Abstract

Background:

Once considered primarily a disorder of lipid deposition, coronary artery disease is an incurable, life-threatening disease that is now also characterized by chronic inflammation notable for the build-up of atherosclerotic plaques containing immune cells in various states of activation and differentiation. Understanding how these immune cells contribute to disease progression may lead to the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Methods:

We used single cell technology and in vitro assays to interrogate the immune microenvironment of human coronary atherosclerotic plaque at different stages of maturity.

Results:

In addition to macrophages, we found a high proportion of αβ T cells in the coronary plaques. Most of these T cells lack high expression of CCR7 and L-selectin, indicating that they are primarily “antigen-experienced,” memory cells. Notably, nearly one-third of these cells express the HLA-DRA surface marker, signifying activation through their T cell-antigen receptors (TCRs). Consistent with this, TCR repertoire analysis confirmed the presence of activated αβ T cells (CD4 << CD8), exhibiting clonal expansion of specific TCRs. Interestingly, we found that these plaque T cells had TCRs specific for influenza, coronavirus, and other viral epitopes, which share sequence homologies to proteins found on smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, suggesting potential auto-immune mediated T cell activation in the absence of active infection. To better understand the potential function of these activated plaque T cells, we then interrogated their transcriptome at the single cell level. Of the 3 T cell phenotypic clusters with the highest expression of the activation marker HLA-DRA identified by the Seurat algorithm, two clusters express a proinflammatory and cytolytic signature characteristic of CD8 cells, while the other expresses amphiregulin, which promotes smooth muscle cell proliferation and fibrosis, and, thus, contributes to plaque progression.

Conclusion:

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that plaque T cells are clonally expanded potentially by antigen engagement, are potentially reactive to self-epitopes, and may interact with smooth muscle cells and macrophages in the plaque microenvironment.

Keywords: Inflammation, Ischemia, Translational Studies, Vascular Biology

One paragraph summary

Although recent studies using single cell RNA sequencing have characterized T cells within atherosclerotic plaques, these analysis have been limited to murine aortic lesions and advanced human carotid plaques. While T cell clones have been defined in the blood of patients with atherosclerosis, the plaque T cell repertoire has yet to be analyzed. Here, we provide the first comprehensive map of the human coronary plaque T cell repertoire and its transcriptome across the disease spectrum. We demonstrate that T cell effector memory clusters predominate, express activation markers, and are clonally expanded, most strikingly in the CD8+ T cell subset where clonality tracks with disease progression. Interestingly, plaque residing T cells display specificity to viruses including influenza and SARS-CoV-2 and cross-react with vascular proteins, providing preliminary evidence that T cell mediated auto-immunity may contribute mechanistically to viral-associated thrombotic complications. Finally, analysis of the plaque transcriptome reveals T cell subpopulations may interact with vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) through the release of the cytokine amphiregulin, inducing the proliferation of smooth muscle cells and promoting the formation of irreversible plaques.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease (CAD), a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by atherosclerotic plaque build-up, can cause ischemia, heart attack and even death. Recent studies using single cell transcriptomics have shown that the atherosclerotic plaque contains distinct subpopulations of non-immune cells and immune cells in various states of differentiation and activation.1,2 Nevertheless, how cells within the plaque interact with each other as well as the tissue microenvironment to contribute to plaque maturity and possible rupture remains elusive. Understanding these dynamics is especially critical considering reports of vascular thrombosis and myocarditis associated with viruses including influenza and SARS-Cov-2, and their associated vaccines, a complication that may be mediated by cross reactivity between viral antigens and self-peptides.3

To advance our knowledge of how immune cells can contribute to coronary plaque development and rupture, we profile the immune landscape of plaques at different states of maturity using single cell transcriptomics. Finding an abundance of T cells, which are distinct in their possession of immune memory, we focus our analysis on the diverse phenotypes and receptor repertoire of this cell subset. We use these data to: 1) characterize the T cell transcriptome across the different stages of plaque progression; 2) compare the T cell repertoire by arterial location and by disease phenotype; 3) identify T cell epitopes and T cell receptor (TCR) motifs shared across patients, some of which were found to have viral specificities to Flu, EBV, and conserved coronavirus epitopes; 4) demonstrate nucleotide and protein sequence homologies between plaque T cell viral epitopes and self-proteins found ubiquitously and, specifically, localized to the heart and vasculature and confirm T cell cross reactivity in vitro; 5) define cytokines that interact with the plaque environment, and 6) map a possible ligand receptor relationship between T cells and smooth muscle cells and macrophages within the plaque.

METHODS

Cohort description

Human coronary arteries and peripheral blood were collected from 35 patients who were consecutively recruited. Tables S1–4 and Figure S1A summarize the relevant donor demographics and clinical characteristics.

Sample collection and processing

Blood and coronary samples were collected from donors. Individual plaques were categorized based on criteria established by the American Heart Association (Figure S1B, Table S5). 4 Assays were performed as detailed in Table S6. Details provided in the Supplement.

Flow cytometry staining and single cell sorting of peripheral blood and plaque cells

Flow cytometry and single cell sorting were performed by standard protocols, which are detailed in the Supplement.

scRNA-seq analysis, data processing and clustering

All scRNA-seq analysis were performed using the standard protocols.5–6 Using a computational framework for the annotation of scRNA-seq by reference to bulk transcriptomes (single R),7 the clusters containing T-cells were identified by comparing each clusters’ transcriptomic signature to purified immune subsets in the following five cell atlases: 1) Blueprint Encode,8 2) Database of Immune Cell Expression,9 3) Human Primary Cell Atlas,10 4) Novershtern,6 and 5) Monaco Immune Data.11 Details provided in the Supplement.

Differential expression analysis

All differential expression analyses were performed using standard protocols. Details provided in the Supplement.

Single cell TCR sequencing and phenotyping

Single cell TCR sequencing and phenotyping were performed using standard protocols.12 Details provided in the Supplement.

Bulk sequencing and analysis of peripheral blood T cells

Total RNA extraction, library preparation and QC were done according to previously described protocols.13,14 Details provided in the Supplement.

Grouping of Lymphocyte Interactions by Paratope Hotspots (GLIPH2) analysis

To identify TCR specificity groups, GLIPH2 analysis was carried out as described previously.15,16 Details provided in the Supplement.

Determination of viral and non-viral specificities of TCR sequences

We compared each clonotype from our data against sequences with known specificities from publicly available databases, including VDJdb,17 McPAS-TCR,18 TBAdb,19 10x Genomics (https://www.10xgenomics.com), as well as the immune medicine platform managed by Adaptive Biotechnologies (https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/immuneaccess), and an internal database. We defined matches as those with identical CDR3β regions and HLA alleles, unless otherwise specified. Finally, we used Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) to identify structural similarities between our TCR epitopes and self-epitopes.

Expression of TCRs by lentiviral transduction

Lentiviral transduction was performed using standard protocols. Details provided in the Supplement.

T cell stimulation assays

T cell stimulation assays were performed as previously described.20 Details provided in the Supplement.

In vitro stimulation of coronary artery smooth muscle cells with amphiregulin

Coronary artery smooth muscles (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) were seeded in 6 well plates (4×104 cells) with smooth muscle cell growth medium-2 (SmGM-2; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). One day after plating, cells were then treated amphiregulin, AREG (50 ng/ml or 100 ng/ml) for three days. Wells without added AREG were used as control. RNA was extracted and sent for bulk sequencing.

Statistical analysis

The statistical tests performed are stated for each figure. All statistical analyses were performed using either GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA) or SciPy stat library (release 1.3.1; https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/index.html). Details provided in the Supplement.

Data availability

scRNA-seq data is available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) data repository GSE131778 and GSE196943. Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

RESULTS

Study cohort includes donors spanning all clinical stages with a diverse range of plaque phenotypes

Our cohort consisted of 35 living donors with and without a history of heart attack, including patients with no visible disease, non-obstructive disease, and obstructive disease defined by cardiovascular imaging tests (Figure 1A, Figure S1A, Table S1).

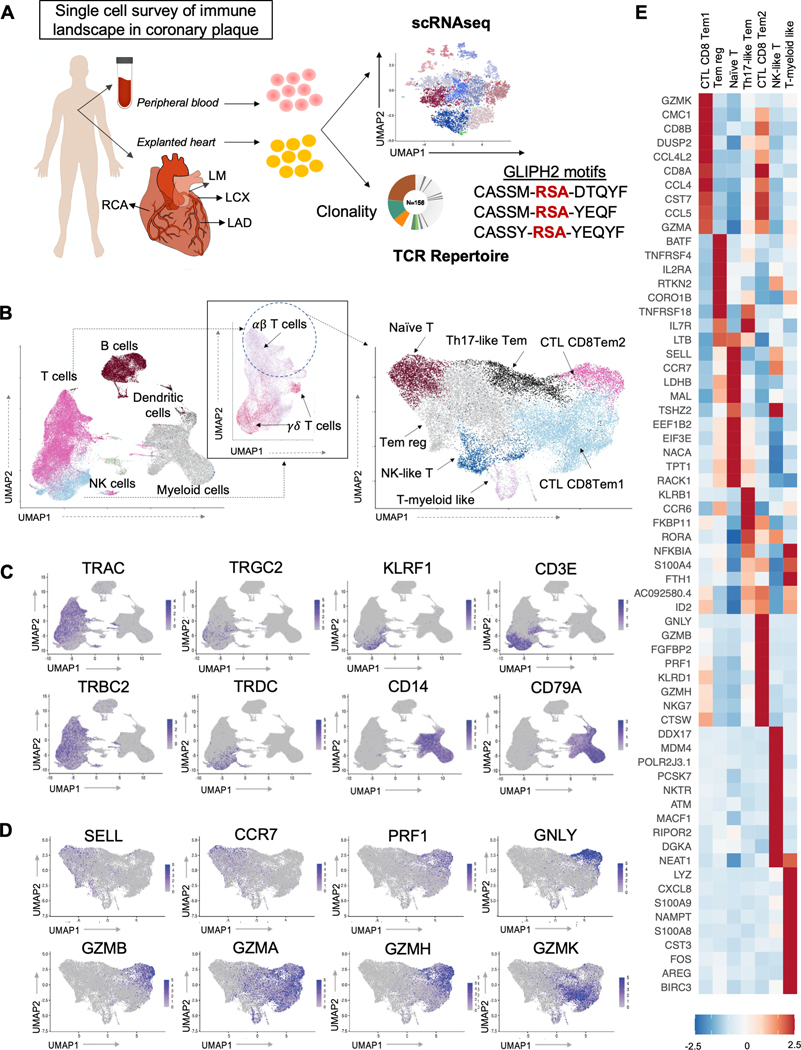

Figure 1. Antigen-experienced T cells predominate in the plaque immune landscape.

(A) Schematic representation of the experimental design. Immune cells were isolated from peripheral blood and atherosclerotic plaques of the major coronary arteries (LM = Left Main, LAD = Left Anterior Descending, LCX = Left Circumflex, RCA = Right Coronary Artery) of 35 donors. Samples were then used for flow cytometry (N=20), single cell transcriptomic analysis (N=12) and/or T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire profiling (N=20 for scTCR-seq and N=7 for bulkTCR-seq). Clustering and pathway analyses of gene expression profiles were used to identify changes in T cell phenotype, functions, and signaling mechanisms that accompany disease progression. The TCR repertoire was analyzed for clonal diversity, clone size, and complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) motif enrichment (using GLIPH), and their association with pathological disease stages. To explore antigenic specificities, TCR sequences from our data were compared to sequences with known specificities from public and private databases. Selected TCR sequences were expressed as transfectants to confirm antigen-specificity. (B) Cluster analysis. Plaque immune cells (left) and the T cell subset from the plaque transcriptome 9(UMAP) dimensionality reduction of the scRNA-seq data and colored by cluster assignment. (C) 2D visualization of the average expression of selected gene markers defining each immune cluster. (D) 2D visualization of the average expression of selected gene markers defining each T cell cluster. (E) Heatmap for expression (normalized, z-scored) of selected marker genes (rows) between cells belonging to different clusters (columns). Color scale indicates fold change.

Because CAD is characterized by distinct disease stages that can be contained within the same artery of the same individual, in some instances, we isolated individual plaques from the three major coronary arteries of individual donors. Our analysis included coronary atherosclerotic plaques with a range of phenotypes as defined in the methods section (Table S5).

Coronary plaque immune landscape reveals a large population of antigen-experienced activated T cells

We first performed an unbiased survey of the immune landscape in coronary plaque using single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on different arterial plaques with a range of disease severities obtained from 12 donors (Table S1, Table S5). We identified homogenous cell groups that mapped across 7 broad immune cell lineages (Figure 1B–C). As expected and consistent with the literature, atherosclerotic plaques contain a high proportion of myeloid cells, which have been shown to engulf lipid to form foamy macrophages, recruit other immune cells into the inflamed area, secrete proteinases that increase plaque instability, and promote smooth muscle survival and proliferation in plaques.

We also observed large numbers of T cells in analysis by immunohistochemistry, scRNA-seq, and flow cytometry (Online Supplement; Figure S1C; Figure S2). Unlike macrophages, T cells have immune memory and become activated through specific interaction with previously encountered antigens to promote ongoing inflammation. To further interrogate the role of T cells in the atherosclerotic plaque, we segregated T cells from the other immune subsets using techniques as previously described.21 We first excluded doublets (Figure S3, Table S7), then determined the differentiation and activation states of plaque T cells, focusing our cells found in atherosclerotic plaque. We focused our analysis on αβ T cells rather than γδ T cells given their larger predominance in plaques and dependence on immune memory. This resulted in 23,618 QC αβ T cells in plaque available for analysis. Consistent with studies in carotid plaque,1,2 the majority of plaque T cells expressed a memory effector phenotype (e.g., lack of expression of SELL and CCR7) (Figure S1C), including two cytolytic CD8 T effector memory cells (CD8 CTL Tem1 and CD8CTL Tem2), one CD4 Tem cluster (TH17-like Tem), a cluster of NK-like T cells (NK-like T), a cluster of regulatory memory T cells (Tem reg), and a cluster of T-myeloid like cells. We also found one cluster of Naïve-like T cells (Figure 1B,D–E, Online Supplement, Figure S3).22 These T cell subsets, especially the CD8 clusters, also express interferon gamma (IFNG), a pro-inflammatory cytokine whose role has been well described in atherosclerosis (Figure S4). Importantly, despite the high diversity in the T cell landscape in donors with CAD, data from multiple patients and all plaque phenotypes contributed to the definition of each cluster (Figure S3D, Table S8), suggesting that a robust regulatory process controlling T cell states within atherosclerotic plaques is shared among patients across the four stages of plaque maturation.

Because memory T cells are antigen experienced and able to proliferate rapidly, execute effector functions, and secrete cytokines upon antigen re-encounter, we then asked whether these memory T cells were in an activated state, suggesting that they may be contributing to ongoing inflammation within the plaque. Using HLA-DRA expression, a known marker of T cell activation, we found that patient samples contained on average 29.5% ± 9.7% of activated plaque cells (Figure S5A–E). Pathways enriched in activated (HLA-DRA+) vs. non-activated (HLA-DRA-) plaque T cells included those involved in antigen processing and presentation and TCR receptor signaling (Figure S5E), suggesting T cell activation is potentially mediated by engagement of T cells with antigens via interaction of their receptor with the major histocompatibility (MHC)-peptide complex.

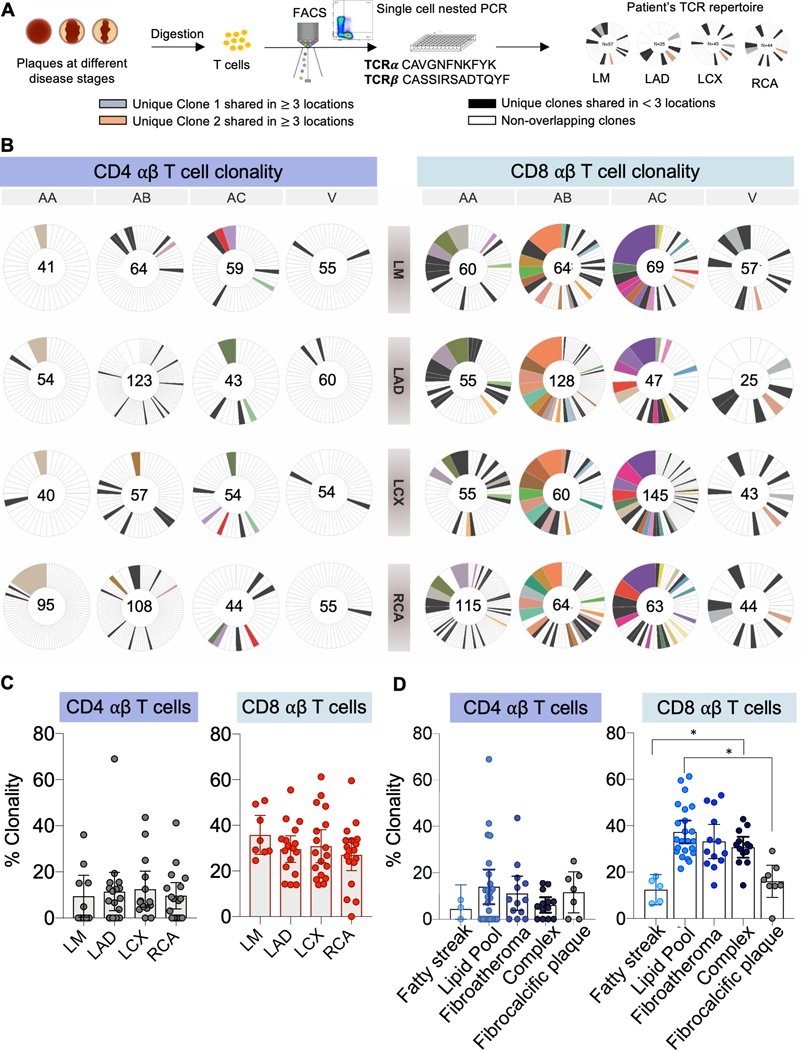

Coronary plaque TCR repertoire displays clonal expansion that tracks with disease stage

When T cells engage their cognate antigen-peptide-MHC complex, they become activated and clonally expand. To confirm results from our scRNAseq analysis and determine the potential identity of the antigenic peptide that may activate plaque T cells, we performed single-cell TCR sequencing using target-seq technology of CD4 and CD8 T cells sorted by FACS from the main coronary arterial locations of 20 donors (Online Supplement, Figure S2A).12 A T cell clone was defined by the presence of identical αβ pairs, which allowed us to measure clonal expansion and track the presence of specific clones across different arterial locations. We found clonal expansion in both the CD4 and CD8 αβ T cell subsets, with greater expansion in the latter population (Figure 2A–B, Figure S6A–C). We found no association between TCR clonality and the site of plaque development (Figure 2C). Notably, some clones were shared across multiple arterial segments (Figure 2B). Next, we explored the relationship between TCR clonality and pathological disease stages. Although we found no association between CD4 T cell clonal diversity and plaque progression, CD8 T cells showed an inverted V-shaped clonality. Initially low in fatty streaks, clonality increased with lipid deposition and plaque maturation, then declined significantly in fibrocalcific plaques (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Clonally expanded T cells are shared across arterial segments and track with disease stage.

(A) Mapping TCR clonality of coronary plaques at various stages of maturity. T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire profiling was performed in 20 donors. (B) Representative pie charts (N=4) showing clonal expansion of paired CDR3α/β sequences obtained by single cell analysis of CD4 and CD8 T cells in atherosclerotic plaques by arterial segment. Each color across all pie charts for a donor represents a unique clonotype, and the area of each pie is proportional to the clone size. Within each pie chart, individual clonotypes were colored if they appeared in 3 or more locations. Clonotypes that did not meet this criterion but had an overlap in at least one other location were colored black. The total number of single cell sequences obtained for each sample is shown in the center of the pie charts. (C) Clonality of plaque CD4 and CD8 T cells based on coronary arterial segment. One way ANOVA P value = 9.23×10−1 (not significant) for CD4 and One Way ANOVA P value = 8.76×10−1 (not significant) for CD8. (D) Clonality of plaque CD4 and CD8 T cells measured across pathological disease stages. One way ANOVA P value = 9.10×10−1 (not significant) for CD4. One Way ANOVA P value = 1.34×10−7 for CD8. Paired t test P values adjusted for 10 comparisons by the Tukey method shown to compare differences in CD8 clonality across severity groups (Fatty streak vs. Lipid-pool, adjusted P= 1.00×10−4; Fatty streak vs. Fibroatheroma, adjusted P= 3.70×10−2; Fatty streak vs Complex, adjusted P=5.80×10−3); Fibrocalcific vs. Lipid-pool, adjusted P=1.52×10−2; Fibrocalcific vs. Fibroatheroma, adjusted P=2.10×10−2; Fibrocalcific vs. Complex, adjusted P=5.00×10−4). Clonality is calculated as the proportion that the multiplets occupy in the total repertoire per sample. Mean and error bars representing the 95% confidence intervals are shown for all comparisons. *: P<0.05.

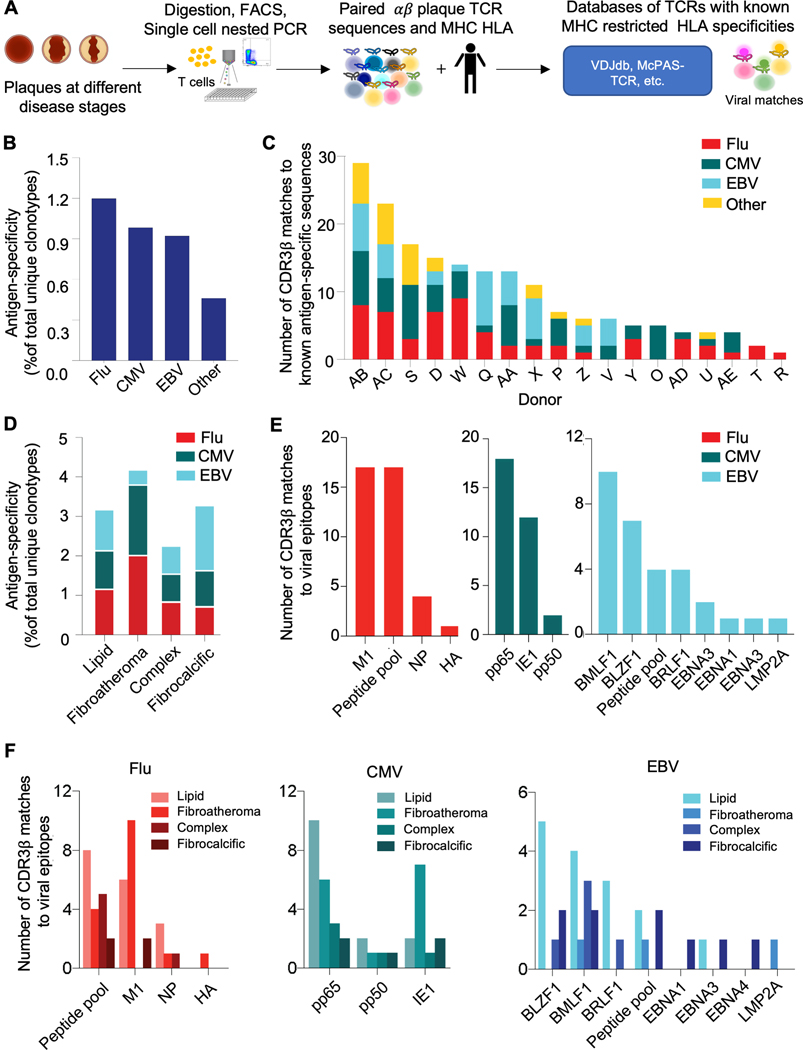

Coronary plaque CD8 αβ T cells are specific to Flu, CMV and EBV

To identify the antigens that plaque T cells might be recognizing, we first compared each clonotype from our data against TCR databases with known specificities. We chose to focus on MHC-class I restricted antigens based on the above findings as summarized here: 1) a higher proportion of CD8 T cells express the activation marker HLA-DRA, 2) plaque-derived CD8 T cells show greater clonal expansion than CD4 T cells, and 3) CD8 T cell clonality associates with disease progression. We curated a total of 55,170 unique MHC-class I restricted TCRs into a database and applied a matching-criteria that required CDR3β and HLA identity (Table S2). Of 3,251 plaque-derived unique TCR sequences, we found 116 (3.57%) identical matches for plaque (Figure 3A–B, Table S9) to Flu, CMV and EBV. These matching clonotypes were found in 18 of the 20 donors analyzed (Figure 3C). Notably, a higher proportion of clonal than nonclonal CD8 T cells displayed viral specificities (0.99% [44/9488] vs. 0.46% [29/2918], Z statistic −3.3, P=8.10×104) calculated as a percentage of matched singleton or clonotypes divided by the total singletons or clonotypes in our plaque TCR repertoire, supporting the contribution of viral specific T cell activation in ongoing inflammation associated with atherosclerosis (Table S10).

Figure 3. Flu, CMV and EBV specificities are observed in plaque CD8 T cells, with the highest proportion in fibroatheromas.

(A) Diagram of steps for matching the TCR plaque repertoire to databases of TCRs with known MHC restricted HLA specificities to identify candidate antigen epitopes. Data from 20 donors was included in the analysis. (B) Clonotypes from our data were matched against a compiled database of known antigen specificities, including sequences from public databases (e.g., VDJdb, McPAS-TCR, TBAdb, 10X Genomics), and an internally generated Flu database. The matching criteria required CDR3β and HLA identity. The fraction of matching clonotypes in plaque showing specificity to influenza (FLU), cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and other antigens is shown. (C) The prevalence of viral-antigen-specific T cells (identified in B) by donor is shown (18 out of 20 donors showed matches). (D) The prevalence of viral-antigen-specific T cells (identified in B) across plaque disease phenotypes. (E) The number of FLU, CMV, and EBV epitope specificities among matching clonotypes in plaque. (F) The number of FLU, CMV, and EBV epitope specificities among matching clonotypes across plaque disease phenotypes.

Fibroatheromas, a progressive lesion, contains the highest proportion of viral specific T cells

We further investigated the relationship between virus-specific T cells and pathological disease stages and found that, of the four disease categories, fibroatheroma, a lesion that marks the development of irreversible fibrosis and can be a precursor to plaque rupture, had the highest prevalence of viral matching clonotypes (Figure 3D). This observation is particularly interesting in view of the mounting evidence in support of a significant role for Flu in triggering plaque rupture in murine23 and human studies.24 In humans, in vitro stimulation and proliferation assays using T cells isolated from symptomatic carotid plaques have shown responsiveness to Flu as well as EBV, but in a predominantly MHC-class II restricted manner.25,26 Our analysis showed that coronary plaque CD8 T cells were specific for various Flu, CMV, and EBV epitopes, with Flu-M1, CMV-pp65, and EBV-BMLF1 being the most prevalent (Figure 3E). Notably, the Flu-M1 clonotypes were the most abundant in the fibroatheromatous plaques (Figure 3F).

Flu and EBV CDR3β motifs in plaques are shared across most patients, suggesting common antigen-epitopes activating TCRs

In addition to identifying TCR matches to known clonotypes, the antigen-specific repertoire can be made more manageable by tools like GLIPH,15 which efficiently clusters TCRs with shared specificities based on similarities in complementarity-determining region 3 beta (CDR3β), a region of the TCR that has been shown to have the highest number of binding touch points to the antigen epitope (Figure S7). Using GLIPH2 (an improved version of GLIPH),15,16 we identified 7 CDR3β motifs enriched in plaque compared to blood (Table S11), found that 86% of these motifs included viral antigen-specific TCRs most enriched in the fiboratheromatous stage, and observed that these motifs were shared across the majority of donors with a disproportionately higher sharing of Flu- and EBV-specific T cell clusters compared to CMV (Please see the Supplement for details). Although both CMV and EBV show high seropositivity and can survive latently for years, these viruses rarely cause acute debilitating infections. In contrast, influenza can cause severe respiratory infections and elicit strong T cell and antibody responses, which can potentially increase the risk of coronary plaque rupture. Nevertheless, because the increased prevalence of cross-reactive Flu-M1-specific CD8 T cells has been associated with lymphoproliferation and increased severity of EBV-related mononucleosis,27,28 these viral-specific T cells could also have concerted effects on plaque disease pathology although this warrants further investigation.

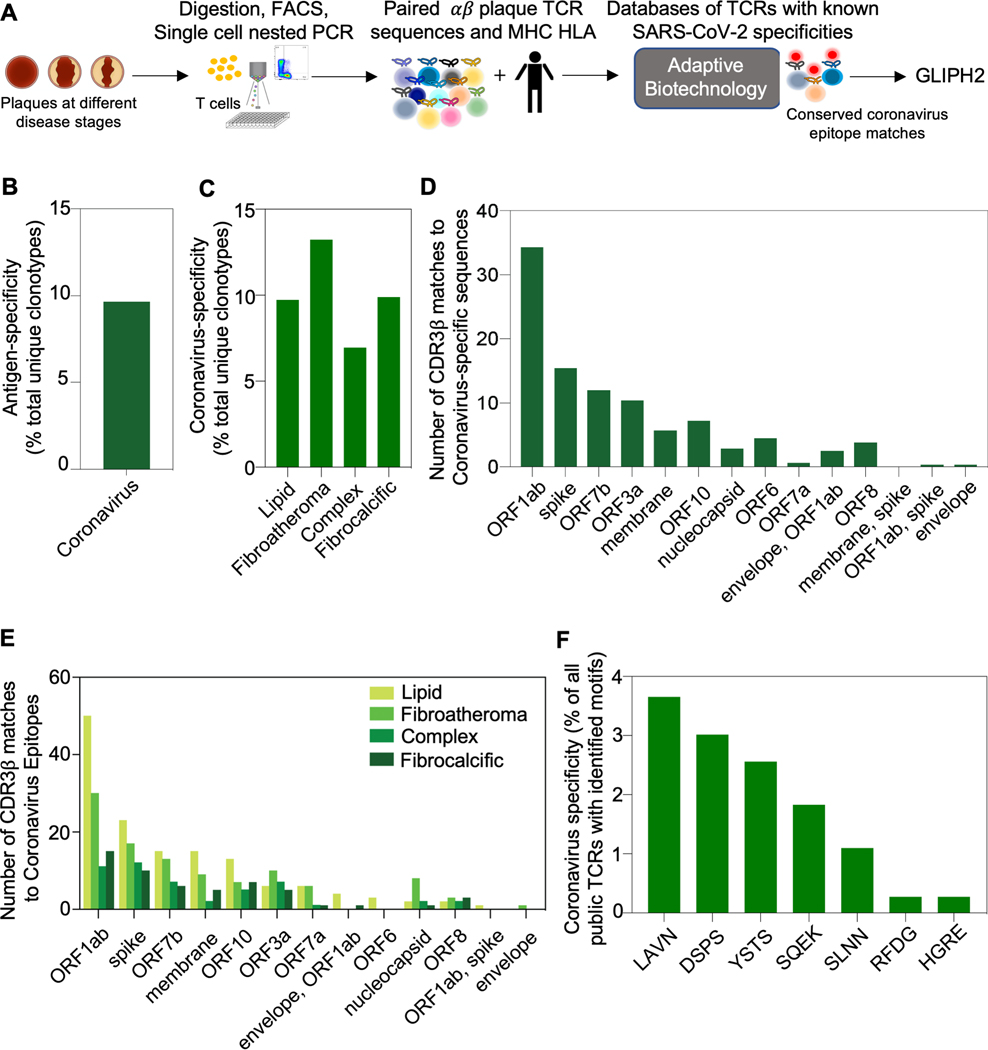

Progressive plaque phenotypes also contain T cells with specificities to conserved coronavirus epitopes

Because of the recent associations between COVID-19 and cardiovascular complications (e.g., vascular thrombosis and myocarditis),29 we further extended our analysis to an MHC-class I restricted SARS-CoV2-specific, publicly available TCR database (Adaptive Biotechnologies), which included 136,463 unique CDR3β sequences. Because of the data on HLA information was not available in this database, we could not map TCRs to specific HLA alleles and, therefore, we performed this analysis separately. Although these samples were collected before the epidemic, we also included this analysis because cross reactivity between SARS-CoV2 and other coronaviruses including those that cause the common cold have been reported.30,31,32 We discovered 9.6% of the plaque repertoire showed identical CDR3β matches (with at least one shared HLA-allele between the donors of our cohort and the database) (Figure 4A–B, Table S12). We also investigated the relationship between coronavirus-specific T cells and pathological disease stages and found that, of the four disease categories, fibroatheroma, which is characterized as a progressive and at-risk lesion, had the highest prevalence of matching clonotypes (Figure 4C). Moreover, our analysis showed that coronary plaque CD8 T cells were specific for conserved coronavirus epitopes including SARS-CoV-2 with SARS-CoV-2-ORF1ab-specific and the spike glycoprotein-specific cells being the most prevalent, especially in the early stages of disease (Figure 4D–E). Finally, our GLIPH motif analysis revealed that coronavirus-specific CDR3β sequences, which was not restricted by HLA-matching, contained motifs shared by viruses (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. Conserved coronavirus epitope specificities and CDR3β motifs are found in coronary plaque with the highest fraction in the fibroatheroma stage.

(A) Matching the TCR plaque repertoire to a publicly available databases of TCRs with known specificities to SARS-CoV-2 (Adaptive Biotechnologies resources). Because the database is not restricted by MHC HLA type, the matching criteria required CDR3β identity only. Data from 20 donors was included in the analysis. (B) The fraction of matching clonotypes in plaque showing specificity to coronavirus. (C) The prevalence of viral-antigen-specific T cells (identified in B) across plaque disease phenotypes. (D) The number of conserved coronavirus epitope specificities among matching clonotypes in plaque. (E) The number of coronavirus epitope specificities among matching clonotypes across plaque disease phenotypes. (F) Publicly available CDR3β sequences with known SARS-CoV-2 specificities were analyzed using GLIPH2 for the presence of donor-derived plaque-motifs.

Plaque T cell antigenic epitopes share sequence identity with vascular proteins

Our finding that plaque T cells display viral specificities is intriguing, especially considering the reports of plaque rupture and myocarditis in healthy individuals receiving the COVID-19 vaccine and in patients infected with Flu and SARS-CoV-2 who may or may not have known cardiovascular co-morbidities or even symptoms associated with viral infection.24,29,33 Because these patients are not actively infected based on serological testing (Table S3), they are not producing viral antigens. This raises the question of how T cells specific to virus are activated within the plaque and suggests a potential cross-reactivity of viral epitopes with self-antigens mediating tissue damage, which is otherwise known as molecular mimicry. Although molecular mimicry has been described as a means by which viruses such as Flu or EBV initiate autoimmune diseases,3 its role in atherosclerosis remains unclear.

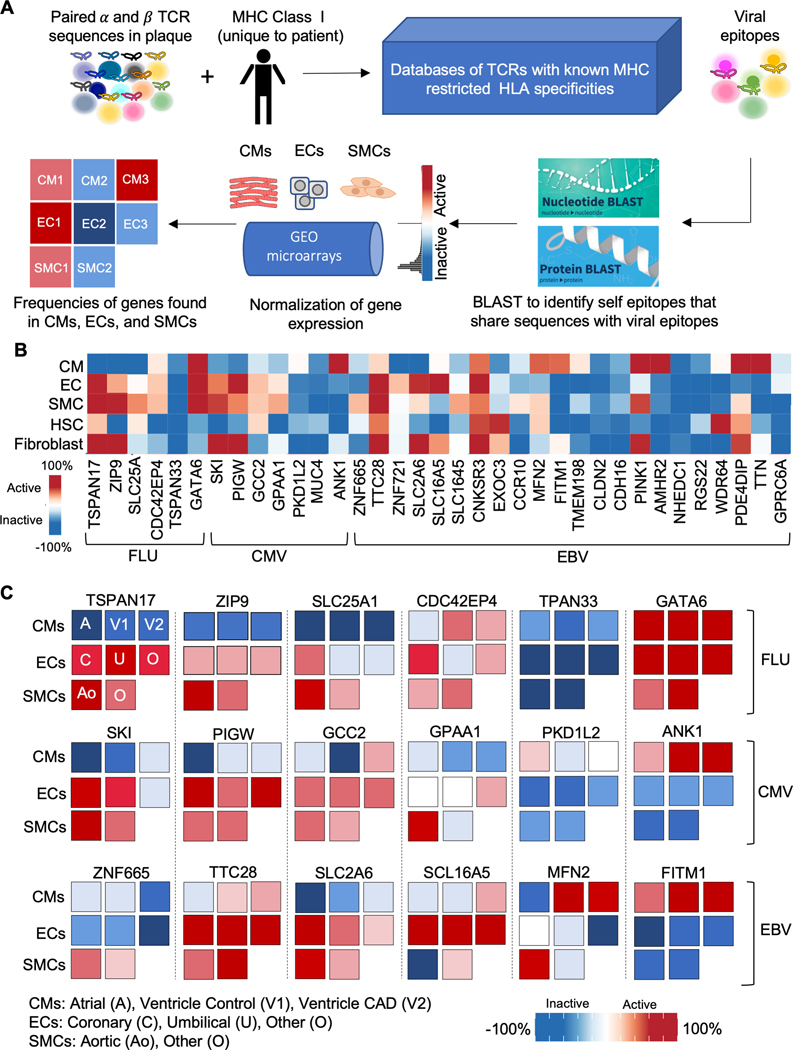

To explore whether molecular mimicry could play a role in atherosclerosis, we determined whether the viral epitopes identified in our study shared similar amino acid and nucleotide sequences with self-epitopes, especially those most abundant in the cardiovascular system. Using the BLAST (basic local alignment search tool), we performed an unbiased survey of proteins that shared similar sequences to our viral epitope matches. Indeed, we found that our viral TCR epitopes shared similar sequences with those found on self-epitopes including proteins that were ubiquitous, had high tissue specificity in the heart, and were expressed with high cell specificity in cells found in the cardiovascular system (Figure 5A, Table S13). We then performed a second, more targeted analysis of similarities between these sequences identified by our BLAST analysis with those found in the vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardiomyocytes, using a previously validated computational algorithm.34 We first compiled all the publicly available microarray sequences of proteins expressed in the vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and myocardial cells to create a normalized expression array using the gene expression commons repository (https://gexc.riken.jp/). This analysis confirmed sequence similarities between genes found in the smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and cardiomyocytes with our viral epitope matches (Figure 5B–C). Taken together, these findings suggest the possibility that molecular mimicry plays a mechanistic role in the development and progression of atherosclerosis and its adverse sequelae.

Figure 5. Viral epitopes share similar amino acid and nucleotide sequences with self-proteins.

(A) Schematic of the application of BLAST and gene expression commons to identify self-proteins with similar amino acid sequences to viral epitopes. Data from 20 donors was included in the analysis. (B) Heatmap showing the expression of self-proteins with similar sequences to viral epitopes across different cell types. Expression is shown as normalized activity as processed by Gene Expression Commons. (C) Expression of selected ubiquitous proteins that share similar sequences with viral epitopes stratified by different cell subtypes. Expression is shown as normalized activity as processed by Gene Expression Commons. A: atria; Ao: aorta; C: coronary; CMs: cardiomyocytes; ECs: endothelial cells; SMCs: smooth muscle cells; V1: ventricle normal; V2: ventricle with CAD; O: other; U: umbilical.

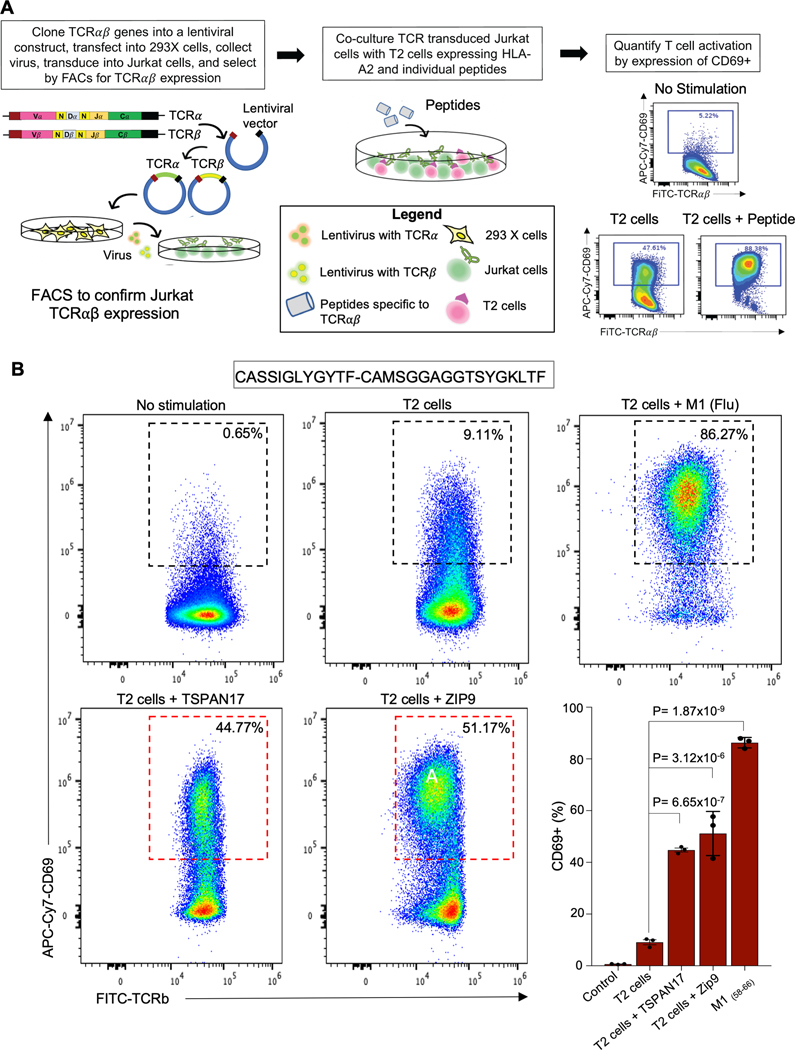

Jurkat T cells displaying TCRs identical to plaque T cells are activated by viral and self-epitopes identified by computational analysis

To confirm the viral specificities of plaque TCRs as well as potential cross-reactivity with self-epitopes (e.g., TSPAN17 and Zip9), we expressed a subset of the identified αβ pairs as transfectants in Jurkat α-β- cells, a T cell line that lacks alpha and beta heterodimer (Figure 6A). We chose the two self-epitopes with the highest homology to the M1 peptide defined by computational analysis and with previously defined contribution to atherosclerosis development: TSPAN 17 and ZIP9. These are ubiquitous proteins that are found in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Endothelial TSPAN 17, for example, is a transmembrane protein that regulates VE-cadherin expression and promotes T cell transmigration.35 Zip9, on the other hand, regulates zinc homeostasis and is also an androgen receptor on endothelial cells. A recent study has found that ZIP9 may mediate androgen induced endothelial cell proliferation, an early event in the development of atherosclerosis.36

Figure 6. Jurkat stimulation assay confirm plaque T cell cross reactivity between viral and self-epitopes.

(A) Schematic of Jurkat stimulation assay. All experiments were performed in triplicate and three triplicates were included for each sample. (B) Representative FACS dot plots showing the CD69 expression on a Jurkat transfectant with and without stimulation (left) with Bar graph display (right). One way ANOVA P value = 1.09×10−9. Post-hoc P values adjusted for 4 comparisons by the Bonferonni’s multiple comparison test are also shown to compare the differences in CD69 activation after exposure of Jurkat cells expressing a Flu-specific TCR to T2 cells with and without peptide. Jurkat cells vs. T2 cells alone, adjusted P value= 1.14×10−1; T2 cells alone vs. T2 cells + TSPAN17, adjusted P value = 6.65×10−7; T2 cells alone vs. T2 cells + Zip9, adjusted P value = 3.13×10−6; T2 cells + M158–66 (Flu), adjusted P value=1.87×10−9.

Only those TCRs exposed to antigen presenting cells displaying the appropriate MHC complex (e.g., T2 cells) and the matching epitope from the virus or self-epitopes that carry overlapping peptides will activate T cells, as demonstrated by increased expression on flow cytometry of CD69, a protein that is rapidly induced on surface of T cells after their activation. We demonstrate an increase in CD69 expression in Jurkats expressing a Flu-specific TCR after exposure to the M1 Flu peptide as well as T cross reactivity between flu and these self-proteins (44.77±0.75% TSPAN17, 51.17±4.93% for ZIP9, and 86.27±1.17% for M1 vs. 9.11±1.0% T2 cells alone and 0.65±0.08% in absence of stimulation; One way ANOVA P=1.09×10^−9) (Figure 6A–B, Figure S8A–C). Importantly, there was no significant activation of the M1-Flu specific TCR after exposure to BMLF1, an EBV peptide. In contrast, two plaque TCRs with predicted EBV specificity showed significant CD69 expression when exposed to BMLF1 (Figure S8B–C). We further validated the Flu-specific TCRs by tetramer staining, demonstrating that MHC tetramers expressing a cognate peptide could bind their matching TCR (Figure S8D).

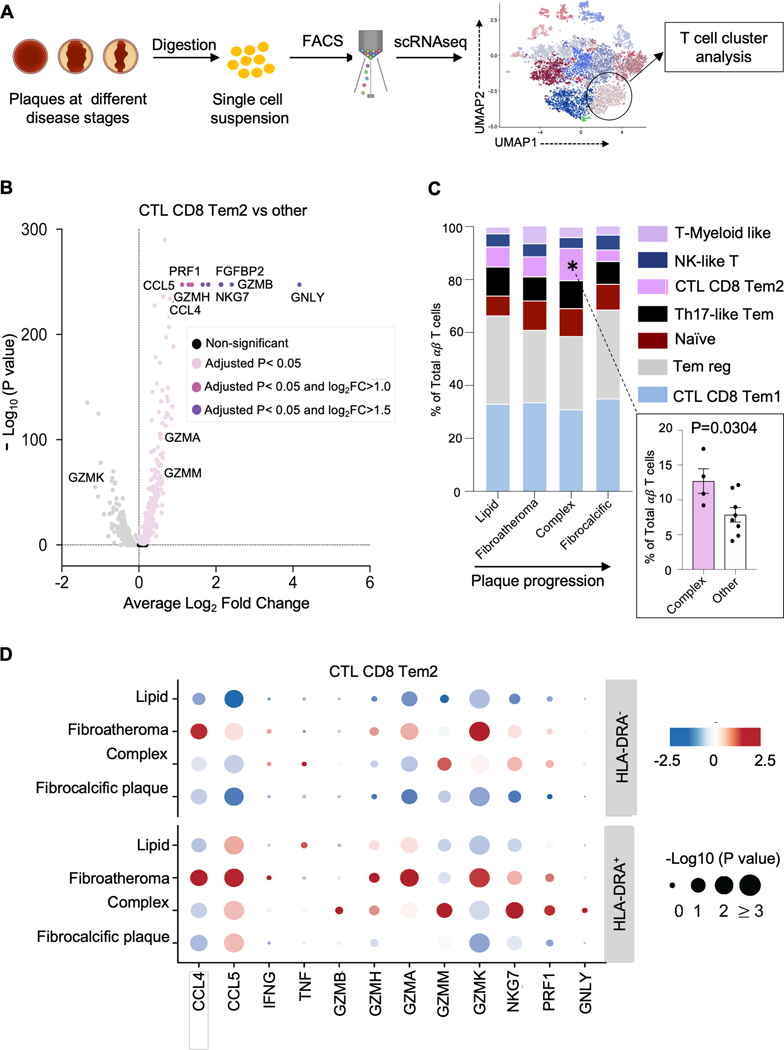

A pro-inflammatory, cytolytic T cell signature predominates in the ruptured phenotype.

In addition to clonal expansion, T cell activation leads to the release of chemokines and cytokines that interact with tissue microenvironment. To evaluate the function of these activated plaque T cells, we interrogated their transcriptome (Figure 7A). Of the seven T cell clusters that were described above, two with the highest proportion of activated cells displayed a pro-inflammatory and cytolytic signature (Figure 7A–B, Figure S9A–B), a finding that was also observed in the clonal T cells in the TCR repertoire analysis using targeted RNAseq (Figure S9C). These two cytolytic clusters, annotated as CD8 Tem1 and CD8 Tem2, both express high levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, and IFNG) and cytolytic markers (GZMA, GZMH, GZMM, NKG7). CD8 CTL Tem1, however, has higher expression of GZMK, a cytolytic marker recently associated with inflammaging. CD8 CTL Tem2, on the other hand, has a higher expression of perforin and granulysin, two pore-forming proteins that mediate cell killing by enabling granzyme entry (Figure 1E, Figure 7A–B, Figure S9A–B). Notably, CD8 CTL Tem2 appears to track with plaque progression, increasing as plaques mature from lipid-rich to more complex lesions then declining as plaques became more stable and calcified post-rupture (Figure 7C). Specifically, this cluster displayed a ~two-fold enrichment in complex plaques compared to other plaque phenotypes (12.69±1.77% vs. 7.21±0.81%, Mann-Whitney test P=1.18×10−2). This pro-inflammatory and cytolytic signature is also more apparent in the activated compared to nonactivated cells in this cluster (Figure 7D, Figure S9C). Taken together, our analysis suggests that a subset of plaque T cells express a proinflammatory, cytolytic signature that is most prominent in the activated or clonal state in the complex stage, suggesting a potential mechanism by which T cells contribute to the growing necrotic core and the weakening of the fibrous cap that can lead to plaque rupture.

Figure 7. A pro-inflammatory, cytolytic T cell signature characterizes the complex disease stage.

(A) Schematic of the evaluation of plaque T cell transcriptome with scRNAseq. Experiments were performed from samples collected from 12 donors. (B) Pro-inflammatory and cytolytic genes are upregulated in plaque residing T cells in CD8 Tem2 relative to other clusters, identified using the FindMarkers function with the default non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Selected genes with log2 fold-change (log2FC) > 0.5 (light pink), 1.0 (dark pink) and 1.5 (purple) are annotated. (C) Average frequencies of plaque T cell clusters showing significant alteration in the CD8 Tem2 cluster with plaque progression. One way ANOVA P = 4.43×10−2 for comparison of CD8 Tem2 cluster across the 4 individual phenotypes. Post-hoc unpaired Student’s t test P value = 3.04 ×10−2 adjusted for 4 comparisons by the Tukey method demonstrates significant differences in the frequency of CD8 Tem2 in complex vs, other phenotypes. (D) Dot plot for differentially expressed genes (columns) across 4 pathological disease stages (rows) in the cells in the CD8 Tem2 cluster that do and do not express the activation marker HLA-DRA (rows). Color represents the gene expression (normalized, Z scored) in each disease stage, and size indicates the proportion of cells expressing the selected genes.

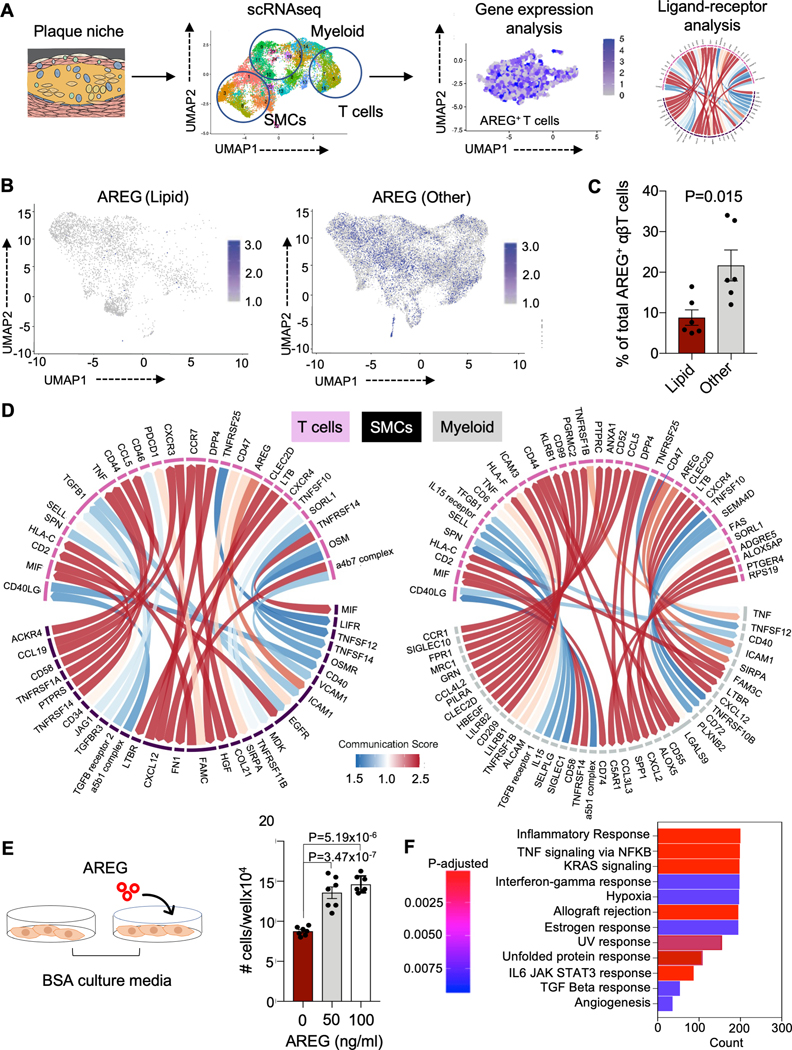

The transition between lipid and more advanced plaques is characterized by an increasing proportion of T cells expressing the pro-fibrotic protein AREG

The third T cell subset containing a high proportion of activated T cells is a cluster annotated T-myeloid like, which has been described previously in patients with cancer 37 and atherosclerosis.38 This cluster is distinguished by its high expression of AREG, a cytokine belonging to the family of epidermal growth factors that participates in tissue repair and inflammation regulation (Figure 1E). Although most prominent in the T-myeloid cluster, especially in T cells co-expressing HLA-DRA, AREG is seen throughout the plaque transcriptome and increases as plaques mature beyond the lipid rich state (Figure 8A–C; Figure S9D). Based on previous studies and our own experiments (data not shown),39 AREG is only secreted after T cell activation. In our dataset, we found 11.8±4.1% and 21.6±8.3% of plaque CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing AREG were clonal in early disease stages (Table S14), supporting a possible role for clonal T cells secreting AREG in plaque progression. Because AREG-expressing T cells have been shown to restore tissue integrity via interaction with other cells in the tissue, we analyzed the crosstalk between T cells and known pathogenic cells in the plaque microenvironment (e.g., macrophages and smooth muscle cells) in a publicly available data set of human coronary plaque at the early stages of development using a cell signaling algorithm (e.g., CellPhoneDB).40 Using this independent publicly available dataset,41 we found a significant ligand-receptor relationship between T cells expressing AREG and ICAM1 and EGFR expressed by vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) (Figure 8D, Figure S9E). Given that vascular smooth muscle cells contribute substantially to fibrous cap formation, we evaluated the effects of AREG on human coronary artery smooth muscle cell (hCASMC) proliferation in vitro (Figure 8E). We found a 1.6-fold increase in hCASMC proliferation between AREG treated and untreated cells (Figure 8E). Bulk RNAseq analysis of hCASMCs treated with AREG show enrichment of pathways associated with cellular proliferation and differentiation, angiogenesis, inflammation, and fibrosis (Figure 8F). We then identified the following genes that are not only involved in many pathways upregulated in AREG-treated samples but are also important for atherosclerosis development: 1) growth factors granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF or CSF2) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF or CSF3) as well as 2) the interleukins IL-6 and IL-1α. Specifically, expression of GM-CSF is present in un-diseased human coronary arteries and is significantly upregulated in smooth muscle cells with a synthetic phenotype in atherosclerotic arteries.42 Colony stimulating factors have also been shown to increase intimal proliferation in early atherosclerotic lesions43 and may play an important role in regulating macrophage lineage biology,44,45 as well as macrophage apoptosis.46 Similarly, hCASMCs can release IL-6 and IL-1α in response to biomechanical stress and in the senescent state,47,48 respectively, which in turn, can promote chronic inflammation, a key mediator of atherosclerosis progression.

Figure 8. The transition from lipid-rich plaques to more mature plaques is marked by increasing proportion of T cells expressing the pro-fibrotic protein AREG.

(A) Schematic of evaluation of AREG expression in coronary plaque using scRNAseq. Data from 12 donors was included in the analysis. (B, C) Comparison of AREG expression in lipid and more advanced plaque plotted by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction (B) and by bar graph stratified by donor (C). The P-value of 0.0130 was derived using unpaired Student’s t test. (D) Chord diagram showing significant ligand receptor relationships between T cells and smooth muscle cells (left) and between T cells and macrophages (right). Color scale represents strength of the ligand receptor relationship, based on the total number of interactions between the cell types. The total number of interactions are calculated using the CellPhoneDB algorithm, which measures the mean expression level of the ligand and the receptor in each cell cluster using the log transformed normalized counts. (E) Schematic of in vitro experiment evaluating the effects of AREG on the proliferation of coronary smooth muscle cells (left). Bar chart showing change in cell number before and after treatment of human coronary arterial smooth muscle cells in vitro with and without AREG (right). All experiments were performed in triplicate and 7 replicates were included for each sample. One way ANOVA P value = 2.23×10-7. Post-hoc P values adjusted for 3 comparisons by the Tukey method comparing AREG treatment to control (media only) are shown. (F) Bar plot of pathway enrichment analysis by GSEA of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from bulk RNAseq of coronary arterial smooth muscle cells treated in (E). Count represents the number of DEGs enriched in the GO term and adjusted P value indicates the corrected P value by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

Interestingly, in macrophages, we also found a significant ligand-receptor relationship between AREG expressed on T cells and its receptor, ICAM-1, expressed on macrophages. AREG has been shown to induce expression of ICAM-1 on macrophages, which may mediate efferocytosis and inflammation resolution (Figure 8D, Figure S9E).49 Taken together, these findings suggest that T cells interact with smooth muscle cells and macrophages in the plaque microenvironment partially through secretion of AREG.

Blood and T cell repertoire and transcriptome have shared and distinct features

Because the blood compartment is near the plaque microenvironment, we performed similar analyses in patients who had samples at both sites. These results are discussed in detail in the Online Supplement, where we highlight differences in the TCR repertoire (Figure S10–11), T cell specificities (Figure S12–14), and transcriptome (Figure S15) between blood and plaque.

DISCUSSION

Our current understanding of how the T cell repertoire and its transcriptome affects coronary artery plaque progression has been limited by using bulk samples and the lack of human coronary samples from living donors. Using a rigorous approach to characterize the T cell landscape at the single cell level across multiple plaque phenotypes and locations within the coronary tree from 35 living donors, our work provides detailed information on T cell subpopulations in plaques and helps ground our thinking on how they may interact within the plaque microenvironment in different stages of plaque maturity.

We, like others, find a population of activated T cells, suggesting interaction with antigens within the plaque environment. Previous studies,1,2 however, have relied on CD69 expression to identify activation, which may be problematic given recent findings that this may also reflect binding to oxidized LDL.50 In contrast, we map the T cell repertoire at the single cell level to quantify the degree of clonal expansion,12 which is arguably a more specific measure of T cell activation. Not only do we find CD4 and CD8 T clones, confirming that plaque T cells are in an activated state, but we also observe significant expansion in the CD8 repertoire that tracks with disease progression. Moreover, by including both alpha and beta identity to define clonality at the single cell level, which has not been previously documented, we provide more robust evidence that specific T cells are uniquely expanded in coronary plaque, suggesting antigen(s) may trigger activation and promote atherosclerosis. Given the size of our donor cohort, we were also able to use GLIPH2 to cluster individual TCR sequences to determine whether our donors share conserved CDR3β motifs, the TCR region that often contacts with antigenic epitopes. Our analysis revealed shared CDR3β motifs across multiple donors, suggesting that specific common antigens may be driving clonal expansion in atherosclerosis.

As an initial step to identify potential antigens that may activate T cells within the plaque, we compared our TCR repertoire, including an analysis of exact TCR sequences and GLIPH2 motifs, to published TCR databases with known specificities. Interestingly, we find plaques from multiple donors contain T cells that react to viruses, a finding that was also confirmed by in vitro stimulation assays. Importantly, a higher proportion of clonal than non-clonal T cells displays viral specificity. Notably, enrichment of Flu-specific TCRs was highest in the fibroatheroma stage, suggesting that T cells activated by engagement of Flu peptides within plaque may trigger a pro-inflammatory and cytolytic cascade that increases the size of the necrotic core and mechanical stress within the plaque, leading to the formation of complex lesions characterized by rupture, erosion, and/or thrombosis.

Similarly, previous studies using blood-based assays have demonstrated an association between Flu viral load and heart attack risk,24 while other studies have applied in vitro cultures to show activation of carotid plaque-derived T cells from by Flu peptides.25 Although we also find matches to conserved coronavirus epitopes, this observation is less robust given our matches were not restricted by MHC identity due to data unavailability and the fact that these patients were recruited after the pandemic. Nevertheless, this finding raises the possibility that activated T cells within the coronary plaque may contribute to cardiovascular complications associated with SARS-CoV-2 and its vaccine. Collectively, by directly interrogating the T cell repertoire in coronary plaque extracted from living donors, our study strengthens existing data that suggests a potential causal relationship between viral infection and plaque rupture.

Although these findings may address the potential role of viruses in triggering cardiovascular complications in the presence of active viral infection, they do not explain why patients who may have once been infected but are not actively infected suffer from myocardial infarction or myocarditis. A possible explanation is that plaque T cells with viral specificities may be reacting to self-antigens that have similar homologies to viral epitopes, a process known as molecular mimicry, and may cause arthritis,51 diabetes,52 multiple sclerosis,3,53 and narcolepsy.54 HLA-A2 restricted Flu-M1-specific CD8 T cells have demonstrated cross reactivity to other viruses including EBV-BMLF127 and SARS-CoV-2-surface glycoprotein49 as well as self-proteins. Interestingly, we find that our matched viral epitopes share similar sequences at both the protein and nucleotide level with ubiquitous proteins, some of which enrich in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes. This finding contributes to the growing evidence that atherosclerosis may be partially mediated by autoimmunity in select patients.55,56,57 Although this remains controversial, it is well documented that patients with autoimmune disease,58,59 especially those with autoantibodies,60 have an increased risk of developing atherosclerosis and its complications. Human plaques also contain antibodies against self-antigens.61 Although the exact targets for autoimmunity have yet to be described in humans, a recent study has shown that circulating autoantibodies in a murine model of autoimmune atherosclerosis target intracellular vascular proteins that become exposed after vascular damage.61 Our observations together with these studies suggest that atherosclerosis and its adverse sequelae may be partially mediated by an attack of the adaptive immune system on self-antigens that are mistaken for viral epitopes in a subset of patients who possess cross reactive T cells.

Alternatively, these viral specific T cells found in atherosclerotic plaque may be activated by cytokines and not by viral specific engagement, a process commonly referred to as bystander activation that is commonly triggered by interferons such as Type I IFN (e.g., IFNG), IL-15, and IL-18.62 We, like others, find T cell subsets expressing IFNG and its associated downstream cytokine TNF alpha, both of which have been shown to be important mediators atherosclerotic plaque development, but do not highlight them here, given their role has been well described previously. Interestingly, these cytokines are elevated in patients with severe Flu and COVID infections,63 who have also been shown to have a higher incidence of thrombotic complications.64 It is plausible that both TCR-dependent and independent activation of plaque TCRs act synergistically to mediate atherosclerotic progression and plaque rupture.

Activated CD8 T cells specific for viral epitopes including influenza, EBV, CMV, and SARS-CoV-2 have also been found in other sites not known to have tropism for these viruses, including the liver and tumors.65,66,67 In the liver, for example, viral-specific CD8 T cells, generated in response to systemic infection outside the liver, are trapped in sinusoids and can trigger T-cell mediated hepatitis in absence of viral antigen.68 The severity of hepatitis is directly related to the degree of anti-viral CD8 T cell response. Importantly, the absence of liver resident macrophages attenuates tissue damage, suggesting that crosstalk between macrophages and T cells is required for T cell activation. Similarly, we find significant ligand receptor relationships between macrophages and T cells, some of which have been shown to modulate T cell activation (e.g., osteopontin | PTGER469 and ostepontin | CD44,70 galectin | CD4419 and galectin | CD47;71 CCL3L3|DPP4 72). In addition, we find oligoclonal expansion rather than a single dominant clone, suggesting multiple TCRs or TCRs with similar binding regions are activated by specific antigen-epitope engagement and/or non-specific cytokine mediated stimulation.

We also identified many TCRs with no known specificities. Previous studies have described the presence of “clonal” T cells with specificity to apolipoprotein B, defined by positive binding to its MHC tetramer, in murine aortic plaque and in the blood of patients with CAD.73 In a study by Wolf et al, the percentage of “clonal” T cells reactive to apolipoprotein B was 0.7% vs 0.2% in human blood with CAD and without CAD, respectively,73 which is comparable to the prevalence of viral TCRs found in our plaque dataset. Future studies could measure the binding of these TCRs against peptide MHC libraries to determine their specificities and potential disease-causing antigens such as apolipoprotein B.74

In addition to their expression of receptors that bind to cytokines produced by macrophages, T cells secrete their own chemokines and cytokines that interact with the tissue microenvironment and modulate inflammation. In our analysis of the T cell plaque transcriptome, we find a cluster of CD8 T cells, especially those in the activated state, expressing a trifecta of cytolytic granules including granzymes and pore forming proteins that mediate their entry (e.g., perforin and granulysin). Well-known for their ability to mediate cell killing, these cytotoxic granules potentially contribute to the growing necrotic core and weaken the fibrous cap, promoting plaque progression and potentially plaque rupture. Notably, this T cell signature was most prominent in the complex stage characterized by rupture, thrombosis and erosion and has also been described in coronary blood of patients who are having an acute myocardial infarction.75 In contrast to this pro-inflammatory T cell subset, we also find a population of activated T cells with high expression of AREG, a cytokine that has been associated with tissue repair and the development of fibrosis.76 In mice, AREG-expressing CD4 T cells help restore tissue integrity after damage from Flu infection, allergen exposure, and muscle trauma. Mice deficient in AREG, however, do not resolve inflammation-induced injuries but they have few abnormalities under normal conditions. While the exact mechanisms by which AREG mediates tissue repair remain unclear, previous studies have suggested that AREG+ T cells promote fibrosis, in both antigen-independent and antigen-dependent manner, by increasing smooth muscle proliferation,77 or by reprograming eosinophils.78 While AREG expression has been described in innate lymphoid cells isolated from murine aortic plaques,57 neither CD4+ nor CD8+ AREG-expressing T cells have been implicated previously in atherosclerosis until now. Our data suggests that AREG-expressing T cells interact with smooth muscle cells within the plaque via binding to its receptors (e.g., ICAM1 and EGFR) and mediating coronary smooth muscle proliferation in vitro through activation of pathways that promote inflammation, proliferation, and fibrosis.

In summary, we map the T cell repertoire in coronary plaques at different stages of maturity, both within a given patient and between patients, demonstrating that T cells are clonally expanded in a disease stage specific pattern. A subset of plaque T cells express specificities to viral epitopes, some of which share similar amino acid and nucleotide sequences to ubiquitous proteins that are enriched in cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle cells and may mediate an attack on self that triggers atherosclerosis development and progression. We also demonstrate that different T cell subsets display contrasting immune signatures characteristic of their disease stage, supporting existing evidence that T cells exert both a pro- and anti-inflammatory effects in atherosclerosis depending on their cytokine and chemokine profile.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE

What is known?

Analysis of the plaque transcriptome in human carotid plaques in advanced stages of disease reveals large clusters of T cells involved in T cell receptor signalling and antigen engagement.

Autoreactive T cells, defined by binding to major histochemistry (MHC) tetramers displaying the self-protein apoliprotein B, have been found in the blood of patients with coronary artery disease.

What new information does this article contribute

In this first comprehensitive map of the human coronary atherosclerotic plaque T cell repertoire and its transcriptome, we demonstrate that CD8 T effector memory cells clonally expand with disease progression, display specificity to influenza and SARS-CoV-2, and cross-react with self-antigens.

We also show the T cell transcriptome contains discrete phenotypes that associate with disease specific stages. Specifically, T cells expressing the pro-fibrotic cytokine amphiregulin that promotes vascualr smooth muscle proliferation in vitro predominate in more mature plaques and may contribute to the development of irreversible plaques.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would also like to thank Katlyn Alexis Carey for illustrations for this study.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

We would like to thank the American Heart Association (181PA34170022, 20TPA3550008: PKN), NIA (R03 AG060182: PKN) and the NIHLBI (R01 HL 134830–01: PKN) and from Howard Hughes Medical Institute (MMD) for support of this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AREG

Amphiregulin

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- CAD

Coronary Artery Disease

- CDR3β

Complementarity Determining Region 3 of the beta chain

- CTL

CyToLytic

- CMV

CytoMegaloVirus

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- ECs

Endothelial Cells

- FACS

Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting

- Flu

inFluenza

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GLIPH2

Grouping of Lymphocyte Interactions by Paratope Hotspots

- CCL3

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 3

- CCL4

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 4

- CCL5

C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 5

- GZMA

GranZyMe A

- GZMH

GranZyMe H

- GZMM

GranZyMe M

- HLA

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- IFNG

InterFeroN Gamma

- ILN

InterLeukin

- LM

Left Main

- LAD

Left Anterior Descending

- LCx

Left Circumflex

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- NK

Natural Killer cell

- NKG7

Natural Kill cell Granule protein 7

- QC

Quality Control

- RCA

Right Coronary Artery

- scRNA-seq

single cell RNA sequencing

- SMCs

Smooth Muscle Cells

- SmGM-2

Smooth muscle cell Growth Medium-2

- TCR

T Cell Receptor

- TEM

T Effector Memory

- TSPAN17

Tetraspanin 17

- Zip9

Zinc-regulated transporter 9

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernandez DM, Rahman AH, Fernandez NF, Chudnovskiy A, Amir ED, Amadori L, Khan NS, Wong CK, Shamailova R, Hill CA, et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat Med. 2019;25:1576–1588. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0590-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Depuydt MAC, Prange KHM, Slenders L, Örd T, Elbersen D, Boltjes A, de Jager SCA, Asselbergs FW, de Borst GJ, Aavik E, et al. Microanatomy of the human atherosclerotic plaque by single-Cell transcriptomics. Circ Res. 2020;127:1437–1455. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.120.316770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geginat J, Paroni M, Pagani M, Galimberti D, De Francesco R, Scarpini E, Abrignani S. The enigmatic role of viruses in multiple sclerosis: molecular mimicry or disturbed immune surveillance? Trends in Immunology. 2017;38:498–512. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2017.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hafemeister C, Satija R. Normalization and variance stabilization of single-cell RNA-seq data using regularized negative binomial regression. Genome Biol. 2019;20:296. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1874-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novershtern N, Subramanian A, Lawton LN, Mak RH, Haining WN, McConkey ME, Habib N, Yosef N, Chang CY, Shay T, et al. Densely interconnected transcriptional circuits control cell states in human hematopoiesis. Cell. 2011;144:296–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, et al. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:163–172. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0276-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo Y, Hitz BC, Gabdank I, Hilton JA, Kagda MS, Lam B, Myers Z, Sud P, Jou J, Lin K, et al. New developments on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic acids research. 2020;48:D882–D889. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmiedel BJ, Singh D, Madrigal A, Valdovino-Gonzalez AG, White BM, Zapardiel-Gonzalo J, Ha B, Altay G, Greenbaum JA, McVicker G, et al. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on human immune cell gene expression. Cell. 2018;175:1701–1715.e1716. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, Lindskog C, Oksvold P, Mardinoglu A, Sivertsson Å, Kampf C, Sjöstedt E, Asplund A, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347:1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monaco G, Lee B, Xu W, Mustafah S, Hwang YY, Carré C, Burdin N, Visan L, Ceccarelli M, Poidinger M, et al. RNA-Seq Signatures Normalized by mRNA abundance allow absolute deconvolution of human immune cell types. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1627–1640.e1627. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han A, Glanville J, Hansmann L, Davis MM. Linking T-cell receptor sequence to functional phenotype at the single-cell level. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:684–692. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma KY, He C, Wendel BS, Williams CM, Xiao J, Yang H, Jiang N. Immune repertoire sequencing using molecular identifiers enables accurate clonality discovery and clone size quantification. Front Immunol. 2018;9:33. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendel BS, He C, Qu M, Wu D, Hernandez SM, Ma KY, Liu EW, Xiao J, Crompton PD, Pierce SK, et al. Accurate immune repertoire sequencing reveals malaria infection driven antibody lineage diversification in young children. Nat Commun. 2017;8:531. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00645-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glanville J, Huang H, Nau A, Hatton O, Wagar LE, Rubelt F, Ji X, Han A, Krams SM, Pettus C, et al. Identifying specificity groups in the T cell receptor repertoire. Nature. 2017;547:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature22976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H, Wang C, Rubelt F, Scriba TJ, Davis MM. Analyzing the Mycobacterium tuberculosis immune response by T-cell receptor clustering with GLIPH2 and genome-wide antigen screening. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:1194–1202. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0505-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shugay M, Bagaev DV, Zvyagin IV, Vroomans RM, Crawford JC, Dolton G, Komech EA, Sycheva AL, Koneva AE, Egorov ES, et al. VDJdb: a curated database of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D419–d427. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tickotsky N, Sagiv T, Prilusky J, Shifrut E, Friedman N. McPAS-TCR: a manually curated catalogue of pathology-associated T cell receptor sequences. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2924–2929. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Sergin I, Evans TD, Jeong SJ, Rodriguez-Velez A, Kapoor D, Chen S, Song E, Holloway KB, Crowley JR, et al. High-protein diets increase cardiovascular risk by activating macrophage mTOR to suppress mitophagy. Nat Metab. 2020;2:110–125. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0162-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gee MH, Han A, Lofgren SM, Beausang JF, Mendoza JL, Birnbaum ME, Bethune MT, Fischer S, Yang X, Gomez-Eerland R, et al. Antigen identification for orphan T cell receptors expressed on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Cell. 2018;172:549–563.e516. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pizzolato G, Kaminski H, Tosolini M, Franchini DM, Pont F, Martins F, Valle C, Labourdette D, Cadot S, Quillet-Mary A, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing unveils the shared and the distinct cytotoxic hallmarks of human TCRVδ1 and TCRVδ2 γδ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:11906–11915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818488116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, Satija R. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888–1902.e1821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naghavi M, Wyde P, Litovsky S, Madjid M, Akhtar A, Naguib S, Siadaty MS, Sanati S, Casscells W. Influenza infection exerts prominent inflammatory and thrombotic effects on the atherosclerotic plaques of apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2003;107:762–768. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048190.68071.2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, Chung H, Crowcroft NS, Karnauchow T, Katz K, Ko DT, McGeer AJ, McNally D, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378:345–353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller TT, Meer JJvd, Teeling P, Sluijs Kvd, Idu MM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Levi M, Wal ACvd, Boer OJd. Selective expansion of influenza A virus–specific T cells in symptomatic human carotid artery atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke. 2008;39:174–179. doi: doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.491282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Boer OJ, Teeling P, Idu MM, Becker AE, van der Wal AC. Epstein Barr virus specific T-cells generated from unstable human atherosclerotic lesions: Implications for plaque inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clute SC, Watkin LB, Cornberg M, Naumov YN, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Welsh RM, Selin LK. Cross-reactive influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells contribute to lymphoproliferation in Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3602–3612. doi: 10.1172/jci25078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aslan N, Watkin LB, Gil A, Mishra R, Clark FG, Welsh RM, Ghersi D, Luzuriaga K, Selin LK. Severity of acute infectious mononucleosis correlates with cross-reactive influenza CD8 T-cell receptor repertoires. mBio. 2017;8. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01841-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2020;17:543–558. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, Rawlings SA, Sutherland A, Premkumar L, Jadi RS, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181:1489–1501.e1415. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun J, Loyal L, Frentsch M, Wendisch D, Georg P, Kurth F, Hippenstiel S, Dingeldey M, Kruse B, Fauchere F, et al. SARS-CoV-2-reactive T cells in healthy donors and patients with COVID-19. Nature. 2020;587:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2598-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallajosyula V, Ganjavi C, Chakraborty S, McSween AM, Pavlovitch-Bedzyk AJ, Wilhelmy J, Nau A, Manohar M, Nadeau KC, Davis MM. CD8+T cells specific for conserved coronavirus epitopes correlate with milder disease in COVID-19 patients. Science Immunology. 2021;6:eabg5669. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg5669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales-Medina VF. Acute infection and myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380:171–176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1808137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seita J, Sahoo D, Rossi DJ, Bhattacharya D, Serwold T, Inlay MA, Ehrlich LI, Fathman JW, Dill DL, Weissman IL. Gene Expression Commons: an open platform for absolute gene expression profiling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reyat JS, Chimen M, Noy PJ, Szyroka J, Rainger GE, Tomlinson MG. ADAM10-interacting tetraspanins Tspan5 and Tspan17 regulate VE-cadherin expression and promote T lymphocyte transmigration. J Immunol. 2017;199:666–676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Converse A, Thomas P. Androgens promote vascular endothelial cell proliferation through activation of a ZIP9-dependent inhibitory G protein/PI3K-Akt/Erk/cyclin D1 pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2021;538:111461. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2021.111461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs T, Hahn M, Riabov V, Yin S, Kzhyshkowska J, Busch S, Püllmann K, Beham AW, Neumaier M, Kaminski WE. A combinatorial αβ T cell receptor expressed by macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Immunobiology. 2017;222:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2015.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuchs T, Puellmann K, Emmert A, Fleig J, Oniga S, Laird R, Heida NM, Schäfer K, Neumaier M, Beham AW, et al. The macrophage-TCRαβ is a cholesterol-responsive combinatorial immune receptor and implicated in atherosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;456:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson CC, Yndestad A, Enserink JM, Ree AH, Aukrust P, Taskén K. The epidermal growth factor-like growth factor amphiregulin is strongly induced by the adenosine 3’,5’-monophosphate pathway in various cell types. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5177–5184. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Efremova M, Vento-Tormo M, Teichmann SA, Vento-Tormo R. CellPhoneDB: inferring cell-cell communication from combined expression of multi-subunit ligand-receptor complexes. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:1484–1506. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0292-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirka RC, Wagh D, Paik DT, Pjanic M, Nguyen T, Miller CL, Kundu R, Nagao M, Coller J, Koyano TK, et al. Atheroprotective roles of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and the TCF21 disease gene as revealed by single-cell analysis. Nat Med. 2019;25:1280–1289. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0512-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plenz G, Koenig C, Severs NJ, Robenek H. Smooth muscle cells express granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the undiseased and atherosclerotic human coronary artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2489–2499. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu SN, Chen M, Jongstra-Bilen J, Cybulsky MI. GM-CSF regulates intimal cell proliferation in nascent atherosclerotic lesions. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2141–2149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lacey DC, Achuthan A, Fleetwood AJ, Dinh H, Roiniotis J, Scholz GM, Chang MW, Beckman SK, Cook AD, Hamilton JA. Defining GM-CSF- and macrophage-CSF-dependent macrophage responses by in vitro models. J Immunol. 2012;188:5752–5765. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lappalainen J, Yeung N, Nguyen SD, Jauhiainen M, Kovanen PT, Lee-Rueckert M. Cholesterol loading suppresses the atheroinflammatory gene polarization of human macrophages induced by colony stimulating factors. Sci Rep. 2021;11:4923. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84249-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subramanian M, Thorp E, Tabas I. Identification of a non-growth factor role for GM-CSF in advanced atherosclerosis: promotion of macrophage apoptosis and plaque necrosis through IL-23 signaling. Circ Res. 2015;116:e13–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villar-Fincheira P, Sanhueza-Olivares F, Norambuena-Soto I, Cancino-Arenas N, Hernandez-Vargas F, Troncoso R, Gabrielli L, Chiong M. Role of interleukin-6 in vascular health and disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:641734. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.641734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gardner SE, Humphry M, Bennett MR, Clarke MC. Senescent vascular smooth muscle cells drive inflammation through an interleukin-1α-dependent senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:1963–1974. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiesolek HL, Bui TM, Lee JJ, Dalal P, Finkielsztein A, Batra A, Thorp EB, Sumagin R. Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 functions as an efferocytosis receptor in inflammatory macrophages. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:874–885. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsilingiri K, Fuente Hdl, Relaño M, Sánchez-Díaz R, Rodríguez C, Crespo J, Sánchez-Cabo F, Dopazo A, Alonso-Lebrero JL, Vara A, et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor in lymphocytes prevents atherosclerosis and predicts subclinical disease. Circulation. 2019;139:243–255. doi: doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.034326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Venigalla SSK, Premakumar S, Janakiraman V. A possible role for autoimmunity through molecular mimicry in alphavirus mediated arthritis. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:938. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55730-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rojas M, Restrepo-Jiménez P, Monsalve DM, Pacheco Y, Acosta-Ampudia Y, Ramírez-Santana C, Leung PSC, Ansari AA, Gershwin ME, Anaya J-M. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2018;95:100–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tengvall K, Huang J, Hellström C, Kammer P, Biström M, Ayoglu B, Lima Bomfim I, Stridh P, Butt J, Brenner N, et al. Molecular mimicry between Anoctamin 2 and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 associates with multiple sclerosis risk. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116:16955–16960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902623116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luo G, Ambati A, Lin L, Bonvalet M, Partinen M, Ji X, Maecker HT, Mignot EJ- M. Autoimmunity to hypocretin and molecular mimicry to flu in type 1 narcolepsy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018;115:E12323-E12332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818150116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ryu H, Lim H, Choi G, Park Y-J, Cho M, Na H, Ahn CW, Kim YC, Kim W-U, Lee S-H, et al. Atherogenic dyslipidemia promotes autoimmune follicular helper T cell responses via IL-27. Nature Immunology. 2018;19:583–593. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0102-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li W, Elshikha AS, Cornaby C, Teng X, Abboud G, Brown J, Zou X, Zeumer-Spataro L, Robusto B, Choi S-C, et al. T cells expressing the lupus susceptibility allele Pbx1d enhance autoimmunity and atherosclerosis in dyslipidemic mice. JCI Insight. 2020;5. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.138274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zernecke A, Winkels H, Cochain C, Williams JW, Wolf D, Soehnlein O, Robbins CS, Monaco C, Park I, McNamara CA, et al. Meta-analysis of leukocyte diversity in atherosclerotic mouse aortas. Circ Res. 2020;127:402–426. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teixeira V, Tam L-S. Novel Insights in systemic lupus erythematosus and atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Medicine. 2018;4. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skeoch S, Bruce IN. Atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: is it all about inflammation? Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2015;11:390–400. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolf D, Ley K. Immunity and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Circulation Research. 2019;124:315–327. doi: doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merched AJ, Daret D, Li L, Franzl N, Sauvage-Merched M. Specific autoantigens in experimental autoimmunity-associated atherosclerosis. The FASEB Journal. 2016;30:2123–2134. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim T-S, Shin E-C. The activation of bystander CD8+ T cells and their roles in viral infection. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2019;51:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0316-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee JS, Shin E-C. The type I interferon response in COVID-19: implications for treatment. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2020;20:585–586. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-00429-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Veizades S, Tso A, Nguyen PK. Infection, inflammation and thrombosis: a review of potential mechanisms mediating arterial thrombosis associated with influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Biol Chem. 2022;403:231–241. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2021-0348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim J, Chang DY, Lee HW, Lee H, Kim JH, Sung PS, Kim KH, Hong SH, Kang W, Lee J, et al. Innate-like cytotoxic function of bystander-activated CD8(+) T cells is associated with liver injury in acute Hepatitis A. Immunity. 2018;48:161–173.e165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simoni Y, Becht E, Fehlings M, Loh CY, Koo S-L, Teng KWW, Yeong JPS, Nahar R, Zhang T, Kared H, et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature. 2018;557:575–579. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams DH, Hubscher SG. Systemic viral infections and collateral damage in the liver. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1057–1059. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Polakos NK, Cornejo JC, Murray DA, Wright KO, Treanor JJ, Crispe IN, Topham DJ, Pierce RH. Kupffer cell-dependent hepatitis occurs during influenza infection. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1169–1178; quiz 1404–1165. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ma X, Aoki T, Tsuruyama T, Narumiya S. Definition of prostaglandin E2-EP2 signals in the colon tumor microenvironment that amplify inflammation and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2822–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-15-0125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]