Abstract

Intravital microscopy (IVM) enables visualization of cell movement, division, and death at single-cell resolution. IVM through surgically inserted imaging windows is particularly powerful because it allows longitudinal observation of the same tissue over days to weeks. Typical imaging windows comprise a glass coverslip in a biocompatible metal frame sutured to the mouse’s skin. These windows can interfere with the free movement of the mice, elicit a strong inflammatory response, and fail due to broken glass or torn sutures, any of which may necessitate euthanasia. To address these issues, windows for long-term abdominal organ and mammary gland imaging were developed from a thin film of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), an optically clear silicone polymer previously used for cranial imaging windows. These windows can be glued directly to the tissues, reducing the time needed for insertion. PDMS is flexible, contributing to its durability in mice overtime—at least a month in our hands. Longitudinal imaging is imaging of the same tissue region during separate sessions. A stainless-steel grid was embedded within the windows to localize the same region, allows visualization of dynamic processes (like mammary gland involution) at the same locations, days apart. Single disseminated cancer cells in the liver were also visualized developing into micro-metastases over time. The silicone windows used in this study are simpler to insert than metal-framed glass windows and cause limited inflammation of the imaged tissues. Moreover, embedded grids allow for straightforward tracking of the same tissue region in repeated imaging sessions.

Keywords: Longitudinal intravital imaging, pancreas, liver, mammary gland, polydimethylsiloxane, imaging window

SUMMARY:

An approach is presented to perform long-term intravital imaging using optically clear, silicone windows that can be glued directly to the tissue/organ of interest and the skin. These windows are cheaper and more versatile than others currently used in the field, and the surgical insertion causes limited inflammation and distress to the animals.

INTRODUCTION:

Intravital microscopy (IVM), the imaging of tissues in anesthetized animals, offers insights into the dynamics of physiological and pathological events at cellular resolution in intact tissues. The applications of this technique vary widely, but IVM has been instrumental in the cancer biology field to help elucidate how cancer cells invade tissues and metastasize, interact with the surrounding microenvironment, and respond to drugs1–3. In addition, IVM has been key to advancing our understanding of the complex mechanisms governing immune responses by providing insights complementary to ex vivo profiling approaches (e.g., flow cytometry). For instance, intravital imaging experiments have revealed details about immune functions as they relate to cell migration and cell-cell contacts and have offered a platform to quantitate spatiotemporal dynamics in response to injury or infection4–7. Many of these processes can also be studied through histological staining, but only IVM allows the tracking of dynamic changes. In fact, whereas a histological section offers a snapshot of the tissue at a given time, intravital imaging can track intercellular and subcellular events within the same tissue over time. In particular, progress in fluorescence labeling and the development of molecular reporters have allowed molecular events to be correlated with cellular behaviors, such as proliferation, death, motility, and interaction with other cells or the extracellular matrix. Most IVM techniques are based on fluorescence microscopy, which due to light scattering, makes imaging deeper tissues challenging. The tissue of interest, therefore, often needs to be surgically exposed with an often invasive and terminal procedure. Thus, depending on the organ site, the tissue can be imaged continuously for a period varying from a few to 40 h8. Alternatively, the surgical insertion of a permanent imaging window permits the imaging of the same tissue sequentially over a period of days to weeks7,9.

The development of new imaging windows has been highlighted as a technological need to further improve intravital imaging approaches10. The prototypical intravital imaging window is a metal ring containing a glass coverslip secured to the skin with sutures11. Interference with free movement, the accumulation of exudate, and damage to the glass coverslip are common problems seen with using such windows. Moreover, the prototypical window requires specialized production, and the surgical procedure can require extensive training. To address these issues, windows for abdominal organ and mammary gland imaging were developed from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a silicone polymer, which has previously been used in cranial windows for long-term imaging in the brain12,. Here, a detailed method for generating and surgically inserting PDMS-based silicone windows, including how to cast the window around a stainless-steel grid to provide landmarks for repeated imaging of the same tissue regions, is presented. Furthermore, it is described how to insert the window over abdominal organs or the mammary gland using a simple, stitch-free procedure. This new approach overcomes some of the most common issues with currently used imaging windows and increases the accessibility of longitudinal intravital imaging.

PROTOCOL:

All procedures described were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations for the use of vertebrate animals, including prior approval by the CSHL Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

1. Casting the silicone window

1.1 Prepare the silicone polymer (PDMS) by mixing the base elastomer and curing agent in a 10:1 (v/v) ratio.

1.2 Cast a window by depositing a small quantity of PDMS on a sterile, smooth surface and adjust the volume-to-area ratio to the desired thickness.

Note: Using 200 mg of polymer solution for a 22 mm diameter circle on the lid of a 24 well-plate lid results in a good compromise between window sturdiness and optical clarity.

1.3 Optional: To provide landmarks for repeated imaging of the same tissue regions, lightly press a stainless-steel grid into the silicone after the PDMS is on the desired casting surface.

1.4 To remove air bubbles, place the coated surface in a vacuum desiccator for 45 min to degas the polymer.

1.5 Cure the silicone windows in an oven at 80 °C for 45 min.

1.6 Score the polymer at the edges of the mold and gently peel the cured windows from the surface used for casting with forceps.

1.7 Before surgery, sterilize the windows by autoclaving.

2. Preparing the mouse for insertion of the silicone window

2.1 Anesthetize the mouse in an induction chamber using 4% (v/v) isoflurane. Move the mouse to a warming pad on the surgical table, place the mouse in the anesthesia nose mask, and lower the isoflurane concentration to 2% for maintenance throughout the surgery.

2.2 Check the depth of anesthesia by pinching the toes of the hind limbs. Do not proceed until the mouse is inactive and does not show toe pinch reflex response.

2.3 Apply ophthalmic lubricant to the eyes to keep them from drying and preventing trauma.

2.4 Administer pre-emptive analgesia (buprenorphine 0.05 mg/kg) subcutaneously.

2.5 Shave the surgical site and completely remove the hair with a hair removal cream.

2.6 Apply povidone-iodine solution (10% v/v) and ethanol (70% v/v) consecutively 3x to prevent the surgical site infection.

3. Inserting a ventral window for imaging in the liver; adaptable for other abdominal organs (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Surgical insertion of a ventral abdominal imaging window over the liver.

(A) The cartoon shows the anatomical location of structures relevant to the surgery. The white dashed box outlines the surgical field viewed in the pictures. (B) An incision is made starting 3 mm below the xiphoid process and continuing down so that a 1–1.5 cm2 section of skin is removed along the midline. (C) A slightly smaller section of the peritoneum is dissected. (D) The falciform ligament (white arrowhead) is severed, pushing the liver down. Note: cotton swabs moistened with sterile saline are used to gently manipulate internal organs. (E) Using a syringe, a small amount of surgical adhesive is applied in droplets around the area of interest on the surface of the liver. (F) The window is positioned and held firmly against the liver until the adhesive has dried (2 min). (G) The edges of the window are folded under the peritoneum and skin. (H) To secure the window to the peritoneum, adhesive is applied on the surface of the window corresponding to the shaded area, before pushing the peritoneum down on it and gluing it in place. The skin is similarly glued onto the peritoneum. A rim of glue is finally deposited along the red line to prevent growth of the epithelium over the window. (I) Same image as in (H) without the markings showing the mouse ready for post-surgical recovery. Area outlined with dashed lines is magnified in (J, K). (J) Marks from the droplets of adhesive are visible on the surface of the liver (arrow heads) (K) Same photo as in J showing the liver visible through the window outlined by a white dashed line. The droplets of adhesive on the liver surface are outlined in red. The area to be imaged is outlined in white.

3.1 Place the mouse in the supine position.

3.2 Make a 10 mm incision starting 3 mm down from the xiphoid process using sterile scissors and forceps.

3.3 Remove a 1–1.5 cm2 section of skin along the midline.

3.4 Use a second pair of sterile scissors and forceps to remove a section of the peritoneum slightly smaller than the section of skin.

3.5 Optional: To visualize a larger portion of the liver, use cotton swabs moistened with sterile saline to push the liver down from the diaphragm revealing the falciform ligament connecting the liver to the diaphragm. Sever the ligament taking care not to cut the inferior vena cava.

3.6 Withdraw surgical adhesive with a 31 G syringe, apply a small quantity of it on the surface of the liver around the edges of the area to be imaged. This adhesive creates a circular seal, leaving the center area intact for imaging.

CAUTION: Limit the adhesive to small droplets forming a circular pattern around the imaging area. Tissue immediately in contact with the adhesive cannot be imaged. It is not necessary to dry the tissue before applying the adhesive.

NOTE: Any cyanoacrylate-based adhesives can be used successfully for this procedure. Surgical adhesive ensures sterility. For terminal procedures, all-purpose super glues yield good results.

3.7 Position the window using forceps and hold it firmly against the liver until the adhesive has dried (~2 min).

3.8 Fold the edges of the window under the peritoneum.

3.9 With a syringe, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the edges of the window that are now under the peritoneum. Push down on the peritoneum with forceps to secure it to the window.

3.10 Similarly, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the peritoneum and push it down on the skin with forceps to seal them.

NOTE: If performed correctly, a circular area of liver tissue should now be visible through the window.

3.11 Apply glue around the edges of the window to create a rim that will help prevent the skin from growing back over the window.

CAUTION: If the procedure is carried out using sterile surgical techniques and the window is sterilized before insertion, sealing the wound with surgical adhesive is sufficient to avoid infections. However, failure to follow proper aseptic techniques during surgical insertion or imperfect closure can lead to overt or subclinical infection and drying out of the tissue.

4. Inserting a lateral window for imaging in the liver; compatible with the concurrent injection of cancer cells in the portal vein (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Surgical insertion of a window over the right lobe of the liver.

(A) The cartoon shows the anatomical location of structures relevant to the surgery. The black dashed box outlines the surgical field viewed in the pictures. (B) The mouse is placed in the left lateral decubitus position, an incision is made starting 3 mm below the rib cage, and an approximately 1 cm2 section of skin is removed. (C) A slightly smaller section of the peritoneum is dissected. (D) The liver is gently pulled down below the rib cage using a moistened cotton swab. (E) Using a syringe, a small quantity of surgical adhesive is applied in droplets (white arrow head) on the surface of the liver. (F) The window is positioned and held firmly against the liver until the adhesive has dried (2 min). (G) The edges of the window are folded under the peritoneum and skin. (H) To secure the window to the peritoneum, adhesive is applied on the surface of the window, corresponding to the shaded area, before pushing the peritoneum down on it and gluing it in place. The skin is similarly glued onto the peritoneum. A rim of glue is also deposited along the red line to prevent growth of the epithelium over the window. (I) At high magnification, the liver (outlined by a white dashed line) is visible through the window. The imaging area is marked by the grid embedded in the window (white arrow head).

4.1 Place the mouse on the left lateral decubitus position

4.2 Make a 10 mm incision on the right flank 3 mm below the costal arch using sterile scissors and forceps.

4.3 Remove a 1 cm2 section of skin.

4.4 Use a second pair of sterile scissors and forceps to remove a section of the peritoneum slightly smaller than the section of skin.

4.5 Withdraw surgical adhesive with a 31 G syringe, apply a small quantity of it on the surface of the liver around the edges of the area to be imaged.

CAUTION: Limit the adhesive to small droplets forming a circular pattern around the imaging area. Tissue immediately in contact with the adhesive cannot be imaged.

NOTE: Any cyanoacrylate-based adhesives can be used successfully for this procedure. Surgical adhesive ensures sterility. For terminal procedures, all-purpose super glues yield good results.

4.6 Position the window using forceps and hold it firmly against the liver until the adhesive has dried (~2 min).

4.7 Fold the edges of the window under the peritoneum.

4.8 With a syringe, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the edges of the window that are now under the peritoneum. Push down on the peritoneum with forceps to secure it to the window.

4.9 Similarly, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the peritoneum and push it down on the skin with forceps to seal them.

NOTE: If performed correctly, a circular area of liver tissue should now be visible through the window.

4.10 Apply glue around the edges of the window to create a rim that will help prevent the skin from growing back over the window.

4.11. If a portal vein injection is required:

4.11.1 Place the mouse in the supine position.

4.11.2 Make a 10 mm incision starting down from the xiphoid process in the skin.

4.11.3 Using a second pair of sterile scissors and forceps, make a 10 mm incision in the peritoneum.

4.11.4 Dip two cotton swabs in sterile saline.

4.11.5 Use the cotton swabs to gently pull the intestine onto sterile gauze moistened with sterile saline, taking care not to twist or otherwise upset the orientation.

4.11.6 Keep displacing the intestine from the abdominal cavity until the portal vein is visible on the right side of the abdomen.

4.11.7 Insert a 31–33 G needle 5–7 mm caudal to the point of entry of the portal vein into the liver, making sure to proceed within the blood vessel and not through it.

4.11.8 Slowly inject the cancer cells (resuspended in 100 μL of sterile PBS).

4.11.9 To prevent bleeding, immediately after withdrawing the needle, apply gentle pressure on the injection site with a small piece of surgical sponge for 1–2 min.

4.11.10 After the pressure is released, monitor the site for 1–2 min to ensure hemostasis.

4.11.11 Using moistened cotton swabs, return the intestine into the abdominal cavity following the physiological orientation of the organ.

4.11.12 Using sterile forceps, insert the window immediately under the peritoneum, on the left side of the abdominal cavity of the mouse.

4.11.13 Suture and staple the midline incision.

4.11.14 Move the mouse to the left lateral decubitus position

4.11.15 Make a 10 mm incision on the right flank 3 mm under the costal arch through the skin using sterile scissors and forceps.

4.11.16 Remove a 1 cm2 section of skin around the incision.

4.11.17 Use a second pair of sterile scissors and forceps to remove a section of the peritoneum slightly smaller than the section of skin.

4.11.18 Pull the window into place over the liver before gluing it in place, as described under steps 4.8–4.10.

5. Inserting the window for imaging in the pancreas (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Surgical insertion of a window over the pancreas.

(A) The cartoon shows the anatomical location of structures relevant to the surgery. The black dashed box outlines the surgical field viewed in the pictures. (B) The mouse is placed in the right lateral decubitus position. The spleen is visible through the shaved skin (dashed line) (C) An incision is made starting 3 mm below the rib cage, and an approximately 1 cm2 section of skin is removed. (D) A slightly smaller section of the peritoneum is dissected. (E) The pancreas (white arrow head) is gently positioned with a moistened cotton swab in the location of the window. (F) Using a syringe, a small quantity of surgical adhesive is applied to the spleen, as well as the pancreas (away from the region to be imaged). (G) The window is positioned and held firmly against the pancreas until the adhesive has dried (2 min). The edges of the window are folded under the peritoneum and skin. (H) To secure the window to the peritoneum, adhesive is applied on the surface of the window corresponding to the shaded area, before pushing the peritoneum down on it and gluing it in place. The skin is similarly glued onto the peritoneum. A rim of glue is also deposited along the red line to prevent growth of the epithelium over the window. (I) At high magnification, the pancreas (outlined by a white dashed line) is visible through the window. The imaging area is marked by the grid embedded in the window (white arrow head).

5.1 Place the mouse on the right lateral decubitus position.

5.2 Make a 10 mm incision on the left flank 3 mm below the costal arch using sterile scissors and forceps.

5.3 Remove a 1 cm2 section of skin around the incision.

5.4 Use a second pair of sterile scissors and forceps to remove a section of the peritoneum slightly smaller than the section of skin.

5.5 Using sterile cotton swabs soaked with sterile saline, gently pull on the spleen to visualize the pancreas. Proceed to reposition the pancreas with the moistened cotton swabs to make more surface area visible through the incision.

Note: At this point, pancreatic cancer cells can be orthotopically injected into the pancreas if it is a part of the experimental design.

5.6 Withdraw surgical adhesive with a 31 G syringe, apply a small quantity of it on the surface of the pancreas around the edges of the area to be imaged.

CAUTION: Limit the adhesive to small droplets forming a circular pattern around the imaging area. Tissue immediately in contact with the adhesive cannot be imaged.

5.7 Position the window using forceps and hold it firmly against the pancreas until the adhesive has dried (~2 min).

5.8 Fold the edges of the window under the peritoneum.

5.9 With a syringe, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the edges of the window that are now under the peritoneum. Push down on the peritoneum with forceps to secure it to the window.

5.10 Similarly, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the peritoneum and push it down on the skin with forceps to seal them.

NOTE: If performed correctly, a circular area of pancreas tissue should now be visible through the window.

5.11 Apply glue around the edges of the window to create a rim that will help prevent the skin from growing back over the window.

6. Inserting the window for imaging in the mammary gland (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Surgical insertion of a window over the inguinal mammary gland.

(A) The cartoon shows the anatomical location of structures relevant to the surgery. The black dashed box outlines the surgical field viewed in the pictures. Note that the surgery can be performed on either the 4th or the 5th mammary glands. (B) The mouse is placed in a supine position on a sterile surgical field. The 5th right nipple (arrow head) is used as a landmark to perform the incision. (C) An incision is made, the mammary gland is separated from the overlying skin, and an approximately 1 cm2 section of skin is removed. (D) Using a syringe, a small quantity of surgical adhesive is applied in droplets around the area of interest on the surface of the mammary gland. (E) The window is positioned and held firmly until the adhesive has dried (2 min). (F) The edges of the window are folded under the skin using forceps. (G) To secure the window to the skin, adhesive is applied on the surface of the window corresponding to the shaded area, before pushing the skin down on it and gluing it in place. A rim of glue is also deposited along the red line to prevent growth of the epithelium over the window. (H) An example of a window implanted over a small tumor in the 4th right mammary gland is provided. Area outlined with dashed lines are shown in higher magnification in (I). (I) The droplets of adhesive on the mammary gland surface are outlined in red. The area to be imaged is outlined in black.

6.1 Place the mouse on the supine position.

6.2 Make a 10 mm incision medial to one of the inguinal nipples using sterile scissors and forceps.

6.3 Remove a 0.5 cm2 section of skin above the mammary gland.

6.4 Use a second pair of sterile scissors to carefully separate the mammary gland from the skin by spreading the scissors between the two surfaces to disrupt adherence.

NOTE: To facilitate imaging of the inguinal mammary gland area, be careful to dissect a portion of skin above the mammary gland but superior to the hind leg, so the window does not limit the mobility of the mouse.

6.5 Withdraw surgical adhesive with a 31 G syringe, apply a small quantity of it on the surface of the mammary gland around the edges of the area to be imaged.

CAUTION: Limit the adhesive to small droplets forming a circular pattern around the imaging area. Tissue immediately in contact with the adhesive cannot be imaged.

6.6 Position the window using forceps and hold it firmly against the mammary gland until the adhesive has dried (~2 min).

NOTE: A circular area of mammary gland tissue should now be visible through the window if performed correctly.

6.7 Fold the edges of the window under the skin.

6.8 With a syringe, deposit a small quantity of surgical adhesive on the edges of the window that are now under the skin. Push down on the skin with forceps to secure the skin to the window.

6.9 Apply glue around the edges of the window to create a rim that will help prevent the skin from growing back over the window.

7. Post-surgical recovery

7.1 Place the mouse in a clean recovery cage with ample nesting material, ensuring that part of the cage is resting on a heating pad.

7.2 Monitor the mouse continuously until it is conscious and mobile.

7.3 If needed, provide an additional dose of analgesic 12 h after the pre-emptive dose.

Note: Additional analgesia is generally unnecessary, but consult with a veterinarian if the mouse shows signs of distress (such as hunched back, unkept fur, or lost interest in food). Monitor the mouse daily for the first 3 days after surgery for signs of infection or other adverse effects. Less than 2% of mice require veterinary attention or euthanasia, typically due to partial detachment of the window. It is important to note that for male mice with ventral liver imaging windows, fighting between mice can result in detachment of windows. This is avoided by housing the mice separately.

8. Imaging through the window

8.1 Anesthetize the mouse in an induction chamber using 4% (v/v) isoflurane.

8.2 Apply ophthalmic lubricant to the eyes to keep them from drying and preventing trauma.

8.3 Move the mouse from the induction chamber to the microscope stage. Place the mouse in the anesthesia nose mask, and lower the isoflurane concentration to approximately 1–1.5% for maintenance anesthesia throughout the imaging procedure.

8.4 Place a pressure pad sensor below the mouse to monitor breath rate and fix the mouse to the stage using soft surgical tape.

8.5 Insert a rectal thermometer to monitor body temperature throughout the imaging session.

8.6 Turn on the heated pad, monitoring the mouse closely to ensure that body temperature does not exceed 37 °C.

8.7 Utilize software to monitor the breath rate of the mouse. The optimal rate is ~1 breath/second. Adjust anesthesia as required.

8.8 Before each imaging session, it is advisable to clean the window from any residual lens immersion medium and debris by gently wiping it with a cotton swab dipped in 70% ethanol (v/v).

8.9 When utilizing a water immersion lens, apply ultrasound gel to the window, avoiding bubbles.

Note: Distilled water can also be used but might require reapplication during imaging.

8.10 To find the optimal depth for imaging, first, locate the grid and place it in focus.

8.11 Determine the approximate tissue imaging depth by setting the bottom of the grid to 0. This information is necessary to locate the corresponding z plane in subsequent imaging sessions.

8.12 To identify the same location over multiple imaging sessions, utilize the squares on the grid as a reference point. During imaging, note the orientation of the grid and location within the grid of each field of view imaged (e.g., 2nd row from the top, 4th square from the left). During successive imaging sessions, use the grid to navigate back to specific grid areas - and thus imaging fields.

8.13 Following each imaging session, remove any residual lens immersion medium and debris by gently wiping the window with a cotton swab dipped in 70% ethanol (v/v).

REPRESENTATIVE RESULTS:

Intravital imaging through imaging windows can be used to observe, track, and quantify a wide array of cellular and molecular events at single-cell resolution over a period of hours to weeks. Ideal features for an imaging window include: a) limited impact on the well-being of the mouse and the physiology of the tissue; b) durability; c) simplicity of insertion; and d) clear landmarks for repeated imaging of the same region. The result is a versatile, inert silicone window that is easily produced and inserted and that can be outfitted with a grid to locate the same field of view over the span of several imaging sessions.

The window is made of PDMS, which is an inexpensive, flexible, and clear material. Windows can be cast with supplies that are widely available for purchase for most laboratories. Circular molds (22 mm diameter) can be generated simply from those already etched on the lid of commercially available 24 well-plates. By varying the amount of polymer used per unit area, it is possible to adjust the thickness of the window. To document the effect of thickness of the window on imaging, a point spread function (PSF) analysis of 40 nm fluorescent microspheres and compared the imaging resolution through PDMS windows of varying thicknesses to glass coverslips typically used for intravital imaging windows (0.17 mm thick). To replicate our set up for intravital imaging, we performed the imaging using the same two-photon microscope and water immersion lens and applied ultrasound gel as an immersion medium.

The Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the signal intensity calculated via the fit of the PSF in the lateral planes was comparable to that of glass for PDMS windows cast with 100 mg of PDMS (Figure 5A,B). The lateral resolution compared to glass coverslips was reduced for windows cast with 150–250 mg of PDMS (Figure 5A,B). In the z-axis image plane, PDMS windows cast with 100–200 mg of polymer performed better than glass coverslips (Figure 5C). Optical clarity was lost in windows cast with 300 mg of PDMS, making the measurements unreliable (Figures 5A–C). The X/Y ratio of the FWHM values did not significantly differ between glass and PDMS of any thickness, although the ratio for windows cast with 200–250 mg of polymer notably deviated from 1 using ultrasound gel as the immersion medium (Figure 5D). However, when using water as an immersion medium for our preferred window cast with 200 mg, the deviation from symmetry was much less pronounced. At this thickness, deviations due to aberrations in the polymer are therefore likely minor. Peak fluorescence intensity values were also collected for each bead and showed that glass and PDMS performed comparably, although the highest signal was recorded through glass (Figure 5I). The optimal thickness of the PDMS window will depend on specific applications and imaging systems. For our purposes, we find that using 200 mg of polymer solution for a 22 mm diameter circular window is an optimal compromise between window sturdiness and optical clarity. Indeed, windows cast with less than 200 mg were more optically clear, with FWHM values similar to glass, but occasionally tore during surgical implantation, while we observed no instances of window damage using 200 mg (in >100 mice).

Figure 5: Silicone imaging windows have favorable optical and material properties.

(A–C) To measure the point spread function and compare the imaging properties of the PDMS windows to that of glass coverslips, 40 nm yellow-green fluorescent microspheres were imaged through PDMS windows of varying thickness or glass coverslips (#1.5 thickness)16. Images were collected using ultrasound gel as immersion medium to match the conditions of intravital imaging. Plots show the calculated Full Width at Half Maximum in the (A) X-axis, (B) Y-axis, and (C) Z-axis (mean ± SD; n = 3/group, acquired using two or more separate windows; one-way ANOVA comparing all PDMS windows to glass with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test; only significant differences are indicated). (D) The ratio between calculated FWHM values in the X and Y axis (A–B) is shown as a measure of the symmetry of the point source images along the X and Y axes, and therefore of optical aberrations. (E–G) Microspheres were imaged through three separate windows cast with 200 mg of PDMS (similar to the windows used in for intravital imaging for Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Movie 2, Movie 3, Movie 4) or three glass coverslip (#1.5 thickness) to measure point spread function. In contrast to the intravital imaging examples, images for these calculations were collected using water as immersion medium. Plots show the calculated Full Width at Half Maximum in the (E) X-axis, (F) Y-axis and (G) Z-axis (mean ± SD; n = 3/group using three separate windows; Mann-Whitney test, no significant differences were detected). (H) Plot shows the ratio between calculated FWHM values in the X- and Y-axis (F–G). (I) Plots show the peak fluorescent intensity per bead (mean ± SD; n = 3/group; Mann-Whitney test, no significant differences were detected). All images were collected at a wavelength of 960 nm and a laser power of 3%. A 100 μm z-stack was collected for each bead, with a step size of 0.6 μm. Image frame was set at 69 μm x 69 μm with a resolution of 1022 pixels x 1022 pixels. Analysis was performed with Fiji - MetroloJ plugin. (J) To test material properties, PDMS windows were held in tension and secured between two ring-shaped washers using super glue to ensure an elastic response during mechanical testing. The same procedure was used for micro cover glass slips without the tension due to the rigidity of the glass. A loading tip consisting of a hemisphere (6 mm diameter) with a cylinder extrusion (4 mm diameter, 20 mm length) was 3D printed using a polylactic acid filament. The windows were loaded into a servohydraulic material testing machine under a load control profile of 1 N/s until material failure. Force and displacement values were measured at a frequency of 100 Hz. The image shows the window testing set up with the loading tip being applied at the center of the window. (K) Plot shows the toughness of the material determined by calculating the summation area under the stress-strain curve using the Trapz function in MATLAB (mean ± SEM; n = 3/group using three separate PDMS windows for each thickness and glass coverslips; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). (L) Plot shows the Young’s Modulus determined from the linear portion of the stress-strain curve (mean ± SEM; n = 3/group using three separate PDMS windows and glass coverslips; t-test with Welch’s correction).

To measure these difference in material properties, PDMS windows (200 mg and 150 mg) were loaded into a servohydraulic material testing machine under a load control profile of 1N/s until material failure (Figure 5J). Force and displacement values were measured at a frequency of 100 Hz. The force-displacement data was then converted to stress-strain using the equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where σ is stress (Pa), F is force (N), A is the cross-sectional area of the window, Ɛ is strain, ΔL is the displacement, and L0 is the thickness of the window. The toughness of the material was determined by calculating the summation area under the stress-strain curve. The toughness of a material refers to its ability to deform plastically and absorb energy in the process before fracture – a key property for implanted windows13. In agreement with our observations during imaging experiments, we found that windows cast with 200 mg of PDMS have significantly greater toughness than windows cast with 150 mg (Figure 5K) and are therefore less prone to breaking.

Next, we determined Young’s Modulus (E) of our preferred PDMS windows cast with 200 mg and compared it to that of standard glass coverslips by extracting the linear region of the stress-strain curve and determining the slope using Hooke’s law:

| (3) |

Young’s modulus of the glass windows was significantly greater than PDMS, which was expected because glass is much more rigid in material strength than PDMS (Figure 5L). Thus, although glass is a stronger material based on its greater Young’s modulus, the greater toughness of the 200 mg PDMS windows supports that they can be applied for longer periods without risk of breaking and necessitating a second surgical procedure or euthanasia.

A major advantage of silicone windows is their versatility. Importantly, the procedure to surgically insert the window can be easily tailored to different anatomical locations. Adaptations to the surgery are facilitated by the fact that the windows can be easily resized with surgical scissors and that windows are glued to the surface of the tissue/organ of interest and to the skin, completely eliminating the requirement for sutures. We have successfully implanted windows this way over liver, pancreas, and mammary gland (Figures 6A–C). In particular, we have devised two different protocols to implant either ventral or lateral windows for liver imaging. Figure 1 shows the steps to insert a ventral window. This procedure can be adapted for other abdominal organs and will yield the largest imageable surface area. However, unless a large (>1 cm2) imageable area is required, inserting a lateral window in the right flank of the mouse (Figure 2) is preferred to decrease motion artifacts, e.g., due to respiration and peristalsis. In addition, the surgical procedure for inserting the lateral imaging window is compatible with a concurrent injection of cancer cells in the portal vein to experimentally model the development of liver metastasis. Thus, mice can undergo a single procedure instead of two separate ones when portal vein injection and abdominal imaging window insertion are needed in the same animal. We have used an analogous procedure to implant a window over the pancreas on the left flank of the mouse (Figure 3). The window can also be inserted over subcutaneous tissues, i.e., normal mammary glands, as well as already established spontaneous or orthotopically transplanted mammary tumors (Figure 4). Alternatively, cancer cells can be injected in the mammary gland through the window to longitudinally follow the development of a primary tumor, as needles can puncture the PDMS film without compromising the integrity of the window.

Figure 6: The silicone window demonstrates high tolerability and longevity.

(A) A representative image of a male, 7-week old C57BL/6J mouse with a ventral abdominal imaging window without a grid 11 days after window surgery. (B) A representative image of a male 7-week old C57BL/6J mouse with a pancreatic imaging window containing a grid 14 days after window surgery. (C) A representative image of a female 12-week old C57BL/6J c-fms-EGFP mouse with a mammary gland imaging window containing a grid >7 days after window surgery. (D) Liver imaging window in a male 7-week old c-fms-EGFP mouse photographed (top row) and imaged (bottom row) on Day 0 (immediately after surgery) and 35 days post-surgery. Removing the appropriate amount of skin and sealing the wound with glue prevents the skin from re-epithelizing and pushing the window up and out, allowing the organ to be imaged long-term. Scale bars = 30 μm.

Owing to their low weight and flexibility, silicone windows do not interfere with the mobility of the mouse (Movie 1). Thus, silicone windows overcome major obstacles associated with glass windows, such as fragility, complex suturing, and impact on animal mobility. Instead, the main limitation associated with silicone windows is the regrowth of the epithelium under the window. However, when an appropriate amount of skin is removed and the wound is fully sealed with glue, re-epithelialization is limited, and imaging can continue over prolonged periods of time (we have tested up to 35 days, Figure 6D). After inserting the window, the mouse can be imaged longitudinally for approximately one month or until the surgical adhesive fails or re-epithelialization occurs. Short daily imaging sessions (~60 min) or less frequent but longer imaging sessions are favored to avoid anesthesia-induced adverse effects. Window-bearing animals can be imaged on any intravital imaging platform, via both single-photon or multiphoton confocal microscopy, using standard procedures (see, e.g.,14). Before and after each imaging session, it is advisable to clean the window from grime and debris by wiping it with a cotton swab dipped in 70% ethanol (v/v).

In order to track the same location over time, we employ stainless-steel grids embedded within the window. Figure 7A shows the specifications for the custom-made, laser-etched grids used in our study. Commercial grids for transmission electron microscopy are also suitable for this application. The grid is embedded within the window during the casting procedure and is clearly visible over the imaging area both to the naked eye (Figure 7B) and through the oculars of the microscope (Figure 7C). Because the window is glued to the surface of the organ, the position of imaging fields relative to the grid is stable. During imaging, we note the orientation of the grid and location within the grid of each field of view that we image (e.g., 2nd row from the top, 4th square from the left). Next, we use the grid to navigate back to specific grid areas - and thus imaging fields - during successive imaging sessions.

Figure 7: Grids within the windows allows tracking of the same field of view.

(A) Detailed specifications for the custom production of laser-cut stainless steel windows. (B) A grid embedded within the imaging window can be seen over the liver, with the rim of glue around the window clearly visible. (C) View of the window through the oculars of the two photon microscope. Blood vessels (red) and green signal from the liver can be seen in the background.

The grid is also useful to align the imaging field during an imaging session when the tissue slowly drifts due to, e.g., respiration or peristalsis. Most imaging windows with a rigid rim can be tethered to a holder during imaging, adding stability to the imaging area. Since our flexible windows cannot be directly stabilized, we use surgical tape to stabilize the body section containing the window, and we re-align the imaging area to the center of the corresponding grid square or previously identified tissue landmarks (e.g., vascular landmarks) at defined intervals (typically every 30 minutes). Further drift correction for microscopic shifting of the field of view is performed digitally in the post-acquisition phase through code that re-aligns the frames based on detected tissue patterns (Supplemental code 1–2).

To validate that the window does not cause any overt systemic adverse reaction, we monitored the weight of animals that had undergone window implantation and untreated age-matched controls. After an initial weight loss associated with surgery, most mice with inserted windows continue to gain weight over time, indicating that window insertion is well-tolerated (Figures 8A–C). For liver and mammary gland windows, normal weight is regained within 5 days from the surgery. Post-operative recovery is slower after implantation of the window over the pancreas, with mice reaching their pre-operative weight within 14 days. This observation is consistent with the expected effects associated with manipulation of the pancreas at the time of surgery. Note that even in cases when weight loss does not reach the threshold for humane endpoint, we typically censor mice that do not regain pre-operative body weight (<5% of all mice, exemplified by the mouse indicated by * in Figure 8B) from imaging experiments. In addition, we measured white blood cell counts at various time points after window insertion and found that they were not altered in almost any window-bearing mice compared to controls and did not change considerably over time (Figure 8D), suggesting that the window did not cause major systemic inflammation.

Figure 8: Systemic and local response to window insertion.

(A–C) Weight was monitored for 7-week-old C57BL/6J female mice for a period of 28 days following window insertion in the liver (A), the pancreas (B) or the mammary gland (C). Percent body weight change in comparison to untreated age-matched mice is shown. (*) indicates a mouse that did not regain normal body weight and would have therefore been censored from an imaging experiment. The same control mice are shown in all three panels for easier comparison to each type of window. (D) White blood cell (WBC) count monitored on days 3, 14, and 28 (mammary gland window) or 35 (liver or pancreas window) after surgery. The normal range for WBC count in the mouse is indicated by dashed lines. (E,G,I) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue sections from untreated controls (left) and a 7-week-old C57BL/6J mouse 14 days after insertion of an imaging window (right) over the (E) liver, (G) pancreas, or (I) mammary gland. (E,I) Superficial and focal granulation lesions are visible at discrete places along the surface (arrow) of liver and mammary gland, suggesting a reaction to the glue. Normal tissue indicated by * is visible in the regions adjacent to the granulation lesions. Three controls and three mice with liver windows were evaluated at each time point (days 3, 14, and 35 following surgery), except that 6 mice with liver windows were evaluated at day 35 following surgery. Two out of 3 mice exhibited granulation tissue at days 3 and 14. 1 out of 3 mice exhibited granulation tissue at day 35. Three controls and three mice with mammary gland windows were evaluated at each time point (days 3, 14, and 28 following surgery). Three out of 3 mice had granulation tissue or inflammatory reactions in the fat tissue of the mammary gland at days 3 and 14. Zero out of 3 mice exhibited granulation lesions or inflammatory reactions at day 28. (G) No significant lesions are visible in the pancreas. Three controls and three mice with pancreas windows were evaluated at each time point (days 3, 14, and 35 following surgery). Mice with pancreatic windows did not have granulation tissue at any time point. Scale bar = 500 μm (F,H,J) Multiplex immunohistochemical staining was performed on tissue sections from untreated controls and 7-week-old C57BL/6J mice 14 days after insertion of an imaging window over the (F) liver, (H) pancreas or (J) mammary gland. Antibodies against CD45, CD68 and myeloperoxidase (MPO) were used to label leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils respectively. CD45 and CD68 staining were performed on the same section while MPO staining was performed on a serial section of the same tissue. The anti-CD45 antibody was detected with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and imaged first, then the chromogen and the secondary antibody were stripped and slides were incubated with a secondary antibody recognizing anti-CD68. Quantification was performed with Fiji software by color thresholding; parameters were adjusted across antibodies and tissues. Plots show the quantification as cell counts per field of view (FOV) (mean ± SEM; n = 3/group; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; only significant differences are indicated). (K) Male C57BL/6J c-fms-EGFP mice 8–11 weeks of age had a silicone imaging window inserted over the right lobe of the liver. Fluorescently labeled lectin (100 μL) was injected intravenously immediately before each imaging session. Images are from a single mouse, at the same grid locus on days 1, 3, and 5 following surgery, at approximately 200 μm below the grid. Scale bar = 30 μm. Imaged using an excitation wavelength of 960 nm, laser power 10%. Blood vessels appear in red. Macrophages appear in green (white arrows). Representative of three imaged mice.

Next, to evaluate the degree of local tissue response to the window and the glue, we euthanized mice 3, 14, and 28 (mammary gland windows) or 35 days (liver and pancreas windows) after surgical insertion of the window for histological analysis. Upon hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of liver sections, we found superficial (20–80 μm), minimal to mild capsular granulation tissue formation under the windows for most mice (2 out of 3 mice evaluated at day 3, and 2 out of 3 evaluated at day 14). These lesions were focal (1–3 mm in length), corresponding approximately to the width of the glue layer (Figure 8E). After 35 days, most mice (4 out of 6 evaluated in two separate experiments) presented no granular tissue, while a few (2 out of 6) had moderate focal capsular sclerosis and desmoplasia (at a depth of 25–250 μm). Interestingly, no significant lesions were observed on the surface of the pancreas directly under the window at any time point in our cohort of nine mice (Figure 8G). However, some mice displayed areas of atrophy in the pancreata and inflammation in the abdominal fat (steatitis), consistent with manipulation-induced damage. For the mammary gland, on days 3 after window implantation, 3 out of 3 mice had either granulation tissue reminiscent of a healing incision visible along the surface of the gland or an inflammatory reaction in the fat tissue; at day 14, 3 out of 3 mice evaluated had granulation tissue. These lesions were again focal and 1–3 mm in length (Figure 8I). Mice with mammary gland windows euthanized 28 days after surgery showed no obvious histological abnormalities.

Based on this analysis, we conclude that the window does not compromise the overall physiological architecture of the organs tested (liver, pancreas, mammary gland). The reactive tissue found on the surface of the liver and the mammary gland was compatible with a reaction to the glue and limited to tissue immediately in contact with the adhesive. Normal tissue can be readily found adjacent (< 100 μm) to the reactive tissue in regions not exposed to glue (Figure 8E,I), and the tissue inflammation, therefore, does not interfere with the imaging of healthy tissue regions. Moreover, the tissue reaction is likely reversible as most mice (8 out of 9 mice, across all tissue locations) showed no significant lesions at the late time points (28 or 35 days), although direct confirmation that the tissue reaction resolves would be hard to achieve without longitudinal measurements in individual mice.

We also performed multiplexed immunohistochemical staining for CD45, CD68, and myeloperoxidase (MPO) to characterize the infiltration of leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and neutrophils, respectively. We found an increase in immune cell infiltration associated with granulation tissue and steatitis in the mammary gland and the liver, but not in the pancreas (Figure 8F,H,J). Of note, these changes were likely transient as the immune cell infiltrate was comparable to that of the untreated controls at the last time points (28 days for mammary gland windows and 35 days for liver and pancreas windows).

We chose the liver as the site to further characterize whether window insertion and imaging caused significant local immune infiltration using imaging. We employed c-fms-EGFP (MacGreen) mice15, in which myeloid cells (mostly macrophages) are labeled with a green fluorescent protein. We inserted the liver windows in three c-fms-EGFP mice and imaged them on days 1, 3, and 5 following surgery using the grid to locate the same field of view. We found that that the number of macrophages present in the imaging area did not change considerably over time following window insertion (Figure 8K).

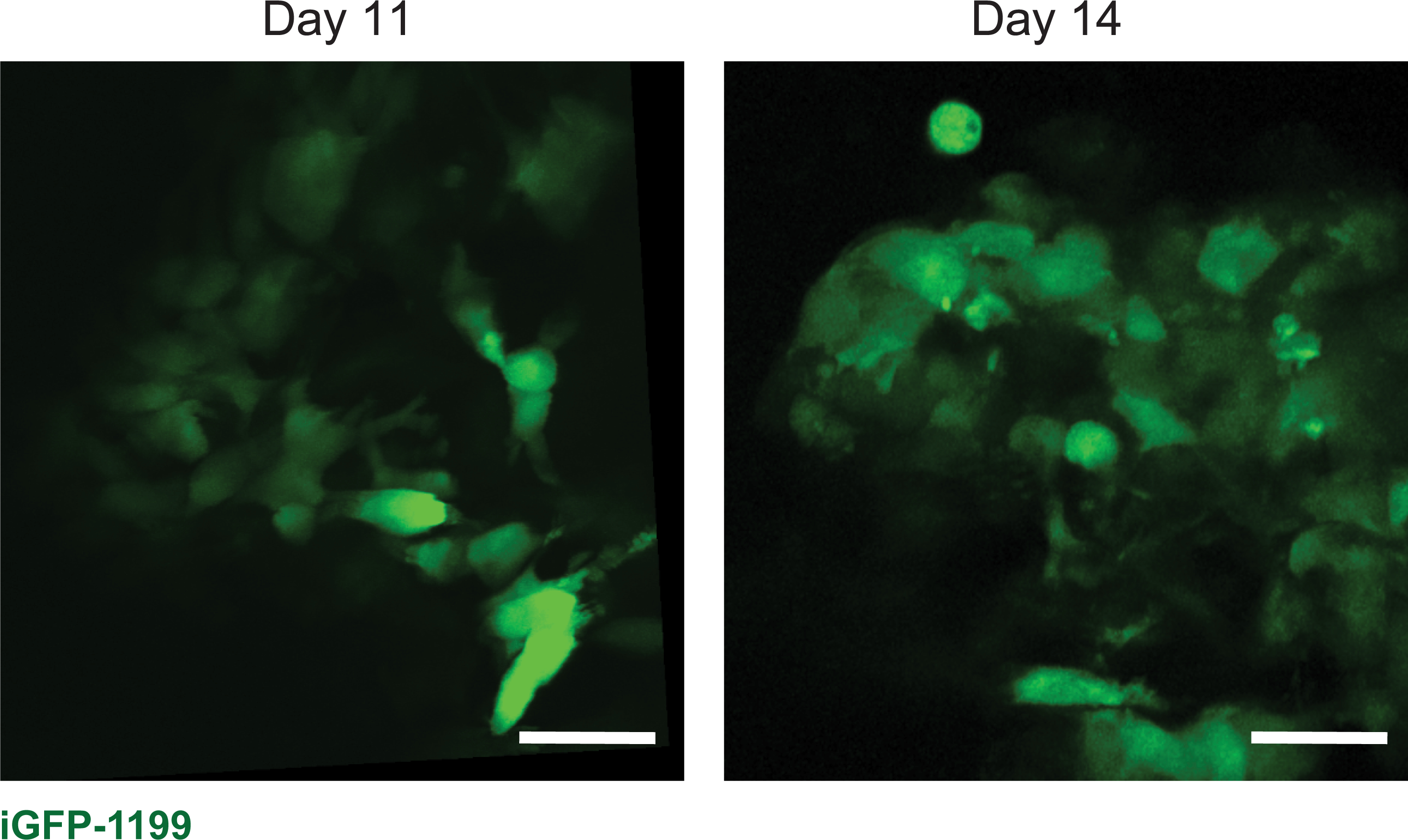

Next, we applied the window to image a diverse set of biological processes at the cellular level (i.e., movement, proliferation, cell-cell contact) and tissue level (i.e., tumor growth in the pancreas, immune infiltration during mammary gland involution, and liver metastasis). The pancreas is not an easily accessible location for imaging. To demonstrate how the window can be utilized to capture cancer cell dynamics in this organ, we inserted windows over the pancreas of six C57BL/6J mice at the same time as orthotopic injection of KPC-BL/6–1199 cells, a pancreatic cancer cell line derived from a commonly used KPC (KrasLSL- G12D/+;p53LSL-R172H;Pdx1-Cre) genetically engineered mouse model of pancreatic cancer. In order to be visualized by confocal microscopy, KPC-BL/6–1199 cells were engineered to express doxycycline-inducible enhanced GFP (iGFP-1199 cells). Six days following injection, the mice were put on a doxycycline diet to trigger expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the pancreatic cancer cells. Figure 9 shows representative images from a mouse orthotopically injected with iGFP-1199 cells on days 11 and 14 following injection and window insertion. Movie 2 shows the iGFP-1199 tumor edge in an excerpt of a 2-h imaging session on day 11 after window insertion, illustrating the ability to capture dynamics of cell membrane projection in the pancreas using our silicone windows.

Figure 9: Tumors can be visualized at multiple time points over weeks after window insertion.

Representative images from one male 7-week old C57BL/6J mouse orthotopically injected with 1.5 × 104 iGFP-1199 pancreatic cancer cells at the time of pancreatic window insertion, and imaged on days 11 and 14 after window insertion. Scale bars = 30 μm. Imaged using an excitation wavelength of 960 nm, laser power 10%. Representative of 6 imaged mice.

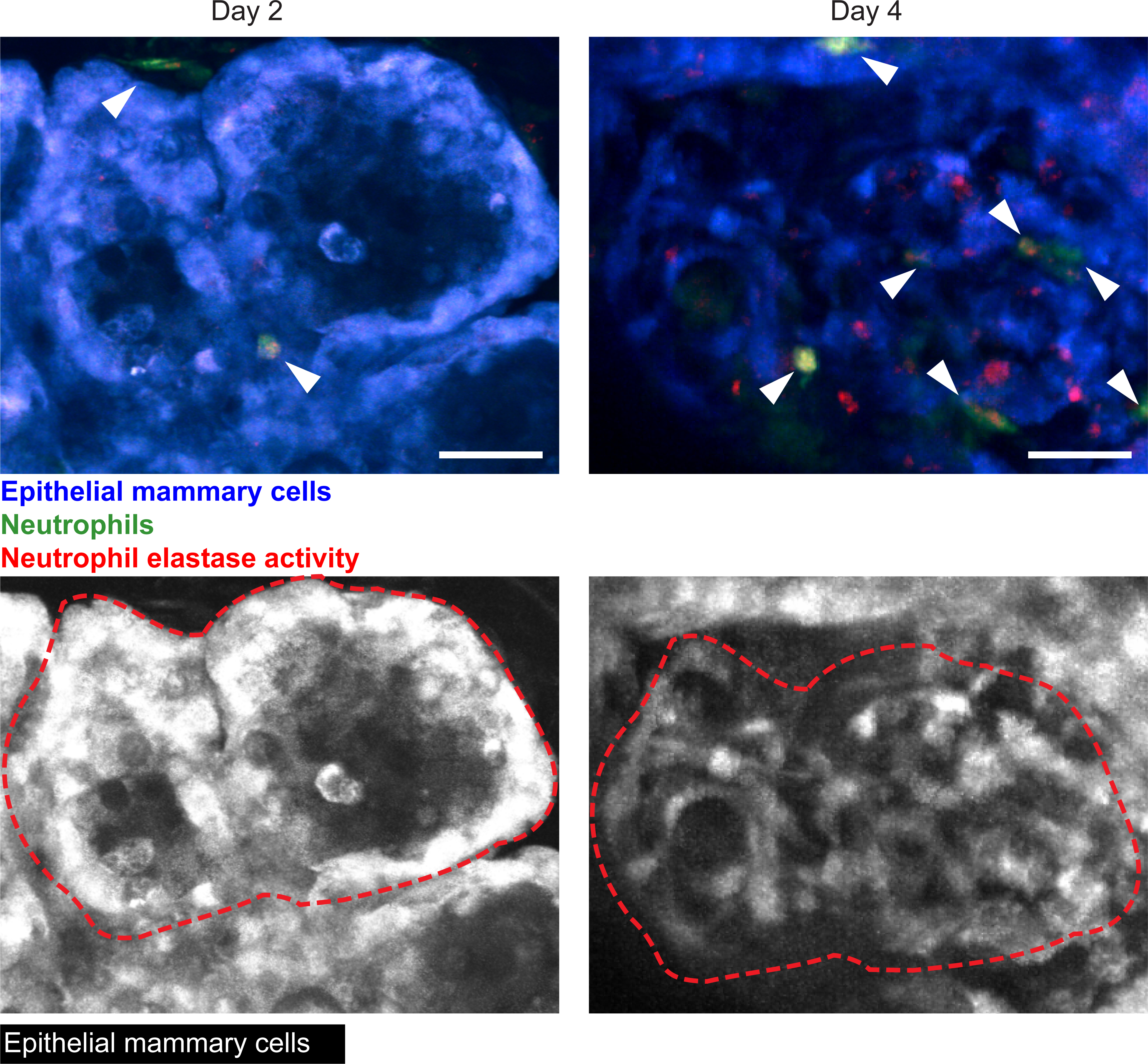

The silicone window can also be used to capture dynamic immune cell infiltration over time. To illustrate this, we inserted mammary gland windows into lactating ACTB-ECFP (Tg(CAG-ECFP)CK6Nagy); LysM-eGFP (Lyz2tm1.1Graf) mice immediately after weaning. In these mice, all cells, but most highly epithelial cells, express cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) driven by the beta actin promoter, and myeloid cells—primarily neutrophils, but also macrophages—are labeled by eGFP driven by the lysozyme M promoter. The mice were imaged on days 2 and 4 after window insertion, during the process of mammary gland involution, when mammary gland tissue begins returning to its pre-pregnancy state. To reduce motion artifacts and improve visualization, we developed two macros for ImageJ that help align the Z planes in a 4-dimensional intravital video (Supplemental code 1) and reduce the wobbliness due to breathing or other motion artifacts (Supplemental code 2). Figure 10 and Movie 3A–C show neutrophil infiltration within the remodeling mammary gland tissue at the same location at days 2 and 4, illustrating how the window could be used to monitor and track immune cell infiltration and movement over different days. An analogous experiment was conducted in a c-fms-EGFP mouse, with myeloid cells (mainly macrophages) expressing GFP driven by the c-fms promoter (Movie 4).

Figure 10: Dynamic changes in immune cell infiltration during normal mammary gland involution.

Using the metal grid embedded in the imaging window, the same location can be imaged during normal tissue remodeling, such as during mammary gland involution. To further evaluate the functionality of our silicone windows in monitoring dynamic changes like immune cell infiltration, a 12-week old female C57BL/6J x BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mouse with an imaging window inserted over the abdominal mammary gland was imaged on days 2 and 4 after mammary gland involution. Neutrophils appear in green (white arrows). Neutrophil elastase activity was visualized by injecting a Neutrophil Elastase fluorescent probe 4 hours before beginning imaging, and appears in red (or yellow when colocalized with neutrophils). The epithelial cells appear in blue. Snapshots are a maximum intensity projection of five images along the Z axis (100–150 μm in depth). Images are from Movies 3A and 3B, and on the lower row images, only the CFP signal is shown and images are marked with a red dashed line to visualize the same locations within tissue at the two different time points. Scale bars = 30 μm. Imaged using 960 nm and 1080 nm excitation wavelengths, laser power at 10% and 15% respectively. Representative of four imaged mice.

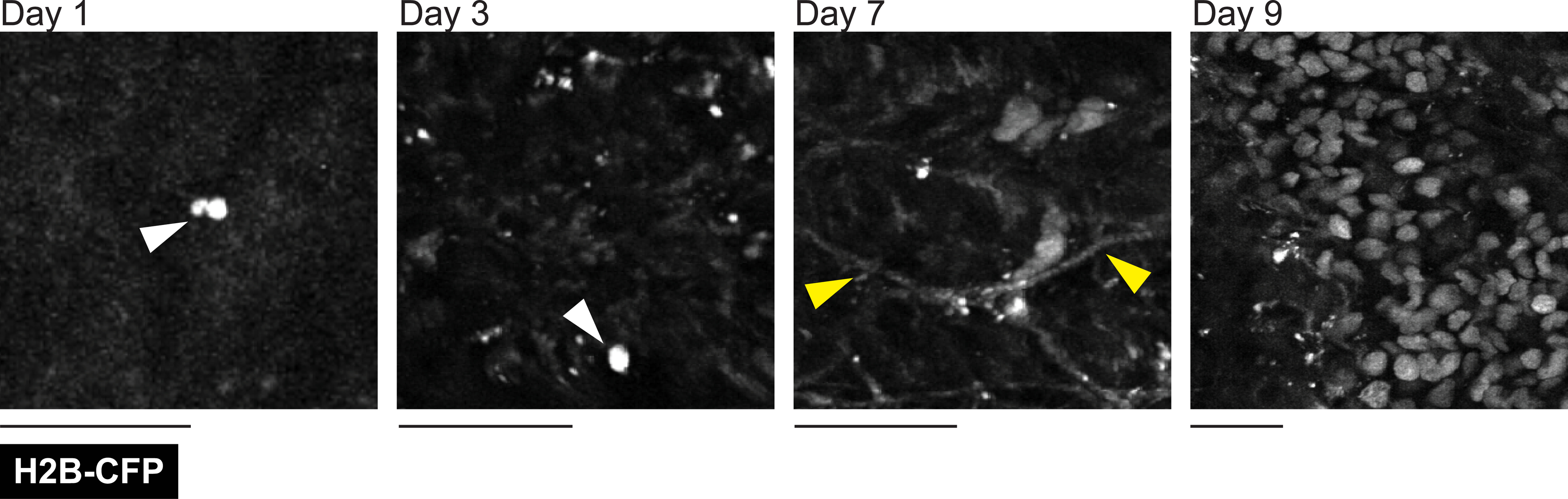

Lastly, the relatively large surface area of our customizable window allows one to observe rare events, such as the formation of liver metastasis after intravenous inoculation. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we inserted liver windows in C57BL/6J mice at the time of portal vein injection with KPC-BL/6–1199 pancreatic cancer cells constitutively expressing the nuclear fusion protein histone2B-CFP (H2B-CFP). We were able to monitor the outgrowth of single cells and small clusters of 2–3 cells as they developed into micrometastases (>100 cells). Figure 11 shows representative images taken on days 1, 3, 7, and 9 after injection and window insertion and demonstrates the progression from single cells to micrometastases.

Figure 11: The formation of cancer metastasis can be tracked over time.

A male C57BL/6J 10-week-old mouse injected with 1 × 105 KPC-BL/6–1199 pancreatic cancer cells expressing nuclear localized histone H2B conjugated cyan fluorescent protein (H2B-CFP) through the portal vein at the time of window insertion. Liver imaging was performed through a lateral window 24 h after injection and at two later time points (up to 9 days), as indicated. A single cancer cell visible on days 1 and 3 following injection are indicated with white arrows. Second harmonic signal from collagen fibers was also visualized in the cyan channel (yellow arrows). Images are from the same mouse at each different time point. Single z-plane images taken between 300 μm and 350 μm in depth. Scale bars = 30 μm. Imaged using an excitation wavelength of 880 nm. Laser power at 8%. Representative of three imaged mice.

All images and movies were collected using a multiphoton microscope. Maximum intensity projections and movie alignments along the Z and X axes over time were generated using ImageJ software. Aligned images and movies were then compiled using Imaris software.

DISCUSSION:

Intravital imaging windows are important tools for directly visualizing physiological and pathological processes at cellular resolution as they unfold over time. We have described a novel procedure for casting and inserting flexible, silicone imaging windows in mice. This new approach overcomes some of the most common issues with currently used imaging windows (exudate, breaking, and interference with normal mobility), provides additional safety for the mouse, and increases the accessibility of this technique.

The most widely used imaging windows comprise a metal frame holding a glass coverslip. A major obstacle to the use of these prototypical windows is that securing the metal ring involves laborious stitching procedures, necessitating personnel with advanced surgical training. In addition, manufacturing the frames is costly and requires specialized equipment. The PDMS windows overcome both of these issues. The procedure to insert the PDMS windows eliminates stitching, significantly lowering the barrier to learning the technique. The materials to produce the windows are also inexpensive and can be easily purchased. In addition, both the shape of the window and the surgical procedure can be adapted for imaging different organs, including the mammary gland, liver, pancreas, spleen, and intestine.

Whereas current intravital imaging windows allow longitudinal imaging for typically a few days, several common problems limit their use for extended periods of time. The weight and size of glass windows can interfere with the free movement of the mice, and exudate can accumulate against the window. Mice can also damage the glass coverslip, resulting in wounds and infections. In contrast, our procedure maintains the same level of accessibility to the tissue while minimizing distress for the animals. PDMS is a safe, biostable, synthetic polymer widely used for biomedical applications in humans, such as drug delivery devices, facial-reconstruction surgery, and breast implants. Beyond increasing the animals’ tolerance of the window, the use of a biologically inert material, as opposed to glass, is particularly important for studies that involve the immune system, where local inflammation would be a confounding effect. Additionally, a major improvement is the elimination of stitches, as mice will bite and pull at them, which can cause the metal-framed glass imaging windows to fall out. This issue was partially addressed by a newer generation of windows that were designed so that the stitches are concealed in a groove9. However, this latter strategy requires purse-string suturing, which is a complicated, error-prone procedure that often causes stitches to be pulled too tight, resulting in necrosis of the tissue and pain. Therefore, the ability to glue the window in place constitutes a major advantage of our novel approach. Furthermore, the window is made of a flexible, durable material with negligible weight, which decreases its impact on the movement of the animal, as previously assessed in a comparison of windows that used silicone instead of metal to hold a glass coverslip17. By completely eliminating the glass coverslip, our window eliminates the issues with both the metal frames and glass. Furthermore, the flexibility of the window allows it to be inserted with ease and decreases the stress force caused by gluing a rigid surface to the organs, thus decreasing the risk of permanent damage to the tissue being observed. In addition, because the window is much easier to insert and hold in place, the overall procedure takes less time, limiting the possible side effects due to prolonged anesthesia. For insertion over the liver, the difference in procedure time is particularly substantial, from 45 min for metal-framed windows to 15 min for the silicone windows in our hands. In fact, whereas inserting the metal frame over the liver requires dissection of the xiphoid process (the cartilage at the end of the sternum), which is also potentially painful and causes sustained inflammation, this dissection is unnecessary for inserting the silicone window. Lastly, the imaging window presented in this work provides additional advantages with regard to possible applications. For instance, unlike glass windows, silicone windows provide easy access to the tissue, so cancer cells, fluorescent dyes, or drugs can be injected directly through the window.

Another PDMS-based silicone imaging window suitable for insertion at a variety of anatomical locations, including the mammary gland, was recently described18. In contrast to our window, this window is molded to generate a shape and specialized edge that allows for rapid implantation of the window without the need for stitches or glue. Our window does not require any special mold and importantly, can be cut to shape during the surgical procedure to adapt to the anatomical location and individual mouse. Although implantation of our window necessitates the use of glue, this additional requirement allows imaging of abdominal organs, including the liver and spleen. Moreover, the embedding of a stainless-steel grid within our window provides reference landmarks to trace the same exact location over time and facilitates repeated imaging of the same site over multiple sessions (longitudinal imaging) to study processes that take days to weeks such as the development of metastatic lesions.

In summary, we have adapted a silicone imaging window for use in longitudinal IVM of the mammary gland or abdominal organs. The window is optically clear, highly durable, and inexpensive. The simplicity of the window insertion procedure reduces the technical skills required for implementing window-based intravital imaging approaches. The adaptability of the window to diverse tissue sites allows the implementation of IVM in a vast array of biological studies.

Supplementary Material

Movie 1: Silicone imaging windows are well tolerated in mice. Movie shows a male 9-week old C57BL/6J mouse 14 days following window insertion. Mouse does not exhibit any of the standard behaviors associated with pain (e.g., poor grooming, closed eyes, or lethargy). Representative of six recorded mice, and consistent with over 100 mice observed following successful window implantation.

Movie 2: Subcellular imaging of orthotopically implanted pancreatic cancer cells. iGFP-1199 cells were injected orthotopically into the pancreas of a male 7-week old C57BL/6J mouse and imaged on day 11 after injection of cancer cells and window insertion. The movie is a maximum intensity projection of six images along the Z axis and extracted from a 2-h imaging period. Time stamp (h:min:s:ms). Representative of six imaged mice.

Movie 3A: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 2 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a maximum intensity projection of five images along the Z axis (100–150 μm in depth). Scale bar = 20 μm. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Imaged using 960 nm and 1080 nm excitation wavelengths, laser power at 10% and 15% respectively.

Movie 3B: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 4 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a maximum intensity projection of five images along the Z axis (100–150 μm in depth). Scale bar = 20 μm. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of four imaged mice.

Movie 3C: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 4 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a higher magnification of a region of interest from Movie 3B, showing two neutrophils interacting with each other and the epithelial cells of the mammary gland. The formation of transient membrane protrusions can be observed at the leading edge during neutrophil migration. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of four imaged mice.

Movie 4: Changes in immune cell infiltration in c-fms-EGFP mice during involution. Female C57BL/6J c-fms-EGFPmice, with GFP-labeled macrophages, were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, litters were adjusted to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. The movie, acquired on involution day 1 (one day after insertion of the window), highlights the prominent macrophage infiltrate during involution. Macrophages appear in green, collagen fibers (second-harmonic generation) appear in blue, and blood vessels appear in red (Lectin-DyLight 594). Scale bar = 20 μm. Images are maximum intensity projections of five images along the Z axis (100–150 um in depth). Imaged using 960 nm and 800 nm excitation wavelengths, laser power at 10% and 15% respectively. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of three imaged mice.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

We would like to thank Rob Eifert for his assistance in designing and optimizing the laser-cut stainless steel grids. This work was supported by the CSHL Cancer Center (P30-CA045508) and funds for M.E. from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1R01CA2374135 and 5P01CA013106–49); CSHL and Northwell Health; the Thompson Family Foundation; Swim Across America; and a grant from the Simons Foundation to CSHL. M.S. was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Medical Scientist Training Program Training Award (T32-GM008444) and the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award number 1F30CA253993–01. L.M. is supported by a James S. McDonnell Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship. J.M.A. is the recipient of a Cancer Research Institute/Irvington Postdoctoral Fellowship (CRI Award #3435). D.A.T. is supported by the Lustgarten Foundation Dedicated Laboratory for Pancreatic Cancer Research and the Thompson Family Foundation. Cartoons were created with Biorender.com.

Footnotes

A complete version of this article that includes the video component is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.3791/62757.

DISCLOSURES:

M.E. is a member of the research advisory board for brensocatib for Insmed, Inc.; a member of the scientific advisory board for Vividion Therapeutics, Inc.; a consultant for Protalix, Inc.; and holds shares in Agios Pharmaceuticals, Inc. D.A.T. is co-founder of Mestag Therapeutics, and is on the scientific advisory board and holds shares in Mestag Therapeutics, Leap Therapeutics, Surface Oncology, and Cygnal Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Dondossola E et al. Intravital microscopy of osteolytic progression and therapy response of cancer lesions in the bone. Science Translational Medicine. 10 (452), eaao5726 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haeger A et al. Collective cancer invasion forms an integrin-dependent radioresistant niche. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 217 (1), e20181184 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper KL et al. Mechanism of early dissemination and metastasis in Her2(+) mammary cancer. Nature. 540 (7634), 588–592 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eickhoff S et al. Robust anti-viral immunity requires multiple distinct T cell-dendritic cell interactions. Cell. 162 (6), 1322–1337 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelhardt JJ et al. Marginating dendritic cells of the tumor microenvironment cross-present tumor antigens and stably engage tumor-specific T cells. Cancer Cell. 21 (3), 402–417 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sammicheli S et al. Inflammatory monocytes hinder antiviral B cell responses. Science Immunology. 1 (4) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Entenberg D et al. A permanent window for the murine lung enables high-resolution imaging of cancer metastasis. Nature Methods. 15 (1), 73–80 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewald AJ, Werb Z, Egeblad M Preparation of mice for long-term intravital imaging of the mammary gland. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2011 (2), pdb prot5562 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritsma L et al. Surgical implantation of an abdominal imaging window for intravital microscopy. Nature Protocols. 8 (3), 583–594 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittet MJ, Garris CS, Arlauckas SP, Weissleder R Recording the wild lives of immune cells. Science Immunology. 3 (27), eaaq0491 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alieva M, Ritsma L, Giedt RJ, Weissleder R, van Rheenen J Imaging windows for long-term intravital imaging: General overview and technical insights. Intravital. 3 (2), e29917 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heo C et al. A soft, transparent, freely accessible cranial window for chronic imaging and electrophysiology. Scientific Reports. 6, 27818 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson TL Fracture Mechanics: Fundamental and Applications. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Florida: (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakasone ES, Askautrud HA, Egeblad M Live imaging of drug responses in the tumor microenvironment in mouse models of breast cancer. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE. 73, e50088 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasmono RT et al. A macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor-green fluorescent protein transgene is expressed throughout the mononuclear phagocyte system of the mouse. Blood. 101 (3), 1155–1163 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cole RW, Jinadasa T, Brown CM Measuring and interpreting point spread functions to determine confocal microscope resolution and ensure quality control. Nature Protocols. 6 (12), 1929–1941 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobolik T et al. Development of novel murine mammary imaging windows to examine wound healing effects on leukocyte trafficking in mammary tumors with intravital imaging. Intravital. 5 (1), e1125562 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacquemin G et al. Longitudinal high-resolution imaging through a flexible intravital imaging window. Science Advances. 7 (25), eabg7663 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie 1: Silicone imaging windows are well tolerated in mice. Movie shows a male 9-week old C57BL/6J mouse 14 days following window insertion. Mouse does not exhibit any of the standard behaviors associated with pain (e.g., poor grooming, closed eyes, or lethargy). Representative of six recorded mice, and consistent with over 100 mice observed following successful window implantation.

Movie 2: Subcellular imaging of orthotopically implanted pancreatic cancer cells. iGFP-1199 cells were injected orthotopically into the pancreas of a male 7-week old C57BL/6J mouse and imaged on day 11 after injection of cancer cells and window insertion. The movie is a maximum intensity projection of six images along the Z axis and extracted from a 2-h imaging period. Time stamp (h:min:s:ms). Representative of six imaged mice.

Movie 3A: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 2 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a maximum intensity projection of five images along the Z axis (100–150 μm in depth). Scale bar = 20 μm. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Imaged using 960 nm and 1080 nm excitation wavelengths, laser power at 10% and 15% respectively.

Movie 3B: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 4 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a maximum intensity projection of five images along the Z axis (100–150 μm in depth). Scale bar = 20 μm. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of four imaged mice.

Movie 3C: Changes in immune cell infiltration during involution. Imaging immune cell infiltration during mammary gland involution, day 4 of involution. Female C57BL/6J × BALB/c ACTB-ECFP; LysM-eGFP mice expressing GFP in myeloid cells (mainly in granulocytes but also in macrophages), and ECFP in all cells (but highest in epithelial cells) were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, pups were normalized to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. Myeloid cells appear in green; neutrophil elastase activity, labeled using the Neutrophil Elastase 680 FAST probe injected 4 h before the start of imaging, appears in red (will appear yellow when colocalized with neutrophils); and epithelial cells appear in blue. Movie is a higher magnification of a region of interest from Movie 3B, showing two neutrophils interacting with each other and the epithelial cells of the mammary gland. The formation of transient membrane protrusions can be observed at the leading edge during neutrophil migration. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of four imaged mice.

Movie 4: Changes in immune cell infiltration in c-fms-EGFP mice during involution. Female C57BL/6J c-fms-EGFPmice, with GFP-labeled macrophages, were bred at 8 weeks of age. Following parturition, litters were adjusted to six pups per mouse. On day 10 after parturition, the pups were weaned and abdominal mammary gland imaging windows were inserted. The movie, acquired on involution day 1 (one day after insertion of the window), highlights the prominent macrophage infiltrate during involution. Macrophages appear in green, collagen fibers (second-harmonic generation) appear in blue, and blood vessels appear in red (Lectin-DyLight 594). Scale bar = 20 μm. Images are maximum intensity projections of five images along the Z axis (100–150 um in depth). Imaged using 960 nm and 800 nm excitation wavelengths, laser power at 10% and 15% respectively. Time stamp (hr:min:sec:ms). Representative of three imaged mice.