Abstract

There is considerable interest in the development of libraries of non‐peptidic macrocycles as a source of ligands for difficult targets. We report here the solid‐phase synthesis of a DNA‐encoded library of several hundred thousand thioether‐linked macrocycles. The library was designed to be highly diverse with respect to backbone scaffold diversity and to minimize the number of amide N−H bonds, which compromise cell permeability. The utility of the library as a source of protein ligands is demonstrated through the isolation of compounds that bind Streptavidin, a model target, with high affinity.

Keywords: Combinatorial Chemistry, DNA-Encoded Library, High-Throughput Screening, Macrocycles, Solid-Phase Synthesis

The discovery of ligands for the “undruggable proteome” is likely to require the development of new chemical matter with a greater “molecular wingspan” than traditional Lipinski‐compliant small molecules. A DNA‐encoded library (DEL) of non‐peptidic thioether macrocycles has been constructed and screened for high affinity protein ligands to a model protein, SA.

Introduction

It is generally acknowledged that molecules with some characteristics outside the “rule of 5”, [1] particularly molecular weight, will be required to engage difficult protein targets efficiently. Such target proteins lack deep binding pockets suitable for interactions with more traditional drug‐like molecules. Engagement of these protein surfaces requires larger, conformationally stable molecules capable of occupying multiple shallow pockets. To that end, macrocycles are of particular interest. [2] Powerful biological methods, such as phage display [3] and ribosome display [4] exist for the creation of large libraries of macrocyclic peptides, which have been shown to be an excellent source of ligands for many different proteins. However, with a few notable exceptions, [5] macrocyclic peptides exhibit poor cell permeability, [6] spurring interest in the development of large libraries of non‐peptidic macrocycles that would be better able to access intracellular targets. DNA‐encoded libraries (DELs) [7] are of particular interest since these can rival the size of phage display libraries. To date, only a few macrocyclic DELs have been reported. The first, created by Liu and co‐workers using DNA‐templated chemistry, employed a Wittig reaction to close the ring. [8] The most recent version of this approach has produced a library of 256 000 macrocycles from which a 40 nM ligand for insulin degrading enzyme was identified. [9] More recently, Gillingham and colleagues reported a seven cycle DEL comprised of approximately 1.4 million macrocycles in which the ring was closed via amide bond formation. [10] Ligands with μM dissociation constants were mined from this library. Both of these DELs were created by solution‐phase chemistry.

In this study, we report the development of efficient chemistry for the synthesis of DELs of thioether macrocycles by solid‐phase split and pool synthesis. [11] The construction of these libraries on TentaGel resin [12] allows them to be screened by simply mixing the beads with a fluorescently labeled protein and isolating those that retain the labeled target using a fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS). [13] This protocol, in turn, facilitates the use of targets and off targets labeled with different colored dyes, allowing ligands with a high level of selectivity for the target protein to be differentiated from those that do not. [14] We demonstrate the utility of this system by isolating macrocyclic ligands for Streptavidin (SA).

Results and Discussion

Establishment of Efficient, DNA‐Compatible Macrocyclization Conditions

We sought an efficient strategy for the on‐resin macrocyclization of peptoid‐inspired conformationally‐constrained oligomers (PICCOs) [15] that would be compatible with DNA encoding technology. A common strategy used for the creation of macrocyclic peptides is thioether formation,[ 3b , 16 ] which often relies on a cysteine residue possessing a protected thiol that is then deprotected to initiate ring closure. However, removal of some thiol protecting groups requires treatment with strong acid, which can be detrimental to the integrity of the DNA encoding tags. [17] Therefore, we focused on the S‐trimethoxyphenol (STmp) protecting group, which is removed efficiently under mild reducing conditions that are likely DNA‐compatible.

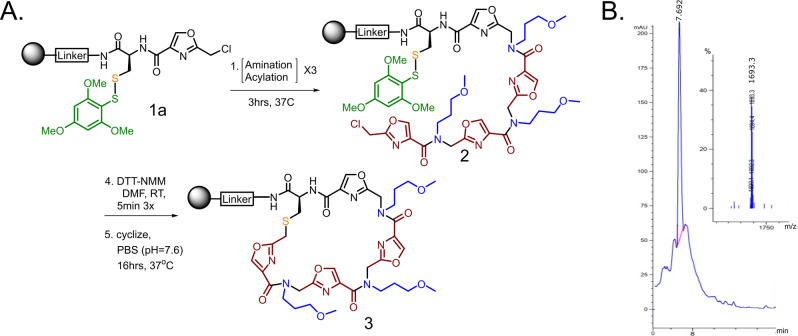

A linker designed to facilitate ionization by mass spectrometry (Linker‐2) was generated on 90 μm TentaGel‐RAM resin (Figure S1). The linker was then acylated with Fmoc‐Cys(STmp)‐OH. After removal of the Fmoc group, the amine was acylated with 2‐(chloromethyl)oxazole‐4‐carboxylic acid to generate Compound 1a (Figure 1A). To build the test PICCO, the beads were subjected to 3 rounds of amination with 3‐methoxybutylamine and subsequent acylation with 2‐(chloromethyl)oxazole‐4‐carboxylic acid to generate Compound 2 (Figure 1A). After synthesis of the linear precursor was complete, the STmp group was removed, and the beads were incubated at 37 °C for 18 hours to allow for thioether formation. Macrocyclization was then assessed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) as well as matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI). The molecular ion expected for the macrocyclic product was evident, while the peak expected from the linear precursor was not detected (Figures 1B).

Figure 1.

Assessment of PICCO macrocyclization. A) Beads displaying a linker capped with Cys‐STmp and an oxazole (Compound 1a) were subjected to three rounds of amination and acylation to generate a linear PICCO (Compound 2). Cysteine deprotection allows thioether formation, generating the macrocycle (Compound 3). B) LC/MS analysis demonstrates complete cyclization of the linear precursor. See Supporting Information (Figure S2) for complete characterization.

To explore this macrocyclization strategy more broadly and to assess the DNA‐compatibility of the reaction conditions, a DNA‐encoded, 27‐molecule “mini‐library” was generated. These compounds follow the general design depicted in Figure 2 and represent a diverse set of PICCO scaffolds (Figure S2 A). As above, Cys‐STmp‐OH and 2‐(chloromethyl)oxazole‐4‐carboxylic acid were added to 90 μm TentaGel RAM resin displaying Linker‐2. As an attachment point for DNA barcode ligation, azido‐PEG headpiece DNA (HDNA)[ 12 , 18 ] was added to the linker by copper‐catalyzed click chemistry. [19] The beads were then aliquoted into 27 wells of a 96‐well filter plate. Parallel synthesis was then carried out, specifically three cycles of amine side‐chain/backbone unit (Figure S3A) addition, deprotection of the cysteine, and cyclization. After each round of amination/acylation, an encoding DNA was enzymatically ligated to build the barcode. [12] Following cyclization, the DNA barcodes were amplified by PCR, purified, and sequenced. From the 27 test compounds, 22 showed PCR products of the expected size (Figure S3B). Of these, 20/22 provided the expected DNA sequences (Table 1). Additionally, MALDI analysis revealed the expected masses for 23 of the 27 macrocyclic compounds (Table 1, Figure S3C). In the four cases where this was not the case, no dominant peak was seen in the MALDI‐MS, indicating some failure early in the synthesis rather than simply a failure to cyclize. These data suggest that thioether formation is broadly suitable for PICCO macrocyclization and that the Cys‐STmp deprotection conditions are DNA‐compatible.

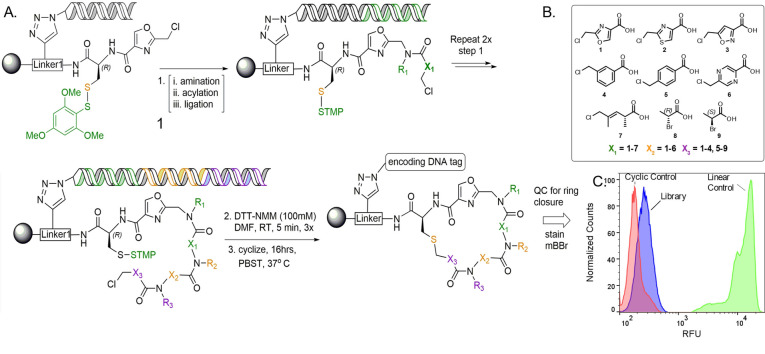

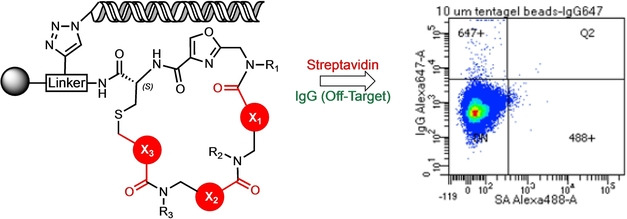

Figure 2.

General library design. A) The library was synthesized by solid‐phase split‐and‐pool synthesis on 10 μm resin possessing a linker (Linker‐1) modified with HDNA, Cys(STmp), and an oxazole (Compound 1). The linear precursors were formed after 3 rounds of amination/acylation/enzymatic ligation using the backbone units shown (B). The STmp group was then removed to allow thioether formation. C) After macrocyclization, aliquots (about 10 000 beads) were stained with a thiol‐reactive fluorescent dye (mBBr) to confirm that the vast majority of the library completed cyclization. Control compounds are shown in Figure S5.

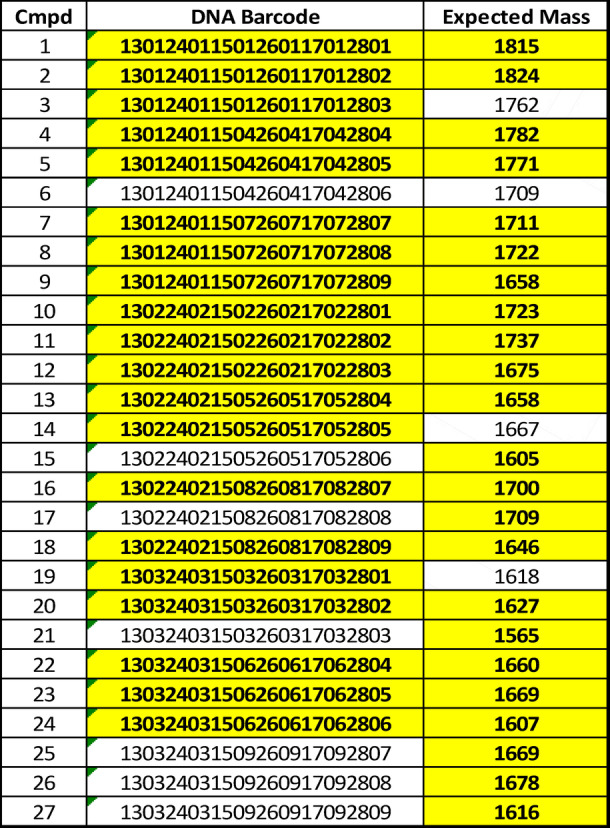

Table 1.

A set of 27 DNA‐encoded PICCO macrocycles was synthesized in individual wells of a filter plate, then assayed by DNA sequencing and MALDI. Verified sequences and masses are highlighted in yellow.

Library Design and Synthesis

With these preliminary quality control experiments completed satisfactorily, a one‐bead, one‐compound (OBOC) DEL of approximately 580 000 compounds (Figure 2A) was constructed on 10 μm TentaGel resin displaying Linker‐1 (Figure S1), modified with HDNA, Cys(STmp), and 2‐(chloromethyl)oxazole‐4‐carboxylic acid (Compound 1). This was followed by three cycles of split and pool amination and acylation. After each round of amination/acylation, an encoding DNA was ligated onto the encoding chains, the beads pooled, then redistributed into a new filter plate. Finally, the cysteine was deprotected.

Because 6–8 different carboxylic acid building blocks were employed at the three “main chain” diversity positions, the library has exceptional macrocyclic scaffold diversity. Moreover, a “null” row was included at the second PICCO position (X2 in Figure 2), where no carboxylic acid was added to the bead. This results in the omission of the X2 and N−R3 elements shown in Figure 2A (for these beads only) and generates a library that includes both “2.5‐mer” and “3.5‐mer” macrocyclic compounds (Figure S4). Twelve different amines were employed at each diversity position.

On‐Resin Macrocyclization Assay

To assess the level of macrocyclization in the library, a FACS‐based macrocyclization assay recently developed in our laboratory was employed. [20] Briefly, several hours after cysteine deprotection, allowing sufficient time for thioether formation, a thiol‐reactive fluorescent dye, Monobromobimane (mBBr), is added to the beads. Any linear starting material remaining at this time will be stained by mBBr, but the thioether product will not. The fluorescence intensity on each bead is then measured by FACS, reflecting the amount of uncyclized material on each bead. When this assay was carried out on an aliquot of beads from the library synthesis, the results shown in Figure 2C were obtained. The library beads (purple peak) displayed only a low level of fluorescence, barely greater than that observed when beads displaying a methionine (thioether) unit were stained with mBBr (red peak, “cyclic control”). In contrast, control beads displaying cysteine (free thiol) displayed a dramatically higher level of fluorescence after staining with mBBr (green peak). These data indicate that the vast majority of library compounds efficiently formed thioether macrocycles.

FACS‐Based Screening

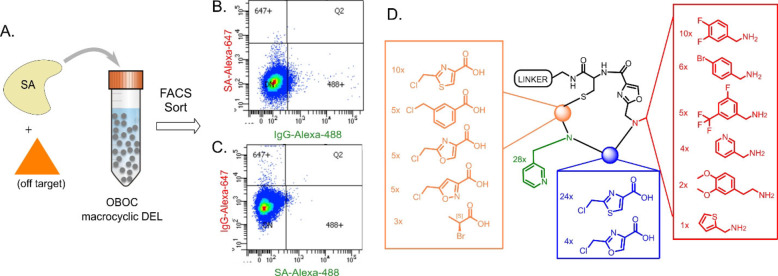

The DEL shown in Figure 2 was used in a two‐color, FACS‐based screen to identify macrocycles that selectively bind to a target protein, SA, over an unrelated off‐target, human IgG (Figure 3). Ten copies of the library (almost six million beads) were incubated with differentially labeled SA (the target) and human IgG (the off‐target) as well as a large excess of unlabeled, diverse competitor proteins, then FACS was used to isolate highly fluorescent beads. To minimize the possibility that the fluorophores would affect the outcome, the screen was done in duplicate, but with the labels swapped. Specifically, one screen employed AlexaFluor 647 (A647)‐conjugated SA (SA‐A647) and AlexaFluor 488 (A488)‐labelled human IgG, while the second screen used A488‐conjugated SA and A647‐labelled human IgG.

Figure 3.

Summary of screening experiments. A) Library beads were incubated with fluorescently‐labeled streptavidin (SA) and an orthogonally labelled off‐target, then sorted by FACS. B), C) FACS plots showing data from the SA‐A647/IgG‐A488 (B) and IgG‐A647/SA‐A488 (C) replicate screens. Beads that shifted into the 647+ or 488+ gates were collected, and the encoding DNAs deep sequenced for structure determination. D) “Bottom‐up” analysis of 28 “2.5‐mer” SA hits, indicating the frequency of each chemical unit at each position. This illustrates a conserved pyridine side‐chain (green) that is almost exclusively adjacent to a thiazole backbone unit (blue).

The DNA barcodes on the beads displaying a high level of fluorescence in the channel represented by the SA dye were then amplified by PCR and deep sequenced. Because bead screening has a significant false positive rate, we focused on compounds that appeared in the hit pool on at least three different beads (the encoding tag includes a bead‐specific barcode). [14] We have found that these so‐called “redundant hits” are usually bona fide target protein ligands while “singletons” are usually false positives. [21] The redundant hits that appeared in both of the screening experiments were then decoded to generate a list of putative ligands for SA (Table S1). Of these 31 hits, the vast majority (28/31) were the smaller, “2.5‐mer” macrocycles, where the X2 and N−R3 elements (Figure 2A) are absent, indicating that the binding site on SA prefers more compact ligands. This is not surprising since SA is a biotin‐binding protein. All 28 of these macrocycles include a pyridine side chain at the second amine position, which is almost always adjacent to a thiazole (24 out of 28 compounds), suggesting that this grouping is important for binding (Figure 3D). Indeed, the other four hits contained a closely related oxazole at this position (Figure 3D). Almost half of the screening hits contain the difluorobenzylamine‐derived side chain at position N−R1 and there is always an aromatic ring at this position. Finally, at position X3, 25/28 hits have a 1,3‐substituted aromatic ring, suggesting that the influence of this spacing and regiochemistry on the conformation of the macrocycles is important for high affinity binding.

Validation of Screening Hits

To determine if the redundant screening hits are indeed bona fide SA ligands, 22 of them were re‐synthesized by solid‐phase parallel synthesis on both 10 μm and 160 μm beads without DNA tags. The 160 μm beads were treated with benzyl bromide after allowing enough time for macrocyclization to go to completion. This modifies any free thiols, while also improving MS ionization, thus making it easier to spot unreacted starting material in the mass spectrometer. The compounds were then released from the beads by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and analyzed by MALDI mass spectrometry. The MALDI data (Figure S12) indicate the presence of the correct macrocyclic compound for each resynthesized hit, with only two samples showing the presence of linear compound (in addition to the macrocycle) (Table S2). Notably, this treatment also modified the pyridine nitrogen in each of the compounds synthesized. These data confirm that the chemistry proceeded as designed and indicate further that these compounds cyclize readily.

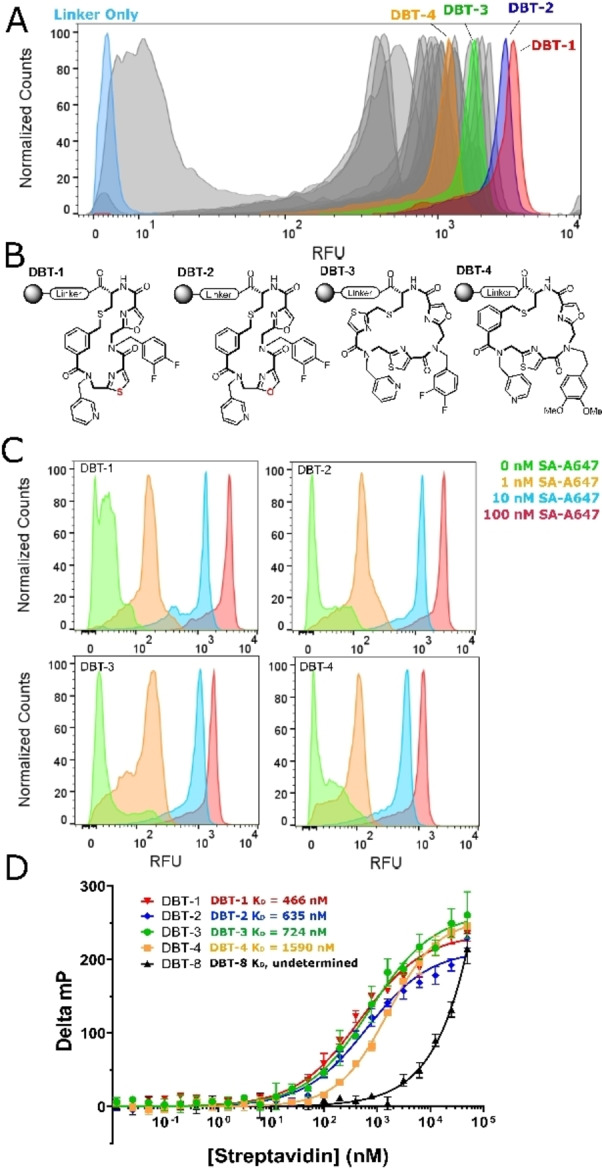

The 10 μm beads displaying resynthesized hits were individually incubated with 100 nM SA‐A647 and analyzed for retention of the protein using a flow cytometer. As a negative control, beads displaying only the linker were also tested. The results are shown in Figure 4A. Nearly all of the beads displaying the various screening hits evinced a much higher brightness than the linker only control. It has been shown that the amount of fluorescently labeled protein captured by a compound displayed on 10 μm TentaGel beads at a given concentration of the target correlates directly with the K D of the ligand‐protein complex. [13] Thus, the FACS analysis suggests that two of the macrocyclic compounds, DBT‐1 and DBT‐2 (Figure 4B), which are nearly identical, differing by only one atom (oxazole vs. thiazole rings at position X1), have the highest affinity for SA, while the remaining compounds bind with slightly lower affinities. These data were used to rank‐order the putative hits and to select compounds for further analysis (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Validation of screening hits. A) FACS histogram showing the relative fluorescence of beads displaying resynthesized hits after incubation with 100 nM SA‐A647. Highlighted samples were analyzed further. B) Structures of the selected hits. C) Titration of beads displaying DBT compounds with the indicated concentration of SA‐A647, followed by FACS analysis. FACS histograms are shown. D) Fluorescence polarization data for the selected DBT compounds.

An on‐resin titration experiment was done. DBT‐1 and DBT‐2, as well as two hits that indicated lower binding affinities, DBT‐3 and DBT‐4, were titrated with labeled SA. Robust, above‐background binding of the labeled SA is observed even at 1 nM protein concentration for each of ligands (Figure 4C).

SA is a native tetramer, so avidity effects likely contribute to the high affinity binding to bead‐displayed ligands. To evaluate the intrinsic affinities in solution, fluorescein conjugates of each hit were synthesized, released from the resin and purified by HPLC (Figure S6). As a negative control, one of the compounds present in the library that did not show up as a hit (DBT‐8, Figure S6) was also included. Titration of these compounds with unlabeled SA was monitored by an increase in fluorescence polarization (FP). Each of the resynthesized hits bound to SA with affinities in the high‐nanomolar to low‐micromolar range (Figures 4D). Furthermore, the compounds demonstrated selectivity for SA, as no binding was detected when they were exposed to unrelated proteins (Figure S7). Of note, the relative binding affinities determined from these data correlate nicely with apparent affinities suggested by the on‐resin FACS data. Thus, the bead‐based FACS method for rank‐ordering the putative hits provides a relatively accurate representation of true binding affinities. The ease of hit validation using this methodology is notable. Dozens of compounds can be re‐synthesized on a small scale, using exactly the same chemistry employed to create the library, and tested for on‐resin binding by FACS in just a few days at little expense.

Nature of the Macrocycle–SA Interaction

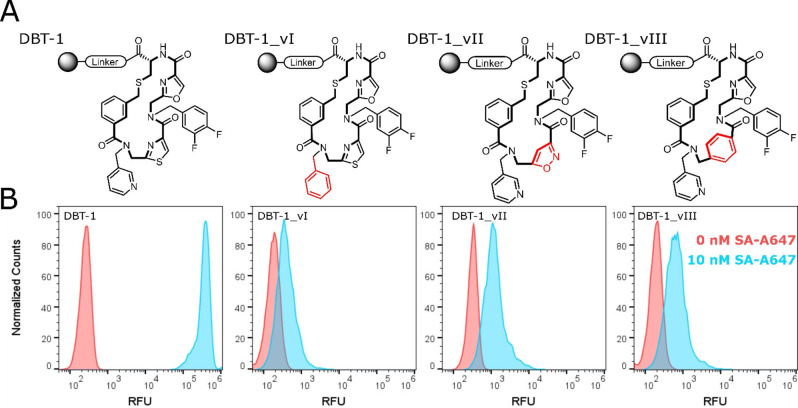

As discussed above, all the hits identified in this screen include an oxazole or thiazole followed by an aminomethyl pyridine (Figure 3), strongly suggesting that these residues are pivotal for SA binding. To test this, a series of DBT‐1 analogues were synthesized on 10 μm resin and exposed to 100 nM SA‐A647. As shown in Figure 5, substitution of the pyridine ring with a phenyl group essentially abolished binding of the macrocycle to SA. Substitution of the thiazole ring in the main chain with an isoxazole unit also had catastrophic consequences for binding. This was also the case when a 1,4‐substituted phenyl ring replaced the thiazole. These data show clearly that the highly conserved elements in the hit pool are critical to high affinity SA binding. More generally, this experiment demonstrates the ease with which preliminary structure activity relationships using parallel solid‐phase synthesis of derivatives followed by FACS‐based analysis of protein binding.

Figure 5.

Structure–activity relationship. A) Structures of DBT‐1 and three analogs tested. B) FACS histograms showing the level of fluorescent SA binding to the corresponding bead‐displayed analogues. The structural alterations relative to DBT‐1 are highlighted in red.

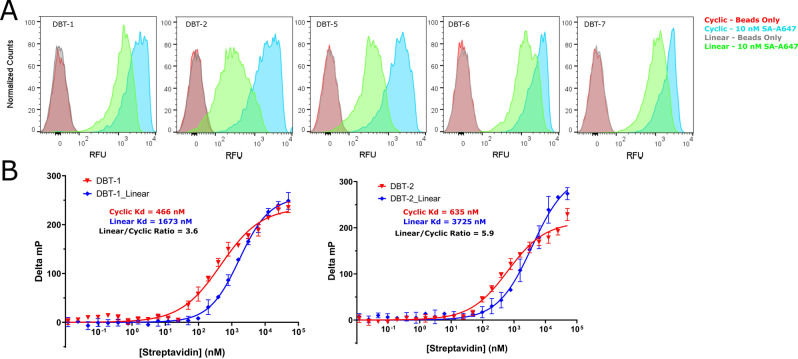

It is often the case that the linear analogues of macrocyclic protein ligands bind more weakly to the target due to increased conformational flexibility. To test this, beads displaying DBT‐1 or DBT‐2 or their linear analogues (see Figure S8) were incubated with 10 nM SA‐A647 and assayed for binding. Both macrocycles exhibited stronger binding to SA than their linear analogs (Figure 6A), although the differences were modest. To address the same question in solution, fluorescein‐tagged macrocyclic and linear molecules (Figure S5) were titrated with SA and binding was again followed by an increase in FP (Figure 6B). In each case, the macrocyclic compounds showed stronger binding affinities than their linear counterparts, but again the difference was relatively modest (4‐ to 6‐fold).

Figure 6.

Comparison of macrocyclic hits with corresponding linear analogues. A) A set of macrocyclic and linear compounds was resynthesized on‐resin, incubated with 10 nM SA‐A647, then assayed by FACS for SA binding. Higher RFU suggests a stronger binding affinity for the macrocyclic compounds. B) Fluorescence polarization data indicating the binding affinities of two purified macrocyclic compounds and their linear analogues.

Lastly, when DBT‐1‐displaying beads were incubated with SA‐A647 in the presence of excess biotin, binding was abolished, arguing that the macrocycle recognizes the biotin‐binding pocket of SA (Figure S9).

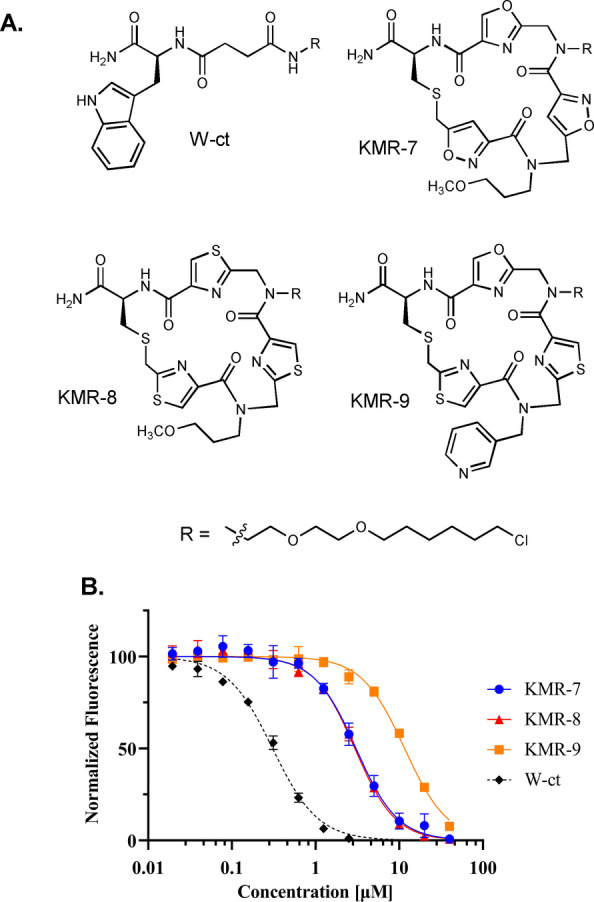

PICCO Macrocycles Are Cell Permeable

Having established the ability to synthesize and successfully screen DELs of PICCO macrocycles, we evaluated the cell permeability of a representative group of structures containing oxazole and thiazole units in the cycle (Figure 7A and S13) using the chloroalkane penetration assay (CAPA). [22] This involves incubation of the chloroalkane‐tagged molecule of interest with mammalian cells that express the HaloTag protein (HTP). If the molecule is cell permeable, then covalent reaction with intracellular HTP blocks labeling of this protein when the cells are subsequently treated with a chloroalkane‐linked fluorescent dye. The results of several such experiments done at different macrocycle concentrations, are shown in Figure 7B. For comparison, the permeability of a Lipinski‐compliant tryptophan‐containing small molecule (W‐ct) was also measured. The data show that all of the macrocycles are quite cell permeable, with CP50 values in the low μM range. Quantitatively, KMR‐7 and KMR‐8 were about 10‐fold less permeable than W‐ct, while KMR‐9 was about 37 times less permeable, perhaps reflecting the presence of the polar pyridine side chain. Given the molecular masses of KMR‐7, ‐8, and ‐9 (754, 802 and 805 Daltons, respectively), this an encouraging result and suggests that DELs of PICCOs can serve as an interesting source of probe molecules targeting intracellular proteins. A more comprehensive analysis of PICCO cell permeability will be presented in a separate study (Tokmina‐Roszyk, et al., in preparation).

Figure 7.

Cell permeability of select PICCO macrocycles. A) Structures of the molecules analyzed. B) Relative level of fluorescence of cells treated with the compounds indicated followed by chloroalkane‐tagged fluor (see Supporting Information for details).

Conclusion

In summary, efficient methods for the synthesis and screening of high quality, OBOC DELs of non‐peptidic macrocycles has been established. Initial cell permeability data suggests that, as expected, these molecules are quite cell permeable. In addition, a post‐screening workflow has been established that rapidly provides useful structure–activity relationship data. We anticipate that the DEL shown in Figure 2 and related libraries will serve as a useful source of probe molecules for both intracellular and extracellular proteins. We are currently deploying this DEL and related libraries against a variety of challenging targets. These efforts will be reported in due course.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by an SBIR grant for the National Institutes of Health (GM130164) to E.K. and a Transformational RO1 grant (GM 133041) to T.K. We thank Dr. Ofelia Utset for administrative oversight of all aspects of the project. All bead sorting and flow cytometry experiments were performed at the Scripps Florida Flow Cytometry Core. Deep sequencing was performed at Scripps Research Florida Genomics Core. We thank the staff of these cores for their technical advice and assistance.

E. Koesema, A. Roy, N. G. Paciaroni, C. Coito, M. Tokmina-Roszyk, T. Kodadek, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202116999; Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202116999.

A previous version of this manuscript has been deposited on a preprint server (https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.13490151.v1).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Lipinski C. A., J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997, 23, 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Villar E. A., Beglov D., Chennamadhavuni S., J. A. Porco, Jr. , Kozakov D., Vajda S., Whitty A., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 723–731; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Whitty A., Viarengo L. A., Zhong M., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 7729–7735; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Giordanetto F., Kihlberg J., J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 278–295; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Heinis C., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 696–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Smith G. P., Petrenko V. A., Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 391–410; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Heinis C., Winter G., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015, 26, 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Hanes J., Schaffitzel C., Knapplik A., Plückthun A., Nat. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 1287–1292; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Ohuchi M., Murakami H., Suga H., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007, 11, 537–542; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Wilson D. S., Keefe A. D., Szostak J. W., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3750–3755; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Keefe A. D., Wilson D. S., Seelig B., Szostak J. W., Protein Expression Purif. 2001, 23, 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Ahlbach C. L., Lexa K. W., Bockus A. T., Chen V., Crews P., Jacobson M. P., Lokey R. S., Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 2121–2130; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Bockus A. T., McEwan C. M., Lokey R. S., Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 821–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Vinogradov A. A., Yin Y., Suga H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4167–4181; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Rezai T., Bock J. E., Zhou M. V., Kalyanaraman C., Lokey R. S., Jacobson M. P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14073–14080; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Rezai T., Yu B., Millhauser G. L., Jacobson M. P., Lokey R. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2510–2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Clark M. A., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010, 14, 396–403; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Neri D., Lerner R. A., Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 479–502; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Kleiner R. E., Dumelin C. E., Liu D. R., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5707–5717; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Gartner Z. J., Kanan M. W., Liu D. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 10304–10306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kleiner R. E., Dumelin C. E., Tiu G. C., Sakurai K., Liu D. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11779–11791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Usanov D. L., Chan A. I., Maianti J. P., Liu D. R., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 704–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stress C. J., Sauter B., Schneider L. A., Sharpe T., Gillingham D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 9570–9574; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 9671–9675. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lam K. S., Salmon S. E., Hersh E. M., Hruby V. J., Kazmierski W. M., Knapp R. J., Nature 1991, 354, 82–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. MacConnell A. B., McEnaney P. J., Cavett V. J., Paegel B. M., ACS Comb. Sci. 2015, 17, 518–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erharuyi O., Simanski S., McEnaney P. J., Kodadek T., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2773–2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mendes K., Malone M. L., Ndungu J. M., Suponitsky-Kroyter I., Cavett V. J., McEnaney P. J., MacConnell A. B., Doran T. M., Ronacher K., Stanley K., Utset O., Walzl G., Paegel B. M., Kodadek T., ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 19, 234–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kodadek T., McEnaney P. J., Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6038–6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Kawakami T., Ohta A., Ohuchi M., Ashigai H., Murakami H., Suga H., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 888–890; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Fadzen C. M., Wolfe J. M., Cho C.-F., Chiocca E. A., Lawler S. E., Pentelute B. L., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15628–15631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malone M. L., Paegel B. M., ACS Comb. Sci. 2016, 18, 182–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clark M. A., Acharya R. A., Arico-Muendel C. C., Belyanskaya S. L., Benjamin D. R., Carlson N. R., Centrella P. A., Chiu C. H., Creaser S. P., Cuozzo J. W., Davie C. P., Ding Y., Franklin G. J., Franzen K. D., Gefter M. L., Hale S. P., Hansen N. J., Israel D. I., Jiang J., Kavarana M. J., Kelley M. S., Kollmann C. S., Li F., Lind K., Mataruse S., Medeiros P. F., Messer J. A., Myers P., O'Keefe H., Oliff M. C., Rise C. E., Satz A. L., Skinner S. R., Svendsen J. L., Tang L., van Vloten K., Wagner R. W., Yao G., Zhao B., Morgan B. A., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kolb H. C., Sharpless K. B., Drug Discovery Today 2003, 8, 1128–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roy A., Koesema E., Kodadek T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11983–11990; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 12090–12097. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Doran T. M., Gao Y., Mendes K., Dean S., Simanski S., Kodadek T., ACS Comb. Sci. 2014, 16, 259–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peraro L., Zou Z., Makwana K. M., Cummings A. E., Ball H. L., Yu H., Lin Y. S., Levine B., Kritzer J. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7792–7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.