Abstract

Background:

Although HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage in sub-Saharan Africa, reasons for diagnostic delays have not been well described.

Methods:

We enrolled patients >18 years with newly diagnosed KS between 2016–2019 into the parent study, based in Western Kenya. We then purposively selected 30 participants with diversity of disease severity and geographic locations to participate in semi-structured interviews. We employed two behavioral models in developing the codebook for this analysis: situated Information, Motivation and Behavior (sIMB) framework and Andersen model of total patient delay. We then analyzed the interviews using framework analysis.

Results:

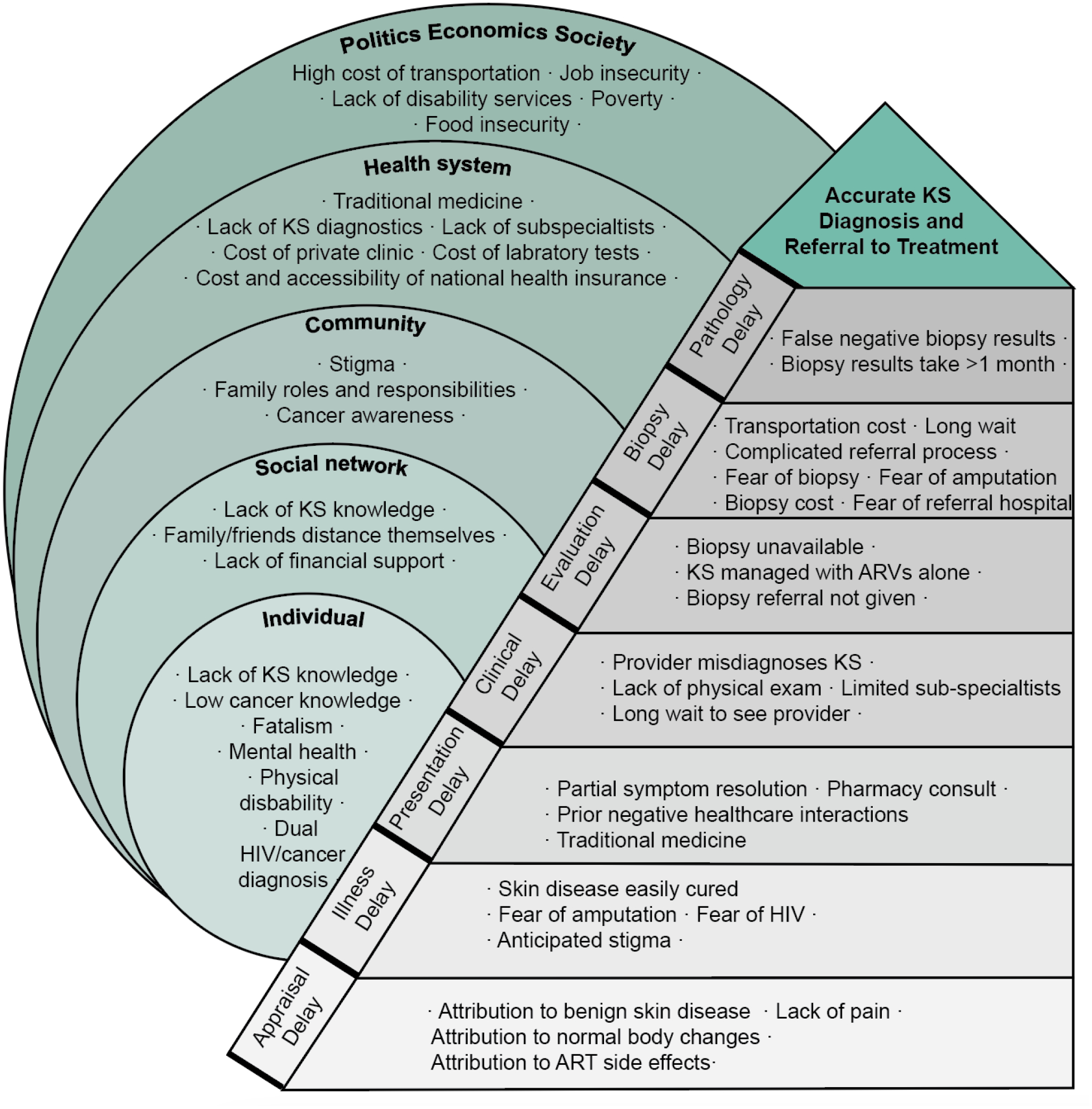

The most common patient factors that delayed diagnosis were lack of KS awareness, seeking traditional treatments, lack of personal efficacy, lack of social support, and fear of cancer, skin biopsy, amputation, and HIV diagnosis. Health system factors that delayed diagnosis included prior negative healthcare interactions, incorrect diagnoses, lack of physical exam, delayed referral, and lack of tissue biopsy availability. Financial constraints were prominent barriers for patients to access and receive care. Facilitators for diagnosis included being part of an HIV care network, living near health facilities, trust in the healthcare system, desire to treat painful or disfiguring lesions, and social support.

Conclusion:

Lack of KS awareness among patients and providers, stigma surrounding diagnoses, and health system referral delays were barriers in reaching KS diagnosis. Improved public health campaigns, increased availability of biopsy and pathology facilities, and health provider training about KS are needed to improve early diagnosis of KS.

Keywords: Kaposi Sarcoma, HIV/AIDS, Diagnosis, Africa South of the Sahara, Kenya, Qualitative

Introduction

Malignancies in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are overwhelmingly diagnosed at an advanced stage of disease.1–3 Access to chemotherapy and radiation is poor, thus earlier diagnosis of cancer is essential for improving overall survival.3–5 For HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS) earlier diagnosis is particularly critical, as ACTG T0 stage disease often requires treatment with antiretroviral therapy (ART) alone, while advanced T1 disease requires additional treatment with chemotherapy.6,7 Despite increasing access to ART, an estimated 69%–89% of KS patients in SSA are diagnosed with advanced KS, though population level data is lacking.6,8,9 This delay in diagnosis is a major public health problem, as KS continues to be one of most incident cancers in SSA.10

Prior studies have shown that for oncology diagnosis in SSA the two major diagnostic delays are the amount of time between a patient noticing symptoms and presenting to a healthcare provider11–13 and between a patient presenting to the provider and receiving a cancer diagnosis.14,15 However, few studies have analyzed diagnostic delays for KS specifically. One survey-based study from a Ugandan tertiary oncology facility showed that prior consultation with a traditional healer was a predictor of diagnostic delay for KS patients.16 Qualitative studies on cancer diagnostic delays in SSA have largely focused on breast and cervical cancer. In these studies, distance from the oncology facility, cost of diagnosis, use of traditional healers, limited cancer awareness, low provider knowledge, and fear of cancer have all been associated with a delay in cancer diagnosis.15,17–19 However, these factors have yet to be explored in HIV-associated KS, where patients suffer dual diagnoses of HIV and cancer combined with a visible skin disease.

To understand barriers and facilitators to KS diagnosis, we conducted semi-structured interviews with patients newly diagnosed with KS in a HIV primary care network in western Kenya. Through detailed exploration of individual paths to diagnosis, we were able to create a more complete picture of the diagnostic landscape for KS with the ultimate goal of highlighting potential areas for intervention.

Methods

Overall Design

The present study is part of a larger epidemiologic study of KS whereby all new cases of KS were enrolled using a rapid case ascertainment (RCA) methodology, which we have described in detail elsewhere.8 From this group of patients, we conducted a qualitative study from February 2019 to August 2019 at the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare (AMPATH), a network of HIV primary care clinics in western Kenya.

Study Population

AMPATH is a HIV primary care clinic network caring for over 160,000 people living with HIV at 60 different clinical sites. AMPATH is a consortium of North American universities and part of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA), which provided punch biopsies free of charge during the study period.8 Since 2008, physicians, clinical officers, and nurses from HIV and oncology departments have undergone punch biopsy training, allowing punch biopsies to be available at some of the satellite clinical sites.20,21 From our parent study, we purposively selected patients with newly diagnosed KS with a diversity of disease severity and geographic locations.

Data Collection

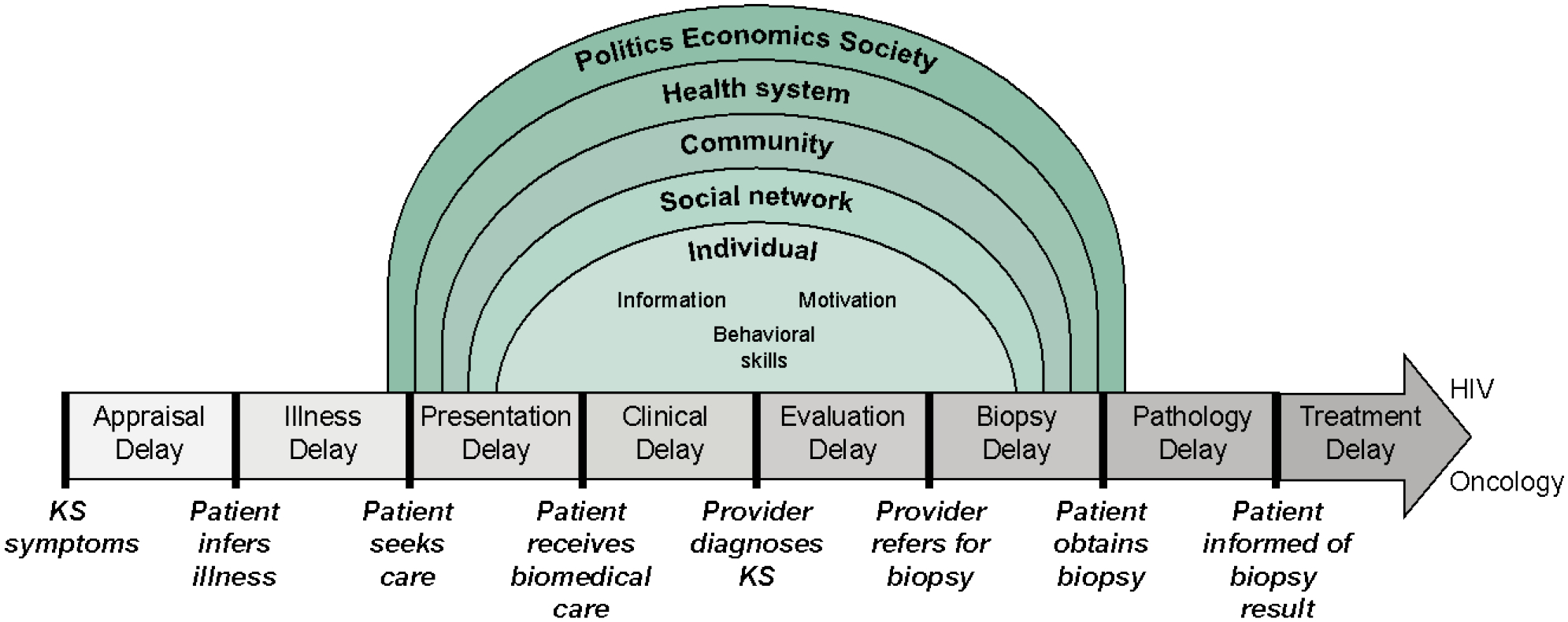

The interview guide was collectively developed by study authors using the modified Andersen model of total patient delay and socioecological models as conceptual frameworks (Figure 1). The modified Andersen model of total patient delay was proposed by Walter et. al. as a way to measure delays in cancer diagnosis in a high resource setting.22,23 We adapted this model to fit within the context of cancer delays in the Kenyan health system. Next, we situated these delays within the socioecological model, which includes individual, social network, community, health system, political, economic, and societal barriers and facilitators to diagnosis. For patient factors, we considered the Information, Motivation, and Behavioral Skill model as potential barriers and facilitators to individual decisions surrounding diagnosis (Figure 1).24

Figure 1:

Conceptual model for qualitative analysis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) diagnostic delay. Our model is based on the Modified Andersen Model of Total Patient Delay, which has then been situated within the socioecological model. The individual’s diagnosis seeking behavior has then been rooted within the information, motivation, and behavioral skills framework.

Study author LC (Female, Kenyan) conducted in-person, semi-structured interviews. Patients were compensated for their transportation to one of four health facilities, where all interviews took place. All participants provided written informed consent. During the interview, LC took detailed notes, and afterwards completed a post-interview feedback form which was discussed during a weekly call with authors DM and EF. All interviews were audio recorded and averaged one hour.

Data Analysis

The recorded interviews were transcribed in Swahili or English by trained Kenyan research assistants, and then translated into English when necessary. All Swahili and English transcripts were double checked by LC to ensure quality and integrity of data. Framework analysis was implemented using the modified Andersen model of total patient delay, which was situated within the socioecological model. An a priori coding framework was developed by the study authors to develop a deductive set of codes. Authors DM (Female, American) and MG (Female, South African) coded the first 25% of transcripts independently, using both inductive and deductive methods to verify and ensure reliability of the coding process. Coding structures were iteratively compared, and discrepancies were resolved by senior author EF (Female, American). Codes were compared until each theme achieved a Kappa score of greater than 0.6. Author DM then coded the remaining 22 transcripts using the master codebook. NVivo (Version 12) was used to facilitate analysis. In Microsoft Excel, codes were then grouped into themes with respective quotes and descriptions using both the a priori framework and inductive codes. Demographic and clinical data were analyzed using descriptive statistics with Stata (Version 16).

Results

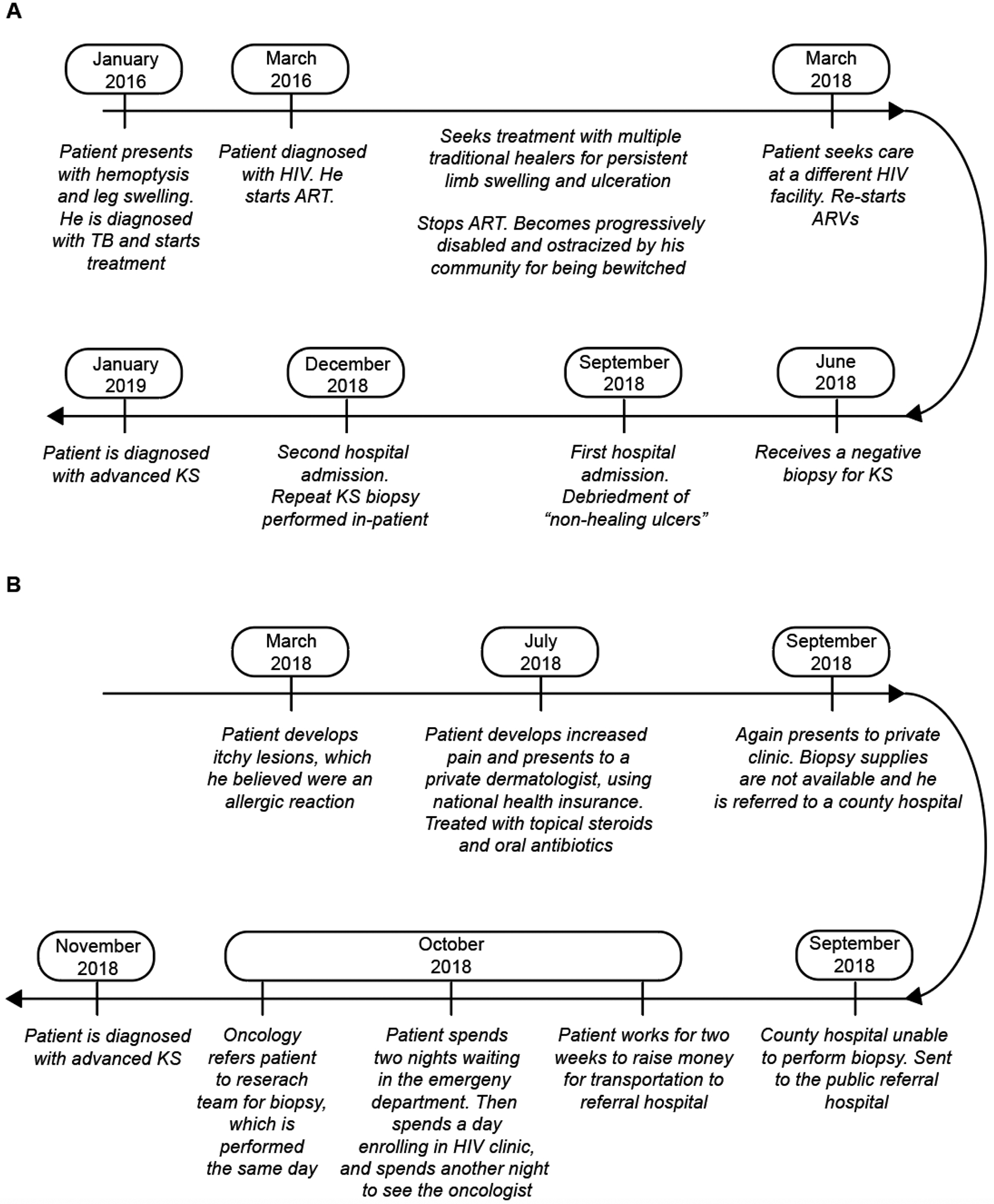

We conducted 30 semi-structured interviews with patients newly diagnosed with HIV-associated KS. Patients were majority male (83%), with a median age of 34 (IQR 30–40). Most patients were diagnosed with advanced stage (ACTG T1) KS (87%). Interviews took place at the academic center Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (17%) as well as at three HIV outreach clinics through AMPATH: Chulaimbo (63%), Busia (13%), and Kitale (6.7%). Two representative patient stories are demonstrated in Figure 2 and major themes are both described below as well as illustrated in Table 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2:

Two examples of the pathway to diagnosis for patients with KS

Table 2:

Quotes from patients demonstrating the barriers and facilitators to Kaposi sarcoma diagnosis

| Interview Themes | Quote |

|---|---|

| Barriers to Diagnosis | |

| Appraisal Delay | |

| KS attributed to benign dermatologic condition | “Okay according to how this problem started, it just started as a swelling. At first it started on the head, it was swollen here on the left so I thought that maybe I had been bitten by a mosquito. I sensed something of the sort but after a while it grew.” (#25, M, 29, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| KS attributed to ARV side effect | “Now this skin problem I have started when I began taking medication for HIV. It started with small lesions on the nose and on the head, but it worsens when I shave my head.” (#11, M, 50, Chulaimbo, early diagnosis) |

| KS attributed to normal body changes | “I just knew it was nature – it was a part of life – and it was going to resolve.” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Lack of pain from KS | “When the swelling started, I was not feeling any pain, but it grew to an extent that I started limping. Then I felt that it was getting serious.” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis) |

| Illness Delay | |

| Skin disease easily cured | “I thought it [skin disease] was one of those that would just go away after sometime, but it got worse instead (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Fear of amputation | “You know for cancer when they start amputating your leg it goes bit by bit until it reaches up here {points to hip}. If I were to be amputated who would take care of the family since it is only me they have?” (#20, M, 41, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| Fear of HIV | “I: Were you scared before you went to the hospital that this skin problem could be related to HIV? R: Yes, I was afraid. I: Did that keep you from going to hospital? R: Yes, it took some time.” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Anticipated stigma | “I started hiding myself because the swelling was huge, that it even scared some people. Some told me I had been bewitched” (#17, M, 32, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis). |

| Presentation Delay | |

| Traditional medicine | “They apply the herbal medicine and some to take orally and for bathing, but they didn’t work, days were moving and the rashes were worsening, you are spending a lot of money and the disease is not improving.” (#9, M, 46, Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Consulting with a pharmacist | For most illnesses I just go to the chemist…he gives me the medication and I go home…It is available. When I think of the queues at the hospital it is not encouraging” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis) |

| Prior negative health worker interactions | “I had been taking my baby to the clinic and there was a time when I was late…They quarreled with me. You know doctors are very harsh” (#16, F, 27, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Partial symptom resolution | “The dermatologist told me that if it is persistent, I should go for biopsy. He really recommended biopsy for me long time ago last year July, it is me who took it lightly because when the dermatologist gave me the drugs, the problem reduces, so I thought that the problem was solved, like the black patches went away, the itching reduced so I thought the problem was over.” (#30, M, 43, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| Clinical Diagnosis Delay | |

| Long wait to see provider | “Before I saw the doctor, I had to spend a night {at the Referral Hospital}…I slept on the bench with my wife.” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis) |

| Limited access to sub-specialists | “In this generation the doctors have hospitals around the town, so they don’t attend to patients in hospital, you may wait for a doctor for many days to attend to you” (#30, M, 43, MTRH, late diagnosis). |

| Provider misdiagnoses KS | “I told them I was seeing swelling and was very itchy day and night, so they told me that I should insert the legs in cold water” (#24, M, 39, MTRH, late diagnosis). |

| Provider does not perform physical exam | “I: The doctor at this dispensary, did he do a full body examination? R: They checked my blood pressure and tested for malaria alone” (#27, F, 31, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Evaluation Delay | |

| Biopsy referral not given | “They mentioned that it could be skin cancer … they said that they didn’t have that testing machine so maybe I should go to {Larger Referral Hospital}.” (#25, M, 29, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| Skin biopsy unavailable or not performed | “They just found HIV and TB because they were blood tests, but they did not know that a tissue sample had to be collected to diagnose skin cancer.” (#24, M, 39, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| KS managed with ARVs alone | “He [doctor] only asked me to take medicine [ARVs] and that the lesion would clear.” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Biopsy Delay | |

| Fear of referral hospital | “I was afraid that I would be admitted at the ward and stay at the hospital.” (#5, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Fear of cancer diagnosis | “I was worried because I did not know about this; I used to just hear about cancer. Cancer kills people, I did not know more” (#5, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis). |

| Fear of biopsy | “When I went back, they told me that they would have to do a biopsy but felt that I would over bleed if they did.” (#16, F, 27, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Fear of amputation | “It’s the one which was really worrying me, because some time back I heard that if you develop cancer even at your lower leg, the leg will be amputated and you will die eventually….but for the HIV condition, you can live for 40 years, now this Cancer was really worrying me….” (#17, M, 32, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Long wait for skin biopsy | “Someone told me to go to [Referral Hospital] so when I got there, they advised me to see the oncologists, who told me to undergo a biopsy. But doing a biopsy was a problem because they were dealing with biopsy cases on a Wednesday, and I was there on a Thursday. So, I waited until the next Wednesday, and they told me they do not have the biopsy needles, so the referred me to [Larger Referral Hospital]. But when I came to [Larger Referral Hospital] just seeing a doctor was a problem….I finally saw a doctor on the third day after spending three days waiting” (#30, M, 43, MTRH, late diagnosis). |

| Complicated referral process | “It was a challenge… you may think the hospital that you have gone to, like when I have come here, you have come to the hospital here, and a doctor will attend to you, yet he cannot attend to you but give you a referral letter. That will definitely bother you since you will wonder why he could not attend to you, but instead referred you elsewhere” (#8, M, 40, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Biopsy cost | “I was told about the biopsy and because I was fearing the cost…I tried to avoid it” (#30, M, 43, MTRH, late diagnosis). |

| Transportation cost | “I went to [health dispensary], and I was given a referral letter to come to [Referral Hospital], but I didn’t have any money to come, so I stayed like this for another month or two…” (#17, M, 32, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis). |

| Pathology Delay | |

| Biopsy results take >1 month | “They told us that they would call us after 2 months when the [biopsy] results will be out. (#5, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Biopsy results initially negative | “I came to hospital for biopsy in June. The results turned negative… I did not see any improvement; I went back and was tested and told, I am positive.” (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Socioecological Factors | |

| Limited KS and cancer knowledge | “Could you be knowing the cause of this skin cancer? I have never known the root cause of this disease.” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Fatalism | “When I just heard that I have cancer, I just started to cry, ‘my time is up here in this world I am about to die’ I just left the hospital and sat somewhere out there crying, that is even before I made any call. I just cried there ‘my life is over.’” (#19, F, 39, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Mental health | “I stayed in the house crying, saying ‘Why am I getting this condition, yet I have children who want to eat, is there anything that I did?’ I just kept asking myself ‘Should I commit suicide or what?’” (#15, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Physically debilitated by KS | “I was not able to get out of my bed, and the way my leg was discharging, within two minutes the bed would be wet, and I because could not get out of bed, so I urinated and defecated inside of the house, and ate while laying like this” (#9, M, 36, Busia, late diagnosis). |

| Coping with dual diagnosis of HIV and cancer | “I was frustrated; I had just had the first diagnosis [HIV], then this one [cancer]! (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Lack of social support | “Yes, you know there are these kind of people who do not want to help you, they tell you just stop bothering, you have been in and out of the hospital so many times with no help, you are just wasting fare, stay at home and wait upon God.” (#15, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Lack of disability services | “Whenever I called a motorcycle to pick me up from my home they avoided me, because they had to carry me from my bed and put me on the motorcycle” (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Transportation cost and time | “My only concern was money, just money. Money for fare, medication, I don’t have anything at the moment. (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Poverty | “The challenge was just money, this treatment has costed me a lot, I have sold everything… like I had chicken but sold all of them, my bicycle, I had sugarcane in the farm, I rented it out the first time for sixteen thousand, I then gave someone to harvest it up to four times… I spend all the money but did not get any results. (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Food insecurity | “This has affected my ability to work, I wasn’t working. On family, when it comes to food, you know when you don’t work the children will have no food.” (#25, M, 29, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| Job insecurity | “That time I suffered a little because I had no income that was coming in – you know if you had been working and you lose your job you will be stressed.” (#5, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Facilitators to Diagnosis | |

| Appraisal Delay | |

| Cancer public health campaigns | “I knew it was cancer when it started getting big… I had seen something similar in the pictures for cigarettes” (#16, F, 27, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Illness Delay | |

| Social network emotional support | “They encouraged me to go to the hospital so I can know my status, they kept encouraging me until I made up my mind to go.” (#8, M, 40, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Social network instrumental support | “How I got fare for transportation was through my boss, I told him I would like to go to the hospital and he sent me fare, one thousand {shillings}.” (#11, M, 50, Chulaimbo, early diagnosis) |

| Knowing a KS patient | “She [neighbor with KS] told me that it could be cancer and that I should go to the hospital…So she was just basically advising me to go to the hospital, because she was being treated there (#17, M, 32, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Social network recognizes KS lesion | “She just told me that there is a colleague of hers at her workplace who is suffering from the same condition, so she just told me ‘just go to a hospital and you will see change’ ” (#15, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Presentation Delay | |

| Needing to provide for family | “I am the breadwinner at home…I stayed at home without working and it really cost me. I felt that if continued that way it was my family that was suffering” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis). |

| Fear of cancer | “She came to me and told me that she knew of a relative who had this illness and that if I didn’t visit the hospital I would stink so bad nobody would want to come close to me and my leg would develop a huge wound and a time would come for it to get amputated. That made me decide to tell my husband and discuss about my visit to Chulaimbo” (#21, F, 26, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Skin changes painful/disabling | “Because of the swellings, they were getting worse, my eyes were puffy; I had ulcers on the body, black spots. I was unable to walk. I wanted to know what it was, what was causing it.” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Clinical Delay | |

| Being part of an HIV care network | “I was told that cancer is very expensive, and I was told to be prepared because it may get to a point that I may even have to sell a shamba [crop]…But when I came here [AMPATH], the first lady I got, explained to me about the expenses, because she told me if I am able to change most of my things [appointments to AMPATH] then I will be able to be catered for it till I get well. The only thing to hustle for is transport. So, when I did that I relaxed because I knew even if they were to ask for money it would not be a lot.” (#28, M, 42, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Trust in the health system | “I was not worried because I know that when a doctor does a test and gives a result and starts treatment, then I will get well.” (#11, M, 50, Chulaimbo, early diagnosis) |

| Provider diagnoses KS quickly | “I went to the doctor and he told me that this disease is KS, and the treatment for it can only be found at {Referral Hospital}. That is when I came here.” (#28, M, 42, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Evaluation Delay | |

| Diagnosis within tertiary care facility | “Now the name of the disease, when I went to the hospital, the doctors examined me, when they examined me, they told me this disease is called sa…sa….sarcoma, now that hospital I went to, where I was, before I was given a transfer to Chulaimbo. When I went to Chulaimbo, they did tests on me, they did a biopsy on the foot, now when they brought back the results told me that it was sarcoma, cancer of the leg.” (#8, M, 40, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Referral instructions provided | “I went to the dental [clinic] and I met a certain doctor and I showed him then showed them the referral letter. They said that was not the place and they called another doctor. The doctor called me to say that he had sent a lady to see me and that is when [research doctor] came.” (#16, F, 27, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Biopsy Delay | |

| Research study staff | “Once we got here, we met {the research staff} who took care of me, injected me then also took a biopsy, and told me he would be calling me immediately once results are out.” (#15, M, 34, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Pathology Delay | |

| Quick turn-around time for biopsy results | “The results took about a week…it was a short time, if you compare to other hospitals that can take even a month before you get the results.” (#9, M, 46, Busia, late diagnosis) |

| Socioecological Factors | |

| Self-efficacy | “I have gone through a lot of challenges, but I have kept up faith. I knew that one day I would succeed.” (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis) |

| System navigation skills | “I had decided that I would go, I must go, since this was not normal, I have never seen this, I had decided that against all odds, I would go to the hospital” (#3, M, 35, Kitale, late diagnosis) |

| Health literacy | “From Google I have seen several types of Kaposis…but the kind of Kaposis that I am suffering from most and most people from here are suffering from is the one which is related to HIV” (#23, M, 43, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Social support | “They would tell me to, when I had not known my status, they encouraged me to go to hospital so I can know my status, they encouraged me till I made up my mind to go.” (#8, M, 40, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

| Health insurance | “What made me hold onto this process is because I could afford it, I had health insurance cover and I also supplemented with my salary.” (#30, M, 43, MTRH, late diagnosis) |

| Transportation fare assistance | “The fare that I thought was a challenge…., the people at Chulaimbo has been giving me half of the fare, I only need to raise something small, I mean they have really held my hand….yeah, that is what has made happy” (#17, M, 32, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis) |

Figure 3:

Themes for diagnostic delays of Kaposi sarcoma, as experienced by people living with HIV recently diagnosed with KS in Western Kenya. For the analysis, qualitative themes are grouped according to the modified Andersen model of total patient delay, which are then situated within the socioecological model.

Appraisal Delay

The appraisal delay is the interval between noticing a symptom of KS, often a skin change, and inferring illness. A major barrier was the patient’s initial interpretation that their KS lesions were due to benign conditions or normal skin change. Patients commonly attributed KS lesions to insect bites, allergic reactions, aging, or side effects of ART. Patients often did not report pain with KS lesions, lessening their suspicion for illness. Additionally, most patients had never seen or learned about KS before, and thus had low suspicion for the disease. An important facilitator during this interval was if the patient had previously met someone with KS or saw public health campaigns related to cancer or KS, allowing them to recognize similar lesions on their body.

Illness Delay

The illness delay is the interval between the patient inferring illness and deciding to seek care. Many patients viewed skin disease as less emergent than other diseases, and felt that delays in seeking treatment would not have major consequences. For patients whose disease became more severe, they often avoided seeking care due to fear of stigma in the community from their illness. Patients additionally worried about invasive procedures that would have to be performed, including amputation, and fear of learning their HIV status at the clinic.

An important facilitator during this time period was having a member of the patient’s social network recognize the lesion as potentially dangerous while providing encouragement for them to visit a health center and/or providing transportation or financial support to seek treatment.

Presentation Delay

The presentation delay is the interval between the patient seeking care and receiving biomedical care by a trained healthcare provider. After inferring illness, patients usually first sought advice from within their social network, including family, friends, and community leaders. More than half of patients were advised by their social network to visit traditional healers, often alongside allopathic providers. The most common traditional reason given for the lesions of KS was that a person can be bewitched by another by placing dangerous herbs in the path commonly used by the targeted person, causing the leg to swell. Patients often spent substantial time and resources pursuing traditional remedies before receiving allopathic care. A few patients first sought care from local pharmacies. Some of these patients were given pain medications or topical steroids which masked the illness, delaying eventual diagnosis of KS.

Patients additionally delayed allopathic care due to negative prior healthcare interactions, including long lines and being reprimanded or treated harshly. Some patients were particularly worried about visiting the clinic after stopping or delaying ART, as many patients we interviewed were aware of their HIV status, but had stopped taking ART.

A prominent facilitator to patients seeking diagnosis was to provide for their family. Many of the participants interviewed had spouses and children who relied on them for food and school fees. The inability to provide for their families due to illness caused many patients to seek diagnosis and find treatment.

The fear of potential cancer also motivated some patients to seek care. As one patient reported, “When I saw my leg just starting to swell I was like ahh I will have that cancer wound, and it will not heal, and I will just die! And my children will remain by themselves? God help me!” (#19, F, 39, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis). Many patients did eventually seek allopathic care once their skin changes and edema became disabling, malodorous, or painful. Additionally, a few patients were motivated to present to a health facility by having health insurance and knowing that health costs would be covered.

Clinical Diagnosis Delay

The clinical diagnosis delay is the interval between patients seeking biomedical care and receiving a clinical diagnosis of KS. One barrier to diagnosis was experiencing long lines within hospitals. Although dermatologists and oncologists had private clinics with appointments available, it often took many days to see sub-specialized physician within the public hospital. As one patient stated, “I was told that the dermatologist is not availability daily…I was worried I would find a long queue with many patients” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis). Another patient emphasized the challenge of waiting in hospitals in an advanced state of health, reporting “there is a time I was brought here to queue for a long time, I really suffered, and I would get out of the wheelchair and lie on the floor” (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis).

Few patients reported being misdiagnosed with other conditions, such as skin infections, tuberculosis, malaria, or alcohol-related problems. One issue was some providers did not perform a full physical exam and missed visually diagnosing KS.

Delays in clinical diagnosis often prompted patients to return to or initiate contact with traditional healers, including spiritual healing through prayer and herbalists. As one patient recalled, “If at the hospital they tell you that they don’t know what the problem is, then what comes to your mind? I am bewitched” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis).

A facilitator for some patients in receiving a clinical diagnosis was already being part of an HIV care network, which allowed patients to more easily access and have preexisting trust in the healthcare system. A few patients reported being diagnosed with KS during their scheduled HIV clinic appointments, and other patients reported being diagnosed with KS quickly by the first healthcare provider they met.

Evaluation Delay

The evaluation delay is the period between a patient being clinically diagnosed with KS and being referred to a specialist for skin biopsy and further KS management. Some patients were told that biopsy services were not available at the health facility, but were not given instructions about where to travel for sub-specialty care. For example, some patient were told they would need further care at a referral hospital, but were not given referral paperwork or instructions on how to find skin biopsy services at the referral hospital. Additionally, a few patients were initially diagnosed with early-stage KS and given ART alone. Although this therapy may work for some patients, a few of the patients interviewed had disease progression despite taking ART.

Facilitators during this period included diagnosis of KS at the tertiary hospital or associated satellite clinic, which allowed for a more seamless referral for biopsy services.

Biopsy Delay

The biopsy delay is the period between a patient being referred for skin biopsy and actually receiving a biopsy. During the referral process, patients often struggled with the new diagnosis of cancer and feared having to go to a referral facility for a biopsy. Some patients associated having to go to a referral hospital with death and dying. As one patient said, “you know when you are diagnosed with cancer, they say it is a death sentence, and many other things” (#1, M, 34, Chulaimbo/Busia, late diagnosis).

Patients also worried about potential costs of diagnosing and then treating the cancer, making some wonder whether traveling to the referral facility was worth the cost: “I was told that [KS] is a skin cancer, and I asked myself is this like the cancer which I hear costs a lot of money?” (#31, M, 28, Busia, early diagnosis)

Patients additionally feared the biopsy process, believing that the biopsy may seed cancer to the body. Patients also feared having a biopsy would lead to amputation for cancer, with one patient reporting “You know for cancer when they start amputating your leg it goes bit by bit until it reaches up here [points to hip]. If I were to be amputated who would take care of the family since it is only me they have?” (#20, M, 41, MTRH, late diagnosis)

Some patients additionally feared the potential cost of biopsy, as well as other costs related to going to the tertiary hospital such as transportation and laboratory expenses. A large number of patients had to travel multiple hours and pay transportation fees to receive a biopsy. Transportation was especially difficult to obtain for patients who were unable to walk, as they had to call a private taxi or motorcycle to take them to the facility.

A major facilitator during this time period was the parent research study staff, who helped arrange biopsy appointments and transportation.

Pathology Delay

Lastly, a few patients experienced delay between having a biopsy and being told of a pathologic diagnosis of KS. For some patients the pathologic diagnosis took over one month, due to a limited number of pathologists working at the tertiary referral hospital and delays in contacting patients. Additionally, a small number of patients were initially told they had a negative biopsy for KS, leading to further delays in care. The main facilitator was a relatively fast turnaround time for the pathologic diagnosis of KS with good follow-up communication of biopsy results.

Socioecological Model

Individual level barriers included limited KS and cancer knowledge, stigma, physical disability, mental health disorders, and coping with a dual HIV and cancer diagnosis. Individual level facilitators included self-efficacy, system navigation skills, and health literacy. Within the patient’s social network and community, stigma was a major barrier while social support was a major facilitator.

There were many larger health system and economic factors that served as barriers and facilitators to diagnosis. The most common structural barrier in delaying diagnosis was poverty. Lack of finances to pay for transportation to and from various health facilities as the patient sought a diagnosis was the most common theme identified. One patient reports, “I used to go to school but then later I stopped so it was my husband to do everything, he was to ensure the kid is in school, he is to put food on the table, money for treatment all on him, so he really struggled, and at times the odd jobs he does are not available.” When asked if they were forced to sell something for money the patient responded, “ yes (affirmative) we sold a cow” (#19, F, 39, Chulaimbo, late diagnosis). A large number of patients lost their livelihoods due to KS, and had to further sell income generating possessions to pay for transportation and other healthcare expenditures.

Structural facilitators to diagnosis included pre-existing health insurance or assistance with enrolling into national health insurance, living near the health facility, and transportation reimbursement.

Discussion

In SSA, there is the need to better understand factors that contribute to diagnostic delay for HIV-associated malignancies.25,26 In our qualitative study, we found that patients faced many barriers to diagnosis with HIV-associated KS throughout the care cascade. Major themes included limited knowledge of KS for both patients and providers, stigma associated with KS, delayed clinical diagnosis, and referral delays leading to longer wait times for pathology results.

As the population of people living with HIV continues to age in SSA due to effective ART, the burden of both HIV-associated and general malignancies will continue to increase in this patient population. Most patients in this study had heard of cancer broadly but had limited knowledge about its diagnosis or treatment. In fact, most patients viewed cancer as a death sentence, lessening motivation to engage in care once diagnosed. Improved public health campaigns about cancer screening and diagnosis are needed to improve patient misconceptions.2,12,27 Additionally, healthcare providers taking care of patients with HIV require cancer specific training for common HIV-related cancers.

Seeking diagnostic care from a traditional healer was common in our patient population, which has previously been associated with diagnostic delays in KS.16 About half of interviewed patients saw a traditional healer and used herbal medicine during the course of their illness. At times, seeking help from a traditional healer may indicate health seeking behaviors more generally, which in a previous study was associated with faster time to treatment initiation.14 Regardless of whether traditional healers help or hinder patients’ time to cancer diagnosis, they remain an important part of Kenya’s plural health system and must be considered when designing cancer diagnostic interventions.

Additionally, in this study we found KS-related stigma was a major barrier for patients receiving a diagnosis. In contrast, prior studies from SSA found overall low levels of general cancer related stigma.2,27 This may be because KS is a highly visible cancer, and is frequently associated with a HIV positive status. Prospective evaluations of KS-related stigma are needed. Stigma from HIV-related cancers may be a barrier to diagnosis beyond SSA as well.28

After being clinically diagnosed with KS, a major barrier for patients was being referred to a specialty hospital for a skin biopsy, which is critical for the diagnosis of KS..29–31 The difficulties patients faced receiving a skin biopsy points to the need to decentralize specialty services such as skin biopsy availability to primary care facilities and health centers. Task-shifting to teach mid-level providers in punch biopsy techniques could potentially be used to decentralize punch biopsy to peripheral HIV and/or health centers.20 However, this is still the need to transport the skin biopsy specimen to a histopathology laboratory for pathologic diagnosis, which is a major delay for multiple types of cancer in SSA.32,33

For patients who knew their HIV status, major barriers included a lack of integration between HIV care and cancer care and challenges with referrals between health centers and within departments.13 Prior studies in SSA have demonstrated that patients with HIV who were regularly accessing HIV services had the same likelihood of presenting with advanced cancers as those who did not.2,14 This is a worrisome trend, especially for a cancer such as KS that is often diagnosed on physical exam. Efforts are needed to investigate reasons for this gap through prospective work on knowledge, attitudes and beliefs of HIV providers.

A major limitation to this study is that all patients interviewed had eventually been successfully diagnosed with pathologically confirmed KS. We therefore did not interview patients who had only partially navigated the care cascade, and likely had even more challenging paths to diagnosis. There is the need to additionally interview people in the community who have KS but have not been diagnosed by a clinician to determine barriers they may have faced in accessing KS diagnostic services. An additional limitation is that this study was conducted in a subset of patients enrolled in a larger research study on KS, who likely had additional enabling facilitators for their diagnosis (ie. transportation reimbursement, appointment reminders) compared to a broader patient population. The patients interviewed in this study all lived in Western Kenya and had their care within the AMPATH system, which has care delivery nuances that may not be generalizable to other settings.

In conclusion, our study highlights that there are multiple delays along the care cascade in patients with KS in reaching a diagnosis. Notably, a general lack of KS awareness and education among patients and providers, stigma surrounding both HIV and cancer diagnoses, and health system referral delays were important barriers for patients in receiving a diagnosis of KS. A multi-faceted intervention targeting multiple steps along this cascade is therefore required to improve time to diagnosis. Understanding both the underlying cause of late-stage KS diagnoses and the interventions most appropriately geared to the populations studied is imperative to minimizing the delay of KS diagnosis and optimizing early treatment options.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the interviewed patients

| Characteristic | KS Patients (n=30) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (Median, IQR) | 34 (30–40) |

| Male sex | 25 (83%) |

| Health Facility | |

| Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital | 5 (17%) |

| AMPATH - Chulaimbo | 19 (63%) |

| AMPATH – Busia | 4 (13%) |

| AMPATH – Kitale | 2 (6.7%) |

| Diagnosis Type | |

| Early (T0 stage diagnosis) | 4 (13%) |

| Late (T1 stage diagnosis) | 26 (87%) |

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the research staff: Celestine Lagat, Raphael Kobilo Kipkoir Koima and Elyne Rotich at AMPATH, Eldoret, Kenya who contributed to the collection of data. We also thank Kara Wools-Kaloustian for her mentorship.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) under Award Numbers U01AI069911 (East Africa IeDEA Consortium), K23AI136579, and K24AI141036 and by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) under Award Number U54CA190153 and U54CA254571. Dr. Freeman also received support from a Dermatology Foundation Career Development Award. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Dermatology Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Forman D, et al. Cancer burden in Africa and opportunities for prevention. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4372–4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anakwenze C, Bhatia R, Rate W, et al. Factors Related to Advanced Stage of Cancer Presentation in Botswana. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kingham TP, Alatise OI, Vanderpuye V, et al. Treatment of cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):e158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefan DC. Cancer Care in Africa: An Overview of Resources. J Glob Oncol. 2015;1(1):30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosam A, Shaik F, Uldrick TS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of highly active antiretroviral therapy versus highly active antiretroviral therapy and chemotherapy in therapy-naive patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(2):150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bower M, Dalla Pria A, Coyle C, et al. Prospective stage-stratified approach to AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(5):409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman EE, Semeere A, McMahon DE, et al. Beyond T Staging in the “Treat-All” Era: Severity and Heterogeneity of Kaposi Sarcoma in East Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(5):1119–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu KM, Mahlangeni G, Swannet S, Ford NP, Boulle A, Van Cutsem G. AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma is linked to advanced disease and high mortality in a primary care HIV programme in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2010;13:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grosse Frie K, Kamate B, Traore CB, et al. Factors associated with time to first healthcare visit, diagnosis and treatment, and their impact on survival among breast cancer patients in Mali. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mwaka AD, Garimoi CO, Were EM, Roland M, Wabinga H, Lyratzopoulos G. Social, demographic and healthcare factors associated with stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer: cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Northern Uganda. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e007690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Low DH, Phipps W, Orem J, Casper C, Bender Ignacio RA. Engagement in HIV Care and Access to Cancer Treatment Among Patients With HIV-Associated Malignancies in Uganda. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown CA, Suneja G, Tapela N, et al. Predictors of Timely Access of Oncology Services and Advanced-Stage Cancer in an HIV-Endemic Setting. Oncologist. 2016;21(6):731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espina C, McKenzie F, Dos-Santos-Silva I. Delayed presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer in African women: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(10):659–671 e657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Boer C, Niyonzima N, Orem J, Bartlett J, Zafar SY. Prognosis and delay of diagnosis among Kaposi’s sarcoma patients in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Infect Agent Cancer. 2014;9:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohler RE, Gopal S, Miller AR, et al. A framework for improving early detection of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative study of help-seeking behaviors among Malawian women. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(1):167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mwaka AD, Okello ES, Wabinga H, Walter FM. Symptomatic presentation with cervical cancer in Uganda: a qualitative study assessing the pathways to diagnosis in a low-income country. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moodley J, Cairncross L, Naiker T, Momberg M. Understanding pathways to breast cancer diagnosis among women in the Western Cape Province, South Africa: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e009905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laker-Oketta MO, Wenger M, Semeere A, et al. Task Shifting and Skin Punch for the Histologic Diagnosis of Kaposi’s Sarcoma in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Public Health Solution to a Public Health Problem. Oncology. 2015;89(1):60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semeere A, Wenger M, Busakhala N, et al. A prospective ascertainment of cancer incidence in sub-Saharan Africa: The case of Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer Med. 2016;5(5):914–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter F, Webster A, Scott S, Emery J. The Andersen Model of Total Patient Delay: a systematic review of its application in cancer diagnosis. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012;17(2):110–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher JD, Amico KR, Fisher WA, Harman JJ. The information-motivation-behavioral skills model of antiretroviral adherence and its applications. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2008;5(4):193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bender Ignacio R, Ghadrshenas M, Low D, Orem J, Casper C, Phipps W. HIV Status and Associated Clinical Characteristics Among Adult Patients With Cancer at the Uganda Cancer Institute. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coghill AE, Newcomb PA, Madeleine MM, et al. Contribution of HIV infection to mortality among cancer patients in Uganda. AIDS. 2013;27(18):2933–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fort VK, Makin MS, Siegler AJ, Ault K, Rochat R. Barriers to cervical cancer screening in Mulanje, Malawi: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knettel B, Corrigan K, Cherenack E, et al. HIV, cancer, and coping: The cumulative burden of a cancer diagnosis among people living with HIV. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(6):734–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slaught C, Williams V, Grover S, et al. A retrospective review of patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma in Botswana. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58(6):707–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Bogaert LJ. Clinicopathological Proficiency in the Diagnosis of Kaposi’s Sarcoma. ISRN AIDS. 2012;2012:565463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amerson E, Woodruff CM, Forrestel A, et al. Accuracy of Clinical Suspicion and Pathologic Diagnosis of Kaposi Sarcoma in East Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;71(3):295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McMahon DE, Semeere A, Laker-Oketta M, et al. Global disparities in skin cancer services at HIV treatment centers across 29 countries. J Invest Dermatol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMahon DE, Laker-Oketta M, Peters GA, McMahon PW, Oyesiku L, Freeman EE. Skin Biopsy Equipment Availability Across 7 Low-Income Countries: A Cross-Sectional Study of 6053 Health Facilities. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):462–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]