Abstract

The histidine-containing peptide L5C (PAWRHAFHWAWHMLHKAA) is a histidine-rich lytic peptide. Interactions of some divalent metal ions with peptide L5C and their effects on the cell lysis activity of the peptide were studied. The presence of Cu2+ caused a secondary structure change (from random coil to α-helix) which resulted in the loss of cell lysis activity in peptide L5C. Binding of Zn2+ to peptide L5C also reduced the lytic activity of the peptide but Zn2+ did not affect the secondary structure of the peptides. Instead, Zn2+ induced peptide L5C aggregation. Unlike Zn2+ and Cu2+, Mg2+ had no significant effect on the activity of peptide L5C. Further experiments revealed that formed ion-peptide L5C complexes were sensitive to pH and dissociated in acidic solutions. Peptide L5C demonstrated improved pH-selectivity in the presence of trace amount of Zn2+. This property of histidine-containing lytic peptides can be used to improve their therapeutic effectiveness in the treatment of cancers.

Keywords: Peptide, metal ions, histidine-rich, pH-selectivity, cancer treatment

INTRODUCTION

Because the imidozle group in histidine has a pKa of approximately 6.0, histidine is an acidic amino acid under acidic conditions when the environmental pH is lower than 6.0. Depending on the sequences and structures, some histidine-containing bioactive peptides may show pH-dependent activity (Chen et al 2012a, 2012b; Kharidia et al, 2010; Tu et al., 2009a). In our recent research, we have developed a general approach to construct pH-sensitive peptides by selectively replacing the cationic residues in the peptides with histidines (Tu et al., 2009b). The newly constructed histidine-containing peptides demonstrate 2–20 times increased activity under acidic pH in comparison with that at physiological conditions. Because the pHs at some disease locations, such as tumors and bacterial infections, are consistently lower than the surrounding tissues, these histidine-containing pH-sensitive peptides are potential therapeutics for disease treatments.

We know that peptides can chelate metal ions (Sundberg and Martin, 1974) using amine and carboxyl groups. Binding of peptides to metal ions, especially several transition metal ions such as Cu2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Cd2+ (Morgan, 1981; Bryce et al., 1966; Brewer and Lajoie, 2000) lead to changes in both structure (Ruan et al., 1990) and activity (Brewer and Lajoie, 2000, Dashper et al., 2005). Because of the presence of imidozle groups, histidine-containing peptides prove to be excellent chelating agents for divalent metal ions: Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Zn2+ induce self-assembly in histidine-containing peptides with specific sequences into triple-stranded α-helical bundle (Suzuki et al., 1998); a small histidine-containing peptide (Gly-Gly-His) with high affinity to copper ions can be used as a chemosensor for Cu2+ detection (Torrado et al., 1998).

In this research, we studied the ion chelating ability of a histidine-containing pH-sensitive peptide (L5C, PAWRHAFHWAWHMLHKAA) derived from a lytic peptide L5 (PAWRKAFRWAWRMLKKAA) (Tu et al., 2009b). Effects of metal ions on the activity and pH-selectivity of the peptide L5C were also tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

L5C (PAWRHAFHWAWHMLHKAA) was purchased from GeneScript Inc. (Piscataway, NJ). All other reagents, if not mentioned, were obtained from Sigma Chemical Laboratory (St Louis, MO).

Cell Culture

CHO-K1 (Chinese hamster ovary) cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The cells were grown in F12K medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Cytotoxicity Assay

Freshly trypsinized CHO-K1 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a concentration of 5000 cells/well. The cells were cultured at 37 °C overnight to form a monolayer. The peptide L5C and metal ions were premixed for 15 minutes to form a stable interaction before they were applied to the cells. After the medium was removed, the cells were washed with PBS, and then incubated with the peptide L5C or the mixtures of L5C with metal ions for 60 minutes. 10 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL) were then added into each well. Cell viability was determined after four hours of incubation by dissolving crystallized MTT with 10% SDS solution containing 5% isopropanol and 0.1% HCl and measuring absorbance at 570 nm.

To prove the accumulation of Cu2+ by L5C on the cell membrane, varied concentrations of ascorbic acid (AA) were added for another 30 minutes of incubation after the cells were treated with the mixture of L5C and Cu2+. The cell viability was determined using the MTT method described above.

Quenching of the Intrinsic Fluorescence of L5C by Metal Ions

The peptide L5C was prepared in PBS with a fixed concentration of 40 μM. The metal ion stock solutions were added to make the final concentrations of metal ions in the range of 0–200 μM. The fluorescence intensity of the peptide was recorded with a Biotech Synergy Mx microplate reader, setting the excitation and emission wavelengths at 280 nm and 350 nm, respectively (Stöckel et al., 1998; Garzon-Rodriguez et al., 1999).

Acquisition of Peptide Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectra

The CD spectra of L5C, in the absence and presence of metal ions, were recorded on a Jasco J-710 spectropolarimeter (Tu et al., 2009b). The CD spectra were scanned at 25 °C in a capped, quartz optical cell with a 1.0 mm path length. Data were collected from 240 to 190 nm at an interval of 1.0 nm with an integration time of two seconds at each wavelength. Five scans were averaged, smoothed, background-subtracted, and converted to mean residue molar ellipticity [θ] (degrees cm2 dmol–1) for each measurement. CDPRO software was used to analyze the data obtained from the CD spectropolarimeter.

Estimation of Peptide Aggregation

The formation of the peptide aggregation induced by metal ions in solution was estimated using a fluorescent probe 1-anilinonaphthalene-8-sulfonic acid (1, 8-ANS) (Henriques et al., 2008; Bertsch et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2012b). The emission spectrum of 1, 8-ANS (20 μM) was recorded with a Biotech Synergy Mx microplate reader by setting excitation wavelength at 369 nm.

Particle Size Measurement

Peptides from stock solutions (5 mM in water) were diluted with PBS. Freshly prepared peptide solutions were subjected to a brief (60 s) sonication treatment. The particle sizes of the peptide solutions were measured immediately after sonication using a zeta nanosizer.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Peptide L5C Interaction with Divalent Metal Ions

The interactions of peptide L5C with three divalent metal ions Cu2+, Zn2+, and Mg2+ were studied through an established fluorescence quenching experiment (Stöckel et al., 1998; Garzon-Rodriguez et al., 1999). Copper ions caused a sharp decrease in the intrinsic fluorescence of L5C. There was an optimal peptide to metal ion ratio at 1:1 in this Cu2+-induced fluorescence intensity decrease of peptide L5C. Unlike the case of Cu2+, the intrinsic fluorescence of L5C decreased gradually as the concentration of Zn2+ increased, suggesting that the interaction of peptide L5C with Zn2+ was more complicated than that with Cu2+. Magnesium ions had no effect on the intrinsic fluorescence of L5C even at high concentrations (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

The interaction of peptide L5C with metal ions. (a) Quenching of the L5C intrinsic fluorescence by metal ions. The concentration of L5C was fixed to 40μM. (b) CD spectra of L5C in the absence or presence of metal ions in 20 mM NaAc. (c) CD spectra of L5C in the absence or presence of metal ions in 10 mM SDS. CD spectra were converted to mean residue molar ellipticity [θ] (degrees cm2 dmol−1) for each measurement.

The effects of metal ions on the secondary structure of peptide L5C were examined using CD spectra. The peptide existed as random coils in the aqueous solution but adopted an α-helix structure in the hydrophobic solution, an environment similar to the lipid bilayer (Fig. 1b & 1c). Zn2+ and Mg2+ ions had limited effects on the secondary structure of L5C. However, Cu2+ induced a dramatic L5C structure change, from random coil to α-helix (Fig. 1b) in aqueous solution as estimated using CDpro program. It should be noted that the dramatic increase of the CD spectrum intensity at 230–240 nm indicated the formation of peptide aggregation as we reported previously (Tu et al., 2007).

We know that the i + 4 → i hydrogen bonding is the most prominent characteristic of an α-helix in which the N-H group of an amino acid forms a hydrogen bond with the C-O group of the amino acid four residues earlier. It was reported that copper ions could act as cross-linkers to stabilize the folded form of peptides if the residues at i and i + 4 positions served as ligands (Ruan et al., 1990). The two histidine residues at positions #8 and #12, and the lysine residue at position #16 in peptide L5C are all ligands of copper ions. Therefore, copper ions might increase the helix contents of peptide L5C by stabilizing the hydrogen bonding among these residues.

On the other hand, the metal ions had limited effects on the secondary structures of L5C in a hydrophobic environment (Fig. 1c).

Effects of Metal Ions on the Cell Lysis Activity of Peptide L5C

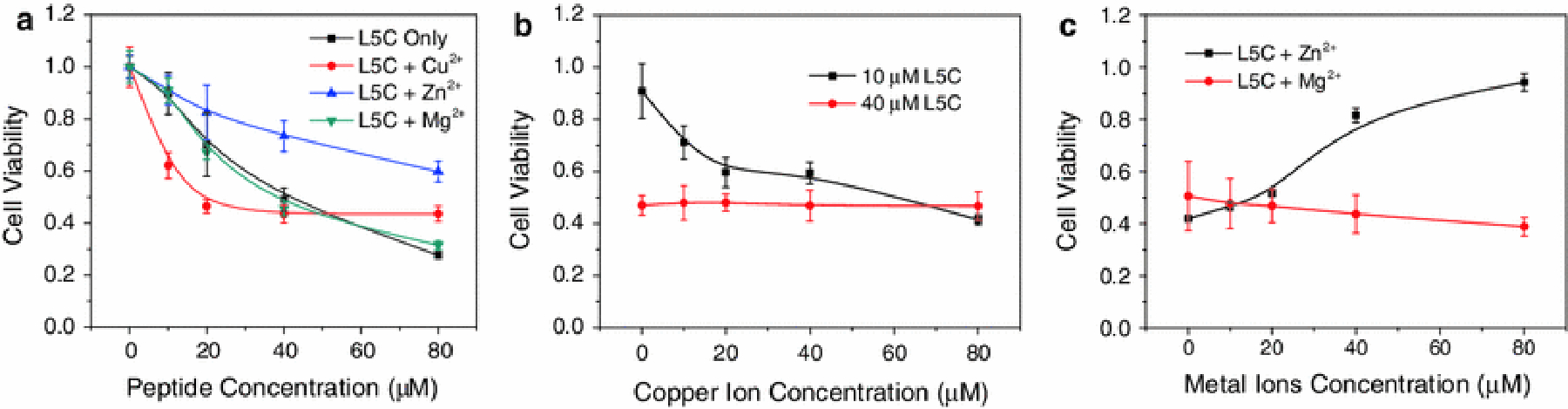

In agreement with the results from the peptide intrinsic fluorescence quenching study, metal ions Cu2+ and Zn2+ affected the activity of L5C peptide. The effect of Cu2+ was peptide concentration dependent (Fig. 2a). At low peptide concentration (<40 μM), the activity of L5C was dramatically increased as the concentrations of Cu2+ in solution were increased in the range of 0–80 μM. However, when high concentrations of peptide (>40 μM) were used, the effects of Cu2+ became negligible (Fig.2a & 2b). Unlike Cu2+, Zn2+ had a negative effect on the cell lysis activity of peptide L5C in a wide peptide concentration range (Fig. 2a). Conversely, when a fixed concentration of L5C (40 μM) was used, increased Zn2+ concentrations were associated with dramatically decreased peptide activity (Fig. 2c). In addition, Mg2+ had little influence on the activity of L5C as there was no interaction between them.

Fig. 2.

The effects of metal ions on the activity of peptide L5C. (a) The concentration-dependent activity of L5C in the presence of 40 μM metal ions. (b) The effects of Cu2+ on the activity of L5C at low (10 μM) and high (40 μM) peptide concentrations. (c) The effects of Zn2+ and Mg2+ on the activity of L5C. The cell variability was measured by MTT assay. Data represents the mean and SD of three independent tests.

It has been proved that the interaction of random coil peptide with cell membrane consists of two consecutive steps with negative free energies (Wilson et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2012a). Compared to random coils, α-helix is not an energetically favorable structure. In this regard, peptide L5C in complex with Cu2+ should have reduced cell lysis activity. However, Cu2+ showed peptide-concentration-dependent effects on the activity of L5C: the cell lysis activity of low concentration L5C was dramatically increased by Cu2+, while that of high concentration L5C was barely affected.

To understand the synergetic effects of Cu2+, we tested the cytotoxicity of Cu2+ by supplying the cell culture medium with ascorbic acid (AA), a strong reducing agent which reduces Cu2+ to produce free radicals (Kadiiska and Mason, 2002). As shown in Fig. 3, neither low concentration of peptide L5C nor copper ions were cytotoxic when they were supplied along with ascorbic acid. However, if low concentrations of L5C and copper ions were supplied together with ascorbic acid, dramatic increased cell lysis was observed. We know that only free radicals generated at close proximity to cell surfaces can cause effective cell membrane damage. Ascorbic acid enhanced cell lysis activity of L5C in the presence of Cu2+, indicating that significant amounts of Cu2+ ions were accumulated at the cell surfaces as the result of formation of stable L5C-Cu2+ complexes.

Fig. 3.

The effects of ascorbic acid on the cytotoxicity of peptide L5C in the absence or presence of Cu2+ tested on CHO-K1 cells. Data represents the mean and SD of three independent tests.

We have found in our previous study (Chen et al, 2012a, 2012b) that many peptides can form aggregates as the peptide solution concentrations increase. Peptide L5C also demonstrated concentration-dependent aggregation. Gradually increased solution particle sizes were observed as the L5C concentration in solutions was increased from 10 μM to 80 μM (Fig. 4). Because peptides in peptide aggregates may adopt different secondary structure and have distinct chemical/physical properties from that of single peptide, L5C aggregates will interact with copper ions differently. In this regard, a reasonable explanation of the concentration-dependent effects on cell lysis activity of peptide L5C in the presence of Cu2+ (Fig. 2b) might be that only single molecule but not aggregated L5C can interact with Cu2+ to form stable L5C-Cu2+ complexes with dramatically increased cell lysis activity.

Fig. 4.

Measured particle sizes of peptide L5C of various concentrations in PBS solutions. Data represents the mean and SD of three independent tests.

It was interesting to note that although Zn2+ had very limited or negligible effects on the secondary structure of L5C (Fig. 1), the effects of Zn2+ on the cell lysis activity of L5C was dramatic. Significant decrease in peptide activity was found in the presence of Zn2+ (Fig. 2a & 2c). To understand the acting mechanism of Zn2+, 1, 8-ANS was used to study the L5C aggregation in the solution. Fig. 5 shows that Zn2+, but not Cu2+ or Mg2+, caused fluorescence intensity increase of 1, 8-ANS in the presence of peptide L5C, indicating the formation of L5C aggregates in the Zn2+-containining solution. We have found that the self-assembling of peptides into aggregates have a dramatically negative impacts on the activity of lytic peptides (Chen et al., 2012a), explaining reduced activity of L5C in the presence of Zn2+.

Fig. 5.

Peptide aggregation induced by metal ions. The aggregation of L5C was detected by the emission spectra change of 1, 8-ANS. The concentrations of peptide L5C and metal ions were 40μM.

Effects of Zn2+ on the pH-selectivity of Peptide L5C

Like other histidine-containing lytic peptides, peptide L5C also showed pH-dependent activity. Although zinc ions had negative effects on the activity of peptide L5C under physiological conditions, the effect of Zn2+ at acidic pH was negligible (Table 1). As a result, peptide L5C in the presence of Zn2+, or peptide L5C-Zn2+ complexes, showed improved pH-selectivity.

Table 1.

Comparison of activity and pH-selectivity of peptide L5C in the absence and presence of zinc ions

| IC50 (μM) | pH selectivity* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH=7.4 | pH=5.5 | ||

| In the absence of zinc | 38.4 ± 3.2 | 6.5 ± 0.9 | 5.9 |

| In the presence of zinc | 166.3 ± 12.5 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 27.7 |

IC50 ratio at pH=7.4 and pH=5.5 (IC50 at pH=7.4/IC50 at pH=5.5).

We tested the pH-affected interactions between peptide L5C and Zn2+, and found that L5C-Zn2+ complexes were unstable under acidic pHs, as L5C-Zn2+ complexes were completely disassociated when the solution pH was below 6.0. In addition, the Zn2+-induced peptide aggregation at pH=7.4 disappeared at acidic pHs (Fig. 6). These pH-dependent complexations of peptide L5C with Zn2+ explain the enlarged pH-selectivity of L5C peptide in the presence of Zn2+.

Fig. 6.

(a) Zinc ions induced peptide intrinsic fluorescence quenching at varied pHs. (b) Peptide aggregation induced by zinc ions at pH=5.5. The concentration of peptide L5C was fixed to 40μM.

It has been proven that the extracellular pHs in some solid tumors are consistently lower as compared to the pH (7.2–7.4) in normal tissues or organs. The average pH in solid tumors ranges from 6.0 to 7.0, which is caused by the chaotic nature of tumor vasculature and increased glycolytic flux in tumor cells (Engin et al., 1995). As the presence of zinc ions increases the pH-selectivity of the peptide L5C dramatically (Table. 1), this metal-ion-improved pH-selectivity of histidine-containing peptides are expected to have wide applications in improving the therapeutic effectiveness of peptides for cancer treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant GM081874. Mr. Chen is a recipient of the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Doctoral Fellowship.

REFERENCES

- Brewer D and Lajoie G: 2000, Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 14, 1736–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch M, Mayburd AL and Kassner RJ: 2003, Anal. Biochem 313, 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Tu Z, Voloshchuk N and Liang JF: 2012a, J. Pharm. Sci 101, 1509–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Patrone N and Liang JF: 2012b, Biomacromolecules. 13, 3327–3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashper SG, O’Brien-Simpson NM, Cross KJ, Paolini RA, Hoffmann B, Catmull DV, Malkoski M and Reynolds EC: 2005, Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother 49, 2322–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin K, Leeper DB, Cater JR, Thistlethwaite AJ, Tupchong L and McFarlane JD: 1995, Int J Hyperthermia. 11, 211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon-Rodriguez W, Yatsimirsky AK and Glabe CG: 1999, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 9, 2243–2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques ST, Pattenden LK, Aguilar MI and Castanho MA: 2008, Biophys. J 95, 1877–1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiiska MB and Mason RP: 2002, Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 58, 1227–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharidia R, Tu Z, Chen L and Liang JF: 2010, Arch Microbiol. 194, 579–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan WT: 1981, Biochemistry. 20, 1054–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan F, Chen Y and Hopkins PB: 1990, J. Am. Chem. Soc 112, 9403–9404. [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg RJ and Martin RB: 1974, Chem. Rev 74, 471–517. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Hiroaki H, Kohda D, Nakamura H and Tanaka T: 1998, J. Am. Chem. Soc 120, 13008–13015. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckel J, Safar J, Wallace AC, Cohen FE and Prusiner SB: 1998, Biochemistry, 37, 7185–7193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Hao J, Kharidia R, Meng XG, Liang JF: 2007, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 361, 712–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Young A, Murphy C and Liang JF: 2009a, J. Pept. Res 15, 790–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Volk M, Shah K, Clerkin K and Liang JF: 2009b, Peptides. 30, 1523–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrado A, Walkup GK and Imperiali B: 1998, J. Am. Chem. Soc 120, 609–610. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WW, Wade MM, Holman SC and Champlin FR: 2001, J. Microbiol. Meth 43, 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]