Abstract

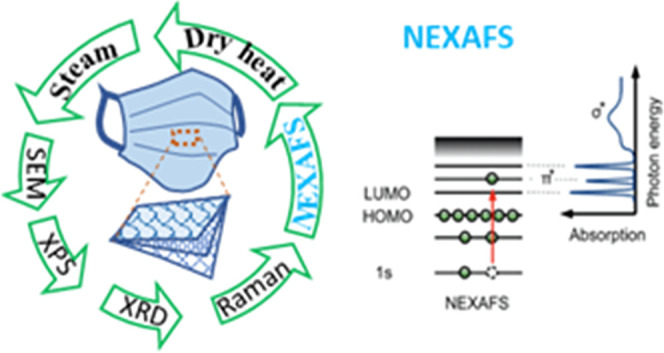

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in imminent shortages of personal protective equipment such as face masks. To address the shortage, new sterilization or decontamination procedures for masks are quickly being developed and employed. Dry heat and steam sterilization processes are easily scalable and allow treatment of large sample sizes, thus potentially presenting fast and efficient decontamination routes, which could significantly ease the rapidly increasing need for protective masks globally during a pandemic like COVID-19. In this study, a suite of structural and chemical characterization techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), contact angle, X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and Raman were utilized to probe the heat treatment impact on commercially available 3M 8210 N95 Particulate Respirator and VWR Advanced Protection surgical mask. Unique to this study is the use of the synchrotron-based In situ and Operando Soft X-ray Spectroscopy (IOS) beamline (23-ID-2) housed at the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory for near-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (NEXAFS).

Keywords: face mask materials, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, scanning electron microscopy, contact angle, X-ray diffraction, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy

Short abstract

The impact of heat recycling procedures on the structural integrity and surface chemistry of the N95 and surgical masks was assessed by a suite of structural and chemical characterization techniques.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused imminent local shortages of personal protective equipment such as face masks in hospitals, healthcare facilities, and individual households,1 necessitating reuse.2 Reuse of these masks can minimize waste, protect the environment, and help solve the current acute shortage of masks. To address the shortage, new sterilization or decontamination procedures for masks are quickly being developed and deployed.3 The main requirements for decontamination methods are that they should not (1) damage the structural integrity of the mask, (2) impact proper fitting, (3) impact filtration efficiency, or (4) leave residual chemicals.4 One such approach is the use of vaporous hydrogen peroxide,5 while other decontamination procedures include the use of ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI), moist heat or steam, exposure to ethylene oxide gas, as well as the use of liquid hydrogen peroxide.6

Soap and water have been shown to degrade the filtration efficiency of multiple N95 models, allowing for markedly increased penetration.7 Similarly, immersion within alcohol reagents such as ethanol, isopropanol, and bleach-containing solutions negatively affects N95 filtration efficiency7,8 and can result in electret degradation,9 discouraging use of household disinfectants to decontaminate face masks. The use of bleach-containing wipes can decontaminate some pathogens without damaging the mask material; however, associated health risks for asthmatic and sensitized users discourage their usage without an extended outgassing protocol prior to application.8,10,11 Promising applicable mask decontamination methods have included exposure to hydrogen peroxide vapor, UV-C radiation, and humid heat.12,13 Hydrogen peroxide vapor inactivates the novel SARS-CoV-2, among other viruses and resistant bacterial spores without damaging filter quality or strapping over multiple exposure cycles of some types of N95 respirators.14 However, hydrogen peroxide vapor treatment leads to some incompatibility with N95 face covering respirators that utilize cellulose as a component, negatively impacting the fit of some N95 models and may pose respiratory and skin irritation hazards without sufficient outgassing. UV-C radiation of greater than 1 J/cm2 inactivates viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2; however, if the radiation reaches the inner N95 layers, some damage at higher doses (≥120 J/cm2) can emerge, thus must be paired with additional chemical disinfection methods to decontaminate strappings.15−18

Both dry heat and steam sterilization processes are easily scalable and allow treatment of large sample sizes, thus potentially presenting fast and efficient decontamination routes,4 which could significantly ease the rapidly increasing need for protective masks globally during a pandemic like COVID-19. Both steam and dry heat treatment have long been recognized as efficient methods of virus inactivation by altering conformations of viral proteins involved in the attachment to and replication within host cells.19 Dry heat treatment (>65 °C) has previously been shown to inactivate SARS-CoV in suspension,20 while at a temperature of 102 °C for 60 min, infectious porcine respiratory coronavirus reduced by more than three orders of magnitude on surgical masks.21 A temperature of 70 °C was identified to inactivate SARS-CoV-2 in solution.22

Dry heat treatment at 70 °C for 1 h can ensure the decontamination of surgical face masks and N95 respirators while maintaining their filtering efficiency and shape for up to at least three rounds of treatment.23 A temperature of 100 °C was demonstrated to not significantly alter the filtration efficiency of N95 respirators within 20 cycles of treatment.24 It was reported by 3M that moist heat for 30 min at 60 °C, 80% relative humidity (RH) did not affect the filter performance of N95.25,26 Another report suggested that the surgical masks and N95 respirators retained their filtration efficacy even after being steamed in boiling water for 2 h.27 Steam heating of the N95 respirators in an autoclave for 15 min at 121 °C led to the death of almost 100% of Bacillus subtilis spores. Additionally, dry heat decontamination in a rice cooker for 3 min at temperatures of 149–164 °C was shown to have no negative impact on the performance of the respirator.28 However, if the temperature and treatment time are not carefully controlled, the mask fibers may be damaged, resulting in increases in the particle penetration, poorly fitting loose masks, and eventual decreases in the filtration efficiency, which could result in exposure to harmful byproducts during mask use.

Since both dry heat and steam sterilization could serve as promising strategies in the fight against mask shortages due to COVID-19, the focus of this study is to provide a more detailed understanding of the chemical properties and physical structure of mask materials before and after dry heat and steam sterilization processes. In this study, a suite of structural characterization techniques, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), contact angle, X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and Raman were utilized to probe the heat treatment impact on commercially available 3M 8210 N95 Particulate Respirator and VWR Advanced Protection surgical mask. SEM can provide morphological information regarding the thickness and three-dimensional (3D) network structure of the mask materials before and after heat treatment, while XRD and XPS can characterize the changes in crystallinity and surface chemical moieties upon the heat treatment. Contact angle measurements were performed to characterize the wetting properties of mask material surfaces toward artificial saliva solution, which was used to mimic interactions of respiratory droplets.29 A contact angle higher than 90° suggests low wettability and poor contact between the fluid and the surface, while a favorable wettability of the surface evinces a contact angle less than 90°, and the fluids will spread over a large area of the measured surface. Raman spectra were acquired to not only characterize the composition and crystallinity of individual layers in the N95 respirators and VWR surgical masks but also to monitor the conformational order/disorder (regularity) along the chain length of the polymer materials.

Unique to this study is the use of synchrotron-based In situ and Operando soft X-ray spectroscopy (IOS) beamline (23-ID-2) housed at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) at Brookhaven National Laboratory for near-edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) spectroscopy. To our best knowledge, this demonstrates the first use of the carbon K-edge NEXAFS to study the heat treatment impact on commercial mask materials. The spectra of the N95 and surgical mask materials were collected using two different detection modes: partial fluorescence yield (PFY) and total electron yield (TEY).30 The depth sensitivity of the XAS technique depends on the decay products that are collected, photons (“fluorescence yield” or FY), or electrons (“electron yield” or EY). The much smaller interaction cross section of X-rays in solids, as compared to electrons, makes the EY method much more surface sensitive than the FY method; the sampling depth d in EY mode is material dependent and typically smaller than 10 nm, while it is of the order of 100 nm for FY mode for photon energies smaller than 1 keV.31 By collecting both PFY and TEY Carbon K-edge spectra, the impact of heat treatment on the structural integrity of mask materials at different thickness levels can be assessed.

Experimental Methods

Heat Treatment Procedures

Dry Heat Treatment

Dry heat treatment of mask materials was carried out with a Binder oven (BF 56—UL) at 100 °C for four cycles, with 30 min for heating at 100 °C and 10 min for cooling per cycle at room temperature.

Steam Treatment

Steam treatment of mask materials was carried out using a Revolutionary Science Saniclave-Autoclave 200 with use of 4 cycles of the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI)/American National Standards Institute (ANSI) hospital sterilization protocol at 123 °C for each cycle with 30 min allotted for heating to 123 °C, for dwelling at 123 °C, and for cooling at room temperature.

Structural Characterizations

SEM Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were collected using a high-resolution SEM (JEOL 7600F) instrument. SEM images were acquired at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. A thin layer of Ag with 10 nm thickness was applied to the mask materials to reduce charging.

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

XRD measurements were performed using X-ray powder diffraction using a Rigaku SmartLab X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation and Bragg–Brentano focusing geometry.

XPS

XPS experiments were performed at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Both sample preparation and XPS measurements were performed in a lab-based ambient pressure photoelectron spectrometer32 by SPECS Surface Nano Analysis GmbH, with PHOIBOS 150 NAP hemispherical analyzer. The system has a sample preparation chamber and an analysis chamber separated by a gate valve; the base pressure in the analysis chamber is <10–9 mbar. A monochromated Al Kα (Ehν = 1486.6 eV) anode was used as the excitation source and was focused to a 300 μm × 300 μm spot. A pass energy of 20 eV was used for the O 1s and C 1s core-level regions. An electron flood gun was used to control charge build-up on the insulating samples. For each spectral region, a pass energy of 20 eV and step size of 0.1 eV were used, with a minimum of 10 scans per region. Data were analyzed using CasaXPS software. A Shirley background was subtracted prior to peak deconvolution. Fitting was performed using a symmetric line shape consisting of the product of Gaussian and Lorentzian functions.33 Typically, 70% Gaussian character was determined to result in best fits to the data.

Raman

Raman spectra of the pristine and treated mask materials were recorded on a HORIBA Scientific XploRA instrument with a 532 nm laser at 10% intensity using a 20× objective and a grating of 1200 lines/mm. The spectra were calibrated with a Si standard.

Contact Angle

The contact angle as a function of time was determined by use of a Kyowa DM-501 instrument and measured with the half-angle method. Each experiment was run for 10 duplicate trials, using 20 μL or 10 μL of artificial saliva (AS) solution, and data points were recorded every 100 ms for 10 min, and the volume change as a function of time was determined using the droplet profile and Kyowa FAMAS software.

Carbon K-Edge NEXAFS

C K-edge NEXAFS measurements were performed at the IOS (23-ID-2) beamline at NSLS-II. To avoid surface water contamination from the environment onto the mask materials, individual layers of the mask materials were secured onto the copper sample holder using indium foil, which was subsequently sealed in an Al pouch inside a humidity-controlled dry room before getting transferred to the ultra-high vacuum sample measurement chamber. Carbon K-edge NEXAFS spectra were recorded over a wide energy range from 280 to 380 eV using in a step scan (280–290 eV: 0.1 eV step, 290–300 eV: 0.2 eV step, 300–320 eV: 0.5 eV step, 320–380 eV: 1 eV step), with the incident beam at 90 degree. The spectra were acquired in total electron yield (TEY) through drain current measurement and partial fluorescence yield (PFY) (using a Vortex EM silicon drift detector) modes at multiple locations of each sample. The spectra were normalized by setting the flat low energy region (∼280 eV) to zero and the peak maxima to one to provide a qualitative assessment of spectra changes. Energy calibration was verified with respect to the C–C π* transition in the graphene oxide reference compound.34 XAS data were processed using Athena software packages.35

Results and Discussion

Morphology Evolution and Wetting Behaviors of N95 Respirators and VWR Surgical Masks after Heat Treatment

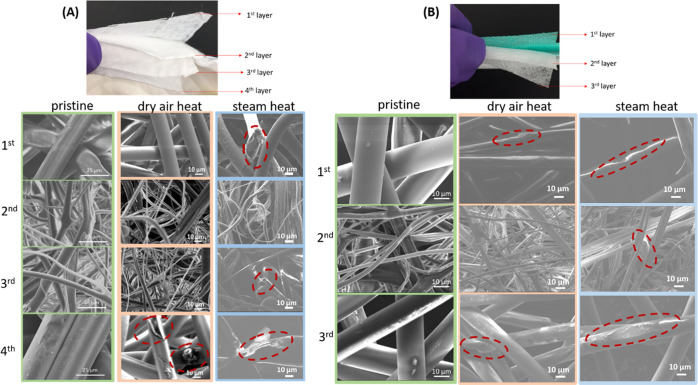

SEM images of the masks before and after heat treatment were acquired to investigate the morphology evolution (Figure 1). The pristine 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95 respirator was separated into four individual layers (Figure 1A). The 1st layer measures around 200 μm in thickness, which is composed of polyester1 microfibers, with a diameter of ∼20 μm. The 2nd layer is around 400 μm thick, containing polypropylene microfibers1 measuring ∼1–10 μm. The 3rd layer is around 200 μm in thickness, consisting of polypropylene microfibers1 with similar size shown in the second layer. The lofty nonwoven fibers can stack and create a 3D network that has a porosity of 90%, leading to very high air permeability.36 The 4th layer is around 200 μm in thickness and contains polyester microfibers,1 with a diameter around 30 μm. After the dry heat treatment at 100 °C, minimal damage was observed in layers 1–3, with only a few defects noted in the 4th layer, which indicated that the dry heat treatment does not induce significant structural degradation to the N95 masks. More severe damage (broken and etched fibers) was observed in the steam-treated samples with defects circled in the layers, suggesting a stronger structural degradation.

Figure 1.

SEM images of individual layers in pristine, dry heat, and steam-treated N95 respirators (A) and VWR surgical masks (B).

The pristine VWR surgical mask was separated into three layers (Figure 1B). The 1st layer and 3rd layer show a similar thickness of around 200 μm, composed of microfibers with a diameter of around 20 μm. The only difference is that the 1st layer has a green dye. The middle 2nd layer measures 100 μm in thickness with thinner microfibers in the range of 2–10 μm. All three layers are made of polypropylene microfibers. Both dry heat and steam heat treatments seem to induce surface damage in the 1st and 3rd layers, as indicated by the red circles, while for the middle 2nd layer, the steam treatment led to stronger damage.

The greater structural damage observed in the steam-treated N95 respirators and surgical masks in this study is consistent with previous literature, where most N95 respirator types with autoclave (steam) treatment appeared to have some physical damage to the overall structure and shape of the respirators and failed quantitative fit testing for multiple respirator types tested.37−39 Although autoclaving (i.e., steam at ∼121 °C and >15 psi) is a proven method of sterilization of most pathogens, it has been noted previously that moist heat can degrade filter efficiency in some cases, making it less effective for decontamination of used respirators.40

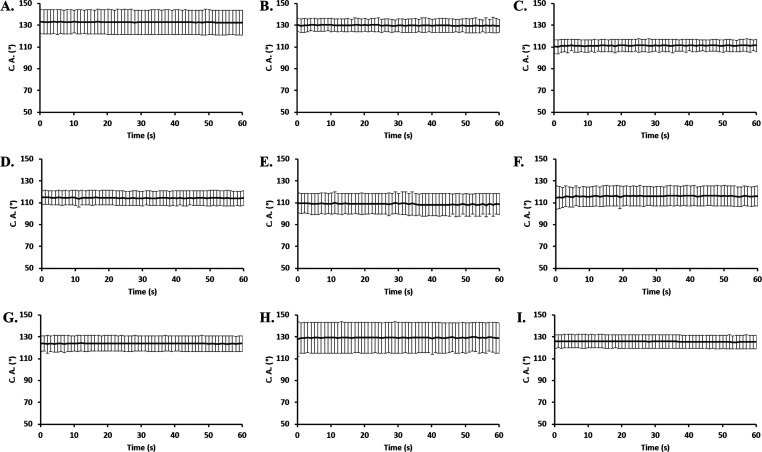

The artificial saliva contact angle and volume change as a function of time for the material layers of the 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95 respirators is shown in Figure 2. Figure 2A–C depicts the outside surface of the 1st layer of N95, which shows the contact angle at 133°, and the droplet volume did not show significant change in 60 s. Upon dry heat treatment, the contact angle decreased minutely to 130°. Steam treatment evinced the most pronounced change, reducing the contact angle to 110°, implying a sharp increase in surface adsorption to the artificial saliva droplet, indicating that steam treatment can potentially increase the adsorption of transmitted saliva from outside to the outermost layer of the N95 respirator, lowering the protection efficacy. The 2nd layer of N95, shown in Figure 2D–F, displayed a contact angle around 115° and did not show a significant change within 60 s, while the volume slightly decreased as a function of time. Upon dry heat treatment, the contact angle decreased minutely to 110°, implying an increase in surface adsorption to the artificial saliva droplet. Steam treatment, however, showed little change from the pristine sample, evincing an observed contact angle of 116°. The 3rd layer of N95 shown in Figure 2G–I displayed a contact angle around 124° and did not show a significant change in 60 s, while the volume slightly decreased as a function of time. Upon dry heat treatment, the contact angle increased to 129°, implying a decrease in surface adsorption to the artificial saliva droplet. Steam treatment, again, showed little change from the pristine sample, evincing an observed contact angle of 125°.

Figure 2.

Contact angle as a function of time for the 1st layer (A), heat-treated 1st layer (B), steam-treated 1st layer (C), 2nd layer (D), heat-treated 2nd layer (E), steam-treated 2nd layer (F), 3rd layer (G), heat-treated 3rd layer (H), and steam-treated 3rd layer (I) of 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95.

The contact angle and volume change as a function of time for the material layers of the VWR surgical mask is shown in Figure 3. Figure 3A–C displays the 1st layer of the VWR surgical mask, which shows the contact angle around 119° and does not show a significant change in 60 s. Both dry heat and steam treatments caused the contact angle to decrease minutely to 115° to show increased surface adsorption. The 2nd layer of the VWR surgical mask, shown in Figure 3D–F, displayed a contact angle around 134° and did not show significant change within 60 s, while the volume similarly remained constant. Only the dry heat treatment evinced a change to the observed contact angle, which reduced to 121° to imply increased surface adsorption. The 3rd layer of the VWR surgical mask shown in Figure 3G–I displayed a contact angle around 118° and did not show a significant change in 60 s. Both dry heat and steam treatments caused the contact angle to decrease minutely to 111° to show increased surface adsorption. Collectively, with respect to the VWR surgical mask, the steam and dry heat exposures served to increase the surface adsorption toward the artificial saliva or evoke no change at all.

Figure 3.

Contact angle and volume change as a function of time for the 1st layer (A), heat-treated 1st layer (B), steam-treated 1st layer (C), 2nd layer (D), heat-treated 2nd layer (E), steam-treated 2nd layer (F), 3rd layer (G), heat-treated 3rd layer (H), and steam-treated 3rd layer (I) of VWR Advanced Protection surgical mask.

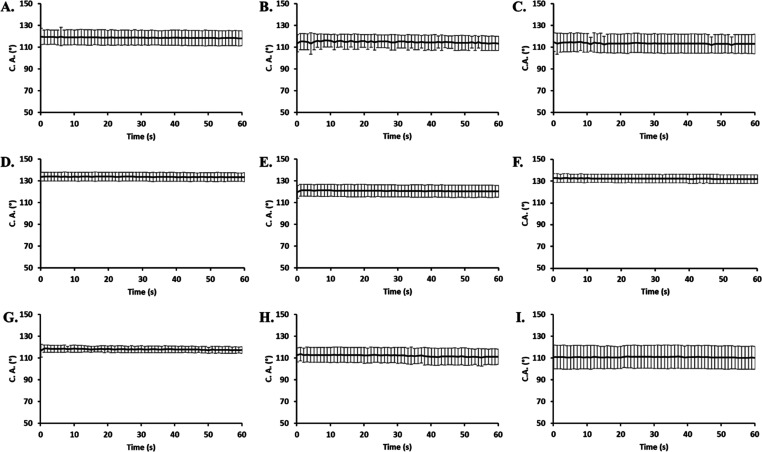

Bulk Crystallinity and Bond Evolution of N95 Respirators and VWR Surgical Masks after Heat Treatment

XRD characterization was used to identify the composition and crystallinity of each layer of mask materials. The XRD characterization of 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95 is shown in Figure 4A–D, including pristine, dry heat treatment, and steam treatment. The XRD patterns of the layer 1 and layer 4 indicated the semicrystalline feature, and as marked therein, the major diffraction patterns appear due to reflections from (010), (1̅10), and (100) planes of the polyester phase (PDF #50-2275), as shown in Figure 4A,D. The XRD patterns of layer 2 and layer 3 indicated the semicrystalline feature, and as marked therein, the major diffraction patterns appear due to reflections from (110), (045), (130), and (1̅31) planes of the polypropylene phase (PDF #50-2397), as shown in Figure 4B,C. The XRD pattern of the dry treatment sample did not show an obvious difference from the pristine samples, which indicates that the N95 has stable composition and crystalline structure under dry heat treatment. The XRD patterns of the steam treatment sample show a slight difference at each layer from pristine materials. As shown in Figure 4A,D, the (01̅1) peak disappears after steam treatment in layer 1 and layer 4, and the peak at (1̅11) separates from the peak (1̅10) after steam treatment in layer 1. The peak intensity increased after steam treatment in layer 2, indicating more crystallinity features after steam treatment (Figure 4B). In layer 3, the peak at (111) becomes more distinct after steam treatment (Figure 4C). The XRD characterization of each layer in the VWR surgical mask is shown in Figure 4E–G, including pristine, dry heat treatment, and steam treatment. The XRD patterns of layers 1–3 indicated the semicrystalline feature. Specifically, layer 2 (Figure 4F) is relatively more amorphous than layer 1 (Figure 4E) and layer 3 (Figure 4G). As marked therein, the major diffraction patterns appear due to reflections from (110), (045), (130), and (1̅31) planes of the monoclinic α-polypropylene phase (PDF #50-2397). The pristine layer 2 material has an obvious broadening of the (110) peak, which suggests the variation of fiber diameter with the fabric’s axis being (110).41 However, the peak intensity increased, and the peaks were sharper after dry heat and steam treatment, especially for layer 2 as shown in Figure 4F, indicating more crystalline features were observed after dry heat and steam treatment. The increased crystallinity of polymer fibers after steam treatment might increase the polymer hardness but decrease the elasticity, which could impact the fit and filtration efficiency of the treated mask.42

Figure 4.

XRD spectra of four layers in N95 respirators (A–D) and three layers in VWR surgical masks (E–G) before and after dry heat and steam heat treatments.

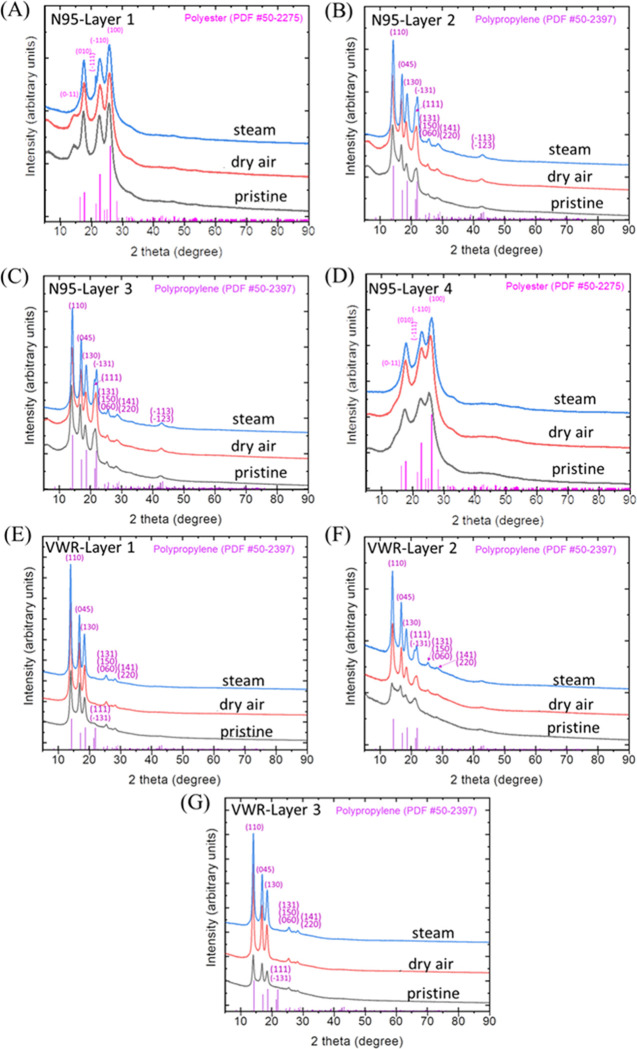

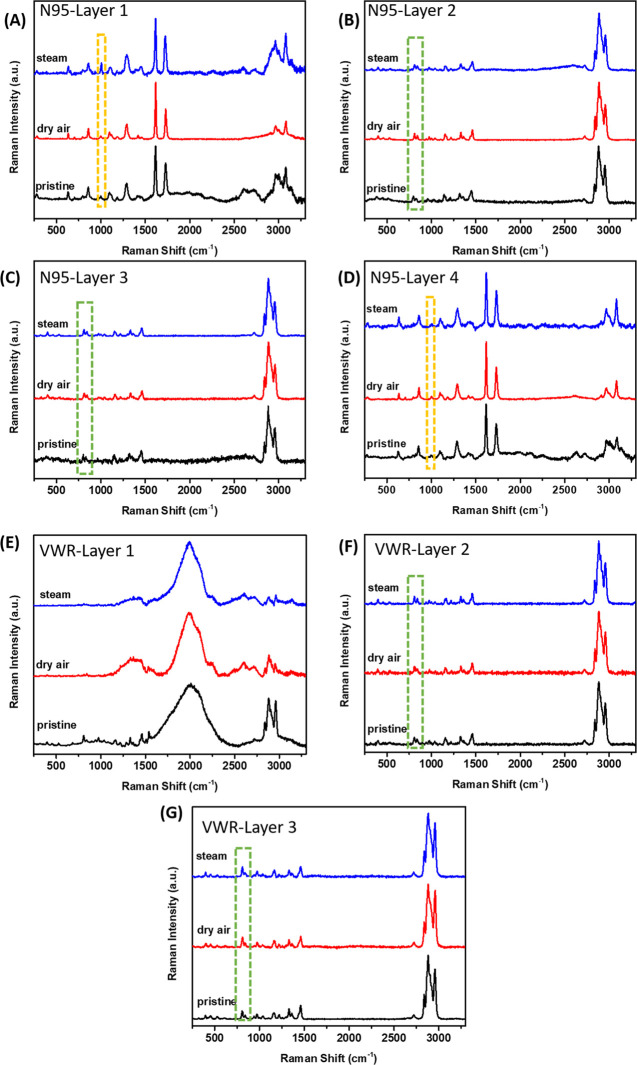

Raman spectra of mask materials not only indicate the composition and crystallinity of each layer but also are sensitive to the conformational order/disorder (regularity) along the chain length of polymer materials. Based on the acquired Raman spectra, layers 1 and 4 of N95 respirators can be assigned to polyester material (Figure 5A,D),43 as indicated by the strong C=C stretching band (ring deformation) at 1615 cm–1 and C=O stretching band at 1730 cm–1. A group of bands at 1115, 1094, and 998 cm–1 have been previously attributed to mixed modes of ring CH in-plane bending, glycol C–O stretching, COC and CCO bending, and C–C stretching of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET).44 A peak at 1002 cm–1 can be identified in all of the polyethylene (PE) mask materials, which was previously assigned to C–C and C–O stretching of the ethylene glycol group and only appears when the material is crystalline or semicrystalline, with a trans glycol conformation.45 The 1st layer of N95 shows higher intensity of this peak with narrow bandwidth than that in the 4th layer, which possibly suggests higher crystallinity of the polyester in the 1st layer. Overall, no significant differences of Raman spectra were observed in the bulk structure of layers 1 and 4 in N95 masks before and after heat treatment, suggesting the minimal changes in crystallinity and bond orientation of the outer layer and inner layer of 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95 are quite stable under heat treatment.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of four layers in N95 respirators (A–D) and three layers in VWR surgical masks (E–G) before and after dry heat and steam heat treatments.

Layers 2 and 3 of N95 (Figure 5B,C), and all three layers in the VWR surgical masks (Figure 5E–G), have spectra features that resemble polypropylene materials. It is noted that the 1st layer in the VWR surgical mask (Figure 5E) showed high fluorescence, as indicated by the broad peak features, possibly due to the dye used in this layer. The fluorescence became even more severe after the treatment, and no obvious polymer peaks can be discerned below 1500 cm–1, indicating some impact of heat on the 1st layer. The band at 1435 cm–1 has been assigned to the CH2 group deformation. The 972 cm–1 band has been assigned to the symmetry of the 31 helical structure. The broad asymmetric band observed at approximately 830 cm–1 apparently splits into two bands at 808 and 840 cm–1 upon crystallization. This indicates that the 830 cm–1 band is a fundamental frequency of the chemical repeat unit that is altered by the symmetry of the helical chain conformation due to inter-molecular coupling between adjacent groups.46,47 The 810 cm–1 band can be assigned to helical chains within the crystals, while a broader band at 840 cm–1 is assigned to chains in nonhelical conformation.48 The ratio of two bands at 810 and 840 cm–1 decreased after steam heat treatment in layers 2 and 3 in N95 (Figure 5B,C), suggesting the shorting of helical chain conformation of polypropylene after heat treatment.49 The VWR surgical mask’s 2nd layer Raman bands are broader and weaker than those in the 3rd layer, which potentially suggested lower crystallinity in this layer due to the narrower thickness of the fibers.50 The changes in the peak intensity and peak ratio of two bands at 810 and 840 cm–1 are more obvious in the 2nd layer in comparison with the 3rd layer, possibly suggesting more structural damage in the 2nd layer. Similar to the XRD observations in Figure 4B,C, the Raman peaks in layers 2 and 3 in the N95 respirators as well as layer 2 in the VWR surgical mask became sharper after the steam treatment, indicating improved crystallinity of the polymers in these layers. Overall, the Raman results suggested that there might be some level of shorting of helical chain conformation and potentially weaker mechanical strength in the 2nd and 3rd layers of the N95 respirators and the 2nd layer of the VWR surgical mask, while the 3rd layer shows the highest stability toward heat treatment.

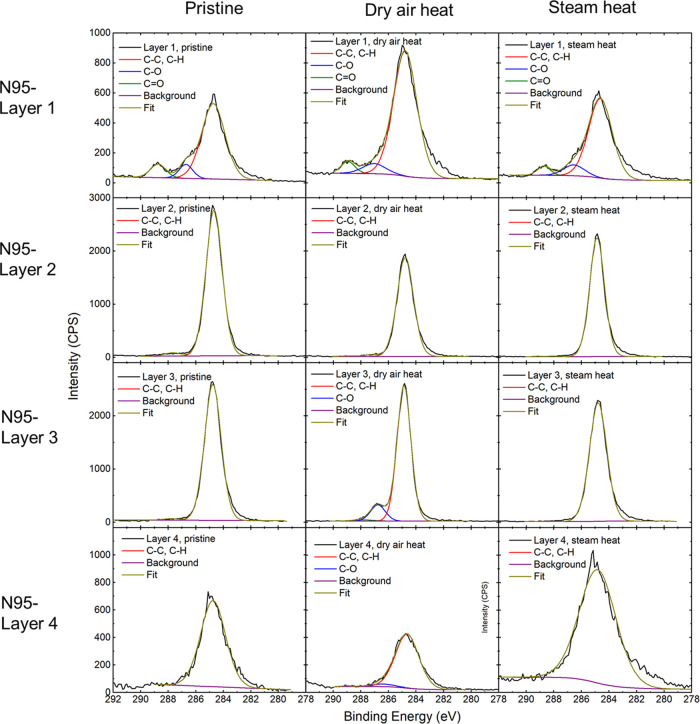

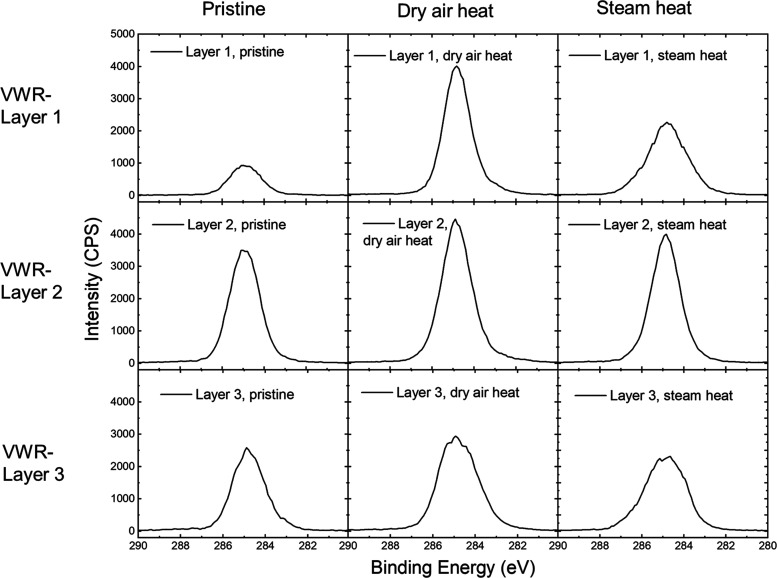

Changes in Surface Chemistry of N95 Respirators and VWR Surgical Masks after Heat Treatment

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to characterize the surface chemistry of the mask materials before and after heat treatments. The XPS spectra for C 1s and O 1s regions collected on the 3M Particulate Respirator 8210 N95 are shown in Figures 6 and 7, respectively. For the pristine material, C 1s spectra show that all four layers of the materials have a significant C–C/C–H binding component. For layer 1, additional peaks are also observed at ca. 286.5 eV and ca. 288 eV, assigned to C–O and C=O bonds, respectively. Some residual signal at the low B.E. side of the C 1s peak may be an artifact of charge compensation using the electron gun.51 Prominent carbon to oxygen bonding was also observed at ca. 532–533 eV in the O 1s spectra for layers 1 and 4. These spectra are consistent with these layers being comprised of polyester,52 in good agreement with the XRD results. Layers 2 and 3 exhibit primarily C–C/C–H bonding, consistent with polypropylene,53 which was also assigned from XRD indexing. A very low-intensity signal is observed in the O 1s spectra, possibly due to the absorption of molecular water.54 Because the O 1s spectra are slightly more surface sensitive than the C 1s spectra due to the lower kinetic energy of the O 1s photoelectrons, there could be some contribution from C–O and C=O that is not seen in the C 1s data. It is worth mentioning that there was a noticeable intensity increase after the steam treatment in the O 1s spectra of N95 layer 4, which possibly suggested that the steam treatment induced more physisorption of oxygenated species on the polymer fibers such as H2O and O2.

Figure 6.

C 1s XPS spectra of pristine, dry-heat-treated, and steam-treated N95 respirators.

Figure 7.

C 1s XPS spectra of pristine, dry-heat-treated, and steam-treated VWR surgical masks.

Figures 7 and S2 show the C 1s and O 1s XPS spectra of VWR surgical masks. For all three layers, primarily C–C/C–H bonding was observed, which is again consistent with the diffraction measurements that indicated polypropylene composition. No C–O bonding was observed in the C 1s region; however, low levels of adventitious oxygen were observed in the O 1s spectra, suggesting low levels of molecular water absorption.54 Treatment by dry or steam heat did not change the surface chemistry of the materials.

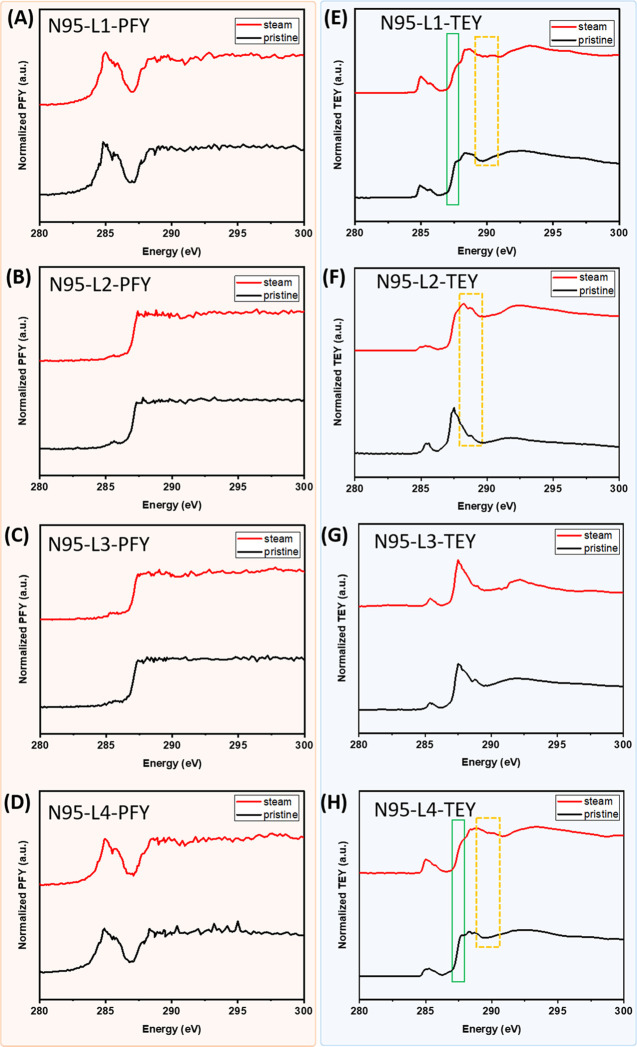

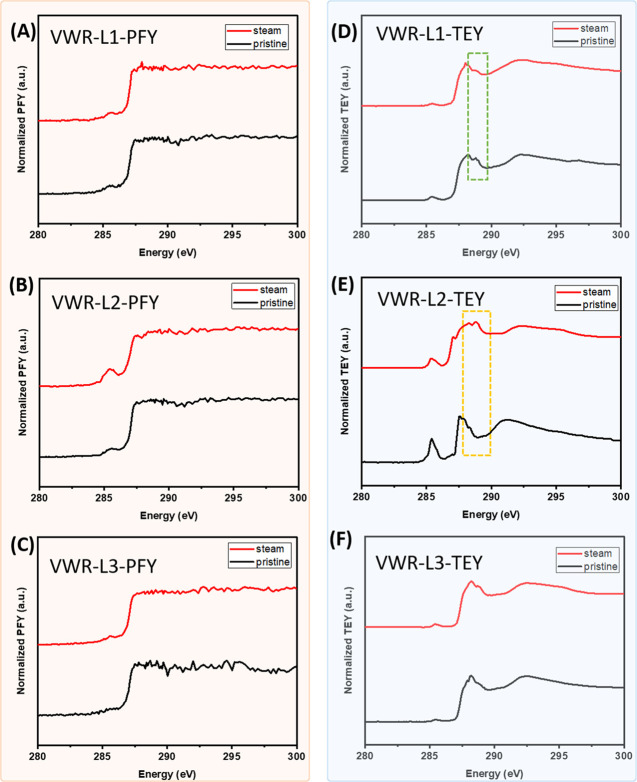

Carbon K-Edge NEXAFS

Since steam treatment demonstrated a higher level of structural change from SEM observations, the NEXAFS measurements were collected only on the pristine and steam-treated samples to investigate the change of surface structures of the mask materials.

In the 1st and 4th layers of N95 respirators containing polyester fibers, two sets of peaks at 284.8 eV (π*C=C excitations) and 288.2 eV (π*C=O transitions) are observed. Two subpeaks that are found in each set are due to conjugation across the terephthalic segment in the repeat unit, resulting in a splitting of the excited final state.55,56 The high noise observed above 290 eV in the PFY data are mainly due to the high level of X-ray absorption due to the thick layer of mask material, making detection of changes in the cross section no longer possible. In the PFY data (Figure 8A–D), no significant changes were observed before and after the steam treatment, similar to the observations in the XPS data. Interestingly, in the TEY data (Figure 8E,H), where more surface features were observed, an obvious decrease of the shoulder peak at 287.5 eV relative to the main peak at 288.2 eV (π*C=O transitions) was observed (green rectangles). The peak at 287.5 eV has been previously assigned to π*C=C/C=O transition in the C–R(ring) of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) polymer.57 The ratio change can possibly suggest heat-induced ring-opening reactions that lead to the formation of new carbonyl species. Additionally, despite the π*C=O peak broadening with new features appearing between 289 and 290 eV (yellow dashed box), the overall intensity relative to the π*C=C peak (284.8 eV) decreased. This could suggest that some of the ester groups of the terephthalic unit can be destroyed by the steam, resulting in CO and CO2 and benzoic acid ester radicals.58 The PFY data of the 2nd and 3rd layers of N95 containing polypropylene fibers (Figure 8B,C) showed noisy and dampened signals in the pristine material, which does not provide a useful assessment of the heat impact. In the TEY data (Figure 8F,G), the pristine material depicted a small peak around 285.0 eV, which is probably due to an additive or filler within these layers or the small amount of beam damage during sample measurement. The strong intensity peak located at 287.5 eV can be attributed to the C 1s to σ*C–H transition, and the broad feature around 292 eV corresponds to the σ*C–C bonds in the chain backbone.56 After steam treatment in the 2nd layer (Figure 8F), the main peak at σ*C–H intensity decreased, while the peak at 285 eV became broader, which suggested a possible decrease of C–H bonds and the formation of C=C bonds due to the degradation of the polymer. The main peak shifted to 288.3 eV with new π* features appearing at 288.8 eV (yellow dashed box), which possibly suggested a small amount of C=O functionalities during the degradation of polypropylene.34,59 In the 3rd layer TEY data (Figure 8G), no peak broadening of the main peaks corresponding to π* features were observed, indicating the damage might be less severe in the 3rd layer in comparison with the 2nd layer.

Figure 8.

C K-edge NEXAFS spectra of N95 layer 1–4 collected in PFY (A–D) and TEY (E–H) modes, respectively, where all spectra were normalized by setting the flat low energy region (∼280 eV) to zero and the peak maxima to one.

In the VWR surgical masks, the PFY data of all three layers (Figure 9A–C) showed noisy and dampened signals, which does not provide a useful assessment of the heat impact. In the TEY data, the peak located at 288.8 eV in the pristine layer 1 material decreased in intensity after the steam treatment (as indicated by the green dashed box), which could be attributed to the degradation of the green dye used in the 1st layer at the steam treatment (Figure 9D). In the 2nd layer TEY data (Figure 9E), the pristine fibers showed a major peak at 287.5 eV and 292 eV, corresponding to the σ*C–H and σ*C–C bonds, respectively. Upon steam treatment, new peaks at 287.0, 288.2, and 288.8 eV appeared (yellow dashed box), which can be attributed to the physisorption of O2 and H2O molecules to the polymers during the steam treatment, leading to symmetry breaking depending on bond strain in the chain backbone.59 No significant changes were observed in the TEY data of the 3rd layer (Figure 9F), indicating that this layer has good stability toward the steam treatment.

Figure 9.

C K-edge NEXAFS spectra of VWR surgical mask layer 1–3 collected in PFY (A–C) and TEY (D–F) modes, respectively, where all spectra were normalized by setting the flat low energy region (∼280 eV) to zero and the peak maxima to one.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a major shortage of N95-level facial respirators, which necessitates the effective recycling and reuse of masks. These critical shortages put the medical professionals at risk and result in a slower, effective response to the emerging crisis. In this work, we investigated the impact of facile and scalable heat treatment using both dry air and steam on the structural integrity and surface chemistry of the N95 respirators and VWR surgical masks. Although the treatment was not directly applied to face masks that had been exposed to the COVID-19 virus, our results still provide insights into how to select the proper treatment protocols that lead to the maximum effectiveness in disinfection with minimum material degradation, thus maintaining the functionality of the masks.

Although previous literature studies have suggested that both steam and dry heat treatment have been recognized as an efficient method of COVID-19 virus inactivation, via altering the conformation of viral proteins involved in the attachment to and replication within host cells, our results indicated that the dry air treatment led to less structural damage to the masks in comparison with the more rigorous steam heat treatment, which represents a promising disinfection protocol that may be applied to the recycling and reuse of facial masks. In terms of helical chain stability in individual layers in the two masks, the 3rd layer in VWR surgical masks seems to have a higher heat tolerance toward the treatment. Helical chain length in the 2nd and 3rd layers in the N95 respirators and the 2nd layer in the VWR surgical mask can be impacted by heat treatment, especially with steam, which might lead to changes in the mechanical strength of the material and will require caution when handling the heat treatment. NEXAFS results suggested that there might be physisorption of O2 and H2O molecules to the polymer backbone during the steam treatment, leading to symmetry breaking depending on bond strain, where new carbonyl-based species were present the 1st, 2nd, and 4th layers in the N95 respirators, and the 2nd layer of the VWR surgical mask after the steam treatment. Additionally, the dye in the 1st layer of the VWR surgical mask seemed to degrade drastically after the heat treatment, which might lead to negative impacts on the polymer fibers.

In summary, our SEM results suggested higher structural damage to the polymers using steam treatment, which can lead to poor fit and lower filtration efficiency. Contact angle measurements suggested increased adsorption of artificial saliva to the 1st layer of N95, especially after steam treatment, indicating the potential decreased protection of N95 from the transmitted saliva from outside. The increased crystallinity of polymer fibers after steam treatment noted from XRD might increase the polymer hardness but decrease the elasticity, which might impact the fit and filtration efficiency of the treated mask.42 The shorting of helical chain conformation after steam treatment might lead to the weaker mechanical strength of the polymers. The goal herein was to introduce new approaches for the characterization of pristine and treated mask materials. Future studies will correlate the physical, chemical, and structural property changes of mask treatment with quantitative mask fit tests.

Acknowledgments

The characterization studies were supported by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on the response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. This research used resources of the In situ and Operando Soft X-ray Spectroscopy (IOS) beamline (23-ID-2) at the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facilities operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. Electron microscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy data were collected at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, which is a U.S. DOE Office of Science Facility, at Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. C.A.S. acknowledges support from the NIH Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award and New York Consortium for the Advancement of Postdoctoral Scholars (IRACDA-NYCAPS) Award K12-GM102778. E.S.T. acknowledges support as the William and Jane Knapp Chair in Energy and the Environment.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c04530.

O 1s XPS spectra of pristine, dry-heat-treated, and steam-treated N95 and surgical masks (PDF)

Author Contributions

∇ S.Y. and C.A.S. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhao M.; Liao L.; Xiao W.; Yu X.; Wang H.; Wang Q.; Lin Y. L.; Kilinc-Balci F. S.; Price A.; Chu L.; Chu M. C.; Chu S.; Cui Y. Household Materials Selection for Homemade Cloth Face Coverings and Their Filtration Efficiency Enhancement with Triboelectric Charging. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 5544–5552. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson D. L. Collection Efficiency Comparison of N95 Respirators Saturated with Artificial Perspiration. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2020, 27, 299–307. 10.1021/acs.chas.0c00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah S.; Ullah A.; Lee J.; Jeong Y.; Hashmi M.; Zhu C.; Joo K. I.; Cha H. J.; Kim I. S. Reusability Comparison of Melt-Blown vs Nanofiber Face Mask Filters for Use in the Coronavirus Pandemic. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 7231–7241. 10.1021/acsanm.0c01562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmacharya M.; Kumar S.; Gulenko O.; Cho Y.-K. Advances in Facemasks during the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. ACS App. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 3891–3908. 10.1021/acsabm.0c01329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- accessed April 17,

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)—Decontamination and Reuse of Filtering Facepiece Respirators, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated October 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/decontamination-reuse-respirators.html (accessed April 17, 2021).

- Viscusi D. J.; King W. P.; Shaffer R. E. Effect of Decontamination on the Filtration Efficiency of Two Filtering Facepiece Respirator Models. J. Int. Soc. Respir. Prot. 2007, 24, 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. H.; Chen C. C.; Huang S. H.; Kuo C. W.; Lai C. Y.; Lin W. Y. Filter quality of electret masks in filtering 14.6-594 nm aerosol particles: Effects of five decontamination methods. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0186217 10.1371/journal.pone.0186217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillet A. M.; Nemer M. B.; Storch S.; Sanchez A. L.; Piekos E. S.; Leonard J.; Hurwitz I.; Perkins D. J. COVID-19 global pandemic planning: Performance and electret charge of N95 respirators after recommended decontamination methods. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 740–748. 10.1177/1535370220976386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimbuch B. K.; Kinney K.; Lumley A. E.; Harnish D. A.; Bergman M.; Wander J. D. Cleaning of filtering facepiece respirators contaminated with mucin and Staphylococcus aureus. Am. J. Infect. Control 2014, 42, 265–270. 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi D. J.; Bergman M. S.; Eimer B. C.; Shaffer R. E. Evaluation of five decontamination methods for filtering facepiece respirators. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 815–827. 10.1093/annhyg/mep070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos R. K.; Jin J.; Rafael G. H.; Zhao M.; Liao L.; Simmons G.; Chu S.; Weaver S. C.; Chiu W.; Cui Y. Decontamination of SARS-CoV-2 and Other RNA Viruses from N95 Level Meltblown Polypropylene Fabric Using Heat under Different Humidities. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14017–14025. 10.1021/acsnano.0c06565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman M. S.; Viscusi D. J.; Heimbuch B. K.; Wander J. D.; Sambol A. R.; Shaffer R. E. Evaluation of Multiple (3-Cycle) Decontamination Processing for Filtering Facepiece Respirators. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2010, 5, 155892501000500405 10.1177/155892501000500405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heckert R. A.; Best M.; Jordan L. T.; Dulac G. C.; Eddington D. L.; Sterritt W. G. Efficacy of vaporized hydrogen peroxide against exotic animal viruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3916–3918. 10.1128/aem.63.10.3916-3918.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills D.; Harnish D. A.; Lawrence C.; Sandoval-Powers M.; Heimbuch B. K. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation of influenza-contaminated N95 filtering facepiece respirators. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, e49–e55. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lore M. B.; Heimbuch B. K.; Brown T. L.; Wander J. D.; Hinrichs S. H. Effectiveness of three decontamination treatments against influenza virus applied to filtering facepiece respirators. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2012, 56, 92–101. 10.1093/annhyg/mer054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher E. M.; Shaffer R. E. A method to determine the available UV-C dose for the decontamination of filtering facepiece respirators. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 287–295. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley W. G.; Martin S. B. Jr; Thewlis R. E.; Sarkisian K.; Nwoko J. O.; Mead K. R.; Noti J. D. Effects of Ultraviolet Germicidal Irradiation (UVGI) on N95 Respirator Filtration Performance and Structural Integrity. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2015, 12, 509–517. 10.1080/15459624.2015.1018518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelie P.; Reesink H.; Lucas C. Inactivation of 12 viruses by heating steps applied during manufacture of a hepatitis B vaccine. J. Med. Virol. 1987, 23, 297–301. 10.1002/jmv.1890230313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell M. E.; Subbarao K.; Feinstone S. M.; Taylor D. R. Inactivation of the coronavirus that induces severe acute respiratory syndrome, SARS-CoV. J. Virol. Methods 2004, 121, 85–91. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig-Begall L. F.; Wielick C.; Dams L.; Nauwynck H.; Demeuldre P.-F.; Napp A.; Laperre J.; Haubruge E.; Thiry E. The use of germicidal ultraviolet light, vaporized hydrogen peroxide and dry heat to decontaminate face masks and filtering respirators contaminated with a SARS-CoV-2 surrogate virus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 106, 577–584. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.; Chu J.; Perera M.; Hui K.; Yen H.-L.; Chan M.; Peiris M.; Poon L. Stability of SARS-CoV-2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet 2020, 1, E10 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y.; Song Q.; Gu W. Decontamination of Surgical Face Masks and N95 Respirators by Dry Heat Pasteurization for One Hour at 70 °C. Am. J. Infect. Control 2020, 48, 880–882. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L.; Xiao W.; Zhao M.; Yu X.; Wang H.; Wang Q.; Chu S.; Cui Y. Can N95 respirators be reused after disinfection? How many times?. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6348–6356. 10.1021/acsnano.0c03597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3M Technical Bulletin. Disinfection of Filtering Facepiece Respirators, March 2020. https://www.apsf.org/wp-content/uploads/news-updates/2020/Disinfection-of-3M-Filtering-Facepiece-Respirators.pdf (accessed April 17, 2021).

- Bergman M. S.; Viscusi D. J.; Heimbuch B. K.; Wander J. D.; Sambol A. R.; Shaffer R. E. Evaluation of Multiple (3-Cycle) Decontamination Processing for Filtering Facepiece Respirators. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2010, 5, 155892501000500405 10.1177/155892501000500405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Q. X.; Shan H.; Zhang C. M.; Zhang H. L.; Li G. M.; Yang R. M.; Chen J. M. Decontamination of face masks with steam for mask reuse in fighting the pandemic COVID-19: experimental supports. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1971–1974. 10.1002/jmv.25921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. H.; Tang F. C.; Hung P. C.; Hua Z. C.; Lai C. Y. Relative survival of Bacillus subtilis spores loaded on filtering facepiece respirators after five decontamination methods. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 754–762. 10.1111/ina.12475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysik D.; Niemirowicz-Laskowska K.; Bucki R.; Tokajuk G.; Mystkowska J. Artificial Saliva: Challenges and Future Perspectives for the Treatment of Xerostomia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3199 10.3390/ijms20133199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt A.; Dikin D. A.; Kurmaev E. Z.; Lee Y. H.; Luan N. V.; Chang G. S.; Moewes A. Modulation of the band gap of graphene oxide: The role of AA-stacking. Carbon 2014, 66, 539–546. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruosi A.; Raisch C.; Verna A.; Werner R.; Davidson B. A.; Fujii J.; Kleiner R.; Koelle D. Electron sampling depth and saturation effects in perovskite films investigated by soft x-ray absorption spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 125120 10.1103/PhysRevB.90.125120. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eads C. N.; Zhong J.-Q.; Kim D.; Akter N.; Chen Z.; Norton A. M.; Lee V.; Kelber J. A.; Tsapatsis M.; Boscoboinik J. A.; Sadowski J. T.; Zahl P.; Tong X.; Stacchiola D. J.; Head A. R.; Tenney S. A. Multi-modal surface analysis of porous films under operando conditions. AIP Adv. 2020, 10, 085109 10.1063/5.0006220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V.; Biesinger M. C.; Linford M. R. The Gaussian-Lorentzian Sum, Product, and Convolution (Voigt) functions in the context of peak fitting X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) narrow scans. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 447, 548–553. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.03.190. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jain D.; Mamtani K.; Gustin V.; Gunduz S.; Celik G.; Waluyo I.; Hunt A.; Co A. C.; Ozkan U. S. Enhancement in Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activity of Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanostructures in Acidic Media through Chloride-Ion Exposure. ChemElectroChem 2018, 5, 1966–1975. 10.1002/celc.201800134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel B.; Newville M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2005, 12, 537–541. 10.1107/S0909049505012719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L.; Xiao W.; Zhao M.; Yu X.; Wang H.; Wang Q.; Cui Y. Can N95 respirators be reused after disinfection? And for how many times?. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6348–6356. 10.1021/acsnano.0c03597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Kasloff S. B.; Leung A.; Cutts T.; Strong J. E.; Hills K.; Gu F. X.; Chen P.; Vazquez-Grande G.; Rush B.; Lother S.; Malo K.; Zarychanski R.; Krishnan J. Decontamination of N95 masks for re-use employing 7 widely available sterilization methods. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0243965 10.1371/journal.pone.0243965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinshpun S. A.; Yermakov M.; Khodoun M. Autoclave sterilization and ethanol treatment of re-used surgical masks and N95 respirators during COVID-19: impact on their performance and integrity. J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 608–614. 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R. J.; Morris D. H.; van Doremalen N.; Sarchette S.; Matson M. J.; Bushmaker T.; Yinda C. K.; Seifert S. N.; Gamble A.; Williamson B. N.; Judson S. D.; deWit E.; Lloyd-Smith J. O.; Munster V. J. Effectiveness of N95 respirator decontamination and reuse against SARS-CoV-2 virus. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2253 10.3201/eid2609.201524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao L.; Xiao W.; Zhao M.; Yu X.; Wang H.; Wang Q.; Chu S.; Cui Y. Can N95 respirators be reused after disinfection? How many times?. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6348–6356. 10.1021/acsnano.0c03597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen G. S.; Cheng Y.; Daemen L. L.; Lamichhane T. N.; Hensley D. K.; Hong K.; Meyer H. M.; Monaco S. J.; Levine A. M.; Lee R. J.; Betters E.; Sitzlar K.; Heineman J.; West J.; Lloyd P.; Kunc V.; Love L.; Theodore M.; Paranthaman M. P. Polymer, Additives, and Processing Effects on N95 Filter Performance. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 1022–1031. 10.1021/acsapm.0c01294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Physical, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties of Polymers. In Biosurfaces: A Materials Science and Engineering Perspective; Balani K.; Verma V.; Agarwal A.; Narayan R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, 2014; pp 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hager E.; Farber C.; Kurouski D. Forensic identification of urine on cotton and polyester fabric with a hand-held Raman spectrometer. Forensic Chem. 2018, 9, 44–49. 10.1016/j.forc.2018.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.-C.; Krommenhoek P. J.; Watson S. S.; Gu X. Depth profiling of degradation of multilayer photovoltaic backsheets after accelerated laboratory weathering: Cross-sectional Raman imaging. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 144, 289–299. 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bistričić L.; Borjanović V.; Leskovac M.; Mikac L.; McGuire G. E.; Shenderova O.; Nunn N. Raman spectra, thermal and mechanical properties of poly(ethylene terephthalate) carbon-based nanocomposite films. J. Polym. Res. 2015, 22, 39 10.1007/s10965-015-0680-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. S.; Batchelder D.; Pyrz R. Estimation of crystallinity of isotactic polypropylene using Raman spectroscopy. Polymer 2002, 43, 2671–2676. 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00053-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Michielsen S. Isotactic polypropylene morphology–Raman spectra correlations. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 1330–1338. 10.1002/app.1968. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. S.; Batchelder D. N.; Pyrz R. Estimation of crystallinity of isotactic polypropylene using Raman spectroscopy. Polymer 2002, 43, 2671–2676. 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00053-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hiejima Y.; Takeda K.; Nitta K.-h. Investigation of the Molecular Mechanisms of Melting and Crystallization of Isotactic Polypropylene by in Situ Raman Spectroscopy. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 5867–5876. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X.; Lin Z.; Wang Y.; He Z.; Wang M.; Jin G. In-Line Monitoring the Degradation of Polypropylene under Multiple Extrusions Based on Raman Spectroscopy. Polymers 2019, 11, 1698 10.3390/polym11101698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazaux J. About the charge compensation of insulating samples in XPS. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2000, 113, 15–33. 10.1016/S0368-2048(00)00190-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. X.; Lv J. C.; Ren Y.; Zhi T.; Chen J. Y.; Zhou Q. Q.; Lu Z. Q.; Gao D. W.; Jin L. M. Surface modification of polyester fabric with plasma pretreatment and carbon nanotube coating for antistatic property improvement. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 359, 196–203. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.10.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hantsche H. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database (Beamson, G.; Briggs, D.). J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70, A25 10.1021/ed070pA25.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polzonetti G.; Russo M. V.; Furlani A.; Iucci G. Interaction of H2O, O2 and CO2 with the surface of polyphenylacetylene films: an XPS investigation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1991, 185, 105–110. 10.1016/0009-2614(91)80148-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart S. G.; Hitchcock A. P.; Smith A. P.; Ade H.; Rightor E. G. Inner-Shell Excitation Spectroscopy of Polymer and Monomer Isomers of Dimethyl Phthalate. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 2267–2276. 10.1021/jp963419d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. P.; Urquhart S. G.; Winesett D. A.; Mitchell G.; Ade H. Use of near Edge X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectromicroscopy to Characterize Multicomponent Polymeric Systems. Appl. Spectrosc. 2001, 55, 1676–1681. 10.1366/0003702011954008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rightor E. G.; Hitchcock A. P.; Ade H.; Leapman R. D.; Urquhart S. G.; Smith A. P.; Mitchell G.; Fischer D.; Shin H. J.; Warwick T. Spectromicroscopy of Poly(ethylene terephthalate): Comparison of Spectra and Radiation Damage Rates in X-ray Absorption and Electron Energy Loss. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 1950–1960. 10.1021/jp9622748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koprinarov I.; Lippitz A.; Friedrich J. F.; Unger W. E. S.; Wöll C. Oxygen plasma induced degradation of the surface of poly(styrene), poly(bisphenol-A-carbonate) and poly(ethylene terephthalate) as observed by soft X-ray absorption spectroscopy (NEXAFS). Polymer 1998, 39, 3001–3009. 10.1016/S0032-3861(97)10062-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gross T.; Lippitz A.; Unger W. E. S.; Friedrich J. F.; Wöhll C. Valence band region XPS, AFM and NEXAFS surface analysis of low pressure d.c. oxygen plasma treated polypropylene. Polymer 1994, 35, 5590–5594. 10.1016/S0032-3861(05)80029-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.