Summary

Adults with lower incomes are disproportionately affected by poverty, food insecurity, obesity, and diet‐related non‐communicable diseases (NCDs). In 2020–2021 amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) expanded the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Online Purchasing Pilot program to enable eligible participants to purchase groceries online in 47 states. This expansion underscores the need for SNAP adults to have digital literacy skills to make healthy dietary choices online. Currently, a digital literacy model does not exist to help guide USDA nutrition assistance policies and programs, such as SNAP. We conducted a systematic scoping review of the academic and gray literature to identify food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and digital literacy models. The search yielded 40 literacy models and frameworks that we analyzed to develop a Multi‐dimensional Digital Food and Nutrition Literacy (MDFNL) model with five literacy levels (i.e., functional, interactive, communicative, critical, and translational) and a cross‐cutting digital literacy component. Utilization of the MDFNL model within nutrition assistance policies and programs may improve cognitive, behavioral, food security, and health outcomes and support equity, well‐being, digital inclusion, and healthy communities to reduce obesity and NCD risks.

Keywords: digital literacy, food and nutrition literacy, food environment, online food retail

1. INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic altered where and how people access, purchase, and consume foods and meals. Social distancing requirements, fear of transmission while shopping or eating, enforced restrictions, and state public curfews to reduce COVID‐19 transmission were key contributors to Americans’ altered eating patterns. 1 , 2 These restrictions and safety precautions also contributed to the lockdown and/or closure of many restaurants, meat plants, and other businesses that further altered where and how Americans access food. 3 Between 2020 and 2021, United States (U.S.) consumers adopted new shopping and eating behaviors, both in‐store and online, in response to a food ecosystem transformed by technology‐enabled platforms and new interactive relationships between food system actors and customers. 4 , 5 This growth in technology, coupled with the health and safety concerns resulting from the COVID‐19 pandemic, led to a sharp rise in the use of online food purchasing platforms, food delivery and curbside pickup applications (apps), scan‐and‐go services using quick response (QR) codes, self‐checkouts, and payment apps. 5 In 2020, American consumers spent more than U.S. $15 billion dollars on online food and beverage purchases, and this trend is expected to grow in future years. 6 The International Food and Information Council’s 2021 Food and Health Survey found that 42% of Americans shop online for groceries at least once a month and that young consumers, African Americans, and parents with children under 18 years old are the most frequent online shoppers. 2

The COVID‐19 pandemic led to changes to the U.S. government’s safety‐net programs, including the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)‐administered Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides more than 40 million income‐eligible individuals and households with monthly monetary supplemental benefits to purchase foods and beverages. Families with a household income of ≤130% of the U.S. poverty income level are eligible to receive SNAP benefits. 7 As a result of COVID‐19, the USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service allowed waivers to U.S. states to expand the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot program from five to 47 states and the District of Columbia during 2020–2021. 8 This expansion allowed participants to use their benefits for online grocery purchases with USDA‐approved retailers. 8 The online food retail growth was coupled with a nearly 50% increase in federal SNAP spending in 2020 provided by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act that expanded the maximum monthly benefit for households. 9 SNAP Education (SNAP‐Ed), a USDA program that provides grants to states to implement nutrition education to SNAP participants, also shifted its face‐to‐face programming to e‐learning platforms. 10 This growing use of digital technology and remote communications has exposed a digital divide; many Americans with lower incomes lack access to digital technology, affordable broadband connectivity, and/or digital literacy skills to use these technologies effectively in their daily lives and to meet basic needs. 11

Although SNAP has been shown to help improve food security status of participants, SNAP participants have lower dietary quality, as measured by the Healthy Eating Index, than both SNAP‐eligible and non‐eligible U.S. adults. 12 SNAP participants are also at increased risk of and are disproportionately affected by obesity and by poverty, low diet quality, food insecurity, diet‐related non‐communicable diseases (NCDs), including type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and cancers, and related deaths. 13 , 14 The risk of severe illness from COVID‐19 is further exacerbated by these health conditions. 15 The shift to online food purchasing offers an opportunity to nudge SNAP participants towards healthy food purchases, educate consumers on nutrition and health, and provide individuals in remote and underserved areas with access to fruits, vegetables, and other healthy products. 16 These actions could help reduce SNAP participants’ risks of obesity and diet‐related NCDs. However, the digital divide and the predatory marketing practices of some online grocery retailers are key barriers that could instead exacerbate the consumption of unhealthy food and beverage products. 17 , 18

1.1. Study purpose

The purpose of this study is to build on interdisciplinary literacy concepts and constructs to develop a digital food and nutrition literacy model to support SNAP participants and SNAP‐eligible adults (herein after referred to collectively as SNAP adults) to make healthy choices in the post‐COVID online food retail ecosystem. The study has two objectives: (1) to review and outline the interdisciplinary evidence for conceptual models and frameworks relevant to food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and digital literacy and (2) to develop a multidimensional literacy model that describes the capacities and skills needed for SNAP adults to make healthy online food retail decisions. This study addresses gaps in the literature related to the capacities and needs of ethnically, racially, and culturally diverse SNAP adults to purchase healthy foods and beverages that improve diet quality and reduce obesity risk. Many conceptual models and frameworks have been published that describe components of various types of literacy, but their relevance to SNAP adults has not been reported in the published literature. The USDA does not currently use a literacy model to guide U.S. nutrition and food security policies or programs.

1.2. Defining literacy

The Oxford Dictionary defines literacy as “the ability to read or write” and broader definitions include basic arithmetic skills and the ability to read and understand the meaning of written and printed words. Functional literacy represents a “level of minimal competence in reading, writing, and arithmetic essential for daily life and work.” 19

The concept of health literacy has been widely used in clinical care and public health settings over the past two decades. Health literacy recognizes the link between low literacy skills and health practices (e.g., low medication adherence and poor self‐care) and outcomes (e.g., greater hospitalizations and higher mortality rate) for individuals and populations. 20 , 21 Health literacy is included in Healthy People 2030, in which the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has defined personal health literacy as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health‐related decisions and actions for themselves and others.” 22

Food literacy and nutrition literacy are commonly used in the published literature, but these terms have been used in different ways. Krause et al. 23 and Vettori et al. 24 identified many definitions for both food literacy and nutrition literacy. On the basis of the work of these authors and Velardo, 25 we define food literacy as the ability to obtain and apply knowledge, motivation, confidence, and skills to understand and apply government‐recommended dietary guidance. Food literacy also involves the influence of one’s personal food choices on diet quality and quantity, the environment, and the economy to support health within a sustainable food system. 23 , 24 , 25 Nutrition literacy is a subset of food literacy that involves the ability of individuals to obtain, understand, and apply nutrition information from food labels and other sources. 23 , 24 , 25 Vettori et al. 24 note that these two types of literacy could be considered one multifaceted concept collectively referred to as “food and nutrition literacy.” Table 1 outlines definitions for food, 23 , 24 , 25 nutrition, 23 , 24 , 25 and health literacy 22 , 30 described above and other types of literacy, including financial, 29 visual, 31 digital, 28 and advertising, marketing, and media literacy, 26 , 27 that relate to the food retail environment and therefore informed this study.

TABLE 1.

Literacy terms defined

| Literacy types | Definition |

|---|---|

| Advertising, marketing, and media literacy 26 , 27 | Ability to use knowledge and skills to understand the purpose of advertisements that promote brands and products through media platforms, mobile apps, and electronic devices. |

| Digital literacy 28 | Ability to use knowledge and skills to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information from various sources using digital technologies and platforms to participate in the digital world. Also called digital learning, digital proficiency, and digital fluency. |

| Financial literacy 29 | Ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively to support financial well‐being. It encompasses knowledge of financial concepts; ability to communicate about financial concepts; capacity and skills to manage personal finances and household resources and to make financial decisions; and confidence in planning effectively for future financial needs. |

| Food literacy 23 , 24 , 25 | Ability to obtain and apply knowledge, motivation, confidence, and skills to understand and apply dietary guidance; impact of one’s personal food choices on diet quality and quantity, the environment, and the economy to support health in a sustainable food system. |

| Functional literacy 19 | Ability to read, write, and perform arithmetic at a minimal level for daily life and work. |

| Health literacy 22 , 30 | Ability to obtain, process, understand, and use basic health information to make appropriate health decisions. Health literacy is not just the result of individual capacities but also the demands and complexities of the health care system. It includes measurable components, processes, and outcomes and demonstrates linkages between informed decisions and actions. |

| Nutrition literacy 23 , 24 , 25 | Ability to obtain, understand, and apply nutrition information from food labels and other sources. |

| Visual literacy 31 | Ability to take in the visual images, cues, and stimulation in the environment to understand how form, shape, and color are used in various contexts, including through social media platforms to market products. |

2. METHODOLOGY

This study was guided by two research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What conceptual frameworks and models exist for food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and digital literacy?

RQ2: How can these existing literacy models and frameworks be adapted into a multidimensional model to support SNAP adults to use online e‐commerce platforms to make healthy food retail purchases?

The study used a systematic scoping review process to compile and analyze relevant evidence to inform RQ1 and RQ2. A scoping review was chosen given the broad literature that required examination to answer the RQs and to develop a framework with many types of literacy capacities and infrastructure support for SNAP adults. The scoping review was guided by the five steps described by Arksey and O’Malley 32 that include (1) clarifying the RQs, (2) identifying relevant evidence that met the inclusion criteria, (3) selecting the evidence, (4) compiling and analyzing the evidence, and (5) synthesizing the results using a narrative format.

The first step defined various types of literacy to guide our search strategy (Table 1). Thereafter, the lead author (K.C.S.) worked with university librarians to design the search strategy (Table 2) that utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) checklist. 33 We did not assess study quality or risk of bias given the exploratory nature of the research questions and objectives.

TABLE 2.

Search terms used for the scoping review to identify existing literacy models and frameworks for food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and/or digital literacy antecedents, domains, attributes, characteristics, and/or outcomes

| Journals and databases searched | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar (first 200 hits), Google (first 200 hits) |

([literacy] AND [health OR digital OR nutrition* OR food OR diet* OR media OR financial]) AND (nutrition* OR health OR food OR diet*) AND (model* OR framework* OR scheme* OR conceptual* OR “visual aid” OR graphic) MeSH terms searched (where applicable): literacy; health literacy; health; food; diet |

Title and abstract searches were conducted in four electronic databases (i.e., Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science). Google (first 200 hits) and Google Scholar (first 200 hits) browsers 34 were also searched in incognito mode. We used the search terms in Table 2 to identify relevant conceptual models and frameworks. Inclusion criteria were peer‐reviewed and gray literature sources published in the English language from database inception to the time of the search (January 2021) that described a visual conceptual model or framework for food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and/or digital literacy antecedents, domains, attributes, and/or outcomes. Detailed exclusion criteria are available in Table S1.

The principal investigator (K.C.S.) conducted the electronic searches and screened and identified relevant full‐text articles for consideration. Two co‐investigators (K.C.S. and V.I.K.) independently reviewed the full‐text articles and met to resolve disagreements about whether evidence sources met the inclusion criteria. One researcher (V.I.K.) conducted the data extraction for the included articles, including extracting each literacy model or framework.

2.1. Model development

All literacy models and frameworks identified through the scoping review were independently reviewed by the co‐investigators. Each researcher identified a subset of models and frameworks that included components relevant to the literacy skills and capacities of the SNAP adult population and to navigating a food retail environment. The researchers pulled from their own experience researching and working with SNAP populations and digital technology for food and nutrition. The researchers also pulled from a variety of published articles and gray literature sources. These sources included existing models and conceptual frameworks that outline consumer interactions in retail environments, 35 , 36 findings from studies on the barriers and motivators for uptake of online food purchasing by SNAP adults, 37 , 38 and literature on the digital divide and the needs of low‐income populations to fill this gap. 11 , 17

Through virtual discussions, the co‐investigators collectively agreed on the features of relevant models and frameworks to synthesize into a digital food and nutrition literacy model. Two co‐investigators (K.C.S. and V.I.K.) further analyzed the subset of models and frameworks and their corresponding articles to develop comprehensive definitions and categorizations for inputs, literacy levels, and outcomes relevant to SNAP adults to inform the multidimensional model. All authors provided feedback on multiple model drafts until consensus was reached.

3. RESULTS

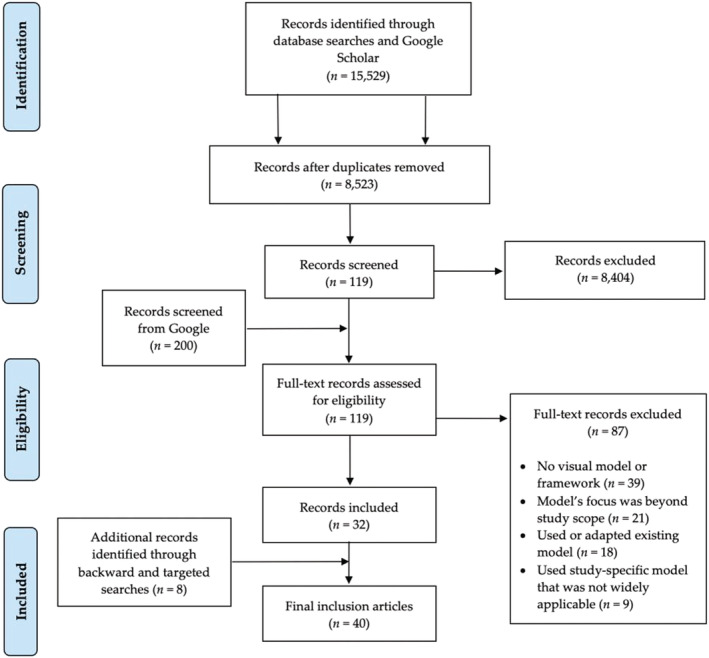

Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram for the search that collected data to inform RQ1. We identified 40 evidence sources that described and visually depicted a conceptual model or framework for health literacy 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 (n = 25); food and nutrition literacy 24 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 (n = 10); and digital, advertising, or marketing and media literacy (n = 5). 26 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 Although several of the 40 models and frameworks described concepts related to financial and resource management, we did not find an explicit model for financial literacy. Table 3 summarizes the evidence sources for the 40 models and frameworks reviewed, and the visual models and frameworks are included in Figures S1–S40.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the scoping review of literacy frameworks that influence the diet and health outcomes of individuals and populations

TABLE 3.

Conceptual frameworks and models that describe the food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and digital literacy domains and attributes that influence diet and health outcomes identified by the scoping review

| Lead author, year | Framework or model |

|---|---|

| Health literacy frameworks and models (n = 25) | |

| Al Sayah and Williams 39 | Integrated Health Literacy Model for Diabetes |

| Baker 40 | Conceptual Model of Individual Capacities, Health‐related Print and Oral Literacy, and Health Outcomes |

| Chin et al. 41 | Process‐knowledge Model of Health Literacy (based on Morrow et al. 2006 model) |

| Edwards et al. 42 | The Health Literacy Pathway Model |

| Geboers et al. 43 | Health Literacy Intervention Model |

| Gilstad 44 | Comprehensive E‐health Literacy Model |

| Goldsmith and Terui 45 | Relational Health Literacy Conceptual Model |

| Harrington and Valerio 46 | Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Model |

| Kayser et al. 47 | e‐Health Literacy Framework |

| Lloyd et al. 48 | Five‐dimensional Framework for the Attributes of a Health Literate Organization |

| Norgaard et al. 49 | e‐Health Literacy Framework |

| Norman and Skinner 50 | e‐Health Literacy Lily Model (includes analytical and context‐specific models) |

| Nutbeam 51 | Health Literacy Tripartite Model |

| Nutbeam 52 | Health Literacy Risk and Asset Models |

| Paasche‐Orlow and Wolf 53 | Causal Pathways Model Linking Health Literacy to Health Outcomes |

| Paige et al. 54 | Transactional Model of E‐health Literacy |

| Pawlak 55 | Determinants of Health Literacy |

| Renwick 56 | 3D Literacy Model |

| Smith and Hudson 57 | Person–environment–occupational Performance Model to Examine Health Literacy |

| Soellner et al. 58 | Theoretical Qualitative Structural Model of Health Literacy |

| Sorensen et al. 59 | Integrated Health Literacy Model |

| Squiers et al. 60 | Health Literacy Skills Framework |

| Trezona et al. 61 | Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness Framework |

| von Wagner et al. 62 | Framework of Health Literacy and Health Action |

| Yip 63 | Health Literacy Model for Limited English‐speaking Populations |

| Food, nutrition, health, and media literacy frameworks and models (n = 10) | |

| Azevedo Perry et al. 64 | Food and Nutrition Literacy Framework |

| Block et al. 65 | Food Well‐being Model |

| Cullen et al. 66 | Food Literacy Framework for Action |

| Malan et al. 67 | Food Literacy Model for a University Setting |

| Park et al. 68 | Food Literacy Framework for Food Systems and Sustainability |

| Spiteri‐Cornish et al. 69 | Framework for Consumer Confusion Related to Healthy Eating |

| Truman et al. 70 | Food, Nutrition, Health, and Media Literacy Outcomes Framework |

| Truman and Elliott 71 | Food Literacy Proficiency Model |

| Vettori et al. 24 | Framework for Antecedents and Consequences of Food and Nutrition Literacy |

| Vidgen and Gallegos 72 | Food Literacy Model |

| Media, digital, and advertising or marketing literacy frameworks or models (n = 5) | |

| Bergsma and Ferris 73 | Integrated Health‐promoting Media Literacy Model |

| DQ Institute and Park 74 , 75 | Digital Intelligence Framework |

| Malmelin 26 | Advertising Literacy Model |

| Montgomery et al. 76 | Digital Food Marketing Framework |

| UNESCO 77 | Digital Literacy Global Framework |

3.1. Overview of seven models and frameworks that guided the model development

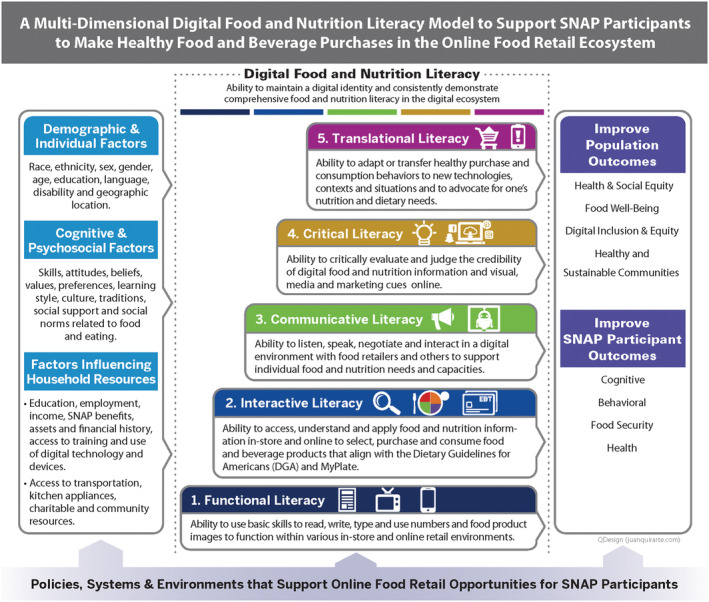

To address RQ2, seven of the 40 literacy models and frameworks reviewed were selected 46 , 51 , 54 , 55 , 60 , 63 , 71 to inform the development a unique typology to address the specific capacities and skills of SNAP adults functioning in the online food retail ecosystem. Figure 2 depicts the Multi‐dimensional Digital Food and Nutrition Literacy (MDFNL) model developed.

FIGURE 2.

Multi‐dimensional Digital Food and Nutrition Literacy (MDFNL) model to support Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) adults to make healthy purchases in the online food retail ecosystem

The earliest relevant model was a health literacy framework developed in 2000 by the Australian researcher Don Nutbeam that describes health literacy as an outcome of health education and communication programs. 51 Although Nutbeam 51 did not include a visual literacy model, the Health Literacy Tripartite Model that he described has since been visually depicted and adapted by numerous researchers and informed seven other models and frameworks included in our review 54 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 68 ; therefore, it was considered.

The five progressive levels in our MDFNL model include: functional, interactive, communicative, critical, and translational literacy. The model presents digital literacy as a cross‐cutting theme for all five literacy levels. These levels were influenced by the three literacy levels (i.e., functional, interactive, and critical) described in Nutbeam’s Health Literacy Tripartite Model 51 and by Paige et al., 54 which adapted the three domains to the e‐health context and added a fourth level called translational literacy.

Nutbeam 51 defined functional literacy as “sufficient basic skills in reading and writing to be able to function effectively in everyday situations” (p. 263). We used this as a foundation for our definition, expanding it to encompass the online food ecosystem. Nutbeam’s definition did not address numeracy skills, which was a key component of health literacy in many of the other models and frameworks examined. 44 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 60 , 63 We defined functional literacy as the “ability to use basic skills to read, write, type, and use numbers and food product images to function within various in‐store and online retail environments.”

Nutbeam 51 and Paige et al. 54 described communicative and interactive literacy as one level, defined respectively as “more advanced cognitive and literacy skills which, together with social skills, can be used to actively participate in everyday activities…” (p. 263–264) and “the ability to collaborate, adapt, and control communication about health with users on social online environments with multimedia” (p. 11). These two definitions describe interactions between patients and health care professionals either in person or online. However, the digital retail environment has many complex interactions that consumers must negotiate, including interactions with (1) food and nutrition information available on packages (i.e., nutrition facts panels, front‐of‐package labels, and product logos); (2) personally tailored advertisements, promotions, and other digital materials displayed on websites; and (3) food retailers, through online retail assistance bots and pickup and/or delivery staff, and SNAP support staff. We therefore divided the communicative and interactive literacy category into two separate levels. We defined interactive literacy as “the ability to access, understand, and apply food and nutrition information in‐store and online to select, purchase, and consume food and beverage products that align with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) and MyPlate.” We defined communicative literacy as “the ability to listen, speak, negotiate, and engage in a digital environment with food retailers and others to support individual food and nutrition needs and capacities.”

We adapted the definition of critical health literacy 54 for the online food retail ecosystem context as “the ability to critically evaluate and judge the credibility of digital food and nutrition information and visual, media, and marketing cues online.” Paige et al. 54 also describes the addition of translational health literacy to their e‐health‐focused model, which the authors define as an individual’s ability to use acquired knowledge and skills in diverse settings and contexts, building the bridge between knowledge and action to achieve health literacy outcomes. For SNAP adults to function effectively within a digital food retail ecosystem, we revised the definition of translational literacy to “the ability to adapt or transfer healthy purchase and consumption behaviors to new technologies, contexts, and situations and to advocate for one’s nutrition and dietary needs.”

Table 4 provides illustrative examples of each of the five literacy levels for the digital food retail ecosystem. These literacy levels represent a multitiered approach, with each level building on the previous one. For example, a person cannot achieve interactive literacy without having achieved functional literacy. The goal is to achieve proficiency in digital food and nutrition literacy, which we defined as “the ability to maintain a digital identity and consistently demonstrate comprehensive food and nutrition literacy in the digital ecosystem.”

TABLE 4.

Illustrative examples of literacy proficiency level functions and capacities based on the Multi‐dimensional Digital Food and Nutrition Literacy (MDFNL) model

| Literacy level | Illustrative examples |

|---|---|

| Translational literacy | The ability to transfer purchasing practices from one food retailer to another to get better prices on food products, lower delivery costs, etc.; the ability to adapt food purchasing patterns to buy food from a retailer’s online platform rather than shopping in‐store. |

| Critical literacy | The ability to recognize when online food retail platforms use algorithms to market unhealthy items (e.g., snack foods, sugary beverages); the ability to identify when retailers use geolocation and personal data to market specific items. |

| Communicative literacy | The ability to communicate effectively with retailers or retail bots to coordinate curbside pick‐up or delivery of food purchases; the ability to navigate online help centers and automated systems. |

| Interactive literacy | The ability to read a nutrition label and use that information to inform a purchasing decision; the ability to compare similar food products’ nutrition labels and determine which option better aligns with the DGA and MyPlate. |

| Functional literacy | The ability to use numeracy skills to calculate the price per ounce of a food product; the ability to read a nutrition label to understand basic information, such as the calories per serving size. |

Digital literacy is represented as a cross‐cutting factor in our MDFNL model, which involves an individual learning and acquiring digital technology skills to achieve each progressive level. For example, a basic understanding of how to use a computer, smartphone, or other electronic device is needed to achieve functional literacy; achieving critical literacy involves a greater understanding of the capacities, tactics, and outlets used by food manufacturers and retailers to market unhealthy food and beverage products to individuals within the digital ecosystem.

The demographic and individual factors and the cognitive and psychosocial factors in our model were identified primarily from two studies reviewed. Harrington and Valerio 46 described various characteristics (i.e., demographics, attributes, skills, health system experience, culture, distress, information resources, and psychosocial) that influence health literacy. Pawlak 55 described health literacy as a determinant of health and portrayed a health literacy model that included individual and population determinants (i.e., age, genetics, language, education, employment, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and environment) that may influence health literacy at an individual or collective level. We also identified several factors that influence household resources (e.g., SNAP benefits, assets, and financial history, etc.) that none of the models reviewed described but that are necessary to consider for SNAP households.

The bottom of the MDFNL model identifies policies, systems, and environments (PSE) that support online food retail opportunities for SNAP adults. The PSE are influenced by many government and private‐sector actors, including USDA and other government agencies, SNAP‐authorized retailers, local government bodies (e.g., local zoning boards and banks that provide business and housing loans), community groups, and other stakeholders. These stakeholders may influence the availability of and access to online SNAP‐authorized retailers, educational opportunities, and affordable and culturally accepted nutritious food and beverage products.

We considered many barriers and facilitating factors when developing our MDFNL model that may influence SNAP adults’ digital food and nutrition literacy skills. These factors include access to broadband services, the internet, and digital devices; the type and quality of interactions with food retailers and SNAP and other social services benefits program staff; confidence in using digital technology; multimedia exposure; and resource constraints. We captured these factors within the PSE element of our model.

The MDFNL model aims to improve individual‐level SNAP adult outcomes (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, food security, and health outcomes) and population outcomes (i.e., health and social equity, food well‐being, digital inclusion and equity, and healthy and sustainable communities). These outcomes were informed by the model published by Truman and Elliott 71 that outlined food literacy proficiency as a driver of individual nutrition‐related outcomes. These authors noted that higher food literacy can contribute to community‐ and population‐level health outcomes. 71

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined 40 health, food, nutrition, media, and digital literacy frameworks and models, of which seven were used to develop the MDFNL model for SNAP adults. A conceptual framework or model enables one to reflect systematically on specific principles to inform program, policy, or research decisions. 78 Frameworks or models may serve different purposes. Examples include analytic, causal, and explanatory; intervention and implementation; monitoring and evaluation; and institutional policy and regulatory frameworks and models. This MDFNL model can serve multiple purposes. It can be used as a policy tool to encourage USDA and other government agencies to improve the infrastructure, support systems, and programs delivered to U.S. adults with lower incomes to encourage healthy online food purchases. The MDFNL model is also a resource for decision makers to develop interventions to help Americans make healthy choices in the online food retail ecosystem.

This is the first model, based on our knowledge, that addresses the comprehensive digital food and nutrition literacy characteristics, needs, and outcomes for SNAP adults. The MDFNL model explains how multi‐dimensional literacy may impact consumer behaviors and interactions in both the online and in‐person food retail environments described by Khandpur et al. 35 and Winkler et al. 36 The growing digital retail environment represents an opportunity for USDA and other stakeholders to utilize digital platforms to educate and encourage SNAP adults to make healthy food and beverage products. However, a recent study of states that have implemented the SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot found that state governments provided little health and nutrition information around their communication about the Pilot program. 17 By improving Americans’ digital food and nutrition literacy skills, the U.S. government and other stakeholders could support Americans to make healthy decisions that align with the DGA and MyPlate. This MDFNL model is also timely given USDA’s recent launch of the artificial intelligence (AI)‐driven Alexa digital tool to help parents and caregivers of infants and toddlers aged four to 24 months to receive information about what and how to feed their child based on their age. 79 This launch further emphasizes USDA’s growing reliance on digital technologies for nutrition‐relevant policies and programs.

Although the focus of this paper was specific to SNAP adults within the U.S. population, the findings are applicable to low‐income populations in other countries. E‐commerce for food and beverage products has grown in countries worldwide due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. At the same time, many countries continue to face a digital divide that prevents certain vulnerable low‐income populations from engaging in e‐commerce. 80 The MDFNL model could be adapted and used to assess the digital capacities and skills of at‐risk populations in other countries that must function within growing online food retail ecosystems.

4.1. Health literacy considerations for USDA and food retailers

In the MDFNL model, we excluded institutional or organizational health literacy, defined in Healthy People 2030 as “the degree to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health‐related decisions and actions for themselves and others.” 22 However, we identified two publications 48 , 61 that suggested steps to create or strengthen health‐literate organizations relevant to federal agencies and health care institutions. Lloyd et al. 48 described five attributes of a health‐literate organization: (1) organizational commitment, (2) accessible education and technology infrastructure, (3) an augmented workforce, (4) embedded policies and practices, and (5) effective bi‐directional communication. Trezona et al. 61 outlined seven characteristics, practices, values, and capabilities of health literacy‐responsive organizations.

The USDA and food retailers could utilize these institutional literacy models to strengthen their internal policies and programs to foster health literacy for their employees and the programs that they support. For example, these organizations could align with the Healthy People 2030 objective of increasing the health literacy of the U.S. population and advance progress towards the 2030 goal to “eliminate health disparities, achieve health equity, and attain health literacy to improve the health and well‐being of all.” 22 This focus could include digital literacy to improve the nutrition security of SNAP adults by helping them to navigate the increasingly online nature of the health care and food systems.

4.2. Study strengths and limitations

A strength of this study was the extensive interdisciplinary literature searched to develop the MDFNL model. The search parameters for the scoping review were intentionally kept broad in order to capture potentially relevant models and frameworks from a wide array of peer‐reviewed and gray literature sources. Another strength was that the authors independently reviewed and assessed each of the 40 frameworks and models before coming to agreement on a subset to inform the development of the MDFNL model. This approach reduced the risk of one researcher influencing another’s perception of each model and framework’s relevance. Due to time constraints, only one researcher screened articles for inclusion, which could have introduced bias in the evidence synthesis process. A limitation of the study was the extensive literature that describes many models and frameworks for specific populations, disease states, or institutional contexts. An in‐depth analysis and explanation of each model was beyond the scope of this study. Future research could characterize each of these frameworks and models and identify the similarities and differences between them as it relates to each type of literacy. Additional research would facilitate our ability to understand the entire landscape of literacy‐relevant models and frameworks. Another limitation was that the study scope did not examine the digital literacy needs of children and adolescents, which have been addressed elsewhere. 81 , 82

Future research could test this model and validate metrics to measure progress through a monitoring and evaluation tool to achieve the outcomes. McNamara et al. 83 performed a qualitative analysis to understand how the three nutrition literacy domains outlined by Velardo 25 (i.e., functional, interactive, and critical) influence the dietary decisions of college students. Future research could perform a similar qualitative study for the MDFNL model to assess how each of the model’s five literacy levels and cross‐cutting digital literacy domain influence the online grocery purchasing decisions of SNAP adults or another U.S. subpopulation.

5. CONCLUSION

This study enhances our understanding of the multidimensional digital literacy capacity and skills needed to support SNAP adults to make healthy decisions when shopping on online food retail platforms. Many conceptual models and frameworks have been published that define and describe health, food, nutrition, and media literacy that were used to inform this proposed MDFNL model. However, there was limited published literature on financial and digital literacy models relevant to food and nutrition. Few models or frameworks addressed the needs of the SNAP adult population for digital food and nutrition literacy. Additional research is needed to test this MDFNL model and develop comprehensive tools to guide equitable policies and programs for racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse SNAP adults to function effectively within an e‐commerce environment and promote healthy dietary behaviors that reduce obesity and diet‐related NCD risks. This research is timely given the growth in online food purchasing during COVID‐19 and the continued rise in this behavior expected for the future. This model offers an outline for key areas that policymakers could use to strengthen the PSE surrounding the online food retail ecosystem to better support SNAP adults’ capacities to make healthy food purchases. It could also be used by USDA, including SNAP‐Ed, and other government agencies to strengthen the digital food and nutrition literacy skills of SNAP adults.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest statement.

Supporting information

Table S1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the scoping review to identify existing literacy models and frameworks for food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and/or digital literacy antecedents, domains, attributes, characteristics, and/or outcomes.

Figure S1. Integrated Health Literacy Model for Diabetes (Al Sayah and Williams 2012)

Figure S2. Conceptual Model of Individual Capacities, Health‐Related Print and Oral Literacy, and Health Outcomes (Baker 2006)

Figure S3. Process‐Knowledge Model of Health Literacy (Chin et al. 2011)

Figure S4. The Health Literacy Pathway Model (Edwards et al. 2012)

Figure S5. Health Literacy Intervention Model (Geboers et al. 2018)

Figure S6. Comprehensive e‐Health Literacy Model (Gilstad 2014)

Figure S7. Relational Health Literacy Conceptual Model (Goldsmith and Terui 2018)

Figure S8. Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Model (Harrington and Valerio 2014)

Figure S9. e‐Health Literacy Framework (Kayser et al. 2015)

Figure S10. Five‐Dimensional Framework for the Attributes of a Health Literate Organization (Lloyd et al. 2018)

Figure S11. e‐Health Literacy Framework (Norgaard et al. 2015)

Figure S12. e‐Health Literacy Lily Model (includes analytical and context‐specific models) (Norman and Skinner 2006)

Figure S13. Health Literacy Tripartite Model (Nutbeam 2000)

Figure S14. Health Literacy Risk and Asset Models (Nutbeam 2008)

Figure S15. Causal Pathways Model Linking Health Literacy to Health Outcomes (Paasche‐Orlow and Wolf 2007)

Figure S16. Transactional Model of eHealth Literacy (Paige et al. 2018)

Figure S17. Determinants of Health Literacy (Pawlak 2005)

Figure S18. 3D Literacy Model (Renwick 2017)

Figure S19. Person–Environment– Occupational Performance Model to Examine Health Literacy (Smith and Hudson 2012)

Figure S20. Theoretical Qualitative Structural Model of Health Literacy (Soellner et al. 2017)

Figure S21. Integrated Health Literacy Model (Sorensen et al. 2012)

Figure S22. Health Literacy Skills Framework (Squiers et al. 2012)

Figure S23. Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness Framework (Trezona et al. 2017)

Figure S24. Framework of Health Literacy and Health Action (von Wagner et al. 2009)

Figure S25. Health Literacy Model for Limited English‐Speaking Populations (Yip 2012)

Figure S26. Food and Nutrition Literacy Framework (Azevedo Perry et al. 2017)

Figure S27. Food Well‐Being Model (Block et al. 2011)

Figure S28. Food Literacy Framework for Action (Cullen et al. 2015)

Figure S29. Food Literacy Model for a University Setting (Malan et al. 2020)

Figure S30. Food Literacy for Food Systems and Sustainability Framework (Park et al. 2020)

Figure S31. Framework for Consumer Confusion Related to Healthy Eating (Spiteri‐Cornish et al. 2015)

Figure S32. Food, Nutrition, Health and Media Literacy Outcomes Framework

(Truman et al. 2020)

Figure S33. Food Literacy Proficiency Model (Truman and Elliott 2019)

Figure S34. Framework for Antecedents and Consequences of Food and Nutrition Literacy (Vettori et al. 2019)

Figure S35. Food Literacy Model (Vidgen & Gallegos 2014)

Figure S36. Integrated Health‐Promoting Media Literacy Model (Bergsma & Ferris 2011)

Figure S37. Digital Intelligence Literacy Framework (DQ Institute 2020 and Park 2019)

Figure S38. Advertising Literacy Model (Malmelin 2010)

Figure S39. Digital Food Marketing Framework (Montgomery et al 2011)

Figure S40. Digital Literacy Global Framework (UNESCO 2018)

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was funded by Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, through a special rapid‐response research opportunity focused on COVID‐19 and the federal nutrition programs, to inform decision‐making regarding innovative policies and/or programs during and after the COVID‐19 pandemic. The authors thank Juan Quirarte and Ian Stanley for designing the figures and graphical abstract and the Virginia Tech librarians for their assistance with refining the scoping review process used in this article.

Consavage Stanley K, Harrigan PB, Serrano EL, Kraak VI. A systematic scoping review of the literacy literature to develop a digital food and nutrition literacy model for low‐income adults to make healthy choices in the online food retail ecosystem to reduce obesity risk. Obesity Reviews. 2022;23(4):e13414. doi: 10.1111/obr.13414

Funding information Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

REFERENCES

- 1. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development . Food Supply Chains and COVID‐19: Impacts and Policy Lessons. Published June 2, 2020. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/food-supply-chains-and-covid-19-impacts-and-policy-lessons-71b57aea/

- 2. International Food Information Council . 2021 Food & Health Survey. Published May 19, 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://foodinsight.org/2021-food-health-survey/

- 3. Welsh C. COVID‐19 and the U.S. Food System. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Published May 21, 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.csis.org/analysis/covid-19-and-us-food-system

- 4. Deloitte Global . Future of Food: Developing a Roadmap for Success in the Changing Food Ecosystem. Published in 2019. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/consumer-business/articles/future-of-food.html

- 5. Granheim SI, Løvhaug AL, Terragni L, Torheim LE, Thurston M. Mapping the digital food environment: a systematic scoping review. Obes Rev. 2021;23(1):e13356. 10.1111/obr.13356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coppola D. U.S. Consumers: Online Grocery Shopping – Statistics & Facts. Statista. Published November 26, 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.statista.com/topics/1915/us-consumers-online-grocery-shopping/

- 7. U.S. Department of Agriculture . Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program. N.d

- 8. U.S. Department of Agriculture . FNS Launches the Online Purchasing Pilot. Published May 29, 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/online-purchasing-pilot

- 9. Evich HB. Food Stamp Spending Jumped Nearly 50 Percent in 2020. Politico. Published January 27, 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/01/27/food-stamp-spending-2020-463241

- 10. Schuster E. Community nutrition education during a pandemic. Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior. Published September 21, 2020. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.sneb.org/community-nutrition-education-during-a-pandemic/

- 11. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development , Office of policy development and research . Digital Inequality and Low‐Income Households. Published fall 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall16/highlight2.html

- 12. Singleton CR, Young SK, Kessee N, Springfield SE, Sen BP. Examining disparities in diet quality between SNAP participants and non‐participants using Oxaca‐Blinder decomposition analysis. Prev Med Rep. 2020;19:101134. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conrad Z, Rehm CD, Wilde P, Mozaffarian D. Cardiometabolic mortality by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and eligibility in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):466‐474. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagata JM, Seligman HK, Weiser SD. Perspective: the convergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and food insecurity in the United States. Adv Nutr. 2020;12(2):287‐290. 10.1093/advances/nmaa126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID‐19: People with Certain Medical Conditions. Updated May 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

- 16. Dunn CG, Bianchi C, Fleischhacker S, Bleich SN. Nationwide assessment of SNAP online purchasing pilot state communication efforts during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2021;53(11):931‐937. 10.1016/j.jneb.2021.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chester J, Katharina K, Montgomery KC. Does buying groceries online put SNAP participants at risk? Executive summary. Center for Digital Democracy. Published July 2020. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.democraticmedia.org/sites/default/files/field/public-files/2020/cdd_snap_exec_summary_ff_0.pdf

- 18. Consavage Stanley K, Harrigan PH, Serrano EL, Kraak VI. Applying a multi‐dimensional digital food and nutrition literacy model to inform research and policies to enable adults in the U.S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to make healthy purchases in the online food retail ecosystem. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8335. 10.3390/ijerph18168335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Literacy . Oxford reference. Published 2021. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20111114202329992 ‐:~:text=1.,also includes basic arithmetical competence.&text=Functional literacy%3A a level of,for daily life and work

- 20. Parker R. Health literacy: a challenge for American patients and their health care providers. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(4):277‐283. 10.1093/heapro/15.4.277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bermna ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97‐107. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services , Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. Updated December 2020. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://health.gov/our-work/healthy-people/healthy-people-2030/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030

- 23. Krause C, Sommerhalder K, Beer‐Borst S, Abel T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promot Int. 2018;33(3):378‐389. 10.1093/heapro/daw084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vettori V, Lorini C, Milani C, Bonaccorsi G. Towards the implementation of a conceptual framework of food and nutrition literacy: providing healthy eating for the population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(24):5041. 10.3390/ijerph16245041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Velardo S. The nuances of health literacy, nutrition literacy, and food literacy. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015;47(4):385‐389.e1. 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.04.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Malmelin N. What is advertising literacy? Exploring the dimensions of advertising literacy. J Visual Literacy. 2010;29(2):129‐142. 10.1080/23796529.2010.11674677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Potter WJ. Review of literature on media literacy. Sociol Compass. 2013;7(6):417‐435. 10.1111/soc4.12041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Costa Coitinho Delmuè D, Ionata de Oliveira Granheim S, Oenema S, Eds. Nutrition in a digital world. Glossary. UNSCN Nutrition. 2020; 45: 143–144. https://www.unscn.org/uploads/web/news/UNSCN-Nutrition-45-WEB.pdf

- 29. Remund DL. Financial literacy explicated: the case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. J Consumer Affairs. 2010;44(2):276‐295. 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01169.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pleasant A, Rudd RE & O’Leary C et al. Considerations for a new definition of health literacy. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC 2016. 10.31478/201604a [DOI]

- 31. Brumberger E. Past, present, future: mapping the research in visual literacy. J Visual Literacy. 2019;38(3):165‐180. 10.1080/1051144X.2019.1575043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Social Res Method. 2005;8(1):19‐32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trico AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467‐473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. Plos ONE. 2015;10(9):e0138237. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khandpur N, Zatz LY, Bleich SN, et al. Supermarkets in cyberspace: a conceptual framework to capture the influence of online food retail environments on consumer behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(22):8639. 10.3390/ijerph17228639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Winkler MR, Zenk SN, Baquero B, et al. A model depicting the retail food environment and customer interactions: components, outcomes, and future directions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20):7591. 10.3390/ijerph17207591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinez O, Tagliaferro B, Rodriguez N, Athens J, Abrams C, Elbel B. EBT payment for online grocery orders: a mixed‐methods study to understand its uptake among SNAP recipients and the barriers to and motivators for its use. Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(4):396‐402.e1. 10.1016/j.jneb.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cohen N, Tomaino Fraser K, Arnow C, Mulcahy M, Hille C. Online grocery shopping by NYC public housing residents using Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits: a service ecosystems perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(11):4694. 10.3390/su12114694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Al Sayah F, Williams B. An integrated model of health literacy using diabetes as an exemplar. Can J Diabetes. 2012;36(1):27‐31. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2011.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):878‐883. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chin J, Morrow DG, Stine‐Morrow EA, Conner‐Garcia T, Graumlich JF, Murray MD. The process‐knowledge model of health literacy: evidence from a componential analysis of two commonly used measures. J Health Commun. 2011;16(Suppl 3):222‐241. 10.1080/10810730.2011.604702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Edwards M, Wood F, Davies M, Edwards A. The development of health literacy in patients with a long‐term health condition: the health literacy pathway model. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:130. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Geboers B, Reijneveld SA, Koot JAR, de Winter AF. Moving towards a comprehensive approach for health literacy interventions: the development of a health literacy intervention model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1268. 10.3390/ijerph15061268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gilstad H. Toward a comprehensive model of eHealth literacy. In: Jaatun EAA, Brooks E, Berntsen KE, Gilstad H, Jaatun MG, eds. Proceedings of the 2nd European Workshop on Practical Aspects of Health Informatics (PAHI 2014). Trondheim Norway; 2014. 10.13140/2.1.4569.0247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Goldsmith JV, Terui S. Family oncology caregivers and relational health literacy. Challenges. 2018;9(2):35. 10.3390/challe9020035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Harrington KF, Valerio MA. A conceptual model of verbal exchange health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):403‐410. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kayser L, Kushniruk A, Osborne RH, Norgaard O, Turner P. Enhancing the effectiveness of consumer‐focused health information technology systems through eHealth literacy: a framework for understanding users’ needs. JMIR Hum Factors. 2015;2(1):e9. 10.2196/humanfactors.3696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lloyd JE, Song HJ, Dennis SM, Dunbar N, Harris E, Harris MF. A paucity of strategies for developing health literate organisations: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0195018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Norgaard O, Furstrand D, Klokker L, et al. The e‐health literacy framework: a conceptual framework for characterizing e‐health users and their interaction with e‐health systems. Knowl Manag E‐Learn. 2015;7(4):522‐540. 10.34105/j.kmel.2015.07.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Norman CD, Skinner HA. eHealth literacy: essential skills for consumer health in a networked world. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(2):e9. 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259‐267. 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2072‐2078. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Paasche‐Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(Suppl 1):S19‐S26. 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paige SR, Stellefson M, Krieger JL, Anderson‐Lewis C, Cheong J, Stopka C. Proposing a transactional model of e‐health literacy: concept analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):e10175. 10.2196/10175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pawlak R. Economic considerations of health literacy. Nurs Econ. 2005;23(4):173‐147. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16189982/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Renwick K. Critical health literacy in 3D. Front Educ. 2017;2:40. 10.3389/feduc.2017.00040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Smith D, Hudson S. Using the person–environment–occupational performance conceptual model as an analyzing framework for health literacy. J Commun Healthc. 2012;5(1):11‐13. 10.1179/1753807611Y.0000000021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Soellner R, Lenartz N, Rudinger G. Concept mapping as an approach for expert‐guided model building: the example of health literacy. Eval Program Plann. 2017;60:245‐253. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sorensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Squiers L, Peinado S, Berkman N, Boudewyns V, McCormack L. The health literacy skills framework. J Health Commun. 2012;17(3):30‐54. 10.1080/10810730.2012.713442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Trezona A, Dodson S, Osborne RH. Development of the organisational health literacy responsiveness (Org‐HLR) framework in collaboration with health and social services professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:513. 10.1186/s12913-017-2465-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. von Wagner C, Steptoe A, Wolf MS, Wardle J. Health literacy and health actions: a review and a framework from health psychology. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(5):860‐877. 10.1177/1090198108322819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yip MP. A health literacy model for limited English‐speaking populations. Contemporary Nursing. 2012;40(2):160‐168. 10.5172/conu.2012.40.2.160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Azevedo Perry E, Thomas H, Samra HR, et al. Identifying attributes of food literacy: a scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20(13):2406‐2415. 10.1017/S1368980017001276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Block LG, Grier SA, Childers TL, et al. From nutrients to nurturance: a conceptual introduction to food well‐being. J Public Policy Mark. 2011;30(1):5‐13. 10.1509/jppm.30.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cullen T, Hatch J, Martin W, Higgins JW, Sheppard R. Food literacy: definition and framework for action. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2015;76(3):140‐145. 10.3148/cjdpr-2015-010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Malan H, Watson TD, Slusser W, Glik D, Rowat AC, Prelip M. Challenges, opportunities, and motivators for developing and applying food literacy in a university setting: a qualitative study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(1):33‐44. 10.1016/j.jand.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Park D, Park YK, Park CY, Choi MK, Shin MJ. Development of a comprehensive food literacy measurement tool integrating the food system and sustainability. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3300. 10.3390/nu12113300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Spiteri‐Cornish L, Moraes C. The impact of consumer confusion on nutrition literacy and subsequent dietary behavior. Psychol Mark. 2015;32(5):558‐574. 10.1002/mar.20800 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Truman E, Bischoff M, Elliott C. Which literacy for health promotion: health, food, nutrition or media? Health Promot Int. 2020;35(2):432‐444. 10.1093/heapro/daz007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Truman E, Elliott C. Barriers to food literacy: a conceptual model to explore factors inhibiting proficiency. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(1):107‐111. 10.1016/j.jneb.2018.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vidgen HA, Gallegos D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite. 2014;76:50‐59. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bergsma L, Ferris E. The impact of health‐promoting media‐literacy education on nutrition and diet behavior. In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin CR, eds. Handbook of Behavior, Food and Nutrition. New York, NY: Springer; 2011:3391‐3411. 10.1007/978-0-387-92271-3_212 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74. DQ Institute . What is the DQ framework? Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.dqinstitute.org/dq-framework/. n.d

- 75. Park Y, ed. DQ global standards report 2019: common framework for digital literacy, skills and readiness. DQ Institute. Published 2019. Accessed May 21, 2021. https://www.dqinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/DQGlobalStandardsReport2019.pdf

- 76. Montgomery K, Grier S, Chester J, Dorfman L. Food marketing in the digital age: a conceptual framework and agenda for research. Report for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Healthy Eating Research Program. Published April 1, 2011. Accessed May 21, 2021.http://digitalads.org/documents/Digital_Food_Mktg_Conceptual_Model%20Report.pdf

- 77. UNESCO’s Global Alliance to Monitor Learning . A draft report on a global framework of reference on digital literacy skills for indicator 4.4.2: percentage of youth/adults who have achieved at least a minimum level of proficiency in digital literacy skills. Commissioned by Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (GAML) United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Published 2018. Accessed May 21, 2021. http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/draft-report-global-framework-reference-digital-literacy-skills-indicator-4.4.2.pdf

- 78. Bergeron K, Abdi S, DeCorby K, Mensah G, Rempel B, Manson H. Theories, models and frameworks used in capacity building interventions relevant to public health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:914. 10.1186/s12889-017-4919-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. U.S. Department of Agriculture . MyPlate Launches USDA’s First Alexa Skill [media release]. Published July 27, 2021. Accessed August 5, 2021. https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2021/07/27/myplate-launches-usdas-first-alexa-skill

- 80. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development . E‐Commerce in the Times of COVID‐19. October 7, 2020. Accessed November 11, 2021. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137212-t0fjgnerdb&title=E-commerce-in-the-time-of-COVID-19&_ga=2.114817863.1778911600.1636666934-2038667852.1636666934

- 81. Vamos SD, Wacker CC, Welter VDE, Schlüter K. Health literacy and food literacy for K‐12 schools in the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Sch Health. 2021;21(8):650‐659. 10.1111/josh.13055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kelly RK, Nash R. Food literacy interventions in elementary schools: a systematic scoping review. J Sch Health. 2021;21(8):660‐669. 10.1111/josh.13053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McNamara J, Mena NZ, Neptune L, Parsons K. College students’ views on functional, interactive and critical nutrition literacy: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:1224. 10.3990/ijerph18031124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the scoping review to identify existing literacy models and frameworks for food, nutrition, health, media, financial, and/or digital literacy antecedents, domains, attributes, characteristics, and/or outcomes.

Figure S1. Integrated Health Literacy Model for Diabetes (Al Sayah and Williams 2012)

Figure S2. Conceptual Model of Individual Capacities, Health‐Related Print and Oral Literacy, and Health Outcomes (Baker 2006)

Figure S3. Process‐Knowledge Model of Health Literacy (Chin et al. 2011)

Figure S4. The Health Literacy Pathway Model (Edwards et al. 2012)

Figure S5. Health Literacy Intervention Model (Geboers et al. 2018)

Figure S6. Comprehensive e‐Health Literacy Model (Gilstad 2014)

Figure S7. Relational Health Literacy Conceptual Model (Goldsmith and Terui 2018)

Figure S8. Verbal Exchange Health Literacy Model (Harrington and Valerio 2014)

Figure S9. e‐Health Literacy Framework (Kayser et al. 2015)

Figure S10. Five‐Dimensional Framework for the Attributes of a Health Literate Organization (Lloyd et al. 2018)

Figure S11. e‐Health Literacy Framework (Norgaard et al. 2015)

Figure S12. e‐Health Literacy Lily Model (includes analytical and context‐specific models) (Norman and Skinner 2006)

Figure S13. Health Literacy Tripartite Model (Nutbeam 2000)

Figure S14. Health Literacy Risk and Asset Models (Nutbeam 2008)

Figure S15. Causal Pathways Model Linking Health Literacy to Health Outcomes (Paasche‐Orlow and Wolf 2007)

Figure S16. Transactional Model of eHealth Literacy (Paige et al. 2018)

Figure S17. Determinants of Health Literacy (Pawlak 2005)

Figure S18. 3D Literacy Model (Renwick 2017)

Figure S19. Person–Environment– Occupational Performance Model to Examine Health Literacy (Smith and Hudson 2012)

Figure S20. Theoretical Qualitative Structural Model of Health Literacy (Soellner et al. 2017)

Figure S21. Integrated Health Literacy Model (Sorensen et al. 2012)

Figure S22. Health Literacy Skills Framework (Squiers et al. 2012)

Figure S23. Organizational Health Literacy Responsiveness Framework (Trezona et al. 2017)

Figure S24. Framework of Health Literacy and Health Action (von Wagner et al. 2009)

Figure S25. Health Literacy Model for Limited English‐Speaking Populations (Yip 2012)

Figure S26. Food and Nutrition Literacy Framework (Azevedo Perry et al. 2017)

Figure S27. Food Well‐Being Model (Block et al. 2011)

Figure S28. Food Literacy Framework for Action (Cullen et al. 2015)

Figure S29. Food Literacy Model for a University Setting (Malan et al. 2020)

Figure S30. Food Literacy for Food Systems and Sustainability Framework (Park et al. 2020)

Figure S31. Framework for Consumer Confusion Related to Healthy Eating (Spiteri‐Cornish et al. 2015)

Figure S32. Food, Nutrition, Health and Media Literacy Outcomes Framework

(Truman et al. 2020)

Figure S33. Food Literacy Proficiency Model (Truman and Elliott 2019)

Figure S34. Framework for Antecedents and Consequences of Food and Nutrition Literacy (Vettori et al. 2019)

Figure S35. Food Literacy Model (Vidgen & Gallegos 2014)

Figure S36. Integrated Health‐Promoting Media Literacy Model (Bergsma & Ferris 2011)

Figure S37. Digital Intelligence Literacy Framework (DQ Institute 2020 and Park 2019)

Figure S38. Advertising Literacy Model (Malmelin 2010)

Figure S39. Digital Food Marketing Framework (Montgomery et al 2011)

Figure S40. Digital Literacy Global Framework (UNESCO 2018)