Abstract

This study proposed, tested, and compared three models to examine an antecedent and outcome of government–public relationships. It conducted three surveys of 9675 people in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong from August 2020 to January 2021. The results of the model comparison supported the proposed reciprocal model: not only were relational satisfaction and relational trust found to mediate the effect of perceived responsiveness on people’s word-of-mouth intention to vaccinate, but they also had a reciprocal influence on each other. This study further affirmed that the relative effects between satisfaction and trust. We also found that emotion-dominant model is more powerful than cognition-dominant model, i.e., people’s feeling of satisfaction happens before sense of trust, which results from their perceived organizational responsiveness and then contribute to their word-of-mouth behavioral intention. The theoretical and practical implications of this study were also discussed.

Keywords: Government–public relationships, Perceived responsiveness, Word-of-mouth intention, Model comparison, COVID-19

Serving as a bridge between government and society, government–public relationships (GPRs) are critical in a crisis situation, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic. One of the major roles of governments in such a situation is to disseminate truthful and up-to-date information on the pandemic to the public and to respond to inquiries. Compared with many other countries and regions, the governments in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong reacted promptly to the pandemic and utilized multiple media platforms (e.g., television, websites, and social media) to provide pandemic-related information to the public, such as traces of infected patients, the number of infected individuals, and health tips. These governments’ disclosure of up-to-date and comprehensive information on the pandemic may account for increasing public satisfaction with the governments’ anti-pandemic efforts (e.g., Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute, 2020). Thus, it is meaningful to examine how these governments responded to the crisis and the impact of this response on the public’s perceived relationships with them.

The focus of GPRs is on establishing and maintaining a positive relationship between the government and the public (Yang, 2018). Public relations researchers have identified the antecedents (e.g., authentic leadership communication) and outcomes (e.g., activism behavior) of GPRs (e.g., Men et al., 2018; Yang, 2018). Few studies, however, have used the model comparison approach to examine the publics’ perceptions of their relationship with the government in non-Western societies, especially in crisis contexts. To fill the gap in the literature and explore the role of GPRs in dealing with the pandemic, this study compares different models on GPRs in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and explores an antecedent and consequence of GPRs through surveys of three Chinese societies.

Although governments have played an important role in combatting the virus, public's cooperation and compliance should also be emphasized in this fight. To control the global COVID-19 pandemic, many governments around the world have encouraged their publics to get vaccinated to achieve herd immunity. Publics’ word-of-mouth (WOM) communication can help governments promote vaccination by recommending it to their friends and relatives. WOM intention indicates the degree to which people want to praise or criticize an organization in a crisis situation, which is viewed as an important outcome when evaluating the communication effectiveness of that organization (Coombs & Holladay, 2008). Thus, WOM intention can be treated as an important goal of risk communication.

This study proposes, tests, and compares three models of GPRs (i.e., emotion-dominant, cognition-dominant, and reciprocal model) to establish a link between perceived responsiveness, relational satisfaction and trust, and positive WOM intention to vaccinate. It conducted three representative surveys of 3444 people in mainland China; 3041 in Taiwan; and 3190 in Hong Kong from August 2020 to January 2021. As one of the few studies to apply the model of organization–public relationships (OPRs) to the context of GPRs in crisis through a model comparison approach, this study contributes to the development of this theoretical model by identifying a new predictor (i.e., perceived responsiveness) and outcome (i.e., positive WOM intention to vaccinate) of GPRs and examining the mediating mechanism. It also advances the bodies of knowledge on GPRs, organizational responsiveness, and WOM and provides an effective framework for understanding the quality of GPRs. In terms of practical implications, the final model of GPRs can be used to evaluate public relations effectiveness. This study also provides strategies for governments to build good relationships with the public as they work to resolve the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Literature review

1.1. Organization–public relationships and government–public relationships

Relationship management is a research paradigm in the field of public relations (Ledingham & Bruning, 2000). OPRs are defined as “the degree that the organization and publics trust one another, agree on who has rightful power to influence, experience satisfaction with each other, and commit one-self to one another” (Huang, 2001, p. 65). Public relations scholars have identified four typical dimensions of OPRs: trust, satisfaction, control mutuality, and commitment (Grunig & Huang, 2000).

Based on the conceptualization and four dimensions of OPRs, scholars have proposed and tested a model of OPRs that consists of relationship antecedents, relationship maintenance strategies, and relationship outcomes (Broom et al., 1997, Broom et al., 2000). According to Broom et al. (1997), relationship antecedents refer to contingencies or factors in the establishment of a relationship and include sources of change and pressure, driving organizations to develop relationships with the public. Relationship maintenance strategies refer to the strategies used by organizations to establish and maintain relationships and include assurances, openness, positivity, social networks, and sharing of tasks (Canary and Stafford, 1992, Canary and Stafford, 1994, Hon and Grunig, 1999). Relationship outcomes indicate the outcomes of relationship maintenance strategies (Grunig & Huang, 2000) and are related to “achieving, maintaining or changing goal states both inside and outside the organization” (Cutlip et al., 1994, p. 213).

The scope of OPR research has been expanded to many specific types of OPRs, such as employee–organization relationships (Wang, 2020), organization–volunteer relationships (Harrison et al., 2017), and GPRs (Chon, 2019, Liu and Huang, 2021). GPRs refer to the relationship between the government and the public (Yang, 2018). Compared with the four dimensions of OPRs, GPR research focuses on the dimensions of trust and satisfaction (Hong et al., 2012, Kim, 2015, Men et al., 2018). Because trust and satisfaction are considered key indicators of GPRs and the effectiveness of political public relations (Hong et al., 2012, Men et al., 2018). Men et al. (2018) also conceptualized GPRs as publics’ trust in and satisfaction with the government. Thus, this study operationalizes GPRs as relational trust and satisfaction. Institutional trust is conceptualized as individuals’ trust in political organizations (Wang, 2013), which is an important concept for measuring OPR performance (Easton, 1975). Satisfaction refers to “the extent to which each party feels favorably toward the other because positive expectations about the relationship are reinforced” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 3).

Public relations researchers have investigated the antecedents and effects of GPRs in various contexts. For instance, Men et al. (2018) examined presidential political communication on social media and found that both authentic and responsive leadership communication had positive effects on GPRs. Yang (2018) examined the antecedents and effects of negative GPRs during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak and found that negative GPRs could indirectly elicit activism behaviors among the public through relationship dissolution intention. In a crisis context, Chon (2019) documented that citizens’ trust in their government led them to advocate for the government. More recently, the role of GPRs in emergency management has also attracted scholars’ attention. For example, Liu and Ni (2021) highlighted the importance of GPRs in disaster management, suggesting that the quality of GPRs was positively associated with the belief that the public and the community could cope with the disaster. In this vein, this study focuses on examining perceived responsiveness as an antecedent and WOM intention to vaccinate as an outcome variable.

1.2. Perceived responsiveness

Researchers have explored the relationship between GPRs and responsiveness. Responsiveness is one of the critical factors in dialogic communication (McAllister, 2013) and is defined as “an organization’s willingness and ability to respond to referrals by individual public members” (Avidar, 2013, p. 442). This study focuses on the public’s perception and evaluation of their government’s behavior rather than on how the governments actually responded to particular issues; thus, this construct is conceptualized as perceived responsiveness (Huang et al., 2020). Scholars have concluded that responsiveness is beneficial to OPRs because being responsive creates the perception that organizations care about the needs of their publics and respond accordingly with action (Avidar, 2013, Stromer-Galley, 2000). When an organization faces a crisis, its legitimacy can be threatened if perceived responsiveness is insufficient (Seeger & Ulmer, 2002). More recently, Huang et al. (2020) suggested that responsiveness should be viewed as an antecedent of a relationship, especially in a dialogic communication process. Thus, it is plausible to argue that if publics perceive a government to be responsive, they will be more likely to be satisfied with and trust in the government, which may then help the government to survive in a crisis. Therefore, the following two hypotheses are proposed.

H1a

: Publics’ perception of governmental responsiveness is positively related to their satisfaction with the government.

H1b

: Publics’ perception of governmental responsiveness is positively related to their trust in the government.

1.3. Word-of-mouth intention to vaccinate

In addition to an antecedent of GPRs, the current study identifies the public’s WOM intention to vaccinate as a relationship outcome in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Harrison-Walker (2001) defined WOM as the “informal, person-to-person communication between a perceived noncommercial communicator and a receiver regarding a brand, a product, an organization, or a service” (p. 70). Scholars have examined the impact of WOM on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors (e.g., Herr et al., 1991; Murray, 1991). Wang et al. (2017) examined the predictors of WOM communication and found that college students’ identification with their university and use of university social media influenced their WOM communication about the university. Public’s WOM intention to recommend an organization was also found to be positively associated with public’s perceived relational satisfaction of the organization, which is one of the key elements of GPRs (Hong & Yang, 2009). In this study, the public’s positive WOM intention to vaccinate is conceptualized as making positive recommendations about the COVID-19 vaccine to others including family and friends.

The current study examines the relationship between GPRs and positive WOM intention to vaccinate. As suggested by previous research, positive OPRs can lead to an organization’s favorable reputation and its publics’ supportive behavior (Bruning, 2002, Yang and Grunig, 2005). Hong and Yang (2011) examined the relationship between OPRs and consumers’ communication behaviors and documented that their relational satisfaction had a positive effect on their positive WOM communication. Focusing on a special type of OPRs (i.e., GPR), recent studies (e.g., Chon & Park, 2021; Liu & Huang, 2021) have also demonstrated that GPRs positively influence the public’s adherence to the government’s instructions for dealing with infectious disease. Liu and Huang (2021) found that GPRs could boost the public’s supportive attitude toward vaccines and facilitate their vaccination intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that GPRs include two key dimensions (i.e., satisfaction and trust), we thus assume that relational satisfaction and trust also influence positive WOM intention to vaccinate. During the COVID-19 pandemic, if publics feel satisfied with and trust in their government, they would tend to help the government recommend the COVID-19 vaccines to their friends and family members. Therefore, we posit the following two hypotheses.

H2a

The publics’ satisfaction with the government is positively associated with their positive WOM intention to vaccinate.

H2b

The publics’ trust in the government is positively associated with their positive WOM intention to vaccinate.

Because responsiveness is considered a critical strategy of relationship management (Kent et al., 2003), it is plausible to predict that responsiveness has an impact on relationship outcomes, such as WOM intention of vaccination. According to Rim and Song (2013), being responsive can make publics feel stronger connections to an organization, resulting in more favorable attitudes and WOM intentions toward the organization. Therefore, if publics think that their government responds to their inquiries and concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic, they are more likely to recommend that their friends get vaccinated. The following hypothesis is thus proposed.

H3

: The publics’ perception of the government’s responsiveness is positively related to their positive WOM intention to vaccinate.

1.4. Affect (relational satisfaction) and cognition (relational trust)

In addition to examining the antecedent and outcome of GPRs, this study goes a step further to explore the relationship of the two GPR dimensions—satisfaction and trust. Satisfaction and trust can be viewed as affective and cognitive appraisal processes, respectively (Huang, 2001). Before a person takes a certain action to react to an issue, his/her appraisal processes may involve either affective or cognitive evaluation (Arnold, 1960, Lazarus, 2001). Although the relationship between affect and cognition has long been studied, it still generates intense debate and mixed findings (Forgas, 1995, Lazarus, 2001). There are two competing schools of thought regarding the directionality of cognition and affect: one considers cognitive appraisal processes to determine the affect; the other claims the opposite, that affective appraisal processes determine cognition.

1.4.1. Cognition as an antecedent of affect

Cognitive appraisal theory (CAT) suggests that emotions/affects are triggered by a certain relationship between people and their environment (Lazarus, 1991, Lazarus, 2001). For instance, when people perceive threat or uncertainty from a circumstance, negative emotions such as fear are evoked, whereas a benign appraisal would result in positive emotions (Lazarus, 1991). CAT theorists contend that individuals must know the ontological category before a certain affective assessment can be activated (Lai et al., 2012). In the setting of a health crisis, Chon and Park (2021) demonstrated that cognitive appraisal processes resulted in emotions and further influence people’s behavior. If we assume that trust (cognitive appraisal) precedes satisfaction (affective appraisal), it would mean that publics first deal with an organization based on their prior experiences and then become satisfied once the organization’s performance meets their expectations (Chang, 2006, Chinomona and Sandada, 2013).

1.4.2. Cognition as a consequence of affect

A contradictory perspective suggests that cognitive appraisal comes after the affective/emotional process (e.g., Forgas, 1995). In contrast to the cognitivist paradigm, the affective primacy hypothesis claims that affective information processing is activated automatically (Lai et al., 2012). According to Schwarz (2011), feelings (i.e., emotions) can be treated as a source of information. Before reacting to a certain task, we may ask ourselves: “How do I feel about it?” The answer could be leveraged as the justification for the actions we may take (Forgas, 2008). Adopting this perspective, Jo (2018) tested the causal link between different OPR dimensions and inferred that satisfaction led to trust in the context of the relationship between university and students. This relationship has also been proved in business settings (Høgevold et al., 2020). If we adopt the view of the affective primacy hypothesis, we could say that publics might be satisfied with the organization’s performance, and then trust would be fostered (Jo, 2018, Lai et al., 2012).

1.5. The mediating roles of relational satisfaction and trust

Although both CAT and the affective primacy hypothesis have been supported by empirical studies, the question of this directionality is still underexplored in the context of crises and risks, especially from the perspective of relationship management. Thus, this study focuses on the directionality of relational satisfaction (affect) and trust (cognition). Satisfaction means the public’s favorable affective response toward the organization because the public’s expectation is fulfilled by the organization’s undertakings (Hon and Grunig, 1999, Huang, 2001, Men and Muralidharan, 2017). Unlike satisfaction, which emphasizes more affective aspects, trust is referred to as “one party’s level of confidence in and willingness to open oneself to the other party” (Hon & Grunig, 1999, p. 19), which in a pandemic situation, is mostly based on the other party’s ability, competencies, or skills in dealing with the risk (Mayer et al., 1995). The relationship (including the sequential relationship) between satisfaction and trust, however, has rarely been studied. Lu and Huang (2018) called for scholarly attention to be focused on the emotion-dominant and cognition-dominant patterns through which people process crisis information. Researchers have investigated the interrelations between OPR dimensions but have not reached an agreement. On the one hand, Jo (2018) found that satisfaction preceded trust and that both would drive people’s commitment. In contrast, Bruning and Ledingham (1998) demonstrated that satisfaction would be influenced by the existing relationship, which included trust, involvement, and commitment. On the other hand, Welch et al. (2004) indicated that the publics’ satisfaction with and trust in a government have a reciprocal relationship. In sum, there are three perspectives on the relationship between satisfaction and trust: (1) satisfaction affects trust, (2) trust has an impact on satisfaction, and (3) both constructs influence each other reciprocally (Weber et al., 2017).

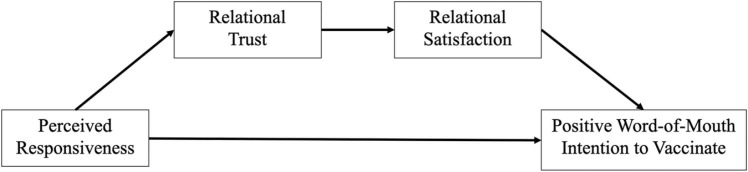

This study explores the directionality of the two dimensions of GPRs in the context of the pandemic by proposing and comparing three alternative models: the emotion-dominant model (Model 1), the cognition-dominant model (Model 2), and the reciprocal model (Model 3). As shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, the emotion-dominant model suggests that individuals’ affect (relational satisfaction) is activated earlier than cognition before taking a certain action (e.g., getting vaccinated during the COVID-19 pandemic), the cognition-dominant model suggests that cognition (relational trust) is activated before affect, whereas the reciprocal model focuses on the reciprocal relationship between affect and cognition.

Fig. 1.

Emotion-Dominant Model (Model 1).

Fig. 2.

Cognition-Dominant Model (Model 2).

Fig. 3.

Reciprocal Model (Model 3).

As discussed above, both relational satisfaction and trust are influenced by perceived responsiveness, and they have positive effects on positive WOM intention to vaccinate. Thus, it would be valuable to examine whether relational satisfaction or trust would be the first mediator in the relationship between perceived responsiveness and positive WOM intention to vaccinate. Moreover, according to Lai et al. (2012), this causal link might be issue-sensitive. Thus, it would be meaningful to investigate the relationship between publics’ satisfaction with and trust in the government in the context of a public health crisis (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic). The following two research questions are proposed.

RQ1

: What is the relationship between relational satisfaction and trust?

RQ2

: Which is the most robust among the following three models: (1) perceived responsiveness → relational satisfaction → relational trust → positive WOM intention to vaccinate (Model 1); (2) perceived responsiveness → relational trust → relational satisfaction → positive WOM intention to vaccinate (Model 2); or (3) perceived responsiveness → relational satisfaction ←→ relational trust → positive WOM intention to vaccinate (Model 3)?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The study population comprised individuals aged 20 and over in three Chinese societies (i.e., mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong). These three societies are chosen for two reasons. First, although the three societies share similar Confucianism culture that highly values relationship and guanxi to a great extent (Huang, 2001), which are pertinent for this study that examines the relationship-related topic, they have different political systems and disease control regulations (Triandis, 2001). Thus, if similar patterns can be found in these three societies, the proposed theoretical model then will have the most robust explanation. Second, the COVID-19 pandemic contexts in the three regions were different at the time of data collection: mainland China witnessed a small number of new COVID-19 cases due to its stringent measures (Xu et al., 2020); Taiwan confirmed only a few hundred new cases with the help of its general screening strategy (Su et al., 2020); and Hong Kong went through three pandemic waves and reported approximately 5000 confirmed cases and 100 deaths (Jung et al., 2021), which were relatively high in the Greater China area.

Two third-party agencies were contracted to recruit participants. Rakuten Insights was hired to collect panel participants’ data in mainland China and Hong Kong, where it manages more than 3.2 million and 50,000 registered panelists, respectively. The researchers asked the Chungliu Education Foundation to recruit participants in Taiwan because it could also cover more rural areas of Taiwan to enhance the representativeness of our sample. In mainland China, taking into account the broad territory, we first conducted probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling to identify the target cities. Then stratified quota sampling was adopted based on the genders, ages, and residency status of the population shown in the 2010 census of mainland China. In Taiwan, we used random digit dialing (RDD) method to invite participants according to the 2020 household registration database. In Hong Kong, we utilized stratified quota sampling based on the distribution of genders, ages, and residency status in the 2016 census of Hong Kong.

2.2. Pretest

After obtaining ethical approval for the involvement of human subjects in this study, the researchers conducted pretests with 10 students in each region. They completed the survey questionnaire and provided their comments on it. The wording of the questionnaire was modified based on their comments to ensure instrument validity.

2.3. Main study

The researchers conducted three surveys, one in each of the three selected Chinese societies, from August 2020 to January 2021. The research firms randomly selected qualified respondents from their panels and invited them to participate in a Web-based survey posted on Qualtrics (for the mainland Chinese and Hong Kong participants) and SurveyCake (for the Taiwanese participants). A total of 9675 valid responses (mainland China: n = 3444; Taiwan: n = 3041; and Hong Kong: n = 3190) were collected. The firms were paid for recruiting the respondents, who were provided a monetary incentive to complete the survey.

2.4. Measurement

All of the variables in this study were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

2.4.1. Perceived responsiveness

To operationalize perceived responsiveness, a 4-item scale was adapted and modified from Huang (2008) research. The participants were instructed to think about and indicate to what extent they agreed with three statements regarding the handling of COVID-19 by the disease control and prevention authorities in their respective regions; for example: “they provide accurate information.” The levels of reliability were 0.81 for the mainland Chinese data, 0.95 for the Taiwanese data, and 0.95 for the Hong Kong data.

2.4.2. Relational satisfaction

Seven items adapted from Lazarus et al. (2020) were used to assess participants’ satisfaction with governmental anti-pandemic work. The participants were asked how satisfied they were with the performance of the disease control and prevention authorities in carrying out such tasks as “preventing the spread of the pandemic.” The levels of reliability were 0.89 (mainland China), 0.96 (Taiwan), and 0.96 (Hong Kong).

2.4.3. Relational trust

The study adapted the scale of institutional trust in ability developed by prior researchers (Mayer and Davis, 1999, Mayer et al., 1995) to measure relational trust with five items, such as “they are capable of performing their jobs” (mainland China: Cronbach’s α = 0.85, Taiwan: Cronbach’s α = 0.96, and Hong Kong: Cronbach’s α = 0.96).

2.4.4. Positive WOM intention to vaccinate

Positive WOM intention to get vaccinated was captured by three items adapted from Coombs and Holladay (2008), such as “if relatives or friends turned to me for advice, I would encourage them to get the vaccine.” The levels of reliability were 0.81 (mainland China), 0.96 (Taiwan), and 0.96 (Hong Kong).

2.4.5. Control variables

Our study used demographic variables including gender, education, and income level as covariates to control for extraneous effects. Political stance was also included as a control variable because it is proven to be related to citizens’ willingness to get vaccinated (Ward et al., 2020).

2.5. Statistical procedures for data analysis

This study used path analysis to test the proposed hypotheses and answer the research questions. According to Schumacker and Lomax (2016), chi-square and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) should be reported for any model. The comparative fit index (CFI), the Bentler–Bonett normed fit index (NFI), and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) are typically used for comparing alternative models (Schumacker & Lomax, 2016). These five model fit indices were reported for each model to test its fitness with the data and compare the three models. We did not use the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), mainly because the degrees of freedom for the three models were 2, 2, and 1, respectively. Kenny et al. (2015) recommended not using RMSEA to access the fit of SEM models with low degrees of freedom. This study also made use of the chi-square difference test, which can determine which model has the best and significant fit with the data compared with other models (Bentler and Bonnett, 1980, Werner and Schermelleh-Engel, 2010). In addition, the percentage of each model’s significant hypothesized parameters were calculated for the sake of model comparison (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).

3. Results

3.1. Dataset 1: Mainland China

The participants of the survey conducted in mainland China had a balanced gender distribution with 51.3% being female (n = 1766) and 48.7% being male (n = 1678). Approximately half of the participants (51.7%, n = 1779) were aged 40 and above. Most of the participants (67.4%, n = 2320) had a monthly income of CNY $5001–25,000 (USD $765–3823). Over half of them (59.9%, n = 2063) held a Bachelor’s degree or above.

3.1.1. Correlation Analysis

A correlation analysis of the mainland Chinese data was conducted to examine the relationships between the independent and dependent variables. Table 1 shows that the correlations between perceived responsiveness, relational satisfaction, relational trust, and positive WOM intention to vaccinate ranged from.58 to.78 at the.01 significance level. Thus, all of these variables were included in the subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix for the Key Variables in the Mainland Chinese Data.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived responsiveness | 5.60 | .88 | – | |||

| 2. Relational satisfaction | 5.57 | .89 | .78 * * | – | ||

| 3. Relational trust | 5.56 | .89 | .73 * * | .77 * * | – | |

| 4. Positive WOM intention | 5.46 | 1.01 | .61 * * | .58 * * | .59 * * | – |

Note. * * p < .01 (2-tailed)

3.1.2. Path analysis

We performed path analysis to test the three proposed models. As shown in Table 2, Model 3 had the highest CFI, NFI, and TLI and lowest SRMR among the three proposed models. According to Hu and Bentler (1999) criteria for model fit indices, Model 3 fitted with the data satisfactorily. Models 1 and 2 had five significant paths, whereas Model 3 had six significant paths. Furthermore, a chi-square difference test comparing the first two models and Model 3 indicated that Model 3 fitted the data significantly better than Models 1 [Δχ 2 (1) = 366.514, p < .001] and 2 [Δχ 2 (1) = 1166.579, p < .001]. Given that Models 1 and 2 had the same degree of freedom, their chi-square test differences could not be assessed. In sum, Model 3 showed the best fit with the data from mainland China among the three models.

Table 2.

Fit Indices of the Three Models for the Three Datasets: Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

| Mainland China |

Taiwan |

Hong Kong |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| χ2 (df) | 390.308 (2) | 1190.373 (2) | 23.794 (1) | 267.691 (2) | 1179.403 (2) | 27.479 (1) | 228.978 (2) | 849.291 (2) | 42.692 (1) |

| CFI | .953 | .857 | .997 | .966 | .848 | .997 | .971 | .892 | .995 |

| NFI | .953 | .857 | .997 | .965 | .848 | .996 | .971 | .892 | .995 |

| TLI | .860 | .571 | .984 | .897 | .544 | .979 | .913 | .676 | .968 |

| SRMR | .048 | .089 | .011 | .031 | .068 | .013 | .032 | .063 | .015 |

| Δχ2 (Δdf) | 366.514 (1)* ** | 1166.579 (1)* ** | – | 240.212 (1)* ** | 1151.924 (1)* ** | – | 186.286 (1)* ** | 806.599 (1)* ** | – |

Note. * ** p < .001.

H1 predicted that a public’s perception of the responsiveness of the government positively influenced its satisfaction with and trust in the government. The results of the path analysis suggested that perceived responsiveness was a significant positive predictor of relational satisfaction (β = 1.21, p < .001) and trust (β =.74, p < .001). Thus, H1 was supported. H2 posited that relational satisfaction and trust were positively associated with positive WOM intention to vaccinate. This study found that both relational satisfaction (β =.29, p < .001) and trust (β =.37, p < .001) significantly positively affected positive WOM intention to vaccinate, which supported H2. H3 posited that perceived responsiveness was a positive predictor of positive WOM intention to vaccinate. Perceived responsiveness significantly influenced positive WOM intention to vaccinate (β =.44, p < .001). Thus, H3 was supported. RQ1 focused on the relationship between relational satisfaction and trust. The results indicated that relational satisfaction had a significant positive impact on relational trust (β =.94, p < .001), whereas relational trust also significantly affected satisfaction (β = −0.56, p < .001).

A bootstrap procedure (n = 5000 samples) was conducted to estimate possible indirect effect. RQ2 posited that relational satisfaction and trust mediated the relationship between perceived responsiveness and positive WOM intention to vaccinate. The results provided supportive evidence of the mediating effect (β = 0.21, p < .001, 95% CI [.184,.247]).

3.2. Dataset 2: Taiwan

Among the participants of the survey conducted in Taiwan, 56.1% were female (n = 1706) and 43.9% were male (n = 1335). Approximately one third of participants (29.3%, n = 890) were aged 40 and above. More than half of them (55.8%, n = 1697) had a monthly income of NT $50,001 and above (USD $1752). Their education levels were high, with 87.6% (n = 2664) having a Bachelor’s degree or above.

3.2.1. Correlation analysis

The researchers conducted a correlation analysis of the Taiwanese data. As shown in Table 3, the results of the correlation analysis ranged from.34 to.84. Thus, all of the independent variables were significantly correlated with all of the dependent variables at the significance level of.01.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix for the Key Variables in the Taiwan Data.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived responsiveness | 4.85 | 1.16 | – | |||

| 2. Relational satisfaction | 4.90 | 1.16 | .84 * * | – | ||

| 3. Relational trust | 5.02 | 1.19 | .78 * * | .82 * * | – | |

| 4. Positive WOM intention | 4.43 | 1.24 | .34 * * | .36 * * | .34 * * | – |

Note. * * p < .01 (2-tailed)

3.2.2. Path analysis

Path analysis was conducted to test the three models. As shown in Table 2, Model 3 also exhibited a better fit with the Taiwan data than did the other two models, because it had the highest CFI, NFI, and TLI, the lowest SRMR, and the largest number of significant paths. Moreover, a chi-square difference test suggested that Model 3 had a significantly better fit with the data than Models 1 [Δχ 2 (1) = 240.212, p < .001] and 2 [Δχ 2 (1) = 1151.924, p < .001].

The results of our path analysis indicated that perceived responsiveness significantly positively influenced relational satisfaction (β = 1.15, p < .001) and trust (β =.76, p < .001). Therefore, H1 was supported. Both relational satisfaction (β =.27, p < .001) and trust (β =.55, p < .001) significantly positively influenced positive WOM intention to vaccinate, which supported H2. Our results also suggested that perceived responsiveness significantly positively influenced positive WOM intention to vaccinate (β =.21, p < .001). Therefore, H3 was supported. Regarding RQ1, relational satisfaction was found to have a significant positive impact on relational trust (β =.95, p < .001), and relational trust was found to significantly influence relational satisfaction (β = -.41, p < .001). We used a bootstrap procedure (n = 5000 samples) to test the indirect effect proposed in RQ2. The relationship between perceived responsiveness and positive WOM intention to vaccinate was significantly mediated by relational satisfaction and trust (β = 0.13, p < .001, 95 % CI [.097,.170]).

3.3. Dataset 3: Hong Kong

Over half of the participants in Hong Kong were female (56.6%, n = 1805) and 43.4 % were male (n = 1385). About one third of the participants (32.7%, n = 1044) were 50 years old or above. Approximately one fifth of them had a high monthly income, with 22.6 % (n = 722) earning more than HKD $60,000 (USD $7723). Over half of them (52.9%, n = 1688) held a Bachelor’s degree or above.

3.3.1. Correlation Analysis

We performed a correlation analysis for the Hong Kong data. As shown in Table 4, the results ranged from.43 to.82 at the.01 significance level. Thus, all of the variables were included in the path analysis.

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix for the Key Variables in the Hong Kong Data.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived responsiveness | 4.38 | 1.27 | – | |||

| 2. Relational satisfaction | 3.97 | 1.36 | .79 * * | – | ||

| 3. Relational trust | 4.20 | 1.36 | .74 * * | .82 * * | – | |

| 4. Positive WOM intention | 4.26 | 1.41 | .46 * * | .46 * * | .43 * * | – |

Note. * * p < .01 (2-tailed)

3.3.2. Path analysis

As shown in Table 2, likewise, Model 3 showed the best fit with the Hong Kong data among the three proposed models, as it had the highest CFI, NFI, and TLI, the lowest SRMR, and the largest number significant paths. In addition, a chi-square difference test indicated that Model 3 fitted the data significantly better than Models 1 [Δχ 2 (1) = 186.286, p < .001] and 2 [Δχ 2 (1) = 806.599, p < .001]. The results of the path analysis indicated that perceived responsiveness significantly positively affected relational satisfaction (β = 1.28, p < .001) and trust (β =.79, p < .001), supporting H1. This study also found that relational satisfaction (β =.25, p < .001) and trust (β =.19, p < .001) had significant positive impacts on positive WOM intention to vaccinate. Therefore, H2 was supported. In addition, perceived responsiveness significantly affected positive WOM intention to vaccinate (β =.36, p < .001), supporting H3. Regarding RQ1, relational satisfaction was a significant positive predictor of relational trust (β =.95, p < .001), and trust also significantly influenced satisfaction (β = -.55, p < .001). The researchers used a bootstrap procedure (n = 5000 samples) to assess the mediating relationship posited in RQ2. Relational satisfaction and trust significantly mediated the relationship between perceived responsiveness and positive WOM intention to vaccinate (β = 0.11, p = .001, 95% CI [.080,.143]).

4. Discussion

Over the last 20 years, OPRs have become a paradigm in the field of public relations (Wang, 2020), which include GPRs. Although GPRs have been extensively studied (e.g., Hong, 2013; Kim, 2015), few studies have covered the topic of GPRs in the context of a crisis (e.g., Chon, 2019). This study advances the literature by examining GPRs in the context of a public health crisis. It also explored the relationship between different dimensions of GPRs (i.e., satisfaction and trust) by comparing three different models.

Leveraging three surveys, which includes 3444 respondents in mainland China, 3041 in Taiwan, and 3190 in Hong Kong, this study explored the mechanisms through which a government’s responsiveness can influence its publics’ perceived relationship (satisfaction and trust) with it and their resulting positive WOM intention to vaccinate during crises. Specifically, it proposed, tested, and compared three models of the relationships between perceived responsiveness, relational satisfaction, relational trust, and positive WOM intention to vaccinate.

4.1. Similar patterns across three Chinese societies: reciprocal model as the most dominant, followed by emotion-dominant model

We found two major patterns across three Chinese societies. First, the results of the model comparison suggested that relational satisfaction and trust have a reciprocal relationship during crises, which extends previous research on OPRs that documented unidirectional relationships between satisfaction and trust (e.g., Jo, 2018). It is worth noting that the effect of satisfaction on trust is stronger than the reverse effect. This finding contributes to the perspective about the reciprocity and relative effects of satisfaction and trust and strengthens our understanding of the dynamics involved (Weber et al., 2017). Given that relational satisfaction and trust are respectively considered as affective and cognitive appraisal processes (Huang, 2001), our finding implies that the public’s affective and cognitive appraisals may influence each other reciprocally during crises. Thus, a government could exert efforts to make its public feel satisfied with it or trust it during crises, which could influence one another.

The second pattern across three Chinese societies, which is affective primary hypothesis or emotion-dominant model (i.e., satisfaction comes before trust), has more predictive power than cognitive appraisal theory or cognition-dominant model (i.e., trust comes before satisfaction). We found that publics’ perception of the responsiveness of their government can first lead to their satisfaction with it, which then results in their institutional trust. Publics’ positive WOM intention regarding vaccines is then influenced by this sense of trust in the government. Our findings contribute to the knowledge involving the sequence and relative power between relational satisfaction and relational trust in OPRs in general and GPRs in particular.

4.2. Perceived organizational responsiveness as a powerful antecedent of positive GPRs

One major finding of this study was that a public’s perception of the responsiveness of its government influences their satisfaction with it. This finding is similar to those of previous studies, which have documented that an organization’s responsiveness led its publics to trust it (Huang et al., 2020). One possible explanation for this result is that publics who feel that their government provides accurate and useful information to them during crises are more likely to be satisfied with their government. According to Xie et al. (2017), the most in-demand information during a crisis includes the latest updates on the crisis, its cause and impact, and its relationship with the public’s self-interests. During a pandemic, it is important for a government to provide truthful and up-to-date information about the crisis to the public and to respond to questions, which can increase the public’s degree of satisfaction with the government.

4.3. Word-of-mouth intention as an important outcome variable for GPRs

Another important finding was that a public’s trust in its government influences positive WOM intention to vaccinate during the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding coincides with previous studies that have documented that favorable OPRs lead to the public’s supportive behaviors (e.g., Bruning, 2002; Yang & Grunig, 2005). The current study enriches the OPR scholarship by considering GPRs in the context of a public health crisis and examining an antecedent and outcome. This study also found that a public’s perception of the responsiveness of their government has an effect on positive WOM intention to vaccinate during a public health crisis. If publics trust their government and perceive that it responds to their inquiries and concerns on COVID-19 and its vaccines, they are more likely to recommend that their friends and relatives get the vaccines regardless of their political stance, as encouraged and promoted by the government. Thus, governments can make efforts to gain the public’s trust to motivate them to recommend COVID-19 vaccines, which would help facilitate vaccine promotion and pandemic control. Furthermore, the relationships between relational trust and perceived responsiveness and positive WOM intention to vaccinate are weaker among the public of Hong Kong than that of mainland China. One possible explanation is that the Hong Kong public holds more individualistic values, whereas the mainland Chinese public has more collectivistic values (Chen & Tjosvold, 2007). Thus, the Hong Kong public might not actively help the government to promote vaccines during the pandemic even if they trust the government and it is responsive, whereas those from mainland China might be more willing to do so.

4.4. Relationship-mediating model

This study went a step further than prior research by identifying relational satisfaction and trust as mediators, which can further be understood as a relationship-mediating model. Specifically, we documented the indirect effect of perceived responsiveness on positive WOM intention to vaccinate through relational satisfaction and trust. The results of our model comparison suggested that if the publics perceive the government to be responsive, they are more likely to feel satisfied with and trust the government, which motivate them to help it promote the vaccines. This finding can be explained by the model of OPRs, where relationship maintenance strategies mediate the effect of relationship antecedents on outcomes (Broom et al., 1997). One possible explanation is that an organization’s public relations efforts (e.g., responsive communication) may influence the publics’ emotions (satisfaction) first and then their cognition (trust), which also affect each other, leading to their supportive behavioral intention (e.g., positive WOM intention to vaccinate). In addition, given that many governments throughout the world have been encouraging the public to get the COVID-19 vaccines, they need to respond to the public’s questions and concerns about the pandemic and vaccines to make the public feel satisfied and to trust them, which can facilitate positive WOM about the vaccines.

This study contributes to literature by empirically testing the relationships between perceived responsiveness, relational satisfaction, relational trust, and positive WOM intention to vaccinate in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and identifying new mediating mechanisms (i.e., the mediating effect of relational satisfaction and trust). As one of the few studies to compare different models of the GPR mechanism, this study proposed and compared an emotion-dominant, cognition-dominant, and reciprocal model and cross-validated them in three Chinese societies. It contributes to the model of OPRs by identifying a new antecedent and outcome of GPRs and examining the relationship between the dimensions of GPRs. It also advances the research on GPRs, organizational responsiveness, government communication, and WOM by providing an Eastern perspective, as those concepts had mainly been examined in the Western context before.

The results of this study are of great value for communication practitioners working in governments. Overall, nurturing a favorable relationship with the public via being responsive can significantly influence the outcomes of public relations efforts when a crisis occurs. In particular, developing a good relationship with the public can facilitate positive WOM intentions in a crisis. Governments in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are recommended to continue to take action to respond to their publics’ inquiries and comments about the COVID-19 pandemic, provide truthful information to them, and make them feel satisfied with the governments, which would be helpful for vaccine promotion and pandemic control. For instance, these governments can use social media to disseminate up-to-date information to the public, listen to opinions, and respond to inquiries (Men & Tsai, 2014), especially during crises.

4.5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be addressed. First, the findings of this study were generated from samples of the population in mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Thus, they may not be generalizable to other countries or regions. Second, although the current study conducted three surveys, it used cross-sectional data, which cannot support the causal relationships revealed in the models. Therefore, its findings should be interpreted with caution. Third, although this study controlled for demographic variables in the proposed model, participants’ pre-existing attitudes toward vaccination and previous vaccination history were not controlled for, which might be factors that influence their vaccination intention (Setbon & Raude, 2010).

4.6. Future research

Future researchers could examine the relationships between perceived responsiveness, OPRs, and positive WOM intention in various organizations (e.g., corporations and nonprofit organizations). They could also conduct cross-cultural comparative studies in different nations (e.g., Western countries) to determine whether and how cultural factors influence those relationships. Scholars are encouraged to empirically test and compare the proposed models in other contexts (e.g., organizational misdeeds and natural disasters). They could conduct surveys or experiments to explore other potential antecedents and outcomes of GPR quality, such as the use of government social media or public advocacy. In addition, future studies are suggested to control for individuals’ pre-existing attitudes toward vaccines and prior vaccination history in the proposed models, given that their vaccination intention may be rooted in their belief systems (Streefland, 2001).

Funding

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from City University of Hong Kong (Project No. 9380119). They provided financial support for data collection in this study.

Declarations of interest

None.

Biographies

Yuan Wang (Ph.D., The University of Alabama) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Media and Communication at City University of Hong Kong. His research interests focus on the role of new media (e.g., social media, mobile phone, and virtual reality) in public relations processes and outcomes through social scientific approaches. He has published numerous articles in peer-reviewed journals, such as Public Relations Review, International Journal of Strategic Communication, Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, New Media & Society, and Nonprofit Management and Leadership.

Yi-Hui Christine Huang (Ph.D., University of Maryland), ICA Fellow, is a Chair Professor of Communication and Media at the Department of Media of Communication, City University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include public relations management, crisis communication, conflict and negotiation, and cross-cultural communications and relationship. She has served as Editor for Communication and the Public and Communication and Society, and Senior Associate Editor for Journal of Public Relations Research.

Qinxian Cai (M.A., The Chinese University of Hong Kong) is a doctoral student in the Department of Media and Communication at City University of Hong Kong. His research interests include strategic communication, crisis management, and risk communication. His research has been published in Negotiation and Conflict Management Research and International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Data Availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Arnold M.B. Columbia University Press; 1960. Emotion and personality. [Google Scholar]

- Avidar R. The responsiveness pyramid: Embedding responsiveness and interactivity into public relations theory. Public Relations Review. 2013;39(5):440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M., Bonnett D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88(3):588–606. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broom G.M., Casey S., Ritchey J. Toward a concept and theory of organization–public relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research. 1997;9(2):83–98. doi: 10.1207/s1532754xjprr0902_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broom G.M., Casey S., Ritchey J. In: Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations. Ledingham J.A., Bruning S.D., editors. Routledge; 2000. Concept and theory of organization–public relationships; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bruning S.D. Relationship building as a retention strategy: Linking relationship attitudes and satisfaction evaluations to behavioral outcomes. Public Relations Review. 2002;28(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00109-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruning S.D., Ledingham J.A. Organization-public relationships and consumer satisfaction: The role of relationships in the satisfaction mix. International Journal of Phytoremediation. 1998;15(2):198–208. doi: 10.1080/08824099809362114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canary D.J., Stafford L. Relational maintenance strategies and equity in marriage. Communication Monographs. 1992;59(3):243–267. doi: 10.1080/03637759209376268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canary D.J., Stafford L. In: Communication and relational maintenance. Canary D.J., Stafford L., editors. Academic Press; 1994. Maintaining relationships through strategic and routine interaction; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chang J.C. Customer satisfaction with tour leaders’ performance: A study of Taiwan’s package tours. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research. 2006;11(1):97–116. doi: 10.1080/10941660500500808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N.Y., Tjosvold D. Guanxi and leader member relationships between American managers and Chinese employees: Open-minded dialogue as mediator. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. 2007;24(2):171–189. doi: 10.1007/s10490-006-9029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chinomona R., Sandada M. Customer satisfaction, trust and loyalty as predictors of customer intention to re-purchase South African retailing industry. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 2013;4(14):437–446. doi: 10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n14p437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chon M.-G. Government public relations when trouble hits: Exploring political dispositions, situational variables, and government–public relationships to predict communicative action of publics. Asian Journal of Communication. 2019;29(5):424–440. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2019.1649438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chon M.G., Park H. Predicting public support for government actions in a public health crisis: Testing fear, organization-public relationship, and behavioral intention in the framework of the situational theory of problem solving. Health Communication. 2021;36(4):476–486. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2019.1700439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T., Holladay S.J. Comparing apology to equivalent crisis response strategies: Clarifying apology’s role and value in crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 2008;34(3):252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip S.M., Center A.H., Broom G.M. Prentice Hall; 1994. Effective public relations. [Google Scholar]

- Easton D. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science. 1975;5(4):435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgas J.P. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM) Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(1):39–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgas J.P. Affect and cognition. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(2):94–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunig J.E., Huang Y.-H. In: Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations. Ledingham J.A., Bruning S.D., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum; 2000. From organizational effectiveness to relationship indicators: Antecedents of relationships, public relations strategies, and relationship outcomes; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Walker L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research. 2001;4(1):60–75. doi: 10.1177/109467050141006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison V.S., Xiao A., Ott H.K., Bortree D. Calling all volunteers: The role of stewardship and involvement in volunteer-organization relationships. Public Relations Review. 2017;43(4):872–881. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herr P.M., Kardes F.R., Kim J. Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information of persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer Research. 1991;17(4):454–462. doi: 10.1086/208570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Høgevold N., Svensson G., Otero-Neira C. Trust and commitment as mediators between economic and non-economic satisfaction in business relationships: A sales perspective. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing. 2020;35(11):1685–1700. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-03-2019-0118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hon, L.C., & Grunig, J.E. (1999). Guidelines for measuring relationships in public relations. Gainesville, FL: Institute for public relations.

- Hong H. Government websites and social media’s influence on government–public relationships. Public Relations Review. 2013;39(4):346–356. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H., Park H., Lee Y., Park J. Public segmentation and government–public relationship building: A cluster analysis of publics in the United States and 19 European countries. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2012;24(1):37–68. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2012.626135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. (2020). Hong Kong public opinion research report. 〈https://www.pori.hk/research-reports〉.

- Hong S.Y., Yang S.U. Effects of reputation, relational satisfaction, and customer–company identification on positive word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2009;21(4):381–403. doi: 10.1080/10627260902966433. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.Y., Yang S.-U. Public engagement in supportive communication behaviors toward an organization: Effects of relational satisfaction and organizational reputation in public relations management. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2011;23(2):191–217. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2011.555646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.H. OPRA: A cross-cultural, multiple-item scale for measuring organization-public relationships. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2001;13(1):61–90. doi: 10.1207/S1532754XJPRR1301_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.H. Trust and relational commitment in corporate crises: The effects of crisis communicative strategy and form of crisis response. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2008;20(3):297–327. doi: 10.1080/10627260801962830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.H.C., Lu Y., Choy C.H.Y., Kao L., Chang Y. How responsiveness works in mainland China: Effects on institutional trust and political participation. Public Relations Review. 2020;46(1) [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. In search of a causal model of the organization–public relationship in public relations. Social Behavior and Personality. 2018;46(11):1761–1770. doi: 10.2224/sbp.7022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J., Horta H., Postiglione G.A. Living in uncertainty: The COVID-19 pandemic and higher education in Hong Kong. Studies in Higher Education. 2021;46(1):107–120. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1859685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D.A., Kaniskan B., McCoach D.B. The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research. 2015;44(3):486–507. doi: 10.1177/0049124114543236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kent M.L., Taylor M., White W.J. The relationship between Web site design and organizational responsiveness to stakeholders. Public Relations Review. 2003;29(1):63–77. doi: 10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00194-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. Toward an effective government–public relationship: Organization–public relationship based on a synthetic approach to public segmentation. Public Relations Review. 2015;41(4):456–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai V.T., Hagoort P., Casasanto D. Affective primacy vs. cognitive primacy: Dissolving the debate. Frontiers in Psychology. 2012;3(243) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist. 1991;46(8):819–834. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R.S. In: Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. Scherer K.R., Schorr A., Johnstone T., editors. Oxford University Press; 2001. Relational meaning and discrete emotions; pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S., Palayew A., Billari F.C., Binagwaho A., Kimball S.…El-Mohandes A. COVID-SCORE: A global survey to assess public perceptions of government responses to COVID-19 (COVID-SCORE-10. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledingham J.A., Bruning S.D. Routledge; 2000. Public relations as relationship management: A relational approach to the study and practice of public relations. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Huang Y. Does relationship matter during a health crisis: Examining the role of local government-public relationship in the public acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines. Health Communication. 2021 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2021.1993586. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Ni L. Relationship matters: How government organization–public relationship impacts disaster recovery outcomes among multiethnic communities. Public Relations Review. 2021;47(3) doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2021.102047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Huang Y.-H.C. Getting emotional: An emotion-cognition dual-factor model of crisis communication. Public Relations Review. 2018;44(1):98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer R.C., Davis J.H. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1999;84(1):123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer R.C., Davis J.H., Schoorman F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review. 1995;20(3):709–734. doi: 10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister S.M. Toward a dialogic theory of fundraising. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 2013;37(4):262–277. doi: 10.1080/10668920903527043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Muralidharan S. Understanding social media peer communication and organization-public relationships: Evidence from China and the United States. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2017;94(1):81–101. doi: 10.1177/1077699016674187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Tsai W.-H.S. Perceptual, attitudinal, and behavioral outcomes of organization–public engagement on corporate social networking sites. Journal of Public Relations Research. 2014;26(5):417–435. doi: 10.1080/1062726X.2014.951047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Men L.R., Yang A., Song B., Kiousis S. Examining the impact of public engagement and presidential leadership communication on social media in China: Implications for government–public relationship cultivation. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2018;12(3):252–268. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2018.1445090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R.M., Hunt S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing. 1994;58(3):20–38. doi: 10.1177/002224299405800302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K.B. A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing. 1991;55(1):10–25. doi: 10.1177/002224299105500102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rim H., Song D. The ability of corporate blog communication to enhance CSR effectiveness: The role of prior company reputation and blog responsiveness. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2013;7(3):165–185. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2012.738743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker R.E., Lomax R.G. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. 4th ed. Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N. In: Handbook of theories of social psychology. Van Lange P.A.M., Kruglanski A.W., Higgins E.T., editors. SAGE; 2011. Feelings-as-information theory; pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Seeger M.W., Ulmer R.R. Vol. 30. 2002. A post-crisis discourse of renewal: The cases of malden mills and cole hardwoods; pp. 126–142. (Journal of Applied Communication Research). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Setbon M., Raude J. Factors in vaccination intention against the pandemic influenza A/H1N1. European Journal of Public Health. 2010;20(5):490–494. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streefland P.H. Public doubts about vaccination safety and resistance against vaccination. Health Policy. 2001;55(3):159–172. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(00)00132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromer-Galley J. On-line interaction and why candidates avoid it. Journal of Communication. 2000;50(4):111–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02865.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su V.Y.-F., Yen Y.-F., Yang K.-Y., Su W.-J., Chou K.-T., Chen Y.-M., Perng D.-W. Masks and medical care: Two keys to Taiwan’s success in preventing COVID-19 spread. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;38 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis H.C. Individualism‐collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(6):907–924. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Exploring the linkages among transparent communication, relational satisfaction and trust, and information sharing on social media in problematic situations. El Profesional de La Información. 2020;29(3) doi: 10.3145/epi.2020.may.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ki E.-J., Kim Y. Exploring the perceptual and behavioral outcomes of public engagement on mobile phones and social media. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2017;11(2):133–147. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2017.1280497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.-X. (2013). Institutional trust in East Asia (Working Paper Series No. 92). Global Barometer. 〈http://www.globalbarometers.org/publications/53ee5c22c8231a80f7205364a37ec9c3.pdf〉.

- Ward J.K., Alleaume C., Peretti-Watel P., Peretti-Watel P., Seror V., Cortaredona S.…Ward J. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Social Science & Medicine. 2020;265 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber P., Steinmetz H., Kabst R. Trust in politicians and satisfaction with government–a reciprocal causation approach for European countries. Journal of Civil Society. 2017;13(4):392–405. doi: 10.1080/17448689.2017.1385160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Welch E.W., Hinnant C.C., Moon M.J. Linking citizen satisfaction with e-government and trust in government. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2004;15(3):371–391. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mui021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, C., & Schermelleh-Engel, K. (2010). Introduction to structural equation modeling with LISREL. Goethe University, Frankfurt.

- Xie Y., Qiao R., Shao G., Chen H. Research on Chinese social media users’ communication behaviors during public emergency events. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34(3):740–754. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Wu J., Cao L. COVID-19 pandemic in China: Context, experience and lessons. Health Policy and Technology. 2020;9(4):639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-U. Effects of government dialogic competency: The MERS outbreak and implications for public health crises and political legitimacy. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2018;95(4):1011–1032. doi: 10.1177/1077699017750360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.U., Grunig J.E. Decomposing organisational reputation: The effects of organisation–public relationship outcomes on cognitive representations of organisations and evaluations of organisational performance. Journal of Communication Management. 2005;9(4):305–325. doi: 10.1108/13632540510621623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.