Summary

China implemented the first phase of its National Healthy Cities pilot program from 2016-20. Along with related urban health governmental initiatives, the program has helped put health on the agenda of local governments while raising public awareness. Healthy City actions taken at the municipal scale also prepared cities to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. However, after intermittent trials spanning the past two decades, the Healthy Cities initiative in China has reached a crucial juncture. It risks becoming inconsequential given its overlap with other health promotion efforts, changing public health priorities in response to the pandemic, and the partial adoption of the Healthy Cities approach advanced by the World Health Organization (WHO). We recommend aligning the Healthy Cities initiative in China with strategic national and global level agendas such as Healthy China 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by providing an integrative governance framework to facilitate a coherent intersectoral program to systemically improve population health. Achieving this alignment will require leveraging the full spectrum of best practices in Healthy Cities actions and expanding assessment efforts.

Funding

Tsinghua-Toyota Joint Research Fund “Healthy city systems for smart cities” program.

Keywords: Healthy china, Urban health, Public participation, Impact

Introduction

China launched its National Healthy Cities pilot program in 2016, the same year as the formation of the Tsinghua-Lancet Commission on Healthy Cities in China. The Commission reviewed and evaluated urban dwellers' health status in China over the preceding four decades and highlighted the health challenges faced by cities today. It drew attention to the health needs of a rapidly growing, aging urban population and the rising trend of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), recommending the adoption of a Healthy Cities approach to address these challenges. Building on the early development of Healthy Cities in China, five areas of improvement were identified: health in all policies (HiAP); public participation; intersectoral collaboration; local goal setting and assessment; and capacity building.1

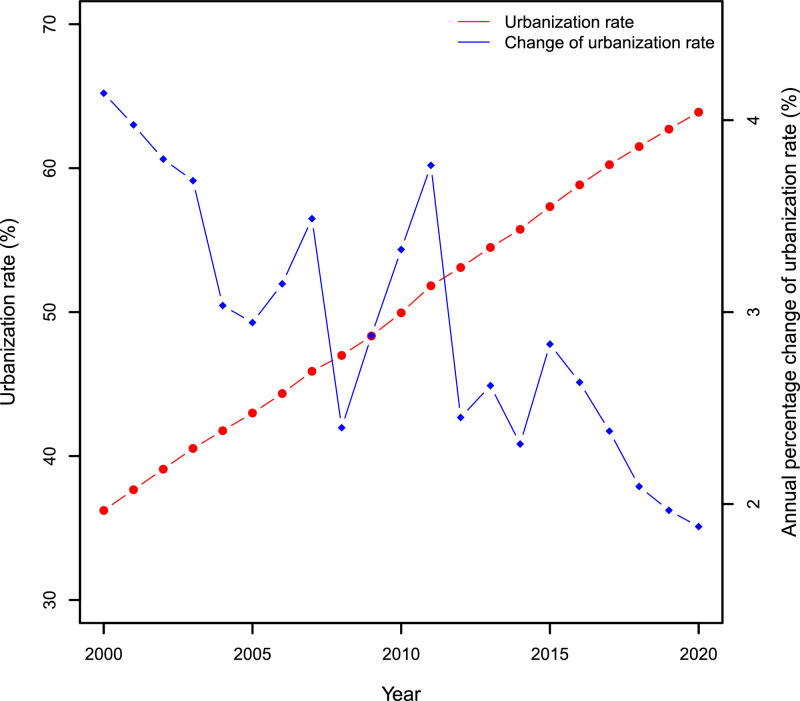

Since 2016, the socioeconomic context for the Healthy Cities initiative in China has changed significantly. Most notably, urbanization is slowing down. Although the overall urbanization rate (urban population/total population) increased from 57·4% to 63·9% between 2016 and 2020,2 annual rates of change have fallen continuously since 2015 (Figure 1). Urbanization in China has been primarily driven by migration from rural to urban areas.3 The migration population peaked in 2015 and is slowly decreasing,4 contributing to the slow-down of the urbanization rate. At the same time, the Seventh National Census showed that the total number of births in China dropped by 33% between 2016 and 2020, with the total fertility rate falling to 1·3, well below replacement.5 This low birth rate will inevitably deepen the challenges for urban populations with respect to aging. Indeed, rapidly aging urban populations make it even more difficult to reduce the disease burden—driven mainly by NCDs—in urban China.6

Figure 1.

Urbanization rates and the annual percentage change of urbanization rate in China from 2000-2020. Data were obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics of China.2

Beyond its demographic impacts, the slowing rate of urbanization has repercussions for local governments' financial situations, since land contributes the lion's share of local revenues.7 This impact is most severe in shrinking cities, where contraction of land-based tax revenues may accelerate further population declines.8 Moving forward, local governments will have reduced financial capacity to support public programs such as the Healthy Cities initiative.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has created new challenges for cities in China. Although it was quickly brought under control with a combination of effective “track-and-trace” and lockdown measures, it has nevertheless caused dramatic human and economic losses in urban China. The rapid transmission of the virus among urban populations and its devastating impacts have focused widespread attention on the importance of urban environments for population health. In a special meeting on public health held in 2020, President Xi Jinping emphasized the need to promote “Health in all Policies”, integrated disease prevention and health promotion across the full life-course of urban planning, construction, and city management while addressing the importance of emergency response and infection control measures.9 As of this writing, China's economy is recovering from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic,10 and cities are engines of the recovery process. They face the challenge, common to cities worldwide, of maintaining a delicate balance between opening up and controlling the pandemic. The Healthy Cities initiative must be responsive to these needs and challenges.

Given that the first phase of the National Healthy Cities pilot program ended in 2020, it is an opportune time to examine the progress of the Healthy Cities initiative in China and its impacts. More broadly, in the face of a changing socioeconomic context and new health challenges, new thinking is needed to move the initiative forward and achieve sustainable urban health improvements in China.

The progress of the healthy cities initiative

Actions to advance healthy cities in China

All levels of government have helped to advance the Healthy Cities initiative in China since 2016. At the national scale, the central government has continuously shaped its development. Goals, principles, and major domains of action of the national pilot program were specified at its inception in 2016 by the National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee (NPHCC), which is an inter-ministerial committee responsible for coordinating disease prevention and control as well as health promotion activities. In addition, 38 cities were selected to participate in the pilot program.11 One year later, the National Health Commission of China put forward a “6+X” model for developing Healthy Cities12 (Box 1).

Box 1. China's “6+X” model for developing Healthy Cities.

The National Health Commission of China requires six actions for local governments committing to the Healthy Cities initiative:

-

(1)

form a steering committee consisting of leaders from the municipal government and relevant agencies, and incorporate the development of Healthy Cities and Healthy Villages and Towns into the socioeconomic development;

-

(2)

compile problem-oriented development plans for Healthy Cities and Healthy villages and Towns;

-

(3)

implement a series of programs with clearly-specified tasks and time schedules, and assure the effectiveness of the development plan;

-

(4)

develop “Healthy Cells” as the basis of Healthy China (i.e., healthy settings, such as healthy schools, healthy offices, and healthy enterprises);

-

(5)

build a health management system for all people with health interventions tailored for population groups with varied health needs, and further promotion of Chinese traditional medicine in disease prevention;

-

(6)

assess the initiative's effectiveness through developing an indicator system and conducting regular assessments by the third party.

Cities are also encouraged to initiate programs catering to local features—the “X” in the approach. 38 cities were selected by the national pilot program to try out the model (Table 1).

Table 1.

The list of 38 cities enrolled in the national pilot program.

| Administrative level | Name |

|---|---|

| Prefecture-levela | Baotou, Dalian, Changchun, Daqing, Suzhou, Wuxi, Zhenjiang, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Maanshan, Xiamen, Yichun, Jinan, Weihai, Yantai, Zhengzhou, Yichang, Zhuhai, Nanning, Chengdu, Luzhou, Guiyang, Yuxi, Lhasa, Baoji, Jinchang, Yinchuan, Karamay |

| County-level or city districtb | Xicheng*, Heping*, Qianan, Houma, Jiading*, Tongxiang, Zixing, Qionghai, Hechuan*, Geermu |

A prefecture-level city is lower than a province but higher than a county at the administrative level of China. There are 293 prefecture-level cities in China.

The pilot program included four city districts (Names labeled with stars). They were grouped with county-level cities in the following analysis.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

The central government, especially the NPHCC, promulgated policies regulating and advancing the Healthy Cities initiative (Table 2). The NPHCC Office also assessed 314 cities (including the 38 pilot cities) in 2019 and 2021 using the National Healthy City Indicator System13 and named the top performers in each province.14,15

Table 2.

National policies to advance the Healthy Cities initiative, 2016–2021.

| Time | Policies | Agency | Relevancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| July 2016 | Guiding Opinions on Constructing Healthy Cities and Healthy Villages and Towns | NPHCC11 | Launched the nationwide Healthy Cities initiative and designated 38 pilot cities |

| April 2018 | National Healthy City Indicator System (2018 edition) | NPHCC13 | Specified 42 indicators for evaluating Healthy Cities |

| July 2019 | Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030) | The State Council | Included the development of Healthy Cities among actions to fulfill targets for Healthy China |

| November 2019 | Regulations on Building Healthy Enterprise (Trial) | NPHCC16 | Specified the role of enterprises in the Healthy Cities initiative |

| November 2020 | Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Deepening the Patriotic Health Campaign | The State Council | Included Healthy Cities in targets and actions to further develop the Patriotic Health Campaign |

Local governments developed Healthy City programs based on the National Health Commission's “6+X” model.12 Beyond the 38 cities enrolled in the national pilot program, every province selected a certain number of cities to pilot the Healthy Cities initiative at the provincial level. Some cities initiated their own Healthy City programs despite not being selected for pilot programs at provincial or national levels.17 Strong support from governments at various levels allowed the Healthy Cities initiative to expand dramatically from 2016 to 2020. For example, besides the 38 pilot cities, 30 cities were cited for excellence in developing Healthy Cities in 2018 by the NPHCC Office.15 This number increased to 68 in 2020.14

The government encourages the public to take an active role in the Healthy Cities initiative. In addition to advocating for people to adopt healthy lifestyles and participate in government health promotion events, the initiative seeks to engage the public through “Healthy Cells,” such as ‘Healthy’ institutions, schools, communities, and enterprises12 (Figure 2). Projects like these, which directly impact where people live and work, are expected to increase public involvement in developing Healthy Cities.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of a Healthy City in China, consisting of various Healthy Cells (e.g., Healthy Schools, Healthy Families, Healthy Enterprises) superimposed on Healthy natural, social, and built environments.

Implementation of the Healthy Cities initiative in pilot cities

Given their deep involvement with the Healthy City initiative, the 38 pilot cities offer insights on how program implementation affects local health governance. Four aspects of policy implementation were evaluated here using methods developed for evaluating health policy implementation,18, 19, 20 including strategy and planning, coordinating mechanisms, implementation, and capacity-building. Government documents issued by the 38 pilot cities, including laws and regulations, annual reports, and announcements, were analysed to extract the relevant information.

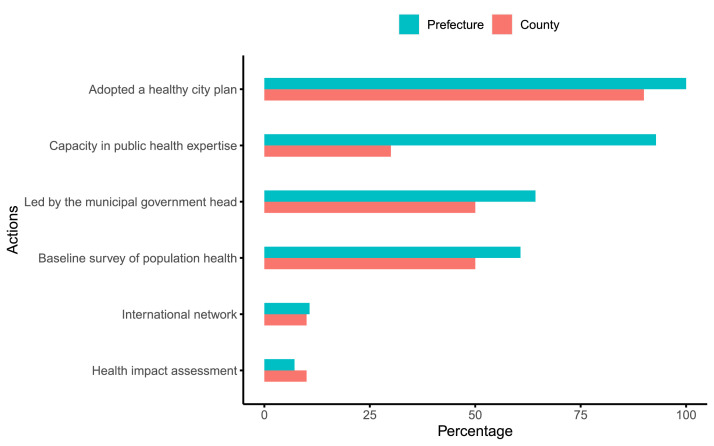

The evaluation revealed both strengths and weaknesses of the Healthy Cities program in the 38 pilot cities (Figure 3). One of the prerequisites for Healthy Cities was the existence of supportive institutional structures and political leadership.21 The 38 cities performed strongly in this area, measured by the existence of a Healthy City plan and municipal leadership. All but one county-level city published Healthy City plans. Half chose mayors or general secretaries of the Chinese Communist Party to serve as steering committee leaders, with the rest led either by deputy mayors or health commission directors. In addition, another critical institutional feature is the capacity to support the Healthy City initiative, as measured by the availability of universities and research institutions with expertise in public health within their administrative areas. Prefecture-level cities had a clear advantage over county-level cities in their access to such expertise.

Figure 3.

Actions implemented by the 28 prefecture- and ten county-level pilot cities in implementing the Healthy Cities programs between 2016 and 2020.

Cities performed less well on three actions more specific to the Healthy Cities approach, including the performance of baseline surveys to establish city health profiles, health impact assessments (HIA), and membership in the international healthy cities network. Slightly more than half of the pilot cities reported completing a baseline survey of general health status, and only three cities had conduct HIAs or instituted regulations to require them. This is a worrisome finding, given that HIA is considered critical for realizing “Health in all Policies”,22 the guiding principle for healthy cities in China. Unclear authority among government agencies and lack of technical capacity have been cited as the main barriers.23 The major challenge for the implementation of HIA is the lack of appropriate tools of HIA for various policies and plans in local contexts. The access to expertise and mechanism for selecting policies to apply HIA has gradually developed in pilot cities. The Handbook for Implementation of Health Impact Assessment was only published in 2019 and renewed annually thereafter by the National Health Commission. Both theoretical and empirical studies are needed to enrich the understanding of health impact and generate knowledge for HIA.

In addition, only three prefecture-level cities and one county-level city held memberships in the Alliance of Healthy Cities, a network of 190 cities in the West Pacific region supported by the WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Treating the initiative as a program initiated by the central government may be the root of the lack of international collaboration. There is no incentive for the local governments to seek international collaboration actively because it is not mandated. This low level of international participation indicates the need for healthy cities in China to collaborate more broadly to stimulate the adoption of best practices and generate accountability.

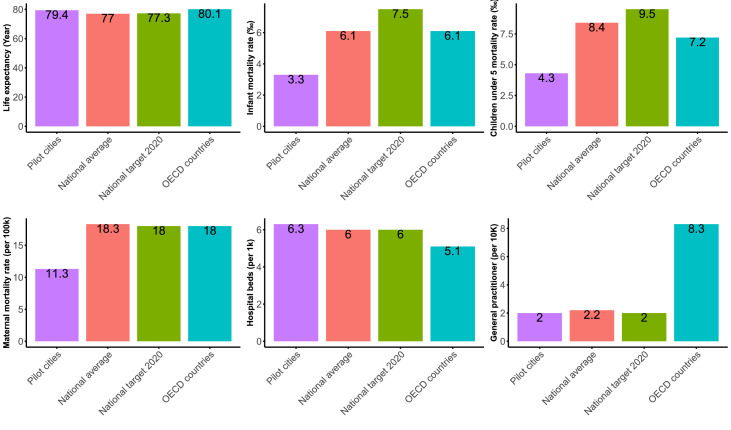

Despite all those limitations, an assessment of the pilot cities conducted by the NPHCC Office in 2018 showed positive impacts of the Healthy Cities initiative. Among the 29 indicators that national average values were available, the pilot cities performed better than the national average in 28 indicators. Also, in the 32 indicators that had national target values for 2020, the pilot cities already surpassed 23 of them.24 The performance of the pilot cities in some health indicators was close to or even better than in developed countries (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Values of selected health indicators for the 38 pilot cities in 201824 compared to the national average values in 2018,25 national targets for 2020,24 and the average values of Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries in 2018.26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Note: Only the median value of the life expectancy was available for the pilot cities. The maternal mortality rate for OECD countries was the estimated value for 2017.

Challenges faced by the healthy cities initiative in China

The COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 has exposed inadequate preparedness for emerging infectious diseases in cities worldwide.32 While Chinese cities were caught off guard in the same way as others, the Healthy Cities initiative has helped them avoid more disastrous outcomes (Box 2). Measures promoted by the initiative were found to be effective in reducing viral transmission and mitigating the impacts of the pandemic. For example, the initiative requires actions to improve health literacy and promote health in public media outlets. These actions contributed to the predominant willingness among urban residents to adopt infection control measures such as wearing masks.33 Other actions required under the Healthy Cities initiative, such as robust systems to support NCD management among residents, or the provision of green public spaces, have been shown to mediate the deaths and mental illness caused by COVID-19, respectively.34,35

Box 2. Suzhou during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Suzhou has a population of 12·75 million. Suzhou has the longest continuous Healthy Cities program in China, initiated in 1999, and has been a member of the Alliance of Healthy Cities run by the WHO West Pacific Regional office since 2003. The city program is organized around five domains: disease prevention, health promotion, disease treatment, chronic disease management, and monitoring. Over 20 years of continuous effort, Suzhou has achieved a health literacy level of 27.6% in its population in 2019, which was above the national target by 2020 (20%) and close to the national target by 2030 (30%). Over 95% of its neighbourhood communities have created support groups to help residents manage chronic diseases.36 The city has also published more than 100 standards and guidelines on healthy settings, including probably the first standard for Healthy Markets in China.37 These efforts helped the city to quickly mobilize its residents to implement control measures and manage underlying medical conditions associated with increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

However, the pandemic has also exposed gaps in the Healthy Cities initiative in China. For one, the initiative is largely modelled on the WHO European Healthy Cities program, which focused more on NCDs and less on infectious diseases.38 The imbalance is clear—only two of the 42 indicators in the National Healthy City Indicator System (2018) are directly relevant to infectious diseases. Now, as Chinese cities seek urgently to prevent and control a deadly pandemic, this imbalance looms large. The pandemic raised many novel questions. Should live animal markets be maintained in city centres given the experiences of SARS and COVID-19? Is it safe to build hospitals in densely populated areas? How can cities harvest the benefits of compact development while achieving the prevention of infectious diseases? How to mitigate the detrimental side-effects of infection control measures on the physical and mental health of urban dwellers? Seeking answers to these questions falls under the mandate of the Healthy Cities initiative given its main goal of addressing the environmental and social determinants of urban health with a systems approach.

Overlap with other programs

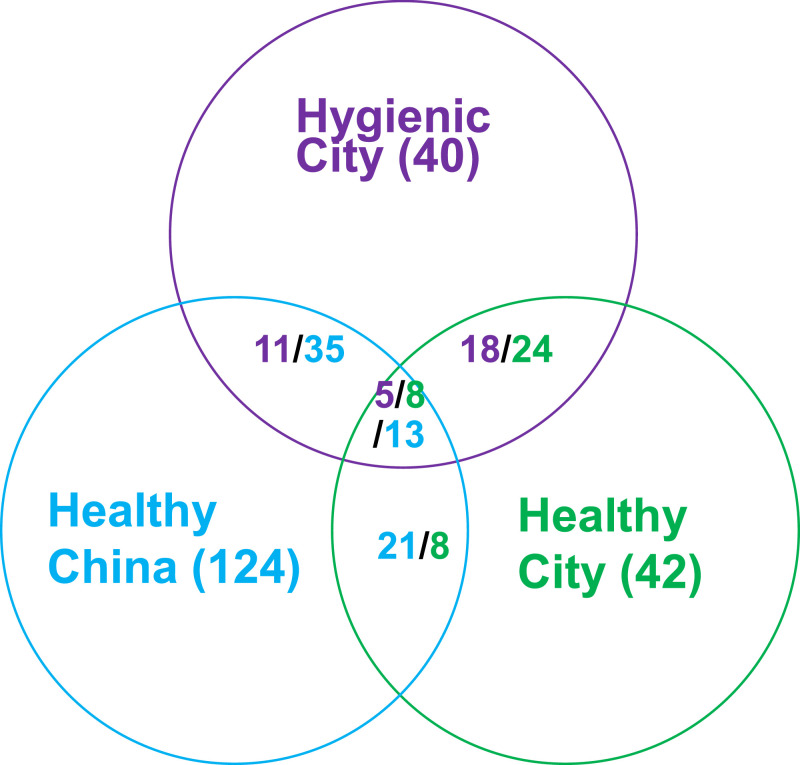

The Healthy Cities initiative overlaps with programs both within and beyond the health sector. For instance, the National Comprehensive Prevention and Control of Chronic Disease Demonstration Zones project, initiated in 2010 to counter the rising trend of chronic diseases,39 overlap with the Healthy Cities initiative in addressing health behaviours and conditions of the living environment. Health reforms promoted by the National Health Commission of China to streamline the health service and enhance primary health care40 share common ground with the initiative in the domain of health services. Even under the same roof as the NPHCC, the Healthy Cities initiative competes with the National Hygienic City program,41 which aims to improve urban sanitation and hygiene, given broad commonalities between the two programs (Figure 5). Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic tilts the balance of interest towards the National Hygienic Cities program because environmental sanitation and personal hygiene are essential for shutting down the transmission pathways of the coronavirus.

Figure 5.

Overlap between indicators used in the National Healthy City Indicator System (“Healthy City”) and two related programs run by the National Health Commission of China, i.e., the Healthy China program (“Healthy China”), and the National Hygienic Cities program (“Hygienic City”). The total number of indicators used in each program is given in parentheses. Numbers in overlapping zones represent matched indicators across the designated programs, denoted by colours. Note that an indicator under one program may match more than one indicator under another. See supplementary file for a full list of indicators for the three programs.

A more complex relationship exists between the Healthy China national strategy and the Healthy Cities initiative. In the Healthy China 2030 Outline released by the State Council of China in 2016, Healthy cities were highlighted as critical to its implementation. Subsequently, in 2019, the Council published the Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030), which includes targets for 124 health indicators, to be achieved by 2030, and 15 specific actions to meet those targets.42 These indicators cover major chronic and infectious diseases and associated risk factors. Healthy Cities are mentioned among other actions to build healthy environments and as part of the overall supporting mechanisms. However, no specific actions or targets are articulated for the Healthy Cities initiative.

Since the publication of the national action plan, most cities have announced local action plans, which generally folded the Healthy Cities initiative into their Healthy China activities. For example, among the 38 pilot cities, only one publicly released a Healthy City development plan extending beyond 2020, with two more indicating an intention to do so. The remaining cities discontinued their Healthy City development plans beyond 2020. When asked about the reasons for putting the program on hold, people in charge cited the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and the lack of support as the main causes (Box 3).

Box 3. Reasons for putting the healthy cities initiative on hold.

Staff in charge of Healthy Cities programs in four cities offered their reasons for the cessation of the Healthy Cities programs in their cities.

The pandemic. Covid-19 prevention and control have become the top priority for every level of government and the health system. Except for routine management, there is no energy left for programs such as Healthy Cities, which the upper-level government does not mandate, is not urgently needed by the public, and the benefits are not immediately visible. Everyone feels exhausted after the round after round of the pandemic waves.

The brand names. There are too many programs in China and too many brand names for cities. If a program has the full attention of the upper-level government, it will be implemented more forcefully. Other brand names will replace Healthy Cities when it cannot garner consistent focus from the upper-level government and the media.

Public support. The program's outreach efforts to the public and people's acceptance of the program are deficient. Therefore, the Healthy Cities initiative is merely a catch term for the public. The public wants the health benefits that the Healthy Cities initiative will bring but does not care which program will bring them. Self-motivated support from the public is far from adequate. All these factors have contributed to a weird situation: the governments are enthusiastic about the initiative, but the public, who supposedly will benefit from the initiative, is not interested.

Enforcement. This problem results from the second and the third issues. The local governments and governments at higher levels should develop effective ways to promote the Healthy Cities initiative. For example, based on the “All for people's health” principle, the governments can elevate the initiative above other programs. Also, outreach efforts need to be enhanced to allow the public to understand the contents and targets of the initiative better, so they will participate in the initiative.

Investment. Continuing investment in the initiative is not an issue in cities with a strong economy. However, there is high uncertainty about continued investment in cities with a weak economy. This uncertainty is also one of the reasons for the discontinuation of the initiative. Funding support from the national government will be helpful for those cities.

What is the next? There is a feeling of not knowing what to do next after completing the initiative's first phase. Changes in local leaderships add to this uncertainty. As a response, cities take a wait-and-see approach.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

The Healthy Cities initiative also needs to be better coordination with programs run by other government sectors. Non-health sectors increasingly include health as an outcome in their programs. While these programs represent steps towards a HiAP approach, they overlap with the Healthy Cities initiative in many aspects. For example, the Civilized Cities program, administered since 2003 by the Central Committee of Civilization, includes actions on urban environments and health behaviors.43 The City Physical Exam program, run by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MHURD), touches on the domains of healthy environments and health services.44 In this crowded institutional environment, the Healthy Cities initiative must compete for resources and attention, as just one of the many programs that cities in China must implement.

Limited public participation

Citizen involvement is vital to initiating and implementing bottom-up action and constitutes an indispensable part of the healthy cities approach.45 The guiding policy of the Healthy Cities initiative specified a model wherein local governments take the lead in implementing relevant initiatives and the public follows suit.11 The local governments have engaged in efforts to encourage community participation in the Healthy Cities initiative. Most efforts focus on community capacity building, such as building community health information centres, delivering seminars on health management, setting up health education programs in schools, and mobilizing volunteers and social workers to work on health-related issues. Some efforts involve the public directly, such as hosting mass sports events and health knowledge competitions, designating health ambassadors and healthy families, and handing out health tool bags.24 However, the assessment provided by the program administrators indicated that public interest in the initiative was not strong (Box 3). Other studies have also found that public participation was weak in the Healthy Cities initiative. Limited channels for participation, insufficient capacity, and poor access to information were cited as main barriers.46,47

In addition, repeated exposure to similar actions proposed under different health programs may partially explain the rapid waning of public interest in the Healthy Cities initiative. From the perspective of residents, the initiative is simply another health program run by the government. Many actions proposed under the Healthy Cities initiative have already been promoted through other programs, e.g., the healthy lifestyle espoused by the National Chronic Disease Comprehensive Prevention and Control Demonstration Zones. On the other hand, the issue speaks to a lack of innovation and understanding of changing social context and possibly poor skills in strategic communications, including working with diverse social institutions.

The problem may also have deeper social roots. Chinese citizens have a low interest in participating in public affairs.48 Local government must often laboriously mobilize the public to participate in Healthy City activities using measures such as “Healthy cell”. While a significant number of urban residents can be successfully engaged in a short time,49 these top-down measures cannot substitute the bottom-up actions needed for the Healthy Cities initiative. The failure to treat human health as essential capital for development50 has also contributed to a widespread belief that health is a personal matter rather than a public good. Health is largely framed as a matter of individual responsibility,51 without little acknowledgment of the manifold ways in which unfavourable social or physical environments may restrict the capacity to lead a healthy life.

The way forward

Recommendations from the first commission report

Before suggesting new actions, it is worth looking back at the recommendations made by the original Tsinghua-Lancet Commission Report.1 The commission exhorted Chinese cities to take five vital actions: integrate health into all policies, increase participation, promote intersectoral action, set local goals for 2030 and assess progress periodically, and enhance research and education on healthy cities. Notable progress has been made with respect to these five action domains. However, actions requiring more resources or changes in governance processes are still lacking.

Governments at various levels in China are increasingly placing health high on the urban social and political agenda, a central goal of the Healthy Cities initiative. However, concrete guidelines for integrating health into all policies are still lacking. Supportive mechanisms for HiAP and intersectoral collaboration still need to be strengthened. For example, health has been mentioned in the master plans of many cities.52,53 However, only a couple of cities have thus far formally published regulations or guidelines on integrating health into the urban planning process. As a result, intersectoral collaboration remains weak, and failure to create intersectoral synergies creates redundancies and drives competition for resource allocation between the Healthy Cities initiative and other programs around urban health issues.

In general, rapid deployment of the pilot program and quick results can be attributed to a top-down approach. Nevertheless, this approach is less effective in engaging the public, as exemplified by the declining trend of public interest in healthy cities.

Most cities specified health outcome goals in their Healthy City plans, though they largely followed the goals pre-specified in national policies.54 Now cities primarily adopt goals and actions specified in the Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030) and rarely adapt national proposals to local needs.

Finally, research and education on healthy cities have been enhanced at both national and city levels since 2016.55 For example, the Chinese Society for Urban Studies created the Healthy City Academic Committee in 2018 to promote research and practice on healthy cities. Research centres on Healthy Cities have also been established in top universities including Tsinghua University, Tongji University, and Sichuan University. Nevertheless, the mainstreaming of concepts and approaches to Healthy Cities into urban planning and public health curricula remains limited.

In summary, while the Healthy Cities initiative in China has made substantial progress in all five recommendations, the issues identified by the commission report are still not well addressed.1 After a long history of on-and-off trials since 1994, the Healthy Cities initiative in China has come to a crucial juncture. Whether or not it can successfully navigate these challenges will determine its future as either one inconsequential health program among many or a breakthrough catalyst for urban population health in China.

Healthy cities as a unifying framework

One primary reason for the failure of Healthy City initiatives in developing countries is the lack of continuous political commitment.56 Leaders have different agendas, which do not always prioritize health. Leadership changes can lead to a reduction or even cessation of support for a Healthy Cities initiative. Therefore, it is crucial to align the initiative with political and strategic agendas at the global, country, and local levels.57 The development of the Healthy Cities initiative in Europe has proven the utility of a strategic, evolving approach. European cities are leading efforts to align the Healthy Cities initiative in Europe with global strategies to achieve the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The inclusion of prosperity and peace as targets for healthy cities has injected new life into the Healthy Cities initiative in Europe.58 The long-lasting influence of the European Healthy Cities Network are attributable to its adaptability to emerging social and environmental issues.

China's Healthy Cities initiative should adopt the same strategic and evolving approach to avoid becoming inconsequential. Given that health is increasingly tied to the sustainable development of Chinese cities, there is an excellent opportunity for the initiative to play a unifying role. China has committed at a national level to the sustainable development goals (SDGs). While Goal 3 directly addresses health and well-being, virtually all other SDGs involve important social and environmental determinants of urban health, e.g., zero hunger, clean water, and sanitation. Systematically managing these health determinants is the central mandate of the Healthy Cities initiative. As such, the initiative provides cities with a concrete pathway to achieving the SDGs.

Health is also at the centre of the fight against climate change, as clearly depicted in the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change.59 Chinese cities are particularly vulnerable to the increased health risks posed by climate change.60 The Healthy Cities initiative can be leveraged to increase urban resilience and cities' capacity to manage the health consequences of climate change.

Beyond these global agendas, the Healthy Cities initiative can be tied to local priorities. China articulated a national health strategy and goals in the Healthy China 2030 Outline and subsequently initiated the Healthy China Actions (2019–2030) to implement its strategy and goals. The dominant role of cities in China's governance structure means that the urban action can have a profound impact on the countryside as well. The realization of the Healthy China goals in cities would thus entail broad success for the Healthy China strategy.

Additionally, the Healthy City initiative should be tied to China's Action Plan for Reaching Carbon Dioxide Peak Before 2030 and Working Guidance for Carbon Dioxide Peaking and Carbon Neutrality in Full and Faithful Implementation of the New Development Philosophy. The action plan and guidance are formulated to achieve the goals of carbon dioxide peaking before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Some important actions are strongly linked to and can produce mutual benefits with the Healthy City initiative, such as realizing green and low-carbon development.

As shown in Figure 5, indicators under the Healthy China Actions overlap extensively with those under the Healthy Cities initiative. Instead of competing, the latter should seek synergies with the former. Any overlaps are a positive joint force, and any leftovers are where the Healthy Cities initiative can play a bigger role. The Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030) proposes 15 action domains, each comprising a multitude of specific actions focused on a particular disease, risk factor, or health management issue. The specific focus of each action provides a clear mandate and tangible goals, making each feasible individually. However, cities risk being overwhelmed by the need to execute hundreds of specific actions simultaneously. Which actions should a city prioritize? Can cities achieve the mandated health targets if they take all suggested actions? Cities need to adopt a systems approach, accounting for cross-sector synergies and constraints, recognizing complex feedbacks, and rooted in the participation of relevant stakeholders, in order to prioritize and combine various actions into a coherent program and achieve the desired health outcomes.61 The Healthy Cities initiative offers such an approach.

We recommend aligning the Healthy Cities initiative in China to achieve strategic national and global level agendas: Healthy China 2030, Healthy Cities approach advanced by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). At the same time, rapid urbanization and the subsequent impact on public health in China have generated best practices that may apply to developing economies. To occupy this key role, it must transform itself from a narrowly-defined health promotion program run by the health sector to become an umbrella framework unifying all actions with health consequences in urban areas. As such, its current model of actions, guiding principles, and evaluation needs to be revised to this end.

A comprehensive healthy cities approach

The core value of the Healthy Cities initiative is that it provides local governments with an intersectoral approach to health development, i.e., the Healthy Cities approach. Optimal implementation of this framework constitutes a systems approach that allows urban centres to address environmental and social determinants of health in a systematic way.62 While the concept of Healthy Cities and associated approaches have clearly been well received in China, the real challenge is to implement the full spectrum of best practices under this approach within the larger national framework of Healthy China Actions 2030 driven by the central government. Robust implementation by local governments will be the key to keeping the Healthy Cities initiative alive in China and fulfilling its supporting role with respect to Healthy China 2030.

Three primary approaches for local governance for health and well-being are subsumed in the Healthy Cities approach: health-in-all policies, whole-of-government, and whole-of-society approaches.59,63 In China, all three are reflected in the guiding principles and supporting mechanisms for Healthy China Actions. However, our early assessment shows that even cities in the pilot program did not fully adopt these three approaches.

To do so, tools are needed to analyse the complex health landscape and identify priority interventions. For example, a city health profile and city health development planning are basic components of the Healthy Cities approach. The former helps local decision-makers identify the main local health challenges and their upstream socioeconomic and environmental determinants, while the latter, based on locally specific health needs, enables decision-makers to prioritize actions and goals and allocate resources accordingly. In China, these tools will be critical to adapting nationally proposed actions to local needs, in order to maximize local urban health benefits from the implementation of Healthy China Actions.

In addition, municipal governments should commit to the core goal of Healthy Cities: engaging all stakeholders to work across sectors for population health improvement. From the individual citizen to the entire multisectoral city management structure, every level in the urban hierarchy must be integrated into a single system geared towards maximizing local health outcomes. Healthy Cities rests on horizontal and vertical linkages, along with system adaptation and learning, and requires both strong political leadership and community engagement.

Assessments that better inform cities

Regular assessments were recommended in the Commission report as a key action for implementing the Healthy Cities approach in China. While two nationwide assessments have been conducted so far, various improvements are needed for making them more useful to local governments.

First, cities should leverage the many indicators collected by governmental programs beyond those included in the National Healthy City Indicator System to expand data-driven assessment. Local administrators should focus on the major health problems in their specific city health profile reports. Locally specific indicator systems should be developed using available indicators, drawing on pathway models which link policy interventions, intermediate outcomes and determinants, and health outcomes.64 For instance, exercise has been proposed to prevent cardiovascular diseases. The number of sports facilities reflects the magnitude of a corresponding upstream policy intervention. The percentage of frequent exercisers measures the immediate result of this policy intervention, while incidence of obesity and cardiovascular diseases are indicators of downstream health outcomes. Such pathway models have been used in developing healthy city indicator systems elsewhere, e.g., the Building Research Establishment's International Healthy Cities Index developed in the United Kingdom.65 Pathway models can provide a framework for integrating relevant indicators monitored by the health and non-health sectors into a single coherent system within the Healthy Cities approach. This practice facilitates intersectoral collaboration, since actions taken by different sectors can be analysed according to their health impacts.

Furthermore, assessment should provide information on the implementation process itself, because the Healthy Cities approach recognizes the process to be as important as the outcome. The National Healthy City Indicator System and the Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030) contain numerous outcome indicators. However, indicators for measuring the implementation process are largely absent. Based on the essential domains of actions for the Healthy Cities initiative, we propose the following 10 indicators for measuring the implementation of the Healthy Cities approach (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recommended indicators for assessing the implementation of the Healthy Cities approach.

| Proposed healthy city indicator | Addressed issues in the Action Plan for Healthy China (2019-2030) | Addressed strategy approaches in the essential domains of actions for Healthy Cities | Why it is important |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Percentage of health programs initiated by entities outside of the government sectors | Public participation | Forging local partnerships for health | Civic engagement is a core process for urban health governance |

| 2. Number of healthy policies that go through the public consulting processes | |||

| 3. City health profile report, with information on health inequalities among different city zones and population groups, updated regularly | Make action plans to tackle the main health issues in the local area | Completing a city health profile; Introducing an integrated city health development plan Explaining the meaning and the root causes of inequalities and their negative impact on society Measuring inequalities Developing a step-by-step action plan for the city |

Provides baseline information to develop a city health and equity improvement plan |

| 4. Locally specific city health development plan, updated regularly | Strategic documents giving direction to municipalities and partner agencies | ||

| 5. Local law or regulation on enacting HIA in the policymaking process | Health-in-all policies and health impact assessment | Health in all local policies Developing mechanisms and capacity for integrating health and equity considerations within local policymaking Ensuring policy coherence that is beneficial to health and promoting related synergies Increasing capacity for health impact assessment |

Important measures to enforce Health-in-all policies |

| 6. Percentage of municipal policies and plans that HIA have been applied | |||

| 7. Percentage of government employees trained for conducting HIA | |||

| 8. Number of joint agreements across sectors and with communities | |||

| 9. Memberships of domestic or international healthy city networks | City diplomacy | Exchange ideas with other cities | |

| 10. Inclusion of health determinants and potential health impacts in the city master plan | Healthy urban planning and merge health in the whole life cycle of urban development | Investing in healthy urban planning and design, closely working with urban planners and architects | Address upstream health determinants in the built environment |

Overall, these proposed additional indicators attempt to measure efforts to address intersectoral collaboration, capacity building, and public participation, which constitute key action domains identified by WHO that remain unfulfilled under the Actions for Healthy China and the National Healthy City Indicator System.

Conclusion

The Healthy Cities initiative in China has made progress on many fronts. More local governments are putting health high on their political agendas, a first step toward "Health in all policies". Quick health improvements were apparent in cities that piloted the initiative. Meanwhile, issues such as changing socioeconomic environments, shifting public health priorities amid the COVID-19 Pandemic, partial adoption of the Healthy Cities approach, low public interest in the initiative, and the program's overlap with other health promotion activities are threatening the initiative's survival. The Healthy Cities initiative in China has the potential to provide the framework for intersectoral governance and joined-up program planning and implementation to achieve SDGs and Healthy China 2030 at the local level. To be successful, it would require shared oversight of all relevant programs, shared tools for assessment and evaluation, and leadership development mechanisms that bring together key sectoral leaders and community leaders. A strategic review of Healthy Cities China is the first step forward in this process to move from a siloed program to a unifying framework for urban development and governance. Such a review would need to build in an ongoing process of continuous quality improvement, city-to-city learning, and scaling up. If the Healthy Cities initiative can adapt to the challenges it faces today, it will play a critical role in shaping the Chinese people's health for tomorrow. In the current, rapidly urbanizing world, China's valuable experience in Healthy Cities development will have important implications for other countries in the region sharing similar challenges and aspirations for sustainable development.

Contributors

Peng Gong, Jun Yang, Yuqi Bai, and Bing Xu conceived and led the preparation of the report. Hongjun Yu, Jingbo Zhou, Lee Ligang Zhang, Xiangyu Luo, Yuqi Bai, Yutong Zhang, Yixong Xiao have been involved in data collection. Jun Yang and Peng Gong conducted data analysis and interpretation. Jun Yang, José Siri, and Yuqi Bai prepared figures. All authors contributed to the overall report structure and concepts, and participated in writing.

Declaration of interests

William Summerskill is a former employee of The Lancet. This work was done after his retirement. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Bing Xu, Jun Yang, and Yuqi Bai were supported by the "Healthy city systems for smart cities" program from Tsinghua-Toyota Joint Research Fund and donation from Delos China (HK) limited. Mei-Po Kwan was supported by grants from the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (General Research Fund Grant no. 14605920, 14611621; Collaborative Research Fund Grant no. C4023-20GF) and a grant from the Research Committee on Research Sustainability of Major Research Grants Council Funding Schemes of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Lan Wang was supported by grants from the National Nature Science Foundation of China No. 52078349, 41871359. The funding agencies did not have any role in the paper design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and writing of the paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100539.

Contributor Information

Jun Yang, Email: larix@tsinghua.edu.cn, larix@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Peng Gong, Email: penggong@tsinghua.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Yang J, Siri JG, Remais JV, et al. The Tsinghua–Lancet commission on healthy cities in China: unlocking the power of cities for a healthy China. Lancet. 2018;391(10135):2140–2184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30486-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Bureau of Statistics of China . National Bureau of Statistics; Beijing: 2020. Urban population. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen R, Xu P, Li F, Song P. Internal migration and regional differences of population aging: an empirical study of 287 cities in China. Biosci Trends. 2018;12(2):132–141. doi: 10.5582/bst.2017.01246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health Commission of China . China Population Publishing House; Beijing: 2018. Report of China's Migrant Population Development (2018) [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Bureau of Statistics of China . News Conference on the Release of Data on the Seventh Naitonal Census. 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/ztjc/zdtjgz/zgrkpc/dqcrkpc/ggl/202105/t20210519_1817702.html Accessed 4 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Chen Z, Zhang M, et al. Study of the prevalence and disease burden of chronic disease in the elderly in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2019;40(3):277–283. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Hui ECM. Are local governments maximizing land revenue? Evidence from China. China Econ Rev. 2017;43:196–215. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Z, Cao C, Chen J, Wang H. Does land finance contraction accelerate urban shrinkage? A study based on 84 key cities in China. J Urban Plan Dev. 2020;146(4) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xinhuanet . Xinghuanet; Beijing: 2020. Xi Jingping Hosts a Meeting of Experts on Building up a Powerful Public Health System.http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/leaders/2020-06/02/c_1126065865.htm Accessed 4 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu D, Sun W, Zhang X. Is the Chinese economy well positioned to fight the COVID-19 pandemic? The financial cycle perspective. Emerg Mark Finance Trade. 2020;56(10):2259–2276. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee . 2016. Guiding Opinions on Constructing Healthy Cities and Healthy Townships.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5898/201608/3a61d95e1f8d49ffbb12202eb4833647.shtml Beijing, China. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang F. Adopting the “6+X” model in developing healthy cities. Health News. 2017; published online July 28. http://health.china.com.cn/2017-07/28/content_39059842.htm. Accessed 14 February 2022.

- 13.National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee . 2018 Ed. 2018. The Notice on Releasing the Naitonal Healthy Cities Indicator System.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s5899/201804/fd8c6a7ef3bd41aa9c24e978f5c12db4.shtml Beijing. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee Office . 2021. Notice on the Result of National Evaluation of Healthy Cities Development in 2020 by NPHCC Office.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/gongwen1/202112/da45fed7213a4021a6499ac81e0786bc.shtml Beijing, China. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee Office . 2019. Notice on the Result of National Evaluation of Healthy Cities by NPHCC Office.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/gongwen1/202001/481b1dfa7d834f62bdec212cb717d74b.shtml Beijing, China. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Patriotic Health Campaign Committee . 2019. Notice on Promoting Healthy Enterpries.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s7788/201911/e29880b2e429460cbb73748274106916.shtml Beijing. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian F. Exploration and practice of Healthy City planning. Urban Archit. 2021;18(386):54–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alonge O, Rodriguez DC, Brandes N, Geng E, Reveiz L, Peters DH. How is implementation research applied to advance health in low-income and middle-income countries? BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phulkerd S, Lawrence M, Vandevijvere S, Sacks G, Worsley A, Tangcharoensathien V. A review of methods and tools to assess the implementation of government policies to create healthy food environments for preventing obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases. Implement Sci. 2016;11:15. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0379-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Global Nutrition Policy Review: What Does it Take to Scale Up Nutrition Action? [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsouros A. City leadership for health and well-being: Back to the future. J Urban Health. 2013;90(suppl 1):4–13. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9825-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simos J, Spanswick L, Palmer N, Christie D. The role of health impact assessment in Phase V of the healthy cities European network. Health Promot Int. 2015;30:i71–i85. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su J, Tang Y, Chen JP, et al. Development of health impact assessment sysetem in Shanghai. China Health Resources. 2021;24(5):5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li C, Wu J, Lu Y. In: Annual Report on Healthy City Construction in China (2019) Wang H, Sheng J, editors. Social Science Academic Press of China; Beijing, China: 2019. Development status and suggestions of healthy cities in China; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Health Commission of China. Statistical Communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2018 Medical and Health Services Development, 2019, Beijing, China. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/guihuaxxs/s10748/201905/9b8d52727cf346049de8acce25ffcbd0.shtml. Accessed 14 February 2022.

- 26.World Bank . The World Bank Group; 2022. Mortality Rate, Infant (per 1000 Live births)-OECD members.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN?locations=OE Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Bank . The World Bank Group; 2022. Life Expectancy at Birth, Total (years) - OECD Members.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.LE00.IN?locations=OE Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Bank . The World Bank Group; 2022. Mortality Rate, Under-5 (per 1000 Live Births) - OECD Members.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?locations=OE Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Bank . The World Bank Group; 2022. Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, Per 100,000 Live Births) - OECD Members.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT?locations=OE Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Bank . The World Bank Group; 2022. Hospital Beds (Per 1000 People) - OECD Members.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.BEDS.ZS?locations=OE Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 31.OECD . Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2022. Health Care Resources: Physicians by categories.https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30173 Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freed JS, Kwon SY, El HJ, Gottlieb M, Roth R. Which country is truly developed? COVID-19 has answered the question. Ann Glob Health. 2020;86(1):51. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun CX, He B, Mu D, et al. Public awareness and mask usage during the COVID-19 Epidemic: a survey by China CDC new media. Biomed Environ Sci. 2020;33(8):639–645. doi: 10.3967/bes2020.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikoloski Z, Alqunaibet AM, Alfawaz RA, et al. Covid-19 and non-communicable diseases: evidence from a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1068. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11116-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pouso S, Borja Á, Fleming LE, Gómez-Baggethun E, White MP, Uyarra MC. Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. Sci Total Environ. 2021;756 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Health Education Center of China . People's Medical Publishing House; Beijing: 2020. Best Management Practices of Developing Healthy Cities in China. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fu C, Xin Y. Suzhou University Press; Suzhou, China: 2003. Standards for Healthy City programs. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed S, Dávila JD, Allen A, Haklay M, Tacoli C, Fèvre EM. Does urbanization make emergence of zoonosis more likely? Evidence, myths and gaps. Environ Urban. 2019;31(2):443–460. doi: 10.1177/0956247819866124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Health . 2010. Notice on Releasing the Work Guidline on Chronic Disease Comprehensive Prevention and Control Demonstration Areas.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/wjw/gfxwj/201304/7aee053a7c2143d88d6c20d2369511db.shtml Beijing. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Q, Wang B, Kong Y, Cheng K. China's primary health-care reform. Lancet North Am Ed. 2011;377(9783):2064–2066. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du P, Sun B, Pan L, et al. Achievements and prospects on enviornmental health and sanitary engineering in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;53(9):865–870. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-9624.2019.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.State Council of China . 2019. The State Council's Opinion on Implementing Health China Action.http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2019-07/15/content_5409492.htm Beijing. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Central Committee of Civilization . 2003. The Notice on Releasing the Temporary Methods on Selecting National Civil Cities, Townships, and Instituions by the Central Committee of Civilization.http://www.wenming.cn/ziliao/wenjian/jigou/wenmingban/201312/t20131231_1668724.shtml Beijing. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development . 2020. Notice on Supporting the City Physical Examination by The Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Developmeng.http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/202006/t20200618_245945.html Beijing, China. Accessed 14 February 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dooris M, Heritage Z. Healthy Cities: facilitating the active participation and empowerment of local people. J Urban Health. 2013;90(suppl 1):74–91. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9623-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song Y, Yang Z. A study on issues of public participation in Suzhou healthy city construction. Jiangsu Health Care. 2012;14(4):20–22. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Z, Lan J, Shan W, Xu L. Participating situation of Hangzhou residents for healthy city construction and its countermeasures. Health Res. 2011;31(3):203–206. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grano SA. China's changing environmental governance: Enforcement, compliance and conflict resolution mechanisms for public participation. China Inf. 2016;30(2):129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye X, Liu X, Li Z. Collection of water drops–the development of the Healthy cell project built a solid foundation for Healthy Chengdu. Health Educ Health Promot. 2019;14(1):16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao J, Zhou N. Impact of human health on economic growth under the constraint of environment pollution. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;169 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Lu Y, Jin Y, Wang Y. Individualizing mental health responsibilities on Sina Weibo: a content analysis of depression framing by media organizations and mental health institutions. J Commun Healthc. 2021;14(2):163–175. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resource of Shenzhen . 2021. Shenzhen City Land and Space Master Plan (2020-2035) p. 46. Shenzhen, China. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resource of Chengdu . 2021. Chengdu City Land and Space Master Plan (2020-2035) p. 58. Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shen J, He L, Wen Q, et al. The difference between national and local healthy city indicator systems: a systematic review. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2019;19(6):694–701. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ding G, Zeng S. Healthy Cities' construction in the past 30 years in China: review on practice and research. Mod Urban Res. 2020;(04):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Werna E, Harpham T, Blue I, Goldstein G. Earthscan; Abingdon, Canada and New York, USA: 2014. Healthy City Projects in Developing Countries: An International Approach to Local Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Genewa: 2020. Healthy Cities Effective Approach to a Rapidly Changing World. [Google Scholar]

- 58.WHO Regional Office for Europe . World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; Belfast, United Kingdom: 2018. Belfast Chater for Healthy Cities: Operationalizing the Copenhagen Consensus of Mayors: Healthier and Happier Cities for All. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watts N, Amann M, Arnell N, et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet North Am Ed. 2021;397(10269):129–170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai W, Zhang C, Zhang S, et al. The 2021 China report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: seizing the window of opportunity. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(12):e932–e947. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang C, Gong P. Healthy China: from words to actions. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(9):e438–e439. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Davies WK. Theme Cities: Solutions for Urban Problems. Springer; 2015. Healthy cities: old and new solutions; pp. 477–531. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corburn J, Curl S, Arredondo G, Malagon J. Health in all Urban policy: city services through the prism of health. J Urban Health. 2014;91(4):623–636. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whitfield M, Machaczek K, Green G. Developing a model to estimate the potential impact of municipal investment on city health. J Urban Health. 2013;90(suppl 1):62–73. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9763-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pineo H, Zimmermann N, Cosgrave E, Aldridge RW, Acuto M, Rutter H. Promoting a healthy cities agenda through indicators: development of a global urban environment and health index. Cities Health. 2018;2(1):27–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.