Summary

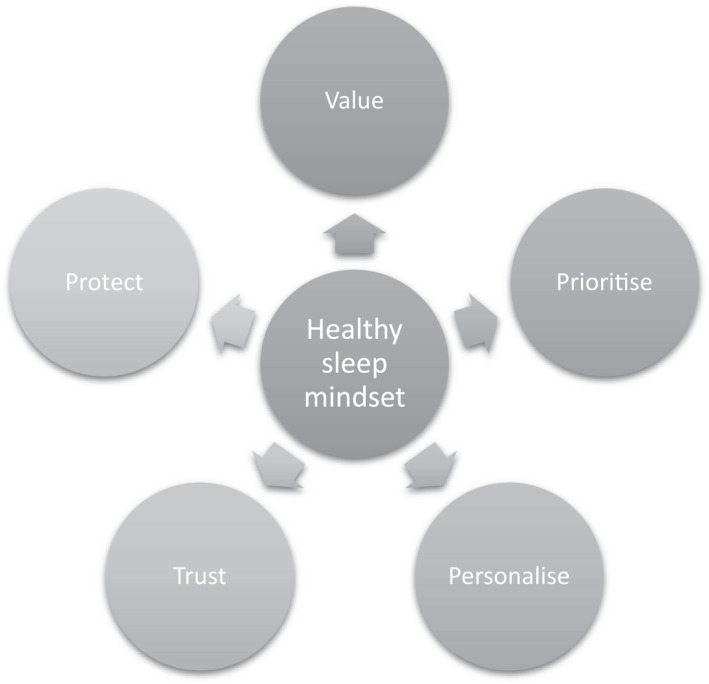

The ‘5 Principles of good sleep health’ are proposed (a) to facilitate improved public health engagement with the importance of looking after your sleep; and (b) to offer a first line intervention for people with poor sleep and mild insomnia symptoms, that goes beyond the scope of what is traditionally known as ‘sleep hygiene’. The ‘5 Principles’ were developed by the author for the UK National Health Service (NHS) campaign ‘Every Mind Matters’, initiated in 2020 by Public Health England, and supported by the Mental Health Foundation. The author served as the campaign spokesperson for sleep as a critical ingredient in mental wellbeing. The ‘5 Principles’ encourage people to Value, Prioritise, Personalise, Trust, and Protect their sleep. They are intended to educate about sleep health and to support evidence‐based self‐management of sleep, and not as an alternative to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) which is the guideline treatment for chronic insomnia disorder. However, they may bridge an important gap in self‐care practices for many people. The ‘5 Principles’ would benefit from formal research evaluation.

Keywords: insomnia, intervention, public health, sleep, sleep hygiene

1. INTRODUCTION

Like many others in the field of behavioural sleep medicine I have frequently been asked to provide my ‘top tips’ for getting a good night's sleep. Requests of this kind have come from diverse sources – newspapers and magazines, radio and television stations, social media, and also from health care, social care, and third sector (charitable) organisations. Having worked in the sleep field for several decades, my experience is that public interest in sleep has never been greater than it is now. Indeed, at times the demand feels almost insatiable. There also appears to be no shortage of folks who are ‘passionate about sleep’ (variously sleep gurus and evangelists; wellbeing champions; app and device developers), and they always seem willing to venture an opinion or a solution. Don't misunderstand me, I don't think that this is necessarily a bad thing. Sleep is one of the most accessible and least stigmatised topics in the health conversation, and sleep belongs to the people, not to the professionals. Rather, I think we have a duty of care, from an evidence‐based clinical perspective, to contribute actively to public engagement with the science of sleep. So, what then should I say, when it comes to offering the ubiquitous ‘sound bites’ about why society has a poor relationship with sleep or about how to overcome sleepless nights? What do I have to say that's different or new? Does it really just boil down to ‘sleep hygiene’?

Almost 30 years ago, I wrote The Good Sleep Guide which formed part of a National Medical Advisory Committee report, published by the Crown Office in Scotland (National Medical Advisory Committee, 1994). Although I have written self‐help books and other similar materials during the interim period, my work has been more in the research domain, and I am rather ashamed to admit that it wasn't until early in 2020 that my attention again turned to what I could usefully say within just a couple of pages. Although the ‘patient handout’ may be a dated concept, and there are more contemporary ways of distributing a leaflet's worth of content, there seems to be enduring need and demand for summarised sleep wisdom. An opportunity arose that gave me more focus than usual to consider what a revised version of my sleep guide would look like.

I was approached by Public Health England (PHE) which is part of the UK National Health Service (NHS) to work with them on their mental health campaign Every Mind Matters. This was to be an online and social media campaign with the call to action “Feeling stressed, anxious, low or struggling to sleep? Every Mind Matters can help with expert advice, practical tips and personalised actions to help stay on top of your wellbeing”. It was very gratifying that PHE wanted to make sleep a core element of this national effort, and I was delighted to be asked to serve as the ‘face’ of the campaign. So, I began to ask myself what were the most important things to include?

We agreed the brief. The content was to be salient to everyone, not just to poor sleepers or those with insomnia. The focus, therefore, was not on treatment but on universal insights and practical advice. The NHS team involved recognised that there are gaps in clinical assessment and treatment services for people with sleep disorders, but this was a public health campaign. The intention was to position sleep as central to emotional health and mental wellbeing, as something that everyone should and could look after, much in the same way that diet and exercise are core to behavioural health. I was very pleased that the Mental Health Foundation, a UK charity dedicated to advocacy and improving mental health in the community, were also involved and in an associated development they approached me about contributing to their report, Taking Sleep Seriously: Sleep and our Mental Health (Mental Health Foundation, 2020).

My thoughts inevitably turned to ‘sleep hygiene’; so often the subject matter of the sleep tips that I mentioned earlier. Although Dr Nathaniel Kleitman first referred to the ‘hygiene of sleep and wakefulness’ as a chapter heading his early book (Kleitman, 1939), we owe a huge debt of gratitude to the late Dr Peter Hauri, who developed the concept, and in 1977 he operationalised it as follows:

Sleep Hygiene Education is intended to provide information about lifestyle (diet, exercise, substance use) and environmental factors (light, noise, temperature) that may interfere with or promote better sleep. Sleep hygiene also may include general sleep facilitating recommendations, such as allowing enough time to relax before bedtime, and information about the benefits of maintaining a regular sleep schedule (Hauri, 1977).

It is quite remarkable how much traction sleep hygiene has had over the past 45 years! Although it is not a sufficient standalone intervention for chronic insomnia, and would not qualify as the entry level treatment in a stepped‐care service model (Espie, 2009; Chung et al., 2018), sleep hygiene is typically integrated within evidence‐based CBT programmes and is referenced in clinical guidelines throughout the world as a contributing factor to sleep education and sleep improvement (Edinger et al., 2021; Qaseem et al., 2016; Riemann et al., 2017; Sateia et al., 2017; Wilson et al., 2019). Undoubtedly, therefore, sleep hygiene has served as a building block of the behavioural sleep medicine approach, because it addresses the question ‘what can I do?’ and it channels people's thinking into self‐care as the answer. It has also I think proven to be an alluring catchphrase.

It is important to note, however, that Peter Hauri did not intend sleep hygiene to be thoughtlessly distributed. In fact, he lamented the practice that “many mental health professionals hand their patients little pamphlets filled with ‘sleep hygiene’ rules” and suggested that this would be “no more effective … than handing a neurotic patient a list of ten ‘rules for healthy emotional living’” (Hauri, 1991, p. 66). Rather, Hauri's focus was upon summarising research evidence “accumulated to scientifically support a set of rules on how to get to better sleep” (op. cit., p. 65), and it is likely for this reason that we see iteration of sleep hygiene content across Hauri's writings. For him sleep hygiene was not intended to become static or rigid, and the term itself was not sacrosanct. Indeed, as he put it, “… the name stuck, although I never liked it” (op. cit., p. 65). What he did like, and was relentlessly positive about, was the probability of there being one or two ‘rules’ that, once discovered for a given individual, would unlock better sleep for them. Peter Hauri embodied sleep wisdom, and we still miss him.

Reflecting on his encouragement to iterate led me to a set of 5 key principles that underpin good sleep health, each of which I think reflect scientific truth and practical value. I am sure that others would suggest additions to my list; or may prefer other synonyms. Any omissions or confusions are mine. However, I trust there is reasonable consensus that, as principles, they are fundamental and incontrovertible, and that they are salient to everyone and should stand the test of time. The ‘5 Principles’ of good sleep health that I came up with were that we should encourage people to Value, Prioritise, Personalise, Trust, and Protect their sleep (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvQTjAlIvI8).

The target audience for the ‘5 Principles’ was the population at large, rather than a subsection of the general public; and, it should be noted, this does present certain challenges. Some people reading the principles will be good sleepers already, whilst others will not, and some of these poor sleepers will have sleep disorders. Likewise, there will be personal, situational, and occupational factors, as well as medical and psychological factors, that contribute to an individual's sleep opportunity, sleep pattern and sleep quality at any given point in time. For these reasons I have tried to frame the principles in a way that is somewhat generic but still, I trust, compelling, and with an emphasis on being supportive and encouraging rather than perplexing or even anxiety‐provoking. The principles are by no means intended as a panacea and I do not wish to oversimplify the journey to good sleep health, or back to good sleep health in the case of those with chronic sleep problems. However, when one thinks of what can be safely said to be salient to everyone I do believe that we would all do well to value, prioritise, personalise, trust and protect our sleep.

The starting point for the ‘5 Principles’ lies in valuing sleep. This is because there is a fundamental problem for achieving and sustaining sleep health if a person does not regard sleep as a ‘need to have’, compared with a ‘nice to have’. It is absolutely crucial not to cut corners where sleep is concerned. Logically, valuing something means that it merits a priority place in our lives. So often we can take important things (and people too!) for granted. This is why the second principle is to encourage people to actively prioritise sleep in behavioural terms, not just in their intentions. Next, I emphasise the discovery of your own sleep pattern and timing. I believe this personalisation through trial‐and‐error learning is very important. Understanding the likely range, within which your sleep need is likely to fall, is a helpful range‐finding exercise (c.f. National Sleep Foundation: Hirshkowitz et al., 2015), but the fine tuning is conducted by experimentation. This is why, having a ‘trusting sleep mindset’ is the fourth principle that I see as key to sleep health. We don't ever become good at sleeping, though we can become good sleepers. The power of the sleep system primarily rests in the regulatory properties of the homeostatic and circadian system reliably delivering sleep to us. Finally, and this takes us full circle to a set of both ‘traditional’ (e.g. caffeine) and contemporary (e.g. smart phones) sleep hygiene factors, I suggest we need to protect our sleep. Of course, addressing sleep hygiene may at times also promote healthy sleep, but in the main this is by mitigating factors that interfere with sleep initiation or maintenance. In the section on protective factors, you will see that I have dovetailed some cognitive behavioural strategies with sleep hygiene. I do not intend this to be CBT, or even ‘CBT light’, so I do encourage people who have established sleep problems to seek professional advice.

In Appendix 1, I have shared with you the detailed content of the ‘5 Principles’ material that was used in the NHS Every Mind Matters, and the Mental Health Foundation (UK) campaigns in 2020. My hope is that you may find it useful, and that you will feel free to share it also through your channels to support your public engagement with sleep health. I also hope that this paper will stimulate research, acknowledging that the material has not been evaluated formally for impact at this point.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

CAE is the Co‐Founder and Chief Scientist of Big Health Inc. and is a shareholder in the company. Unrelated to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

CAE developed the concepts underlying this work and wrote the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The ‘5 Principles’ of Good Sleep Health were developed and written by Dr Colin A. Espie PhD, DSc Professor of Sleep Medicine, University of Oxford for the UK National Health Service (NHS) campaign ‘Every Mind Matters, initiated in 2020 by Public Health England, and supported by the Mental Health Foundation. The ‘5 Principles’ are also summarised here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OvQTjAlIvI8.

APPENDIX 1.

The ‘5 Principles’ of good sleep health

What do you expect to read when you come across a heading like this? Most likely a set of ‘sleep tips’, some ‘do's’ and some ‘don'ts’. However, the ‘5 Principles’ are not just about the usual suspects – things like caffeine, comfortable mattresses, ideal bedroom temperatures, the use of devices and the like. Such things, typically known as sleep hygiene, are very important but they may also at times feel a little superficial. After all, sleep is fundamental to every living organism. Cats and dogs, birds and butterflies don't sleep well because they leave their smartphones in the living room, or because they cut down on their Americano intake! So, don't you think it unlikely that those things in themselves will be crucial to how humans sleep well?

I want to encourage you to consider what is fundamental for you to develop a healthy and trusting sleep mindset. Let's get the principles and practices of a healthy sleep lifestyle right, and let's base those upon the best knowledge and the best science. I want the ‘5 Principles’ to really help you to get your sleep as healthy as it can be. I want you to get the most out of your sleep, because we all absolutely need to get the benefit of this precious part of nature's provision for good physical and mental health. For that reason, the ‘5 Principles’ contain truths that apply to everyone, whether or not you have a sleep problem right now.

Of course, I do know that your personal or work situation, as well as medical or emotional factors, will contribute to your opportunity to sleep, or perhaps will interfere with your sleep pattern and sleep quality. The ‘5 principles’ are not the whole answer, by any means, but they may be a useful starting point for you. Also, the ‘5 Principles’ are not a treatment for a sleep problem. If you do have concerns about troublesome sleep that has become persistent, I urge you to seek professional help. Your sleep certainly matters enough to do that (Figure A1).

FIGURE A1.

The ‘5 Principles’ of Good Sleep Health

First principle: Value your sleep

When we strip things down to the most basic of life's essentials, when we explore the foundations of our needs as human beings, what do we find? Well, we discover that sleep is one of the most important physiological ingredients that give us the capability to live our lives. We need oxygen so we can breathe, we need water so we are hydrated, we need food so we are nourished, and we need sleep so we can function. Sleep plays a central role in so many things. These include the renewal and repair of our body's tissues, our metabolism, our physical growth and development, our ability to fight infection, our learning skills and memory, and our ability to regulate our emotions. Wow, what a list!

Perhaps you didn't realise that sleep is quite so crucial? Although I'm sure you did if you sometimes struggle with sleep! You see, the quality of our daytime alertness, energy, productivity, and mood are all heavily dependent upon sleep. Just think of how you feel the next day if you haven't slept. If clean drinking water and sufficient food are crucial to life, so is having enough good quality sleep. So please don't cut corners where sleep is concerned. It can be damaging to health in the long‐term, and that shouldn't come as any surprise. The same would be true if we were malnourished, wouldn't it? But sleeping is actually a bit more like breathing, because you can't sleep deliberately. You don't decide to breathe, and you can't hold your breath – well not for very long! Likewise, you can't switch sleep on. You can only ‘set the scene’ for sleep, with the right attitudes and routines, and this gives sleep the best chance of happening naturally and automatically. It is also impossible to stay awake indefinitely. Indeed, one of the dangers of not getting enough sleep on a regular basis is that you may fall asleep without intending to because sleep will overtake your best efforts to resist it. The first principle of establishing healthy sleep then is that you need to take sleep seriously. You should value sleep as highly as a fresh water supply, good food and the air that you breathe.

Second principle: Prioritise your sleep

This follows from a mind‐set that takes sleep seriously. You should prioritise getting your sleep. In other words, not just warm thoughts and good intentions to get enough sleep, but action. Prioritising means making decisions to put sleep first, or at least higher up the list, when it comes to making choices of what you do. I encourage you to listen to our body and your brain if they are telling you that you need to get to your bed! It really is OK to be tired and it's OK to feel sleepy. At times this will mean letting go of things that you might want to do, and I know this can be difficult to put into practice. Who likes to be the first to admit they are tired, or to have to stifle a yawn, or to leave the party or the online chatroom early, especially if it just seems to be getting going and people are still joining? It's possible that you will feel a bit guilty that you are letting other people down by prioritising your sleep. To tell people that you need to turn in for the night is difficult, however, like everything else it gets easier with practice!

Think of other circumstances where we have already become more familiar with managing pressure when it comes to making choices. For example, expressing our personal dietary needs is becoming a bit easier than it was in the past. I'm not saying that all our restaurants have extensive menus that suit everyone, but there is generally more of a food choice in recognition of the fact that people are different and have different dietary preferences. In the best scenarios, there will be respect rather than negative comment in demonstrating self‐discipline about being true to our values. We want to value our sleep – right? Remember that the purpose of sleep is to deliver health, wellbeing and ability to function during the day. A well slept, well rested you is going to be better for everyone.

Of course, the main reason that it can be difficult to prioritise your sleep is that we often don't have control of the situation, and that we can't simply choose to prioritise sleep. You could be working shifts, and your night‐time might inevitably have to be given over to work. You might have a new baby at home; and so, I hear you saying, ‘I wish!’ to the idea of prioritising your sleep. I really do hear you. On the other hand, if it's hard for you to choose how and when to sleep, I suspect that you will even more wholeheartedly agree with the need to prioritise sleep when you do get the opportunities to do so. Towards the end of this piece on the ‘5 Principles’ you will see that I have written a brief section on the importance of society accommodating sleep as a priority. So, the second principle is about making commitments and setting behavioural goals to create the necessary space for sleep in your life whenever you can.

Third principle: Personalise your sleep

If you are following along with this, then hopefully you are now considering how you can value your sleep and are thinking of actions that you can take to prioritise getting your sleep … but how much sleep? … and how much is enough? This is probably the most common question that I get asked! And then people ask about quality of sleep – is quality of sleep not every bit as important as quantity of sleep? So… my third principle is about figuring out and understanding your personalised sleep requirement, and then satisfying those personal needs. I say personal because we are not all the same. It never ceases to amaze me that we seem to think everyone should follow exactly the same sleep pattern. Our other physical characteristics, appetites, and preferences differ, don't they?

So, how much sleep do you, personally, need? How do you figure it out? That's a question with a simpler answer than you might have thought – you figure it out by trial and error. That is actually how we learn most things in life. For example, if I were to ask you the question ‘how do you know your shoe size?’, would you not think it a bizarre question? Did someone tell you what it ought to be? Have we all got the same shoe size perhaps? No, you find find the shoe size you need by trying on different sizes until you find the one that fits most comfortably. Personalising your sleep is exactly the same; it's simply about experimenting to find the best fit. How long do you need to be in bed to get enough sleep? If you are willing to experiment to discover your best ‘sleep window’, I fully expect you will figure it out.

Why not become your own scientist for a couple of weeks? Experiment with being in bed for a bit longer than you are used to, does this lead to you getting a bit more sleep? Or try being in bed for a shorter period, to see if it strengthens your sleep drive and helps you to sleep right through. After a while you will discover what works best for you. Part of this personalising is about your ‘chronotype’. That is, when is the best time for you to go to bed and to get up? People who are natural ‘night owls’ will tend to begin to feel sleepy later in the evening, and to still feel sleepy later into the morning. ‘Morning larks’ are the opposite, feeling sleepy earlier in the evening and waking up alert early, first thing in the morning… or even before first thing! You might be neither an owl nor a lark, but my point is to know your sleep type. Try to personalise your sleep by getting the amount of sleep that you require, and at the time you require it. If you do this your experience of sleep quality will also begin to match up.

Fourth principle: Trust your sleep

If you have experimented a bit and given sleep the right‐sized space or sleep window at the right time for you, the main thing to do next is to trust your sleep to get itself into a good pattern. It helps if you can use the same pattern and timing for sleep during the weekend as on weekdays. Remember that sleep is a natural process that the whole animal kingdom can rely upon. So, once you get your pattern and timing right, I suggest that you let your own sleep needs and your sleep pattern drive you, rather than you trying to drive them. A consistent and reliable sleep from night to night is good for our health, just like a regular balanced diet and remaining well hydrated is healthy. As I have said I know that there are many challenges to setting up and sticking to a regular sleep schedule, but my main point here is to encourage you to trust your sleep biology to help you get that schedule into the best possible shape.

Let me let you into a secret that helps here – good sleepers are actually not ‘good at sleeping’. They are usually not doing anything at all except trusting and expecting sleep to come spontaneously. In fact, to be honest, they seldom even think about it. Sleep happens because they get sleepy and fall asleep in a regular pattern. Honestly, nobody is hiding a secret from you about how to get to sleep, or to get back to sleep if you wake up! Trusting your sleep involves resisting the temptation to grab at solutions, trying this and trying that as if you are balancing on some kind of tightrope. This just heightens anxiety, leads to preoccupation with sleep, and will make you feel precarious and desperate. I must tell you, as you probably already know, it absolutely doesn't work to become frenetic and to overthink the whole thing.

If you can't sleep then just get up for a while, accept that, and go back to bed when you feel sleepy again. Please remember too that you can still experiment until you get the shape and timing of your sleep right. Trial and error, as I said before, but informed by what you have already tried. Be prepared to try going to bed for shorter periods of time too so that you are properly sleepy when you settle down; and get up at the same time each morning. All this strengthens the sleep–wake rhythm and helps to establish a pattern you can trust. Keep a note of your experiments if you like and then you can rely on your own evidence from what works and what doesn't.

Fifth principle: Protect your sleep

Finally, let's think about how you can protect your sleep, by avoiding or shielding yourself from things that can cause some upset to sleep. This is where elements of sleep hygiene come in, along with some advice that is based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) strategies. What I am offering here forms a light armour to help you protect your sleep, but it is not a treatment for insomnia. For that you should seek professional help or use treatment programmes that are evidence‐based CBT and recommended by trusted professionals. Protecting your sleep falls into several categories.

First and foremost, I would emphasise that sleep thrives on a pattern. Protect your sleep from too many changes. Experiment to get it right and then retain the pattern. However, don't overanalyse things. Devices and gadgets may be helpful if they provide you with some useful information on your sleep pattern, however, they are often a mixed blessing, especially if you get too caught up in the data. Good sleepers don't need to monitor sleep like this, and for some people it is counterproductive to do so.

Second, the racing mind is the fiercest enemy of sleep, and this is where you need the most effective armour. Put the day to rest long before you go to bed by thinking through the day past and planning for tomorrow, wind down from mid‐evening on and be kind to yourself if you struggle to sleep. You are not alone in being wakeful at night!

Third, and related to this last point, don't try to force yourself to sleep. It simply doesn't work! If you don't fall asleep then it's ok to do something else for a while, then settle down again and ‘reboot’. Sleepiness will most likely come calling again. Use that sleepiness as your cue to fall asleep naturally.

Fourth, consider lifestyle factors. The stimulant properties of caffeine and nicotine delay the start of sleep so caffeinated drinks are best avoided in the evening; and bear in mind that most e‐cigarettes still contain nicotine! Alcohol also disrupts sleep, particularly during the second half of the night; and heavy meals close to bedtime can lead to restless sleep. Exercise is a good thing, but it's best to keep a gap for a wind down time before you retire.

Fifth, there are environmental factors that affect sleep. Sleep generally likes cooler and darker, but you can try things out – not too hot or too cold, not too bright or too dark. Also, not too noisy or too quiet. Try to keep the bedroom well ventilated, and make sure your bed is comfortable.

Finally, protect your sleep from tablets and smartphones. The problem that I see is not just that they are sources of light in the bedroom, but that they are triggers to remaining alert as you search information, engage in social behaviour, or play games that act as a recruiting sergeant for vigilance rather than sleep!

Following the ‘5 Principles’ of good sleep health

So, in summary and conclusion, I urge you to value, prioritise, personalise, trust and protect your sleep. Following these ‘5 Principles’ is easy to say and harder to do, but good sleep health will enable you to be your best you. None of us can do without sleep; and why on earth would we ever want to? Certainly, there are pressures on our lives that can make sleep hard to come by, but we need to figure this one out as best we can. It's important that we do, because sleep is nature's great healer and provider, not just for us but for all living things. You may feel you are sleeping OK but could sleep better; or sleep more; or you may have been recently having some sleep troubles that need attention. I hope my advice can help get you on the right track. If you have a long‐standing sleep problem that requires professional attention, the ‘5 Principles’ are important, but they will not be enough. Don't hesitate to track down advice from your medical or clinical advisers. If you do need more help, ask them where you can access cognitive behavioural therapy from a trusted source, because CBT is the best evidenced approach for insomnia when it becomes persistent.

The responsibilities of public health authorities and clinical services

I have encouraged you to do what you can to promote your own sleep health, and to seek help if you have troublesome sleep symptoms or a sleep disorder. However, I also want to emphasise how important it is that governments, health services, employers, and other authorities, who are in a position to influence sleep health policy and practice, play their part as well. The facilitation and promotion of sleep is every bit as important to the health of the population as nutrition and exercise. We also very much need improved and extended clinical services that take sleep disorders more seriously for the countless numbers of folks with sleep problems. I am sure you will join with me in advocating for better sleep for all!

Espie, C. A. (2022). The ‘5 principles’ of good sleep health. Journal of Sleep Research, 31, e13502. 10.1111/jsr.13502

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Chung, K. F. , Lee, C. T. , Yeung, W. F. , Chan, M. S. , Chung, E. W. , & Lin, W. L. (2018). Sleep hygiene education as a treatment of insomnia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Family Practice, 35(4), 365–375. 10.1093/fampra/cmx122. PMID: 29194467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger, J. D. , Arnedt, J. T. , Bertisch, S. M. , Carney, C. E. , Harrington, J. J. , Lichstein, K. L. , Sateia, M. J. , Troxel, W. M. , Zhou, E. S. , Kazmi, U. , Heald, J. L. , & Martin, J. L. (2021). Behavioral and psychological treatments for chronic insomnia disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 17(2), 255–262. 10.5664/jcsm.8986. PMID: 33164742; PMCID: PMC7853203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie, C. A. (2009). “Stepped care”: A health technology solution for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy as a first line insomnia treatment. Sleep, 32(12), 1549–1558. 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1549. PMID: 20041590; PMCID: PMC2786038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauri, P. J. (1977). The sleep disorders: Current concepts. Scope Publications, Upjohn. [Google Scholar]

- Hauri, P. J. (1991). Sleep hygiene, relaxation therapy, and cognitive interventions. In Hauri P. J. (Ed.), Case studies in insomnia (pp. 65–84). Springer, US. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz, M. , Whiton, K. , Albert, S. M. , Alessi, C. , Bruni, O. , DonCarlos, L. , Hazen, N. , Herman, J. , Katz, E. S. , Kheirandish‐Gozal, L. , Neubauer, D. N. , O'Donnell, A. E. , Ohayon, M. , Peever, J. , Rawding, R. , Sachdeva, R. C. , Setters, B. , Vitiello, M. V. , Ware, J. C. , & Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation's sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. Epub 2015 Jan 8 PMID: 29073412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleitman, N. (1939). The hygiene of sleep and wakefulness. In Sleep and Wakefulness (Chapter 30). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Foundation (2020). Taking sleep seriously: Sleep and our mental health. Mental Health Foundation, UK. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/MHF_Sleep_Report_UK.pdf [Google Scholar]

- National Medical Advisory Committee (1994). The Management of Anxiety and Insomnia. HMSO. [Google Scholar]

- Qaseem, A. , Kansagara, D. , Forciea, M. A. , Cooke, M. , & Denberg, T. D. , Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(2), 125–133. 10.7326/M15-2175. Epub 2016 May 3. PMID: 27136449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann, D. , Baglioni, C. , Bassetti, C. , Bjorvatn, B. , Dolenc Groselj, L. , Ellis, J. G. , Espie, C. A. , Garcia‐Borreguero, D. , Gjerstad, M. , Gonçalves, M. , Hertenstein, E. , Jansson‐Fröjmark, M. , Jennum, P. J. , Leger, D. , Nissen, C. , Parrino, L. , Paunio, T. , Pevernagie, D. , Verbraecken, J. , … Spiegelhalder, K. (2017). European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. Journal of Sleep Research, 26(6), 675–700. 10.1111/jsr.12594. Epub 2017 Sep 5 PMID: 28875581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sateia, M. J. , Buysse, D. J. , Krystal, A. D. , Neubauer, D. N. , & Heald, J. L. (2017). Clinical Practice Guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(2), 307–349. 10.5664/jcsm.6470. PMID: 27998379; PMCID: PMC5263087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. , Anderson, K. , Baldwin, D. , Dijk, D. J. , Espie, A. , Espie, C. , Gringras, P. , Krystal, A. , Nutt, D. , Selsick, H. , & Sharpley, A. (2019). British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus statement on evidence‐based treatment of insomnia, parasomnias and circadian rhythm disorders: An update. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 33(8), 923–947. 10.1177/0269881119855343. Epub 2019 Jul 4 PMID: 31271339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.