Abstract

Background

Elbow trochlea osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is rare with limited information on it. The aim of this systematic review is to assess the published evidence on trochlea OCD in terms of presenting symptoms, location of OCD and outcome of management in adolescent patients.

Patient & Methods

A review of the online databases MEDLINE and Embase was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. The review was registered prospectively in the PROSPERO database. Clinical studies reporting on any aspect of trochlea OCD management were eligible for inclusion and appraised using the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS) tool.

Results

16 studies were eligible for inclusion with a total of 75 elbow. Mean age was 14 years (8–19) of which 46 were males. The main presenting symptoms were pain (95%). Non-operative care was reported in 86% of elbows with resolution of symptoms in 76%. Surgical management was described in 14%. There were equal number of arthroscopic and open procedures. 94% had successfully resolution of symptoms post-operatively.

Conclusion

Elbow trochlea OCD is a rare pathology and one that can be managed non-operatively in the majority of cases with good resolution of symptoms. However, if this fails, operative options are available with excellent results reported.

Level of evidence

Level IV, Systematic review.

Keywords: elbow, trochlea, osteochondritis dissecans, OCD, pain, non-operative, overhead activities

Introduction

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) represents separation of an area of articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone with sclerosis, fragmentation and resorption of differing degrees.1,2 In the elbow, the lesion almost always occurs in the capitellum2,3 although it can also affect the trochlea, radial head or olecranon fossa.4–6 OCD is common in the adolescent group especially those with overuse and/or involved in overhead activities.7,8

OCD of trochlea is rare and is reported between 2.5% 9 to 7% 10 of all elbow OCD lesions. There is no clear underlying mechanism but a suggested contributing factor is the precarious blood supply to the posterioinferior aspect of the lateral trochlea.11,12 An additional increase in the intraosseous pressure may also compromise the poorly perfused area of trochlea. 11 In an overhead athlete this blood supply can be further compromised from impingement with repetitive elbow extension. It is possible to mistake the fragmentation of trochlear ossification centres as OCD. 13 Hence the age of the patient and location of the lesions is imperative in making the correct diagnosis.

The published literature regarding trochlea OCD is limited when compared to capitellum OCD, with no clear consensus on management. 14 The aim of this systematic review is to assess the published evidence on trochlea OCD in terms of presenting symptoms, location of OCD lesion and outcome of management in adolescent patients.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines using the online databases Medline and EMBASE. The review was registered prospectively on the PROSPERO database. The searches were performed independently by two authors on the 12 March 2021 and repeated on the 25 March 2021 to ensure accuracy. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between these two authors, with the senior author resolving any residual differences. The Medline and Embase search strategies are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy.

| PubMed | EMBASE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Humerus or humeral or elbow | (Humerus or humeral or elbow).mp |

| 2. | Trochlea | Trochlea.mp |

| 3. | Osteochondritis dissecans | Osteochondritis dissecans.mp |

| 1 and 2 and 3 | 1 and 2 and 3 | |

| Results: 23 | Results: 40 |

Clinical studies reporting on cases of trochlea OCD in adolescent patients were included. Studies reporting on any aspect of trochlea OCD management were eligible for inclusion. Only primary research published in the English language was considered for review with any abstracts, comments, review articles and technique articles excluded.

The clinical studies were appraised independently by two authors and quality assessment of non-randomised studies was completed using the Methodological index for non-randomised studies (MINORS) tool [30]. MINORS is a validated scoring tool for non-randomised studies. Each of the 12 items in the MINORS criteria were given a score of 0, 1, or 2, with maximum scores of 16 and 24 for non-comparative and comparative studies, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square analysis (with Fisher's exact test) was used to evaluate differences in categorical data between groups. A p value threshold of 0.05 was used for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using Excel version 16.52 (Microsoft, USA).

Results

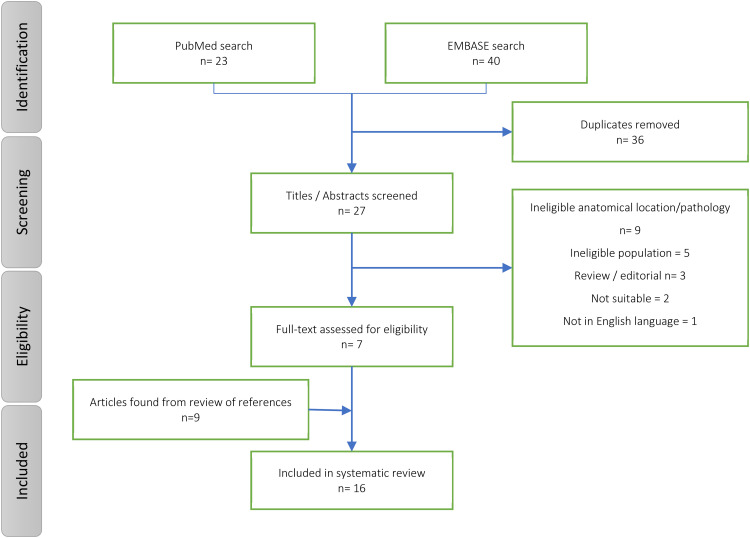

The initial search strategy generated 63 studies. After a review of titles, abstracts and references, 16 studies were eligible for inclusion; 2 non-randomised comparative case series, 6 case series and 8 case reports. The selection process is illustrated in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses flow chart (Figure 1). There were a total of 75 elbows in 70 patients with trochlea OCD. The mean age of patients was 14 years (8 to 19). There were 46 males and 24 females. The mean follow-up time was 16.3 months (5 to 50). The right elbow was affected in 67% (n = 50) of cases and the dominant side was involved in 73% (n = 48/66) of cases. When documented, patients were involved in overhead sports in 90% (n = 45/50) of cases with baseball pitchers being the most commonly (42% - n = 21/50) affected group. Study characteristics are summarised in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of review process.

Table 2.

Characteristic of included studies.

| Study | Population | Predominant symptoms (n elbows) |

Sport (Overhead) | Lesion location (n) |

Mean follow-up, months, (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2019 n = 28 |

13.4 (± 1.6 SD) 13 Males |

Pain (26/28) Crepitus (15/28) Locking (9/28) Loss of ROM (9/28) |

28/28 (24/28) | Lateral (25/28) Medial (3/28) |

13 (± 8 SD) |

| Collins and Tiegs-Heiden. 2019 n = 5 |

16 (15-19) All male |

Pain (6/6) Crepitus (2/6) |

5/5 (4/5) |

Lateral (6/6) |

7 (1-30) |

| Annamalai 2019 n = 1 |

11 Male |

Pain (1/1) Loss of ROM (1/1) |

1 (1) |

Medial (1) |

9 |

| Naidu et al. 2017 n = 8 |

13.5 (11-17) 6 Males |

Pain (8/8) Loss of ROM (5/8) |

- | Lateral (8/8) |

6 |

| Kaji et al. 2015 n = 1 |

14 - |

Pain in left elbow (1/2) Right elbow asymptomatic |

1 (1) |

Medial (1) | 24 |

| Alici 2015 n = 1 |

12 Male |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) |

- | Lateral (1) | 6 |

| Lee and Kim 2014 n = 1 |

14 Male |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) |

1 (1) |

Medial (1) | 5 |

| Miyake et al. 2013 n = 1 |

14 Male |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) |

1 (1) |

Lateral (1) | 24 |

| Pruthi et al. 2009 n = 2 |

13 - |

Pain (1/2) Crepitus (1/2) Clicking (1/2) |

1/2 (1/2) |

Lateral (2/2) | - |

| Namba et al. 2009 n = 1 |

19 Male |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) |

Medial (1) | 24 | |

| Marshall et al. 2009 n = 13 |

14 11 Males |

Pain (13/13) Loss of ROM (10/13) Clicking (3/13) |

9/13 (9/13) |

Lateral (10/13) Medial (3/13) |

- |

| Ansah et al. 2007 n = 1 |

15 Male |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) |

1 (1) |

- | 50 |

| Patel et al. 2002 n = 2 |

13 2 Males |

Pain (3/3) Loss of ROM (1/3) |

Medial (3) | 36 | |

| Joji et al. 2001 n = 1 |

17 Male |

Pain (1) | 1 (1) |

Lateral (1) | 10 |

| Vanthournout et al. 1991 n = 1 |

12 - |

Pain (1) Loss of ROM (1) Crepitus (1) |

1 (1) |

Lateral (1) | - |

| Clarke et al. 1983 n = 3 |

12 2 Males |

Pain (4/4) Loss of ROM (1/4) |

- | Medial (4/4) |

ROM, range of motion; AVN, avascular necrosis; OCD, osteochondirits dissecans;.

Radiological diagnosis

All 16 studies reported OCD diagnosis on radiographic findings (Table 3). Radiographic findings were described as radiolucent areas in 8 studies,15–22 fragmentation in 3 studies23,24 and lytic areas in 2 studies.5,25 Three studies19,21,22 stated radiographs were deemed normal initially but a retrospective review confirmed OCD. Fourteen studies carried out further MRI to confirm OCD but just 2 studies19,22 commented OCD classification. Two studies23,24 did not perform a MRI, one of which performed a CT scan of the elbow. 24 Overall, all the cases that had a CT showed the lesion clearly, whereas MRI was best for bone marrow oedema rather than precise geographical location.

Table 3.

Summary of radiological findings of all studies.

| Study | XR diagnosis | CT diagnosis | MRI diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2019 | Yes Initially deemed normal however on retrospective review radiolucency was observed in the trochlear region |

No | Yes Most showed lateral trochlear OCD; >50% also had capitelar involvement |

| Collins and Tiegs-Haiden 2019 | Yes Most were normal however 1pt had trochlea lucency and sclerosis |

Yes Showed cystic lesions with hypertrophic bone and osseous fragments |

Yes Identified bone marrow oedema, cystic changes and fragments |

| Annamalai 2019 | Yes Trochlear sclerosis and fragmentation |

No | Yes Trochlear fragmentation |

| Naidu et al. 2017 | Yes Initially reported normal however on retrospective review - lucencies within intracondylar notch – mimicking pseudointracondylar notch |

No |

Yes Confirmed trochlear lesions |

| Kaji et al. 2015 | Yes Radiolucent lesion in trochlear grove |

Yes Confirmed x-ray findings |

Yes Central trochlear OCD Subchondral defects |

| Nedeni 2015 | Yes Radiolucent lesion in trochlear notch |

No | Yes Lateral trochlea OCD/AVN |

| Lee and Kin 2014 | Yes Radiolucent lesion in trochlear grove |

Yes Confirmed x-ray findings |

Yes Medial trochlea OCD |

| Miyake et al. 2013 | Yes Lateral trochlea OCD Lytic area with condensed borders in the intracondylar notch |

No | Yes Lateral trochlea OCD |

| Pruthi et al. 2009 | Yes Initially reported normal however on retrospective review - lucencies within the intracondylar notch – mimicking a pseudointracondylar notch |

Yes Lateral OCD trochlea |

Yes Lateral trochlea OCD |

| Namba et al. 2009 | Yes Cubitus varus deformity and a radiolucent lesion in the ulnar area of the humeral trochlea, with condensed borders and a small fragment within the lesion |

Yes Radiolucent area with a clear border and a small separated fragment in the central part of the ulnar side of the humeral trochlea |

Yes Low-intensity area on the ulnar side of the trochlea |

| Marshal et al. 2009 | Yes With hindsight most of the radiographs showed trochlear lucencies |

Yes Performed but not described in detail |

Yes Showed lateral and medial lesions |

| Ansah et al. 2007 | Yes Not eluded which area of trochlea affected |

No | Yes Not eluded which area of trochlea affected |

| Patel et al. 2002 | Yes Medial trochlea OCD Radiolucency within trochlea |

Yes Medial trochlea OCD Radiolucent area within the trochlea |

Yes Medial trochlea OCD Trochlear radiolucency |

| Joji et al. 2001 | Yes Medial trochlea OCD Trochlear fragmentation |

Yes Medial trochlea OCD Trochlea fragment protrusion |

No |

| Vanthournout et al. 1991 |

Yes Lateral trochlea OCD Lytic area with condensed borders in the trochlea |

Yes Lateral trochlea OCD |

Yes Lateral trochlea OCD Low signal on T1 W and T2 images + discontinuity of fragment |

| Clarke et al. 1982 | Yes Increased density or fragmentation of trochlear epiphysis |

No | No |

OCD, osteochondritis dissecans; AVN, avascular necrosis.

Site of lesion

A total of 74 out of 75 elbows had documentation of location of trochlea OCD. Only one study did not document the exact location of trochlea OCD. The commonest location was lateral trochlea in 77% (n = 57) of cases with medial trochlea found only in 23% (n = 17) of elbows. No case had any involvement of both medial or lateral trochlea at the same time.

Non-operative treatment

Only one study did not report on surgical treatment modality, 21 with non-operative treatment described initially in 86% of elbows (63/73). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and/or activity modification and/or elbow immobilisation were described in four studies.15,19,25,26 Two studies20,23 did not specify what non-operative treatment entailed (Table 4). From the non-operative group 15 elbows (24%)11,18,22–24,27 failed to improve and subsequently went on to have operative treatment between 5 months to 3.5 years.

Table 4.

Operative or non-operative management.

| Study | n (elbows) | Non-operative | Operative | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2019 | 28 | 28 | 4 after failure of non-op | 44% of non-op patients were asymptomatic 75% of surgical patients had resolution of pain |

| Collins and Tiegs-Heiden.2019 | 6 | - | 6 | All patients returned to sports at 3 months |

| Annamalai 2019 | 1 | 1 | - | Pain free at 3 weeks, returned to sport at 8 weeks. Remained symptom free at 9 months |

| Naidu et al. 2017 | 8 | 8 | - | All patients improved at 6 months. 25% had loss of ROM |

| Kaji et al. 2015 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Operated left improved symptomatically at 6 weeks, radiologically at 3 months non-op right asymptomatic and lesion was no longer present at 5 months |

| Alici 2015 | 1 | 1 | - | Pain and complete ROM improved by 6 months |

| Lee and Kim 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 after failure of non-op | At 5 months returned to baseball |

| Miyake et al. 2013 | 2 | 2 | - | At 2yrs – remained asymptomatic and playing baseball |

| Pruthi et al. 2009 | 2 | n/a | n/a | No mention of treatment |

| Namba et al. 2009 | 1 | - | 1 | Eight months post-op patient was pain free and returned to previous activities |

| Marshall et al. 2009 | 13 | 13 | 6 after failure of non-op | All medial side trochlear OCDs improved with conservative care All surgical patients have returned to sporting activities |

| Ansah et al. 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 after failure of non-op | At time of final follow up (50months), remained asymptomatic and both x-ray and MRI showed complete resolution of lesion |

| Patel et al. 2002 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 At 18 months full range of motion & at 3yrs asymptomatic 1 at 2yrs asymptomatic |

| Joji et al. 2001 | 1 | 1 | 1 after failure of non-op | 5 months post-op returned to playing baseball |

| Vanthournout et al. 1991 | 1 | - | 1 | Procedure was diagnostic – no mention of outcomes |

| Clarke et al. 1983 | 4 | 4 | 2 after failure of non-op | 1 Symptoms resolved at 6 months – confirmed asymptomatic at 3yrs 1 post-op symptoms resolved within few months 1 At 2yrs had on/off symptoms – no further interventions |

| Total | 75 | 63 | 25 (15 after failure of non-op) |

Operative treatment

Ten elbows (14%) from 5 studies described operative treatment as the initial and only modality of management provided.5,16,17,20,28 15 (23.8%) elbows from the non-operative group subsequently underwent operative treatment (Tables 4 & 5). Overall, 25 (34%) elbows underwent operative treatment.5,11,16–18,20,22,24,27,28 A number of different surgical procedures were performed but broadly these were arthroscopic in 13 elbows and open surgeries in 12 elbows. For arthroscopic treatment of trochlea lesion (Table 5), microfracture and debridement was carried out in over two-third of the cases (77%) followed by removal of loose bodies (23%). For open procedures, drilling or microfracture and debridement were the most common procedures (50%). A breakdown of procedures has been provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of operative treatment of elbow trochlea OCD.

| Procedure | Open | Arthroscopic |

|---|---|---|

| Curettage, Microfracture/debridement, Drilling | 6b (50%) | 10 a (77%) |

| Retrograde nailing | 1 (8.3%) | - |

| Osteophyte/loose body removal | - | 3 (23%) |

| Osteochondral transplantation from lateral femoral condyle (non-weight bearing area) | 1 (8.3%) | - |

| Defect filled from olecranon / Bone graft | 2 (16.7%) | - |

| Anterior capsular release | 1 (8.3%) | - |

| Olecranon osteotomy and fixation of OCD | 1 (8.3%) | - |

| Total | 12 | 13 |

included synovectomy and plica resection.

also correction of varus deformity in one patient.

Operative vs non-operative treatment

Two studies compared non-operative to operative treatment. Wang et al. 22 treated all patients non-operatively initially with activity modification for 3 months and locked hinge brace if an acute presentations (pain <2 weeks). A comparison of 9 patients managed non-operatively with 4 undergoing surgery at a mean follow-up of 13 ± 8 months was reported. Surgery included drilling in 2 patients, olecranon osteotomy and OCD fixation with bioabsorbable implants in one patient and biopsy and bone graft implant in the 4th patient. 75% (3 of 4) patients undergoing surgery had resolution of pain, whilst in the non-operative group this figure stood at 66.6% (6 of 9). Ongoing crepitus was reported in 50% (2 of 4) of the surgical group and 55.6% (5 of 9) in the non-operative group.

Marshal et al. 11 described 13 patients with trochlear OCD, all whom were initially treated non-operatively. This included a period of rest followed by physiotherapy and gradual return to sport. Six patients (all lateral trochlea OCD) failed to improve hence ultimately underwent arthroscopy with the other 7 treated non-operatively (3 medial and 4 lateral trochlea OCD). Of the operative group, 3 patients had arthroscopy, synovial debulking and plica resection and the other three had debridement and micro-fracturing. Follow-up time was not stated but all had improvement of symptoms and had returned to sporting activities. Similarly, all non-operatively managed patients had resolution of symptoms and return to sporting activities.

Outcome of treatment

Outcome of non-operative or operative treatment were assessed subjectively only (Table 4). Resolution of symptoms was assessed in all bar 2 studies.5,21 In addition, radiological findings either by simple radiographs or repeat scans (MRI and/or CT) were evaluated in 10 studies.16–18,20,22–25,27,28 Seven studies also reported on return to sports or activities11,16,18,24–27.

Non-operative care was described in 63 elbows as the initial treatment choice however 15 (24%) elbows failed to improve resulting in 48 being treated purely non-operatively. Follow-up data for pain was available for 66.6% (32 of 48) of elbows whereas for range of motion this figure stood at 48% (23 of 48), with results indicating 91% resolution for both outcomes, respectively. Radiological assessment was available for 13 elbows. There was resolution of OCD in 6 (46%), improvement in 3 (23%), unchanged appearances in 2 (15%) and 1 (8%) was reported worse. Where applicable all patients who participated in sports returned to their usual activities.

Of the 25 patients treated operatively, follow up data was again incomplete. Pain resolution was reported in 95% (21 of 22) of elbows. Radiological resolution of OCD was described in only 8 elbows (32%) with all 8 displaying resolution. Data on return to sport was available for 13 patients and with all reported to have returned to previous activities.

Gender differences

From the available data on gender, trochlea OCD was significantly higher in males compared to females (p < 0.0001). There was no significant difference between arm dominance and overhead sports. Pain was still the most common presenting symptom in both genders. Lateral trochlea was more involved in both males and females compared to medial but there was no significant difference between the genders (p = 0.55).

Outcome of medial vs lateral trochlea

Complete data was available for 46 patients to analyse medial and lateral trochlea outcomes. There were 32 lateral and 14 medial trochlea OCD. There was no difference in arm dominance (p = 0.90) or involvement in overhead sports. Definitive non- operative treatment was in 56% vs 57% cases of medial vs lateral respectively while operative treatment was also similar with 44% vs 43% cases of medial vs lateral respectively.

Discussion

The main finding of this systematic review is that elbow trochlea OCD can be managed non-operatively with good resolution of symptoms in 91% of adolescents. Operative treatment is an option for those lesions not responding to conservative therapy including activity medication, immobilisation, physiotherapy and analgesics.

The main presenting symptoms of capitellum OCD in a recent SR was pain reported in 87.1% of studies. 14 In this SR, 100% (16/16) studies had reported pain as the most common symptom of trochlea OCD and was described in 95% of cases (70/74). Loss of range of movement is the second most common presenting symptoms (43%) while crepitus was described in 26% of the cases in this SR. The symptoms were more common on the dominant side (73%) and in overhead athletes (93%). Thus, a painful elbow in an adolescent doing overhead sports should prompt the clinician to review the trochlea for OCD in addition to capitellum.

In this SR, the lateral trochlea had the highest site of OCD (77%) and the ossification centres typically close between the ages of 13 to 16 years. The cause of trochlea OCD remains unclear but contributory factors as in all OCD include repetitive loading precarious bloody supply. 29

There was no clear consensus on which trochlea OCD lesions would be suitable for open or arthroscopic surgery. In this SR, for arthroscopic treatment of trochlea lesion, microfracture and debridement was carried out in two-third of the cases (77%) followed by removal of loose bodies (23%). Open surgery included curettage, drilling and debridement (50%) defect filled with bone graft (8.3%), from olecranon (8.3%) and lateral femoral condyle autograft (8.3%). In a recent SR, the most common arthroscopic procedure for capitellum OCD was removal of loose bodies and drilling ± debridement while most common open procedure was OATS (Osteochondral Autograft Transplantation) procedure. 14 However, previous studies on capitellum treatment have shown that open and arthroscopic procedures have similar return to sports.30–32 Therefore, further studies are required before guidance can be provided on whether either arthroscopic or open procedures are optimal for trochlea OCD.

Resolution of symptoms were similar between the operative (95%) and non-operative groups (91%). However, follow up data was significantly lower in the non-operative group (60%) when compared to the surgical group (88%). Similarly, if we consider intention to treat analysis for the non-operative cohort then the overall success rate is significantly lower standing at 62% (29 out of 47). In studies that reported on activities both forms of treatment proved effective in returning their patients to their sports.

It is difficult to drive a consensus on which lesions are suitable for non-operative or operative treatment so each case must be assessed clinically and radiologically. Some authors have suggested using treatment guidelines for capitellar lesions 20 whereby lesions that remain intact can be managed non-operatively usually with a trial of immobilisation and analgesia.33,34 If non-operative treatment has failed, surgery can be indicated when there is fracture of articular cartilage, for symptomatic removal of loose bodies or if there is a detached or displaced OCD lesion.33,35,36 However, extrapolating the use of guidelines of capitellar lesions for trochlea OCDs has not been proven. There were no re-operations reported in any studies for any reason and no complications other than one patient who had a femoral chondral autograft discomfort.

Where radiological findings were reported for trochlea OCD lesion, fragmentation was described as one of the features. Fragmentation has been reported in other bones of axial skeleton, as well as upper and lower limb and is described as part of osteochondrosis. In the axial skeleton, it has been described for Scheuermann disease whereas in appendicular skeleton it has been described for Panner disease (epiphysis of capitellum), Legg–Calvé–Perthes (proximal femoral epiphysis), Sever, Köhler (tarsal navicular) and Freiberg disease (deformities of the epiphyses of distal 2nd or 3rd metatarsal). 37 Osteochondrosis is most likely to be as a result of multiple factors such as poor vascular supply, microtrauma or even a traumatic event as is OCD of trochlea. It is therefore likely that trochlea OCD follows similar pattern to osteochondroses in other bones of the body and can be self-limiting in majority of the cases with resolution of symptoms following a trial of rest and physical therapy as in found in this SR. Ostechondrosis seems to affect the round bones and it seems that trochlea has similar round structure and may undergo a similar process.

There are several limitations of this systematic review. The studies only provide level IV and V evidence as well as providing only 75 elbows in 70 patients in total for analysis. There is heterogeneity in severity of lesion, outcome measures and operative techniques which limit collation of data. A lack of any control groups means that direct comparison to other surgical techniques is not possible. Furthermore, only a handful of post-operative patients had any radiographic follow-up with no two patients having had the same surgical treatment and therefore making any comparison to be objective. Table 6 illustrates the MINORS criteria which ranged from 10 to 16 showing the overall quality of the papers included was low. Furthermore, studies with larger series of patients had significant loss to follow up conversely limiting meaningful interpretation of overall results.16,22

Table 6.

Methodological index for non-randomised studies (MINORS) scores.

| Study | MINORS Score |

|---|---|

| Wang et al. 2019 | 12 |

| Collins and Tiegs-Heiden. 2019 | 11 |

| Annamalai 2019 | n/a |

| Naidu et al. 2017 | 14 |

| Kaji et al. 2015 | n/a |

| Alici 2015 | n/a |

| Lee and Kim 2014 | n/a |

| Miyake et al. 2013 | n/a |

| Pruthi et al. 2009 | n/a |

| Namba et al. 2009 | n/a |

| Marshall et al. 2009 | 14 |

| Ansah et al. 2007 | 16 |

| Patel et al. 2002 | 10 |

| Joji et al. 2001 | n/a |

| Vanthournout et al. 1991 | n/a |

| Clarke et al. 1983 | 10 |

As there is limited information in literature on this rare pathology, this SR provides an overview on management of elbow trochlea OCD and suggests that non-operative treatment should be trialled with a period of immobilisation and analgesics and physical therapy.

Based on this review we suggest the following recommendations: (1) Trochlea OCD is a rare condition in adolescents, but should be considered in the overhead athlete, with elbow pain. (2) Imaging should include plain radiographs and MRI, however if still inconclusive then a CT can be utilised to evaluate subchondral bone separation. (3) A trial of non-operative treatment for up to 6 months such as rest/activity modification; immobilisation/splinting, physiotherapy and/or analgesics should be considered initially however if no resolution in symptoms then surgical intervention can be recommended. (4) Lastly, we suggest elbow trochlea OCD patients following initial investigation and treatment plan (operative or non-operative) have interval follow-up at 1, 3 and 5 years to understand the pathology better. Furthermore, patient reported outcome measures pre- and post-treatment would give an objective assessment of the elbow function following the treatment plan.

Conclusion

Elbow trochlea OCD is a rare pathology that usually presents with pain in the overhead young athlete. The majority of cases can be managed non-operatively with good resolution of symptoms.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Shahbaz S Malik https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5272-7410

Robert W Jordan https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6495-475X

Correction (August 2023): Article updated online from “Damir Rasodivic” corrected to “Damir Rasidovic”.

References

- 1.Edmonds EW, Polousky J. A review of knowledge in osteochondritis dissecans: 123 years of minimal evolution from könig to the ROCK study group. Clin Orthop 2013; 471: 1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stubbs MJ, Field LD. Savoie FH 3rd. Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 2001; 20: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nissen CW. Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 2014; 33: 251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bednarz PA, Paletta GA, Stanitski CL. Bilateral osteochondritis dissecans of the knee and elbow. Orthopedics 1998; 21: 716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanthournout I, Rudelli A, Ph V, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans of the trochlea of the humerus. Pediatr Radiol 1991; 21: 600–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trias A, Ray RD. Juvenile osteochondritis of the radial head: REPORT OF A BILATERAL CASE. J Bone Jt Surg 1963; 45: 576–582. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradley JP, Petrie RS. Osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral capitellum. Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Sports Med 2001; 20: 565–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logli AL, Bernard CD, O’Driscoll SW, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the capitellum in overhead athletes: a review of current evidence and proposed treatment algorithm. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2019; 12: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss JM, Nikizad H, Shea KG, et al. The incidence of surgery in osteochondritis dissecans in children and adolescents. Orthop J Sports Med 2016; 4: 232596711663551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen JC, Degnan AJ, Barrera CA, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow in children: MRI findings of instability. Am J Roentgenol 2019; 213: 1145–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall KW, Marshall DL, Busch MT, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the humeral trochlea in the young athlete. Skeletal Radiol 2009; 38: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi K, Sweet FA, Bindra R, et al. The extraosseous and intraosseous arterial anatomy of the adult elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997; 79: 1653–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong TT, Lin DJ, Ayyala RS, et al. Elbow injuries in pediatric overhead athletes. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017; 209: 849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen D, Kay J, Memon M, et al. A high rate of children and adolescents return to sport after surgical treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021; 29: 4041–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alici T. A rare cause of elbow pain: hegemanns disease. J Clin Anal Med 2015; 6: 499–501. DOI: 10.4328/JCAM.1061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins MS, Tiegs-Heiden CA. Osteochondral lesions of the lateral trochlear ridge: a rare, subtle but important finding on advanced imaging in patients with elbow pain. Skeletal Radiol 2020; 49: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaji Y, Nakamura O, Yamaguchi K, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans involving the trochlear groove treated With retrograde drilling: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Kim MS. Osteochondritis dissecans in medial trochlea of the humerus in a pitcher: a case report. Clin Shoulder Elb 2014; 17: 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naidu D, Anand D, Thanigai D. Study of outcome of conservative management in osteochondritis dissecans of trochlea. Int J Orthop Sci 2017; 3: 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel N, Weiner SD. Osteochondritis dissecans involving the trochlea: report of two patients (three elbows) and review of the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22: 48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruthi S, Parnell SE, Thapa MM. Pseudointercondylar notch sign: manifestation of osteochondritis dissecans of the trochlea. Pediatr Radiol 2009; 39: 180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang KK, Bixby SD, Bae DS. Osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral trochlea: characterization of a rare disorder based on 28 cases. Am J Sports Med 2019; 47: 2167–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clarke NM, Blakemore ME, Thompson AG. Osteochondritis of the trochlear epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 1983; 3: 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joji S, Murakami T, Murao T. Osteochondritis dissecans developing in the trochlea humeri: a case report. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001; 10: 295–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyake J, Kataoka T, Murase T, et al. In-vivo biomechanical analysis of osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral trochlea: a case report. J Pediatr Orthop Part B 2013; 22: 392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Annamalai S. Osteochondritis of trochlear epiphysis: an interesting case report with literature search. International Journal of Paediatric Orthopaedics 2019; 5: 28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ansah P, Vogt S, Ueblacker P, et al. Osteochondral transplantation to treat osteochondral lesions in the elbow. J Bone Jt Surg 2007; 89: 2188–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Namba J, Shimada K, Akita S. Osteochondritis dissecans of the humeral trochlea with cubitus varus deformity. A case report. Acta Orthop Belg 2009; 75: 265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cruz AIJ, Shea KG, Ganley TJ. Pediatric knee osteochondritis dissecans lesions. Orthop Clin North Am 2016; 47: 763–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen G, Boyer P, Pujol N, et al. Endoscopically assisted reconstruction of acute acromioclavicular joint dislocation using a synthetic ligament. Outcomes at 12 months. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res OTSR 2011; 97: 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirsch JM, Thomas JR, Khan M, et al. Return to play after osteochondral autograft transplantation of the capitellum: a systematic review. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg Off Publ Arthrosc Assoc N Am Int Arthrosc Assoc 2017; 33: 1412–1420.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Li YJ, Guo SY, et al. Is there any difference between open and arthroscopic treatment for osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the humeral capitellum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthop 2018; 42: 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson RK, Savoie FH, 3rd, Field LD. Osteochondritis dissecans of the elbow. Instr Course Lect 1999; 48: 393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takahara M, Shundo M, Kondo M, et al. Early detection of osteochondritis dissecans of the capitellum in young baseball players. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998; 80: 892–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chess D. Osteochondritis. In: Savoie FH, III, Field LD. (eds) Arthroscopy of the elbow. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996, pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaughnessy W, Bianco A. Osteochondritis dissecans. In: Morrey BF. (ed) The elbow and its disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1993, pp. 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 37.West EY, Jaramillo D. Imaging of osteochondrosis. Pediatr Radiol 2019; 49: 1610–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]