Summary

The incidence of obesity, a recognized risk factor for various metabolic and chronic diseases, including numerous types of cancers, has risen dramatically over the recent decades worldwide. To date, convincing research in this area has painted a complex picture about the adverse impact of high body adiposity on breast cancer onset and progression. However, an emerging but overlooked issue of clinical significance is the limited efficacy of the conventional endocrine therapies with selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or degraders (SERDs) and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) in patients affected by breast cancer and obesity. The mechanisms behind the interplay between obesity and endocrine therapy resistance are likely to be multifactorial. Therefore, what have we actually learned during these years and which are the main challenges in the field? In this review, we will critically discuss the epidemiological evidence linking obesity to endocrine therapeutic responses and we will outline the molecular players involved in this harmful connection. Given the escalating global epidemic of obesity, advances in understanding this critical node will offer new precision medicine‐based therapeutic interventions and more appropriate dosing schedule for treating patients affected by obesity and with breast tumors resistant to endocrine therapies.

Keywords: breast cancer, endocrine therapy resistance, obesity

1. INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer represents the most commonly occurring malignancy and the first leading cause of cancer‐associated deaths in women throughout the world, showing morbidity and mortality rates of ~25% and ~15%, respectively. On the basis of GLOBOCAN 2020 data, an estimated 2,3 million new cases of breast neoplasia have been diagnosed in women in 2020, with breast cancer incidence continuing to rise up to approximately 3.19 million in 2040. 1

Breast cancer embraces a heterogeneous collection of pathological entities with diverse morphologies, molecular features, sensitivity to therapy, likelihoods of relapse and overall survival. Traditional histopathological classification aims to categorize tumors into subgroups to guide clinical management decisions. Indeed, the expression of established prognostic and predictive biomarkers, including hormone receptors, such as estrogen (ER) α and progesterone (PR) receptors, human epidermal growth factor 2 receptor (HER2) oncoprotein and the Ki‐67 proliferative index, is currently the basis for targeted treatments. In particular, ERα‐positive breast malignancy that overlaps with luminal molecular subtypes 2 accounts for ~70%–80% of all cancer cases. In these tumors, endocrine‐based treatments with selective ER modulators (SERMs) or degraders (SERDs) and aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are of major therapeutic value both in the adjuvant and recurrent settings. The drugs of choice include (i) the prototype of SERMs tamoxifen, a partial nonsteroidal estrogen agonist, that acts as a type II competitive inhibitor of estradiol at its receptor; (ii) the SERD fulvestrant, a competitive antagonist whose interaction with ER induces its proteasome‐dependent degradation; (iii) the nonsteroidal (letrozole, anastrozole) and steroidal (exemestane) AIs able to significantly lower serum estradiol concentration in patients after menopause. However, despite the improvements in the outcomes of patients affected by breast cancer following their implementation into daily oncology practice, the development of “de novo” or acquired resistance to endocrine therapy has become a major limitation. 3 To date, several hallmarks of hormonal resistance have been proposed. 4 This may include ERα loss or mutations, activation of growth factor‐mediated signaling pathways, alterations of key cell cycle checkpoints, promotion of epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), and cancer stem cell activity. 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 More recently, it was proven that a reduced response to these therapeutic treatments may rely not only on tumor‐cell intrinsic factors, but it is also dependent on the surrounding microenvironment and on the host characteristics. Indeed, studies have suggested that obesity, in addition to promoting breast cancer development and progression, represents a heavyweight player driving breast cancer endocrine resistance. 14 , 15 , 16

In this review, we will highlight the complex and incompletely elucidated link existing between obesity and resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer. First, we will summarize the evidence derived from population studies that outlines the implications of excessive adiposity on therapeutic management of patients. Then, we will focus on the role played by adipocytes in endocrine resistance, discussing both “in vitro” and “in vivo” research. Finally, we will address the molecular mechanisms by which obesity‐associated changes may limit the success of tamoxifen, fulvestrant and AIs, underlining the main actors involved in this alarming connection.

2. OBESITY‐DEFINITION

Obesity is a multifactorial metabolic disorder characterized by an imbalance in energy homeostasis, leading to abnormal accumulation in body weight. It can be clinically measured in multiple ways, such as body mass index (BMI [kg/m2]: body weight relative to height), or fat distribution (central vs. peripheral). According to the standard World Health Organization (WHO) and National Institute of Health (NIH) definitions, overweight refers to a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2, and obesity to a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 (30.0–34.9, grade I; 35.0–39.9, grade II; and ≥40, grade III). Based on BMI criteria, the latest WHO fact sheets reported that in 2016 more than 1.9 billion world's adult population were affected by overweight (~39%) and of this over 650 million adults were affected by obesity (~13%). Specifically, the prevalence of obesity has tripled worldwide over the past four decade and these upsetting rates are expected to increase in the future.

Rather than overall obesity evaluated by BMI, either waist‐to‐hip ratio (WHR) greater than 0.80 in women and 0.95 in men or waist circumference (WC) greater than 88 cm in women and 102 cm in men have been generally proposed to assess central adiposity. 17 WHO guidelines state that these alternative measures are better anthropometric parameters than BMI to predict the risk of obesity‐related diseases. 18 , 19 This is largely based on the rationale that body composition reflects more correctly metabolically active adipose depots, with visceral fat tissue contributing significantly to metabolic and hormonal abnormalities (i.e., reduced glucose tolerance, decreased insulin sensitivity, and altered lipid profiles). 20 In contrast, BMI does not seem to measure accurately adipose versus lean mass and does not consider fat distribution; for instance, it could overestimate fat mass in physically active people and underestimate it in older patients with sarcopenia. 21 Nonetheless, BMI remains the most practical and widely chosen indicator for diagnosing obesity and for evaluating the occurrence of the negative health consequences associated with obesity among individuals.

3. OBESITY AND BREAST CANCER

The worldwide escalating prevalence of obesity poses a serious threat to health care practitioners and global health system. Obesity represents not only a major recognized risk factor for metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, but it also accounts for nearly one‐third of all new cancer diagnoses and for 15%–20% of total cancer‐related deaths. 22 , 23 Indeed, there is expanding evidence showing a role for obesity as a contributor to several types of malignancies, including endometrial, prostate, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast carcinomas. 13 Numerous clinical studies demonstrate that excessive adiposity may worsen the incidence, the prognosis and the mortality rates of breast cancer, particularly in relation to menopausal status and disease subtypes. 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 An inverse association between BMI and risk of premenopausal breast cancers was demonstrated 24 , 25 , 26 ; while obesity was correlated with high probability to develop breast cancer among women after menopause, with an increased relative risk for ERα‐ and PR‐positive diseases. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 Conversely, findings from the multinational European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort, involving 242,918 women after menopause, highlighted a protective role of healthy lifestyles (i.e., healthy diet, moderate/vigorous intensity physical activity, and low BMI) on breast cancer incidence. 35 It has been estimated that by limiting weight gain during adult life, the annual risk could be decreased by 50%, beneath 13,000 cases in the European Union. 36 Obesity was also positively correlated to breast cancer recurrence and mortality in both premenopausal and postmenopausal settings. 37 , 38 Women with obesity were more likely to exhibit larger tumor sizes, lymph node involvement, higher propensity to distant metastasis, lower distant disease‐free interval, and overall survival. 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 At diagnosis, patients with obesity and diabetes were more likely to be older, postmenopausal and to have larger tumors and poor outcomes compared to patients without obesity or diabetes, suggesting that metabolic health may influence breast cancer prognosis. 47 Furthermore, overweight and obesity have been associated with increased risk of developing contralateral breast cancer or a second primary malignancy at other sites in women previously diagnosed with breast cancer. 48 , 49

In the adjuvant setting, data are emerging on the lower benefits of anti‐tumor therapies in women with obesity compared to women with a healthy weight, thus predicting significant challenges for care and disease management of patients with breast cancer. 14

4. OBESITY AND ENDOCRINE RESPONSE IN BREAST CANCER: EPIDEMIOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Obesity is associated with a reduced effectiveness of chemotherapeutic agents, in part related to dose‐limiting toxicity and undertreatment in patients with obesity. 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 Increased risk of complications associated with all treatment modalities (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy) has also been described. 50 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 On the other hand, the optimal use of endocrine treatments in women with obesity is still a topic of intensive research, since in the literature data relating these therapeutic regimens, BMI, and outcomes are not conclusive. Details of these studies are included in Table 1. 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81

TABLE 1.

Studies showing correlation between BMI and response to endocrine treatment in breast cancer

| Study/institution | Study type | Population | Comparison | Setting | Numbers of patients | Proportion ER+/PR+ | Intervention | Follow‐up time or lenght of the study | Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Protocol 14 | Randomized, placebo‐controlled trial | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

UW: BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 3,385 | 100% | Tam | Median follow‐up: 166 mo. | Reduced BC recurrence, controlateral BC events, overall mortality and mortality after BC events, regardless of BMI | 62 |

| Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) | Randomized, placebo‐controlled trial | Postmenopausal |

BMI < 25 kg/m2 versus BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 7,705 | 75% | Ral | Median follow‐up: 8 y. | Reduced risk of invasive BC, regardless of BMI | 63 |

| Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational (TEAM) Trial | Randomized, international phase III trial | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25–30 kg/m2 OB: BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 4,741 | 100% | Exe Tam | Median follow‐up: 5.1 y | Reduced RFS and OS in OB patients treated with Tam compared to OB patients treated with Exe at 2.75 y, while no difference was noticeable at 5.1 y. | 64 |

| Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Trial | Randomized, double‐blind trial | Postmenopausal | BMI: <23, 23–25, 25–28, 28–30, 30–35, >35 kg/m2 | Adjuvant | 5,172 | 100% | Tam Ana | Median follow‐up: 100 mo. | Reduced recurrence rates in the Ana group compared to Tam group at all BMI levels, however the benefit of Ana compared to Tam was lower in patients with BMI > 30 kg/m2 | 65 |

| Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group Database | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

BMI < 25 kg/m2 BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 18,967 | 50% | Tam AIs | Median follow‐up: 30 y | Increased risk of death in patients with high BMI versus patients with low BMI. | 66 |

| Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG) 12 Trial | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 1,684 | 100% | Ana Tam Gos ZA | Median follow‐up: 62.6 mo. | Reduced DFS and OS in OW compared to NW patients treated with Ana. Reduced DFS and OS in OW patients treated with Ana versus OW patients treated with Tam. No difference in DFS and OS in NW and OW patients treated with ZA. | 67 |

| Breast International Group (BIG) 1–98 Trial | Randomized double‐blind phase III trial | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI < 25 kg/m2 OB: BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 4,760 | 71% | Tam Let | Median follow‐up: 8.7 y | No differences in OS among OB and NW patients in Tam and Let groups. | 68 |

| Dept of Medical Oncology, Ankara Education and Research Numune Hospital (TUR) | Retrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW/OB: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 501 | 100% | Ana Let | Median follow‐up: 25.1 mo. | No difference in OS and DFS among OW/OB and NW patients treated with AIs. | 69 |

| JFMC 34–0601 Trial | Phase II trial | Postmenopausal |

Low BMI: BMI < 22 kg/m2 Intermediate BMI: BMI 22–25 kg/m2 High BMI: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

Neoadjuvant | 109 | 100% | Exe | N/A | Reduced ORR in low BMI compared to intermediate and high BMI patients treated with Exe. | 70 |

| German BRENDA Study | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

Non‐OB: BMI < 30 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 3,896 | 84% | AIs Tam | Length of the study: 13 y | Reduced RFS in OB patients treated with AIs compared to Tam. A nonsignificant statistical trend towards an increased RFS for AIs compared to Tam in NW and intermediate patients. | 71 |

| Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG) 06 Trial | Restrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 634 | 81% | Ana | Median follow‐up: 73.2 mo. | Nonsignificant reduced DFS, DRFS and OS in OW/OB versus NW patients treated with Ana. No difference in DFS, DRFS and OS between OW/OB patients treated with additional 3y of Ana versus OW/OB patients with no further treatment. Reduced DFS, DRFS and OS in NW patients treated with extended Ana versus NW patients with no further treatment. | 72 |

| Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG) 6 Trial | Retrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 1,509 | 80% | Tam AG | Median follow‐up: 60 mo. | No difference in DFS and OS between OW/OB and NW patients treated with single Tam. Reduced DFS and OS in OW/OB patients treated with Tam + AG compared to NW patients. | 73 |

| Fondazione IRCCS, Italy | Prospective Study | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 75 | 100% | Fulv | Length of the study: 6 y | Reduced CBR OW and OB patients compared to NW patients treated with Fulv. | 74 |

| Dept of Medical Oncology, Ankara Hospital (TUR) | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW/OB: BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 826 | 100% | Tam | Median follow‐up: 37.5 mo. | Reduced OS in OW/OB patients compared to NW patients treated with Tam. | 75 |

| Five Italian cancer centers | Retrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

BMI < 25 kg/m2 BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 161 | 87% | Fulv | Follow‐up: N/A | Longer PFS in AI‐resistant patients with lower BMI. | 76 |

| Dept of Breast Medical Oncology, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston (USA) | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI < 25 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25–30 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 6,342 | 77% | Tam AIs | Median follow‐up: 5.4 y | Reduced RFS and OS in OW and OB patients compared to NW treated with Tam, but not in those treated with AIs or both therapies. | 77 |

| BC‐Blood Study | Prospective study | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 WC ≥ 80 cm Volume ≥850 ml versus BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2 WC ≤ 80 cm Breast Volume ≤850 ml |

Adjuvant | 1,640 | 88% | Tam AIs | Median follow‐up: 3.05 y | Reduced OS and BCFI in Tam‐ and AI‐treated patients with BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, WC ≥ 80 cm and a breast volume ≥850 ml compared with patients with lower BMI, WC and breast volume. | 78 |

| Dept of Oncology, Eskiestuma and Uppsala (SWE) | Retrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

Non‐OB: BMI < 30 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 320 | 100% | Let | Median follow‐up: 49 mo. | No difference in RFS between OB and NW patients treated with Let. | 79 |

| Dept of Oncology, Eskiestuma and Uppsala (SWE) | Retrospective Study | Postmenopausal |

NW: BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 173 | 100% | AIs Fulv | Median follow‐up: 38 mo. | No difference in TTP, CBR and ORR among NW, OW and OB patients treated with Fulv only or both AIs and Fulv. | 80 |

| Oncology and Breast Unit of the “Sen. Antonio Perrino” Hospital in Brindisi (Italy). | Retrospective Study | Premenopausal Postmenopausal |

Lean weight: BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2 OW: BMI = 25–30 kg/m2 OB: BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 |

Adjuvant | 520 | 69% | AIs Tam LHRH1 | Median follow‐up: 66 mo. | High rates of recurrences with BMI gain, particularly with BMI variation more than 5.71% | 81 |

Abbreviations: AG, aminoglutethimide; Ana, anastrazole; BC, breast cancer; BCFI, breast cancer‐free interval; BCS, breast cancer survival; CBR, clinical benefit rate; DFS, disease free survival; Exe, exemestane; Fulv, fulvestrant; GOS, goserelin; HR+, hormone receptor positive; Let, letrozole; LHRHa, luteinizing hormone‐releasing hormone analogue; Mo., months; NW, normal weight; OB, obese; ORR, object response rate; OS, overall survival; OW, overweight; Ral, raloxifene; RFS, recurrence free survival; TTP, time to disease progression; Tam, tamoxifen; UW, underweight; WC, waist circumference; Y, years; ZA, zoledronic acid.

A report by Ewertz et al. on nearly 19,000 patients with early‐stage breast cancer, enrolled in Denmark between 1977 and 2006 with up to 30 years of follow‐up, demonstrated that the effects of adjuvant treatment with endocrine therapy (tamoxifen or AIs) were poorer in women with obesity than in ones with lean weight, independently from tumor size, nodal status, and known prognostic factors, such as hormone receptor expression. 66 Wisse et al. analyzing 1,640 patients with primary breast cancer found that a preoperative BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 was associated with a worse prognosis in women treated with tamoxifen or AIs compared to patients with a healthy BMI. 78 BMI gain was significantly correlated to increased risk or recurrences, especially in patients with BMI variations more than 5.71% after endocrine treatments for early‐stage breast cancer. 81 In another study on a cohort of 6,342 patients, the analysis of the ER‐positive subgroup according to adjuvant endocrine therapy revealed that higher BMI was associated with shorter recurrence‐free and overall survival in patients treated with tamoxifen, but not in those receiving AIs alone or both therapies. 77 In premenopausal settings of women affected by overweight or obesity, poor overall survival was also found after tamoxifen treatment. 75 However, the NSABP B14 (National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project) clinical trial showed that tamoxifen decreased breast cancer recurrence and mortality in patients with lymph node‐negative and ER‐positive breast cancer, regardless of BMI 62 and the MORE (Multiple Outcome Raloxifene Evaluation) study evidenced a larger risk reduction within the arm of the SERM Raloxifene irrespective of the presence/absence of risk factors, including BMI. 63 A significant negative relationship was observed between body weight and clinical benefit derived from fulvestrant in women with advanced breast cancer after menopause. 74 A shorter progression‐free survival following fulvestrant treatment was also evidenced among patients with high BMI and resistant to AIs, 76 although no differences in fulvestrant treatment efficacy was found among women with normal weight, overweight, and obesity with metastatic breast cancers in a more recent study. 80

In the German BRENDA‐cohort of patients having normal or intermediate weight after menopause over 10 years of follow‐up, a nonsignificant statistical trend favoring a survival benefit for AIs (type not specified) compared to tamoxifen was observed; whereas women with obesity have a tendency to benefit from tamoxifen. 71 Accordingly, in the randomized double‐blind arimidex, tamoxifen alone or in combination (ATAC) trial, involving patients following menopause with ER‐positive disease randomly assigned to receive anastrozole alone, tamoxifen alone, or in combination with a 100‐month median follow‐up, it was found that Tamoxifen was equally effective across all BMI levels, while the relative benefit of anastrozole was significantly lower in women with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 compared to those women with a BMI lower than 28 kg/m2. 65 Pfeiler et al. confirmed an independent prognostic significance of BMI for patients with breast cancer under adjuvant endocrine therapy after menopause, showing a significant impact of BMI on the efficacy of AIs but none on that of single tamoxifen. 73 Correlation between higher BMI and worse outcomes with anastrozole, but not with tamoxifen, has also been reported in women before menopause affected by endocrine‐responsive breast cancers and treated with ovarian suppression by Goserelin in a retrospective analysis of the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG) 12 trial. 67 In particular, the cohort of women with excess weight who received anastrozole exhibited a 60% increase in the risk of disease recurrence and more than a doubling in the risk of death compared to survivors with normal weight. 67 In the group of high BMI, patients treated with anastrozole had a 49% increase in the risk of disease recurrence and a threefold increase in the risk of death compared with patients treated with tamoxifen, while survival rates were similar between patients with normal weight treated with anastrozole and tamoxifen and between premenopausal patients with overweight and normal weight under tamoxifen treatment. 67 Interestingly, BMI seems to function as a predictive parameter regarding extended endocrine treatment with an AI. 72 Indeed, re‐analysis of the ABCSG‐6a trial showed that the beneficial effects of extended anastrozole treatment were more evident in patients with normal weight than patients with increased BMI. 72 The pathophysiologic plausibility of these results might rely on the acknowledged relation of adipose tissue with higher aromatase activity and estrogen serum levels 82 as well as on the increased crosstalk existing between growth factor and ER signaling pathways that may further impact peripheral aromatization of androgens within the fatty tissue of patients with obesity. 83 Thus, an adjustment of the drug dosage may overcome obesity‐associated resistance to these drugs, but this assumption was confounded by two phase III clinical trials of anastrozole that demonstrated no additional clinical benefit from a 10 mg versus 1 mg dose per day in terms of objective response rate, time to objective progression of disease or time to treatment failure. 84 , 85 However, the conclusions arisen from these two studies cannot be considered definitive, since BMI classifications were not taken into account for predicting the dose of AIs required to maximize their clinical benefit.

In contrast with these findings, retrospective studies failed to find any dependency of anastrozole or letrozole efficacy to BMI, most probably because of small size and short follow‐up. 75 , 79 Interaction effects between BMI and treatment groups (tamoxifen or letrozole) were not statistically significant at a median of 8.7 years of follow‐up in the BIG 1–98 trial, although the AI was more effective than tamoxifen in reducing disease‐free survival events, overall deaths, breast cancer recurrences, and distant metastases across all BMI categories. 68 As opposite to the nonsteroidal AIs, in the neo‐adjuvant exemestane clinical trial, low BMI was found to be an independent negative predictor of clinical response based on the WHO criteria and a most favorable outcome was observed in the group with a high BMI. 86 In the TEAM (the tamoxifen exemestane adjuvant multinational) trial, at 2.75 years of follow‐up, there was a borderline increased risk of relapse in women with obesity receiving tamoxifen but not in users of exemestane, but at 5.1 years, BMI was not associated with risk of relapse in either arm. 64

From these observations, we can argue that the dissimilarities in the published findings may be due to differences in patient populations, disease characteristics, treatment, analysis methods, and BMI categories, and this complex scenario may certainly limit the possibility to pool results and to create generalized recommendations. Indeed, although on a long‐term basis, it seems that the efficacy of endocrine treatments, especially the nonsteroidal AIs, may depend on BMI of patients, further research needs to be warranted to optimize the selective hormonal therapy in women with breast cancer and obesity along with achieving and maintaining a healthy weight. Indeed, a number of clinical trials are currently ongoing to address this important issue (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical trials on obesity and endocrine therapy in breast cancer

| Trial identification | Intervention | Study type | Status | Eligible criteria, outcomes, and purpose | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01758146 |

Drug: Tam Drug: Let |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) |

Phase III, recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal patients (aged 45–80 y) with HR + BC with a tumor stage IB, IC, or II irrespective of nodal stage (<10 positive nodes). Primary Outcome: DFS. Event in the form of locoregional recurrence, distant metastasis, cancer in the contralateral breast, second primary cancer, or death from any cause. Secondary Outcome: (i) RFS, disease specific mortality; (ii) OS, till death due to disease/other cause over an average of 5 y. Purpose: To evaluate the impact of obesity on the efficacy of adjuvant endocrine therapy with AIs (specifically Ana) in postmenopausal patients with early‐stage BC in terms of (i) locoregional recurrence, (ii) distant metastases, (iii) DFS, and (iv) OS. |

N/A |

| NCT02095184 |

Drug: Ana Drug: Let |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) |

N/A, recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal patients (aged ≥ 18 y) with HR + BC or HER2− in primary tumor tissue and unresected operable BC stages I–III. Primary Outcome: Percent change in proliferative index (Ki67) after treatment with the standard dose Ana or Let in NW, OW and OB patients event through core biopsy. Secondary Outcome: (i) To evaluate differences in baseline GP88; (ii) to assess estradiol levels at baseline and after treatment (in primary HR + BC); (iii) to evaluate the association of AI‐induced Ki67 response; (iv) to evaluate differences in Oncotype Dx. Purpose: To evaluate if patients with higher body fat respond differently to AI treatment compared to those with lower body fat. |

N/A |

| NCT04389424 |

Drug: Tam Drug: Exe Drug: Ana |

Observational | N/A, recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Mexican patients with BC (aged 18–98 y) under endocrine therapy or recurrence of disease after endocrine therapy. Primary Outcome: (i) hidroxy vitamin D; (ii) plasma levels of hidroxy vitamin D; (iii) body composition; (iv) body composition (bioimpedance). Secondary Outcome : Recurrence of BC after endocrine therapy with Tam or AIs. Purpose: Evaluation of the relationship between drug therapy, food consumption, body composition and plasma micronutient levels with the expression of genes related to metabolism, aging and immunity in patients with BC. |

N/A |

| NCT01627067 |

Drug: Eve Drug: Exe Drug: Met |

Interventional | Phase II, terminated |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal OW (BMI: 25–29.9 kg/m2) or OB (BMI: ≥30 kg/m2) patients with HR + BC and clinical evidence of metastatic disease. Primary Outcome: (i) PFS; (ii) compare PFS Between the Number of OB and OW Participants Secondary Outcome: N/A Purpose: To evaluate if Exe and Eve combined with Met can help to control BC in patients who are OB or OW and postmenopausal with metastatic HR + BC. |

The combination of Met, Eve and Exe was safe and had moderate clinical benefit in OW/OB patients with metastatic HR+ and HER2− BC. Median PFS and OS were 6.3 mo. (95% CI: 3.8–11.3 mo.) and 28.8 mo. (95% CI: 17.5–59.7 mo.), respectively for OW/OB patients. Five patients had a partial response and 7 had stable disease for ≥24 weeks yielding a CBR of 54.5%. Compared with OW patients, OB patients had an improved PFS on univariable (p = 0.015) but not multivariable analysis (p = 0.215). 32% of patients experienced a grade 3 treatment‐related adverse event (TRAE). There were no grade 4 TRAEs and 7 patients experienced a grade 3 TRAE. |

| NCT03962647 |

Dietary Supplement: 2‐Week Ketogenic Diet Drug: Let |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) | Early Phase 1, recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) patients with HR+ or HER2− invasive BC with a tumor stage I, II, or III Primary Outcome: Patients who complete the dietary intervention Secondary Outcome: (i) To measure enhanced inhibition of cancer cell (Ki67); (ii) reduction in measures of insulin/P13K pathway activation (marks of insulin receptor/PI3K pathway activation in tumors); (iii) to measure changes in body composition (WC and BMI will be measured, weight and height will be checked); (iv) to measure changes in insulin resistance (fasting glucose/insulin to measure HOMA‐IR); (v) to measure effectiveness in inducing a ketogenic state (rate of ketones production) Purpose: Neoadjuvant study for determining the feasibility and tolerability of 2 weeks of a very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet plus Let for patients with early stage HR + BC. |

N/A |

| NCT02750826 |

Health Education Program Weight Loss Intervention |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) | Phase III, recruiting |

Eligible criteria: Patients with HR + BC as defined above must receive at least 5 y of adjuvant hormonal therapy in the form of Tam or AI, alone or in combination with ovarian suppression. Primary Outcome: IDFS Secondary Outcome: (i) OS; (ii) DDSF; (iii) Change in weight (defined as % change); (iv) Measures of physical activity (self‐report and objective); (v) Dietary intake (total calorie consumption); (vi) Occurrence of insulin resistance syndrome complications (diabetes, hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease); (vii) Changes in biomarker insulin, glucose, HOMA, leptin, adiponectin, IGF‐1, IGFBP3, IL‐6, CRP, TNF‐α associated with BC risk; (viii) Patient reported outcomes—physical functioning, fatigue, depression and anxiety, sleep disturbance, incidence of BC treatment related symptoms, body image. Purpose: To evaluate if weight loss in OW/OB patients may prevent BC recurrence. |

N/A |

| NCT04630210 |

Drug: Let Drug: Atez |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) | Early Phase 1, not yet recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal patients (aged 18–75 y) newly diagnosed nonmetastatic previously untreated and operable primary invasive BC. Primary Outcome: (i) Ki67 decrease at the time of surgery for OB and OW postmenopausal luminal B like treatment‐naïve early BC patients preoperatively having received a single dose of Atez in combination with Let daily (arm B) versus Let daily alone (arm A); (ii) sTIL increase at the time of surgery compared to the time of pre‐treatment biopsy for OB and OW postmenopausal luminal B like treatment‐naïve early BC patients preoperatively having received a single dose of Atez, either alone (arm C) or in combination with Let daily (arm B) versus Let daily alone (arm A). Secondary Outcome: N/A Purpose: To investigate Atez in HR + BC patients according to their adiposity (AteBrO) |

N/A |

| NCT00933309 |

Drug: Exe Drug: Ava |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) | Phase 1, completed |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal OW (BMI: 25–29.9 kg/m2) or OB (BMI: ≥30 kg/m2) patients with a HR + BC and clinical evidence of metastatic disease Primary Outcome: DLT Secondary outcome: N/A Purpose: The impact of obesity and obesity treatments on BC: a phase I trial of Exe with Met and Ros for postmenopausal OB patients with ER + metastatic breast cancer. |

N/A |

| NCT02538484 |

Drug: Let Dietary Supplement: Fish Oil |

Interventional (Clinical Trial) |

Early Phase 1, recruiting |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal OB (BMI: ≥30 kg/m2) patients with a HR + BC Primary Outcome: (i) Change in aromatase target gene levels; (ii) change in PGE2 serum levels Secondary outcome: N/A Purpose: Evaluating the impact of omega 3 fatty acid supplementation on aromatase in OB postmenopausal patients with HR + BC. |

N/A |

| NCT01896050 |

Drug: Ana Drug: Let Drug: Exe Drug: Tam |

Observational | Completed |

Eligible Criteria: Postmenopausal patients with a stage 0‐III HR + BC who are scheduled to receive endocrine therapy with Tam or AIs Primary Outcome: (i) Effect of change in BMI on change in grip strength with AI therapy; ii) Change in BMI between baseline and 12 months of endocrine therapy Secondary Outcome: (i) Effect of medication on change in grip strength; (ii) effect of either AI or Tam therapy on change in grip strength between baseline and 12 months; (iii) Association between baseline BMI and discontinuation of AI therapy within the first 12 mo.; (iv) Associations between baseline BMI and whether or not AI‐treated patients discontinued treatment by 12 months. Purpose: A prospective assessment of loss of grip strength by baseline BMI in BC patients receiving adjuvant third‐generation AIs and Tam. |

N/A |

Abbreviations: AIs, aromatase inhibitors; Ana, anastrazole; Atez, atezolizumab; Ava, avandamet; BC, breast cancer; BMI, body mass index; CBR, clinical benefit rate; DDFS, distant disease‐free survival; DFS, disease free survival; DLT, dose‐limiting toxicity; Exe, exemestane; Eve, everolimus: IDFS, invasive disease free survival; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR+, hormone receptor‐positive; Let, letrozole; Met, metformin; Mo., months; N/A, not applicable; −, negative; NW, normal weight; OB, obese; OS, overall survival; OW, overweight; PFS, progression free survival; PGE2, prostaglandin 2; RFS, recurrence free survival; Ros, rosiglitazone; sTIL, stromal tumor infiltrating lymphocytes; Tam, tamoxifen; WC, waist circumference; Y, years.

It is important to highlight that endocrine agents are also used in the breast cancer prevention setting. High quality evidence from observational studies and clinical trials has shown a reduced rate of breast cancer development in women at high‐risk by 40%–53% and a continued significant effect in the posttreatment follow‐up period. 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 However, utilization of preventive therapy remains poor mainly due to lack of physician and patient awareness, concerns about side effects (i.e., nausea, vomiting, hot flushes, musculoskeletal discomfort, fatigue and headaches for AIs, or vaginal bleeding, endometrial cancer and thromboembolism for tamoxifen) as well as other issues related to the need to improve our risk prediction models and develop surrogate biomarkers of response. For instance, evaluation of anthropometric parameters to identify women at high‐risk with greater accuracy and/or to predict sensitivity to breast cancer prevention are awaited with interest.

5. OBESITY AND ENDOCRINE RESPONSE IN BREAST CANCER: PROPOSED MECHANISMS

Several experimental studies have suggested a molecular link between obesity and endocrine resistance, particularly in relation to adipocytes. Indeed, different obesity‐related host factors can act locally or systemically as key contributors to the complex effects of high body adiposity on outcome and therapeutic response of patients. These host extrinsic factors interact with the intrinsic molecular characteristics of breast cancer cells and may encompass imbalance in adipokine pathophysiology, abnormalities of the IGF‐I system and signaling, a state of chronic low‐grade inflammation and oxidative stress, increased hormone biosynthesis and pathway, release of metabolic substrates and extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules.

5.1. Impact of adipocytes on endocrine response

In addition to their role on the systemic changes associated with obesity, adipocytes are progressively taking center stage in the context of tumor stroma‐related studies. In the breast, cancer epithelial cells are immersed in a fatty environment, and heterotypic interactions between these two cellular types at the invasive tumor front have been shown to induce the proliferation, migration, invasion and metabolic rewiring of different breast cancer cell models. 16 , 95 A combination of direct co‐culture and conditioned medium approaches has extensively demonstrated the existence of reciprocal and functional signalings. Indeed, tumor cells are able to shape the fate of adipocytes by altering their gene expression as well as signaling factor secretion and the so‐called “cancer‐associated adipocytes,” as a consequence of their close localization, would promote tumor aggressiveness. 16 , 95 However, up to now, only few reports have applied a such experimental design to bring out the influence of this dialogue on endocrine treatment resistance. Using a co‐culture model between MCF‐7 breast cancer cells and mammary adipocytes obtained from women with normal weight, overweight and obesity, Bougaret et al. demonstrated that the anti‐proliferative effects of tamoxifen were counteracted by obese mammary adipocytes. 96 Co‐culturing MCF‐7 cells with human mammary adipocytes exposed to high glucose resulted in enhanced CTGF (Connective Tissue Growth Factor) mRNA levels and in decreased tamoxifen responsiveness of breast cancer cells, whereas these effects were reversed by inhibition of adipocyte‐released interleukin (IL) 8. 97 Adipose microenvironment was found to double mammary cancer cell proliferation and interfere with the action of both tamoxifen and fulvestrant. 98 Conditioned medium collected from obese adipose stem cells treated with Letrozole was still able to induce proliferation of breast cancer cells as compared to that collected from lean adipose stem cells. 99 More recently, Morgan et al. proposed an organotypic mammary duct model to investigate how the mammary stromal cells of women with normal weight or obesity may differentially affect response to the AI anastrozole. 100 It was observed that MCF‐7‐derived ducts co‐cultured with obese‐derived stromal cells exhibited higher maximal aromatization‐induced ER transactivation and reduced sensitivity to anastrozole compared to lean cultures, a difference not seen on a conventional 2‐dimensional system. In this organotypic platform, tamoxifen was found to be more effective than anastrozole to decrease aromatization‐induced ER transactivation and proliferation in breast cancer cells. 100 Alternatively, blood serum collected from patients following menopause affected by breast cancer and pooled according to their BMI categories (control [normal weight]: 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2; obese: ≥30.0 kg/m2) was used to treat MCF‐7 and T47D breast cancer cells. Interestingly, obesity‐associated circulating factors stimulated tumor progression and may induce endocrine resistance through an enhanced nongenomic ERα crosstalk with the phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways. 101

On the other hand, few mouse models of obesity have been developed and characterized to study the reduced drug responsiveness associated with excessive adiposity. Ovariectomized athymic nude mice were fed an obesogenic high fat sucrose diet or a low fat diet as a control for 6 weeks and then inoculated with aromatase‐overexpressing MCF‐7 breast cancer cells. 102 Obese mice exhibited greater tumor growth rates, diminished response to letrozole and quicker acquired resistance than lean mice. Furthermore, by grafting patient‐derived ER‐positive tumors into mice that are susceptible to diet‐induced obesity, it was observed that obese environment potentiated the growth of ER‐positive tumors and sustained tumor progression after estrogen withdrawal. 103 At the molecular level, adiposity and redundant energy activate fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) in breast tumors through FGF‐1 produced by hypertrophic adipocytes during adipose tissue expansion, thus establishing a tumor environment that can drive endocrine therapy resistance. 103 Conversely, in mouse models of hormone‐receptor‐positive breast cancer, it has been demonstrated that periodic fasting or a fasting‐mimicking diet (i) increases the anti‐tumor activities of tamoxifen and fulvestrant; (ii) promotes long‐lasting tumor regression and reverts acquired resistance in the presence of fulvestrant and a cyclin‐dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitor. This occurs through a reduction of circulating insulin‐like growth factor 1 (IGF‐1), insulin and leptin and a consequent inhibition of the Akt/mTOR axis. 104 Nevertheless, most of the studies that attempt to unravel the molecular mechanisms explaining the impact of obesity on sensitivity to hormonal therapy have been focused on the role of individual molecules within adipocyte secretome panel. These factors, through the activation of various intracellular signaling pathways and transcription factors, may significantly impact growth, local invasion, and metastatic spread of breast cancer cells during endocrine treatments.

5.2. Impact of adipokine imbalance on endocrine response

The pathological expansion of white adipose tissue in obesity leads to the development of a dysfunctional adipose tissue which produces a large variety of heterogeneous bioactive peptides, named as adipokines. At present, more than 100 different adipokines have been identified, and amongst these, leptin has been the most intensively studied molecules for its influence on breast cancer progression and therapy response. 14 , 105

Leptin is a 16‐kDa pleiotropic neuroendocrine peptide hormone secreted by adipocytes in proportion to fat mass and normally functions to control food intake, energy homeostasis, immune response, and reproductive processes. A growing body of evidence has clearly showed that leptin, through binding of its own receptor and cross‐talking with other signaling molecules (i.e., estrogens, growth factors, and inflammatory cytokines) exerts multiple protumorigenic action, including increased cell proliferation, transformation, anti‐apoptotic effects, self‐renewal, and reduced efficacy of breast cancer treatments (reviewed in the literature 14 , 106 ) (Figure 1). In this latter concern, the obesity‐related adipokine leptin has been shown to lower sensitivity to tamoxifen in “in vitro” models. It has been observed that leptin treatment protects ERα‐positive breast cancer cells from the anti‐proliferative activity of tamoxifen, 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 and the synergy between the leptin/ObR (leptin receptor)/STAT3 (signaling transducer and activator of transcription 3) signaling axis with the membrane tyrosine kinase receptor HER2 pathway induces tamoxifen resistance via the regulation of apoptosis‐related genes. 111 Leptin, at concentrations mimicking plasmatic levels found in individuals with obesity, also diminished the efficacy of 4‐hydroxytamoxifen, the major active metabolite of tamoxifen. 96 Furthermore, we have shown that the reduced sensitivity of breast cancer cells to tamoxifen treatment may result from an up‐regulation of the heat‐shock protein 90 (Hsp90) and a consequent increase of HER2 protein expression. 112 Accordingly, Qian et al. demonstrated that ObR knockdown significantly improved the inhibitory effects of tamoxifen on proliferation and survival of tamoxifen‐resistant breast cancer cells. 113 Leptin was also able to hamper the action of fulvestrant in MCF‐7 cells. 114 Chronic leptin stimulation was found to increase the resistance to both tamoxifen and fulvestrant antiestrogen agents in another report. 115 More recently, we have shown a novel mechanism by which leptin signaling pathway impacts AI resistance through an enhanced cross‐talk between anastrozole‐resistant breast cancer cells and macrophages within the tumor microenvironment. 116

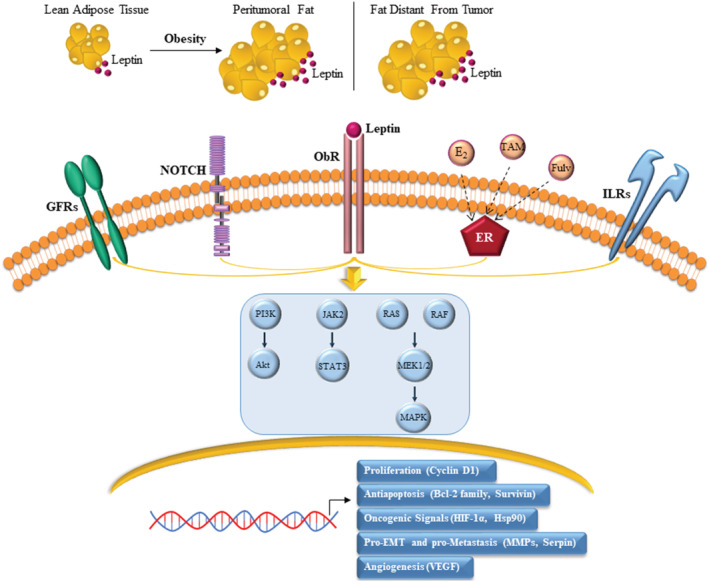

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms linking leptin with breast cancer progression and endocrine resistance. Hypertrophic and hyperplastic adipose tissue expansion in obesity is associated with an increased local and systemic production of the adipokine leptin. Leptin binds to its own receptor (ObR) expressed in breast cancer cells and interacts with multiple oncogenic signalings, including growth factor receptor (GFR), Notch, estrogen receptor (ER), and inflammatory interleukin receptor (IL) signalings. This leads to the activation of various signal transduction pathways, such as PI3K/Akt, JAK2/STAT3 and Ras/Raf/MAPK, that are known to function as key determinants of tumor progression in spite of endocrine treatment. Tam: tamoxifen; Fulv: fulvestrant; E2: 17β‐estradiol; HIF‐1α: Hypoxia‐inducible factor‐1 α; Hsp90: Heat shock protein 90; MMPs: Matrix metalloproteinases; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor

The involvement of other adipocytokines, including adiponectin, visfatin, chemerin, and resistin, in the link between obesity and endocrine resistance remains to be determined.

5.3. Impact of IGF‐I system abnormalities on endocrine response

Obesity and its connected metabolic syndrome generate an environment characterized by enhanced circulating levels of insulin and its related growth factors, especially IGF‐1. There are several lines of evidence reporting that dysregulation of the IGF‐1 system and increased signaling through activation of IGF‐1 receptor (IGF‐1R) are attractive mechanisms that participate to acquired endocrine resistance in breast cancer (Figure 2). Indeed, tumor cells express IGF‐1R as well as insulin receptor (INSR) and binding to their own ligands (e.g., IGF‐1, IGF‐2, and insulin) 117 primes receptor autophosphorylation, phosphorylation of downstream substrates, such as insulin receptor substrate (IRS 1–4) proteins, and subsequent induction of important signal transduction cascades, including the MAPK, PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Janus‐activated kinase (JAK)/STAT pathways. 118 Recently, it has been reported that INSR also translocates from the cell surface into the nucleus, where it interacts with transcriptional machinery at promoters genome‐wide, and regulates genes linked to insulin‐related functions, such as lipid metabolism and diseases, including cancer. 119

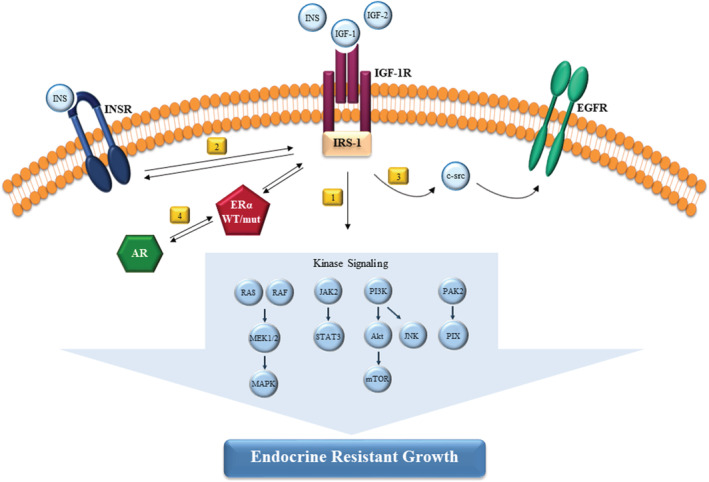

FIGURE 2.

Role of IGF‐1R signaling axis in mediating endocrine resistance. Obesity results in increased concentrations of insulin‐like growth factor 1 (IGF‐1), IGF‐2 and insulin (INS). Ligand binding to the IGF‐I receptor (IGF‐1R) extracellular domain leads to conformational changes of the intracellular region and intrinsic receptor tyrosine kinase. Then, IGF‐1R through tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate (IRS‐1) adaptor proteins activate a number of downstream kinase signaling to promote endocrine resistance in breast cancer cells (1). IGF‐1R and INSR crosstalk represents another mechanism of escape from hormone dependence (2). IGF‐1R activation by IGF‐2 regulates basal and ligand‐activated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling and cell proliferation in a c‐src dependent manner in resistant cells (3). Androgen receptor (AR) and estrogen receptor (ERα) functionally collaborate to induce resistance via activation of IGF‐1R and PI3K/Akt pathways (4)

As early as 1993, it was found that the lack of estrogen antagonist activity of tamoxifen in breast cancer resistant cells was dependent on the stimulation of IGF‐1/IGF‐1R signaling axis. 120 Later, it was demonstrated that up‐regulation of IGF‐1R expression by 17β‐estradiol along with an increased sensitivity to IGF‐1 may function to bypass growth inhibition mediated by tamoxifen in breast cancer cells, 121 and overexpression of IGF‐1R together with IRS‐1 may facilitate estrogen independence. 122 , 123

The development and growth of tamoxifen‐resistant breast cancer cells have also been proven to rely on a unidirectional productive IGF‐1R/epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) interaction mechanism dependent on c‐src activation. 124 Similarly, Nicholson et al. have suggested that IGF‐1R signaling may play a supportive role to the EGFR/HER2 pathway in controlling tamoxifen‐resistant proliferation. 125 Furthermore, other signalings, such as c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK) and p21‐activated kinase 2/PAK‐interacting exchange factor (PAK2/PIX) axis are indicated as effectors of IGF‐1R‐mediated antiestrogen insensitivity. 126 , 127

Studies have also shown that increased signaling through IGF‐1R with consequent activation of IRS‐1 and the PI3K/Akt survival pathway leads to resistance to AI treatments. 7 , 128 It has been reported by Dr. Santen's laboratory that an enhanced cross‐talk between IGF‐1R and ERα stimulates rapid nongenomic effects in long‐term estradiol deprived (LTED) cells, which are responsible for activation of MAPK and PI3K/Akt signalings that drive breast cancer proliferation by estrogen in a hypersensitive manner. 7 , 129 IGF‐1R up‐regulation has also been reported to occur after long‐term estrogen deprivation 130 , 131 and in anastrozole‐refractory breast cancer cell lines. 132 , 133 In particular, Rechoum et al. demonstrated that androgen receptor cooperates with ERα in supporting cell escape to anastrozole inhibitory effects, through the activation of IGF‐1R and PI3K/Akt pathways. 133

A kinome‐wide siRNA screen demonstrated that INSR in addition to IGF‐1R is required for growth of LTED cells and treatment with the dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor OSI‐906 prevented the growth of hormone‐independent cells “in vitro” and tumors “in vivo.” 134 OSI‐906 in combination with fulvestrant was more effective in inhibiting hormone‐independent tumor progression than either drug alone. 134 Similarly, inhibition of INSR was demonstrated to be necessary to manage tamoxifen‐resistant breast cancer progression. 135

A study by Creighton et al. identified a set of genes that were modulated by IGF‐1 which were strongly associated with cell proliferation, metabolism, DNA repair and possibly to hormone independence in breast cancer cells. 136 In three large independent data sets of profiled human breast tumors, the IGF‐1 signature obtained from MCF‐7 cells was indicative of a poor outcome. 136 An insulin/IGF‐1 gene expression signature predicted recurrence‐free survival in patients treated with tamoxifen. 137 Moreover, in 563 patients with primary breast cancer, IGF‐1R activation was correlated with increased phosphorylation of PI3K and MAPK pathways and intrinsic tamoxifen resistance. 138 High IGF‐1R levels after neoadjuvant endocrine treatment represent a poor prognostic factor in patients with breast cancer. 139 Analysis of tissue microarrays from primary tumors isolated from patients enrolled in the international, randomized, phase III clinical trial PO25 highlighted an “ER activity profile” with an up‐regulation of PR, IGF‐1R and Bcl‐2 as a promising selection criterion regarding prediction of response to letrozole versus tamoxifen. 140 On the contrary, some data indicated that lower IGF‐1R expression was associated with a worse prognosis for women under tamoxifen or AI therapies. 141 , 142

More recently, enhanced IGF‐1 response was proposed as a novel determinant of endocrine resistance in ESR1 mutant breast cancer cells. 10 , 143 , 144

However, although these concepts, clinical studies have failed to ascertain a significant effect of IGF‐1R inhibition in therapeutic settings. Perhaps, a more comprehensive strategy of targeting IGF‐1R network and a more accurate selection of patients (i.e., women with obesity) could be the avenues to harness.

5.4. Impact of obesity‐induced inflammation and oxidative stress on endocrine response

One of the most important features behind the link existing between obesity and breast cancer endocrine resistance is low‐grade chronic inflammation, due to the release of several inflammatory mediators from both the tissue resident cells (e.g., adipocytes) as well as from immune cells within those tissues. 145 Indeed, excessive caloric intake during obesity results in adipose tissue expansion, characterized by white adipocyte hyperplasia and/or hypertrophy, that leads to increased secretion of chemokines and inflammatory cytokines as well as to the recruitment and polarization of macrophages to a pro‐inflammatory state. Adipose tissue of people with a healthy weight is characterized by a small number of macrophages, while this number rises in that of individuals with obesity. 145 Importantly, the degree of infiltration of adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) has been significantly correlated with tumor size, recurrence, obesity and the development of tamoxifen resistance. 146 An increase in ATMs might result in the formation of “crown‐like” structures (CLSs) that, surrounding dying or dead adipocyte, contribute to both local and systemic inflammation by secreting various inflammatory cytokines. 145 , 147 CLSs are increased in breast adipose tissue from patients with breast cancer and are more abundant in patients with obesity conditions. 148 , 149 , 150 Moreover, the CLS index‐ratio from individuals with obesity seems to influence breast cancer recurrence rates, survival, and therapy response. 145 , 147 , 149 , 150

Adipocytes and macrophages interaction has been shown to lead to the activation of the proinflammatory nuclear factor‐κB (NF‐κB). It has been demonstrated that activation of NF‐κB oncoprotein desensitizes cell response to estrogen withdrawal, tamoxifen and fulvestrant treatments 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 and blocking NF‐κB‐dependent pathways can restore therapeutic sensitivity. 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 , 160 Accordingly, elevated NF‐κB activity identified a high‐risk subset of primary breast tumors with early relapse on adjuvant tamoxifen therapy and adding an NF‐κB inhibitor to endocrine regimens resulted in a clinical benefit rate of 22% in patients who developed metastasis under antihormone treatment. 158 , 161 , 162 Moreover, it has been outlined an important role for this transcription factor in acquired resistance to AIs in cell models as well as in clinical specimens. 163 Studies on the global transcriptional consequences induced by AI treatment in a neoadjuvant setting also revealed an inflammatory/immune gene expression signature as the strongest correlate of poor antiproliferative responses. 164 , 165

Obesity is known to induce adipose breast tissue hypoxia, leading to the up‐regulation of the adipocyte hypoxia‐inducible factor 1α (HIF‐1α) gene expression, 166 that has been proposed to play a critical role in both inflammation and therapy failure. 167 , 168 In response to hypoxia, increased levels of cytokines and chemokines are released, contributing to create a microenvironment favorable for adipose tissue expansion and propitious to overcome hormone therapy. 169 , 170

Adipokine dysregulation arising during obesity is also important in terms of adipose tissue inflammation. For instance, it has been demonstrated that leptin impacts the phenotype and the function of immune cells, including macrophages, to stimulate chemiotaxis and the secretion of additional inflammatory cytokines. 116 , 171 , 172 , 173

Thus, obesity may potentially fuel resistance to endocrine therapeutic treatments via systemic and local overproduction of several proinflammatory molecules. A list of the major obesity‐associated mediators involved in this event is provided in Table 3. 155 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 As examples, C‐X‐C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12)‐CXCR4 chemokine signaling axis, via MAPK pathway, stimulated the progression to hormone‐independent and therapeutic‐resistant phenotypes 174 and proinflammatory cytokine treatments (i.e., IL‐1β and TNF‐α) of breast cancer cells, through increased phosphorylation of ERα at serine (S) 305 in the hinge domain, caused endocrine therapy failure. 178 Of note, the serum of individuals with obesity frequently displayed elevated proinflammatory cytokine levels, 181 , 182 whose concentrations have been associated with poor outcome of patients and treatment resistance in breast cancer. 183 , 184 , 185 , 186

TABLE 3.

Proinflammatory mediators involved in breast cancer endocrine resistance

| Factor | Model | Mechanism | Therapeutic intervention | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL12 |

“In vivo” “In vitro” |

ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK signaling |

Fulv | 174 |

| IL‐6 |

Human “In vivo” “In vitro” |

STAT3/NOTCH3‐mediated induction of mitochondrial activity and metabolic dormancy |

Fulv Tam |

175 |

|

“In vivo” “In vitro” |

STAT3‐mediated self‐renewal and metabolic rewiring | Tam | 177 | |

| “In vitro” | ERα phosphorylation at S118 and NF‐kβ/STAT3/ERK activation |

Fulv Tam |

155 | |

| IL‐1β | “In vitro” | ERα phosphorylation at S305 and NF‐kβ activation |

Tam EW |

178 |

| TGF‐β | “In vitro” | EGFR‐, IGF1R‐, and MAPK‐dependent nongenomic ERα signaling | Tam | 179 |

| IL‐33 |

Human “In vitro” |

Cancer stem cell properties | Tam | 176 |

| TNF‐α | “In vitro” | ERα phosphorylation at S305 and NF‐kβ activation |

Tam EW |

178 |

| “In vitro” | ERα phosphorylation at S118 and NF‐kβ/STAT3/ERK activation |

Fulv Tam |

155 | |

| CCL2 |

Human “In vitro” |

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling | Tam | 180 |

Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; CCL2, CC‐chemokine ligand 2; CXCL12, C‐X‐C motif chemokine ligand 12; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERα, estrogen receptor α; ERK, extracellular‐signal‐regulated kinase; EW, estrogen withdrawal; Fulv, fulvestrant; IGF1‐R, insulin‐like growth factor 1 receptor; IL, interleukin; MAPK, mitogen‐activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF‐ĸβ, nuclear factor‐kappa B; NOTCH3, notch receptor 3; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; S, serine; Tam, tamoxifen; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor β; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor.

Convincing association between chronic inflammation and endocrine therapy resistance also relies on excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), as a result of metabolic and inflammatory changes. 187 ROS could potentially lead to progressive genetic instability, tumor progression, and metastasis through activation of important transducers, including the PI3K/Akt pathway and various transcription factors, such as NF‐κB, STAT3, HIF1‐α, activator protein‐1 (AP‐1), nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and NF‐E2 related factor‐2 (Nrf2). Activation of these nuclear factors can result into the expression of over 500 different genes (i.e., growth factors, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines) that can affect therapy response. 188 Indeed, chronic exposure to oxidative stress can transform estrogen‐responsive non aggressive breast cancer cells into estrogen‐independent aggressive phenotypes through epigenetic mechanisms. 189 Proteomics of xenografted human breast cancer identified proteins related to oxidative stress processes that could be involved in the resistance phenomenon. 190 The upregulation of NRF2 in breast cancer appears to be correlated with treatment resistance to tamoxifen. 152 , 191 The development of acquired tamoxifen resistance of xenograft MCF‐7 tumors “in vivo” was associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress along with increased phosphorylation of Jun NH2‐terminal kinases (JNKs)/stress‐activated protein kinases (SAPKs) and AP‐1 activity. 192 On the other hand, anti‐estrogen treatment adds a constant state of oxidative stress, which further supports a shift toward a pro‐oxidant environment. 193

Therefore, obesity‐sustained inflammatory/oxidative environment leads to a vicious circle, which may further promote tumor progression under hormone therapy. Further studies are certainly needed to better define the molecular details underlying these events; however, it is tempting to speculate that patients with breast cancer and obesity undergoing endocrine treatments may benefit from the use of anti‐inflammatory agents and/or antioxidant compounds (e.g., nutraceuticals).

5.5. Impact of adipocyte‐derived metabolites on endocrine response

Breast adipose tissue is a source of free fatty acids and cholesterol required for energy and building blocks to support abnormally increased proliferation of cancer cells. 194 Recent studies have outlined lipid metabolism‐related traits as key enablers of resistance to endocrine therapies. Indeed, crosstalk between estrogen signaling elements and important metabolic regulators aids tumors to rewire their metabolism and this represents an important step for the selection of drug‐resistant and metastatic clones. 195

It has been demonstrated that cholesterol and its biosynthetic precursor, mevalonate, through the activation of estrogen‐related receptor alpha (ERRα) pathway, can trigger an intense metabolic switching, propagation of cancer‐stem like cells, aggressiveness and resistance to tamoxifen treatment in breast cancer cells. 196 Activation and expression of proteins stimulated by these two metabolites are comparable to those detected in tamoxifen‐resistant MCF‐7 breast cancer cells. 196 Transcriptomic analysis of tamoxifen‐resistant cell lines has shown altered gene expression patterns associated with protein metabolism, especially with cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. For instance, genes associated with activation of sterol regulatory element‐binding factor (SREBF), a transcription factor and primary activator of the mevalonate pathway, were up‐regulated in tamoxifen‐resistant T47D cells. 197 Chu et al. observed that aberrant expression of free fatty acid receptor 4 (FFAR4), also known as GPR120, can serve as a prognostic biomarker for patients with ERα‐positive breast cancer and treated with tamoxifen. Accordingly, FFAR4 signaling activation by both endogenous and synthetic ligands conferred resistance to tamoxifen in ER‐positive breast cancer cells, which was dependent on MAPK and Akt pathways. 198 Knock‐down of cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) rendered breast cancer cells more susceptible to intrinsic apoptosis and increased the cytotoxic effects of tamoxifen. 199 In addition, heregulin‐mediated HER2/HER3 pathway promoted expression of the lipogenic enzyme fatty acid synthase (FASN) as part of the endocrine resistant molecular program activated in luminal B‐like ER‐positive cells. 200 On the other hand, FASN has been shown to play a role in regulating HER2 expression, thus offering a rationale for a therapeutic targeting of this enzyme in HER2‐dependent resistant carcinomas. 201 Indeed, “in vitro” and “in vivo” treatment with a FASN inhibitor restored the sensitivity to the anti‐tumor activity of tamoxifen and fulvestrant. 200 Inhibition of FASN activity was also associated with a marked reduction of growth in tamoxifen‐resistant cell lines and tumor xenografts. 202

Concerning AI resistance, increased expression of many genes involved in cholesterol metabolism, following epigenetic reprogramming, was observed in resistant models and this signature predicted shorter recurrence‐ and metastatic‐free survival in a subgroup of patients with ER‐positive breast cancer treated with AIs. 203 Transcriptional profiling analysis in LTED variant cell lines from human invasive lobular breast cancer cells revealed a high expression of sterol regulatory element‐binding protein 1 (SREBP1), a master regulator of lipid synthesis, along with an activation of several SREBP1 downstream targets implicated in fatty acid synthesis, such as FASN. 203 “In silico” gene expression analysis in clinical specimens from a neo‐adjuvant endocrine trial (3‐month regimen with Letrozole) demonstrated a significant correlation between increased SREBP1 expression and lack of clinical response, thus implicating a role for the lipogenic phenotype in driving estrogen independence. 204

Interestingly, Simigdala et al. identified the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway as a potentially important adaptive resistance mechanism in breast cancer models that retained ER expression. Genes encoding enzymes within this pathway were significantly associated with poor response in two independent cohorts of patients treated with neoadjuvant endocrine therapy. 205 Of note, some of these genes are already included in clinically relevant signatures. For instance, 7‐dehydrocholesterol reductase (DHCR7) is part of the eight‐gene EndoPredict profile. 206

In line with these observations, multiple studies demonstrated the potential utility of statins in breast cancer. 207 , 208 On the other hand, this relatively novel field of research may propose additional attractive targets that deserve future investigation for the prevention and treatment of patients with endocrine‐resistant tumors, especially in the setting of obesity.

5.6. Impact of obesity‐related aromatase expression on endocrine response

Adipose tissue, being an endocrine organ, can regulate the production and bioavailability of sex hormones, which can mediate the association of obesity with reduced endocrine response, mainly AIs. Indeed, despite the activation of multiple membrane‐associated signalings, considerable findings indicate that ERα remains a main mitogenic driver of tumor progression mediated by both estradiol and SERMs in resistant models. 8 , 209 , 210 , 211

Adipocytes strongly express aromatase—a cytochrome P450 enzyme encoded by the CYP19 gene—that is responsible of increased estrogen biosynthesis; consequently, excessive fat mass may impact both circulating and locally secreted estrogen concentrations in breast tumors. Accordingly, aromatase levels and enzymatic activity are greater in the breast tissue of individuals affected by obesity than of ones with lean weight. 212 Several studies have established that obesity can drive adipose inflammation which leads to aromatase up‐regulation and enhanced estrogen signaling in breast and other adipose depots. An increased aromatase expression has been found in inflamed adipose tissue of women with obesity and mice due to pro‐inflammatory mediators released by CLS‐associated macrophages. 149 , 213 , 214 CYP19 transcription has been shown to be amplified by the binding of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), TNF‐α, and IL‐1β with their own receptors. 213 , 215 , 216 , 217 , 218 , 219 , 220 Positive correlations between cyclooxygenase (COX) and aromatase expression in human breast cancers has also been identified. 221 , 222 , 223 The severity of breast inflammation (CLS of the breast index), which correlated with BMI as well as adipocyte sizes, was strikingly associated with elevated levels of aromatase expression and activity in both the mammary gland and fat depots, further highlighting the existence of an obesity‐inflammation‐aromatase axis. 149 In addition, growth factors, including IGF‐1, could stimulate aromatase expression in both breast cancer and adjacent adipose fibroblasts and stromal cells via transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulatory mechanisms. 224 , 225 , 226 In this regard, we have shown a novel molecular mechanism by which estradiol, through an increased cross‐talk with growth factor and tyrosine‐kinase c‐src transduction signalings, can phosphorylate and activate the enzyme aromatase, creating a short non genomic feedback able to enhance local estradiol production and further promote breast tumor progression. 227 , 228 Of particular interest is that the obesity cytokine leptin up‐regulated aromatase gene expression and enzymatic activity in breast cancer cells, leading to increased estrogen levels and ERα transactivation. 229 A schematic overview of these findings is illustrated in Figure 3.

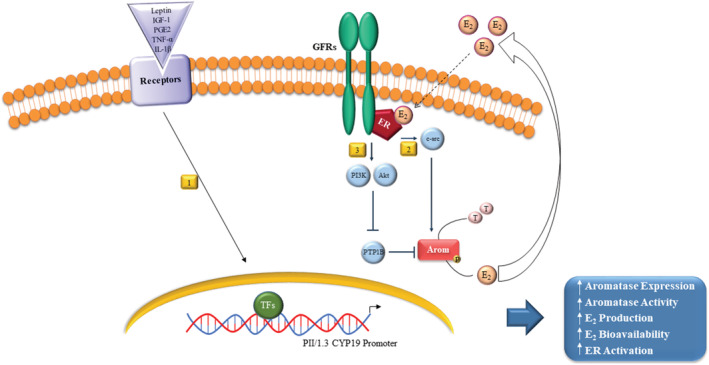

FIGURE 3.

Obesity, aromatase and breast cancer: a mechanistic overview. Leptin, insulin‐like growth factor 1 (IGF‐1), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, and interleukin (IL) 1β by the binding with their own receptors could stimulate, via promoter II/I.3, aromatase (Arom) cytochrome P450 (CYP19) gene expression and enzymatic activity in breast cancer cells via transcriptional regulatory mechanisms (1). Aromatase activity is also amplified by estradiol (E2) at posttranscriptional levels through an increase of tyrosine protein phosphorylation (P) mediated by: an enhanced cross‐talk with growth factor receptor (GFR) and the tyrosine‐kinase c‐src transduction signalings (2); an activation of PI3K/Akt pathway and a subsequent inhibition of the tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B (protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B) catalytic activity that impairs PTP1B ability to dephosphorylate aromatase (3). Overall, these events lead to increased aromatase expression/activity, estrogen production/biovailability and estrogen receptor (ER) α activity. TFs: Transcription factors, T: Testosterone

In aggregate, these data, by highlighting the different molecular mechanisms involved in aromatase regulation and breast malignancy in the context of obesity, may suggest the importance to refocus existing treatment strategies, based on the rationale to personalize the dose of AIs required to maximally suppress estrogen production and improve clinical benefit of women with obesity. Future studies are mandatory to delineate this central point.

5.7. Impact of other obesity‐related factors on endocrine response

Adipocytes and adipose‐derived stromal cells secrete ECM molecules that consist of glycoproteins, laminins, fibronectin and collagens. 230 The ECM is extremely pleiotropic, providing a substrate to which cells can adhere, mediating mechanical forces within tissues and serving as a reservoir for growth factors. As a result, the ECM, for instance through integrins and activation of focal adhesion kinases (FAKs), holds a major role in regulating breast cancer cell fate, signaling capacity and therapy resistance. 230 , 231 In this regard, it has been demonstrated that ERα‐positive cells cultured on ECM matrices exhibited estrogen‐independent growth and reduced sensitivity to ER‐targeted therapies. 232 Fibronectin through its interaction with β1 integrin and activation of MAPK and PI3K/Akt pathways protected epithelial cells against tamoxifen‐induced cell death. 233 Importantly, fibronectin prolonged ERα half‐life 234 and stimulated phosphorylation of ERα in serine‐118, 233 a key site involved in ER ligand‐independent activation and tamoxifen resistance. 210 , 235 Using an estrogen‐responsive syngeneic mouse mammary tumor model developing endogenous pulmonary metastases, Jallow et al. demonstrated that a dense/stiff collagen‐I environment fostered tamoxifen agonistic effects to enable proliferation along with activator protein 1 (AP‐1) activity in primary tumors and promote growth of pulmonary metastases. 236 Moreover, conversion of ERα‐positive breast cancer cells into an endocrine‐refractory state, driven by ERα functional loss, was accompanied by EMT processes and dynamic changes in the expression of nodal matrix effectors. 237

Clinically, expression profiling study discovered an ECM gene cluster of six genes [collagen 1A1 (COL1A1), fibronectin 1 (FN1), lysyl oxidase (LOX), secreted protein acidic cysteine‐rich (SPARC), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 3 (TIMP3), and tenascin C (TNC)] which was overexpressed in patients with resistant metastatic disease. 238 In a further report, the same research group estimated the value of the individual gene expression in 1,286 primary breast cancer specimens in terms of prognosis (independent of therapy response), clinical benefit from tamoxifen treatment, or both. 239 FN1, LOX, SPARC, and TIMP3 expression levels were associated with outcomes, while high levels of TNC, an adhesion‐modulating ECM protein highly expressed in breast cancer microenvironment was associated with shorter distant‐metastasis free survival and progression‐free survival after adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. 240 Interestingly, despite evidence of patient heterogeneity at the gene level, alterations in common functional pathways including ECM receptor interactions and focal adhesions were observed in endocrine‐resistant metastatic tumors. 241

Adipocytes also express other proteins such as osteopontin (OPN), known as SPP1 (secreted phosphoprotein 1), a 44‐kDa integrin‐binding glyco‐phosphoprotein that functioning both as a cytokine and as an extracellular matrix molecule has been implicated in inflammation, tumor progression, bone metastasis and drug resistance. 242 , 243 OPN expression was significantly higher in breast tumor‐adjacent adipocytes than in distant adipose tissue from the same breast and resulted in increased cell growth, invasion, and angiogenesis. 244 It has been reported that elevated serum OPN levels may be associated with advanced metastatic cancer 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 and recent meta‐analyses revealed that OPN overexpression is positively correlated with poor outcomes. 249 , 250 Indeed, the clinical utility of this protein is documented in the CancerSeek blood test, screening for eight solid tumors, including breast cancers, which incorporates OPN as one of protein biomarkers. 251 In a case‐control study, high SPP1 gene expression predicted high risk of distant recurrence among patients with ER‐positive breast cancer treated with tamoxifen, 252 while OPN exon 4 variant has been identified as a predictor of sensitivity to tamoxifen in a limited group size. 253 Furthermore, OPN regulates the function of adipocytes through changes in differentiation processes and inflammatory signalings, such as the induction of integrin, CD44 and inflammatory cytokine expressions, 230 , 254 thus providing further links between obesity and hormone response.

Certainly, further clinical validation and functional studies of the dynamic interactions between ECM proteins and tumor cells may help to address the clinical issue of endocrine resistance, providing potential signatures for treatment decisions and suitable druggable targets for therapeutic intervention.

6. CYCLIN‐DEPENDENT KINASE (CDK) 4/6 INHIBITORS, ENDOCRINE THERAPY, AND OBESITY

Preclinical data indicate that cell‐cycle regulators such as CDK 4 and 6 control important metabolic processes such as adipogenesis, lipid synthesis, oxidative pathways, insulin signaling, glucose regulation, and mitochondrial function. 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 Recent studies have also uncovered CDK 4 and 6 as potential targets against diet‐induced obesity, proposing that CDK 4/6 inhibitors could have a direct effect on body fat mass. 260 , 261 In spite of this potential relationship between obesity and CDK 4/6, there are still limited data regarding the impact of BMI on outcomes in patients treated with endocrine therapy and CDK 4/6 inhibitors. This represents an important unanswered question in the management of breast cancer. Indeed, although several trials have delivered favorable results in terms of prolonged progression‐free and overall survival of CDK 4/6 inhibitors (i.e., palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib) in combination with endocrine therapy in patients with ER‐positive, HER2‐negative metastatic breast cancers, 262 development of “de novo” or acquired resistance to the combined treatments may occur. 263

In a small retrospective cohort, no difference in survival was found in patients receiving Palbociclib or Ribociclib and endocrine therapy, according to BMI. 264 Similarly, results of a pooled, individual patient‐level analysis of the MONARCH 2 (NCT02107703) and MONARCH‐3 (NCT02246621) randomized, placebo‐controlled phase 3 clinical trials conducted by the same research group showed that adding abemaciclib to fulvestrant or an AI prolongs survival of patients regardless of BMI, unveiling a benefit of women with obesity from these regimens. Nevertheless, a better effect of abemaciclib was evident in patients with normal weight/underweight compared to those with overweight/obesity, encouraging to maintain a healthy weight also in this clinical setting. 265 Surely, future research integrating body composition parameters in these patients and using different CDK4/6 inhibitors should be pursued for a more precise analysis on the potential consequences of obesity in terms of treatment design.

7. CONCLUDING REMARKS