Abstract

Background:

Little is known about clinical characteristics, hospital course, and longitudinal outcomes of patients with cardiogenic shock (CS) from heart failure (HF-CS) as compared to acute myocardial infarction (AMI-CS).

Methods:

We examined in-hospital and one-year outcomes of 520 (219 AMI-CS, 301 HF-CS) consecutive patients with CS (1/3/2017–12/31/2019) in a single center registry.

Results:

Mean age was 61.5±13.5 years, 71% were male, 22% were Black, and 63% had chronic kidney disease. The HF-CS cohort was younger (58.5 vs. 65.6 years, p <0.001), had fewer cardiac arrests (15.9% vs. 35.2%, p <0.001), less vasopressor utilization (61.8% vs. 82.2%, p <0.001), higher pulmonary artery pulsatility index (2.14 vs. 1.51, p < 0.01), lower cardiac power output [CPO] (0.64 vs. 0.77 W, p <0.01) and higher pulmonary capillary wedge pressure [PCWP] (25.4 vs. 22.2 mmHg, p<0.001) than AMI-CS patients. HF-CS patients received less temporary mechanical circulatory support [tMCS] (34.9% vs. 76.3% p <0.001) and experienced lower rates of major bleeding (17.3% vs. 26.0%, p=0.02) and in-hospital mortality (23.9% vs. 39.3%, p< 0.001). Post discharge, 133 AMI-CS and 229 HF-CS patients experienced similar rates of 30-day readmission (19.5% vs. 24.5%, p=0.30) and major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (23.3% vs. 28.8%, p=0.45). HF-CS patients had lower one-year mortality (n=123, 42.6%) as compared to the AMI-CS patients (n=110, 52.9%, p=0.03). Cumulative one-year mortality was also lower in HF-CS patients (log-rank test, p=0.04).

Conclusion:

HF-CS patients were younger, and despite lower CPO and higher PCWP, less likely to receive vasopressors or tMCS. Although HF-CS patients had lower in-hospital and one-year mortality, both cohorts experienced similarly high rates of post discharge MACCE and 30-day readmission, highlighting that both cohorts warrant careful long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, myocardial infarction, heart failure, mechanical circulatory support, shock team, multidisciplinary care

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a hemodynamically complex syndrome with multiple culprit etiologies and persistently high morbidity and mortality.1–3 Despite the uniform adoption of early revascularization for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), the advent of regionalized systems of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) care, and technologic advancements of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support (MCS) devices, short-term outcomes in CS remain poor, with in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 40% to 50%.1–3 Although the majority of prior research has focused on AMI-CS, recent observational studies suggest that non-ischemic etiologies, such as acute decompensated heart failure-CS (HF-CS), account for more than one-half of all CS causes.4–6 In the absence of randomized clinical trials, significant clinical practice variations in the acute management of AMI-CS and HF-CS persists, and the comparative outcomes of these two types of cardiogenic shock are not well-understood.7,8

Single center data suggest that a standardized and team-based approach (STBA) to CS care may be associated with improved outcomes. 9–14 This care delivery model is predicated on timely diagnosis, detailed hemodynamic assessment, tailored and appropriate mechanical circulatory support (MCS), and comprehensive longitudinal inpatient care.15 However, within this construct, little is known about the differences in clinical presentation and hospital course of AMI-CS vs. HF-CS, including hemodynamics, utilization of temporary MCS devices, and adverse events that may result both during the hospital course and following discharge. Furthermore, there is a paucity of clinical data reporting CS outcomes beyond 30-days post-hospital discharge.14 The purpose of this study was to compare: a) clinical characteristics, hemodynamics, treatment strategies, and hospital course and b) 30-day and one-year outcomes in patients with AMI-CS vs. HF-CS.

METHODS

Patients and Setting

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. From January 3, 2017 to December 31, 2019, 520 consecutive patients admitted to our quaternary care center with a diagnosis of CS were prospectively identified and retrospectively reviewed. We included patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of CS, due to both acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and acute decompensated heart failure (HF). Our shock team’s composition and protocol have been described previously and are included in the supplement (Figure S1 and S2).9 In brief, clinical and hemodynamic criteria for CS diagnosis were based on the Should we Emergently Re-vascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) Trial.1 Clinical criteria included a systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg for ≥ 30 minutes (or vasopressors to maintain systolic blood pressure [SBP] ≥ 90mmHg) and evidence of end-organ hypoperfusion. Hemodynamic criteria, when available, included estimated Fick or thermodilution cardiac index (CI) ≤ 1.8 L/min/m2 without vasopressors (or ≤ 2.2 L/min/m2 with vasopressors), and a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) ≥ 15 mmHg. We excluded patients who did not have cardiogenic shock due to AMI or HF or were transferred to another hospital within 24 hours of arrival.

Data Collection and Clinical Outcomes

The study was approved by the Inova Health System local institutional review board. Data was manually abstracted and collected via retrospective chart review of all available electronic medical records, including local databases and national registries, to obtain baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, co-morbidities at presentation, and hemodynamic parameters. In addition, data was collected regarding transfer status and clinical outcomes, including 30-day, six-month, and one-year mortality, post-discharge hospitalization, and occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE). Mortality times were calculated as time from discharge to time of death or last known follow-up. Additional variables included length of stay, discharge destination, vascular and bleeding complications, type of mechanical circulatory support (MCS), including intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP, Getinge, Wayne, NJ), Impella® (Abiomed, Danvers, MA) percutaneous ventricular assist device (pVAD), veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) utilization. Placement of temporary MCS at our institution was performed utilizing standardized vascular safety measures, including ultrasound-guided micropuncture access, pre-closure and distal perfusion catheters when indicated by final run-off angiogram of the ipsilateral femoral artery. Patients underwent comprehensive hemodynamic assessment via right heart catheterization, whenever possible and appropriate.5, 14 Lactic acid levels were measured at baseline and 24 hours following implementation of therapies. All patients were assigned a Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) CS stage based on index clinical and hemodynamic presentation.16 CardShock risk scores (age, previous heart surgery or infarction, altered mental status upon admission, lactate, glomerular filtration rate, etiology of shock [AMI-CS vs HF-CS], and left ventricular ejection fraction) and Inova Heart and Vascular Institute (IHVI) risk scores (lactate at 24 hours, vasopressor duration, cardiac power output [CPO] and pulmonary artery pulsatility [PAPi] index at 24 hours, diabetes mellitus, renal replacement therapy, and age) were determined using their established variables.9,17 Both scores have been used to prognosticate short-term mortality among patients with CS.9,17 As part of standard of care post-resuscitation clinical practice, targeted temperature management was routinely employed at our institution to mitigate the risk of neurological injury for all post-cardiac arrest patients with significant alteration in neurological function, regardless of initial rhythm or location or duration of arrest.

The primary outcome of the study was cumulative mortality at one-year following initial CS presentation. Secondary endpoints of interest included: in-hospital mortality; 30-day hospital readmission; and MACCE within one year of hospital discharge. In-hospital outcomes were defined as: 1) major bleeding, defined as a composite of the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) Type 3a, 3b, and 3c and Type 5 classification system18; 2) major vascular access complications (VARC), defined by the second Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC-II)19; and 3) renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT). Post-discharge outcomes were defined as readmission to the hospital within 30-days of discharge; mortality within one-year following discharge; MACCE, which was defined as a composite of an episode of: 1) acute decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization; 2) acute myocardial infarction; 3) cardiac arrest and 4) cerebrovascular accident (CVA) within one-year of discharge following index hospitalization for CS.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (quartiles [Q1, Q3] with interquartile range), or frequency and percent, where appropriate. Comparisons were made via Student’s t test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, one-way ANOVA, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact tests, where appropriate. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to investigate the long-term cumulative mortality rates of the patients. Mortality times were calculated as time from discharge to time of death or last known follow-up. We described effects on mortality using hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), respectively. We compared the continuous survival curves of the AMI-CS and HF-CS groups using the log-rank test. To evaluate conditional mortality at one-year, we constrained the sample to patients who survived to hospital discharge during the index CS presentation.

To model the effect of clinical predictors on long term mortality, we built a Cox proportional hazards model with the right-censored time to death as the response variable. We constructed a total of three Cox proportional hazards model for all patients, the AMI-CS subgroup, and the HF-CS subgroup. The models were adjusted for sex, age (per 5 years), diabetes mellitus, stroke, outside facility transfer, LVEF at baseline, SCAI Stage (C vs. D-E), index GFR (< 60 ml/min vs. > 60 ml/min), vasopressors at index diagnosis, cardiac arrest, and lactate at baseline. For the multivariate Cox proportional hazards models, the missing predictor variables included baseline LVEF with 8 missing records (1.5%), index GFR with 3 missing records (0.6%), and baseline lactate with 76 missing records (14.6%).

The hazard ratios (HR) for the one-year survival along with 95% confidence intervals were presented. The post discharge MACCE between the AMI-CS versus the HF-CS cohort were compared via risk ratio along with 95% confidence interval and Fisher’s exact test for comparing proportions. All analyses were performed using R (4.0.2) software for statistical computing.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

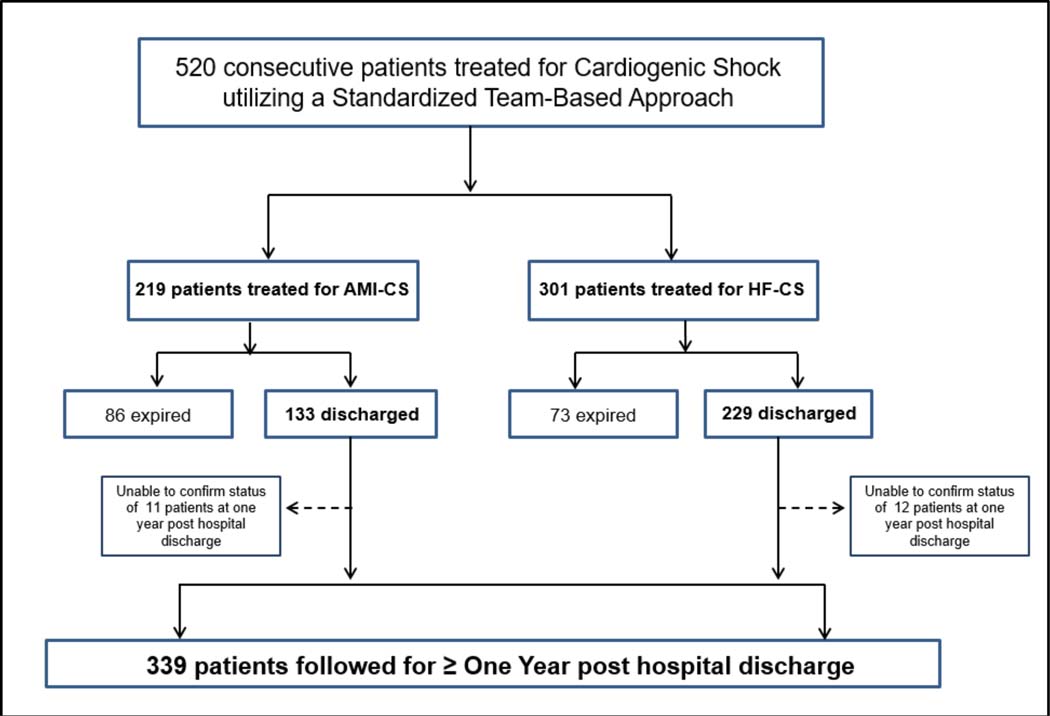

A total of 520 patients presented with CS between 2017 and 2019, of which 219 (42%) had AMI-CS and 301 (58%) had HF-CS. A total of 158 patients (30.4%) died during the index CS hospitalization. For patients who survived to hospital discharge, the median duration of follow up was 596 days (IQR 447, 871). Vital status (alive or dead) and the occurrence of MACCE at one year or longer was confirmed for 94% (339) of the 362 patients who survived to hospital discharge. Of the 23 patients (6%) for whom one year status was unable to be confirmed (11 with AMI-CS and 12 with HF-CS), 11 were known to have relocated out of state or internationally (7 with AMI-CS and 4 with HF-CS) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Flow diagram depicting the enrollment of Cardiogenic Shock patients during the study period, from initial presentation to hospital discharge and at one-year post hospital discharge, comparing patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to Heart Failure (HF-CS) to patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI-CS).

Table 1 outlines the baseline characteristics, clinical presentation, and hemodynamic profiles for patients with AMI-CS and HF-CS on admission and within the first 24 hours of presentation. The mean age was 61.5±13.5 years, 71.0% were male, 47.1% were non-White (including 22% Black), 43.7% had diabetes mellitus, and 63.1% had at least Stage 3 chronic kidney disease. Two hundred eighty-six CS patients (55% of the total) initially presented to an outside hospital and were transferred to our center for treatment. The median duration of time spent at an outside hospital prior to transfer was 18 hours 6 mins (IQR 5 hours, 43 minutes to 63 hours, 47 minutes). Of the 520 CS patients in this study, 464 (89.2%) had a right heart catheterization performed at some point during their in-hospital management, with 385 (83.0%) performed within 24 hours of CS identification.

Table 1:

Baseline and 24-hour Demographic, Clinical, and Hemodynamic Characteristics in Cardiogenic Shock Patients

| Parameter | AMI-CS N=219 | HF-CS N=301 | Total N=520 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.56 (10.63) | 58.47 (14.54) | 61.45 (13.49) | < 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.77 | |||

| Female | 62 (28.3%) | 89 (29.6%) | 151 (29.0%) | |

| Male | 157 (71.7%) | 212 (70.4%) | 369 (71.0%) | |

| BMI | 27.9 (24.5, 31.8) | 27.7 (23.8, 32.9) | 27.9 (24.2, 32.3) | 0.87 |

| Race | < 0.001 | |||

| Caucasian | 123 (56.2%) | 152 (50.5%) | 275 (52.9%) | |

| Black | 18 (8.2%) | 96 (31.9%) | 114 (21.9%) | |

| Asian | 53 (24.2%) | 30 (10.0%) | 83 (16.0%) | |

| Other | 6 (2.74%) | 7 (2.33%) | 13 (2.50%) | |

| Hispanic | 19 (8.68%) | 16 (5.32%) | 35 (6.73%) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 107 (48.9%) | 120 (39.9%) | 227 (43.7%) | 0.049 |

| Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (%) | 32.3 (14.9) | 24.9 (15.4) | 28.0 (15.6) | < 0.001 |

| Index GFR < 60 ml/min | 129 (58.9%) | 199 (66.1%) | 328 (63.1%) | 0.08 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 29 (13.2%) | 54 (17.9%) | 83 (15.9%) | 0.18 |

| Prior MI/PCI/CABG/Valve | 48 (21.9%) | 107 (35.5%) | 155 (29.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Outside Transfer | 144 (65.8%) | 142 (47.2%) | 286 (55.0%) | < 0.001 |

| PCI prior to transfer | 61 (42.4%) | 0 (0%) | 61 (21.3) | - |

| MCS prior to transfer | 68 (47.2%) | 13 (9.2%) | 81 (28.3) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressors at index diagnosis | 180 (82.2%) | 186 (61.8%) | 366 (70.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressors at 24hrs* | 137 (62.6%) | 142 (47.2%) | 279 (53.7%) | 0.35 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 77 (35.2%) | 48 (15.9%) | 125 (24.0%) | <0.001 |

| Out of hospital arrest | 26 (11.9%) | 16 (5.3%) | 42 (8.1%) | 0.01 |

| In hospital arrest | 58 (26.5%) | 34 (11.3%) | 92 (17.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Shockable Rhythm | 24 (41.4%) | 14 (41.2%) | 38 (41.3%) | 1.0 |

| Non-shockable Rhythm | 34 (58.6%) | 20 (58.8%) | 54 (58.7%) | 1.0 |

| Right Heart Catheterization | 200 (91.3%) | 264 (87.7%) | 464 (89.2%) | 0.25 |

| Baseline Hemodynamics | ||||

| CPO, W* | 0.77 (0.47) | 0.64 (0.28) | 0.69 (0.38) | 0.002 |

| PAPi* | 1.51 (1.05) | 2.14 (3.24) | 1.88 (2.57) | 0.005 |

| RA, mmHg* | 14.18 (5.98) | 15.60 (7.23) | 15.01 (6.77) | 0.03 |

| PCWP, mmHg* | 22.16 (8.79) | 25.44 (8.80) | 24.07 (8.93) | < 0.001 |

| PVR, dynes/sec/cm2* | 162.6 (123) | 270 (219) | 228 (194) | < 0.001 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 2.11 (0.98) | 1.77 (0.60) | 1.90 (0.79) | < 0.001 |

| Hemodynamics at 24hrs | ||||

| CPO, W* | 0.89 (0.32) | 0.81 (0.33) | 0.84 (0.33) | 0.02 |

| PAPi* | 2.17 (2.02) | 3.14 (3.68) | 2.75 (3.15) | 0.001 |

| RA, mmHg* | 11.8 (5.05) | 11.4 (6.40) | 11.6 (5.88) | 0.48 |

| PCWP, mmHg* | 18.3 (5.79) | 21.4 (7.65) | 20.2 (7.12) | < 0.001 |

| PVR, dynes/sec/cm2* | 126 (83.2) | 167 (99.3) | 151 (95.4) | < 0.001 |

| CI (L/min/m2) | 2.57 (0.79) | 2.38 (0.85) | 2.45 (0.83) | 0.04 |

| Baseline lactate, mg/dL* | 4.15 (3.78) | 3.49 (3.43) | 3.79 (3.61) | 0.06 |

| Lactate at 24hrs, mg/dL* | 3.30 (3.98) | 3.43 (4.38) | 3.37 (4.19) | 0.79 |

| CardShock Score | 4.89 (1.92) | 4.33 (1.77) | 4.57 (1.85) | < 0.001 |

| IHVI Shock Score | 2.83 (2.00) | 2.35 (1.79) | 2.55 (1.89) | 0.005 |

| SCAI Shock Score | 0.27 | |||

| SCAI A | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SCAI B | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SCAI C | 98 (44.8%) | 156 (51.8%) | 254 (48.9%) | |

| SCAI D | 84 (38.4%) | 103 (34.2%) | 187 (36.0%) | |

| SCAI E | 37 (16.9%) | 42 (13.9%) | 79 (15.2%) |

Missing values were excluded for % calculations

Values presented are mean±SD, frequency (percent) or median (Q1, Q3) where appropriate.

BMI= body mass index; CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CI= cardiac index; CPO = cardiac power output; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; HF = heart failure; MCS= mechanical circulatory support; MI = myocardial infarction; PAPi = pulmonary arterial pulsatility index; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PCWP = pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR= pulmonary vascular resistance; RA = right atrial; SCAI = Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention

Of the 219 AMI-CS patients, 150 (68.5%) underwent percutaneous revascularization, 123 (82.0%) for culprit single vessel disease and 27 (18.0%) for multivessel disease. An additional 30 (13.7%) patients underwent surgical revascularization and 39 (17.8%) patients were medically managed (Table 2). Of the 144 AMI-CS transfer patients, 68 (47.2%) presented with a STEMI, 72 (50%) with a NSTEMI and 4 (2.8%) with unstable angina. Sixty-one patients (42.4%) underwent PCI prior to transfer, with 44 (64.7%) of these transfer patients who presented with a STEMI. One patient underwent surgical revascularization prior to transfer. (Table 1).

Table 2.

In-Hospital Device Therapy and Outcomes in Cardiogenic Shock Patients

| Parameter | AMI-CS N=219 | HF-CS N=301 | Total N=520 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMI-CS management | ||||

| Percutaneous revascularization | 150 (68.5%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Culprit/single-vessel | 123 (82.0%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Multi-vessel | 27 (18.0%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Surgical revascularization | 30 (13.7%) | N/A | N/A | |

| Medical Management | 39 (17.8%) | N/A | N/A | |

| MCS utilization | 167 (76.3%) | 105 (34.9%) | 272 (52.3%) | < 0.001 |

| IABP | 98 (44.8%) | 34 (11.3%) | 132 (25.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Escalation from IABP | 40 (40.8%) | 10 (29.4%) | 50 (37.9%) | 0.31 |

| pVAD only | 79 (36.1%) | 43 (14.3%) | 122 (23.5%) | < 0.001 |

| VA-ECMO only | 15 (6.9%) | 19 (6.3%) | 34 (6.5%) | 0.86 |

| pVAD + VA-ECMO | 33 (15.1%) | 22 (7.3%) | 55 (10.6%) | 0.156 |

| Impella 5.0 + VA-ECMO | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (9.1%) | 2 (3.6%) | |

| Impella CP + VA-ECMO | 33 (100%) | 20 (90.9%) | 53 (96.4%) | |

| LVAD or Transplant | < 0.001 | |||

| LVAD | 5 (2.3%) | 27 (9.00%) | 32 (6.15%) | |

| Transplant | 1 (0.4%) | 13 (4.32%) | 14 (2.70%) | |

| Major Bleeding* | 57 (26.0%) | 52 (17.3%) | 109 (21.0%) | 0.02 |

| Vascular Access Complication† | 40 (18.3%) | 27 (9.0%) | 67 (12.9%) | 0.002 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 53 (24.2%) | 52 (17.3%) | 105 (20.2%) | 0.06 |

| Length of Stay, days | 13.42 (14.4) | 18.41 (17.5) | 16.31 (16.4) | < 0.001 |

| Expired Prior to Discharge | 86 (39.3%) | 72 (23.9%) | 158 (30.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Withdrawal of support | 55 (64.0%) | 51 (70.8%) | 106 (67.1%) | 0.40 |

| Cause of Death | 0.02 | |||

| Cardiac | 74 (86.1%) | 50 (69.4%) | 124 (78.5%) | |

| Non-cardiac‡ | 12 (14.0%) | 22 (30.6%) | 34 (21.5%) | |

| Discharge Destination | < 0.001 | |||

| Home | 75 (34.2%) | 153 (50.8%) | 227 (43.7%) | |

| Hospice | 5 (2.3%) | 24 (8.0%) | 29 (5.6%) | |

| Acute Rehab Facility | 24 (11.0%) | 33 (11.0%) | 57 (11.0%) | |

| Skilled Nursing Facility | 22 (10.0%) | 13 (4.3%) | 35 (6.7%) | |

| Other Medical Facility | 7 (3.2%) | 6 (2.0%) | 13 (2.5%) | |

| Expired | 86 (39.3%) | 72 (23.9%) | 158 (30.4%) |

Major bleeding = Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) 3a-c and 5

Vascular access complications = major vascular complications as described by the second Valve Academic Research Consortium

Non-cardiac causes of death: Multisystem organ failure, sepsis, anoxic brain injury, intracranial Hemorrhage with Cerebral Edema and Cerebral Herniation, GI hemorrhage, distributive shock

AMI-CS= cardiogenic shock related to acute myocardial infarction; IABP = Intra-aortic Balloon Pump; LVAD = left ventricular assist device; MCS = mechanical circulatory support; pVAD = percutaneous ventricular assist device; VA- ECMO = Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Compared to AMI-CS, patients with HF-CS were younger (58.5 vs. 65.6, p < 0.001), less likely to have diabetes (39.9% vs. 48.9%, p = 0.049), and less likely to experience cardiac arrest (15.9% vs. 35.2%, p < 0.001) either at presentation or during the index hospitalization. HF-CS patients had a lower LVEF (24.9±15.4 vs. 32.3±14.9, p < 0.001) as compared to AMI-CS patients, were less likely to require vasopressors on admission (61.8% vs. 82.2%, p < 0.001), and were less likely to present as a transfer from another institution (47.2% vs. 65.8%, p <0.001).

Of the 464 patients (200 AMI-CS vs 264 HF-CS, p=0.25), 81.5% of the AMI-CS patients underwent RHC within 24 hours of CS identification compared to 84.0% of HF-CS patients. The hemodynamic profiles differed between HF-CS and AMI-CS. HF-CS patients presented with lower CPO (0.64 vs. 0.77W, p < 0.01), higher PAPi (2.1 vs. 1.5, p < 0.01), higher RA pressure (15.6 vs. 14.2 mmHg, p = 0.03), higher PCWP (25.4 vs. 22.2 mmHg, p < 0.001), and lower cardiac index (1.8 vs. 2.1 L/min/m2, p < 0.001) at baseline, as compared to AMI-CS. Both HF-CS and AMI-CS demonstrated evidence of end-organ hypoperfusion, with elevated lactic acid levels (3.5 vs. 4.2 mg/dL, p = 0.06) on presentation. Patients with HF-CS had lower CardShock (4.3 vs. 4.9, p<0.001) and IHVI Shock scores (2.4 vs 2.8, p=0.005), but there were no significant differences noted in SCAI Shock Stages between the two cohorts.

Cardiac arrest was common with 125 patients (24.0%) having an occurrence either at presentation or during their index hospitalization. Notably, HF-CS patients were less likely to experience cardiac arrest (15.9% vs. 35.2%, p < 0.001) with fewer out-of-hospital arrests (16 [5.3%] vs. 26 [11.9%], p = 0.01) and in-hospital cardiac arrests (34 [11.3%] vs. 58 [26.5%], p < 0.001) compared to AMI-CS patients. Among those with in-hospital cardiac arrests, HF-CS patients experienced similar proportion of shockable (14 patients [41.2%] vs. 24 patients [41.4%], p = NS) vs. non-shockable rhythms (20 [58.8%] vs. 34 [58.6%], p = NS) as compared to AMI-CS patients. Duration of cardiac arrest was not recorded.

Device Utilization and Acute In-Hospital Clinical Outcomes

In-hospital MCS utilization and clinical outcomes are shown in Table 2. Of 520 patients, 272 (52.3%) received temporary MCS (tMCS). Our tMCS strategy is based on early invasive hemodynamics and serial re-assessment to delineate cardiogenic shock phenotypes (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). IABP was the most utilized tMCS device (132 patients, 25.4%) and VA-ECMO was the tMCS strategy most utilized for CS patients for whom either biventricular or RV support was required (Table 2). Compared to AMI-CS, HF-CS patients were less likely to receive any tMCS devices (34.9% vs. 76.3%, p < 0.001), including IABP (11.3% vs. 44.8%, p < 0.001) or pVAD (14.3% vs. 36.1%, p < 0.001). Of the 286 patients transferred to IHVI for CS care, 81 (28.3%) received tMCS prior to transfer, and of those, 31 (38.3%) required escalation to another tMCS device. However, HF-CS patients were more likely to receive long-term advanced HF therapies, including durable VAD (9.0% vs. 2.3%, p < 0.001) and heart transplantation (4.3% vs. 0.4%, p < 0.001). HF-CS patients experienced lower rates of in-hospital major bleeding (17.3% vs. 26.0%, p = 0.02), vascular access complications (9.0% vs. 18.3%, p < 0.01), but had a longer length of hospital stay (median 18.4 vs. 13.4 days, p < 0.001). Of the 109 (21.0%) patients who had a major bleeding complication, 24 (22.0%) received no tMCS. Of the 67 (12.9%) patients who had a vascular access complication, 17 (25.4%) received no tMCS.

In-hospital mortality was lower for HF-CS vs. AMI-CS (23.9% vs. 39.3%, p<0.001) and a lower percentage of these deaths were related to cardiac causes in HF-CS patients (69.4%, vs. 86.1%, p=0.02). The intentional withdrawal of support occurred with equal frequency in HF-CS and AMI-CS (70.8% vs. 64.0%, p = 0.40).

Post Discharge and One Year Clinical Outcomes

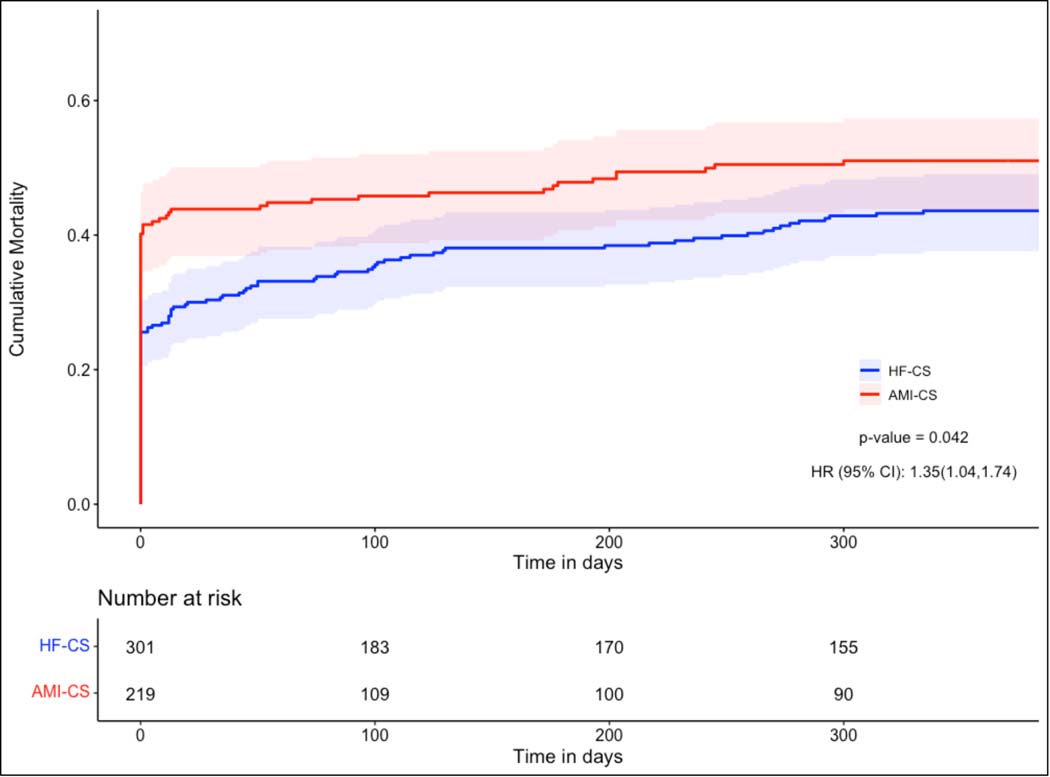

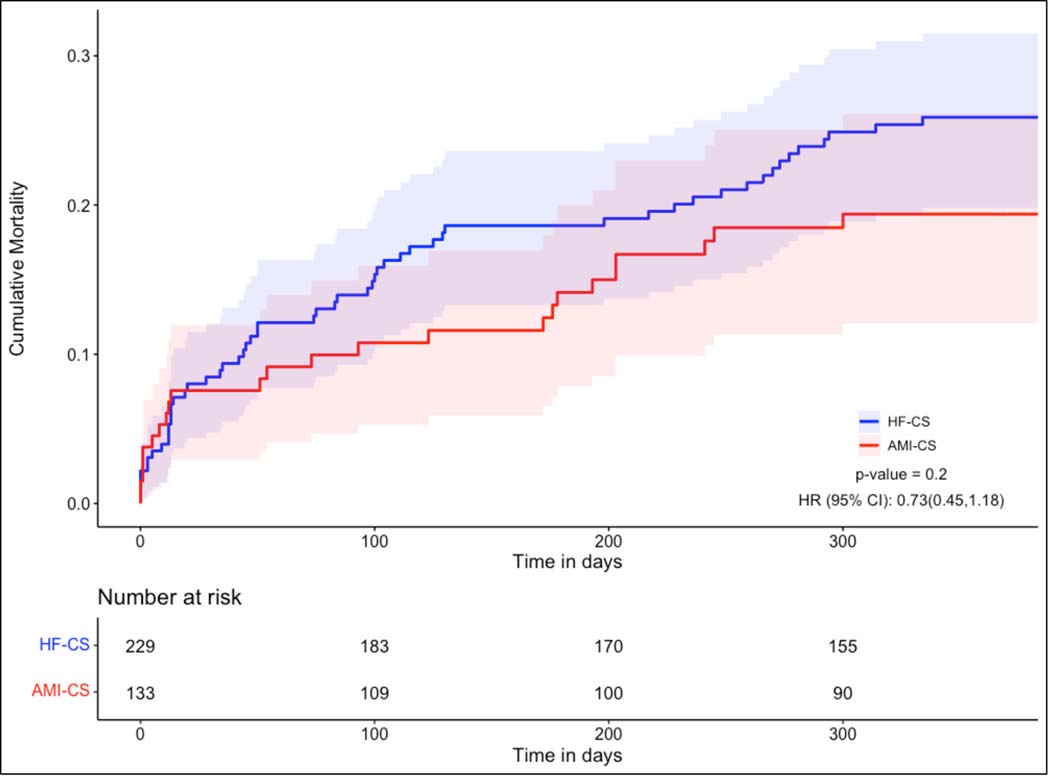

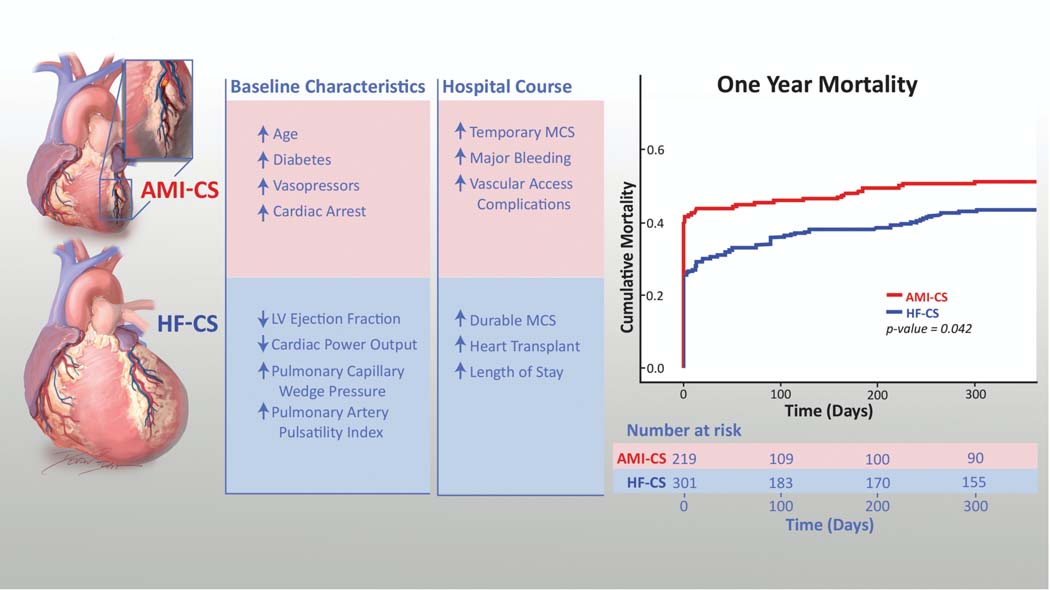

Of the 362 CS patients discharged from the hospital, at least one-year follow up was available for 339 (94%). All-cause mortality was lower in HF-CS patients at one-year (42.6% vs 52.9%, p=0.023). Kaplan Meier curves (Figure 2) depicting cumulative mortality in AMI-CS and HF-CS patients confirm significantly lower mortality in patients with HF-CS (p=0.042) with early separation of the curves. This difference was driven primarily by lower in-hospital mortality in HF-CS patients (23.9% vs. 39.3%, p<0.001) (Figure S3). We performed a separate mortality analysis on the subset of patients who survived to discharge. Conditional mortality curves and the table of patients at-risk are provided in Figure 3. For patients surviving the index CS hospitalization, there was no statistically significant difference in the mortality risk between the two CS phenotypes (p=0.20).

Figure 2: One-Year Cumulative Mortality for Patients Hospitalized for Cardiogenic Shock.

Figure depicting the Kaplan-Meier Survival curves for Cardiogenic Shock patients in the year following initial presentation, comparing cumulative mortality in patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to Heart Failure (HF-CS) to patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI-CS).

Figure 3: All-Cause Mortality Conditional on Survival to Hospital Discharge.

Figure depicting the Kaplan-Meier Survival curves for Cardiogenic Shock patients in the year following initial presentation, comparing cumulative mortality in patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to Heart Failure (HF-CS) to patients with Cardiogenic Shock related to an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI-CS), conditional on those who survived to hospital discharge.

Table 3 compares 30 day, six-month, and one-year clinical outcomes in patients surviving the index CS hospitalization. Among the 362 patients with HF-CS and AMI-CS who survived to hospital discharge, there were similarly high rates of 30-day readmission (19.5% vs. 24.5%; p=0.30), MACCE (23.3% vs. 28.8%; p=0.45) and death (19.7% vs. 23.5%; p=0.50). However, AMI-CS patients were more likely to experience recurrent AMI (6.7% vs. 0.9%, p=0.002). Analogously, HF-CS patients experienced a higher frequency of episodes of acute decompensated HF (26.2% vs. 17.3%, p=0.05). Notably, non-cardiac causes were the most common cause of 30-day readmissions in both the AMI-CS and HF-CS cohorts (61.5% vs. 57.1%, p=0.81).

Table 3.

Post Discharge Outcomes in Cardiogenic Shock Patients

| Parameter | AMI-CS N= 133 | HF-CS N= 229 | Total N=362 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-Day Mortality*,† | 10 (7.7%) | 14 (6.4%) | 24 (6.9%) | 0.67 |

| Six-Month Mortality*,† | 18 (14.4%) | 36 (16.8%) | 54 (15.9%) | 0.65 |

| One-Year Mortality*,† | 24 (19.7%) | 51 (23.5%) | 75 (22.1%) | 0.41 |

| MACCE†,‡, § | 31 (23.3%) | 66 (28.8%) | 97 (26.8%) ‡ | 0.45 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 9 (6.7%) | 2 (0.9%) | 11 (3.0%) | 0.002 |

| Acute Decompensated Heart Failure | 23 (17.3%) | 60 (26.2%) | 83 (22.9%) | 0.05 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 1 (0.8%) | 10 (4.4%) | 11(3.0%) | 0.06 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.00%) | 1(0.28%) | 0.37 |

| 30-day hospital readmission† | 26 (19.5%) | 56 (24.5%) | 82 (22.7%) | 0.30 |

| Cardiac related causes | 10 (38.5%) | 24 (42.9%) | 34 (41.5%) | 0.81 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 3 (11.5%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (3.7%) | 0.03 |

| Acute Decompensated Heart Failure | 6 (23.1%) | 19 (33.9%) | 25 (30.5%) | 0.44 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 1 (3.8%) | 5 (8.9%) | 6 (7.3%) | 0.66 |

| Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Non-cardiac related causesǁ | 16 (61.5%) | 32 (57.1%) | 48 (58.5%) | 0.81 |

Patients expired before discharge were excluded to calculate the %

Missing values were excluded for % calculations

Reflects the total number of patients who experienced a Major Adverse Cardiac and Cerebrovascular Event (MACCE) post hospital discharge (N=97); some patients experienced more than one event, for a total of 105 MACCE.

Composite MACCE encompasses acute decompensated heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and cerebrovascular accident

Non-cardiac related causes: subtherapeutic INR, post-operative pleural effusion, hypovolemia, anemia, fever, urinary tract infection, myalgias, weakness, sepsis, acute respiratory failure, renal insufficiency, fracture, wound infection, diarrhea, pneumonia, hypoglycemia, altered mental status

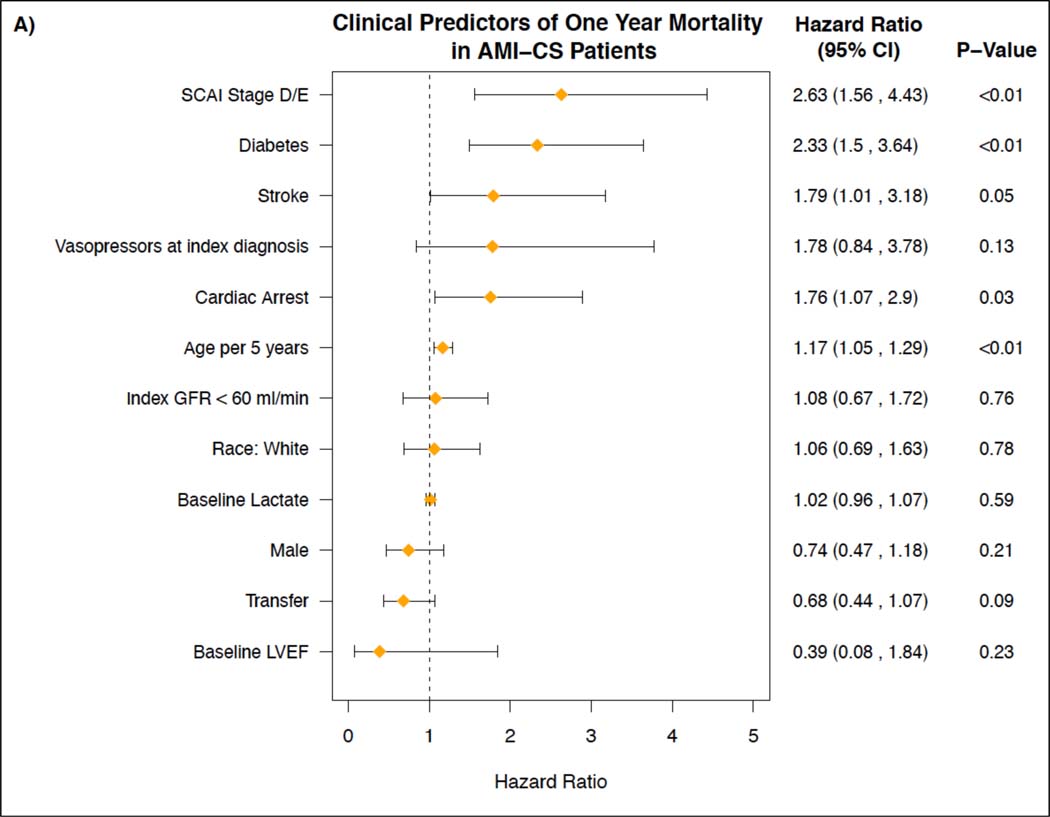

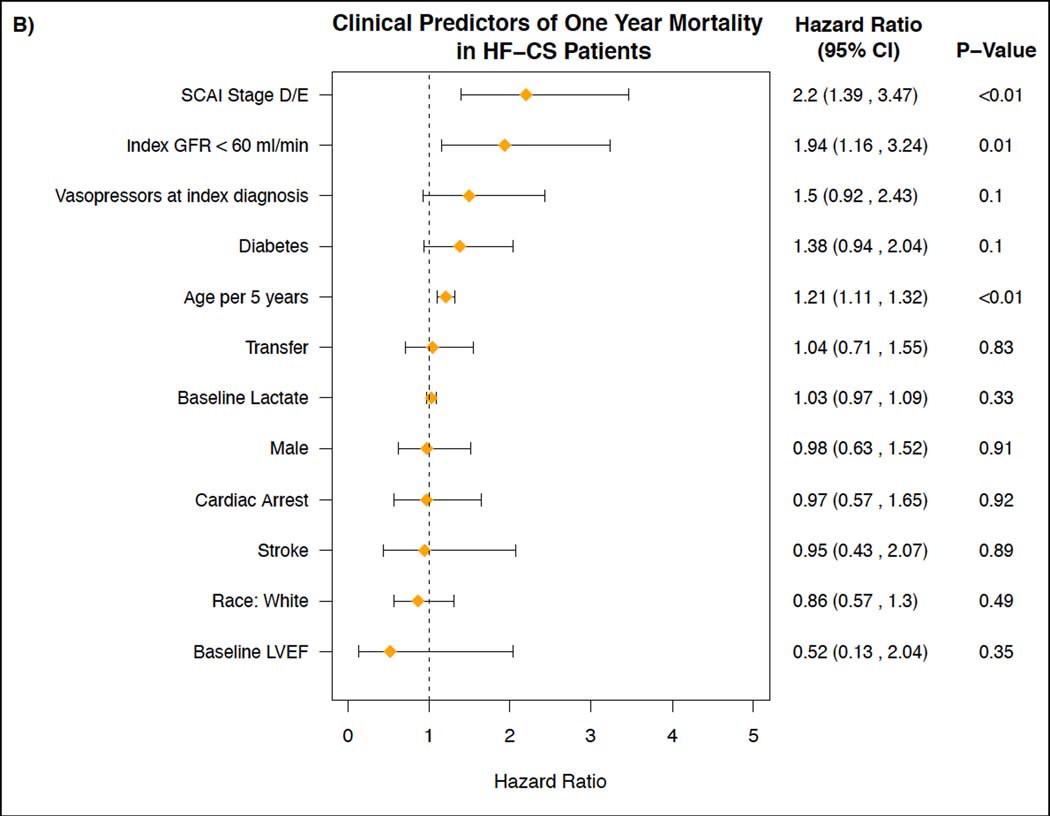

Clinical Predictors of One-Year Mortality in AMI-CS and HF-CS Patients

Figure 4 shows the independent predictors of one-year mortality in the AMI-CS subgroup and the HF-CS subgroup. In the AMI-CS group, SCAI stage D or E (HR 2.63, 95% aCI: 1.56–4.43), diabetes mellitus (HR 2.33, 95% aCI: 1.50, 3.64), age (HR 1.17 per 5 years, 95% aCI: 1.05, 1.29), and cardiac arrest (HR 1.76, 95% aCI: 1.07, 2.90) were independently associated with 1-year mortality. In the HF-CS group, SCAI stage D or E (HR 2.20, 95% aCI: 1.39, 3.47), index GFR <60 ml/min (HR 1.94, 95% aCI: 1.16, 3.24), diabetes mellitus (HR 1.38, 95% aCI: 0.94, 2.04) and age (HR 1.21 per 5 years, 95% aCI: 1.11, 1.32), were independent predictors of 1-year mortality. Figure S4 shows the independent clinical predictors of 1-year mortality for all CS patients.

Figure 4. Clinical Predictors of One-Year Mortality in AMI-CS Patients and HF-CS Patients.

Figures depicting the assessment of independent clinical predictors of one-year mortality for: A) patients treated for Cardiogenic Shock related to an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI-CS) and B) patients treated for Cardiogenic Shock related to acutely decompensated Heart Failure (HF-CS).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest single-center study to compare in-hospital and one-year outcomes of patients presenting with AMI-CS vs. HF-CS. The main findings of this study include: 1) There were substantial differences in the age, clinical presentation, hemodynamics, temporary vasopressor and MCS requirements, and clinical course of AMI-CS versus HF-CS, demonstrating the presence of two clinically distinct phenotypes (Figure 5); 2) Although patients with HF-CS experienced lower in-hospital morbidity and mortality and cumulative one-year mortality, both phenotypes of CS patients had similarly high rates of 30-day readmission and post-discharge MACCE; and 3) Whereas SCAI stage D or E, diabetes mellitus and age were independent predictors of one year mortality in both CS phenotypes, index GFR predicted mortality only for HF-CS patients and cardiac arrest was only a predictor for AMI-CS patients.

Figure 5. Comparison of Baseline Characteristics, Hospital Course, and One-Year Mortality for AMI-CS vs. HF-CS Patients.

Figure depicting the differences in presentation, acute hospital management, and one-year mortality in patients treated for Cardiogenic Shock related to an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI-CS) compared to patients treated for Cardiogenic Shock related to acutely decompensated Heart Failure (HF-CS).

Our analysis extends our prior work which showed an association between a standardized, team-based approach to the acute management of CS and improved short-term outcomes in both AMI-CS and HF-CS.9 In our initial single-center, all-comers study, HF-CS was the predominant phenotype, accounting for the majority (58%) of CS patients; however, most outcomes studies in CS have reported primarily on the outcomes of AMI-CS patients.12 The findings of our current study suggest that HF-CS and AMI-CS are two clinically distinct phenotypes. The AMI-CS cohort was older and presented with lower PAPi and higher CardShock and IHVI scores, and despite having higher CPO and lower PCWP, this CS cohort more often required temporary vasopressor and MCS support and experienced a higher rate of in-hospital cardiac arrest, MACCE, and death. In contrast, although, HF-CS patients presented with lower CPO and higher PCWP, this CS phenotype had a more favorable in-hospital course and lower utilization of vasopressors and/or temporary mechanical circulatory support. These findings suggest that the acute onset seen in the AMI-CS phenotype may be associated with less tolerance of the hemo-metabolic perturbation. In contrast, patients with HF-CS appear to have an acute on chronic presentation with a degree of chronic compensation that appears to better accommodates low cardiac output states and pulmonary congestion, with less pronounced end-organ dysfunction, malignant ventricular rhythm disturbances, and a lower risk of in-hospital death (i.e., “the walking wounded”). Nevertheless, HF-CS patients still experienced an in-hospital mortality of 25% which may benefit from more aggressive interventions to restore end-organ perfusion and reverse CS.

Consistent with prior reports, our study confirms CS to be a heterogeneous syndrome that encompasses a broad spectrum of clinical presentations and hemo-metabolic derangements.16, 20 Fifty-two percent of our CS patients were treated with temporary percutaneous support, and of those initially treated with an intra-aortic balloon pump, 40% required escalation to pVAD and/or VA-ECMO. We noted that the AMI-CS cohort had increased utilization of tMCS across all device platforms, including the use of percutaneous biventricular and cardiopulmonary support with concomitant VA-ECMO and axial flow pVADs (sometimes termed “ECPella”). However, advanced long-term HF therapies, such as durable VAD and heart transplantation, were more frequently used in HF-CS patients. In addition, while 21.0% (n=109) of all patients experienced a major bleeding complication requiring transfusion and/or vascular intervention during their acute CS treatment, these events were more frequently encountered in the AMI-CS cohort (26.0% vs 17.3%, p=0.02). The risk of bleeding in CS is multifactorial and can be precipitated by several factors, including microvascular dysfunction, coagulopathy due to end-organ malperfusion, antithrombotic pharmacotherapies, targeted temperature management, acquired von Willebrand syndrome and complications resulting from MCS devices.15

Our study is the first to compare the one-year outcomes of these two distinct CS phenotypes. We found that in-hospital outcomes, including mortality were more favorable for HF-CS compared with AMI-CS patients. Despite this, both CS phenotypes experienced a high rate of subsequent cardiovascular events. For example, following hospital discharge, nearly one third of patients with CS experience a MACCE (MI, acute HF, cardiac arrest, or CVA). Not surprisingly, AMI-CS patients experienced a higher risk of recurrent MI post discharge, which we suspect was due to a greater burden of coronary artery disease in this cohort. Interestingly, the rate of 30-day recurrent hospitalization was high for both HF-CS (25%) and AMI-CS (20%) patients and the majority of MACCE events were due to acute HF, irrespective of CS phenotype. Additionally, and importantly, the majority of rehospitalizations and MACCE were observed in the first 30 days post hospital discharge. These findings argue for the introduction of vigilant post-discharge clinical follow up in all CS patients, particularly in the first month, to detect and treat persistent pulmonary congestion and initiate and optimize guideline directed medical therapy. Studies such as the Hemodynamic Monitoring to Prevent Adverse Events following Cardiogenic Shock Trial (HALO-SHOCK; NCT 04419480) may help determine if ambulatory pulmonary artery pressure monitoring combined with medication optimization favorably impacts this risk.

A conditional mortality analysis in CS patients who survived to hospital discharge demonstrated no significant difference in the risk of death following discharge between the two CS cohorts. The observation that the Kaplan-Meier mortality curves intersected early post-discharge suggests that although the HF-CS group may be less vulnerable to mortality during the acute hospitalization phase, this group may be more vulnerable to mortality during the post-hospital discharge phase of care. This data also suggests that both survival to hospital discharge and the post discharge clinical course of CS patients are important milestones when considering the overall trajectory of these patients. Further investigation, focusing on the longer-term functional status and quality of life of survivors of both AMI-CS and HF-CS, is needed. As no specific treatment guidelines exist for managing CS survivorship, the successes of other critical illness survivorship programs, such as the THRIVE Post-ICU clinical multidisciplinary follow-up collaborative from the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the Critical and Acute Illness Recovery Organization (CAIRO) may serve as useful examples for identifying long-term morbidity (cognitive, physical, and psychological) and other sequelae of CS.21, 22

We used multivariable regression to identify independent predictors of one-year mortality in each of the CS phenotypes. In both the HF-CS and AMI-CS cohorts, SCAI stage D or E, age, and diabetes were independently associated with increased risk of one-year mortality. In the AMI-CS cohort, cardiac arrest was independently associated with increased risk of one-year mortality, which has also been shown in recent observational studies.23, 24 In the HF-CS group, baseline chronic kidney disease (with an index GFR <60 ml/min) was independently associated with increased risk of one-year mortality, underscoring the importance of the cardio-renal axis in this patient population and extending outcomes seen in heart failure patients across the spectrum of renal function.25 It should be underscored that, when appropriate, routine involvement of hospice and/or palliative care may be useful in the management of both AMI-CS and HF-CS patients, a key intervention not reported in our study.

This intermediate-term cohort study has several strengths, including the comprehensive evaluation of a real-world, diverse, high-risk CS population, use of invasive hemodynamics and high rates of clinical follow-up. As demonstrated by the elevated CardShock and IHVI Risk Scores and burden of multiple co-morbidities and multi-organ system failure, we believe that our registry is representative of real-world CS patients seen in contemporary clinical practice, particularly tertiary and quaternary centers such as ours. However, there are several limitations of this study. First, as a single-center registry, our results are influenced by institutional patient characteristics and local expertise and practice patterns in CS management. Therefore, other studies are necessary to validate our findings. Second, although a STBA was employed in the management of these patients, there was no specific prescription for temporary MCS use, device selection, and/or timing. Third, we did not specifically discriminate between de novo (i.e., acute myocarditis) versus acute-on-chronic presentations of HF-CS in this analysis.7 Fourth, we did not capture the specific cause of death or data on guideline directed medical therapies, which may help inform future investigations. Fifth, we did not employ multiple imputation or other methods to account for the limited missing data. Missing predictor variables can be interpolated using multiple imputation methods; however, multiple imputation approaches must assume that the missing covariates are missing at random.26 If the missing covariates are not missing at random, then multiple imputation may lead to biased results due to attributed imputation.27 In this study, we could not confirm that the missing values were missing at random; therefore, we chose to analyze only the complete records and report a summary of the missing covariates. Although we report on a relatively large sample size for a CS study, we cannot exclude beta error. Larger, adequately powered, multicenter studies are needed to further validate our findings and better elucidate the factors contributing to differences in the short- and long-term outcomes of patients presenting with AMI-CS and HF-CS.28

CONCLUSIONS

Key differences were observed in the acute presentation, hemodynamics, hospital course, treatment, and clinical outcomes of patients with AMI-CS vs. HF-CS. HF-CS patients were younger and less likely to receive vasopressors and/or tMCS despite lower CPO and higher PCWP. Although HF-CS patients experienced lower in-hospital and one-year cumulative mortality, both cohorts experienced high rates of post discharge MACCE, 30-day readmission and one-year mortality. These findings reveal that the vulnerable period in both AMI-CS and HF-CS extends beyond the initial shock hospitalization and warrants careful long-term follow-up. Future studies are needed to better understand the differences in these two CS phenotypes and identify interventions to improve the acute and post discharge outcomes of all CS patients.

Supplementary Material

What is New?

Key differences exist in patients with cardiogenic shock due to acute myocardial infarction (AMI-CS) as compared to CS due to acute decompensated heart failure (HF-CS) such as baseline demographics, clinical presentation, hemodynamics, vasopressor and temporary mechanical circulatory support requirements, and clinical course.

Patients with HF-CS experienced lower in-hospital morbidity and mortality and cumulative one-year mortality; however, both phenotypes of CS patients had similarly high rates of 30-day readmission and post-discharge major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in the one year after hospitalization.

Admission SCAI Stage D or E, diabetes mellitus, and age were independent predictors of one year mortality in both CS phenotypes.

What are the Clinical Implications?

Our findings support the need to introduce close post-discharge clinical follow up in all CS patients, especially in the first 30 days.

Potential treatment targets in post CS discharge care include the detection and treatment of persistent pulmonary congestion and also initiation and optimization of guideline directed medical therapy, which may favorably influence post discharge survival in this highly lethal condition.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to acknowledge the Dudley Family for their continued contributions and support of the Inova Dudley Family Center for Cardiovascular Innovation and Devon Stuart for her illustrations.

Funding: Dr. Damluji receives research funding from the Pepper Scholars Program of the Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by the National Institute on Aging P30-AG021334 and mentored patient-oriented research career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute K23-HL153771–01. Dr. Shah is funded by an NIH K23 Career Development Award 1K23HL143179. Dr. deFilippi is funded in part by 1R01HL151293, 1R01HL154768, 1UL1TR003015 (CTSA Inova PI), and 1R21AG072095 – 01.

Disclosures: Behnam N. Tehrani MD = Medtronic (consulting); Alexander G. Truesdell MD = Abiomed (consulting, speakers bureau); Palak Shah MD, MS = Grant support from Merck, Bayer, Roche, and Abbott paid to the institution, consultant for Merck, Novartis, and Procyrion; Wayne B. Batchelor, MD= Abbott (consulting, speakers bureau, research grant support), Boston Scientific (consulting, research grant support), V Wave (consulting), Medtronic (consulting). Shashank S. Desai, MD, MBA = Abbott (consulting, speaker’s bureau). All other authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AMI

Acute Myocardial Infarction

- HF

Acute Decompensated Heart Failure

- BARC

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

- CI

Cardiac Index

- CS

Cardiogenic Shock

- CPO

Cardiac Power Output

- CVA

Cerebrovascular Accident

- IHVI

Inova Heart and Vascular Institute

- IABP

Intra-aortic Balloon Pump

- LVEF

Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction

- MACCE

Major Adverse Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Events

- MCS

Mechanical Circulatory Support

- PAPi

Pulmonary Artery Pulsatility Index

- PCWP

Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure

- SCAI

Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions

- STBA

Standardized Team Based Approach

- VARC =

Valve Academic Research Consortium

- VAD

Ventricular Assist Device

Footnotes

Registration: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03378739. Clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03378739

REFERENCES

- 1.Sv Diepen, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, et al. Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e232–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiele H, Ohman EM, de Waha-Thiele S, Zeymer U and Desch S. Management of cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction: an update 2019. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2671–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damluji AA, Bandeen-Roche K, Berkower C, Boyd CM, Al-Damluji MS, Cohen MG, Forman DE, Chaudhary R, Gerstenblith G, Walston JD, Ret al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Older Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction and Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1890–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg DD, Bohula EA, Diepen Sv, Katz JN, Alviar CL, Baird-Zars VM, Barnett CF, Barsness GW, Burke JA, Cremer PC, et al. Epidemiology of Shock in Contemporary Cardiac Intensive Care Units. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2019;12:e005618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thayer KL, Zweck E, Ayouty M, Garan AR, Hernandez-Montfort J, Mahr C, Morine KJ, Newman S, Jorde L, Haywood JL, et al. Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment and Classification of In-Hospital Mortality Risk Among Patients With Cardiogenic Shock. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e007099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrage B, Dabboura S, Yan I, Hilal R, Neumann JT, Sörensen NA, Goßling A, Becher PM, Grahn H, Wagner T, et al. Application of the SCAI classification in a cohort of patients with cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96(3):E213–E219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt AS, Berg DD, Bohula EA, Alviar CL, Baird-Zars VM, Barnett CF, Burke JA, Carnicelli AP, Chaudhry S-P, Daniels LB, et al. De Novo vs Acute-on-Chronic Presentations of Heart Failure-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Insights from the Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network Registry. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2021;27:1073–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraham J, Blumer V, Burkhoff D, Pahuja M, Sinha SS, Rosner C, Vorovich E, Grafton G, Bagnola A, Hernandez-Montfort JA, et al. Heart Failure-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Management Considerations: Review of Heart Failure-Related Cardiogenic Shock. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2021;27:1126–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tehrani BN, Truesdell AG, Sherwood MW, Desai S, Tran HA, Epps KC, Singh R, Psotka M, Shah P, Cooper LB, et al. Standardized Team-Based Care for Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:1659–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee F, Hutson JH, Boodhwani M, McDonald B, So D, De Roock S, Rubens F, Stadnick E, Ruel M, Le May M, et al. Multidisciplinary Code Shock Team in Cardiogenic Shock: A Canadian Centre Experience. CJC Open. 2020;2:249–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taleb I, Koliopoulou AG, Tandar A, McKellar SH, Tonna JE, Nativi-Nicolau J, Villela MA, Welt F, Stehlik J, Gilbert EM, et al. Shock Team Approach in Refractory Cardiogenic Shock Requiring Short-Term Mechanical Circulatory Support. Circulation. 2019;140:98–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basir MB, Kapur NK, Patel K, Salam MA, Schreiber T, Kaki A, Hanson I, Almany S, Timmis S, Dixon S, et al. Improved Outcomes Associated with the use of Shock Protocols: Updates from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:1173–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger CB, Henry TD, Bates WE, Cercek B, Weaver WD and Williams DO. Development of systems of care for ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients: the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (ST-elevation myocardial infarction-receiving) hospital perspective. Circulation. 2007;116:e55–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garan AR, Kanwar M, Thayer KL, Whitehead E, Zweck E, Hernandez-Montfort J, Mahr C, Haywood JL, Harwani NM, Wencker D,et al. Complete Hemodynamic Profiling With Pulmonary Artery Catheters in Cardiogenic Shock Is Associated With Lower In-Hospital Mortality. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tehrani BN, Truesdell AG, Psotka MA, Rosner C, Singh R, Sinha SS, Damluji AA and Batchelor WB. A Standardized and Comprehensive Approach to the Management of Cardiogenic Shock. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:879–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baran DA, Grines CL, Bailey S, Burkhoff D, Hall SA, Henry TD, Hollenberg SM, Kapur NK, O’Neill W, Ornato JP, et al. SCAI clinical expert consensus statement on the classification of cardiogenic shock. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2019;94:29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A, Køber L, Tarvasmäki T, Spinar J, Parissis J, Banaszewski M, Silva-Cardoso J, Carubelli V, et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized Bleeding Definitions for Cardiovascular Clinical Trials. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es GA, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document (VARC-2). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;42:S45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saxena A, Garan AR, Kapur NK, O’Neill WW, Lindenfeld J, Pinney SP, Uriel N, Burkhoff D and Kern M. Value of Hemodynamic Monitoring in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock Undergoing Mechanical Circulatory Support. Circulation. 2020;141:1184–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert E, Boehm LM, Aparanji K, Bakhru RN, Bastin AJ, Beesley SJ, Beveridge L, Butcher BW, et al. Enablers and Barriers to Implementing ICU Follow-Up Clinics and Peer Support Groups Following Critical Illness: The Thrive Collaboratives. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1194–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiritoso R, Crouch M, Bakowski A, Gorgoraptis N and Bastin A. Follow-up for Survivors of Cardiac Critical Illness: Winning Hearts and Minds. J Card Fail. 2021;27:1148–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jentzer JC. Understanding Cardiogenic Shock Severity and Mortality Risk Assessment. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2020;13:e007568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallabhajosyula S, Jentzer JC, Prasad A, Sangaralingham LR, Kashani K, Shah ND and Dunlay SM. Epidemiology of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest complicating non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: 18-year US study. ESC Heart Failure. 2021;8:2259–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel RB, Fonarow GC, Greene SJ, Zhang S, Alhanti B, DeVore AD, Butler J, Heidenreich PA, Huang JC, Kittleson MM, et al. Kidney Function and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:330–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayati Rezvan P, Lee KJ and Simpson JA. The rise of multiple imputation: a review of the reporting and implementation of the method in medical research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM and Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. Bmj. 2009;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrow DA. Closing the Gap: Insights into the Epidemiology of Heart Failure Care from the Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network. J Card Fail. 2021;27:1146–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.