Abstract

Chia (Salvia hispanica) is a functional food crop for humans. Although its seeds contain high omega-3 fatty acids, the seed yield of chia is still low. Genomic resources available for this plant are limited. We report the first high-quality chromosome-level genome sequence of chia. The assembled genome size was 347.6 Mb and covered 98.1% of the estimated genome size. A total of 31 069 protein-coding genes were predicted. The absence of recent whole-genome duplication and the relatively low intensity of transposable element expansion in chia compared to its sister species contribute to its small genome size. Transcriptome sequencing and gene duplication analysis reveal that the expansion of the fab2 gene family is likely to be related to the high content of omega-3 in seeds. The white seed coat color is determined by a single locus on chromosome 4. This study provides novel insights into the evolution of Salvia species and high omega-3 content, as well as valuable genomic resources for genetic improvement of important commercial traits of chia and its related species.

Key words: genome, fatty acid, seed coat color, Salvia species, chia

This study reports the first high-quality chromosome-level genome sequence of chia and the analysis of the expression patterns of genes related to fatty acid yield. The seed coat color (scc) was mapped to a single locus. These genomic resources provide insights into the evolution of the chia genome and the high content of omega-3 fatty acids in chia seeds.

Introduction

Chia (Salvia hispanica) is a flowering plant in the mint family (Figure 1A), Lamiaceae, that is native to Central America (Cahill, 2003). Chia seeds have been used by the Mayans and Aztecs as a food source since 3500 BC (Muñoz et al., 2013). Chia seeds have been regarded as a pseudocereal and are cultivated commercially in many countries, including Bolivia, Mexico, Argentina, Australia, the United States, and China (Yue et al., 2022). Chia seeds have an oil content of up to 40% (Ali et al., 2012). The proportion of unsaturated fatty acids in chia seed oil is the highest among all known oil seed plants. Omega-3 fatty acids, mainly α-linolenic acid, account for up to 60% of the total oil content, followed by ω-6 linoleic acid at 20% (Ali et al., 2012). Other than valuable unsaturated fatty acids, chia seeds also contain notably high amounts of important nutritional components including soluble and insoluble fibers (18%–30%), proteins (15%–25%), vitamins, minerals, and natural antioxidants (Ixtaina et al., 2008). For these reasons, chia is considered to be a functional food for human nutrition (Muñoz et al., 2013). In addition, chia seeds have also been shown to increase the satiety index and prevent cardiovascular diseases, inflammatory and nervous system disorders, and diabetes in humans (Weber et al., 1991). Therefore, chia seeds have great potential uses in the health food industry and as animal feed and pharmaceuticals. As chia can grow in a wide range of conditions, including arid environments, it has been considered as an alternative crop for the field crop industry (Peiretti and Gai, 2009).

Figure 1.

Hi-C scaffolding and genomic features of chia.

(A) A photo of chia (Salvia hispanica).

(B) Construction of pseudochromosomes based on chromosome conformation captured by Hi-C sequencing. Six pseudochromosomes corresponding to haploid chromosomes are highlighted by blue boxes, and contigs are highlighted by green boxes.

(C–G) Circos diagram showing genomic features and whole-genome duplication (WGD) of chia, including ideogram and length of individual chromosomes (A), distribution pattern of GC content (B), repetitive sequences (C), DNA long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) (D), gene density (E), and SNP density (F) estimated in 500-kb windows throughout individual chromosomes and conserved syntenic blocks between pairs of homologous chromosomes, indicating ancient WGD (G). (D) Genomic synteny between six chromosomes of chia and seven ancestral eudicot karyotypes (AEK).

Artificial selection has contributed to increases in both seed size and oil yield compared to the wild type (Peláez et al., 2019). However, the seed yield of chia remains very low (300–1700 kg/ha) (Yue et al., 2022). Thus, it would be beneficial to increase its seed yield using novel technologies. Understanding the genetic basis of seed-related commercial traits such as oil yield, seed size, and coat color is an essential step toward molecular breeding (Xu et al., 2012) to accelerate genetic improvement. Chia is a biannually flowering plant, supplying a useful system for genetic modification studies (Cahill, 2003). However, to date, only a few chia genomic resources (i.e., a few SSRs and transcriptomes) have been available (Peláez et al., 2019; Wimberley et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2022). The lack of genomic resources limits genetic studies of how genetics are linked to phenotypes of important traits (e.g., seed yield and color, oil contents, and composition) in this species.

Here, we sequenced, assembled, and annotated the genome of chia to facilitate the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying its compact genome size and high seed omega-3 contents, as well as to generate genomic resources for the genetic improvement of economically important traits.

Results

Chromosome-level reference genome of chia

A total of 478 contigs were constructed based on PacBio reads with an overall coverage of ∼170×, a total length of 347.6 Mb and an N50 contig length of 3.8 Mb (Supplemental Table 1). The assembled sequences showed a GC content of 36.6% and covered 98.1% of the estimated genome size of 354.5 Mb. Hi-C scaffolding anchored 99.0% of the assembled sequences to six pseudochromosomes (Supplemental Table 2) corresponding to six haploid chromosomes (Palma-Rojas et al., 2017), and the length of the longest chromosome was 68.3 Mb (Figure 1B). We observed evidence of a chromosomal interaction hotspot between the telomeric regions of chr1 and chr2 in the Hi-C data (Figure 1B). Completeness of the assembly was first assessed by mapping to the BUSCO database. We found that 98.7% of the core genes in the BUSCO database were complete, and only 0.5% were missing in the assembled genome sequences (Supplemental Table 3). This BUSCO value is distinctly higher than that of other Salvia genome sequences, including those of Salvia splendens (BUSCO, 92%) (Jia et al., 2021) and Salvia miltiorrhiza (BUSCO, 92.5%) (Song et al., 2020). The long terminal repeat (LTR) assembly index (LAI) value that was used to measure the completeness of repetitive sequences in the genome assembly was 17.76 (SD, 4.53), higher than those of reported model species (Ou et al., 2018). Approximately 98.9% of the mRNA sequencing reads and 98.1% of the Illumina resequencing reads could be mapped to the genome sequences. All these data suggest that this genome assembly is of high quality.

Annotation of the chia genome

Approximately 45.7% of the genome sequences were annotated as repetitive sequences (Supplemental Table 4). Long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs) accounted for 15.5% (53.8 Mb) of the whole genome, within which Gypsy and Copia were the top two superfamilies and accounted for 9.6% (33.3 Mb) and 5.8% (20.2 Mb) of the genome sequences, respectively. The genome-wide distribution pattern of repetitive sequences was positively correlated with that of GC content (Pearson’s R = 0.473, P < 0.0001) but negatively correlated with that of gene density (Pearson’s R = –0.824, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1C). Therefore, historical expansion of TE elements has probably shaped the genome architecture. A total of 2089 intact LTR-RTs were detected throughout the whole genome. Most of the intact LTR-RTs (89.6%) were estimated to have been inserted into the genome within one million years before the present, and the number of young intact LTR-RTs was observed to have markedly increased recently, suggesting recent transposon expansion in the chia genome (Supplemental Figure 1). By comparison, LTR-RTs accounted for ∼44% (261.9 Mb) of the whole-genome sequences in its sister species, red sage (S. miltiorrhiza), with a genome size of ∼585 Mb and 65% repetitive sequences (Song et al., 2020). When LTR-RT sequences were excluded, there was no evident difference in genome size between the two species. In particular, we observed a much more striking burst of LTR-RTs within one million years before the present in red sage than in chia (Supplemental Figure 1). These data suggest that the dynamics of LTR-RTs have played critical roles in genome size variation in this taxa group, as observed in some other plants (Tenaillon et al., 2011; Lee and Kim, 2014).

Based on evidence of both transcripts and protein-coding sequences, 31 069 protein-coding genes were predicted, 94.9% of which showed an annotation edit distance value of < 0.5 (Supplemental Figure 2) and 74.7% (23 193) of which had hits to known proteins or domains in the Pfam protein family database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). The number of predicted genes is comparable to that of S. miltiorrhiza, which ranges from 30 478 to 33 760 for different assemblies (Xu et al., 2016; Song et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2021). The average gene length was ∼3.1 kb, showing little difference from that of S. miltiorrhiza (∼2.8 kb) (Ma et al., 2021). Over 99.5% of the annotated genes were assembled into six haploid pseudochromosomes, indicating that this genome assembly represents a nearly complete protein-coding genome.

Genome evolution and speciation

To study chromosome rearrangements within and among Salvia species, we first reconstructed the ancestral eudicot karyotype (AEK) and observed large conserved AEK blocks representing seven eudicot protochromosomes (Murat et al., 2017) throughout the six haploid chromosomes of the chia genome, although frequent interchromosomal rearrangements have occurred (Figure 1D). Such conserved synteny between the chia genome and the AEK suggests an absence of frequent large-scale whole-genome rearrangements following whole-genome duplication (WGD) events (Inoue et al., 2015). In chromosomal homology analysis, we found evidence of short chromosomal fragment duplications rather than large-scale chromosomal duplications throughout the whole genome, suggesting no recent WGD events in the chia genome (Supplemental Figure 3).

We then reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships and estimated the divergence times of eight representative eudicot species based on one-to-one homologous genes. The time of divergence between chia and scarlet sage, one of its sister species that also originated in South America, was estimated to be ∼9.6 Mya, whereas the divergence between chia and its Eurasian sister species, red sage, was ∼24.3 Mya (Figure 2A). The time of divergence between chia and red sage is comparable to that of Old and New World sister species such as sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and maize (Zea mays) with a divergence time of ∼26 Mya (Paterson et al., 2009) and various Old and New World Allium species (∼25–50 Mya) (Dubouzet and Shinoda, 1999). We observed a high level of conserved genomic synteny between chia and the tetraploid scarlet sage, which has experienced a recent WGD event and evolved 11 haploid chromosomes (Figure 2B and 2C). Compared with the genome of scarlet sage, extensive chromosome fusions and two major chromosome splits have occurred in the ancestral genomes of chia, corresponding to chr3/chr4 and chr15/chr16 of scarlet sage, with the haploid number of chromosomes degenerating from 11 to 6 (Figure 2C). However, we did not detect an evident genomic synteny between chia and red sage (Figure 2B and Supplemental Figure 4). This may be due to rapid chromosome rearrangements of red sage after a recent WGD event (Song et al., 2020) or to misassembly of the red sage scaffolds.

Figure 2.

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) and diversification of Salvia species.

(A) A phylogeny showing the divergence times of representative eudicots. A. thaliana, Arabidopsis; V. vinifera, grapevine; S. lycopersicum, tomato; S. indicum, sesame; S. barbata, barbed skullcap; S. miltiorrhiza, red sage; S. splendens, scarlet sage; S. hispanica, chia. The estimated point of divergence between adjacent lineages is shown at node sites, and the WGD events in the sister species S. splendens and S. hispanica are indicated with blue bars.

(B) Genome synteny between S. hispanica and S. miltiorrhiza and between S. hispanica and S. splendens. Conserved syntenic blocks between S. hispanica and S. splendens are highlighted with six different colors corresponding to the chromosomes of S. hispanica.

(C) Genome synteny between S. hispanica and S. miltiorrhiza revealed by dot plot.

(D) Distribution of synonymous substitution rate (Ks) of pairwise homologous genes from syntenic blocks between S. hispanica and S. splendens (diversification event) and from syntenic blocks between chromosomes within S. hispanica and S. splendens (WGD events).

Ancient polyploidizations are common in eudicots and act as an important evolutionary force driving speciation (Wood et al., 2009). We estimated the distribution of the synonymous substitution rate (Ks) of pairwise homologous genes between syntenic blocks to study the genome evolutionary trajectory of Salvia species and to examine the connection between polyploidy and speciation in Salvia species. We identified 4120 pairs of homologous genes from conserved syntenic blocks in the chia genome (Figure 1C). The distribution of Ks values showed only one peak at ∼0.29 (Figure 2D). By comparison, the distribution of Ks values estimated based on 2751 pairs of homologous genes from conserved syntenic blocks within the haploid genome in scarlet sage showed a peak at ∼0.28, which coincided with the Ks peak of chia (Figure 2D). These data suggest that both species shared the same WGD, which occurred in their common ancestor. We then estimated the Ks values of 4969 homologous genes between two haploid genomes of scarlet sage and identified a peak at ∼0.08 (Figure 2D). Interestingly, the distribution of Ks values estimated based on 5001 pairwise homologous genes from conserved syntenic blocks of haploid genomes between chia and scarlet sage also revealed a peak at ∼0.08 (Figure 2D). The coincidence of the divergence time between chia and scarlet sage with the time of the recent WGD event in scarlet sage (Jia et al., 2021) suggests that recent WGD plays important roles in the diversification of closely related species within Salvia.

Fatty acid synthesis genes and their expression

Assignment of gene families showed that chia shared 77.9%, 83.9%, and 85.4% of gene families with Arabidopsis, sesame, and red sage, respectively (Figure 3A). We then compared the genes related to fatty acid synthesis between chia and red sage (Song et al., 2020) identified by mapping to the Arabidopsis acyl-lipid metabolism database and found 1011 and 869 genes in the two species, respectively. Gene ontology enrichment analysis revealed that genes involved in lipid trafficking, mitochondrial lipopolysaccharide synthesis, and fatty acid synthesis were much more abundant in the chia genome than in the red sage genome (Figure 3B). We next examined the expression pattern of these genes in different organs and in seeds at different developmental stages by transcriptome sequencing (Supplemental Table 5). We identified 38 genes that showed differential expression (fold change >2) between each of the four organs, roots, stems, leaves, and flowers, and at least one of the four seed samples collected separately at 8, 16, 24, and 32 days post flowering (dpf) (Figure 3C and Supplemental Table 6). Among these genes, oleosin H1 (SHI_00022939 and SHI_00019731), oleosin L (SHI_00018226), non-specific lipid-transfer protein 2 (ltp2) (SHI_00011041), peroxide reductase (SHI_00021660), and 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase a (11β-hsda) (SHI_00003731 and SHI_00024774) showed particularly high expression during seed ripening (Figure 3C and Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 3.

Gene ontology and expression of fatty acid synthesis genes in chia.

(A) Venn diagrams showing the number of shared and unique gene families among A. thaliana (Arabidopsis), S. indicum (sesame), S. splendens (scarlet sage), and S. hispanica (chia).

(B) Comparison of the richness in fatty acid synthesis genes between chia (S. hispanica) and its sister species red sage (S. miltiorrhiza) based on gene ontology enrichment analysis.

(C) Heatmap showing the relative expression levels of 38 fatty acid synthesis genes in roots, stems, leaves, and flowers of four-month-old plants and in seed samples at 8, 16, 24, and 32 days post flowering (dpf) of chia.

Chia seeds are reported to have the highest content of unsaturated fatty acids, including linoleic acid and linolenic acid, which are valuable to human health (Peiretti and Gai, 2009; Šilc et al., 2020). Fatty acid desaturase genes (FADs) play critical roles in the biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (Xue et al., 2018). We compared the number of FADs in the genomes of representative oilseed plants and also in sister species of chia, including S. miltiorrhiza and S. splendens. Interestingly, we identified 16 copies of fab2 (stearoyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] 9-desaturase 7) in the chia genome, many more than in the genomes of other analyzed oilseed plants, including sunflower (4), sesame (7), canola (7), cacao (8), and flax (4) (Supplemental Table 7), suggesting that the fab2 gene family has expanded in the chia genome. fab2 is a key gene in the pathway of plant unsaturated fatty acid synthesis (Kachroo et al., 2007). We further characterized fab2 genes to infer how these genes had evolved in the Salvia species. In the chia genome, these 16 fab2 genes were distributed on four chromosomes, and the genomic organization was highly conserved among the three studied Salvia species, except for evident gene duplications in the form of tandem repeats on chr2 of the chia genome (Figure 4A and Supplemental Figure 5). Transcriptome sequencing revealed that three fab2 genes (SHI_00001369, SHI_00006679, and SHI_00024106) showed higher expression in seed samples, whereas three other genes (SHI_00009060, SHI_00017522, and SHI_00031066) showed higher expression in roots, stems, leaves, and flowers (Figure 4B and Supplemental Table 8). Most of these fab2 genes (12 out of 16) showed considerable expression in the flower (Figure 4B and Supplemental Table 8). However, other than fab2, we did not find evidence of gene family expansion for the other FADs.

Figure 4.

Duplication and expression patterns of fab2 genes in chia.

(A) Comparison of the distribution and duplication patterns of 16 fab2 genes among chia, red sage, and scarlet sage, where inferred duplications and translocations are indicated with red arrows.

(B) Heatmap showing the relative expression levels of 16 fab2 genes in roots, stems, leaves, and flowers of four-month-old plants and in seed samples at 8, 16, 24, and 32 days post flowering (dpf) of chia.

Mapping the white seed coat color

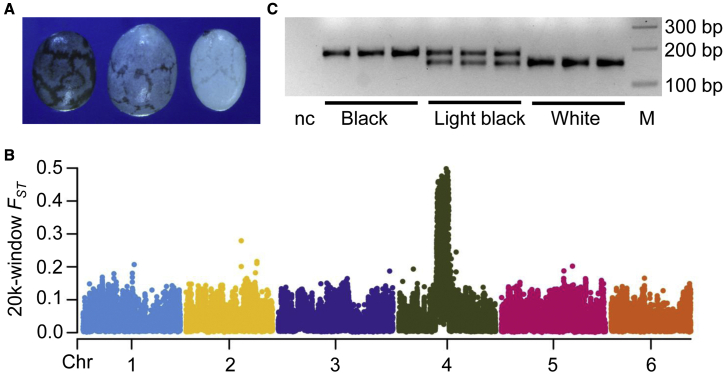

The white seed coat color (Figure 5A) of chia was reported to be controlled by a single recessive locus (scc) (Cahill and Provance, 2002). We observed that all seeds from the F1 hybrid individual from a cross of two P0 plants had black seed coats. Among the 14 F2 plants from F2 seeds, 11 F2 individuals generated black seeds, and 3 produced white seeds. The ratio of F2 plants producing black (11) to white seeds (3) did not deviate from 3:1 (x2 = 0.095, df = 1, p = 0.758). However, the genetic basis and candidate gene underlying this trait were still unclear. To uncover the genetic locus responsible for this trait, we separately sequenced a white (mutant) and a black (wild-type) pool of chia seedlings and genotyped 6 459 503 SNPs. FST scans based on both individual SNPs and a 10-kb sliding window consistently identified a major locus located on chr4 with a length of ∼7 Mb (chr4: 22.5–29.5 Mb) (Figure 5B and Supplemental Figure 6). We discovered InDels in this locus and developed PCR assays. We screened one InDel marker (chr4: 25601974) that could accurately discriminate between seed coat colors as tested in a random population consisting of 30 white and 90 black chias. The white-seeded chias were homozygous (scc/scc), whereas the dark and light black-seeded chias were homozygous for the alternative allele (SCC/SCC) and heterozygous (SCC/scc), respectively (Figure 5C). To identify the candidate genes responsible for the white seed coat color, we analyzed the transcriptomes of white and black seeds at harvest time from a previous study (Peláez et al., 2019) (Supplemental Table 5). Eight out of 217 predicted protein-coding genes within the scc locus were differentially expressed (fold change >2) between black and white chia and were upregulated in black-seeded chia (Supplemental Table 9). These genes included beta-glucosidase 44 (bglu44), histone deacetylase 6 (hdac6), phospholipid-transporting ATPase 1 (ala1), major facilitator superfamily protein (mfs), tubulin beta-5 chain (tubb5), receptor-like protein kinase (rlks), and two uncharacterized protein-coding genes.

Figure 5.

The white seed coat color of chia is determined by a single locus (scc).

(A) The phenotypes of chia seed coat color: black (wild type), light black, and white (mutant).

(B) Genome scan of FST based on a 10-kb window size identifies a single locus on chr4 responsible for white seed coat color.

(C) Genotyping of seeds with black, light black, and white coats using an InDel marker located in the scc locus.

Discussion

High-quality genome sequences and annotations build a solid basis for various genetic studies, such as dissecting the genomic architecture of traits of interest, comparative genomics, and evolutionary studies (Varshney et al., 2014). Here, we constructed the first genome assembly of chia, a popular horticultural oilseed plant and functional food crop. This genome assembly is of high completeness in protein-coding genes and repetitive sequences and high continuity in contigs and scaffolds, providing excellent resources for a diverse range of genetic studies in chia and its related species. In comparison to the other Salvia species, e.g., scarlet sage and red sage, chia has a much smaller genome size. Red sage experienced a very recent WGD event (Song et al., 2020), whereas scarlet sage experienced one more WGD event than both chia and red sage (Jia et al., 2021). The most recent WGD for scarlet sage is species specific and probably occurred at the time of divergence from chia at ∼10 MYA, as revealed in this study. The older WGD of scarlet sage was lineage specific and shared with chia; it occurred at ∼50 MYA (Jia et al., 2021). WGD can lead to the proliferation of repetitive elements, expansion of introns, and retention of duplicated genes, subsequently driving genome size expansion (Schnable et al., 2009). Consistently, we found that the content of repetitive sequences and the average length of intron sequences per gene increased by 24% and 41% and by 17% and 15% in the genomes of red sage and scarlet sage (Song et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2021), respectively, relative to that of chia. This is also observed in sesame, which also belongs to Lamiales and shows a pattern of WGD very similar to that of chia; its genome size has decreased to ∼280 Mb (Wang et al., 2014). Above all, the absence of a recent WGD is a main reason for the smaller genome size of chia, as observed in a large number of plants (Michael, 2014).

Chia is a promising oilseed crop, with the highest content of omega-3 fatty acids (Ali et al., 2012). Therefore, understanding the genomic basis of synthesis and accumulation of unsaturated fatty acids is crucial for the genetic improvement of this crop to obtain a higher yield. After comparing all annotated fatty acid synthesis genes with studies in other oil crops, we found a number of genes, e.g., oleosin genes and ltp2, that were consistently revealed to be associated with fatty acid synthesis and accumulation in seeds. In sesame (Chen et al., 1998), oilseed rape (Hills et al., 1993), maize (Lee et al., 1991), and sunflower seeds (Thoyts et al., 1995), oleosin genes are necessary for stabilizing oil bodies and facilitating oil accumulation. Therefore, the extremely high expression of oleosin genes in chia highlights their roles in oil accumulation. Lipid-transfer proteins are also known to be upregulated in high-oil-content sesames (Wang et al., 2019) and related to seed quality in rice (Wang et al., 2015) and oilseed rape (Liu et al., 2014). Here, we found that the lipid-transfer protein gene ltp2 was highly expressed in developing seeds, addressing its important role in the regulation of seed quality in terms of oil synthesis. Almost all of these genes were expressed from ∼16 dpf to seed ripening, suggesting that they are more involved in oil synthesis and accumulation than in the basal function of maintaining seed development. Interestingly, we identified 16 fab2 genes in the chia genome, more than those identified in other oilseed crops. Within the 16 fab2 genes, 11 were from a tandem duplication on chr2. In the transcriptomes of examined samples, over half of these fab2 genes showed considerable expression in different kinds of organs including the root, stem, leaf, seed, and particularly flower. fab2 genes mediate the conversion of stearic acid (18:0) to oleic acid (18:1), which is a key step in the regulation of unsaturated fatty acid levels in cells (Kachroo et al., 2004). In other plant and algae species, overexpression of fab2 genes led to an increase in omega-3 contents (Lightner et al., 1994; Hwangbo et al., 2014). Therefore, the expansion of fab2 genes is likely to be associated with the extremely high content of omega-3 fatty acids in chia seeds. Taken together, these data provide valuable clues for understanding the mechanism of high content of omega-3 fatty acids in chia seeds. The identified genes are valuable targets for the genetic improvement of oil yield in the species.

In some oilseed crops, such as sesame (Wei et al., 2015), oilseed rape (Yan et al., 2009), and peanut (Kuang et al., 2017), the seed coat color trait is a current topic of interest because of its positive correlation with oil content. However, in chia, seed coat color is reported not to be related to oil content (Ayerza, 2010), suggesting different genetic mechanisms. Here, we observed that the ratio of black to white seed coat color was 3:1 in F2 plants, confirming that black/white coat color is determined by a single gene (Cahill and Provance, 2002). We mapped the scc locus to a large genomic region on chr4 using pooled sequencing, limiting further dissection of the candidate gene and identification of the causal mutation. Nevertheless, we developed an InDel marker for use in a PCR assay and verified that it was strictly linked with seed coat color in a tested population. This marker would be useful for selective breeding of chia. We searched for the potential functions of the candidate genes by literature mining and found that beta-glucosidase genes showed differential expression between black- and white-coated seeds of sesame (Wang et al., 2020), implying that bglu44 is a candidate gene for the white seed coat color of chia. However, because the seeds were sampled at the post-harvest stage, the transcriptome data were not necessarily able to capture the candidate gene, which may determine seed pigmentation patterns at an earlier stage. For this reason, we looked into the potential functions of the remaining genes within the scc locus and found nine other genes that were revealed to be involved in seed coat pigmentation. These genes included three cytochrome P450 and two chalcone synthase genes (Supplemental Table 10), which were revealed to be involved in seed coat coloration of sesame and Brassica species (Liu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2021). These genes affect seed coat coloration by regulating the production and accumulation of flavonoids and/or proanthocyanidin in the seed coat (Debeaujon et al., 2001; Toda et al., 2002). We also discovered four plasma membrane H+-ATPase genes (aha5, aha6, aha8, and aha9) located in the scc locus. Previous studies in Arabidopsis showed that a paralog of these genes, aha10, was involved in the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway and that disruptions of this gene resulted in a reduction in proanthocyanidin and light-colored seeds (Baxter et al., 2005). However, as the scc locus is very long and contains more than 200 protein-coding genes, it is a major challenge to accurately identify the candidate genes and causal mutation. Future studies employing a population with a large effective size would help to fine map the candidate gene for white coat color.

In summary, we sequenced, assembled, and annotated a high-quality genome sequence of chia. The genome of chia is very compact, with a length of 347.6 Mb. Absence of recent WGD and a low intensity of transposable element expansion are the main reasons for its compact genome. The recent expansion of fab2 genes is likely to explain the extremely high content of omega-3 fatty acids in chia seeds. The white seed coat color is determined by a single locus on chromosome 4. A DNA marker was developed to differentiate the black from the white color of chia seeds. Our study provides novel insights into the compact genome size of chia and the mechanism underlying the high omega-3 content of chia seeds. This study also provides valuable genomic resources for the genetic improvement of economically important traits in chia.

Materials and methods

Genome sequencing and assembly

An individual black cultivar of chia originating from Australia (Yue et al., 2022) was used for genome sequencing with both PacBio single-molecule real-time sequencing and Hi-C technologies. Genomic DNA was isolated from leaves using a standard CTAB protocol. A 20-kb library was constructed and sequenced using the PacBio Sequel II system (Pacific Biosciences, USA), and 62 Gb of raw reads with an N50 of 17.4 kb (∼170× genome coverage) were obtained. A 500-bp insert library was constructed for Illumina sequencing with ∼120× coverage and used to estimate genome size with BBmap (Bushnell et al., 2017).

Two independent Hi-C libraries were constructed according to a previous method with some modifications (Belaghzal et al., 2017). In brief, leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and then fixed with 1% formaldehyde to crosslink DNA–DNA interactions that were bridged by proteins. Cross-linked DNA was digested with the restriction enzyme DpnII (R0543S, NEB). Sticky ends were marked with biotin-14-dATP and then in situ proximally ligated. The products were further cleaned, enriched, and sheared into fragments with a peak of 500 bp using a Covaris M220 ultrasonicator. Hi-C libraries were constructed using the TruSeq DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, USA). The libraries were sequenced using the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, USA) for 150-bp paired-end reads, and ∼60 Gb of raw reads were obtained.

PacBio long reads were cleaned and assembled using the Flye v2.82b assembler (Kolmogorov et al., 2019) with the following parameters (--min-overlap 10 000), followed by two rounds of polishing (-i 2). Hi-C reads were used to anchor the assembled contigs to scaffolds using Juicer (Durand et al., 2016a) and 3D-DNA pipelines (Dudchenko et al., 2017) as described in a previous study (Dudchenko et al., 2017). The scaffolds were then manually curated using Juicebox (Durand et al., 2016b) with a prior setting of six pairs of chromosomes (Palma-Rojas et al., 2017). Completeness of the genome sequences in terms of protein-coding genes was assessed with BUSCO v5.2.2 by mapping to the embryophyta_odb10 database (Simão et al., 2015). Completeness of the repetitive sequences in the assembly was evaluated using LAI (Ou et al., 2018) with the program LTR_retriever (Ou and Jiang, 2018).

Genome annotation

The assembled genome sequences were first used to build a custom repeat library using RepeatModeler (http://www.repeatmasker.org). RepeatMasker (Chen, 2004) was then used to identify repetitive sequences relying on both the Repbase database (Jurka et al., 2005) and the custom repeat library. Short tandem repeats were identified using Tandem Repeat Finder (Benson, 1999). These repetitive sequences were finally combined and reduced to produce a nonredundant repeat annotation of the genome.

Prediction of protein-coding genes was carried out using the Maker2 pipeline (Holt and Yandell, 2011). Repetitive sequences identified above were first softmasked using RepeatMasker (Chen, 2004). Evidence-based annotation of protein-coding genes was conducted based on the reduced transcript dataset assembled by Trinity (see below), and ab initio gene model prediction was performed based on the evidence of protein sequences from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (Ensembl AIR10), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) (Ensembl SL3.0), sesame (Sesamum indicum) (Ensembl S_indicum_v1.0), red sage (S. miltiorrhiza) (Song et al., 2020), and scarlet sage (S. splendens) (Jia et al., 2021). Predicted gene models were iteratively trained using SNAP (Korf, 2004) and Augustus (Stanke et al., 2006). Predicted gene models were cleaned by removing those that contained TE domains and were not supported by transcripts.

Analysis of genome evolution

For phylogenetic analysis, protein sequences of A. thaliana (Ensembl AIR10), Vitis vinifera (Ensembl 12X), S. lycopersicum (Ensembl SL3.0), S. indicum (Ensembl S_indicum_v1.0), Scutellaria barbata (Xu et al., 2020), S. miltiorrhiza (Song et al., 2020), S. splendens (Jia et al., 2021), and S. hispanica were obtained from the NCBI database and used to identify one-to-one orthologs by pairwise blast search using Ortholog-finder (Horiike et al., 2016). Gene families were identified and constructed based on the Pfam database (Bateman et al., 2004). Orthologous sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) and then polished using trimAl (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). A total of 288 conserved orthologous genes were retained and concatenated to construct a phylogenetic tree using IQ-TREE2 (Minh et al., 2020) under the amino acid substitution model (JTT + F + R4) determined by ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al., 2017). Divergence times between lineages were estimated using MCMCTree implemented in PAML (Yang, 2007). Divergence times between V. vinifera and S. lycopersicum (∼111–131 Mya) and between S. indicum and S. barbata (∼56–73 Mya) obtained from http://www.timetree.org were used to calibrate the divergence times.

Comparative genomics

To reconstruct the AEK in the genome of S. hispanica, we mapped the genome-wide protein-coding genes to the AEK database that was built based on the peach, grape, and cocoa genome sequences (Murat et al., 2017) using Reciprocal BLAST Analysis. Homologous blocks between and within species of interest were detected using the MCscan pipeline (Tang et al., 2008) based on genome-wide protein-coding genes. Protein sequences of one-to-one homologous genes (orthologs or paralogs) from homologous blocks were extracted and aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). Pairwise coding sequences were then aligned with the guidance of corresponding protein alignments. Pairwise DNA alignments were polished using trimAl (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009) and then used for the calculation of Ks using KaKs_calculator 2.0 (Wang et al., 2010).

Transcriptome sequencing and analysis

For transcriptome sequencing, RNA was first isolated from roots, stems, leaves, and flowers of three four-month-old plants using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). RNA was then pooled with an equal quantity from each sample for each type of organ and used for mRNA library construction. RNA was also isolated from developing seeds at 8, 16, 24, and 32 dpf. One hundred seeds from each time point were collected for RNA isolation using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. mRNA libraries were constructed using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, USA) and sequenced on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, USA) for 75-bp paired-end reads.

Transcriptome sequencing reads were cleaned using process_shortreads in the Stacks package (Catchen et al., 2013) with default parameters. Transcripts were first assembled from individual samples using Trinity (Grabherr et al., 2011). Transcripts were then combined, and the redundancy was reduced using BBmap in the BBTools package (Bushnell et al., 2017). These clean transcripts were used for the prediction of protein-coding genes as described below. RNA-seq reads were aligned to the reference genome using STAR (Dobin et al., 2013) with default parameters to compare the relative expression levels of genes of interest in different samples. Uniquely aligned reads were counted using HTSeq-count (Anders et al., 2015) against the annotations of predicted protein-coding genes. The relative gene expression level was measured as transcripts per million.

Analysis of genes for fatty acid metabolism

In order to identify genes related to the metabolism of fatty acids, predicted protein-coding genes were mapped to the Arabidopsis acyl-lipid metabolism database (http://aralip.plantbiology.msu.edu/pathways) using blastp with cutoff values of E-value < 1e-5 and identity >30%. Duplicated genes of interest were extracted and used as baits to search the genomes of related species with blastp (E-value < 1e-5 and identity >30%). The targeted genomic regions and their flanking sequences were extracted and then manually curated and annotated for further duplication and expression analyses. Protein sequences of duplicated genes were aligned and polished, then used for phylogenetic tree construction with IQ-TREE2 (Minh et al., 2020) as described above.

Mapping of the white seed coat color

A previous study showed that the seed color of chia is a qualitative trait that is controlled by a single locus (Cahill and Provance, 2002). To examine and confirm the Mendelian inheritance pattern of chia seed coat color, we constructed an F2 family by crossing a pure black chia with pollen from a chia with a white seed coat color in the parental generation (P0). A single F1 hybrid was planted in our laboratory to enable selfing. All seeds (F2) from the F1 hybrid were collected. A subset of 14 F2 seeds were germinated, and seedlings were planted in our laboratory for five months to collect their seeds and record seed color. Deviation of the ratio of black and white seeds of F2 plants from the expectation of 3:1 was examined using a Chi-squared test (x2). To map the genetic locus for white seed coat color (scc), 120 white-coated seeds from Mexico and Australia and 100 black-coated seeds from Mexico, Australia, Bolivia, and Peru were planted separately. In our previous study, we found little genetic differentiation among these studied populations or between black and white strains (Yue et al., 2022). Leaves were harvested from one-month-old plants and used for DNA isolation. Equal amounts of DNA from each sample of white and black seeds were separately pooled for DNA library construction with a 550-bp insert size using the Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep Kit (Illumina, USA). DNA libraries were sequenced on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, USA) for 150-bp paired-end reads, and ∼150× coverage of reads was obtained for each pool. Raw reads were cleaned using process_shortreads in the Stacks package (Catchen et al., 2013). Clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using BWA-MEM (Li and Durbin, 2009). Genetic variants were identified using PoPoolation2 (Kofler et al., 2011). Genetic mapping for seed coat color was carried out using an FST-based method as described in our previous studies (Wang et al., 2021, 2022a, 2022b). FST between white and black pools was calculated using PoPoolation2 (Kofler et al., 2011) separately for individual variants and for variants in 10-kb sliding windows with a step size of 10 kb. InDels between white and black samples were discovered using the Picard/GATK v4.0 best practices workflows (McKenna et al., 2010). InDels that showed extreme differences in allele frequency between white and black pools with suitable lengths were used to develop primers for PCR assays. PCR assays (chr4: 25601974, forward primer GTTTATTCGAACGCGCTCTT and reverse primer CCTTGAATTGGAACATCTCC) were validated in selected white- and black-coated samples with the following PCR conditions: 94°C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were examined by running 3% agarose gels.

Funding

This research was supported by Internal Funds of the Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory (5020).

Author contributions

G.H.Y. initiated, conceived, and supervised the project. L.W. designed the study. L.W., M.L., F.S., Z.S., and Z.Y. conducted the experiments. L.W. and M.L. analyzed the data. L.W., M.L., and G.H.Y. prepared the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank other lab members for technical support. We declare no conflicts of interest.

Published: April 14, 2022

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and CEMPS, CAS.

Supplemental information can be found online at Plant Communications Online.

Accession numbers

All sequencing data used in this study have been deposited at the DDBJ SRA database with accession no. PRJDB12688. The chromosome-level genome sequences of chia assembled in this study can be accessed from https://genhua.tll.org.sg/ and at the China National GeneBank DataBase under Bioproject no. CNP0002868 (Assembly ID: CNA0047366).

Supplemental information

Document S1. Supplemental Figures 1–6 and Supplemental Tables 1–10

Document S2. Article plus supplemental information

References

- Ali N.M., Yeap S.K., Ho W.Y., Beh B.K., Tan S.W., Tan S.G. The promising future of chia, Salvia hispanica L. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012;2012:171956. doi: 10.1155/2012/171956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S., Pyl P.T., Huber W. HTSeq—a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayerza R. Effects of seed color and growing locations on fatty acid content and composition of two chia (Salvia hispanica L.) genotypes. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010;87:1161–1165. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R., Finn R.D., Hollich V., Griffiths-Jones S., Khanna A., Marshall M., Moxon S., Sonnhammer E.L. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D138–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter I.R., Young J.C., Armstrong G., Foster N., Bogenschutz N., Cordova T., Peer W.A., Hazen S.P., Murphy A.S., Harper J.F. A plasma membrane H+-ATPase is required for the formation of proanthocyanidins in the seed coat endothelium of Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2005;102:2649–2654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406377102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaghzal H., Dekker J., Gibcus J.H. Hi-C 2.0: an optimized Hi-C procedure for high-resolution genome-wide mapping of chromosome conformation. Methods. 2017;123:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell B., Rood J., Singer E. BBMerge–Accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0185056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill J., Provance M. Genetics of qualitative traits in domesticated chia (Salvia hispanica L.) J. Hered. 2002;93:52–55. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill J.P. Ethnobotany of chia, Salvia hispanica L.(Lamiaceae) Econ. Bot. 2003;57:604–618. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catchen J., Hohenlohe P.A., Bassham S., Amores A., Cresko W.A. Stacks: an analysis tool set for population genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2013;22:3124–3140. doi: 10.1111/mec.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E.C., Tai S.S., Peng C.-C., Tzen J.T. Identification of three novel unique proteins in seed oil bodies of sesame. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:935–941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N. Using Repeat Masker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2004;5:4. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debeaujon I., Peeters A.J., Léon-Kloosterziel K.M., Koornneef M. The TRANSPARENT TESTA12 gene of Arabidopsis encodes a multidrug secondary transporter-like protein required for flavonoid sequestration in vacuoles of the seed coat endothelium. Plant Cell. 2001;13:853–871. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubouzet J., Shinoda K. Relationships among old and new world Alliums according to ITS DNA sequence analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1999;98:422–433. [Google Scholar]

- Dudchenko O., Batra S.S., Omer A.D., Nyquist S.K., Hoeger M., Durand N.C., Shamim M.S., Machol I., Lander E.S., Aiden A.P. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 2017;356:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand N.C., Shamim M.S., Machol I., Rao S.S., Huntley M.H., Lander E.S., Aiden E.L. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand N.C., Robinson J.T., Shamim M.S., Machol I., Mesirov J.P., Lander E.S., Aiden E.L. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabherr M.G., Haas B.J., Yassour M., Levin J.Z., Thompson D.A., Amit I., Adiconis X., Fan L., Raychowdhury R., Zeng Q. Trinity: reconstructing a full-length transcriptome without a genome from RNA-Seq data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills M.J., Watson M.D., Murphy D.J. Targeting of oleosins to the oil bodies of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) Planta. 1993;189:24–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00201339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt C., Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinf. 2011;12:491. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiike T., Minai R., Miyata D., Nakamura Y., Tateno Y. Ortholog-finder: a tool for constructing an ortholog data set. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016;8:446–457. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Shi X., Chen X., Zheng J., Zhang A., Wang H., Fu Q. Fine-mapping and identification of a candidate gene controlling seed coat color in melon (Cucumis melo L. var. chinensis Pangalo) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021;135:803–815. doi: 10.1007/s00122-021-03999-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwangbo K., Ahn J.-W., Lim J.-M., Park Y.-I., Liu J.R., Jeong W.-J. Overexpression of stearoyl-ACP desaturase enhances accumulations of oleic acid in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2014;8:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J., Sato Y., Sinclair R., Tsukamoto K., Nishida M. Rapid genome reshaping by multiple-gene loss after whole-genome duplication in teleost fish suggested by mathematical modeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2015;112:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507669112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ixtaina V.Y., Nolasco S.M., Tomas M.C. Physical properties of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008;28:286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Jia K.-H., Liu H., Zhang R.-G., Xu J., Zhou S.-S., Jiao S.-Q., Yan X.-M., Tian X.-C., Shi T.-L., Luo H. Chromosome-scale assembly and evolution of the tetraploid Salvia splendens (Lamiaceae) genome. Hortic. Res. 2021;8:177. doi: 10.1038/s41438-021-00614-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurka J., Kapitonov V.V., Pavlicek A., Klonowski P., Kohany O., Walichiewicz J. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005;110:462–467. doi: 10.1159/000084979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo A., Venugopal S.C., Lapchyk L., Falcone D., Hildebrand D., Kachroo P. Oleic acid levels regulated by glycerolipid metabolism modulate defense gene expression in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:5152–5157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401315101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachroo A., Shanklin J., Whittle E., Lapchyk L., Hildebrand D., Kachroo P. The Arabidopsis stearoyl-acyl carrier protein-desaturase family and the contribution of leaf isoforms to oleic acid synthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;63:257–271. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9086-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyaanamoorthy S., Minh B.Q., Wong T.K., Von Haeseler A., Jermiin L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Meth. 2017;14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler R., Pandey R.V., Schlötterer C. PoPoolation2: identifying differentiation between populations using sequencing of pooled DNA samples (Pool-Seq) Bioinformatics. 2011;27:3435–3436. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov M., Yuan J., Lin Y., Pevzner P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang Q., Yu Y., Attree R., Xu B. A comparative study on anthocyanin, saponin, and oil profiles of black and red seed coat peanut (Arachis hypogacea) grown in China. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017;20:S131–S140. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.-I., Kim N.-S. Transposable elements and genome size variations in plants. Genomics Inform. 2014;12:87. doi: 10.5808/GI.2014.12.3.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W., Tzen J., Kridl J., Radke S., Huang A. Maize oleosin is correctly targeted to seed oil bodies in Brassica napus transformed with the maize oleosin gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1991;88:6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightner J., Wu J., Browse J. A mutant of Arabidopsis with increased levels of stearic acid. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1443–1451. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F., Xiong X., Wu L., Fu D., Hayward A., Zeng X., Cao Y., Wu Y., Li Y., Wu G. BraLTP1, a lipid transfer protein gene involved in epicuticular wax deposition, cell proliferation and flower development in Brassica napus. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Lu Y., Yuan Y., Liu S., Guan C., Chen S., Liu Z. De novo transcriptome of Brassica juncea seed coat and identification of genes for the biosynthesis of flavonoids. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Cui G., Chen T., Ma X., Wang R., Jin B., Yang J., Kang L., Tang J., Lai C. Expansion within the CYP71D subfamily drives the heterocyclization of tanshinones synthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:685. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20959-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael T.P. Plant genome size variation: bloating and purging DNA. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2014;13:308–317. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elu005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh B.Q., Schmidt H.A., Chernomor O., Schrempf D., Woodhams M.D., Von Haeseler A., Lanfear R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:1530–1534. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz L.A., Cobos A., Diaz O., Aguilera J.M. Chia seed (Salvia hispanica): an ancient grain and a new functional food. Food Rev. Int. 2013;29:394–408. [Google Scholar]

- Murat F., Armero A., Pont C., Klopp C., Salse J. Reconstructing the genome of the most recent common ancestor of flowering plants. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:490–496. doi: 10.1038/ng.3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou S., Jiang N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou S., Chen J., Jiang N. Assessing genome assembly quality using the LTR Assembly Index (LAI) Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:e126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma-Rojas C., Gonzalez C., Carrasco B., Silva H., Silva-Robledo H. Genetic, cytological and molecular characterization of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) provenances. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2017;73:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson A.H., Bowers J.E., Bruggmann R., Dubchak I., Grimwood J., Gundlach H., Haberer G., Hellsten U., Mitros T., Poliakov A. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457:551–556. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiretti P., Gai F. Fatty acid and nutritive quality of chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seeds and plant during growth. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2009;148:267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez P., Orona-Tamayo D., Montes-Hernández S., Valverde M.E., Paredes-López O., Cibrián-Jaramillo A. Comparative transcriptome analysis of cultivated and wild seeds of Salvia hispanica (chia) Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45895-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable P.S., Ware D., Fulton R.S., Stein J.C., Wei F., Pasternak S., Liang C., Zhang J., Fulton L., Graves T.A. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šilc U., Dakskobler I., Küzmič F., Vreš B. Salvia hispanica (chia)–from nutritional additive to potential invasive species. Bot. Lett. 2020;167:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Simão F.A., Waterhouse R.M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E.V., Zdobnov E.M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z., Lin C., Xing P., Fen Y., Jin H., Zhou C., Gu Y.Q., Wang J., Li X. A high-quality reference genome sequence of Salvia miltiorrhiza provides insights into tanshinone synthesis in its red rhizomes. Plant Genome. 2020;13:e20041. doi: 10.1002/tpg2.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M., Keller O., Gunduz I., Hayes A., Waack S., Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Bowers J.E., Wang X., Ming R., Alam M., Paterson A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science. 2008;320:486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenaillon M.I., Hufford M.B., Gaut B.S., Ross-Ibarra J. Genome size and transposable element content as determined by high-throughput sequencing in maize and Zea luxurians. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011;3:219–229. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoyts P.J., Millichip M.I., Stobart A.K., Griffiths W.T., Shewry P.R., Napier J.A. Expression and in vitro targeting of a sunflower oleosin. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;29:403–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00043664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda K., Yang D., Yamanaka N., Watanabe S., Harada K., Takahashi R. A single-base deletion in soybean flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase gene is associated with gray pubescence color. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002;50:187–196. doi: 10.1023/a:1016087221334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney R.K., Terauchi R., McCouch S.R. Harvesting the promising fruits of genomics: applying genome sequencing technologies to crop breeding. Plos Biol. 2014;12:e1001883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Zhu J., Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2010;8:77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Sun F., Lee M., Yue G.-H. Whole-genome resequencing infers genomic basis of giant phenotype in Siamese fighting fish (Betta splendens) Zool. Res. 2022;43:78–80. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2021.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Dossou S.S.K., Wei X., Zhang Y., Li D., Yu J., Zhang X. Transcriptome dynamics during black and white sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seed development and identification of candidate genes associated with black pigmentation. Genes. 2020;11:1399. doi: 10.3390/genes11121399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhang Y., Li D., Dossa K., Wang M.L., Zhou R., Yu J., Zhang X. Gene expression profiles that shape high and low oil content sesames. BMC Genom. Data. 2019;20:45. doi: 10.1186/s12863-019-0747-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yu S., Tong C., Zhao Y., Liu Y., Song C., Zhang Y., Zhang X., Wang Y., Hua W. Genome sequencing of the high oil crop sesame provides insight into oil biosynthesis. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R39. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Sun F., Wan Z.Y., Yang Z., Tay Y.X., Lee M., Ye B., Wen Y., Meng Z., Fan B., et al. Transposon-induced epigenetic silencing in the X chromosome as a novel form of dmrt1 expression regulation during sex determination in the fighting fish. BMC Biol. 2022;20:5. doi: 10.1186/s12915-021-01205-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Sun F., Wan Z.Y., Ye B., Wen Y., Liu H., Yang Z., Pang H., Meng Z., Fan B., et al. Genomic basis of striking fin shapes and colors in the fighting fish. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021;38:3383–3396. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhou W., Lu Z., Ouyang Y., Yao J. A lipid transfer protein, OsLTPL36, is essential for seed development and seed quality in rice. Plant Sci. (Amsterdam, Neth. 2015;239:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C.W., Gentry H.S., Kohlhepp E.A., McCrohan P.R. The nutritional and chemical evaluation of chia seeds. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1991;26:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Liu K., Zhang Y., Feng Q., Wang L., Zhao Y., Li D., Zhao Q., Zhu X., Zhu X. Genetic discovery for oil production and quality in sesame. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8609. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberley J., Cahill J., Atamian H.S. De novo sequencing and analysis of Salvia hispanica tissue-specific transcriptome and identification of genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis. Plants. 2020;9:405. doi: 10.3390/plants9030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood T.E., Takebayashi N., Barker M.S., Mayrose I., Greenspoon P.B., Rieseberg L.H. The frequency of polyploid speciation in vascular plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:13875–13879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811575106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Song J., Luo H., Zhang Y., Li Q., Zhu Y., Xu J., Li Y., Song C., Wang B. Analysis of the genome sequence of the medicinal plant Salvia miltiorrhiza. Mol. Plant. 2016;9:949–952. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.B., Li Z.K., Thomson M.J. Molecular breeding in plants: moving into the mainstream. Mol. Breed. 2012;29:831–832. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Gao R., Pu X., Xu R., Wang J., Zheng S., Zeng Y., Chen J., He C., Song J. Comparative genome analysis of Scutellaria baicalensis and Scutellaria barbata reveals the evolution of active flavonoid biosynthesis. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2020;18:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y., Chen B., Win A.N., Fu C., Lian J., Liu X., Wang R., Zhang X., Chai Y. Omega-3 fatty acid desaturase gene family from two ω-3 sources, Salvia hispanica and Perilla frutescens: cloning, characterization and expression. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Li J., Fu F., Jin M., Chen L., Liu L. Co-location of seed oil content, seed hull content and seed coat color QTL in three different environments in Brassica napus L. Euphytica. 2009;170:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. Paml 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue G.H., Lai C.C., Lee M., Wang L., Song Z.J. Developing first microsatellites and analysing genetic diversity in six chia (Salvia hispanica L.) cultivars. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022;69:1303–1312. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Document S1. Supplemental Figures 1–6 and Supplemental Tables 1–10

Document S2. Article plus supplemental information