Key Points

Question

Did racial and ethnic minority adults with cancer in the United States experience more cancer care delays and adverse social and economic effects than White adults during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In this survey study of 1240 US adults with cancer, Black and Latinx adults reported experiencing higher rates of delayed cancer care and more adverse social and economic effects than White adults.

Meaning

This study suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with disparities in the receipt of timely cancer care among Black and Latinx adults.

Abstract

Importance

The full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care disparities, particularly by race and ethnicity, remains unknown.

Objectives

To assess whether the race and ethnicity of patients with cancer was associated with disparities in cancer treatment delays, adverse social and economic effects, and concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic and to evaluate trusted sources of COVID-19 information by race and ethnicity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national survey study of US adults with cancer compared treatment delays, adverse social and economic effects, concerns, and trusted sources of COVID-19 information by race and ethnicity from September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021.

Exposures

The COVID-19 pandemic.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was delay in cancer treatment by race and ethnicity. Secondary outcomes were duration of delay, adverse social and economic effects, concerns, and trusted sources of COVID-19 information.

Results

Of 1639 invited respondents, 1240 participated (75.7% response rate) from 50 US states, the District of Columbia, and 5 US territories (744 female respondents [60.0%]; median age, 60 years [range, 24-92 years]; 266 African American or Black [hereafter referred to as Black] respondents [21.5%]; 186 Asian respondents [15.0%]; 232 Hispanic or Latinx [hereafter referred to as Latinx] respondents [18.7%]; 29 American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or multiple races [hereafter referred to as other] respondents [2.3%]; and 527 White respondents [42.5%]). Compared with White respondents, Black respondents (odds ratio [OR], 6.13 [95% CI, 3.50-10.74]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 2.77 [95% CI, 1.49-5.14]) had greater odds of involuntary treatment delays, and Black respondents had greater odds of treatment delays greater than 4 weeks (OR, 3.13 [95% CI, 1.11-8.81]). Compared with White respondents, Black respondents (OR, 4.32 [95% CI, 2.65-7.04]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 6.13 [95% CI, 3.57-10.53]) had greater odds of food insecurity and concerns regarding food security (Black respondents: OR, 2.02 [95% CI, 1.34-3.04]; Latinx respondents: OR, 2.94 [95% CI, [1.86-4.66]), financial stability (Black respondents: OR, 3.56 [95% CI, 1.79-7.08]; Latinx respondents: OR, 4.29 [95% CI, 1.98-9.29]), and affordability of cancer treatment (Black respondents: OR, 4.27 [95% CI, 2.20-8.28]; Latinx respondents: OR, 2.81 [95% CI, 1.48-5.36]). Trusted sources of COVID-19 information varied significantly by race and ethnicity.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this survey of US adults with cancer, the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with treatment delay disparities and adverse social and economic effects among Black and Latinx adults. Partnering with trusted sources may be an opportunity to overcome such disparities.

This survey study assesses whether the race and ethnicity of patients with cancer was associated with disparities in cancer treatment delays and adverse social and economic effects during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic delayed cancer screening1,2 and surgical procedures3 worldwide, with unknown implications for cancer mortality rates. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, race and ethnicity–based disparities were prevalent in the United States, with lower rates of timely, evidence-based cancer care4,5,6 and higher premature death rates among Black and Latinx adults than other racial and ethnic groups.7,8 The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the association of systemic racism and associated inequities in the structural, economic, and socioenvironmental system with these long-standing health disparities.9,10 However, the full effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on disparities in cancer care and cancer deaths remains unknown.11,12

Since March 2020, Black and Latinx adults have experienced the highest rates of excess morbidity and mortality from COVID-1913 and other causes14 as well as unemployment.15 Medical care disruptions, including cancer screening and treatment delays among Black and Latinx adults with cancer,16,17 and disparate adverse social and economic effects fuel concerns regarding the presence of more advanced cancer stages at diagnosis, avoidable cancer deaths,18,19,20 and widening of existing race and ethnicity–based disparities in cancer.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study evaluating the association of the COVID-19 pandemic with patient-reported cancer care delays, concerns, and adverse social economic effects by race and ethnicity. Specifically, we sought to evaluate whether racial and ethnic minority adults with cancer, compared with White adults with cancer, experienced more cancer care disruptions, concerns regarding health outcomes, adverse social and economic effects, and concerns regarding the association of COVID-19 with adverse social and economic factors. We also sought to evaluate trusted sources of COVID-19 information by race and ethnicity.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study using a 74-question online survey in English, Spanish, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Hindi to assess patient-reported experiences from September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021. The survey collected the following: (1) demographic characteristics (eg, gender identity, race and ethnicity, age, income, educational level, and insurance status), (2) clinical characteristics (eg, cancer diagnosis, stage, and treatment), (3) modifications in care, (4) adverse social and economic effects, (5) concerns regarding cancer and other health outcomes, (6) concerns regarding future adverse social and economic effects, and (7) trusted sources of COVID-19 information (eAppendix in the Supplement). Individuals 18 years of age or older with cancer who consented to the study procedures were invited to participate and received no compensation for their participation. Participants were provided with a consent form online and if they participated in the survey, they had consented to participation. Date of diagnosis was not a consideration for inclusion. All survey responses were anonymous unless participants voluntarily provided their name and contact information. The Stanford University School of Medicine institutional review board reviewed and approved the study. This study followed the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) reporting guideline for survey studies.21

We used a variety of techniques to distribute the survey, including a virtual snowball sampling technique. We distributed the survey link directly to participants in collaboration with clinicians and through online listservs in collaboration with patient advocacy groups and organizations, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Latino Cancer Institute, the Susan G. Komen Foundation, and the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, with an emphasis on recruitment of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups. We also promoted the survey on social media. The response rate was calculated among those who directly received the survey link.

We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for 21 factors associated with delays in cancer care, concerns regarding health outcomes, experiences and concerns regarding adverse social and economic effects, and trusted sources of COVID-19 information. We combined self-reported race and ethnicity to create categories of African American or Black (hereafter referred to as Black), Asian, Hispanic or Latinx (hereafter referred to as Latinx), other (comprised of American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or multiple races), and White non-Latinx (hereafter referred to as White). We calculated all ORs relative to White participants. We adjusted models for a priori selected sociodemographic variables (gender identity, age, educational level, income, insurance status, and place of residence) and clinical variables (cancer diagnosis and stage) associated with delays in care.22,23

To account for respondents with unknown cancer stage, we imputed unknown values for cancer stage using multiple imputation24 over 100 simulated iterations based on the age, gender identity, place of residence, income, educational level, insurance, and cancer diagnosis of each respondent. In 2 sensitivity analyses, we coded unknown cancer stage as a separate category within the cancer stage variable and conducted a complete-case analysis among participants with a reported known cancer stage. All analyses were 2-sided and conducted using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp LLC), with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

We distributed survey links directly to 1639 individuals; 1240 participated (75.7% response rate), 1128 [91.0%] completed the full survey, and 112 [9.0%] completed 87% of the survey (eFigure in the Supplement). We included 1240 respondents in the analyses.

Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 lists the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 1240 study participants (186 Asian participants [15.0%]; 266 Black participants [21.5%]; 232 Latinx participants [18.7%]; 29 participants of other race or ethnicity [2.3%], which comprised 3 Native Hawaiian participants [0.2%], 2 Alaska Native participants [0.2%], 9 American Indian participants [0.7%], and 15 participants of multiple races [1.2%]; and 527 White participants [42.5%]; 467 male participants [37.7%], 744 female participants [60.0%], and 29 nonbinary participants [2.3%]; median age, 60 years [range 24-92 years]). Respondents represented 50 US states, the District of Columbia, and 5 US territories, including American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands. A higher proportion of Asian respondents (80 of 186 [43.0%]), Latinx respondents (86 of 232 [37.1%]), and respondents of other race or ethnicity (15 [51.7%]) resided in the West, and a higher proportion of Black respondents (93 [35.0%]) resided in the South.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Participants by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the US From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1240) | African American or Black (n = 266 [21.5%]) | Asian (n = 186 [15.0%]) | Hispanic or Latinx (n = 232 [18.7%]) | White (n = 527 [42.5%]) | Other (n = 29 [2.3%])a | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 467 (37.7) | 153 (57.5) | 104 (55.9) | 76 (32.8) | 118 (22.4) | 16 (55.2) | |||||

| Female | 744 (60.0) | 111 (41.7) | 80 (43.0) | 148 (63.8) | 394 (74.8) | 11 (37.9) | |||||

| Nonbinary | 29 (2.3) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.1) | 8 (3.4) | 15 (2.8 | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Age, median (range), y | 60 (24-92) | 59 (31-88) | 62 (29-72) | 60 (29-92) | 65 (24-88) | 59 (36-86) | |||||

| Place of residence | |||||||||||

| Northeast | 247 (19.9) | 49 (18.4) | 37 (19.9) | 44 (18.4) | 115 (21.8) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Midwest | 236 (19.0) | 54 (20.3) | 28 (15.1) | 26 (11.2) | 125 (23.7) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| South | 322 (26.0) | 93 (35.0) | 35 (18.8) | 56 (24.1) | 132 (25.0) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| West | 386 (31.1) | 62 (23.3) | 80 (43.0) | 86 (37.1) | 143 (27.1) | 15 (51.8) | |||||

| Territory (Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, Northern Mariana Islands, and US Virgin Islands) | 49 (4.0) | 8 (3.0) | 6 (3.2) | 20 (8.6) | 12 (2.3) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| Marital status | |||||||||||

| Married | 672 (54.2) | 161 (60.5) | 99 (53.2) | 93 (40.1) | 304 (57.7) | 15 (51.7) | |||||

| Never married | 86 (6.9) | 10 (3.8) | 8 (4.3) | 12 (5.2) | 55 (10.4) | 1 (3.4) | |||||

| Separated | 54 (4.4) | 14 (5.3) | 5 (2.7) | 13 (5.6) | 18 (3.4) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| Divorced | 290 (23.4) | 59 (22.2) | 63 (33.9) | 81 (34.9) | 80 (15.2) | 7 (24.1) | |||||

| Widowed | 32 (2.6) | 5 (1.9) | 4 (2.2) | 6 (2.6) | 17 (3.2) | 0 | |||||

| Unmarried couple | 48 (3.9) | 6 (2.3) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (3.9) | 29 (5.5) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 58 (4.7) | 11 (4.1) | 5 (2.7) | 18 (7.8) | 24 (4.6) | 0 | |||||

| No. in household | |||||||||||

| 1 (Lives alone) | 94 (7.6) | 11 (4.1) | 4 (2.2) | 11 (4.7) | 64 (12.1) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| 2 | 671 (54.1) | 156 (58.7) | 99 (53.2) | 98 (42.2) | 302 (57.3) | 16 (55.2) | |||||

| 3 | 374 (30.2) | 80 (30.1) | 77 (41.4) | 107 (46.1) | 102 (19.4) | 8 (27.6) | |||||

| ≥4 | 101 (8.2) | 19 (7.1) | 6 (3.2) | 16 (6.9) | 59 (11.2) | 1 (3.5) | |||||

| Household with a member ≤18 y | 816 (65.8) | 230 (86.5) | 166 (89.2) | 188 (81.0) | 213 (40.4) | 19 (65.5) | |||||

| Household with a member ≥65 y | 860 (69.4) | 231 (86.8) | 170 (91.4) | 175 (75.4) | 264 (50.1) | 20 (69.0) | |||||

| Annual household income, $ | |||||||||||

| <25 000 | 122 (9.8) | 39 (14.7) | 18 (9.7) | 18 (7.8) | 44 (8.4) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| 25 000-34 999 | 105 (8.5) | 36 (13.5) | 5 (2.7) | 7 (3.0) | 54 (10.3) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| 35 000-49 999 | 167 (13.5) | 25 (9.4) | 42 (22.6) | 43 (18.5) | 52 (9.9) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| 50 000-99 999 | 616 (49.7) | 119 (44.7) | 106 (57.0) | 139 (60.0) | 243 (46.1) | 9 (31.0) | |||||

| ≥100 000 | 162 (13.1) | 10 (3.8) | 10 (5.4) | 25 (10.8) | 113 (21.4) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 68 (5.5) | 37 (13.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0 | 21 (4.0) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| Educational level | |||||||||||

| <High school | 303 (24.4) | 69 (25.9) | 16 (8.6) | 134 (57.8) | 74 (14.0) | 10 (34.5) | |||||

| High school degree | 149 (12.0) | 41 (15.4) | 37 (19.9) | 33 (14.2) | 38 (7.2) | 0 | |||||

| Some college | 85 (6.9) | 24 (9.0) | 2 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 52 (9.9) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 354 (28.6) | 66 (24.8) | 108 (58.1) | 26 (11.2) | 152 (28.8) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Master’s degree | 190 (15.3) | 25 (9.4) | 14 (7.5) | 29 (12.5) | 117 (22.2) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| Doctorate degree | 91 (7.3) | 4 (1.5) | 4 (2.2) | 6 (2.6) | 73 (13.9) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 68 (5.5) | 37 (13.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0 | 21 (3.8) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| Employment | |||||||||||

| Full-time | 571 (46.0) | 122 (45.9) | 110 (59.1) | 184 (79.3) | 146 (27.7) | 9 (31.0) | |||||

| Part-time | 112 (9.0) | 13 (4.9) | 10 (5.4) | 2 (0.9) | 86 (16.3) | 1 (3.5) | |||||

| Disabled | 94 (7.6) | 7 (2.6) | 4 (2.2) | 16 (6.9) | 61 (11.6) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| Retired | 196 (15.8) | 18 (6.8) | 10 (5.4) | 24 (10.3) | 138 (26.2) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| Unemployed | 198 (16.0) | 106 (39.8) | 52 (28.0) | 6 (2.6) | 27 (5.1) | 7 (24.1) | |||||

| Not looking for work | 152 (76.8) | 104 (98.1) | 16 (30.7) | 5 (83.3) | 21 (77.8) | 6 (85.7) | |||||

| Looking for work | 46 (23.2) | 2 (1.9) | 36 (69.2) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | 1 (14.3) | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 69 (5.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 69 (13.1) | 0 | |||||

| Insurance | |||||||||||

| Medicaid | 315 (25.4) | 46 (17.3) | 66 (35.5) | 153 (66.0) | 43 (8.2) | 7 (24.1) | |||||

| Medicare | 342 (27.6) | 105 (39.5) | 14 (7.5) | 10 (4.3) | 211 (40.0) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Private or dual insurance | 404 (32.6) | 42 (15.8) | 70 (37.6) | 48 (20.7) | 233 (44.2) | 11 (37.9) | |||||

| Uninsured | 111 (9.0) | 36 (13.5) | 31 (16.7) | 21 (9.1) | 19 (3.6) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| Prefer not to answer | 68 (5.5) | 37 (13.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0 | 21 (4.0) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| Internet accessb | |||||||||||

| Internet access at home | 881 (71.0) | 141 (53.0) | 115 (61.8) | 176 (75.9) | 430 (81.6) | 19 (65.5) | |||||

| Desktop | 855 (69.0) | 132 (49.6) | 115 (61.8) | 172 (74.1) | 418 (79.3) | 18 (62.1) | |||||

| Mobile device | 677 (54.6) | 95 (35.7) | 77 (41.4) | 103 (44.4) | 390 (74.0) | 12 (41.4) | |||||

| Tablet | 425 (34.3) | 38 (14.3) | 21 (11.3) | 75 (32.33) | 286 (54.3) | 5 (17.2) | |||||

| Years since diagnosis, median (IQR), y | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-2) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-3) | 0 (0-0) | |||||

| Anatomic site of cancer diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Breast | 208 (16.8) | 43 (16.2) | 18 (9.7) | 22 (9.5) | 119 (22.6) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| Gastrointestinal | 310 (25.0) | 59 (22.2) | 63 (33.8) | 57 (24.6) | 121 (23.0) | 10 (34.5) | |||||

| Genitourinary | 100 (8.1) | 33 (12.4) | 5 (2.7) | 16 (6.9) | 42 (8.0) | 4 (13.8) | |||||

| Gynecologic oncology | 30 (2.4) | 10 (3.8) | 0 | 5 (2.2) | 14 (2.7) | 1 (3.5) | |||||

| Lung | 420 (33.9) | 99 (37.1) | 74 (39.8) | 107 (46.1) | 132 (25.0) | 8 (27.5) | |||||

| Malignant hematologic | 80 (6.5) | 14 (5.3) | 8 (4.3) | 14 (6.0) | 44 (8.3) | 0 | |||||

| Other (soft tissue, brain, head and neck, thyroid, unknown primary, melanoma) | 92 (7.3) | 8 (3.0) | 18 (9.7) | 11 (4.7) | 55 (10.4) | 0 | |||||

| Cancer stage at diagnosis | |||||||||||

| 0 (In situ) | 28 (2.3) | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 22 (4.2) | 1 (3.5) | |||||

| 1 | 102 (8.2) | 13 (4.9) | 10 (5.4) | 18 (7.8) | 60 (11.4) | 1 (3.5) | |||||

| 2 | 106 (8.5) | 7 (2.6) | 6 (3.2) | 17 (7.3) | 73 (13.9) | 3 (10.3) | |||||

| 3 | 120 (9.7) | 18 (6.8) | 12 (6.5) | 18 (7.8) | 66 (12.5) | 6 (20.7) | |||||

| 4 | 198 (16.0) | 20 (7.5) | 10 (5.4) | 29 (12.5) | 129 (24.5) | 10 (34.5) | |||||

| Do not know cancer stage | 686 (55.3) | 204 (76.7) | 148 (79.6) | 149 (64.2) | 177 (33.6) | 8 (27.6) | |||||

| Cancer-directed treatmentc | |||||||||||

| Receiving active cancer-directed treatment | 852 (68.7) | 186 (69.9) | 125 (67.2) | 174 (75.0) | 347 (65.8) | 20 (69.0) | |||||

| Chemotherapy or immunotherapy | 756 (61.0) | 167 (62.8) | 99 (53.2) | 153 (65.9) | 320 (60.7) | 17 (58.6) | |||||

| Receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy treatment every 2-3 wk | 704 (93.1) | 158 (94.6) | 92 (92.9) | 146 (95.4) | 293 (91.6) | 15 (88.2) | |||||

| Receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy treatment every ≥4 wk | 52 (6.9) | 9 (5.4) | 7 (7.1) | 7 7 (4.6) | 27 (8.4) | 2 (11.8) | |||||

| Receiving oral chemotherapy, oral hormonal therapy, or endocrine therapy | 90 (7.3) | 17 (6.4) | 2 (1.1) | 7 (3.0) | 62 (11.8) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

| Radiotherapy | 284 (22.9) | 62 (23.3) | 61 (32.8) | 61 (26.3) | 90 (17.1) | 10 (34.5) | |||||

| Daily radiotherapy | 284 (100) | 62 (100) | 61 (100) | 61 (100) | 90 (100) | 10 (100) | |||||

| Surgery | 40 (3.2) | 5 (1.9) | 13 (7.0) | 9 (3.9) | 12 (2.3) | 1 (3.1) | |||||

| Participating in clinical trial | 106 (8.5) | 10 (3.8) | 6 (3.2) | 14 (6.0) | 74 (14.0) | 2 (6.9) | |||||

Defined race and ethnicity self-reported as American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or multiple races.

Multiselect question; the number of responses for this variable exceeds the number of participants and response percentages exceed 100%.

Number of responses and percentages are based on the number of participants who reported receiving that specific active cancer-directed treatment.

Most respondents were married (672 [54.2%]) and living with 1 or more household members (1146 [92.4%]). A higher proportion of Black respondents (230 of 266 [86.5%]), Asian respondents (166 of 186 [89.2%]), and Latinx respondents (188 of 232 [81.0%]) lived with a household member 18 years of age or younger; a higher proportion of Latinx respondents (175 of 232 [75.4%]) lived with a household member 65 years of age or older. Most respondents (1016 [81.9%]) reported annual household incomes of less than $100 000 US dollars, which was more common among Black respondents (252 of 266 [94.7%]). Most respondents had a bachelor’s degree or other professional degree (629 [50.7%]), which was more common among Asian respondents (126 of 186 [67.7%]).

Many respondents reported full-time employment (244 [19.7%]) or part-time employment (56 [4.5%]); a higher proportion of Black respondents were unemployed (106 of 266 [39.8%]). Most respondents had insurance (1110 [89.5%]). A higher proportion of Latinx respondents had private insurance or dual insurance coverage (176 of 232 [75.9%]). Most respondents had home internet access (894 [72.1%]), which was most common among White respondents (434 of 527 [82.4%]).

Clinical Characteristics

The median time to cancer diagnosis was 0 years (IQR, 0-3 years). Lung cancer was the most common diagnosis (420 [33.9%]) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Most respondents (686 [55.3%]) did not know their cancer stage at diagnosis, 852 (68.7%) reported receiving cancer-directed therapy, 756 (61.0%) reported receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy, 284 (22.9%) reported receiving radiotherapy, and 64 (5.2%) were scheduled for surgery. Of the 756 respondents receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy, 696 (92.1%) reported undergoing treatment every 2 to 3 weeks, and of the 284 respondents receiving radiotherapy, 284 (100.0%) reported undergoing treatment daily. A higher proportion of White respondents were enrolled in a clinical trial (104 of 527 [19.7%]).

Modifications in Care Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

A higher proportion of Black respondents (201 of 266 [75.6%]), Latinx respondents (186 of 232 [80.2%]), and respondents of other race or ethnicity (22 of 29 [75.9%]) experienced modifications in care, including delayed clinic visits, laboratory tests, and imaging and a change in location of care compared with White participants (301 of 527 [57.1%]) (Table 2). A higher proportion of Black respondents (197 of 201 [98.0%]) than White respondents (253 of 301 [84.1%]) who experienced modifications in care reported that the modifications were requested by the clinic or physician.

Table 2. Modifications in Care Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the US From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021.

| Variable | Participants, No./total No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1240) | African American or Black (n = 266) | Asian (n=186) | Hispanic or Latinx (n = 232) | White (n = 527) | Other (n = 29)a | |

| Modification in care, No. (%) | ||||||

| None | 434 (35.0) | 65 (24.4) | 90 (48.4) | 46 (19.8) | 226 (42.9) | 7 (24.1) |

| ≥1 | 806 (65.0) | 201 (75.6) | 96 (51.6) | 186 (80.2) | 301 (57.1) | 22 (75.9) |

| Type of modification in careb | ||||||

| Delay or cancellation of follow-up clinic visit | 615/806 (76.3) | 193/201 (96.0) | 87/96 (90.6) | 117/186 (62.9) | 196/301 (65.1) | 22/22 (100.0) |

| Delay or cancellation of laboratory visit | 554/806 (68.7) | 192/201 (95.5) | 87/96 (90.6) | 105/186 (56.4) | 148/301 (49.2) | 22/22 (100.0) |

| Delay or cancellation of imaging | 495/806 (61.4) | 120/201 (59.7) | 75/96 (78.1) | 106/186 (57.0) | 178/301 (59.1) | 16/22 (80.7) |

| Change in treatment schedule | 70/806 (8.7) | 28/201 (13.9) | 10/96 (10.4) | 14/186 (7.5) | 16/301 (5.3) | 2/22 (9.1) |

| New medication | 46/806 (5.7) | 12/201 (6.0) | 6/96 (6.3) | 9/186 (4.8) | 18/301 (6.0) | 1/22 (4.5) |

| Location of care change | 44/806 (5.5) | 16/201 (8.0) | 3/96 (3.1) | 11/186 (5.9) | 9/301 (3.0) | 5/22 (22.7) |

| Reason for modification in care | ||||||

| Requested by clinic or physician | 737/806 (91.4) | 197/201 (98.0) | 93/96 (96.9) | 177/186 (95.2) | 253/301 (84.1) | 17/22 (77.3) |

| Do not know | 18/806 (2.2) | 1/201 (0.5) | 0 | 6/186 (3.2) | 8/301 (2.7) | 3/22 (13.6) |

| Self-requested | 51/806 (6.3) | 3/201 (1.5) | 3/96 (3.1) | 3/186 (1.6) | 40/301 (13.3) | 2/22 (9.1) |

Defined race and ethnicity self-reported as American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or multiple races.

Multiselect question; response percentages for each option (ie, specific type of modification) when summed will exceed 100%.

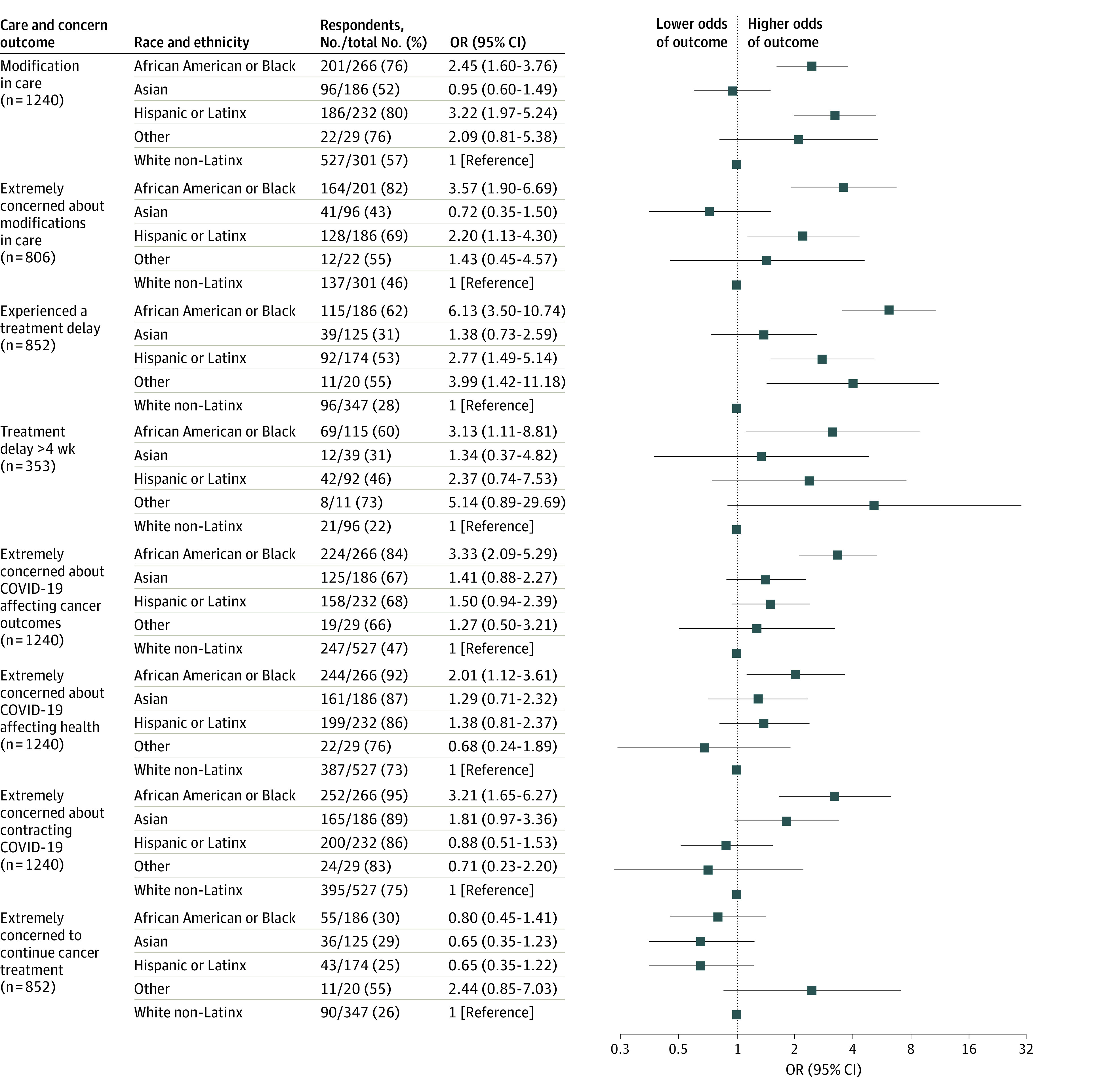

Compared with White respondents, Black respondents (OR, 2.45 [95% CI, 1.60-3.76]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 3.22 [95% CI, 1.97-5.24]) had greater odds of experiencing modifications in care and greater odds of reporting extreme concerns that the modifications would worsen their cancer outcomes (Black respondents: OR, 3.57 [95% CI, 1.90-6.69]; Latinx respondents: OR, 2.20 [95% CI 1.13-4.30]) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Modifications in Cancer Care, Treatment Delays, and Concerns Regarding Health by Race and Ethnicity.

The reference group for all comparisons is White non-Latinx respondents. Models were adjusted for a priori selected sociodemographic (gender identity, age, educational level, income, insurance status, and place of residence) and clinical variables (cancer diagnosis and stage). The other race category comprises American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and respondents of multiple races. OR indicates odds ratio.

Among those receiving cancer-directed treatment, Black respondents (OR, 6.13 [95% CI, 3.50-10.74]), Latinx respondents (OR, 2.77 [95% CI, 1.49-5.14]), and respondents of other race or ethnicity (OR, 3.99 [95% CI, 1.42-11.18]) had greater odds of experiencing involuntary treatment delays (Figure 1). Compared with White respondents, Black respondents had greater odds of experiencing treatment delays that exceeded 4 weeks (OR, 3.13 [95% CI, 1.11-8.81]) or experiencing indefinite treatment cancellation (OR, 2.15 [95% CI, 1.52-2.78]).

Concerns Regarding Health Outcomes

Compared with White respondents, Black respondents had greater odds of extreme concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic would affect cancer outcomes (OR, 3.33 [95% CI, 2.09-5.29]) and other health outcomes (OR, 2.01 [95% CI, 1.12-3.61]) as well as greater odds of extreme concerns about contracting SARS-CoV-2 (OR, 3.21 [95% CI, 1.65-6.27]) (Figure 1). There were no differences by race and ethnicity in the odds of concerns for continuing cancer treatment.

Experiences and Concerns Regarding Adverse Social and Economic Effects

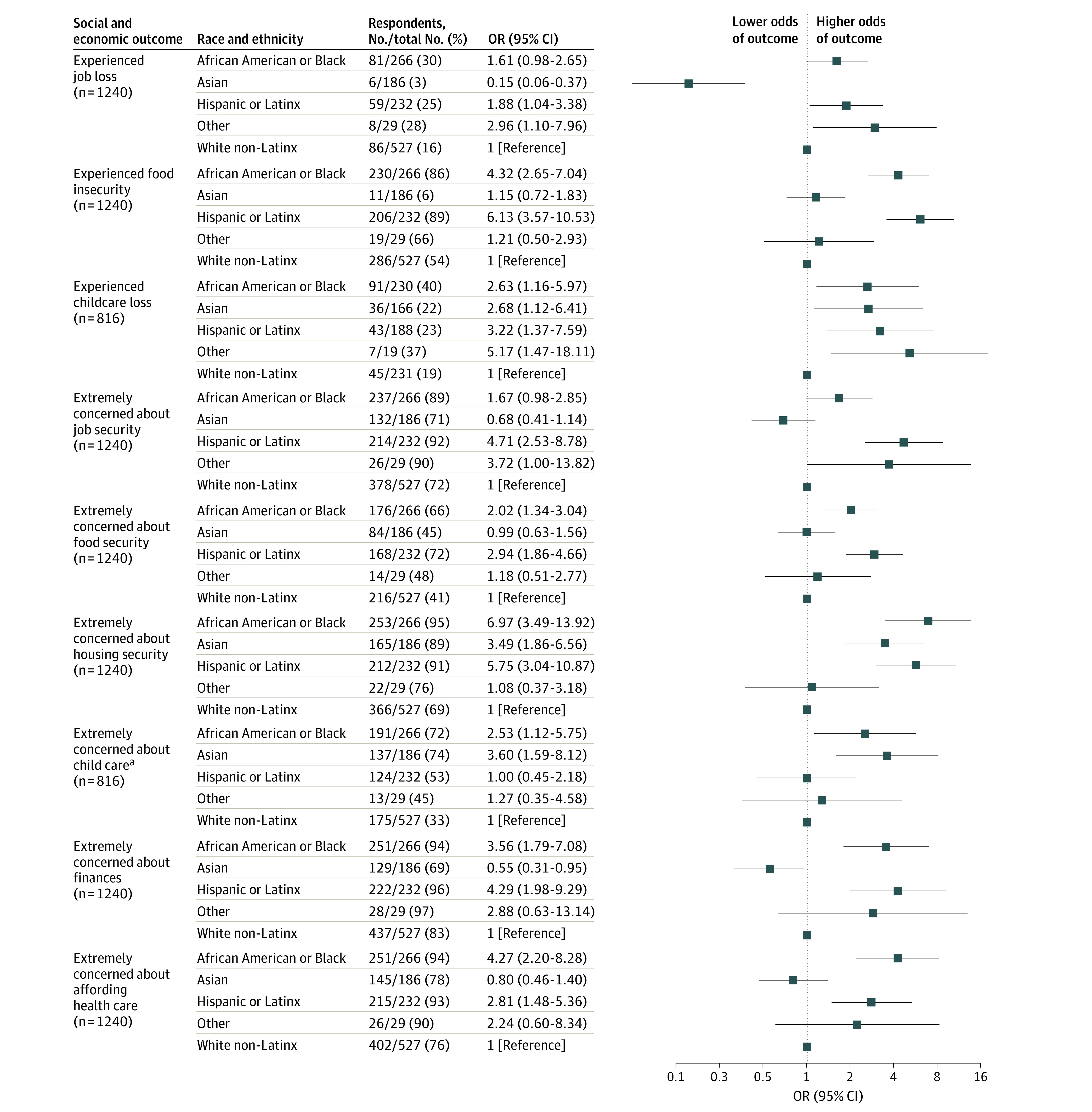

Compared with White respondents, Latinx respondents (OR, 1.88 [95% CI, 1.04-3.38) and respondents of other race or ethnicity (OR, 2.96 [95% CI, 1.10-7.96]) had greater odds of losing their job (Figure 2). Black respondents (OR, 4.32 [95% CI, 2.65-7.04]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 6.13 [95% CI, 3.57-10.53]) had greater odds than White respondents of food insecurity. Among respondents with children, all non-White groups had greater odds than White respondents of childcare loss (Black respondents: OR, 2.63 [95% CI, 1.16-5.97]; Asian respondents: OR, 2.68 [95% CI, 1.12-6.41]; Latinx respondents: OR, 3.22 [95% CI, 1.37-7.59]; and respondents of other race or ethnicity: OR, 5.17 [95% CI, 1.47-18.11]).

Figure 2. Experiences and Concerns Regarding Adverse Social and Economic Effects by Race and Ethnicity.

The reference group for all comparisons is White non-Latinx respondents. Models were adjusted for a priori selected sociodemographic (gender identity, age, educational level, income, insurance status, and place of residence) and clinical variables (cancer diagnosis and stage). The other race category comprises American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and respondents of multiple races. OR indicates odds ratio.

aIn the model assessing concerns about child care, 1 iteration of the multiple imputation for unknown cancer stage generated a structural positivity violation in which there were no cases among stage 0. This imputation was excluded, and the results comprise 99 iterations.

Extreme Concerns Regarding Adverse Social and Economic Effects

Latinx respondents had greater odds than White respondents of extreme concerns regarding job security (OR, 4.71 [95% CI, 2.53-8.78]) (Figure 2). Black respondents (OR, 2.02 [95% CI, 1.34-3.04]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 2.94 [95% CI, 1.86-4.66]) had greater odds than White respondents of extreme concerns regarding food security. Black respondents (OR, 6.97 [95% CI, 3.49-13.92]), Asian respondents (OR, 3.49 [95% CI, 1.86-6.56]), and Latinx respondents (OR, 5.75 [95% CI, 3.04-10.87]) had greater odds than White respondents of extreme concerns regarding housing security. Among those with children, Black respondents (OR, 2.53 [95% CI, 1.12-5.75]) and Asian respondents (OR, 3.60 [95% CI, 1.59-8.12]) had greater odds than White respondents of extreme concerns regarding child care. Black respondents (OR, 3.56 [95% CI, 1.79-7.08]) and Latinx respondents (OR, 4.29 [95% CI, 1.98-9.29]) had greater odds than White respondents of extreme concerns regarding overall finances, as well as affordability of health care (Black respondents: OR, 4.27 [95% CI, 2.20-8.28]; Latinx respondents OR, 2.81 [95% CI, 1.48-5.36]).

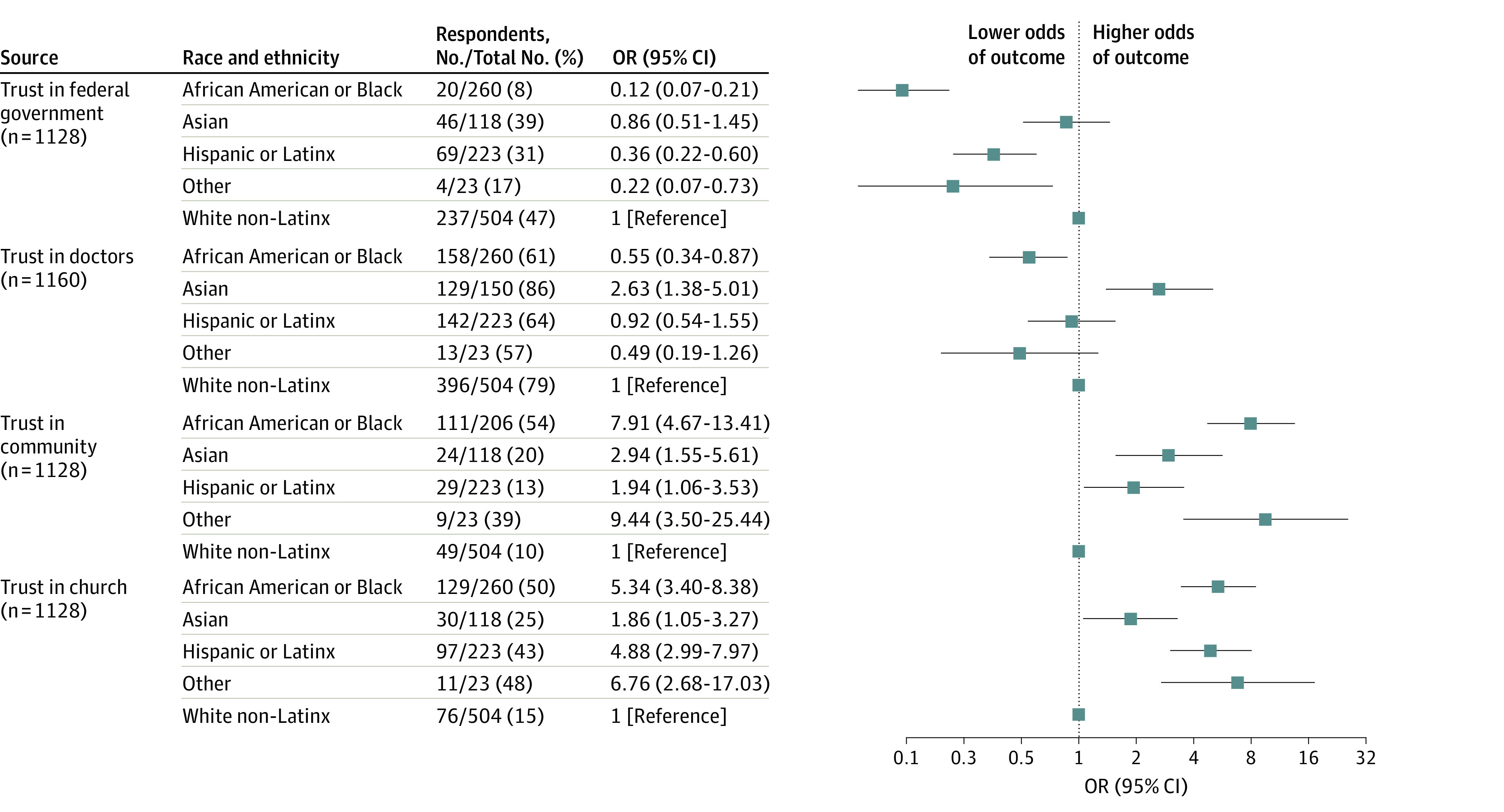

Trust in Sources of COVID-19 Information

Black respondents (OR, 0.12 [95% CI, 0.07-0.21]), Latinx respondents (OR, 0.36 [95% CI, 0.22-0.60]), and respondents of other race or ethnicity (OR, 0.22 [95% CI, 0.07-0.73]) had lower odds of trust than White respondents in the sources of COVID-19 information from the federal government (Figure 3). Compared with White respondents, Black respondents had lower odds of trust in physicians for COVID-19 information (OR, 0.55 [95% CI, 0.34-0.87]), and Asian respondents had higher odds of trust in physicians for COVID-19 information (OR, 2.63 [95% CI, 1.38-5.01]). Compared with White respondents, all non-White respondents had greater odds of trust in their community for COVID-19 information (Black respondents: OR, 7.91 [95% CI, 4.67-13.41]; Asian respondents: OR, 2.94 [95% CI, 1.55-5.61]; Latinx respondents: OR, 1.94 [95% CI, 1.06-3.53]; and respondents of other race or ethnicity: OR, 9.44 [95% CI, 3.50-25.44]) and greater odds of trust in church for COVID-19 information (Black respondents: OR, 5.34 [95% CI, 3.40-8.38]; Asian respondents: OR, 1.86 [95% CI,1.05-3.27]; Latinx respondents: OR, 4.88 [95% CI, 2.99-7.97]; and respondents of other race or ethnicity: OR, 6.76 [95% CI, 2.68-17.03]).

Figure 3. Trust in Sources for COVID-19 Information by Race and Ethnicity.

The reference group for all comparisons is White non-Latinx respondents. Models were adjusted for a priori selected sociodemographic (gender identity, age, educational level, income, insurance status, and place of residence) and clinical variables (cancer diagnosis and stage). The other race category comprises American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and respondents of multiple races. OR indicates odds ratio.

Sensitivity Analyses

Black respondents had 68% lower odds of knowing their cancer stage than White respondents (OR, 0.32 [95% CI, 0.21-0.49]), and Latinx respondents had 47% lower odds of knowing their cancer stage than White respondents (OR 0.53 [95% CI, 0.36-0.76]). In a sensitivity analysis in which unknown cancer stage was coded as a separate category within the cancer stage, ORs were similar in direction but varied in magnitude compared with those of the primary analysis (eTables 2-6 in the Supplement). Odds ratios for the complete-case analyses were consistent with the primary analysis; however, the large 95% CIs reflect the limited power.

Discussion

In this survey study of US adults with cancer, compared with White respondents, Black and Latinx respondents had 3 times the odds of experiencing modifications in their cancer care and extensive cancer treatment delays and greater odds of adverse social and economic effects and concerns regarding future adverse social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Owing to a combination of structural, economic, and socioenvironmental factors associated with systemic racism, prepandemic disparities persist in access to and timely receipt of cancer care among Black and Latinx adults. The COVID-19 pandemic heightened national awareness of structural barriers, including inadequacies in the health care system, that are associated with disparities in cancer care delivery. In this study, similar to 2 prior single-institution studies among patients with breast and prostate cancer,16,17 Black and Latinx adults experienced not only more delays but 6 times and nearly 3 times the odds, respectively, of cancer treatment delays that exceeded 4 weeks compared with White adults. The findings in this study, comprising mostly participants receiving treatment every 2 to 3 weeks and/or daily radiotherapy, suggest that 1 or more courses (or cycles) of treatment were delayed or canceled indefinitely. The long-term effects of 4 weeks’ or more delay on cancer outcomes remains unknown, yet in 1 meta-analysis, each month that cancer treatment was delayed was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of death.25 Although it is possible that delays in care may have been associated with fear of seeking care during the pandemic, there were no differences in concerns regarding continuation of cancer treatment by race and ethnicity.

Implicit bias and systemic racism have impaired educational, employment, and housing opportunities for Black adults for decades. These inequitable impairments are associated with prepandemic disparities, in which Black adults had half the access to health care, more food insecurity, and more poverty than White adults.10,26,27,28 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated these preexisting disparities. Between March and April 2020, for example, unemployment rates tripled and were disproportionately higher among Black and Latinx adults compared with adults of other races and ethnicities.15,29,30 In this study, conducted more than 4 months later, Black and Latinx adults experienced disparate adverse social and economic effects, such as unemployment among Latinx adults and food insecurity among both Black and Latinx adults.31,32,33,34,35

Although worsening mental and emotional health among patients with cancer has been described,36,37 in this study, Black and Latinx adults had greater odds than White non-Latinx adults of reporting extreme concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic and its associated delays in care would worsen their cancer outcomes. In contrast to results previously reported by survivors of breast cancer, which show no disparities in concerns regarding health outcomes by race and ethnicity,38 this study included participants with all cancer diagnoses, most of whom were undergoing active cancer treatment at the time of the survey. Black and Latinx adults also had greater odds of extreme concerns regarding future adverse social and economic effects, including food insecurity, housing insecurity, overall financial instability, and unaffordability of cancer care. These findings further support the worsening health and well-being of Black and Latinx adults during the ongoing pandemic.39

Trust is an essential component associated with an individual’s understanding of information and willingness to act,40,41 and it varies by race and ethnicity.42,43 In this study, consistent with others,42 Black and Latinx adults had less trust in the federal government, and Black adults had less trust in physicians for COVID-19 information. Adults from non-White groups represented in this study had greater odds of trust than White adults in community and church or faith-based organizations for COVID-19 information. Increased vaccination rates among Black adults through efforts led predominantly by community and church or faith-based organizations44 support the importance of partnering with sources of trust to improve health outcomes for individual groups. These findings should be explored as opportunities to overcome structural factors associated with longstanding cancer disparities.

Limitations

Our study had some limitations. The response rate could be an overestimation because it was calculated among those who directly received the survey link and not among those who may have seen the survey on social media. Individuals may have responded if they had a negative experience exacerbated by the pandemic, resulting in recall bias that may affect our results. Selection bias due to online survey access may have restricted participation to adults with internet access. Respondents had a high educational level, possibly underestimating results among populations with a lower educational level. The low number of self-identified Native Hawaiian, Alaska Native, and American Indian participants prevented statistical analysis of these groups in distinct categories. Our pooled associations (ie, the other race and ethnicity category) may not be the same for each of these groups.

The date of cancer diagnosis was not an inclusion criterion. Therefore, some respondents may have been outside the time period of treatment and might not have experienced modifications in cancer care. However, the median time of diagnosis was less than 1 year, and most participants reported receiving active cancer treatment at the time of the survey. Because we did not conduct a prepandemic and postpandemic evaluation, our results cannot discern whether the disparities reported were worse than those before the pandemic. Delays in care, such as those reported in this study, were due to a complex interplay between cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, treatment, and local COVID-19 infection rates. It is possible, therefore, that inaccurate self-reported cancer diagnosis and stage may have resulted in misclassifications that may have affected our results. Studies show that Black and Latinx adults have more advanced cancer stages at diagnosis than any other racial and ethnic group.45,46 In this study, however, a high proportion of respondents did not know their cancer stage, which was differential by race and ethnicity, with Black and Latinx adults having lower odds of knowing their cancer stage than White non-Latinx adults. In our primary analyses, we imputed unknown cancer stages, given studies that show that cancer stage could be missing at random, conditional on race, gender identity, age, income, insurance, and educational level,47,48,49 and we included the other clinical variables in the multiple imputation models.50,51,52,53,54 In sensitivity analyses, we analyzed unknown cancer stage as a distinct value, and we also conducted a complete-case analysis among participants who reported a known cancer stage. Although the magnitude of the ORs in these analyses varied, the direction of the association was consistent. However, because it is impossible to ascertain whether data are missing at random, our results, including multiple imputed cancer stage for unknown values, should be interpreted within this limitation.

Conclusions

In this survey study of US adults with cancer, Black and Latinx adults experienced extensive cancer care disparities, including greater delays in cancer treatment, adverse social and economic effects, and concerns regarding future adverse social and economic effects, compared with White adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urgent efforts are needed to address these disparities among Black and Latinx adults with cancer.

eFigure. Flow Chart of Survey Population and Respondents in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 1. Detailed Anatomic Site of Cancer Diagnoses of the Study Participants by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analysis of Modifications in Cancer Care, Concern, and Treatment Delays by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis for Concern Regarding Health Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Social and Economic Impacts by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis for Concern Regarding Social and Economic Impacts by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis for Sources of Trust by Race and Ethnicity for COVID-19 Information in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eAppendix. Survey Invitation and Survey

References

- 1.DeGroff A, Miller J, Sharma K, et al. COVID-19 impact on screening test volume through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer early detection program, January-June 2020, in the United States. Prev Med. 2021;151:106559. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVIDSurg Collaborative . Effect of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on planned cancer surgery for 15 tumour types in 61 countries: an international, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(11):1507-1517. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00493-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MI, Ma Y, Mitchell B, Rhoads KF. How do differences in treatment impact racial and ethnic disparities in acute myeloid leukemia? Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(2):344-349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhoads KF, Patel MI, Ma Y, Schmidt LA. How do integrated health care systems address racial and ethnic disparities in colon cancer? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):854-860. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.8642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(5):334-357. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Action Network, American Cancer Society . Cancer disparities: a chartbook. Published 2018. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.fightcancer.org/sites/default/files/National%20Documents/Disparities-in-Cancer-Chartbook.pdf

- 8.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2019-2021. Published 2019. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans/cancer-facts-and-figures-for-african-americans-2019-2021.pdf

- 9.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768-773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19—a tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(10):1531-1532. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeng-Gyasi S, Oppong B, Paskett ED, Lustberg M. Purposeful surgical delay and the coronavirus pandemic: how will Black breast cancer patients fare? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;182(3):527-530. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05740-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Published 2021. Accessed August 11, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

- 14.Shiels MS, Haque AT, Haozous EA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, March to December 2020. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(12):1693-1699. doi: 10.7326/M21-2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Labor force statistics from the current population survey: E-13: employed persons by sex, occupation, class of worker, full- or part-time status, and race. Published 2020. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e13.htm

- 16.Bernstein AN, Talwar R, Handorf E, et al. Assessment of prostate cancer treatment among black and white patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):1467-1473. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satish T, Raghunathan R, Prigoff JG, et al. Care delivery impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer care. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(8):e1215-e1224. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.01062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023-1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patt D, Gordan L, Diaz M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer care: how the pandemic is delaying cancer diagnosis and treatment for American seniors. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:1059-1071. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinmohamed AG, Visser O, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(6):750-751. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Association for Public Opinion Research . Standard definitions. Accessed April 1, 2022. https://www.aapor.org/Publications-Media/AAPOR-Journals/Standard-Definitions.aspx

- 22.Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM, et al. Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(2):315-332. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01038-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emerson MA, Golightly YM, Aiello AE, et al. Breast cancer treatment delays by socioeconomic and health care access latent classes in Black and White women. Cancer. 2020;126(22):4957-4966. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanna TP, King WD, Thibodeau S, et al. Mortality due to cancer treatment delay: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;371:m4087. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Brey C, Musu L, McFarland J, et al. Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups 2018. US Department of Education. Published 2019. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019038.pdf

- 27.Ryan CL, Bauman K. Educational attainment in the United States: 2015. Published March 2016. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf

- 28.Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch LN. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2019. US Census Bureau. Published 2020. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p60-271.pdf

- 29.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . Labor force statistics from the current population survey: E-14: employed Hispanic or Latino workers by sex, occupation, class of worker, full- or part-time status, and detailed ethnic group. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Published 2020. Accessed September 6, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/cpsee_e14.htm

- 30.Gemelas J, Davison J, Keltner C, Ing S. Inequities in employment by race, ethnicity, and sector during COVID-19. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(1):350-355. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-00963-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang SW, Kerlikowske K, Nápoles-Springer A, Posner SF, Sickles EA, Pérez-Stable EJ. Racial differences in timeliness of follow-up after abnormal screening mammography. Cancer. 1996;78(7):1395-1402. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carey P, Gjerdingen DK. Follow-up of abnormal Papanicolaou smears among women of different races. J Fam Pract. 1993;37(6):583-587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER, et al. Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):330-339. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fedewa SA, Edge SB, Stewart AK, Halpern MT, Marlow NM, Ward EM. Race and ethnicity are associated with delays in breast cancer treatment (2003-2006). J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):128-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borrayo EA, Scott KL, Drennen AR, MacDonald T, Nguyen J. Determinants of treatment delays among underserved Hispanics with lung and head and neck cancers. Cancer Control. 2016;23(4):390-400. doi: 10.1177/107327481602300410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandinelli L, Ornell F, von Diemen L, Kessler FHP. The sum of fears in cancer patients inside the context of the COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:557834. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.557834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam JY, Vidot DC, Camacho-Rivera M. Evaluating mental health–related symptoms among cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the COVID impact survey. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17(9):e1258-e1269. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamlish T, Papautsky EL. Differences in emotional distress among Black and White breast cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;9(2):576-580. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-00990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldmann E, Hagen D, Khoury EE, Owens M, Misra S, Thrul J. An examination of racial and ethnic disparities in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. South. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:471-478. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flowers P, Riddell J, Boydell N, Teal G, Coia N, McDaid L. What are mass media interventions made of? exploring the active content of interventions designed to increase HIV testing in gay men within a systematic review. Br J Health Psychol. 2019;24(3):704-737. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubin GJ, Amlôt R, Page L, Wessely S. Public perceptions, anxiety, and behaviour change in relation to the swine flu outbreak: cross sectional telephone survey. BMJ. 2009;339:b2651-b2651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Armstrong K, Ravenell KL, McMurphy S, Putt M. Racial/ethnic differences in physician distrust in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1283-1289. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson RV, Jackson EF. Is trust in others declining in America? an age–period–cohort analysis. Soc Sci Res. 2001;30(1):117-145. doi: 10.1006/ssre.2000.0692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdul-Mutakabbir JC, Casey S, Jews V, et al. A three-tiered approach to address barriers to COVID-19 vaccine delivery in the Black community. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(6):e749-e750. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00099-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hung MC, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, White A. Racial/ethnicity disparities in invasive breast cancer among younger and older women: an analysis using multiple measures of population health. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;45:112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pinheiro PS, Callahan KE, Siegel RL, et al. Cancer mortality in Hispanic ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):376-382. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merrill RM, Sloan A, Anderson AE, Ryker K. Unstaged cancer in the United States: a population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:402-402. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adams J, Audisio RA, White M, Forman D. Age-related variations in progression of cancer at diagnosis and completeness of cancer registry data. Surg Oncol. 2004;13(4):175-179. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worthington JL, Koroukian SM, Cooper GS. Examining the characteristics of unstaged colon and rectal cancer cases. Cancer Detect Prev. 2008;32(3):251-258. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bhaskaran K, Smeeth L. What is the difference between missing completely at random and missing at random? Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(4):1336-1339. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Kelly M. Multiple Imputation and Its Application. Carpenter, James and Kenward, Michael (2013). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. 345 pages, ISBN: 9780470740521. Biom J. 2014;56(2):352-353. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201300188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toutenburg H, Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Stat Hefte. 1990;31(1):180. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(12):1255-1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Chart of Survey Population and Respondents in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 1. Detailed Anatomic Site of Cancer Diagnoses of the Study Participants by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analysis of Modifications in Cancer Care, Concern, and Treatment Delays by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analysis for Concern Regarding Health Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analysis for Social and Economic Impacts by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analysis for Concern Regarding Social and Economic Impacts by Race and Ethnicity in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analysis for Sources of Trust by Race and Ethnicity for COVID-19 Information in a National Survey Study of 1240 Adults With Cancer in the United States From September 1, 2020, to January 12, 2021

eAppendix. Survey Invitation and Survey