Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer is highly prevalent and impacts profoundly on patients' quality of life, leading to a range of supportive care needs.

Methods

An updated systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative data using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA) reporting guidelines, to explore prostate cancer patients' experience of, and need for, supportive care. Five databases (Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, Emcare and ASSIA) were searched; extracted data were synthesised using Corbin and Strauss's ‘Three Lines of Work’ framework.

Results

Searches identified 2091 citations, of which 105 were included. Overarching themes emerged under the headings of illness, everyday life and biographical work. Illness work needs include consistency and continuity of information, tailored to ethnicity, age and sexual orientation. Biographical work focused on a desire to preserve identity in the context of damaging sexual side effects. Everyday life needs centred around exercise and diet support and supportive relationships with partners and peers. Work‐related issues were highlighted specifically by younger patients, whereas gay and bisexual men emphasised a lack of specialised support.

Conclusion

While demonstrating some overarching needs common to most patients with prostate cancer, this review offers novel insight into the unique experiences and needs of men of different demographic backgrounds, which will enable clinicians to deliver individually tailored supportive care.

Keywords: body image, patient information, prostate cancer, psychological, quality of life, supportive care

1. BACKGROUND

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most commonly diagnosed male cancer worldwide (Bray et al., 2018) and recently became the most commonly diagnosed cancer overall in England (Prostate Cancer UK, 2020). New management options for these patients are emerging, with novel medical and surgical therapies becoming available for localised and metastatic disease in recent years. Despite this, some men with PCa endure a long and challenging illness course. Debilitating treatment side effects such as urinary incontinence (UI) and sexual dysfunction often persist through survivorship (Roth et al., 2008). These factors combined lead to a complex range of psychosocial, psychosexual, and informational needs and call for comprehensive, multidisciplinary supportive care. A 2013 study (Cockle‐Hearne et al., 2013) of 1001 men living with PCa in seven European countries reported that 81% of these men had unmet supportive care needs, demonstrating a requirement for enhanced understanding and management of these needs.

Current guidelines, while incorporating supportive care as an important aspect of the management of PCa, leave some issues unaddressed. In particular, current recommendations (Cornford et al., 2021; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019) do not fully consider the diverse and highly individualised supportive care needs of men of different ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientations, ages and disease stages, which may lead to neglect of these men's individual psychosocial, psychosexual and informational needs. Moreover, a steadily increasing incidence of PCa in many Asian and African countries (Chen et al., 2014; Seraphin et al., 2021) calls for authoritative region‐specific guidance on supportive care in PCa. Emergent information‐seeking behaviours, such as the use of online resources for informational and decision support, are also becoming widespread; however, little is currently known about men's perspectives on the utility of these tools in meeting their supportive care needs.

A previous review (King et al., 2015) addressed the topic of supportive care needs in PCa. However, substantial changes in the clinical management of PCa (Powers et al., 2020), patients' increasing use of the Internet as both an informational and supportive resource and a vast increase in primary literature in this area since the early 2010s all suggest the need for an updated perspective. Over half of the work identified by our literature search was published since 2013, reinforcing the need for a contemporary synthesis that considers recent changes to the experiences of men with PCa. The present review offers a synthesis of the existing qualitative research on supportive care in PCa since 2013 and provides new insights into the unique supportive needs of men with PCa, as well as highlighting key areas for improvement in clinical practice.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy and inclusion criteria

A qualitative systematic review and synthesis were conducted according to the PRISMA reporting guidelines (Page et al., 2021). Five databases (Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, Emcare and ASSIA) were searched in June 2020 (Table 1). As this review was performed to update previous work, papers published between July 2013 and June 2020 were included. Combinations of the terms ‘prostatic neoplasms’, ‘PCa’, ‘prostatic tumour’ and ‘prostatic carcinoma’ were used alongside a commonly used qualitative search filter (University of Texas School of Public Health, n.d.) to identify appropriate studies. Inclusion criteria were as follows: studies using qualitative methods where participants were aged 18 and over and had been diagnosed with PCa, which reported new primary data on PCa patient needs or experiences from which those needs could be inferred, separately from those of other patient groups and outcomes, in peer‐reviewed papers written in English (meta‐analyses and reviews were excluded) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Representative MEDLINE search strategy used to identify studies for inclusion

| 1. Prostatic Neoplasms/ |

| 2. (prostat* and cancer*).m_titl. |

| 3. (prostat* adj4 cancer*).tw. |

| 4. (prostat* adj4 neoplas*).tw. |

| 5. (prostat* adj4 carcinoma*).tw. |

| 6. (prostat* adj4 tumo?r*).tw. |

| 7. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 |

| 8. (((“semi‐structured” or semistructured or unstructured or informal or “in‐depth” or indepth or “face‐to‐face” or structured or guide) adj3 (interview* or discussion* or questionnaire*))).ti,ab. or (focus group* or qualitative or ethnograph* or fieldwork or “field work” or “key informant”).ti,ab. or interviews as topic/ or focus groups/or narration/or qualitative research/ |

| 9. 7 and 8 |

TABLE 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used in this review

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

|

| Concept |

|

|

| Evidence sources |

|

|

2.2. Study selection

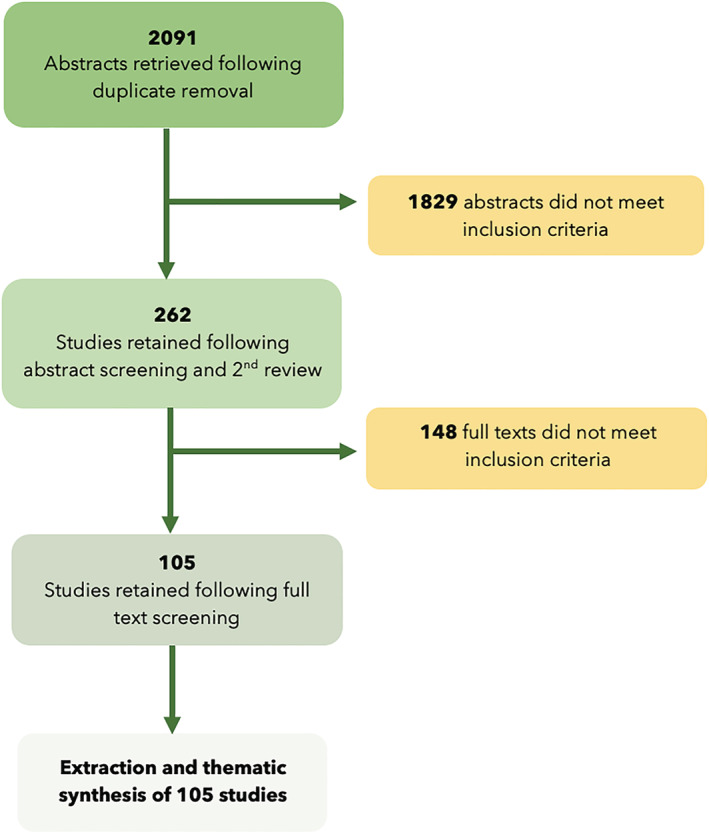

After removal of duplicate results, 2091 abstracts were retrieved. These were initially screened against inclusion criteria by a single investigator (JP). A second investigator (PS) independently verified 10% of the screened abstracts for concordance. A third reviewer (EM) was available to resolve disagreements on individual items. A total of 262 abstracts were subjected to full‐text review, and 105 full‐text articles were retained for data extraction and synthesis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flowchart

2.3. Data extraction and thematic synthesis

A single investigator (JP) extracted relevant data from included papers, such as year of publication, first author, country, aim of study, sample size, data collection method, theoretical approach, stage of cancer, treatment stage or type, age range of participants, ethnicity and sexual orientation of participants, relationship status of participants and identified or inferred outcomes relating to supportive care needs. Thematic synthesis was performed according to methods described by Thomas and Harden (Thomas & Harden, 2008). Descriptive themes were developed and classified according to Corbin and Strauss' ‘Three Lines of Work’ framework (Corbin & Strauss, 1988), with ‘work’ referring to productive mental and physical actions undertaken by patients in an effort to meet their various needs. Use of this framework enables characterisation of men's biographical work (influences on wider life course and identity), illness management work (relating to informational, symptom‐related and treatment decision making), everyday life work (relating to lifestyle, family and employment) and associated need in each area. Descriptive theme development was facilitated by systematic coding of passages and quotes within each of the included papers, and consensus on themes was achieved by the three reviewers. Relevant analytical themes were then developed by the reviewers in order to offer pragmatic recommendations for future practice in supportive care.

2.4. Critical appraisal

The formal use of a critical appraisal tool was not deemed appropriate for this study, due to the holistic and qualitative nature of the review topic and the requirement for included studies to be peer reviewed. Demographic data, data collection methodology, synthesis methodology and participant demographics were extracted and are reported in supporting information Table S1.

3. RESULTS

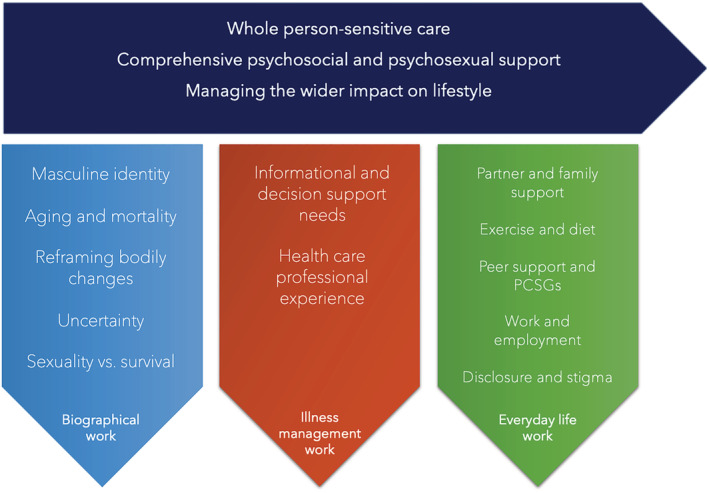

A total of 105 qualitative articles were included, originating from the UK (29), Australia (20), the USA (28), Canada (10), Sweden (3), Brazil, Italy, Denmark, The Netherlands, Ireland, Finland, New Zealand, Japan, China, France and South Africa. The characteristics of included studies are listed in Table 3. Thirteen descriptive themes were developed by the reviewers and retrospectively categorised using the ‘Three lines of work’ framework by Corbin and Strauss, comprising biographical work and identity, illness management, and everyday life work (Table 3). Three overarching themes were then developed to summarise the 13 descriptive themes: whole person‐sensitive care, comprehensive psychosocial and psychosexual support and managing the wider impact on lifestyle (Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Descriptive themes identified in this review

| Biographical work | Illness management work | Everyday life work |

|---|---|---|

| Masculine identity | Informational and decision support needs | Partner and family support |

| Aging and mortality | Health care provider experience | Exercise and diet |

| Reframing bodily changes |

Peer support and prostate cancer support groups |

|

| Uncertainty | Work and employment | |

| Survival versus quality of life | Disclosure and stigma |

FIGURE 2.

Diagram showing identified descriptive and overarching themes

3.1. Descriptive themes

3.1.1. Biographical work and identity

Biographical work is defined by Corbin and Strauss as the work involved in ‘defining and maintaining an identity’ (Corbin & Strauss, 1988). Biographical needs encompassed men's experiences of coming to terms with a PCa diagnosis, developing mechanisms of coping and framing their illness within their wider life course.

3.1.2. Masculine identity

Men's masculine identities were important in their perception of their illness experience. (Araújo et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2018; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020; Ettridge et al., 2017; Keogh et al., 2013; Kinnaird & Stewart‐Lord, 2020; Kirkman et al., 2017; Medina‐Perucha et al., 2017; Wall et al., 2013; Yu Ko et al., 2018, 2019). Several papers noted the significance of men's responsibilities as a father, worker or husband and how an inability to perform these roles as a result of treatment side effects or the disease itself adversely impacted on masculine identity (Keogh et al., 2013; Kinnaird & Stewart‐Lord, 2020; Levy & Cartwright, 2015; Yu Ko et al., 2018).

|

‘A male is [expected to be] physically able. You're strong, you can do things. I've got three daughters and if something physical [needs doing] in our house, you do it. I still can, but it really drops off. So that's what I am talking about, the essence of being male.’ ‐ Participant undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), (Keogh et al., 2013) |

Some studies highlighted the role of masculine ideals in obstructing men's medical and emotional help‐seeking, with men often feeling pressured to maintain ‘traditional’ masculine values of stoicism, independence and indifference. This can result in a lack of emotional support and/or a delay in addressing damaging treatment side effects (Forbat et al., 2013; Kirkman et al., 2017; Medina‐Perucha et al., 2017). In older men, masculine gender norms were noted as a significant barrier to medical help‐seeking and this was linked to an increased tendency to minimise, or attempt to self‐manage, troublesome symptoms (Medina‐Perucha et al., 2017). Men in one study (Yu Ko et al., 2019) described the determination of some to preserve their masculine identity:

| “Most men described efforts at maintaining their masculine worth by framing the embodiment of the sick role as strategic and necessary to ensure recovery. In this regard, one participant exemplified how men linked embodying the sick role with masculine worth by framing convalescence as a “test” of “strength” in managing another challenging situation in life, while another man shared his determination to overcome postsurgical complications to resume work and meet his financial responsibilities: “I did not give up. I kept telling myself: ‘I cannot let it win.’” |

3.1.3. Ageing and mortality

Ageing and mortality were recurring themes across several papers (Chambers et al., 2015; Er et al., 2017; Ettridge et al., 2017; Menichetti et al., 2019; van Ee et al., 2018). Some men described a moment of insight upon being diagnosed with a disease associated with old age, where the realities of ageing became evident (Chambers et al., 2015; Ettridge et al., 2017; van Ee et al., 2018). Other men with established low‐risk PCa described age as a barrier to strenuous physical activity and exercise‐based interventions (Er et al., 2017; Menichetti et al., 2019). Several men approached age as a challenge to their sense of youth and vitality:

|

‘… even though I'm 64, I still retain vestiges of a teenage male sense of invincibility … so this is kind of a reminder that I'm human … So that was a blow to my ego if nothing else …’ ‐ Participant, 64 years (Ettridge et al., 2017) |

3.1.4. Reframing and accepting bodily changes

Several studies highlighted the tendency of some men, and their partners, to reframe damaging physical changes in the context of their advancing age (Chambers et al., 2018; Ettridge et al., 2017; Green, 2019; Hamilton et al., 2014; Jägervall et al., 2019; Kirkman et al., 2017; Laursen, 2016; McSorley et al., 2013; Owens et al., 2019; Ussher et al., 2016; Wassersug et al., 2016; Wennick et al., 2017). Changes to sexual function, such as erectile dysfunction (ED), were most frequently subject to reframing by men and their partners. There was often a general sense of resignation, or inevitability, that sexual function was a natural and necessary casualty of ageing—particularly in the context of a PCa diagnosis:

| Well, I figured … that if I had not [done] it [received PrCA treatment] it's a possibility my life would have been cut short. I knew that my sexual part of it would probably be [affected] because I'm old anyways. ‐ Participant, 73 years (Owens et al., 2019) |

This often formed a basis for substantial changes to men's relationship with their partners, with multiple papers describing the efforts of men and partners to find nonsexual means of expressing intimacy. Some participants (Chambers et al., 2018; Hamilton et al., 2014; Laursen, 2016; Wennick et al., 2017) described not only an increase in the perceived relative importance of emotional intimacy within the relationship but also of time spent on recreational activities and with friends and family. One study (Ettridge et al., 2017) described this process as one of acceptance, most commonly seen in participants ‘less affected’ by their diagnosis, and another (Wennick et al., 2017) notes one participant's experience of his relationship with his partner ‘transform[ing] into a friendship’. Another (Ussher et al., 2016) described a participant more consciously choosing to reframe bodily changes in the context of their age. In contrast, other authors (Chambers et al., 2018; Green, 2019) described reframing as a mechanism of coping, associated with ‘distress’ and a desire to ‘play down’ the impact of side effects—suggesting that in some men this behaviour may be associated with unmet need. UI, however, was met with greater distress by some men, who did not view UI as an expected experience—particularly during middle age—and one less able to be reframed (Green, 2019).

3.1.5. Uncertainty

While much of men's uncertainty originated from a lack of clear information or support from health care professionals (HCPs) regarding side effects, prognosis or illness progression, a more generalised uncertainty about the future was a key source of anxiety for some men. Feelings of uncertainty were expressed in relation to men's illness status, quality of life and prognosis (Chambers et al., 2018; Hillen et al., 2017; Levy & Cartwright, 2015; Pietilä et al., 2018). Living with the uncertainty of imminent death had profound effects on men's perception of their life course and expectations of their life as a whole, with men at an advanced disease stage reporting feelings of a loss of control, existential distress and unease at not being able to plan for the future (Levy & Cartwright, 2015).

A participant in one study (Hillen et al., 2017) describes the value of hope in dealing with uncertainty:

|

Q31: I: And how can your physicians help you deal with the uncertainties? R: They can if they say something like: there's four medicines coming out this year, or there may be some immunotherapies that will extend your life beyond seven years. Any chance of hope is very good […], any advancement in cancer treatment to me is a good sign. For instance, they now have an immunotherapy for lung cancer. That's a good sign you know. There's been studies of cancer, prostate cancer in mice that they can totally eliminate. So I find these things give me hope. And that's what keeps my attitude positive. ‐ Participant, 53 years, advanced (Hillen et al., 2017) |

While some men wanted to make the ‘unknowable’ known in terms of prognosis and quality of life in order to prepare and feel psychologically in control, others preferred to ‘live in the moment’ and focus on their day‐to‐day‐life (Chambers et al., 2018). Seeking certainty was found by some men to be challenging without a temporal point of reference for recovery or deterioration, and these men found that delineating periods for these processes to occur were effective in helping them develop certainty and a sense of control (Pietilä et al., 2018).

3.1.6. A trade off: Survival versus quality of life

There was significant variation in men's preference for prioritising quality of life versus chances of survival. Some men perceived their situation as being transactional—that survival came at the cost of a reduced quality of life and that survival was more important than the maintenance of sexual function (Le et al., 2016; Owens et al., 2019; Speer et al., 2017; Wennick et al., 2017). For example:

|

“The urinary incontinence was probably the biggest concern that I had, followed by the sexual side effects. But bottom line is, having surgery, being alive, being viable—Overrode all of those concerns… If the surgery is a success, and I'm going to live, then I'll deal with the other issues.” ‐ Participant (Le et al., 2016) |

Two studies examining experiences in UK African and Afro‐Caribbean men with PCa highlighted the relative importance of maintaining sexual potency for some men and that loss of sexual function was not a price they were necessarily willing to pay for longevity (Anderson et al., 2013; Margariti et al., 2019).

3.1.7. Illness‐related work

Illness‐related work, as described by Corbin and Strauss, comprises areas such as crisis prevention and management, symptom management and diagnostic‐related work (Corbin & Strauss, 1988).

Participants across the included studies described a burden of need in many of these areas, in relation to specific aspects of their illness management both within and outside of healthcare settings.

3.1.8. Informational and decision support needs

The informational and decision support needs of study participants were varied and often highly individualised. Recurrent themes were identified across the included studies, including concerns over decision making, quantity and quality of information provided, the reliability of the Internet and other sources of information, informational needs during active surveillance (AS), individualised information and assessing risk of morbidity and mortality.

Many men, across a variety of settings, expressed concerns that the amount of information provided by their physicians was insufficient to enable effective treatment decision‐making (Akakura et al., 2020; Appleton et al., 2019; Catt et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2018; Primeau et al., 2017; Schildmeijer et al., 2019). In one study of men with PCa in the Asia‐Pacific region, participants in Japan and China reported low levels of basic understanding of their condition and a perception that they had not been provided sufficient information by their physicians (Akakura et al., 2020). Many men were dismayed that their physicians focused on cancer control but did not sufficiently discuss sexual dysfunction during the treatment decision‐making process, leading to surprise when sexual dysfunction did ultimately occur (Albaugh et al., 2017; Kinnaird & Stewart‐Lord, 2020; Mehta et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2015; Rose et al., 2016).

There was significant variation on taking responsibility for decision making. Some men preferred to be active participants in the decision making process and complained of a lack of shared decision making when taking key treatment decisions (Akakura et al., 2020; Paterson et al., 2019). However, there were many who felt disempowered by taking on the responsibility of decision making, contributing to feelings of being unsupported (Akakura et al., 2020; Fitch et al., 2017; Han et al., 2013; Paterson et al., 2019; Thera et al., 2018; van Ee et al., 2018; Wagland et al., 2019; Zanchetta et al., 2016). Monitoring progression and making relevant decisions based on this data were a concern for several men. One study attributed significant feelings of uncertainty to the lack of predefined thresholds for prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels—with men sometimes having to take responsibility for making treatment decisions based on their own heuristic milestones (Han et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2014).

Men also discussed a need to seek their own information independently in order to inform decision‐making. The Internet was frequently reported as a source of valuable knowledge (Chauhan et al., 2018; Fitch et al., 2017; Hogden et al., 2019; Kassianos et al., 2015; Le et al., 2016; O'Callaghan et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2016) and several studies highlighted potential motivations for the use of Internet resources: Some men reported searching the Internet for information because of a perceived need to actively seek information in the process of making an informed decision, whereas others felt that information provided by their HCPs was incomplete or needed confirmation. Experiences with the use of these resources were varied. Although there was no shortage of relevant information available online, managing, verifying and interpreting this information in the context of their condition presented a significant burden:

|

“Yes, dietary advice is available but not specifically for prostate cancer … there are a lot of different sources aren't there? I mean, there's a lot … published sources are often a lot nowadays. “ ‐ Participant (Kassianos et al., 2015) |

Some participants from minority groups struggled to access individualised information about mortality risk, treatment options and treatment side effects. A study of older men highlighted difficulties in finding reliable information distinguishing ailments of old age and comorbid conditions from those caused by PCa and its treatment, as well as a general need for physicians to take more time to confer important information when treating geriatric patients with PCa (van Ee et al., 2018). Some gay and bisexual study participants reported being unable to access specialist information on the implications of PCa in the context of their sexuality, with some turning to the Internet for this purpose (Doran et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2015).

|

“I got all this information that would cover everybody that ever had prostate cancer, but it was not specific to me.” ‐ Participant, 62 years (Lee et al., 2015) |

Several studies reported unique informational and decision support needs for men on AS (Anderson et al., 2013; Fitch et al., 2017, 2020; Le et al., 2016; Loeb et al., 2018; Mallapareddi et al., 2016; O'Callaghan et al., 2014; Seaman et al., 2019). Men diagnosed with low‐risk PCa described the emotional weight of the decision to undergo AS or commence treatment and how the information provided to them by HCPs was rarely empowering enough to make an informed decision. Some men, in an effort to supplement this information, sought information from a variety of sources—including support groups or friends and family with experience of cancer (Le et al., 2016). Disease status and quality of life were emphasised as vital areas of informational need for patients seeking to make a decision about AS in one study, with participants suggesting that the ideal decision support process should allow time for tailored discussion and reflection (Fitch et al., 2017). Meanwhile, some men were resolute in their decision to pursue treatment over AS, placing less weight on the provided information in favour of their own assessment of the situation:

|

“I'm not a chance taker. I do not like to gamble. So I could have gone active surveillance, but how long do you go active surveillance, something could've happened.” ‐ Participant, 68 years (Owens et al., 2019) |

3.1.9. Experience with healthcare professionals

Men's experiences with HCPs were central to their illness journey. Common to many men's accounts were ideas surrounding trust in HCPs, individualised care, navigating the health care system, continuity of care and a perceived lack of effective psychosocial or psychosexual support.

Many men spoke about the importance of having a high level of trust in their HCPs (Er et al., 2017; Fitch et al., 2017; Hanly et al., 2014; Mader et al., 2017; O'Callaghan et al., 2014; Odedina et al., 2017; Owens et al., 2019; Zanchetta et al., 2016). The majority of opinions were positive, with men expressing trust in their physicians to make the right decisions for them:

|

“He just sat down, talked to me and gave me options, told me what was best and what I could do. And he also recommended if I wanted to get a second opinion, but I said no. I feel as though you are—I trust you. That is another word, trust. You have got to trust the doc.” ‐ participant (Jiang et al., 2017) |

However, participants in two studies considering the experiences of minority groups (Mallapareddi et al., 2016; Margariti et al., 2019)—African American and UK Afro‐Caribbean men respectively—reported feelings of mistrust for their physicians and the health care system, with some raising concerns that a lack of knowledge on the part of physicians regarding the increased risk of PCa in Black men might lead to bias and discrimination.

Men valued HCPs who were sensitive to their concerns and gave them ample opportunity to ask questions, particularly in the context of having to raise sensitive topics or areas of vulnerability. (Appleton et al., 2019; Hanly et al., 2014; van Ee et al., 2018; Zanchetta et al., 2016). For many, a high level of importance was placed not only on the integrity of the patient‐HCP partnership but also on the choice of specialist. Some men felt reassured by specialists who were reputable, experienced and contactable, whereas other more ‘passive’ patients held little preference (Jiang et al., 2017; O'Callaghan et al., 2014).

Many studies raised issues surrounding men's journeys through the health care system. Some studies describing feelings of being ‘devalued’ or ‘sidestepped’ by the health care system, and of ‘powerlessness’ and ‘isolation’ within the system (Chambers et al., 2018; Schildmeijer et al., 2019; Wennick et al., 2017). Men relayed concerns about having limited time in consultation with their HCP and in some cases a lack of access to specialist nurses (Catt et al., 2019; Paterson, et al., 2019). However, when specialist nurses were accessible, they were highly valued, with men reporting that they provided reassurance, understanding and a sense of hope that was otherwise absent (Hanly et al., 2014; Thera et al., 2018). Wider issues around continuity and consistency of care were also evident. Participants described poor consistency of information between professionals at the same hospital (Catt et al., 2019; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020) and also how seeing a different specialist on every visit led to a reluctance to discuss sensitive topics such as sexual health (Phahlamohlaka et al., 2018). Discharge to primary and community care also posed problems, with some receiving fragmented psychological and psychosexual support and survivorship care following discharge (Ettridge et al., 2017; Paterson et al., 2019; Wennick et al., 2017). Some men reported a lack of clarity about what discharge actually meant and about the ability of nonspecialists to address persistent health worries:

|

“Well, it's (discharge) a very common phrase that they use, and they mean that “we have done basically what we can, you had your operation, and you had your radiotherapy and now we will discharge you back to your GP” … and you have got to make your own conclusion what the GP is all about.” ‐ Participant (Margariti et al., 2019). “It's a little kind of, look, well you know I've cured you of the cancer so that's the big job, you know.” ‐ Participant (Ettridge et al., 2017) I spent a bit more time with them (hospital specialists) and I explained more things in more depth so when I did not have the answers from GPs or I felt that I wasn't given enough information (…) because of the consultant's expertise who is specialised especially in erectile dysfunction, that was his speciality whereas you get a GP who looks at everything and they are not specialised in that particular area. ‐ Participant (Margariti et al., 2019) |

Gay and bisexual men (GBM) related several concerns about their interactions with HCPs. A particular worry was disclosing their sexuality to specialists, with some men feeling let down by negative or disinterested reactions to their disclosure of sexuality (Doran et al., 2018; Hoyt et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2016). Other men described a lack of understanding on the part of their physicians and a failure to address their concerns about side effects in the context of their sexuality (Doran et al., 2018; Hoyt et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2015; McConkey & Holborn, 2018; Mehta et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2019; Rose, Ussher, & Perz, 2016; Speer et al., 2017).

Participants generally felt that the amount of psychosocial and psychosexual support provided could be improved. Men expressed fears and worries surrounding their families, relationships, the damaging nature of side effects, risk of recurrence and financial problems that often went unaddressed by their HCPs and contributed to feelings of isolation (Catt et al., 2019; Dunn et al., 2017; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2015; Margariti et al., 2019; Matheson et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2019; Paterson et al., 2017; Paterson et al., 2019).

3.2. Everyday life work

Men experienced significant changes to their everyday lives as a result of receiving a PCa diagnosis. Many participants underwent drastic alterations to their social lives, romantic relationships, exercise and diet, employment and family responsibilities. These changes were usually either made to mitigate disease and treatment side effects or due to their own conscious efforts to make lifestyle changes following diagnosis and through survivorship.

3.3. Partner, friend and family support

Many participants described the importance of partners, friends and family as key sources of informal practical and emotional support (Albaugh et al., 2017; Appleton et al., 2014; Catt et al., 2019; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020; Ettridge et al., 2017; Hamilton et al., 2014; Hanly et al., 2014; Imm et al., 2017; Maharaj & Kazanjian, 2019; McSorley et al., 2013; Nelson et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2019; O'Callaghan et al., 2014; Oliffe et al., 2014; Schildmeijer et al., 2019; Zanchetta et al., 2016). Partners were valued sources of instrumental support for men—for example, assisting with travel to and from medical appointments or by taking on a greater burden of household work when men were recovering from surgery or radiotherapy. Emotional and psychological support from partners was highly valued by men, sometimes even negating a need for specialist support:

|

“So yeah, but I have not had that support [from a counsellor or helpline]. I think my wife has been a good support for me. And the friends I've got that have been through the same experiences, is all the support I've needed I think.” ‐ Participant, 50 years (Ettridge et al., 2017) |

However, instrumental and emotional support for partners acting as informal carers was rarely discussed, with some participants suggesting a need for increased provision in this area (Doran et al., 2018; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020; Schildmeijer et al., 2019). Some GBM participants, in contrast, typically relied on friends and family to provide social support (Capistrant et al., 2016; McConkey & Holborn, 2018).

3.3.1. PCa support groups and peer support

Support and advice from peers with experience of PCa were valued by men. Peer support was accessed either through informal means, such as existing friendships with survivors and other patients at the hospital (Kirkman et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2016), or organised prostate cancer support groups (PCSGs) (Albaugh et al., 2017; Capistrant et al., 2016; Chambers et al., 2018; Chauhan et al., 2018; Dunn, Ralph et al., 2020; Ettridge et al., 2017; Green, 2019; Hamilton et al., 2014; Hanly et al., 2014; Hoyt et al., 2017; Imm et al., 2017; Mader et al., 2017; Mehta et al., 2019). While some men were sceptical about the benefits of sharing details of their condition (Ettridge et al., 2017; Oliffe et al., 2014), men who attended generally felt positive about these groups. Men often derived benefits such as a sense of camaraderie, hope and empowerment and a chance to gain reliable first‐hand knowledge and practical advice about the management of their condition. Some GBM and younger participants gained less value from these groups, believing them to be more tailored to older, married, heterosexual men and therefore a less useful source of information and support (Doran et al., 2018; McConkey & Holborn, 2018).

3.3.2. Diet and exercise

Many men at a variety of disease stages reported experiencing significant benefits in physical and mental health after engaging in structured exercise and improving their diet (Anderson et al., 2013; Coa et al., 2015; Er et al., 2017; Gentili et al., 2019; Kassianos et al., 2015; Keogh et al., 2013; Loeb et al., 2018; O'Shaughnessy et al., 2015; Sheill et al., 2017; van Ee et al., 2018; Wright‐St Clair et al., 2013). However, participants cited several barriers to engaging in physical activity. Many of these obstacles were not specific to PCa, such as fear of negative evaluation, lack of access to support or equipment or being short of time (Er et al., 2017; Gentili et al., 2019; McIntosh et al., 2019). Other men reported that treatment side effects specifically made physical activity difficult:

|

“[My] biggest barrier was that incontinence thing … going to the gym … and having an accident that was kind of detrimental to going back. I'm not going to lie that was the biggest problem, having an accident.” ‐ Participant (Williams et al., 2016) |

3.4. Work and employment

A diagnosis of PCa often had profound effects on men's ability to work, particularly among younger men (Appleton et al., 2014; Burbridge et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2015; Maharaj & Kazanjian, 2019; Paterson et al., 2019; Yu Ko et al., 2018, 2019). Men experiencing fatigue and a general worsening of health often struggled to perform at work, and some participants were concerned about not appearing as productive as their co‐workers (Yu Ko et al., 2018, 2019). Other men found it difficult to fit work around a demanding schedule of medical commitments:

|

I'm on shifts but I arranged with work so I could go in and stay on the morning shifts so I would go in to work for 6 o'clock, finish at 10 o'clock, come home get changed go to [the hospital ] … and have the treatment. ‐ Participant (Appleton et al., 2014) So and then of course the next thing is oh crikey, what am I going to do for work? I suppose, because one thing, you are told at your age, the best option was to have the prostate removed by surgery and you have up to three to four months off work. And you think, oh, crikey, that does not kind of play with my life at the moment. ‐ Participant, <50 years (Chambers et al., 2015) |

Overall, men valued work and described gaining a sense of fulfilment, masculine identity and normality from continuing to work (McSorley et al., 2013; Paterson et al., 2019; Yu Ko et al., 2018). although some men reported difficulty in accessing adequate psychological and instrumental support from their employers (Paterson et al., 2019).

3.5. Disclosure and stigma

Stigma around PCa and a reluctance to disclose their diagnosis and its consequences to friends and family were reported by participants in several studies (Dickey et al., 2020; Dunn et al., 2017; Ettridge et al., 2017; Maharaj & Kazanjian, 2019; Margariti et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2019; Volk et al., 2013). Men in one study viewed a diagnosis of PCa as less socially acceptable than a diagnosis of heart disease:

|

They're very sensitive so a lot of guys in the group do not want to talk about it. And the problem is like … my friends do not want to hear about it. It's not something that I could talk to my friends about [like] heart disease but they do not want to hear about this stuff. ‐ Participant (Maharaj & Kazanjian, 2019) |

In one study (Margariti et al., 2019), men discussed their need to conceal negative emotions from their immediate family, in order to present themselves as a role model for their children.

3.6. Overarching themes

3.6.1. Whole person‐sensitive care

Men across all included studies felt that information and support provided by HCPs did not take account of their needs as an individual. While men were generally in agreement that provision of psychosocial support could be improved, there was significant variation in individual preferences for the actual method of delivery—whether through peer support, the provision of specialist nurses or through their physician. Differing emphasis was placed on longevity and quality of life by individual participants, suggesting a need for increased awareness of these different perspectives. Individual participants often reported stage‐specific concerns, particularly with regard to shared decision‐making during AS. Particular groups, such as GBM, reported unique experiences, informational needs and psychosocial needs that differed from the majority. Sources of support that proved valuable for one group of men—such as group peer support—were sometimes perceived as inappropriate by another.

3.6.2. Comprehensive psychosocial and psychosexual support

In nearly all included studies, there were examples of significant psychological need, many of which were unmet. Some men reported a support need for an impaired sense of masculine identity, some for a perception of loss of control and others for feeling isolated and lonely. Many men were in agreement that psychosocial support was fragmented and poorly implemented, particularly in the context of survivorship care. Some men felt that HCPs failed to adequately advise them about the risk of sexual dysfunction before making key treatment decisions, leaving them blindsided when these side effects did occur—an effect compounded by poor provision of psychosexual support following discharge from secondary care.

3.6.3. Managing the wider impact on lifestyle

Significant need was evident in the context of men's everyday lives. Some men struggled with a return to work following treatment, and others faced significant obstacles in undertaking structured exercise. A substantial burden of instrumental support—such as providing lifts to appointments, helping with dietary changes and attending support groups—fell upon partners, who sometimes received little or no support themselves. Men who were unpartnered, as a result, were sometimes left either unsupported in these areas or having to rely on assistance from friends and family. Equally, the challenging psychological and biographical impact of treatment had a profound impact on men's family lives and relationships.

4. DISCUSSION

In this review update, we have synthesised the available qualitative research on supportive care needs in PCa patients since July 2013 and provided recommendations for future practice in supportive care. There are a number of novel findings: Firstly, men from minority groups can experience PCa differently and may present with a different set of supportive care needs; secondly, the burden of psychosocial and psychosexual need is significant, affects all parts of men's lives and is often unmet by existing models of care; and thirdly, there is a need for greater lifestyle support for men undergoing treatment and during survivorship.

Individuality was a key theme in this review, suggesting that men's premorbid life or demographic may be crucial in how they manage a PCa diagnosis. A study of older men showed that these men have unique informational needs and may face greater obstacles to sharing their experiences with others (van Ee et al., 2018). Younger men with PCa, meanwhile, were less likely to be retired and often faced unique challenges around employment (Appleton et al., 2014; Burbridge et al., 2019; Chambers et al., 2015; Maharaj & Kazanjian, 2019; Paterson et al., 2019; Yu Ko et al., 2018, 2019). This is highly relevant, given the increasing numbers of men diagnosed with PCa at a younger age and the likelihood that these men will be required to live with damaging disease and treatment side effects for longer (Lin et al., 2009). GBM reported different experiences and needs to heterosexual men. Often, these men were unable to obtain information and support that was appropriate in the context of their sexuality. Access to tailored support is a significant social determinant of health in the LGBT community (Matthews et al., 2018), creating an incentive for improvement in this area.

The Internet played a significant role in meeting the informational needs of men across several of the included studies (Chauhan et al., 2018; Fitch et al., 2017; Hogden et al., 2019; Kassianos et al., 2015; Le et al., 2016; O'Callaghan et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2016). Men who used the Internet often did so as a means of attaining self‐efficacy, particularly where they lacked a sense of agency and felt powerless, or poorly informed about their condition. However, many men reported concerns about the integrity of what they had read online, and others felt ‘overloaded’ by information from different sources. It is well‐recognised that evidence found online can be of indeterminate quality, disorganised and difficult for laypeople to review critically and interpret (Cline, 2001). Despite this, well‐structured, reliable information has potential to provide considerable educational benefit to patients (Salonen et al., 2014) Moreover, the Internet and mobile technologies (mHealth) can be powerful tools for the delivery of psychological and supportive care (Andersson et al., 2019; Salonen et al., 2014) and may be an effective means of delivering robust psychosocial support to men with PCa as part of existing, digitally‐enabled integrated models of care.

The burden of unmet psychosocial and psychosexual needs among the included studies was significant, in agreement with findings in the previous review (King et al., 2015). However, new literature within this review further characterises the extent to which psychosocial and psychosexual changes affect men's identities and emotional wellbeing. A key driver of distress for many men was a loss of masculine identity, which had significant impact on some men's perceptions of themselves as fathers, husbands and workers. Previous work suggests that reasons for this are complex and should be explored with men on an individual basis prior to the delivery of supportive care (Peter K O'Shaughnessy et al., 2013).

Instrumental support was commonly provided informally, with partners having to assume the role of caregiver to men recovering from surgery and experiencing fatigue or with advanced disease. Informal caregiving is common among cancer patients and their families but can create further unmet needs for the carer (Romito et al., 2013) and may indicate shortcomings in men's formal care. Significantly, men who were unpartnered were sometimes left unsupported as a result.

Recent practice guidelines in PCa survivorship (Dunn, Green, et al., 2020) help contextualise the supportive care needs reported in this review within present and future practice. Effective advocacy and health promotion will be important in tackling the societal stigma and lifestyle adjustments described by some participants, as well as in facilitating continuing governmental support for survivorship care at the healthcare system level. Meanwhile, formal co‐ordination of care, with active involvement of community‐based healthcare providers and other services (such as PCSGs), will be vital in helping to address the broader impact of PCa on men's lives.

Furthermore, our review highlights the importance of relevant, personalised information in facilitating patient agency and shared decision making across both treatment and survivorship, which should be a key consideration for future practice. However, as demonstrated in this review and elsewhere (Arora & McHorney, 2000), patients' preferences for participation in decision making are highly individual and need to be discussed both at the outset and throughout the care journey.

4.1. Strengths and limitations to the study

The strengths of this study include the use of a similarly rigorous qualitative synthesis methodology to that employed by the authors of the previous review (King et al., 2015), the inclusion of a wealth of new literature which addresses aspects of supportive care needs and experiences in minority groups (such as minority sexual orientations, minority ethnic groups, older men and younger men) and the inclusion of literature across a considerably broader geographical scope. In addition, we establish key barriers to the use of information technology for supportive care among PCa patients, which are likely to become increasingly pertinent as digital health grows in importance. The two main methodological limitations of this study are the lack of a formal quality assessment and the exclusion of ‘grey’ literature: for example, unpublished and nonpeer reviewed work. However, it is arguable whether the inclusion of either of these would have altered the findings substantially. Additionally, although this review includes literature from multiple regions, there were fewer studies from Asian and African countries. With the incidence of PCa rising in both Asia and Sub‐Saharan Africa, there is a need for future research to identify supportive care needs in Asian and African men with PCa.

5. CONCLUSION

In this review, we present and synthesise 105 qualitative studies addressing the spectrum of patient needs and experiences in PCa. We offer novel insight into the unique experiences of men in minority groups with PCa, barriers to information‐seeking and the importance of high‐quality, comprehensive psychosocial care. Finally, we highlight key areas for improvement in future practice within supportive care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by a grant from the Rosetrees Trust.

Supporting information

Supplementary Table S1: Studies included in this review.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Sophie Pattison, the Clinical Support Librarian at the Royal Free Hospital Medical Library, for her assistance with this review.

Prashar, J. , Schartau, P. , & Murray, E. (2022). Supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer: A systematic review update. European Journal of Cancer Care, 31(2), e13541. 10.1111/ecc.13541

Funding information Rosetrees Trust, Grant/Award Number: UCL‐IHE‐2020\104

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supporting information of this article.

REFERENCES

- Akakura, K. , Bolton, D. , Grillo, V. , & Mermod, N. (2020). Not all prostate cancer is the same ‐ patient perceptions: An Asia‐Pacific region study. BJU International, 126(Supplement 1), 38–45. 10.1111/bju.15129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albaugh, J. A. , Sufrin, N. , Lapin, B. R. , Petkewicz, J. , & Tenfelde, S. (2017). Life after prostate cancer treatment: A mixed methods study of the experiences of men with sexual dysfunction and their partners. BMC Urology, 17(1), 45. 10.1186/s12894-017-0231-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. , Marshall‐Lucette, S. , & Webb, P. (2013). African and afro‐Caribbean men's experiences of prostate cancer. British Journal of Nursing, 22(22), 1296–1307. 10.12968/bjon.2013.22.22.1296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, G. , Titov, N. , Dear, B. F. , Rozental, A. , & Carlbring, P. (2019). Internet‐delivered psychological treatments: From innovation to implementation. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 20–28. 10.1002/wps.20610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, L. , Wyatt, D. , Perkins, E. , Parker, C. , Crane, J. , Jones, A. , Moorhead, L. , Brown, V. , Wall, C. , & Pagett, M. (2014). The impact of prostate cancer on mens everyday life. European Journal of Cancer Care (Englande), 24(1), 71–84. 10.1111/ecc.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, R. , Nanton, V. , Roscoe, J. , & Dale, J. (2019). Good care throughout the prostate cancer pathway: Perspectives of patients and health professionals. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 42, 36–41. 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, J. S. , da Conceição, V. M. , & Zago, M. M. F. (2019). Transitory masculinities in the context of being sick with prostate cancer. Revista Latino‐American de Enfermagem, 27, e3224. 10.1590/1518-8345.3248.3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora, N. K. , & McHorney, C. A. (2000). Patient preferences for medical decision making: Who really wants to participate? Medical Care, 38(3), 335–341. 10.1097/00005650-200003000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray, F. , Ferlay, J. , Soerjomataram, I. , Siegel, R. L. , Torre, L. A. , & Jemal, A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burbridge, C. , Randall, J. A. , Lawson, J. , Symonds, T. , Dearden, L. , Lopez‐Gitlitz, A. , Espina, B. , & McQuarrie, K. (2019). Understanding symptomatic experience, impact, and emotional response in recently diagnosed metastatic castration‐resistant prostate cancer: A qualitative study. Support Care Cancer, 28(7), 3093–3101. 10.1007/s00520-019-05079-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capistrant, B. D. , Torres, B. , Merengwa, E. , West, W. G. , Mitteldorf, D. , & Rosser, B. R. S. (2016). Caregiving and social support for gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 25(11), 1329–1336. 10.1002/pon.4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catt, S. , Matthews, L. , May, S. , Payne, H. , Mason, M. , & Jenkins, V. (2019). Patients' and partners' views of care and treatment provided for metastatic castrate‐resistant prostate cancer in the UK. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(6), e13140. 10.1111/ecc.13140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. K. , Hyde, M. K. , Laurie, K. , Legg, M. , Frydenberg, M. , Davis, I. D. , Lowe, A. , & Dunn, J. (2018). Experiences of Australian men diagnosed with advanced prostate cancer: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8(2), e019917. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. K. , Lowe, A. , Hyde, M. K. , Zajdlewicz, L. , Gardiner, R. A. , Sandoe, D. , & Dunn, J. (2015). Defining Young in the context of Prostate Cancer. American journal of Men's. Health, 9(2), 103–114. 10.1177/1557988314529991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan, M. , Holch, P. , & Holborn, C. (2018). Assessing the information and support needs of radical prostate cancer patients and acceptability of a group‐based treatment review: A questionnaire and qualitative interview study. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice, 17(2), 151–161. 10.1017/s1460396917000644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. , Ren, S. , Chinese Prostate Cancer Consortium , Yiu, M. K. , Fai, N. C. , Cheng, W. S. , Ian, L. H. , Naito, S. , Matsuda, T. , Kehinde, E. , Kural, A. , Chiu, J. Y. , Umbas, R. , Wei, Q. , Shi, X. , Zhou, L. , Huang, J. , Huang, Y. , Xie, L. , … Sun, Y. (2014). Prostate cancer in Asia: A collaborative report. Asian Journal of Urology, 1(1), 15–29. 10.1016/j.ajur.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline, R. J. W. (2001). Consumer health information seeking on the internet: The state of the art. Health Education Research, 16(6), 671–692. 10.1093/her/16.6.671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coa, K. I. , Smith, K. C. , Klassen, A. C. , Thorpe, R. J. , & Caulfield, L. E. (2015). Exploring important influences on the healthfulness of Prostate Cancer Survivors' diets. Qualitative Health Research, 25(6), 857–870. 10.1177/1049732315580108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockle‐Hearne, J. , Charnay‐Sonnek, F. , Denis, L. , Fairbanks, H. E. , Kelly, D. , Kav, S. , Leonard, K. , van Muilekom, E. , Fernandez‐Ortega, P. , Jensen, B. T. , & Faithfull, S. (2013). The impact of supportive nursing care on the needs of men with prostate cancer: A study across seven European countries. British Journal of Cancer, 109(8), 2121–2130. 10.1038/bjc.2013.568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. , & Strauss, A. (1988). Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home. Jossey‐Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cornford, P. , van den Bergh, R. C. N. , Briers, E. , van den Broeck, T. , Cumberbatch, M. G. , de Santis, M. , Fanti, S. , Fossati, N. , Gandaglia, G. , Gillessen, S. , Grivas, N. , Grummet, J. , Henry, A. M. , der Kwast, T. H. , van Lam, T. B. , Lardas, M. , Liew, M. , Mason, M. D. , Moris, L. , … Mottet, N. (2021). EAU‐EANM‐ESTRO‐ESUR‐SIOG guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II—2020 update: Treatment of relapsing and metastatic Prostate Cancer. European Urology, 79(2), 263–282. 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey, S. L. , Matthews, C. , & Millender, E. (2020). An exploration of Precancer and post‐Cancer diagnosis and health communication among African American Prostate Cancer survivors and their families. American Journal of Men's Health, 14(3), 1557988320927202. 10.1177/1557988320927202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran, D. , Williamson, S. , Wright, K. M. , & Beaver, K. (2018). It's not just about prostate cancer, it's about being a gay man: A qualitative study of gay men's experiences of healthcare provision in the UK. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(6), e12923. 10.1111/ecc.12923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J. , Casey, C. , Sandoe, D. , Hyde, M. K. , Cheron‐Sauer, M.‐C. , Lowe, A. , Oliffe, J. L. , & Chambers, S. K. (2017). Advocacy, support and survivorship in prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(2), e12644. 10.1111/ecc.12644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J. , Green, A. , Ralph, N. , Newton, R. , Kneebone, A. , Frydenberg, M. , & Chambers, S. (2020). Prostate cancer survivorship essentials framework: Guidelines for practitioners. BJU International. 10.1111/bju.15159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J. , Ralph, N. , Green, A. , Frydenberg, M. , & Chambers, S. K. (2020). Contemporary consumer perspectives on prostate cancer survivorship: Fifty voices. Psycho‐Oncology, 29(3), 557–563. 10.1002/pon.5306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Er, V. , Lane, J. A. , Martin, R. M. , Persad, R. , Chinegwundoh, F. , Njoku, V. , & Sutton, E. (2017). Barriers and facilitators to healthy lifestyle and acceptability of a dietary and physical activity intervention among African Caribbean prostate cancer survivors in the UK: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 7(10), e017217. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettridge, K. A. , Bowden, J. A. , Chambers, S. K. , Smith, D. P. , Murphy, M. , Evans, S. M. , Roder, D. , & Miller, C. L. (2017). Prostate cancer is far more hidden …: Perceptions of stigma, social isolation and help‐seeking among men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 27(2), e12790. 10.1111/ecc.12790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, M. , Ouellet, V. , Pang, K. , Chevalier, S. , Drachenberg, D. E. , Finelli, A. , Lattouf, J.‐B. , Loiselle, C. , So, A. , Sutcliffe, S. , Tanguay, S. , Saad, F. , & Mes‐Masson, A.‐M. (2020). Comparing perspectives of Canadian men diagnosed with Prostate Cancer and health care professionals about active surveillance. Journal of Patient Experience, 7(6), 1122–1129. 10.1177/2374373520932735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, M. , Pang, K. , Ouellet, V. , Loiselle, C. , Alibhai, S. , Chevalier, S. , Drachenberg, D. E. , Finelli, A. , Lattouf, J.‐B. , Sutcliffe, S. , So, A. , Tanguay, S. , Saad, F. , & Mes‐Masson, A.‐M. (2017). Canadian Men's perspectives about active surveillance in prostate cancer: Need for guidance and resources. BMC Urology, 17(1), 98. 10.1186/s12894-017-0290-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbat, L. , Place, M. , Hubbard, G. , Leung, H. , & Kelly, D. (2013). The role of interpersonal relationships in mens attendance in primary care: Qualitative findings in a cohort of men with prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer, 22(2), 409–415. 10.1007/s00520-013-1989-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili, C. , McClean, S. , Hackshaw‐McGeagh, L. , Bahl, A. , Persad, R. , & Harcourt, D. (2019). Body image issues and attitudes towards exercise amongst men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) following diagnosis of prostate cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 28(8), 1647–1653. 10.1002/pon.5134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, R. (2019). Maintaining masculinity: Moral positioning when accounting for prostate cancer illness. Health, 25(4), 399–416. 10.1177/1363459319851555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K. , Chambers, S. K. , Legg, M. , Oliffe, J. L. , & Cormie, P. (2014). Sexuality and exercise in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer, 23(1), 133–142. 10.1007/s00520-014-2327-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, P. K. J. , Hootsmans, N. , Neilson, M. , Roy, B. , Kungel, T. , Gutheil, C. , Diefenbach, M. , & Hansen, M. (2013). The value of personalised risk information: A qualitative study of the perceptions of patients with prostate cancer. BMJ Open, 3(9), e003226. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanly, N. , Mireskandari, S. , & Juraskova, I. (2014). The struggle towards ‘the new normal’: A qualitative insight into psychosexual adjustment to prostate cancer. BMC Urology, 14(1), 56. 10.1186/1471-2490-14-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillen, M. A. , Gutheil, C. M. , Smets, E. M. A. , Hansen, M. , Kungel, T. M. , Strout, T. D. , & Han, P. K. J. (2017). The evolution of uncertainty in second opinions about prostate cancer treatment. Health Expectations, 20(6), 1264–1274. 10.1111/hex.12566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogden, A. , Churruca, K. , Rapport, F. , & Gillatt, D. (2019). Appraising risk in active surveillance of localized prostate cancer. Health Expectations, 22(5), 1028–1039. 10.1111/hex.12912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, M. A. , Frost, D. M. , Cohn, E. , Millar, B. M. , Diefenbach, M. A. , & Revenson, T. A. (2017). Gay men's experiences with prostate cancer: Implications for future research. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(3), 298–310. 10.1177/1359105317711491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imm, K. R. , Williams, F. , Housten, A. J. , Colditz, G. A. , Drake, B. F. , Gilbert, K. L. , & Yang, L. (2017). African American prostate cancer survivorship: Exploring the role of social support in quality of life after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 35(4), 409–423. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1294641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jägervall, C. D. , Brüggemann, J. , & Johnson, E. (2019). Gay men's experiences of sexual changes after prostate cancer treatmenta qualitative study in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Urology, 53(1), 40–44. 10.1080/21681805.2018.1563627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. , Stillson, C. H. , Pollack, C. E. , Crossette, L. , Ross, M. , Radhakrishnan, A. , & Grande, D. (2017). How men with Prostate Cancer choose specialists: A qualitative study. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(2), 220–229. 10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassianos, A. P. , Coyle, A. , & Raats, M. M. (2015). Perceived influences on post‐diagnostic dietary change among a group of men with prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(6), 818–826. 10.1111/ecc.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, D. , Forbat, L. , Marshall‐Lucette, S. , & White, I. (2015). Co‐constructing sexual recovery after prostate cancer: A qualitative study with couples. Translational Andrology and Urology, 4(2), 131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh, J. W. L. , Patel, A. , MacLeod, R. D. , & Masters, J. (2013). Perceptions of physically active men with prostate cancer on the role of physical activity in maintaining their quality of life: Possible influence of androgen deprivation therapy. Psycho‐Oncology, 22(12), 2869–2875. 10.1002/pon.3363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, A. J. L. , Evans, M. , Moore, T. H. M. , Paterson, C. , Sharp, D. , Persad, R. , & Huntley, A. L. (2015). Prostate cancer and supportive care: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of men's experiences and unmet needs. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(5), 618–634. 10.1111/ecc.12286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaird, W. , & Stewart‐Lord, A. (2020). A qualitative study exploring men's experience of sexual dysfunction as a result of radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy to treat prostate cancer. Journal of Radiotherapy in Practice, 20(1), 39–42. 10.1017/s1460396920000059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman, M. , Young, K. , Evans, S. , Millar, J. , Fisher, J. , Mazza, D. , & Ruseckaite, R. (2017). Men's perceptions of prostate cancer diagnosis and care: Insights from qualitative interviews in Victoria, Australia. BMC Cancer, 17(1), 704. 10.1186/s12885-017-3699-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B. S. (2016). Sexuality in men after prostate cancer surgery: A qualitative interview study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(1), 120–127. 10.1111/scs.12328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, Y.‐C. , McFall, S. L. , Byrd, T. L. , Volk, R. J. , Cantor, S. B. , Kuban, D. A. , & Mullen, P. D. (2016). Is active surveillance an acceptable alternative?: A qualitative study of Couples' decision making about early‐stage, localized Prostate Cancer. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 6(1), 51–61. 10.1353/nib.2016.0006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. K. , Handy, A. B. , Kwan, W. , Oliffe, J. L. , Brotto, L. A. , Wassersug, R. J. , & Dowsett, G. W. (2015). Impact of Prostate Cancer treatment on the sexual quality of life for men‐who‐have‐sex‐with‐men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(12), 2378–2386. 10.1111/jsm.13030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, A. , & Cartwright, T. (2015). Men's strategies for preserving emotional well‐being in advanced prostate cancer: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology & Health, 30(10), 1164–1182. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1040016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, D. W. , Porter, M. , & Montgomery, B. (2009). Treatment and survival outcomes in young men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer, 115(13), 2863–2871. 10.1002/cncr.24324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb, S. , Curnyn, C. , Fagerlin, A. , Braithwaite, R. S. , Schwartz, M. D. , Lepor, H. , Carter, H. B. , Ciprut, S. , & Sedlander, E. (2018). Informational needs during active surveillance for prostate cancer: A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling, 101(2), 241–247. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mader, E. M. , Li, H. H. , Lyons, K. D. , Morley, C. P. , Formica, M. K. , Perrapato, S. D. , Irwin, B. H. , Seigne, J. D. , Hyams, E. S. , Mosher, T. , Hegel, M. T. , & Stewart, T. M. (2017). Qualitative insights into how men with low‐risk prostate cancer choosing active surveillance negotiate stress and uncertainty. BMC Urology, 17(1), 35. 10.1186/s12894-017-0225-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj, N. , & Kazanjian, A. (2019). Exploring patient narratives of intimacy and sexuality among men with prostate cancer. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 34(2), 163–182. 10.1080/09515070.2019.1695582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mallapareddi, A. , Ruterbusch, J. , Reamer, E. , Eggly, S. , & Xu, J. (2016). Active surveillance for low‐risk localized prostate cancer: What do men and their partners think? Family Practice, 34(1), 90–97. 10.1093/fampra/cmw123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margariti, C. , Gannon, K. , Thompson, R. , Walsh, J. , & Green, J. (2019). Experiences of UK African‐Caribbean prostate cancer survivors of discharge to primary care. Ethnicity & Health. 26(8), 1115–1129. 10.1080/13557858.2019.1606162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson, L. , Wilding, S. , Wagland, R. , Nayoan, J. , Rivas, C. , Downing, A. , Wright, P. , Brett, J. , Kearney, T. , Cross, W. , Glaser, A. , Gavin, A. , & Watson, E. (2019). The psychological impact of being on a monitoring pathway for localised prostate cancer: A UK‐wide mixed methods study. Psycho‐Oncology, 28(7), 1567–1575. 10.1002/pon.5133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A. K. , Breen, E. , & Kittiteerasack, P. (2018). Social determinants of LGBT Cancer health inequities. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(1), 12–20. 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkey, R. W. , & Holborn, C. (2018). Exploring the lived experience of gay men with prostate cancer: A phenomenological study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 33(33), 62–69. 10.1016/j.ejon.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, M. , Opozda, M. , Galvão, D. A. , Chambers, S. K. , & Short, C. E. (2019). Identifying the exercise‐based support needs and exercise programme preferences among men with prostate cancer during active surveillance: A qualitative study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 41, 135–142. 10.1016/j.ejon.2019.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSorley, O. , McCaughan, E. , Prue, G. , Parahoo, K. , Bunting, B. , & OSullivan J. (2013). A longitudinal study of coping strategies in men receiving radiotherapy and neo‐adjuvant androgen deprivation for prostate cancer: A quantitative and qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(3), 625–638. 10.1111/jan.12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina‐Perucha, L. , Yousaf, O. , Hunter, M. S. , & Grunfeld, E. A. (2017). Barriers to medical help‐seeking among older men with prostate cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 35(5), 531–543. 10.1080/07347332.2017.1312661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, A. , Pollack, C. E. , Gillespie, T. W. , Duby, A. , Carter, C. , Thelen‐Perry, S. , & Witmann, D. (2019). What patients and partners want in interventions that support sexual recovery after Prostate Cancer treatment: An exploratory convergent mixed methods study. Sexual Medicine, 7(2), 184–191. 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menichetti, J. , de Luca, L. , Dordoni, P. , Donegani, S. , Marenghi, C. , Valdagni, R. , & Bellardita, L. (2019). Making active surveillance a path towards health promotion: A qualitative study on prostate cancer patients' perceptions of health promotion during active surveillance. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(3), e13014. 10.1111/ecc.13014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2019). Prostate Cancer: Diagnosis and Management [NICE Guideline No. 131]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng131 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, C. J. , Lacey, S. , Kenowitz, J. , Pessin, H. , Shuk, E. , Roth, A. J. , & Mulhall, J. P. (2015). Mens experience with penile rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy: A qualitative study with the goal of informing a therapeutic intervention. Psycho‐Oncology, 24(12), 1646–1654. 10.1002/pon.3771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, K. , Bennett, P. , & Rance, J. (2019). The experiences of giving and receiving social support for men with localised prostate cancer and their partners. Ecancer, 13, 989. 10.3332/ecancer.2019.989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, C. , Dryden, T. , Hyatt, A. , Brooker, J. , Burney, S. , Wootten, A. C. , White, A. , Frydenberg, M. , Murphy, D. , Williams, S. , & Schofield, P. (2014). ‘What is this active surveillance thing?’ Men's and partners' reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psycho‐Oncology, 23(12), 1391–1398. 10.1002/pon.3576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odedina, F. , Young, M. E. , Pereira, D. , Williams, C. , Nguyen, J. , & Dagne, G. (2017). Point of prostate cancer diagnosis experiences and needs of black men: The Florida CaPCaS study. Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology, 15(1), 10–19. 10.12788/jcso.0323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J. L. , Mróz, L. W. , Bottorff, J. L. , Braybrook, D. E. , Ward, A. , & Goldenberg, L. S. (2014). Heterosexual couples and prostate cancer support groups: A gender relations analysis. Support Care Cancer, 23(4), 1127–1133. 10.1007/s00520-014-2562-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy, P. K. , Ireland, C. , Pelentsov, L. , Thomas, L. A. , & Esterman, A. J. (2013). Impaired sexual function and prostate cancer: A mixed method investigation into the experiences of men and their partners. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(23–24), 3492–3502. 10.1111/jocn.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy, P. K. , Laws, T. A. , & Esterman, A. J. (2015). The Prostate Cancer journey. Cancer Nursing, 38(1), E1–E12. 10.1097/ncc.0b013e31827df2a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, O. L. , Estrada, R. M. , Johnson, K. , Cogdell, M. , Fried, D. B. , Gansauer, L. , & Kim, S. (2019). ‘I'm not a chance taker’: A mixed methods exploration of factors affecting prostate cancer treatment decision‐making. Ethnicity & Health, 26(8), 1143–1162. 10.1080/13557858.2019.1606165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , Shamseer, L. , Tetzlaff, J. M. , Akl, E. A. , Brennan, S. E. , Chou, R. , Glanville, J. , Grimshaw, J. M. , Hróbjartsson, A. , Lalu, M. M. , Li, T. , Loder, E. W. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , McDonald, S. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, C. , Kata, S. G. , Nandwani, G. , Chaudhury, D. d. , & Nabi, G. (2017). Unmet supportive care needs of men with locally advanced and metastatic Prostate Cancer on hormonal treatment. Cancer Nursing, 40(6), 497–507. 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, C. , Primeau, C. , & Lauder, W. (2019). What are the experiences of men affected by Prostate Cancer participating in an ecological momentary assessment study? Cancer Nursing, 43(4), 300–310. 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phahlamohlaka, M. N. , Mdletshe, S. , & Lawrence, H. (2018). Psychosexual experiences of men following radiotherapy for prostate cancer in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 23, a1057. 10.4102/hsag.v23i0.1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietilä, I. , Jurva, R. , Ojala, H. , & Tammela, T. (2018). Seeking certainty through narrative closure: Men's stories of prostate cancer treatments in a state of liminality. Sociology of Health & Illness, 40(4), 639–653. 10.1111/1467-9566.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, E. , Karachaliou, G. S. , Kao, C. , Harrison, M. R. , Hoimes, C. J. , George, D. J. , Armstrong, A. J. , & Zhang, T. (2020). Novel therapies are changing treatment paradigms in metastatic prostate cancer. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 13(1), 144. 10.1186/s13045-020-00978-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primeau, C. , Paterson, C. , & Nabi, G. (2017). A qualitative study exploring models of supportive Care in men and Their Partners/caregivers affected by metastatic Prostate Cancer. ONF, 44(6), E241–E249. 10.1188/17.onf.e241-e249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prostate Cancer UK (2020). Prostate Cancer UK. https://prostatecanceruk.org/about-us/news-and-views/2020/6/most-common-cancer-in-uk

- Romito, F. , Goldzweig, G. , Cormio, C. , Hagedoorn, M. , & Andersen, B. L. (2013). Informal caregiving for cancer patients. Cancer, 119(11), 2160–2169. 10.1002/cncr.28057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D. , Ussher, J. M. , & Perz, J. (2016). Lets talk about gay sex: Gay and bisexual mens sexual communication with healthcare professionals after prostate cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 26(1), e12469. 10.1111/ecc.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A. J. , Weinberger, M. I. , & Nelson, C. J. (2008). Prostate cancer: Psychosocial implications and management. Future Oncology, 4(4), 561‐8. 10.2217/14796694.4.4.561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, A. , Ryhänen, A. M. , & Leino‐Kilpi, H. (2014). Educational benefits of internet and computer‐based programmes for prostate cancer patients: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 94(1), 10–19. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildmeijer, K. , Frykholm, O. , Kneck, Å. , & Ekstedt, M. (2019). Not a straight line—Patients' experiences of Prostate Cancer and their journey through the healthcare system. Cancer Nursing, 42(1), 36–43. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, A. T. , Taylor, K. L. , Davis, K. , Nepple, K. G. , Lynch, J. H. , Oberle, A. D. , Hall, I. J. , Volk, R. J. , Reisinger, H. S. , & Hoffman, R. M. (2019). Why men with a low‐risk prostate cancer select and stay on active surveillance: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 14(11), e0225134. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seraphin, T. P. , Joko‐Fru, W. Y. , Kamaté, B. , Chokunonga, E. , Wabinga, H. , Somdyala, N. I. M. , Manraj, S. S. , Ogunbiyi, O. J. , Dzamalala, C. P. , Finesse, A. , Korir, A. , N'Da, G. , Lorenzoni, C. , Liu, B. , Kantelhardt, E. J. , & Parkin, D. M. (2021). Rising Prostate Cancer incidence in sub‐Saharan Africa: A trend analysis of data from the African Cancer registry network. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 30(1), 158–165. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheill, G. , Guinan, E. , Neill, L. O. , Hevey, D. , & Hussey, J. (2017). The views of patients with metastatic prostate cancer towards physical activity: A qualitative exploration. Support Care Cancer, 26(6), 1747–1754. 10.1007/s00520-017-4008-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, M. J. , Nelson, C. J. , Peters, E. , Slovin, S. F. , Hall, S. J. , Hall, M. , Herrera, P. C. , Leventhal, E. A. , Leventhal, H. , & Diefenbach, M. A. (2014). Decision‐making processes among Prostate Cancer survivors with rising PSA levels. Medical Decision Making, 35(4), 477–486. 10.1177/0272989x14558424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speer, S. A. , Tucker, S. R. , McPhillips, R. , & Peters, S. (2017). The clinical communication and information challenges associated with the psychosexual aspects of prostate cancer treatment. Social Science & Medicine, 185, 17–26. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thera, R. , Carr, D. T. , Groot, D. G. , Baba, N. , & Jana, D. K. (2018). Understanding medical decision‐making in Prostate Cancer care. American journal of Men's. Health, 12(5), 1635–1647. 10.1177/1557988318780851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]