Abstract

Air ambulances can provide more rapid access to medical care than ground ambulances for rural, underserved, and hard to reach populations. However, the existing allocation of ambulance bases across metropolitan and rural areas is driven primarily by individual operator decisions rather than a health outcomes-based approach. This paper describes a framework for optimizing air ambulance services delivery based on healthcare demand and locational constraints to other modes of transportation. In particular, the paper highlights the need for combining data and how data can be used to identify locations where air ambulance services could be located based on impact. We utilize an information systems approach, applying linear programing models to identify the optimal base locations at the state and regional level. Two data driven use cases for the state of Virginia and New England demonstrate the application of our approach and underscore the importance of data interoperability in health transportation planning.

Introduction

Air ambulances serve over half a million patients a year and have gained greater importance in the healthcare landscape as rural hospitals continue to close1,2. Additionally, the current Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for rapid transportation of patients to medical care. In some rural areas, air ambulances are the only means of getting patients to trauma centers and other healthcare facilities within the “Golden Hour” after an event3. Helicopters, which account for over 70 percent of air ambulances, provide emergency scene response and interfacility transfers while fixed wing aircraft typically provide longer distance airport-to-airport transport2.

Concerns about equitable access to and high costs of air ambulance services have plagued emergency medical transportation providers for decades. Research shows that the existing allocation of ambulance bases across both metropolitan and rural areas is driven primarily by industry strategic decision-making and profit motive rather than maximizing the performance of the health-transportation system. Lack of competition is a particular problem, as two private equity firms operating helicopter air ambulances accounted for 64% of the Medicare market in 20174. In addition, this misalignment of incentives—contributing to suboptimal health outcomes, sky-rocketing costs for services, surprise medical bills, and documented disparities in access across urban and rural locations—motivates the need for a comprehensive approach to how this service is allocated.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that, in 2016, Medicare spent around $0.5 billion dollars on air ambulance payments5. In 2017, the median price charged nationally by air ambulance providers was $36,400 for helicopter transports and higher for other aircraft6. There are also reports of disparities in access, and of underserved areas7. Policy makers may find that disparities in access to air medical services are closely tied to other issues that make it difficult to address health outcomes directly. Provider costs are high and the increase in air ambulance fees in the National Fee Schedule is reported to encourage the profit-making incentives2. A large proportion of air ambulance trips are not covered by insurance, contributing to high patient costs6. Moreover, the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 limits federal and state legislation from regulating services, fees, and routes2. Until the recent passage of the 2020 COVID-19 Economic Relief Bill, there had been very limited regulatory or legislative action to address the cost of air medical services. While the recent legislation protects consumers from surprise bills when they seek emergency care and are transported by an air ambulance, it does not address continued issues such as misallocation of bases, redundant supply, high overall cost of care, and lack of coverage for non-emergency care8.

Given this regulatory gridlock and complexity of the air ambulance industry, part of the solution to improving air ambulance related health outcomes could be to incentivize ambulance providers to establish bases near areas where there is a medical need for rapid transport and constraints, or large distances required for accessing ground ambulances. However, there is not currently a data-driven, health-outcome-based framework for identifying the optimal air ambulance allocation in the U.S. Such a framework could help drive a more effective conversation around local, state, and national policy mechanisms to achieve the desired allocation, and provide decision-makers with tools to inform policy decisions and incentives to improve air ambulance access, health outcomes, and lower cost.

Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Public Release Case Number 21-2454. ©2021 The MITRE Corporation. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

In this paper we demonstrate a framework for optimizing the delivery of air ambulance services based on the healthcare demand and locational constraints to other modes of transportation. Identification of the optimal location of air ambulance bases is based on a wide variety of healthcare and transportation data, transportation demand modeling, geospatial analysis, and linear programming optimization models. Specifically, we use detailed event-level emergency medical services (EMS) data from the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) to identify the health and demographic drivers of air ambulance usage9. The information on demand drivers is combined with ZIP code-level data on chronic disease risk factors, health outcomes, and clinical preventive services from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to identify locations that are at relatively higher risk of requiring emergency transportation to reach healthcare facilities. This information is used to parameterize two linear programming models to optimize allocation of air ambulance bases.

Methodology

Base Locations

We identify the optimal location of air ambulance bases using an analysis of candidate air ambulance patients, as well as potential “supply nodes,” i.e., candidate locations for air ambulance bases. Candidate patients come from event-level emergency medical services (EMS) data to explore the key healthcare and demographic drivers of air ambulance usage, including but not limited to heart attacks, strokes, and various levels of trauma9. Subsequently, we use disease incidence and prevalence data to identify the populations that are at risk of these health events. Candidate air ambulance bases are based on the 3,436 hospital service areas (HSAs) identified by the Dartmouth Atlas Project10. Each hospital service area is a collection of ZIP codes containing one or more hospitals—with its exact boundaries defined by Medicare patient data.

We use the Maximal Covering Location Problem (MCLP) and the Maximal Expected Covering Location Problem (MEXCLP) to maximize the number of covered patients for a given number of air ambulance facilities. These models locate a limited number of bases in a configuration that maximizes the number of total covered patients. Within each local market, air ambulance providers are often flexible about exact base locations—in many cases opening, closing, and relocating bases over the long run. Proximity to patients is one consideration, and some providers open satellite bases as exurban areas grow—but cost (e.g., potential co-location or consolidation with other medical, public safety, local government, or aviation service facilities), local real estate conditions, and other operational needs (additional hangar space or better sleeping quarters) may dictate exact base locations. MCLP and MEXCLP allow for the application of an iterative modeling approach that can incorporate additional data and features to increase the sophistication, and fit, of the model to actual transportation practice11,12.

The modeling approach includes assumptions about the service area and availability of air ambulances at a rotor-wing base, to parameterize two linear programming models to optimize allocation of air ambulance bases. The MCLP model assumes that there are always aircraft and crew available to respond to potential calls. The MEXCLP relaxes this assumption, allowing for redundant coverage in the event of busy aircraft and crew, mechanical failure, illness, or inadequate staffing12. Within each hospital service area, we make the simplifying assumption that the geographic centroid of the HSA will be the only location considered for a potential air ambulance base. We make this assumption because it would be impractical to consider all existing, planned, or potential airports and medical facilities. We believe this simplifying assumption is realistic in most cases, as air ambulance bases are typically located near hospitals.

Conditions of Interest

In this paper we focus on heart attacks and strokes as key individual-level drivers of air ambulance usage. Subsequently, we identify population-level characteristics that contribute to high prevalence rates and incidence of these individual-level health risks. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) PLACES Survey (formerly known as the 500 Cities Project) provides detailed, zip-code- and population-level data on health outcomes, prevention, and unhealthy behaviors. Specifically, we use coronary heart disease among adults aged 18 years and above and stroke among adults aged 18 years and above as the key population-level determinants of air ambulance demand. This information is used to identify the number of potential candidates for air ambulance transports in each zip-code that are at risk of heart attacks and strokes. The fact that heart attack and stroke are incidence variables while cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a prevalence variable allowed us to use two types of burden of disease variables as example applications in our model. The use of these two conditions was used to implement versions of our model with the publicly available versions of the NEMSIS data we had available (see the Conclusion section for additional information about the limitations and generalizability of this approach).

Moreover, we identify utilization of air ambulance services through two additional data sets: CMS Medicare Part B Public Use Files (PUF) and an integrated electronic health records (EHR) / claims data set from Clarivate (previously Decision Resources Group a.k.a. DRG). The Medicare Part B PUF files show all utilization of air ambulance services provided for traditional Medicare beneficiaries under Medicare Part B. This data is aggregated at the provider (air ambulance company) level for 2012 – 2018. Air ambulance data includes the location of the service provider, which we used to determine where bases were located. The DRG data contains claims and EHR data for the state of MA for the years 2016-2019. This data includes claim level (patient charges) for 4 current procedure terminology (CPT) codes related to air ambulance utilization. These codes relate to all conditions, and were not limited to the two conditions, stroke and heart attack, used for the NEMSIS analysis.

Locales

In this paper, we show results for two data driven use cases at the state and regional level for Virginia and New England, respectively. We model three “busy fractions” using MEXCLP, p=0.0 (a special case that is equivalent to MCLP), 0.2, and 0.4. Assumptions of MEXCLP include a consistent busy fraction across bases, which is a simplification but certainly a more realistic one than the MCLP assumption that the air ambulances are always available. The higher the busy fraction, the more redundant coverage is prioritized by the MEXCLP approach.

Both the MCLP and MEXCLP models utilize Allagash13, an open-source spatial optimization library written in Python. The most recent version of Allagash only supports the Location Set Covering Problem (LSCP) and MCLP models. As such, we extend Allagash to support MEXCLP and test our implementation using a small-scale example from the original MEXCLP paper. Allagash then uses the linear programming package PuLP14 as an interface to the COIN-OR Branch-and-Cut (CBC) solver15. We retrieve the tile maps from the internet using the contextily package16 and plot the actual and modeled air ambulance base locations on these maps using GeoPandas GeoDataFrames (also known as geopandas.GeoDataFrame)17.

Data

Our technical approach to understand demand, costs, utilization, and other aspects of the ambulance market required understanding the overall air ambulance landscape within the U.S. We detail the multiple data sources needed to perform our analysis in this section. Table 1 summarizes the data sources utilized in this analysis.

Table 1.

Key Data Sources Used in Analysis and Optimization Framework Development

| Data set | Data Source | Data Contents |

|---|---|---|

| DRG2 MA data | Decision Resources Group | Clinical and claims data for all of MA |

| Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality | All payer hospital discharge data |

| National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) database | University of Utah and state EMS agencies | All reported EMS events for 47 states |

| National Provider Identifier (NPI) registry | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | Air ambulance provider data (office and/or base location, state(s) of licensure) |

| Homeland Infrastructure Foundation-Level Data (HIFLD Open Data) | Department of Homeland Security | Hospital and trauma center locations |

| The Atlas & Database of Air Medical Services | Association of Air Medical Services and CUBRC | Air ambulance base location data |

| Medicare Part B public use file (PUF) | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | Aggregated claims for Medicare beneficiaries |

Current access to air ambulance services

The Atlas & Database of Air Medical Services (ADAMS) provided the most comprehensive and systematic publicly available data on rotor- and fixed-wing air ambulance services, bases, and fleet volumes at the time of our initial analysis18. Due to coverage gaps in the current data, the database is currently offline. However, ADAMS remains the best and most comprehensive historical dataset on the air ambulance industry and has been incorporated into the Department of Homeland Security’s internal geographic information system (GIS) portal. According to 2019 ADAMS data, only about a third of the U.S. geographic area is within 15-20 minutes of a helicopter response. On the other hand, 86.2 percent of the U.S. population is within 15-20 minutes of response. While this is most of the U.S. population, this still leaves over 42 million people residing outside of response area18. The analysis of coverage based on ADAMS data, however, is based on geographic area and population density and does not account for the healthcare demand for air ambulance services.

To better understand the current state of air ambulance access and access disparities, we combined the ADAMS dataset with CMS’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) registry data to fill in gaps on air ambulance providers. In the NPI data, “healthcare providers acquire their unique 10-digit NPIs to identify themselves in a standard way throughout their industry.”19. We used this data as a starting point for initial geospatial analysis of access and availability of air ambulance services to understand the current state of access across the U.S. To get a more accurate picture of ambulance allocation and access we are currently analyzing data on additional factors, including fleet volumes across bases, incidence of disease, and other determinants of air ambulance usage and need beyond population density measures.

Demand for air ambulance services

We identify demand by using event-based data from the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) database and formally explore the drivers of utilization of air ambulance services1. The 2019 NEMSIS Public-Release Research Dataset includes 34,203,087 EMS activations collected from 10,062 agencies located in 47 states and territories. We identify individual-level determinants of air ambulance utilization using NEMSIS data on transport mode, medical conditions, type of destination facility, and patient demographics.

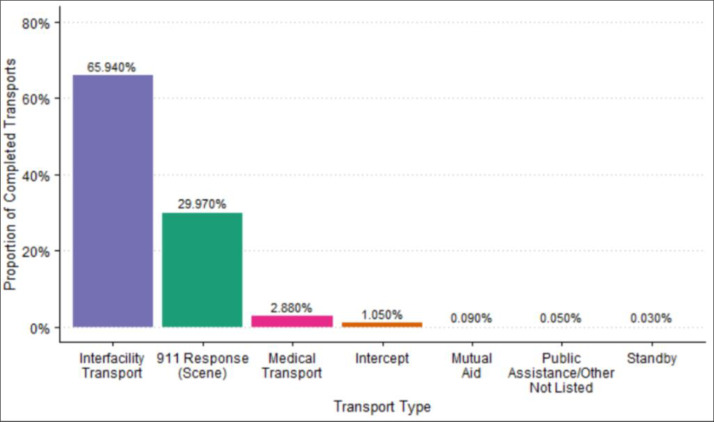

The majority of air ambulance trips are interfacility transports, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Types of Air Ambulance Transport from the 2019 NEMSIS Public-Release Research Dataset

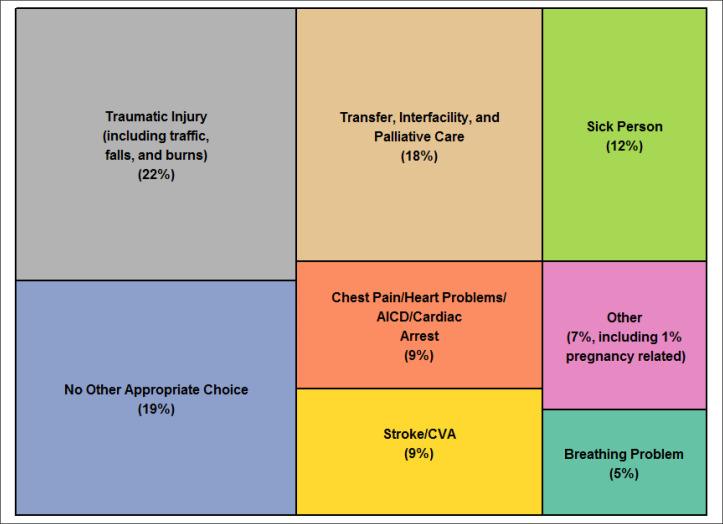

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the complaints reported by dispatch to the responding EMS unit. Close to one quarter of all complaints being responded to are for transport from one facility to another. Twenty nine percent of all complaints being reported do not provide additional medical information, shown here with “No Other Appropriate Choice” and “Sick Person”. The large portion of all calls that these categories represent demonstrates how little information EMS responders sometimes have when responding to a call.

Figure 2.

Complaint Reported by Dispatch to Responding Air Ambulance Unit from the 2019 NEMSIS Public-Release Research Dataset (due to rounding, percentages do not add up to 100%)

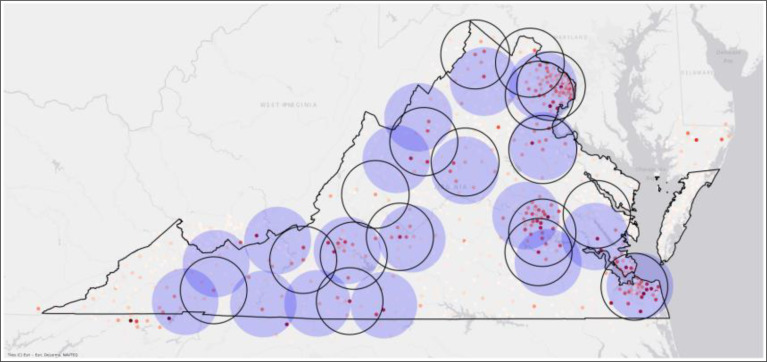

Results

The framework demonstrates a visualization showing the map of the service area, superimposed with one set of circles denoting the actual demand of such services, and another set of circles denoting the output of a model based on demand. We show those results for our two use cases, the state of Virginia and the New England region, below.

State of Virginia

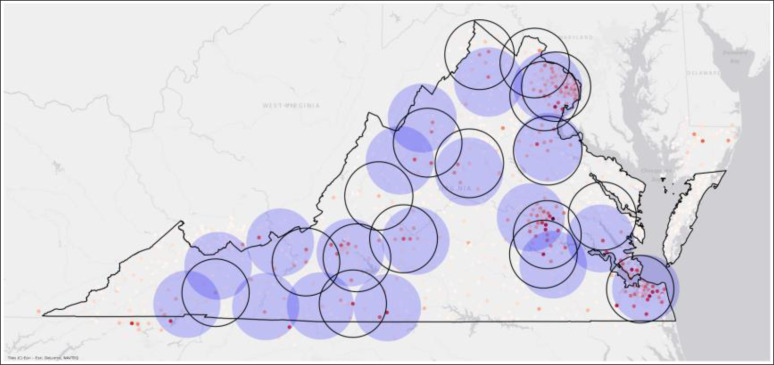

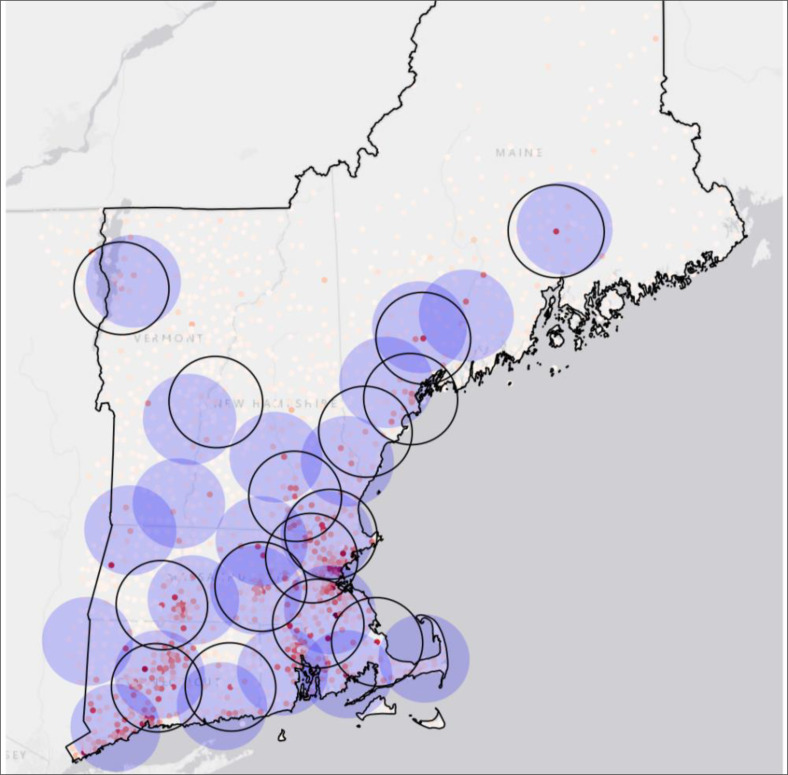

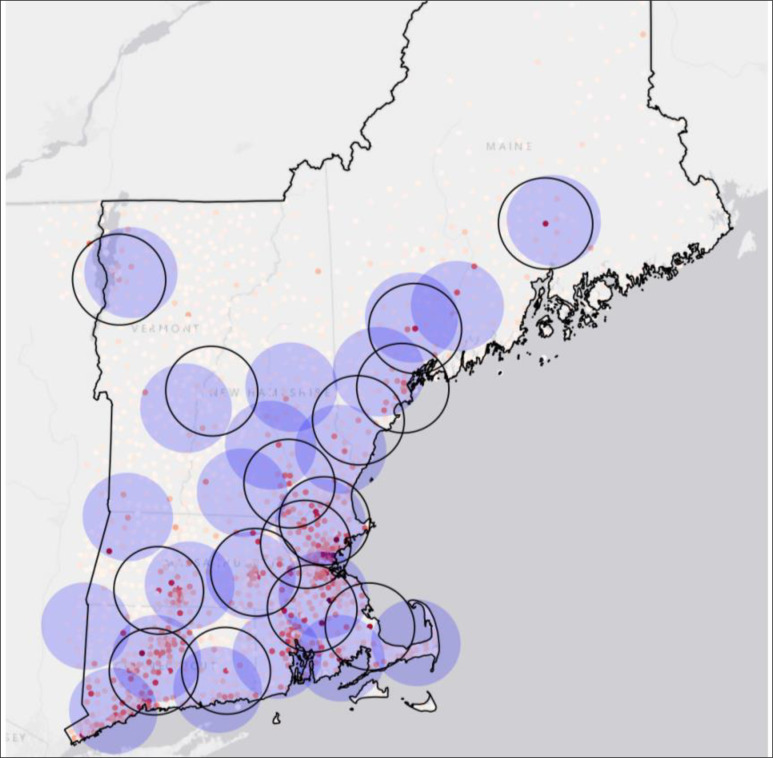

The two maps below show the coverage of current versus modeled air base locations in the state of Virginia. Modeled air base locations are depicted as shaded 20-nautical-mile flight circles, while actual base locations are unshaded (i.e., transparent circles bounded by a thin black outline).

Air base locations were modeled using stroke (Figure 3) and coronary heart disease (Figure 6) survey data from PLACES. In the two examples below, the stateside distribution of respondents with a history of stroke or heart disease was similar enough that the two model runs yielded an identical network of air ambulance bases.

Figure 3.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in Virginia versus modeled locations (MCLP model; 18 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; previously diagnosed stroke survivors from CDC PLACES used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

Figure 6.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in New England versus modeled locations (MEXCLP model; 22 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; previously diagnosed stroke survivors from CDC PLACES used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

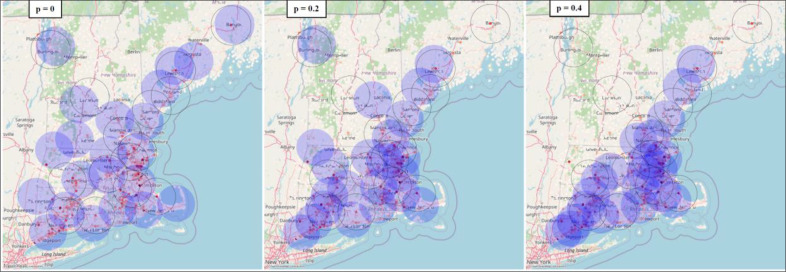

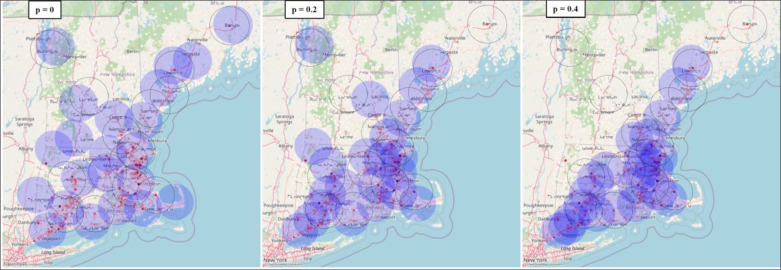

Regional model for New England

The two large maps below (Figure 5 and Figure 7) show MCLP model results for the New England region. Modeled base locations differ slightly—in the Keane, New Hampshire, region, for instance—due to difference in the geographic distribution of stroke and coronary heart disease respondents. To allow for backup coverage—optionally siting multiple bases in close proximity—we also modeled New England using the MEXCLP model, for both stroke (Figure 6) and coronary heart disease populations (Figure 8). Each of the MEXCLP figures depicts three potential scenarios for backup coverage—from left to right, scenarios with a busy fraction of p = 0.0, p = 0.2, and p = 0.4 are shown.

Figure 5.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in New England versus modeled locations (MCLP model; 22 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; previously diagnosed stroke survivors from CDC PLACES used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

Figure 7.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in New England versus modeled locations (MCLP model; 22 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; CDC PLACES respondents diagnosed with angina or coronary heart disease used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

Figure 8.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in New England versus modeled locations (MEXCLP model; 22 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; CDC PLACES respondents diagnosed with angina or coronary heart disease used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

As the busy fraction increases, it is necessary to locate additional bases throughout New England—especially in the more highly populated coastal regions. The number of bases is held constant at 22, which is the current number of bases available currently in this region, in these model runs. As a result, less populated areas are not allocated a base at the highest busy fractions—and additional bases would be necessary to provide coverage to all regions that have air ambulance service at present). Adding bases to increase coverage or removing bases to decrease costs are applications of our approach that are beyond the scope of this analysis.

Conclusions

In this paper, we demonstrated a simplified framework for optimizing air ambulance allocation based on a health outcomes focused approach. We expect this framework to serve as a tool to inform policy decisions that help achieve healthcare performance objectives. For example, the tool can be used by policy makers to identify high supply or duplication of air ambulance services and close access gaps across geographical regions based on location specific characteristics. Moreover, the tool can be used to install new air ambulance bases in underserved areas; close or consolidate existing bases that lead to redundant supply; reduce transport times to hospitals, improve survival; and reduce the magnitude of air ambulance costs. Moreover, state and local licensing and regulatory agencies can use the optimal location for air ambulance bases if they wish to ensure adequate coverage based on healthcare needs. This methodology can help determine the provision of licensing based on whether operators are meeting a community need.

The main limitations of our approach are the use of two specific clinical conditions, as well as two geographies (Virginia and New England) that may not be generalizable. The use of the two specific conditions may not be applicable to the wider range of conditions for which air ambulances may be used, particularly those with lower prevalence for which less data is available as well as patients who lack a defined diagnosis at the time of pick up. However, use of the detailed NEMSIS data set likely will allow for representing most of these patients in a future application. The use of Virginia and New England may not be generalizable to other regions or the country as a whole, especially for regions that have a lower count of bases or lack air ambulance bases all together. That may make this approach applicable only to larger regions or those that have sufficient population and healthcare capacity to make use of at least one air base. In general, a user requirement analysis and a user evaluation of the system are critical to design systems that are actually useful, usable, and adopted by end users. We have not implemented either as part of the current analysis, so both may be crucial next steps that are needed to adopt our tool in practice.

One other limitation of the approach is the limited validation of the modeling to date. We have validated the code (software) used to implement the model through independent assessments by two team members as well as a peer-review of our code by an expert in epidemiology and software development who is not a member of the research team. We also have validated the approach through application to the state of Massachusetts (results not shown and available upon request). We plan additional validation in the future both through the use of more detailed data and with a comparison of our results with a qualitative assessment of the air ambulance research literature that currently is in progress.

Detailed, data-driven analyses of these elements of the air ambulance industry are not yet available in the U.S. Our framework would help allocate air ambulance base locations based on healthcare demand and individual operator decisions (supply). This will require a comprehensive collection of data across transportation and healthcare domains. Analysis of this data would allow for the extension of our approach to the entire population within a given state or region, as well as future national extensions. Our framework can be used as a tool for decisionmakers when evaluating both the locations of existing base locations and identifying areas for new bases. This tool will provide additional information about who will be impacted by decisions like this, helping determine and forecast the effectiveness of future policies and supplier decisions. Additional information like this would be useful at the state- and local-level, to identify where base locations can best-service the populations with the greatest need, and for base operators, to better understand the expected number of patients and the clinical needs of those patients. Feasibility of adding base locations or removing bases ultimately would need to be assessed at the local level, using our tool as well as clinical and financial analyses of whether changes would adequately address patient need and cover the costs of operators (the authors performed a separate analysis of the financial feasibility of a new base not shown here and available upon request).

The existing study is based on public data on emergency events that does not provide the exact location of each incident. Future work arising from both this project and users of the tool we have produced may include specific analyses of the potential impacts of the changes implied by our model on policy and people (patients). Inclusion of data on location-specific EMS events and traffic and road network data to account for lack of access to trauma centers via ground ambulance would improve fidelity of the geospatial air ambulance demand analysis and allow for applications of the tool such as prioritizing underserved areas when optimizing air ambulance allocations.

Furthermore, ADAMS air ambulance base location data was extracted from annual reports, in PDF format, that the Association of Air Medical Services (AAMS) has discontinued. While AAMS will potentially replace ADAMS with a similar product, there is currently no successor to ADAMS, and any future updates will need to be collected using open-source intelligence, via sources such as CMS, insurance providers, the FAA, and crowdsourced aviation and helicopter websites.

Figures & Table

Figure 4.

Present-day fixed-wing base locations in Virginia versus modeled locations (MCLP model; 18 bases; 20 nautical mile coverage radius; CDC PLACES respondents diagnosed with angina or coronary heart disease used as candidate population; hospital service area centroids used as candidate air ambulance base locations)

References

- 1.The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research . Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2014. Rural Hospital Closures [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinsdale JG. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2018. Air Ambulance Regulations and Payments [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2018-12/i18-cms-report2.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newgard CD, Schmicker RH, Hedges JR, Trickett JP, Davis DP, Bulger EM, Aurderheide TP, et al. Emergency Medical Services Intervals and Survival in Trauma: Assessment of the 'Golden Hour' in A North American Prospective Cohort. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2010;55(3):235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler L, Hannick K, Lee S. Washington, DC: USC-Brookings Schaeffer on Health Policy; 2020. High air ambulance charges concentrated in private equity-owned carriers [Internet] Oct 13[cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/usc-brookings-schaeffer-on-health-policy/2020/10/13/high-air-ambulance-charges-concentrated-in-private-equity-owned-carriers/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.United States Government Accountability Office . Washington, DC: United States Government Accountability Office; 2019 March. Air Ambulance: Available Data Show Privately-Insured Patients Are at Financial Risk [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-292.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bluth R. NPR; 2019. Why Air Ambulance Bills Are Still Sky-High [Internet] Jun 14 [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/06/14/732174170/why-air-ambulance-bills-are-still-sky-high . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander MB. Rural Health Inequity and the Air Ambulance Abyss: Time to Try a Coordinated, All-Payer System. 2021;21(1) Wyoming Law Review. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appleby J. NPR; 2020. Congress Acts To Spare Consumers From Costly Surprise Medical Bills [Internet] Dec 22 [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/12/22/949047358/congress-acts-to-spare-consumers-from-costly-surprise-medical-bills . [Google Scholar]

- 9.NEMSIS Technical Assistance Center . Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah School of Medicine; 2019. NEMSIS Public Release Research Data Set v.3.4.0. ; 2020 Apr [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: www.nemsis.org . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care . Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College; Supplemental Data [Internet] [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://data.dartmouthatlas.org/supplemental/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Church R, ReVelle C. The Maximal Covering Location Problem. Papers of the Regional Science Association. 1974;32(1):101–118. Dec; [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daskin MS. A Maximum Expected Covering Location Model: Formulation, Properties, and Heuristic Solution. 17(1):48–70. Transp. Sci. 1983 Feb; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allagash Pulver A. 0.3.0 [Internet]. GitHub [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://apulverizer.github.io/allagash/

- 14.Roy JS, Mitchell SA, Duquesne C, Peschiera F. Optimization with PuLP [Internet]. GitHub [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://coin-or.github.io/pulp/

- 15.Forrest JJ, Hafer L, Gonalves JP, Santos JG, Brito SS. Coin-OR branch and cut (Cbc) [Internet]. GitHub [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://github.com/coin-or/Cbc .

- 16.Arribas-Bel D. contextily: context geo tiles in Python. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://contextily.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- 17.GeoPandas developers GeoPandas. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://geopandas.org/en/stable/

- 18.The Association of Air Medical Services Atlas & Database of Air Medical Services 17th Annual Edition. [Internet]. Alexandria, VA; 2019 [cited 2021 Aug 13]

- 19.NPPES NPI Registry . Baltimore, MD: U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Search NPI Records [Internet]. [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available from: https://npiregistry.cms.hhs.gov/ [Google Scholar]