Abstract

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common cancer worldwide. While most BCC cases respond to surgical management, complex BCC often presents treatment challenges for patients unsuitable for, or refractory to, surgery and radiotherapy—limiting treatment options. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (HHI) have emerged as an important treatment option for patients with complex BCC—providing a durable treatment modality and improved clinical outcomes. We present a case series of 10 patients with complex BCC treated with sonidegib, an oral HHI, at a dose of 200 mg once daily for a mean duration of 6 months and a mean follow‐up of 7 months. Of these patients, sonidegib monotherapy was curative in eight cases. Of the remaining two patients, treatment with sonidegib arrested tumor progression and decreased tumor size to a point where surgical removal was straightforward. The positive treatment response we observed supports use of sonidegib as an effective treatment option for patients with complex BCC.

Keywords: basal cell carcinoma, hedgehog pathway inhibitor, sonidegib

1. INTRODUCTION

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy worldwide, with global incidence increasing annually. 1 , 2 Approximately 2 million cases are diagnosed annually in the US. 1 , 2 , 3 BCCs are classified histologically as nodular, superficial, morpheaform, infiltrative, micronodular, basosquamous, or as mixed histology. 2 Aggressive subtypes (morpheaform, infiltrative, micronodular, and basosquamous) tend to have a high recurrence rate and cause extensive local tissue destruction. 2 Traditional treatment methods for BCC include surgical excision, radiotherapy, electrosurgery, curettage, intralesional and topical chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and photodynamic therapy. 2 , 3 However, in patients with complex BCC, treatment is often challenging. 3 Complex BCCs include metastatic BCC (mBCC) and locally advanced BBC (laBCC), which are primary, recurrent, and/or metastatic tumors not easily amenable to surgery or radiotherapy, and can result in significant local spread and tissue destruction due to significant tumor enlargement, causing substantial morbidity and limiting treatment options. 2 , 3

Hedgehog pathway inhibitors (HHIs) present an alternative treatment for patients with complex BCC. Most BCCs exhibit hedgehog signaling pathway overactivation due to somatic mutations in Smoothened 2 , 3 ; HHIs selectively inhibit smoothened, thereby blocking aberrant hedgehog signaling. 4 Sonidegib (Odomzo®; Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.), is an HHI approved in the US, EU, Switzerland, and Australia to treat adults with laBCC either unsuitable for, or which has recurred following, surgery or radiotherapy. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 In Switzerland and Australia, sonidegib is also approved to treat mBCC. 5 , 7 In Australia, the dispensed price for the maximum quantity of 30 sonidegib capsules (200 mg) is $7982.59, while the subsidized cost for general patients is $41.30. 8

Results from clinical trials support use of sonidegib to reduce BCC lesion size and control tumor progression. In the final 42‐month analysis of the BOLT trial, objective response rate (ORR) per central review for patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg once daily was 48% (95% confidence interval [CI] 37%–60%) for laBCC and mBCC combined and 56% (95% CI 43%–68%) for laBCC alone. 9 Disease control rates exceeded 90%. 9 At 12 months, 92.3% of patients with complex BCC receiving sonidegib 200 mg daily demonstrated substantial tumor shrinkage, and durable responses were observed. 10 However, there are limited data regarding disease progression with sonidegib 200 mg daily in patients with laBCC. In the BOLT 6‐month analysis, <10% of patients with laBCC experienced disease progression, 11 while in the 12‐month analysis, 19.1% had disease progression or died. 10 At the final BOLT analysis, median progression‐free survival for patients with laBCC receiving sonidegib 200 mg was 22.1 months. 9

We present a case series demonstrating treatment with sonidegib‐controlled BCC tumor progression that was curative for most patients studied—challenging the current understanding that sonidegib controls, but does not completely clear complex BCC.

2. CASE PRESENTATIONS

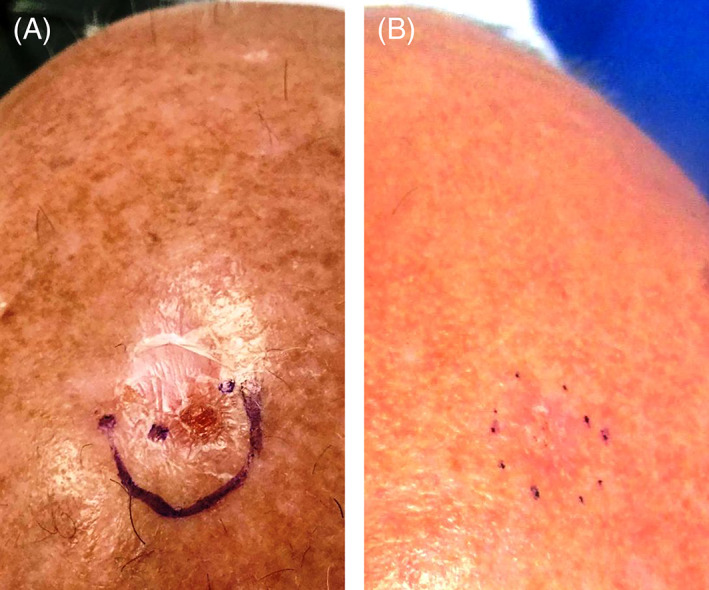

Ten patients with previously untreated primary laBCC presented to two dermatology offices in Sydney and Griffith, New South Wales, Australia, for treatment with sonidegib. All patients provided informed consent for publication and this study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles. All patients received oral sonidegib 200 mg once daily. Medical records were examined to determine BCC treatment outcome. BCC clearance was confirmed histologically by punch biopsy, excisional biopsy and frozen section (as part of Mohs surgery) in eight patients, and dermoscopically in two patients. The average age of patients was 57 years and 50% were female (Table 1). In these patients, tumor sites necessitated complicated surgical repair (even following Mohs surgery) and were not ideal for radiotherapy at the time of presentation (e.g., hair‐bearing scalp, sites involving free edges, or tumors with underlying or adjacent mucosa and/or vital structures). While the scalp tumor in Patient #2 was at a site with advanced alopecia areata, sonidegib was used as the patient declined radiotherapy (Figure 1). Severe actinic damage also prompted concern that radiotherapy to the scalp for multiple lesions of aggressive BCC subtype, would increase risk of subsequent aggressive BCC. Prior to sonidegib treatment, nine patients were biopsied for confirmation of diagnosis or presented with biopsy results, while one patient presented with incomplete clearance from Mohs surgery, having residual tumor and perineural invasion confirmed on paraffin sections. All pre‐treatment tumors had an average diameter of 5–10 mm, except for two patients with mean tumor diameters of 15 mm and <5 mm, respectively. The average duration of sonidegib treatment was 6 months with an average follow‐up duration of 7 months. Eight patients had no residual BCC following sonidegib treatment (Supplemental Image 1). The remaining patients experienced sufficient lesion size reductions to enable removal of residual tumor by Mohs surgery (Supplemental Image 2). The most common adverse events (AEs) observed were muscle spasms and alopecia, with 50% of patients reporting for each, followed by fatigue (30%), dysgeusia (30%), loss of appetite (30%), hyperhidrosis (10%), arthralgia (10%), and nausea (10%).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Patient number | Age (years) | Sex | Tumor subtype | Tumor location | Duration of treatment (months) | Subsequent definitive treatment | Adverse events during treatment | Outcome of sonidegib therapy | Duration of follow‐up (months) | Post‐treatment mean tumor diameter (mm) | Reduction in tumor size (%) and change in appearance following treatment (if any) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 54 | F | Nodulocystic, superficial | Left nasal ala | 12 | None | Dysgeusia, muscle spasms, hyperhidrosis | No residual tumor on excisional biopsy | 4 | 5–10 | 50 |

| 2 | 65 | M | Morpheaform | Scalp | 6 | None | Muscle spasms | No residual tumor on excisional biopsy | 1 | 12 |

0 From nodule to erythematous plaque |

| 3 | 62 | M | Nodular | Right nasal ala | 3 | None | Muscle spasms, nausea, alopecia | No residual tumor on frozen section biopsy | 13 | 5–10 |

75 From nodule to erythematous plaque |

| 4 | 67 | M | Nodular | Right inner canthus | 7 | None | Alopecia (outer eyebrows) | No evidence of BCC on dermoscopy | 5 | 5–10 |

0 From nodule to sclerotic plaque |

| 5 | 77 | F | Morpheaform | Right alar crease | 3 | Mohs surgery | Alopecia (scalp), loss of appetite (mild), fatigue (mild) | Reduction of lesion size | 4 | 5–10 |

75 From sclerotic plaque to papule |

| 6 | 46 | F | Nodular, superficial | Right nasal ala | 8 | Mohs surgery | Alopecia (scalp), loss of appetite (mild) | Reduction of lesion size | 7 | 5–10 |

0 From nodule to erythematous plaque |

| 7 | 37 | F | Morpheaform and infiltrative with perineural invasion | Right eyebrow | 2 | None | Muscle spasms, fatigue (moderate) | No evidence of BCC on dermoscopy | 8 | No discernible lesion | 100 |

| 8 | 49 | F | Nodular | Scalp | 4 | None | Dysgeusia, arthralgia (mild), fatigue (mild) | No residual tumor on punch biopsy | 7 | <5 |

90 From sclerotic plaque to atrophic plaque |

| 9 | 56 | M | Infiltrative | Left upper lip | 3 | None | Muscle spasms | No evidence of BCC on dermoscopy | 10 | No discernible lesion | 100 |

| 10 | 59 | M | Nodular | Right dorsal nose and right lower eyelid | 9 | None | Alopecia, dysgeusia, loss of appetite (mild) | No evidence of BCC on dermoscopy | 11 | No discernible lesion | 100 |

Note: Mean tumor diameter was calculated as the average of two perpendicular dimensions.

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male.

FIGURE 1.

Photographs of a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma in a patient (patient #2) who achieved complete clearance following treatment with sonidegib (A) before treatment and (B) after treatment with sonidegib

3. DISCUSSION

In patients with BCC, treatment objective is complete tumor clearance and preservation of function and cosmesis at the treatment site. 2 However, treatment options are limited in complex BCC, as tumors can become significantly enlarged—causing substantial local tissue invasion and destruction. 2 , 3 Consequently, surgical management can be invasive and post‐surgical cosmetic results may severely affect the quality of life of the patient. 3 Additionally, although BCC mortality is low and metastasis is rare, global incidence is rising. 1 , 2 The increasing incidence of BCC in young adults is concerning, as these patients may place a higher value on treatments with an excellent cosmetic outcome.

When comparing treatment modalities, the mean 5‐year recurrence rate for patients following radiotherapy was 15.8% for all BCC cases versus 27.7% for patients with an aggressive sclerosing subtype. 12 Similarly, the 5‐year recurrence rate for BCCs was 40% following electrodessication and curettage vs 4% for recurrent BCCs treated by Mohs surgery. 13 While the 5‐year recurrence rate for treatment with sonidegib has not been established (FDA approval in 2015), the 2‐year overall survival rate for patients with laBCC treated with sonidegib is 93.2%. 14 This rate is comparable to the 2‐year survival rate for laBCC patients treated with vismodegib, another HHI (85.5%). 15

In many patients with complex BCC, a nonsurgical approach to treatment may be the best option, especially in older patients and those with comorbidities or refractory to radiotherapy. 2 In these patients, treatment with HHIs may provide durable results. The two approved HHIs, sonidegib and vismodegib, demonstrate comparable safety profiles with similar AEs reported. Muscle spasms were the most common AE reported for both sonidegib and vismodegib, with 54% of patients receiving sonidegib 200 mg daily in the BOLT trial and 71% of patients receiving vismodegib 150 mg daily in the ERIVANCE study reporting muscle spasms during treatment. 9 , 15

Based on this case series' results, sonidegib treatment alone was curative for 80% of patients. In the remaining patients, sonidegib treatment achieved substantial reduction in tumor size, allowing any residual BCC to be more easily removed surgically. Since surgical management of complex BCC can be extensive and may cause significant morbidity, a pharmacologic treatment option that can reduce a patient's tumor burden, to the point where resective surgery is no longer required or is able to effectively clear the tumor without causing disfigurement, is of great value.

Our analysis of patients with complex BCC demonstrates that sonidegib could be considered a viable first‐line treatment option for these patients. Further examination of the long‐term recurrence and survival rates of complex BCCs in patients treated with sonidegib would be of value to provide an understanding of long‐term recurrence rates compared with other treatment options.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr Leow has received education, writing and travel support from Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.; education and travel support and speaking fees from Eli Lilly; education and travel support, advisory board honoraria and consulting fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals; and a steering committee honorarium from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Author Teh has received education and writing support from Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Supporting information

Supplemental Image 1 Photographs of a nodular BCC in a patient (patient #3) who achieved complete clearance following treatment with sonidegib (A) before treatment and (B) after treatment with sonidegib

Supplemental Image 2 Photographs of a nodular and superficial BCC in a patient (patient #6) who achieved complete clinical clearance following treatment with sonidegib and Mohs surgery (A) before treatment with sonidegib, (B) after treatment with sonidegib, and (C) after Mohs surgery

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Zehra Gundogan, VMD, of AlphaBioCom, LLC under the direction of the authors and were funded by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

Leow LJ, Teh N. Clinical clearance of complex basal cell carcinoma in patients receiving sonidegib: A case series. Dermatologic Therapy. 2022;35(2):e15217. doi: 10.1111/dth.15217

Funding informationThis work was supported by Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Asgari MM, Moffet HH, Ray GT, Quesenberry CP. Trends in basal cell carcinoma incidence and identification of high‐risk subgroups, 1998‐2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(9):976‐981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marzuka AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015;88(2):167‐179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lear JT, Corner C, Dziewulski P, et al. Challenges and new horizons in the management of advanced basal cell carcinoma: a UK perspective. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(8):1476‐1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Odomzo (sonidegib capsules). Full Prescribing Information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc., Cranbury, NJ, USA.

- 5. Australian Government Department of Health, ARTG 292262.

- 6. European medicines agency . Summary of Product Characteristics, WC500188762.

- 7. Swissmedic, Authorization Number 65065, 2015.

- 8. Sonidegib. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), Australian Government Department of Health. www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/11304Y. Accessed February 19, 2021

- 9. Dummer R, Guminksi A, Gutzmer R, et al. Long‐term efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: 42‐month analysis of the phase II randomized, double‐blind BOLT study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(6):1369‐1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dummer R, Guminski A, Gutzmer R, et al. The 12‐month analysis from basal cell carcinoma outcomes with LDE225 treatment (BOLT): a phase II, randomized, double‐blind study of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):113‐125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Migden MR, Guminski A, Gutzmer R, et al. Treatment with two different doses of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BOLT): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(6):716‐728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zagrodnik B, Kempf W, Seifert B, et al. Superficial radiotherapy for patients with basal cell carcinoma: recurrence rates, histologic subtypes, and expression of p53 and Bcl‐2. Cancer. 2003;98(12):2708‐2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leibovitch I, Huilgol SC, Selva D, Richards S, Paver R. Basal cell carcinoma treated with Mohs surgery in Australia II. Outcome at 5‐year follow‐up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(3):452‐457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lear JT, Migden MR, Lewis KD, et al. Long‐term efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced and metastatic basal cell carcinoma: 30‐month analysis of the randomized phase 2 BOLT study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(3):372‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sekulic A, Migden MR, Basset‐Seguin N, et al. Long‐term safety and efficacy of vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: final update of the pivotal ERIVANCE BCC study. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Image 1 Photographs of a nodular BCC in a patient (patient #3) who achieved complete clearance following treatment with sonidegib (A) before treatment and (B) after treatment with sonidegib

Supplemental Image 2 Photographs of a nodular and superficial BCC in a patient (patient #6) who achieved complete clinical clearance following treatment with sonidegib and Mohs surgery (A) before treatment with sonidegib, (B) after treatment with sonidegib, and (C) after Mohs surgery

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.