency unclear, over 16-months |

|

Hum et al. (2020)

Singapore |

254 PLWD in a home care setting. PLWD were primarily female, Chinese, mean age=87. 223 children of PLWD, mean age=58. | Prospective cohort pre/post. All-hours service. |

Frequency unclear, over 4 years |

| OTHER INTERVENTIONS | |||

|

Krauss et al. (2020)

United States (AZ) |

29 PLWD with agitation in home and inpatient hospice. PLWD were 12 males, 17 females with a mean age of 84. | Baseline, pre/post design. 12 nonpharmacological interventions targeting agitation and medication adjustments per standards of care. | Average of 3 visits over 17-months. |

|

Ferguson et al. (2020)

United States (Midwest) |

25 PLWD in a community hospice. Participants were mostly female and Caucasian, mean age=85. | Mixed methods, descriptive, feasibility study. Virtual reality intervention. | 3.5-minute video looped up to 30 minutes during 1 session. |

|

Volicer et al. (1986)

United States (MA) |

65:40 PLWD, 25 Veteran’s Affairs hospital interdisciplinary team members. PLWD were men, mean age=67. | Pre/post design. A hospice approach to guide decision making using 5 levels of care. | 1 team meeting, monthly family conferences, over 6 months. |

Note. Participant race and ethnicity and the magnitude of difference for results are listed in the table when reported in the included studies. PLWD=persons living with dementia. AZ=Arizona, CA=California, CT=Connecticut, NY=New York, MA= Massachusetts, MN=Minnesota, MO=Missouri, PA=Pennsylvania, and TX=Texas.

Table 3.

Outcomes Measured and Results by Intervention Categories

| Authors, year | Outcomes Measured | Results |

|---|---|---|

| CLINICAL EDUCATION AND TRANING INTERVENTIONS | ||

| Jansen et al. (2018) | Experiences and perceptions, knowledge and self-efficacy using pre/post survey and post focus group. | Sessions perceived to be useful for developing, applying, and teaching knowledge and skills for pain assessment and management in clinical practice. Improved knowledge and self-efficacy; 18/98 completed pre and 20/98 post survey, 10 nurses (p = 0.04), 10 physicians, (p = 0.02). |

| Jones et al. (2021) | Knowledge, confidence, and attitudes using Dementia Symptom Knowledge Assessment pre/post 1/post 2 (1 month). Practitioner satisfaction. | 26 completed Post 1assessment: significant improvements in confidence for implementing non-pharmacological interventions for BPSD (16.6%, p < .0001) and managing BPSD (16.9%, p = .01) and depression (25.2%, p < .0001). 23 completed Post 2 assessment: confidence and attitudes were maintained (F = 7.9, p < .001). Clinicians reported high satisfaction with the intervention: 64% “Very Satisfied,” 36% “Satisfied.” |

| Lin et al. (2021) | Feasibility using training completion, applicability using intention to change practice, fidelity using care plan/assessments administered. | 92% completed training; 82% submitted post-training survey; 89% and 96% intended to implement changes to clinical practice; 100% patients had care plan or assessment tool within 1 month of hospice enrollment |

| Schneider et al. (2020) | Attitudes, confidence, and knowledge using the Dementia Symptom Knowledge Assessment pre/post. | 39/53 completed post-survey with significant improvements in depression knowledge (4.7%, p = 0.008) and confidence (18.1%, p = 0.001), BPSD knowledge (5.5%, p = 0.01) and confidence (15.1%, p = 0.004), and nonpharmacologic intervention implementation (15.2%, p = 0.00030). Trainees reported ability to effectively assess for dementia symptoms. |

| USUAL CARE PLUS SERVICE ADD-ON INTERVENTIONS | ||

| Harrison et al. (2020) | Referral rate, caseload activity, family member survey, Satisfaction with Care at End-of-Life in Dementia, death in preferred place. | Increased referral rate and caseload activity, 5/5 care partners indicated high satisfaction with EOL care. 10/12 PLWD died in usual place of residence and preferred place of death. |

| Harrop et al. (2018) | Audit data using referral rates, participant perceptions using semi-structured interviews and surveys. | 75% more referrals for PLWD, increased demand for palliative (compared to EOL) support. Majority of family care partners reported project improved knowledge, confidence and skills; clinicians found project helpful. |

| Hum et al. (2020) | Pre/Post Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia, Mini Nutritional Assessment, Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia. | 53/254 PLWD completed pre/post. Improvements in quality of life (p = 0.001), pain (p = < 0.05), malnourishment (p = 0.001), and neuropsychiatric symptom severity (p = < 0.05). |

| OTHER INTERVENTIONS | ||

| Krauss et al. (2020) | Number of visits and intervention sessions; medication adjustments; Pittsburgh Agitation Scale. | Average of 3 visits and intervention sessions, 1 PLWD received medication adjustment only; most PLWD received >1 nonpharmacological intervention. 55% had medications adjusted. Decrease in total agitation from baseline and pre-test to post-test (F = 16, p < 0.001). |

| Ferguson et al. (2020) | Acceptability and tolerance using average wear time of the VR headset and Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia; BPSD using primary caregiver report. | Average wear time: 12 minutes. VR stopped early for 2 participants due to increase in pain; 56% reported enjoying VR, 48% would do it again. Primary caregivers reported no adverse events in 23 participants; BPSD worsened in 2 PLWD at follow-up. |

| Volicer et al. (1986) | Appropriateness using a questionnaire; comparison of care levels assigned by care team and family members; number of deaths; percentage of limited care. | 23/25 clinicians reported program was appropriate, 19 willing to recommend optimal care to families. No correlation in assigned level of care between interdisciplinary team members and families at baseline. Strong correlation at 6 months post (r = .79, p < .001). No increase in mortality despite 100% PLWD with limited care. |

Note. BPSD=behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. EOL=end-of-life. PLWD=persons living with dementia. VR=virtual reality.

Results

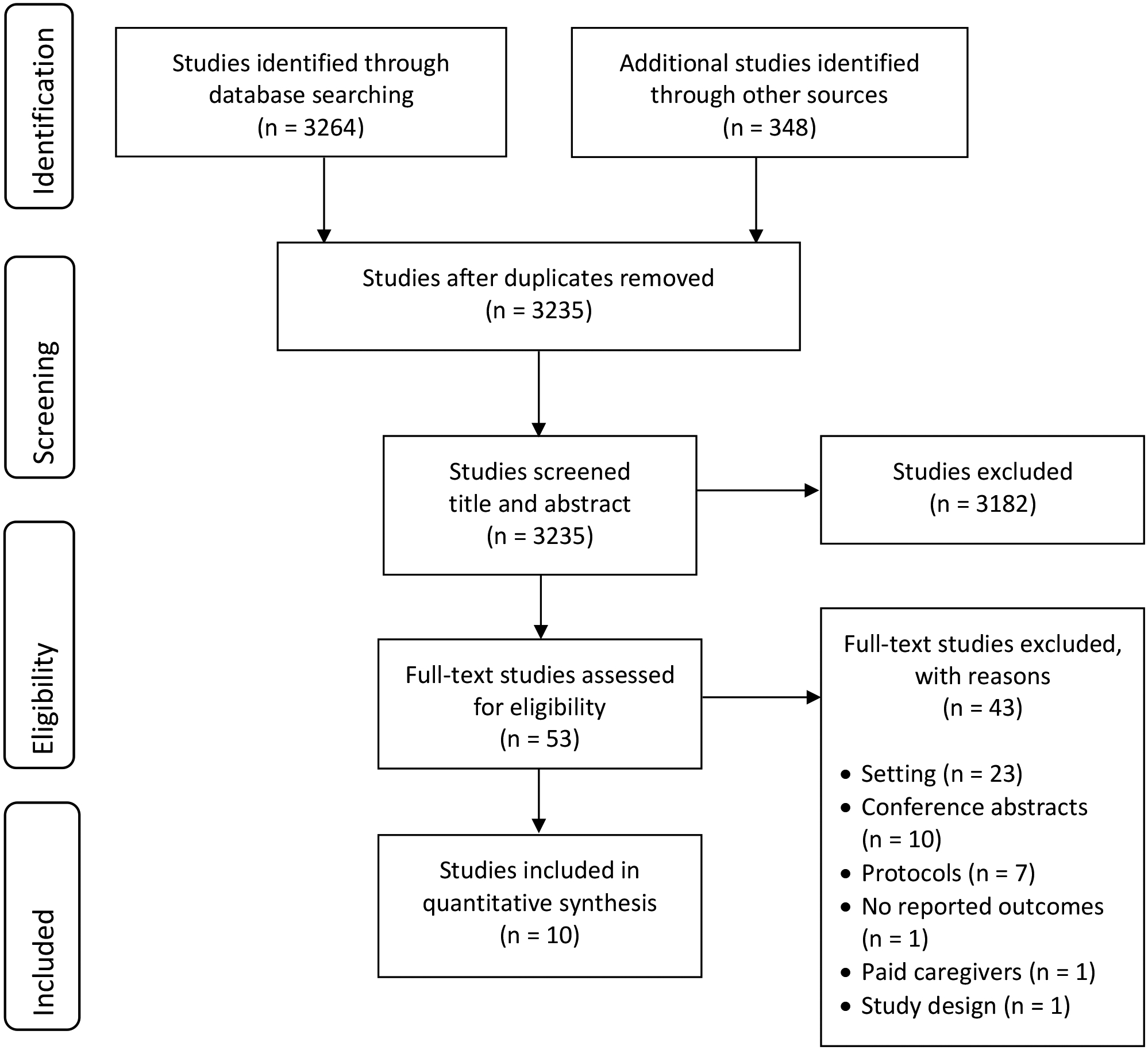

We identified 3,264 studies through electronic searches with an additional 348 found during hand searches of reference lists (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, 3,235 studies underwent title and abstract screening. Fifty-three studies met inclusion criteria for full-text screening. After the full-text screening, 10 studies were included in this systematic review.

Figure 1:

Flow diagram documenting the study selection process.

Study Characteristics and Design

The 10 studies included in the review are summarized in Table 2. They were conducted in the United States (US), United Kingdom, Ireland, and Singapore from 1986–2021. One study was published in 198625 the remainder between 2018–2021.

Study design varied and included quasi-experimental pre/post designs,25,26 prospective single-group pre/post design,27 prospective cohort,28 descriptive mixed-methods feasibility study,29 program evaluations,30–32 and sequential pilot trials.33,34 The level of intervention development and testing ranged from piloting25,26,28–32 to advancing a single intervention (Aliviado Hospice Edition) from a single group, prospective design,27 to a sequential quasi-experimental pilot trial in preparation for a full-scale embedded pragmatic clinical trial.33,34

RQ 1: Participants Served

Sample sizes ranged from 2529 to 254,28 and were largely recruited from community-based/home hospice settings.25,27,29–31,33,34 Other hospice settings included: inpatient,26 virtual delivery via zoom,32 and an intermediate medical ward.25 Participants included hospice clinicians25,27,32–34 (usually nurses25,32–34 and social workers25,27,33,34) and staff (health care assistants, aides, spiritual care, etc.),30 PLWD,26,28–31 and family care partners.28,30,31 Hospice clinicians’ mean ages ranged from 4627 to 5133 years old; care partners’ ages ranged between 50–59.31 PLWD were primarily 80–89 years old and in late-stage dementia.26,28,29,31 Half of the included studies reported race and ethnicity in their samples.27–29,33,34 Samples ranged from a majority of Black,33,34 white,29 and Chinese28 racial and ethnic groups (the latter occurring in Singapore). Four of the six U.S. studies included at least one underrepresented ethnic or racial group: Black,27,29,33,34 and Asian/Pacific Islanders and Latinx.27,33 No studies compared results based on underrepresented racial and ethnic groups.

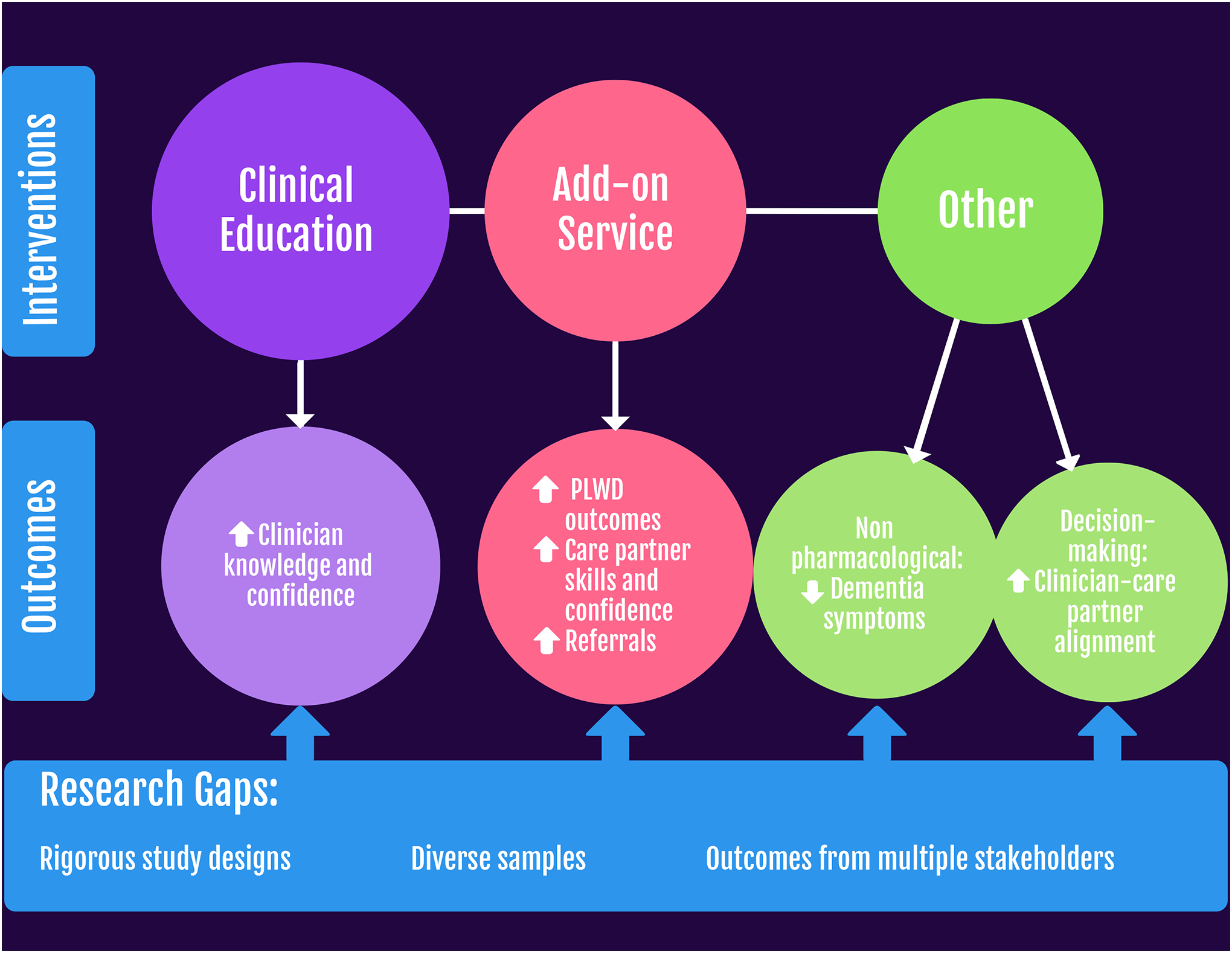

RQ 2: Types of Interventions

We grouped interventions into three categories: clinical education and training, usual care plus an add-on service, and other (see Figure 2). Most interventions sought to improve the quality of care for PLWD and their family care partners through multi-component interventions targeting multiple needs (e.g. knowledge, training, BPSD),25,27,28,30,31,33,34 while others sought to address a single need such as pain, agitation, and relaxing experiences for PLWD.26,29,32

Figure 2:

Hospice intervention types, key outcomes, and gaps identified for future research to address needs for persons living with dementia (PLWD).

Clinical education and training.

Four studies implemented education and training interventions aimed at increasing healthcare clinicians’ knowledge and care quality for PLWD.27,32–34 Three studies reported on outcomes of different iterations of the same intervention (Aliviado);27,33,34 one reported on the Enhance Assessment and Management of Pain in Advanced Dementia (TEAM Pain AD teleEcho) intervention.32 Interventions ranged in duration and frequency from attending one to five 75-minute sessions over two months32 to two-day trainings and five hours of self-paced modules over three months.33,34 Interventions were delivered via Zoom,32 online modules,27 or a hybrid of in-person training and online modules.33,34

Usual care plus an add-on service.

Three studies involved usual care plus an add-on service including a management nurse30,31 or all-hours service intervention28 to improve care quality for PLWD and care partners. The management nurse provided training and education to hospice professionals, coordinated care, and supported advanced care planning and emotional well-being.30,31 Hum et al.28 provided an all-hours on-call doctor and caregiver education on nonpharmacological intervention techniques including safe feeding and psychosocial support. Intervention frequencies were not reported. Interventions were delivered over 12–16 months, either in-person or via telephone.

Other interventions.

The three remaining studies involved two nonpharmacological interventions26,29 and one decision-making process to assign PLWD to different levels of care.25 Nonpharmacological interventions included delivering up to 12 nonpharmacological interventions over 17 weeks26 to address agitation and a single virtual reality session29 to provide relaxing experiences for PLWD. In one study, families received monthly conferences over six months to improve care.25 All of these interventions were delivered in person.

RQ 3: Focus of Outcomes and Key Results

Outcomes and results are reported in Table 3. Outcomes measured included surveys,30,32 interviews,30 and validated assessment tools.26,27,34 Clinical education and training interventions focused on clinician outcomes, although one documented pain for PLWD.32 Usual care plus add-on services and “other” interventions measured healthcare provider, PLWD, and family care partner outcomes. Outcome measures for hospice clinicians focused on skill-building,27,32,34 and positive psychosocial outcomes.27,32,34 Outcomes for PLWD included psychosocial outcomes of BPSD,26,30 quality of life,30 preferred place of death,31 and PLWD satisfaction.29 Health outcomes for PLWD included nutrition,30 and pain.26,29,30 Family care partner outcomes assessed caregiver burden28 and satisfaction with end-of-life care.31 Additional care partner outcomes included assigning a desired level of care to the PLWD25 and sharing experiences.31

Significantly improved outcomes included improved clinician knowledge, attitudes, confidence, and self-efficacy, and PLWD agitation and pain, quality of life and nutrition; and alignment of care goals between families and clinicians with positive trends in studies utilizing descriptive statistics.29–31,33 All studies had small samples, limiting the generalizability of their results.

RQ 4: Study Quality

We evaluated the quality of the 10 studies using the CONSORT checklist for randomized pilot and feasibility studies. Although the CONSORT checklist was designed for pilot and feasibility studies, we found that many of the interventions in our review were too early in their development for all 26 criteria to be applicable. Therefore, instead of reporting an assessment of quality on each study, we provide a general summary of strengths and weaknesses revealed by the checklist. Weaknesses were a lack of randomization across studies, omission of a rationale for sample sizes in all but one study,29 and failure reporting criteria for preceding to a future definitive trial (except Lin et al.33). Moreover, one third of studies provided ambiguous objectives and outcomes.25,30,31 In addition, most outcomes reported descriptive statistics; only one study reported confidence intervals.28 Strengths across these studies were reporting key elements of the introduction (scientific rational and objectives), methods (outcomes, number of participants included in the analysis), results (demographics and baseline data), and discussion (interpretation of findings, limitations, and future research).

RQ 5: Intervention Strategies and Evidence

Interventions strategies with the most rigorous study designs were education and training interventions delivered to hospice professionals, followed by clinical add-on services, with emerging evidence for nonpharmacological approaches, and family decision-making processes. However, all studies included were at early stages in intervention development and pilot testing and should be evaluated again as they progress through more advanced stages of intervention testing and implementation.

Discussion

This systematic review found a small number (10) of intervention studies targeting hospice dementia care, including clinical education and training, usual care plus care add-on service, and others. The quality of these studies varied, reflecting the early-stage research they presented. Clinical education interventions showed the most promise. While hospice interventions for this population are emerging, they require continued development. Next, we discuss our findings and highlight needs to guide future research, while considering hospice agencies and payors priorities, such as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), to support care for PLWD and their families that is concordant among all stakeholders while reducing disruptive transitions.

Our systematic review highlights a need for more rigorous study designs as all 10 studies were in the early phases of research and thus their effectiveness could not be evaluated. Notably, a gap occurred in published hospice intervention development for PLWD from 1986 to 2018. Volicer et al.’s25 1986 study was innovative, as hospice primarily served cancer patients at that time. Perhaps the two-decade gap in hospice interventions for PLWD reflects the natural progression of the disease prevalence, trajectories, and accompanying funding priorities. As the number of PLWD has steadily increased, interventions and funding have focused on PLWD in the early-to-moderate stages of disease.35–37 As the population of PLWD continues to age and die, end-of-life research has more recently garnered attention.38,39 While hospice interventions for PLWD experienced rapid growth in the last few years, they mostly remain in early development. So far, pilot studies have understandably relied on small samples. As researchers continue to move interventions towards implementation stages, they may struggle to recruit larger samples. Hum et al.28 provides one example of how larger samples might be incorporated into intervention studies. This systematic review, however, underscores an urgent need to advance hospice interventions towards efficacy testing with more rigorous research designs to better equip hospice professionals to meet PLWD and their families’ needs.

This review also brings awareness to the disparities for PLWD and care partners in hospice care and the dire need to create interventions for underrepresented populations. Only five studies included participants from racial and ethnic groups that are minoritized in the US. No studies compared differences in outcomes by participant racial and ethnic group membership or were created and tailored to address their needs. Furthermore, there was no representation from American Indians in these samples. The inclusion of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in participant samples shows progress. However, much work remains to address the persistent inequities in access and outcomes in end-of-life care for groups typically excluded from research, such as American Indians.40 While recruiting diverse samples can be challenging, researchers should consider targeting geographical locations with higher populations of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups and collaborate with them to optimize recruitment. Collectively, our findings support the persistent need to provide more equitable end-of-life research for PLWD.

Our review highlights interventions across multiple hospice care settings. Most interventions aimed at improving the quality of care were delivered to clinicians, which is consistent with the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering and Medicine’s3 recommendation for interventions targeting healthcare professionals in order to shift some of the responsibility for improved care and outcomes away from PLWD and their families. Moreover, nonpharmacological approaches are consistent with recommendations for nonpharmacological responses to BPSD and to decrease and avoid antipsychotic medications use in PLWD, particularly near the end of life.41,42 However, there is limited evidence for what treatments to use at the advanced stage of dementia or with terminal restlessness in PLWD, and none of these studies address these gaps.

Additionally, this review highlights a broad range of outcomes used in hospice intervention studies and a need to identify outcomes of interest among stakeholders. When selecting outcomes in future studies, researchers should carefully consider: 1) who defines and decides what outcomes are measured; 2) the alignment of these outcomes with organizational payor and policymaker priorities; 3) and the implications of what is being measured. Specifically, PLWD and their care partners should be involved in deciding what outcomes are measured and whether they are inclusive of the positive aspects of their dementia journey (e.g. resilience, resource utilization, well-being) to better reflect their diverse experiences. Focusing only on negative psychosocial outcomes prioritizes unwanted outcomes (e.g. BPSD, care partner burden), and may perpetuate negative attitudes of helplessness or despair in PLWD, their families, and clinicians.19 Researchers should also consider how outcome measures align with payor and policy makers’ priorities, such as care quality and continuity, as lasting organizational- and system-level changes will require the cooperation of these stakeholders. Only one study investigated satisfaction with end-of-life care and preferred place of death.31 No studies examined live discharges or transitions in care settings, which are problematic outcomes for PLWD,43,44 and of concern to hospice agencies and CMS.45 Considering how outcome measures may align with organizational payor and policymaker priorities can create an environment for fewer disruptions in care and may foster concordance among PLWD, family care partners, clinicians, hospice agencies, and CMS.

Implications and Future Research

This systematic review highlights the growing evidence of hospice interventions for PLWD, care partners, and clinicians and raises awareness of several gaps and challenges that must be addressed by future research. First, researchers should incorporate more rigorous research designs, such as sequential pilot trials and randomized pilot trials, to adequately prepare for full-scale efficacy testing, and incorporate creative strategies for recruitment, such as advanced informed consent for hospice patients to begin participation later during their hospice stay.46 Second, researchers must tailor interventions to address the needs of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, particularly indigenous groups like American Indians. Third, there is a need for interventions that target outcomes of mutual interest to PLWD, care partners, and hospice agencies and payors, including reducing live discharge and care setting transitions. Fourth, there is a need for intentional outcome development that includes PLWD and their family care partners in determining hospice intervention outcomes and utilizes strengths-based psychosocial outcomes that are inclusive of PLWD and their family care partners’ positive experiences. Fifth, researchers should consider opportunities for simple intervention trials (e.g. nudge trials) that can be easily integrated within the electronic healthcare record systems to improve the quality of care with a higher potential for sustainability than multi-component interventions, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

This review has limitations. Some studies may have been overlooked based on our inclusion criteria, which was limited to studies published in English. Also, we may have excluded hospice interventions in other countries that were not classified as “hospice” and may differ in delivery from traditional hospice care models in the US. To minimize this possibility, at the abstract and full-text screening stages, we were intentionally inclusive of studies conducted outside the US that might use a hospice care model but call it palliative care. Finally, we used the CONSORT checklist to evaluate study quality, which may provide a biased assessment of nonrandomized studies and interventions in earlier stages of development. For instance, Volicer et al.25 was published before the standards of the CONSORT checklist existed, which may have presented an unbalanced assessment of its quality as the standards for reporting studies have evolved since the 1980s.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review underscores that hospice interventions for PLWD, their family care partners, and clinicians are scarce and remain in the early phases of development. Clinical education and training strategies show the most promise and deliberate progression towards real-world efficacy testing. This review highlights a need for more rigorous research designs, diverse samples, and interventions targeting healthcare systems and clinicians. Additionally, outcomes measured should reflect the diverse experiences of PLWD and their family care partners with the incorporation of strengths-based psychosocial outcomes. Moreover, outcome measures should address the needs of PLWD and their care partners while aligning with hospice agencies and payors’ priorities to increase long-term sustainability of interventions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Text S1 Title: Search Terms and Databases

Key Points:

10 studies spanned three types of interventions: clinical education and training, add-on service, and ‘other.’

Hospice interventions for PLWD are in the early stages of development with clinical education and training interventions progressing towards real-world efficacy testing.

Why Does this Paper Matter?

Understanding the evidence can better equip hospice professionals to care for PLWD and their families; and guide the development of new interventions and outcomes to meet their needs, while considering hospice agencies and payors priorities to promote less disruptive transitions of care.

Acknowledgements

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor did not have a role in the design, methods, data acquisition, collection, and analysis; and the preparation of the paper.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers: AG065624 to E.A.L. and R33AG061904 to A.A.B. and R.K.F.L. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no known financial and personal conflicts of interest or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dementia. World Health Organization 2021 (online). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia. Accessed December 21, 2021.

- 2.Gitlin LN, Maslow K, Khillan R. National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers. Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Meeting the Challenge of Caring for Persons Living with Dementia and Their Care Partners and Caregivers: A Way Forward. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2021. doi: 10.17226/26026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Hospice Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America; 2021 Edition. Alexandria, VA: NHPCO; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, Lendon J. Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 3(38). 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross SH, Kaufman BG, Taylor DH, Kamal AH, Warraich HJ. Trends and Factors Associated with Place of Death for Individuals with Dementia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):250–255. doi: 10.1111/JGS.16200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Ann Inter Med. 2015;163(10):729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldridge MD, Moreno J, McKendrick K, Li L, Brody A, May P. Association Between Hospice Enrollment and Total Health Care Costs for Insurers and Families, 2002–2018. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(2):e215104. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.5104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unroe K, Meier D. Quality of hospice care for individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc.. 2013;61(7):1212–1214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler M, Gaugler JE, Talley KMC, Abdi HI, Desai PJ, Duval S, Fort ML, Nelson VA, NG W, Ouellette JM, Ratner E, Saha J, Shippee T, Wagner BL, Wilt TJ, Yeshi L. Care Interventions for people living with dementia and their caregivers. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 231. Rockville, MD: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell D, Diamond EL, Lauder B, et al. Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(8):1726–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wladkowski SP. Dementia caregivers and live discharge from hospice: What happens when hospice leaves? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2017;60(2):138–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson Campbell R Being discharged from hospice alive: The lived experience of patients and families. J of Palliat Med. 2015;18(6):495–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luth EA, Russell DJ, Brody AA et al. Race, ethnicity, and other risks for live discharge among hospice patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020. 68(3):551–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gijsberts MJHE, Achterberg W. End-of-Life Care in Patients with Advanced Dementia. In: Frederiksen KS, Waldemar G (eds) Management of Patients with Dementia. Cham. Springer, 2021, pp. 405–416. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P et al. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: The Cache county study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaugler JE, Bain LJ, Mitchell L et al. Reconsidering frameworks of Alzheimer’s dementia when assessing psychosocial outcomes. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2019;5:388–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon F, McDermott F, Kissane D. Systematic review for the quality of end-of-life care for patients with dementia in the hospital setting. J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018;35(12):1572–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J ADG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2 (updated February 2021). Cochrane, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.CONSORT Transparent Reporting of Trials. Pilot and Feasibility Trials 2010 (online). Available at: http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions/overview/pilotandfeasibility. Accessed December 21, 2021.

- 25.Volicer L, Brown J, Brady R. Hospice Approach to the Treatment of Patients with Advanced Dementia of the Alzheimer Type. JAMA. 1986;256(16):2210–2213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krauss BJ, Schlievert MA, Wagner BK, Deutsch DD, Powell RJ. A Pilot Study of Nonpharmacological Interventions for Hospice Patients With Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms in Dementia. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(6):489–494. doi: 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones TM, Brody AA. Adaptation and Piloting for Hospice Social Workers of Aliviado Dementia Care, a Dementia Symptom Management Program. Am J Palliat Med. 2021;38(5):452–458. doi: 10.1177/1049909120962459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hum A, Tay RY, Kin Y et al. Advanced dementia: an integrated homecare programme. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10(e40):1–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferguson C, Shade MY, Boron JB, Lyden E, Manley NA. Virtual Reality for Therapeutic Recreation in Dementia Hospice Care: A Feasibility Study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37(10):809–815. doi: 10.1177/1049909120901525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrop E, Nelson A, Rees H, Harris D, Noble S. The challenge pathway : A mixed methods evaluation of an innovative care model for the palliative and end-of-life care of people with dementia (Innovative practice). Dement. 2018;17(2):252–257. doi: 10.1177/1471301217729532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison Dening K, Crowther J, Adnan S. An Admiral Nursing and hospice partnership in end-of-life care : Innovative practice. Dement. 2020;19(7):2484–2493. doi: 10.1177/1471301218806427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen BDW, Brazil K, Passmore P et al. Evaluation of the impact of telementoring using ECHO © technology on healthcare professionals’ knowledge and self-efficacy in assessing and managing pain for people with advanced dementia nearing the end of life. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(228):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3032-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin S yin, Schneider CE, Bristol AA et al. Findings of Sequential Pilot Trials of Aliviado Dementia Care to Inform an Embedded Pragmatic Clinical Trial. Gerontologist. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider CE, Bristol A, Ford A et al. The impact of Aliviado Dementia Care Hospice Edition training program on hospice staff’s dementia symptom knowledge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e7–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Levin B. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276(21):1725–1731. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.21.1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R et al. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH): Overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directions. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):514–520. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gitlin LN, Marx K, Stanley IH, Hodgson N. Translating evidence-based dementia caregiving interventions into practice: State-of-the-science and next steps. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):210–226. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnu123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease 2020 Update. 2020:1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Filling the Gaps in Dementia-Capable Home and Community-Based Services: Report on Completed Administration for Community Living ADI-SSS Grants to Communities and States. 2021:.

- 40.Jones T, Luth EA, Lin SY, Brody AA. Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and End-of-life Care Interventions for Racial and Ethnic Underrepresented Groups: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(3):e248–e259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fazio S, Pace D, Maslow K, Zimmerman S, Kallmyer B. Alzheimer’s Association dementia care practice recommendations. Gerontologist. 2018;18;58(suppl_1):S1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salzman C, Jeste D v., Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: Consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008; 69:889–898. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v69n0602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luth EA, Russell DJ, Xu JC, et al. Survival in hospice patients with dementia: the effect of home hospice and nurse visits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(6):1529–1538. doi: 10.1111/jgs.1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russell D, Diamond EL, Lauder B, Dignam RR, Dowding DW, Peng TR, Prigerson HG, Bowles KH. Frequency and risk factors for live discharge from hospice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017. 65(8):1726–32. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Program for Evaluating Payment Patterns Electronic Report. Hospice PEPPER User’s Guide, 10th Edition. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Esch HJ, van Zuylen L, Geijteman ECT, et al. Effect of Prophylactic Subcutaneous Scopolamine Butylbromide on Death Rattle in Patients at the End of Life: The SILENCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1268–1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.14785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text S1 Title: Search Terms and Databases