Abstract

Objective

The web‐based application Oncokompas was developed to support cancer patients to self‐manage their symptoms. This qualitative study was conducted to obtain insight in patients' self‐management strategies to cope with cancer and their experiences with Oncokompas as a fully automated behavioural intervention technology.

Methods

Data were collected from semi‐structured interviews with 22 participants (10 head and neck cancer survivors and 12 incurably ill patients). Interview questions were about self‐management strategies and experiences with Oncokompas. Interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

Participants applied several self‐management strategies, among which trying to stay in control and make the best of their situation. They described Oncokompas' added value: being able to monitor symptoms and having access to a personal online library. Main reasons for not using Oncokompas were concentration problems, lack of time or having technical issues. Recommendations were made for further development of Oncokompas, relating to its content, technical and functional aspects.

Conclusions

Survivors and incurably ill patients use various self‐management strategies to cope with cancer. The objectives of self‐management interventions as Oncokompas correspond well with these strategies: taking a certain responsibility for your well‐being and being in charge of your life as long as possible by obtaining automated information (24/7) on symptoms and tailored supportive care options.

Keywords: cancer, eHealth, evaluation of care, head and neck cancer, self‐management, supportive care

1. INTRODUCTION

Digital technologies supporting patients to self‐manage cancer‐related symptoms are evolving rapidly in cancer care (Haberlin et al., 2018; Seiler et al., 2017; Triberti et al., 2019) and can improve patients' health‐related quality of life (HRQOL) and self‐management behaviour (Cuthbert et al., 2019; D. Howell et al., 2017; V.N. Slev et al., 2016).

The fully automated behavioural intervention technology (BIT) Oncokompas was developed to support cancer patients to self‐manage their cancer‐related symptoms in addition to medical care. Self‐management is described as ‘an individual's ability to manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition’ (Barlow et al., 2002). Based on three steps in Oncokompas (Measure, Learn and Act), patients are supported to take action to meet their supportive care needs. A participatory design approach was used to develop Oncokompas; end‐users, healthcare professionals, researchers, policymakers and insurance companies were actively involved in the design process (van Gemert‐Pijnen et al., 2011). From 2017 until 2020, two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were conducted to determine the efficacy of Oncokompas among cancer survivors and incurably ill patients (Schuit et al., 2019; A. van der Hout et al., 2017). Evaluation of the trial among incurably ill patients is still in progress, but the results of the RCT among cancer survivors are available (A. van der Hout et al., 2020). Oncokompas was (cost‐)effective to improve HRQOL and to reduce symptom burden among cancer survivors but did not show significant effects on patients' knowledge, skills and confidence to self‐manage their illness (i.e., patient activation) (A. van der Hout et al., 2020). Most participants were long‐term survivors, being more than 2 years after diagnosis, and already might have obtained sufficient self‐management skills, knowledge and confidence.

Oncokompas seems most effective among survivors reporting higher burden of tumour‐specific symptoms, survivors with lower self‐efficacy, higher personal control (i.e., believing to be able to control life events and circumstances; Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) or higher health literacy (A. van der Hout, Holtmaat, et al., 2021). In total, 52% of the survivors used Oncokompas as intended (i.e., completion of the components ‘Measure’ and ‘Learn’ for at least one topic). Main reasons for not using Oncokompas were no symptom burden, no supportive care needs or lack of time (A. van der Hout, van Uden‐Kraan, et al., 2021).

Despite insights in the efficacy of Oncokompas, underlying mechanisms of the efficacy and usage of Oncokompas as a self‐management application remain unclear. To create more understanding about ways in which self‐management applications could fit into patients' daily life, also patients' self‐management strategies to deal with the impact of cancer and its treatment are of interest. To summarise, the aim of this qualitative study was to gain more insight in how cancer survivors and incurably ill cancer patients deal with cancer in their daily lives and how they experience Oncokompas as a fully automated BIT supporting them to cope with cancer‐related symptoms. The results can be used to create a better fit between patients' self‐management strategies and their wishes regarding BITs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context and selection of study participants

Since Oncokompas has been developed targeting all cancer patients (all cancer types and all treatment modalities), both cancer survivors and incurably ill cancer patients were included in this study. We recruited participants through two different channels; through routine care (survivors of head and neck cancer (HNC; all subsites and all treatment modalities; at least three months after cancer treatment with curative intent)) and as a follow‐up study adjacent to a randomised controlled trial (incurably ill patients (no curative treatment options)). Eligible patients were 18 years or older and able to communicate in Dutch. Patients were excluded if they had severe cognitive impairments or did not have access to a computer or an e‐mail address.

Recruitment of HNC survivors was conducted in the context of routine care, and therefore ethical approval was not needed. Survivors were asked to participate in this evaluation study by their head and neck surgeon or nurse at the department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Amsterdam UMC. When patients were interested, they received an information letter about the study and gave their written consent to get contacted by the research team. Subsequently, patients were contacted to schedule the interview. All HNC survivors who participated in the study provided written informed consent at the start of the interview.

Recruitment of incurably ill cancer patients was conducted in the context of an RCT determining the efficacy of Oncokompas (Schuit et al., 2019), and therefore, ethical approval was needed. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee (METc) of AmsterdamUMC, location VUmc (2018.224, A2019.154). Inclusion criteria were being diagnosed with incurable cancer (any cancer type and treatment modality), having a life expectancy of at least three months and being aware of the incurability of the cancer. Patients were excluded when they were too ill to participate or when participation would be too burdensome. Patients were asked to give their written informed consent for participation in the RCT. Additionally, they were asked to give their consent to be approached for this qualitative follow‐up study. Patients who gave their permission to get contacted for the follow‐up study received an information letter with an invitation for the interview (per e‐mail or per post). When patients were interested to participate, they were asked to return the reply card or to send an e‐mail in response. Then, patients were contacted by the research team to schedule the interview. All incurably ill cancer patients who participated in the study provided written informed consent at the start of the interview.

2.2. The application ‘Oncokompas’

Oncokompas is a web‐based eHealth application supporting cancer survivors and patients to self‐manage their cancer‐generic and tumour‐specific symptoms. Oncokompas consists of three steps: Measure, Learn and Act. Within the first step ‘Measure’, users are asked to complete Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) on different topics related to their HRQOL. These PROMs target physical, psychological and social functioning, and existential issues. Users can select which topics they want to monitor in Oncokompas. Answers on PROMs are processed real‐time and linked to information and feedback in the step ‘Learn’, which provides an overview of users' well‐being on topic level using a traffic‐light system. Green scores mean that users are doing well on topics. Orange scores mean that topics could use attention and support. Red scores mean that topics need attention and support. Subsequently, Oncokompas provides tailored information and advice, such as tips and tools to deal with symptoms. In the step ‘Act’, users receive a personalised overview of supportive care options in their neighbourhood. When users have orange scores on topics, the overview includes options for self‐help interventions. When users have red scores on topics, feedback always includes the advice to contact their (specialised) healthcare professionals (Duman‐Lubberding et al., 2016).

2.3. Interview and procedure

From July 2019 till July 2020, 22 semi‐structured interviews were performed by two interviewers (VvZ [cancer survivors] and AS [incurably ill cancer patients]), both trained in qualitative research methods. The interviews were scheduled at patients' preferred location; home (n = 11), the outpatient clinic (n = 1) or by phone due to safety measures during the COVID‐19 pandemic (n = 9). One participant with speech impairments gave written response to the interview questions. Interviews lasted 39 to 94 min (median 66 min).

The interview scheme comprised two main topics with related questions (Table 1), derived from Oncokompas implementation and developmental experiences of the research team, and the literature. Interviews were recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim. Due to practical reasons, participants did not receive the transcripts for comments or corrections.

TABLE 1.

Interview topics

| Topics | Themes |

|---|---|

| Self‐management strategies |

|

| Experiences using Oncokompas | When patients used Oncokompas:

|

2.4. Data analysis

The software program Atlas.ti (version 8) was used to analyse the transcripts, using reflexive thematic analysis (V. Braun & Clarke, 2012; V. Braun & Clarke, 2020). Data analysis ran parallel to data collection. Two coders (AS and VvZ) read the transcripts to get familiar with the data and then analysed the data individually. Descriptive citations within the transcripts were coded into themes and more refined subthemes derived from the data. Each interview was coded individually, after which the findings were discussed in consensus meetings. In these meetings, the coders discussed their findings, resolved differences and created a thematic framework based on the consensus of their individual findings. Doubts during these meetings (e.g., coding certain citations into main themes) were consulted with two independent researchers (IVdL and KH). During analysis, themes and subthemes were constantly reviewed critically to review whether a coherent pattern of themes and subthemes was formed (Nowell et al., 2017). Furthermore, the coders made notes during the consensus meetings to report on the analysis process.

All extracted quotes used in this paper were translated from Dutch into English. To ensure participants' privacy, information that could lead to persons' identification was removed.

The guidelines for consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were followed to report about the study design, procedures, analysis and findings (Tong et al., 2007).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

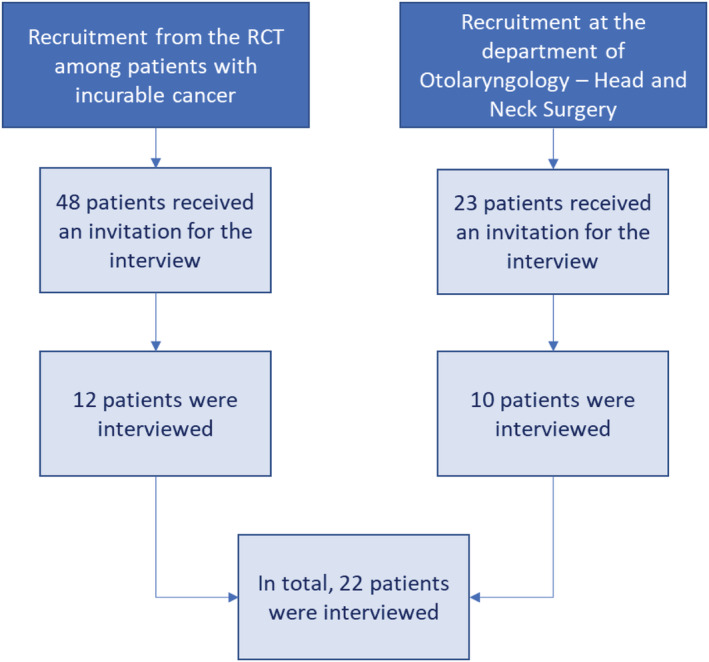

In total, 71 patients were invited (23 HNC survivors and 48 incurably ill patients) of which 22 patients agreed to be interviewed (10 survivors [43%] and 12 patients [25%]; Figure 1). We aimed to get comparable group sizes and had to invite more incurably ill patients to realise this. After 22 interviews no additional valuable information was obtained, and data saturation had been reached (i.e., carefully weighing the adequacy of the data for addressing the research questions, based on all data gathered in both patient groups (V. Braun & Clarke, 2021). Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the study

TABLE 2.

Participant characteristics (n = 22)

| Total n (%) | HNC survivors n (%) | Incurably ill patients n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 14 (64) | 7 (70) | 7 (58) |

| Female | 8 (36) | 3 (30) | 5 (42) |

| Age at interview (in years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 65.5 (10.2) | 64.2 (11.8) | 66.6 (8.8) |

| Minimum | 38 | 38 | 49 |

| Maximum | 81 | 81 | 78 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single/divorced | 4 (18) | 2 (20) | 2 (17) |

| Having a relationship/living together | 2 (9) | 1 (10) | 1 (8) |

| Married | 15 (68) | 6 (60) | 9 (75) |

| Widow(er) | 1 (5) | 1 (10) | ‐ |

| Highest level of education completed | |||

| Low | 9 (41) | 4 (40) | 5 (42) |

| Middle | 5 (23) | 2 (20) | 3 (25) |

| High | 7 (32) | 3 (30) | 4 (33) |

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 1 (10) | ‐ |

| Current employment | |||

| Paid job | 5 (23) | 2 (20) | 3 (25) |

| No paid job/unemployed/incapacitated | 5 (23) | 3 (30) | 2 (17) |

| Retired | 12 (55) | 5 (50) | 7 (58) |

| Type of cancer | |||

| Breast cancer | 3 (14) | ‐ | 3 (25) |

| Lung cancer | 2 (9) | ‐ | 2 (17) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 3 (14) | ‐ | 3 (25) |

| Head and neck cancer | 11 (50) | 10 (100) | 1 (8) |

| Haematological cancer | 2 (9) | ‐ | 2 (17) |

| Brain tumour | 1 (5) | ‐ | 1 (8) |

| Time since cancer diagnosis | |||

| 1–3 years | 7 (32) | 4 (40) | 3 (25) |

| 3–5 years | 8 (36) | 5 (50) | 3 (25) |

| >5 years | 6 (27) | ‐ | 6 (50) |

| Unknown | 1 (5) | 1 (10) | ‐ |

The results of the study related to patients' strategies to cope with cancer in their daily lives and their perspectives on Oncokompas. Patients' perspectives on Oncokompas were divided in different categories: the positive aspects of Oncokompas and experiences relating to the content of the application, its technical and functional aspects, and actual usage of the application.

3.2. Self‐management strategies

Table 3 provides an overview of strategies to cope with cancer in daily life. Self‐management strategies described by HNC survivors and incurably ill patients were quite similar. Participants mentioned that self‐managing their disease means being able to take care of themselves, not being dependent of others. It means knowing when to ask for help (e.g., from the healthcare provider). They specified that it means to stay in control of your life: being able to take care of yourself and being in control. For example, by making a plan for the future, taking care of things that need to be arranged. Some participants made adjustments to their daily lives, such as trying to maintain a daily rhythm, choosing friends more consciously and making adjustments to their living environment (e.g., to make it easier to live at home).

TABLE 3.

Participants' self‐management strategies to cope with cancer‐related symptoms

| Themes | Subthemes | Example of a subtheme quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Staying in control |

|

‘It [self‐management] means being in control. That I take action when I feel something is wrong. […] As so many things in life, I'd like to be in control about that [being informed about the disease]. It's not always possible. You are dependent of the doctor's schedule to a certain degree, but I understand that. That's okay. I'm not the director myself, but I'm the assistant director’. (P3) |

| Taking responsibility |

|

‘In the end I'm the one making the decision about what I eat and which medication I take. So, I think that I have the ultimate responsibility [about my health]’ (P7) |

| Staying optimistic |

|

‘My optimism is an instrument to fight the situation. Every day I want to be happy with everything that's surrounding me. Because of the cancer I am much more aware of that, which is also an instrument to feel stronger’ (P7) |

| Seeking distraction |

|

‘For me, that [seeking distraction] is very important. […] I've picked up an old stamp collection again, that's a mess now. Well yeah, I'm looking for a purpose and distraction—when it's not possible with others, you also have to keep yourself busy’. (P13) |

| Acknowledging your symptoms and finding acceptance |

|

‘I dare to speak up for everything—when I'm talking with other people—I do not care what they say. I tell them about my limitations, so that they know about it’. (P1) |

| Seeking reassurance |

|

‘There are so many things that can scare you, because you simply do not know. I need someone who says “you do not have to worry”. It is normal or it will pass by, or you have to learn how to deal with it in life’. (P9) |

I think it's about making a plan for yourself. […] Regarding my disease, I made a living will. […] I also talked to my partner about some things, how I want things to be later on. (P16)

Many participants—both survivors and incurably ill patients—described that their health behaviours changed after or during their disease. They mentioned being more aware to adopt a healthy life style (e.g., by having more exercise), paying attention to nutrition and limiting or quitting alcohol consumption and smoking.

You can ensure that your life remains your life as much as possible. That is very important, because often when people get sick they no longer look for solutions. That is understandable, because you have to process many things. Well, after this you try to pick up your life and keep your body in shape, and not just sit and watch the world go by, waiting until it's your time. Because then it will be over in no time. (P20)

Participants endorsed the importance to take certain responsibility for their own well‐being: listen to your body, seek help when necessary and remain critical to what their healthcare provider tells. Some participants indicated that they wanted to deal with symptoms on their own first, with additional help if necessary.

Participants endorsed the importance to stay optimistic, trying to make the best of the situation. Mainly incurably ill participants mentioned that it is not helpful to feel sorry for yourself, to look forward rather than backward, try to enjoy life and do the things they want to do, and focus on what is still possible rather than what is no longer possible.

Since my health deteriorated last year I said to myself; I just want to do positive things. Anything negative is wasted time. You get angry sometimes, then I take a breath and look at it positively again. I do not want to waste time to negativity anymore. So when things are negative, I take a breath, and then I go on with other, happy things. (P21)

Participants specified that it helps to seek distraction: keep yourself busy and think about the disease as little as possible. It also helped them to acknowledge their symptoms and to find acceptance. For example, accept that you cannot control everything. Incurably ill patients mentioned their acceptance that cancer is part of their life. Furthermore, participants adjusted their personal goals and made less strict demands to themselves. Telling people about your disease and limitations and seeking reassurance (e.g., needing confirmation from people every now and then not to worry about things) were also mentioned.

There are so many things that can scare you, because you simply do not know. I need someone who says ‘you do not have to worry’. It is normal or it will pass by, or you have to learn how to deal with it in life. (P9)

3.3. Participants' perspectives on Oncokompas

3.3.1. Positive aspects of Oncokompas

Many participants mentioned the added value of Oncokompas (Table 4). There were no major differences in experiences between survivors and incurably ill patients. Oncokompas enabled participants to self‐manage their symptoms. The given advice can be applied immediately and without help of a healthcare provider. Furthermore, Oncokompas allows participants to monitor their symptoms, enables them to compare their well‐being over time and helps prioritising symptoms, based on the traffic light system. Red scores on topics could be a stimulant to take action. It was appreciated when the colour system matched a participant's own feelings regarding specific symptoms.

TABLE 4.

Positive aspects of Oncokompas according to participants

| Themes | Subthemes | Example of a subtheme quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Enabling patients to self‐manage |

|

‘The red scores [on a topic in Oncokompas]—then apparently you suffer from it [the symptoms] and it needs attention. Then I have a look [at the information and advice] and think “Do I recognize this? What do I do with it? Can I do something about it on my own, or do I need help?” And with the orange scores I just have a look “What's going on here? And how can I prevent that it [the topic] turns from an orange score into a red score? How do I get it back into green?” That I do not suffer from it anymore’. (P15) |

| Personal library/resources |

|

‘[I've learned] that there are many options to get support. And now you know exactly—well, that it is advised to get support or not. Or that the advice is to talk about certain things with people in your environment, that helped me’. (P16) |

| Discuss symptoms with healthcare provider |

|

‘For example, I can print my results. If I can take my results to my general practitioner or whoever, so I can say “Well, look at this, this is the advice I got [from Oncokompas].” I think that's useful’. (P9) |

| Reliability |

|

‘I think that it is easier for people to find information established by research among cancer patients themselves. You can find a lot of information on the Internet about what can happen to you, and so many websites tell you different things. So, I think that this [Oncokompas] is very nice to have’. (P20) |

| Accessibility |

|

‘I thought that it was pleasant to just use it [Oncokompas] by myself, at home’. (P16) |

| Why recommend Oncokompas to other patients? |

|

‘I think—for people who are not able to—or who do not want to—for whatever reason—search for information by themselves and to be empowered …—because that is necessary when you are in the hospital, to be assertive. I think that this [Oncokompas] can be very useful for those people’. (P3) |

The added value of Oncokompas being a personal online library was described, offering a fast and simple way to obtain information and advice, which participants could turn back to 24/7. It was appreciated that Oncokompas covers many topics profoundly and provides an overview of supportive care options. Additionally, the information in Oncokompas on the psychological impact of cancer was appreciated.

What I really appreciated was that the psychological impact of being ill is discussed extensively [within Oncokompas]. When you talk with the physician in the hospital, that's about the medical—the physical things. Also, some basic questions when you come in, like ‘how are you?’. But then it stops. […] For me that's more important [the psychological impact] than the physical side of being ill. (P15)

Participants positively valued being able to print their results in Oncokompas to discuss their results with their healthcare provider. Also, the reliability of Oncokompas and its accessibility were described as valuable. The application is evidence‐based and it is pleasant being able to use Oncokompas at home.

I think that it is easier for people to find information established by research among cancer patients themselves. You can find a lot of information on the Internet about what can happen to you, and so many websites tell you different things. So, I think that this [Oncokompas] is very nice to have. (P20)

Furthermore, the application being available on your tablet—besides availability on a computer—was appreciated.

The majority mentioned that they would recommend Oncokompas to fellow patients. However, participants indicated that it would depend on the specific person. They would recommend Oncokompas, because it could provide solutions that you do not think about yourself immediately and that it could be especially useful for patients who are less assertive.

Those tips, maybe there are some things that—maybe not when all topics scored green, but if a topic is orange or red, than you can get some nice suggestions [from Oncokompas] that you would not think of yourself. (P5)

In addition, it was mentioned that Oncokompas could help patients to reflect on their situation and to take care of symptoms by themselves.

3.3.2. Experiences relating to Oncokompas' content, its technical aspects and functional aspects, and actual usage

An overview of patients' experiences with Oncokompas is provided in Table 5. The themes and some underlying subthemes are discussed below. Regarding Oncokompas' content, several downsides were mentioned. Some participants thought the content was confronting or content felt not applicable. For example, advice could feel judgmental or ‘too intense’, or the provided information and advice were already known.

TABLE 5.

Experiences during usage of Oncokompas and recommendations for further improvements

| Themes | Subthemes | Example of a subtheme quotation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content | … is confronting |

|

‘For example, with the topic “activities of daily living.” I am less fit and then I got the advice to get a personalized rehabilitation plan. Then I just thought like “Well, that's solution is just too ‘heavy’ for my problems. Because I just think I'm less fit, but that applies for many people. I just have to exercise and walk more than I do now, but a personalized rehabilitation plan … […]” That's no tailored advice.’ (P9) |

| … feels not applicable |

|

‘—that topic is about fatigue. Well, then you can read all about that and about what you can do. That you have to exercise more. Well yeah … I know all those things. And my physiotherapist also tells me that. […] to be honest, it does not get me anywhere’. (P22) | |

| … is missing |

|

‘An orange score—your social life [the topic]. It is only about loneliness. Well, I am not lonely. People who have cancer may feel lonely. […] For me it's to limited. Your social life, when you have always been a member of a sport club and you cannot walk anymore because your leg has been amputated because of cancer, that's something different than being lonely, right? I think that [the information and advice] is too limited’. (P3) | |

| … is difficult to understand |

|

‘Then Oncokompas tells me, ‘Please contact your healthcare provider’. Well … who is that healthcare provider? I have like three, four physicians …’ (P9) | |

| Technical aspects | Structure of the application |

Flexibility lacks within the application:

|

‘And then you cannot go back to the overview of all the topics [within Oncokompas]. I tried, but it is not possible. […] and when you start the questions, you cannot go back. But you should be able to go back’. (P2) |

| Accessibility |

|

‘I was thinking—it should be available for everyone. […] when you first have to create an account—that's the downside—and of course I lost my password … it is accessible, because of course you can create an account. But for me it is a barrier. […] when you just want to have a quick look, you have to create an account’. (P9) | |

| Preferred settings |

|

‘That depends on the stage of the disease you are in [wanting to receive reminders to fill in Oncokompas]. Basically, you are getting better over time. However, not with every type of cancer, but often people get better. So, I think then there is less need. […] I would say, a little more often in the initial phase of the disease’. (P3) | |

| Functional aspects | User instructions |

Within the application:

Concerning the application:

|

‘Because initially, I received [the invitation for] Oncokompas by mail, right? For me it was a bit unclear what I could do with it [Oncokompas] exactly. Then I just started to use it anyway’. (P2) |

| Time investment |

|

“And just add information on how much time it takes to address that specific topic. That you say something like—normally it takes four minutes, or ten minutes or whatever. So that someone can say “I'll do that topic next time.”’ (P2) | |

| Peer‐to‐peer contact |

|

‘For example, a small forum—[…] that [tips from other people with cancer] would be nice’. (P6) | |

| Reminders and updates |

|

‘At one point I was using it [Oncokompas] and when I got tired, I thought “I'll let it rest for a while.” And then I was busy again with 1001 other things and you have to be reminded to use it [Oncokompas] again. […] it would be useful then [to get a reminder]’. (P7) | |

| Usage | Motivation |

|

‘When my situation changes and it gets worse—well, I see it [Oncokompas] as a reference book, where I can find information about this and that, about what I can do myself. Or where I can find help. […] when it's not necessary I think it's nonsense to use it [Oncokompas]. You know, like when I am talking to you on the phone right know—I just feel good. I do not feel the urge to read information [in Oncokompas] about what could happen to me, so to speak’. (P22) |

| Reasons for non‐use |

|

‘I am sure that it [Oncokompas] will support me in the future, but at the moment it's so busy—and it takes a lot of energy to sit behind a laptop. So that's why it has not happen yet [using Oncokompas]’. (P20) |

You get these supportive care options and in some cases I thought; this is too extreme or too generic. Or I got the advice to contact my GP, well … I thought of that myself already. That's of no use. […] For me it was too generic. (P9)

It was mentioned that certain content in Oncokompas was missing, such as advice on specific symptoms. Additionally, participants indicated that some content was difficult to understand. For example, the complexity of the PROMs to monitor their symptoms. Furthermore, it could be difficult to interpret to which healthcare provider Oncokompas refers.

Then Oncokompas tells me, ‘Please contact your healthcare provider’. Well … who is that healthcare provider? I have like three, four physicians … (P9)

Regarding technical aspects of Oncokompas, participants mentioned the structure of the application was not optimal. For example, flexibility lacks within the application. Several other technical aspects related to the accessibility of Oncokompas. It would be appreciated having the possibility to get access to Oncokompas on mobile phones. Furthermore, participants preferred to set settings in Oncokompas their selves. For example, how often you want to receive reminders for Oncokompas.

Several functional aspects were mentioned by the participants, related to user instructions, time investment and peer‐to‐peer contact. Regarding the use of Oncokompas, participants mentioned that it would be helpful to add additional instructions on how to use Oncokompas. Concerning time investment, participants mentioned that filling in questions within Oncokompas is too time‐consuming. It would be useful to indicate how much time it takes to complete a topic in the application at the beginning. Reminders and updates can motivate to use Oncokompas periodically and notify patients that new content is available in Oncokompas. To facilitate peer‐to‐peer contact, it was mentioned that it would be helpful to add a functionality making it possible to exchange tips with peers.

Participants also described their motivation to use Oncokompas or their reasons for non‐use. Concentration problems, a busy daily schedule or having problems with the Oncokompas registration (because of technical problems or because the invitation e‐mail ended up in the spam folder) were reasons for not using Oncokompas. Others, who used Oncokompas at least once, indicated that it was hard to get motivated and to follow‐up the advice provided in Oncokompas in their daily life (e.g., advice about exercising). Experiencing high symptom burden could stimulate using Oncokompas, compared to experiencing no or few symptoms. Also mentioned was to get more motivated to use the application, when the healthcare provider would have access to the results within Oncokompas.

Participants' expectations regarding future use of Oncokompas varied. Mainly incurably ill patients indicated that it would depend on their disease progression how often they would use Oncokompas in the future. Survivors' expectations varied from using it once per month, or once per quarter, to expecting no further use at all due to having a stable health status.

Participants' opinion about the best moment to provide access to Oncokompas varied. Participants wished they had access to Oncokompas at an earlier timepoint (now they got access months after their treatment or after years of being ill): advices and supportive care options were often already known. Some thought it would be best to get access to Oncokompas at diagnosis. Then, people often have many questions and insecurities. Others stated that it would be ‘too much’ when Oncokompas would be offered directly at diagnosis. Some preferred to get access to Oncokompas during treatment, because this would enable them to monitor side‐effects of treatment. However, participants mentioned that after treatment they had time to think about all their experiences and be more at ease, which could be helpful for using the application. It was also suggested to offer access to Oncokompas repeatedly during the cancer trajectory. For example, when impactful events happen (e.g., hospital admissions).

4. DISCUSSION

This study provided insight in self‐management strategies of survivors and incurably ill patients to cope with cancer and their experiences with the fully automated BIT Oncokompas.

In line with earlier studies (Budhwani et al., 2019; Dunne et al., 2017; Heijmans et al., 2014; D. Howell et al., 2021; Thomsen et al., 2010; van Dongen et al., 2020), participants' strategies to cope with cancer varied: taking care of oneself, changing health behaviours and adopting a healthy life style. In addition, participants noted the importance to acknowledge their symptoms and find acceptance. Self‐management strategies related to both problem‐focused coping (i.e., removing, evading or diminishing [impact of] stressful situations) and emotion‐focused coping (i.e., minimising emotional distress) (Carroll, 2013). The objectives of self‐management applications as Oncokompas correspond well with survivors' and patients' views on how they deal with cancer: these applications enable them to be in charge of their life as long as possible, providing automated information (24/7) on how to take actions to meet their supportive care needs, and encourage them to take a certain responsibility for their own well‐being.

Within current healthcare system, it is increasingly acknowledged that not only healthcare professionals are experts regarding patients' diseases; also patients themselves are experts, with most knowledge about their illness experience and their strategies to deal with cancer (Karazivan et al., 2015). D. Howell et al. (2021) recommended several actions to provide self‐management support in routine care. Actively involving patients in their own care and engaging them in self‐management at the earliest moment possible, stimulating and guiding them to apply self‐management strategies to cope with acute and chronic problems, could maximise the benefits of self‐management interventions and stimulate patients to be more engaged in the self‐management of their own well‐being—with knowledge, skills and confidence to self‐manage their illness (D. Howell et al., 2021). Identifying patients' self‐management strategies and explaining how interventions such as Oncokompas could contribute to these strategies may increase adoption among patients. Furthermore, techniques like motivational interviewing—creating a constructive conversation about behaviour change (Rollnick et al., 2008)—and offering self‐management support (V.N. Slev et al., 2017) might help patients to get motivated to use BITs in their daily life.

Regarding participants' experiences with Oncokompas, some described Oncokompas' added value on their self‐management strategies, while others mentioned that using Oncokompas had no additional value. Our results are in line with previous studies, investigating the feasibility of Oncokompas (Duman‐Lubberding et al., 2016; Melissant et al., 2018). For example, the usefulness of Oncokompas in general by providing useful information and advice (Duman‐Lubberding et al., 2016; Melissant et al., 2018). In contrast to previous studies which mentioned that feasibility was positively affected by the user‐friendliness of Oncokompas, the present study shows the potential to refine the structure of Oncokompas on its technical level to optimise Oncokompas' ease of use and anticipating on reasons for non‐use such as concentration problems or a lack of time. Improving user‐friendliness of Oncokompas could stimulate patients to use the application more frequently and thereby positively affect patient activation levels.

This study emphasises the importance to continuously evaluate interventions in collaboration with end‐users, as is stressed by Catwell and Sheikh (2009). For example, participants specified that information within Oncokompas did not match with their preferences or their personal situation, corresponding to the results of the RCT among cancer survivors (A. van der Hout, van Uden‐Kraan, et al., 2021). This indicates that further tailoring could improve Oncokompas. Participants also gave recommendations for further development of Oncokompas regarding its content, and functional and technical aspects. Some of these—for example, further tailoring of Oncokompas and adding additional instructions on how to use Oncokompas—may also stimulate patients to use Oncokompas who otherwise would not use the application. For example, due to concentration problems or a lack of time, because it could decrease the time patients have to invest to use Oncokompas.

Patients' strategies to cope with cancer vary per individual and can change over time (Lashbrook et al., 2018). This suggests that there is no ‘perfect’ moment to provide patients access to self‐management applications such as Oncokompas, which corresponds to our findings that the preferred moment to get access to Oncokompas varied. However, understanding the diversity of patients' preferences regarding access to self‐management applications is essential when offering patient‐centred care, tailored to the individual. Based on the current evidence, it is recommended to offer patients access to self‐management applications at different time points in the cancer trajectory. Using a tailored approach when offering interventions to end‐users might be helpful to stimulate patients to use BITs like Oncokompas and increase its benefits.

A strength of this study is that both cancer survivors and incurably ill patients participated. We did not find important differences between these two study populations. However, HNC survivors are a specific patient group, due to their tumour location. The results of the randomised controlled trial among cancer survivors showed most effects of Oncokompas on HRQOL and symptom burden in HNC survivors (A. van der Hout et al., 2020), which might be explained by the large variety of symptoms compared to survivors of other cancer types. This may affect the generalizability of this study among patients with other cancer types.

Another limitation of this study is the elapsed time since the (non)use of Oncokompas, which varied among participants (2 weeks to 2.5 months) due to the recruitment procedure of both patient groups. For participants who used Oncokompas more recently, it may have been easier to recall their experiences. In addition, patients' experiences are specific for Oncokompas; it might be difficult to generalise the results to other web‐based applications. Furthermore, it is possible that participation bias occurred because patients who experience severe symptom burden or who experience more distress in their daily life might be less open to study participation which could affect the representativeness of the results. Also, a convenience sampling method was used for data collection, negatively affecting generalizability of the study (Etikan, 2016). Lastly, no background information is available about non‐responders and their reasons for non‐participation.

In conclusion, cancer survivors and incurably ill cancer patients use various self‐management strategies to cope with the impact of cancer in daily life. Objectives of fully automated behavioural intervention technologies as Oncokompas correspond well with these strategies: taking a certain responsibility for their own well‐being and being in charge of their life as long as possible by obtaining automated information (24/7) on symptoms and tailored supportive care options.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study is funded by ZonMw, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (project number: 844001105).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

IVdL reports grants from the Dutch Cancer Society ‐ Alpe d'Huzes Foundation, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the SAG Foundation – Zilveren Kruis Health Care Assurance Company, Danone Ecofund – Nutricia, the Dutch Society Head and Neck Cancer Patients – Michel Keijzer Foundation, Red‐kite (distributor of eHealth tools) and Bristol‐Myers Squibb. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Schuit, A. S. , van Zwieten, V. , Holtmaat, K. , Cuijpers, P. , Eerenstein, S. E. J. , Leemans, C. R. , Vergeer, M. R. , Voortman, J. , Karagozoglu, H. , van Weert, S. , Korte, M. , Frambach, R. , Fleuren, M. , Hendrickx, J.‐J. , & Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2021). Symptom monitoring in cancer and fully automated advice on supportive care: Patients' perspectives on self‐management strategies and the eHealth self‐management application Oncokompas. European Journal of Cancer Care, 30(6), e13497. 10.1111/ecc.13497

Funding information ZonMw, Grant/Award Number: 844001105

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the participants of this study did not consent to their data being shared. Requests to access the data should be directed to IVdL (via im.verdonck@amsterdamumc.nl).

REFERENCES

- Barlow, J. , Wright, C. , Sheasby, J. , Turner, A. , & Hainsworth, J. (2002). Self‐management approaches for people with chronic conditions: A review. Patient Education and Counseling, 48(2), 177–187. 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00032-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. Res des Quant Qual Neuropsychol Biol, 2, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample‐size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Heal, 13(2), 201–216. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–25. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani, S. , Wodchis, W. P. , Zimmermann, C. , Moineddin, R. , & Howell, D. (2019). Self‐management, self‐management support needs and interventions in advanced cancer: A scoping review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 9(1), 12–25. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, L. (2013). Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. In Gellman M. D. & Turner J. R. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Catwell, L. , & Sheikh, A. (2009). Evaluating eHealth interventions: The need for continuous systemic evaluation. PLoS Medicine, 6(8), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert, C. A. , Farragher, J. F. , Hemmelgarn, B. R. , Ding, Q. , McKinnon, G. P. , & Cheung, W. Y. (2019). Self‐management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review and evaluation of intervention content and theories. Psycho‐Oncology, 28(11), 2119–2140. 10.1002/pon.5215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman‐Lubberding, S. , van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , Jansen, F. , Witte, B. I. , van der Velden, L. A. , Lacko, M. , et al. (2016). Feasibility of an eHealth application “OncoKompas” to improve personalized survivorship cancer care. Support Care Cancer, 24(5), 2163–2171. 10.1007/s00520-015-3004-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, S. , Mooney, O. , Coffey, L. , Sharp, L. , Timmons, A. , Desmond, D. , Gooberman‐Hill, R. , O'Sullivan, E. , Keogh, I. , Timon, C. , & Gallagher, P. (2017). Self‐management strategies used by head and neck cancer survivors following completion of primary treatment: A directed content analysis. Psycho‐Oncology, 26(12), 2194–2200. 10.1002/pon.4447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haberlin, C. , O'Dwyer, T. , Mockler, D. , Moran, J. , O'Donnell, D. M. , & Broderick, J. (2018). The use of eHealth to promote physical activity in cancer survivors: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(10), 3323–3336. 10.1007/s00520-018-4305-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijmans, M. , Waverijn, G. , & Van Houtum, L. (2014). Zelfmanagement, wat betekent het voor de patiënt? NIVEL. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D. , Harth, T. , Brown, J. , Bennett, C. , & Boyko, S. (2017). Self‐management education interventions for patients with cancer: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer, 25(4), 1323–1355. 10.1007/s00520-016-3500-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D. , Mayer, D. K. , Fielding, R. , Eicher, M. , Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. , Johansen, C. , Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, E. , Foster, C. , Chan, R. , Alfano, C. M. , Hudson, S. V. , Jefford, M. , Lam, W. W. T. , Loerzel, V. , Pravettoni, G. , Rammant, E. , Schapira, L. , Stein, K. D. , & Koczwara, B. (2021). Management of cancer and health after the clinic visit: A call to action for self‐management in cancer care. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 113(5), 523–531. 10.1093/jnci/djaa083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karazivan, P. , Dumez, V. , Flora, L. , Pomey, M. P. , Del Grande, C. , Ghadiri, D. P. , Fernandez, N. , Jouet, E. , Las Vergnas, O. , & Lebel, P. (2015). The patient‐as‐partner approach in health care. Academic Medicine, 90(4), 437–441. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashbrook, M. P. , Valery, P. C. , Knott, V. , Kirshbaum, M. N. , & Bernardes, C. M. (2018). Coping strategies used by breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 41(5), E23–E39. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melissant, H. C. , Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. , Lissenberg‐Witte, B. I. , Konings, I. R. , Cuijpers, P. , & Van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. (2018). ‘Oncokompas’, a web‐based self‐management application to support patient activation and optimal supportive care: A feasibility study among breast cancer survivors. Acta Oncologica, 57(7), 924–934. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1438654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L. S. , Norris, J. M. , White, D. E. , & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, L. , & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21. 10.2307/2136319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick, S. , Miller, W. , & Butler, C. (2008). Motivational interviewing in health care. Helping patients change behavior. New York: The Guilford Press. 1+‐224 [Google Scholar]

- Schuit, A. S. , Holtmaat, K. , Hooghiemstra, N. , Jansen, F. , Lissenberg‐Witte, B. I. , Coupé, V. M. H. , van Linde, M. E. , Becker‐Commissaris, A. , Reijneveld, J. C. , Zijlstra, J. M. , Sommeijer, D. W. , Eerenstein, S. E. J. , & Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2019). Efficacy and cost‐utility of the eHealth application “Oncokompas”, supporting patients with incurable cancer in finding optimal palliative care, tailored to their quality of life and personal preferences: A study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Palliative Care, 18(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12904-019-0468-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler, A. , Klaas, V. , Tröster, G. , & Fagundes, C. P. (2017). eHealth and mHealth interventions in the treatment of fatigued cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psycho‐Oncology, 26(9), 1239–1253. 10.1002/pon.4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slev, V. N. , Mistiaen, P. , Pasman, H. R. W. , Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. , van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , & Francke, A. L. (2016). Effects of eHealth for patients and informal caregivers confronted with cancer: A meta‐review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 87, 54–67. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slev, V. N. , Pasman, H. R. W. , Eeltink, C. M. , Van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , Verdonck‐De Leeuw, I. M. , & Francke, A. L. (2017). Self‐management support and eHealth for patients and informal caregivers confronted with advanced cancer: An online focus group study among nurses. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1), 55. 10.1186/s12904-017-0238-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen, T. G. , Rydahl‐Hansen, S. , & Wagner, L. (2010). A review of potential factors relevant to coping in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(23–24), 3410–3426. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. , Sainsbury, P. , & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32‐item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care., 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triberti, S. , Savioni, L. , Sebri, V. , & Pravettoni, G. (2019). eHealth for improving quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 74(January), 1–14. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hout, A. , Holtmaat, K. , Jansen, F. , Lissenberg‐Witte, B. I. , van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P. , Hardillo, J. A. , de Jong, R. J. B. , Tiren‐Verbeet, N. L. , Sommeijer, D. W. , de Heer, K. , Schaar, C. G. , Sedee, R. J. E. , Bosscha, K. , van den Brekel, M. W. M. , Petersen, J. F. , Westerman, M. , Honings, J. , Takes, R. P. , … Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2021). The eHealth self‐management application ‘Oncokompas’ that supports cancer survivors to improve health‐related quality of life and reduce symptoms: Which groups benefit most? Acta Oncol (Madr), 60(4), 403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hout A., van Uden‐Kraan C., Holtmaat K., Jansen F., Lissenberg‐Witte B., Nieuwenhuijzen G, et al. Reasons for not reaching or using web‐based self‐management applications , and the use and evaluation of Oncokompas among cancer survivors. (2021). Internet Interventions, 100429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- van der Hout, A. , van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , Holtmaat, K. , Jansen, F. , Lissenberg‐Witte, B. I. , Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P. , Hardillo, J. A. , Baatenburg de Jong, R. J. , Tiren‐Verbeet, N. L. , Sommeijer, D. W. , de Heer, K. , Schaar, C. G. , Sedee, R. J. E. , Bosscha, K. , van den Brekel, M. W. M. , Petersen, J. F. , Westerman, M. , Honings, J. , Takes, R. P. , … Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2020). Role of eHealth application Oncokompas in supporting self‐management of symptoms and health‐related quality of life in cancer survivors: A randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology, 21(1), 80–94. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30675-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hout, A. , van Uden‐Kraan, C. F. , Witte, B. I. , Coupé, V. M. H. , Jansen, F. , Leemans, C. R. , Cuijpers, P. , van de Poll‐Franse, L. V. , & Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2017). Efficacy, cost‐utility and reach of an eHealth self‐management application “Oncokompas” that helps cancer survivors to obtain optimal supportive care: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 18(1), 228. 10.1186/s13063-017-1952-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen, S. I. , de Nooijer, K. , Cramm, J. M. , Francke, A. L. , Oldenmenger, W. H. , Korfage, I. J. , Witkamp, F. E. , Stoevelaar, R. , van der Heide, A. , & Rietjens, J. A. C. (2020). Self‐management of patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review of experiences and attitudes. Palliative Medicine, 34(2), 160–178. 10.1177/0269216319883976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gemert‐Pijnen, J. E. W. C. , Nijland, N. , van Limburg, M. , Ossebaard, H. C. , Kelders, S. M. , Eysenbach, G. , & Seydel, E. R. (2011). A holistic framework to improve the uptake and impact of eHealth technologies. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(4):e111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the participants of this study did not consent to their data being shared. Requests to access the data should be directed to IVdL (via im.verdonck@amsterdamumc.nl).