Abstract

Background:

Obesity remains a significant public health issue in the U.S. Each week, millions of infants and children are cared for in Early Care & Education (ECE) programs, making it an important setting for building healthy habits. Since 2010, thirty-nine states promulgated licensing regulations impacting infant feeding, nutrition, physical activity, or screen time practices. We assessed trends in ECE regulations across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) and hypothesized that states included more obesity prevention standards over time.

Methods:

We analyzed published ratings of state licensing regulations (2010–2018) and describe trends in uptake of 47 high-impact standards derived from Caring for Our Children’s, Preventing Childhood Obesity special collection. National trends are described by 1) care type (Centers, Large Care Homes, and Small Care Homes); 2) state and U.S. region; and 3) most and least supported standards.

Results:

Center regulations included the most obesity prevention standards (~13% in 2010 vs. ~29% in 2018) compared to other care types, and infant feeding and nutrition standards were most often included, while physical activity and screen time were least supported. Some states saw significant improvements in uptake, with six states and D.C. having a 30%-point increase 2010–2018.

Conclusions:

Nationally, there were consistent increases in the percentage of obesity prevention standards included in ECE licensing regulations. Future studies may examine facilitators and barriers to the uptake of obesity prevention standards and identify pathways by which public health and healthcare professionals can act as a resource and promote obesity prevention in ECE.

Keywords: Early Care and Education, Child Care, Obesity Prevention, State Licensing Regulations, National Policy Surveillance

INTRODUCTION

Obesity among children remains a significant public health problem. Obesity prevalence among U.S. youth (aged 2–19 years) is 19%, including approximately 14% of young children aged 2–5 years1,2. Obesity disproportionately affects children from lower-income households and certain racial/ethnic minority groups3. Children with obesity are more likely to have health conditions such as type II diabetes and high blood pressure, and experience social stigma and bullying4–6. Childhood obesity is also associated with adult obesity and its negative health outcomes7.

Numerous expert bodies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Academy of Medicine, recognize Early Care and Education (ECE) as an important setting for preventing childhood obesity and introducing healthy behaviors8–10. With nearly 11 million U.S. children enrolled in licensed out-of-home child care programs11, there may be a significant opportunity to leverage ECE facilities to not only prepare a child academically, but to also expose them to healthy lifestyle habits early in life. Research identifies child care licensing as an important policy lever for scaling high-quality best practices for obesity prevention in ECE programs12,13.

States are responsible for licensing child care programs within their jurisdiction to ensure they meet minimum health and safety requirements for operation. The licensing system offers built-in feedback loops, in the form of routine monitoring, which holds ECE providers accountable for meeting requirements to legally operate. Most states open their licensing regulations for revision every three to five years, although this can vary greatly by state14. In the last decade, some states have adopted licensing requirements that go beyond traditional health and safety rules, to include health-promoting standards, such as infant brain development, emotional well-being, healthy eating, and physical activity15.

Caring for Our Children (CFOC) comprises national standards that represent the ‘gold standard’ in high quality, health and safety policies and practices for ECE programs16. CFOC 3rd ed. identified standards to prevent childhood obesity and published them in a special collection titled, Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education Programs17. Leading child health and public health organizations endorsed these standards, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, and the National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education (NRC)17. To further refine the standards, identifying those most likely to prevent childhood obesity when included in licensing regulations, the NRC convened a national advisory committee in 2010. Through a review of scientific evidence, and a consensus panel of expert opinion, a sub-set of 47 high-impact standards emerged. NRC organized the 47 standards into four overarching categories: 1) Infant Feeding Standards (n=11); 2) Nutrition Standards (n=21); 3) Physical Activity Standards (n=11); and 4) Screen Time Standards (n=4). Public health and state licensing officials can include these science-based standards in ECE regulations to help prevent childhood obesity18.

The objective of this study was to examine national trends from 2010 to 2018 in the uptake of high-impact obesity prevention standards in child care licensing regulations. Authors describe trend differences by a) child care type (Center, Large Family Care Homes, and Small Family Care Homes); b) state and U.S. region; and c) individual high-impact standards most and least supported in licensing regulations over time. This is the first study to systematically assess and describe trends in the uptake of CFOC’s 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards in ECE licensing regulations.

METHODS

Since 2010, the NRC has systematically collected, coded, and rated state-based ECE licensing regulations on the extent to which they include CFOC’s 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards. Each year, NRC uses a systematic screening methodology to identify new or revised state licensing regulations that impact infant feeding, nutrition, physical activity, and/or screen time limits in licensed facilities. Once identified, the study team reviews and rates the regulatory language against a developed coding tool. Using an ordinal rating scale, shown below, a final rating is assigned which describes the extent to which each of the 47 high-impact standards are included in state licensing regulations. NRC conducts and publishes its ratings for all 50 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) on an annual basis. A full description of NRC’s methodology can be found on their website18.

0 = State does not regulate child care type

1 = Regulation contradicts the obesity prevention standard

2 = Regulation does not address the obesity prevention standard

3 = Regulation partially includes the obesity prevention standard

4 = Regulation fully includes the obesity prevention standard

The current study analyzes NRC’s annual ratings from all 50 states and D.C. from 2010 to 2018. For the primary analysis, trends were calculated as the proportion of 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards fully supported (rated as ‘4’) in state licensing regulations for each care type separately, Centers, Large Care Homes, and Small Care Homes. For example, the national percentage of standards fully included in Center-based licensing regulations is calculated as:

Because some states do not consistently license Small or Large Care Homes, and because of limited differences in uptake of high-impact standards across the three care types, subgroup analyses were confined to licensing regulations for Centers. Subgroup analyses examined trends in the south, northeast, west, and mid-west, as defined by U.S. Census categories19. Additional subgroup analyses identified which of the 47 high-impact standards were most and least supported in state licensing regulations over time. Authors also analyzed the extent to which United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) meal pattern standards align with some of CFOC’s infant feeding and nutrition standards and assessed differences in uptake over time.

RESULTS

Differences by care type (Centers, Large Family Care Homes, and Small Family Care Homes)

Primary analyses show gradual, yet consistent, increases in the percentage of high-impact obesity prevention standards (n=47) fully embedded in state-level licensing regulations for Centers, Large Family Care Homes, and Small Family Care Homes (Table 1). For all years, the 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards were most often included in licensing regulations for Centers (ranging from 13% in 2010 to 29% in 2018), compared to Large Family Care Homes (ranging from 12% in 2010 to 25% in 2018) and Small Family Care Homes (ranging from 11% in 2010 to 22% in 2018). As seen in Table 1, annual percentage increases averaged 1% to 2% across all care types, except in 2017. In this one year, a sharp 7%-point increase occurred in the proportion of high-impact standards embedded in state licensing regulations for all child care types. Subgroup analyses examining uptake of individual standards showed that improvements were primarily driven by increased inclusion of infant feeding and nutrition standards, which aligned to the CACFP meal pattern standards (Table 2) updated in that same year20.

Table 1.

Percentage of High-Impact Obesity Prevention Standards (n=47) Fully Included in Licensing Regulations by Care Type

| Year | Centers* | Large Care Homes† | Small Care Homesŧ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 13% | 12% | 11% |

| 2011 | 14% | 13% | 11% |

| 2012 | 15% | 15% | 13% |

| 2013 | 17% | 16% | 13% |

| 2014 | 19% | 16% | 14% |

| 2015 | 19% | 17% | 14% |

| 2016 | 21% | 18% | 15% |

| 2017 | 28% | 24% | 21% |

| 2018 | 29% | 25% | 22% |

All 50 states and D.C. promulgate licensing regulations for child care Centers, most often defined as serving 12 or more children, eight weeks to 5 years of age, in a commercial or leased facility.

Louisiana, Georgia, and D.C. did not consistently license Large Family Care Homes annually (2010–2018).

Arizona and Louisiana did not consistently license Small Family Care Homes annually (2010–2018).

Table 2.

Differences in Uptake of High-Impact Infant Feeding and Nutrition Standards in Licensing Regulations for Centers 2020 vs. 2018

| Number of States Fully Including Standard in Licensing Regulations | Aligns with CACFP Meal Pattern | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2018 | |||

| Breastfeeding and Infant Feeding Standards | ||||

| IA1 | Encourage and support breastfeeding and feeding of breast milk by arranging for mothers to feed their children comfortably on-site. | 8 | 11 | |

| IA2 | Serve human milk or infant formula until the age of 12 months, not cow’s milk, unless primary care provider and parent/guardian provide written exception. | 25 | 35 | x |

| IB1 | Feed infants on cue. | 33 | 38 | x |

| IB2 | Do not feed infants beyond satiety; Allow infant to stop the feeding. | 23 | 34 | x |

| IB3 | Hold infants while bottle-feeding; Position an infant for bottle feeding in the caregiver/teacher’s arms or sitting up on the caregiver/teacher’s lap. | 14 | 12 | |

| IC1 | Develop a plan for introducing age-appropriate solid foods (complementary foods) in consultation with the child’s parent/guardian and primary care provider. | 4 | 4 | |

| IC2 | Introduce age-appropriate solid foods no sooner than 4 months of age, and preferably around 6 months of age. | 2 | 30 | x |

| IC3 | Introduce breastfed infants gradually to iron-fortified foods no sooner than four months of age, but preferably around six months to complement the human milk. | 1 | 29 | x |

| ID1 | Do not feed an infant formula mixed with cereal, fruit juice or other foods unless the primary care provider provides written instruction. | 2 | 5 | |

| ID2 | Serve whole fruits, mashed or pureed, for infants 7 months up to one year of age. | 0 | 2 | |

| ID3 | Serve no fruit juice to children younger than 12 months of age. | 0 | 29 | x |

| Nutrition Standards | ||||

| NA1 | Limit oils by choosing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (such as olive oil or safflower oil) and avoiding trans fats, saturated fats and fried foods. | 0 | 1 | |

| NA2 | Serve meats and/or beans - chicken, fish, lean meat, and/or legumes (such as dried peas, beans), avoiding fried meats. | 1 | 1 | |

| NA3 | Serve other milk equivalent products such as yogurt and cottage cheese, using low-fat varieties for children 2 years of age and older. | 0 | 0 | |

| NA4 | Serve whole pasteurized milk to twelve to 24-month-old children who are not on human milk or prescribed formula, or serve reduced fat (2%) pasteurized milk to those who are at risk for hypercholesterolemia or obesity | 0 | 3 | |

| NA5 | Serve skim or 1% pasteurized milk to children two years of age and older. | 2 | 36 | x |

| NB1 | Serve whole grain breads, cereals, and pastas. | 2 | 3 | |

| NB2 | Serve vegetables, specifically, dark green, orange, deep yellow vegetables; and root vegetables. | 3 | 5 | |

| NB3 | Serve fruits of several varieties, especially whole fruits. | 9 | 9 | |

| NC1 | Use only 100% juice with no added sweeteners. | 32 | 40 | x |

| NC2 | Offer juice only during meal times. | 2 | 31 | x |

| NC3 | Serve no more than 4 to 6 oz juice/day for children 1–6 years of age. | 1 | 32 | x |

| NC4 | Serve no more than 8 to 12 oz juice/day for children 7–12 years of age. | 2 | 32 | x |

| ND1 | Make water available both inside and outside. | 19 | 42 | x |

| NE1 | Teach children appropriate portion size by using plates, bowls and cups that are developmentally appropriate to their nutritional needs. | 0 | 0 | |

| NE2 | Require adults eating meals with children to eat items that meet nutrition standards. | 1 | 3 | |

| NF1 | Serve small-sized, age-appropriate portions. | 35 | 43 | x |

| NF2 | Permit children to have one or more additional servings of the nutritious foods that are low in fat, sugar, and sodium as needed to meet the caloric needs of the individual child; Teach children who require limited portions about portion size and monitor their portions. | 2 | 2 | |

| NG1 | Limit salt by avoiding salty foods such as chips and pretzels. | 1 | 3 | |

| NG2 | Avoid sugar, including concentrated sweets such as candy, sodas, sweetened drinks, fruit nectars, and flavored milk. | 1 | 1 | |

| NH1 | Do not force or bribe children to eat. | 4 | 6 | |

| NH2 | Do not use food as a reward or punishment. | 10 | 16 | |

Differences by state and region

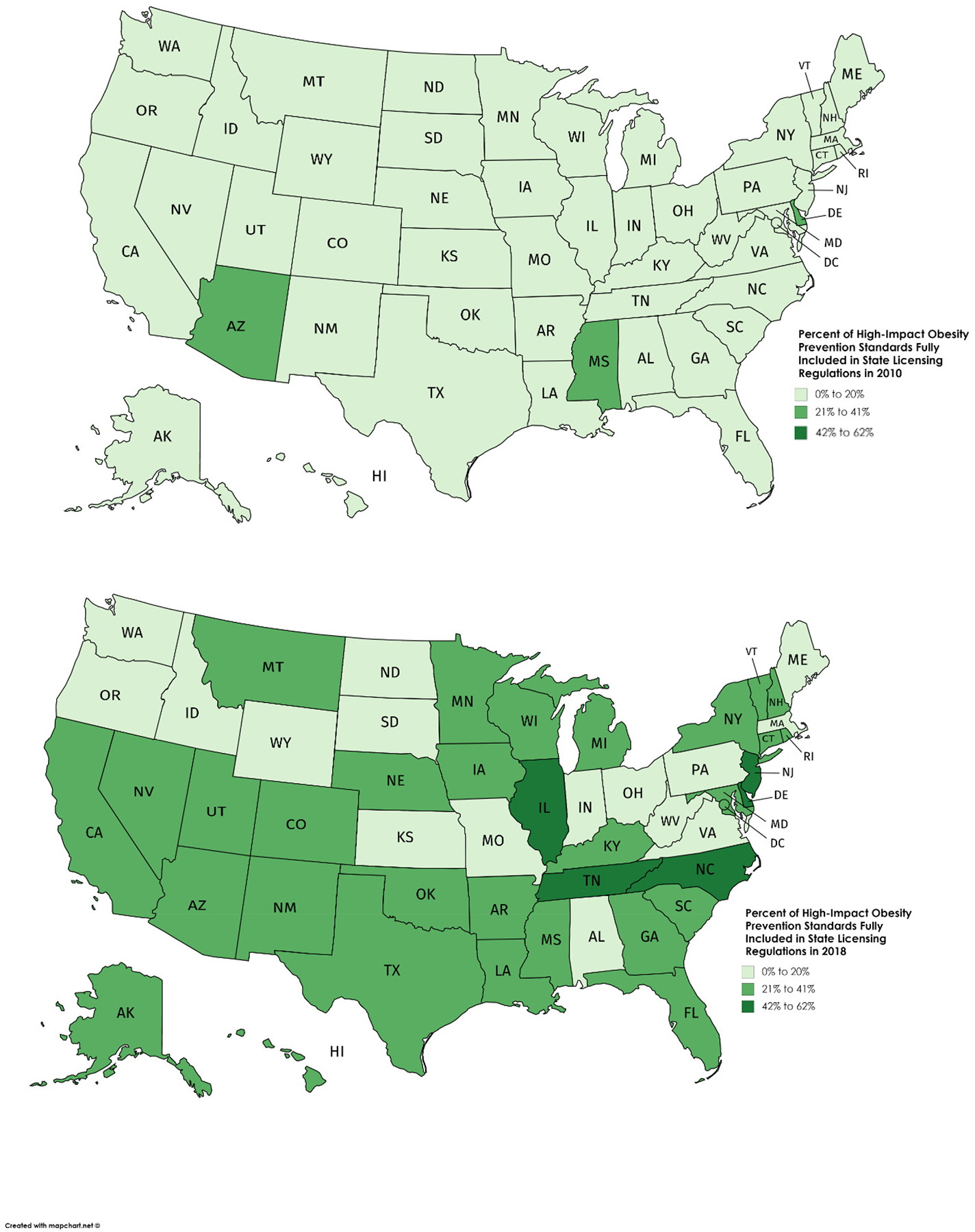

State and regional subgroup analyses reveal that a few states drove national improvements 2010 to 2018 by including more of the 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards in licensing regulations (Fig. 1). Despite overall progress, as of 2018, no state in the nation has fully adopted more than 24 of the 47 (51%) high-impact standards. Between 2010 and 2018, six states (Colorado, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Tennessee) and D.C. had a greater than 30%-point increase in the number of obesity prevention standards included in licensing regulations (Supplemental Table 1). New Jersey saw the largest improvement, as it included 23 of the 47 (49%) high-impact obesity prevention standards in 2018, compared to just one standard (2%) in 2010. As of 2018, Illinois included 24 of the 47 (51%) standards, the most any state includes in licensing requirements for Centers. In contrast, some made little or no progress during the nine-year period. Eight states (Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Wyoming) included the exact same number of standards in 2010 as they did in 2018, and Idaho is the only state in the nation that has not fully included any high-impact obesity prevention standards in licensing regulations. Regional analyses (data not shown) show that the mid-west region of the U.S. includes the least number of high-impact standards (23%) as of 2018, while the south includes the most (34%). For all years analyzed, the south consistently included the most high-impact obesity prevention standards in Center-based licensing regulations.

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of High-Impact Obesity Prevention Standards (n=47) Fully Included in State Licensing Regulations for Child Care Centers, 2010 vs. 2018

Differences in support of individual high-impact obesity prevention standards

To assess the most and least supported standards over time, Table 2 and Table 3 show differences in the number of states that fully adopted each of the 47 high-impact obesity prevention standards 2010 vs. 2018. A high-level summary by category is provided below.

Table 3.

Differences in Uptake of High-Impact Physical Activity and Screen Time Standard in Licensing Regulations for Child Care Centers 2010 vs. 2018

| Number of States Fully Including Standard in Licensing Regulations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2018 | ||

| Physical Activity Standards | |||

| PA1 | Provide children with adequate space for both inside and outside play. | 50 | 50 |

| PA2 | Provide orientation and annual training opportunities for caregivers/teachers to learn about age appropriate gross motor activities and games that promote children’s physical activity. | 0 | 0 |

| PA3 | Develop written policies on the promotion of physical activity and the removal of potential barriers to physical activity participation. | 1 | 0 |

| PA4 | Require caregivers/teachers to promote children’s active play and participate in children’s active games at times when they can safely do so. | 0 | 2 |

| PA5 | Do not withhold active play from children who misbehave. | 8 | 16 |

| PC1 | Provide daily for all children, birth to six years, two to three occasions of active play outdoors, weather permitting. | 5 | 8 |

| PC2 | Allow toddlers sixty to ninety minutes per eight-hour day for vigorous physical activity. | 0 | 9 |

| PC3 | Allow preschoolers ninety to one-hundred and twenty minutes per eight-hour day for vigorous physical activity. | 0 | 1 |

| PD1 | Provide daily for all children, birth to six years, two or more structured or caregiver/teacher/adult-led activities or games that promote movement over the course of the day—indoor or outdoor. | 2 | 2 |

| PE1 | Ensure that infants have supervised tummy time every day when they are awake. | 8 | 20 |

| Screen Time Standards | |||

| PB1 | Do not utilize media (television [TV], video, and DVD) viewing and computers with children younger than two years. | 3 | 14 |

| PB2 | Limit total media time for children two years and older to not more than 30 minutes once a week. Limit screen time (TV, DVD, computer time). | 0 | 0 |

| PB3 | Use screen media with children age two years and older only for educational purposes or physical activity. | 5 | 12 |

| PB4 | Do not utilize TV, video, or DVD viewing during meal or snack time. | 0 | 8 |

Infant Feeding:

Analyses show that several infant feeding standards were more often embedded in licensing requirements (Table 2). For example, in 2010, just two states had adopted regulations requiring introduction to solid foods occurs no sooner than 4 months of age (IC2), but preferably 6 months, but by 2018, 30 states included the standard. Additionally, ID3, which prohibits caregivers from serving fruit juice to children under 12 months of age, was not included in any state’s regulations in 2010, but by 2018, 29 states had fully included the restriction in licensing regulations. Presumably reflecting increasing calls from child health experts to reduce consumption of drinks with added sugars, even among our youngest children. The infant feeding standard most often included was IB1, feed infants on cue, with nearly 38 states fully embedding it in licensing requirements as of 2018.

Nutrition:

As of 2018, the high-impact nutrition standard most supported is, NF1, serve small sized, age appropriate portions at meal and snack times, with 43 states fully embedding it into licensing requirements. Several nutrition standards experienced rapid uptake into state licensing requirements, for example, standard NA5, which requires serving 1% pasteurized milk to children 2 years or older, was fully included in just two states’ licensing regulations in 2010, but by 2018, 36 states fully included it in regulations for Centers. Nutrition standards requiring child caregivers to offer juice only at meal times (NC2) and to limit daily servings of juice (NC3 and NC4) also saw increased support, with at least 30 states fully including the standards in regulations by 2018. Another notable increase was standard (NDI) require water to be made available to children both inside and outside which was included in 19 states’ licensing regulations in 2010, but by 2018, 42 states had fully adopted it. Six states banned the use of food as a reward or punishment (NH2) during this period; and standard NA2, serve lean meats and/or beans and avoid serving fried foods and NG2, avoid sugar, including concentrated sweets such as candy, sodas, sweetened drinks, fruit nectars, and flavored milk was included in just one state’s licensing regulations 2010 to 2018.

Physical Activity:

Overall, high-impact physical activity standards were least likely to be fully included in ECE licensing regulations, compared to infant feeding and nutrition standards (Table 3). However, PA1, licensed caregivers must provide children with adequate space for both inside and outside play, has been included in all but Idaho’s licensing requirements for Centers. Standard PE1, ensure infants have supervised tummy time every day when awake, saw additional uptake, with 12 additional states adopting the standard in regulatory requirements for licensure between 2010 and 2018. In 2010, no state had included PC2, allow toddlers 60–90 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day, but by 2018, nine states included the standard in licensing requirements. In contrast, the analogous physical activity standard for preschoolers (PC3, allow preschoolers ninety to one-hundred and twenty minutes per eight-hour day for vigorous physical activity) saw almost no uptake. Finally, standards related to providing trainings for child care caregivers on age-appropriate physical activity opportunities (PA2) and developing written policies on the promotion of physical activity and removal of barriers to participation (PA3) saw no uptake in state-based ECE licensing requirements.

Screen Time Standards:

From 2010–2018, eleven states embedded standard PB1 into regulatory requirements, prohibit media viewing and use of computers with children younger than two years old, and seven additional states required that ECE providers only use media for educational purposes when working with children at least two years of age (PB3). In 2010, no state had prohibited use of TV, videos, or DVDs during meal and snack time (PB4) but by 2018, eight states had embedded the standard into regulatory language. In contrast, as of 2018, no state included PB2, limit total media time for children two years and older to no more than 30 minutes once a week.

DISCUSSION

From 2010 to 2018, the proportion of high-impact obesity prevention standards fully embedded in licensing regulations for Centers doubled, from approximately 13% in 2010 to 29% in 2018. Across all years, licensing regulations for Centers consistently included more high-impact standards, followed by Large Care Homes and Small Care Homes, respectively. Given the discrepancy in uptake among the care types, case studies and informative interviews may help identify factors associated with inclusion of the standards. For example, some states choose to combine licensing regulations for different care types into a single regulatory package, thus, reducing administrative barriers and ensuring equitable application of high-impact standards across care types. In Tennessee, licensing officials streamlined their regulatory rule and revision package, combining requirements for all three licensed care types. Through simultaneous updates to regulations, and ongoing consultation with the Department of Public Health, Tennessee included the most high-impact standards (23 out of 47 standards or 49%) in licensed Centers and home-based child care programs in 2018, impacting over 4,000 licensed providers in the state21. Even with overall national improvements, nine states saw no additional uptake of the high-impact standards 2010–2018. Further investigation into the factors behind the lack of uptake may highlight challenges faced by states, such as, infrequency of the regulatory revision process or a lack of expertise on childhood obesity as a serious medical condition14.

Physical activity standards were least likely to be fully included in state licensing regulations in 2010 and 2018 (Table 3). Our study found that physical activity standards with the lowest uptake require ECE providers to develop written policies and practices for physical activity (PA3), as well as related child-based physical activity training for staff (PA2). Young children’s level of moderate to vigorous physical activity has been positively associated with ECE regulations requiring at least 60 minutes of physical activity per day and dedicated outdoor play space21. Thus, ECE licensing regulations requiring dedicated time, space, and infrastructure potentially hold significant promise for increasing physical activity levels among young children.

CACFP Requirements in Child Care Licensing Regulations

On average, increases in the number of obesity prevention standards included in state licensing regulations averaged 1% to 2% per year. This trend was consistent for all years and all care types analyzed, except 2016–2017. During this one-year period, there was a 7%-point increase in high-impact obesity prevention standards fully included in state licensing regulations for Centers, Large Family Care Homes, and Small Family Care Homes. This sharp increase may have been the result of federal updates to the CACFP meal pattern requirements that occurred 201722. In that year, NRC identified 23 states as requiring licensed ECE providers to adhere to CACFP infant feeding and nutrition standards, regardless of program participation or reimbursement23. As such, these states received improved ratings for fully meeting 13 high-impact infant feeding and nutrition standards, which also align with the 2017 CACFP updated meal pattern. This finding illustrates how federal nutrition standards may inform state-level ECE licensing regulations. Because CACFP meal pattern standards undergo regular revision they represent an “evergreen” standard, by which states can set minimum requirements. This can help improve diet quality not only for children from lower income households, but all children enrolled in licensed ECE programs.

Strengths of this study include consistent data from all 50 states and D.C. from 2010 to 2018; the standardized collection and review procedures of state-level ECE licensing regulations; and the use of a sensitive rating scale to describe differences in comprehensiveness of state licensing regulations. This study also had several limitations. First, only Center-level licensing regulations were analyzed for state, regional, and individual standard analyses. Second, the study focused on regulations that were fully aligned (rated as ‘4’) with high-impact obesity prevention standards to describe national trends. It is possible that states made incremental improvements during this period, which were not captured. And finally, this study cannot account for actual implementation of obesity prevention standards included in licensing regulations. Although it is probable that ECE providers are aware of their state’s licensing regulations, as they are requirements for legal operation, it is also possible that implementation barriers exist. For example, child care providers may lack access to the resources and technical assistance needed to train their staff on healthy infant feeding practices, nutritious meal and snack preparation, and age appropriate physical activity. Future studies should seek to identify common barriers to facility-level implementation and identify possible supports.

CONCLUSION

This study offers evidence that states are taking steps towards early intervention for childhood health and prevention of childhood obesity. Early childhood represents an important window of opportunity, before the significant costs associated with adult obesity are realized. States have consistently included more obesity prevention standards in ECE regulations over time. Even so, there remains room for improvement, particularly among small family child care programs, as well as uptake of regulations supporting physical activity in ECE. In conclusion, these science-based policy trends represent a bright spot for national efforts to combat childhood obesity and highlight the need to further support ECE providers and address implementation barriers.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support:

No competing financial interest exists.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.QuickStats. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Persons Aged 2–19 Years — National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000 through 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:390. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016. Data Brief, No. 288 National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fakhouri TH, et al. Prevalence of obesity among youths by household income and education level of head of household—United States 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2018;67(6), 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannon TS, Rao G, & Arslanian SA Childhood obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pediatrics, 2005;116(2), 473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedeman C, Heneghan C, Mahtani K, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in healthy children and its association with body mass index: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 2012; 345:e4759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck AR Psychosocial aspects of obesity. NASN Sch Nurse, 2016;31(1), 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biro FM, & Wien M Childhood obesity and adult morbidities Am J Clin Nutr, 2010;91(5), 1499S–1505S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanck HM, & Collins J CDC’s winnable battles: Improved nutrition, physical activity, and decreased obesity. Child Obes, 2013;9(6), 469–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2005. 10.17226/11015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gortmaker SL, Long MW, Resch SC et al. Cost effectiveness of childhood obesity interventions: evidence and methods for CHOICES. Am J Prev Med, 2015;49(1), 102–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laughlin L Who’s minding the kids? Child care arrangements: Spring 2011. Current Population Reports P70–135. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds MA, Cotwright CJ, Polhamus B et al. Obesity prevention in the early care and education setting: Successful initiatives across a spectrum of opportunities. J Law Med Ethics, 2013;41(2), 8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larson N, Ward DS, Neelon SB, et al. What role can child-care settings play in obesity prevention? A review of the evidence and call for research efforts. J Acad Nutr Diet 2011; 111(9), 1343–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, Administration for Children and Families. Developing and Revising Child Care Licensing Requirements. Fairfax VA, 2017. Retrieved from: https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/resource/developing-and-revising-child-care-licensing-requirements [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maxwell KL, & Starr R The Role of Licensing in Supporting Quality Practices in Early Care and Education. Research Brief #201931. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, D.C., 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs, 4th ed. Itasca, IL. American Academy of Pediatrics. (2019). Retrieved from: https://nrckids.org/CFOC [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Public Health Association, and National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. 2012. Preventing Childhood Obesity in Early Care and Education: Selected Standards from Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards; Guidelines for Early Care and Education Programs, 3rd Edition. Retrieved from: https://nrckids.org/CFOC/Childhood_Obesity [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education, University of Colorado Denver. 2011. National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education: Achieving a State of Healthy Weight: A National Assessment of Obesity Prevention Terminology in Child Care Regulations 2010. Aurora, CO. Retrieved from https://nrckids.org/HealthyWeight/Archives [Google Scholar]

- 19.United States Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau, Retrieved from: https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf visited on 4/30/2020.

- 20.United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Child and Adult Care Food Program. Retrieved: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cacfp visited on 4/30/2020

- 21.Stephens RL, Xu Y, Lesesne CA et al. Peer reviewed: Relationship between child care centers’ compliance with physical activity regulations and children’s physical activity, New York City, 2010, Prev Chronic Dis, 2014; 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Food and Nutrition Service, USDA. (2016). Child and Adult Care Food Program: Meal pattern revisions related to the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Federal Register. Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/04/25/2016-09412/child-and-adult-care-food-program-meal-pattern-revisions-related-to-the-healthy-hunger-free-kids-act [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Resource Center for Health and Safety in Child Care and Early Education. (2019). Achieving a state of healthy weight 2018 report. Aurora, CO: University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Retrieved from https://nrckids.org/HealthyWeight [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.